Kobe was never meant to be ordinary. Cradled between the Rokko mountain range and the Seto Inland Sea, the city’s topography forces a kind of vertical tension between land and water, shelter and openness. Unlike Japan’s ancient capitals—Kyoto, Nara, or even nearby Osaka—Kobe did not evolve around a court, a shrine, or a castle. Its identity was always maritime, always outward-facing, and always slightly at odds with the idea of national centrality. From its earliest development, Kobe was a threshold, a place where the foreign arrived and the domestic adapted.

The City Shaped by the Sea

Before it was called Kobe, the area was known as Hyōgo and, still earlier, as Owada-no-tomari—a port station during the Nara and Heian periods. As far back as the 8th century AD, Hyōgo played a role in imperial logistics, functioning as a departure point for official embassies to China under the Tang dynasty. Its function as a harbor was never merely practical; it formed the basis for early visual motifs that recurred across centuries. Waves, ships, fishing nets, and the curve of the coastline appear in temple paintings, kimono design, and ceramics. The sea wasn’t just economic—it was sacred, too.

Ikuta Shrine, one of the oldest Shinto shrines in the country, stands as a spiritual anchor amid the city’s changing tides. Founded around AD 201, it honors the sun goddess Amaterasu’s younger sibling, Wakahirume, a lesser-known deity of weaving and dawn. The shrine’s visual culture—bright vermilion lacquer, votive ema paintings, and seasonal floral displays—rooted Kobe’s aesthetic consciousness in a native visual grammar long before foreign ships ever docked at its piers.

But the same waters that enabled shrine-building also invited outsiders. Between the 10th and 15th centuries, pirates, traders, and monks flowed through the region. Artifacts from the Seto Inland Sea attest to cultural exchanges between Japan, Korea, and China: lacquer boxes with Korean mother-of-pearl inlay, inkstones carved in Southern Song style, and Buddhist statuary showing Chinese stylistic influence. Even before Japan formally reopened to the West in the 19th century, Kobe had already developed a visual vocabulary steeped in hybridity.

Between the Mountains and the Water

Kobe’s unique geography—a long, narrow strip between mountain and sea—has shaped not just its infrastructure but its artistic mentality. The mountains, especially Mount Rokko, serve as both a literal and figurative backdrop. Artists based in the city have frequently turned to the mountainside for both contemplative subject matter and formal structure. Edo-period folding screens from the region often show a vertical cascade: temple rooftops nestled amid hills, pine trees sweeping down to the bay, ships dotted along the shore. The verticality becomes compositional logic.

This topographical constraint also created a kind of psychological tightness. Kobe developed an art scene that was more compact, more discreet than Tokyo’s sprawling avant-garde or Kyoto’s heritage-soaked studios. Art was often embedded in domestic spaces or tucked into hillside temples. Some historians believe this encouraged a quieter, more intimate mode of creativity. Instead of grandiose scrolls or imperial commissions, Kobe artists excelled in calligraphy, small-scale ceramics, and artisanal crafts.

At the same time, this limited space forced Kobe to build upward and outward in unusual ways. Its port expanded onto artificial islands like Port Island and Rokko Island—later home to museums, galleries, and international expositions. These man-made extensions became canvases themselves, allowing for large-scale public sculpture and harbor-side installations in the 20th and 21st centuries. The city quite literally reshaped its geography to accommodate its aesthetic ambitions.

A Tangle of Trade, Faith, and Craft

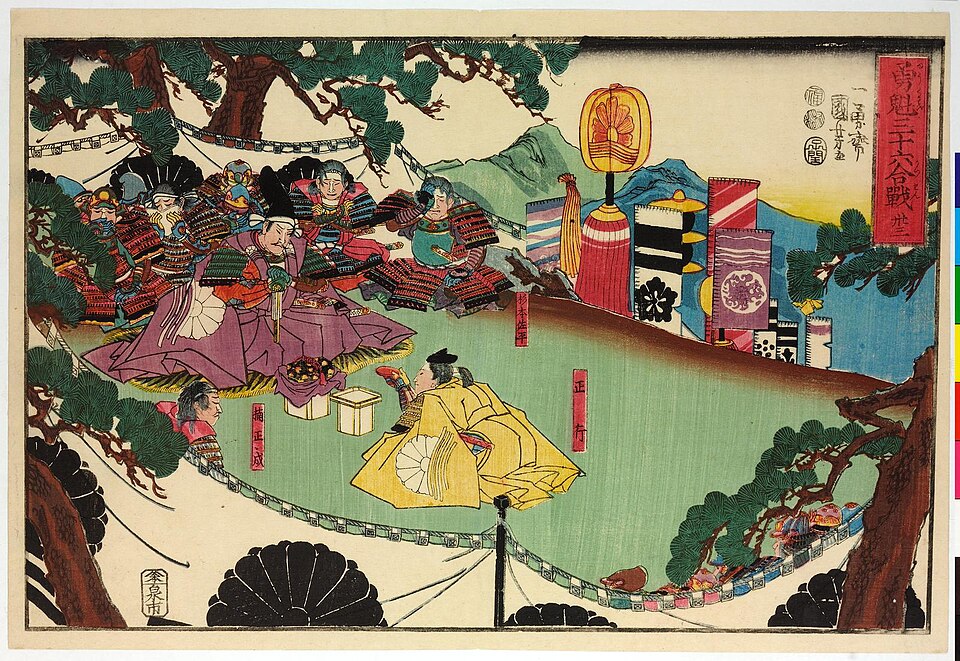

By the late medieval period, Kobe’s harbor was humming with trade, and with it came the visual culture of transaction. Merchant guilds, especially sake brewers and shipping magnates, began commissioning votive paintings, decorative screens, and even sponsorships of local festivals—acts that were part religious, part civic branding. A surviving 17th-century emakimono scroll from the Hyōgo area depicts a sake brewer’s festival float, decked in miniature torii gates, golden dragons, and fluttering banners. It is both sacred procession and advertisement.

Kobe’s access to international goods also transformed local crafts. Chinese celadons and Korean buncheong ware inspired potters in the Nada and Tarumi districts. Ivory and tortoiseshell, brought through foreign ships, found their way into comb-making and small decorative objects. By the Edo period, Hyōgo’s artisans had developed a distinct style of lacquerware known for incorporating mother-of-pearl and powdered gold into maritime themes—waves, cranes, and compass roses.

The port also brought missionaries. Jesuit and Franciscan art found its way to Kobe’s Christian enclaves in the 16th century, surviving underground after Christianity was banned in the 1620s. Though less is documented here than in Nagasaki or Kyoto, fragments of religious art—wooden crosses, Madonna miniatures, rosaries—occasionally surface in Kobe-area collections, hinting at a hidden subculture of devotional craftsmanship.

This cross-cultural friction—between Buddhism and Christianity, merchant and monk, native style and foreign taste—created a tension that continues to animate Kobe’s visual identity. It is not a city of static traditions but of negotiated aesthetics.

Kobe’s geography gave it no choice but to face outward. In that facing, it absorbed currents from across the sea and from within its mountains. That early hybridity, born of topography and trade, shaped a city whose artistic culture would remain porous, experimental, and surprisingly resilient—especially in the face of catastrophe and change, as later sections will reveal.

Sacred Beginnings: Buddhist, Shinto, and Folk Traditions in Early Kobe

Before Kobe became a modern port city, it was a patchwork of villages, shrines, and temple grounds—each one inscribed with religious meaning and ritual craft. While later centuries brought oil paint and international exhibitions, the foundation of Kobe’s visual heritage lies in its spiritual history. From ancient Shinto sanctuaries like Ikuta Jinja to Buddhist temples adorned with mandalas and statuary, the sacred defined both the function and form of early Kobe art. This legacy remains visible not just in museums, but in the city’s rituals, architecture, and aesthetic memory.

Shrines of the Ikuta Plain

At the heart of Kobe’s religious and artistic history stands Ikuta Shrine, one of the oldest in all of Japan. Founded, according to tradition, in the early 3rd century AD by Empress Jingū, the shrine occupies a broad plain once known as Ikuta no Mori—the forest of Ikuta. Though much of the surrounding woodland has vanished beneath urban sprawl, the shrine’s design retains the symbolic geometry and chromatic power of ancient Shinto architecture. Its brilliant vermilion gate (torii), sweeping gabled rooflines, and ritual banners form an aesthetic vocabulary that influenced local art across mediums.

The shrine was more than a religious institution. It was a sponsor of visual production. Votive ema—small wooden plaques bearing prayers or thanks—offer some of the most accessible glimpses into Edo-period folk imagery. Painted with everything from horses and foxes to contemporary events and epidemics, these ema reflect the concerns, humor, and hopes of ordinary worshippers. A rare surviving example from the late 18th century depicts a local ship surviving a storm off the Kobe coast, with miniature waves rendered in stylized cobalt ink. It is not only a prayer for protection, but a maritime landscape in miniature.

During the Heian and Kamakura periods, court-sponsored pilgrimage routes to Kobe included artistic offerings such as ritual fans, textiles, and lacquered boxes, many of which were crafted with regional motifs: cranes, pine trees, and sea spray. These items did not merely decorate worship; they extended the shrine’s sacred aura into private homes and personal devotions.

Temple Art and Esoteric Imagery

Buddhism arrived in the Hyōgo region by the 7th century AD, and with it came a flood of visual forms—mandalas, icons, sutra scrolls, and statues carved from wood and bronze. While Kyoto and Nara retained their status as religious capitals, Kobe’s temples were no less ambitious in their visual complexity. Chief among these was Taisan-ji, a Tendai temple whose founding is attributed to Prince Shōtoku. Though repeatedly rebuilt, it still houses one of the oldest wooden temple gates in Western Japan.

Taisan-ji and other Kobe-area temples were shaped by esoteric Buddhism, particularly the Shingon and Tendai sects, which emphasized ritual, secrecy, and elaborate symbolism. Art in these contexts was not decorative—it was functional. Mandalas used in meditation, guardian figures flanking temple gates, and altarpieces depicting cosmic Buddhas all served as visual aids in the quest for enlightenment. The sculptor Unkei’s influence, for example, can be felt in surviving figures of Kongōrikishi—muscular temple guardians with fierce expressions and swirling drapery—crafted by anonymous local artists in the 12th and 13th centuries.

A particularly fine example of Kobe’s early temple art is the painted ceiling tiles of Gokuraku-ji, a now-defunct Pure Land temple once located near the modern Nagata district. These tiles, recovered during archaeological excavations in the early 20th century, show stylized lotus blossoms and gilded clouds rendered in mineral pigments and gold leaf. They signal both the technical sophistication and devotional purpose of Kobe’s Buddhist artisans.

Kobe’s port access allowed these religious objects to be influenced by Chinese Song and Yuan dynasty painting, especially in ink technique. By the 14th century, local monks were practicing suiboku-ga (ink wash painting), incorporating Chinese compositional principles into Japanese religious subject matter. A 15th-century handscroll attributed to a Kobe monk depicts the “Oxherding” parable, where the spiritual journey toward enlightenment is rendered in a sequence of expressive brushstrokes, growing fainter and more abstract as the narrative progresses.

Folk Talismans and Maritime Icons

Beyond the elite visual worlds of shrine and temple, Kobe’s early visual culture was rich with folk objects—functional, protective, and personal. Coastal fishing villages developed their own aesthetic traditions, many of them rooted in talismanic art. Small painted netsuke, woodblock amulets, and house charms called ofuda circulated among working families. These items often featured images of Ebisu, the god of fishermen and good fortune, who became something of a local mascot. In Kobe’s Nada and Tarumi districts, Ebisu was not simply painted in shrines—he was mass-produced on cloth, paper, and ceramic figurines for household use.

Particularly striking are the gyotaku (fish prints) made by fishermen during the late Edo period. Originally intended as records of prize catches, these ink impressions of actual fish pressed against paper evolved into a folk art form. Kobe’s fishing culture adopted gyotaku not just as documentation but as charm—imprinted with prayers for abundance and signed with the names of boat crews. The prints, often ghostly and delicate, became haunting portraits of the sea’s bounty and mystery.

Seasonal festivals provided further opportunities for folk artistry. Lanterns, floats, festival banners, and hand fans all featured bold designs—many incorporating maritime and religious imagery. The Tōka Ebisu Festival, still held each January in Kobe’s Nishinomiya ward, exemplifies the fusion of folk, commerce, and spiritual design. Merchants pray for prosperity using colorful fukusasa (lucky bamboo branches) adorned with paper charms, miniature coins, and talismans crafted by local artisans. The visual exuberance of this event has roots going back centuries.

Kobe’s early art history, then, is not confined to palaces or temples. It is sewn into festival garb, burned into protective amulets, and brushed onto votive plaques. This blending of sacred and ordinary objects forms the emotional spine of Kobe’s aesthetic identity—an identity later challenged, but never quite broken, by industrialization, disaster, and modernism.

The sacred traditions of early Kobe offer more than a backdrop. They provide the moral and visual framework into which later developments—Western painting, commercial illustration, and avant-garde performance—would enter and sometimes clash. Kobe did not abandon its religious heritage when it modernized; rather, it absorbed and adapted it. The result is a city where a Buddhist mandala might hang beside a European oil painting, and where a Shinto shrine still echoes in the modern museum’s minimalist facade.

Hyōgo-tsu and Harbor Vision: Art of the Port in the Tokugawa Period

A harbor makes its own pictures. During the Tokugawa period, Kobe—then widely called Hyōgo or Hyōgo-tsu—became a place where maritime life and popular visual culture braided together. The long peace of the Tokugawa era allowed towns on the Seto Inland Sea to prosper as nodes of commerce and travel, producing a distinct visual output: festival banners and fish prints, guidebook landscapes and woodblock scenes, decorated trade objects and gambler’s charms. The harbor was both subject and studio, and its work was honest, practical, and full of small surprises.

Merchant Eyes on the World

The Tokugawa period (commonly dated 1603–1868 AD) centralized political power in Edo but also strengthened regional commerce and urban culture. Ports like Hyōgo expanded as domestic trade routes proliferated; coastal shipping (kitamaebune routes) carried rice, sake, textiles, and news, and the images that circulated with those goods shaped how people saw the harbor. Ukiyo-e artists and local printmakers drew the port not as a grand imperial stage but as an everyday theater—sailors mending nets, brokers tallying cargo, hawkers calling from the quay. These were not academic landscapes; they were working views, full of detail and motion. Prints from the period show wide shallow bays, sails like folded fans, and bridges strung with pedestrians—visual shorthand for a place defined by commerce and constant arrival. This local imagery survives in museum collections and in the Hyōgo-no-Tsu Museum’s own display of an 1868 panoramic view of the port. Wikipedia+1

A small micro-narrative: a wandering merchant’s ledger found in an archival box records a single trip from Osaka to Hyōgo in the 18th century. Between entries of rice and salt, someone sketched a bow of a ship and a tiny fish—an economist’s margin turned into a fisherman’s portrait. Those margins are the archive of a working visual culture.

Popular Printmaking and the Harbor’s Iconography

Woodblock prints and illustrated guidebooks established Hyōgo’s image for travelers and townspeople alike. Artists working in the popular traditions adapted familiar motifs—pine, wave, mountain—to the port’s peculiar geography. The result is a visual vocabulary that treats human activity as landscape detail rather than the other way around. Scenic series that included Hyōgo presented the port as both picturesque and everyday, a place where ritual and trade were inseparable: festival floats passing under sailing junks, temple gates looking over warehouses.

Three short features often recur in these prints:

- Sails and rigging rendered as rhythmic patterns.

- Market stalls clustered against seawalls.

- Bridge crowds acting as a human tide flowing between mountains and sea.

Ukiyo-e prints that show the Seto Inland Sea and Hyōgo in this period underline how the port’s image traveled across Japan and into Western collections later on. These prints are evidence that Hyōgo was no provincial backwater; it was part of a national visual conversation.

Craft and Souvenir: Objects for Travel and Trade

The harbor economy fed a secondary economy of craft geared to visitors. Motomachi and other lanes near the water produced combs, lacquerware, and small carved toys—objects meant to travel home as proof of passage. When the port later opened more widely to foreign visitors after AD 1868, these crafts became the seed of a souvenir industry, but the roots go deeper: in the late Tokugawa era, local artisans already tailored goods for sailors and inland travelers.

A useful list of harbor-made items that defined Hyōgo’s sensibility:

- Lacquer boxes and combs decorated with mother-of-pearl and wave motifs.

- Gyotaku fish prints used to document catches and as lucky charms.

- Festival paraphernalia—lanterns, banners, and portable shrine accoutrements—that doubled as merchant advertising.

Gyotaku, in particular, deserves a paragraph of attention. What began as a practical record of a noteworthy catch became a delicate folk print, inked direct from fish to paper and then signed. The impressions read like maritime portraits: the fins and scales register as honest testimony, and the prints themselves were sometimes carried as talismans on ships or sold to shore-side patrons. That convergence of work, devotion, and souvenir-making exemplifies the harbor’s visual economy.

A Mid-Section Surprise: Port Views as Early Media

It is easy to think of Tokugawa-era images as quaint records, but some functioned like early mass media. Illustrated broadsides and guidebooks circulated news—ship arrivals, fares, prices—and sometimes satire. The port’s pictorial output could include biting comment: caricatured brokers, exaggerated tides of human traffic, and cleverly captioned views that mocked local scandals. In other words, Hyōgo’s visual scene participated in a lively public discourse, and artists were chroniclers, pundits, and entertainers rolled into one.

This civic visuality also anticipated the later tourist gaze. By the end of the Tokugawa period, prints and painted panoramas began to serve the same role as the souvenir postcard a century later: they codified what to remember about a place. One such panorama of Hyōgo from 1868 survives in modern displays and shows the port poised on the cusp of larger change. Matcha Guide

The Harbor’s Long Reach

The art of Hyōgo-tsu in the Tokugawa period is less about breakthroughs in form than about steady, civic visual practice. The port painted itself into being through prints, crafts, and everyday images that matched the rhythm of trade and festival. That practical artistry proved durable: later waves of Western influence and industrial design found a local culture already fluent in exchangeable images. The harbor, in short, was both subject and teacher—teaching future generations how to see a city that lived by the water.

The Black Ships Arrive: Kobe Opens to the West

In 1868, the port of Kobe officially opened to foreign trade under imperial edict. The timing was precise and symbolic. That same year marked the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate and the restoration of imperial power under Emperor Meiji—a political revolution that mirrored the aesthetic rupture now descending upon cities like Kobe. Long shaped by its position between mountain and sea, Kobe would now be shaped by something else entirely: the arrival of the West. Ships flying Dutch, British, French, and American flags entered Hyōgo Bay not as visitors, but as treaty partners with extraterritorial rights. Art changed accordingly. It absorbed new tools, new audiences, and entirely new assumptions about space, realism, and display.

The Meiji Restoration and Treaty Ports

The 1858 Harris Treaty, and its subsequent implementation, required Japan to open five treaty ports to foreign powers. Kobe, though not originally one of the five, was designated as a key foreign settlement under imperial authority by 1868, absorbing trade formerly directed toward the nearby port of Osaka. The Japanese state, newly restructured and modernizing at speed, built up Kobe rapidly as a showcase of openness and “civilized” progress. The city’s art culture followed suit.

Kobe’s new foreign concession district—laid out in grid formation, designed by British civil engineers—functioned as a kind of experimental aesthetic zone. Brick buildings replaced wooden ones; glass windows appeared alongside tiled roofs. Oil paintings, framed and displayed on walls, began to circulate among Japanese elites exposed to Western styles. Furniture and interior design shifted to reflect imported tastes, and with that came different expectations for what art should look like and where it should live.

Artists were sent abroad—most notably to France and Italy—and came back not only with training but with a transformed visual grammar: one rooted in linear perspective, chiaroscuro, anatomical correctness, and historical narrative painting. The young Kobe-based painter Harada Naojirō, for example, would later become known for his dramatic and emotive Western-style canvases, trained initially in part through the influence of Western residents in Kobe and Osaka.

While Tokyo absorbed the political authority of the new regime, Kobe became one of its faces abroad. And faces needed images.

Yōga and Nihonga in a Divided Art Scene

Out of this upheaval emerged the Meiji-era art duality that dominated the late 19th century: Yōga (Western-style painting) and Nihonga (Japanese-style painting). Kobe produced champions of both, often within the same studios. Yōga introduced not only oil on canvas, but also formal academic training, including life drawing, classical composition, and studio critique. The Kobe Municipal School of Painting, established in the early 20th century, offered one of the Kansai region’s earliest formal instruction environments for Yōga, emphasizing Western anatomy and color theory.

At the same time, the Nihonga movement took shape in deliberate response to these Western imports. Artists in Kobe adapted traditional Japanese painting techniques—ink on silk or paper, mineral pigments, and gold leaf—but often infused them with Western framing or subject matter. The resulting hybrid style sometimes resembled European symbolism filtered through Kyoto school sensibility.

One painting from the 1890s by a Kobe artist—now housed in the Hyōgo Prefectural Museum of Art—depicts a tea ceremony held in a Western-style drawing room, complete with gas lighting and upholstered chairs. The figures are rendered in Nihonga style, with pale faces and flowing robes, but the setting is unmistakably foreign. The collision is not treated as awkward, but as elegant, serene. That tonal blending became a local specialty.

Many artists in Kobe, unlike their Tokyo counterparts, resisted full adoption of Western realism. They incorporated what was useful, but refused to discard brush tradition, textile sensibility, or native iconography. Mountains and seascapes, for instance, continued to be painted in ink long after oil became fashionable—albeit sometimes mounted in Western frames and sold to foreign clients.

The Foreign Concession’s Visual Footprint

Beyond the canvas, Kobe’s built environment began functioning as image and influence. In the late 19th century, the city was dotted with Western-style houses, consulates, and churches. These were not simply residences; they were monuments to a new world order, and their architecture inspired local interpretations. The Ijinkan, or “foreign residences,” especially those in the Kitano district, brought a new sense of exterior aesthetics to Japanese city planning. Iron gates, decorative cornices, glass-paneled verandas—these became motifs for lithographs, illustrations, and even kimono embroidery.

Japanese artisans began crafting wares tailored to Western tastes: porcelain tea sets with European floral motifs, lacquer boxes with mythological scenes framed like salon paintings. Kobe’s proximity to both industrial Osaka and maritime routes gave it unique access to global trends and mass production, but the best objects still bore the hand of the craftsman.

Westerners, too, began collecting and documenting Japanese art. Missionaries and merchants in Kobe assembled early collections of ukiyo-e prints, ceramics, and Buddhist artifacts, many of which were later donated to institutions like the British Museum or the Musée Guimet. Their selections and interpretations, though filtered through foreign eyes, further propelled Kobe’s artistic identity into international awareness.

A revealing example: in 1875, a French merchant living in Kobe commissioned a series of woodblock prints from a local artist, depicting scenes of Kobe’s street life. The resulting images show rickshaw pullers, teahouse girls, and porters—but all framed in the rigid symmetry of European postcard design. This was not Japanese art for Japanese eyes; it was Kobe staged for export.

The city itself became image. Its hills and harbor were painted, printed, photographed, and displayed abroad as signs of Japanese openness and modern potential. Yet, beneath these polished surfaces, a quieter negotiation was underway—one that preserved local techniques and traditional forms even as they were repackaged for new patrons.

Brick and Brushstroke: The Emergence of Artistic Modernity in Kobe

Kobe’s modernization wasn’t just about factories and railways. It was about paint, paper, iron, and ideas. In the decades following the port’s opening, the city developed not merely as an industrial node but as a center of emerging modern artistic thought—quietly but decisively distinct from Tokyo’s imperial culture and Kyoto’s classical heritage. Kobe fostered a practical modernity, shaped by merchants, engineers, and autodidacts rather than court painters or elite critics. Art was no longer confined to the temple, the academy, or the tourist postcard. It moved into private studios, middle-class homes, and eventually the city’s first purpose-built galleries.

New Materials, New Subjects

The arrival of Western materials—oil paint, synthetic dyes, glass for framing, and imported paper—allowed Kobe artists to experiment with unprecedented freedom. Oil paints made possible a broader range of tonal variation and permanence than traditional Japanese pigments. Pencils, previously rare, became common; sketchbooks proliferated among students and amateurs alike. New subject matter followed.

One of the most visible changes was a shift toward the urban scene as a legitimate subject. While Kyoto painters still favored temple gardens and classical figures, Kobe artists began painting ships, streetcars, rail yards, gas lamps, and the interior of cafés. These were not just genre paintings; they were visual affirmations that daily life in a modern city was worthy of depiction.

In a telling example from around 1910, a Kobe painter rendered a panoramic oil view of the port as seen from Mount Rokko. Smoke stacks rise behind the sails of merchant ships, and a telegraph wire cuts diagonally across the canvas. It is not romanticized. It is clear-eyed, industrial, and layered—an early example of a distinctly Kobe perspective: not the quaint East for foreign eyes, but the layered reality of a Japanese port transforming itself.

Street portraiture also emerged as a mode of democratic modernism. Artists painted the faces of schoolteachers, clerks, and dock workers—not idealized, but specific. Some of these portraits were sold through small exhibitions or even door-to-door, a hybrid of commerce and culture unique to this in-between city.

The Kobe Bijutsukan and Early Collectors

As the middle class grew, so did the appetite for collecting and exhibiting art. One of the key institutions in this regard was the Kobe Bijutsukan (Kobe Art Museum), established in the early Taishō period. Though modest by Tokyo standards, it played a crucial role in legitimizing art as both education and civic identity.

The museum’s early exhibitions leaned heavily on Western-influenced work: still lifes, landscapes, and figure studies rendered in oil. These exhibitions were not simply aesthetic; they were educational, meant to “train the eye” of the new citizen. Brochures often explained perspective, shading, and the difference between “true color” and “conventional color,” echoing Meiji-era pedagogical goals.

Kobe’s new collectors were not aristocrats but shipping magnates, doctors, and educators. Their tastes mixed European imports with regional Japanese craft. Some collected Meiji-era cloisonné and Satsuma ware alongside French prints and British watercolors. The result was a kind of cosmopolitan eclecticism—elegant, but unsystematic. This environment helped local artists thrive outside the rigid schools of Tokyo and Kyoto.

By the 1920s, informal salons had begun forming in private homes and back rooms of cafés, where artists would show work, argue over ideas, and sometimes collaborate across genre lines. These groups rarely issued manifestos or entered official academies, but their influence was palpable in Kobe’s visual culture: more experimental, more personal, and less constrained by orthodoxy.

Women Painters and Private Studios

One of the quieter revolutions of this era was the emergence of women artists working in private studios. While formal art education remained largely male-dominated, several women in Kobe began exhibiting work—often in subtle defiance of social expectations.

Yamamoto Midori, a painter born in Kobe in 1894, produced a series of oil portraits and floral studies from her home studio in the Nada district. While she never joined an official movement, her work appeared in regional exhibitions and was acquired by a few prominent Kobe collectors. Her painting of a child reading beside a charcoal heater—both intimate and compositionally sophisticated—reflected a blend of European technique and domestic subject matter not often seen in the major salons.

Kobe’s relatively liberal social atmosphere—shaped by its foreign population, merchant-class values, and distance from Japan’s political center—allowed for such exceptions to take root. Women’s art was often shown at smaller venues, but its visibility marked an early and distinctive shift. These painters frequently focused on:

- Intimate domestic interiors.

- Still life studies with symbolic overtones.

- Female self-portraiture rendered with quiet defiance.

Their contributions were rarely canonized but left an enduring imprint on the city’s private collections and amateur painting circles. Some even taught in girls’ schools or ran informal ateliers, influencing generations who never made the jump to the Tokyo or Kyoto scenes.

These small rooms of creativity—often no more than a tatami-matted corner behind a curtain—formed a counter-tradition to the grand narratives of modernization. Their significance lay not in manifesto but in method: quiet, sustained, personal, and rooted in a new sense of visual autonomy.

Cosmopolitan Canvas: Kobe Artists in Global Dialogue (1900–1945)

By the early 20th century, Kobe was no longer just a port; it was a cultural relay station. Ideas, images, and materials moved in and out of its bay as fluently as cargo. Painters studied in Paris and Berlin, then returned with modernist impulses half-digested but wholly committed. Foreign artists settled in Kobe or passed through, leaving behind new ways of seeing. Galleries exhibited Japanese work alongside European prints. Critics argued, studios flourished, and young painters experimented. Kobe’s artistic scene in the first half of the 20th century was not imitative—it was cosmopolitan in the truest sense: rooted locally, yet irreversibly shaped by the international.

Studying Abroad and Bringing It Back

The path from Kobe to Paris was well worn by the 1910s. Art students from the Kansai region often sailed from the city’s own harbor to Europe, where they studied under Western painters, absorbed new techniques, and tried to reconcile them with what they had left behind. Some trained at the Académie Julian or under well-known French painters of the late Impressionist or post-Impressionist schools. Others gravitated toward Germany, where the academic realist tradition was still strong, or even to Russia, where theatrical design and constructivist aesthetics left their mark.

Upon returning to Kobe, these artists introduced new approaches to color, composition, and content:

- Brighter palettes influenced by Fauvism.

- Geometric structure rooted in Cubism or early abstraction.

- A stronger emphasis on figuration, often drawn from life studies rarely seen in pre-Meiji Japanese painting.

One telling example is Takamura Kōtarō, who visited Europe in the early 1910s (though not a Kobe native, his influence extended into the city’s circles). His 1914 Portrait of an Old Woman, shown at exhibitions in both Osaka and Kobe, reflected Cézanne’s compositional depth and Renoir’s warmth, but with a distinctly Japanese gravity in the treatment of the figure.

In Kobe itself, returning painters formed small study groups and societies. The most influential among them was the Kobe Shinkō Bijutsu Kyōkai (Kobe Progressive Art Association), founded in 1923. It held exhibitions of Western-style painting and sculpture and actively encouraged members to engage with foreign publications and artistic debates. While Tokyo was home to the government-sponsored Bunten exhibitions, Kobe’s scene remained more experimental, decentralized, and privately funded.

Printmaking as Protest and Poetry

Another current running through Kobe’s art scene during this period was the rise of sōsaku hanga—the “creative print” movement. Unlike traditional ukiyo-e, where design, carving, and printing were divided among specialists, sōsaku hanga artists controlled every stage of production themselves. This was art as personal expression, not commercial product.

Kobe played a vital role in the movement’s Kansai variant. Artists like Hiratsuka Un’ichi and Maekawa Senpan showed work at Kobe exhibitions and collaborated with local printers. These prints were typically monochromatic or used restrained color palettes, and their subjects often reflected internal landscapes: a lone figure in a harbor alley, an aging house, a memory of childhood on Mount Rokko.

While Tokyo’s hanga scene leaned toward urban abstraction or leftist political content, Kobe’s prints were more lyrical, contemplative, even melancholic. This mood owed something to the city’s geography—its narrow quarters between sea and hill, its misty mornings, its delicate balance between flux and enclosure.

One 1932 woodblock by a Kobe-based artist titled Evening Ferry shows a single boat moving across a gray sea, with the hills behind fading into layered strokes. It is neither romantic nor despairing—just observant, inward, and remarkably modern in its spareness.

But hanga could also be defiant. As Japan moved deeper into militarism during the 1930s, some Kobe artists began embedding quiet protest in their work. A landscape might hide a subtle sign of industrial encroachment. A child’s face might carry a shadow too deep for innocence. These works weren’t openly subversive, but they refused to flatter the dominant narrative of progress and strength.

Art Under the Rising Sun

As the 1930s gave way to war, Japanese art was increasingly brought into the service of the state. Official exhibitions promoted patriotic themes, heroic figures, and historical glorification. Kobe, with its naval significance and foreign population, was drawn into this system—but not without friction.

Several Kobe artists were conscripted to paint war scenes or produce propaganda, especially after the full outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937. However, others managed to skirt these demands through landscape painting, still lifes, or abstract work that bore no immediate ideological content.

There is one particularly haunting example of wartime painting from a Kobe artist: a 1942 oil work titled Warehouse, Night, depicting a dockside structure lit by a single hanging bulb, with shadows stretching like claws across the boarded windows. Officially, it was submitted as an image of “military logistics,” but its mood is stark and desolate—a veiled lament under the guise of duty.

Censorship tightened by 1940. Exhibitions required approval, and foreign texts or influences were viewed with suspicion. Nonetheless, Kobe’s position as a port city created some breathing room. Foreign residents, though dwindling, still had connections to Europe and China. Some foreign books and prints continued to circulate quietly through private hands.

Artists began working in smaller formats, often hidden from public view. Sketchbooks from this period are full of nonconformist work—abstract shapes, religious iconography, and coded visual metaphors. These were not mass movements but individual acts of preservation.

Ruins and Renewal: Art After the Bombing

On the night of March 17, 1945, Kobe was engulfed in fire. American B-29 bombers dropped incendiary explosives over the city in a calculated act of total warfare. Thousands died, entire neighborhoods vanished, and much of the port was reduced to blackened rubble by morning. The destruction was not incidental—it was strategic. Kobe had long been a key naval and industrial hub, and its tight geography made it especially vulnerable to firebombing. Yet amid the devastation, something else persisted: a need to make sense of loss, and a need to create. In the years following the war, Kobe’s artists responded not with slogans or protest banners, but with the slow, private labor of rebuilding culture.

The Firebombing of Kobe (1945)

The Allied firebombing campaign of Japan spared almost no major city, but Kobe’s suffering was particularly acute. With over 8,000 tons of bombs dropped on the city across multiple raids, its central districts were flattened. Historic neighborhoods like Sannomiya and Motomachi burned to the ground. Art studios, print shops, and galleries were among the casualties. Private collections—some dating back to the Meiji period—were destroyed or looted. What survived was often hidden, buried, or salvaged from ashes.

The ruins became a landscape of their own. In the immediate aftermath, photographers documented the devastation in stark, greyscale images—rubble-strewn alleys, scorched Buddhist statuary, the skeletal remains of wooden homes. These photographs circulated first among press agencies, then among artists. Some painters used them as reference. Others painted from memory, layering abstraction over trauma.

One Kobe-based artist, Yasuda Hiroshi, painted a triptych in 1946 titled Ashes Beneath the Hill, blending oil and charcoal in a series of slashing vertical forms. It depicts Mount Rokko in silhouette against a sky thick with gray, but beneath it, jagged shapes—twisted beams, collapsed roof tiles, and anonymous limbs—form a kind of funeral architecture. The piece was never shown publicly during the Occupation but circulated privately among peers.

Kamikaze Aesthetics and Anti-War Art

The war had already altered the aesthetic priorities of many artists. While the state encouraged heroic representations of soldiers and battle scenes, some Kobe-based creators—especially those trained in hanga or oil painting—began to explore more introspective and ambiguous visual vocabularies.

A number of artists began producing what later critics called “kamikaze aesthetics”: spare, haunted works that wrestled with the honor/shame duality of Japan’s wartime ideology. These pieces didn’t mock the fallen pilots or the national mythos, but neither did they glorify them. Instead, they tried to picture the emotional vacuum left behind.

One woodblock print from 1947 by a Kobe artist shows a rising sun, but with its rays folded inward, as if collapsing. The lines are etched deep, almost carved like wounds. Beneath the sun, a plane-shaped silhouette tilts downward, trailing ink instead of flame. It is an image of failed transcendence—neither victory nor pure tragedy, but something more unresolved.

Other artists turned to Christian iconography, particularly crucifixion imagery, to process themes of sacrifice and annihilation. Though Christianity had always existed on the margins in Kobe, its symbols became strangely resonant in this postwar moment. A quiet painting titled At Golgotha by a Catholic convert shows three crosses rendered as power poles, with torn wires stretching into an ochre sky. There is no body depicted—only the suggestion of aftermath.

These works were not welcomed by all. Many conservative critics and officials saw them as defeatist or foreign-influenced. But they gained quiet traction in Kobe’s recovering art circles, especially among younger artists who had come of age during the war.

Postwar Reconstruction and Artist Cooperatives

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Kobe began to rebuild—not just physically, but culturally. The U.S. Occupation brought censorship, but also new freedoms. American materials flooded the market: magazines, paints, brushes, photographic equipment. More importantly, the collapse of state-sponsored exhibitions meant that independent artist groups could form and organize without government oversight.

Kobe responded with a surge of cooperatives and informal collectives, many of which took shape in old storefronts, schoolhouses, or rebuilt merchant homes. One of the first was the Kobe Art Association, re-established in 1948 with support from returning artists and young students. It emphasized non-academic work, promoted cross-media exploration, and often hosted exhibitions that mixed oil painting, photography, calligraphy, and sculpture.

A particularly vibrant hub of activity was located near Motomachi, where a group of artists formed a salon in the back of a rebuilt printing shop. There, painters and printmakers gathered to discuss form and politics, exhibit works in rotating displays, and distribute mimeographed catalogues featuring essays, poems, and sketches.

Among the visual themes that emerged during this time:

- Broken architecture: a frequent motif in both painting and photography.

- Urban solitude: lone figures navigating half-rebuilt streets, depicted in ink or gouache.

- Silent allegory: animals, dolls, or masks used to imply moral or spiritual confusion.

Kobe’s schools also played a key role. The restructured municipal art program expanded dramatically by the early 1950s, with curricula that emphasized both traditional Japanese technique and Western modernist forms. Teachers encouraged students to draw from life, explore abstraction, and address themes of memory and renewal.

By 1955, Kobe had not only rebuilt its physical infrastructure but also reestablished its artistic credibility. Small galleries opened near Sakaemachi and in the new shopping arcades. Public sculpture began to reappear in parks and plazas. Though the scars of war remained visible—and in some cases, deliberately unhealed—the city had reclaimed its place as a space where visual imagination could again flourish.

Gekiga, Gutai, and the Avant-Garde in Kansai

In the decades after World War II, Kobe became a fertile outpost for avant-garde experimentation, driven by its unique position within the broader Kansai cultural sphere. While Tokyo continued to dominate the institutions of Japanese art—academies, national exhibitions, publishing houses—the western cities of Osaka, Kyoto, and Kobe built a creative counterweight: looser, stranger, and more radical. Within this ferment, Kobe stood out not for sheer output, but for its unpredictability. It played host to underground manga pioneers, performance artists, experimental calligraphers, and anti-form sculptors. There was no single school or style. What unified the scene was a shared refusal of Tokyo’s authority and a restless appetite for visual rebellion.

The Rise of Gekiga

One of the most significant developments in postwar Japanese visual culture was the birth of gekiga—literally “dramatic pictures”—a darker, more adult alternative to mainstream manga. Though usually associated with Osaka and Tokyo, gekiga had deep roots in Kobe, where urban grit, portside life, and access to Western pulp media gave the genre a distinctive voice.

Beginning in the late 1950s, Kobe-based artists contributed to a wave of independently published comics that broke from the childlike aesthetics of early manga. Their stories dealt with crime, existential crisis, war memory, and social alienation—often rendered in stark black-and-white panels influenced by noir cinema and European graphic novels.

A pivotal figure in this scene was Masahiko Matsumoto, who frequently published through Osaka’s Gekiga Kōbō circle but lived and worked in Kobe during formative years. His panels employed unusual angles, deep shadows, and minimal dialogue to convey psychological tension. In works like Cigarette Girl, the city itself becomes a character: alleys, docks, and storefronts rendered with precision, silence, and menace.

Kobe’s contribution to gekiga was not just stylistic—it was infrastructural. The city’s proximity to the printing industry in Osaka and its seedy postwar downtown corridors made it an ideal incubator for independent publishing. Artists often met in coffee shops or used rental flats as production hubs. Some early issues were photocopied in Kobe copy shops, then distributed on trains or in corner kiosks. This DIY ethic paralleled similar movements in American zines and European samizdat culture.

By the 1970s, gekiga’s influence was pervasive, extending into mainstream manga, film, and even political poster design. But its early roots in Kobe’s shadows—unofficial, moody, and morally unresolved—left a lasting impression on the city’s artistic psyche.

The Gutai Group’s Legacy

While Kobe was fostering underground comics and visual narrative, something more radical was taking place just up the road. In 1954, in the nearby city of Ashiya (less than 10 miles from Kobe), artist Jirō Yoshihara and a group of young painters and performers founded Gutai, arguably the most important avant-garde art group in postwar Japan. Though based officially in Ashiya, Gutai’s members exhibited frequently in Kobe, and their ethos profoundly influenced the city’s experimental culture.

Gutai rejected traditional notions of painting and sculpture. Instead, it embraced performance, ephemeral materials, and destruction-as-creation. One artist hurled himself through paper screens. Another created a painting by running over it with a motorcycle. Still others painted with their feet, threw bottles of ink at walls, or submerged canvases in rivers. It was not spectacle for its own sake—it was a search for authentic gesture in the ruins of a ruined world.

Kobe, with its history of physical destruction and reconstruction, proved fertile ground for these ideas. The city hosted Gutai exhibitions in repurposed buildings and open-air venues. Critics from Kobe’s newspapers and magazines followed the group closely, often dividing into fierce camps: some derided Gutai as nonsense, others hailed it as the only honest response to a world transformed by mechanized war and capitalist alienation.

One underreported chapter is the influence of Gutai on Kobe’s design schools, where teachers adapted the group’s methods into studio pedagogy. Students were encouraged to use industrial materials—metal, plastic, rubber—as artistic media. Workshops involved collaborative performance, timed destruction, or process-based sculpture. The idea was not to “make art” but to engage matter in action, to reveal the energy of form itself.

Though Gutai dissolved in the early 1970s, its impact on Kobe lingered. Installations, conceptual projects, and action-based works continued to appear in galleries and student exhibitions. Even now, Gutai’s DNA can be found in Kobe’s street performance art and its art-school critique culture, which privileges experimentation over polish.

Kobe’s Fringe Within the Kansai Core

Throughout the postwar period, Kansai was viewed as Japan’s cultural periphery—but that periphery was more radical than the center. Kyoto gave rise to the Mono-ha movement, Osaka nurtured performance art and video art, and Kobe, though smaller, became the testing ground for ideas too raw or regional for Tokyo’s gatekeepers.

One striking aspect of Kobe’s avant-garde was its willingness to blur high and low culture. A 1968 gallery exhibit might pair abstract paintings with hand-lettered punk zines. A sculptor might show alongside a puppeteer. Theater troupes collaborated with printmakers. Calligraphers displayed work on raw plywood.

The blurring extended into venues. Art wasn’t confined to museums. It appeared in jazz bars, train stations, shopping arcades, and even public restrooms. A well-known experimental group in the 1970s staged nighttime performances in abandoned buildings, inviting viewers to follow candlelight through rubble-strewn corridors. The work was part ritual, part art, part civil disobedience.

What Kobe offered was space—physical and psychological—for work that didn’t belong anywhere else. And in that space, a new kind of artist emerged: cross-disciplinary, self-taught, suspicious of institutions, but deeply engaged in form and materials.

This was not rebellion for its own sake. It was the continuation of a century-old Kobe tradition: taking in the foreign, the marginal, the discarded, and forging from them something singular, unsettling, and sometimes sublime.

Art and Earthquake: The 1995 Hanshin-Awaji Disaster and Cultural Response

The morning that changed the city

The earthquake struck at 5:46 a.m. on January 17, 1995, centered near Awaji Island. It measured roughly 6.9–7.3 on modern scales and ripped through Kobe with a violence that felt instantaneous and personal. Streets split, elevated highways pancaked like books, and whole neighborhoods turned into fields of twisted timber and concrete. The human toll was immense: several thousand dead, tens of thousands injured, and hundreds of thousands left homeless—figures later refined by official tallies and international observers.

The catastrophe was a physical fact, but it also became a cultural one. Artists, photographers, choreographers, and craftspersons did not simply document damage; many found themselves called to act as witnesses, memorializers, and civic designers. What followed was not a single “disaster art” movement but a plural set of responses: public monuments, private sketches, community mural projects, documentaries, and a new kind of museum whose purpose was both education and mourning. The region later established the Disaster Reduction and Human Renovation Institution, a museum and learning center devoted to remembering the quake and teaching disaster resilience.

Memory carved into the city

In the months after the quake, photographers were among the first chroniclers. Their black-and-white frames—rubble fields, a child’s sneaker half-buried in ash, a bent railway bridge—were stark evidence and moral summons. Ryuji Miyamoto and other documentary photographers produced work that moved between reportage and elegy; their images entered museum collections and convinced a public wary of being seduced by quick narratives that the scale of loss required sober attention. These photographs circulated in newspapers, international journals, and later in curated shows that insisted viewers confront rather than gloss over what had happened.

Painters and printmakers, working in studios or on the move, adapted different strategies. Some returned to realist depiction: ruined row houses rendered in patient brushwork, empty futons on tatami stained with ash, or the crumpled hulls of ferries. Others moved toward allegory: broken torii gates as metaphors for shaken faith, or solitary figures in vast negative space to signify communal grief. A quieter tendency was to make small, intimate works—studies in pencil or sumi ink meant for exchange among neighbors rather than public exhibition. This private circulation created a grassroots visual archive: sketches pinned to community centers, prints offered at local fundraising bazaars, tiny paintings sold to rebuild studio rent.

Artists as first responders

Artists did practical work as well. Sculptors and designers contributed to rebuilding efforts by repurposing debris into temporary shelters, playgrounds, and devotional objects. Architects and designers organized volunteer teams to create child-friendly spaces in relocation sites; graphic artists produced clear, humane signage for emergency centers; calligraphers and sōsaku hanga printmakers ran workshops teaching displaced people to use image and text to record their stories. Those activities blurred the line between art-as-document and art-as-service, and they had an immediate civic effect: visual culture became part of recovery logistics.

Three recurring interventions help make that point:

- Photographic exhibitions held in temporary halls to locate displaced people and catalog lost property.

- Community mural projects in public housing blocks, turning bare concrete walls into sites of collective memory.

- Design workshops that taught survivors to make banners, simple memorial altars, and printed newsletters.

Each of these practices treated art as a tool for reconstruction, not merely as testimony.

Public memorials, museums, and contested memory

Over the following years, public monuments and institutional spaces established a visible, lasting grammar for how the quake would be remembered. The Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake Memorial Museum (also known as the Disaster Reduction and Human Renovation Institution) opened to preserve artifacts, show film reconstructions, and offer interactive exhibits on preparedness. Its dioramas, film theaters, and preserved wreckage guided visitors through a sequence of shock, rescue, and rebuilding while embedding the event in a civic lesson about vulnerability and duty.

Yet memory was not monolithic. Debates arose over what to preserve and what to remove. Some communities retained damaged structures or roadside fragments as “witness” pieces; others wanted clean replacement and rapid modernization. Artists engaged that debate directly. A number of installations deliberately preserved scars—exposed foundation stones, ringing fragments of highway piers—paired with placards and poetic text. Elsewhere, artists proposed radical acts of re-signification: turning a bent girder into a sculpture that read as both ruin and resilience.

The tension is telling. On one side stood an impulse toward tidy lessons—improve standards, teach preparedness, move on. On the other side, artists insisted on the ambiguity of loss, on the irreducible human cost that statistics cannot smooth over.

A mid-section insight: art remakes civic ritual

One unexpected development was how the quake reshaped civic ritual and its visual accoutrements. Annual memorials, once perfunctory, became occasions for new work: temporary shrines constructed from salvaged wood, lantern festivals organized by neighborhood associations, and collaborative performances by local theater troupes that staged small vignettes of rescue and shared labor. These were not spectacles for tourists; they were acts of civic repair performed in public view, with art serving as a means of social reknitting.

Kobe’s street-level culture absorbed these practices. Murals appeared in shopping arcades and along riverbanks; local fashion designers produced commemorative sashes and pins whose sales funded memorial projects; zines printed first-person accounts alongside sketches and maps. The everyday visual environment thus became a permanent archive, one that recorded how people chose to remember—and how they chose to keep working.

Generational echoes

Artists who were young during the quake have now moved into positions of influence: curators, teachers, municipal planners. Their work often reflects a double awareness—of the event’s immediate trauma and of the long timeframe of reconstruction. Contemporary projects in Kobe frequently combine digital mapping, oral history, and installation so that memory is not static but interactive. Museums teach hands-on disaster preparedness while simultaneously commissioning artists to interpret the event in new media.

In many neighborhoods, artistic practice now sits beside civic duty. Sculptures, murals, and memorial books stand within a civic landscape that insists memory must inform design—of buildings, of streets, of public rituals—so that the past’s lessons are embedded in future safety and beauty.

Urban Aesthetics: Graffiti, Fashion, and Street Culture

Kobe has long been defined by its contradictions: an international port and a provincial town, a gateway to the world and a refuge from it, a city of refined design and raw improvisation. These tensions didn’t vanish with postwar reconstruction. They took on new, expressive forms in the late 20th century—especially on the street. In the alleys of Sannomiya, the underpasses of Nada, and the storefronts of Shin-Nagata, a new kind of visual language emerged. It was not curated by museums or trained in schools. It was made with spray cans, sewing machines, bootleg printers, and instinct. Kobe’s street culture fused local character with global trends, producing an urban aesthetic that felt handmade, stylish, and slightly outside the law.

Streetwear as Kobe Identity

In the 1980s and ’90s, Japanese youth culture exploded with new modes of expression—particularly in fashion. While Tokyo’s Harajuku or Shibuya neighborhoods became famous worldwide, Kobe developed its own distinctive look: more subdued, more mature, but no less deliberate. It drew on the city’s legacy as a cosmopolitan trading port, blending European tailoring with American workwear, filtered through Japanese minimalism and Kansai flair.

Boutiques in Motomachi and Tor Road began selling reworked military jackets, vintage denim, and high-end streetwear before those terms were widely used. Local designers emphasized subtle fabrication over logos, layering wool with canvas, or incorporating traditional Japanese patterns into Western silhouettes. This aesthetic—sometimes called Kobe-kei—was marked by:

- Toned-down color palettes: navy, charcoal, tan.

- Sharp but not flashy cuts: long coats, slim trousers, leather shoes.

- An ethos of quiet detail: hidden buttons, hand-stitched seams, natural fabrics.

Unlike Tokyo’s more theatrical scenes, Kobe fashion was understated but elite. It communicated taste without performance. A whole generation of artists, photographers, and illustrators came of age sketching these street styles, which eventually found their way into lookbooks, indie zines, and even advertising for the city’s train systems.

Kobe’s connection to high-end brands was also unusually strong. The city’s foreign roots had made European labels familiar long before they hit Tokyo. It wasn’t uncommon to see Comme des Garçons next to an old French bakery or an Hermès scarf paired with a student’s thrifted jacket. This blend of elegance and everyday wear shaped Kobe’s visual identity—fashion not as luxury, but as a natural extension of civic pride.

Graffiti and Muralism in Sannomiya and Nada

Kobe’s street walls have always spoken. In the decades following the 1995 earthquake, a new kind of public art emerged—not commissioned, not licensed, but also not purely destructive. Graffiti, stenciling, sticker art, and rogue muralism appeared across the city’s rail corridors, harbor fences, and alley stairwells.

The style was neither New York-style “wildstyle” nor the clean typographic work seen in Tokyo. It was messier, moodier, often monochrome or painted with hardware-store pigments. Kobe’s taggers borrowed from European stencil traditions, Hong Kong’s alley calligraphy, and old gyaru slang, all while adapting it to their own streetscape. A typical wall might include:

- A stencil of a broken ferryboat with text reading “We don’t forget.”

- A paste-up of a faceless salaryman titled “9-to-9 Ghost.”

- A mural of mountain silhouettes tagged with calligraphic slogans about freedom and fatigue.

There were political messages, to be sure—anti-nuclear symbols, anti-conscription graffiti, critiques of gentrification—but more often, these works expressed a kind of quiet, existential frustration. Not revolution, but dislocation. Not anger, but melancholy. In that sense, Kobe’s graffiti was unusually poetic: visual haiku scrawled between vending machines and rain gutters.

The city government responded inconsistently. In some areas, public works crews scrubbed walls weekly. In others, especially near artist-run spaces and cultural corridors, officials quietly tolerated or even encouraged visual interventions. A few once-illegal murals were eventually framed by protective plexiglass, recast as “community voices.” The city’s famed Kobe Biennale later added a graffiti and street art category, legitimizing what had long been unofficial.

One artist, known only as “Maru,” painted dozens of low-profile murals after the earthquake. His work—always featuring a black cat perched on an abandoned object—became a kind of local mythology. Rumors persisted that he was an architect by day. His paintings, often found in difficult-to-reach places, drew local pilgrimages. None were signed, but all shared the same sparse color palette and gentle irony.

The Visual Language of Rebellion

Kobe’s street culture also bled into zines, music, skateboarding, and storefront design. In this city, rebellion didn’t wear a leather jacket—it wore a work apron and made linocuts in a back room. Local zines like SubPort and K-Boy published photo essays of industrial lots, interviews with tattoo artists, and illustrated maps of “unloved places”—abandoned lots, derelict piers, concrete benches under flyovers.

Skaters painted their own boards with brush-style calligraphy. DJs released mixtapes in packaging designed by printmakers. Graphic design students from Kobe Design University produced folded broadsheets that mimicked train schedules but contained poetry and collage. This was not simply DIY culture; it was anti-standard, pro-local, and allergic to polish. It relished the unbranded, the handmade, the impermanent.

Storefronts in older districts like Shinkaichi and Shin-Nagata took on the aesthetics of this movement. Signage was often hand-drawn, packaging irregular, interiors improvised with wood crates and secondhand metal fixtures. This style—a kind of retro-industrial quietism—would later be imitated in Tokyo and abroad as “Japanese minimalism,” though in Kobe it was not minimal by design. It was born from necessity and taste rather than trend.

Street-level art also carried the memory of disaster. Several alley walls still bore post-quake memorial tags well into the 2000s, kept intact by property owners who viewed them as part of the neighborhood’s record. They weren’t marked as “art,” but they remained.

Kobe’s street culture is rarely theatrical. It doesn’t aim to shock, and it resists commodification. What it offers is something harder to pin down: a language of modest rebellion and careful craft, learned not from galleries but from walking the same street enough times to see its rhythm—and then finding a way to answer it.

Kobe Biennale and the New Institutional Landscape

By the early 2000s, Kobe had rebuilt not only its physical infrastructure but also its cultural ambition. The once-scarred port city sought to reposition itself as a center for contemporary creativity—international in outlook, inclusive in participation, but distinctly rooted in place. The most visible sign of this shift was the launch of the Kobe Biennale in 2007, a recurring art event designed to bring experimental visual work into contact with the public. Alongside it, a new institutional landscape emerged: museums, artist residencies, design hubs, and collaborative spaces that redefined how Kobe engaged with art—not as a finished product displayed on white walls, but as an evolving civic dialogue.

What the Biennale Brought

Unlike the better-known Venice Biennale or even Japan’s own Yokohama Triennale, the Kobe Biennale was never conceived as a playground for global art stars. Its guiding principle was different: to integrate contemporary art into the daily life of the port, not merely as decoration or spectacle, but as engagement. It also carried a secondary purpose—to heal and reanimate the city’s civic identity following the trauma of the 1995 earthquake and the longer erosion of port-based industry.

The first Biennale unfolded not only in museums but in shipping containers scattered throughout the Meriken Park waterfront. This was more than a gimmick. The container, as both physical object and metaphor, captured something essential about Kobe: transience, trade, disaster, and reconstruction. Artists were invited to treat the container as installation space, studio, or performance zone. Some filled them with soundscapes. Others turned them into camera obscuras, memory boxes, or micro-laboratories for plant life and found materials.

The visual languages varied widely—from digital projections and abstract sculpture to participatory collage and political cartooning. But what unified the event was its openness. Works were placed along walking routes, visible to joggers, tourists, office workers, and families. The Biennale did not ask its audience to “understand” contemporary art in academic terms. It asked them to encounter it, puzzle over it, walk around it, enter it.

In later iterations, the Biennale expanded to include:

- A container art competition, with public voting.

- A comic illustration section, integrating manga and visual storytelling.

- Musical performances and dance projects that treated the port itself as stage.

For a city that had long balanced refinement and edge, this democratizing gesture mattered. The Biennale gave Kobe an international voice, but on its own terms—wry, restrained, civic-minded, and structurally inventive.

Harborland Installations and Container Art

Kobe’s Harborland district, long a hub for shopping and tourism, became a kind of semi-permanent gallery during the Biennale years. The contrast between commercial storefronts and container installations created friction—and possibility. Some critics accused the event of being too playful, not rigorous enough. Others praised its accessibility and immediacy. But no one denied its impact: public art in Kobe had been resituated from the museum pedestal to the port-side bench.

Notable examples included:

- A container filled with shattered porcelain, rigged to emit sounds when walked upon—inviting visitors to feel discomfort and responsibility with each step.

- A vertical garden growing out of rusted shipping crates, blending ecological awareness with industrial ruin.

- A sound installation using foghorn tones and ship radio chatter, spatialized so that passersby heard ghostly fragments as they moved.

The harbor itself became both backdrop and subject. One installation projected videos of old Kobe—pre-quake, pre-modern, pre-electrified—onto warehouse exteriors. Viewers watched history flicker across concrete at night, surrounded by the same city, remade.

Importantly, the Biennale also inspired smaller satellite exhibitions throughout the city. Independent galleries in Kitano and Shinkaichi launched concurrent shows. Public school art programs created student container pieces in miniature. Coffee shops displayed process sketches and early concepts. In this way, the Biennale was not just an event. It was a rhythm, a temporary pulse that animated the city across layers.

Even after the Biennale’s official conclusion in 2019, its influence lingered. The city began to see containers differently—not as eyesores or refuse, but as vessels for civic possibility. Several were converted into permanent micro-galleries or info booths. Others were adapted for outdoor classrooms or mobile kiosks that brought art to schools and parks.

Contemporary Spaces and Residencies: KIITO, CAP, and Beyond

In parallel with the Biennale, Kobe also developed a new infrastructure of art institutions, shaped by both necessity and imagination. Among the most prominent is KIITO (Design and Creative Center Kobe), housed in a former textile testing laboratory near Sannomiya. Rather than a traditional museum, KIITO operates as a multifunctional creative hub—part gallery, part studio space, part educational venue. Its exhibitions focus on design, architecture, and socially engaged art, often partnering with schools, nonprofits, and municipal planners.

KIITO’s industrial heritage sets the tone: high ceilings, concrete floors, large windows. The building is not polished but preserved, and that material honesty mirrors the city’s own character. Projects housed there have included:

- Design challenges on post-disaster housing.

- Workshops on tactile design for the visually impaired.

- Exhibitions pairing contemporary illustration with traditional crafts.

Another major force is CAP (The Conference on Art and Art Projects), an artist-run collective founded in the early 1990s and based in a repurposed former customs house. CAP functions as a residency and collaborative platform, offering studio space, community exhibitions, and public talks. Its artists come from all disciplines—painters, digital animators, ceramicists, experimental musicians—and their projects often blur the line between gallery work and social experiment.

CAP’s strength lies in its independence. It does not pursue prestige. It fosters process, play, and long-term engagement. Some of Kobe’s most influential younger artists began in CAP studios, exhibiting their first pieces in rooms barely converted from offices. Others have returned to teach, bringing international experience back to the local scene.

Elsewhere in the city, smaller institutions have followed suit: photography labs in Nagata, print studios in Nada, alternative publishing ventures in Tarumi. Each bears the mark of Kobe’s sensibility—modest in scale, serious in purpose, and quietly daring.

The result is a city where institutional support does not mean rigid bureaucracy but flexible, artist-driven structure. This isn’t a city that rushes toward trend or spectacle. It cultivates longevity, trust, and material intelligence.

Memory, Maritime Light, and the Future of Kobe Art

Kobe has never been a cultural capital in the way Tokyo or Kyoto are. It has no imperial palaces, no ancient academies, no national museums bearing its name. What it has instead is harder to name and easier to feel: a tone, a rhythm, a sense of light falling through sea air. This final quality—indefinable but unmistakable—has shaped its art for generations. As the city moves deeper into the 21st century, the future of Kobe’s visual culture depends not on chasing recognition, but on deepening its distinctive conversation between memory, place, and innovation.

Art in a Seismic City

There is no forgetting what Kobe has endured. Earthquakes, war, firebombing, and economic displacement have all left their mark—not only in infrastructure but in imagination. Many cities bury their trauma. Kobe’s artists preserve it. They do so not through grand gestures, but through materials, symbols, and the decision to keep certain absences visible.

This awareness of fragility has given Kobe art a particular kind of poise: not hesitant, but careful. It avoids bombast. Even when working in experimental modes—video, installation, street art—the city’s artists tend to root their work in tangible things: stone, wood, paper, metal, weathered surfaces. The port’s influence remains constant. Light off the bay, rusted steel from cranes, the arc of bridges, the curve of mountain paths—these elements recur in photography, sculpture, and contemporary design.

A younger generation of artists, many born after the 1995 quake, have absorbed this aesthetic almost unconsciously. Their work often features subtle mapping, eroded textures, or patterns inspired by urban sediment. One recent series of digital prints recreated Kobe’s city grid by layering data from lost postal routes, train stops, and vanished temples. Another project involved filming the same corner of Motomachi over twelve months, capturing shifts in pedestrian traffic, seasonal color, and ambient sound.

In a seismic city, impermanence is not a theory. It is a daily reality. Kobe’s artists seem to accept this—not mournfully, but as a compositional fact.

Artists as Civic Voices

One of the most promising developments in recent years has been the emergence of artists who work not only within the gallery system but within city planning, education, and environmental restoration. These artists are not activists in the Western mold, nor are they state-appointed muralists. They occupy a middle ground where aesthetics, utility, and memory converge.

A few key areas where this convergence is most visible:

- Environmental design: Artists collaborating with marine biologists to restore coastal zones with reef-like sculptures.

- Urban revitalization: Designers reimagining abandoned shopping arcades as art walkways, complete with interactive light installations and modular pop-up stalls.

- Heritage preservation: Photographers documenting endangered architecture in Kobe’s prewar foreign districts—not as nostalgia, but as living material culture.

These civic-minded projects reflect Kobe’s longstanding blend of modesty and discipline. There is no grandstanding. Even politically charged work tends to speak in metaphor, layering symbolism over critique. A sculptor might repurpose concrete rubble into seating for public parks. A calligrapher might use saltwater ink to write prayers for endangered harbors. These are quiet acts of belonging—gestures of maintenance rather than disruption.

This mode of civic art also dovetails with Japan’s broader turn toward regional revitalization. As rural and port cities face declining populations, Kobe’s artists have increasingly partnered with local governments to produce place-based projects that attract tourism, foster pride, and preserve memory. Unlike flashier urban art projects in Tokyo, these efforts move slowly, and they tend to prioritize materials already at hand—found wood, archival images, oral histories, and public participation.

The artist is not a celebrity here. He or she is a neighbor.

Kobe’s Next Generation

Kobe’s future in the arts will likely belong not to any single movement but to a network of small-scale practices—each rooted in personal experience, local tradition, and a certain aesthetic reserve. Young artists are less concerned with fitting into global art markets and more focused on honing their own voice within the city’s particular ecosystem.

Several new tendencies are emerging:

- Digital-hybrid forms, where code, sound, and image are layered with analog materials.

- Immigrant voices, particularly from Korean, Chinese, and Filipino communities, who bring new idioms to traditional formats.

- Cross-generational workshops, where emerging artists collaborate with craftspeople in textile, ceramics, and woodwork.

These trends don’t replace Kobe’s past—they extend it. Artists are still sketching Mount Rokko, still photographing old ferries, still making prints of lantern festivals or disused factories. But they’re also designing apps that tell ghost stories along walking paths, building AR filters that reconstruct demolished neighborhoods, and creating digital scrolls that scroll sideways across LED-lit tunnels.

The spirit of Kobe’s art is not to chase trend or reject history. It is to fold the new into the old, and to make that seam the site of meaning. There is still room for abstraction, provocation, irony. But what endures most in Kobe’s visual language is an ethic of care: for materials, for memory, and for the city itself.

The future is not without risk. Rising real estate prices, shrinking public budgets, and the fragility of local arts education remain serious challenges. But Kobe has always worked under constraint. And constraint, as its best artists know, is not a burden—it’s a form.

If Kobe’s art has one defining trait, it is this: it does not demand attention. It rewards it.