England’s art history is a tapestry woven from centuries of cultural exchange, political upheaval, and creative innovation. From the intricate manuscripts of medieval monasteries to the conceptual provocations of contemporary art, England has produced works that not only reflect its evolving identity but also shape global artistic traditions.

Nestled at the crossroads of European and global influences, England’s art has always embraced a blend of tradition and experimentation. While early English art was heavily influenced by continental styles, particularly from France and Italy, it gradually developed its own voice. By the time of the Tudor period, England was producing masterful portraiture, and during the Romantic era, its landscape painters revolutionized the genre. The industrial age brought new challenges and opportunities, giving rise to movements like the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and fostering an enduring dialogue between art, design, and modernity.

Why England’s Art Matters

England’s artistic legacy is both deeply rooted in its history and remarkably forward-thinking. It reflects the unique cultural forces that shaped the nation, from the spread of Christianity in the medieval period to the transformative power of the Industrial Revolution. Moreover, England’s openness to innovation has made it a fertile ground for movements like modernism and pop art, which have had far-reaching global influence.

- Key Characteristics of English Art:

- Narrative and Storytelling: English art often prioritizes narrative, from the illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages to the dramatic landscapes of the Romantic era.

- Portraiture and Identity: England has excelled in portraiture, exploring themes of power, individuality, and society across centuries.

- Experimentation and Craft: From William Morris’s Arts and Crafts movement to Damien Hirst’s conceptual installations, English art often blends innovation with meticulous craftsmanship.

Themes That Define English Art

Throughout its history, English art has engaged with a set of recurring themes:

- Nature and Landscape: English artists, particularly during the Romantic era, have celebrated the natural world as a source of beauty and inspiration.

- Faith and Power: Religious and political themes dominate early English art, reflecting the centrality of the Church and monarchy.

- Modernity and Innovation: From the Industrial Revolution to contemporary art, English creators have been at the forefront of exploring modern life and its complexities.

A Journey Through England’s Artistic Past

This series will explore the major chapters of English art history, from the illuminated manuscripts of the Anglo-Saxon period to the global acclaim of the Young British Artists (YBAs). Highlights include:

- The grandeur of Gothic cathedrals and the exquisite detail of medieval stained glass.

- The elegance of Georgian portraiture and neoclassical architecture.

- The visionary landscapes of J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, which redefined the genre.

- The radical experimentation of 20th-century artists like Henry Moore and Francis Bacon.

- The contemporary dynamism of artists such as Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst, who continue to push boundaries.

Each chapter will delve into the artists, movements, and historical forces that have shaped English art, offering a comprehensive look at its evolution and lasting impact.

England: Tradition and Innovation

England’s art is a testament to its ability to blend tradition with innovation, creating works that resonate across cultures and eras. Whether through the sublime landscapes of the Romantic era or the provocative conceptual art of today, English artists have consistently challenged conventions while remaining deeply connected to their cultural heritage.

This journey through the history of English art celebrates its diversity and enduring influence, tracing how a small island nation has produced some of the most compelling and transformative art in Western history.

Chapter 1: Medieval Art and the Gothic Tradition (600–1500)

The medieval period in England saw the emergence of a distinctive artistic tradition that reflected the influence of Christianity, feudal society, and England’s growing cultural identity. From the illuminated manuscripts of Anglo-Saxon monasteries to the grandeur of Gothic cathedrals, this era laid the foundation for English art as a unique blend of narrative richness, intricate craftsmanship, and spiritual devotion.

The Anglo-Saxon Era: Early Christian Art

The arrival of Christianity in England during the 6th and 7th centuries brought a profound transformation to its art, replacing pagan motifs with Christian themes. Anglo-Saxon art is best known for its illuminated manuscripts and metalwork, which combined intricate patterns with religious symbolism.

- Illuminated Manuscripts:

- The Lindisfarne Gospels (c. 715–720) are among the finest examples of Anglo-Saxon illumination, blending Celtic interlace patterns with Christian iconography.

- The Book of Kells (although Irish in origin) influenced English manuscript illumination, encouraging a fusion of decorative and narrative elements.

- Metalwork and Jewelry:

- The Sutton Hoo Treasure (early 7th century) provides stunning examples of Anglo-Saxon craftsmanship, including a ceremonial helmet and gold brooches adorned with animal motifs and geometric designs.

- Religious objects, such as the Staffordshire Hoard (discovered in 2009), showcase the precision and artistry of medieval English metalworkers.

The Norman Conquest and Romanesque Art

The Norman Conquest of 1066 brought new influences to English art and architecture, introducing the Romanesque style characterized by massive stone structures, rounded arches, and detailed carvings.

- Norman Cathedrals:

- Durham Cathedral (completed in 1133) exemplifies Romanesque architecture, with its robust columns, rounded arches, and ribbed vaults. Its design would influence English cathedral-building for centuries.

- The Tower of London, built under William the Conqueror, is another example of the Normans’ monumental architectural legacy.

- The Bayeux Tapestry:

- Although likely created in Normandy, the Bayeux Tapestry (c. 1070) depicts the events of the Norman Conquest and offers a visual record of England’s transition under Norman rule. Its narrative style influenced later English art.

The Gothic Style: Light and Verticality

By the 12th century, the Gothic style began to dominate English architecture, ushering in a new era of artistic innovation. Gothic cathedrals were characterized by pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and flying buttresses, allowing for taller structures and large stained-glass windows that bathed interiors in light.

- Gothic Cathedrals:

- Canterbury Cathedral: Rebuilt in the Gothic style after a fire in 1174, Canterbury became a symbol of English ecclesiastical power and artistic ambition.

- York Minster: Completed in 1472, York Minster is one of England’s most magnificent Gothic cathedrals, featuring intricate stone carvings and some of the finest medieval stained glass in Europe.

- Salisbury Cathedral: Known for its soaring spire, Salisbury reflects the English Gothic style’s emphasis on elegance and verticality.

- Stained Glass:

- The stained glass windows of Canterbury Cathedral and King’s College Chapel, Cambridge, depict biblical narratives with vibrant colors and detailed craftsmanship, turning light into a storytelling medium.

Manuscript Illumination in the Gothic Era

During the Gothic period, illuminated manuscripts remained a central art form, particularly in monastic and royal circles.

- The Luttrell Psalter (c. 1320–1340): Commissioned by a wealthy landowner, this manuscript combines religious texts with whimsical depictions of rural life, offering a glimpse into medieval English society.

- The Canterbury Tales Manuscripts: Early editions of Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales were richly illustrated, blending literary and visual storytelling traditions.

Medieval Sculpture and Decoration

Sculpture and decorative arts flourished during the medieval period, adorning cathedrals, churches, and royal commissions.

- Effigies and Tombs:

- Monumental tombs in cathedrals, such as those of Edward III and Richard II in Westminster Abbey, display detailed effigies and heraldic designs, reflecting the power and piety of the English monarchy.

- Stone Carvings:

- Intricate carvings of saints, angels, and biblical scenes adorned cathedral facades and interiors, emphasizing the narrative and didactic role of art in the medieval Church.

Themes and Legacy

The art of medieval England reflects a society deeply rooted in faith, community, and storytelling. Key themes include:

- Religious Devotion: Art was primarily commissioned by the Church to inspire worship and convey biblical narratives.

- Craftsmanship: The intricate detail of manuscripts, metalwork, and architecture showcases the skill of English artisans.

- Narrative Richness: Whether in illuminated manuscripts or Gothic stained glass, English art prioritized storytelling as a central element of its aesthetic.

The medieval period established many of the artistic traditions that would continue to define English art, from the focus on narrative to the fusion of decorative and functional design.

The End of the Middle Ages

By the late 15th century, the Gothic style began to wane as England entered the Renaissance. However, the achievements of medieval art—particularly in architecture and manuscript illumination—remain some of the most enduring symbols of England’s cultural heritage.

Chapter 2: The Tudor and Elizabethan Periods (1500–1600)

The Tudor and Elizabethan periods marked a significant shift in English art, as the nation transitioned from medieval traditions to a more Renaissance-inspired culture. This was a time of profound political and religious change, with the Reformation, the rise of the Tudor dynasty, and the flourishing of Elizabethan culture shaping artistic expression. Portraiture became the dominant art form, reflecting the power and status of the monarchy and aristocracy, while decorative arts and architecture also flourished, blending native styles with continental influences.

The Rise of Portraiture

Portraiture emerged as the preeminent art form during the Tudor period, serving as a powerful tool for projecting authority, wealth, and identity. The Tudor monarchs were particularly keen to use portraiture to solidify their image and reinforce their legitimacy.

- Hans Holbein the Younger:

- Holbein (c. 1497–1543), a German artist who became court painter to Henry VIII, revolutionized English portraiture with his meticulous detail and psychological depth.

- The Ambassadors (1533): Although not a royal portrait, this iconic work exemplifies Holbein’s mastery of symbolism, featuring objects that reflect the intellectual and political tensions of the time.

- Holbein’s portraits of Henry VIII, such as the famous Whitehall Mural (now lost but known through copies), established the king’s image as a powerful and commanding ruler.

- Elizabethan Portraiture:

- Queen Elizabeth I’s portraits, such as the Armada Portrait (c. 1588), were laden with symbolism, portraying her as the “Virgin Queen” and the defender of England against foreign threats.

- Artists like Nicholas Hilliard popularized the miniature portrait, a uniquely English art form that combined Renaissance elegance with intricate detail.

The Impact of the Reformation

The English Reformation, initiated by Henry VIII’s break with the Catholic Church, had a profound effect on art, particularly religious imagery.

- Destruction of Religious Art:

- The dissolution of the monasteries (1536–1541) led to the destruction of countless medieval religious artworks, including stained glass, sculptures, and illuminated manuscripts.

- Religious art shifted focus to more austere and Protestant-friendly designs, emphasizing textual scripture and moral themes over elaborate iconography.

- Book Illustration:

- The rise of Protestantism encouraged the production of printed Bibles and religious texts, often accompanied by woodcut illustrations. These works emphasized the accessibility of scripture to laypeople.

Elizabethan Decorative Arts

The Elizabethan era saw a flourishing of decorative arts, with innovations in textiles, furniture, and metalwork reflecting the wealth and sophistication of the English elite.

- Textiles and Embroidery:

- Lavish tapestries and embroidered garments were highly prized, often depicting allegorical scenes or heraldic designs. Elizabeth herself was an avid collector and wearer of intricate embroidered fabrics.

- Furniture and Woodwork:

- Elizabethan furniture featured elaborate carving and inlay, blending Gothic traditions with Renaissance influences. Oak was the preferred material, used for everything from paneling to large, ornate beds.

- Silverware and Plate:

- The production of silverware flourished, with objects like chalices, spoons, and tankards becoming symbols of status and craftsmanship.

Architecture: The English Renaissance

The Tudor and Elizabethan periods witnessed significant developments in architecture, blending late Gothic elements with Renaissance styles imported from Italy and France.

- Tudor Architecture:

- Hallmarks of Tudor architecture include half-timbered houses, tall chimneys, and large, mullioned windows. Examples include Hampton Court Palace, which combines Tudor Gothic with early Renaissance features.

- Elizabethan Architecture:

- The Elizabethan style emphasized symmetry and grandeur, influenced by Renaissance ideals. Hardwick Hall (1590s), designed by Robert Smythson, exemplifies this style with its expansive windows and balanced proportions.

- Country houses like Longleat and Burghley House became symbols of aristocratic power and cultural refinement.

The Theatre and the Arts

The Elizabethan era is inseparable from its dramatic achievements, with the flourishing of the English Renaissance theatre.

- The Globe Theatre:

- The construction of the Globe Theatre (1599) marked a milestone in English culture, providing a space for performances of works by William Shakespeare and his contemporaries.

- Theatrical productions incorporated elaborate costumes and stage effects, reflecting the visual and performative aspects of Elizabethan art.

- William Shakespeare:

- While primarily a playwright, Shakespeare’s works are deeply visual, using rich imagery and dramatic staging that influenced English artistic sensibilities.

Themes of Tudor and Elizabethan Art

Art during this period was shaped by political ambition, religious upheaval, and cultural pride. Key themes include:

- Power and Authority: Portraits and architecture celebrated the monarchy and aristocracy, reinforcing their legitimacy and status.

- Symbolism and Allegory: Elizabethan art often used complex symbols to convey moral, religious, or political messages.

- Cultural Identity: As England’s power grew, its art reflected a burgeoning sense of national identity, blending native traditions with continental influences.

The Legacy of the Tudor and Elizabethan Periods

The art of the Tudor and Elizabethan periods established many of the visual and cultural traditions that would define English identity. Portraiture, in particular, became a hallmark of English art, setting the stage for the richly detailed works of the Baroque era. The architectural innovations of this period laid the groundwork for England’s Georgian and Victorian styles, while the decorative arts reflected a fusion of practicality and beauty that remains influential.

As England entered the 17th century, the seeds of the Baroque were beginning to take root, promising a new era of drama and opulence in English art.

Chapter 3: The Baroque and Restoration Periods (1600–1700)

The 17th century was a time of dramatic upheaval and transformation in England, marked by the English Civil War, the execution of Charles I, the Cromwellian Commonwealth, and the eventual restoration of the monarchy under Charles II. These political and social changes were reflected in the art and architecture of the period, as England gradually embraced the grandeur and theatricality of the Baroque. While not as exuberant as its continental counterparts, English Baroque art blended opulence with restraint, producing works that captured the complexity of the era.

The Stuart Court and Early Baroque Art

The Stuart monarchs were instrumental in bringing continental Baroque styles to England, fostering a new era of patronage and artistic exchange.

- Charles I as a Patron of the Arts:

- Charles I (1600–1649) was an avid collector of art, amassing a collection of masterpieces by Titian, Rubens, and Van Dyck. His patronage helped elevate England’s cultural profile, particularly in portraiture.

- Anthony van Dyck: A Flemish painter brought to England by Charles I, Van Dyck revolutionized English portraiture with his elegant and emotive style. Works like Charles I at the Hunt (c. 1635) portray the king as both regal and approachable, blending Baroque drama with subtlety.

- Peter Paul Rubens:

- Rubens’ contributions to English art include his monumental ceiling paintings in the Banqueting House at Whitehall (1629–1634), celebrating the divine right of kings. These works exemplify Baroque grandeur and allegory.

Art During the Commonwealth

The execution of Charles I in 1649 and the establishment of the Cromwellian Commonwealth brought a temporary halt to royal patronage, with Puritanical austerity suppressing much of England’s artistic activity.

- Iconoclasm:

- Many royalist artworks and religious images were destroyed during this period, reflecting the Puritans’ disdain for visual splendor and idolatry.

- Miniature Portraiture:

- Despite the broader decline in large-scale art, miniature portraiture flourished, with artists like Samuel Cooper continuing the tradition of detailed, personal likenesses.

The Restoration and the Flourishing of Baroque Art

The restoration of the monarchy in 1660 under Charles II heralded a revival of the arts, as the king sought to reestablish England’s cultural prestige.

- Charles II’s Patronage:

- Charles II’s court embraced the Baroque, commissioning grand architectural projects and luxurious decorative works that reflected the monarchy’s return to power.

- The king’s court painters, such as John Michael Wright, produced portraits that combined Baroque opulence with English sensibilities.

- Sir Peter Lely:

- Lely (1618–1680), a Dutch artist who became court painter to Charles II, was renowned for his portraits of Restoration society. His series The Windsor Beauties (c. 1660–1665) captures the elegance and sensuality of the Restoration court.

Baroque Architecture: Christopher Wren and the Rebuilding of London

The Great Fire of London in 1666 provided an opportunity to rebuild the city with a Baroque sensibility, led by the visionary architect Sir Christopher Wren.

- St. Paul’s Cathedral:

- Wren’s masterpiece, St. Paul’s Cathedral (completed in 1710), is a landmark of English Baroque architecture, blending classical forms with dramatic scale and grandeur. Its soaring dome remains an iconic feature of London’s skyline.

- City Churches:

- Wren also designed numerous parish churches in London, such as St. Mary-le-Bow and St. Bride’s, incorporating Baroque flourishes while maintaining a sense of restraint.

- Hampton Court Palace:

- Under Charles II and William III, Hampton Court Palace was expanded with Baroque elements, reflecting the influence of French and Dutch design.

Decorative Arts and Public Spaces

The Restoration era also saw a flourishing of decorative arts and the creation of public spaces that reflected Baroque aesthetics.

- Interior Design:

- Lavish interiors, featuring wood paneling, ornate plasterwork, and tapestries, became hallmarks of Restoration style.

- The use of gilding, mirrors, and intricate furniture designs underscored the opulence of the period.

- Public Squares:

- The development of urban spaces, such as Covent Garden and St. James’s Square, reflected Baroque ideals of symmetry and grandeur, enhancing the public realm.

Themes of the Baroque and Restoration Periods

The art and architecture of this period reflected the tension and transformation of 17th-century England. Key themes include:

- Power and Authority: Baroque art emphasized the grandeur of the monarchy and the Church, reinforcing their central roles in society.

- Drama and Emotion: Inspired by continental Baroque, English art employed theatricality and dynamic compositions to captivate audiences.

- Restraint and Balance: Unlike the exuberance of Italian or French Baroque, English Baroque maintained a sense of restraint, blending grandeur with elegance.

The Legacy of Baroque and Restoration Art

The Baroque and Restoration periods established England as a center of artistic and architectural innovation, setting the stage for the Georgian era’s neoclassical revival. The works of Van Dyck, Lely, and Wren remain cornerstones of English cultural heritage, reflecting a time of profound change and renewal.

As England entered the 18th century, the Enlightenment would usher in a new age of reason and refinement, shaping the next chapter of its artistic evolution.

Chapter 4: The Georgian Era and Neoclassicism (1700–1800)

The Georgian period, named after the reigns of George I through George III, marked a time of cultural refinement, intellectual exploration, and artistic sophistication in England. Rooted in Enlightenment ideals, Georgian art and architecture were heavily influenced by the classical revival known as Neoclassicism. This era saw the rise of portraiture, landscape painting, and elegant architecture, reflecting England’s growing confidence as a global power.

The Rise of Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism emerged as the dominant aesthetic during the Georgian era, inspired by the rediscovery of ancient Roman and Greek art and architecture.

- Influence of the Grand Tour:

- Wealthy Englishmen embarked on the Grand Tour, a cultural pilgrimage across Europe, particularly Italy, to study classical antiquity. This exposure fueled a fascination with Greco-Roman art and inspired collections of classical artifacts.

- The Grand Tour also encouraged the commissioning of Neoclassical works by artists and architects.

- Archaeological Discoveries:

- Excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum (mid-18th century) ignited a classical revival, influencing decorative arts, sculpture, and architecture.

Georgian Architecture: Classical Elegance

The Georgian period is synonymous with architectural refinement, characterized by symmetry, proportion, and classical details.

- Key Figures in Georgian Architecture:

- Sir William Chambers: Chambers’ designs, such as Somerset House in London, epitomize the balance and grandeur of Georgian architecture.

- Robert Adam: Adam’s work, including Kenwood House and Osterley Park, blends Neoclassical principles with intricate interior design, showcasing his skill as an architect and decorator.

- Capability Brown: Known as the father of the English landscape garden, Brown transformed estates like Blenheim Palace with his naturalistic yet carefully designed landscapes.

- Urban Development:

- Cities like Bath and London saw significant expansion, with elegant terraces and squares. The Royal Crescent in Bath, designed by John Wood the Younger, exemplifies the Georgian love of harmony and grandeur.

Painting: Portraiture and Landscape

The Georgian era witnessed a flourishing of English painting, with portraiture and landscape emerging as dominant genres.

- Portraiture:

- Thomas Gainsborough: Gainsborough (1727–1788) was a leading portraitist known for his graceful depictions of English aristocracy, such as The Blue Boy (1770). His work often combined portraiture with pastoral settings, reflecting his love of landscape.

- Joshua Reynolds: Reynolds (1723–1792), the first president of the Royal Academy of Arts, elevated portraiture to a grand and intellectual art form. His works, such as Sarah Siddons as the Tragic Muse (1784), incorporate allegorical and classical references.

- George Romney: Romney’s portraits of figures like Emma Hamilton exemplify the elegance and sentimentality of Georgian portraiture.

- Landscape Painting:

- Gainsborough also excelled as a landscape painter, capturing the idyllic beauty of the English countryside.

- Richard Wilson (1714–1782) is considered the father of English landscape painting, blending classical ideals with naturalistic detail.

Decorative Arts and Neoclassical Design

The Georgian period saw a flourishing of decorative arts, with furniture, ceramics, and metalwork reflecting Neoclassical tastes.

- Furniture Design:

- Cabinetmakers like Thomas Chippendale created furniture that balanced elegance with functionality. His The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker’s Director (1754) became a guide for Neoclassical design.

- Wedgwood Pottery:

- Josiah Wedgwood revolutionized ceramics with his Neoclassical designs, including his iconic blue-and-white jasperware, inspired by ancient Greek vases.

- Silver and Metalwork:

- Silversmiths such as Paul Storr produced exquisite Neoclassical pieces, including tea sets and tableware, showcasing England’s craftsmanship.

The Influence of the Royal Academy of Arts

Founded in 1768, the Royal Academy of Arts became a vital institution for promoting art and training artists during the Georgian era.

- Promoting Grand Style:

- Under Reynolds’ leadership, the Academy championed the “Grand Style,” which emphasized classical themes, historical subjects, and intellectual depth in art.

- Annual Exhibitions:

- The Academy’s exhibitions became major cultural events, offering artists a platform to display their work and gain patronage.

Themes of Georgian Art

The art and architecture of the Georgian era reflect the values and aspirations of Enlightenment England. Key themes include:

- Order and Harmony: Neoclassical art and architecture emphasized balance, symmetry, and rationality, mirroring Enlightenment ideals.

- Cultural Identity: The rise of landscape painting and Neoclassical design expressed a uniquely English aesthetic, blending tradition with classical influences.

- Intellectual Engagement: Art during this period sought to inspire and educate, often incorporating allegory and moral lessons.

The Legacy of the Georgian Era

The Georgian period laid the groundwork for England’s cultural identity as a nation of refinement, intellectualism, and artistic achievement. Its contributions to architecture, painting, and decorative arts remain some of the most celebrated aspects of English heritage.

As the 19th century dawned, the Romantic movement would challenge the rationality of Neoclassicism, ushering in a new era of emotion and individual expression.

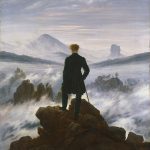

Chapter 5: The Romantic Movement and the Rise of the Landscape (1800–1850)

The Romantic period marked a dramatic shift in English art, as artists moved away from the rationality and order of Neoclassicism toward an emphasis on emotion, imagination, and the sublime. England became a global leader in landscape painting during this time, with artists like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable creating works that redefined how nature was depicted and understood. The Romantic movement in England celebrated individuality, the power of nature, and the emotional depths of human experience.

The Romantic Movement: Key Characteristics

Romanticism in English art emerged in the early 19th century, fueled by political upheaval, industrialization, and a growing interest in the natural world. Key features included:

- Emotion over Rationality: Romantic art focused on expressing profound emotions and the human connection to nature.

- The Sublime: Artists sought to depict the awe-inspiring power of nature, evoking both wonder and fear.

- Individual Expression: Romantic art celebrated the unique vision of the artist, emphasizing creativity and personal experience.

The Rise of Landscape Painting

During the Romantic era, landscape painting became the dominant genre in English art, elevating the depiction of nature to a form of high art.

J.M.W. Turner: The Painter of Light

- Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851) is one of England’s most celebrated Romantic artists, known for his revolutionary approach to light, color, and atmosphere.

- The Fighting Temeraire (1839): This painting, depicting a decommissioned warship being towed to its final berth, is a poignant reflection on change and progress, rendered with luminous color and emotional depth.

- Rain, Steam, and Speed (1844): Turner captures the industrial age with this dramatic depiction of a locomotive, blending the energy of modernity with the chaos of nature.

- Turner’s work transitioned from precise, topographical landscapes to near-abstract explorations of light and color, influencing later movements like Impressionism.

John Constable: The Poet of the English Countryside

- Constable (1776–1837) focused on the idyllic beauty of rural England, often painting the landscapes of his native Suffolk.

- The Hay Wain (1821): This masterpiece, depicting a cart crossing a river, celebrates the harmony of rural life and nature, combining realism with a sense of nostalgia.

- Dedham Vale (1802): Known as “Constable Country,” his depictions of Dedham Vale reflect his deep emotional connection to the land.

- Constable’s work, though less dramatic than Turner’s, emphasized the beauty of everyday scenes and the spiritual connection between humanity and nature.

The Sublime in Landscape

- Artists like John Martin explored the Romantic concept of the sublime, depicting vast, awe-inspiring landscapes and cataclysmic events. Works like The Great Day of His Wrath (1851–1853) combine dramatic compositions with apocalyptic themes.

Romantic Portraiture and Narrative Art

While landscape dominated Romantic art in England, portraiture and narrative painting also flourished, reflecting the era’s fascination with emotion and storytelling.

- Sir Thomas Lawrence:

- A leading portraitist of the Romantic era, Lawrence (1769–1830) captured the drama and elegance of his sitters, such as his painting of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington.

- William Etty:

- Known for his sensual depictions of mythological and historical subjects, Etty’s work, like The Sirens and Ulysses (1837), exemplifies Romanticism’s interest in storytelling and emotional intensity.

The Impact of Industrialization

The Romantic period coincided with the rapid industrialization of England, which profoundly shaped artistic responses to the landscape.

- Celebration and Critique:

- While some artists, like Turner, embraced the drama of industrialization, others lamented its impact on the countryside and traditional ways of life.

- The industrial revolution also influenced urban art, with painters depicting the stark realities of city life.

The Role of Literature and Poetry

Romantic art in England was closely linked to the literary movement of the same name, with artists drawing inspiration from poets like William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Lord Byron.

- Wordsworth’s emphasis on the spiritual power of nature influenced landscape painters, encouraging a view of nature as a source of emotional and moral insight.

- Narrative art often depicted scenes from literature, blending visual and literary Romanticism.

Themes of Romantic Art in England

Romanticism in England explored profound themes that resonate deeply in art history:

- Nature and the Divine: The Romantic landscape celebrated the spiritual connection between humanity and the natural world.

- Emotion and Imagination: Romantic art prioritized personal expression, depicting scenes that resonated with universal feelings.

- Progress and Loss: Artists grappled with the impact of industrialization, reflecting both its promise and its costs.

The Legacy of Romantic Art

The Romantic movement transformed English art, establishing landscape painting as a major genre and setting new standards for emotional and imaginative depth. The works of Turner, Constable, and their contemporaries continue to influence artists and captivate audiences, reflecting England’s enduring connection to nature and its artistic power.

As the Victorian era dawned, new movements like the Pre-Raphaelites would emerge, bringing fresh perspectives to English art while building on the Romantic legacy.

Chapter 6: The Victorian Era: Art and Empire (1850–1900)

The Victorian era was a time of immense change in England, as industrialization, scientific discoveries, and the expansion of the British Empire reshaped society. Art during this period reflected these transformations, with movements like the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the Arts and Crafts movement emerging alongside grand imperial narratives. Victorian art was characterized by its diversity, blending realism, romanticism, and a burgeoning interest in social issues.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

Founded in 1848 by a group of young artists dissatisfied with academic conventions, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) sought to revive the detail, color, and emotional intensity of early Renaissance art, rejecting the industrialized modernity of their time.

- Key Members:

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti: Known for his romantic and symbolic works, such as The Beloved (1865–1866), Rossetti combined medieval themes with sensuality and vibrant color.

- John Everett Millais: Millais’ Ophelia (1851–1852), depicting Shakespeare’s tragic heroine floating in a stream, exemplifies the PRB’s focus on nature, detail, and emotion.

- William Holman Hunt: Hunt’s religious paintings, like The Light of the World (1853–1854), emphasize moral themes and luminous realism.

- Themes and Techniques:

- The PRB were inspired by medieval art, religious narratives, and literary subjects, often painting with bright, jewel-like colors and meticulous attention to detail.

- Their works reflect a tension between nostalgia for a pre-industrial past and engagement with contemporary issues.

Victorian Realism

Victorian realism sought to depict the social and industrial realities of the time, reflecting the influence of scientific thought and photography.

- Ford Madox Brown:

- Brown’s Work (1865) is a masterpiece of Victorian realism, portraying laborers and society’s class divisions with striking detail and social commentary.

- Luke Fildes:

- Fildes’ The Doctor (1891) reflects Victorian interest in social themes and the heroism of everyday life, focusing on a physician tending to a sick child.

- The Influence of Photography:

- Photography’s rise during the Victorian era influenced painters to explore greater realism and detail in their work.

The Arts and Crafts Movement

In reaction to industrialization and mass production, the Arts and Crafts movement emphasized craftsmanship, quality, and the beauty of handmade objects.

- William Morris:

- Morris (1834–1896) was a leading figure in the movement, designing textiles, wallpaper, and furniture inspired by medieval and natural motifs. His firm, Morris & Co., became synonymous with the movement’s ideals.

- Themes and Legacy:

- The Arts and Crafts movement celebrated the unity of art and design, seeking to bring beauty into everyday life. It influenced architecture, interior design, and the emerging Art Nouveau style.

Imperial Art: Power and Splendor

The expansion of the British Empire during the Victorian era shaped English art, with imperial themes appearing in painting, sculpture, and public monuments.

- Grand Historical Painting:

- Artists like Edward Armitage and George Frederick Watts created monumental works celebrating Britain’s imperial power, such as Watts’ allegorical series Hope (1886).

- Public Sculpture and Monuments:

- Sculptors like Alfred Gilbert created grand public works, such as the Eros statue in London’s Piccadilly Circus, reflecting the optimism and ambition of the empire.

- The Albert Memorial (1872) in Kensington Gardens commemorates Prince Albert’s contributions to arts and science, blending Gothic Revival and Victorian opulence.

Themes of Victorian Art

Victorian art reflected the complexities of the era, exploring themes of faith, morality, and the impact of industrialization and empire:

- Moral and Social Commentary: Victorian artists often addressed issues of class, poverty, and social reform, blending realism with compassion.

- Nostalgia and Medievalism: Movements like the PRB and Arts and Crafts reflected a yearning for a simpler, pre-industrial past.

- National Identity and Empire: Imperial themes celebrated Britain’s global dominance while reinforcing a sense of national pride.

The End of the Victorian Era

By the late 19th century, Victorian art began to evolve, influenced by new movements like Symbolism and Impressionism. The grandeur of the empire and the romanticism of the past gave way to a more introspective and experimental approach, setting the stage for modernism in the 20th century.

Chapter 7: The Early 20th Century: Modernism and the Avant-Garde (1900–1945)

The early 20th century was a period of profound transformation for England, shaped by two world wars, industrialization, and the emergence of new artistic philosophies. English artists responded to these changes with bold experimentation, embracing Modernism while forging their unique interpretations. This era saw the rise of abstraction, a focus on form and materials, and an engagement with international avant-garde movements.

The Impact of the World Wars on English Art

Both World War I and World War II had a significant influence on English art, shaping its themes, styles, and priorities.

- World War I:

- The war’s devastation inspired a new kind of realism and emotional intensity in art, with many artists serving as official war painters.

- Paul Nash: Nash’s paintings, such as We Are Making a New World (1918), captured the surreal desolation of the war-torn landscape, blending realism with modernist abstraction.

- John Singer Sargent: Sargent’s monumental work Gassed (1919) depicts soldiers blinded by mustard gas, highlighting the human cost of war with striking realism and poignancy.

- World War II:

- During the Second World War, artists like Henry Moore were commissioned to document the Blitz, producing haunting images of civilians sheltering in London’s Underground, such as Tube Shelter Perspective (1941).

The Rise of Modernism in England

Modernism emerged as a dominant force in English art during the early 20th century, influenced by international movements like Cubism, Surrealism, and Futurism.

- The Vorticists:

- Founded in 1914, Vorticism was England’s answer to Futurism, blending abstraction with industrial and mechanical themes.

- Wyndham Lewis: The leader of the Vorticist movement, Lewis created bold, geometric works like Workshop (1914–1915), emphasizing energy and dynamism.

- The Vorticist journal BLAST combined art and literature, reflecting the movement’s avant-garde ambitions.

- Abstract Art:

- Artists like Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth explored abstraction, focusing on form, texture, and composition. Nicholson’s White Relief (1934) exemplifies the purity and restraint of English modernism.

Henry Moore and the Revolution in Sculpture

Henry Moore (1898–1986) emerged as one of England’s most influential modernist sculptors, transforming traditional notions of sculpture.

- Themes and Techniques:

- Moore’s work often drew on organic forms and natural materials, inspired by landscapes, bones, and shells.

- His semi-abstract sculptures, such as Reclining Figure (1938), combined modernist principles with an enduring connection to the human form.

- War-Time Contributions:

- Moore’s drawings of civilians sheltering during the Blitz captured the resilience of the human spirit, earning him widespread recognition.

Surrealism in England

Surrealism, with its emphasis on the subconscious and dreamlike imagery, also gained traction in England during this period.

- Paul Nash and Surrealism:

- Nash’s later works, such as Landscape from a Dream (1936–1938), reflect his engagement with surrealist ideas, blending natural elements with symbolic and fantastical imagery.

- Eileen Agar:

- Agar explored surrealism through painting and collage, incorporating found objects and mythological themes.

Art and Design in the Modern Era

The early 20th century also saw a renewed interest in the intersection of art and design, influenced by the Bauhaus movement and other international trends.

- Eric Ravilious:

- Ravilious’ distinctive watercolors and designs, such as The Westbury Horse (1939), combine modernist techniques with English pastoral themes.

- Design for Living:

- The Art Deco movement, with its emphasis on streamlined forms and luxury materials, influenced English architecture and interiors, as seen in buildings like the Daily Express Building in London.

The Legacy of Early 20th-Century English Art

The art of this period reflects England’s complex relationship with modernity, balancing innovation with tradition. Key themes include:

- War and Resilience: Both world wars inspired works that grappled with the fragility of human life and the devastation of conflict.

- Form and Abstraction: English modernists focused on the purity of form and materials, pushing boundaries while maintaining a connection to the natural world.

- National and Global Perspectives: While engaging with international movements, English artists retained a distinct sense of place, often drawing inspiration from the countryside and industrial landscapes.

As England emerged from the turmoil of the Second World War, a new generation of artists would further redefine its artistic identity, paving the way for post-war innovation.

Chapter 8: Post-War British Art: New Visions (1945–2000)

In the aftermath of World War II, English art entered a period of reinvention. The devastation of war and the challenges of reconstruction inspired artists to explore new forms of expression, resulting in groundbreaking movements that pushed the boundaries of creativity. From the humanist sculptures of Henry Moore to the provocative works of the Pop Art movement, post-war English art became a stage for innovation, experimentation, and global influence.

The New Humanism: Rebuilding through Art

The immediate post-war years saw a focus on humanist themes, as artists grappled with the trauma of war and sought to rebuild society.

- Henry Moore:

- Moore continued to dominate English sculpture, creating works that symbolized resilience and renewal. Pieces like Family Group (1948–1949) reflect themes of unity and hope.

- Barbara Hepworth:

- Hepworth’s abstract sculptures, such as Pelagos (1946), explore the relationship between form, material, and space. Her work often drew on natural landscapes, offering a sense of harmony and continuity.

Abstract Expressionism and the St. Ives School

Abstract art flourished in post-war England, particularly in the seaside town of St. Ives, Cornwall, which became a hub for avant-garde painters and sculptors.

- Key Figures:

- Ben Nicholson: Nicholson’s geometric abstractions, such as 1946 (Composition), reflect a refined simplicity influenced by European modernism.

- Peter Lanyon: Lanyon’s dynamic landscapes, like Thermal (1960), merge abstraction with a deep connection to the Cornish environment.

- Themes:

- The St. Ives artists focused on abstraction while maintaining a strong sense of place, blending modernist aesthetics with English traditions.

The Rise of Pop Art

In the 1950s and 1960s, England became a center for Pop Art, a movement that celebrated and critiqued consumer culture, mass media, and modern life.

- Richard Hamilton:

- Often regarded as the father of Pop Art, Hamilton created works like Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? (1956), blending advertising imagery with satire and commentary.

- Peter Blake:

- Blake’s iconic work Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover (1967) epitomizes the playful and eclectic spirit of Pop Art.

- Eduardo Paolozzi:

- Paolozzi’s collages, such as I Was a Rich Man’s Plaything (1947), combined popular imagery with surrealist techniques, laying the groundwork for Pop Art’s rise.

Post-War Figurative Painting

While abstraction and Pop Art gained prominence, many English artists remained committed to figurative traditions, exploring themes of identity, alienation, and urban life.

- Francis Bacon:

- Bacon’s emotionally charged works, such as Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1953), use distorted figures to convey existential dread and human vulnerability.

- Lucian Freud:

- Freud’s intimate and unflinching portraits, like Benefits Supervisor Sleeping (1995), highlight the physicality and psychological depth of his sitters, reasserting the power of realism in contemporary art.

Sculpture and the Modern Landscape

Sculpture in post-war England expanded in scope and ambition, blending abstraction with environmental themes.

- Anthony Caro:

- Caro’s large-scale, welded steel sculptures, such as Early One Morning (1962), redefined the medium, focusing on form and space rather than traditional figurative representation.

- Land Art:

- Artists like Richard Long explored the relationship between art and nature, using the English landscape as both medium and subject. Long’s A Line Made by Walking (1967) exemplifies this minimalist approach.

Social and Political Engagement

The latter half of the 20th century saw English artists engaging with pressing social and political issues, reflecting the turbulence of the era.

- David Hockney:

- Hockney’s vibrant works, such as A Bigger Splash (1967), celebrate modern life while exploring themes of sexuality, identity, and personal freedom.

- Gilbert & George:

- This artistic duo used performance, photography, and installations to challenge conventions and provoke dialogue, addressing topics like religion, race, and sexuality in works like The Singing Sculpture (1969).

Themes of Post-War English Art

Post-war English art was marked by its diversity, innovation, and engagement with contemporary issues. Key themes include:

- Rebuilding and Resilience: Many artists grappled with the trauma of war, creating works that symbolized renewal and hope.

- The Everyday: Pop Art and figurative traditions celebrated ordinary life while critiquing its complexities.

- Global Connections: English art embraced international movements while retaining a distinct cultural identity.

The Legacy of Post-War English Art

The post-war period positioned England as a leader in contemporary art, producing works that influenced movements worldwide. The rise of institutions like the Tate Gallery solidified England’s role as a center for artistic innovation, setting the stage for the explosive creativity of the Young British Artists (YBAs) in the 21st century.

Chapter 9: Contemporary Art in England (2000–Present)

Contemporary art in England reflects a nation grappling with the complexities of globalization, technological innovation, and evolving social identities. English artists have continued to shape and challenge the global art scene, blending traditional influences with cutting-edge concepts. This era is marked by experimentation across media, provocative themes, and the influence of institutions like the Tate Modern.

The Young British Artists (YBAs): Leading the Charge into the 21st Century

The Young British Artists, or YBAs, gained prominence in the 1990s and continued to dominate English contemporary art into the 2000s. Known for their provocative works and embrace of mass media, they became household names, pushing art into public discourse.

- Damien Hirst: Hirst’s works, such as For the Love of God (2007), a diamond-encrusted skull, continue to spark debate about the commercialization of art and the nature of value. His earlier piece, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991), featuring a shark preserved in formaldehyde, remains an icon of English conceptual art.

- Tracey Emin: Emin’s deeply personal works, like My Bed (1998), which was re-exhibited in the 2000s, blur the line between autobiography and art, tackling themes of vulnerability, identity, and intimacy.

- Chris Ofili: Ofili’s paintings, including The Holy Virgin Mary (1996), combine traditional African influences with contemporary themes, challenging perceptions of race, religion, and art.

Public Art and Urban Spaces

The turn of the century saw an increase in public art projects that transformed urban landscapes and brought art into daily life.

- Antony Gormley: Gormley’s monumental works, such as The Angel of the North (1998) and Another Place (1997–2005), became cultural landmarks, engaging viewers with themes of humanity and space.

- Banksy: The enigmatic street artist Banksy became a global sensation in the 2000s, blending graffiti with social commentary. Works like Girl with a Balloon (2002) and There Is Always Hope (2003) critique consumerism, politics, and modern culture.

Digital and Media Art

Advances in technology have allowed English artists to experiment with digital media, video installations, and interactive works.

- Julian Opie: Opie’s minimalist portraits and animations, such as his Walking in the City series, capture the essence of contemporary life with bold, digital simplicity.

- Tim Noble and Sue Webster: The duo’s shadow sculptures, like Dirty White Trash (With Gulls) (1998), use discarded objects to create striking, illuminated images, bridging traditional and digital techniques.

Globalization and the New Diaspora

Contemporary English art reflects the influence of a globalized world, addressing themes of migration, identity, and cultural exchange.

- Yinka Shonibare: Shonibare’s works, such as The Swing (After Fragonard) (2001), use vibrant African textiles and references to Western art history to explore colonialism, hybridity, and identity.

- Lubaina Himid: Himid, the 2017 Turner Prize winner, examines themes of race and representation in works like Naming the Money (2004), which highlights forgotten histories of African servants in European art.

The Role of Art Institutions

England’s contemporary art scene thrives on its world-class institutions, which support emerging artists and engage global audiences.

- Tate Modern: Opened in 2000, the Tate Modern in London has become one of the world’s leading contemporary art museums, showcasing groundbreaking exhibitions and fostering dialogue about modern and contemporary art.

- The Turner Prize: The annual Turner Prize continues to spotlight innovative English artists, often sparking public debate about the definition and purpose of contemporary art.

Themes of Contemporary English Art

Contemporary art in England is defined by its engagement with pressing social, political, and cultural issues:

- Identity and Representation: Artists explore themes of race, gender, and individual identity in a globalized world.

- Innovation and Experimentation: The embrace of new media and technologies has expanded the possibilities of artistic expression.

- Social Commentary: Many works critique consumer culture, inequality, and environmental challenges, reflecting a commitment to activism through art.

The Legacy of Contemporary Art

Contemporary English artists have positioned themselves at the forefront of global art, blending tradition with innovation and addressing the complexities of modern life. The art of this era continues to challenge boundaries, provoke thought, and reflect the ever-evolving identity of England in a global context.

This chapter sets the stage for a conclusion summarizing the rich history and enduring influence of English art. Let me know if you’d like me to proceed with Conclusion: The Legacy of English Art!

Conclusion: The Legacy of English Art

English art is a profound reflection of the nation’s history, values, and identity, spanning centuries of cultural innovation and transformation. From the medieval grandeur of Gothic cathedrals to the cutting-edge conceptual works of the Young British Artists, England has consistently shaped the trajectory of Western art while forging a distinct creative voice.

Themes That Define English Art

Across the centuries, English art has explored recurring themes that reflect its unique cultural perspective:

- Nature and Landscape: Whether through the idyllic pastoral scenes of John Constable or the dynamic abstractions of the St. Ives School, the English countryside has remained a central source of inspiration.

- Power and Identity: Portraiture, from Tudor monarchs to contemporary self-expression, has captured the evolving nature of authority and individuality in English society.

- Innovation and Experimentation: From the Vorticists’ avant-garde vision to Pop Art’s playful critique of consumerism, English artists have continually pushed the boundaries of creativity.

England’s Global Influence

English art has not only mirrored its own society but also shaped global cultural movements. The Romantic landscapes of J.M.W. Turner inspired Impressionist painters in France, while the audacity of the YBAs redefined contemporary art on a worldwide scale. Institutions like the Tate Modern and the Royal Academy of Arts continue to position England as a leader in the global art scene.

A Living Tradition

What sets English art apart is its ability to balance tradition and innovation, honoring its rich heritage while embracing new ideas and technologies. Contemporary artists engage with pressing issues like climate change, identity, and globalization, ensuring that English art remains relevant and resonant.

Enduring Inspiration

The legacy of English art is a testament to the power of creativity to capture the essence of a nation. Its masterworks, from the stained glass of Canterbury Cathedral to the conceptual provocations of Damien Hirst, invite viewers to reflect, imagine, and connect. As English art continues to evolve, it reaffirms its place at the heart of Western culture, offering timeless insights and fresh perspectives for generations to come.

Let me know if you’d like any final refinements, or if you’d like to review the full structure of the article!