The year 1896 felt older than its number. Europe stood at the edge of a new century, and the arts trembled with a restless, electrical anticipation. Painters, poets, and sculptors sensed that the familiar shapes of the nineteenth century—its realism, its romantic faith in progress—were beginning to crumble. Gaslight had given way to electricity. Trains ran faster, presses printed brighter, and artists were learning that color itself could become a kind of philosophy.

The fever of the fin de siècle

In Paris, the air shimmered with invention. The Exposition Internationale d’Art was still three years away, yet cafés and galleries buzzed with talk of art as spectacle, art as confession, art as dream. The Salon had not lost its authority, but its grandeur felt exhausted. Dealers like Durand-Ruel and Ambroise Vollard were building new empires by trusting artists the establishment distrusted: Monet, Cézanne, Gauguin, Lautrec. For the first time, a generation of painters lived not by patronage but by experiment.

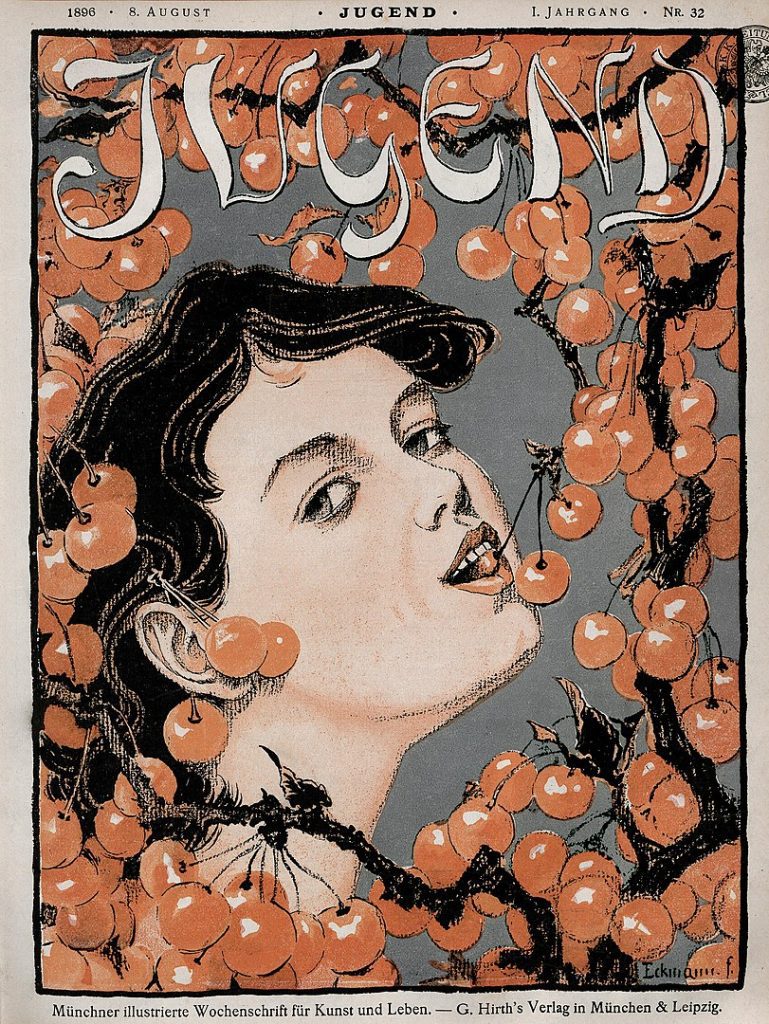

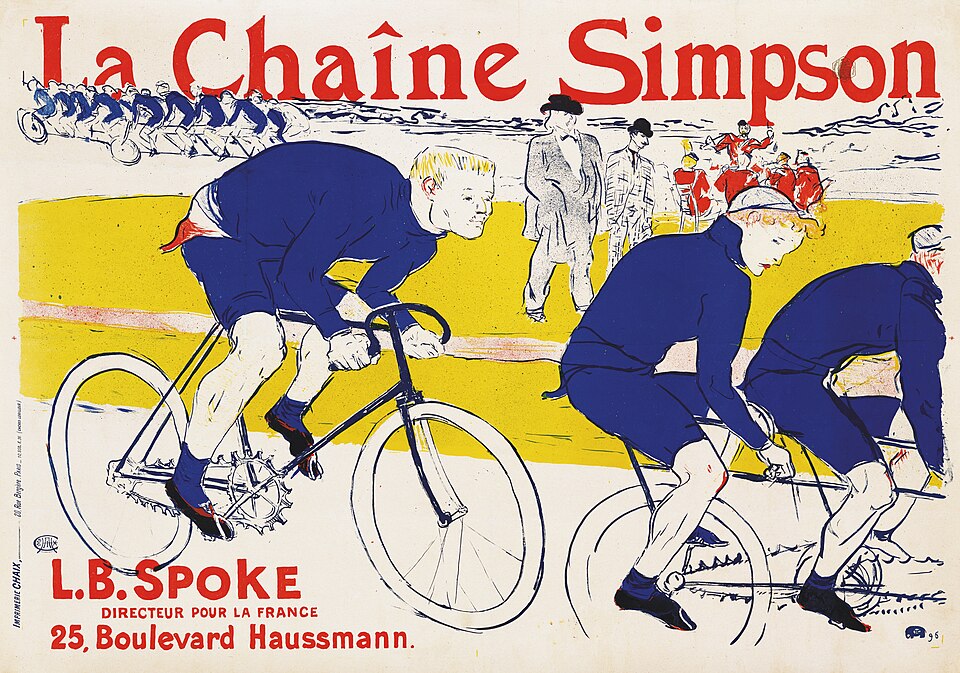

The streets themselves were turning into exhibitions. The poster, multiplied by the new color lithography presses, changed how the public encountered beauty. Alphonse Mucha’s swirling figures in shop windows were as familiar as the faces of actresses. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s flattened silhouettes danced along the boulevards like heralds of a modern age that spoke directly to the crowd. The idea that fine art belonged to the elite was collapsing into the noise of public life.

A continent in motion

Across Europe, nations pulsed with industry and anxiety. Britain mourned the slow fading of its Pre-Raphaelite glow; Germany’s painters wrestled with Romanticism’s ghost; Scandinavia felt the chill of introspection. In Vienna, Secessionist ideas were germinating beneath the polished surface of academic art. Even those still painting traditional landscapes felt the tug of the new. The old light of Impressionism—once a radical act—was already being dissected, reassembled, and challenged by Symbolism, Neo-Impressionism, and the decorative impulse of Art Nouveau.

Three artistic ambitions began to converge:

- To capture the flicker of sensation before thought.

- To grant the everyday world an aura of myth.

- To fuse beauty with design in every corner of life.

That convergence gave 1896 its peculiar intensity: the sense that art was both dying and being reborn.

Modernity’s pulse

In London, the death of William Morris that October marked more than the passing of a craftsman. It felt like the closing of a moral age. His dream of uniting art and labor, of restoring beauty to use, had spread across continents, even as industry’s machinery roared louder. Yet while his idealism waned, the aesthetic he had inspired flowered into the exuberance of the Art Nouveau style—its tendrils climbing iron gates, its curves whispering on wallpaper and glass. Architecture, too, began to shimmer with organic rhythm, as if buildings themselves were learning to breathe.

Paris remained the magnetic pole. The poet’s melancholy had found its counterpart in the painter’s palette: Odilon Redon turning myth into dream, Gustave Moreau guiding his students toward visions rather than narratives, and Pierre Bonnard finding holiness in the humblest domestic moments. They shared no doctrine, yet each rejected mere imitation. They wanted art to feel like thought—to glow with the interior weather of consciousness.

Across the oceans

North America was listening. In Boston, the painter James McNeill Whistler lectured on “art for art’s sake,” his silver harmonies finding kinship with European Symbolists. In New York, the young Robert Henri and his circle were beginning to question genteel painting and to seek the vigor of the modern city. Farther south, Australian and New Zealand painters were translating European techniques into brighter light—Tom Roberts’ and Arthur Streeton’s work transforming bush landscapes into scenes of national imagination. Their brushes seemed to record a civilization arriving at self-awareness through color.

Japan, meanwhile, entered the conversation not as an imitator but as a quiet provocateur. The Meiji period’s export of woodblock prints had reshaped European composition; by 1896, that influence looped back. The Tokyo Fine Arts School, founded only a decade earlier, had become a crucible for reconciling native and Western traditions. Aesthetic exchange was no longer colonial spectacle—it had become artistic necessity.

An age aware of its endings

Everywhere, the arts carried a strange dual awareness: that they were witnessing an ending and inventing a beginning. Painters spoke of “decadence,” but what they meant was exhaustion with the old order. The Impressionist revolution had freed vision from realism, and now the Symbolists sought to free vision from the external world altogether. The public, half-scandalized and half-enchanted, began to accept that art might no longer describe life but imagine its inner logic.

In the cafes of Montmartre and the studios of Munich, talk circled around a new question: What could art mean when beauty no longer sufficed? The answer, glimpsed in 1896, would unfold over the next decade in movements that dissolved form, line, and even the idea of representation itself. But for now, the year stood poised—bright, fragile, and saturated with foreknowledge.

Art had learned to dream in color, and the twentieth century was already beginning to wake.

Chapter 2: The Last Flames of Impressionism

The light that once revolutionized painting was beginning to flicker. By 1896, Impressionism—once derided as incoherent, radical, and unfinished—had become a familiar language. Yet its founding masters were far from complacent. They had entered a late style that deepened their original discoveries into something meditative, even obsessive. The Impressionist search for transient sensation had evolved into a confrontation with permanence: how to paint not just the changing world, but the endurance of perception itself.

Monet’s cathedrals and the weight of time

Claude Monet’s Rouen Cathedral series, begun in the early 1890s and exhibited through 1895–1896, stood as a monumental experiment in seeing. Each canvas—capturing the façade at dawn, midday, and twilight—transformed stone into vapor, substance into atmosphere. But behind the famous shimmer of color was a new psychological density. Monet’s eye no longer sought merely the effect of light; it pursued the act of vision itself. The cathedral, immovable and ancient, became a stage upon which light enacted its fleeting dramas. By isolating a single motif and submitting to its temporal moods, Monet transformed the Impressionist method into a metaphysical discipline.

Visitors to Durand-Ruel’s gallery that year were startled by the extremity of these works. Up close, they dissolved into nearly abstract mosaics of pigment. Stepping back, they coalesced into architecture touched by divine radiance. The effect was neither realism nor dream but something between—a visual prayer to transience. Monet had found, within the fleeting, a strange endurance.

The quiet radicalism of Pissarro

Camille Pissarro, the elder of the group, had returned from his Neo-Impressionist phase and rediscovered the freedom of gesture. His village scenes of 1896, painted around Éragny, revealed a painter content to explore modest motifs with renewed tenderness. While Monet reached for monumentality, Pissarro turned to intimacy—the everyday rhythms of peasants, orchards, and winding lanes. His brush, once dissected into pointillist dots, now breathed again. He had learned from Seurat’s precision but abandoned its discipline in favor of something warmer, more humane.

In these late works, light becomes moral rather than optical: a language of empathy. The Impressionist credo—painting what one sees—had matured into painting how one feels in seeing. That subtle shift would guide the next generation, from Bonnard to Matisse.

The vanishing landscape

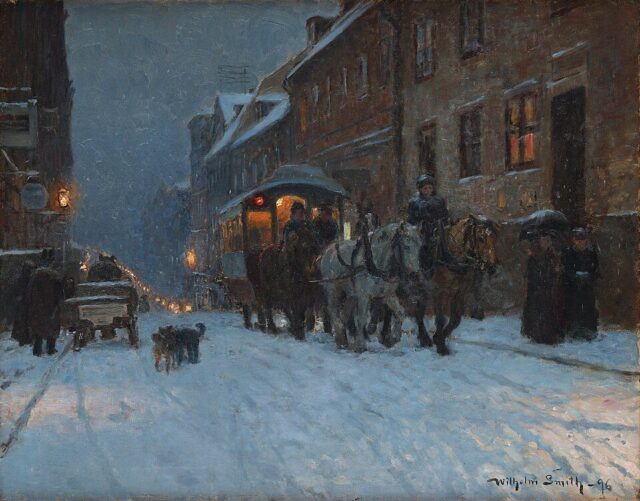

Elsewhere, Impressionism’s influence rippled outward in unexpected directions. In Britain, Philip Wilson Steer and Walter Sickert absorbed its lessons but colored them with English melancholy. In Scandinavia, Peder Severin Krøyer’s beach scenes in Skagen shimmered with northern light—a cooler register of the same obsession. Even in America, painters like Childe Hassam translated Parisian brilliance into the hard clarity of Manhattan and Boston streets.

Yet beneath this proliferation lay an unease. The pastoral world Impressionism celebrated was disappearing under industry’s advance. Railways cut through meadows; chimneys replaced church spires. Painters who once escaped the city to find purity in nature now discovered that nature itself had changed. The Impressionist ideal of spontaneous communion with the visible world seemed increasingly nostalgic—a vision of a Europe already lost.

Three symptoms of that nostalgia marked 1896:

- Landscapes turning inward, suffused with memory rather than observation.

- Urban scenes painted with wistful detachment, as if glimpsed through smoke.

- Portraits rendered in atmospheric haze, dissolving individuality into light.

It was as though Impressionism, in perfecting its vision, had painted itself to the edge of extinction.

Cézanne’s geometry and the new discipline

Meanwhile, Paul Cézanne’s disciplined isolation in Aix-en-Provence had begun to attract attention. By 1896, Vollard was exhibiting his still lifes and landscapes—works that retained the Impressionist palette but rejected its spontaneity. Cézanne sought order within perception, the structure beneath flux. His famous remark—“I want to make of Impressionism something solid and lasting like the art in museums”—encapsulated the pivot underway. The free, shimmering brushstroke was giving way to the measured plane, the geometry of things as they are understood rather than merely seen.

Cézanne’s late fruit still lifes, with their tilting tables and quiet weight, were revelations to younger artists. They suggested that the way forward was not through further dissolution but through reconstruction. In the play of those humble apples lay the seeds of Cubism, though no one yet could name it.

A quiet fading, a lasting glow

By the end of 1896, critics were already writing of Impressionism in the past tense. The term “post-Impressionist” had not yet been coined, but the transition was unmistakable. The old group—Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley—had retreated into their private obsessions. Their public quarrels had softened into reminiscence. Yet the movement’s light did not go out. It diffused through Europe and across oceans, altering every brush that touched color thereafter.

What made those final years so poignant was their serenity. The fever of rebellion had cooled, replaced by quiet mastery. The Impressionists had begun by defying tradition; they ended by creating one. Their paintings no longer shocked—they consoled, haunted, and taught. What they left behind in 1896 was not merely a style but a new kind of perception: one that admitted the uncertainty of vision as the truest image of the modern mind.

The flames of Impressionism did not die that year. They simply changed hue—burning less brightly, perhaps, but deeper, steadier, and closer to the heart.

Chapter 3: Symbolism Ascendant

In 1896, the visible world no longer satisfied the ambitions of painters. After decades of chasing light across fields and facades, artists turned inward—to the psyche, to myth, to the dream. This was the great shift of the fin de siècle: from perception to imagination, from observation to revelation. Symbolism, once a poetic tendency, had become a visual language. It was not a school but a state of mind, binding artists across nations by their hunger for meaning deeper than sight could provide.

From the studio to the inner world

Paris was again the crucible. In Gustave Moreau’s studio at the École des Beaux-Arts, a generation of students learned that art need not imitate nature to be true. Moreau—whose jeweled canvases shimmered with saints, sphinxes, and visions of ecstatic torment—taught his pupils to revere mystery. He urged them to “paint not life as it appears, but life as it dreams itself.” Among those students were Henri Matisse, Georges Rouault, and Albert Marquet—names that would soon carry Symbolist introspection into modernist form.

But in 1896, the elder master still reigned. His mythological scenes, suffused with erotic melancholy, were relics of Romanticism yet alive with modern anxiety. The gods and heroes he painted seemed to know they were fading; they looked not at the viewer, but inward, as though remembering their own vanishing.

Odilon Redon and the birth of color from darkness

No artist embodied Symbolism’s transformation better than Odilon Redon. After decades of charcoal “noirs”—those haunting, dreamlike visions of floating heads, eyes, and spectral hybrids—he turned, around 1895–1896, to color with almost religious fervor. The Cyclops (1896) stands as his emblem of awakening: a monstrous being leaning gently over the sleeping nymph Galatea, rendered in pastel tones so tender they dissolve the grotesque into pity.

In that strange, luminous scene, the monster is not a symbol of terror but of wonder. Redon’s art does not interpret myth; it re-dreams it. His palette, suddenly radiant after years of shadow, feels like a moral event—the discovery that the imagination’s depths are not only dark but also dazzling. Where Monet sought light in nature, Redon found it in the mind.

The contagion of the invisible

Symbolism was never unified by subject or technique. What joined its practitioners was conviction that art should suggest rather than declare. In Brussels, Fernand Khnopff painted ethereal figures suspended between thought and silence. In Switzerland, Arnold Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead continued to haunt imaginations across Europe, reprinted and recopied endlessly. In Italy, Giovanni Segantini carried Symbolism into the mountains, turning the Alpine light into a medium for transcendence.

By 1896, the Symbolist ethos had seeped into every art form:

- In painting, it turned color into emotion rather than description.

- In sculpture, it blurred the line between body and spirit.

- In design, it lent ornament the gravity of myth.

The movement’s power lay in suggestion—the ability to evoke ideas the mind could not name. It was less about stories than states of being.

The decorative as devotion

Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, working within the circle known as the Nabis, took Symbolist feeling into the domestic realm. Their interiors of 1896—rooms suffused with amber light, figures half-absorbed into wallpaper—transformed bourgeois calm into private mystery. Vuillard’s The Seamstress (1896) seems at first a simple scene of work, but the muted tones and shallow space render it meditative. The woman’s concentration becomes a form of prayer; the room itself hums with invisible presence.

For the Nabis, the decorative was not superficial—it was spiritual. They believed pattern and rhythm could express what words could not: the quiet pulse of existence. In their hands, Symbolism shed its academic solemnity and entered ordinary life, imbuing curtains, tiles, and prints with emotional resonance. The domestic became a sanctuary for revelation.

A Europe dreaming aloud

Beyond France, the Symbolist temperament found local dialects. In Britain, the languor of the Pre-Raphaelites deepened into the mystical sensuality of Edward Burne-Jones and the visionary allegories of George Frederic Watts. In Russia, Mikhail Vrubel’s sinuous demons hinted at an inner apocalypse. Even in America, artists such as Elihu Vedder and Kenyon Cox adapted Symbolist imagery to moral allegory, bridging European refinement with New World earnestness.

The movement’s reach testified to a shared spiritual crisis. Science had transformed the material world; religion no longer offered certainty; philosophy dissolved into abstraction. Symbolism filled the gap, proposing that art could become the new vessel of faith—not dogmatic, but intuitive. It spoke to the yearning for unity in an age of fragmentation.

The paradox of the unseen

Yet Symbolism’s triumph in 1896 also marked its limit. Its greatest virtue—ambiguity—was its greatest weakness. The more it sought the ineffable, the closer it came to silence. Younger artists, soon to be called Fauves, admired the color but rejected the mysticism. Others, like Edvard Munch, retained the mood but replaced myth with psychology. The dream was turning darker, more inward, more modern.

Still, for one shining moment, Symbolism offered Europe a mirror for its soul. It taught artists that imagination was not escape but inquiry. The visible world, they realized, was only a thin crust over deeper fires. And in that discovery, the seeds of modern art were sown.

The year 1896 belonged to the dreamers—those who saw that the unseen was the only reality worth painting.

Chapter 4: Toulouse-Lautrec and the Modern Poster

In 1896, the streets of Paris were alive with color. Not from nature, not from stained glass, but from the new art that hung on every wall and corner kiosk: the poster. Where once the city’s façades had been bare stone, they now fluttered with the bold, flat shapes of modern design. Lithography had made mass printing swift and cheap, but it took an artist’s hand—Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s above all—to turn commerce into art.

A new kind of spectacle

At night, the boulevards glowed with electric lamps. The cabarets of Montmartre—Moulin Rouge, Divan Japonais, Ambassadeurs—promised escape from bourgeois respectability, and Lautrec turned their energy into a visual language that no painter before him had attempted. His posters did not imitate life on stage; they distilled it. Figures were reduced to silhouettes, gestures to rhythm, faces to profiles lit by gaslight and cigarette smoke. It was not reality he captured but its pulse.

In La Passagère du 54 – Promenade en Yacht (1896), a woman reclines on a deck chair, her hat tilted just so, her dress a play of curves and negative space. The lines are economical, the color fields few. Yet the image radiates sophistication, wit, and a faint melancholy. Lautrec had discovered that omission could be as expressive as detail. What mattered was not likeness but attitude—the modern self as a flicker of style.

The democratization of beauty

For centuries, art had belonged to salons and collectors. Now it belonged to the passerby. The poster fused high and low culture, erasing the old boundaries between fine art and advertisement. Artists like Jules Chéret had pioneered the form, but Lautrec gave it a psychological edge. His subjects—dancers, singers, lovers—were not idealized. They were human, flawed, and magnetic. The poster became a mirror of urban life, vibrant and unsentimental.

Three qualities defined this new visual order:

- Clarity: images that could seize the eye in an instant.

- Rhythm: compositions structured like music, with repeating forms and accents.

- Personality: every curve and color carrying the stamp of an individual hand.

What had begun as commercial decoration evolved into an emblem of modernity itself. Collectors tore posters from walls; galleries began exhibiting them as art objects. The world was learning to see beauty in reproduction.

The culture of immediacy

Paris in the 1890s thrived on speed. Newspapers multiplied, cafés overflowed, and the public appetite for novelty seemed endless. Lautrec’s posters fit this tempo perfectly. Their bold outlines and compressed compositions echoed the pace of city life. Even those who never entered a theater knew its atmosphere through his images. The cabaret ceased to be a place—it became a mood.

In 1896, the Salon des Cent and Revue Blanche exhibitions celebrated this new aesthetic of immediacy. Posters by Lautrec, Chéret, Steinlen, and Alphonse Mucha filled the walls, their flat colors forming a chorus of modern design. Mucha’s Job Cigarettes poster, also from that year, offered a more decorative sensuality—flowing hair, smoke curling into arabesques. Where Lautrec’s world was sharp-edged and ironic, Mucha’s was ornate and dreamlike. Together, they defined the two poles of the new age: the graphic and the ornamental, the urban and the ideal.

Beyond the café walls

The poster’s success transformed other media. Painters began borrowing its clarity; designers absorbed its boldness. Even stage sets and interior decoration echoed its silhouettes. The influence spread beyond France—into Britain’s art journals, Vienna’s emerging Secession, and America’s early magazine covers. In 1896, when Toulouse-Lautrec’s May Belfort and May Milton posters appeared in London, they startled the English public with their candor. The modern city, once condemned as vulgar, had become a subject worthy of beauty.

In this new visual economy, fame itself changed meaning. Performers were no longer immortalized by portrait painters but by lithographers. The poster turned anonymity into celebrity. It announced not only an event but a sensibility—the allure of being seen.

The fragile triumph

Lautrec’s career, by then, carried the shadow of fragility. His health was failing; his nights were long and erratic. Yet 1896 represented his fullest command of the medium. Each poster was a synthesis of painterly intuition and graphic precision, art stripped to its essentials. Beneath their gaiety lingered compassion—for dancers who performed until dawn, for drinkers who stared too long into the light. In that empathy lay his greatness.

The modern poster was not merely decoration. It was a portrait of the new human condition: fleeting, theatrical, self-conscious, and vividly alive for an instant before vanishing into print. Lautrec’s genius was to see that transience as beauty.

When the wind tore his posters from the Paris walls, they fluttered down like leaves of a changing age. Art had escaped the museum and entered the street—and there, amid noise and laughter, it found its modern voice.

Chapter 5: The Nabis and the Sacred Domestic

By 1896, a quiet revolution was taking place behind closed doors. In the modest Paris apartments of Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, Maurice Denis, and Paul Sérusier, art turned inward—not to the dreamscapes of Symbolism, but to the intimate corners of daily life. These young painters, calling themselves les Nabis (from the Hebrew word for “prophet”), believed the ordinary could be made luminous through design. Their revelation was not grand or cosmic; it whispered from teacups, wallpaper, and lamplight.

A new kind of mysticism

In an age enthralled by spectacle, the Nabis sought stillness. They rejected the illusionism of academic painting and even the spontaneity of Impressionism, replacing it with deliberate pattern and rhythm. “Remember that a picture, before being a battle horse or a nude woman,” Maurice Denis wrote in 1890, “is essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order.” By 1896, this statement had become the quiet manifesto of modern painting.

Their works from that year—Vuillard’s The Seamstress, Bonnard’s Woman with a Dog, Denis’s April—look domestic, even shy. Yet behind the calm lies a radical idea: that the spiritual resides not in distant cathedrals but in the arrangement of color and form. The home itself became a site of revelation.

Vuillard and the art of still air

Édouard Vuillard’s interiors seem to breathe in slow rhythm, like rooms that remember. The Seamstress (1896) shows a woman absorbed in her work, her figure half-dissolved into patterned walls and drapery. The light is subdued; the palette, hushed. Yet the painting glows with inward life. Vuillard does not describe objects so much as the atmosphere of attention—the quiet concentration that sanctifies simple labor. Every fold of fabric, every shadowed corner, participates in a mood of reverent suspension.

In these paintings, nothing happens, and everything happens. They are about the sanctity of being present, the holiness of repetition. Vuillard’s brush turns the smallest gesture into a meditation on existence itself. The domestic, once considered trivial, becomes a threshold to the infinite.

Bonnard’s gentle disorder

Pierre Bonnard, by contrast, saw intimacy as a dance of color and light. His works of 1896 capture fleeting, unguarded moments: a woman combing her hair, a dog stretching beneath a table, a child glancing out a window. He called himself a “painter of happiness,” yet his happiness was never naïve. It was tempered by tenderness—the knowledge that every moment vanishes as it is seen.

Bonnard’s sense of composition was instinctive and musical. He flattened space, dissolved edges, and let color guide structure. In doing so, he anticipated much of modernism’s abstraction. But his art remained anchored in affection. Even his distortions feel warm, like the way memory bends when it tries to hold on too long.

Three features distinguish his 1896 works:

- Color as sensation, not description.

- Flattened space, turning rooms into patterns of rhythm and tone.

- The affectionate gaze, transforming observation into intimacy.

For Bonnard, beauty was not found in grand subjects but in the daily choreography of life—small gestures that, when painted with devotion, became eternal.

The decorative as a moral principle

The Nabis’ emphasis on design was not a retreat from seriousness; it was a moral stance. They sought to reunite art and life, dissolving the hierarchy that separated the fine from the applied. Their paintings often shared motifs with textiles, screens, and book illustrations. Color harmonies flowed from wall to canvas and back again. This unity of surface and spirit reflected a new idea: that beauty, properly understood, was ethical—an ordering of the world that mirrored inner balance.

Maurice Denis, the group’s philosopher, pursued this idea most explicitly. His religious imagery—Madonnas amid stylized gardens, angels framed by decorative borders—transposed the sacred into ornament. To him, the divine was not remote but patterned into existence itself. The decorative, properly handled, became prayer.

From private to universal

Though the Nabis moved in the world of bourgeois interiors, their ambitions were not provincial. They believed that by painting the private sphere truthfully, they could restore a sense of meaning to modern life. In a society increasingly fractured by technology and speed, their art offered repose. It spoke softly but persistently: that silence, repetition, and care were still forms of knowledge.

The intimacy of their subject matter carried profound implications. By treating the domestic as worthy of reverence, they prepared the ground for later artists who would explore the psychological and formal power of interior space—from Matisse’s radiant rooms to the modernist abstractions of pattern and rhythm. The Nabis’ modesty concealed their radicalism.

The end of secrecy

By 1896, the group was nearing its dissolution. Each member followed a personal vision: Denis toward overt religiosity, Bonnard and Vuillard toward sensual modernism, Sérusier toward mystic geometry. Yet their brief unity had altered the course of art. They proved that modern painting could be both decorative and profound, sensual and contemplative.

What they shared, finally, was faith—in color, in design, in the capacity of quiet things to reveal the invisible. Their art did not shout. It glowed.

As the century drew to its end, the Nabis’ rooms seemed to close gently behind them. Inside, the lamps still burned; the walls still whispered with pattern. The sacred had found a new address: the ordinary home.

Chapter 6: Art Nouveau and the Decorative Revolution

In 1896, beauty began to curve. The straight lines of classicism and the rigid grids of industrial design gave way to whiplash spirals, floral tendrils, and the supple logic of growth. This was the year Art Nouveau became not a curiosity but a movement—an aesthetic that sought to bind every aspect of life into a single organism of form and rhythm. Its ambition was nothing less than total: to make art the skin of modern civilization.

A new elegance for a restless age

Europe was changing faster than any generation before it. Telegraph wires laced the skies, factories hummed, and electric light erased the night. Amid this acceleration, Art Nouveau offered a counterpoise—a language of renewal drawn from nature’s flowing order. The style emerged almost simultaneously in multiple cities: Paris, Brussels, Vienna, Glasgow, Prague. Each had its own dialect, but all shared a belief that beauty should be organic, continuous, and alive.

In Paris, 1896 marked the ascendancy of Alphonse Mucha. His Job Cigarettes poster, with its languid female figure framed by looping smoke and golden arabesques, appeared that year across the city. It became an emblem of the age: sensual yet disciplined, decorative yet spiritual. Mucha’s line—graceful, decisive, endlessly curving—captured the optimism of a generation that believed design could heal the fragmentation of modern life.

The unity of the arts

The Art Nouveau ideal rested on a single principle: that all the arts should converge. Architecture, furniture, typography, glasswork, and painting were not separate crafts but facets of one creative impulse. The artist was to be both designer and philosopher, orchestrating a harmony between object and environment. In this vision, even a door handle or a teacup could express a worldview.

In Brussels, Victor Horta’s Hôtel van Eetvelde, completed in 1895 and celebrated through 1896, embodied that synthesis. Its iron staircases unfurled like vines; its stained glass glowed like mineral veins. Horta treated steel not as an industrial material but as a medium of grace. The building felt less constructed than grown. Such works declared that modernity need not be mechanical—it could be botanical, fluid, humane.

Three tendencies crystallized in that year’s Art Nouveau:

- Nature as geometry, transforming organic curves into structural logic.

- Craft as philosophy, restoring dignity to materials.

- Total design, in which architecture, furniture, and ornament spoke a single visual language.

From print to architecture

The decorative impulse leapt easily from lithograph to building. Artists trained in poster design found themselves designing stained glass, furniture, and jewelry. The same sinuous line that framed Mucha’s women traced across the façades of Hector Guimard’s Parisian townhouses. By the time Guimard designed the first Métro entrances (concept sketches were already circulating in 1896), the Art Nouveau curve had become a civic symbol—the signature of modern elegance.

This cross-pollination between disciplines reflected a deeper conviction: that beauty must be public. The poster had democratized imagery; now architecture sought to democratize grace. A doorway or a balcony railing could lift the spirit of a passerby. The decorative was no longer mere embellishment—it was social purpose made visible.

Vienna and Glasgow: the geometry of restraint

Even as Art Nouveau reached its luxuriant peak in France and Belgium, parallel movements arose that tempered its sensuality with discipline. In Vienna, architects like Otto Wagner and the young Josef Hoffmann sought to simplify ornament into structure. Their early designs of 1896 already hinted at the Secession’s coming austerity: linear, measured, almost musical. In Glasgow, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Margaret Macdonald were exploring similar principles, blending Celtic motifs with Japanese restraint.

What united these variations was their faith in synthesis. Whether opulent or austere, they saw no divide between fine and applied art. Every element—line, color, material—was an act of moral order.

Japan and the circular return

Japan’s influence, so vital to Impressionism and Symbolism, also shaped Art Nouveau’s fluid aesthetic. The asymmetry of Japanese prints, their empty spaces and flowing contours, had taught Europe to see composition as movement rather than symmetry. By 1896, the exchange had become reciprocal: Japanese designers studying in Europe adapted Western materials to traditional sensibilities, producing a quiet parallel modernity. The global dialogue of ornament deepened, erasing the line between East and West.

Beauty against chaos

The Art Nouveau ideal was more than style; it was resistance. Amid industrial standardization, it affirmed individuality. Against mechanized repetition, it offered organic continuity. Its designers believed that beauty could redeem the modern world from its own machinery. Even the humblest object could, through care of design, restore a sense of order and purpose.

By the end of 1896, critics were already debating whether the movement’s sensuality risked excess. Some found its curves decadent, its ornament feverish. Yet behind those accusations lay recognition of its power. Art Nouveau had achieved what few movements ever do: it altered not only how people made art, but how they imagined life should look.

Its triumph was brief but incandescent. Within a decade, geometry would harden into abstraction, and ornament would fall under attack. But in that moment—1896, when a poster, a railing, and a perfume label could share the same grace—Europe seemed to glimpse a new unity between the handmade and the modern.

The world, for a fleeting instant, flowed like a line of smoke in Mucha’s poster: fragile, rhythmic, and endlessly alive.

Chapter 7: The Death of William Morris and the Legacy of the Arts & Crafts Movement

When William Morris died in October 1896, the news carried a symbolic weight beyond the loss of one man. To those who had followed his restless career—as poet, designer, craftsman, socialist, and publisher—his passing marked the close of an age in which beauty had been treated as a moral duty. Morris had spent his life insisting that art was not a luxury but a necessity of honest labor. His death came at a moment when the world he had sought to redeem was embracing the machine.

The last idealist of craftsmanship

Morris’s career embodied the 19th century’s most enduring paradox: the desire to reconcile art with industry. In his workshops at Merton Abbey, he revived medieval weaving, dyeing, and printing methods, believing that the touch of the craftsman preserved a spiritual integrity no machine could match. By 1896, those ideals had spread across Britain and abroad through the Arts & Crafts movement. The movement’s disciples—C.R. Ashbee, Charles Voysey, and the Guild of Handicraft—sought to build communities where beauty and labor could coexist without hierarchy.

Yet as the century waned, the dream grew fragile. Industrial capitalism had no patience for the slow rhythms of handmade production. The machine, Morris’s lifelong antagonist, had become the century’s chosen instrument. His workshops could produce exquisite tapestries, but the new world demanded steel and glass.

The workshop as philosophy

For Morris, the workshop was not a business; it was a model of society. He believed the act of making could teach moral clarity. Each craftsman was to be both artist and laborer, designing and building his own work. This unity of conception and execution, he argued, would restore dignity to labor and joy to creation. In the industrial age, where production was fragmented and anonymous, that unity seemed revolutionary.

The Merton Abbey enterprise embodied this conviction. There, weaving looms clattered beside vats of natural dye, and artisans debated poetry over their tools. Visitors in 1896 found an atmosphere closer to a monastery than a factory—orderly, disciplined, and quietly devout. Every curtain and carpet carried the trace of human intention.

Three tenets defined Morris’s legacy:

- Integrity of work: the maker’s hand as the measure of value.

- Unity of design: every object part of a coherent whole.

- Moral beauty: art as the visible form of ethical life.

A British seed with European branches

Though rooted in England’s medieval revival, Morris’s influence extended across Europe. In Belgium and France, his ideas merged with the Art Nouveau impulse toward total design. In Vienna, Josef Hoffmann and the Wiener Werkstätte would later turn his philosophy into a precise modern grammar of form. Even in Scandinavia, the preference for honest materials—bare wood, simple textiles—owed something to Morris’s gospel of craft.

By 1896, the Arts & Crafts ethos had become both a movement and a mood. Its exhibitions drew not only designers but also social reformers and educators. It offered a vision of art as a public good, accessible through craftsmanship rather than wealth. The movement’s emphasis on functional beauty anticipated the design ethics that would shape the 20th century—from Bauhaus clarity to modernist restraint.

The tension between beauty and progress

Yet there was irony in the timing of Morris’s death. While he denounced mechanization, his ideals helped prepare the very aesthetic that the machine would later perfect. The clean lines and functional honesty of modern design were the logical outcome of his plea for simplicity. What he saw as a moral argument against industry became, in the hands of later designers, an argument for efficiency. History, as always, rewrote its prophets.

Even his socialism, rooted in medieval fellowship, was less political program than ethical vision. He imagined a society where joy in labor replaced profit as the measure of success—a dream as impractical as it was noble. But its poetic force endured. Artists who rejected his medieval nostalgia still shared his belief that beauty could heal the alienation of modern life.

Transatlantic echoes

Across the Atlantic, the Arts & Crafts philosophy took on new vigor. In Boston and Chicago, designers such as Gustav Stickley and the architects of the Prairie School translated Morris’s ideals into the language of wood, brick, and sunlight. Their homes, open and unadorned, were acts of moral clarity—a democracy of design. The movement’s simplicity appealed to a nation still defining its cultural identity: plain, honest, and spacious.

By 1896, this transatlantic dialogue was well under way. American journals published Morris’s lectures; his wallpapers decorated middle-class parlors from New York to San Francisco. Even those who never read his writings absorbed his conviction that the way one built a chair or a window could express an entire worldview.

The quiet conclusion

Morris’s death was not tragedy but closure. His body of work, vast and diverse, had already reshaped how artists and audiences thought about design. What he left behind was less a style than a conscience. In the studios of London and the workshops of Europe, his ghost lingered: a reminder that beauty required sincerity, that ornament without purpose was deceit, and that the hand of the maker could ennoble the machine rather than resist it.

By the winter of 1896, newspapers remembered him as the “last great English craftsman.” Yet his spirit, paradoxically, looked forward. Within a decade, architects like Mackintosh and Hoffmann would transform his handmade ideal into the crisp geometry of modern design. The torch he carried from the Middle Ages burned on, reshaped but unextinguished.

William Morris died as the nineteenth century itself was dying—a century of ambition, conscience, and invention. His final gift was a conviction that art and life, once sundered, must someday be reunited. Even in a mechanized world, he believed, the human hand could still make meaning.

Chapter 8: Edvard Munch and the Anxiety of Modern Life

By 1896, the optimism that had once animated Europe’s artists was giving way to something more uncertain. Beneath the gilded surfaces of Art Nouveau and the idealism of the Arts & Crafts movement, a quieter tension began to pulse: the modern soul’s unease. No artist embodied that unease more completely than Edvard Munch. He was neither a Symbolist nor an Impressionist in the strict sense, yet he carried fragments of both—transmuting their beauty and color into psychological revelation.

From sensation to psyche

Munch’s paintings of the mid-1890s turned experience inside out. Instead of recording the world, he mapped emotion. The landscape became a mirror for thought; color became the language of dread and desire. In 1896, living between Paris and Kristiania (now Oslo), he was producing some of his most haunting images—The Kiss, Madonna, and a series of prints that distilled his emotional vocabulary into stark form.

In The Kiss (1896), two figures merge in a shadowed interior, their faces blending into a single, faceless silhouette. What might have been romantic becomes uncanny. The lovers seem less united than absorbed, their individuality erased by longing. Munch’s brushwork is subdued, almost tender, yet the mood is suffocating. It is not affection but fusion—love as surrender of self.

This painting, small and quiet, carried the charge of modern psychology. Years before Freud’s theories gained currency, Munch had visualized the hidden drama of identity: the tension between intimacy and annihilation.

Color as confession

While Impressionism had treated color as light, Munch treated it as emotion. His palette in 1896 glowed with nervous intensity—acid yellows, bruised purples, blood-like reds. These were not decorative choices but confessions. He once wrote, “I do not paint what I see, but what I saw,” meaning what remained in memory, tinged by feeling.

His technique was unorthodox: thin paint spread over unprimed canvas, as if the image were seeping through rather than sitting on the surface. The result was both fragile and direct, like handwriting. The roughness scandalized traditionalists, but to Munch it was honesty—the visible trace of an inner state.

Three qualities marked his work of that year:

- Transparency of emotion, every brushstroke trembling with awareness.

- Flattened perspective, emphasizing mental space over physical depth.

- Symbolic compression, turning scenes into archetypes rather than narratives.

Munch’s world was filled with recurring motifs—women, forests, waves, the sickroom, the shore at twilight. Each appeared not as an event but as an echo, reverberating through memory.

The printmaker’s revelation

In 1896, Munch also discovered the expressive power of printmaking. Working with the master printer Auguste Clot in Paris, he produced color lithographs that reinterpreted his earlier paintings. The Scream, Madonna, and The Kiss became icons of modern anxiety in these new forms. Lithography allowed him to simplify and exaggerate line, to make emotion legible at a glance.

The process itself suited his temperament. It was both mechanical and intimate: drawing on stone, in reverse, knowing the result would be multiplied. Munch found poetry in that paradox. His prints traveled farther than his paintings ever could, carrying the ache of Northern solitude into the heart of Parisian modernity.

Isolation as subject

The late nineteenth century’s technological triumphs—electric light, telegraphy, photography—had promised connection. Munch showed their opposite: isolation. His figures, often surrounded by halos of color or shadow, seem detached from one another even when touching. In Evening. Melancholy and Anxiety (both near this period), the horizon glows with dying light, yet the people on the shore stand estranged, looking inward.

Munch’s genius was to treat solitude not as subject matter but as condition. His characters are caught between interior and exterior worlds, unable to reconcile them. The same duality shaped his own life: the painter of the crowd who felt perpetually alone, the Norwegian in Paris who carried home’s northern dusk wherever he went.

From Symbolism to Expressionism

Though aligned with the Symbolists, Munch’s art was too raw for their refined mysticism. He stripped symbolism of allegory and replaced it with psychology. Instead of saints or myths, he painted human states: jealousy, desire, fear, fatigue. What the Symbolists hinted, he declared. His was the first art of the nervous system—restless, exposed, unadorned.

The generation that followed would recognize him as their forerunner. The Expressionists of Germany, particularly the artists of Die Brücke, would later see in Munch’s palette and emotional intensity the blueprint for their revolt. But in 1896, he remained an outsider: too modern for Norway, too Nordic for Paris, too personal for any school.

The modern condition

Munch’s art of that year offered a revelation Europe scarcely wanted to face—that progress did not cure loneliness. His interiors were as haunted as his landscapes. He painted silence thick enough to hear. In that silence, modern man discovered himself: intelligent, conscious, and profoundly alone.

Yet Munch’s melancholy was not despair. Beneath the anxiety ran a current of sympathy. His figures, for all their vulnerability, retain dignity. He did not mock the human condition; he illuminated it. His vision was not a rejection of beauty but its transfiguration—beauty as honesty, as endurance.

By the end of 1896, Munch’s prints and canvases had begun circulating through Europe, unsettling viewers with their quiet violence. Critics called them “unhealthy,” “degenerate,” “too subjective.” Time would prove otherwise. They were simply truthful.

As the century turned, art’s confident surface began to crack. Through that crack, Munch’s anxious light entered, pale and trembling, but unmistakably real. The twentieth century would recognize itself in that glow.

Chapter 9: Rodin, Claudel, and the Sculptural Body

The art of the 1890s often spoke of dreams, but sculpture still required the stubborn truth of touch. It was the medium of weight, volume, and resistance—the human form rendered in defiant permanence. In 1896, Auguste Rodin and Camille Claudel stood at the height of that paradox: shaping movement out of immovable stone, carving emotion into flesh. Their intertwined stories—personal, artistic, and tragic—embodied the tension between freedom and form that defined the fin de siècle.

Rodin’s unfinished miracle

By 1896, Rodin was a living monument. His Balzac—the colossal bronze commissioned by the Société des Gens de Lettres—was still the subject of scandal. First exhibited in plaster in 1898 but conceived and worked on throughout the mid-1890s, the statue had already entered legend as the most controversial sculpture in France. Instead of idealizing the great novelist, Rodin presented him as a rough, monolithic presence: robe clinging, body swelling, head uplifted in abstraction. It was less a likeness than an incarnation of creative energy.

Critics were divided between reverence and horror. Some called it a mass of clay left unfinished; others sensed that Rodin had discovered a new kind of monumentality. The sculptor defended himself with serene obstinacy. “Beauty,” he said, “is everywhere. It is not in the form, it is in the emotion the form suggests.”

That principle—suggestion through surface—had become Rodin’s true subject. In the 1890s, he modeled not anatomy but vibration: the flesh caught mid-gesture, the tension before movement. The marble seemed to breathe. His figures were never quite finished; their edges melted into the stone as if still emerging from thought.

The language of incompletion

Rodin’s preference for roughness was a rebellion against academic finish. Polished marble denied the hand that made it. He wanted the tool marks to remain visible, the vitality of process intact. The result was sculpture that felt alive not because it imitated life but because it recorded labor—the trace of creation itself.

Three characteristics defined Rodin’s art at that moment:

- Fragmentation, treating torsos or hands as self-sufficient expressions.

- Texture as meaning, the chisel’s rhythm conveying pulse and heat.

- Emotive imbalance, bodies caught in psychological motion rather than classical repose.

To a generation accustomed to smooth allegory, this was revelation. The modern body was not perfect; it was expressive.

Camille Claudel’s rebellion

Working in the same years—and, until recently, in the same studio—Camille Claudel transformed Rodin’s innovations into something altogether different. Her sculptures from around 1896, including The Wave (conceived c.1896, cast later), fused technical mastery with an emotional precision rarely seen in marble. Where Rodin celebrated power, Claudel captured vulnerability: the moment a gesture turns to feeling.

The Wave shows three women poised beneath an onrushing crest of onyx. Their bodies tilt in unison, part dance, part surrender. The composition is as fluid as water, yet carved from stone. Claudel’s use of contrasting materials—white marble figures against translucent green onyx—was revolutionary. It gave physical reality to metaphor: human emotion overwhelmed by nature’s force, resilience glowing through fragility.

Her art was not derivative but dialectical. If Rodin’s sculpture expressed the masculine will to form, Claudel’s expressed the intelligence of sensation—the awareness that emotion moves through the body before the mind names it. She turned the tactile into the psychological.

The partnership and its echo

Their personal entanglement had long fascinated the Parisian art world. Rodin had recognized Claudel’s genius early, taking her as pupil, collaborator, and lover. By the mid-1890s, that bond had fractured into rivalry. Claudel sought independence; Rodin, already famous, could not escape her influence. Each carried the other’s imprint. His later works gained tenderness; hers, intensity edged with despair.

In 1896, she exhibited Clotho—an image of the Fate from Greek myth, old and ravaged, her hair a web of destiny. The sculpture was astonishing in its brutality: a body twisted by time, yet rendered with exquisite sympathy. It was Claudel’s meditation on aging, control, and the loss of power—all themes that mirrored her own position in a world that doubted her authority.

Their dialogue through sculpture was not sentimental but metaphysical. Each explored how spirit inhabits matter, how movement survives in stillness. Between them, the human body became both battlefield and miracle.

The European resonance

Across Europe, sculptors watched Rodin and Claudel with awe and apprehension. In Britain, Alfred Gilbert’s Eros for Piccadilly Circus (completed earlier but celebrated anew in the mid-1890s) showed how public sculpture could absorb sensual vitality. In Vienna and Prague, younger artists studied Rodin’s fragmentation as a license to modernize classicism. Even Auguste Renoir, by then returning to sculpture, confessed envy of Rodin’s “power to make marble feel warm.”

Sculpture, once the most conservative of arts, had become a laboratory for modern feeling. The old hierarchies of subject and finish were collapsing. To touch clay or stone in 1896 was to confront the living metaphor of transformation.

The tragedy of brilliance

Claudel’s brilliance, however, came at terrible cost. Financial hardship, critical neglect, and the shadow of Rodin’s fame eroded her confidence. By the following decade she would fall into isolation, her work misunderstood, her life consumed by illness and confinement. Yet in 1896 she was still radiant, still sculpting with a precision that made marble tremble.

Rodin, meanwhile, would live to see his reputation secure, his methods institutionalized. But in his late interviews he spoke of her with regret and admiration, calling her “a force of nature.” History, slowly correcting itself, has come to see them as equal poles of a single discovery: that sculpture’s deepest subject is not the body but the soul pressing against its boundaries.

The chisel and the century

The partnership’s legacy reached far beyond their lifetimes. The expressive fragmentation of Rodin and Claudel paved the way for the distortions of Expressionism and the abstractions of modern sculpture. Their insistence that form should record emotion—its tremor, its strain—altered the medium’s language forever.

By the end of 1896, the sculptural body had ceased to be an object of admiration. It had become a living surface of experience. Each unfinished edge, each rough plane, testified that art’s purpose was not to idealize life but to wrestle with it.

Rodin’s workshop on the rue de l’Université hummed with apprentices; Claudel’s studio, quieter, filled with half-carved forms that seemed to breathe when light struck them. In both spaces, stone was turning human again. The modern century was already taking shape under their hands.

Chapter 10: The New Century in Japan and Beyond

By 1896, Japan had become both a fascination and a mirror for the Western art world. What began decades earlier as Japonisme—a collector’s craze for prints and ceramics—had matured into something deeper: a conversation between two civilizations, each reshaping the other’s understanding of modern beauty. Europe looked to Japan for purity of design and discipline of form; Japan looked to Europe for the power of reinvention. Out of that exchange came an art that no longer belonged to either world alone.

The Meiji vision

Japan in 1896 was in the midst of its Meiji period transformation—a national project of modernization that fused technological ambition with aesthetic self-awareness. Factories, railways, and telegraph lines had spread across the islands, but so had art schools and design societies. The Tokyo Fine Arts School (Tōkyō Bijutsu Gakkō), founded in 1887, stood as the symbol of this synthesis. By the mid-1890s it was training a generation fluent in both native traditions and Western technique.

Artists such as Kuroda Seiki, who had studied in Paris under Raphael Collin, brought back the lessons of Impressionism but applied them to Japanese subjects. His painting Lakeside (1897, conceived 1896) revealed a quiet dialogue between East and West: a figure rendered with Western modeling yet composed with Japanese restraint. The result felt neither imported nor provincial. It was a declaration that modern art could be bilingual.

Woodblock revival and Western gaze

Ironically, while Europe adored Japanese prints for their stylization and color, Japan itself had begun to neglect them under industrial pressure. Yet by 1896, a revival was stirring. Artists like Tsukioka Yoshitoshi—whose final series New Forms of Thirty-Six Ghosts (completed 1892) still circulated widely—had proven that the woodblock could evolve. Younger printers took inspiration from Western lithography, experimenting with new pigments and perspectives.

In this way, the influence looped back. French poster artists, from Chéret to Lautrec, borrowed Japanese flatness and asymmetry; Japanese designers, in turn, absorbed the Western emphasis on contour and shading. The result was a cosmopolitan visual vocabulary that transcended national borders. The flowing line of Mucha’s posters or the patterning of the Nabis would have been unthinkable without the Japanese woodcut’s example.

Three features defined this dialogue:

- Economy of line, treating simplicity as virtue rather than limitation.

- Harmony of asymmetry, balancing tension and calm within a single frame.

- Integration of image and design, erasing the boundary between art and object.

These principles migrated freely—from kimono fabrics to Parisian wallpapers, from fan prints to stained glass.

Australia and New Zealand: light at the edge of the world

At the farthest reaches of the British Empire, a related transformation was underway. In Australia and New Zealand, artists were forging their own relationship with light and land. By 1896, painters such as Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, and Charles Conder had defined what critics would call the “Heidelberg School”—an Impressionism adapted to the Southern Hemisphere’s fierce clarity.

Streeton’s Golden Summer, Eaglemont (1889) had already shown the path; the years that followed, including works exhibited through the mid-1890s, cemented a vision of the landscape as both national emblem and spiritual experience. The bush was no longer backdrop but protagonist. Its dry heat and endless space offered a palette far removed from Europe’s misty tones.

In New Zealand, artists like Petrus van der Velden brought a more introspective mood—stormy, monumental, steeped in Romantic melancholy. Together, the ANZAC region’s painters turned isolation into originality. The world’s edge became art’s horizon.

America’s transpacific curiosity

Across the Pacific, American artists were equally captivated by the East. The collector Charles Lang Freer, soon to endow the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery, was acquiring Japanese and Chinese art with missionary zeal. Whistler’s subtle tonalities, already admired in Europe, resonated deeply with the Japanese aesthetic of restraint. His followers—the so-called “Tonalists”—extended this harmony into the new century.

By 1896, the American art press was filled with essays on “the Japanese spirit in design.” Architects, influenced by both Arts & Crafts ideals and Eastern simplicity, began to imagine houses as total works of art. Frank Lloyd Wright would later translate that vision into the language of horizontal planes and open interiors, but its seed lay in this moment of cross-cultural curiosity.

Reciprocity and renewal

What made 1896 distinctive was that the exchange was no longer one-sided. Japan was no longer the exotic other; it was an equal participant in shaping global modernism. The same year that Mucha’s posters adorned Parisian streets, Japanese artists exhibited oil paintings at home that blended Western realism with native sensitivity to space. This reciprocity gave modern art its international grammar: clarity, rhythm, synthesis.

Europe, in turn, learned modesty. The Japanese concept of ma—the meaningful interval, the beauty of pause—entered Western design philosophy. It tempered the fever of Art Nouveau with quietness. It suggested that ornament could breathe, that silence itself could be decorative.

The philosophy of restraint

As the century neared its end, the Japanese lesson became clear: progress did not require clutter. The simplest line could express complexity; the most open space could carry emotion. This idea would guide the next century’s modernists, from Wright’s houses to Mies van der Rohe’s buildings. The Meiji synthesis of craft and innovation thus anticipated the minimalism of the twentieth century.

A new horizon

In 1896, ships carried not only goods but ideas across the oceans. Prints, posters, and photographs circulated faster than ever before. The art world, once provincial, was becoming planetary. Yet the exchange was not a flattening. Each culture deepened the other. Japan reminded Europe that modernity need not mean aggression; Europe showed Japan that tradition could evolve.

Out of that dialogue emerged a shared conviction: that art’s task was to reconcile progress with grace. The next century would test that conviction brutally, but in the calm balance of 1896, it seemed possible.

The world had begun to look at itself across oceans—and for the first time, recognized the reflection.

Chapter 11: Early Cinema and the Moving Image

In 1896, the still image began to move. What painting had pursued for centuries—the illusion of life—was suddenly accomplished by light and machinery. The year saw the first flowering of cinema as both spectacle and art, a phenomenon that astonished even those who had already lived through photography’s revolution. The new invention was more than a novelty; it was a mirror held up to time itself.

The birth of a new art form

On December 28, 1895, the Lumière brothers had held their first public screening in Paris. But it was in 1896 that motion pictures truly entered public consciousness. Within months, traveling exhibitions spread across Europe, America, and Asia. People who had never seen a painting by Monet or sculpture by Rodin crowded into halls and fairgrounds to watch flickering images of workers leaving a factory, a train arriving at a station, or waves breaking on a shore.

The audiences gasped not at narrative but at presence. The moving image carried the shock of reality reborn. It collapsed the distance between art and life. What the Impressionists had sought through brushstroke and color—the vibration of light, the instant of perception—the Lumières achieved through mechanical projection.

Technology and wonder

The new medium belonged to no single nation. In England, Robert Paul and Birt Acres were showing films to packed houses. In America, Thomas Edison’s Vitascope projected its first public screenings in New York in April 1896. In Russia, the Moscow exhibition featured imported Lumière films. Within a single year, cinema had become a universal curiosity, its grammar still forming but its power undeniable.

Three features made early cinema revolutionary:

- Temporal realism, the depiction of unfolding time rather than frozen moments.

- Mechanical reproduction, allowing art to travel faster than the artist.

- Collective experience, spectators sharing wonder in darkness.

It was the first art form born entirely of the machine age—and the first to command mass audiences.

Painters confront the moving world

For painters, cinema was both revelation and threat. Some saw in it the fulfillment of their own ideals: Monet’s shifting light, Degas’s fascination with motion, Seurat’s study of optical vibration. Others feared obsolescence. If a machine could record movement and light with perfect fidelity, what remained for the artist?

Yet the early films, with their ghostly flicker and dreamlike rhythm, offered something no camera could replace—the aura of the ephemeral. Their brevity and silence resembled fragments of memory more than reality. Artists began to sense that this mechanical art was not realism’s enemy but its successor. It freed painting to pursue what the camera could not: inner vision.

In 1896, the worlds of art and cinema were still close enough to share vocabulary. The Lumières titled their films views—“actualités”—as if they were moving landscapes. The camera’s frame, like the painter’s canvas, defined both vision and limit.

Motion as metaphor

The fascination with motion pervaded the decade. Étienne-Jules Marey’s chronophotographic studies, Eadweard Muybridge’s sequences of human and animal locomotion, had already dissected movement scientifically. But cinema reassembled it emotionally. Watching a train enter a station or a child run toward the camera, viewers felt time made visible—a new intimacy with the world’s flow.

This sense of immediacy resonated deeply with the fin-de-siècle imagination. The Symbolists sought to evoke unseen rhythms; the Impressionists captured momentary light; the Nabis turned stillness into meditation. Now, film revealed that every gesture, however fleeting, could be preserved. Time itself became material.

The painter’s dilemma

By 1896, artists had begun to experiment with photographic projection as an aid to composition. Some feared contamination; others saw opportunity. The device called the magic lantern, ancestor to the film projector, allowed images to be enlarged and traced. Toulouse-Lautrec reportedly attended early screenings, fascinated by the dancers’ jerky rhythm. He understood that movement could itself be a form of design.

Cinema’s rise thus forced painters to redefine their purpose. If film could show what eyes saw, painting would show what the mind remembered. That shift would lead directly to the subjectivity of modern art—the inward turn of Symbolism, Expressionism, and Surrealism.

The architecture of dreams

In France and Britain, filmmakers quickly began to explore cinema’s poetic potential. Georges Méliès, a magician turned director, opened his Théâtre Robert-Houdin to moving pictures in 1896. Within months he was crafting miniature narratives, adding painted backdrops, dissolves, and hand-tinted color. Méliès transformed the camera from a documentarian tool into an instrument of illusion. His short films—of devils, astronomers, and vanished ladies—reclaimed fantasy for the modern world.

His art owed as much to stage design and painting as to engineering. Méliès’s sets resembled tableaux vivants, his gestures choreographed like brushstrokes. The union of technology and imagination had found its first prophet.

A world newly visible

What cinema revealed was not merely motion but modernity’s texture—the crowd, the machine, the street. The Lumières’ Workers Leaving the Factory and Arrival of a Train were more than curiosities; they were documents of industrial life, showing labor and travel as spectacle. The humblest subjects, projected on a sheet, acquired dignity. The moving image democratized attention.

The camera also altered perception itself. Once people had seen their own gestures repeated on screen, they never looked at movement the same way again. Time had acquired a mirror.

Echoes and consequences

By the end of 1896, newspapers across Europe hailed the cinematograph as a marvel that would “replace the theater, the newspaper, and even painting.” Such prophecies were half jest, half awe. In truth, cinema would not replace older arts—it would transform them. The dynamic composition of Futurism, the framing of Expressionism, the montage of Cubism—all would draw energy from that first astonished year.

Art, long devoted to depicting life, had suddenly found itself in competition with life’s reproduction. The response was not retreat but expansion. If the machine could record surfaces, the artist would reveal depths.

The beginning of modern vision

In 1896, the camera captured movement for the first time, but what it truly revealed was perception itself—the act of seeing as experience. For centuries, painting had tried to convey the sensation of duration. Cinema made duration visible.

The century ahead would belong to that discovery. Yet even in its infancy, the new art possessed a strange grace. The flicker of light on the screen resembled the flicker of consciousness: fragile, continuous, impossible to hold.

The Lumières had named their invention after illumination, and the name proved prophetic. In the dim halls of 1896, as faces glowed before a moving image for the first time, humanity glimpsed its future—not in stillness, but in motion.

Chapter 12: A Year of Premonitions

The year 1896 stands in retrospect like the last moment before a wave breaks. The world had not yet entered the convulsions of the new century—no world wars, no machines of total industry—but the air was charged with expectation. Artists sensed that change was no longer coming; it had already begun. Their work that year shimmered with foresight, the uneasy knowledge that beauty itself was about to be redefined.

The gathering of threads

Looking back, the art of 1896 seems impossibly varied—Impressionism’s final grace, Symbolism’s inward fire, Art Nouveau’s ornamental bloom, the experiments of cinema and design. Yet beneath the diversity ran a common pulse: the search for unity in a disjointed age. Every movement, from Monet’s cathedrals to Rodin’s unfinished marbles, attempted to reconcile opposites—technology and craft, reason and dream, permanence and flux.

Europe’s cities embodied that same tension. Paris glowed with electric light, its boulevards alive with posters and promise. Vienna simmered beneath its polished surface, soon to erupt in Secession. London balanced nostalgia and invention. Across oceans, Tokyo and Melbourne, Boston and New York were catching the fever of self-conscious modernity. The world was no longer a series of distant centers; it was a single network of influence, humming with shared imagery.

Art as foretelling

Each great artist of 1896, knowingly or not, foreshadowed the century to come.

- Monet anticipated abstraction, reducing cathedral stone to vibration.

- Redon anticipated Surrealism, making the invisible visible.

- Toulouse-Lautrec prefigured mass media, turning print into performance.

- Bonnard and Vuillard anticipated the psychology of space.

- Rodin and Claudel anticipated Expressionism, sculpting emotion itself.

- Munch prophesied the inner storms of the modern psyche.

- The Lumière brothers introduced the moving image that would dominate human imagination thereafter.

Together, they formed a kind of accidental council, each working in solitude yet echoing the others’ intuition that art’s subject was no longer the world but perception—the way the human mind experiences reality under the pressures of modern life.

The twilight of the old order

The 19th century’s grand confidence in progress was fading. The same science that had revealed the atom and the photograph also exposed instability. In philosophy, Nietzsche’s death in 1900 would mark the end of moral certainty; in politics, the old empires creaked under their own weight. Artists, more sensitive than most, registered the tremor first.

In their hands, representation began to dissolve. Perspective flattened, figures became symbols, color detached from nature. This was not decay but transformation. The solidity that had defined Western art since the Renaissance was melting into rhythm and idea. The new century would soon complete that process through the formal revolutions of Cubism, Fauvism, and abstraction.

Premonitions of the machine age

Even the most handcrafted art of 1896 carried the seed of industrial modernity. The posters of Mucha and Lautrec, the serial prints of Munch, the films of the Lumières—all depended on mechanical reproduction. What Morris had feared and Art Nouveau had embraced now became unavoidable: the machine as collaborator. The artist’s task was no longer to resist it but to humanize it, to draw poetry from precision.

The same mechanical rhythm that powered cinema and printing presses would soon drive the century’s architecture, its music, and its wars. Yet in 1896, the relationship still felt innocent, even hopeful. Machines were new instruments of wonder, not yet tools of destruction.

A moment of poise

What makes the year unforgettable is its equilibrium. The past and future, faith and doubt, craft and technology—all held one another in temporary balance. The art of 1896 did not reject tradition; it stretched it until the frame almost broke. Painters still mixed their own pigments, sculptors still wrestled with marble, yet the air vibrated with new possibilities.

For one luminous instant, art stood poised between the tactile and the ethereal. That balance would not last. Within a decade, Picasso would shatter form, Kandinsky would renounce representation, and film would learn to dream. But in 1896, everything was still connected by a shared heartbeat—the belief that beauty could explain the world.

Legacy and resonance

Today, the works of that year feel prophetic not because they announced the future, but because they understood its cost. They knew that progress would bring isolation, that technology would both reveal and erode the human presence, that vision itself would become uncertain. Yet they faced those truths without despair.

Their legacy endures in the century that followed: in every modern experiment that seeks to reconcile clarity with feeling, invention with memory. 1896 taught art that to survive, it must change constantly—and that change itself could be beautiful.

The closing image

Imagine, then, the world on a winter evening in 1896. Electric lamps glow over a Paris boulevard plastered with Lautrec’s posters. Somewhere in the same city, a small audience gathers to watch flickering shadows come to life on a white screen. In a quiet studio, Bonnard adjusts a brushstroke of light on a woman’s shoulder. In Norway, Munch studies two figures fused in a kiss. In London, news of William Morris’s death lies folded beside a copy of The Studio magazine, already filled with new names.

The century is turning, though the clock has not yet struck. The artists feel it before anyone else—the tremor, the promise, the unease.

Art in 1896 stood at the threshold of modernity, looking both backward and forward with equal tenderness. It was a year of endings disguised as beginnings, a moment when the old world dreamed its last beautiful dream before awakening to the modern age.