German art is a remarkable reflection of Europe’s complex cultural and intellectual landscape, evolving alongside profound historical shifts and intellectual movements that shaped not only Germany but also the Western world. From medieval illuminated manuscripts to the expressive art of German Expressionism, Germany’s artistic legacy reveals a nation of thinkers, visionaries, and reformers, whose works continuously grapple with identity, spirituality, nationalism, and innovation.

A Cultural Crossroads: Germany’s Early Influences

Germany’s position in the heart of Europe made it a cultural crossroads where different artistic and intellectual currents met and mingled. As early as the Romanesque and Gothic periods, German artists absorbed and reinterpreted elements from French, Italian, and Byzantine art, creating distinctly German styles in church architecture and religious art. This era of cross-pollination laid the foundation for a national art that would become known for its intense emotional depth, narrative complexity, and technical skill.

During the Middle Ages, the Holy Roman Empire, a Germanic state that dominated Central Europe, served as a political and cultural center that helped establish Germany as a powerful, cohesive force in European art and religion. This influence gave rise to monumental Gothic cathedrals, rich manuscript illuminations, and intricate sculptures that are still celebrated for their spiritual intensity and visual splendor.

The Influence of Religion and the Protestant Reformation

Religion has long been a powerful influence on German art, especially in the early centuries. However, the Protestant Reformation, ignited by Martin Luther’s 95 Theses in 1517, brought monumental changes to German society and its artistic expressions. Protestantism encouraged more restrained, introspective art that served didactic and moral purposes rather than glorifying wealth and power. This shift gave rise to new artistic forms, particularly in the work of artists like Albrecht Dürer, who blended Renaissance humanism with deeply personal religious themes.

The Reformation’s impact on art also gave rise to a distinct German style, moving away from Catholic opulence to focus on clarity, simplicity, and direct engagement with viewers. This era marked the beginning of German art’s reputation for emotional and psychological depth, a characteristic that would continue to define it for centuries.

German Romanticism and the Birth of National Identity

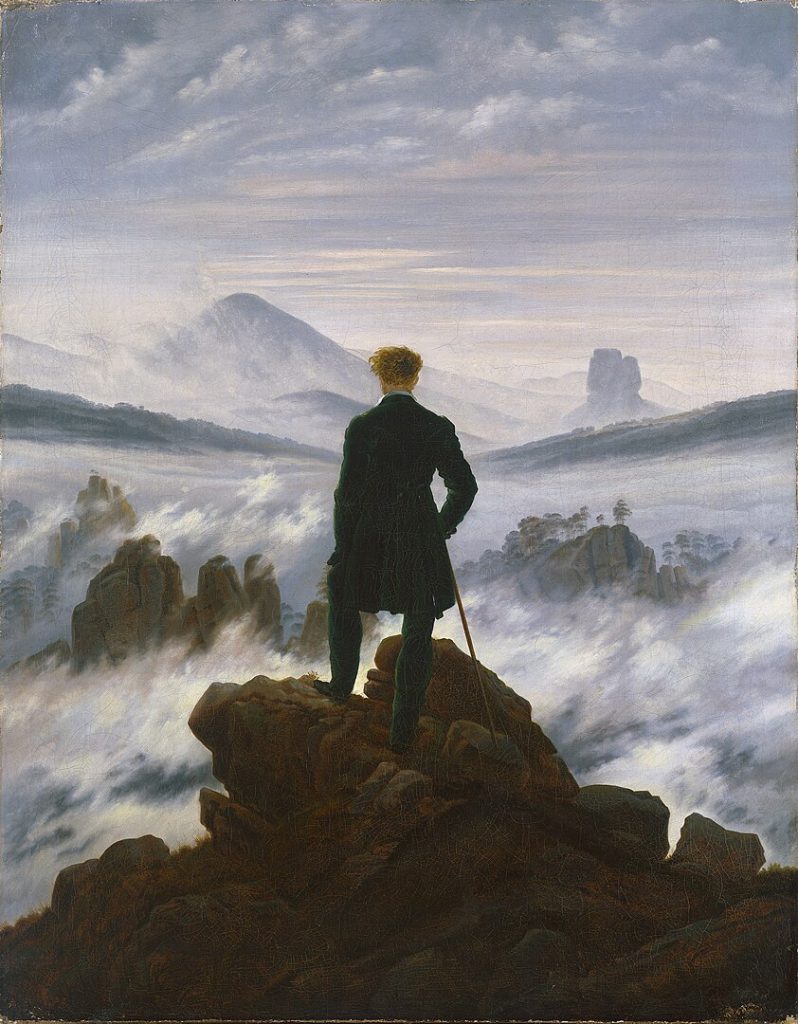

In the 18th and 19th centuries, German art became a powerful medium for expressing the growing sense of national identity and pride. Romantic artists like Caspar David Friedrich turned to the German landscape and medieval heritage as sources of inspiration, producing works that were both introspective and symbolic. Friedrich’s mystical, moody landscapes reflect the German Romantic spirit’s fascination with nature’s power, spirituality, and the sublime.

This era marked the emergence of themes that would continue to resonate in German art: a deep connection to nature, a love for the mystical, and an exploration of the inner self. Romanticism transformed German art into a vessel for exploring complex ideas of nationalism, identity, and spirituality, setting the stage for later artistic movements that would delve even further into these psychological and philosophical depths.

The Modernist Explosion and the Bauhaus

The early 20th century saw Germany become a global leader in modern art, with the explosion of German Expressionism and the founding of the Bauhaus school. German Expressionism, with its raw, emotional power and bold use of color and form, was a reaction to the societal unrest and alienation of pre-World War I Germany. Artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Wassily Kandinsky rejected realism and instead explored psychological states and inner turmoil, themes that became synonymous with German modernism.

The Bauhaus, founded by Walter Gropius in 1919, revolutionized design and architecture with its emphasis on functionalism, simplicity, and mass production. The Bauhaus approach, which integrated art, craft, and industrial design, had a lasting impact on modern architecture and design worldwide, establishing Germany as a birthplace of minimalist, functional aesthetics that are still influential today.

World War II, Trauma, and Rebuilding Through Art

The devastation of World War II and the Holocaust left indelible marks on German art, forcing artists to confront questions of guilt, identity, and memory. The trauma of war led to introspective, often haunting works that attempted to grapple with collective and personal grief. Post-war artists like Anselm Kiefer and Joseph Beuys created works filled with symbolism and existential reflection, aiming to rebuild a fractured identity while engaging with the dark history that had reshaped their country.

The division of East and West Germany during the Cold War further influenced German art, as artists on each side of the Iron Curtain developed divergent styles: Socialist Realism in East Germany and abstract modernism in the West. This era of division cultivated two distinct artistic identities, yet both shared a common purpose—exploring German identity and history from different perspectives.

Contemporary German Art and Global Influence

Since reunification in 1990, German art has continued to evolve, with contemporary artists tackling themes of globalization, memory, and identity in the context of a unified yet diverse nation. Berlin has emerged as a global center for contemporary art, drawing artists and creators from around the world. Figures like Gerhard Richter and Andreas Gursky have pushed the boundaries of painting and photography, blending traditional German introspection with modern media and perspectives.

Today, German art is marked by its openness to experimentation and dialogue with global movements. Berlin’s vibrant art scene has attracted international talent, making it one of the world’s most exciting cultural capitals. Contemporary German art remains deeply engaged with Germany’s history and identity, exploring the past while embracing a cosmopolitan and forward-looking ethos.

The Timeless Themes of German Art

German art is characterized by an intense intellectual curiosity, a fascination with spiritual and existential questions, and an unwavering commitment to craftsmanship. From the Gothic spires of medieval cathedrals to the minimalist lines of Bauhaus design, German art has consistently pushed the boundaries of creativity, driven by a desire to understand the human experience and Germany’s place within it.

In the chapters that follow, we’ll journey through Germany’s artistic legacy, exploring how each era—from the Gothic period to today’s contemporary art scene—has contributed to the rich, evolving narrative of German art. Whether through architecture, painting, or sculpture, German artists have left a profound mark on the world, reflecting the depths of human emotion, thought, and spirit.

Medieval and Romanesque Art in Germany (800–1200 AD)

German art in the early medieval period, spanning roughly 800 to 1200 AD, reflects the fusion of Christian, Germanic, and Roman influences that shaped the Holy Roman Empire. During this time, art and architecture primarily served religious purposes, with monasteries, churches, and cathedrals standing as the spiritual and cultural centers of German life. This period saw the emergence of the Romanesque style, characterized by heavy, rounded forms and grand structures meant to inspire awe and devotion.

The Carolingian and Ottonian Legacy

The Carolingian Renaissance, initiated by Charlemagne (Charles the Great) in the 8th century, sought to revive classical Roman learning and arts within a Christian framework. Charlemagne, crowned Emperor of the Romans in 800 AD, aimed to establish a unified Christian empire. His vision greatly influenced German art, especially in the realms of manuscript illumination, metalwork, and religious iconography.

- Manuscript Illumination: Charlemagne’s court produced some of the earliest and most important illuminated manuscripts, which included beautifully illustrated gospels and psalters. Manuscripts like the Godescalc Evangelistary (781–783) and the Lorsch Gospels demonstrate the Carolingian love for intricate detailing, vivid colors, and religious symbolism.

- Ottonian Art: Following Charlemagne’s death, the Ottonian dynasty (919–1024) continued his legacy. Under the Ottonian emperors, German art flourished, blending Carolingian and Byzantine influences. Ottonian illuminated manuscripts, such as the Reichenau Gospel Book, feature richly colored illustrations with golden backgrounds, symbolizing the divine.

- Religious Iconography and Metalwork: Ottonian metalwork also reached extraordinary heights, producing objects like the Golden Madonna of Essen, a golden figure believed to be one of the oldest full-sized Madonna sculptures in the Christian world. This period set the tone for the reverence of religious icons and relics in German art.

Romanesque Architecture: Foundations of Monumental Design

By the 11th century, the Romanesque style began to take hold in Germany, marking the first truly pan-European architectural style since Roman times. German Romanesque architecture is characterized by its solid, fortress-like appearance, rounded arches, and large towers, aiming to symbolize the power and stability of the Christian faith.

- Speyer Cathedral: Constructed beginning in the early 11th century, Speyer Cathedral became the prototype for Romanesque architecture in Germany. Its massive stone walls, rounded arches, and imposing towers conveyed the power of the Church and the Empire. Speyer’s crypt, completed around 1041, is one of the oldest surviving parts of the structure and one of the largest Romanesque crypts in Europe.

- Hildesheim’s St. Michael’s Church: Built under Bishop Bernward in the early 11th century, St. Michael’s Church in Hildesheim is known for its symmetrical design and intricate bronze doors, which depict scenes from the Bible. The church’s balanced, geometric layout and rhythmic use of columns and arches reflect a structured spirituality that was central to Romanesque design.

- Bamberg Cathedral: Constructed later in the Romanesque period, Bamberg Cathedral showcases the German adaptation of Romanesque architecture, incorporating elements of local craftsmanship and Gothic influences. Its impressive stone carvings and vaulted interiors reflect the solemnity and grandeur characteristic of this period.

The Role of Monasticism and Monastic Art

Monasteries were central to cultural and intellectual life in medieval Germany, serving as centers of learning, art production, and religious devotion. Monks dedicated their lives to copying sacred texts, creating illuminated manuscripts, and producing other devotional works that enhanced religious practice.

- The Reichenau Monastery: Located on an island in Lake Constance, Reichenau became one of the most prominent centers of manuscript illumination in the Ottonian period. The Reichenau artists developed a unique style characterized by bold colors, stylized figures, and minimal backgrounds, emphasizing the spiritual over the earthly.

- Scriptoria and the Spread of Knowledge: Monasteries such as those at Fulda, Lorsch, and Corvey played crucial roles in preserving religious texts and producing manuscripts that were highly valued across Europe. These works weren’t just artistic achievements but also theological tools, meant to deepen devotion and educate the faithful.

The Iconography of Faith: Religious Sculpture and Decorative Art

Romanesque sculpture in Germany, typically found on church facades, portals, and interiors, was deeply symbolic, with each element designed to communicate spiritual truths. Unlike later Gothic sculpture, which sought lifelike representation, Romanesque figures were often abstracted and simplified, emphasizing their divine nature rather than human form.

- Tympanums and Biblical Reliefs: Many Romanesque churches in Germany feature decorated tympanums (the semicircular space above doorways) with reliefs depicting scenes from the Bible, like the Last Judgment or Christ in Majesty. These sculptures served as visual sermons, reminding viewers of salvation and divine power.

- The Gero Cross: Dating back to around 970, the Gero Cross in Cologne Cathedral is one of the oldest large crucifix sculptures in Europe. The life-sized Christ figure reflects both human suffering and divine grace, making it a powerful example of Romanesque devotional art.

- Bronze and Metalwork: The German Romanesque period is also renowned for its bronze casting, especially in the creation of church doors and reliquaries. Notable examples include the Bernward Doors at St. Michael’s Church, which feature intricate biblical scenes and are considered masterpieces of medieval bronze work.

Symbolism and the Power of Sacred Spaces

Romanesque churches were designed to inspire awe and humility, reflecting the power of the Church and the mysteries of faith. Architectural elements like thick walls, small windows, and dimly lit interiors were intentional choices meant to evoke a sense of God’s presence and the incomprehensibility of the divine. These spaces were structured to guide worshippers’ focus toward the altar, the central point of the liturgy.

- The Role of Light: While Gothic cathedrals are known for their abundant light, Romanesque churches used light more sparingly. The dim interiors and small windows allowed only limited sunlight to enter, creating an atmosphere of mystery and reverence. This use of light and shadow was both practical and symbolic, representing the journey from darkness (ignorance) to light (spiritual enlightenment).

- Sacred Geometry: Romanesque architecture employed mathematical precision and geometry as a way to reflect divine order. The symmetrical designs, rounded arches, and perfectly spaced columns were physical manifestations of the spiritual belief in cosmic harmony.

The Legacy of German Romanesque Art

The Romanesque period laid the groundwork for later developments in German art and architecture. This era’s emphasis on spiritual depth, theological themes, and monumental architecture set a standard that would influence later periods, including the Gothic and Renaissance. Romanesque art in Germany also established an enduring tradition of craftsmanship and attention to detail, seen in everything from manuscript illumination to bronze casting.

German Romanesque art and architecture remain testaments to the nation’s medieval heritage, symbolizing a time when art and spirituality were inseparable. Today, Romanesque churches, illuminated manuscripts, and sacred sculptures stand as reminders of the devotion and craftsmanship that defined this era. They continue to inspire awe and reverence, embodying the timeless connection between art and faith that has characterized German cultural identity.

Gothic Art and the Rise of Humanism in Germany (1200–1500 AD)

The Gothic period in Germany marked a transformative era in art and architecture, characterized by soaring cathedrals, intricate sculptures, and a shift toward realism that paralleled the rise of humanist ideals. Gothic art brought a new level of sophistication and emotional depth to religious expressions, and German artists played a crucial role in adapting and evolving the Gothic style, making it uniquely their own. During this time, monumental cathedrals became centers of civic pride and religious devotion, filled with detailed sculptures, stained glass, and frescoes that captivated and educated the faithful.

Gothic Cathedrals: Soaring Structures and the Pursuit of Light

German Gothic architecture, inspired by French innovations, evolved to express not only religious devotion but also local civic pride. Cathedrals in cities like Cologne, Freiburg, and Ulm were monumental achievements, designed to inspire awe and reflect the heavens on earth.

- Cologne Cathedral: One of the most iconic examples of German Gothic architecture, construction of Cologne Cathedral began in 1248 and spanned centuries, finally reaching completion in 1880. Its two towering spires and elaborate façade make it the tallest twin-spired church in the world. The cathedral’s vast interior, filled with soaring arches and beautiful stained glass, created a mystical environment meant to lift the spirit and focus the mind on the divine.

- Freiburg Minster: Begun in the 13th century, Freiburg Minster is another Gothic masterpiece known for its intricate bell tower and stunning stained glass windows. The spire, completed in 1330, was praised by Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt as “the most beautiful tower in all of Christendom,” and the church’s richly decorated portals feature sculptures of saints and biblical scenes.

- Ulm Minster: Though completed later, in the 19th century, Ulm Minster remains significant as the tallest church in the world. Its foundation in the Gothic period reflects the ambition and pride of its builders, while its soaring nave represents the desire to reach heaven through architectural splendor.

These cathedrals were more than places of worship—they were communal projects involving artisans, architects, and townspeople, whose shared vision and faith transformed stone and glass into symbols of hope and unity.

Gothic Sculpture: Expressive Realism and Spirituality

German Gothic sculpture achieved new levels of realism and emotional depth, setting it apart from the more stylized forms of the Romanesque period. Sculptors focused on bringing sacred figures to life with realistic human expressions and anatomical accuracy, reflecting the era’s growing interest in humanism and individual experience.

- Tilman Riemenschneider: One of the most celebrated sculptors of the German Gothic era, Riemenschneider brought intense emotion and detail to his wooden altarpieces and sculptures. His Altarpiece of the Holy Blood (c. 1505) at Rothenburg ob der Tauber is a remarkable example, with intricately carved figures that capture both divine and human elements, blending spirituality with earthly realism.

- Veit Stoss: Another master of late Gothic sculpture, Stoss created deeply expressive religious works, including the massive Altar of Veit Stoss (1477–1489) in Kraków, Poland. Known for its emotional intensity and dramatic composition, the altarpiece shows scenes from the life of Mary, embodying the power of Gothic sculpture to convey both narrative and devotion.

German Gothic sculptures often adorned cathedral façades and interiors, their detailed faces, flowing robes, and intense expressions drawing worshippers into the sacred stories they portrayed. These works emphasized the humanity of biblical figures, connecting viewers more personally to their faith.

Stained Glass and Illuminated Manuscripts: The Art of Light and Color

Stained glass became a hallmark of Gothic art, filling German cathedrals with vibrant colors and illuminating religious scenes through sunlight. These colorful windows served both aesthetic and educational purposes, helping worshippers understand biblical stories and Christian doctrine.

- Stained Glass Windows of Cologne Cathedral: The cathedral’s original stained glass, some of which dates back to the 13th century, displays a range of biblical narratives and saints. Later additions include a modern abstract window by German artist Gerhard Richter, demonstrating the lasting tradition of stained glass as a canvas for spiritual and artistic expression.

- Illuminated Manuscripts: Manuscript illumination continued to flourish during the Gothic period, with works like the Codex Manesse, a collection of medieval German poetry. Lavishly decorated with detailed illustrations, these manuscripts highlighted courtly life and chivalric ideals alongside religious themes, reflecting a more humanistic approach to art.

Stained glass and manuscripts allowed German artists to explore the interplay of light, color, and form, adding layers of meaning to their work while enhancing the visual experience for viewers.

Humanism and the Rise of Realism in Late Gothic Art

The Gothic period in Germany was marked by a growing interest in humanism, a cultural movement that celebrated human experience and individual expression. This shift, which would fully blossom in the Renaissance, began influencing German art in the later Gothic period, inspiring artists to focus on realism, naturalism, and the complexities of the human form.

- The Schöne Madonna (Beautiful Madonna): Representing the new humanistic style, these “Beautiful Madonnas” were sculptures of the Virgin Mary with serene, youthful faces and graceful postures. One famous example is the Beautiful Madonna of Nuremberg (c. 1390–1400), which reflects a gentle, tender view of Mary, emphasizing her humanity as well as her divinity.

- Master Bertram: Active in Hamburg, Master Bertram was known for his altarpieces, such as the Grabow Altarpiece (1379–1383), which depicted the Passion of Christ with a level of detail and realism that moved away from traditional Gothic abstraction.

This human-centered focus marked a significant shift in German art, anticipating the Renaissance’s embrace of individual experience and emotional depth.

Impact of German Gothic Art

The German Gothic period left an indelible mark on Western art, influencing architecture, sculpture, and visual storytelling in profound ways. The massive cathedrals and intricate sculptures of this era are testaments to the German commitment to artistic craftsmanship and religious devotion. Through the combination of expressive realism, innovative architecture, and detailed stained glass, Gothic art in Germany created a deeply spiritual and immersive environment for worshippers.

Moreover, the Gothic emphasis on realism and human emotion laid the groundwork for the rise of humanism in the German Renaissance. By connecting viewers more closely with sacred figures, Gothic art helped bridge the gap between the divine and the human, making spiritual experiences more accessible and personal.

German Gothic art is preserved today in cathedrals, museums, and churches across the country, reminding modern viewers of an era when faith, community, and creativity intertwined to produce some of the most awe-inspiring works in Western art history.

The German Renaissance (1400–1600)

The German Renaissance marked a turning point in German art, as artists absorbed the humanism of the Italian Renaissance while interpreting it through the lens of their own cultural and religious context. This period saw the emergence of some of Germany’s most celebrated artists, including Albrecht Dürer, Lucas Cranach the Elder, and Hans Holbein the Younger, who blended German Gothic traditions with Italian Renaissance ideals of proportion, realism, and perspective. The German Renaissance also coincided with the Protestant Reformation, which reshaped the role of religious art in Germany and influenced artists’ subject matter, style, and patronage.

The Influence of Italian Humanism

The spread of Renaissance ideas from Italy to Germany introduced German artists to new techniques in realism, anatomy, perspective, and classical themes. While German art remained deeply rooted in religious themes, humanism encouraged artists to explore secular subjects, mythological themes, and portraiture with a focus on individual identity.

- The Printing Press and the Spread of Knowledge: Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press around 1440 in Mainz revolutionized art, making printed images and books more accessible. This allowed artists and scholars to disseminate knowledge widely, influencing artistic and scientific advancements. The printing press also played a vital role in the spread of the Reformation.

- Humanist Ideas in Art: Italian Renaissance ideals, such as proportion and harmony, began to appear in German art. German artists were drawn to the emphasis on realistic human figures, anatomical studies, and perspective, which they incorporated into their works alongside German symbolic and emotional intensity.

Albrecht Dürer: The Quintessential German Renaissance Artist

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) stands as a towering figure in the German Renaissance, often called the “German Leonardo” for his mastery of multiple disciplines, including painting, engraving, and mathematics. Dürer’s work epitomized the union of Italian humanism and German Gothic spirituality, creating art that was both intellectually rigorous and deeply expressive.

- Early Works and Italian Influence: After traveling to Italy in the 1490s, Dürer adopted Italian techniques in perspective, proportion, and human anatomy, integrating them into his own style. His famous engraving Melancholia I (1514) reflects this blend, with a detailed, symbolic composition that explores the themes of intellectual pursuit, the divine, and human struggle.

- Master of Engraving: Dürer’s engravings and woodcuts, including Knight, Death, and the Devil and St. Jerome in His Study, achieved unprecedented levels of detail and emotional depth. His ability to convey complex ideas and narratives through engraving made these works widely influential across Europe.

- Portraits and Self-Portraits: Dürer’s self-portraits are among the first true self-representations in Western art. His Self-Portrait at 28 (1500) depicts him in a Christ-like pose, suggesting the divine potential within humanity and the elevated status of the artist. His portraits of prominent figures reflect an intense psychological realism that would become a hallmark of German portraiture.

Lucas Cranach the Elder and the Protestant Reformation

Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553) was another leading artist of the German Renaissance, known for his close relationship with Martin Luther and his role in promoting Reformation ideas through art. Cranach’s work reflects both the influence of Italian Renaissance aesthetics and the moral simplicity emphasized by Protestant ideals.

- Portraits of Reformation Figures: As a close friend of Martin Luther, Cranach created portraits of Luther and other Reformation leaders, contributing to their public image and the spread of Protestantism. His portraits of Luther depict him as a humble, determined figure, contrasting with the grandeur typically reserved for religious leaders.

- Religious Altarpieces and Woodcuts: Cranach produced altarpieces and woodcuts that communicated Lutheran theology. His Wittenberg Altarpiece (1547) is notable for its straightforward, didactic approach, depicting the Last Supper with an emphasis on Christ’s humanity and sacrifice. This style marked a shift from Catholic art’s ornate symbolism toward a simpler, more accessible form of visual communication.

Hans Holbein the Younger and German Portraiture

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497–1543) became one of the greatest portraitists of the Renaissance, known for his meticulous detail and ability to capture both the likeness and character of his subjects. Holbein’s work in Germany and England reflects the German Renaissance’s international reach and its fusion of Italian and Northern European elements.

- Portraits of the English Court: Holbein’s time in England as the court painter for Henry VIII produced some of the most iconic portraits of the era. His portraits of Thomas More, Henry VIII, and other courtiers are celebrated for their precision, attention to detail, and subtle psychological insight.

- The Ambassadors: One of Holbein’s most famous works, The Ambassadors (1533), is a complex double portrait filled with symbolic objects representing science, religion, and mortality. The painting’s famous anamorphic skull—a distorted image only visible from a specific angle—demonstrates Holbein’s technical skill and the Renaissance fascination with perspective.

The Reformation’s Impact on German Renaissance Art

The Protestant Reformation, initiated by Martin Luther in 1517, had a profound impact on German Renaissance art, shifting the focus from religious icons to more secular, human-centered themes. Luther’s criticism of the Catholic Church’s use of art to glorify wealth and power led to a decline in religious commissions and a new emphasis on didactic and personal art.

- Shift in Religious Art: Protestantism discouraged lavish religious art and idolization, leading to a decline in grand altarpieces and sculptures. Instead, Protestant patrons favored simpler art that focused on biblical narratives or moral messages.

- Secular and Private Patronage: With fewer church commissions, artists increasingly turned to secular themes and private patrons. Portraiture, landscape, and genre scenes became more popular, allowing artists to explore humanist themes and personal expression.

- Iconoclasm and Destruction: The Reformation also led to periods of iconoclasm, where many religious images were destroyed in Protestant regions. This resulted in a more subdued artistic style that emphasized moral instruction over ornamentation.

Scientific Exploration and Anatomical Studies

German Renaissance artists were deeply engaged in scientific exploration, using art as a tool to understand human anatomy, mathematics, and the natural world. This scientific curiosity aligned with Renaissance humanism’s focus on empirical observation and the study of nature.

- Leonardo da Vinci’s Influence: Dürer and other German artists were influenced by Leonardo’s anatomical studies and used detailed sketches to improve their understanding of human anatomy.

- Mathematical Perspective: Artists like Dürer and Holbein employed mathematical perspective to create depth and realism in their works, reflecting the Renaissance’s fascination with geometry and proportion.

- Botanical and Natural Studies: German artists were also known for their detailed studies of plants and animals, often depicted in woodcuts and engravings that served both artistic and scientific purposes.

The Legacy of the German Renaissance

The German Renaissance produced some of the most iconic and technically advanced art of its time, blending Northern Gothic spirituality with the Italian Renaissance’s humanistic ideals. The works of Dürer, Cranach, and Holbein embody this synthesis, offering a distinct vision of Renaissance art that combines religious devotion with intellectual rigor.

German Renaissance art laid the foundation for a culture of realism, emotional depth, and introspection that would influence later movements like Baroque, Romanticism, and Expressionism. The era’s focus on individuality and the human experience set a precedent for future generations of German artists, who would continue to explore complex questions of faith, identity, and society.

The Baroque and Rococo Periods in Germany (1600–1750)

The Baroque and Rococo periods in Germany brought a dynamic, expressive quality to art and architecture that was unparalleled in previous centuries. As a response to the religious tensions of the Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation, Baroque art sought to evoke emotional and spiritual intensity, drawing viewers closer to divine experiences through grandeur and movement. Germany embraced these styles with particular fervor, developing distinct regional variations and contributing masterpieces in painting, sculpture, and architecture. The later Rococo period brought an even more ornate and lighthearted aesthetic, favoring intricate decoration, pastel colors, and a focus on opulence that contrasted with Baroque’s often somber tones.

The Baroque’s Emotional Power and Catholic Influence

The Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648), a conflict rooted in religious divisions across Europe, left Germany devastated. Following the war, Baroque art emerged as a means of religious and cultural restoration, heavily influenced by the Catholic Church’s desire to inspire faith through powerful imagery. German Baroque art thus became synonymous with drama, spirituality, and grandeur, often aimed at expressing the triumph of the Church and the glory of God.

- Religious Art and Sculpture: German Baroque artists, often working under Catholic patronage, produced sculptures and altarpieces that conveyed intense emotions, emphasizing physical movement and theatrical compositions. Figures were often depicted in heightened states of ecstasy, grief, or devotion, drawing the viewer into the sacred narrative.

- Counter-Reformation Influence: The Catholic Counter-Reformation aimed to reaffirm the Church’s power and appeal, and Baroque art was an effective tool in this effort. Churches were adorned with elaborate, emotionally charged altarpieces and sculptures that aimed to engage worshippers on a sensory level, reinforcing their faith through beauty and intensity.

Baroque Architecture: Monumental Splendor

German Baroque architecture, with its emphasis on grandeur, symmetrical design, and lavish decoration, is among the most impressive in Europe. Baroque architects aimed to create spaces that inspired awe and reflected divine order, often integrating dramatic staircases, domes, and frescoed ceilings.

- Würzburg Residence: A prime example of German Baroque architecture, the Würzburg Residence, built for the prince-bishops of Würzburg, is celebrated for its vast size, opulent interiors, and grand staircase. The ceiling fresco by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, one of the largest in the world, depicts allegories of the four continents, blending mythological grandeur with religious motifs.

- The Zwinger in Dresden: Originally constructed as an orangery and a venue for court festivities, the Zwinger palace is a stunning example of German Baroque and Rococo fusion. With its elaborate pavilions, sculptures, and fountains, the Zwinger reflects a playful, decorative approach, featuring open courtyards and symmetrical designs meant for royal gatherings.

- St. Michael’s Church, Munich: This grand Jesuit church is a masterpiece of German Baroque architecture. Its interior, with a soaring barrel vault and intricate altarpieces, embodies the Counter-Reformation’s goal of reinforcing faith through architectural splendor. St. Michael’s was constructed to symbolize Catholic victory over Protestantism, making it an architectural emblem of religious conviction.

Key Baroque Artists and Sculptors

German Baroque artists were deeply committed to capturing emotion, movement, and light, creating works that aimed to elevate the viewer’s experience to one of awe and spiritual transcendence.

- Johann Michael Rottmayr: Known as one of the leading Baroque painters in German-speaking regions, Rottmayr produced dynamic frescoes and altarpieces with religious themes. His work is noted for its dramatic use of color and light, as seen in the frescoes of Melk Abbey in Austria.

- Cosmas Damian Asam and Egid Quirin Asam: The Asam brothers, Cosmas Damian (a painter) and Egid Quirin (a sculptor and architect), were prolific Baroque artists whose works often combined painting, sculpture, and architecture into unified, immersive environments. Their most famous work, the Asamkirche in Munich, is a small, private chapel decorated with astonishing detail and a powerful sense of movement and light.

- Andreas Schlüter: Known primarily for his sculptures and architectural contributions in Berlin, Schlüter worked in a style that combined Baroque drama with Classical influences. His most notable work includes the equestrian statue of the Great Elector in Berlin and his architectural contributions to the Berlin Palace.

The Transition to Rococo: Light, Ornament, and Elegance

In the early 18th century, the Rococo style emerged in Germany, characterized by a shift from Baroque’s dramatic, dark themes to a lighter, more playful aesthetic. Rococo art and architecture emphasized elegance, whimsy, and detailed ornamentation, often using pastel colors, gilded details, and asymmetrical designs to create a sense of luxury and refinement.

- Rococo Interiors: Unlike the monumental, often somber tones of Baroque art, Rococo interiors focused on creating intimate, decorative spaces that delighted the senses. Ornate stuccowork, delicate frescoes, and mirrored surfaces created a sense of lightness and airiness. Rooms were often adorned with intricate floral motifs, cherubs, and scrollwork.

- Amalienburg in Nymphenburg Palace, Munich: This lavish hunting lodge near Munich epitomizes the Rococo style, with its silver and gilt decorations, crystal chandeliers, and mirrored walls. The Amalienburg reflects the Rococo interest in creating spaces for leisure and pleasure, a departure from the religious solemnity of the Baroque.

- Pilgrimage Church of Wies (Wieskirche): Located in Bavaria, this Rococo masterpiece by architect Dominikus Zimmermann is known for its airy, light-filled interior, adorned with pastel-colored frescoes and elaborate stucco decorations. The church’s intricate design creates an almost ethereal space, emphasizing beauty and grace.

Rococo Painting and Decorative Art

Rococo art in Germany extended beyond architecture to include painting, sculpture, and decorative arts, with an emphasis on elegance, sensuality, and the celebration of earthly pleasures. Although not as grand as Baroque works, Rococo art was rich in detail and expressed a refined aesthetic that appealed to the aristocracy’s tastes.

- Franz Anton Maulbertsch: Known for his light, pastel palette and delicate brushwork, Maulbertsch painted frescoes and altarpieces that capture the Rococo’s airy, whimsical quality. His works often depicted mythological and allegorical themes, incorporating fluid movement and intricate details.

- Johann Baptist Zimmermann: As a painter and stucco artist, Zimmermann contributed to many Rococo interiors in Bavaria. His use of light, color, and elaborate stucco designs added to the ethereal, decorative character of Rococo spaces, creating immersive environments that enveloped viewers in beauty.

The Cultural Significance of Baroque and Rococo in Germany

The Baroque and Rococo periods in Germany reflect both the intense religiosity and the cultural aspirations of the time. Baroque art and architecture embodied the Church’s response to the Reformation, using grandeur and emotional impact to bring people closer to God. The monumental cathedrals, lavish palaces, and powerful sculptures of the Baroque period aimed to inspire reverence and awe, reinforcing religious devotion through sensory experience.

Rococo, on the other hand, represented a shift towards secular enjoyment and aristocratic elegance, often associated with the courts and nobility. The Rococo style’s lightness and playfulness stood in stark contrast to Baroque’s intensity, emphasizing luxury and a sense of leisurely sophistication. This stylistic evolution from the drama of the Baroque to the delicacy of the Rococo mirrored broader societal changes as European aristocracies moved toward a more relaxed, less formal culture.

Legacy and Influence

The German Baroque and Rococo styles left a lasting impact on European art and architecture, blending dramatic expression with refined beauty. German Baroque cathedrals, palaces, and churches remain among the most visited cultural sites in Germany, while Rococo interiors and decorative arts continue to captivate with their intricate designs and elegance. These periods laid the groundwork for Germany’s reputation in craftsmanship, architectural innovation, and decorative art, elements that would influence later movements such as Neoclassicism and Romanticism.

In Germany, Baroque and Rococo styles are preserved not only in famous buildings but also in countless smaller churches, castles, and estates throughout the country, each reflecting the spirit of their time. Today, they remain symbols of Germany’s artistic heritage and its complex, often shifting cultural landscape.

The Age of Enlightenment and Neoclassicism in Germany (1750–1850)

The Age of Enlightenment brought a sweeping intellectual and cultural shift across Europe, rooted in reason, science, and the pursuit of knowledge. In Germany, this period inspired artists, architects, and scholars to explore classical themes with renewed enthusiasm, leading to the rise of Neoclassicism—a style that embraced clarity, order, and harmony, echoing the aesthetics of ancient Greece and Rome. German art and architecture during this time reflected these ideals, with a focus on symmetry, proportion, and the values of civic duty and virtue.

The Enlightenment’s Influence on German Art and Culture

The Enlightenment emphasized rational thought, scientific inquiry, and individual rights, leading to a more secular outlook on art and culture. German intellectuals, artists, and architects were influenced by these ideas, moving away from the emotional drama of the Baroque and Rococo periods toward a more restrained and intellectual style.

- Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768): Often regarded as the father of art history, Winckelmann was instrumental in promoting Neoclassicism. His writings, particularly Reflections on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture (1755), argued that ancient Greek art represented the pinnacle of beauty and virtue. Winckelmann’s ideas laid the foundation for Neoclassicism in Germany, influencing artists, sculptors, and architects to emulate classical forms.

- Goethe and the Sturm und Drang Movement: While Neoclassicism emphasized order, the Sturm und Drang (“Storm and Stress”) movement, led by writers like Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, focused on emotion and individualism. This duality between rationality and emotion influenced German culture during the Enlightenment, with Neoclassicism representing the intellectual, structured aspect of the era.

Neoclassical Architecture: Order, Proportion, and Classical Inspiration

Neoclassical architecture flourished in Germany during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, with architects drawing inspiration from Greek and Roman structures. This period saw the construction of iconic buildings that celebrated simplicity, symmetry, and civic values, often intended to symbolize the ideals of democracy and public service.

- Brandenburg Gate, Berlin: Designed by Carl Gotthard Langhans and completed in 1791, the Brandenburg Gate is one of Germany’s most recognizable Neoclassical monuments. Inspired by the Propylaea of the Athenian Acropolis, the gate’s stately columns and balanced proportions reflect Neoclassical ideals. The gate became a symbol of peace, unity, and later, reunification.

- Walhalla, Bavaria: Commissioned by King Ludwig I of Bavaria and designed by Leo von Klenze, the Walhalla is a monumental Neoclassical hall near Regensburg that honors notable Germans throughout history. Modeled after the Parthenon in Athens, Walhalla’s marble construction and elegant Doric columns represent the reverence for classical antiquity that defined Neoclassicism.

- Glyptothek, Munich: Also designed by von Klenze, the Glyptothek in Munich is one of the oldest museums in Germany, built to house Ludwig I’s collection of Greek and Roman sculptures. The building’s simple, austere design aligns with Neoclassical principles, creating an environment of order and dignity suitable for the appreciation of classical art.

Neoclassical Sculpture: Celebrating Virtue and Heroism

Sculpture during the Neoclassical period in Germany was heavily influenced by Winckelmann’s admiration for Greek and Roman statuary, emphasizing purity of form and idealized beauty. Neoclassical sculptors sought to embody civic virtue, heroism, and moral clarity, often creating works that reflected historical or mythological themes.

- Johann Gottfried Schadow: One of the most prominent German sculptors of the Neoclassical period, Schadow is best known for his Quadriga (1793), the chariot and horses atop the Brandenburg Gate, symbolizing victory and peace. Schadow’s Princesses Louise and Frederica of Prussia (1795) is another notable work, representing the ideals of feminine grace and harmony while capturing the personal identities of the sitters.

- Christian Daniel Rauch: A leading figure in German Neoclassical sculpture, Rauch created monuments dedicated to German cultural figures and royalty, including the famous statue of Frederick the Great in Berlin. His works exemplify the Neoclassical focus on dignity, restraint, and idealized representation.

- Idealized Portraiture: Neoclassical sculpture often focused on idealized portraits of public figures and intellectuals, capturing their likenesses with a sense of timeless nobility. This style reflected the Enlightenment ideals of rationality, balance, and civic duty.

Painting in the Neoclassical Period: Moral Themes and Classical Aesthetics

While German painting was somewhat slower to adopt Neoclassical ideals compared to sculpture and architecture, artists gradually began to incorporate classical themes, restrained compositions, and moral narratives into their work.

- Anton Raphael Mengs: Known as one of the first German painters to embrace Neoclassicism, Mengs studied in Rome and sought to blend the influence of Raphael with the ideals of the ancient Greeks. His painting Parnassus (1761) reflects classical ideals of balance, harmony, and moral clarity, depicting Apollo and the Muses in a composition reminiscent of ancient frescoes.

- Asmus Jacob Carstens: Another prominent Neoclassical painter, Carstens emphasized allegorical themes and mythological subjects, drawing from the teachings of Winckelmann. His works, including The Battle of the Amazons, incorporate clear lines, balanced compositions, and restrained emotional expression, adhering closely to Neoclassical principles.

German Neoclassical painting often focused on moral and intellectual themes, exploring subjects from mythology, history, and allegory. While it lacked the dramatic intensity of Baroque art, it achieved a timeless quality rooted in reason and ethics.

The Influence of Enlightenment Philosophy on Art and Society

The Enlightenment ideals of reason, progress, and human rights permeated German society and influenced not only art but also education, politics, and philosophy. German intellectuals and artists were inspired by thinkers like Immanuel Kant, whose emphasis on reason and ethics aligned closely with Neoclassical principles. The Enlightenment encouraged a view of art as a tool for moral and intellectual improvement, promoting values such as civic responsibility, self-discipline, and virtuous behavior.

- Educational Reform and Public Institutions: The Enlightenment led to the establishment of public museums, libraries, and educational institutions, including universities and academies. Art became more accessible to the public, and museums like the Altes Museum in Berlin were established to educate citizens and cultivate a sense of national pride.

- Idealism and National Identity: Neoclassical art and architecture helped shape a sense of German national identity, with figures like Goethe and Schiller promoting the idea of Germany as a center of culture and intellectual achievement. These ideals would later influence German Romanticism, as artists sought to express the uniqueness of German culture through idealized visions of history and mythology.

The Transition to Romanticism

By the early 19th century, Neoclassicism began to give way to Romanticism, a movement that emphasized emotion, individuality, and a deep connection to nature. Romantic artists rejected Neoclassicism’s strict adherence to rationality and order, instead favoring an intuitive approach that celebrated the sublime, the mysterious, and the imaginative.

- Caspar David Friedrich and the Romantic Shift: Friedrich, Germany’s leading Romantic painter, represented a dramatic shift from Neoclassical restraint to Romantic introspection. His landscapes, such as Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, captured the awe of nature and the mystery of existence, themes that would come to define German Romanticism.

- Lasting Influence of Neoclassicism: While Romanticism overtook Neoclassicism as the dominant style, Neoclassical principles of balance, proportion, and idealism continued to influence German art and architecture well into the 19th century.

Lessons of the Age of Enlightenment and Neoclassicism in Germany

The Age of Enlightenment and Neoclassicism left an enduring mark on German art, culture, and national identity. Neoclassicism’s emphasis on civic virtue, intellectual rigor, and classical ideals established a foundation for Germany’s intellectual and artistic heritage. The era’s public institutions, museums, and monuments reflect the Enlightenment belief in the importance of education, moral improvement, and cultural pride.

Neoclassical architecture, sculpture, and painting in Germany remain admired for their clarity, elegance, and timeless beauty. As the Enlightenment ideals gave way to the Romantic spirit, the achievements of this period continued to shape German identity, fostering a culture that valued both intellectual pursuit and artistic expression.

German Romanticism and the Rise of Nationalism (1800–1850)

German Romanticism was a powerful artistic and cultural movement that emerged as a reaction against the rationality and order of Neoclassicism. Instead of focusing on harmony and proportion, German Romantic artists sought to express the emotional depths of the human experience, explore nature’s vast mysteries, and revive a sense of national identity rooted in medieval history and folklore. This movement produced some of Germany’s most celebrated artworks, including landscapes, portraits, and historical scenes that resonate with intensity, mysticism, and introspection. The rise of nationalism during this period further influenced German art, as artists aimed to capture the soul of the nation through depictions of its landscapes, myths, and historical heroes.

The Romantic Movement’s Philosophical Roots

Romanticism in Germany was deeply intertwined with the intellectual climate of the time, particularly the works of philosophers and writers like Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, and Friedrich Schelling. These thinkers emphasized individualism, the power of the imagination, and a renewed respect for nature.

- Nature as a Gateway to the Sublime: Romantic artists viewed nature as a reflection of divine power and a source of inspiration. Instead of depicting idealized classical forms, they focused on the raw, often overwhelming beauty of the natural world, seeking to evoke feelings of awe, melancholy, and wonder.

- The Influence of German Folklore and Medievalism: A revival of interest in medieval history and German folklore led to depictions of legendary heroes, gothic ruins, and fairytale landscapes. This fascination with the past fueled a sense of national pride, as artists sought to connect with Germany’s unique cultural heritage.

Caspar David Friedrich: The Master of Romantic Landscape

Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840) is widely regarded as the most influential German Romantic painter, known for his haunting landscapes that convey both the majesty and mystery of nature. Friedrich’s works reflect his belief that nature is a manifestation of the divine, offering a window into the infinite.

- Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818): This iconic painting depicts a lone figure standing on a rocky peak, gazing out over a vast, fog-covered landscape. The figure’s back is turned, inviting viewers to join him in contemplating the sublime. The painting captures Romantic ideals of introspection, solitude, and the boundless power of nature.

- Monk by the Sea (1808–1810): In this work, a solitary monk stands on a desolate beach, facing an endless, turbulent sea under a vast sky. The painting’s stark composition and somber tones evoke a sense of existential solitude, embodying Friedrich’s view of nature as both beautiful and terrifying.

- The Abbey in the Oakwood (1810): This painting depicts a Gothic ruin surrounded by barren trees, with monks carrying a coffin through the scene. The image of the abbey as a crumbling remnant of the past reflects the Romantic fascination with medieval architecture and the passage of time.

Friedrich’s works often evoke a sense of melancholy and reflection, inviting viewers to consider the transient nature of human life and the enduring beauty of the natural world.

Philipp Otto Runge and Symbolic Romanticism

Philipp Otto Runge (1777–1810), though less well-known than Friedrich, made significant contributions to German Romanticism. Runge’s works combined allegory and symbolism with intense color and imaginative compositions, focusing on themes of life, death, and spiritual transformation.

- The Times of Day: Runge’s series of paintings, including Morning, Noon, Evening, and Night, were conceived as part of a larger symbolic project intended to represent the cycles of nature and human experience. Runge believed that art could communicate spiritual truths, and his symbolic approach influenced later Symbolist artists.

- Color Theory: Runge was deeply interested in color and its emotional impact, and he developed theories about the relationships between colors that anticipated modern color theory. His innovative use of color helped shape the expressive, symbolic character of German Romantic art.

Runge’s work, though cut short by his early death, represented an intellectual approach to Romanticism, emphasizing symbolic meaning and mystical exploration.

Romantic Architecture and the Revival of the Gothic Style

Alongside painting, the Romantic movement also influenced German architecture, particularly through the Gothic Revival, which sought to capture the spirit of medieval Germany and reflect the nation’s historic heritage.

- Cologne Cathedral Completion: Originally begun in the Gothic style in 1248, Cologne Cathedral’s construction was halted in the 16th century, but it was revived during the Romantic period as a national project. The Gothic Revival reflected Romantic ideals of faith, national pride, and a connection to the past, and Cologne Cathedral became a symbol of German unity and cultural heritage.

- Castle Hohenzollern: Built in the mid-19th century, Castle Hohenzollern reflects the Romantic fascination with medieval fortresses and fairytale landscapes. Situated on a mountain peak, the castle’s dramatic architecture and picturesque setting embody the Romantic spirit, blending historical nostalgia with a sense of fantasy.

The Romantic fascination with medieval architecture contributed to a resurgence of Gothic-inspired structures throughout Germany, reinforcing a sense of continuity with the past.

The Biedermeier Period: Art for the Middle Class

The Biedermeier period, which overlaps with German Romanticism, refers to a style that emerged in Central Europe from around 1815 to 1848, characterized by a focus on domesticity, simplicity, and the comforts of home. While Romantic art often embraced intense emotion and dramatic landscapes, Biedermeier art reflected middle-class values, focusing on intimate, everyday scenes that celebrated modesty and contentment.

- Portraiture and Genre Scenes: Biedermeier artists painted portraits and genre scenes that captured the quiet dignity and moral values of middle-class life. Artists like Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller portrayed families, children, and rural settings with a sense of warmth and simplicity, contrasting with the often somber tones of Romanticism.

- Interior Design and Decorative Arts: The Biedermeier aesthetic extended to interior design, with furniture and decor that emphasized practicality, clean lines, and comfort. The popularity of Biedermeier style reflected the political and social conservatism of the period, as the middle class embraced stability and order in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars.

The Biedermeier period offered a counterpoint to the more dramatic aspects of Romanticism, celebrating the stability and contentment of everyday life.

Nationalism and the Creation of a German Cultural Identity

As German Romanticism developed, it became closely linked with the rise of nationalism and the desire for German unification. Artists, writers, and intellectuals sought to define a distinct German identity rooted in shared language, history, and folklore, inspiring pride in Germany’s cultural heritage.

- The Brothers Grimm: Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, known for their collection of German folktales, were central figures in the Romantic nationalism movement. Their work not only preserved traditional stories but also promoted a shared cultural identity that resonated with the German people.

- Ludwig van Beethoven: The Romantic composer Beethoven infused his music with themes of heroism and national pride. His symphonies and compositions inspired a sense of unity and cultural pride, contributing to the Romantic movement’s impact on German nationalism.

- Historical Painting and Folklore: Romantic painters often depicted scenes from German history, legends, and mythology, celebrating figures like Charlemagne and Frederick Barbarossa. These works aimed to instill a sense of pride in Germany’s past and inspire a vision of a unified nation.

This nationalistic element of German Romanticism fueled a collective sense of identity, inspiring movements that would eventually lead to German unification in the latter half of the 19th century.

Legacy of German Romanticism

German Romanticism left a profound impact on Western art, literature, and music, establishing a legacy of emotional depth, spiritual exploration, and cultural pride. The Romantic emphasis on individual experience and the sublime beauty of nature set the stage for later movements, such as Symbolism and Expressionism, which continued to explore inner states and spiritual themes.

The Romantic movement’s focus on national identity also influenced Germany’s political landscape, helping to shape a unified cultural identity that would endure through times of upheaval and transformation. Today, the works of German Romantic artists like Caspar David Friedrich remain celebrated for their introspective beauty, while the Gothic Revival architecture and folklore-inspired art of the period continue to embody Germany’s unique cultural heritage.

Realism and Impressionism in Germany (1850–1900)

The late 19th century in Germany saw a shift from the emotional intensity of Romanticism to the grounded, observational style of Realism, a movement that aimed to depict everyday life and social realities without idealization. Realism’s focus on ordinary subjects, such as laborers, domestic scenes, and urban landscapes, reflected the period’s social transformations and rapid industrialization. By the end of the century, German artists had begun experimenting with Impressionism, a style that emphasized light, color, and fleeting moments, marking the beginning of modern art’s exploration of perception and experience.

The Realist Movement: Art as Social Commentary

Realism emerged in Germany as artists turned their attention to the realities of urban and rural life, influenced by similar developments in France. German Realist artists rejected the dramatic emotionalism of Romanticism, instead portraying their subjects with directness, honesty, and empathy. This movement coincided with growing social awareness and critiques of class inequality, poverty, and the impact of industrialization.

- Adolf Menzel: A key figure in German Realism, Menzel (1815–1905) is celebrated for his detailed, almost photographic depictions of Prussian life. His painting The Iron Rolling Mill (1872–1875) portrays the gritty reality of industrial labor, showing workers in a steel factory surrounded by machinery and smoke. The work captures the physical strain and intensity of factory life, reflecting Menzel’s commitment to realism and social observation.

- Wilhelm Leibl: Known for his meticulous attention to detail, Leibl (1844–1900) painted rural life with a deep respect for his subjects. His work Three Women in a Village Church (1882) shows peasant women in traditional dress, rendered with remarkable precision and empathy. Leibl’s dedication to depicting people as they were, without embellishment, exemplifies the values of Realism.

- Max Liebermann: Liebermann (1847–1935) initially embraced Realism before transitioning into Impressionism. His early works, such as Women Plucking Geese (1872), focus on ordinary people engaged in everyday tasks, conveying the dignity of labor and rural life. Liebermann’s use of loose brushwork and natural lighting foreshadowed his later Impressionist style.

German Realist painters sought to convey the authenticity of their subjects’ lives, often focusing on themes of work, family, and community. Their unidealized approach provided a glimpse into the daily experiences of people across social classes.

The Influence of Industrialization and Urbanization

The rapid industrialization of Germany during this period had a profound impact on society and the arts. Cities expanded, factories proliferated, and the landscape of German life was transformed. Artists responded by capturing these changes, both celebrating technological progress and documenting the hardships it brought to workers and urban dwellers.

- Urban Landscapes: The growth of cities like Berlin, Munich, and Hamburg led artists to explore urban settings in their work. Scenes of bustling streets, railway stations, and factories became common, reflecting the energy and tension of modern life.

- Industrial Subjects: Realist artists often depicted industrial scenes, not as symbols of progress but as expressions of labor and resilience. Works like Menzel’s The Iron Rolling Mill highlight the strength and endurance required by industrial laborers, casting a sober gaze on the costs of modernization.

The Realist movement’s focus on industrialization and urbanization provided a new context for German art, as artists confronted both the promises and perils of technological change.

The Transition to Impressionism

In the later 19th century, German artists began to adopt Impressionist techniques, inspired by French painters such as Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Impressionism emphasized the effects of light, color, and atmosphere, focusing on capturing fleeting moments and the sensory experience of a scene. German Impressionism maintained some of the Realist interest in contemporary life but approached it with a lighter, more experimental touch.

- Max Liebermann and German Impressionism: Liebermann became a prominent German Impressionist, known for his depictions of parks, gardens, and beaches. His painting The Birch Grove in the Spring (1900) captures the dappled sunlight filtering through trees, rendered with quick, loose brushstrokes. Liebermann’s work reflects Impressionism’s focus on natural light and its celebration of leisure and outdoor life.

- Lovis Corinth: Known for his energetic brushwork and use of color, Corinth (1858–1925) brought a unique approach to Impressionism, often blending it with Expressionist elements. His paintings, such as The Walchensee series, depict natural landscapes with vivid colors and expressive strokes that convey the emotional impact of the scenery.

- Wilhelm Trübner: Trübner (1851–1917) embraced Impressionism’s emphasis on light and color, capturing scenes of everyday life with a focus on atmospheric effects. His works often feature softer, looser brushstrokes, creating a sense of immediacy and spontaneity typical of Impressionism.

German Impressionism retained the Realist focus on contemporary subjects but emphasized the subjective experience of the moment. This transition to Impressionism allowed German artists to explore new ways of seeing and interpreting the world, setting the stage for modern art.

Themes of Leisure and Modernity

Impressionism in Germany often focused on scenes of leisure, reflecting the newfound interest in capturing moments of relaxation, pleasure, and social life. Parks, beaches, and cafés became popular subjects, illustrating the ways in which urbanization had transformed society.

- Depictions of Parks and Gardens: Liebermann’s series on the Wannsee, a lake in Berlin, captures city dwellers enjoying nature, a common theme in German Impressionist art. These works depict a harmonious relationship between people and nature, emphasizing relaxation and escape from the industrial city.

- Café Scenes and Social Gatherings: German Impressionists also portrayed urban social life, including scenes of people in cafés, theaters, and marketplaces. These works reflect the spirit of modernity, with Impressionist techniques capturing the vibrancy and movement of city life.

Impressionism allowed German artists to engage with contemporary culture, capturing the fluid, transitory nature of modern urban life and its new spaces for leisure and social interaction.

Scientific Exploration and Color Theory

As part of the Impressionist movement’s focus on perception, German artists explored scientific approaches to color, light, and vision. They studied how colors interacted and used innovative techniques to capture atmospheric effects, challenging traditional notions of realism.

- Optical Effects and Brushwork: Impressionist painters often applied paint in small, distinct strokes that, when viewed from a distance, blended to create a cohesive image. This approach allowed them to capture the play of light and shadow in a way that felt immediate and alive.

- Color Theory: German artists experimented with complementary colors, understanding how contrasting hues could enhance one another when placed side by side. This scientific interest in color and light reflected the broader intellectual curiosity of the time and contributed to the unique vibrancy of Impressionist art.

This emphasis on light, color, and scientific observation set Impressionism apart from Realism, offering a new perspective on familiar scenes.

Legacy of German Realism and Impressionism

The Realist and Impressionist movements in Germany provided the foundation for modern art’s exploration of perception, experience, and individual expression. German Realism’s commitment to social observation and honest portrayal of life created a legacy of empathy and authenticity in German art, while Impressionism’s focus on sensory experience introduced new techniques that would shape the next generation of artists.

As Germany entered the 20th century, the innovations of Realism and Impressionism paved the way for Expressionism and other modernist movements, as artists continued to push the boundaries of how art could capture the world. Today, the works of German Realist and Impressionist painters remain celebrated for their ability to reflect both the ordinary and the extraordinary in everyday life, offering glimpses into the social and cultural transformations of their time.

Expressionism and Modernism in Germany (1900–1933)

The early 20th century marked an explosive period of artistic experimentation in Germany, driven by the rapid modernization, urbanization, and sociopolitical changes that shaped the country. German Expressionism emerged as a powerful reaction to the complexities of modern life, emphasizing subjective experience, emotion, and abstraction over realism. Expressionist artists rejected traditional representation, using bold colors, distorted forms, and raw brushstrokes to convey the intensity of human experience. This period also saw the rise of the influential Bauhaus school, which revolutionized design, architecture, and the visual arts with its focus on function, form, and modern aesthetics. Together, Expressionism and modernist movements like Bauhaus positioned Germany at the forefront of avant-garde art, reshaping the trajectory of Western art.

The Rise of German Expressionism

German Expressionism emerged around 1905, primarily through two influential artist groups: Die Brücke (The Bridge) in Dresden and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) in Munich. Expressionism was rooted in a desire to capture the emotional and psychological complexities of modern life, often portraying inner turmoil, existential dread, and the alienation of urbanization.

- Die Brücke: Founded by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Fritz Bleyl, Die Brücke sought to break away from academic tradition and capture the raw, primal energy of modern life. Their works often depicted urban scenes, nudes, and landscapes, using vivid colors, jagged lines, and simplified forms. Kirchner’s Street, Dresden (1908) exemplifies this approach, depicting a bustling city scene with exaggerated colors and distorted figures that evoke a sense of alienation and anxiety.

- Der Blaue Reiter: Formed in 1911 by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, Der Blaue Reiter focused on spirituality, symbolism, and abstraction, with a strong interest in the expressive potential of color. Kandinsky’s Composition VII (1913) is an iconic work of abstract Expressionism, filled with swirling colors and forms that convey intense emotion and spiritual transcendence. Marc’s animal paintings, such as Blue Horse I (1911), used symbolic color and form to express his reverence for nature and critique of modern industrial society.

Both Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter artists sought to push the boundaries of artistic expression, exploring how color, form, and abstraction could communicate deeper emotional and spiritual truths.

Themes and Techniques of Expressionism

Expressionist artists in Germany used distortion, abstraction, and exaggerated colors to convey intense emotional states, often exploring themes of alienation, anxiety, and the search for meaning in an industrialized world.

- Bold Colors and Distortion: Expressionists used unnatural colors and exaggerated forms to intensify emotional impact. Faces, bodies, and environments were often distorted to reflect inner turmoil or existential despair.

- Urban Alienation: Many Expressionist works depicted the modern city as a place of isolation and anxiety. Kirchner’s depictions of Berlin nightlife and bustling city streets reveal a sense of unease, reflecting the psychological impact of urbanization.

- Symbolic Use of Animals and Nature: Franz Marc and other Expressionists turned to nature as a refuge from industrial society, using animals and natural landscapes as symbols of purity and spiritual transcendence. Marc’s use of color had symbolic meaning: blue represented masculinity and spirituality, yellow femininity, and red the destructive forces of modernity.

Expressionism in Germany was driven by a desire to capture the unseen, psychological dimensions of life, setting it apart from other modernist movements focused more on formal experimentation than on emotional content.

The Bauhaus: Revolutionizing Design and Art

In 1919, architect Walter Gropius founded the Bauhaus school in Weimar, Germany, with the goal of uniting art, craft, and industry to create functional and aesthetically harmonious designs for modern life. The Bauhaus played a transformative role in modern art and design, embracing simplicity, abstraction, and a “form follows function” philosophy that would have a lasting impact on architecture, graphic design, and industrial design.

- Integration of Art and Craft: The Bauhaus sought to dissolve the boundaries between fine art and applied arts, emphasizing practical, mass-producible designs that could be accessible to everyone. This approach led to collaborations across disciplines, including architecture, textile design, typography, and metalwork.

- Influential Bauhaus Figures: Key figures at the Bauhaus included Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Josef Albers, Marianne Brandt, and László Moholy-Nagy. Each brought unique contributions, from Klee’s explorations of color and form to Brandt’s innovative metal designs and Moholy-Nagy’s experiments in photography and light.

- Bauhaus Architecture: Bauhaus architecture emphasized functionalism, geometric forms, and minimal ornamentation. The Bauhaus building in Dessau, designed by Gropius, is an iconic example, featuring glass walls, open spaces, and a stark, industrial aesthetic that embodies the school’s modernist principles.

The Bauhaus represented a radical departure from traditional art education, promoting a vision of art and design as integral to everyday life. Despite being shut down by the National Socialist regime in 1933, the Bauhaus’s influence spread worldwide, shaping modernist architecture, design, and art education.

Expressionism in Film and Theater

The emotional intensity of Expressionism also found a home in German film and theater, where it became an influential aesthetic in the 1920s. Expressionist film and theater emphasized mood, atmosphere, and visual distortion to convey psychological states, shaping a distinctive style that would influence genres like horror and film noir.

- German Expressionist Cinema: Films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) by Robert Wiene and Nosferatu (1922) by F.W. Murnau are classics of German Expressionist cinema, known for their surreal set designs, stark contrasts of light and shadow, and themes of madness, horror, and existential dread.

- Max Reinhardt and Theater: The influential theater director Max Reinhardt incorporated Expressionist techniques in his productions, using exaggerated acting styles, bold lighting, and symbolic set designs to convey heightened emotions. Reinhardt’s approach to theater set the stage for later developments in experimental performance art.

Expressionist film and theater reflected the movement’s fascination with the darker aspects of the human psyche, using visual and narrative distortion to explore themes of fear, alienation, and moral ambiguity.

The Social and Political Context of German Expressionism

German Expressionism emerged during a period of significant social and political upheaval, including World War I, the instability of the Weimar Republic, and the economic challenges facing Germany. Artists responded to these conditions with art that often critiqued modern society, questioned authority, and explored themes of despair, revolution, and existential uncertainty.

- The Impact of World War I: Many Expressionist artists were directly affected by the war, which influenced their work with themes of trauma, disillusionment, and anti-militarism. Otto Dix’s disturbing war scenes and George Grosz’s satirical depictions of Weimar society exemplify the Expressionist critique of a fractured, disillusioned world.

- Political Expressionism: Expressionism in Germany often intersected with political commentary. Artists like Grosz and Dix used their work to criticize the corruption and moral decay they saw in post-war German society, reflecting the instability and economic hardship of the Weimar era.

Expressionism thus became a powerful means of social and political expression, offering a raw, unfiltered look at the tensions and anxieties of the time.

Legacy of German Expressionism and Modernism

German Expressionism left an enduring impact on art, film, theater, and architecture, influencing later movements like Abstract Expressionism, Surrealism, and even Pop Art. Expressionism’s focus on inner experience and emotional intensity would resonate with artists and thinkers throughout the 20th century, providing a language for exploring psychological and existential themes.

The Bauhaus, meanwhile, established principles that continue to shape design, architecture, and education worldwide. The Bauhaus approach, which emphasized functionality, simplicity, and integration, has become a cornerstone of modernist aesthetics. Even after the National Socialists closed the Bauhaus in 1933, its faculty and ideas spread internationally, influencing schools, museums, and design movements across Europe and the United States.

Today, the legacy of German Expressionism and the Bauhaus can be seen in art and design that values emotional honesty, abstraction, and a forward-looking approach to form and function. German Expressionist works remain celebrated for their bold, visionary style, while Bauhaus ideals continue to define modern design and architecture.

National Socialist Germany and Art (1933–1945)

The National Socialist era in Germany was a time of strict state control over the arts, as Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist regime sought to eliminate what they considered “degenerate” art and replace it with works that promoted their ideology. The National Socialists viewed art as a tool for propaganda, using it to reinforce their vision of an “Aryan” culture rooted in traditional values, purity, and strength. Modernist movements like Expressionism, Dada, and Surrealism were condemned, and artists who created abstract, experimental, or politically critical works were silenced, persecuted, or forced to flee Germany. In their place, the National Socialists promoted a style known as “Heroic Realism,” idealizing the human form and celebrating themes of nationalism, rural life, and military power.

The Concept of “Degenerate Art”

The term “degenerate art” (Entartete Kunst) was used by the National Socialist regime to describe modern art that did not conform to its ideological standards. Works deemed “degenerate” were associated with Jewish, Communist, or “anti-German” influences and were considered a threat to the National Socialist vision of a pure, traditional German culture.

- Targeted Movements: The National Socialists labeled nearly all modernist movements as degenerate, including Expressionism, Cubism, Dada, Surrealism, and abstract art. Artists like Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner were condemned, as their works challenged the traditional realism and order the National Socialists wanted to impose.

- Confiscation and Destruction of Art: In 1937, the National Socialists confiscated thousands of artworks from German museums and private collections, removing works they deemed degenerate. Many of these artworks were either sold abroad to fund the regime or destroyed.

- Persecution of Artists: Artists associated with modernist movements faced harassment, censorship, and imprisonment. Some, like Kirchner, committed suicide under the pressure, while others fled Germany to escape persecution, finding refuge in countries like the United States and Switzerland.