The earliest visual languages of Greece emerged not from a unified state or cohesive tradition, but from the fragmented, sea-linked cultures of the Aegean archipelagos. These early civilizations—Cycladic, Minoan, and Mycenaean—developed in relative isolation and exchange, leaving behind artistic legacies that prefigure the monumental coherence of later Greek art. Their work is striking not for its classical perfection but for its raw invention, ritual intent, and startling modernity.

Abstract Forms and Marble Idols

In the scattered Cycladic islands, art begins as a quiet enigma. Between 3200 and 2000 BC, local communities carved marble into small, highly stylized female figures, often no taller than a foot. These so-called “Cycladic idols” present the human body in a radically reduced form: arms folded, legs together, nose sharply rendered but face otherwise blank. The torso is a flattened plane, the pubic triangle subtly marked. These objects, most found in graves, seem less like representations of individuals than archetypes—perhaps fertility figures, perhaps ancestors, perhaps something else entirely. Their abstraction, so precise and intentional, has fascinated modern artists from Brancusi to Picasso.

Though minimalist, these figures reveal considerable skill. Marble, abundant in the Cyclades, was carefully abraded with emery. Surviving traces suggest they were once painted: blue, red, perhaps even gold. In some cases, pupils were added, or tattoos, or garments. Yet even adorned, their silence is total. Cycladic art offers no clear narrative, no obvious symbolism. It resists interpretation and therefore compels it.

While funerary in context, these figures likely had lives before burial. Some show evidence of repair. Others were found in settlements or shrines. Their canonical posture—flat footed, arms folded—became a visual grammar passed between islands, signaling a shared aesthetic even among autonomous communities. This early abstraction laid the psychological groundwork for Greek art’s later tension between stylization and realism.

Palace Frescoes and Labyrinthine Grandeur

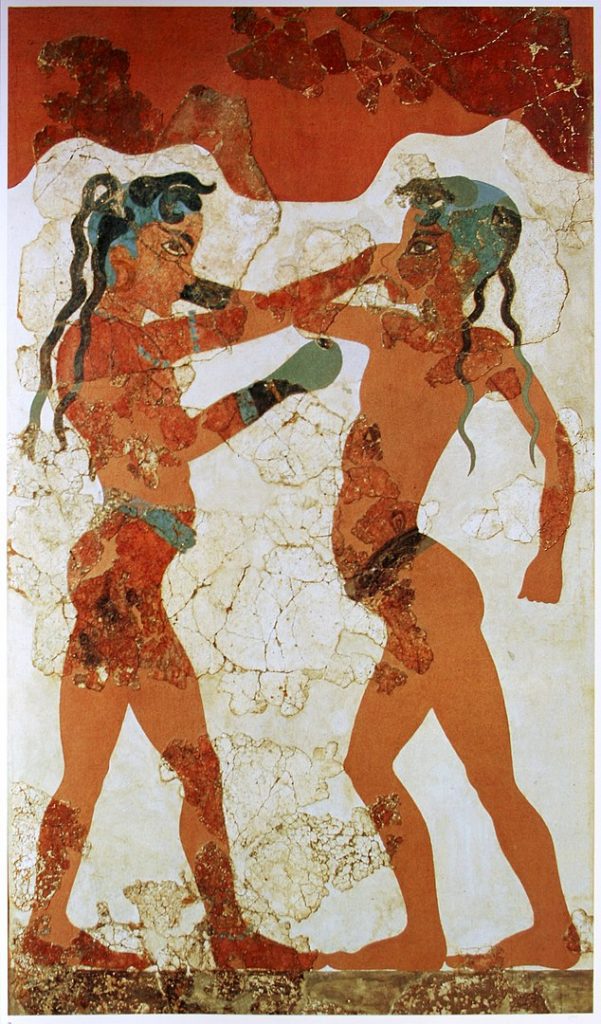

A more extroverted sensibility emerged in Crete, where the Minoans built sprawling palaces that served as administrative, religious, and residential centers. From around 1900 BC to 1450 BC, the Minoan world flourished in color, movement, and marine themes. At Knossos, Phaistos, and Zakros, walls were decorated with frescoes of leaping bulls, lilies, dolphins, and court processions. The art pulses with life. Unlike the static solemnity of Egyptian wall art, Minoan figures twist mid-stride, hair streaming, limbs airborne. Space is fluid, perspectives inconsistent, but gesture and rhythm dominate.

Frescoes were made with the buon fresco method—painting onto wet plaster—requiring speed and confidence. The colors were vivid: Egyptian blue, red ochre, yellow, black. One famous scene, the “Toreador Fresco,” shows youths vaulting over a bull in a sequence of elegant, impossible movement. Scholars debate whether this represents ritual, sport, or myth, but the aesthetic is unmistakable. These are not scenes of domination but of motion, of humans in dynamic relation to animals and environment.

Architecture mirrors this mobility. Minoan palaces—especially Knossos—are multi-storied, corridor-laced, and open to light. Columns taper downward, painted red or black. Central courtyards organize space without enforcing symmetry. There is no great temple in the Mesopotamian sense. Instead, shrines, stairwells, and storerooms interlace. This is not art as monument but as spatial drama. The myths of the labyrinth, the Minotaur, and Daedalus later reflect the architectural psychology of these complexes.

Three visual motifs dominate Minoan design:

- Marine life, especially octopuses and dolphins, painted with joyful naturalism.

- Floral patterns, such as lilies and crocuses, stylized but exuberant.

- Processional scenes, where anonymous figures in profile enact rituals or seasonal rites.

Objects were also richly made: rhyta (ritual vessels) shaped like bulls’ heads, faience figurines of snake goddesses, and delicate goldwork. The Minoans embraced elegance and sensuality, but their art was eventually overtaken—whether by conquest or catastrophe—by the Mycenaean mainlanders.

Death Masks and the Heroic Afterlife

The Mycenaean civilization, centered in the Peloponnese from around 1600 to 1100 BC, brought a heavier, more militarized tone to Aegean art. Where Minoan design emphasized fluidity, Mycenaean style is defined by fortification. Their citadels—Tiryns, Mycenae, Pylos—rose atop hills, encircled by cyclopean walls of massive stone blocks. Architecture became declaration: of power, endurance, defense.

Tombs, however, were the most elaborate structures. The tholos tomb—an underground beehive dome, approached by a dramatic passageway—became the ceremonial heart of Mycenaean burial. Inside, grave goods signified rank and memory: gold masks, weapons, jewelry, ceremonial cups. The most famous artifact, the so-called “Mask of Agamemnon,” discovered by Heinrich Schliemann in 1876, is a hammered gold face—eyes closed, mustache prominent—intended to preserve the features of a noble warrior in death. Whether it actually belonged to Homer’s legendary king is doubtful. But its creation speaks to a culture that memorialized heroism in form and material.

Mycenaean painting, though less refined than Minoan, retained elements of courtly display. Wall frescoes depict chariot scenes, hunting, and siege warfare. Pottery became more geometric and less naturalistic. Scenes began to tell stories of struggle, hierarchy, and divine sanction. If Minoan art danced, Mycenaean art stood its ground.

The Mycenaeans were not immune to the past: they adopted Minoan writing (Linear B), imagery, and even religious iconography. Yet they transformed it. Snake goddesses became martial goddesses. Fluid marine motifs hardened into regular, schematic designs. Their world was less open, more controlled, and ultimately more fragile. Around 1200 BC, Mycenaean palaces burned. The great centers collapsed, initiating the Greek Dark Ages.

But in the ashes, continuity endured. Burial customs, mythic themes, and certain artistic tropes persisted. The mask, the bull, the labyrinth—all would survive in later Greek narrative and visual art. What began as marble abstractions, seaside murals, and tomb effigies would evolve, over centuries, into the structured, philosophical, and humanist traditions that defined the Greek artistic ideal.

The origins of Greek art are not a prelude but a set of parallel visions—silent, rhythmic, heroic—that would echo through millennia.

The Geometric Period: Order, Pattern, and Proto-Narrative

In the centuries following the collapse of the Mycenaean palatial centers, Greek art did not disappear—it recalibrated. Between roughly 900 and 700 BC, in what is often termed the Geometric Period, artists working in a world stripped of monumental architecture and royal patronage began reassembling visual language from elemental parts. The result was a body of work at once austere and exploratory: vases covered in linear motifs, funeral scenes rendered in sticks and triangles, horses drawn as pairs of crescents and columns. It was art rethinking itself from scratch.

Vessels of the Dead and the Power of Repetition

The Geometric style emerged from the potter’s wheel, not the sculptor’s chisel. Large ceramic vessels—especially amphorae and kraters—became primary surfaces for artistic innovation. These were not household wares but grave markers, placed above burials or used in funerary rites. The Dipylon Cemetery in Athens yielded many of the most important examples: towering vases, some over five feet tall, covered top to bottom in meanders, cross-hatching, concentric circles, and rows of human and animal figures reduced to strict geometry.

The organization of surface was absolute. Horizontal bands divided the vase into registers; within each, the decoration obeyed internal logic. The lower bands might carry nothing but key patterns, swastikas, zigzags. The uppermost register, however—typically the neck or shoulder—held figural scenes, and here a new kind of storytelling began to emerge.

Most famous is the Amphora of the Dipylon Master, circa 750 BC. At its center is a prothesis, a laying-out of the dead: a stylized corpse lies on a bier, flanked by mourners raising their arms in grief. The figures are schematic—triangle torsos, dot eyes, no facial features—yet the emotion is legible. Horses and chariots march in procession. Beneath these scenes are repeated bands of meanders, creating a visual tension between life’s fragile particularities and the unrelenting continuity of pattern.

Repetition, in Geometric art, is never mindless. It disciplines the viewer’s eye, stabilizes the surface, and defines the frame for narrative to break through. It also evokes ritual. Like a chant or lament, the decoration repeats with variations, always returning to form. In a world without cities, kings, or temples, the pot became monument, vessel, story, and grave all at once.

Emergence of Human Forms in Pottery

As the Geometric period progressed, artists pushed the limits of abstraction. By the mid-8th century BC, human figures began to multiply and interact more dynamically. The warrior became a central figure: shield-bearing, helmeted, often mounted on horses whose legs are drawn in profile but bodies face forward. Battles, hunts, and chariot races appear in rhythmic progression, their protagonists anonymous yet archetypal.

One striking development was the use of silhouette. Instead of internal detail, figures were filled in black, becoming part of the pattern while remaining distinct. Limbs extend mechanically, heads rendered as circles or ovals with pointed noses. Yet these forms begin to suggest motion, intent, even hierarchy. The eye adapts to the code: an upraised arm is a cry, a horizontal body a corpse, a two-wheeled cart a symbol of nobility or transit.

Among the most important innovations were:

- Processional narratives, such as warriors departing by ship, rowers bent in rows beneath curling waves.

- Funerary combats, where hero and enemy clash in symmetrical combat, often around a central axis.

- Animal friezes, stylized lions, deer, and birds forming ornamental belts around the vessel body.

Despite their flatness, these scenes mark the return of narrative to Greek art. They do not yet depict myth in a literary sense, but they show actions, reactions, and events with implied sequence. One famous krater shows a centaur—Chiron or Nessus?—wounded in the back, pursued or fleeing. Mythic forms were re-entering the visual field, even if myth itself had not yet hardened into canon.

This shift toward storytelling coincided with political and social reorganization. Greece in the 8th century saw the reemergence of city-states, known as poleis, and with them, new forms of collective identity. Art began to serve civic as well as familial or tribal functions. Public cemeteries like the Kerameikos and Dipylon became sites of visual culture as much as memory. The pot was not just a tomb marker—it was a public statement about lineage, virtue, and loss.

Athens at the Threshold of Mythic Visualization

Nowhere was the Geometric style more dominant—and more fully developed—than in Athens. Athenian potters set the standard in both form and iconography. Their monumental vases became export goods, found as far away as Sicily and the Levant. But the internal evolution of style in Attica also reveals the slow return of mythology, not as abstraction but as drama.

Toward the end of the 8th century, scenes appear that seem to reference specific narratives. On one amphora, a man wrestles a lion; on another, two warriors flank a central figure who may be a hero. These are not generic episodes—they begin to fix characters in roles. The outlines of Homeric epic, whether from oral tradition or emerging poetic form, begin to haunt the ceramic surface.

An especially telling image occurs on a krater attributed to the so-called Hirschfeld Painter: a funeral procession is rendered in full, with chariots, horses, pallbearers, and keening mourners. But hidden among the patterned figures is an unusual motif—two small men wrestling over a tripod. This could be a reference to the quarrel between Herakles and Apollo, a rare intrusion of mythic specificity into otherwise ritual imagery. The integration is tentative but deliberate. The potter begins to see his surface not only as a space for pattern but as a field for meaning.

This moment of artistic inflection corresponds with the broader reawakening of Greek culture. By 750 BC, writing reemerged using the Phoenician alphabet, adapted into Greek phonetics. With writing came names, with names came narrative, and with narrative came image. Art did not merely reflect this shift—it enacted it.

In the Geometric period, Greek artists learned again how to see. They practiced vision through repetition, shaped memory in abstraction, and hinted at myth before daring to show it. Their work is demanding, austere, even cold at first glance. But within those concentric circles and marching stickmen lies the quiet forge of an artistic tradition that would soon overflow with gods, warriors, monsters, and mortals in all their tangled glory.

The Orientalizing Period: Hybrid Creatures and Foreign Influences

In the century between 700 and 600 BC, Greek art entered a period of abrupt transformation. The geometric clarity that had dominated ceramics and sculpture for over a hundred years began to soften, open, and absorb. New motifs arrived from the East: sphinxes, griffins, rosettes, and palmettes; narrative scenes thickened with layered action; bodies became fleshier, more contoured, more animated. This was the Orientalizing Period, so named not for any direct political conquest or colonization, but for a broad influx of aesthetic ideas from the older civilizations of the Near East and Egypt into the Greek world. The result was not imitation but fermentation. Greek artists reoriented their visual language, creating a hybrid style that foreshadowed the mature realism of the Archaic and Classical ages.

The East Arrives in the West

This stylistic shift was not an artistic whim but a byproduct of widening horizons. Trade routes had expanded. Greek merchants and mercenaries moved through Cyprus, Syria, and Egypt; Eastern craftsmen arrived in ports like Corinth, Chios, and Rhodes. Ivory, metalwork, and faience crossed the Aegean. With these goods came ideas—forms, patterns, creatures, and entire systems of ornamentation developed over millennia in Assyria, Phoenicia, and Egypt.

Corinth, with its powerful harbor and strategic location, became a critical point of exchange. By the mid-7th century BC, its potters pioneered a new technique known as black-figure painting, which involved painting figures in a glossy slip that turned black during firing, then incising details into the surface. This allowed for far greater control over line and texture, enabling artists to develop more elaborate narrative scenes. At first, however, the subject matter remained decorative, dominated by animals and composite beasts drawn from Eastern models.

The so-called “Animal Style”—found especially on Corinthian aryballoi (small perfume vessels)—features horizontal friezes of lions, panthers, birds, and mythical hybrids, separated by filler motifs like rosettes and checkerboard patterns. These were not local fauna. The lion, for instance, was not native to Greece. Its appearance on pottery in this period suggests not observation but symbol: a creature associated with kingship, danger, and the prestige of the East.

At the same time, the technique of metal inlay and repoussé—shaping and decorating metal by hammering from behind—arrived via imported bronze works. Greek smiths adopted these techniques to create elaborate shields, fibulae (brooches), and drinking vessels. This foreign technology influenced even stone sculpture, as the desire to emulate the luster and dimensionality of metal transformed how artists conceived of surface and depth.

What mattered most in this cross-cultural moment was not fidelity to foreign styles, but their re-interpretation. The Greek artist did not merely copy the sphinx—he made it Greek.

Daedalic Sculpture and the Early Nude

Sculpture, which had remained mostly abstract during the Geometric period, underwent a comparable awakening. The new form that emerged is known as Daedalic, a name drawn from the mythical inventor Daedalus, though it refers to no specific individual. The style is marked by a rigid frontal stance, triangular face, wig-like hair, and an emphasis on patterned surface. Yet these early stone figures—usually female, clothed, and standing stiffly—represent a major leap forward in anatomical thinking.

The canonical Daedalic kore (maiden) features a flat body, a narrow waist, and a high belt, with long hair cascading in stylized strands. The features are symmetrical, schematic, and mask-like, but they now inhabit a physical volume. The figure is no longer a glyph or symbol but a body with presence, weight, and implied life.

Sculptors began experimenting with scale and function. Limestone statues served as votive offerings in sanctuaries, especially at Delphi and Olympia. Others marked graves or honored civic patrons. One notable example, the Lady of Auxerre (circa 640 BC), carved in limestone and originally painted, holds her hand to her chest in a gesture that may indicate prayer or modesty. Her face is abstract, but her proportions are controlled, and her gaze—wide and direct—commands attention.

The male form also began to appear, particularly in the early kouros statues: nude, youthful figures standing with one foot forward and arms at the side. Though kouroi become dominant in the Archaic period, their roots are here, in the Daedalic impulse to make the body the central subject of Greek sculpture.

This return to figuration was not merely technical—it reflected a shifting cultural emphasis on individuality, heroism, and the representation of the human form as a worthy subject in its own right. The nude, which in Egypt was reserved for children, servants, or captives, was reimagined in Greece as a symbol of virtue, youth, and divine favor.

Lions, Sphinxes, and the Greek Imagination

If one creature can symbolize the Orientalizing moment, it is the sphinx. Imported from Egyptian and Near Eastern iconography, the sphinx in Greek art took on distinctive traits: a female head, a lion’s body, and wings. She appeared not as a guardian of tombs but as a creature of riddles and death. By the end of the 7th century BC, the sphinx had entered Greek mythology with force—most famously in the tale of Oedipus—and began appearing in temple pediments, bronze vessels, and painted vases.

The Greek reimagining of such creatures was not decorative alone. It was speculative. Artists absorbed the grotesque hybrids of Mesopotamia—the lamassu, griffin, and chimaera—and rendered them with increasing narrative potential. These were not marginal beasts. They began to populate myths, inhabit stories, serve gods. The world of Greek art was no longer confined to the human and the geometric—it was now monstrous, divine, and rich with possibility.

This transformation reached its height in proto-Attic pottery, a regional style from Athens and Eleusis. These large vases, such as the Eleusis Amphora (circa 675–650 BC), illustrate full-blown mythic scenes: Perseus beheading Medusa, Odysseus blinding the Cyclops. Figures remain somewhat schematic, but their gestures, props, and interactions are narrative in intent. This is not pattern—it is story.

The Eleusis Amphora, used as a child’s burial urn, places the headless body of Medusa at the bottom of the vessel, her sisters chasing Perseus around the curve of the pot. The Cyclops Polyphemus, with his huge central eye, is shown surrounded by Odysseus and his men in violent engagement. For the first time in Greek art, myth becomes both content and structure. The vase is no longer just a grave marker or a domestic object—it is a theater of memory and imagination.

This new mode of visual storytelling coincided with the growth of sanctuaries, the codification of the Olympic gods, and the emergence of the Homeric epics in written form. Art, poetry, and religion began to harmonize. The human body, the divine figure, and the hybrid beast all became legible players in a shared narrative world.

The Orientalizing period did not last long. By 600 BC, its motifs had been digested, its foreign sources naturalized. But its impact was permanent. It gave Greek art a larger stage, a richer visual lexicon, and the courage to depict bodies in motion, gods in form, and myths in action. It laid the foundation not just for the Archaic smile, but for the entire visual intelligence of Greek art to come.

Archaic Greece: Kouros, Kore, and the Smile of Stone

Between roughly 600 and 480 BC, Greek art entered a new epoch marked by increasing formal confidence, material ambition, and emotional poise. Known as the Archaic period, this was the age when stone sculpture became monumental, temple architecture took definitive form, and human figures emerged from symbolic rigidity into a semblance of natural presence. The era did not merely inch toward realism—it explored what it meant to depict the human body as a bearer of ideals, virtues, and roles within the polis. The kouros and kore—nude male and clothed female statues—stood at the center of this evolution, both as artistic experiments and as cultural instruments.

The Rise of Monumental Free-Standing Sculpture

One of the most revolutionary developments in Archaic art was the widespread adoption of monumental free-standing sculpture in marble. Though earlier figures in stone existed, the kouros and kore now became common across the Greek world—from Attica and the Cyclades to Ionia and the Peloponnese. These were not portraits but symbolic figures: youths, maidens, gods, or votive stand-ins, idealized and often anonymous.

The kouros—a striding nude male youth—derives its basic stance from Egyptian prototypes: left foot forward, arms at the sides, eyes fixed straight ahead. But where Egyptian figures were embedded in blocky supports or tightly integrated with architectural settings, the Greek kouros stood free, cut entirely away from the stone. This independence gave it a new presence. The body was open to the viewer, not enclosed. Its surfaces were smoothed and stylized, the anatomy generalized yet emphatic: defined pectorals, linear abdominal grooves, rounded knees, and formalized hair cascading in bead-like locks.

Perhaps the most famous early example is the New York Kouros (circa 600 BC), discovered near Attica. Though rigid and schematic, it demonstrates a leap in scale and polish. The figure stands over six feet tall and exhibits a frontal dignity that was both devotional and declarative. These statues were typically used as grave markers or dedications to gods—particularly Apollo—and their sheer physicality made them declarations of social and religious stature.

Alongside the kouros stood the kore, his female counterpart. Unlike the nude male, the kore is always clothed, often elaborately so, and stands with one hand at her side or offering a gift, while the other lifts her skirt or extends forward. These figures are less about athletic ideal and more about piety, grace, and civic virtue. The Peplos Kore (circa 530 BC), now in the Acropolis Museum, wears a fitted garment and once bore vivid paint and metal jewelry. Her eyes are almond-shaped, her mouth curled in the so-called Archaic smile—a feature that animates many figures of this period, more a convention than an emotion, but suggestive of alertness and life.

These figures, initially stylized, became increasingly refined. Musculature became more plausible, weight distribution more believable. In later kouroi such as the Anavysos Kouros (circa 530 BC), we see a decisive shift: the body no longer feels etched from memory but observed from life. The statue honors a fallen warrior named Kroisos, and while it is still idealized, it shows swelling forms, subtle asymmetries, and a growing sensitivity to bodily presence. The smile remains, but now it sits upon lips that seem shaped by muscle and breath.

Painted Temples and Architectural Color

While kouros and kore commanded attention as individual figures, the architectural setting in which they appeared underwent its own radical development. This was the period when temple architecture reached maturity, most notably through the Doric and Ionic orders. Temples became not just homes for the gods but civic symbols—visual declarations of a city’s piety, wealth, and artistic ambition.

The Doric temple, with its sturdy fluted columns and simple capitals, emerged first on the Greek mainland. Temples such as the Temple of Hera at Olympia and the Temple of Artemis at Corfu show a clear logic of form: colonnaded perimeters enclosing an inner sanctuary (naos), often built on a stepped platform (stylobate). Yet these structures were anything but monochrome. Contrary to modern expectations, Archaic temples were brightly painted. Friezes, pediments, and even the columns were often colored in red, blue, and gold. This polychromy extended to sculpture as well—kouroi and korai were originally painted in lifelike hues, their eyes accented, their lips crimson.

The Ionic order, which emerged from the Aegean islands and the coast of Asia Minor, brought a more ornate sensibility. Columns were slimmer, bases more elaborate, capitals adorned with volutes. Temples in Ionia, such as the Temple of Hera at Samos, employed longer, narrower proportions and continuous friezes instead of isolated triglyphs and metopes. The Ionic style often emphasized narrative more explicitly, inviting sculptors to populate their architecture with detailed mythic episodes.

Pediments, the triangular spaces above temple façades, became theaters of mythic display. The Temple of Artemis at Corfu, for instance, features the gorgon Medusa flanked by panthers and smaller narrative scenes. The figures do not fit neatly into the triangle—they sprawl, contract, or tilt awkwardly—but the visual ambition is clear. This was sculpture meant to astonish: gods in action, monsters leaping, forms filling every inch of space.

Color, scale, and composition combined to create an immersive environment. The viewer approaching such a temple encountered not a solemn ruin but a kaleidoscope of sacred storytelling—painted figures, flickering light, and the interplay of sculpted and architectural rhythm.

Archaic Expressions of Identity and the Divine

The Archaic period saw not only the formal evolution of sculpture and architecture but also the growing integration of art with civic and religious identity. Kouroi and korai did not stand alone—they were placed in sanctuaries like Delphi and Olympia, on the Acropolis of Athens, or at city gates and public cemeteries. Each bore a message. They commemorated citizens, appeased gods, honored victories, and visualized ideals.

Inscriptions at the base of these statues often named the donor, the sculptor, or the deceased. One kouros might read: “Stop and mourn at the tomb of Kroisos, dead in battle, whom raging Ares destroyed.” Another kore might declare her dedication to Athena. The individual was immortalized through the ideal, the particular body through a generalized form. This tension—between self and type, between realism and idealism—would remain central to Greek art for centuries.

Archaic artists also began to develop signatures and styles. Regional workshops emerged: the sculptors of Naxos, the potters of Corinth, the bronze workers of Argos. Innovation often came through competition. At Panhellenic sanctuaries, cities erected treasuries, statues, and victory monuments in visual rivalry. A visitor to Delphi might walk past bronze charioteers, gold-leafed columns, and marble kouroi, each inscribed with civic pride. Art became a vehicle not just for devotion but for prestige.

Myth and religion, meanwhile, saturated artistic subject matter. Vase painting of the period—particularly in Athens—depicted Heracles wrestling lions, Theseus confronting the Minotaur, and gods dining on Olympus. Yet even these scenes were shaped by Archaic conventions: balanced compositions, patterned garments, and the omnipresent smile. The divine was made legible through form and rhythm, not psychological complexity.

That smile—the Archaic smile—has drawn fascination and debate. Is it meant to express contentment? Serenity? Simply life? Scholars now tend to see it as a formal device, an early attempt to soften the hardness of stone and suggest the potential for speech, breath, and emotion. It does not laugh, but it lives.

By the end of the Archaic period, around 480 BC, Greek art stood on the cusp of a new realism. The Persian Wars had begun to transform political consciousness, and artists like the sculptors of the Kritios Boy began to tilt the body subtly, break the frontal plane, and introduce genuine contrapposto. Yet the achievements of the Archaic age remained foundational. It was the period when the human form became a vehicle for truth, when myth found monumental shape, and when cities learned to speak through marble, pigment, and stone.

The Classical Ideal: Harmony, Proportion, and the Human Body

The defeat of the Persian invasion in the early 5th century BC did more than preserve the independence of the Greek city-states—it sparked a profound transformation in the visual arts. In the aftermath of war, amid rising political ambition and cultural confidence, Greek artists forged what would become the central aesthetic paradigm of Western art: a vision of the human body as ordered, balanced, and fully integrated into space. The Classical period, spanning roughly 480 to 323 BC, witnessed a crystallization of form that went beyond technical mastery. It sought a kind of moral geometry—beauty as an expression of inner equilibrium, civic virtue, and cosmic law.

Polykleitos and the Canon of the Male Nude

No figure better embodies the Classical obsession with measured perfection than Polykleitos of Argos, a sculptor active in the mid-5th century BC. His lost treatise, known as the Kanon, laid out precise mathematical ratios for the ideal male body, which he put into practice in a now-lost statue known as the Doryphoros (Spear Bearer), known today only through Roman copies.

The Doryphoros stands in perfect contrapposto: weight on the right leg, the left relaxed; shoulders tilted opposite the hips; one arm bent, the other hanging. The body flows from tension to ease in a rhythm that feels both natural and composed. Muscles are defined but not exaggerated, features even, the expression reserved. This is not a portrait but a theory in flesh—man as measure, ideal, and moral actor. The body, in this vision, becomes a site of ethical structure. Balance and moderation, cardinal virtues of Classical Greece, are inscribed directly into the pose.

Contrapposto was more than a technical innovation—it was a visual argument. The human figure, once rigid and frontal in the Archaic kouros, now turned, breathed, and occupied three-dimensional space. The viewer was invited to move around it, to sense the shifting geometry from every angle. In this sense, the Classical nude became a medium of philosophical speculation: What does it mean to be in harmony with oneself? How does a single body express both stillness and motion?

While Polykleitos defined the masculine ideal in bronze, other sculptors expanded the expressive possibilities of marble. Myron’s Discobolos (Discus Thrower), though also known through Roman copies, captures a fleeting moment of athletic exertion, frozen in a perfect arc. Yet even in this dynamic pose, balance and symmetry are maintained. The action serves form, not drama.

These works were not isolated monuments—they were part of a civic and ritual landscape. Statues of victors at Olympia, dedications in Delphi, processions in Athens: all served to embody public ideals in physical form. In Classical Greece, art became a medium through which a city expressed its values—courage, restraint, symmetry, justice—not only in stone and bronze, but in the very postures of its heroes.

The Parthenon and Its Sculptural Program

Nowhere was this civic-aesthetic fusion more complete than in the Parthenon, the great temple to Athena that crowned the Athenian Acropolis. Built between 447 and 432 BC under the statesman Pericles and designed by the architects Iktinos and Kallikrates, it housed a colossal gold-and-ivory statue of the goddess by Pheidias, whose influence would define the age. But it was the temple’s external sculptural program—its metopes, frieze, and pediments—that turned architecture into narrative spectacle.

The metopes, set high above the outer colonnade, depicted mythic battles: Greeks versus Amazons, Lapiths against centaurs, gods against giants. These conflicts were not random—they allegorized the moral struggles between order and chaos, civilization and barbarism. The centaurs, with their mix of human reason and animal savagery, became symbols of excess and violence, subdued by poised Athenian heroes. The drama was real, the violence clear, but the forms remained idealized—every muscle perfectly rendered, every gesture choreographed for clarity and impact.

The pediments, the triangular gables at each end of the temple, portrayed the birth of Athena from the head of Zeus and her contest with Poseidon for dominion over Attica. These scenes, once vividly painted, arranged figures in a careful crescendo from reclining gods at the corners to central action at the peak. The East Pediment in particular, though fragmentary, remains a masterpiece of narrative arrangement and anatomical realism. The so-called Three Goddesses group—possibly Hestia, Dione, and Aphrodite—shows marble drapery so finely carved it clings and billows like wet cloth, revealing and concealing the body beneath.

But it is the inner Ionic frieze, a continuous band running around the cella, that offers the most striking innovation. This 160-meter-long procession is widely interpreted as a stylized version of the Panathenaic Festival, Athens’s own civic-religious celebration. It includes over 300 human and divine figures: horsemen, musicians, elders, maidens, sacrificial animals. There is no battle here, no mythic climax—just the rhythm of a pious city at ritual attention. For the first time, a temple told not just the stories of gods, but the story of a people: Athens glorified through its own harmonious order.

Contrapposto, Realism, and Athenian Civic Pride

The full flowering of Classical sculpture was inseparable from the ethos of Athenian democracy, particularly in the decades following the Persian Wars. While the city became increasingly imperial—exacting tribute through the Delian League—it also projected an image of unity, balance, and reason. The body became the medium through which this ideal was expressed.

Athens’ civic pride manifested in countless ways: in the placement of victory monuments on the Acropolis, in public statues of military generals and benefactors, and in the state-sponsored dramatizations of history and myth on pottery and temple walls. Even funerary art, as seen in stele (grave markers), reflected this emphasis on composure and restraint. One striking example from the Kerameikos cemetery shows a young woman seated, gazing calmly at her maidservant. Death here is not rupture but quiet dignity—memory made permanent in balanced form.

Painters, too, embraced this Classical clarity. The red-figure technique, perfected in the early 5th century, allowed for greater anatomical precision and expressive range. Artists like Douris and Makron depicted symposiums, courtship, and myth with elegant line and refined gesture. Their figures are elastic, informed by a deep study of musculature and posture, often shown in complex foreshortening that anticipates Hellenistic illusionism.

What surprises, however, is not the uniformity of this ideal but its adaptability. Sculptors like Praxiteles, working in the later Classical period, introduced softness, sensuality, and intimacy. His Aphrodite of Knidos (circa 350 BC), the first full-scale nude female statue in Greek art, presents the goddess not as an untouchable abstraction, but as a body preparing for a bath, modest yet aware of the gaze. The statue was so celebrated that entire pilgrimages were made to view it.

By the time of Alexander the Great’s rise, Classical art had achieved its philosophical goal: the fusion of ideal and real, public and personal, god and man in a single visual grammar. The sculptures and temples of this period do not merely show bodies—they think with them. They measure desire, discipline, power, and virtue in stone.

The Classical ideal, for all its precision and control, was never static. It pulsed with moral energy, civic purpose, and deep curiosity about the limits of the visible. It made the human body not only a subject for art but a language of form through which an entire culture defined itself.

Painters and Potters: The Ceramics of Classical Greece

While marble and bronze sculpture captured the grandeur of Classical ideals in civic and religious settings, it was painted pottery that brought Greek myth, ritual, and daily life into homes, symposiums, and graves. Pottery was omnipresent—used for storage, transport, ritual, and display—and its painted surfaces formed an encyclopedic visual record of Greek society. Between 500 and 400 BC, Athenian potters and painters produced some of the most refined ceramics in world history. Their work fused technical mastery with narrative invention, creating a genre where form, function, and myth became inseparable.

Black-Figure Technique and Heroic Narrative

Though developed in Corinth in the 7th century BC, the black-figure technique reached its artistic peak in Athens during the late Archaic and early Classical periods. In this method, figures were painted with a glossy clay slip that turned black during firing, while details were incised into the surface, revealing the red clay beneath. Additional colors—white and red—were applied to highlight clothing, hair, or skin tones.

The technique imposed limits: silhouettes were flat, and detail could only be added through incision, not brushwork. But Athenian painters turned these constraints into strengths, developing a stylized visual language that emphasized rhythm, clarity, and symbolic pose.

One of the greatest exponents of the style was Exekias, active around 540–520 BC. His amphorae are visual masterpieces of narrative compression. In his most famous piece, Achilles and Ajax Playing a Game, the two heroes, seated in full armor, lean over a board, spears in hand, speaking the numbers they’ve rolled. The moment is quiet, intimate, and almost tender—a scene of pause before battle. Yet beneath this serenity lies tension: both men will die at Troy. The vase captures not only a mythic episode but a moral tone: the inevitability of fate, the nobility of friendship, the fragility of peace.

Black-figure pottery thrived on scenes of:

- Heroic combat, such as Heracles’ labors or Theseus’ adventures.

- Gods and rituals, often showing Dionysian feasts, satyr plays, or sacrifices.

- Funerary processions, with mourners and chariots in stately rows.

These images were not simply illustrations—they were interpretations. Painters reimagined myths with dramatic economy, using repeated gestures and symbolic attributes to evoke character and meaning. The constraints of the technique demanded clarity, and the best painters exploited this to create works of astonishing narrative force.

By the early 5th century, however, a new method had emerged—one that allowed greater freedom and subtlety.

Red-Figure Innovation and Painterly Intimacy

Around 530 BC, Athenian potters introduced the red-figure technique, a reversal of the black-figure method. Here, the background was painted black, and figures were left in the natural red of the clay. Details were then added with fine brushes, enabling lines of varying thickness, shading, and greater anatomical realism. This innovation sparked a renaissance in ceramic painting, allowing for a dramatic expansion in subject matter, composition, and emotion.

Euphronios, one of the earliest and most gifted red-figure painters, pushed the technique to its expressive limits. His calyx krater showing the death of Sarpedon—crafted in collaboration with the potter Euxitheos—is a technical and emotional tour de force. Hermes floats above the battlefield as Sleep and Death carry the slain Trojan prince’s body, blood dripping from his wounds. Muscles ripple, garments swirl, and expressions darken with grief. The composition has depth, curvature, and movement, far beyond the rigid profiles of earlier vases.

Red-figure painters could now depict the body with nuance: torsos twisted in foreshortening, backs arched in exertion, drapery clinging and cascading with tactile realism. The new technique enabled more varied narratives:

- Symposium scenes, with reclining men, flute girls, and erotic interludes.

- Domestic life, showing women at the loom, men at the gymnasium.

- Pedagogical themes, such as young boys learning music or training with a mentor.

One of the most intriguing genres was the white-ground lekythos, a funerary vessel painted on a light slip with added colors. These were often placed in graves and featured delicate scenes of farewell: a woman dressing the grave of a loved one, a youth gazing at his own stele, Hermes leading the soul of the dead. Unlike the heroic tone of earlier ceramics, white-ground lekythoi offered quiet elegies, rendered in gentle line and pastel hues. Their fragility mirrored their purpose—they were not made for longevity but for lament.

By the mid-5th century, painters like Douris, Makron, and the Berlin Painter refined red-figure style into a visual poetry. Figures became more slender, postures more lyrical. The Berlin Painter, in particular, isolated his figures against glossy black fields, highlighting their elegance and emotion. One amphora shows a satyr playing the aulos (double flute), his body curved in a sinuous arc, caught mid-movement as music fills the empty space around him.

These works were not mass-market wares—they were luxury items, purchased by the elite, often exported across the Mediterranean. Greek vases have been found in Etruscan tombs, Iberian sanctuaries, and even as far as Afghanistan. Each one carried not only myth and style but the signature of Athenian craftsmanship.

The Workshop Economy and Athenian Exports

Ceramic production in Classical Athens was not a solitary art but a highly organized workshop industry. Painters and potters often signed their work, indicating a system of branding and pride. Names such as Amasis, Andokides, and Euthymides appear on dozens of surviving vessels, suggesting a thriving marketplace of competitive artists.

The Kerameikos district of Athens, near the Dipylon Gate, was a hub of pottery workshops, kilns, and clay pits. Workers there refined Attic clay, known for its iron-rich, orange-red hue, into a fine-grained medium ideal for painting and firing. The three-stage firing process—oxidizing, reducing, and re-oxidizing—was complex, and mistakes could ruin weeks of labor. Mastery of the kiln was as important as mastery of the brush.

Athenian pottery became one of the city’s most significant exports. It circulated through maritime trade networks to Etruria, Southern Italy, the Levant, and Egypt. In places like Cerveteri and Vulci, Etruscan tombs preserved thousands of Greek vases, many more than survive in Greece itself. These were not mere commodities—they were bearers of ideology. They spread Greek gods, customs, and aesthetics across the Mediterranean world.

The painted vase thus functioned on multiple levels:

- As a ritual object, used in libations, funerals, and sacrifices.

- As a social tool, central to the symposium and elite performance.

- As a narrative canvas, preserving myths and moral lessons in durable form.

By the late Classical period, however, the prestige of painted pottery began to wane. New media—especially large-scale sculpture and architectural relief—became dominant. Pottery shifted toward mass production, and its artistic quality declined. Yet the legacy of these painters and potters endured. Their images, copied by the Romans and studied by modern scholars, became a foundation for Western art’s understanding of gesture, proportion, and mythic structure.

In its Classical heyday, Athenian ceramic art was not an auxiliary craft—it was a primary medium of cultural imagination. It allowed artists to experiment with form, tell layered stories, and give visual shape to the full spectrum of Greek life—from divine exploits to mortal sorrow, from symposiastic flirtation to heroic death. The pot was not only a vessel of wine or oil; it was a vessel of memory.

Hellenistic Dynamism: Emotion, Movement, and Empire

With the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC, the Classical world fractured into kingdoms, colonies, and rival dynasties. The Greek language and artistic tradition, however, did not fragment—it spread, from Egypt to Bactria, from Pergamon to the coasts of Sicily. This dispersion of Hellenic culture under the so-called Diadochi, Alexander’s successors, produced an art that was more global, more dramatic, and more psychologically nuanced than anything before. In the Hellenistic period (323–31 BC), Greek art shifted from perfection to experience, from heroic stillness to expressive motion, from communal ideal to individual emotion.

From Pathos to Theatricality

Hellenistic sculpture is first and foremost emotional. It does not aim at the serene equilibrium of the Classical, but at the stirring of inner sensation. The body remains the central subject, but now it sweats, grimaces, twists in agony or ecstasy. The viewer is no longer meant to admire from a distance, but to feel with the subject—to grieve, to gasp, to desire.

The defining masterwork of this new ethos is the Laocoön Group, attributed to the Rhodian sculptors Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus. This marble ensemble, rediscovered in Rome in 1506, shows the Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons being strangled by sea serpents—punishment, in myth, for warning against the Trojan Horse. The composition coils with violence: Laocoön’s torso arches in pain, his face contorted in agony; the snakes writhe across limbs and chests; the sons, helpless, struggle beside him.

Every muscle is carved in high tension, every vein visible, every expression pushed to the edge of realism. The technical mastery is indisputable, but what dominates is the pathos—the visual language of suffering. This was sculpture designed not for ritual distance, but for visceral proximity. It anticipated not only later Roman baroque but even Renaissance conceptions of the sublime.

Another powerful example is the Dying Gaul, a Roman copy of a Greek bronze likely commissioned for the Attalid kings of Pergamon. The figure is a barbarian—marked by his mustache, wild hair, and torc—but he is rendered with intense dignity. Leaning on one arm, bleeding from a wound, he bows his head in quiet despair. The muscles remain idealized, but the pathos is unignorable. He is enemy, yet noble; defeated, yet beautiful. In this work, the Greek artist does not merely depict victory, but recognizes the cost of violence, the shared humanity of the vanquished.

These statues were not merely decorative—they were political. The Attalids, Seleucids, and Ptolemies used sculpture to stage power, to moralize conquest, to dramatize legitimacy. Art became imperial theater, rich with symbolism and sentiment.

Pergamon, Alexandria, and the Spread of Style

As power shifted from the Aegean to the Eastern Mediterranean, new artistic centers emerged. Pergamon, in Asia Minor, became a showcase of Hellenistic ambition under the Attalid dynasty. The Great Altar of Zeus, built in the early 2nd century BC, is perhaps the most overwhelming sculptural project of the period. Its frieze, over 100 meters in length, depicts the Gigantomachy—the gods’ battle against the giants—with an intensity that dwarfs earlier renditions.

Figures burst from the stone in deep relief, overlapping, interlocking, climbing the architectural surface in near three-dimensionality. Athena seizes a giant by the hair; Zeus hurls thunderbolts; snakes, wings, and limbs fill every inch. This is sculpture approaching cinema: motion rendered in narrative sequence, depth, and visual crescendo. Unlike the calm processions of the Parthenon frieze, this altar overwhelms. It was designed not to soothe but to awe—to position Pergamon as the heir not only to Athens, but to cosmic order itself.

Farther south, Alexandria, capital of the Ptolemaic kingdom in Egypt, became a cosmopolitan melting pot where Greek and Egyptian motifs merged. Alexandrian art often favored intimacy over monumentality: small-scale bronzes, busts, and terracottas depicting scholars, old women, fishermen, or satyrs at rest. The idealized youth gave way to portraits of age, poverty, and character. One Hellenistic terracotta from Tanagra shows an elderly woman hunched, wrinkled, clutching a basket—more Dickens than Homer. These were not allegories—they were people, flawed and specific.

Sculpture of this period often broke traditional boundaries:

- Genre scenes: figures from daily life—children playing, drunkards sleeping.

- Eroticism: Aphrodites bathing, Erotes teasing, sensuality unshackled from decorum.

- Portraiture: not merely flattering, but psychologically insightful, even brutal.

Busts of philosophers, kings, and poets reveal introspection, weariness, cunning—traits absent from earlier idealism. The so-called Pseudo-Seneca, with its furrowed brow and tight lips, stares from the marble not with calm, but with skepticism.

This was the age not of Apollo, but of experience.

Aphrodite, Gauls, and the Sculptural Drama

One of the most emblematic shifts in Hellenistic art is the nude female figure. While Classical artists cautiously explored female anatomy, often draped or implied, Hellenistic sculptors embraced it. The Aphrodite of Knidos by Praxiteles (a Classical precursor) had opened the door. Now, the goddess was depicted bathing, surprised, or seducing—not only divine, but erotic.

The Aphrodite of Melos (Venus de Milo), from around 130 BC, exemplifies this trend. Her torso twists in a graceful spiral, the drapery slipping from her hips. Though her arms are lost, the sculpture suggests movement—a turn of the body, a gesture paused. She is less remote than Praxiteles’ Aphrodite, more assertive in sensuality, and placed in sanctuaries as well as palaces. The line between divine and desirable was intentionally blurred.

Just as women became more prominent in sculpture, so too did foreigners and enemies—most poignantly in works like the Ludovisi Gaul, showing a warrior plunging a sword into his own chest while holding the limp body of his wife. The action is instantaneous, irreversible, and fully cinematic. These were not passive depictions of the vanquished, but full dramatizations of honor, choice, and resistance.

Hellenistic sculptors mastered the display of extremes:

- Extreme youth: chubby infants, winged Erotes, playful or mischievous.

- Extreme old age: toothless satyrs, hunched beggars, bald philosophers.

- Extreme emotion: weeping, laughing, yelling—faces sculpted not for symmetry, but impact.

Architecture, too, adapted to this new theatricality. Stoas (colonnaded halls), gymnasia, and theaters became more elaborate. City planning emphasized axial views, grand staircases, and terraced spaces, often culminating in altars or shrines. Cities like Delos and Antioch adopted hybrid forms, blending Greek layout with local traditions. This was not art for a single polis—it was art for a pluralistic world.

By 31 BC, with the Battle of Actium and the rise of Augustus, the Hellenistic world came under Roman rule. But the art did not die—it transformed again, absorbed into Roman taste, patronage, and replication. Marble copies of Hellenistic bronzes filled villas; Roman emperors adopted the heroic nude; the expressive language of Pergamon and Alexandria filtered into imperial portraiture and basilican reliefs.

The Hellenistic period did not replace the Classical—it answered it. Where the Classical sought to perfect the visible world, the Hellenistic embraced the felt world: messy, mortal, crowded, and passionate. In doing so, it expanded the possibilities of what art could depict, how it could move us, and where it could go.

Roman Greece: Appropriation, Copies, and Continuities

By the 2nd century BC, Greece was no longer the autonomous constellation of poleis that had shaped the ancient world’s cultural imagination. It had become a client of a rising imperial power: Rome. The Roman conquest of Corinth in 146 BC and the subsequent establishment of the province of Achaea marked the beginning of formal Roman rule in mainland Greece. Yet unlike earlier conquerors, the Romans did not aim to extinguish Greek art—they absorbed, replicated, and recontextualized it, often with reverence and fascination. Roman Greece became a paradoxical space: politically subordinate but culturally triumphant, a land where Greek art was simultaneously preserved and reinterpreted through Roman eyes.

Greek Originals and Roman Reproductions

The most striking feature of Roman engagement with Greek art was its systematic appropriation and reproduction of Classical and Hellenistic masterpieces. Roman generals, governors, and emperors treated Greek sculpture as cultural capital—trophies of intellect as much as of conquest. When Lucius Mummius sacked Corinth in 146 BC, he reportedly filled Rome with Greek statuary, temples, and furniture. Other collectors followed suit. Greek art flooded villas, forums, and public baths throughout the Roman world.

This fervor for Greek originals gave rise to an entire industry of copies. Roman sculptors, many of them Greek or trained in Greek workshops, created marble replicas of bronze originals long since lost. Today, many of the most iconic works of Greek antiquity—the Doryphoros of Polykleitos, the Discobolos of Myron, the Aphrodite of Knidos—are known primarily through Roman versions.

These were not forgeries but adaptations, often with subtle modifications. Roman copies sometimes added supports or drapery, adjusted poses, or altered scale to suit domestic interiors or urban spaces. A bronze nude that once stood in a sanctuary might be reproduced in marble, slightly clothed, for the peristyle of a villa.

The copy was not considered inferior. In Roman culture, the Greek past represented a golden age of aesthetics and intellect, and to replicate it was an act of homage and cultivation. Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History, offered lengthy discussions of Greek artists—Phidias, Lysippos, Apelles—treating them as authoritative exemplars. Roman education emphasized Greek literature and philosophy; their taste in art followed the same trajectory.

Yet this imitation also marked a shift in function. Where the original Greek statues had often served religious, funerary, or civic roles, the Roman context was more often decorative or philosophical. Art was curated, not worshipped. The kouros became a garden statue; the goddess, an ornament above a dining couch.

This change of setting did not eliminate meaning—it altered it. Greek art was now part of an imperial narrative. To possess Greek statuary was to signify education, taste, and cultural command. A Roman senator or general could decorate his estate with representations of Apollo or Heracles and thereby associate himself with virtue, power, and cosmopolitan sophistication.

Villas, Mosaics, and Domestic Display

One of the most fertile settings for Greek-inspired art in Roman Greece was the elite villa, especially in the Eastern Mediterranean. In cities like Corinth, Athens, and Delos, Romanized elites—both Greeks and Roman officials—commissioned private residences filled with painted panels, marble busts, and decorative mosaics.

Mosaics in particular became a popular medium for adapting Greek visual themes. These were not large-scale narrative frescoes like those of Pompeii, but intricate floor and wall compositions made of tiny tesserae, often reproducing famous paintings or evoking mythological scenes. A notable example is the Alexander Mosaic from the House of the Faun in Pompeii, itself believed to be based on a lost painting by Philoxenos of Eretria or Apelles. It shows Alexander confronting Darius in battle, rendered with astonishing detail and emotional force. Though found in Italy, it illustrates how Greek narrative models continued to shape Roman visual rhetoric.

In Greece itself, mosaics in cities like Pella and Dion depicted Dionysian revels, marine deities, and hunting scenes—blending Classical balance with Hellenistic motion. Wealthy patrons commissioned these works to signal not only luxury but cultural allegiance. To evoke Greek mythology in a dining room was to claim a position within a shared world of mythic reference and elite values.

Sculpture also adorned villa gardens, atria, and peristyles. Statues of Aphrodite, Hermes, and Apollo were arranged for dramatic visual effect. Some owners even curated fragmentary works, displaying torsos and heads as if staging a private museum. The ruins of Greek sanctuaries became quarries for elite ornament. Corinth, ravaged by Rome and later rebuilt, supplied columns, pediments, and inscriptions for imperial reuse.

This domestic setting shifted the tone of Greek art. The god became an aesthetic companion; the hero, a reminder of personal virtue. The viewer was not a worshipper or citizen, but a host, guest, or philosopher, immersed in visual culture as a sign of cultivated life.

Athens under the Caesars

Athens, long past its political prime, gained renewed prominence under Roman rule as a symbolic capital of culture. Roman emperors—especially Hadrian—invested heavily in its restoration, honoring its legacy as the wellspring of philosophy, rhetoric, and the arts.

Hadrian, who styled himself as a new Hellenic ruler, ordered the construction of temples, libraries, and public baths in Athens, including the Library of Hadrian and the massive Olympieion, a temple begun in the 6th century BC and finally completed under his patronage. The emperor even received heroic honors in the Greek style, with statues placed in sanctuaries and inscriptions celebrating his wisdom and piety.

Athens’ artistic workshops remained active, producing statues, portraits, and architectural reliefs in a retrospective style. Rather than innovate, they sought to emulate and revive the Classical. This was not decadence but a form of cultural conservation. Greek artists, often working under Roman commissions, became interpreters of their own heritage.

One of the most significant outcomes of this period was the rise of sophistic portraiture—realistic, expressive busts of philosophers, rhetoricians, and civic leaders. These were displayed in lecture halls, gymnasia, and libraries, visually reinforcing Athens’ identity as a city of wisdom. Figures such as Socrates, Demosthenes, and Zeno were idealized in marble, even as contemporary thinkers commissioned their own images in imitation of the past.

In this environment, the Greek artist became both craftsman and historian, preserving styles from the 5th and 4th centuries BC while subtly adapting them for Roman taste. The art of Athens under the Caesars was not innovative, but it was reverent, skillful, and quietly sophisticated.

Roman Greece, then, was a paradox: it preserved Greek visual traditions while draining them of their original civic and religious vitality. But it also gave those traditions global reach. A kouros now stood in Gaul; an Aphrodite reclined in North Africa. The artistic grammar invented on the Athenian Acropolis or the island of Rhodes became the common language of an empire.

The Roman appropriation of Greek art was not mere plunder—it was transformation. It changed not only where and how Greek art was seen, but also what it meant. No longer confined to sanctuaries or symposiums, it now adorned the imperial imagination, embedding Greek form in the visual ideology of Roman power.

Christian Transformation: From Pagan Temples to Early Churches

The long twilight of pagan antiquity did not cast Greek art into shadow—it reshaped it. Between the 4th and 6th centuries AD, as Christianity took root and ultimately dominated the Eastern Roman Empire, Greek visual traditions were gradually redirected toward new religious ends. Pagan gods disappeared from pediments, civic nudes were draped or defaced, and temples were gutted, rededicated, or abandoned. But this was not an erasure. The Christian transformation of Greek art was a slow, complex reworking—less a rupture than a palimpsest of forms, where the sacred was not discarded but redefined.

Iconoclasm and the Anxiety of Image

The relationship between early Christianity and visual representation was profoundly ambivalent. In its first centuries, Christian leaders debated whether images were spiritually dangerous or pedagogically useful. Drawing on Jewish aniconic traditions and suspicious of pagan idolatry, many Christians initially avoided figural art in religious contexts. Catacomb paintings from Rome and early Christian mosaics in Thessaloniki show cautious symbolism: the Good Shepherd, the fish, the chi-rho—coded signs rather than overt representations of Christ.

Yet as Christianity moved from underground sect to imperial religion—especially after Constantine’s conversion in the early 4th century—the image became unavoidable. Constantine’s successors endowed the church with land, privilege, and monumental architecture. Christianity now needed public art—images not only to instruct but to glorify, to dominate space as pagan temples once had.

This tension reached a breaking point in the Iconoclastic Controversy of the 8th and 9th centuries, which shook the Byzantine Empire to its foundations. The dispute was theological, political, and aesthetic. Iconoclasts condemned images of Christ and the saints as heretical and idolatrous, citing the Second Commandment. Iconodules defended them as incarnational theology—just as God took human form in Christ, so could holy figures be depicted in material form.

In Greece, this debate left lasting marks. Frescoes and mosaics were whitewashed or scraped away. Sculptures were destroyed, defaced, or buried. The ancient skill of figural depiction, honed for centuries in service to gods and mortals, now stood trial under new religious laws. But even as images were contested, they remained inescapable. By the end of the 9th century, under the Empress Theodora, iconoclasm was reversed. Image-making resumed—this time with renewed theological caution and rigorous aesthetic codes.

Basilicas and the Synthesis of Space

As Christian art developed in the Greek world, it did so not in temples but in basilicas—a Roman architectural form adapted for liturgical function. The basilica’s long nave, side aisles, apse, and clerestory provided a linear space well suited to procession, preaching, and display. Where Greek temples had housed gods in darkness, visible only from outside, Christian churches brought congregants inside, surrounding them with images, light, and sacred sound.

Some of the earliest and most important basilicas in Greek-speaking regions include:

- The Basilica of Saint Demetrios in Thessaloniki, originally built in the 5th century, whose mosaic program links civic identity with martyr devotion.

- The Church of the Acheiropoietos, also in Thessaloniki, named for an icon “not made by human hands,” which embodied theological tension around image-making.

- The Panagia Ekatontapyliani in Paros, a complex with roots in Constantine’s time, later adorned with mosaics and sculpted capitals blending pagan and Christian motifs.

Within these spaces, visual art took on new liturgical and theological roles. The apse became the site of the Christ Pantokrator—ruler of all—hovering above the altar in celestial judgment. Saints flanked the nave, organized by hierarchy and typology. The narrative cycle moved from mythic incident to salvific history: Annunciation, Nativity, Crucifixion, Resurrection.

Mosaics, with their golden light and glittering tesserae, became the preferred medium. Unlike the sculptural reliefs of antiquity, mosaics evoked heavenly transcendence, their surfaces denying shadow and depth. In this sense, Christian art rejected the humanism of the Classical nude in favor of a flattened metaphysics. The body was no longer idealized for its proportion but transfigured as symbol—a carrier of sanctity, not sensuality.

Architecture followed suit. Columns were reused from pagan temples, but capitals were recut with crosses, vine scrolls, and monograms of Christ. Porticos and atria served as baptismal spaces or liturgical forecourts. The church became a visual theology—space, image, and sound orchestrated to form a sensory theology of presence.

Mosaics, Martyrs, and the Visual Vocabulary of Faith

Christian art in Roman and post-Roman Greece developed its own iconographic grammar, drawn in part from the Classical past, but now deployed to narrate martyrdom, miracle, and salvation. The mosaic, more than any other medium, became the primary site of doctrinal display.

In Thessaloniki—then a vital provincial capital—5th and 6th-century churches reveal the vibrancy and regional strength of Greek Christian visual culture. The Rotunda of Saint George, originally built as a Roman mausoleum or temple, was converted into a church under Theodosius and adorned with mosaics of apostles and saints in celestial zones. The dome features a ring of martyrs, clad in white, moving in solemn rhythm toward a central throne—symbol of divine presence. The figures are static, frontal, ethereal—far removed from the contorted dynamism of Hellenistic art.

The Latomos Monastery, another Thessalonikan treasure, preserves an apse mosaic from the 5th century that depicts Christ in radiant mandorla, surrounded by symbols of the Evangelists. Here the composition fuses the Roman imperial image of the enthroned emperor with the transfigured Lord of Heaven. The vocabulary is Greek—yet the message is wholly Christian.

This transformation also reached into funerary art. Sarcophagi, now Christianized, showed not myths of Herakles or Dionysus, but scenes of Jonah and the whale, the Raising of Lazarus, or the Good Shepherd. Reliefs borrowed Classical motifs—Corinthian columns, garlands, acanthus—but they reassembled them around the narrative of resurrection and judgment.

Art, in this era, served as catechism. It instructed the illiterate, reinforced orthodoxy, and provided visual continuity in an era of doctrinal struggle. It also offered solace. In an age of martyrdom, plague, and political uncertainty, the steady gaze of a mosaic saint or the golden dome of a basilica provided not only beauty but metaphysical reassurance.

Even as the Roman world crumbled in the West, Greek Christian art retained its elegance, discipline, and visual authority. In Athens, the Parthenon itself would be converted into a church. The gods had departed, but the space remained sacred—its columns now repurposed for Christ.

The Christian transformation of Greek art was not a story of loss, but of translation. Myth gave way to martyr, hero to saint, balance to transcendence. The visual language of Classical Greece did not disappear—it was retooled to express a new cosmology, a new salvation history, and a new vision of the eternal.

The Byzantine Turn: Gold, Frontality, and the Language of Icons

With the formal establishment of Constantinople as the imperial capital in AD 330 and the gradual evolution of the Eastern Roman Empire into what we now call Byzantium, Greek art entered a period of radical stylistic and spiritual transformation. The shift was not a matter of rupture but of deep structural change—an internal reorientation of form toward theological presence, liturgical function, and cosmic symbolism. What had once been rooted in the body, motion, and narrative became centered on light, surface, and divine visibility. The Byzantine turn was not a rejection of the Classical—it was a transfiguration of its language into a new mode of sacred abstraction.

Hagia Sophia and the Triumph of Light

At the heart of the Byzantine aesthetic revolution stands the Hagia Sophia, completed in AD 537 under the direction of Emperor Justinian I and the architects Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus. Though now a mosque, and for centuries a museum, its original purpose was to be the supreme Christian church of the empire—a temple not only to Christ but to divine order manifested in structure.

From the outside, Hagia Sophia’s massed domes and buttresses present an austere bulk, but inside, the space opens into an unearthly radiance. The central dome—105 feet across, seemingly suspended from heaven—floats on pendentives supported by massive piers. Windows encircle its base, creating an illusion of weightlessness. Procopius, the court historian, wrote that the dome “seems not to rest on solid masonry, but to cover the space with its golden dome suspended from heaven by a chain of gold.”

This architectural language was not merely technical—it was theological. Hagia Sophia translated heaven into geometry, fusing Roman engineering with mystical Christian purpose. Light became the medium of revelation. Mosaics, some of them later covered or destroyed during iconoclastic periods, shimmered in gold and glass tesserae, their surfaces not descriptive but emissive, radiating sanctity rather than depicting events.

This approach recast the very aims of visual art. In the Classical temple, sculpture inhabited space with muscular presence; in the Byzantine church, art withdrew from mass into surface, from narrative into eternity. Walls were no longer containers—they became icons in stone.

Hagia Sophia inspired countless imitations, from the Church of the Holy Apostles in Thessaloniki to the domed churches of Mystras and Mount Athos. Its aesthetic vocabulary—central dome, light-filled apse, marble revetment, mosaic icon—defined the canon of Byzantine sacred space for nearly a millennium.

Icon Painters and the Theology of Surface

Central to Byzantine art is the icon, a sacred image painted on wood, often of Christ, the Virgin, or a saint. Far from being a decorative object, the icon was a liturgical presence—a window onto the divine, a means of intercession, a locus of encounter. The theology behind the icon was precise and contested. After the iconoclastic controversies of the 8th and 9th centuries, the Orthodox Church affirmed that the veneration of icons was not idolatry but a recognition of incarnation: that Christ, having taken on flesh, could be pictured in visible form.

Byzantine icons followed strict conventions. Figures are frontal, symmetrical, solemn. They gaze not at the scene but into the viewer, establishing a metaphysical exchange. Gold backgrounds eliminate spatial depth, placing the figure in a realm outside time. Halos, inscriptions, and stylized garments emphasize symbolic clarity over physical realism.

A typical Christ Pantokrator icon—such as the one in the dome of the Church of Daphni near Athens—shows Christ with one hand raised in blessing, the other holding the Gospel. His features are stable across centuries: long nose, parted beard, symmetrical face, piercing eyes. The image is not meant to vary, but to persist, ensuring continuity of faith across distance and generations.

The painters of these icons—often monks—did not view themselves as artists in the modern sense. They were craftsmen of the sacred, transmitting tradition rather than expressing individuality. Icons were painted using egg tempera on wood panels, often with gilded backgrounds and intricate borders. The process was meditative, guided by prayer and the strict repetition of inherited forms.

Yet within this rigor, astonishing beauty flourished. In Crete, Macedonia, and Mount Athos, schools of icon painting developed rich local variations. The 14th-century painter Manuel Panselinos, associated with the Protaton Church in Karyes, is often considered a master of spiritual expression. His saints possess subtle individuality: weathered faces, grave serenity, warmth held beneath solemnity. These were not portraits of the living, but images of sanctity distilled into form.

Continuity and Control in Religious Art

Byzantine art, particularly in Greece, maintained formal consistency across centuries that elsewhere would have seen revolutions. From the 10th through the 15th centuries, churches in Greece continued to employ the domed cross-in-square plan, to decorate interiors with narrative fresco cycles, and to adhere to iconographic formulas established in earlier centuries.

The Monastery of Hosios Loukas in Boeotia, founded in the 10th century, offers a complete ensemble of Byzantine visual theology. Its katholikon (main church) features mosaics of the Pantokrator in the dome, the Virgin in the apse, and an elaborate program of saints and feasts along the walls. The decoration unfolds not as a continuous story but as a theological cosmos—a hierarchy of presence, from the divine at the dome to the saints among the people.

By the late Byzantine period, especially in post-Iconoclast Greece, frescoes became more emotionally expressive, narrative cycles more detailed. The Church of Saint Nicholas Anapausas in Meteora, painted by Theophanes the Cretan in the 16th century, shows a blend of spiritual gravity and human drama: martyrdoms rendered with vivid gesture, faces marked by pain, but always within a framework of liturgical order.

This control was not only aesthetic—it was institutional. The Orthodox Church regulated iconography with iconographic manuals, such as the Hermeneia of Dionysius of Fourna, which prescribed how each saint, feast, or miracle should be depicted. Innovation was permitted, but always within theological boundaries.

Yet this conservatism did not mean stagnation. Byzantine artists experimented with:

- Architectural illusion, using perspective in apses to suggest heavenly realms.

- Color harmonies, especially rich blues, vermilions, and greens set against gold.

- Narrative condensation, reducing complex stories into emblematic, mnemonic scenes.

In times of crisis—such as during the Latin occupation or Ottoman incursions—icons and frescoes became acts of preservation, visual affirmations of identity and continuity. A small chapel in a mountain village might contain images painted by itinerant monks, recalling the great mosaics of Constantinople in microcosm.

Byzantine art in Greece was never isolated—it was part of a broader Orthodox world stretching from Russia to the Balkans, but its Greek roots remained vital. Even after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Greek monasteries, island churches, and village chapels continued to produce and venerate icons. The language of gold and frontality persisted, a counterweight to Western naturalism, asserting that true vision lay not in the visible world but in the radiance beyond it.

The Byzantine turn was thus not a decline but a recalibration—a shift from body to spirit, from narrative to presence, from motion to mystery. It preserved Greek visual intelligence in a new theological key, transforming ancient craft into a medium of transcendence.

Greek Art in the Ottoman Period: Survival, Synthesis, and Craft

The fall of Constantinople in 1453 marked the end of the Byzantine Empire but not the end of Greek artistic production. Under Ottoman rule, Greek art did not vanish—it adapted, quietly persisting through the endurance of local traditions, monastic patronage, and craft-based resilience. In the centuries between the mid-15th and early 19th, while monumental architecture receded and imperial patronage faded, Greek artists turned inward: toward liturgical function, folk aesthetics, and hybrid forms shaped by coexistence with Islamic visual culture. This was an era of survival through transformation, when art became both a spiritual practice and a subtle form of cultural memory.

Churches Hidden in Plain Sight

One of the most enduring features of Greek artistic life under Ottoman rule was the preservation of ecclesiastical painting, especially in the Greek mainland, the Peloponnese, and the islands. Though the construction of new, prominent churches was restricted in many cities, Orthodox communities continued to build and decorate chapels—often small, concealed, and built below the skyline of mosques. These “hidden churches” became key sites for sustaining visual traditions inherited from the Byzantine world.

In places like Meteora, Mount Athos, Zagori, and the Peloponnesian Mani, monastic and rural communities maintained a remarkably conservative visual language. Fresco painters worked in the Byzantine idiom, using egg tempera and traditional iconography, sometimes layering new work over older schemes in churches that had endured from the 10th century onward.

One striking example is the Church of the Transfiguration in Veltsista, a village in Epirus, where a 16th-century painter reproduced scenes from the life of Christ with a clear debt to late-Byzantine models. The figures are frontal, the faces sober, but now the drapery becomes heavier, gestures more compressed, and the color palette shifts slightly toward earth tones. The iconostasis (screen separating nave and altar) becomes increasingly elaborate, often filled with carved wood, gilded surfaces, and tiers of icons that served as the visual centerpiece of Orthodox worship.