Before there were towns in Kansas, there were measurements. Before there were artists, there were maps. The first visual records of the region were drawn not in pursuit of beauty, but in the service of control: federal surveys, military reconnaissance sketches, railroad plans. In the decades before Kansas entered the Union in 1861, these technical images—often made by anonymous engineers or draftsmen—attempted to translate a resistant and ambiguous land into something legible. Lines were drawn across tallgrass prairie, rivers were charted, elevations plotted. Yet even in their technical precision, these early renderings betray a central truth: the Kansas landscape eludes simplification.

The visual problem of Kansas was never its lack of content. It was its refusal to conform to inherited models of pictorial space. Painters trained in the compositional conventions of European or East Coast landscape traditions—foreground, middle ground, receding background—found themselves facing horizons so distant and uninterrupted that perspective itself seemed to collapse. The land did not offer natural framing elements: no alpine diagonals, no coastal coves, no enclosing forests. Instead, the sky bore down, the fields opened outward, and the viewer’s position felt unanchored.

This sense of spatial disorientation, recorded in early field sketches and noted in travel accounts, shaped the way Kansas would be seen—and painted—for generations.

Vision in Advance of Settlement

As white settlement advanced into Kansas Territory in the 1850s, artists began to follow. Some arrived with surveying parties. Others were illustrators for newspapers or railroad companies. Their images served commercial or ideological purposes: to promote westward migration, to reassure distant investors, to depict the progress of civilization. Lithographers in cities like St. Louis or Cincinnati created hand-colored prints based on these field sketches, distributing idealized visions of Kansas towns, farms, and open land to audiences who had never been west of the Mississippi.

These images were not documentary. They were aspirational, sometimes entirely speculative. Towns might be drawn with full blocks of buildings before a single structure had been erected. Grain harvests appeared where no fields yet existed. In this sense, the earliest “art” of Kansas is inseparable from promotional fiction. The landscape was not yet an object of contemplation—it was a canvas for projection.

Yet within these works, there is something else: a confrontation with a new kind of spatial experience. Even the most optimistic town view could not avoid the vastness pressing in at the edges. The same flatness that frustrated painters also exerted a compositional pull. For artists used to organizing space into neat hierarchies of depth and form, Kansas forced a rethinking of both subject and technique.

Geography and Discomfort

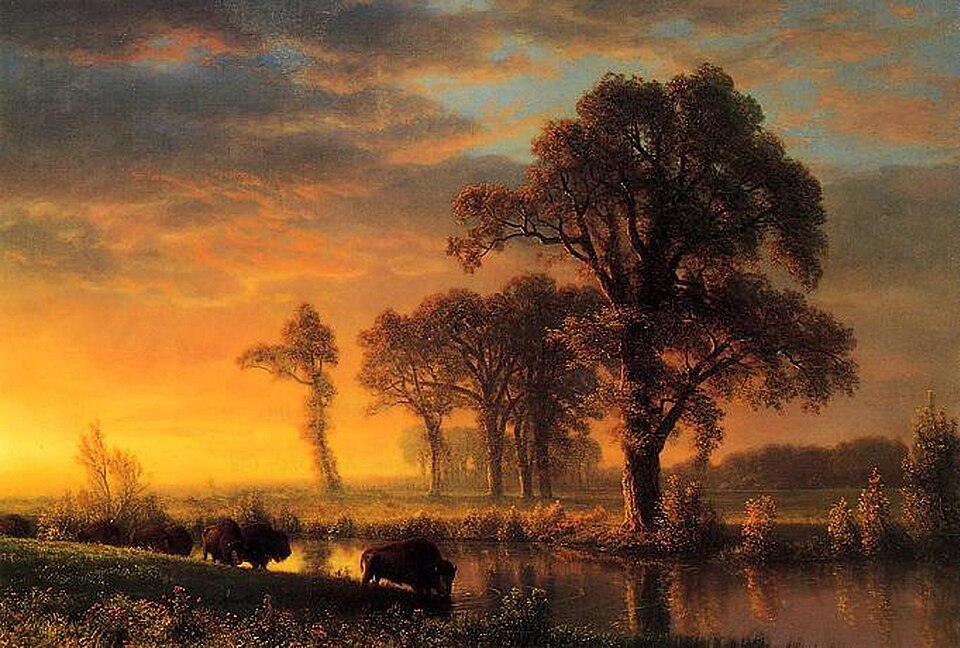

The Flint Hills, stretching diagonally through east-central Kansas, present a notable exception within this visual field. Composed of chert and limestone, the hills resist plowing and therefore preserved one of the last intact tallgrass prairie ecosystems in North America. Visually, the region offers subtle variation: rising swells of land, ribbons of green and brown, sharply lit in dry seasons and hazy in humid ones.

But even here, the challenge remains. The horizon persists. The lines are long and clean. Depth feels compressed, and color—not form—becomes the primary variable. For painters attempting to capture the region, this means abandoning depth cues and embracing atmosphere, tone, and rhythm. The prairie, rather than being a backdrop, becomes the subject.

The difficulty of capturing this is not merely technical. It is psychological. The landscape resists human scale. Settlements, trees, livestock—these diminish quickly into the openness. The viewer becomes small. The painter must decide whether to emphasize that scale, or to fight it.

A Pioneer of Perception

It was not until the arrival of Birger Sandzén in 1894 that Kansas began to yield a landscape painter equal to its particular demands. A Swedish-born artist trained in Stockholm and Paris, Sandzén took a teaching position at Bethany College in Lindsborg, a small town in central Kansas founded by Swedish immigrants. He would remain there for the rest of his life.

What distinguished Sandzén’s work from that of his predecessors was not simply his training, but his decision to accept the Kansas landscape on its own terms. Rather than trying to impose European compositional logic onto the prairie, he leaned into its spatial extremes. His paintings of the Smoky Hill River, limestone bluffs, and open pasturelands are characterized by thick brushwork, saturated color, and compressed depth. The land is not framed—it surges forward. The sky does not sit back—it looms.

Sandzén’s work is often described as expressionist, and indeed his use of color—violet shadows, orange grasses, teal skies—breaks decisively with realism. But his expressionism is rooted in close observation. What he achieves is not fantasy, but a heightened articulation of a landscape that resists subtlety. His brushstroke mimics the wind. His palette mimics the glare of light off stone. In his hands, the Kansas terrain becomes a space of formal intensity rather than narrative comfort.

Inheriting a Spatial Vocabulary

By the early twentieth century, the visual language Sandzén helped articulate—broad horizons, active skies, dense surface treatment—began to take hold in the work of other Kansas artists. Even those working in different styles or media absorbed the spatial problem as a defining condition. For many, painting Kansas meant learning to work without a foreground. It meant organizing space through tonal gradation or rhythm, not vanishing points. It meant acknowledging that most compositional activity would happen in the upper half of the canvas, where weather and light performed their variations.

This is not a regional limitation. It is a regional innovation. Artists who stayed in Kansas did not merely adopt local color—they developed a visual logic appropriate to the land. They learned to work not against flatness, but within it.

What began with surveys and speculative lithographs evolved into a quiet but persistent aesthetic: one that privileges space over object, distance over detail, and light over form. That aesthetic, once seen as provincial, now appears as a legitimate response to a place that has always resisted easy containment.

Chapter 2: Picturing Settlement — Art of the Homesteaders and Early Towns

Images Without Artists

The early decades of Kansas statehood produced a visual record that was both abundant and anonymous. Much of the art created during this period—roughly from the 1860s through the 1890s—was not made by professional artists but by settlers, surveyors, itinerant tradesmen, and schoolteachers. It took the form of sketchbooks, signboards, maps, painted walls, and illustrated ledgers. Most of it was never intended for exhibition. These were not works of self-expression; they were acts of documentation, orientation, and reassurance.

In sod dugouts and one-room schoolhouses, people drew and painted what they had seen or hoped to see: a house, a windmill, a stand of trees, a train line, a wheat field. These images served immediate functions. A painted sign might distinguish one merchant from another. A sketched map might guide a neighbor across unmarked prairie. A decorative border painted in berry pigment around the ceiling of a dugout might make the space feel less temporary.

What ties these disparate images together is not a shared style, but a shared circumstance. They emerged in conditions of instability. They were made by people building lives in an environment that felt provisional and frequently under threat. The making of images—however rudimentary—was one way of asserting permanence in a place that did not yet guarantee it.

Promotional Lithographs and the Architecture of Optimism

At the same time, a more public visual language was developing. As towns sprang up across Kansas, so did the need to advertise them. Lithographic firms, often based in larger cities like St. Louis or Chicago, specialized in bird’s-eye views—elaborate, often exaggerated depictions of towns and cities as seen from an imagined elevated perspective. These prints, popular between the 1870s and 1890s, presented Kansas towns as orderly, prosperous, and bustling.

In these lithographs, streets are perfectly graded. Trees are evenly spaced. Trains run on time. Courthouses rise from town squares like miniature state capitols. Churches, mills, and schools appear in abundance, even if their real-world counterparts were still under construction—or had yet to be built. The drawings were often based on partial surveys or verbal descriptions. Accuracy was beside the point. The image was a visual argument: this place exists, and it has a future.

These prints served multiple purposes. They reassured current residents, flattered civic boosters, and attracted new settlers. A well-executed lithograph could hang in a railroad depot or land office and persuade a hesitant migrant to stay. In this way, image-making became part of the machinery of settlement.

Yet even in their optimism, these lithographs reveal something deeper about Kansas as an artistic subject. The prairie creeps in at the edges. The town appears as an island of geometry surrounded by featureless space. The grid of civilization is always bordered by the unmarked plain. That tension—the desire for order against the persistence of openness—would recur in Kansas art for decades.

Homesteader Artifacts and Visual Habit

While public imagery promoted progress, private image-making persisted. Quilts, carvings, painted furniture, and decorated tools carried forward visual habits rooted in European and Eastern traditions. German, Swedish, and Czech settlers, among others, brought patterns, symbols, and color schemes that adapted slowly to the new environment. The visual culture of the Kansas homestead was not neutral—it was coded with memory, belief, and identity.

Some households included framed chromolithographs of religious scenes or portraits of political figures. Others made do with newspaper clippings pinned to walls or pages from mail-order catalogues tacked up for decoration. The act of decorating—even modestly—suggests a desire to soften or humanize a landscape that could be overwhelming.

In certain communities, itinerant painters offered their services for wall murals, sign painting, or even portraits. These were not academic artists. They were tradesmen, often self-taught, and their work bore the hallmarks of vernacular style: flattened forms, direct gaze, and symbolic content. In this context, portraiture was not about likeness alone. It was about establishing continuity in a place where time often felt slippery.

The First Civic Patrons

By the late 19th century, as towns stabilized and wealth accumulated, civic institutions began to commission artworks. Courthouses and schools occasionally featured murals or painted seals. Some banks and insurance offices hung oil paintings of local scenes or founding figures. These works were usually conservative in style, drawn from widely available templates, and intended to convey stability and respectability.

The impulse to collect also began to take hold. Private individuals who had made fortunes in land, cattle, or rail began acquiring art, sometimes as investment, sometimes as civic gesture. The seeds of future museum collections were sown here—not through coherent vision, but through accumulation.

What emerged from this period was a nascent sense that Kansas art might exist as a category—not merely as illustration, but as expression. The subjects were still familiar: farms, towns, families, weather, work. But they began to appear in compositions that suggested aesthetic ambition rather than documentation alone.

Transition Toward Art as Discipline

By the turn of the century, the distinction between “making images” and “making art” began to clarify. Art instruction entered public schools and teacher-training colleges. Students learned drawing not just as a useful skill, but as a practice with its own logic and value. In some cases, former settlers who had once sketched for necessity found themselves taking formal classes. A vocabulary of perspective, contour, tone, and line replaced the improvisations of survival.

At the same time, the first art societies and clubs were formed in cities like Topeka and Wichita. These groups organized exhibitions, brought in lecturers, and began to cultivate public interest in art as a communal good. While their tastes remained conservative—favoring realism, portraiture, and sentimental scenes—they established an important precedent: that Kansas was not only a place where art could be made, but where it could be seen and discussed.

By 1900, the visual landscape of Kansas had changed. What began as uncertain sketches and promotional prints had grown into a layered tradition. The prairie was no longer just a problem to be solved—it had become a place where images could take root.

Chapter 3: The Printmakers of Enterprise — Art and Industry in the 19th Century

Commerce as Medium

By the late 19th century, Kansas had entered a phase of rapid development. The railroads had carved new corridors through the prairie, towns had become cities, and commerce demanded a visual language of its own. In this environment, printmaking emerged not as an elite art form, but as an essential tool of business, infrastructure, and identity. Lithographs, wood engravings, and letterpress prints became the primary vehicles for visual communication in a state where speed, clarity, and reproducibility mattered more than elegance.

The printing press was not simply a means of dissemination—it was an instrument of invention. Artists, engravers, and technicians worked together to create posters, maps, stock certificates, illustrated newspapers, train schedules, and advertisements. Their work shaped how Kansas saw itself, and how it was seen by the wider country.

This was not printmaking as private expression. It was a public function, and the artistry it contained was often embedded in practical form.

Lithographs and the Logic of Growth

The most visible artistic form to emerge from this intersection of art and commerce was the bird’s-eye view lithograph. Between the 1870s and 1890s, firms like Ruger & Stoner and the American Publishing Company produced panoramic prints of Kansas towns that blended fantasy, survey data, and promotional design. These images were typically drawn from a high, imaginary vantage point and depicted every structure, street, and public building in minute detail.

Commissioned by local chambers of commerce or business groups, these prints were tools of persuasion. A well-rendered lithograph could suggest permanence, prosperity, and civic order—qualities highly prized in a region still emerging from frontier conditions.

To create these works, artists combined direct observation with cartographic extrapolation and studio rendering. They exaggerated density, idealized perspective, and placed signature buildings prominently in the foreground. The result was less a document than a visual prospectus.

Though widely circulated, these prints have often been neglected in traditional art history. Yet they represent a distinctive merger of technical skill, artistic composition, and economic aspiration. In them, Kansas appears not as a wilderness or a myth, but as a buildable, sellable, and printable reality.

Newspapers and the Engraver’s Craft

Parallel to the rise of lithography was the growth of illustrated newspapers, which relied on wood engravings and, later, halftone processes to reproduce images alongside text. In towns like Topeka, Lawrence, and Leavenworth, weekly and daily papers hired staff illustrators or contracted engravings from regional studios.

These images covered a wide range: portraits of prominent citizens, illustrations of train derailments, depictions of livestock fairs, architectural drawings of new buildings, and renderings of civic events. The artists who made them often worked under intense deadlines and with limited source material. Their work was seldom signed and rarely preserved. Yet it shaped the visual memory of the state in ways more permanent than any single canvas.

Some engravers eventually moved into independent illustration or fine-art printmaking, but most remained within the structure of print commerce. Their anonymity does not diminish their influence. They built the visual grammar of civic identity, using burin and block rather than brush and canvas.

Print Shops as Hybrid Studios

Commercial print shops also became informal studios where craftsmanship and artistry overlapped. In cities like Wichita and Kansas City, lithographers trained apprentices in draftsmanship, type layout, image transfer, and press operation. These were not art schools, but they taught skills that could—and sometimes did—lead to artistic careers.

In smaller towns, printers often wore multiple hats: typesetter by day, amateur etcher by night; newspaper layout designer in the morning, exhibition organizer in the evening. These hybrid identities challenge modern categories of artist versus artisan, fine art versus applied design.

The material conditions of Kansas contributed to this blurring. With fewer formal institutions and a smaller art market, the same individual might contribute to a political cartoon, a church bulletin, a schoolbook illustration, and a decorative broadside—all within the same month.

This multiplicity was not a compromise. It was a regional logic: make what is needed, use the tools at hand, apply skill where it will be seen.

The Graphic Shape of the State

Beyond cities and commerce, the most consistent form of print imagery in Kansas was the map. County atlases, railroad charts, land surveys, and geological diagrams were printed in vast numbers throughout the second half of the 19th century. Though ostensibly functional, many of these maps contain remarkable visual features: hand-colored townships, decorative cartouches, ornate typefaces, and vignettes of rural life.

In these maps, we see the prairie converted into property. Rivers become borders. Land is divided by grid, then further subdivided into ownership parcels. The flatness that so challenged painters became an asset for cartographers. Kansas—nearly rectangular, largely treeless, and sparsely populated—lent itself to diagram. The map, like the lithograph, became a means of making the land visible and, by extension, manageable.

For many Kansans, these printed maps were their first image of the state as a whole. In them, one could locate a farm, a road, a future railroad stop. The land ceased to be abstract. It gained shape, order, and potential.

Between Function and Form

The 19th-century printmakers of Kansas worked in a space between necessity and aesthetics. They were not bohemians or revolutionaries. They were engravers, compositors, survey illustrators, and job printers. Yet in the repetition of their work—in posters, newspapers, maps, and town views—they laid the groundwork for a distinctly regional visual language.

The compositional habits developed through these commercial forms—emphasis on line, clarity of structure, density at the center with space around the edges—would influence painting and photography in Kansas for decades to come. Even artists who rejected commercial imagery found themselves inheriting its spatial logic.

This is the paradox of early Kansas printmaking: it was not conceived as art, but it became foundational. In buildings full of ink, lead type, paper rolls, and noise, the images of Kansas were made—mass-produced, widely circulated, and quietly decisive.

Chapter 4: Art and Institutions — The Birth of Kansas Museums and Schools

From Cabinets to Collections

Art institutions in Kansas did not begin as grand buildings or carefully curated galleries. They began as cabinets, attics, classrooms, and personal holdings—spaces where objects were kept rather than exhibited. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, several colleges and universities in the state began to accumulate works of art, often through donations, bequests, or faculty initiative. These early collections were eclectic: plaster casts, reproductions, prints, ethnographic objects, and a few original paintings. Their primary purpose was instructional.

The transformation from object storage to public museum was slow and uneven, shaped by educational goals, philanthropic interest, and administrative will. But by the 1920s, a recognizably modern institutional framework for art had begun to form. Kansas was no longer just a site of art-making. It had become a place where art was taught, collected, and shown.

The University Museum as Anchor

The most significant institutional development in early Kansas art history was the establishment of the University of Kansas Museum of Art, now the Spencer Museum of Art, in Lawrence. Its origins lie in a 1917 gift by Sallie Casey Thayer, a Kansas City collector who donated more than 7,000 objects to the university on the condition that they be used to advance the study of art in the region.

At the time, the university had no dedicated art museum, and the collection was housed in various academic buildings. But by 1928, a formal museum had been established in Spooner Hall. It was modest in size, but ambitious in scope. The collection included European prints, Asian ceramics, American paintings, and decorative arts—objects meant to expose students and faculty to a broad visual tradition.

This early institutional step was critical. It meant that art in Kansas was no longer only local. Students could now study Renaissance engravings or Chinese porcelain in Lawrence. The act of seeing, comparing, and analyzing became central to the academic experience of art.

The Spencer Museum, as it would later be renamed, became more than a repository. It became a pedagogical tool, a public space, and a cultural anchor.

Regional Museums and College Galleries

While the University of Kansas led in scale, other institutions across the state developed their own art programs and exhibition spaces. Bethany College in Lindsborg, where Birger Sandzén taught for decades, played a key role in establishing a serious studio practice tied to regional subjects. Sandzén’s influence extended beyond the classroom; his advocacy helped create the conditions for what would become the Birger Sandzén Memorial Gallery, opened in 1957.

Washburn University in Topeka established what would become the Mulvane Art Museum, with a focus on education and regional exhibition. Kansas State University would later develop the Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art, emphasizing art of the Great Plains and works connected to the university’s history.

These institutions—while smaller than their metropolitan counterparts—were vital. They provided access to art for communities far from major urban centers. They hosted exhibitions, acquired work by Kansas artists, and supported academic instruction in art history and studio practice.

They also served as incubators. Students who encountered original artworks in these galleries often pursued careers in art education, museum work, or studio production. In this way, institutional exposure helped seed a generation of cultural workers across the state.

Teaching as Infrastructure

One of the defining features of Kansas art development is the role of the educator-artist. Faculty at universities and colleges were not simply instructors—they were active artists, critics, and organizers. Many taught full-time while maintaining studios, participating in exhibitions, and mentoring younger artists.

This dual role created a feedback loop. Institutions benefited from the visibility and output of their faculty, while artists relied on the stability and resources of their teaching positions. The result was a culture in which art was integrated into the rhythms of academic life: studios were part of campus, exhibitions were part of the calendar, and critique was part of the curriculum.

This structure also allowed Kansas to retain talent. Artists who might otherwise have left for the coasts stayed, taught, and worked. Their presence helped build continuity within the state’s art culture. Teaching became more than a job—it became a means of sustaining a local aesthetic ecosystem.

Civic and Community Spaces

Outside of universities, civic institutions also began to support art. Public libraries, women’s clubs, and cultural societies organized exhibitions, sponsored lectures, and hosted traveling shows. In some towns, post offices became de facto galleries after New Deal murals were installed. Local arts councils, often volunteer-run, formed in the mid-20th century to coordinate events and promote area artists.

These community efforts may lack the permanence of a museum collection, but they reflect a deep-rooted commitment to cultural life. They also widened access. Not everyone in Kansas could travel to Lawrence or Topeka to visit a museum, but they might encounter a painting in a school hallway, a photograph in a library case, or a sculpture in a public square.

The cumulative effect of these decentralized efforts was a culture of visibility. Art was not rarefied or distant. It was present—in classrooms, offices, lobbies, and auditoriums.

Institutional Taste and Regional Identity

As museums and galleries matured, they began to develop collecting philosophies. Some emphasized national or international art to broaden local exposure. Others prioritized regional work to affirm cultural identity. This balance—between looking outward and looking inward—has shaped Kansas art institutions ever since.

Some institutions, like the Beach Museum of Art, have focused intentionally on art of the Great Plains, recognizing that regional specificity can yield deep insight. Others, like the Spencer Museum, have pursued broader collections while still maintaining a commitment to Kansas artists.

This dual orientation—cosmopolitan and regional—has allowed Kansas museums to serve multiple audiences. They educate, preserve, and contextualize. They support contemporary production while honoring historical precedent.

Chapter 5: The Lindsborg Circle — Swedish Influence and the Smoky Valley Style

A Painter Arrives from the North

In 1894, a thirty-three-year-old Swedish artist named Birger Sandzén stepped off a train in central Kansas and took up a teaching position at Bethany College in the small town of Lindsborg. He had trained in Stockholm and Paris, studied under prominent figures in European painting, and could easily have returned to Scandinavia to pursue a conventional academic career. Instead, he remained in Lindsborg for the rest of his life.

Sandzén’s decision did more than surprise his contemporaries—it altered the trajectory of Kansas art. His work, his teaching, and his institutional influence seeded a distinctive artistic style rooted in the Smoky Hill River Valley and shaped by a hybrid of European modernism and prairie subject matter. The resulting artistic constellation—sometimes loosely referred to as the Lindsborg Circle—gave Kansas a visual language that was regional in content but international in ambition.

Teaching the Land

At Bethany College, Sandzén taught art for over fifty years. His curriculum emphasized drawing, painting, and printmaking, but also included composition, color theory, and exposure to European techniques. He taught generations of students not only how to paint the Kansas landscape, but how to see it with serious, modern eyes.

This pedagogical legacy cannot be overstated. Sandzén was not merely instructing students to record what they saw. He was urging them to transform it—to heighten color, to simplify form, to approach the prairie not as background but as subject. His example gave permission to amplify the ordinary: a stand of cottonwoods, a hillside, a dirt road could be rendered in purple, orange, and turquoise. The effect was not decorative—it was emphatic.

His style pushed against both the realism of earlier American painters and the conservatism of many Kansas art circles. Yet it was not abstract. The land was always recognizable. The brushwork might be bold, the colors intensified, but the place was never lost.

An Art Colony in Spirit

Though there was never a formal art colony in Lindsborg, the town functioned in many of the same ways. Visiting artists, former students, and regional painters came to study, to exhibit, or simply to spend time in a community where art was taken seriously. Sandzén himself traveled widely, exhibited across the country, and maintained correspondence with artists and curators nationally. But he always returned to Lindsborg.

The social structure of the town supported this continuity. Lindsborg had been founded by Swedish immigrants who valued education, culture, and community life. Music, literature, and visual art were not viewed as luxuries, but as extensions of civic and spiritual life. Bethany College hosted an annual Messiah performance, and the town supported choirs, theater groups, and visual artists.

In this environment, painting was not isolated. It was part of a shared rhythm: tied to seasons, festivals, school calendars, and church events. The Lindsborg Circle, such as it was, grew out of this continuity between aesthetic practice and community life.

The Smoky Valley as Subject

The terrain around Lindsborg provided an ideal motif for Sandzén and those he influenced. The Smoky Hill River winds through shallow limestone hills, dotted with cottonwoods, bordered by fields and grasslands. The horizon is low, the sky dominant, the land textured but not dramatic.

This environment demanded a different kind of landscape painting. There were no alpine peaks or coastal vistas. The challenge was how to convey movement, depth, and intensity in a land defined by subtle variation. Sandzén’s answer was to exaggerate the visual vocabulary: to paint the river in gestural strokes, to render the limestone in blocks of color, to let the sky surge rather than recede.

Students and contemporaries adopted and adapted these techniques. A shared approach began to emerge: strong outlines, simplified forms, heightened palettes, and a foreground that often pressed forward rather than leading into illusionistic space. This was not a school in the formal sense. But it was a method—and it was regional.

Printmaking and Paper Work

In addition to oil painting, Sandzén produced hundreds of prints—woodcuts, linocuts, and lithographs. These works, often smaller and more widely distributed than his canvases, helped spread the Smoky Valley style beyond Lindsborg. They also encouraged a particular kind of discipline: an attention to line, pattern, and compositional economy.

Printmaking required artists to distill the landscape into essentials. It rewarded bold contrasts and rhythmic organization. Many Kansas artists who could not afford oils or studio space turned to print as a democratic medium—accessible, reproducible, and suited to small-town exhibition. The aesthetic that emerged from this print tradition was graphic, flattened, and regionally grounded.

Sandzén’s work in this medium made its way into traveling shows, university collections, and national print societies. His prints, more than his large canvases, became the public face of Kansas regional art in the early twentieth century.

A Legacy Without a Doctrine

What Sandzén and the Lindsborg Circle left behind was not a doctrine, but a set of tools. Their approach to color, form, and subject matter influenced artists across the state, even those who rejected their style. The insistence that the Kansas landscape was worth painting—worth painting seriously—shifted the cultural ground. So did the model of an artist who could remain in Kansas and still engage a national audience.

The Birger Sandzén Memorial Gallery, opened three years after his death in 1954, stands as both archive and affirmation. It preserves the works, documents the career, and hosts exhibitions that continue to explore the intersections of Kansas, landscape, and modernism.

What emerged in Lindsborg was not a backwater imitation of East Coast trends, nor a nostalgic retreat. It was a legitimate artistic experiment, rooted in place, informed by Europe, and articulated in a distinctly regional syntax. The land was not symbolic. It was real. The style was not borrowed. It was built.

Chapter 6: The Prairie Print Makers — A Kansas Movement in Ink and Impression

A Society Without Pretense

In the fall of 1930, a small group of artists gathered in Lindsborg to form what would become one of the most quietly influential art organizations in the Midwest: the Prairie Print Makers. Unlike many artistic movements of the 20th century, they had no manifesto, no theory, and no ambition to break with tradition. They had a simpler goal—to promote fine art prints, make them accessible to the public, and support a fellowship of printmakers working in Kansas and beyond.

The founding members included painter-printmaker Birger Sandzén, illustrator and etcher Charles Capps, and a small circle of like-minded artists. They began by organizing traveling exhibitions and producing an annual gift print, distributed to members of the society. These prints—often modest in scale but high in quality—became tokens of shared purpose, circulated through the mail and collected in portfolios across the region.

What made the Prairie Print Makers unusual was not their radicalism, but their discipline. In a time of upheaval—economic, political, aesthetic—they offered constancy. Their prints were not gestures of rebellion; they were records of place, labor, structure, and craft.

Print as Democratic Medium

Etching, lithography, woodcut, and aquatint were the dominant techniques. The tools were portable. The editions were limited but affordable. A Kansas schoolteacher, storekeeper, or librarian could own a Charles Capps aquatint for a few dollars. The work was intended to circulate—not to reside exclusively in museums or private estates.

This emphasis on affordability and public access was not incidental. It was central to the group’s identity. In contrast to the gallery-centered model of New York or Chicago, the Prairie Print Makers envisioned a decentralized system of distribution. They sent exhibitions to libraries, colleges, banks, and art clubs. They collaborated with local institutions and sent their annual gift print to members across dozens of states.

In doing so, they built a different kind of network—quiet, durable, and inclusive. The art was not diluted by this accessibility. On the contrary, it often gained precision and clarity, constrained by the demands of the medium and the expectations of a broad, non-specialist audience.

Subjects Grounded in Place

Though the group included artists from across the country, many of its key figures lived and worked in Kansas or neighboring states. Their imagery reflects this grounding: grain elevators, fences, barns, rivers, train yards, courthouse squares, harvested fields, empty roads. These were not sentimental scenes, nor were they critical. They were observational—precise, balanced, and composed with an economy of means.

Artists like Capps and Norma Bassett Hall worked in aquatint and color woodcut to depict the structure of small-town life and the rhythm of the seasons. Sandzén, by contrast, brought his familiar color intensity and broken line to lithograph, expanding the expressive range of the medium.

In each case, the land was central. The prairie was not background—it was compositional field. Its horizontality informed the placement of forms. Its emptiness demanded clarity. Its subtle variations rewarded the eye.

This insistence on representing the familiar—not grand vistas, but recognizable places—aligned with the broader ethos of the group. They did not seek to astonish. They sought to last.

Technique and Restraint

Part of the strength of the Prairie Print Makers lies in their restraint. Where avant-garde movements of the same era experimented with fragmentation, distortion, and shock, these artists pursued balance, order, and clarity. Their work was rooted in observation and executed with technical care.

The techniques they favored required planning and skill. Etching involved hours of preparation, precise drawing, and chemical control. Lithography demanded attention to tonal layering. Woodcuts required decisiveness—each cut was irreversible. There was no indulgence in gesture, no tolerance for sloppiness. The medium resisted excess.

This discipline produced a visual language of calm intensity. In a Capps etching of a deserted grain elevator, the stillness is not passive. It’s charged with the weight of light and structure. In a Hall woodcut of a rural street, the shadows fall like geometry. These are not romantic images. They are architectural, rhythmic, precise.

A Movement Without Fame

The Prairie Print Makers never became a national sensation, and they did not try to. Their work circulated without headlines. Their influence spread through portfolios, personal collections, and institutional archives. For decades, their exhibitions appeared in towns that never saw contemporary painting or sculpture. They became, in effect, the art most people saw.

This lack of fame should not be mistaken for lack of ambition. The members of the group worked at a high standard. Their exhibitions were juried. Their print editions were limited and carefully produced. They corresponded with artists across the country, engaged with technical innovations, and contributed to national dialogues on printmaking.

But they kept their scale small, their values clear, and their operations rooted in the middle of the country.

Endurance in the Archive

The Prairie Print Makers continued to operate through the mid-20th century, formally disbanding in 1966. By that time, many of their key members had died or retired, and the art world had shifted decisively toward other media and models of production.

Yet their work endures. Major museum collections in Kansas and across the Midwest contain hundreds of their prints. University archives preserve correspondence, exhibition lists, and gift portfolios. Private collectors still trade their works in quiet circles.

More importantly, their ethos persists. In Kansas today, the idea that art can be serious, disciplined, regional, and widely shared still shapes how many artists work. The Prairie Print Makers demonstrated that excellence does not require spectacle, and that the smallest details—rendered carefully, distributed quietly—can define a movement.

Chapter 7: Murals, Monuments, and the Public Eye — Kansas in the New Deal Era

The Wall as Canvas

In the 1930s, as the United States struggled through the economic devastation of the Great Depression, the federal government launched an unprecedented series of programs to support employment and morale. Among them were the Federal Art Project (FAP) of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Section of Painting and Sculpture, later known as the Section of Fine Arts. These initiatives put artists to work—not in private studios, but in schools, post offices, courthouses, and other public buildings.

Kansas, like every other state, became a canvas. Murals appeared in small towns and county seats. Sculptures were commissioned for civic buildings. Painters and designers were paid to create work that would be seen daily by ordinary citizens, not gallery patrons. Art entered the public realm with both visibility and purpose.

The Logic of Location

Unlike museum pieces, these works were made for specific sites. A mural in a post office in Council Grove would depict a scene from the Santa Fe Trail. A painted panel in a courthouse in Chanute might show wheat harvests or livestock drives. The content was often idealized or instructional—regional history, agricultural labor, local industry. But the intent was civic: to affirm the value of place and to raise the visual standard of public life.

Artists had to win commissions through competition. Their designs were reviewed by committees, often revised in negotiation with local officials, and expected to be legible and inoffensive to the communities they served. This was not a platform for radical experimentation. It was a structure for public service.

And yet, within these constraints, artists found room for invention. The best Kansas murals of the New Deal period are not just illustrative—they are structurally sound, compositionally inventive, and attuned to the peculiarities of their settings. The wall becomes more than surface. It becomes part of the architecture of civic memory.

John Steuart Curry and the Kansas Capitol

The most famous, and most controversial, mural commission in Kansas during this period came not from the WPA but from the state itself. In 1937, John Steuart Curry—an artist born in Dunavant, Kansas, trained in Chicago and Paris, and celebrated for his depictions of rural America—was invited to paint murals for the rotunda of the Kansas State Capitol in Topeka.

What followed was a storm of public debate, artistic controversy, and political tension.

Curry’s central panel, Tragic Prelude, depicts abolitionist John Brown holding a rifle in one hand and a Bible in the other, flanked by scenes of tornadoes, prairie fires, and Civil War conflict. The figure of Brown is massive, wild-eyed, prophetic. The image is dramatic, almost apocalyptic—a vision of Kansas not as pastoral idyll, but as battleground.

The mural polarized viewers. Some saw it as an honest reckoning with the state’s history—violent, ideological, decisive. Others viewed it as grotesque, exaggerated, even offensive. Curry, frustrated by official resistance and a lack of institutional support, ultimately left the project incomplete. Yet Tragic Prelude remains one of the most recognized and debated works of public art in the state’s history.

It marked a turning point: the moment when Kansas art in public space became something more than decorative.

Regional Voices and Quiet Mastery

Beyond Curry, many lesser-known artists contributed to Kansas’s public art legacy in the 1930s and early ’40s. These included muralists like Lumen Winter, whose work The Pioneer Spirit in Saint Marys, Kansas, offers a softer vision of settler life, and Richard Haines, whose panel in the Wichita post office presents an orderly, muscular depiction of grain production.

These works, while less provocative than Curry’s, demonstrate strong design, careful draftsmanship, and an engagement with regional content. The constraints of the programs—modest budgets, limited time, local oversight—did not produce mediocrity. They produced discipline.

What these murals shared was a visual grammar of stability: centered compositions, clear figures, rhythmic repetition, and muted but harmonious color. They reflect a belief that public art should be comprehensible, affirmative, and dignified—even in hard times.

Sculpture and Monumental Form

Though painting dominated the New Deal commissions, sculpture also played a role. Works like the Mennonite Settler statue in Newton (1942), designed by Max Nixon and funded through the WPA, commemorate migration and agricultural labor. Cast in native stone, these works occupy thresholds: placed near railroad stations, courthouses, or parks, they stand as markers of identity.

These sculptures are not expressive in the modernist sense. They are upright, symmetrical, and emblematic. Their purpose is not introspection, but affirmation. They give shape to memory, asserting who belonged and what mattered.

In a state like Kansas—where distance separates communities, and where much of the built environment is functional rather than ornamental—such sculptures operate as visual centers. They gather attention. They remain.

Enduring Presence in Daily Life

Many of the New Deal-era murals and sculptures remain in place today. They are not always labeled. Some have been restored; others are fading. But they continue to function—quietly, steadily—as part of the visual environment of civic life.

For Kansans who pass them every day, they may seem unremarkable. But this very familiarity is part of their power. They represent a time when art was made for everyone, placed in spaces of shared purpose, and designed to endure.

These works—executed in post offices, courthouses, and schools—helped define what public art in Kansas could be: locally grounded, technically solid, and permanently visible. They belong not to movements or markets, but to place.

Chapter 8: Material and Method — Kansas Craft Traditions and Studio Practices

The Studio as Workshop

Art in Kansas has long included more than easel painting and formal portraiture. Across the state, especially in small towns and rural colleges, a parallel tradition has thrived: art as craft, studio as workshop, and object as functional form. Ceramics, textiles, woodworking, metalwork, and glassmaking have occupied a central if often overlooked place in the state’s visual history. These disciplines—sometimes dismissed as decorative or utilitarian—have in Kansas formed a durable foundation for both instruction and innovation.

This is not a subsidiary history. It is a coequal one. In many Kansas institutions, especially from the mid-20th century onward, the teaching of art began not with theory or abstraction, but with material: clay, fiber, wood, pigment, ink. The studio was a place to make, to repeat, to fail, and to refine. The hand led the mind.

In this setting, technique mattered. Craft was not seen as inferior to art—it was art.

Ceramics and the Language of Clay

Kansas has played a notable role in the development of American studio ceramics. The state’s abundance of natural clay, combined with the agricultural need for vessels and containers, produced a strong vernacular pottery tradition well before the studio movement gained traction nationally.

But by the 1940s and 1950s, this practical lineage began to merge with academic instruction and artistic experimentation. Universities like the University of Kansas and Wichita State developed robust ceramics programs that encouraged both utility and exploration. Influenced by Japanese techniques, American midcentury modernism, and the Bauhaus legacy, Kansas potters pursued formal rigor and tactile depth.

Studio ceramics in Kansas emphasized balance—between form and function, spontaneity and control, individual expression and craft tradition. Glazes were tested, kilns built, clay bodies modified to suit the demands of high fire or raku. The process was technical and meditative.

Many Kansas ceramicists worked in semi-anonymity, producing work for local sale or teaching generations of students who went on to studio practice or art education. Yet the standard was high. The idea that a bowl or jar could possess sculptural integrity, and that its surface could carry meaning, took deep root here.

Fiber, Pattern, and Regional Abstraction

Textile work—especially quilting, weaving, and embroidery—has a long history in Kansas, beginning with 19th-century settler culture and evolving into 20th-century formal practice. Quilts, initially made from necessity, became vehicles for aesthetic pattern and regional design.

By the mid-20th century, fiber arts were being taught in art departments, not just home economics classrooms. Pattern, repetition, and material choice became formal decisions. Artists explored the geometric logic of traditional quilt blocks—log cabin, flying geese, broken dishes—as abstract compositions. The boundary between craft and modernism blurred.

In studio settings, Kansas fiber artists began to expand beyond functional form. Weavings became sculptural. Embroidery became drawing. Fabric was painted, stained, burned, layered. The same qualities that had defined the state’s textile legacy—precision, durability, rhythm—now served as the basis for experimental work.

Yet the connection to older traditions remained visible. A quilt might hang in a gallery, but it still bore the trace of frontier hands and domestic invention. Kansas, with its long horizontal lines and history of self-reliance, had always understood the power of structure.

Printmaking and the Discipline of the Press

Printmaking in Kansas did not end with the Prairie Print Makers. The tradition evolved. In university studios and private workshops, etching presses and litho stones continued to provide space for experimentation grounded in process.

From the 1960s onward, Kansas printmakers expanded their techniques: silkscreen, photo-transfer, collagraph, and mixed media. The medium’s capacity for layering, repetition, and variation suited both abstract and representational impulses. Artists used the print not only to depict, but to build.

The state’s print shops became places of technical exchange. Visiting artists collaborated with master printers. Students learned registration, plate preparation, acid timing. Print portfolios circulated regionally, offering affordable access to original work. The ethos remained consistent: rigor, modesty, clarity.

In Kansas, the press was not a romantic tool. It was a machine of precision. It demanded planning, rewarded patience, and punished carelessness. Within that structure, artists found surprising freedom.

Sculpture, Wood, and Form Rooted in Use

Sculptural practice in Kansas often began in material traditions: woodworking, metal fabrication, stone carving. Many artists came to sculpture not through theory, but through shop class, farming tools, and architectural trades. This background produced a pragmatic approach to three-dimensional form.

Rather than monumental gesture, Kansas sculpture has frequently favored structure: repeated forms, modular construction, tension and balance. Materials were not exotic—steel, oak, limestone, wire—but they were treated with care. Surfaces were sanded, oxidized, bent, or joined with visible skill.

Public sculpture in Kansas towns and campuses often reflects this sensibility. Works are meant to be durable, legible, and responsive to their environment. They sit in wind. They endure sunlight and ice. The land does not permit fragility.

At the same time, studio sculpture has supported more abstract exploration. Artists have built forms that echo machinery, agricultural implements, and geological formations. The tension between organic curve and industrial structure defines much of the best sculptural work in the state.

Teaching the Hand, Honoring the Tool

What unites these diverse material practices—ceramics, fiber, print, sculpture—is their emphasis on process. Kansas studio culture, especially in the second half of the 20th century, cultivated an ethic of making that resisted both spectacle and theory-for-its-own-sake.

This ethos shaped instruction. Students were taught to respect tools, to repeat steps, to learn technique before commentary. The idea was not to suppress expression, but to anchor it. Craft was the condition for freedom.

Instructors who had trained in MFA programs on the coasts or abroad often brought sophisticated technique to Kansas but adapted it to local conditions: fewer resources, more teaching hours, pragmatic students. The result was a fusion of ambition and modesty—serious work made without pretension.

In this context, the studio became more than a site of production. It became a model of thought: material intelligence, structured risk, sustained attention.

Chapter 9: Urban Currents — Wichita, Topeka, and the Rise of City Art Scenes

Cities as Platforms, Not Destinations

Kansas is not often associated with urban culture, and its cities—by national standards—are modest in size. Yet Wichita and Topeka, along with smaller urban centers like Lawrence and Salina, have played a crucial role in the development of the state’s visual arts. These cities offered infrastructure: museums, galleries, schools, studios, and, at times, an audience. More importantly, they offered continuity—a way for artists to work seriously without leaving the region entirely behind.

These cities did not produce a dominant “Kansas modernism” or a singular urban aesthetic. What they did produce, over time, was a system of support: cooperative galleries, municipal funding, university ties, and the slow accumulation of reputational weight. In a state shaped by distance, the city functioned less as a cultural apex than as a network node—a place where things happened often enough to make them possible elsewhere.

Wichita: Industry Meets Art

Wichita’s economic base—aviation, oil, manufacturing—created both the wealth and the need for cultural ballast. In the early 20th century, the city became a regional hub not just for business, but for the arts. The Wichita Art Association (now Mark Arts) was founded in 1920 and served as an early center for instruction and exhibition. Its mission was civic rather than avant-garde: to foster public appreciation, provide instruction, and support local artists.

Wichita State University later developed one of the state’s strongest art departments, with emphases in printmaking, ceramics, and painting. The Ulrich Museum of Art, founded in 1974, added institutional weight, with a permanent collection that included major 20th-century American artists as well as Kansas-based work. The Martin H. Bush Outdoor Sculpture Collection placed serious contemporary sculpture throughout the campus, integrating art into daily urban movement.

Artists in Wichita moved between studio, classroom, and public space. Some taught by day and exhibited by night. Others worked for industrial firms or advertising agencies while pursuing independent practice. The line between professional artist and community participant remained deliberately permeable.

What emerged was not a school or style, but a rhythm: structured opportunity, modest ambition, and lasting infrastructure.

Topeka: Capitol and Cultural Center

Topeka, as the state capital, held symbolic importance, and its civic institutions reflected that status. The Topeka Public Library began collecting art as early as the 1930s, and the Topeka and Shawnee County Arts Council played an active role in sponsoring exhibitions, performances, and workshops. The Mulvane Art Museum at Washburn University, founded in 1924, became one of the earliest accredited art museums west of the Mississippi.

The Mulvane’s programming emphasized accessibility: regional exhibitions, educational outreach, and the integration of studio and gallery. It held works by Kansas painters, printmakers, and sculptors, but also made space for broader movements in American art. Its collections were chosen with a teacher’s eye: objects that could be explained, connected, and built upon.

Artists in Topeka were often hybrid figures: educators, muralists, illustrators, printmakers. They showed work regionally, occasionally nationally, but remained rooted in the institutions that sustained them. Many found steady employment through teaching or government commissions, and used that base to pursue work grounded in Kansas imagery—weathered buildings, fields, skies, and structural forms.

Topeka also offered public exposure. Murals, sculptures, and installations—especially those linked to state buildings—gave artists a civic audience. Art was not confined to gallery walls; it appeared in hallways, atriums, and courthouses, often encountered by people who had not sought it out.

Lawrence: University Gravity

Lawrence, home to the University of Kansas, combined small-town scale with academic energy. The Spencer Museum of Art, tied to the university, anchored the city’s art infrastructure, while the KU Department of Visual Art offered instruction in painting, sculpture, photography, and interdisciplinary media.

Lawrence attracted artists who sought the resources of a research university without the anonymity of a large city. Its gallery scene included both student-run spaces and independent venues, often focused on contemporary or experimental work. The city’s compactness encouraged collaboration: between departments, between disciplines, between faculty and town.

What distinguished Lawrence was its dual function: as a place for deep studio work, and as a place for testing ideas in public. Exhibitions often included lectures, panels, and publications. The academic model—discourse, revision, critique—bled into the city’s art life, producing a culture that valued both skill and context.

Though Lawrence lacked the commercial art market of larger cities, it made up for it with audience engagement. Openings were well attended. Shows were reviewed seriously. The dialogue was earnest, not performative.

Salina and the Power of the Regional Institution

Salina, a city of just under 50,000, became a surprising but important center for contemporary art with the founding of the Salina Art Center in 1978. The center emphasized contemporary work—sometimes regional, sometimes national—and paired exhibitions with educational programming and community initiatives.

Salina’s significance lies not in its scale, but in its intention. The Art Center treated art as part of civic life, not as an elite import. It supported artists in residence, commissioned new work, and organized shows that included installation, video, and nontraditional media.

By the 1990s, Salina had built a reputation for serious, contemporary programming—without abandoning local relevance. This balance made it a model for other regional institutions across the state and proved that contemporary art need not be urban, coastal, or high-budget to be credible.

Urban Art Without Urbanism

Kansas cities do not support a dense art market. There are few private galleries with national reach, and most artists rely on teaching, grants, or commercial design work to sustain practice. But the absence of a speculative market has also preserved a certain seriousness. Artists work without trend-chasing. Institutions exhibit without glamour. Studio practice remains tied to process, not persona.

In Wichita, Topeka, Lawrence, and Salina, the city does not eclipse the artist. It enables. It provides the space, structure, and occasional audience. In return, the artist gives form to place—without mimicry, without apology.

Chapter 10: Weather and Distance — The Kansas Sublime in Modern Landscape

The Scale of Sky

In most places, the sky is a ceiling. In Kansas, it is a wall.

Artists working in the state’s vast open terrain have long faced the spatial and atmospheric challenges posed by its geography. There are few natural barriers, few changes in elevation, few vertical interruptions. The horizon stretches in an uninterrupted line, and the sky dominates not just composition, but psychological weight. This dominance has shaped a distinct form of landscape art: austere, tonally rich, and formally compressed.

While earlier Kansas painters struggled to fit this landscape into the conventions of European pastoral or American picturesque, modern and contemporary artists embraced the peculiar extremity of Kansas space. They recognized that flatness was not a lack—it was an abundance of a different order.

The result is a body of work that treats weather, space, and distance not as backdrop, but as subject.

The Weather as Actor

Weather in Kansas does not play a supporting role. It asserts itself. Tornadoes, hailstorms, dust clouds, and lightning storms routinely cross the land in ways that seem almost choreographed—terrible and graceful at once. For artists, this produces not just dramatic visual material, but a continuous reminder of instability.

Painters such as Robert Sudlow, who taught for decades at the University of Kansas, built entire careers on depicting the subtleties of prairie light and atmospheric pressure. His canvases rarely contain figures or architecture. Instead, they show fields under shifting skies, tree lines bent in wind, roads fading into fog. The scenes are quiet, but never still.

Sudlow painted on site, often in remote locations, sometimes returning to the same view repeatedly under different conditions. His method was observational, but his results transcend mere depiction. The land in his paintings feels immense, not because it is filled with objects, but because it allows space to dominate. It is not the thing painted that holds attention—it is the distance between things.

Distance as Design

In Kansas landscape painting, the central compositional challenge is often what to do with nothing. A wide field, a straight road, a low sky—these elements defy conventional structure. There is no mountain to anchor the eye, no grove to interrupt the line. The artist must find ways to make space hold shape.

Many have done so by emphasizing formal rhythm: rows of crops, telephone poles, cloud banks. Others use color temperature to convey depth—cooler tones for distance, warmer for near. Some lean into minimalism, letting a single fence or ditch guide the gaze.

This compositional restraint has led to a distinctive regional aesthetic—pared down, frontal, and spatially ambiguous. The viewer is placed at the edge of vastness, not invited into it. The canvas becomes a surface of tension: between openness and control, between stasis and movement.

This logic extends beyond painting. Photographers working in Kansas—such as Larry Schwarm, known for his haunting images of prairie fires—use similar visual tactics. A single event (a fire line, a dust storm, a road disappearing) becomes the entire image, and its context is the void. The photograph becomes not a record, but an atmosphere.

The Sublime Without Spectacle

The traditional concept of the sublime in art—vastness, terror, awe—was often tied to dramatic scenery: cliffs, glaciers, oceans. Kansas offers a different version: slow, horizontal, and cumulative.

Its sublimity arises not from sudden drama, but from visual endurance. The repetition of lines, the slow accumulation of sky, the indistinct edge of weather systems—they create a kind of meditative immensity. Viewers are not struck by grandeur; they are drawn into quiet enormity.

Painters like Lisa Grossman, who has spent decades painting the Kansas River Valley, approach this scale with deliberate calm. Her works often focus on river bends, horizon breaks, and the subtle inflection of terrain. They do not shout. They hum. The sublime, in her hands, is not theatrical. It is persistent.

This quiet intensity defines much of the best modern and contemporary Kansas landscape work. It refuses sentiment. It avoids spectacle. It presents the world as it is seen: flat, open, and filled with variations that only attention will reveal.

Light as Subject

In Kansas, light does not just illuminate—it structures. The absence of mountains or forests means that changes in light are unmediated. Dawn breaks cleanly. Midday burns directly. Dusk stretches across the entire horizon. Storm light turns green, dust light turns amber, winter light casts no shadow.

Artists have long responded to this atmospheric volatility. For some, like abstract painter Keith Jacobshagen (raised in Wichita, later active in Nebraska), the prairie sky became almost a religion: vast, changing, and deeply ordered. His paintings often place a thin strip of land along the bottom edge of the canvas, giving three-quarters of the frame to sky. The land is necessary only to anchor the view.

This emphasis on light is not decorative—it is structural. It organizes the image. It gives time to space. And it forces a reorientation of artistic values: from form to tone, from detail to temperature, from object to field.

The Artist as Witness

In Kansas, the landscape does not invite ownership. It invites observation. Artists who choose it as subject do so with a kind of humility—aware that their work cannot encompass it, only register a moment within it.

This attitude has produced a lineage of artists who serve not as interpreters, but as witnesses. They do not render fantasy or escape. They show what is there, with as much clarity as the medium allows.

What emerges, over time, is a body of work that treats land as fact and weather as force. It is landscape painting without illusionism, photography without irony, abstraction rooted in terrain.

The Kansas sublime, then, is not a style. It is a condition: to stand before space and understand that what you see is only part of what is there—and that your job is not to explain it, but to face it.

Chapter 11: Kansas Modernists — Abstraction on the Plains

Not Quite a Movement

In the mid-20th century, as abstraction began to dominate the American art scene, Kansas artists responded with a quiet but durable strain of modernist painting and sculpture. They did not form a collective or announce a manifesto. Most were teachers, students, or studio practitioners working in cities and college towns. Their engagement with abstraction was serious, but it did not follow fashion. It grew from observation, material, and a restrained visual vocabulary shaped by the landscape around them.

Unlike their counterparts in New York or California, Kansas modernists rarely sought fame. Their ambitions were often pedagogical or regional: to refine a form, to push a surface, to see what could be done with paint, shape, or gesture in a context that did not demand novelty. This gave their work a particular clarity—rooted in discipline rather than noise.

It also gave it longevity. Many continued to work for decades, building bodies of work that now form a substantial, if still under-recognized, part of the state’s visual history.

Color, Field, and Structure

Among Kansas painters who explored abstraction seriously, the emphasis was often on color, structure, and edge. Their canvases avoided emotional excess or gestural drama. Instead, they favored careful composition, controlled surface, and a logic of internal relation.

Merrill Elam, based in Wichita for much of his career, created geometric abstractions that explored the tension between repetition and variation. His paintings often used a limited palette—grays, ochres, rusts—layered with precision. Shapes hovered in fields, not as objects, but as events within space.

In Lawrence, Robert Brawley shifted from precise realist painting to a more metaphysical kind of abstraction in his later years. While never fully non-representational, his works engaged deeply with form, atmosphere, and the poetics of absence.

These artists, like many of their peers, worked slowly. Their paintings do not proclaim. They reveal. Their visual logic is quiet, almost mathematical—concerned less with message than with structure. The result is a body of work that feels both rooted and open.

Sculpture as Geometry and Gesture

Kansas sculptors of the modernist period also found their own vocabulary—one that emphasized clarity of form and material intelligence. Many had backgrounds in carpentry, welding, or industrial design. Their work reflects this training: clean welds, balanced joins, surfaces that respect the nature of metal or wood.

James Sterritt, active in the 1960s and ’70s, produced welded steel works that combined biomorphic curves with architectural precision. His pieces often occupied outdoor spaces—unpainted, weathering with time, built to endure.

Others, like Lee G. Chesney, created smaller-scale works that blended hard-edged abstraction with organic suggestion. His bronzes, though modern in line, retained a sense of hand and weight.

These sculptors were not chasing minimalism in the New York sense. They were adapting the materials of their context—steel from rail yards, stone from the Flint Hills, oak from local mills—and bringing them into dialogue with modern form. Their restraint was not conceptual. It was regional.

Teaching Abstraction, Slowly

The strongest center for abstract art in Kansas was not a city, but a set of academic departments. Universities—especially the University of Kansas, Wichita State, and Kansas State—hired faculty who were trained in modernist methods and brought that sensibility into their teaching.

Many of these faculty artists produced substantial personal work, but they also built programs that emphasized material discipline and visual literacy. Students were taught to draw, paint, and sculpt with formal rigor. Abstraction was not a shortcut to sophistication—it was a practice that required as much technique as realism, and as much clarity as narrative art.

This emphasis produced a generation of artists who understood modernism not as rebellion, but as refinement. They explored surface, balance, and edge with patience. They worked in series. They returned to problems. Their work, while not showy, sustained itself over time.

Isolation as Discipline

Working in Kansas meant working without the distractions of a dominant art market or a pervasive critical culture. For some artists, this isolation was a disadvantage. For others, it was liberating. It allowed focus.

Painter Roger Shimomura, though best known for his later narrative work on identity and politics, began his career in Kansas with minimalist abstractions. He later noted that the environment allowed him to develop slowly, without the pressure to conform to coastal trends.

Many others echoed this. The prairie, with its long horizon and slow weather, created a kind of mental space in which abstraction could evolve organically. It did not have to be justified. It could be explored.

Abstraction Rooted in the Real

Even at their most formal, Kansas modernists rarely abandoned reference altogether. The land, the sky, the geometry of fields and towns—these remained latent in the work. A grid might recall a plowed section. A band of color might echo a storm front. A curve might suggest a grain bin, or a river bend.

This subtle grounding distinguishes Kansas abstraction from more doctrinaire modernist movements. It is less about purity, more about translation: from place to form, from weather to color, from silence to shape.

The best of these works do not declare their meaning. They hold it. And in doing so, they invite the viewer to look longer, slower, and with greater care.

Chapter 12: Continuity and Change — The Present and Future of Kansas Art

The Legacy Underfoot

Kansas art does not announce itself loudly, but it persists. The artists working today—whether in urban studios, rural garages, or university departments—carry forward a tradition that has always been more rooted than restless. They inherit not a style, but a sensibility: work that is measured, material, spatially aware, and serious in craft.

This continuity is not nostalgic. It is structural. Painters, printmakers, sculptors, and designers working in Kansas now do so with a kind of embedded memory—of workshops, landscapes, teachers, and civic forms that have shaped how and why art is made in this place. The past is not an archive. It is a method.

Contemporary artists do not replicate what came before, but they echo its rhythms: the horizontal logic of the land, the discipline of process, the refusal of spectacle for its own sake.

Institutions That Hold

The major art institutions of Kansas—many of them born in the early 20th century—continue to adapt, but they also continue to hold. The Spencer Museum of Art, the Mulvane, the Beach Museum, and regional centers in Salina, Lindsborg, and Wichita provide both permanence and flexibility. They preserve historical collections while hosting new work. They support both Kansas-based artists and national exhibitions.

Their strength lies not in trend-chasing, but in staying power. They are places where artists can exhibit without altering their work for market forces, and where students can see serious art without leaving the state. They maintain relationships—with artists, educators, and audiences—that are based on accumulation rather than turnover.

This institutional ecology allows a wide range of art to coexist: landscape painting next to conceptual installation, student portfolios next to master prints, heritage craft beside digital design.

Contemporary Makers and Thinkers

A new generation of Kansas artists continues to deepen and diversify the visual culture of the state. Some remain in familiar mediums—oil, stone, fiber, paper—but bring new subject matter or new formal questions. Others explore installation, sound, or environmental work, often rooted in local land use, weather systems, or vernacular architecture.

Multimedia artist Matthew Burke, who has taught at Kansas State University, creates sculptural installations using wood, graphite, and found materials that engage with both spatial memory and formal abstraction. Photographer Bryan Schutmaat, though not a Kansan by birth, has captured the rural Midwest with a visual sensitivity that echoes the tonal restraint of earlier Kansas photographers.

Artists like Tina Selanders in Salina and Shannon Trevethan in Emporia work in design and studio craft with a clarity of form that recalls the Prairie Print Makers—updated, but not undone.

Even those working in newer mediums—video, projection, augmented reality—often maintain the state’s visual ethic: understatement, attention to material, regional reference.

Art Without Illusion

The Kansas art world, such as it is, remains relatively uncommercialized. There are few major dealers, limited speculative buying, and almost no media machine to inflate value. While this can make national recognition difficult, it also grants artists a rare freedom: the freedom to work without performance.

In Kansas, a painting can be just a painting. A print can exist without an artist’s statement. A sculpture can stand outdoors, unattended, and earn its place over years rather than minutes.

This modesty is not weakness. It is a quiet refusal of affectation. It allows sincerity without naiveté. It lets artists speak plainly.

As a result, Kansas continues to produce art that is intellectually serious, visually grounded, and often personally rigorous—even when unseen by the national spotlight.

Education as the Endurance Mechanism

The single most durable force in Kansas art has been education. From Bethany College to the University of Kansas, from community colleges to public high schools, art instruction has been continuous and serious. Teachers pass down not just technique, but attitude: attention to process, respect for tools, patience in seeing.

Many artists teach. Many teachers make art. This cycle has produced multiple generations of practitioners who understand that making is thinking, and that seeing takes time.

As academic institutions adjust to changing demographics and budgets, the role of the art department remains critical—not just for those who will become artists, but for the health of visual culture itself. A student who learns to etch a plate or stretch a canvas, to critique a form or read a space, learns how to attend to the world.

The Future Is Not a Break

Kansas art will not be transformed by outside influence or disrupted by new media. Its changes will be internal, cumulative, and procedural. The next generation will not reject what came before. It will deepen it, question it, and repurpose it.

New tools will be adopted, but slowly. New subjects will be explored, but with restraint. The visual world will shift, but the ethic will remain: seriousness, clarity, rhythm, place. In this way, Kansas art continues—unhyped, unmannered, and unbroken.