The land that would become Calgary was never blank or silent. Long before fences, surveyor stakes, or settler drawings mapped its contours, the Bow River Valley echoed with ceremonial rhythms, hunting stories, and the encoded patterns of hide painting and beaded geometry. For thousands of years, the region was home to the Blackfoot Confederacy—comprising the Siksika, Kainai, and Piikani—along with the Stoney Nakoda and Tsuut’ina peoples. These nations created a robust, visually encoded world of ritual, record, and relationship that formed the earliest strata of Calgary’s visual culture. To call this “art history” is both accurate and inadequate: for these peoples, image-making was embedded in ceremony, utility, and land itself—not produced for galleries or critique, but for continuity.

The Painted Rocks and Buffalo Robes

One of the oldest known artistic traditions in the Calgary region is rock painting, most famously preserved in Writing-on-Stone (Áísínai’pi), southeast of present-day Calgary. Though technically outside the city’s boundary, this sacred site was deeply connected to Blackfoot seasonal movements and ceremonial life. Pictographs etched in ochre and iron oxide onto sandstone cliffs depict warriors, battles, horses, and thunder beings—mythic forms that blend history with cosmology. These were not casual illustrations but carefully composed images with social and spiritual weight, often made during vision quests or as mnemonic records of intertribal conflict.

Closer to Calgary proper, buffalo robes served as both canvas and archive. Painted with natural dyes and mineral pigments, these robes recorded hunts, migrations, and winter counts—visual chronicles that could be worn, traded, or used in council. The designs were often symbolic rather than pictorial: a circle for a camp, a series of lines for journeys, abstract patterns that spoke volumes within the oral traditions that accompanied them. A robe might contain decades of tribal history, rendered in shorthand pictography that only trained elders could fully interpret. Unlike European painting, which prized permanence and illusion, these works were portable, ephemeral, and multi-functional.

Visual Traditions of the Niitsitapi Confederacy

The Blackfoot worldview was visually rich and structurally formal. Tipi designs, for instance, followed rules of composition passed down matrilineally. The painted tops of tipis—often featuring crescents, dots, or thunderbirds—were more than decoration. They marked ownership of specific dreams or vision powers and distinguished families within the larger camp circle. These visual systems were understood communally and changed slowly over time, with new designs rarely introduced without ceremonial authorization.

Ceremonial objects were equally meticulous. Medicine bundles—wrapped caches of sacred items used in major Blackfoot ceremonies—often included painted skins, feather arrangements, and small sculptures. While these items were not “artworks” in the Western sense, they represented the highest order of sacred craft, intended to maintain balance between human and spiritual realms. Materials were chosen with precision: elk hide, porcupine quills, horsehair, and natural pigments like ochre or charcoal. Each element carried cosmological weight.

Perhaps most significantly, the Blackfoot and their allies maintained large-scale earthworks and ceremonial sites tied to the geography around Calgary. The most famous is the Blackfoot Crossing near present-day Cluny, but buffalo jumps and vision quest sites surrounded the Bow Valley, and some, now buried or paved over, once functioned as enormous performative landscapes. These sites reveal a people deeply attuned to the visual and symbolic power of place.

Three surprising details often missed in settler accounts of pre-Calgary visual culture:

- Quillwork, not beadwork, was the dominant decorative form prior to European contact; dyed porcupine quills were flattened, wrapped, and stitched into hides with remarkable delicacy.

- Horse iconography appeared rapidly in robe and shield painting after horses arrived in the 1700s—an aesthetic shift that accompanied tactical and spiritual transformations in Plains warfare.

- Hide painting declined sharply after the Canadian government’s bison extermination policies in the late 1800s, not due to artistic stagnation, but because the primary canvas—buffalo hide—was nearly eradicated.

From Sacred Sites to Survey Lines

The collapse of the buffalo herds in the 1880s, driven by both American and Canadian policy, devastated the material foundations of Canadian Indian artistic traditions in the Calgary region. The signing of Treaty 7 in 1877 marked a formal cession of territory but also a profound disjuncture in cultural transmission. Painted robes gave way to ration lines; quillwork was displaced by imported glass beads; seasonal mobility was replaced by permanent reserves and enforced schooling. The land itself was redrawn in grids, its spiritual topography overwritten by Dominion surveyors.

Still, visual tradition did not vanish. Many Blackfoot families preserved painted designs in ledger drawings—new formats made with pencil and pen on lined or gridded paper, salvaged from bureaucrats or military officers. These works translated the fluid symbolism of robes into rigid formats, but the impulse to record, narrate, and stylize remained. In some cases, Canadian Indian artists repurposed the tools of colonial administration into ironic or coded records of defiance. A 1902 ledger drawing by a Siksika man known only as “George” depicts a mounted warrior overtaking a Northwest Mounted Police patrol—rendered in tight pencil strokes with unexpected humor and clarity.

Even as Calgary grew into a settler city, its foundations were layered atop a world thick with image, memory, and meaning. That world was never silent. It spoke through petroglyphs, ceremonial bundles, hide paintings, and tipi designs—and continued, subtly but insistently, through adaptations, survivals, and quiet acts of resistance. Long before Calgary was a name, it was a pattern. Not carved in stone, but painted on moving hide, read aloud around fires, and danced under the open sky.

Colonial Frontiers and Settler Imaginaries (1870s–1914)

The early decades of Calgary’s settler history produced an aesthetic that was less about artistry than assertion. As surveyors, traders, missionaries, and military officers arrived in what was then still the North-West Territories, they brought with them not only the tools of governance and commerce, but a visual language of dominion. The settler eye was restless, trained to see in acreage, vistas, and elevation charts. From the 1870s through the first two decades of the 20th century, Calgary’s artistic output—such as it was—reflected a town trying to justify its own existence: visually modest, economically anxious, and spiritually tethered to a British imagination of order. But even in this embryonic moment, seeds were planted for the institutional and thematic concerns that would shape the city’s artistic character for the next century.

Surveyors, Homesteaders, and the Watercolour Gaze

The first visual impressions of the Calgary area made by European settlers were functional, not expressive. Dominion Land Survey maps, drawn with astonishing regularity in the 1870s and 1880s, broke the landscape into one-mile square blocks—a transformation more philosophical than cartographic. These maps were austere and unadorned, but they reimagined the prairie as a blank slate, ripe for rationalized development. Any visual remnants of American Indian geography—buffalo jumps, trails, medicine wheels—were either omitted or rendered as quaint curiosities.

Alongside these technical renderings emerged a quieter genre: the amateur watercolour. Officers in the North-West Mounted Police, Anglican missionaries, and settler wives often painted what they saw in their new surroundings, creating a visual record of encampments, railway trestles, and open prairie. One such painter, Reverend John McDougall, known more for his missionary work among the Stoney than for his art, left a series of delicate watercolours showing tipi camps fading into the background behind mission buildings and rail lines. The tension is unspoken but acute.

These early works were often governed by a contradiction: they tried to capture the grandeur of the western landscape while simultaneously reducing it to manageable, domesticated forms. The result was a visual genre of settler pastoralism, populated by lonely fences, tent poles, and smoke trails. In them, the prairie was both a spiritual void and a field of promise.

Banff as a Muse and Mirage

The discovery of hot springs near Banff in the 1880s and the subsequent establishment of Canada’s first national park introduced a new dimension to the visual culture of the region: the landscape as spectacle. Though technically 120 kilometers from Calgary, Banff functioned as its romantic twin—the site where the wildness of the Rockies could be staged, sold, and framed. The Canadian Pacific Railway, which reached Calgary in 1883, actively encouraged this mythmaking. It commissioned photographers and painters to produce views of the mountains that would lure tourists, investors, and settlers.

One of the most significant figures in this movement was Lucius O’Brien, first president of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. His 1886 painting Mountain Lake (Lake Louise) became a symbol of alpine purity and imperial achievement, reproduced widely in promotional materials. While O’Brien never lived in Calgary, his work helped define how its surrounding landscapes were visualized—sublime, empty, and waiting. The mountains were not shown as lived-in places, but as untouched majesty, mirroring Romantic landscape traditions imported wholesale from Britain and the Hudson River School.

Artists working closer to Calgary—such as Belmore Browne and Carl Rungius—were drawn more to wildlife and sporting imagery. Rungius in particular made a name for himself painting bighorn sheep and grizzly bears in almost hyper-real detail. These paintings, often commissioned by American and European collectors, fused natural history with masculine fantasy. The wild was to be observed, dominated, and eventually mounted on a wall.

Banff thus became a paradoxical site: a place where Canadian art flirted with international standards, even as it ossified a colonial vision of the West as pristine and depopulated.

Calgary’s Early Studios and the Birth of Art Clubs

Back in Calgary, the town was growing rapidly—from a frontier outpost to a small but self-consciously modern city. By 1911, its population had reached 43,000, and with that growth came the first organized artistic activity. Much of it was conservative in tone, mirroring the tastes of Calgary’s commercial elite. Photography studios were the most prolific visual enterprises. The Livermore Brothers, for instance, opened one of the first photographic studios in Calgary in the 1880s, producing posed portraits of settlers, mounted police, and businessmen—always against neutral backdrops, with minimal staging. Their work is emotionally restrained, but invaluable as a visual archive of social ambition.

By the early 20th century, amateur art societies had begun to form. The Calgary Sketch Club, founded in 1909, brought together teachers, housewives, and civil servants who painted landscapes and still lifes on weekends. Their output—mostly in oil or pastel—was rooted in Victorian traditions: orderly, sedate, and often framed in heavy gold. One of its early members, Laura Evans Reid, was notable not only for her work but for her insistence that Calgary deserved a public gallery. Her efforts, though slow to bear fruit, laid the groundwork for what would eventually become the Glenbow.

These early clubs functioned as both social networks and cultural claims. They provided legitimacy to a community eager to shake off its frontier image and present itself as tasteful, educated, and settled. But they also revealed the limitations of that aspiration. Calgary’s art scene, in these years, was almost entirely derivative. It borrowed from Toronto, London, and occasionally New York, but rarely challenged prevailing conventions.

Three recurring motifs in early settler Calgary art and photography:

- Fenced land as progress: Whether in drawings, photos, or paintings, fences often symbolized control over nature—visually dividing wildness from “improvement.”

- Single figures in vast space: Echoing Romantic tropes, artists often placed solitary cowboys or police officers against expansive skies, suggesting heroic isolation.

- Tipis in the distance: Often included as background detail in otherwise settler-centric images, tipis functioned as ambiguous symbols—either nostalgia or exoticism, rarely humanity.

Calgary, in these years, had no dedicated gallery, no formal art school, and little sense of itself as a cultural center. Yet the groundwork was being laid. Aesthetic traditions were being imported, adapted, and occasionally interrupted. The contrast between settler pastoralism and the theatrical grandeur of Banff would become a recurring tension in Alberta art. And as Calgary transitioned into a modern city, those tensions would come to shape both its institutions and its artists.

Modernity on the Prairie: 1914–1945

The arrival of modernity in Calgary was not a thunderclap but a slow, uneven hum—filtered through oil booms, war efforts, and the stubborn persistence of frontier mythology. Between 1914 and 1945, the city’s visual culture matured, fragmenting into multiple aesthetic currents that reflected the tensions of prairie life. This was the era of grain elevators turned icons, schoolteachers who moonlighted as artists, and landscapes that blurred into abstraction under the weight of national identity. Calgary’s art scene remained peripheral to the power centers of Toronto and Montreal, but its artists developed a regional voice marked by endurance, dryness, and a stubborn lyricism rooted in the land.

The Grain Elevator as Icon

Nowhere was this new visual language more evident than in the treatment of prairie architecture—especially the grain elevator. Often dismissed by early European visitors as “ungainly” or “monotonous,” these towering wooden structures soon became central to the visual vocabulary of prairie modernism. They stood like sentinels against a flattened horizon, emblems of utility that inadvertently flirted with minimalism. Artists such as Walter J. Phillips and H.G. Glyde began to treat them not as industrial eyesores but as sculptural forms: precise, rhythmic, and strangely dignified.

Phillips, though more closely associated with Winnipeg and the Banff School, visited Calgary frequently and produced woodcuts that distilled prairie elements into Japanese-influenced compositions. His 1930s prints—tight, clean, and emotionally restrained—conveyed the harsh clarity of Alberta light and the formal grace of its most functional buildings. Unlike the romantic mountain scenes marketed by railway companies, Phillips’ prairie works embraced absence and repetition: a single grain elevator casting its long shadow, a windbreak of trees marching into the distance.

In oil painting, artists like Illingworth Kerr pushed this aesthetic further. Kerr, who would later become a towering figure in Alberta’s art education scene, began to experiment in the late 1930s with stylized landscapes that merged European modernism with prairie subject matter. In his canvases, the geometry of the land was emphasized over its prettiness. Barns became angular planes; skies flattened into bands of ochre and steel blue.

The elevation of such utilitarian structures to the status of subject matter marked a turning point: prairie artists were no longer trying to mimic the grandeur of the Rockies. They were finding meaning in monotony, rhythm in harshness. It was a visual strategy born of necessity, but one that matured into aesthetic conviction.

Emma Lake and the Prairie Modernists

Though located in Saskatchewan, the Emma Lake workshops profoundly shaped Alberta’s artistic development in this era, creating a network of prairie modernists whose influence would radiate back into Calgary’s institutions. Founded in 1936 and growing in stature after World War II, the workshops attracted painters, critics, and teachers from across Western Canada. Calgary-based artists traveled north to take part in critiques, demonstrations, and collaborative experiments that placed formal innovation above regional cliché.

This was a quiet revolution. It didn’t seek headlines or cultural dominance, but it seeded a new kind of artistic seriousness in a region long dismissed as provincial. Painters like Marion Nicoll—who began her career in Calgary as a teacher—found in this milieu a freedom to experiment with abstraction and formal structure. Nicoll’s early work in this period remained largely representational, but her exposure to Emma Lake’s environment of disciplined innovation prepared her for the bold abstractions she would produce in the 1950s and beyond.

The prairie modernists were united not by style but by temperament: austere, methodical, and resistant to both romantic nationalism and imported trends. Their work refused spectacle. In its place, they offered a slow-burning attentiveness to line, form, and the subtleties of a dry, demanding geography. They were modernists by necessity—stripping the land of sentimentality to reveal its structural core.

Three distinct qualities defined the prairie modernist sensibility as it took shape across Alberta:

- Economy of form: whether in painting or print, artists avoided flourish and focused on compositional integrity.

- Local materials, global methods: linocuts, woodblocks, and tempera were favored for their accessibility and tactile control.

- A resistance to narrative: images became less about telling stories and more about arranging space, light, and rhythm.

This was not yet a “movement,” but it was a vocabulary in the making—one that would flourish in the postwar decades.

The Depression, Nationalism, and Artistic Survival

The Great Depression struck Alberta with particular cruelty. Droughts, falling grain prices, and political volatility hollowed out rural economies and forced thousands into precarious urban employment. For Calgary’s small community of artists, the 1930s were defined by scarcity and improvisation. Yet paradoxically, these lean years also encouraged artistic organization and ambition. The need to collectivize—whether in art clubs, teaching circles, or civic exhibitions—helped solidify Calgary’s early cultural infrastructure.

The Calgary Allied Arts Council was founded in 1931, largely in response to these pressures. It provided a coordinating body for artists, musicians, and writers to stage exhibitions and press for civic support. Their events, held in school basements, hotel ballrooms, and eventually the Calgary Public Library, were modest but determined. Unlike the elitist academies of central Canada, these gatherings were often democratic and cross-disciplinary. An oil painter might share wall space with a quilter or a silversmith. It was art without pretension—sometimes awkward, often heartfelt.

National identity also played an increasing role in shaping Calgary’s art scene during these years. The federal government’s support for arts and culture, though limited, began to filter westward through traveling exhibitions and small grants. The National Gallery of Canada sent curated shows to Calgary by train, exposing local audiences to the Group of Seven and their successors. These exhibitions had a double effect: they legitimized Canadian art as a serious enterprise and provoked local artists to measure themselves against central standards.

Some rebelled against the nationalist imagery—endless forests, northern lakes, and rugged hills—that had come to define “Canadian” landscape painting. Others adapted its lessons to the prairie context. The result was an evolving dialogue between place and identity, one in which Calgary artists began to see themselves not merely as regional voices, but as participants in a national project.

By the time World War II arrived, Calgary’s artistic identity had solidified in its contradictions: formally restrained but conceptually ambitious, regionally rooted yet increasingly cosmopolitan. The war would disrupt much—drawing artists into service, curtailing exhibitions, and redirecting civic funds—but the foundations had been laid.

Art was no longer an imported pastime or a decorative indulgence. It was a mode of seeing that made life on the prairie not only intelligible but meaningful. It offered discipline, abstraction, and—perhaps most importantly—a way of enduring.

The Banff School and the Rise of an Institutional Scene

By the mid-20th century, Calgary’s art scene was no longer merely the domain of hobbyists or isolated modernists. It was becoming institutional—anchored by schools, summer programs, and a growing recognition that the West deserved more than passing notice in national conversations about art. Central to this shift was the Banff School of Fine Arts, which—though located outside Calgary proper—functioned as its gravitational hub. The relationship between Banff and Calgary was not merely geographic but ideological: Banff provided the pedagogy and prestige, Calgary the audience, infrastructure, and long-term commitments. Through a slow and sometimes awkward maturation, this partnership began to define how art would be taught, made, and exhibited in Southern Alberta for the next half century.

Walter Phillips and the Landscape Reimagined

The single most influential figure in this institutional transformation was Walter J. Phillips. A British-born printmaker who settled in Winnipeg before joining the Banff School faculty in the 1940s, Phillips helped forge a distinctly Western Canadian approach to landscape art. While best known for his elegant woodcuts of lakes, mountains, and alpine forests—works that fused Japanese print techniques with Arts and Crafts idealism—his impact extended far beyond his studio.

Phillips’ philosophy was rooted in discipline and observation. He taught students to draw what they saw, not what they imagined, and to respect the tactile properties of their materials. His classes at Banff emphasized line, tonality, and negative space, with none of the expressive indulgence that would characterize later movements. But there was no austerity in his teaching—only rigor. Phillips believed that technique was not a limitation but a mode of attention, a way of honoring place without sentimentality.

Importantly, Phillips viewed the mountains not as sublime spectacles, but as structures to be measured and understood. His works rarely indulged in drama. Instead, they offered precise, often intimate scenes: a lone canoe on Lake O’Hara, the curve of a pine against distant rock. His landscapes were not metaphors—they were studies. And in that restraint, they offered a radical alternative to both the nationalistic sweep of the Group of Seven and the romantic kitsch that saturated Banff postcards and railway brochures.

When the Walter Phillips Gallery was later founded at the Banff Centre in 1976 (named posthumously), it formalized his legacy and signaled Banff’s increasing role in shaping serious, contemporary art discourse in Canada. For Calgary artists and educators, the Banff School was no longer a summer retreat; it was a proving ground.

The CMA’s Forerunner and the Role of Travel Exhibitions

While Banff provided critical mass, Calgary’s own institutions were also evolving. The city lacked a major public gallery for much of the early 20th century, but it did have proto-institutional spaces where art was shown, taught, and debated. Chief among them was the Calgary Public Library, whose basement and lecture halls hosted regular exhibitions organized by the Alberta Society of Artists (founded in 1931) and the Calgary Allied Arts Council.

These exhibitions were often modest in scope but ambitious in intention. They included local oil paintings, drawings, and even textile works, but they also featured traveling exhibitions from the National Gallery of Canada and later, the Canadian Arts Council. These traveling shows were crucial—they introduced Calgary audiences to national and international art that would have otherwise remained invisible. In 1946, for example, a traveling exhibition of British war art drew large crowds and prompted spirited debates in the local press about realism, nationalism, and the role of art in public life.

A notable forerunner to today’s Calgary Municipal Art Collection was the series of public acquisitions made during these decades by city council and local cultural boards. Though eclectic and often influenced by boosterism, these purchases formed the core of what would become a civic art identity. They signaled that Calgary was no longer just consuming art—it was collecting it, shaping it, and integrating it into the built environment.

Three revealing patterns emerge in Calgary’s institutional development during this period:

- Libraries as galleries: Public libraries often doubled as art venues, blurring lines between education and exhibition.

- Art as civic pride: Paintings were purchased not just for aesthetic reasons but to affirm Calgary’s status as a “real” city.

- Persistent gender imbalance: Though many women were active as artists and organizers, their work was underrepresented in official acquisitions.

The art being shown in Calgary was not yet avant-garde, but it was becoming regular, visible, and public. That shift—from occasional display to sustained institution—would prove foundational.

Art as Tourism, and Tourism as Art

Even as Calgary’s institutional life deepened, it remained tied—economically and symbolically—to Banff and the tourism industry that framed the Rockies as Canada’s crown jewel. This relationship was fraught. On one hand, tourism brought infrastructure, funding, and audience. On the other, it risked reducing art to décor: pleasant images for hotel lobbies, mementos for international visitors, or promotional fodder for railway advertisements.

The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), long a patron of mountain imagery, continued to commission artworks for its resorts and promotional campaigns. Artists like Peter and Catharine Whyte, who lived and worked in Banff, became central to this effort. Their paintings—highly detailed, romantic renderings of the Rockies—were widely exhibited and commercially successful. The Whyte Museum, founded in the 1950s, began as a private collection but gradually expanded into a major cultural institution, preserving both art and archives related to mountain life.

The problem was one of control. Tourism demanded legibility: landscapes that soothed, impressed, or reassured. But artists—especially younger ones emerging from institutions like the Banff School—wanted more freedom to interrogate, distort, or abstract their surroundings. The conflict between commercial image-making and independent practice became one of the defining tensions in Alberta art.

By the late 1940s, that tension had produced a new kind of ambition. Calgary artists were no longer content to serve as regional decorators. They wanted recognition, rigor, and relevance. And with institutions now in place to support their development—from summer programs to public collections—that ambition was no longer misplaced.

Calgary was still a young city in cultural terms, but it had found its structure: Banff for training, the city for exhibition, and a shared sense—however nascent—that the prairie was not a void but a vantage point.

1960s Boomtown Aesthetics

In the 1960s, Calgary stopped pretending it was a provincial town. Oil money surged through the streets, concrete towers climbed into the prairie sky, and a new class of professionals demanded not just infrastructure, but culture. The city’s art scene, long an amateur’s enclave and teacher’s sideline, suddenly found itself swept into modernity. This was the era when serious galleries were founded, art began to appear in government buildings and boardrooms, and Calgary’s artists started to see themselves as part of something larger than a local club. But boomtown aesthetics came with contradictions: opulence mixed uneasily with avant-garde ideals, and institutional expansion often clashed with the raw experimentation stirring among younger artists.

Oil, Money, and the Patronage of Ambition

The most immediate impact of the postwar oil boom was capital—and its trickle into culture. By the early 1960s, Calgary had become a corporate city. Head offices of petroleum companies filled downtown towers, and with them came executives eager to display cultural sophistication. Corporate art collections were no longer reserved for Montreal or Toronto. Calgary firms began acquiring large paintings, commissioning sculptures, and even sponsoring exhibitions.

This patronage reshaped what kinds of art got made and shown. Abstract painting, which had once seemed remote or academic, now suited the taste of boardrooms—large, colorful, non-representational works that connoted modernity without controversy. Artists like Takao Tanabe, whose early landscapes evolved into hard-edged abstractions, found willing buyers among Calgary’s corporate collectors. For a brief moment, modernism and commerce seemed aligned.

But the deeper shift was infrastructural. The Alberta College of Art (as it was then called) expanded its programs, and in 1961 the Allied Arts Centre opened downtown, housing studios, exhibitions, and classrooms under one roof. Though modest by national standards, it was a declaration: Calgary would no longer outsource its cultural labor. Art would be made, taught, and shown here, on its own terms.

Even city hall got involved. Municipal budgets began to include line items for public art, and the first stirrings of an official cultural policy emerged. The city purchased works for its offices and libraries, hosted outdoor exhibitions, and tentatively supported new galleries. Civic pride now included aesthetics. Concrete wasn’t enough—it had to be adorned.

Still, this new money brought its own aesthetic: polished, abstract, inoffensive. It reflected Calgary’s self-image at the time—efficient, upwardly mobile, and vaguely cosmopolitan. The wildness of the landscape, the grit of labor, the cultural memory of American Indian nations—these remained largely absent from the glossy surfaces that defined the era’s corporate art collections.

Artist Collectives and the Calgary Group

If the boardroom aesthetic was sleek and sanitized, the artist-run spaces that began to emerge in the 1960s offered something very different: critique, experimentation, and community. Foremost among these was the Calgary Group—a loose collective of artists who, while not formalized in structure, shared a commitment to challenging local conservatism.

Among its key figures were Marion Nicoll, Maxwell Bates, and John Snow. Each came from different backgrounds—Nicoll from education and abstraction, Bates from architecture and expressionism, Snow from printmaking and civil service—but together they created a critical mass. Their work was not uniform, but it shared a seriousness of purpose and an openness to international trends.

Nicoll’s transition from prairie realism to bold, gestural abstraction was emblematic of the city’s cultural pivot. Her later works, created in the 1960s, used color and form not to represent landscape but to evoke rhythm and space. Bates, by contrast, maintained a commitment to figuration, but his figures were distorted, haunted—more influenced by German Expressionism than by Alberta vistas. His paintings of angular, anxious faces reflected not the city’s oil-fueled optimism, but its psychological undercurrents.

John Snow, a self-taught master of lithography, transformed his home into a studio where many of Calgary’s modernists learned to print. He collaborated with Nicoll and Bates, and his technical precision made him a central figure in Calgary’s printmaking renaissance. Snow’s legacy was both artistic and infrastructural: he preserved and passed on techniques that allowed Alberta’s print culture to thrive beyond hobbyism.

Together, these artists pushed against the boundaries of what Calgary art had been. They were not content with polite landscapes or decorative abstraction. Their work was inward, sometimes confrontational, always thoughtful. They hosted salons, taught workshops, and mentored younger artists. If Calgary was developing an art scene, these were its first serious builders.

Three ways the Calgary Group diverged from the city’s mainstream cultural institutions:

- Material experimentation: embracing collage, mixed media, and unconventional printing techniques over oil-on-canvas orthodoxy.

- Political ambivalence: engaging with Cold War unease and urban alienation rather than celebrating prosperity or patriotism.

- Cross-disciplinary exchange: blending visual art with literature, music, and architecture, particularly in informal studio gatherings.

Though never institutionalized in name, the Calgary Group left an imprint on every artistic structure that followed.

Brutalism, Exhibition Spaces, and Urban Modernity

As Calgary’s skyline changed, so too did its interiors. The Brutalist architecture that dominated the 1960s—characterized by exposed concrete, sharp geometries, and modular design—became both a canvas and a container for contemporary art. The new downtown library, the university campus, the Glenbow-Alberta Institute (opened in 1966)—all offered walls, halls, and atriums where art could exist at scale.

This shift toward monumentality—toward buildings designed to signify modernity—was mirrored in art installations that embraced space and scale. Sculptors like Katie Ohe, whose kinetic pieces responded to light and motion, found homes in these new environments. Her 1962 piece Octo combined industrial materials with elegant movement, standing in quiet opposition to the static grandiosity of much corporate art.

The University of Calgary’s art department also expanded during this period, attracting young faculty with international training. While still tethered to Banff’s seasonal pull, the university began to offer a more sustained context for critical theory, studio practice, and interdisciplinary collaboration. Visiting artists and scholars brought global ideas to the prairie, challenging students to think beyond regional identity.

By the end of the decade, Calgary had multiple exhibition venues, a growing public collection, and a small but vibrant community of serious artists. It also had tensions: between commerce and critique, between regionalism and internationalism, between abstraction and representation. These tensions weren’t failures—they were the marks of a maturing city, trying to figure out what kind of culture could grow in concrete, glass, and wind.

Calgary in the 1960s wasn’t an artistic capital. But it was no longer a cultural backwater either. It had entered the era of institutions—not yet secure in its identity, but no longer content to borrow someone else’s.

Art College to Art Engine: ACAD and Its Influence

In Calgary, art education has long played an outsized role in shaping the city’s cultural life. Nowhere was this more evident than in the rise of the Alberta College of Art—later the Alberta College of Art and Design (ACAD), and today Alberta University of the Arts (AUArts). During the second half of the 20th century, ACAD evolved from a modest vocational program into one of Canada’s most respected art schools. But its influence extended far beyond curriculum or credentials. It became a crucible of experimentation, a home for pedagogical risk, and a flashpoint for debates about craft, concept, and the purpose of art in a city shaped by commerce. To understand how Calgary’s visual culture came into its own, one must look not just at what ACAD produced, but at how it thought.

An Institute in Flux

ACAD’s origins stretch back to 1926, when it was established as a department within the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art. For decades, it remained a hybrid institution—part trade school, part fine art academy—offering courses in drafting, commercial illustration, and practical design alongside more traditional artistic disciplines. This dual character created tensions, but it also laid the groundwork for a school uniquely positioned to navigate Calgary’s pragmatism and creative ambition.

The 1960s and 70s marked a period of profound change. As modernist art gained institutional traction in Canada, ACAD expanded its offerings in sculpture, painting, and printmaking. Its faculty included practicing artists with national reputations—many of whom had studied abroad or at Banff and brought back international techniques, ideas, and critiques. Among them, Marion Nicoll (who began teaching at ACAD in 1937 and became full-time faculty in 1946) stood out as a transformative figure. Her insistence on discipline, formal innovation, and the legitimacy of abstraction made her both revered and controversial.

By the early 1980s, ACAD had gained independence from the technical institute and began the slow process of redefining itself as a stand-alone art college. Its student body grew, its curriculum expanded, and its reputation strengthened. But the institution remained in flux—torn between a commitment to traditional craft and a growing desire to embrace conceptualism, new media, and critical theory. That friction was not a weakness; it became a generative force.

Three factors that distinguished ACAD from other Canadian art schools during its most formative years:

- Its embeddedness in a commercial city, which meant students constantly navigated the divide between artistic autonomy and economic survival.

- Its connection to Banff, which brought in high-caliber visiting artists and exposed students to cutting-edge practices.

- Its studio-based pedagogy, which resisted the purely theoretical approach of some eastern institutions and kept making at the core of learning.

This hybridity—at once elite and practical, local and international—defined ACAD’s institutional character. It also made it a proving ground for debates that shaped the wider Calgary scene.

Notable Faculty, Alumni, and Pedagogical Experiments

ACAD’s impact is best measured through the people who passed through its halls—teachers who built programs from scratch, students who pushed boundaries, and cohorts that coalesced into movements. The list is long, but a few figures stand out.

Katie Ohe, who joined the faculty in the 1970s, brought with her a deep knowledge of sculpture and kinetic form. Her emphasis on motion, materiality, and technical precision shaped generations of sculptors who saw no contradiction between engineering and poetry. Ohe’s legacy is visible not just in her own work, but in her students’—many of whom went on to populate Calgary’s public art collections and university faculties.

John Will, who taught at ACAD from 1971 to 1992, introduced a very different sensibility: irreverent, political, and conceptually sharp. A painter and printmaker whose work often incorporated language, Will was a bridge between high modernism and postmodern critique. He challenged students to question authority, embrace irony, and blur disciplinary boundaries. His influence can be seen in Calgary’s enduring appetite for text-based art and visual wit.

Alumni like Chris Cran (known for his technically virtuosic but intellectually slippery paintings) and Ron Moppett (a collage-based painter who helped define Calgary’s postmodern palette) exemplify ACAD’s ability to produce artists fluent in both technique and subversion. Cran’s work, which toys with perception, pattern, and viewer expectation, is both seductively decorative and quietly critical. Moppett, meanwhile, has remained a fixture in the Calgary scene—as both artist and curator—blending formal beauty with visual riddles.

Pedagogically, ACAD was unusually open to experimentation. Studio critiques were central, but students were also encouraged to work across media, organize their own exhibitions, and collaborate with peers in other disciplines. Interdisciplinary practice—long a buzzword elsewhere—was simply how ACAD operated. The school’s architecture helped: its layout encouraged circulation, visibility, and shared space, which fostered a culture of conversation and critique.

By the 1990s, ACAD had positioned itself as a regional powerhouse. Its graduates filled artist-run centers, public galleries, and teaching posts across Alberta and beyond. The school’s impact was no longer hypothetical—it was visible in the texture of the city’s art itself.

The Duality of Craft and Concept

One of the defining tensions in ACAD’s evolution—and in Calgary’s wider art scene—has been the push and pull between craft and concept. On one hand, ACAD has long emphasized technical skill: printmaking, ceramics, drawing, and sculpture have remained strongholds of instruction, rooted in tactile knowledge and material fluency. On the other, the rise of conceptual art—especially from the 1980s onward—challenged the primacy of the object and foregrounded idea over execution.

Rather than choosing one side, ACAD found ways to stage this tension productively. The school became known for producing artists who could move between disciplines, combining handwork with critical commentary. This was particularly evident in the resurgence of printmaking and book arts—media that married precision with subversion. Students produced limited-edition books that looked antique but delivered biting social critique; they used lithography to reproduce not nature scenes but consumer labels and corporate logos.

Craft wasn’t abandoned—it was weaponized.

This duality also reflected the city itself. Calgary’s economy demanded practicality, but its artists insisted on imagination. ACAD graduates often had to straddle that divide—producing gallery work while designing for festivals, teaching while building collectives, freelancing while developing long-term conceptual projects. The art school didn’t just train artists; it trained cultural workers capable of navigating a city that valued efficiency over ambiguity.

By the turn of the millennium, ACAD had helped produce a new kind of artist: critically engaged, materially fluent, and regionally conscious without being parochial. Calgary’s art scene owed much to its institutions, but its pulse—its risk, its weirdness, its grit—came in large part from the creative frictions that ACAD fostered.

Alberta’s Cowboy Pop and the Politics of Regionalism

Somewhere between irony and sincerity, kitsch and critique, Alberta’s visual culture began to flirt with its own clichés. Nowhere was this more sharply felt than in Calgary, where the myth of the cowboy—the rodeo star, the lone horseman, the swaggering ranch hand—loomed large over the cultural imagination. For much of the 20th century, this imagery had been embraced uncritically by tourism campaigns, souvenir shops, and heritage festivals. But beginning in the 1970s and intensifying into the 1980s and 90s, a group of Calgary artists began to wrestle with this regional iconography in stranger, smarter ways. What emerged was a kind of “cowboy pop”—not a cohesive movement, but a tendency to engage with the symbols of the West using the tactics of postmodern art: repetition, exaggeration, détournement, and irony.

This approach did more than rebrand the cowboy—it reframed Alberta’s regional identity as something mutable, contested, and deeply aesthetic.

Bucking Icons and Rodeo Realism

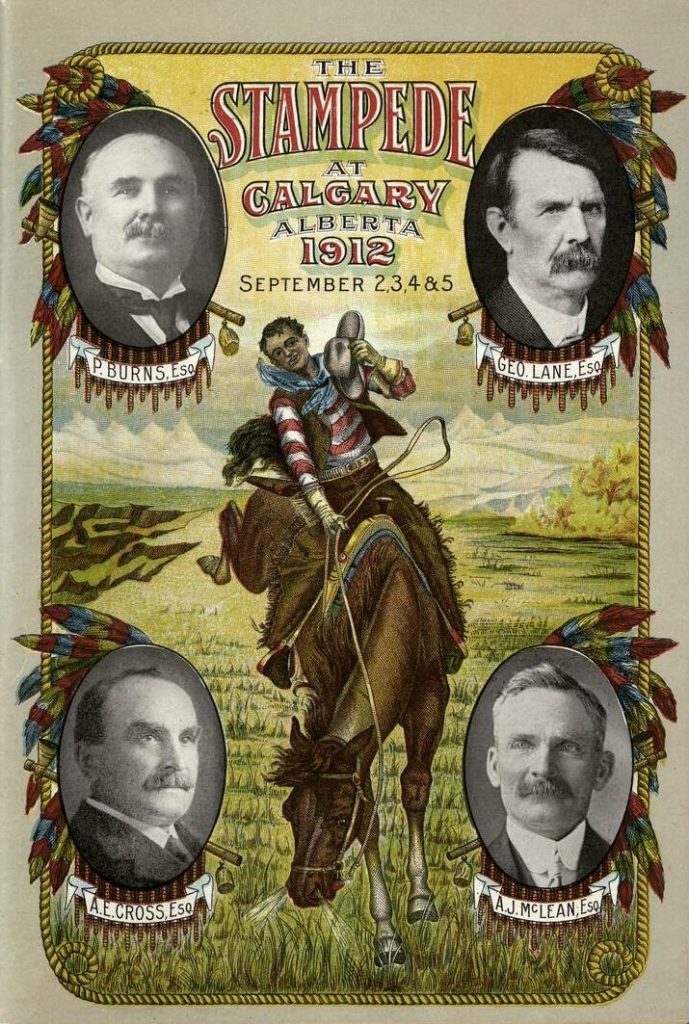

The Calgary Stampede, founded in 1912 and massively expanded after World War II, has long served as the most potent symbol of Calgary’s self-mythologizing. Billed as “The Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth,” it became a visual spectacle as much as a cultural ritual: belt buckles gleamed, horses thundered, and visitors from around the world consumed an aggressively cheerful version of Western Canada. Artists were not exempt. For decades, local painters churned out rodeo scenes, Western landscapes, and heroic portraits of mounted police—all carefully marketable to tourists, collectors, and municipal buildings.

By the 1970s, however, a shift was underway. Artists began turning their gaze inward—not to reject cowboy iconography, but to interrogate it. They painted it again and again, pushing it toward caricature or collapse. Some treated the cowboy not as a hero, but as a mascot—an empty vessel that could carry everything from nationalism to nostalgia to male anxiety.

One of the most intriguing figures in this moment was David Thauberger, a Saskatchewan-based artist whose impact rippled into Calgary through exhibitions and shared sensibilities. His paintings of grain elevators and roadside attractions adopted the flat, frontal style of folk art but carried a subtle conceptual bite. In Calgary, painters like Chris Cran and John Hall took a similar approach: their images, often photorealistic on the surface, carried layers of tension beneath. Hall’s hyper-detailed renderings of objects—often consumer goods, pop cultural flotsam, or Western tropes—juxtaposed surface clarity with deeper ambiguity.

Cran, in particular, became known for using visual illusion and stylistic mimicry to question the act of seeing itself. His works from the 1980s and 90s included cowboy hats, plaid shirts, and Marlboro-man stylings—but always doubled, flattened, or slyly distorted. He wasn’t painting Alberta’s self-image; he was mirroring it back, slightly off-kilter, forcing viewers to reconsider what they were consuming.

Three qualities distinguish Calgary’s “cowboy pop” moment from more straightforward Western art:

- Reflexivity: artists referenced the genre’s tropes while revealing their constructedness.

- Surface versus subtext: polished technique disguised subversive commentary.

- Irony as method: visual jokes, deadpan repetition, and style mimicry destabilized the cowboy’s authority.

These works did not dismiss the West—they dissected it.

Calgary versus Vancouver: An Art Rivalry

During this period, Calgary’s art scene became increasingly aware of its position in the national landscape. Vancouver had emerged as the conceptual capital of Canadian contemporary art, buoyed by figures like Jeff Wall, Ian Wallace, and Rodney Graham. Toronto and Montreal dominated funding, media, and critical attention. Calgary—wealthy but culturally self-conscious—began to chafe at its outsider status.

In response, a number of Calgary artists doubled down on regional specificity. Rather than chasing central approval, they cultivated a local style: sharp-edged, symbolically dense, and grounded in the textures of prairie life. This was not folk art, nor was it overtly nationalist. It was rooted in place but formally ambitious—art that could hold its own in national biennials while still smelling faintly of cattle.

Institutions like The New Gallery (founded in 1975 as Clouds ‘n’ Water) became key sites for this new regionalism. Originally an artist-run centre, it gave voice to artists working outside the commercial or academic mainstream—particularly those experimenting with new media, performance, or conceptual installation. It was gritty, underfunded, and essential.

Curators, too, played a central role in shaping this moment. Jeffrey Spalding, director of the Glenbow Museum during the late 1980s and early 90s, brought a combination of curatorial daring and institutional savvy that helped push Calgary’s contemporary artists into wider view. Under his leadership, the Glenbow staged exhibitions that resisted easy categorization, placing Alberta artists alongside international peers and treating them with equal seriousness.

This regional assertion was not without friction. Some artists felt trapped by Alberta’s cultural branding—forever yoked to cowboy hats and pick-up trucks, no matter how abstract or political their work. Others embraced the contradiction, using it as a productive tension. The result was a kind of self-aware regionalism: proudly local, but never naïve.

Irony, Identity, and the Specter of the Stampede

At the heart of this moment was a persistent question: could Calgary ever escape the shadow of the Stampede?

For some artists, the answer was no—and that was precisely the point. The cowboy was too potent a symbol, too entrenched in the city’s self-image, to ignore. So they didn’t ignore it—they hollowed it out, inverted it, repurposed it. Photographers staged portraits of cowboys in drag. Installations used rodeo footage, neon signage, and country music to create disorienting environments. Performance artists adopted cowboy attire only to subvert the rituals it represented.

This work wasn’t about mocking Alberta—it was about complicating it. The cowboy became a site of tension: between masculinity and vulnerability, past and present, surface and depth. Calgary artists began to treat regional identity not as a given, but as raw material. What mattered was not whether the cowboy was “authentic,” but what he could be made to reveal.

Even traditional forms, like landscape painting and sculpture, began to carry these ambiguities. A pastoral scene might be rendered in acid tones; a bronze horse might be paired with a speaker playing stock market reports. Everywhere, the old symbols remained—but they were reframed, bent, unsettled.

This was not rebellion for its own sake. It was an attempt to make meaning in a place saturated with images, expectations, and economic pressures. In Calgary, to make art meant to reckon with spectacle—whether in the form of the Stampede, the skyline, or the constant churn of boosterist optimism. Cowboy pop was never about nostalgia. It was about what happens when myth becomes infrastructure, and artists start to notice the cracks.

The Calgary Biennial That Wasn’t: Missed Chances and Quiet Scenes

In the 1990s and early 2000s, Calgary’s art scene reached a curious threshold. It had world-class artists, a network of artist-run centres, a respected art college, and increasing national recognition. But it lacked one thing: a signature international event. Unlike Toronto’s CONTACT Festival or Vancouver’s biennial ecosystem, Calgary never consolidated its energy into a single moment of cultural convergence. A biennial was proposed more than once—seriously discussed, occasionally funded, and even tentatively sketched. But it never materialized. In its place, Calgary’s art community grew laterally rather than vertically, developing a web of interconnected but modest initiatives. This absence—of flash, of climax, of spectacle—became its own kind of identity.

Dreams of Prestige, Delayed

The most serious attempt to launch a Calgary biennial emerged in the late 1990s. Inspired in part by the rising profile of Vancouver’s international art scene and bolstered by Calgary’s own economic growth, a group of curators, artists, and civic leaders floated the idea of an event that could position the city on the global art map. Early planning meetings included proposals for public installations along the Bow River, thematic exhibitions housed in civic and private spaces, and partnerships with oil companies eager to boost their cultural credibility.

There was some momentum. Funding was discussed. Logos were designed. Consultants were hired. But the initiative stalled—caught between administrative hesitancy, political shifts at city hall, and deeper questions about what kind of event Calgary actually wanted. Was the biennial meant to attract tourists? To spotlight local artists? To bring in international stars? The lack of clarity became fatal. What was intended as a cultural crescendo turned into an extended question mark.

The hesitation was not merely bureaucratic—it reflected a larger ambivalence. Calgary was not, at heart, a festival city in the way Montreal or Edinburgh were. Its art scene thrived in long conversations, slow collaborations, and informal networks. A biennial required a kind of showmanship that felt alien to a culture more comfortable with studio visits than VIP tents.

That isn’t to say Calgary lacked large-scale ambition. The Glenbow Museum, Contemporary Calgary (in its earliest incarnations), and the Alberta College of Art and Design all hosted significant exhibitions during these years. The problem wasn’t capacity. It was cohesion. Calgary’s art world knew how to build—just not always how to gather.

The Problem of Visibility in a Resource City

Underlying these missed opportunities was a persistent anxiety about visibility. Calgary was a wealthy city with a serious art scene, but it often struggled to be seen. In national media, its cultural output was routinely overshadowed by Alberta’s political identity or dismissed as a byproduct of oil wealth. Internationally, it was rarely mentioned in the same breath as Vancouver, Montreal, or even Winnipeg.

Part of this was structural. Calgary lacked a critical mass of full-time art writers, independent curators, and collectors with international reach. Its newspapers devoted shrinking space to culture. National galleries staged fewer touring exhibitions. And despite a vibrant artist community, there was little infrastructure to help emerging artists break into broader markets.

Some artists responded by leaving. The “Calgary diaspora”—a loose term for artists trained in the city who relocated to Berlin, Montreal, or Los Angeles—became a quiet phenomenon. Others stayed, forming collectives, artist-run residencies, and micro-galleries that operated on tight budgets and sharp ideas. The city never lacked creativity. It just couldn’t always get noticed.

This invisibility had its uses. Without the glare of constant attention, artists could experiment freely. Projects could fail quietly. Scenes could evolve without external pressure to conform. Some of Calgary’s most daring work from this period emerged from basements, storefronts, or temporary installations that eschewed official channels altogether.

Three such initiatives that defined Calgary’s underground art scene in the absence of institutional spotlight:

- TRUCK Contemporary Art: one of Calgary’s longest-running artist-run centres, TRUCK supported emerging artists with a strong emphasis on social practice, installation, and media experimentation.

- The New Gallery’s alternative spaces: including its move into a Chinatown location that redefined how art interacted with neighborhood, identity, and urban space.

- Stride Gallery: known for its sharp curatorial voice and commitment to politically and aesthetically challenging work, often showcasing emerging artists before they reached national prominence.

These spaces operated without fanfare, but with deep influence. They became sites of mentorship, resistance, and quiet reinvention.

DIY Spaces and the Small-Scale Revolution

In place of a biennial, Calgary developed a patchwork of independent initiatives that blurred the lines between exhibition, residency, performance, and social gathering. This was not a compromise. It was a mode of survival—and, often, of excellence.

The early 2000s saw a rise in what could be called the small-scale revolution: projects that resisted institutionalization but were no less ambitious. Artist collectives rented warehouse lofts and converted them into hybrid studio/galleries. Pop-up shows appeared in parking garages and abandoned retail spaces. Screenings, sound installations, and performance art found audiences in places that didn’t require permits or PR firms.

This wasn’t outsider art—it was embedded. Many of the artists involved had trained at ACAD, exhibited at the Glenbow, or taught at the University of Calgary. But they chose to work at the edges, creating new forms of community and aesthetic experience.

In this ecology, failure was tolerated. Risk was welcomed. And visibility was redefined. Success wasn’t measured by reviews in Canadian Art magazine, but by who showed up, what conversations unfolded, and whether the work resonated beyond its moment.

Calgary’s art world, in other words, chose resilience over spectacle. It gave up the biennial dream in exchange for something quieter but more durable: a network of small rooms filled with big questions.

What this scene lacked in prestige, it made up for in authenticity. There was no ladder to climb, no curatorial elite to impress. Just artists, ideas, and the stubborn belief that culture could grow in a place better known for pipelines than for painting.

Public Art Controversies and the Politics of the Street

Few aspects of Calgary’s visual culture have sparked as much debate—or as much confusion—as its public art. From sculptures along bike paths to installations on highway medians, the city’s investment in art outside the gallery has been both ambitious and embattled. While civic leaders have often framed public art as a sign of modern urbanity, for many Calgarians, it has become a lightning rod for suspicion, satire, and political backlash. These tensions—between artists and audiences, between vision and reception—have shaped the city’s relationship to visual culture in fundamental ways. Calgary’s streets and plazas are not neutral sites. They are contested arenas, where questions about taste, meaning, and public money are played out in full view.

Travelling Light and the Spectacle of Disdain

No public artwork in Calgary’s recent history has caused more furor than Travelling Light—a massive, 17-meter-tall blue ring installed near the city’s airport in 2013. Designed by the Berlin-based collective inges idee, the hollow circle stood upright like a gateway, illuminated at night and framed by the highway and overpasses around it. It was sleek, abstract, and—at a cost of $471,000—politically radioactive.

Immediately derided in the press and on social media, the ring was nicknamed “The Giant Hula Hoop” or, more acidly, “the waste of space.” A local columnist called it “an insult to taxpayers.” Letters poured in to city hall. Even the mayor, Naheed Nenshi—normally a supporter of arts funding—referred to it as “a conversation piece, and that conversation is not always polite.”

But the ring wasn’t just a punchline. It became a flashpoint in Calgary’s cultural self-image. To its critics, it symbolized a city governed by bureaucratic elitism—wasting money on obscure art instead of potholes. To defenders, it was a misunderstood experiment: a European-style intervention that treated infrastructure as aesthetic opportunity. In reality, it was both more and less than its controversy. The ring didn’t fail because it was abstract—it failed because it was imposed. There was no buildup, no educational context, no local engagement. It simply appeared.

The irony, of course, is that Travelling Light did exactly what public art is sometimes meant to do: provoke conversation, reshape space, challenge norms. But it did so in a city where those goals were not broadly shared, and where visual art—particularly non-representational sculpture—remained culturally fragile.

The fallout reshaped Calgary’s public art program. Budgets were reevaluated. Processes were scrutinized. And a deep skepticism toward “outdoor modernism” took hold in public discourse.

Murals, Memory, and Municipal Mishaps

Not all public art in Calgary has been abstract or unpopular. Over the past two decades, the city has seen a significant rise in muralism—particularly in neighborhoods like Beltline, Inglewood, and East Village. These works, often produced in collaboration with community organizations or through festivals like BUMP (Beltline Urban Murals Project), have proven far more palatable to the general public. They are colorful, figurative, often narrative, and generally easy to like.

Murals celebrating Calgary’s history, flora, fauna, or civic pride now adorn dozens of buildings. Local artists like Nicole Wolf, Nasarimba, and Curtis Van Charles Sorensen have created large-scale pieces that mix street art aesthetics with regional themes—wildlife, rivers, historic architecture. These projects often include community consultation and media campaigns, avoiding the pitfalls of opaque decision-making.

But even murals are not immune to controversy. In 2021, a city-funded mural titled Giving Wings to the Dream, commemorating Black Calgarians and civil rights leaders, was vandalized within weeks of completion. The incident sparked renewed conversations about who feels included—or excluded—in Calgary’s visual narratives. Public art, even at its most legible, remains political.

Then there are the mishaps. In 2019, a kinetic sculpture installed near the Calgary Public Library malfunctioned repeatedly, leading to technical delays and public mockery. A sculpture intended for a suburban roundabout was removed before installation after a backlash against its abstract form. These cases, while minor, fed a growing perception that public art in Calgary was both expensive and aloof.

Three recurring themes emerge in Calgary’s experience with public art:

- Mismatch between intention and audience: abstract works often lack contextual support, leading to misinterpretation or hostility.

- Tension between local and international: commissions awarded to out-of-town artists can spark resentment, especially when the work feels disconnected from Calgary’s visual vocabulary.

- Underlying class anxiety: public art debates often become proxies for deeper tensions about wealth, value, and who the city is for.

Despite these issues, Calgary’s public art program continues—smaller, more cautious, but still ambitious in its reach.

Who Is the Public in Public Art?

At the core of Calgary’s public art struggles is a question rarely answered directly: who, exactly, is “the public”?

Is it commuters stuck in traffic, glancing at sculptures from behind windshields? Is it art students debating formalism in cafés? Is it suburban homeowners resentful of downtown spending? Is it tourists on the way to Banff? Calgary’s public is fractured—not just demographically, but ideologically. There is no single audience for public art in the city, and this pluralism complicates every commission.

Some artists have leaned into that ambiguity. Calgary-based collective Humainologie, for instance, has focused on socially engaged projects that emphasize storytelling, empathy, and participation. Their public installations—short films, interactive murals, audio booths—aim not to beautify space, but to humanize it. The goal isn’t consensus. It’s connection.

Others have turned public space into stages for critique. In 2014, an anonymous group projected phrases like “This is the oil you breathe” and “Nice skyline—shame about the rent” onto downtown buildings. These ephemeral interventions, uncommissioned and unfiltered, offered a kind of shadow biennial—a reminder that public art doesn’t need permission to be effective.

Calgary’s streets are more contested than curated. And perhaps that’s the point. In a city where political identity remains volatile, where wealth and austerity collide daily, public art can never be neutral. It will always be read—fairly or unfairly—as a statement about who controls space, who deserves beauty, and who decides what counts as culture.

Calgary’s public art is uneven, yes. Sometimes misguided. Sometimes brilliant. But always revealing.

New Media, American Indian Resurgence, and the 21st Century Turn

At the threshold of the 21st century, Calgary’s art scene began to shift again—not through a singular event, but through a slow accumulation of voices, media, and motives that pushed the city into a new phase of cultural reckoning. Artists were no longer content to inherit the formal legacies of modernism or the ironic strategies of postmodernism. Instead, they began to fuse disciplines, disrupt categories, and speak directly to histories and presences that had long been suppressed in Calgary’s civic image. At the center of this shift were two parallel developments: the emergence of new media practices that redefined what art could be, and the resurgence of American Indian artists reclaiming space, history, and narrative in the urban landscape of Treaty 7 territory.

Digital Territories and Interdisciplinary Practice

The rise of digital tools in the late 1990s and early 2000s opened new terrain for Calgary artists. No longer tethered to canvas or gallery, a growing number of creators began working in video, sound, interactive installation, and virtual environments. This wasn’t mere experimentation—it was a redefinition of practice, rooted in a broader shift toward interdisciplinarity that had been nurtured by ACAD, the University of Calgary, and the Banff Centre’s Media and Visual Arts programs.

Artists like Stacey Cann and Kai Cabunoc-Boettcher began to explore themes of surveillance, identity, and memory through mixed media and interactive design. Sound art—long marginal in gallery contexts—found new prominence in Calgary’s experimental venues, aided by artist-run spaces that embraced immersive installation. These works didn’t always fit comfortably within traditional exhibition models. They required headphones, screens, time. But they forced viewers to linger, to engage art not as object but as experience.

This mode of work aligned with a global shift, but it also reflected Calgary’s own dissonances. The city’s rapid urban growth, climate anxieties, and technological infrastructure became fertile ground for artistic response. Artists used drones, GPS data, and mapping software to document disappearing green space, changing water flows, and shifting urban borders. The Bow and Elbow rivers—once framed in landscape paintings—became nodes in digital works tracing ecological and historical rupture.

The proliferation of interdisciplinary projects also blurred lines between artist and researcher, between studio and lab. Collaborations between artists and scientists, between programmers and poets, became increasingly common. This was not a rejection of traditional media. It was an expansion—a willingness to let form follow question.

Three characteristics defined this new media turn in Calgary:

- Site-specificity: works tied closely to geography, infrastructure, or municipal histories.

- Temporal disruption: installations that unfolded over time, resisting quick consumption.

- Hybrid authorship: projects developed through collaborative research rather than individual vision.

These qualities marked a departure from the singular, stable artworks of earlier decades. In their place, Calgary artists began building systems, rituals, and environments.

Reimagining Treaty 7 in Contemporary Work

Perhaps the most vital shift in Calgary’s contemporary art has come from American Indian artists reclaiming voice, visibility, and aesthetic authority within the city’s cultural sphere. Long relegated to ethnographic displays or historical sidebars, Blackfoot, Stoney Nakoda, and Tsuut’ina artists have, over the past two decades, asserted a contemporary presence that challenges settler narratives and reframes the landscape as layered, living territory.

This resurgence has not been decorative. It has been political, conceptual, and grounded in community. The work of artists like Terrance Houle, Faye HeavyShield, and Adrian Stimson has redrawn Calgary’s artistic map—not by mimicking Western forms, but by bending them toward storytelling, ceremony, and resistance.

Terrance Houle, a member of the Blood Tribe (Kainai Nation), has employed video, performance, and photography to challenge and recontextualize Western tropes of Indianness. In his piece Urban Indian, Houle walks through downtown Calgary in full powwow regalia, juxtaposing traditional dress with modern cityscapes. The work is simple in structure but profound in implication: who belongs in the urban landscape, and how is that belonging made visible?

Faye HeavyShield, whose minimalist sculptural installations have been widely exhibited, takes a quieter but equally powerful approach. Her works often use repetition—beads, stones, paper forms—to evoke memory, loss, and continuity. In one piece, hundreds of red ochre dots spiral outward on a gallery floor, referencing both blood and beadwork, earth and body. Her materials speak in whispers, but they linger.

Adrian Stimson—Blackfoot artist, former Glenbow artist-in-residence, and 2018 Governor General’s Award recipient—has used performance and installation to confront both colonial history and contemporary resilience. His alter-ego “Buffalo Boy” parodies the hyper-masculine imagery of the cowboy and the Indian, blending drag, ritual, and critique in a persona both absurd and sacred. Stimson’s work moves fluidly between grief and satire, particularly in projects addressing residential schools and military commemoration.

These artists do not merely “represent” their nations. They restructure Calgary’s visual field, insisting that Treaty 7 is not a historical footnote but a present-tense reality. Their work is not supplementary. It is central.

Artists of Migration and Displacement

As Calgary grew in population and complexity, its art scene began to reflect a wider spectrum of global and diasporic experience. Immigrant and refugee artists—many of whom arrived through federal resettlement programs or intra-Canadian migration—brought with them aesthetics, languages, and historical frameworks that reshaped Calgary’s visual culture from the inside.

This wasn’t multiculturalism-as-branding. It was artistic reckoning.

Artists like Suzan Dube, a Zimbabwe-born interdisciplinary artist working with fabric and performance, have addressed the emotional texture of displacement—not as metaphor, but as daily condition. Her work often references familial memory, hybrid identity, and the gap between institutional inclusion and personal alienation.

The artist Vivek Shraya—musician, writer, and visual creator—has used photography and installation to explore the intersections of gender, race, and authorship. Her 2016 project Trisha recreated photographs of her mother, echoing and complicating visual legacies passed through migration and motherhood. Though Shraya’s national profile has grown, she has remained closely connected to Calgary’s art institutions, mentoring younger artists and exhibiting locally with intention.

Public institutions, slowly and unevenly, began to respond. The Esker Foundation, founded in 2012 by philanthropist Jim Hill, emerged as one of Calgary’s most forward-looking spaces—hosting exhibitions that prioritized global dialogue, emerging voices, and critical context. Its free admission policy, rigorous programming, and commitment to education helped bridge gaps between artist and audience, local and international.

Yet the work of inclusion remained complex. Calgary’s art infrastructure—shaped by decades of Eurocentric traditions—struggled at times to adapt to artists working in languages, methods, or genealogies unfamiliar to gatekeepers. Progress was real, but uneven. And in that unevenness, some of the most compelling work was made.

Calgary’s art in the 21st century is no longer tethered to any one movement, form, or identity. It is plural, contradictory, and in constant motion. The city’s aesthetic terrain is shaped as much by memory as by novelty, as much by survival as by success.

This is not a scene defined by triumph. It is defined by ongoing negotiation—between past and future, between media and message, between place and movement.

Institutions, Collectors, and the Shaping of Legacy

For any city, legacy is not merely what gets remembered—it is who does the remembering, and with what means. In Calgary, the question of artistic legacy has been filtered through a complex network of institutions, collectors, and archival practices that both preserve and distort the city’s cultural memory. Museums strive for coherence, collectors pursue influence, and foundations try to balance civic duty with personal taste. This ecology of preservation has shaped not only which artworks survive but also how Calgary’s visual history is narrated—and by whom. Legacy here is less a monument than a ledger: accumulated, disputed, revised.

The Glenbow’s Evolution and Reorientation

No institution has done more to define Calgary’s public understanding of art history than the Glenbow Museum. Founded in 1966 by oilman and philanthropist Eric Harvie, the Glenbow began as a hybrid institution: part archive, part museum, part gallery. Harvie’s initial collection spanned fine art, Western memorabilia, and ethnographic material—reflecting both his private interests and his belief that Alberta’s frontier deserved a museum as ambitious as the Royal Ontario Museum or the British Museum.

The Glenbow’s early decades were marked by eclecticism. Its art collection included Group of Seven paintings, European prints, and American Indian beadwork—sometimes displayed together, without apology or context. This pluralism was both a strength and a liability. Critics accused the museum of lacking curatorial focus, of confusing spectacle with scholarship. But for Calgarians, the Glenbow was often the first place they encountered serious art: its centrality in the city’s civic imagination was unmatched.

By the 1990s, however, the Glenbow faced pressures to professionalize. Under directors like Jeffrey Spalding and Mike Robinson, the museum attempted to sharpen its curatorial vision, expand its contemporary holdings, and develop a more coherent exhibition strategy. Shows became more thematic, acquisitions more targeted. Yet the institution struggled to balance its dual mandate as both encyclopedic museum and contemporary art venue. Budget cuts, leadership turnover, and mounting pressure to diversify its programming created persistent turbulence.

In recent years, a major reorientation has begun. A transformative $25 million donation in 2021 allowed the Glenbow to eliminate admission fees and undertake a comprehensive renovation. Its mission shifted: from encyclopedic repository to inclusive civic platform. New galleries emphasized contemporary art, particularly from underrepresented groups. The museum’s approach to American Indian material—long housed in a mixture of reverence and exoticism—was reconsidered, with renewed attention to community collaboration and curatorial agency.

Yet tensions remain. Legacy institutions like the Glenbow must reconcile competing expectations: to honor history, to engage the present, and to anticipate future audiences who may question the assumptions embedded in every exhibition.

Three long-standing dilemmas faced by the Glenbow as it redefines its role:

- Balancing breadth with depth: its holdings are vast, but coherence often comes at the cost of exclusion.

- Navigating donor legacies: foundational collections carry historical biases that complicate present-day curating.

- Integrating contemporary voices: the museum must continually re-earn its relevance amid shifting cultural values.

The Glenbow is no longer the only institutional player in town, but its legacy—shaped by oil money, civic ambition, and curatorial reinvention—remains a dominant force.

Corporate Patronage and Its Discontents

While museums provide public memory, collectors shape private taste—and in Calgary, that taste has often been corporate. The city’s economic foundation in oil and finance has produced a network of executives and companies eager to acquire art, whether for boardrooms or brand-building. For decades, firms like TransCanada, Encana, and Nexen amassed large collections of Canadian contemporary art, much of it abstract, large-scale, and visually striking.

This patronage system had upsides. It provided consistent income for working artists, raised the market value of Calgary-based painters and sculptors, and occasionally supported ambitious commissions. In the absence of robust government arts funding, the corporate sector filled the gap.

But the drawbacks were substantial. Corporate collections often favored decor over discourse—art that signaled prestige without provocation. Radical or difficult work was rarely acquired. Artists whose practice leaned toward conceptualism, social critique, or American Indian history often found themselves outside the collecting mainstream. And when economic downturns hit—as they inevitably did in Calgary’s boom-and-bust cycle—collections were mothballed, sold off, or quietly dissolved.

This volatility extended to sponsorships. Festivals, galleries, and artist-run centres often relied on oil and gas companies for event funding, placing them in uneasy alliances. Some artists refused such support. Others accepted it as pragmatic necessity. The moral calculus was rarely simple.

By the 2010s, a generational shift was underway. A younger cohort of collectors—many of whom were artists themselves or professionally adjacent to the art world—began focusing on local, experimental, and politically engaged work. Collecting became less about investment and more about alignment: with values, identities, and community.

But the institutional frameworks for legacy collection—permanent endowments, artist estates, public archives—remained underdeveloped. Many significant Calgary artists from the 1980s and 90s still lack a stable archival home. Their papers are in basements, their works scattered across private hands, their reputations unevenly preserved.

Legacy, in this context, is precarious.

Archives, Foundations, and the Struggle Over Memory

In recent years, Calgary’s art scene has turned increasingly toward the question of preservation. Who documents what? Which narratives are codified, and which are forgotten? Artist-run centres like TRUCK, The New Gallery, and Stride Gallery have begun organizing their own archives—digitizing exhibition materials, commissioning oral histories, and reclaiming ephemera once seen as peripheral.

The EMMEDIA Gallery & Production Society, founded in 1979, has taken a leading role in preserving Calgary’s video and media art legacy. Long dismissed as uncollectible or too niche, video works are now being restored, catalogued, and re-exhibited—revealing a rich, subversive strand of Calgary’s cultural DNA.