The Adriatic shimmered with civic pride in the spring of 1895. On April 30th, Venice—once a fading museum of maritime memory—opened its Giardini to a crowd of monarchs, diplomats, artists, and critics for the inauguration of the I Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte della Città di Venezia, the first Venice Biennale. At the helm stood Mayor Riccardo Selvatico, a poet and politician who saw in this new exhibition not just a celebration of painting, but a deliberate reassertion of Venice’s cultural authority. What began as a municipal initiative quickly rippled outward, drawing artists from fifteen countries and crystallizing an entirely new format: the permanent international art exhibition.

A City Rewrites Its Role

Venice in the 1890s was not the romantic republic of canal dreams; it was an Italian province still recovering from the unification process, uncertain of its future, but possessed of a past too heavy to ignore. Selvatico’s vision was straightforward and pragmatic: to reinvent Venice as a global cultural capital by anchoring it to a recurring art event of international stature. Inspired in part by the success of world’s fairs, the Biennale would be permanent, biennial, and explicitly international—a break from the inward-facing Salons and Expositions of Paris, Munich, and Rome.

To accomplish this, the city renovated the Giardini di Castello, a royal park gifted by Napoleon, and transformed it into a dedicated exhibition site. A neoclassical pavilion was erected to house the Italian section, with wide, well-lit galleries tailored to large-scale oils. The planning committee, led by Antonio Fradeletto, aggressively courted international submissions, writing directly to embassies, academies, and collectors across Europe. The result was impressive: over 200,000 visitors attended the inaugural edition, and it brought works from Germany, France, Belgium, Russia, and beyond into the Venetian orbit.

The First Hanging: Politics, Popularity, and Provocation

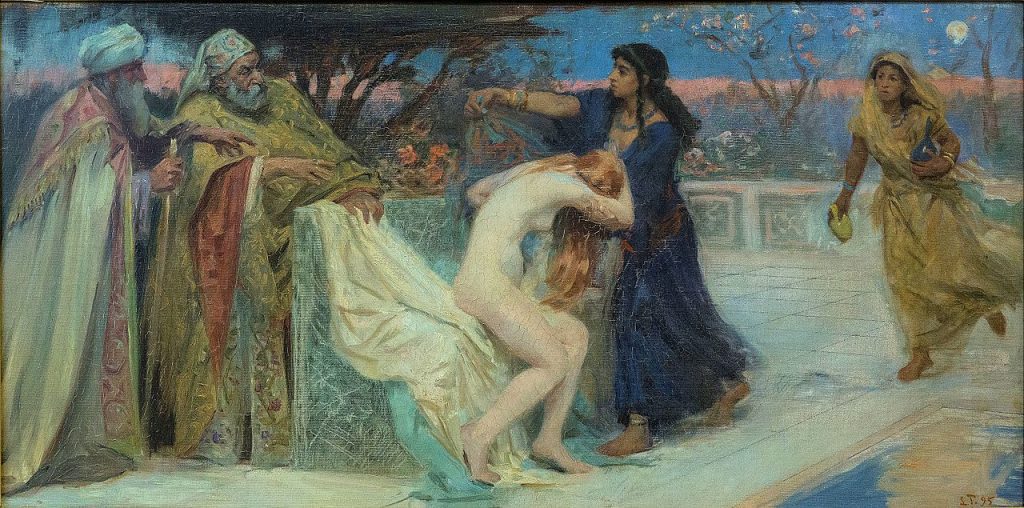

Among the many submissions, few stirred more immediate reaction than Supremo Convegno (“The Supreme Meeting”) by Giacomo Grosso, an allegorical painting that staged a nude female gathering around an open coffin. Grosso, a professor at the Accademia Albertina in Turin, was known for academic nudes with theatrical flair. His 1895 entry managed to offend conservatives and captivate the public simultaneously. The Vatican’s representative reportedly protested its inclusion; nonetheless, it remained on view, cordoned by a velvet rope—and won the exhibition’s popular prize by overwhelming margin.

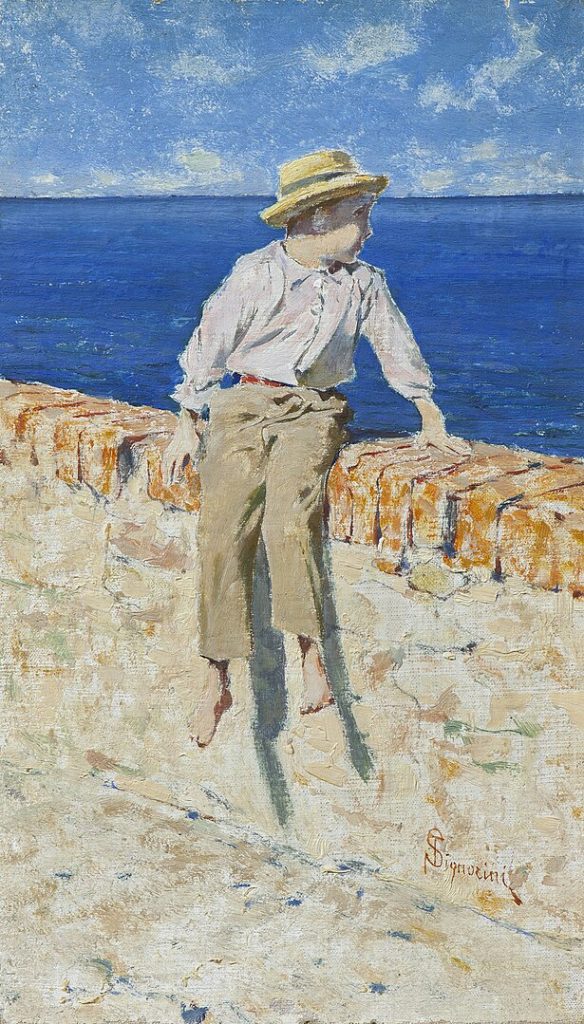

This episode revealed the Biennale’s early paradox: it aspired to academic dignity but was unavoidably democratic. The organizers had promised high art, but also novelty, accessibility, and international breadth. That meant reputations were tested in full public view. Italian painter Francesco Paolo Michetti exhibited La figlia di Jorio, a large, folkloric canvas brimming with Abruzzese detail. Giovanni Segantini, not yet a household name, showed Ritorno al paese natio, one of his psychologically rich Alpine compositions. Both were praised for their national flavor, but Segantini’s work, darker and more symbolist, puzzled some audiences.

Meanwhile, Germany sent Max Liebermann, who offered his Portrait of Gerhart Hauptmann, a brooding, realist depiction of the dramatist framed by tobacco smoke and cerebral gloom. Liebermann’s technique—brushy, restrained, quietly psychological—was respected by fellow artists but less embraced by the general public. In retrospect, the 1895 Biennale was conservative in its overall selections, leaning heavily on academic and nationalist favorites. Yet its infrastructure made it something radically new.

France Declines, England Stalls

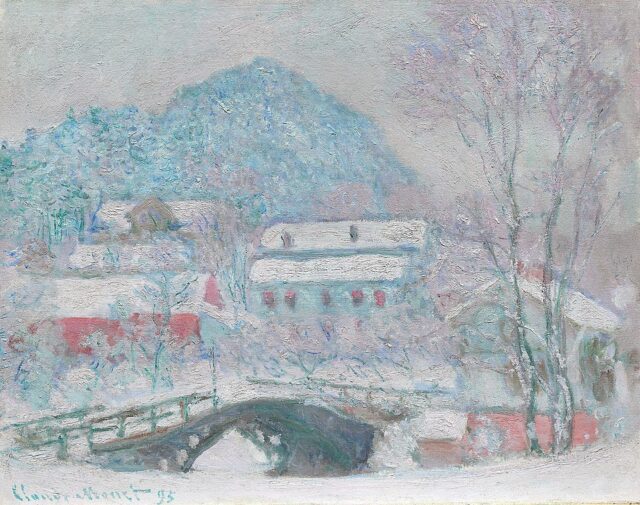

Notably absent from the inaugural Biennale were the heavyweights of French modernism. Monet, Cézanne, and Gauguin were nowhere to be seen, and the French state did not formally participate. This was no accident. Fradeletto and Selvatico had invited major French artists, but the centralized French Salon system and ministerial conservatism made official participation unlikely. Private French dealers and collectors, on the other hand, would eventually come to dominate future editions. In 1895, their absence left a conspicuous hole.

The British, for their part, hesitated. The Royal Academy offered no official support, and the Pre-Raphaelite and aesthetic circles of London remained aloof. A few individual British artists participated, but without institutional weight or critical focus. It would not be until the Edwardian era that British involvement grew substantial, driven by Whistler’s late-period influence and the rise of commercial galleries.

Legacy in Stone and Schedule

What the 1895 Biennale did achieve, with remarkable efficiency, was the creation of a permanent international structure that bypassed both the national Salon model and the ephemeral World’s Fair. The decision to hold it every two years, in a dedicated site with municipal support but international reach, made it unique—and uniquely adaptable.

The Giardini would soon host national pavilions, each designed to represent its country’s cultural output. But in 1895, the space was still unified, and still optimistic. The exhibition’s architecture, layout, and even catalogue reflected a confident belief in artistic exchange without coercion. That belief would be tested—sometimes broken—in the decades to come. But in its inaugural year, the Biennale seemed to open a door rather than draw a line.

Chapter 2: The Salon and the Secession—Conflicting Models of Artistic Authority

The spring of 1895 brought more than flowers to Paris—it brought a public clash between institutions that claimed, each in its own way, to speak for the future of art. That April, the walls of the Champ de Mars hosted yet another edition of the Paris Salon, the most prestigious and enduring exhibition in Europe. But it no longer stood alone. Just across the Seine, the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts was building its own identity with vigor, drawing younger artists and impatient critics. This schism—between academic orthodoxy and artist-led reform—was not unique to France. In the same year, across the Austro-Hungarian Empire, murmurs of rebellion among painters and architects hinted at what would soon break open into the Viennese Secession. 1895 was a year of positioning: a moment when the façade of institutional consensus remained intact, even as its foundations were beginning to shift.

A House with Two Front Doors

By 1895, the Paris Salon was a century-old monument. Founded under royal auspices in the 18th century, it had long been the official exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. In theory, it was open to all; in practice, it functioned as a gatekeeper for the French art world. Painters who were hors concours—those exempt from jury approval—were granted central placements, medals, and the assurance of commissions. But over the previous two decades, this academic stronghold had been weakened by defections. The most consequential was the 1890 reformation of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (SNBA), which staged its own Salon at the Palais des Beaux-Arts, also at the Champ de Mars. The two Salons coexisted uncomfortably, like estranged siblings sharing a family name but not a household.

The 1895 SNBA Salon was a success by many conventional standards: nearly 400 exhibitors, favorable press, and growing public attendance. Its leadership included figures such as Puvis de Chavannes, whose grand murals were admired even by his detractors. More importantly, the SNBA allowed greater latitude in selection and style. Jean-Louis Forain, best known for his sharply satirical drawings in Le Figaro, showed works that would never have passed the stricter jury of the official Salon. Other artists—including Jules Bastien-Lepage’s followers and the increasingly independent symbolists—found in the SNBA a space to exhibit without altering their vision to fit a state-approved mold.

Bureaucracy and Aesthetic Paralysis

Still, the official Salon persisted. Its defenders argued that it preserved the unity of national taste, protected public morality, and upheld the ideal of “le grand art.” In 1895, the Salon featured the usual round of historical tableaux, allegorical nudes, and military scenes—solid, conservative fare. William-Adolphe Bouguereau remained a dominant presence, his paintings refined and technically unassailable. Yet even sympathetic critics could not help but notice a kind of inertia. A reviewer in La Liberté wrote, “The official Salon moves as a regiment does: in step, in uniform, and toward a destination long since named.”

That sense of stasis was not only aesthetic—it was structural. The Académie, bound by rules and rituals, was slow to adapt to changes in public taste or artistic ambition. Younger painters, even when technically skilled, found themselves shut out if their work deviated too far from accepted themes. The preference for polished surfaces, linear clarity, and moral uplift made little room for ambiguity, irony, or experimental color. And without fresh blood, the Salon risked becoming what its critics already accused it of being: an exhibition of the past, not the present.

Letters from Vienna: The Seeds of Secession

While Paris juggled its twin Salons, Vienna was entering its own period of gestation. The year 1895 saw no formal rupture, but many of the key figures who would found the Vienna Secession in 1897 were already gathering, discussing, and sketching alternatives. Gustav Klimt, still painting in a refined historicist style, was increasingly dissatisfied with the Kunstlerhaus, Vienna’s official exhibition body. Alongside him stood Carl Moll, a painter of severe interiors and crisp cityscapes, and Josef Hoffmann, an architect whose work was beginning to show a preference for geometric rigor over academic flourish.

The Viennese art world in 1895 was a conservative one, dominated by imperial tastes and Habsburg decorum. State commissions went to painters who specialized in allegory, architecture was a servant of nostalgia, and the official exhibition circuit discouraged deviation. But something in the air had changed. Otto Wagner was beginning to publish his thoughts on modern urbanism. Collectors, especially among the Jewish mercantile class, were developing an interest in new forms. Art journals such as Ver Sacrum were in the planning stages, seeking to create a venue for unorthodox ideas. Though still unofficial, the Secession’s outline could be seen in silhouette.

A Turning Point Without a Name

What links the Parisian and Viennese situations in 1895 is a shared discomfort with inherited institutions. Artists were not yet united around a single style or ideology, but they were increasingly unwilling to defer to the slow machinery of bureaucratic juries and ministerial aesthetics. In Paris, this took the form of cohabitation and rivalry; in Vienna, it took the form of whispered conspiracies and the quiet gathering of like minds. The idea of the artist as an independent actor—neither state functionary nor salon ornament—was beginning to take hold.

To be sure, academicism had not collapsed. Bouguereau was still winning medals. Puvis de Chavannes was still executing public murals. But a younger generation no longer took institutional prestige as synonymous with artistic value. They wanted different subjects, different forms, and—above all—a different structure for being seen.

By the end of the century, the old systems would splinter definitively. But in 1895, the cracks had begun to show, and those watching closely knew that the ground was shifting.

Chapter 3: Munch in Crisis—Berlin Exhibition Closure and Scandinavian Reception

By 1895, Edvard Munch had become a name capable of stirring admiration, confusion, and outrage in equal measure. His art, shaped by illness, grief, and a lifelong confrontation with the fragility of the self, was unlike anything else on the European circuit. Though his work would later come to represent the emotional depths of modernism, its early reception was marred by hostility. The most dramatic of these early confrontations unfolded not in his native Norway, but in the heart of the German Empire—Berlin—where his art became the catalyst for a public quarrel that marked a pivotal moment in both his career and the broader evolution of the European avant-garde.

The Berlin Revolt and Munch’s Expulsion

The seeds of this controversy had been planted three years earlier, in 1892, when the Verein Berliner Künstler invited Munch to exhibit at their gallery in the Architektenhaus. The show, featuring nearly 60 of his recent works, was unlike anything their audience had seen: ghostly figures, agitated brushwork, and psychological tension rendered in an unflinching palette. The response was immediate and visceral. Senior members of the association condemned the paintings as unfinished, immoral, and even dangerous. After only a week, the exhibition was shut down by vote—an unprecedented move that set off a chain reaction of editorials, letters, and counter-accusations in the Berlin press.

Although the incident technically occurred in 1892, its repercussions stretched well into 1895. Munch had returned to Berlin, not as a penitent, but as a provocateur. That year, he exhibited again—this time through more independent and sympathetic channels. The earlier controversy had, paradoxically, made him a symbol of resistance to the institutional chokehold of the conservative academy. Young German artists rallied to his defense, and the scandal helped spur the formation of the Berlin Secession a few years later. What had been a rejection became a milestone.

The Turn to Print and the Expansion of Form

It was also in 1895 that Munch pivoted decisively toward printmaking—a medium that would allow him to amplify his reach and explore new dimensions of his themes. This shift was not merely technical. The medium of lithography, drypoint, and woodcut suited Munch’s desire to strip away the inessential, to hone imagery down to its psychic essentials. That year, he produced the first lithographic version of The Scream, translating one of his most haunting images from paint into ink, and creating a work that could circulate more widely and intimately than any oil on canvas.

Munch’s prints—especially his portraits and symbolic subjects—gained immediate attention among progressive collectors and critics. They also allowed him to consolidate what he had begun to call The Frieze of Life, a loose series of works meditating on love, anxiety, jealousy, despair, and death. Unlike traditional cycles or narratives, the Frieze was structured thematically rather than chronologically. 1895 marked a turning point in its evolution, as key images from previous years were revisited, revised, and reissued in graphic form. The ability to repeat and reframe his motifs was not an act of reproduction but a deepening of his conceptual language.

Reception in the North: Ambivalence and Admiration

While Munch’s Berlin episodes captured the attention of Central European critics, his position in the Scandinavian art world remained more complex. In Norway and Denmark, where nationalism and naturalism still dominated critical taste, his style was met with suspicion, even as his growing international stature made him increasingly difficult to dismiss. He continued to exhibit in Kristiania and Copenhagen throughout the mid-1890s, but critical response ranged from puzzled to openly hostile. His refusal to depict the external world in the manner expected of his peers—pastoral, anecdotal, or folkloric—isolated him from local trends.

Still, he had his defenders. A small circle of artists and writers in Oslo saw his work as part of a necessary evolution. They viewed his subjects—often depicting solitary figures in ambiguous settings, caught in moments of emotional rupture—as closer to poetry than to painting. For them, Munch was not a foreign imitator of French or German symbolism, but an originator whose vision emerged from his own inner turmoil and the particular emotional climate of the far north. This view remained a minority position, but it hinted at the shift to come.

From Scapegoat to Forerunner

The events of 1895 placed Munch in a strange and powerful position. He was no longer a provincial outsider, but not yet fully embraced by the major institutions of European art. The hostility of his early critics had, ironically, made him a symbol of modernity’s growing rift with the past. The rejection of his Berlin exhibition had led to the establishment of alternative venues, to the emboldening of young artists, and to a rethinking of what expressive painting could achieve. It also hardened Munch’s own resolve. He was increasingly confident that painting’s task was not to please, but to reveal.

The psychological intensity of his imagery—mocked in 1892—was by 1895 beginning to seem prophetic. Aesthetic norms were changing. The idea that the self might be fractured, haunted, or contradictory was no longer foreign to the intellectual climate. Munch had captured something of this before others dared to. That he had done so by scandal, rather than praise, only made his work feel more essential.

Chapter 4: Redon and the Symbolist Imagination

The light in Odilon Redon’s work never comes from the sky. It glows from within skulls, flowers, eyes, and shadows—radiating inward rather than outward. By 1895, Redon had come to represent something singular in French art: a painter of the invisible, a draftsman of dreams, and a master of ambiguity in an era still tethered to naturalism. His work did not aim to imitate the visible world but to conjure what might lie behind it, or beneath it, or after it. In doing so, Redon became the visual counterpart to Symbolist poetry and philosophy, an artist whose influence extended beyond his modest commercial success into the deeper currents of intellectual and artistic change.

Charcoal Phantoms and a New Kind of Vision

Throughout the 1880s, Redon had created a series of charcoal drawings—he called them noirs—that featured levitating heads, staring eyes, winged hybrids, and shapeless shadows. These images, often uncaptioned or accompanied by cryptic titles like The Eye, Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Toward Infinity, confounded traditional expectations of subject matter and technique. The blackness of the medium was not merely formal; it became existential. Critics likened them to hallucinations or nightmares, but for Redon, they were closer to meditations: attempts to visualize the immaterial.

By 1895, these earlier charcoals were widely known, though not universally admired. They had circulated among writers, collectors, and fellow artists, many of whom considered them deeply original but also unsettling. What changed in the mid-1890s was Redon’s gradual move into color—and with it, a widening of both his expressive palette and his audience.

Pastel and the Turn Toward Color

The early 1890s marked a slow but decisive transformation in Redon’s practice. He began working in pastel and oil with increasing frequency, applying translucent layers of color to compositions that retained the surreal intensity of his charcoal work. Flowers became a recurring motif—often imagined rather than observed—and faces emerged from saturated backgrounds like spirits in a fog. These pastel works, some of them shown in private galleries and independent salons by 1895, startled critics who had grown accustomed to his grays and blacks. Instead of darkness, there was now radiance—but the mystery remained.

These new works did not abandon the Symbolist impulse; they deepened it. Color, for Redon, was not a decorative effect but a means of suggesting the unknowable. His portraits—particularly those of imagined beings, saints, or mythic archetypes—radiated a calm intensity, as if lit by internal consciousness rather than by exterior light. One pastel from the mid-1890s shows a luminous blue figure with downcast eyes and a crown of feathers, framed by floating globes. It resists literal interpretation, but it holds the viewer with a sense of spiritual gravity.

A Movement Without a Manifesto

Redon never declared himself a Symbolist, and yet he was embraced by the poets and critics who defined the movement. Writers like Stéphane Mallarmé and Joris-Karl Huysmans saw in his work a visual equivalent to their own pursuit of suggestion over declaration, of mood over message. Redon’s images were not illustrations of poems, but rather fellow travelers—drawn from the same impulse to reach beyond surface appearances toward inner meaning.

In 1895, the Symbolist movement was at its intellectual height. It had its own journals, such as La Revue Blanche, and its own salons and circles. Yet unlike Impressionism, Symbolism was not grounded in a common technique or even a coherent group of artists. It was an atmosphere, a disposition. In that atmosphere, Redon thrived. His art did not explain itself—it provoked a kind of contemplative doubt.

This open-endedness allowed Redon to escape the dogmatism that plagued other late-century movements. Where some Symbolists fell into heavy allegory or esoteric pretension, Redon’s works remained weightless, even when they were somber. A drawing of a headless torso rising from blackness suggested death, but without horror. A series of floating eyes evoked surveillance, but also cosmic wonder. He was not illustrating a metaphysics so much as suggesting its contours.

Redon’s Place in 1895: Inside and Outside the System

Though not a sensation in the commercial art market, Redon by 1895 had a steady following among avant-garde collectors and fellow artists. He exhibited discreetly, usually through sympathetic dealers or alongside literary circles, and avoided the grand institutional salons. His relationship with the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts was cordial but distant; he did not seek medals or positions. Yet he influenced a wide swath of painters—from Pierre Bonnard and Maurice Denis to younger symbolists and Nabis who admired his refusal to explain.

In some respects, Redon’s position in 1895 mirrored that of Munch in Berlin, or Segantini in Milan: not central to the official narrative, but central to something deeper—an underground current that was shaping the next century’s art. Redon’s work was not about innovation for its own sake, nor did it rebel against tradition with manifestos or provocations. Instead, it quietly proposed a different reason for art to exist.

By the end of the year, his pastels had found their way into several influential private collections, and his prints circulated among bibliophiles and writers. His art had no school, and yet it spoke to a growing audience that found in it a necessary antidote to the external clamor of modern life. Redon had made space for the invisible—and by doing so, altered the visible.

Chapter 5: Bouguereau’s Last Triumphs

By 1895, William-Adolphe Bouguereau stood atop a crumbling pedestal. For nearly half a century, he had been the gold standard of French academic painting: a master of anatomical precision, mythological themes, and smooth, luminous surfaces. He was a Salon favorite, a member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, a teacher at the Académie Julian, and a fixture in the institutional life of French art. But the ground beneath him had begun to shift. Though he remained revered in official circles and admired by collectors, a younger generation was turning away—not necessarily in rebellion, but in search of something artfully different. Still, in 1895, Bouguereau remained formidable, and his painting Alma Parens offered one of his last fully realized statements of purpose: a visual reaffirmation of the world he had spent a lifetime crafting.

The Patriotic Allegory of Alma Parens

Completed in 1895 and exhibited that year at the Paris Salon, Alma Parens—which can be translated as “Nourishing Mother”—shows a classically draped female figure embodying France, flanked by idealized youths representing her children. The allegory is literal and unambiguous: France as cultural nurturer, moral guardian, and civilizational womb. Every figure is modeled with Bouguereau’s signature smoothness; every gesture recalls a line of Virgil or an echo of Poussin. The composition is carefully balanced, the expressions serene, the message clear.

What stands out in Alma Parens is not innovation but insistence. Bouguereau was defending not only the aesthetic ideals of the École des Beaux-Arts, but also the idea that painting had a duty to ennoble and uplift. In the same Salon where Symbolist ambiguity, Impressionist looseness, and decorative modernism were gaining ground, Bouguereau presented a tableau of control, harmony, and moral confidence. Critics sympathetic to academic ideals praised the work as an “affirmation of French dignity.” Detractors called it “a beautiful echo”—suggesting not its failure, but its distance from the present.

The Weight of Mastery and the Crisis of Relevance

Bouguereau’s technical skill in 1895 was undiminished. His ability to render skin, fabric, and light remained nearly unmatched. He could still draw with accuracy that astounded his students, and he still held powerful sway over the juries of official exhibitions. But that year, as Alma Parens hung in the Salon, the atmosphere around him had changed. While conservative publications continued to extol his mastery, younger artists, critics, and even some collectors were beginning to speak in different terms—terms of atmosphere, mood, abstraction, and subjectivity. They were not calling Bouguereau bad; they were calling him irrelevant.

This tension—between continued dominance and perceived decline—was visible even in institutional politics. Bouguereau still held influence at the Académie Julian, where his students came from across Europe and the Americas to learn from a master. But many of them, including those who admired his skill, were more interested in Degas, Manet, and even the Post-Impressionists. His classroom had become a site of technical foundation, not stylistic allegiance.

What had once been viewed as moral seriousness in Bouguereau’s work now seemed to some like theatrical sanctimony. His religious and mythological scenes, always idealized, were increasingly described as “out of time.” In the fin-de-siècle climate of psychological introspection and social ambiguity, his crisp allegories looked less like affirmations and more like monuments to a lost order.

Between the Market and the Museum

Even as critical fashions changed, Bouguereau’s commercial appeal remained strong in 1895. His paintings were prized by wealthy American collectors, who saw in them a refinement and piety that matched their aspirations. Alma Parens, like many of his works, was widely reproduced in engravings and sold through dealer networks that catered to an international clientele. He was a global figure, not a provincial relic.

Yet that very popularity added to his troubles. To avant-garde artists and critics, his ubiquity made him suspect. He represented the commodification of high art, the equation of technical polish with artistic virtue. This view, emerging among Symbolists, Impressionists, and the nascent generation of Secessionists abroad, did not merely reject his style—it questioned the system that sustained it.

Still, Bouguereau did not waver. He had no interest in experimenting with composition or color for its own sake. He believed, as he always had, in drawing from nature, idealizing it, and presenting the beautiful as a moral good. “The more I work,” he once said, “the more I see things differently—everything seems simpler.” It was a credo that in 1895 sounded increasingly distant from the noisy ferment of modern art, but one that remained internally coherent and deeply rooted.

Twilight, Not Eclipse

In 1895, Bouguereau was nearing the end of his career—he would die in 1905—but he did not regard himself as a man out of time. He continued to teach, to exhibit, and to speak with authority in artistic matters. What had changed was not his confidence, but the world around him. The Symbolists were probing the unconscious; the Impressionists were dissolving light and form; the Nabis were flattening surface and symbol. Against this background, Alma Parens looked almost archaeological—a monument carved in the previous century, perfectly preserved but curiously mute.

Yet to dismiss Bouguereau in 1895 would be to misunderstand the structure of the art world at the time. He was not a footnote; he was still central, still powerful. His art may not have anticipated the avant-garde, but it provided a reference point against which new movements could define themselves. In some ways, the rejection of Bouguereau gave force to the alternatives. He was not defeated—only eclipsed by history’s changing angle of light.

Chapter 6: The Death of Berthe Morisot

In the first days of March 1895, Paris lost one of the quiet architects of modern painting. Berthe Morisot, a founding member of the Impressionist group and one of its most consistent exhibitors, died on March 2 at the age of 54. Her passing, while not unexpected—she had fallen ill while nursing her daughter during a bout of pneumonia—was met with real sorrow in the Parisian art world. More than a respected painter, Morisot was a bridge between eras: a close companion of Édouard Manet, a friend to Degas and Renoir, and a tireless practitioner of a vision that never sought attention yet consistently deepened its claims.

In 1895, the loss of Morisot was not simply the death of an artist—it marked the close of a certain Impressionist sensibility, one rooted in personal observation, domestic intimacy, and an unwavering belief in the expressive power of light.

A Style Formed by Restraint

Unlike many of her colleagues, Morisot did not trumpet her innovations. Her works rarely ventured into the grand gestures of modern life or mythic allegory. Instead, she focused on the interiors of homes, gardens, quiet corners of parks—scenes inhabited by women, children, and moments in between action. In these modest subjects, she developed a style that was technically daring: brushwork that hovered on the edge of dissolution, color that pulsed with atmosphere, compositions that balanced fluidity with emotional precision.

In the early 1890s, Morisot’s paintings had grown looser and more gestural, aligning more closely with the late works of Monet or even the interior studies of Bonnard. Yet her themes remained steady. A small portrait from the early 1890s shows her daughter Julie seated at a writing desk, half-turned, caught between attention and distraction. The light falls diagonally across the page she’s working on, catching the sleeve of her dress and the nape of her neck. It is a quiet painting, easily overlooked—but in its layering of glance, gesture, and light, it achieves a remarkable psychological intimacy.

Morisot’s Final Works and Unfinished Projects

In the months leading to her death, Morisot continued to paint, even as her health declined. Some canvases remained incomplete, but others, like Young Girl in a Park, display her late style at full strength: pale, silvery tones; airy, open spaces; and a subtle interplay between figure and environment. These final works, while less well known at the time, now stand among her most compelling—suggesting a direction that was being pursued with increasing boldness and restraint.

Her studio, after her death, became a site of private mourning and retrospective curiosity. Friends gathered to view her final pieces. Renoir and Degas visited; Mallarmé, who had been close to her family, spoke of her as “a soul open to beauty, rendered visible.” The atmosphere was not grand, but quietly reverent—fitting for an artist who had built her career not through declarations, but through persistent, searching observation.

Retrospective Recognition and Personal Loss

While Morisot had always been part of the Impressionist exhibitions, she had often been regarded as a kind of gentle presence—respected but never dominant. Yet in the wake of her death, a more serious reassessment began to emerge. Critics who had once written about her with polite admiration now returned to her work with fresh eyes. They noted the steadiness of her vision, the way she had never strayed from painting what she truly knew, and the technical sophistication that had gone largely unremarked while her male peers received accolades.

For those who had known her well, her death was personal as well as artistic. Mallarmé, who was the legal guardian of her daughter Julie after her passing, described Morisot as “the eye of clarity in a movement of haze.” It was not poetic exaggeration. Her work, while impressionistic, never dissolved into pure effect. It held to a core of reality—often filtered through private emotion—but anchored nonetheless in observation. She never courted scandal, never published manifestos. Her rebellion was quieter: a refusal to paint anything false.

Legacy Without Noise

In 1895, the art world was turning toward more self-conscious declarations. The Symbolists were invoking dreams; the academicians were summoning history; the modernists were dismantling form. Against this backdrop, Morisot’s final works felt like a kind of whisper—but one that lingered. She had helped shape the Impressionist vocabulary, not by imitation or theory, but through a personal fidelity to light, intimacy, and gesture.

Her death did not prompt public monuments or official mourning. But among those who had watched her paint year after year—without fuss, without slogans—there was a quiet understanding that something important had ended. Morisot had always been concerned with presence: the present moment, the presence of the body, the presence of light across skin or fabric. With her gone, that presence became absence—but one that continued to illuminate the work she left behind.

Chapter 7: The Market for Monet

In 1895, Claude Monet crossed a threshold that few of his contemporaries would reach: he became not merely respected or admired, but commercially formidable. The Impressionist rebellion of the 1870s, once mocked in newspapers and ignored by museums, had been absorbed—if not entirely accepted—into the broader structures of the French and international art world. At the center of that shift stood Monet, whose career was no longer defined by rejection or experimentation alone, but by a steady and deliberate orchestration of serial painting, commercial exhibition, and collector demand. The 1895 exhibition of his Rouen Cathedral series at Galerie Durand-Ruel was more than a success—it was a turning point in the history of modern painting as a marketable enterprise.

A Gothic Façade in Twenty Variations

In May of that year, Paul Durand-Ruel unveiled twenty versions of the west façade of Rouen Cathedral, painted by Monet between 1892 and 1894, then meticulously reworked in his studio at Giverny. Each canvas portrayed the same architectural subject, viewed from nearly identical vantage points but under shifting conditions of light, shadow, and weather. Sunrise, haze, cold mist, golden afternoon—the changes were not just meteorological but perceptual. Monet was not painting the cathedral; he was painting perception itself.

Visitors to the exhibition in 1895 were met not with a singular “statement” painting but with a rhythmic, hypnotic sequence. Critics were divided. Some praised the audacity of Monet’s vision; others saw the repetition as a symptom of artistic fatigue. Yet the viewing public responded with real curiosity. More significantly, collectors began to treat the works not just as individual pictures but as parts of a conceptual whole. Several were purchased by private buyers, and by the end of the year, interest had spread beyond France—especially to Britain and the United States, where Monet’s serial method resonated with collectors seeking both refinement and modernity.

Durand-Ruel’s Strategy and the Business of Modern Painting

Much of Monet’s success in 1895 cannot be separated from the long partnership he had built with Paul Durand-Ruel, the dealer who had championed Impressionism when it was still financially ruinous to do so. By the mid-1890s, Durand-Ruel had not only secured a viable market for Monet in Paris but had also established key footholds in London and New York. His method was calculated: solo exhibitions, coherent series, critical attention, and the cultivation of a client base that included industrialists, bankers, and American clubs with cultural ambitions.

The Rouen Cathedral show was the culmination of a strategy Durand-Ruel had been refining for over two decades: present Monet not as a spontaneous plein air painter, but as a disciplined master of atmospheric transformation. The commercial appeal of this approach was clear. It positioned Monet’s work as both decorative and intellectually serious, suitable for private salons and prestigious collections alike. In 1895, Durand-Ruel also began preparing for further Monet exhibitions abroad, buoyed by strong sales and growing critical acknowledgment.

Seriality as Innovation, Not Repetition

To modern viewers, Monet’s serial works might seem obvious in their logic: paint the same thing multiple times, show how it changes, underscore the fragility of vision. But in 1895, this was still a radical proposition. The Salon system had conditioned the public to expect narrative, resolution, and variety. Monet’s insistence on the sameness of motif challenged that. He was not just showing time’s passage; he was arguing that visual truth could not be captured in a single statement.

This idea had already appeared in his Haystacks series earlier in the decade, and would continue in his Poplars and Water Lilies. But with the Rouen Cathedral group, the subject itself added weight. The Gothic façade, a centuries-old symbol of religious and national identity, was here rendered ephemeral—its grandeur altered by the weather, its permanence undone by light. In Monet’s hands, the cathedral became not an anchor but a screen onto which time projected itself.

Some critics saw this as too clever, or worse, as a marketing device. But others understood its implications. The Revue des Deux Mondes praised Monet’s “courage to stay still and see more,” a subtle recognition that repetition was here a form of heightened attention, not mechanical reproduction.

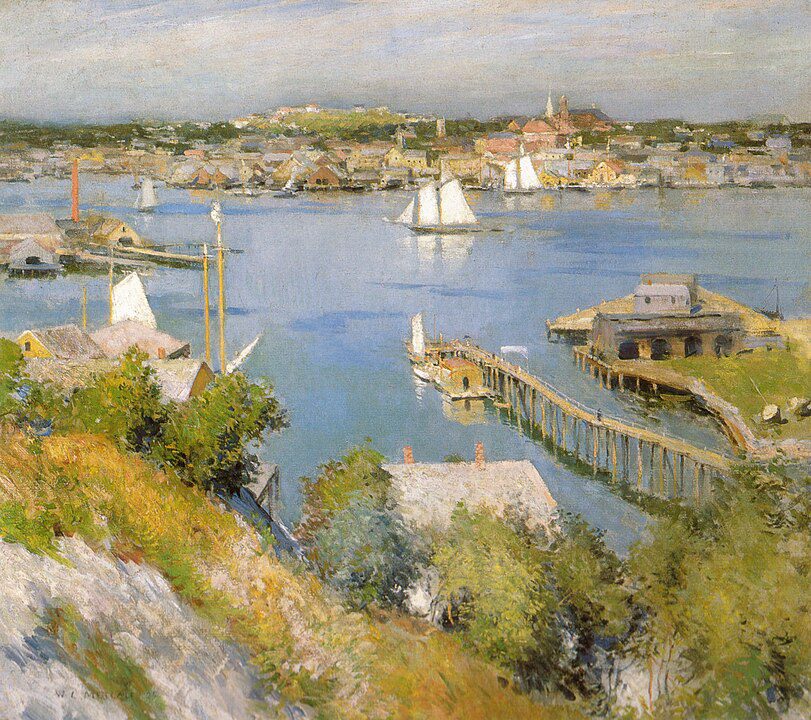

Monet and the American Eye

The success of the Rouen series in 1895 also accelerated Monet’s reception in the United States. That same year, works by Monet entered prominent private collections in Chicago, Boston, and New York. The Union League Club of Chicago, already a buyer of Impressionist works, acquired a Monet earlier that year, signaling a shift in what American institutions considered tasteful, modern, and respectable. Monet’s blend of atmospheric subtlety and structural clarity appealed to American collectors seeking to distinguish themselves from both aristocratic classicism and the gaudier end of academic realism.

Durand-Ruel’s American gallery helped position Monet as the modern heir to Turner—romantic, elemental, and grounded in natural spectacle. His paintings began to appear in American exhibitions not as foreign novelties but as exemplars of modern taste. By the end of 1895, Monet was no longer just a French painter with a loyal dealer. He was a transatlantic figure, his images of French cathedrals and Norman hayfields gracing the walls of American boardrooms and drawing rooms alike.

From Giverny to the Gallery

While collectors debated the Rouen series and critics adjusted their tone, Monet himself remained largely distant. He had long preferred the isolation of Giverny, where he continued to work obsessively, rarely attending his own openings and often deflecting praise with irritation. He once remarked that “only painting matters—everything else is the noise around it.” But in 1895, that noise had reached a volume impossible to ignore.

Monet was still evolving. His color harmonies were deepening, his touch looser, his vision more abstract. Yet 1895 marked a pause—a moment of consolidation, even self-justification. With the Rouen Cathedral series, he had proven that a lifetime of looking could become its own kind of subject, that to paint slowly and repeatedly was not to delay, but to see more completely.

It was the beginning of Monet’s late phase—but it already bore the weight and clarity of culmination.

Chapter 8: Aubrey Beardsley and the English Fin‑de‑Siècle

In the closing years of the nineteenth century, London found itself at the intersection of imperial confidence and cultural introspection. It was a city of gaslight and fog, of new wealth and ancient institutions, of crowded music halls and hush‑of‑a‑library contemplation. Into this world stepped Aubrey Beardsley, a young artist whose eloquent black‑and‑white drawings seemed to emerge not from nature, but from a cultivated dream of ornament, satire, and aesthetic excess. In 1895, at the height of his brief but incandescent career, Beardsley was both catalyst and symptom of an English fin‑de‑siècle—an age fascinated with surface, style, and the suggestion of the forbidden.

Aestheticism and the Art of Line

Aubrey Beardsley was born in 1872, and by his early twenties he had become one of the most recognizable figures in British graphic art. His signature style—intricate, flowing lines set against stark fields of black and white—rejected conventional illusionistic depth in favor of what might be described as calligraphic drama. Figures in his drawings twist and curl like smoke; patterns proliferate like arabesques. There was no mistaking a Beardsley: his work was both immediate in impact and endlessly dissectible in its formal cunning.

His rise was swift. In 1893, he became art editor of The Yellow Book, a quarterly literary and artistic review whose very color challenged Victorian moral propriety. The Yellow Book was neither pornographic nor prudish; it occupied a liminal space that invited speculation and scandal. Beardsley’s contributions—as both editor and artist—set its graphic tone. Within two years, his imagery had become a flashpoint for debate. Friends admired his ingenuity; enemies deplored his perceived decadence. By 1895, his work had become shorthand for a certain strain of English modernity—one that was ornamental, ironic, and disturbingly beautiful.

The Rape of the Lock and Erotic Wit

One of Beardsley’s major projects in the mid‑1890s was his illustration of The Rape of the Lock, Alexander Pope’s mock epic of aristocratic mischief. Beardsley’s drawings for this edition were a revelation: an iconography that fused eighteenth‑century wit with twentieth‑century edge. Fairies and aristocrats alike appear entangled in grotesque ribbons and filigreed patterns. The brittle humor of Pope’s poem—its satire of social pretension—found a new visual counterpart in Beardsley’s graphic excess. His figures are elegant and exaggerated, their limbs sometimes impossibly elongated, their gestures what might be called elegant distortions rather than realistic depictions.

The illustrations circulated widely in 1895, collected in deluxe editions that became prized by collectors and critics alike. They did more than adorn the text; they reframed it. The old pastoral of Pope was revealed, through Beardsley’s pen, as a play of surfaces and symbols—a choreography of signifiers rather than an illusion of narrative space. In other words, Beardsley was not simply illustrating a poem; he was translating its sensibility into a new visual language.

Controversy and Public Backlash

Yet for all his acclaim, Beardsley was no stranger to controversy. His work was frequently attacked in conservative newspapers and journals as indecent, perverse, or morally corrosive. The very abstraction of his figures—that is, their refusal to conform to naturalistic proportion or conventional beauty—became evidence, for some critics, of a corrosive modernity. It was not simply the content of his drawings, but their style, that was taken as emblematic of a cultural decay. In 1895, such accusations were as much cultural commentary as they were moral panic: they revealed the anxieties of an establishment confronted with forms that eluded easy categorization or control.

Beardsley’s reaction to these attacks was, at times, ironically self‑aware. He seemed to understand that his public persona—as provocateur, enfant terrible, and aesthetic innovator—was part creation and part projection. His letters from the period show a self‑conscious artist, attuned to both praise and censure, and eager—when healthy—to push further at the boundaries of taste.

Health, Mortality, and Artistic Intensity

Beardsley’s life was tragically short. Even as his star rose in the early 1890s, he was beset by illness, a consequence of tuberculosis contracted in childhood. By 1895, his health was fragile; he had relocated to the milder climate of the south of France in the hope of relief. Yet it was precisely in this period of physical decline that some of his most striking work emerged. The tension between the vibrancy of his imagination and the vulnerability of his body lent his late drawings a poignant intensity. Lines that once danced began to coil; ornaments that once flirted with pure decoration acquired a sharper, almost barbed quality.

Despite his illness, Beardsley continued to work prodigiously. His later drawings—especially those created in the shadows of convalescence—retain the playfulness of his earlier style but are tinged with a seriousness that belies their decorative surface. They seem to acknowledge, in their complexity, the finite arc of his own life.

Beardsley’s Legacy at Century’s End

In England by 1895, Aestheticism had become more than a fad; it was a lens through which artists, writers, and critics interrogated the very purpose of art. Beardsley’s contributions were central to this discourse. His work asked: Is art a mirror of life, or a life in itself? Can beauty be autonomous, freed from moral imperatives? And if so, what does that freedom cost?

Though he would die in 1898 at the age of 25, Beardsley’s influence outlived him. His graphic vocabulary—ornamental yet incisive, elegant yet unsettling—would reverberate into the twentieth century, informing Art Nouveau, modern illustration, and even later movements that prized line as a primary expressive element. In the fin‑de‑siècle moment of 1895, he stood at once within the artistic currents of his day and ahead of them, a visionary of form clad in the monogram of invention.

Beardsley’s art was not merely decoration; it was a kind of visual rhetoric—a statement about what art could be when liberated from academic precepts, and when grounded in the language of line, contrast, and imagination.

Chapter 9: Puvis de Chavannes and the Public Mural

In the France of the 1890s, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes represented a form of institutional idealism no longer fully aligned with its time. He was the painter of pared-down allegories, of muses and virtues set in pale landscapes, of frieze-like compositions rendered with restraint and solemnity. By 1895, he was widely regarded as the most important muralist in France—possibly in Europe. His work adorned the walls of major civic buildings: the Panthéon, the Sorbonne, the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Lyon, and, most recently, the Hôtel de Ville in Paris. But while Puvis’s murals still commanded admiration from officials and critics alike, the world around them had begun to ask different questions—about modern life, about psychological depth, and about whether public art could still speak with a single, authoritative voice.

The Salon de la Paix and the Idea of Harmony

Puvis’s mural cycle for the Hôtel de Ville, completed and installed in the early 1890s and still widely discussed in 1895, embodied his mature style: flattened perspective, simplified form, idealized anatomy, and a quietude that owed more to Poussin than to contemporary painting. The central work, The Sacred Grove, Beloved of the Arts and Muses, presents a vision of cultural harmony, with allegorical figures gathered in a serene, timeless setting. There are no dramatic gestures, no crowds, no specific historical references—only a suggestion of spiritual calm and civic order.

This was not merely aesthetic preference. For Puvis, the mural was not a canvas transferred to a wall, but a civic proposition. He believed that public art should elevate its viewers, not confront them; that it should unify, not provoke. His compositions were designed to be contemplative, permanent, and slightly removed from the noise of political life. The Hôtel de Ville, still recovering its symbolic importance after its destruction during the Commune in 1871, was an apt site for this vision—a place where allegory could stand in for stability.

Style and Stillness in a Restless Age

Puvis’s murals had their own rhythm, their own tempo. Figures stand or sit in calm dialogue; gestures are spare; trees do not rustle. This restraint was once read as nobility. But by 1895, younger critics and artists were starting to read it differently: as detachment, or even evasion. In an era when other painters—Redon, Denis, Gauguin—were exploring emotion, mysticism, and psychological depth, Puvis’s controlled surfaces began to look to some like willful reduction. He was not unaware of these shifts. Though generally aloof from factionalism, Puvis observed the growing prominence of Symbolist and Post-Impressionist tendencies and recognized their distance from his own values.

And yet, he held his ground. To his admirers, including conservative art critics and state commissioners, Puvis offered an alternative to the fragmenting energies of modernity. His murals became a model of what public art could still be: civic, legible, grounded in shared humanist ideals. His influence extended far beyond France. The American muralist John La Farge admired him; Seurat drew upon his compositional principles; the Vienna Secession would cite him in their early manifestos.

Public Commission as Cultural Contract

In the 1890s, the French state and city governments viewed large-scale murals not only as aesthetic statements but as instruments of public education and moral continuity. In schools, universities, museums, and municipal buildings, mural cycles were commissioned to express ideals—patriotism, virtue, knowledge, peace. Puvis was the painter best suited to this purpose. He knew how to compose for architectural space, how to balance imagery with architectural rhythm, and how to avoid topicality without drifting into vagueness.

His work in the Panthéon, for example, where he painted The Life of Saint Geneviève, used national history as moral parable. In the Sorbonne, he celebrated the idea of knowledge as a universal good. In Lyon, he adorned the Musée des Beaux-Arts with allegories of the Rhône and the Saône—an embodiment of place made myth. These works made no headlines, but they shaped the visual and moral environment of civic life.

By 1895, however, the context had changed. The Dreyfus Affair was beginning to polarize French society; Symbolism had displaced classical allegory in the galleries; Art Nouveau was reshaping the language of design. Puvis’s murals, once forward-looking, now looked serene to the point of stillness. They offered permanence in a time increasingly defined by volatility.

Legacy in Stone and Lime

Puvis de Chavannes died in 1898, only three years after the period under consideration. Yet in 1895, his reputation remained secure. He was president of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, a respected figure in academic and independent circles alike. His work had helped define the role of public art in the Third Republic. And his influence was not limited to those who imitated his style. Even those who rejected his ideals had to acknowledge the scale and seriousness of his achievement.

For all his classical bearing, Puvis’s contribution was not a return to the past but an attempt to construct a visual language appropriate to the public architecture of modern France. He sought timelessness, not nostalgia. Whether he achieved it is still debated. But in the mural cycle at the Hôtel de Ville—as in his best public work—he left behind a vision of harmony that was sincere, deliberate, and unusually clear.

In the rapidly fragmenting visual culture of the 1890s, that clarity may have been his most radical gesture.

Chapter 10: Whistler in London and Paris

In 1895, James McNeill Whistler stood on the far side of his controversies. The lawsuits, the aesthetic manifestos, the duels in print—all lay behind him. What remained was the work itself: muted, tonal, elusive. At the Goupil Gallery in London that year, a quiet exhibition of recent paintings and prints made it clear that Whistler’s art had entered a late phase—not diminished, but refined to the point of evanescence. If his earlier career had been marked by provocation, this period marked a withdrawal into mastery. He was no longer defining himself against others. He had become the thing others measured against.

A London Exhibition of Restraint

The 1895 show at the Goupil Gallery presented a selection of Whistler’s recent work, including landscapes, nocturnes, and prints. Gone were the explosive portraits of the 1870s, the sharp defenses of his aesthetic philosophy, the legal quarrels with John Ruskin. In their place stood paintings of architectural fragments seen through mist, riverside scenes rendered in silver and green, etchings that captured the worn edges of shopfronts or the drift of fog across the Thames.

Critics responded with a kind of cautious reverence. Even those who had once mocked his affectations began to recognize the quiet authority of his mature style. Whistler was, by then, one of the few living artists whose name alone could anchor a serious solo exhibition in London. Yet the show itself made no grand claims. There were no manifestos, no provocations. Only paintings and prints that asked viewers to slow down, to see with an attentiveness bordering on meditation.

Tonalism as a Form of Thought

Whistler’s approach in the 1890s might best be described not as a technique, but as a mode of attention. His works were not merely quiet; they demanded quiet from their viewers. He painted not subjects, but sensations. A grey wall, a dusk sky, a single bridge viewed through haze—all became acts of tonal calibration. Where others sought narrative or symbolism, Whistler sought harmony. He once compared his paintings to musical compositions, suggesting that their value lay in internal coherence, not in external meaning.

By 1895, this vision had matured. The edges of forms softened; color lost its assertiveness. He was no longer trying to persuade or shock. His paintings felt like private conclusions, made public only in the final gesture of display. This was not detachment, but refinement—a stripping away of everything that did not serve the image’s internal logic.

Paris, Prestige, and Distance

Though Whistler was American by birth and London-based for much of his adult life, his relationship with Paris remained significant in 1895. The French had long been ambivalent toward him. He was admired by some Symbolists, particularly for his etchings and lithographs, and had been an early influence on the Nabis. Yet the institutions of French art—especially the Salon—had never fully embraced him.

By the mid-1890s, however, Parisian dealers and collectors had begun to treat Whistler’s work with greater seriousness. His paintings were entering private French collections, and his prints were sought by connoisseurs who appreciated their technical precision and atmospheric subtlety. He was no longer part of the critical conversation in the same way as Monet or Redon, but he occupied a parallel space: not a rival to the avant-garde, but an antecedent—a proof that restraint could be radical.

Whistler himself remained wary of France’s art world. He maintained contact with Parisian friends and collectors, but showed little interest in reentering its institutional orbit. His quarrels with the Salon had left their mark, and he preferred the more flexible and private mechanisms of galleries like Goupil. Still, his influence was felt. Painters interested in tone and structure—particularly those around the Académie Carmen, where Whistler briefly taught—absorbed his lessons without necessarily declaring allegiance.

A Late Style Without Finality

Whistler’s work in 1895 does not resemble the late style of a painter retreating from the world. Rather, it reflects a deepening of principles he had long held. He had always believed in the supremacy of visual arrangement over subject matter. What changed in the 1890s was his handling of that belief: less defensive, less polemical, and more inward.

He painted fewer works, but with greater deliberation. His palette cooled. His brushwork became even more economical. The atmospheric became structural. The result was not a new direction, but a final affirmation of what he had always sought: an art that needed no explanation because it had nothing to prove.

Whistler would live another eight years, but 1895 marked a kind of artistic arrival. He was no longer seeking recognition, nor battling for space. He had his space, and he filled it not with declarations, but with arrangements of line, tone, and silence. It was a victory not of style, but of sensibility.

Chapter 11: Japanese Prints and European Collectors

In 1895, the presence of Japanese art in European collections had become unmistakable. What had begun in the 1860s as a trickle of imported woodblock prints and decorative objects had, by the last decade of the century, reshaped European taste, composition, and the very language of visual poise. Painters and designers assembled prints by Hiroshige, Hokusai, and Kunisada on their studio walls; collectors clamored for complete albums; dealers displayed them alongside French lithographs and etchings. The result was not mimicry but transformation: an integration of Japanese formal principles into European modernism that was at once selective and profound.

The Print That Reframed Vision

The Japanese woodblock print—ukiyo‑e—was first admired in Europe for its novelty: flattened perspective, bold outlines, and vibrant, unmodulated color seemed at odds with the illusionistic depth that dominated Western art since the Renaissance. By 1895, however, the novelty had worn off, and a deeper appreciation had taken its place. Collectors no longer saw these works as curiosities from a distant land; they felt, increasingly, that Japanese prints offered a challenge and a resource for rethinking pictorial space.

Artists in Paris and London began to borrow selectively from Japanese models. They took the bird’s‑eye cropping of figures and landscapes, the use of negative space to organize composition, and the rhythmic interplay of line and flat tones, without subscribing wholesale to any one style. Their works were not imitations of ukiyo‑e but responses to it. Japan’s visual language entered European studios as a kind of sensorium shift—an alternative grammar that foregrounded surface and pattern without sacrificing expression.

Collectors and the Market

The art market in 1895 was punctuated by a lively trade in Japanese prints, both old and newly imported. Dealers in Paris’s Rue de Rivoli and London’s West End offered bound albums, individual sheets, and related objects that blurred the boundaries between fine art and decorative design. Wealthy collectors competed for sets of Hiroshige’s Fifty‑Three Stations of the Tōkaidō, early impressions of Hokusai’s Great Wave, and rare works by Kuniyoshi. These prints were framed and displayed not as exotic souvenirs but as aesthetic statements in their own right.

Their circulation was facilitated by a growing number of European intermediaries who specialized in Asian art. Auction houses dedicated sale rooms to Japanese works; private dealers published illustrated catalogues; and art journals printed essays on the formal qualities that made these prints indispensable to the contemporary eye. For many collectors, owning Japanese prints was a mark of sophistication—an indication that one understood the new visual currents reshaping European art.

This market was not without its tensions. Questions about authenticity, condition, and provenance were pressing. European demand outstripped supply, and dealers sometimes resorted to retouching, recutting, or recarving prints to enhance their appeal. Yet even these dubious practices spoke to the fervor surrounding Japanese art: it had become both commodity and cornerstone, admired for its own sake and for the influence it exerted on European practices.

Artists as Collectors

Painters were among the most avid collectors of Japanese prints, not only because they appreciated their beauty, but because they saw in them analytical tools for rethinking composition. Monet filled his Giverny studio with them; Degas collected hundreds of sheets, studying their cropping and use of off‑centered figures; Toulouse‑Lautrec and Bonnard pinned prints next to sketches, letting their formal strategies circulate within their own work.

This presence was not passive. Artists internalized the prints’ structures. The way a branch cut across a page, or a figure was clipped by an unseen frame, taught European artists to reject the fixed middle ground that had dominated Western painting for centuries. Negative space became a partner to figure and ground; asymmetry became compelling. The effect could be subtle—an edge trimmed here, an unexpected patch of color there—but over years it reshaped the way European artists conceived of form, rhythm, and pictorial economy.

Public Exhibitions and Broader Reception

By 1895 there were also public exhibitions of Japanese art in Europe, some organized by museums, others by private societies dedicated to Oriental art. These shows attracted wide audiences: artists, writers, and the general public came to see prints displayed with lacquerware, textiles, and ceramics. Critics wrote about them not as curiosities, but as exemplars of a dignified, coherent artistic tradition.

European visitors who had traveled to Japan—adventurers, diplomats, scholars—wrote accounts that circulated in journals and books, adding ethnographic texture to the aesthetic discourse. Yet the interest was not purely scholarly. The emphasis was on formal qualities: how lines moved across the page, how color was compressed or expanded, how perspective was a tool rather than a rule. Japan’s artistic legacy was beginning to be understood as an alternative lineage, one that could illuminate European practice without obliterating it.

Integration and Innovation

The influence of Japanese prints did not lead to a single European “style” but to multiple appropriations: in compositions that defied centrality, in patterns that energized surface, in the interplay of light and shade that avoided chiaroscuro’s deep illusionism. The effects were visible in poster design, in book illustration, in fine art painting and printmaking alike.

In 1895 the dialogue between Japan and Europe was neither equal nor unproblematic. Japan itself was undergoing rapid change, opening ports, modernizing institutions, and negotiating its place in a world dominated by Western powers. Yet the prints that had traveled west continued to circulate in private collections and galleries, bearing witness to a transnational exchange that reshaped artistic understanding.

For European artists and collectors in 1895, Japanese prints were not relics of another world but catalysts for rethinking the familiar. They offered a new set of visual priorities—flatness alongside depth, rhythm alongside narrative, space as structure rather than illusion. In the interplay between Japanese form and European receptivity, a subtler modernism took shape, one that would endure into the twentieth century.

Chapter 12: Art and Photography — Atget, Stieglitz, and the Shift in Perception

In 1895, photography was still shadowed by a lingering debate: was it art, or merely a mechanical process? The question had hovered since the invention of the medium, but by the close of the century, it had become urgent. Painters, critics, and photographers themselves were confronting the expressive possibilities of the camera, not just as a documentary tool, but as a means of seeing—and shaping—modern life. Two photographers, working on opposite sides of the Atlantic, embodied this turning point: Eugène Atget in Paris, quietly documenting the city’s vanishing corners, and Alfred Stieglitz in New York, passionately asserting photography’s place among the fine arts. Though they would not meet, their work in this moment marked a shared shift in perception.

The Documentarian Without Theory

Eugène Atget was in his late thirties when he began to systematically photograph the streets of Paris. By 1895, he had begun the project that would occupy him for the next three decades: a vast, unsentimental visual archive of Parisian shopfronts, stairways, doors, fountains, alleyways, trees, and façades. Working alone, with a heavy wooden camera and glass plates, Atget created images that were, on the surface, practical. He sold them as reference material to painters, architects, and set designers. But the photographs themselves betrayed a deeper sensibility.

Atget’s images were precise, balanced, and untheatrical. He did not seek dramatic angles or picturesque scenes. Instead, he returned again and again to the overlooked: a shuttered shop window, a stone balustrade weathered by rain, a courtyard without people. Most of his scenes are empty, and where human figures do appear, they often seem incidental—blurred, in motion, peripheral. This absence creates an uncanny presence: a city without its bustle, stripped of its distractions, laid bare in light and geometry.

Though Atget did not call himself an artist, the photographs he made by 1895 already suggested a kind of visual poetics. They were factual without being cold, simple without being naive. In time, others would see in them the seeds of modern photography’s documentary aesthetic. But in 1895, they were simply available to whoever needed a picture of a cornice, a lamppost, or a garden gate.

The Advocate and the Eye

Meanwhile in New York, Alfred Stieglitz was constructing a very different role for the photographer: not a supplier of images, but a modern artist. He had studied in Europe, where photography was beginning to find champions in artistic circles, and returned to the United States determined to elevate the medium’s status. By 1895, Stieglitz was exhibiting, publishing, and organizing with single-minded clarity. He photographed snowstorms, fog, steam rising from horse-drawn carriages—urban scenes composed with atmospheric care, often blurred or softened to achieve painterly effects.

Stieglitz was not a documentarian. He pursued mood, tone, and visual rhythm. His prints were meticulously composed and printed, and he considered them objects of aesthetic value. Just as important, he wrote about them—asserting, in essays and editorials, that photography was not an inferior cousin to painting but a distinct form with its own expressive capacities. He resisted the idea that photography had to imitate other arts to be serious. For him, the camera was a tool of vision, and vision was never neutral.

This conviction shaped his entire career. In 1895, he was already preparing the ground for future institutions that would support photographic art: journals, societies, and galleries. He understood that photography’s struggle for recognition was not just about style—it was about systems of legitimacy. He would spend the next thirty years building those systems.

Different Aims, Shared Ground

Atget and Stieglitz seem like opposites. One walked the city with a practical purpose, largely ignored in his time. The other built an aesthetic movement around his images, becoming a prominent public figure. One photographed empty spaces; the other sought expressive light in crowded urban scenes. And yet, by 1895, both were responding to the same undercurrent: a growing sense that photography could describe not only appearances, but experience.

Atget’s pictures offered a Paris that was already slipping away—part memory, part fact. They were not nostalgic, but they carried the weight of observation over time. Stieglitz’s photographs, on the other hand, sought immediacy: the shimmer of light on pavement, the atmospheric density of steam or snowfall. Both used the camera not to copy the world, but to engage with it on new terms.

Their work from this period also pointed toward different futures. Atget’s quiet documentation would inspire generations of modern photographers—Walker Evans, Berenice Abbott, the surrealists—who saw in his images a kind of democratic vision: the poetry of the overlooked. Stieglitz’s legacy, in contrast, lay in his success at transforming photography’s institutional standing, giving it intellectual and artistic credibility within the structures of modern art.

Photography Joins the Conversation

In 1895, photography still lacked a permanent seat at the table. Museums showed few photographs; critics wrote sparingly about them; collectors still debated their value. But that was beginning to change. Atget’s careful eye and Stieglitz’s passionate advocacy, each in their own way, demonstrated that photography was no longer marginal. It was already part of how modernity saw itself: as fragment, as atmosphere, as fact tempered by feeling. The shift was not yet complete. But the conversation had begun.

Chapter 13: Conclusion — The Landscape of Art in 1895

To look at the year 1895 with clarity is to understand that modern art did not begin with a manifesto or a rupture, but with a drift. What passed that year under the surface—sometimes quietly, sometimes with scandal—marked not a singular break from tradition, but a redistribution of meaning, attention, and influence across a field that was rapidly becoming more plural, more international, and more unstable.

The Institutions Still Standing

At one end of that field stood the still-powerful institutions: the Paris Salon, the Académie des Beaux-Arts, and the figures like Bouguereau and Puvis de Chavannes who continued to occupy their centers. Their works were finished, controlled, elevated. They offered the public ideals—of the beautiful, the virtuous, the eternal. These ideals still held authority, but not without question. Even in the most celebrated Salon works of 1895, one hears a faint echo of fatigue: forms perfected so thoroughly that their relevance had begun to drift.

Competing Models Emerge

Elsewhere, new models were rising. The first Venice Biennale opened with national delegations and prizes, gesturing toward the internationalism and spectacle that would define the next century’s major exhibitions. The Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, and rival institutions across Europe, strained to offer alternatives to the academic machine. Artists like Klimt in Vienna and Munch in Berlin were not yet at their peak, but they were already fracturing the unity of institutional taste.

The Artist and the Market

Then there was the market. Monet’s exhibition of Rouen Cathedral paintings at Durand-Ruel in Paris showed that seriality—once a technical experiment—had become a viable commercial and critical strategy. Collectors, particularly in Britain and the United States, were now key actors in determining artistic prestige. Public museums still moved slowly, but private galleries moved fast, and artists increasingly shaped their careers around these circuits.

Divergence Instead of Consensus

Stylistically, the year was one of divergence rather than consensus. Redon pursued Symbolist inwardness, Beardsley sharpened the blade of aestheticism, and Whistler distilled tonal restraint into a philosophy. All three rejected grand narrative but in entirely different ways. Each was responding to the same crisis: the collapse of shared meaning in art. Their answers were personal, formal, and intentionally incomplete.

The Margins Gain Ground

What’s striking, looking across 1895, is how many of the most enduring figures were working on the margins of institutions they had once needed. Berthe Morisot, who died that year, left behind a body of work that never sought confrontation, but which now stands among the most perceptive accounts of perception itself. Atget walked the streets of Paris with no audience in mind beyond the artisans he sold to, yet laid the groundwork for an entire future of photographic seeing. Even Puvis, the muralist of civic virtue, found himself increasingly out of sync with the emotional turbulence brewing in galleries just a few miles from the Hôtel de Ville.

Art Without a Single Center

Art in 1895 no longer moved as a single body. It no longer served a singular patron—church, state, academy, or market. Its meanings were dispersed. The very idea of “progress” in art was fragmenting into a field of competing urgencies: modern life, inner life, national pride, aesthetic purity, spiritual longing, urban transience. Artists and audiences alike began to understand that these values could not be resolved into one image, or one style, or one exhibition.

The Year as Hinge

The year 1895, then, was not a beginning or an end. It was a hinge—a moment when the older structures still stood, but cracks had opened wide enough for new forms of art to pass through. What came after would look back on this moment not with nostalgia, but with recognition. This is when the conditions for modern art were no longer argued about—they were being lived.