South American art is a powerful testament to the continent’s cultural, spiritual, and historical richness. Spanning thousands of years, it encompasses everything from ancient ceremonial carvings to bold contemporary works that challenge social conventions. Each era reflects the complex interplay of tradition, innovation, and resilience. These creations, forged in the crucible of diverse landscapes and cultures, offer a window into the lives and beliefs of their creators.

The journey of South American art begins with the earliest civilizations, whose monumental achievements laid the groundwork for the continent’s artistic legacy. From the intricate carvings of the Chavín to the mysterious Nazca Lines, early societies transformed their environments into canvases of spiritual and social significance. Later, the rise of powerful empires such as the Tiwanaku and Inca brought a new level of sophistication, blending art with architecture to create enduring masterpieces like Machu Picchu.

The arrival of European colonizers in the 16th century marked a profound shift, introducing new techniques and religious themes while merging them with existing traditions. The art of the colonial period reflected a blend of faith, resilience, and adaptation, paving the way for the independence movements of the 19th century. During this time, Romanticism and Realism flourished, showcasing the landscapes and struggles of the emerging nations.

In the 20th century, South American artists embraced modernism, exploring new forms and ideas while remaining deeply rooted in their heritage. Movements like Indigenismo and Constructivism celebrated native cultures and sought to redefine national identities. Today, contemporary artists continue this legacy, using their work to address global and local issues while celebrating the vibrant traditions of their ancestors.

This article explores the multifaceted history of South American art, tracing its evolution from ancient civilizations to the present day. Each chapter delves into a pivotal period, examining the techniques, themes, and legacies of the artists and cultures that shaped this rich tradition.

Chapter 1: Art of the Early Civilizations

Artistic Achievements of Early Societies

The earliest societies of South America, such as the Chavín, Nazca, and Moche, produced extraordinary works of art that reflected their spiritual beliefs, social structures, and interactions with their environments. These cultures thrived long before the rise of the Inca Empire, yet their artistic contributions laid a strong foundation for the continent’s creative legacy. From monumental stone carvings to vibrant pottery, these civilizations developed techniques and themes that would resonate through history.

The Chavín civilization, which thrived from approximately 900 BC to 200 BC in modern-day Peru, was centered at the ceremonial site of Chavín de Huantar in the Andean highlands. This UNESCO World Heritage Site was a hub of religious and political activity, drawing pilgrims from across the region. The most famous artifact from Chavín de Huantar is the Lanzón, a 15-foot monolith carved with intricate depictions of a supernatural figure. This figure, combining human and animal traits such as jaguars and snakes, symbolized divine power and the interconnectedness of the spiritual and natural worlds. The Chavín also excelled in creating sophisticated textiles adorned with intricate geometric patterns and symbols reflecting their religious beliefs.

The Nazca culture, which flourished between 200 BC and AD 600 along Peru’s southern coast, is best known for the Nazca Lines. These massive geoglyphs, etched into the desert floor, include depictions of animals like the hummingbird, monkey, and spider, as well as geometric patterns. Scholars have debated the purpose of these lines, with theories ranging from astronomical markers to pathways for ceremonial processions. The Nazca also produced fine pottery, decorated with vivid colors and designs that often mirrored the motifs found in their geoglyphs. Their textiles were equally remarkable, incorporating complex patterns and vibrant hues that reflected their environment and spiritual beliefs.

The Moche civilization, active from AD 100 to AD 800 along the northern coast of Peru, is renowned for its realism and storytelling in art. Moche ceramics are particularly notable for their portrait vessels, which feature highly realistic depictions of human faces, capturing a range of emotions and expressions. These vessels offer invaluable insights into the personalities and lives of the Moche people, from warriors and rulers to common citizens. The Moche were also masterful metalworkers, creating elaborate objects from gold, silver, and copper. Their ceremonial items, such as the iconic Tumi knives, were both functional and symbolic, reflecting their belief in the afterlife and the importance of ritual.

These early civilizations demonstrated a deep understanding of materials and techniques, blending artistry with functionality. Whether through monumental architecture like the Chavín de Huantar temple, the enigmatic designs of the Nazca Lines, or the lifelike Moche ceramics, their art continues to captivate and inspire. These achievements reveal not only their technical skill but also their ability to convey profound spiritual and cultural messages through art.

Techniques and Materials

The early South American civilizations displayed remarkable ingenuity in their use of materials, crafting art that was both innovative and enduring. Their techniques reflected their resourcefulness, often incorporating materials readily available in their natural environments. Stone, clay, metals, and textiles became the primary media for their artistic expression, each used with exceptional skill.

The Chavín people excelled in stone carving, creating intricate reliefs and monoliths that adorned their temples and ceremonial centers. Granite and tuff were commonly used, with tools made from harder stones allowing artisans to achieve detailed designs. Gold and silver also played a significant role in Chavín art, particularly in the creation of jewelry and ceremonial objects. The Chavín’s ability to work with such materials demonstrates their advanced knowledge of metallurgy and their capacity to create objects imbued with spiritual significance.

The Nazca civilization utilized local resources to produce vibrant textiles and ceramics. Alpaca wool and cotton were woven into intricate fabrics, often dyed with natural pigments derived from plants and minerals. These textiles frequently depicted stylized animals and abstract patterns, echoing the designs of the Nazca Lines. Their pottery was equally impressive, painted with vivid colors that remained durable over centuries. The Nazca also developed techniques for large-scale earthworks, such as their iconic geoglyphs, which involved removing surface stones to expose lighter soil underneath.

The Moche were unparalleled in their ability to work with clay and metal. They utilized molds to create detailed pottery, enabling the mass production of vessels with complex designs. Their metallurgical techniques included lost-wax casting, which allowed for the creation of intricate gold and silver objects. This method involved sculpting a model in wax, encasing it in clay, and then heating it to melt the wax, leaving a mold for pouring molten metal. The Moche also used copper alloys to create ceremonial knives, jewelry, and headdresses, showcasing their expertise in metalworking.

Each civilization’s use of materials was deeply symbolic, reflecting their beliefs and societal structures. The Chavín’s depictions of animals and deities in stone emphasized their spiritual connection to nature, while the Nazca’s textiles and geoglyphs celebrated the harmony between humanity and the cosmos. The Moche’s lifelike ceramics and elaborate metalwork captured the vibrancy of their daily lives and their reverence for the divine. Together, their mastery of materials and techniques laid the groundwork for the artistic achievements of later civilizations.

Symbolic Themes: Religion, Nature, and Community Life

Art in these early South American societies was profoundly symbolic, serving as a medium to express their spiritual beliefs, their relationship with nature, and their social order. Each civilization infused its art with meaning, creating works that were not only visually striking but also deeply significant.

Religion was a central theme in the art of the Chavín civilization. The Lanzón at Chavín de Huantar, for instance, depicted a deity believed to mediate between the human and divine realms. Its combination of human, jaguar, and serpent features symbolized the blending of natural and supernatural forces. The temple itself was designed to evoke spiritual awe, with its intricate carvings and ceremonial pathways guiding visitors through sacred spaces. This emphasis on the spiritual role of art highlights how deeply religion permeated Chavín society.

The Nazca culture, while also spiritual, emphasized their connection to the environment in their art. The Nazca Lines, particularly figures like the monkey and hummingbird, are thought to have held ritualistic significance, possibly related to agricultural fertility or water sources. These designs may have been created as offerings to deities, aligning earthly activities with celestial patterns. The Nazca’s vibrant textiles and ceramics often featured similar motifs, blending artistic expression with reverence for nature’s cycles.

The Moche civilization used art to reflect both their spiritual and societal structures. Their ceramics depicted elaborate scenes of rituals, battles, and agricultural practices, illustrating the centrality of these activities in their lives. The Moche’s portrayal of individuals in their portrait vessels emphasized the importance of community and hierarchy. These works also often served as funerary offerings, symbolizing the connection between the living and the afterlife.

Nature was an ever-present theme in the art of all three civilizations. The jaguar, serpent, and condor—common motifs in Chavín art—symbolized power, transformation, and freedom. The Nazca’s depictions of animals and plants celebrated the interconnectedness of life and the cosmos. The Moche, in their realistic portrayals of marine life and agricultural scenes, underscored their reliance on the environment for sustenance and prosperity. This focus on nature and spirituality created a profound sense of continuity between humanity, the divine, and the natural world.

Key Examples: Nazca Lines, Moche Pottery, and Chavín Stone Carvings

Several iconic works exemplify the artistic brilliance of these early South American civilizations. These creations continue to captivate scholars and visitors alike, offering a glimpse into the innovative spirit and deep cultural roots of their creators.

The Chavín’s monumental stonework at Chavín de Huantar, particularly the Lanzón, remains one of the most significant examples of Andean art. This towering granite monolith, housed in the temple’s inner sanctum, was likely the focal point of religious ceremonies. Its intricate carvings, featuring serpents, jaguars, and abstract patterns, reflect the Chavín’s belief in the unity of spiritual and natural realms. The temple itself, with its labyrinthine layout and sophisticated drainage system, demonstrates the Chavín’s mastery of engineering and design.

The Nazca Lines, stretching across the Pampa Colorada desert, are another unparalleled achievement. These geoglyphs, some spanning hundreds of feet, include figures like the condor, which measures over 400 feet in length. The precision required to create these designs, visible only from the air, speaks to the Nazca’s advanced understanding of geometry and planning. Their pottery and textiles, adorned with similar motifs, reinforce the importance of these themes in Nazca culture.

The Moche civilization’s portrait vessels are celebrated for their lifelike detail and emotional depth. These ceramic works capture the individuality of their subjects, depicting warriors, priests, and everyday people. The discovery of the Tomb of the Lord of Sipán near Chiclayo revealed an extraordinary collection of Moche art, including gold jewelry, ceremonial headdresses, and intricate pottery. This find underscores the Moche’s artistic and cultural sophistication.

These works, whether monumental or intimate, embody the creativity and vision of South America’s early civilizations. From the Chavín’s spiritual carvings to the Nazca’s enigmatic geoglyphs and the Moche’s realistic ceramics, their art remains a timeless testament to their ingenuity and connection to their world.

Chapter 2: Art of the Empire Builders

Focus on the Art of Powerful Societies

The Tiwanaku and Inca civilizations are among the most influential in South American history, renowned for their artistic and architectural accomplishments. These societies combined art with functionality, creating works that symbolized their religious beliefs, social hierarchies, and connection to the natural world. Their ability to harmonize engineering with aesthetics remains one of their most remarkable achievements, influencing subsequent cultures across the continent.

The Tiwanaku civilization, which thrived from around AD 400 to AD 1000, was centered at the site of Tiwanaku in modern-day Bolivia. This city served as a political and spiritual hub for an empire that extended across the Andean highlands. The Gateway of the Sun, one of Tiwanaku’s most iconic structures, exemplifies their mastery of stonework. This monolithic arch features intricate carvings of Viracocha, a deity associated with creation, surrounded by winged figures. The Gateway likely served as both a ceremonial focal point and an astronomical marker, aligning with the solstices to reflect the Tiwanaku’s deep understanding of the cosmos.

The Inca Empire, which emerged in the 13th century and reached its height in the 15th and early 16th centuries, was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. Their capital, Cusco, was the political and spiritual center of their vast domain. The Inca’s artistic achievements are most famously represented in their architecture, particularly Machu Picchu, a royal estate built around AD 1450. This site demonstrates the Inca’s advanced engineering skills, with its terraced agriculture, precisely cut granite stones, and sophisticated drainage systems. Structures like the Temple of the Sun and the Intihuatana Stone reveal the Inca’s focus on solar worship and astronomical observation.

Both the Tiwanaku and Inca civilizations used art and architecture to assert their dominance and convey their spiritual beliefs. For the Tiwanaku, monumental stonework symbolized their connection to the divine and their control over the natural world. The Inca, similarly, integrated their art into their empire-building efforts, using architecture to create awe-inspiring spaces that reinforced their authority. These works were not merely decorative but deeply functional, serving as tools of governance, religion, and community life.

The legacies of these powerful societies endure through their artistic and architectural innovations. Sites like Tiwanaku and Machu Picchu continue to inspire awe and attract scholars from around the world. Their art reflects not only their technical ingenuity but also their ability to communicate complex ideas about power, spirituality, and harmony with nature.

Use of Gold, Silver, and Stone

Gold, silver, and stone were central to the artistic traditions of the Tiwanaku and Inca civilizations, serving as both materials for artistic expression and symbols of spiritual significance. These materials were often associated with the divine, reflecting their societies’ cosmological beliefs and reverence for nature.

The Tiwanaku civilization excelled in the use of stone, crafting monumental structures that have withstood centuries. The Pumapunku, a large ceremonial platform, features intricately carved stone blocks weighing several tons each. These stones were precisely cut to interlock without mortar, creating structures that were both durable and aesthetically impressive. Gold and silver were also significant in Tiwanaku art, symbolizing the sun and moon. Artisans created intricate jewelry, such as pectorals and earrings, which were often worn during ceremonies to emphasize their connection to celestial powers.

For the Inca, gold and silver held even greater importance, reflecting their worship of Inti, the sun god, and Mama Killa, the moon goddess. The Coricancha, or Temple of the Sun, in Cusco, was adorned with sheets of gold and housed golden statues and ceremonial objects. These objects were often melted down by the Spanish, but historical accounts describe their extraordinary craftsmanship. The Inca also excelled in stonework, as seen in structures like Sacsayhuamán, a fortress overlooking Cusco. The massive stones used in its construction were cut and fitted with such precision that they remain a marvel of engineering.

The use of these materials was deeply symbolic. Gold, associated with the sun, represented life, energy, and the divine, while silver, linked to the moon, symbolized balance and reflection. Stone, as a material of permanence, conveyed strength and stability, reinforcing the enduring power of these civilizations. These materials were not only valued for their physical properties but also imbued with spiritual meaning, elevating their artistic creations to sacred status.

The artistic achievements of the Tiwanaku and Inca in working with gold, silver, and stone reflect their mastery of materials and their ability to infuse art with profound cultural and spiritual significance. These works continue to captivate, offering insights into their cosmology and their vision of the world.

Architecture as Art

For both the Tiwanaku and Inca civilizations, architecture was a primary medium for artistic expression. Their structures were not merely functional but designed to reflect their cosmological beliefs, social hierarchies, and engineering prowess. The scale and precision of their architectural works remain unparalleled, showcasing their ability to harmonize human ingenuity with natural landscapes.

The city of Tiwanaku was meticulously planned, with temples, plazas, and residential areas aligned to celestial patterns. The Kalasasaya Temple, a large open courtyard surrounded by megalithic walls, served as a ceremonial space for observing astronomical events. The temple’s alignment with the solstices highlights the Tiwanaku’s understanding of celestial movements and their integration of art, science, and spirituality. The Ponce Monolith, a stone statue within the temple complex, features intricate carvings of symbolic motifs, further emphasizing the spiritual significance of Tiwanaku’s architecture.

The Inca, building on the traditions of earlier Andean cultures, created architectural masterpieces that blended functionality with aesthetic beauty. Machu Picchu, perched high in the Andes, exemplifies this approach. Its terraced fields, temples, and residential areas were carefully designed to integrate with the mountainous landscape. The Intihuatana Stone, a carved ritual stone within Machu Picchu, was likely used for solar observations, underscoring the Inca’s focus on astronomical alignment. Other sites, such as Ollantaytambo and Pisac, feature similar combinations of agricultural, residential, and ceremonial structures, each reflecting the Inca’s holistic approach to architecture.

Both civilizations utilized their architectural achievements to project power and inspire reverence. The massive scale and intricate details of their structures conveyed their ability to command resources and labor, reinforcing their authority over their territories. These buildings also served as physical manifestations of their spiritual beliefs, connecting the earthly and divine realms through their design and orientation.

The architectural legacies of the Tiwanaku and Inca endure as some of the most iconic symbols of South America’s cultural heritage. Sites like Tiwanaku and Machu Picchu continue to draw visitors and researchers, offering a glimpse into the ingenuity and vision of these ancient civilizations. Their architecture remains a testament to the harmony they achieved between artistry, engineering, and spirituality.

Lasting Influence of These Empires

The artistic and architectural innovations of the Tiwanaku and Inca civilizations have left a profound impact on South American culture and heritage. These societies set standards for craftsmanship, engineering, and symbolic expression that continue to resonate in contemporary art and architecture.

The Tiwanaku civilization’s emphasis on monumental stonework and cosmic symbolism influenced later Andean cultures, including the Inca. The Gateway of the Sun, with its intricate carvings and alignment with astronomical events, remains a symbol of Tiwanaku’s artistic and spiritual sophistication. The site of Tiwanaku itself, declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, continues to be a place of pilgrimage and study, offering insights into the beliefs and achievements of this ancient civilization.

The Inca’s influence extended far beyond their empire’s fall. Their use of terrace farming, precise stone masonry, and textile patterns persisted in local traditions, blending with colonial influences to create unique forms of artistic expression. Sites like Machu Picchu, Sacsayhuamán, and the Sacred Valley are not only preserved as UNESCO World Heritage Sites but also serve as symbols of Peruvian identity and pride. The Inca’s emphasis on harmony with nature has inspired modern architects and environmentalists, demonstrating the enduring relevance of their vision.

The artistic traditions of these empires also inspire contemporary South American artists, who draw on the themes and techniques of their ancestors to create works that reflect modern issues while honoring their heritage. From public murals to traditional textiles, the legacy of Tiwanaku and Inca art continues to shape the cultural landscape of the region.

The artistic legacies of the Tiwanaku and Inca civilizations are more than historical artifacts; they are living traditions that connect the past to the present. Their achievements in art and architecture continue to inspire awe and admiration, standing as testaments to the creativity and vision of South America’s ancient empires.

Chapter 3: The Early Colonial Period

Introduction of European Artistic Techniques and Religious Themes

The early colonial period in South America marked a profound transformation in artistic expression. With the arrival of the Spanish in the early 16th century, indigenous art forms encountered European styles, materials, and techniques. This period saw the introduction of Christian iconography, oil painting, and new architectural styles that merged with existing traditions to create a unique artistic synthesis. While colonial art often reflected the power and influence of the Church and European colonizers, it also preserved elements of pre-Columbian traditions, resulting in a dynamic and multifaceted artistic legacy.

One of the most significant changes during this time was the shift in artistic focus toward Christian themes. Churches, monasteries, and religious institutions became the primary patrons of art, commissioning works that glorified biblical stories and saints. Paintings and sculptures often depicted scenes from the life of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and various saints, intended to inspire devotion among the converted populations. European artists brought techniques such as oil painting and perspective, which significantly influenced local artisans.

While European influence dominated, local artists adapted these techniques to include elements of their own cultures. In regions like Peru and Bolivia, indigenous craftspeople incorporated native motifs and styles into Christian art. For example, depictions of the Virgin Mary often took on the form of a mountain, symbolizing Pachamama, the Andean earth goddess. This fusion of Christian and Andean traditions created a distinctive style that became a hallmark of the colonial period.

Art during this period was not limited to painting and sculpture; it also encompassed architecture. Spanish colonists introduced Renaissance and Baroque styles, which were integrated into the design of churches and civic buildings. The use of intricate stone carvings, gilded altars, and elaborate facades reflected the wealth and power of the colonial elite. However, these structures often relied on the labor and craftsmanship of local artisans, whose contributions imbued them with a uniquely South American character.

Fusion of Local Traditions with European Styles

The colonial period gave rise to a new artistic vocabulary that blended European and native traditions. This fusion, often referred to as syncretism, was particularly evident in religious art, where local materials, symbols, and techniques were combined with Christian iconography. This blending not only enriched the artistic landscape but also allowed local cultures to retain aspects of their identity under colonial rule.

One of the most striking examples of this fusion is the Cusco School of Art, which emerged in the 17th century in present-day Peru. This movement, centered in the former Inca capital of Cusco, produced works that combined European painting techniques with Andean stylistic elements. Artists of the Cusco School, many of whom were indigenous or mestizo, created richly detailed paintings that depicted Christian themes but included native flora, fauna, and textiles. For instance, angels were often dressed in traditional Andean garments, while the Virgin Mary was adorned with patterns resembling Inca textiles.

Metalwork and jewelry also showcased the blending of traditions. Spanish colonizers introduced European styles of goldsmithing, but local artisans incorporated pre-Columbian motifs and techniques. Religious items such as chalices, crucifixes, and monstrances were crafted using traditional Andean designs, resulting in objects that were both functional and deeply symbolic. These works often included symbols like the sun and moon, which held spiritual significance in both Christian and Andean beliefs.

Textiles were another medium where this fusion was evident. Spanish demand for fine fabrics led to the adaptation of pre-Columbian weaving techniques to produce items for liturgical use, such as altar cloths and priestly vestments. The patterns and designs on these textiles often included native symbols, subtly preserving cultural heritage within a Christian framework. This blending of traditions ensured the survival of Andean weaving practices while contributing to the development of a uniquely South American artistic style.

Syncretism was not limited to visual art; it also extended to music and performance. The introduction of European musical instruments such as the guitar and harp led to the creation of new forms of sacred music that incorporated local rhythms and melodies. Festivals and religious ceremonies became vibrant displays of cultural fusion, with indigenous dances and costumes integrated into Christian celebrations. These traditions continue to thrive in many parts of South America today, demonstrating the enduring legacy of this period of artistic blending.

Notable Artists and Works from the Colonial Period

The colonial period saw the emergence of remarkable artists and masterpieces that defined the era’s artistic achievements. While many artists remained anonymous, their works have become enduring symbols of South America’s cultural heritage. From painters to sculptors and architects, the contributions of these individuals helped shape the region’s visual identity during a time of profound change.

One of the most famous artists of the colonial period was Diego Quispe Tito, a prominent figure in the Cusco School of Art. Active in the late 17th century, Quispe Tito is best known for his large-scale religious paintings, which often depicted biblical scenes set against Andean landscapes. His work, characterized by its vivid colors and intricate details, exemplifies the fusion of European techniques with local influences. Paintings such as The Last Judgment and The Virgin of the Rosary highlight his ability to convey spiritual themes while incorporating native elements.

Sculpture also flourished during this period, particularly in religious contexts. Artists created lifelike wooden statues of saints and biblical figures, often painted and adorned with real fabrics to enhance their realism. One notable example is the Christ of the Earthquakes, a wooden crucifix housed in the Cusco Cathedral. Believed to have miraculous powers, this statue is a focal point of religious devotion and a testament to the skill of colonial sculptors.

Architecture reached new heights with the construction of grand cathedrals and churches across South America. The Cathedral of Cusco, built between 1560 and 1654, is a masterpiece of colonial architecture. Its facade combines Renaissance and Baroque elements, while its interior features gilded altars, intricate carvings, and religious paintings. Similarly, the San Francisco Church in Quito, Ecuador, showcases a blend of European and local influences, with its ornate facade and richly decorated interior.

In addition to these monumental works, countless anonymous artisans contributed to the artistic landscape of the colonial period. Their work in textiles, ceramics, and jewelry reflects the everyday artistry of the era, often overshadowed by larger-scale projects but no less significant in its cultural impact. These artisans played a crucial role in preserving and adapting South American traditions, ensuring that their voices remained part of the continent’s artistic narrative.

Artistic Expressions of Resistance and Adaptation

While much of the art from the colonial period reflected European influences, it also served as a medium for resistance and adaptation. Local artists and communities used their creativity to subtly challenge colonial authority and preserve their cultural identity. This resistance is evident in the ways traditional symbols and techniques were integrated into Christian art, often embedding messages of resilience and survival.

One of the most compelling examples of artistic resistance is the use of native motifs in religious paintings. Artists of the Cusco School, for instance, incorporated Andean symbols such as the sun, a sacred element in pre-Columbian cosmology, into depictions of Christ and the Virgin Mary. These subtle inclusions allowed indigenous communities to see their beliefs reflected in Christian imagery, preserving a sense of spiritual continuity amid cultural upheaval.

Architecture also became a site of adaptation and resistance. Churches and cathedrals, while built in European styles, often featured elements inspired by local traditions. The Church of San Pedro Apóstol in Andahuaylillas, Peru, sometimes called the “Sistine Chapel of the Andes,” is a prime example. Its richly painted ceilings and walls incorporate both Christian and Andean themes, blending sacred traditions in a way that resonates with local worshippers. This integration reflects the resilience of Andean culture in the face of colonization.

Crafts such as textiles and ceramics further illustrate the adaptability of South American artisans. While producing items for colonial markets, these artisans continued to use traditional methods and designs, subtly preserving their cultural heritage. For example, woven patterns often included references to ancestral stories and cosmological beliefs, maintaining a connection to the past even as new influences reshaped their world.

Through these acts of artistic adaptation, South America’s indigenous communities found ways to assert their identity and resist cultural erasure. By blending European and native traditions, they created a distinctive artistic legacy that continues to resonate today. This period of creativity and resilience demonstrates the power of art to bridge divides and sustain cultural memory.

Chapter 4: Romanticism and Realism in Post-Colonial South America

Exploration of Artistic Styles Following Independence

The 19th century was a time of profound transformation for South America as nations broke free from colonial rule and sought to establish their own identities. This period of political upheaval and nation-building deeply influenced the continent’s art, leading to the emergence of Romanticism and Realism as dominant styles. These movements reflected the aspirations and struggles of newly independent nations, offering both idealized and pragmatic portrayals of life.

Romanticism, which gained prominence in the early 19th century, emphasized emotion, imagination, and national pride. South American artists drew inspiration from their landscapes, history, and folklore, creating works that celebrated the unique character of their homelands. Historical events, particularly those related to independence struggles, were a recurring theme in Romantic art. Paintings often depicted heroic figures, battles, and scenes of patriotic triumph, fostering a sense of unity and purpose among the newly liberated populations.

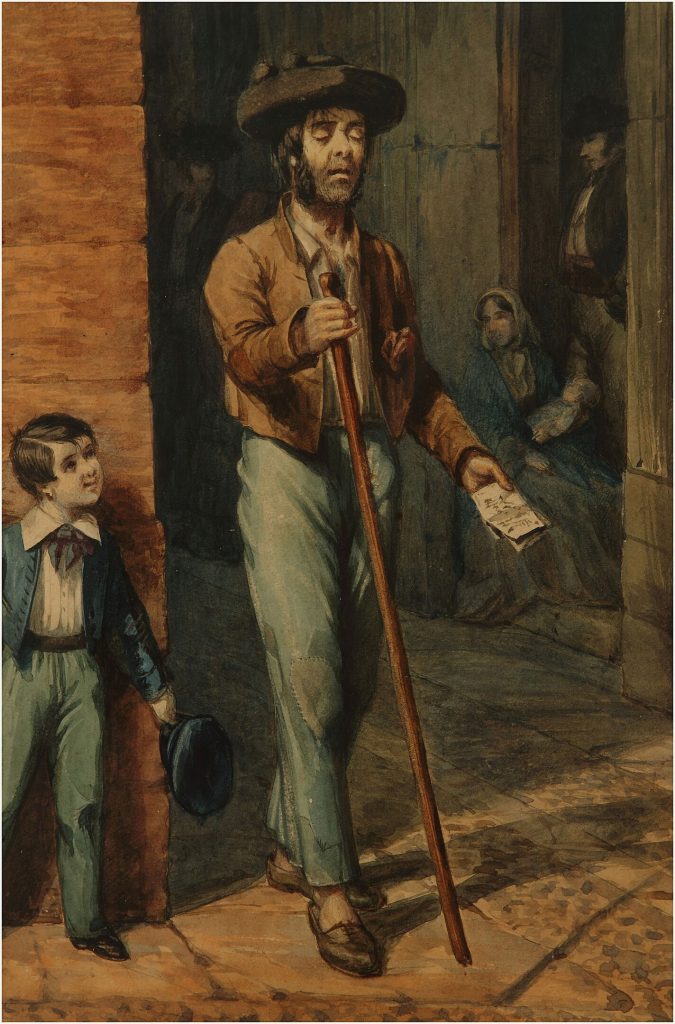

As the century progressed, Realism emerged as a counterpoint to Romanticism, focusing on the realities of everyday life. Realist artists sought to depict their subjects with honesty and precision, highlighting the experiences of ordinary people. In South America, this often meant portraying the lives of farmers, laborers, and indigenous communities, offering a more grounded and inclusive perspective on national identity. Realist art also addressed social and political issues, such as inequality and poverty, challenging viewers to confront the complexities of post-colonial society.

The interplay between Romanticism and Realism created a dynamic artistic landscape that reflected the aspirations and contradictions of South America’s emerging nations. While Romanticism provided an idealized vision of national identity, Realism grounded this vision in the lived experiences of its people. Together, these movements laid the foundation for a vibrant and diverse artistic tradition that would continue to evolve in the decades to come.

Romanticism’s Focus on Landscapes, History, and National Pride

Romanticism in South America found its most vivid expression in depictions of the continent’s awe-inspiring landscapes. Artists like Juan Manuel Blanes of Uruguay and Pedro Américo of Brazil created sweeping vistas that celebrated the natural beauty and grandeur of their homelands. These works often emphasized the vastness and untamed quality of the land, symbolizing the potential and promise of the new nations. For instance, Blanes’ painting Paraguayan Woman (1879) captured the resilience and dignity of a country recovering from war, blending Romantic ideals with historical context.

In addition to landscapes, historical themes were a cornerstone of Romantic art in South America. The independence movements of the early 19th century provided rich material for artists seeking to celebrate national heroes and pivotal events. Paintings such as The Oath of the Thirty-Three Orientals by Blanes immortalized key moments in Uruguay’s struggle for independence, while Independence or Death! by Pedro Américo dramatized Brazil’s declaration of independence. These works served not only as artistic achievements but also as tools for nation-building, inspiring pride and solidarity among their audiences.

Romanticism also delved into folklore and mythology, drawing on the region’s diverse cultural heritage. Artists incorporated elements of indigenous legends, African traditions, and European narratives to create works that reflected the cultural fusion of post-colonial society. These themes helped to establish a distinct national identity that honored the region’s complex history while looking toward the future.

The Romantic movement’s emphasis on emotion and imagination resonated deeply in a time of transformation and hope. By celebrating the beauty of the land, the heroism of its people, and the richness of its cultural traditions, Romantic art contributed to the construction of a shared identity for the young nations of South America. This celebration of identity provided a strong counterpoint to the social and political challenges that would later be explored through Realism.

Realism’s Depiction of Everyday Life and Social Struggles

As Romanticism’s idealized visions gave way to a more pragmatic view of life, Realism emerged as a dominant force in South American art during the mid- to late-19th century. This movement emphasized the accurate portrayal of ordinary people and their environments, rejecting the dramatized emotions and grandeur of Romanticism. Realist artists sought to document the realities of life in post-colonial society, often focusing on themes of labor, community, and social inequality.

One of the defining characteristics of Realism was its attention to detail and authenticity. Artists like Cándido López of Argentina and José Ferraz de Almeida Júnior of Brazil created works that captured the daily lives of rural and working-class people. López, for example, is best known for his paintings depicting scenes from the Paraguayan War (1864–1870), such as Battle of Tuyutí. His detailed, panoramic views of battlefield landscapes and soldiers’ lives provide a stark and unflinching record of the human cost of war.

Realist art also highlighted the experiences of marginalized communities, particularly indigenous peoples and Afro-descendant populations. These works often conveyed a sense of dignity and resilience, challenging prevailing stereotypes and offering a more inclusive representation of national identity. Almeida Júnior’s painting The Inopportune Visit (1898) exemplifies this approach, portraying an intimate and realistic domestic scene that resonates with universal human experiences.

In addition to its focus on individuals, Realism addressed broader social and political issues. The movement often depicted the harsh realities of inequality, poverty, and exploitation, encouraging viewers to confront these challenges. This critical perspective aligned with the growing interest in social reform during the late 19th century, making Realist art an important tool for raising awareness and fostering empathy.

By grounding its subjects in the realities of everyday life, Realism provided a counterbalance to the idealism of Romanticism. Its focus on authenticity and social consciousness helped to expand the scope of South American art, paving the way for later movements that would continue to explore the complexities of life on the continent.

Prominent Artists and Their Contributions

The Romantic and Realist movements in South America produced a wealth of influential artists whose works remain celebrated today. These individuals played a crucial role in shaping the artistic landscape of the post-colonial period, reflecting the aspirations and challenges of their time.

Juan Manuel Blanes, often referred to as the “painter of the fatherland,” was a leading figure of Romanticism in Uruguay. His works, such as The Oath of the Thirty-Three Orientals, captured the heroism and patriotism of the independence movement. Blanes also explored themes of resilience and national identity in paintings like Paraguayan Woman, which depicts the aftermath of the devastating Paraguayan War. His ability to combine historical narrative with emotional depth made him one of the most celebrated artists of his era.

In Brazil, Pedro Américo emerged as a central figure in Romantic art. His painting Independence or Death! (1888), also known as The Cry of Ipiranga, is one of the most iconic depictions of Brazil’s independence. Américo’s works often featured dramatic compositions and vivid colors, reflecting the grandeur and emotion characteristic of Romanticism. He also contributed to academic painting, helping to elevate the status of art in Brazilian society.

Realism found its champions in artists like Cándido López and José Ferraz de Almeida Júnior. López, who lost his right arm during the Paraguayan War, taught himself to paint with his left hand and produced a series of panoramic battle scenes that remain invaluable historical records. Almeida Júnior, known for his intimate and detailed depictions of rural life, captured the essence of Brazilian society in works such as The Inopportune Visit and Guitar Player. His commitment to portraying ordinary people with dignity and realism set a standard for future generations of artists.

These artists, through their diverse styles and subjects, contributed to the development of a distinct South American artistic identity. By engaging with the historical, cultural, and social realities of their time, they created works that continue to resonate and inspire.

Chapter 5: Modern Art and Innovation

The Early 20th Century as a Time of Experimentation and New Ideas

The early 20th century marked a significant turning point for South American art, as artists began to challenge traditional forms of expression and embrace new ideas. Modernism swept across the continent, fostering experimentation, abstraction, and a focus on individual creativity. Influenced by European avant-garde movements such as Cubism, Futurism, and Surrealism, South American artists integrated these trends with local themes to create unique, regionally rooted works.

This period saw a rejection of the academic art traditions that had dominated during the colonial and early post-independence eras. Artists sought to break free from rigid conventions, instead exploring new techniques and perspectives that reflected the rapid social and cultural changes of the 20th century. Urban centers like Buenos Aires, São Paulo, and Caracas became hubs of artistic innovation, where modernist ideas flourished through galleries, art schools, and intellectual circles.

A defining feature of South American modernism was its deep engagement with cultural heritage. Artists like Tarsila do Amaral of Brazil and Joaquín Torres-García of Uruguay incorporated motifs and symbols from pre-Columbian art into their works, creating a dialogue between tradition and modernity. Tarsila’s painting Abaporu (1928) became a symbol of Brazilian modernism, while Torres-García’s constructivist works reflected a belief in the universal language of art, informed by South America’s rich visual history.

This era of experimentation established South America as a center for modern art, where innovation was paired with a strong sense of cultural identity. The blending of local and global influences during this time laid the groundwork for later movements that would continue to push artistic boundaries.

Key Movements: Indigenismo, Constructivism, and Surrealism

The 20th century saw the emergence of several key movements that redefined South American art. Each movement reflected the region’s cultural diversity and its artists’ desire to assert their unique identities in a rapidly changing world.

Indigenismo, which gained prominence in the early 20th century, celebrated the art and traditions of South America’s native populations. In Peru, artists like José Sabogal played a pivotal role in this movement, using their work to honor Andean culture. Sabogal’s paintings, such as Indian Family (1931), depicted rural and indigenous life with dignity, challenging stereotypes and advocating for greater recognition of native heritage. This movement extended beyond visual art, influencing literature, music, and politics.

Constructivism also left a lasting impact on South American art, particularly through the work of Joaquín Torres-García. Torres-García developed Universal Constructivism, a style that combined geometric abstraction with symbols derived from pre-Columbian art. Works like Cosmic Monument (1938) exemplify his approach, blending modernist techniques with ancient cultural references. Constructivism later inspired the kinetic art movement in Venezuela, led by figures like Carlos Cruz-Diez and Jesús Rafael Soto, whose dynamic works explored movement and perception.

Surrealism, though originating in Europe, found fertile ground in South America’s fascination with myths, dreams, and the subconscious. Artists like Xul Solar of Argentina embraced surrealist techniques to create visionary works that blended abstract forms with spiritual and esoteric themes. Solar’s The Pianist (1923) reflects his exploration of mystical concepts and his unique perspective on modern life. Surrealism in South America often diverged from its European counterpart, focusing on local folklore and spiritual traditions.

These movements demonstrate the adaptability of South American artists, who reinterpreted global trends to suit their own cultural contexts. By addressing themes of identity, heritage, and social change, they created a distinctly South American modernism that continues to resonate today.

Prominent Artists: Tarsila do Amaral, Joaquín Torres-García, and Oswaldo Guayasamín

The modern period produced a wealth of influential South American artists who redefined the region’s artistic identity. Their innovative approaches and commitment to cultural heritage set them apart as pioneers of modernism.

Tarsila do Amaral, one of Brazil’s most celebrated modernists, played a central role in the Anthropophagic Movement, which sought to “devour” and reinterpret foreign influences in Brazilian art. Her works, such as Abaporu (1928) and The Black Woman (1923), combined avant-garde techniques with themes inspired by Brazilian folklore and landscapes. Tarsila’s art symbolized the search for a uniquely Brazilian identity during a time of cultural awakening.

Joaquín Torres-García, a Uruguayan artist and theorist, became a leading figure in modern art through his development of Universal Constructivism. His works often featured grids and geometric shapes, incorporating symbols like sun disks and llamas to reflect South America’s pre-Columbian heritage. The School of the South (1943) encapsulates his vision of an independent South American art that drew strength from its roots while engaging with global ideas.

Oswaldo Guayasamín, an Ecuadorian artist, is renowned for his emotionally charged works that addressed themes of social injustice and human suffering. His series The Age of Wrath (1960s–1990s) depicted the struggles of marginalized communities, using bold colors and expressive forms to convey the depth of human emotion. Guayasamín’s work remains a powerful example of modern art’s capacity to advocate for social change.

These artists exemplify the creativity and vision of South American modernism. Their ability to innovate while honoring their cultural heritage ensured their lasting influence on both regional and global art.

How Global Trends Inspired South American Artists

While South American modernism was deeply rooted in local culture, it was also shaped by global trends that connected the continent to the broader art world. Artists engaged with movements such as Cubism, Surrealism, and Constructivism, reinterpreting these styles to reflect their own cultural and political realities.

The influence of Cubism and Futurism is evident in works by artists like Tarsila do Amaral and Xul Solar. Both explored abstraction and fragmentation, drawing inspiration from European modernists like Picasso. However, their works also incorporated imagery tied to South American landscapes, folklore, and spirituality, creating a unique synthesis of local and global perspectives.

Constructivism, with its emphasis on geometry and abstraction, resonated with artists seeking a universal language for art. Torres-García’s fusion of pre-Columbian symbols with modernist techniques exemplifies this approach, while kinetic artists like Carlos Cruz-Diez and Jesús Rafael Soto explored new ways of engaging viewers through movement and perception.

South America’s embrace of Surrealism often diverged from its European counterpart, focusing on themes of mythology and spirituality. Xul Solar, for instance, blended surrealist techniques with esoteric and mystical themes, creating works that reflected the rich cultural tapestry of Argentina. This localized approach to Surrealism highlights the adaptability of South American artists in transforming global movements into uniquely regional expressions.

By reinterpreting global trends, South American artists not only enriched their own traditions but also contributed to the evolution of modern art on an international scale. Their works remain a testament to the creative power of cultural exchange and the resilience of local identity.

Chapter 6: Art in the Turbulent Mid-20th Century

How Political and Social Changes Influenced Art (1950s–1980s)

The mid-20th century was a time of profound political and social upheaval across South America. Dictatorships, revolutions, and widespread inequality deeply impacted the region, and these struggles were powerfully reflected in its art. Artists responded to the challenges of censorship, repression, and violence by creating works that both documented and resisted the realities of their time. Art became a vehicle for political expression, social critique, and the defense of human rights.

One of the most significant themes of this period was resistance. In countries like Argentina, Brazil, and Chile, where military regimes suppressed freedom of expression, artists used their work to challenge authoritarianism and advocate for justice. Many turned to abstraction, symbolism, and metaphor to communicate their messages while evading censorship. For instance, the Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica created interactive installations like Tropicália (1967), which critiqued the political and cultural climate of Brazil under dictatorship while celebrating the country’s vibrant heritage.

Social realism also emerged as a powerful artistic response during this period. Artists like Antonio Berni of Argentina used their work to depict the struggles of the working class and marginalized communities. Berni’s series featuring the character Juanito Laguna portrayed the hardships of life in slums, highlighting issues of poverty and inequality. Through these works, Berni not only documented the realities of urban life but also called attention to the need for social reform.

In Chile, the rise of socialist movements inspired a wave of politically charged art. The Brigada Ramona Parra, a collective of muralists, painted bold, colorful murals that celebrated workers’ rights and expressed solidarity with leftist causes. These murals, often created in public spaces, served as both art and activism, bringing political messages directly to the people. This grassroots approach reflected a broader trend in South American art, where the line between artist and activist blurred.

The turbulence of the mid-20th century profoundly shaped the direction of South American art. By addressing themes of resistance, social justice, and identity, artists not only documented the struggles of their time but also became active participants in the fight for change. Their work continues to resonate, reminding us of the enduring power of art as a force for social and political transformation.

Themes of Resistance, Repression, and Social Justice in Art

Art during this period often reflected the pervasive themes of resistance, repression, and the fight for social justice. As governments across South America implemented harsh measures to silence dissent, artists found ways to speak out, using their work as a platform for critique and resistance.

Repression was a recurring subject in the art of countries like Argentina and Chile, where military regimes employed widespread censorship and violence. Argentine artist León Ferrari created provocative works that critiqued the complicity of institutions, including the Church, in supporting authoritarian regimes. Ferrari’s La Civilización Occidental y Cristiana (1965), which juxtaposes a crucifix with a warplane, challenged the intersection of religion and militarism in a deeply divided society. His work exemplifies the courage of artists who risked persecution to confront injustice.

In Brazil, the Tropicalia movement, led by artists like Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Clark, embraced themes of cultural resistance. Tropicalia used vibrant colors, immersive installations, and multimedia approaches to critique political oppression while celebrating Brazil’s diverse cultural heritage. Oiticica’s Parangolés, wearable art pieces made from colorful fabrics, encouraged audience participation, breaking down traditional barriers between artist and viewer and fostering a sense of collective empowerment.

Social justice was another central theme, particularly in the works of artists addressing inequality and marginalization. Oswaldo Guayasamín of Ecuador created hauntingly emotional paintings that depicted the suffering of oppressed peoples. His series The Age of Wrath (1960s–1990s) portrayed the horrors of war, poverty, and injustice through bold, expressive forms and stark contrasts of color. These works served as both a lament and a call to action, urging viewers to confront the realities of human suffering.

Art during this period transcended aesthetic concerns, becoming a means of survival, resistance, and advocacy. By addressing themes of repression and social justice, South American artists played a crucial role in shaping public discourse and challenging the status quo. Their work remains a powerful testament to the resilience of the human spirit.

Notable Artists: Oswaldo Guayasamín, Antonio Berni, and León Ferrari

The mid-20th century produced some of South America’s most influential and politically engaged artists. These individuals used their creativity to respond to the challenges of their time, creating works that continue to resonate today.

Oswaldo Guayasamín, an Ecuadorian painter and sculptor, is perhaps best known for his emotionally charged series The Age of Wrath. This body of work, created over several decades, addressed themes of war, oppression, and social inequality. Paintings like Mother and Child and The Tortured use exaggerated forms and stark contrasts to convey deep human suffering. Guayasamín’s art transcended national boundaries, speaking to universal struggles for justice and dignity.

Antonio Berni of Argentina was a leading figure in social realism. His series featuring Juanito Laguna, a fictional boy from a Buenos Aires slum, depicted the challenges of poverty and urban life. Berni used found objects, such as scraps of metal and wood, to create mixed-media works that brought Juanito’s world to life. These pieces combined artistic innovation with a deep social consciousness, making Berni one of the most celebrated artists of his era.

León Ferrari, an Argentine artist and activist, created controversial works that critiqued political and religious institutions. His use of provocative imagery, such as in Western Civilization and Christianity, challenged viewers to question the systems of power that perpetuated violence and inequality. Ferrari’s fearless approach to art made him a target of censorship, but his legacy endures as a symbol of artistic resistance.

These artists exemplify the courage and creativity of South American art during a time of great turbulence. Their works not only documented the struggles of their era but also contributed to the fight for justice, ensuring their enduring relevance in the history of global art.

Art as a Tool for Activism

The mid-20th century saw the rise of art as a tool for activism in South America. Artists and collectives used their work to engage directly with social and political issues, often collaborating with grassroots movements to amplify their messages. This period blurred the boundaries between art and activism, emphasizing the power of creativity as a force for change.

Muralism became a particularly effective medium for activism, with artists using public spaces to create works that spoke directly to communities. The Brigada Ramona Parra in Chile painted murals that celebrated workers’ rights, indigenous identity, and socialist ideals. These murals, often created under the threat of censorship or violence, became symbols of resistance and solidarity, reflecting the collective spirit of their creators.

In Brazil, the Tropicalia movement embraced a multidisciplinary approach to activism, combining visual art, music, and performance. Artists like Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Clark created works that encouraged audience participation, breaking down traditional hierarchies and fostering a sense of collective empowerment. Oiticica’s Parangolés, for example, invited viewers to wear and interact with his creations, transforming art into an experience of liberation and self-expression.

Performance art also emerged as a powerful tool for activism. In Argentina, artists like Marta Minujín created immersive installations and happenings that challenged societal norms and encouraged critical reflection. Minujín’s The Parthenon of Books (1983), constructed from thousands of banned books, celebrated the return of democracy to Argentina and symbolized the triumph of free expression over censorship.

Through their innovative and courageous work, South American artists during the mid-20th century demonstrated the transformative power of art. By addressing issues of oppression, inequality, and identity, they used creativity to challenge injustice and inspire hope, leaving a lasting impact on the cultural and political landscape of the region.

Chapter 7: Art in Public Spaces and Street Art Movements

Growth of Street Art in Urban South America

The rise of street art in South America is one of the most dynamic and visible aspects of the region’s contemporary art scene. Over the past few decades, cities like São Paulo, Bogotá, Buenos Aires, and Valparaíso have become global hubs for urban art, attracting both local and international artists. The walls of these cities serve as open-air galleries, showcasing a wide range of styles, techniques, and messages that reflect the vibrancy of urban life.

Street art in South America began to flourish during the latter half of the 20th century, often as a response to political and social turmoil. In countries like Brazil and Chile, where authoritarian regimes restricted freedom of expression, graffiti and murals became tools for resistance. Artists used public spaces to voice dissent, raise awareness, and challenge the status quo. In São Paulo, the urban art scene gained momentum in the 1980s with the work of pioneers like Alex Vallauri, who is considered one of the first Brazilian street artists.

By the 2000s, street art had evolved into a prominent cultural movement, blending elements of traditional muralism with contemporary graffiti techniques. Cities like Bogotá became renowned for their vibrant murals, thanks in part to progressive policies that decriminalized street art and encouraged collaboration between artists and local governments. This shift allowed artists to experiment freely, resulting in a surge of creativity and innovation. Public art festivals and workshops further contributed to the growth of the movement, fostering a sense of community among artists and residents.

Today, South American street art is celebrated for its bold colors, intricate designs, and thought-provoking themes. It reflects the diversity and dynamism of the region, addressing issues such as inequality, environmental concerns, and cultural identity. The streets of cities like Buenos Aires and Valparaíso have become destinations for art enthusiasts, showcasing the transformative power of urban creativity.

Use of Murals and Graffiti to Address Social and Political Issues

Murals and graffiti have long been powerful tools for addressing social and political issues in South America. These art forms allow artists to engage directly with their communities, transforming walls into canvases for dialogue and protest. From large-scale murals to smaller graffiti pieces, urban art serves as both a reflection of societal concerns and a catalyst for change.

One of the most influential examples of this is the work of the Brigada Ramona Parra in Chile. This collective of muralists emerged during the 1960s and became known for their politically charged works supporting workers’ rights, indigenous identity, and socialist ideals. Their murals, characterized by bold colors and dynamic figures, adorned public spaces across Chile, bringing political messages to the forefront of everyday life. Even under the oppressive rule of Augusto Pinochet, the collective continued to create art that defied censorship and celebrated resistance.

In Bogotá, Colombia, street art has become a platform for addressing issues such as violence, inequality, and environmental degradation. Artists like Stinkfish and DJ Lu create works that blend personal expression with social commentary. Stinkfish’s colorful portraits, often based on photographs of ordinary people, celebrate individuality and humanity, while DJ Lu uses stencils to critique consumerism and political corruption. These artists use the city’s walls to amplify voices and spark conversations, fostering a sense of collective awareness.

Brazil’s street art scene has also played a significant role in addressing social issues. The twin brothers Os Gêmeos, among the country’s most famous street artists, create murals that explore themes of poverty, inequality, and cultural heritage. Their whimsical, surrealist style incorporates Brazilian folklore and urban life, connecting deeply with local audiences while resonating globally. The favelas of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo have become vibrant centers for community-driven art, where residents and artists collaborate to create murals that reflect their shared experiences and aspirations.

Through their work, South American muralists and graffiti artists have demonstrated the power of public art to challenge injustice and inspire change. By transforming public spaces into platforms for expression, they continue to shape the cultural and social fabric of their communities.

Notable Street Artists and Their Impact on Local Communities

South America has produced some of the world’s most renowned street artists, whose work has had a profound impact on local communities and the broader art world. These artists use their craft not only to beautify urban spaces but also to foster dialogue, build connections, and empower marginalized voices.

One of the most influential figures in South American street art is Os Gêmeos, the twin brothers from São Paulo, Brazil. Their distinctive murals, featuring yellow-skinned characters and dreamlike scenes, have become iconic both locally and internationally. Os Gêmeos often incorporate elements of Brazilian culture, such as music, folklore, and daily life, into their work. Their murals have transformed neighborhoods, turning neglected spaces into vibrant hubs of creativity and pride.

In Colombia, Stinkfish has made a significant impact with his bold and colorful portraits. His work often features anonymous individuals, drawn from photographs he encounters during his travels. By focusing on ordinary people, Stinkfish humanizes his subjects and creates art that resonates with local communities. His portraits celebrate diversity and individuality, fostering a sense of connection between viewers and the people depicted.

Chile’s street art scene has been shaped by artists like Inti, whose murals combine indigenous symbolism with modern aesthetics. Inti’s work often explores themes of identity, spirituality, and resistance, drawing on Chilean folklore and Andean traditions. His murals, found in cities across Chile and beyond, connect deeply with local communities, reminding viewers of their cultural roots and shared struggles.

In Buenos Aires, Argentina, the artist Mart Aire has gained recognition for his vibrant, surrealist murals that transform urban landscapes. His work often incorporates natural elements, such as plants and animals, creating a sense of harmony between the city and the environment. Mart Aire’s contributions to public art have revitalized neighborhoods and inspired a new generation of artists to explore the potential of street art.

These artists have not only elevated the status of South American street art but also demonstrated its ability to empower communities and spark meaningful conversations. Their work reflects the resilience and creativity of the region, proving that art can transform both spaces and lives.

How Street Art Reflects the Dynamism of South American Culture

Street art in South America is more than just a visual spectacle; it is a reflection of the region’s cultural dynamism and the diversity of its people. Through their work, street artists capture the complexities of urban life, addressing historical, social, and environmental themes while celebrating the vibrancy of their communities.

One of the defining features of South American street art is its connection to local culture. Artists often draw on indigenous traditions, folklore, and history to create works that resonate with their audiences. For example, murals in Bolivia frequently incorporate Andean motifs, such as condors and chacanas (Andean crosses), symbolizing cultural continuity and pride. These works not only beautify public spaces but also serve as reminders of the region’s rich heritage.

The dynamism of street art is also evident in its engagement with contemporary issues. Artists across South America tackle topics such as inequality, climate change, and gender rights, using their work to provoke thought and inspire action. In Bogotá, graffiti addressing the impact of deforestation and urbanization highlights the delicate balance between development and sustainability. Similarly, murals in São Paulo’s marginalized neighborhoods often address social inequality, reflecting the lived realities of their communities.

Collaboration and community involvement are integral to the street art movement. Public art festivals, workshops, and collective mural projects foster connections between artists and residents, creating a sense of ownership and pride in the work. These events also provide platforms for emerging artists to showcase their talents and contribute to the ongoing dialogue within the street art community.

Through its diversity of styles, themes, and techniques, street art embodies the dynamism of South American culture. It reflects the region’s ability to adapt, innovate, and celebrate its heritage while addressing the challenges of the modern world. By transforming urban spaces into canvases for expression, street art has become an integral part of South America’s cultural identity.

Chapter 8: The Influence of Nature and Spirituality in South American Art

Nature as a Recurring Motif in South American Art

Nature has always been a central theme in South American art, reflecting the region’s diverse landscapes and the deep connection its people have with the environment. From the Andean highlands to the Amazon rainforest, the continent’s geography has inspired artists to incorporate natural motifs into their work, celebrating the beauty and power of the natural world.

In pre-Columbian art, depictions of animals, plants, and celestial phenomena were common. The Chavín culture, for example, frequently portrayed jaguars, serpents, and eagles in their stone carvings, reflecting the spiritual significance of these creatures. The Nazca civilization, known for their massive geoglyphs, included figures such as the hummingbird and spider, which may have held symbolic meanings related to agriculture or cosmology. These works highlight the reverence early South American societies had for the natural world and its role in sustaining life.

During the colonial period, nature continued to appear in artistic works, though often integrated with European influences. Paintings and textiles from this era often depicted local flora and fauna, such as orchids, llamas, and condors, alongside Christian iconography. This blending of traditions reflected the merging of indigenous and colonial worldviews, as well as the enduring importance of nature in South American culture.

In modern and contemporary art, nature remains a prominent motif. Brazilian artist Tarsila do Amaral frequently incorporated elements of the natural world into her work, as seen in Antropofagia (1929), which features tropical landscapes and plants. Similarly, Ecuadorian artist Oswaldo Guayasamín often used natural imagery to symbolize human emotions and struggles. The continued presence of nature in South American art demonstrates its role as both an inspiration and a means of cultural expression.

Spiritual Beliefs and Rituals as Sources of Artistic Inspiration

Spirituality has been a driving force in South American art for millennia, shaping the themes, techniques, and materials used by artists. Whether rooted in pre-Columbian traditions, colonial Christianity, or contemporary syncretism, spiritual beliefs have provided a rich wellspring of inspiration.

In ancient South American societies, art was deeply intertwined with religious rituals and cosmology. The Inca, for instance, created Intihuatanas—stone structures thought to have been used for solar observations and ceremonies. These works were not merely functional but also imbued with spiritual significance, symbolizing the connection between the earthly and celestial realms. Similarly, the Moche civilization produced elaborate ceramics depicting scenes of rituals, sacrifices, and deities, reflecting their complex spiritual practices.

The colonial period introduced Christianity as a dominant religious force, leading to the creation of new forms of spiritual art. Churches, cathedrals, and altarpieces became major sites of artistic production, adorned with gilded sculptures, paintings, and carvings. Local artisans often incorporated indigenous symbols into Christian art, such as portraying the Virgin Mary as a mountain, a nod to the Andean earth goddess Pachamama. This syncretism allowed spiritual traditions to adapt and endure despite the cultural upheaval of colonization.

In contemporary art, spirituality continues to inspire South American artists. Peruvian artist Fernando de Szyszlo explored themes of myth and ritual in his abstract works, drawing on pre-Columbian cosmology. His painting Apu Inka (1968) evokes the sacred mountains of the Andes, blending modernist techniques with ancient symbolism. The intersection of spirituality and art remains a powerful tool for exploring identity, heritage, and the mysteries of existence.

How Geographical Diversity Shapes Artistic Expression

The geographical diversity of South America, encompassing mountains, deserts, rainforests, and coastlines, has profoundly shaped its art. Each region’s unique environment provides both inspiration and materials for artistic production, influencing styles, techniques, and themes.

In the Andean highlands, the dramatic landscapes of mountains and valleys have inspired artists for centuries. Pre-Columbian cultures like the Tiwanaku and Inca created monumental stoneworks that harmonized with the natural terrain, such as the Gateway of the Sun and Machu Picchu. These works reflect a deep understanding of the environment and a desire to integrate human creations with the natural world. In modern times, artists like Joaquín Torres-García have drawn on Andean imagery to explore themes of universal harmony and connection.

The Amazon rainforest, with its lush biodiversity, has also been a rich source of inspiration. Indigenous art from the Amazon often incorporates vibrant patterns and motifs based on local flora and fauna, such as jaguars, parrots, and snakes. These designs are not merely decorative but carry spiritual and cultural significance, often linked to shamanic practices and ecological knowledge. Contemporary artists like Brazilian painter Beatriz Milhazes have reimagined these traditions, blending tropical colors and forms with abstract modernist aesthetics.

Coastal regions have given rise to unique artistic expressions as well, influenced by the interplay of land and sea. In Peru, the Nazca Lines reflect an ancient understanding of coastal desert environments, while contemporary artists in cities like Valparaíso, Chile, have turned to urban murals that incorporate maritime themes. The ocean, rivers, and wetlands continue to inspire artists across South America, reflecting the dynamic relationship between nature and culture.

By responding to their environments, South American artists create works that are deeply rooted in place. This connection to geography not only enriches the art itself but also reinforces the cultural and ecological identity of the region.

Examples of Artworks Deeply Connected to Natural and Spiritual Themes

Throughout South American history, numerous artworks have exemplified the profound connection between art, nature, and spirituality. These works, spanning ancient times to the present, highlight the enduring significance of these themes in the region’s cultural heritage.

One of the most iconic examples is the Nazca Lines, a series of geoglyphs etched into the desert sands of southern Peru. These massive figures, including animals, plants, and geometric shapes, reflect the Nazca people’s spiritual connection to the land and their understanding of celestial cycles. Scholars believe the lines may have served as ceremonial pathways or offerings to deities, symbolizing the interplay between the earthly and the divine.

The Chavín de Huantar temple, built around 900 BC in the Andean highlands, is another masterpiece of spiritual art. This complex features intricate carvings of deities and animals, such as jaguars and serpents, which were central to Chavín cosmology. The temple’s design, with its hidden passageways and resonant acoustics, suggests it was used for rituals aimed at connecting participants with the spiritual world.

In contemporary art, Ecuadorian painter Oswaldo Guayasamín created works that blend natural and spiritual themes to explore human emotion and resilience. His painting La Edad de la Ira (The Age of Wrath) depicts human suffering against a backdrop of elemental forces, using bold forms and colors to evoke the intensity of spiritual and emotional struggles.

The Brazilian artist Lygia Pape created immersive installations that celebrated nature and spirituality. Her work Ttéia (Web), which uses golden threads to create luminous, ethereal spaces, reflects the interconnectedness of all things, drawing on both modernist principles and indigenous worldviews.

These artworks demonstrate the enduring influence of nature and spirituality on South American art. By exploring these themes, artists create works that resonate with both the past and the present, offering profound insights into the human experience.

Chapter 9: Craftsmanship and Cultural Heritage

Examination of Traditional Crafts: Weaving, Pottery, and Metalwork

Traditional crafts in South America reflect the region’s rich cultural heritage and the deep connection between artisans and their environments. Weaving, pottery, and metalwork are among the most enduring and celebrated art forms, showcasing the ingenuity and creativity of South America’s diverse cultures. These crafts are not merely functional but deeply symbolic, often carrying spiritual, social, and historical significance.

Weaving has been a cornerstone of South American craftsmanship for thousands of years. Cultures such as the Inca and the Mapuche developed complex textile techniques, creating garments and ceremonial items that were both practical and artistic. The Inca quipu, a system of knotted strings used for record-keeping, demonstrates how textiles transcended aesthetics, serving as tools for communication. Andean weavers continue to use traditional techniques, crafting textiles that feature geometric patterns, vibrant colors, and motifs inspired by nature and mythology.

Pottery also holds a prominent place in South America’s artisanal traditions. The Moche civilization of northern Peru, active from AD 100 to AD 800, is particularly renowned for its ceramic art. Moche pottery often depicted realistic portraits, animals, and scenes from daily life, providing a vivid glimpse into their society. Today, communities across South America, such as those in the Amazon Basin, continue to create pottery using ancient techniques, often incorporating indigenous designs and natural pigments.

Metalwork has long been a symbol of power and spirituality in South America. Pre-Columbian cultures like the Chavín and Inca were skilled in working with gold, silver, and copper, creating intricate jewelry, ceremonial objects, and tools. The Tumi knife, a ceremonial blade often adorned with animal and deity motifs, exemplifies the sophistication of Andean metalwork. Modern artisans in regions such as Peru and Colombia continue to draw on these traditions, crafting jewelry and decorative items that blend ancient techniques with contemporary styles.

These crafts not only highlight the technical skill of South American artisans but also serve as vital expressions of cultural identity. By preserving traditional methods and incorporating modern innovations, artisans ensure that these art forms remain relevant and vibrant.

Stories Behind Techniques Passed Down Through Generations

The preservation of traditional crafts in South America is a testament to the resilience and ingenuity of its people. Techniques passed down through generations carry the stories, values, and histories of their communities, connecting past and present in meaningful ways.

Weaving is deeply rooted in Andean culture, where knowledge of textile production has been handed down for centuries. In many communities, weaving is more than an art—it is a way of life, with techniques learned from elders and refined over time. The use of natural dyes, such as cochineal for red and indigo for blue, reflects the close relationship between artisans and their environment. Patterns in textiles often carry symbolic meanings, representing familial ties, agricultural cycles, or spiritual beliefs. For example, the chakanas (Andean crosses) frequently woven into textiles symbolize the interconnectedness of the natural and spiritual worlds.