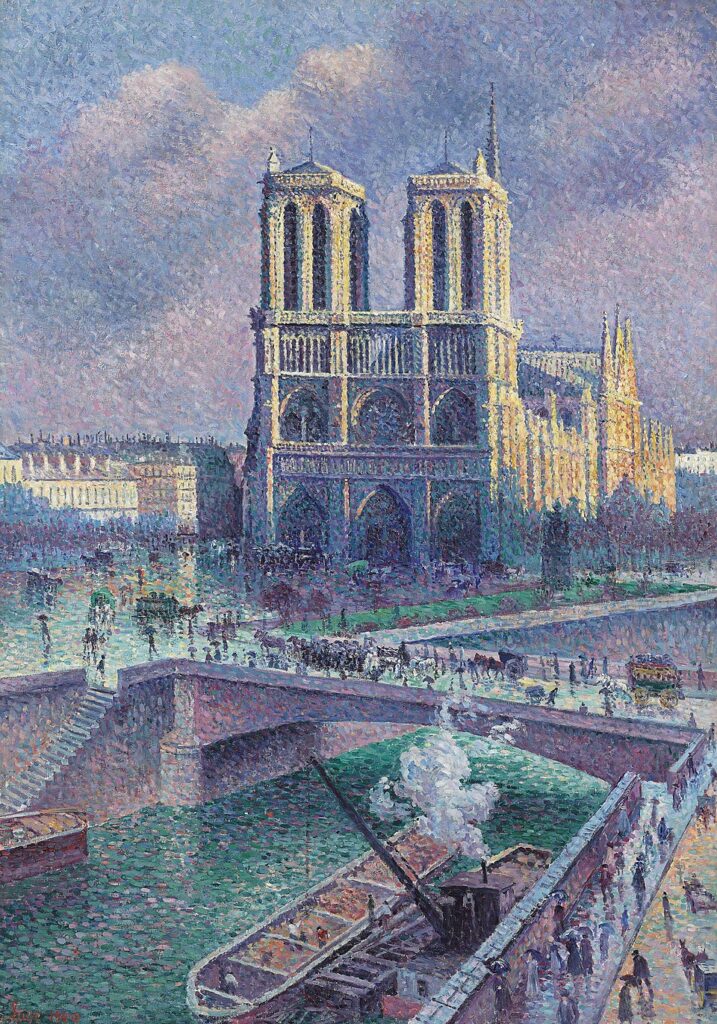

The year 1900 did not drift in quietly. It arrived with fanfare, fireworks, and a glowing Paris that seemed to proclaim itself the cultural axis of the world. Electric light had begun to replace gas in the grand boulevards, and the Eiffel Tower, now just over a decade old, blinked in the night sky like a monument to modernity itself. The Exposition Universelle, a world’s fair held from April to November that year, transformed the city into a stage for the future. With its moving sidewalks, domed palaces, and illuminated fountains, Paris offered a vision of art and industry walking hand in hand.

But the brilliance of the city lights did more than dazzle. It cast stark shadows. As the century turned, a subtle anxiety took hold beneath the surface of artistic life: What would come next? What should be preserved, and what left behind? Painters, sculptors, and architects were confronting both a world that seemed in constant acceleration and the burden of a 19th century that refused to vanish quietly. The air crackled with a dual current—of invention and uncertainty.

Many sensed that the old order had run its course. The academic art establishment still clung to its authority, but even inside its ranks, the ground had begun to shift. There was no single dominant style, only a growing restlessness with existing hierarchies and categories. It was an age of multiplicity, contradiction, and tentative beginnings—not yet the era of modernism proper, but unmistakably its overture.

Shadows of the 19th century: what lingered

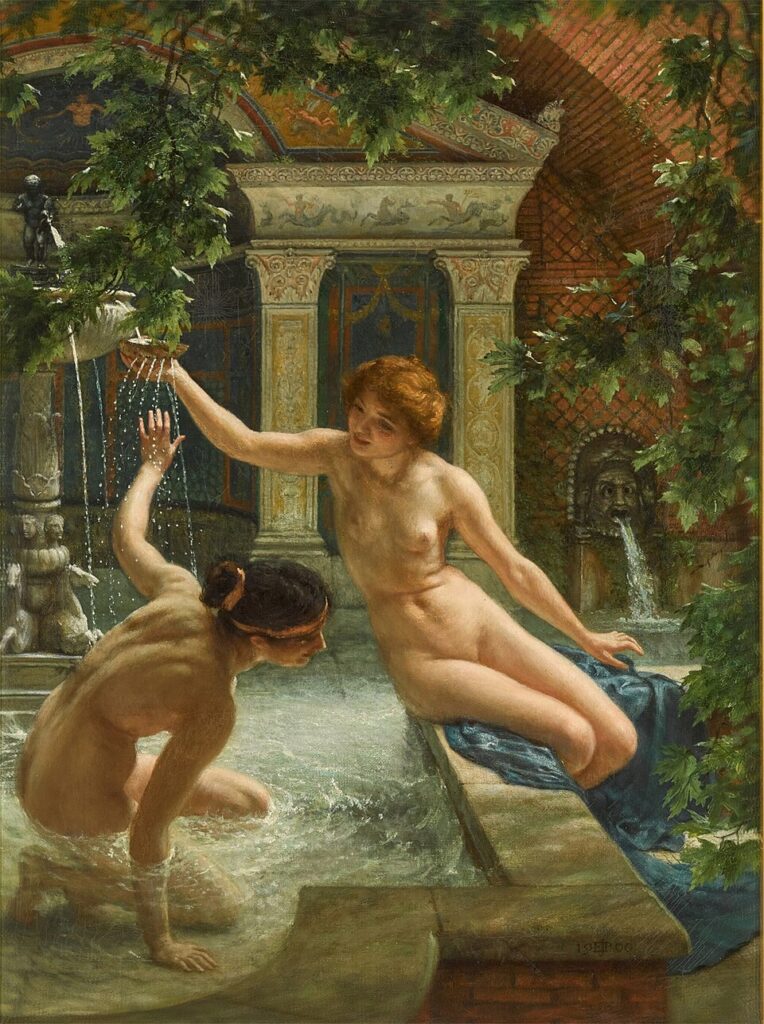

Despite the modern trappings, much of the visual world in 1900 still bore the imprint of the 19th century. The great salons in Paris, London, and Rome continued to favor historical painting, mythological allegories, and scenes drawn from classical antiquity. Artists like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Jean-Léon Gérôme remained stars in the academic firmament. Their canvases—smooth, sentimental, and technically immaculate—represented a conception of beauty as order, moral clarity, and idealized form. Their audience was broad, their patrons wealthy, and their influence widespread, especially in institutional settings.

At the same time, Impressionism—once the bane of the academy—had become almost respectable. Painters such as Claude Monet, then in his sixties, were no longer insurgents but revered masters. His Water Lilies series was underway by 1900, gradually shifting toward abstraction, even as critics and collectors were still catching up to the innovations of the 1870s. Edgar Degas, increasingly withdrawn from public life, had largely turned to sculpture and monotype, exploring the ballet and the female form with a new psychological intensity. The once-radical had been folded into the mainstream, though not without some distortion.

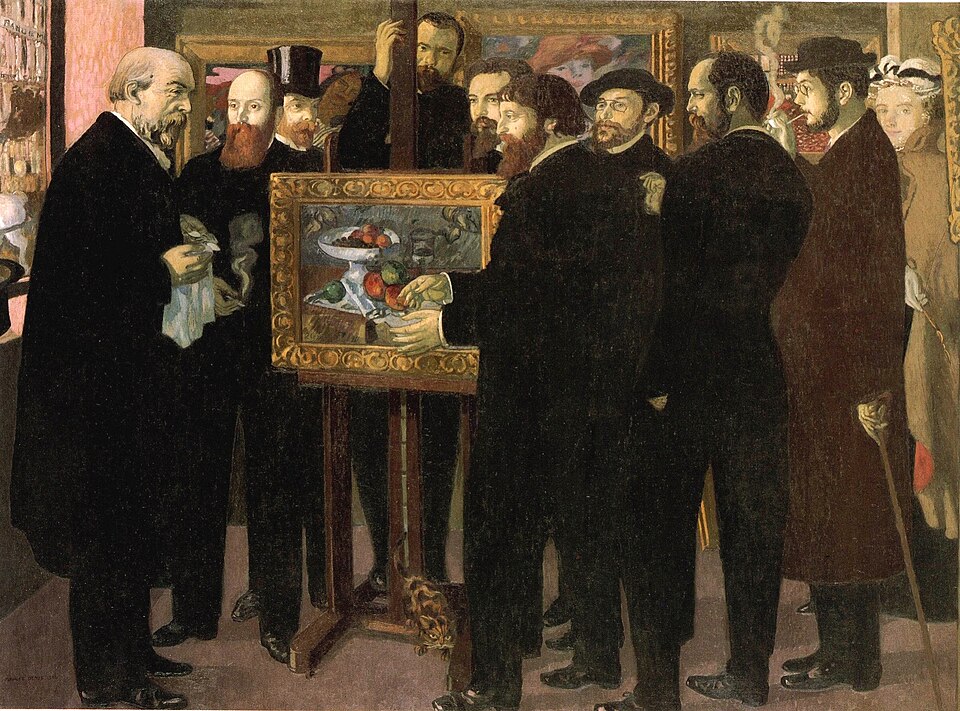

Even Post-Impressionists like Paul Cézanne, whose 1895 solo exhibition had stirred interest among younger artists, remained mostly under the radar of the general public. Cézanne lived in semi-seclusion in Aix-en-Provence, painting slowly and methodically. Though he had supporters—most notably Ambroise Vollard, who had organized that key exhibition—his formal innovations were still considered obscure by many critics. The art world at large remained conservative, and institutional gatekeeping ensured that the shock of the new reached only a limited audience.

Art as omen: early signs of rupture and reinvention

Still, for those with eyes to see, the future was announcing itself. The Vienna Secession had been founded just three years earlier, and in 1900, it was flourishing under the leadership of Gustav Klimt and Josef Hoffmann. Their journal, Ver Sacrum (“Sacred Spring”), was as much a manifesto as a magazine—declaring their intent to break with the stodgy Viennese academy and elevate design, architecture, and applied arts alongside painting and sculpture. The Secessionists borrowed freely from Japanese prints, medieval manuscripts, and Symbolist poetry, combining flatness with ornament, gold leaf with geometric abstraction. They pointed toward a new kind of beauty—spiritual, mysterious, and often unsettling.

In Belgium, Victor Horta’s sinuous interiors and wrought-iron details epitomized the Art Nouveau aesthetic, while in Paris, Hector Guimard’s newly installed Métro entrances curved like vegetal forms sprung from stone. Art Nouveau was less a unified movement than a sensibility, one that blurred the line between fine art and decoration, favoring elegance, natural forms, and anti-industrial flair. For its champions, it was a rejection of bourgeois vulgarity and mass-produced ugliness. For its detractors, it was decadence in disguise.

In the East, too, tremors were felt. Japan, rapidly modernizing since the Meiji Restoration, had become both a subject and an influence in the Western art world. The prints of Hokusai and Hiroshige had long fascinated European artists, but by 1900, they were also reshaping composition, line, and subject matter. The phenomenon of Japonisme continued to inform the visual grammar of the avant-garde, especially in decorative arts and poster design. Meanwhile, Japanese artists themselves wrestled with how to merge native traditions with Western techniques—giving rise to the nihonga style that would define the coming generation.

What emerged in 1900, then, was not a clear direction but a chorus of voices—some discordant, some harmonious, all vying for the authority to define what art should mean in the new century. The year stood not as a summit, but a threshold. One foot in the past, one foot in an uncertain future, the art of 1900 embodied a world both exhausted by its accomplishments and hungry for transformation.

And if the forms were not yet modern in the strict sense, the questions certainly were: What is beauty in an age of machinery? What role does the artist play when tradition no longer binds? And how does one paint truth in a century where truth itself is up for debate?

Those questions would not be answered in 1900. But they were being asked, quietly and persistently, in every atelier, gallery, and café. The answers, when they came, would change the world.

The Paris Exposition Universelle and the Art of Spectacle

Palaces of glass and iron: architecture as art

It was a monument to ambition, a temple of the modern age: the Exposition Universelle of 1900 stood as the single most significant cultural event of the year, not only in Paris but across the Western world. Drawing more than 50 million visitors over the course of seven months, the fair was an extraordinary convergence of national pride, imperial competition, artistic innovation, and sheer theatrical display. The architecture alone was a proclamation. Temporary yet towering structures like the Grand Palais and Petit Palais, both completed in time for the fair’s opening in April, demonstrated the full integration of art, technology, and architecture.

The Grand Palais, with its iron-and-glass barrel-vaulted nave, was not simply a site for exhibitions—it was a visual argument for modernism, even if the term had not yet taken on its later associations. It combined the classical vocabulary of Beaux-Arts ornamentation with the latest feats of engineering, using over 9,000 tons of steel in its construction. The building’s soaring interior nave hosted enormous sculpture and painting displays, presented under the filtered light of what felt like a greenhouse for culture. It was the largest exhibition space ever built in Paris, and in 1900, it was filled with visions of the world’s artistic and industrial might.

Across the Pont Alexandre III, itself a newly constructed marvel, stood the Petit Palais, a more ornate and decorative counterpoint, devoted largely to fine arts. Its colonnaded façade and mosaicked floors recalled imperial Roman grandeur, yet the building’s role was anything but retrospective. Within its walls, the French state gathered an enormous exhibition of both historical masterpieces and contemporary works, hoping to affirm France’s primacy as the world’s artistic capital.

The entire fairgrounds were a performance in steel and stone, water and electric light. Domes rose like planets along the Seine; bridges connected continents, literally and metaphorically. The Rue des Nations, a boulevard of national pavilions, allowed visitors to walk from Siam to Sweden, from Serbia to Spain, without ever leaving the banks of the river. It was a theater of empire and artistry alike, and no visitor could miss its message: the 20th century belonged to those who could marry beauty with power.

National pavilions and the performance of culture

Each national pavilion was a stage for self-presentation, and in that sense, the Exposition functioned as a global artistic audition. From sculpture and painting to architecture and applied arts, nations sought to assert both their cultural identity and their modern credentials. Some nations chose to showcase their industrial prowess. Others emphasized traditional crafts or national folklore. All were curated expressions of national character, with art enlisted as ambassador.

The Austrian pavilion, for instance, featured contributions from the Vienna Secessionists, including Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, and Josef Hoffmann. Though somewhat marginalized by the official Viennese art academy, their work stunned many visitors with its intricate decoration, mystical themes, and experimental techniques. Klimt’s allegorical works were dense with gold and symbolism, drawing on both Byzantine iconography and erotic tension. It was a bold divergence from the neoclassical idiom still dominant in many neighboring pavilions.

The Hungarian section likewise drew praise for its innovative mix of folk motifs and modernist forms. Architects like Ödön Lechner, sometimes called the “Hungarian Gaudí,” created works that combined eastern ornamentation with western structure—offering a distinct national modernism that stood apart from French or British models. Meanwhile, Finland, still under Russian control at the time, used its pavilion as a declaration of cultural independence. The architecture, designed by Eliel Saarinen, and the interior works by artists like Akseli Gallen-Kallela, were fiercely nationalistic, drawing on Nordic myth and nature to assert a unique identity.

In contrast, the American pavilion, styled as a colonial revival mansion, appeared cautious, even conservative. It prioritized sculpture and academic painting—representatives included Frederick MacMonnies and Edwin Blashfield—but avoided the more radical movements already bubbling in New York and Boston. It was a telling decision, one that underscored the cultural conservatism of the U.S. establishment at the dawn of the century, even as younger artists at home were experimenting with Ashcan realism and urban themes.

These national pavilions served a double function. They displayed the latest in each country’s artistic production, but they also mapped the geopolitical tensions and cultural aspirations of an increasingly competitive world. Art was not just for museums or galleries. At the Exposition, it was a tool of diplomacy, a language of prestige, and a statement of place in the new world order.

From peacocks to power cables: Art Nouveau on parade

If there was a single dominant style that defined the Exposition visually, it was Art Nouveau. Known by various names in different countries—Jugendstil in Germany, Stile Liberty in Italy, Modernismo in Spain—it found perhaps its fullest flowering on the fairgrounds of Paris. Wrought-iron vines climbed balustrades; floral mosaics covered fountains; typographic signage curled like fern leaves in the spring. Everywhere one looked, the natural world had been stylized and incorporated into the built environment.

The Pavilion of Decorative Arts, a massive structure co-organized by Siegfried Bing, the German-French art dealer who had opened the influential Maison de l’Art Nouveau gallery in 1895, presented an immersive environment of the style. Bing had a knack for combining Japanese art with modern European design, and his pavilion brought together works by Émile Gallé, Louis Comfort Tiffany, and René Lalique, among others. These were not merely objects to admire—they were products of a worldview in which function and beauty were inseparable.

Three particularly memorable displays stood out to critics and visitors alike:

- The Tiffany stained glass windows, with their peacock hues and iridescent glow, which married medieval craft with modern materials.

- Gallé’s botanical glasswork, in which acid-etched leaves and stems floated inside translucent vessels like pressed flowers preserved in amber.

- Lalique’s jewelry, fantastical and eerie, featuring insects, nudes, and enamel with a sculptural complexity that stunned even traditionalists.

Electricity itself was aestheticized. Illuminated fountains, lit by newly widespread arc lighting, turned water into liquid fire by night. The play of color, glass, and movement suggested a fusion of art and industry that seemed to define the spirit of 1900. Beauty, in this context, was not an escape from modernity but an articulation of it.

Of course, this unity of art and life would not last. Art Nouveau would be mocked by the next generation as overly decorative, even decadent. But in 1900, it represented a serious attempt to rebuild the visual world from first principles—to heal the rift between industrial production and aesthetic imagination.

For those who wandered the avenues of the Exposition Universelle, the future looked not like a machine, but like a garden of ornament, color, and light. That this vision would be so short-lived only adds to its poignancy. It was a dream at the edge of reality, just before the modern century would crash down with its wars, machines, and abstraction.

The Rise of Art Nouveau: Beauty as Rebellion

Whiplash curves and decorative dynamite

To many visitors of the 1900 Exposition, Art Nouveau seemed less like a style than a revelation. Its curling lines, vegetal motifs, and seamless integration of fine and applied arts offered a striking alternative to the tired academicism of the previous century. At its height, Art Nouveau aimed to transform not only how art was made, but where it lived: in furniture, wallpaper, architecture, typography, stained glass, jewelry, and even advertisements. It rejected the sterile separation between “high” and “low” art. Instead, it sought unity—a total visual experience. And beneath its elegant surfaces lay something far more radical than it first appeared: a rebellion dressed in flowers.

The formal language of Art Nouveau was instantly recognizable. Often called the “whiplash line,” its asymmetrical, sinuous curves imitated vines, smoke, seaweed, hair. The style invited motion and transformation—an aesthetic of flux, at once organic and ornamental. Yet behind the curves was a precise sense of design. Artists and architects working in this mode took nature seriously not as sentiment, but as structure. Their work studied how petals folded, how trees branched, how insects moved. The result was not imitation but stylization: nature abstracted, stylized, and reimagined into modern form.

This visual vocabulary could be found in the work of Hector Guimard, whose cast-iron entrances to the Paris Métro appeared like wrought-iron orchids, or in the posters of Alphonse Mucha, where diaphanous women floated through frames dense with floral arabesques and Byzantine halos. Mucha’s lithographs—especially his series for Sarah Bernhardt—were so influential that they were often mistaken as synonymous with the style itself, though his Czech heritage and Catholic mysticism lent them a particular flavor.

What made Art Nouveau more than decoration, however, was its defiance. In rejecting academic history painting and industrial ugliness alike, it proposed a third way—a modernism that was not mechanized, but humanized. Its practitioners believed that beauty was not merely a luxury, but a necessity. That every object, no matter how mundane, could be elevated by design. It was a doctrine of elegance with a conscience.

Vienna, Brussels, and the Slavic flourish

Though Paris was the symbolic heart of Art Nouveau in 1900, the style’s most fertile and original developments took place across Europe—in particular, in Vienna, Brussels, and the cities of the Slavic world, where the movement adopted distinct regional accents.

In Vienna, the Art Nouveau impulse crystallized into the Secessionist movement, formed in 1897 by a group of artists determined to break from the conservative grip of the Künstlerhaus. Their motto, carved over the entrance of their exhibition hall, read: “To every age its art, to art its freedom.” For these artists—led by Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, and Josef Hoffmann—the rejection of historicism was both aesthetic and moral. They sought a new synthesis of art, architecture, and craft, one that was abstract, symbolic, and rooted in the experience of modern life.

Klimt’s work from this period—such as Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence (painted for the University of Vienna ceiling, though now lost)—caused enormous scandal. Critics denounced them as grotesque and pornographic. But beneath the outrage was a deeper discomfort: Klimt’s vision was psychological, mythic, even apocalyptic. He stripped away the neoclassical veneer of reason and exposed the subconscious, the erotic, the tragic. His Art Nouveau was not just floral—it was fatal.

In Brussels, meanwhile, Victor Horta was revolutionizing domestic architecture with buildings like the Hôtel Tassel and Maison du Peuple, where staircases twisted like ivy and stained glass scattered golden light across hand-carved wood. Horta’s approach was total: every doorknob, wall sconce, and window latch was part of a coherent design. His buildings were not merely shelters—they were symphonies in stone and steel, choreographed down to the last detail.

Further east, in cities like Prague, Zagreb, and Kraków, Art Nouveau took on a more folkloric and mystical hue. The Polish artist Stanisław Wyspiański, for example, merged Symbolist drama with stained-glass and pastel work that drew deeply on Slavic mythology and Catholic liturgy. His theatrical designs and religious commissions fused local tradition with pan-European aesthetics, creating a uniquely Central European Art Nouveau that was neither Parisian nor Viennese, but something stranger and older.

These regional variants point to a key feature of the style: its adaptability. Unlike later modernist movements that often demanded total uniformity, Art Nouveau was a network, not a dogma. It allowed local artists to absorb and transform its vocabulary according to native histories and values. The result was a pan-European phenomenon that resisted imperial sameness.

The battle between ornament and industry

Art Nouveau’s ultimate ambition—total aesthetic integration—was also its greatest vulnerability. By insisting that beauty could live in every object, it demanded a level of craftsmanship that was costly, time-consuming, and incompatible with mass production. The style was, at its core, anti-industrial, or at least anti-mechanistic. It yearned for a return to hand-made dignity, even as it emerged in an age of factory belts and standardized parts.

This tension was not just philosophical—it was economic. Art Nouveau interiors, like those produced by Louis Majorelle or Carlo Bugatti, were exquisite but impractical for most consumers. Their sinuous furniture, inlaid wood, and elaborate joinery required artisan labor and expensive materials. Even in decorative arts, companies like Tiffany Studios could only reach elite clientele. There was a fundamental contradiction: the style dreamed of democratizing beauty, but often ended up cloistered among the wealthy.

Critics of the time—especially those aligned with emerging modernist currents—began to see the style as decadent. Adolf Loos, the Austrian architect and theorist, would later write his infamous 1908 essay “Ornament and Crime,” denouncing decorative excess as culturally degenerate and economically wasteful. Though he wrote it after the high point of Art Nouveau, the seeds of that critique were already being planted in 1900. For many forward-looking artists, the style’s ornamental complexity was starting to feel like a gilded cage.

Yet in 1900, those criticisms had not yet congealed into consensus. To many, Art Nouveau still felt urgent and alive. It offered a glimpse of what life might look like if art were not confined to canvases or museums, but flowed through every aspect of daily existence. A house, a teacup, a staircase, a brooch—all could be made with intelligence and grace.

Art Nouveau was not the future of art. But it was a necessary prelude—a declaration that beauty still mattered, even in an age of machines. And though its flowering was brief, its seeds would find strange and surprising soil in the years ahead, especially in the hands of those who, having once curved a vine in iron, would soon begin to bend space and time on canvas.

Vienna Secession in Its Prime

Klimt’s golden pivot

In 1900, Vienna was not merely a cultural capital—it was a paradox in marble. Beneath its operas, lectures, and palaces, the city seethed with contradiction: cosmopolitan and claustrophobic, rational and romantic, elegant yet anxious. Its artistic vanguard was not content to mirror this duality—they meant to unravel it. The Vienna Secession, founded just three years prior, had by the turn of the century fully matured into a movement of explosive originality. It was, in spirit and style, a declaration of independence from academic painting, aristocratic taste, and the dead hand of historicism.

At the center of this storm stood Gustav Klimt, who by 1900 had already abandoned the formal symbolism of his earlier murals and begun his journey into the gilded, erotic, psychologically charged canvases for which he would become famous. Klimt was not a manifesto writer. He avoided direct political engagement. But in his art, he practiced a kind of radical inwardness, bringing myth, desire, and mortality into vivid proximity.

His 1900 portrait Judith and the Head of Holofernes—often mistaken for Salome by contemporary viewers—marked a pivotal point in his career. Gone was the academic clarity of line and allegory. Instead, Klimt clothed his subject in gold and ambiguity. Judith’s half-lidded gaze, both seductive and repellent, hovers between triumph and trance. Her body seems to dissolve into a mosaic of pattern, while Holofernes’ severed head is almost incidental. The ornament, inspired in part by Byzantine mosaics Klimt had seen in Ravenna, is not mere decoration—it is the emotional terrain of the painting itself.

This was the beginning of his so-called Golden Phase, which would culminate in The Kiss (1907–08). But in 1900, this transformation was still fresh, even shocking. Klimt’s visual language—flattened space, symbolic motifs, erotic tension—broke with the illusionism of the 19th century without embracing the stark abstraction that would come later. It was its own frontier.

And it was made possible by the unique structure of the Secession, which freed artists like Klimt from the stranglehold of state commissions, imperial decorum, and critical orthodoxy. Inside the Secessionsgebäude, their custom-built exhibition hall crowned with a golden laurel dome, artists were allowed—at last—to speak with their own voices.

The rejection of historicism

The Vienna Secession was never a unified style. What bound its members was their shared resistance to the artistic and institutional establishment—especially the Künstlerhaus, Vienna’s conservative art society, which championed historical painting, portraiture, and bourgeois taste. In rejecting that tradition, the Secessionists weren’t just creating new art. They were inventing new ways to exhibit, to write, and to talk about art.

Their journal, Ver Sacrum, which launched in 1898, was a remarkable blend of criticism, poetry, illustration, and design. Its title, Latin for “Sacred Spring,” evoked both ritual and renewal—a deliberate invocation of artistic rebirth. The layout itself was revolutionary: asymmetric text blocks, borderless images, and experimental typography that prefigured modern graphic design. Contributors included not only Austrian artists and writers, but international voices—William Morris, Auguste Rodin, Maurice Maeterlinck—reflecting the Secession’s deep connection to broader European Symbolism and Arts & Crafts thinking.

Architects like Josef Hoffmann and Otto Wagner brought these ideals into three dimensions. Wagner, though slightly older than the core Secessionist group, had already broken from historicist conventions with his Stadtbahn stations—streamlined, elegant, and machine-inspired. Hoffmann, more aligned with the decorative sensibility of Art Nouveau, was instrumental in moving the group toward the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk—the total work of art. In this conception, the boundaries between architecture, furniture, graphic design, and painting were to be dissolved in favor of a coherent aesthetic experience.

By 1900, this idea was bearing fruit. In the Secession’s 7th exhibition—held that spring and devoted entirely to the work of Max Klinger—the display included not only paintings and sculpture but custom-designed walls, lighting, and catalogues. Nothing was accidental. Every element was curated to be part of a unified aesthetic encounter. It was a deliberate contrast to the crowded, salon-style exhibitions of the past.

For the Secessionists, historicism was not just outdated—it was dishonest. The past had become a prison of recycled motifs and empty gestures. Their solution was not to destroy the past, but to transcend it, by turning inward and forward at once.

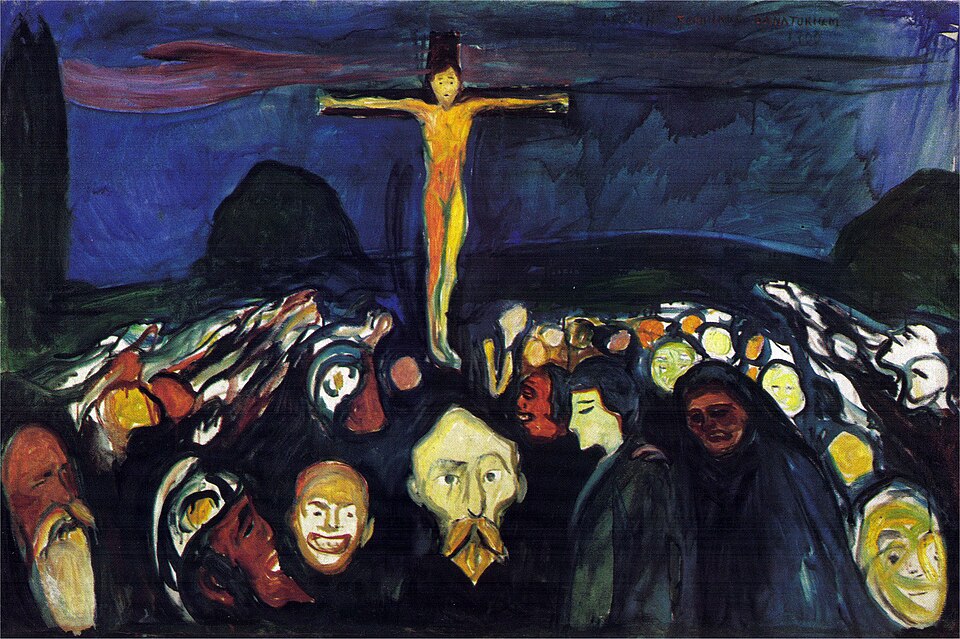

The Beethoven Frieze and the mythic impulse

One of the clearest expressions of the Vienna Secession’s philosophy came in 1902, just after the year in focus, with the group’s 14th exhibition dedicated to Ludwig van Beethoven. Though technically just beyond our timeframe, the project was being developed throughout 1900, and its themes—idealism, suffering, redemption—were at the very heart of the Secessionist vision.

Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze, painted directly onto the walls of the exhibition space, remains one of the most enigmatic and ambitious works of the era. Spanning over 100 feet, the frieze interpreted Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony as an allegory of human longing for happiness, threatened by the forces of violence, lust, and sickness, but ultimately rescued by Art and Love. It was mythic, not religious; symbolic, not narrative. Klimt’s figures—gaunt, golden, grotesque—stood in stark contrast to classical ideals of proportion or decorum. Their very distortion was a form of truth.

The frieze was never meant to be permanent. It was painted in casein on plaster, designed to be ephemeral—a gesture rather than a monument. But its impact was lasting. Critics were scandalized. Some denounced it as morbid, pagan, or degenerate. Others recognized its significance: a monumental act of modern myth-making, visual music on a scale that rivaled opera.

The Beethoven Exhibition as a whole, featuring a monumental sculpture by Max Klinger of the composer enthroned like a god, encapsulated the Secession’s ambition. Here was a total work of art, combining architecture, sculpture, painting, and sound. It was high Romanticism reinterpreted through the prism of psychological modernism.

What distinguished the Vienna Secession from similar movements across Europe was its philosophical weight. This was not ornament for ornament’s sake, nor rebellion for shock value. It was a serious attempt to restore art’s power to speak to the soul—not through nostalgia, but through formal innovation and emotional depth.

By the end of 1900, the Secession was no longer a fringe movement. It had become the intellectual and artistic epicenter of Central Europe. It would not last forever. Internal tensions, stylistic divergence, and the rise of more austere modernisms would soon fracture the group. But in that singular moment, around the turn of the century, the Vienna Secession stood as proof that beauty, symbolism, and modernity were not enemies. They could be allies—dangerous, alluring, and full of purpose.

Symbolism’s Final Bloom

The inward gaze: Moreau, Redon, and Khnopff

By 1900, Symbolism was already losing ground to newer artistic movements, but its final flowering that year was anything but a whimper. The Symbolists had never been a school in the academic sense, and they never sought broad popularity. They cultivated an art of suggestion rather than statement, mystery over message. Where the Impressionists had turned their eyes to the surface of the visible world, the Symbolists turned inward, toward myth, memory, dream, and the metaphysical. As the century turned, their influence reached a kind of twilight culmination—delicate, haunting, and fully aware of its own transience.

In Paris, the aging Gustave Moreau still held court as the movement’s high priest, though his influence was more pedagogical than painterly by that point. Having taught at the École des Beaux-Arts since the 1890s, Moreau was best known in 1900 not for new canvases, but for the students he shaped—most famously, Henri Matisse, who studied under him just a few years earlier. Moreau’s own myth-laden, jewel-toned paintings—Oedipus and the Sphinx, Salome Dancing Before Herod—were widely admired, though increasingly viewed as relics of a dying mode. Still, his devotion to the mysterious and the sacred left a deep impression on the generation to come.

Moreau’s heir in spirit was Odilon Redon, whose star was ascending in 1900. Redon’s charcoal drawings, known as his noirs, had long explored hybrid creatures, floating heads, and dreamlike landscapes, but around the turn of the century he moved increasingly toward color. His pastels and lithographs—like The Cyclops and Buddha—offered hallucinatory visions rendered with delicate softness, as if glimpsed through closed eyes. Redon’s work did not offer answers. It offered reverie.

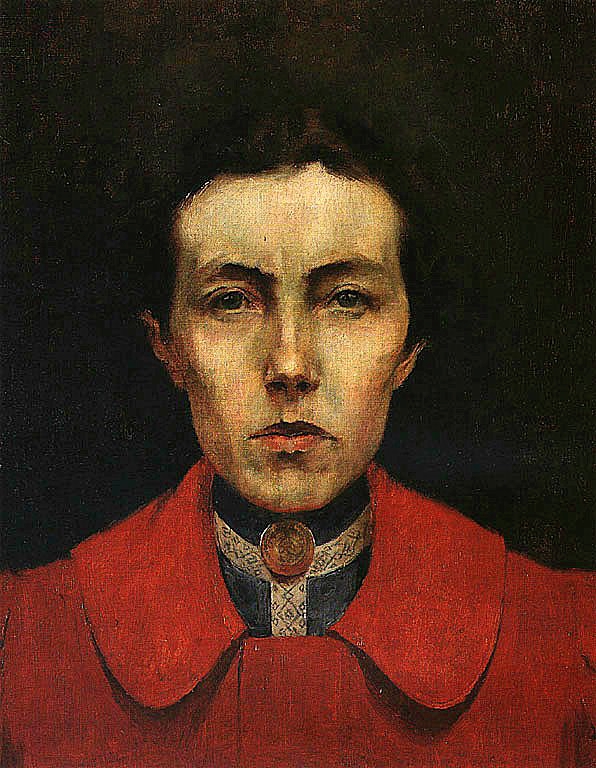

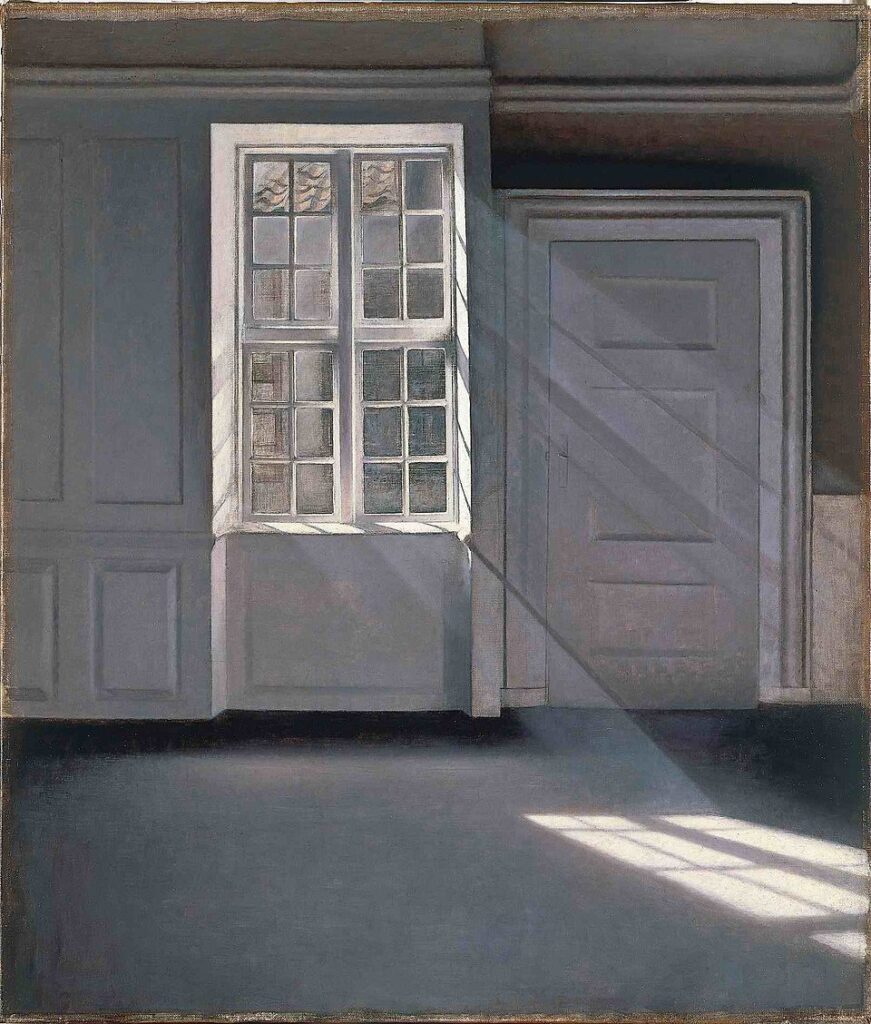

In Brussels, Fernand Khnopff was crafting an even more austere Symbolism. A solitary figure in both life and art, Khnopff painted with icy precision. His portrait of his sister Marguerite, repeated obsessively in various guises, became a kind of personal iconography. In works like I Lock My Door Upon Myself, the female figure is posed in a mood of spiritual detachment, encircled by emblems of stillness—mirrors, closed eyes, water lilies. His work rejected naturalism entirely; it sought, instead, a kind of painted silence.

What united these artists, despite their varied methods, was a shared suspicion of the visible world. They believed that the truest realities lay hidden beneath the surface—that truth was symbolic, not sensory. In this way, Symbolism foreshadowed both the psychoanalytic and abstract turns that would dominate later decades. Redon, Khnopff, and their kin were not painting facts. They were painting the soul’s weather.

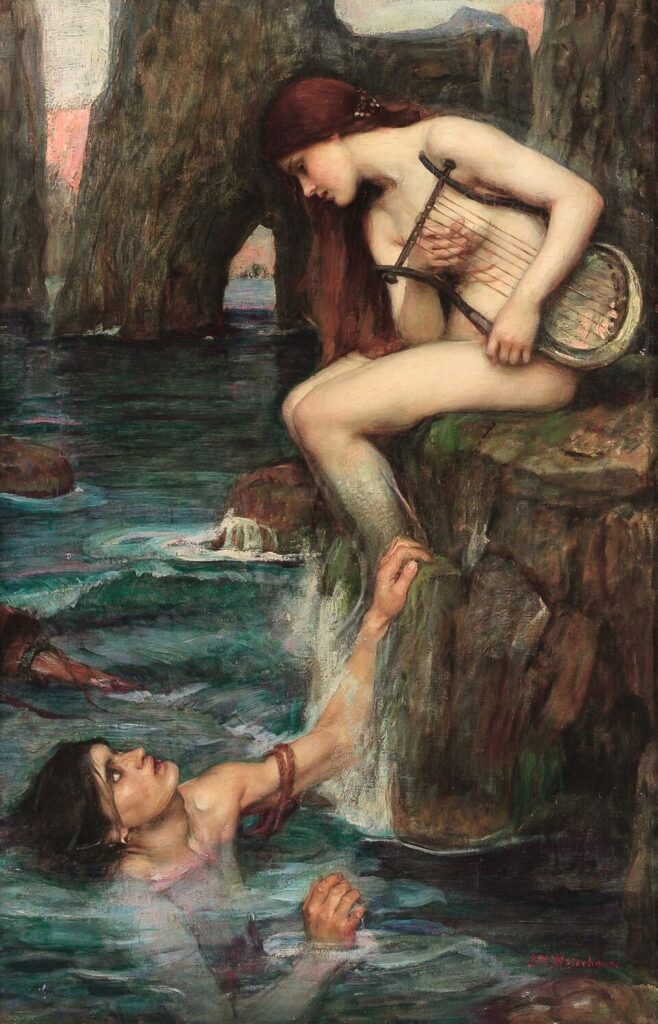

Dreams, death, and the divine feminine

Symbolist artists often returned to the same themes with near-liturgical regularity: dreams, sleep, memory, the femme fatale, the angel, the corpse. These were not mere tropes. They were archetypes, drawn from myth and literature, meant to evoke eternal conditions of the human psyche. And among these, none was more central than the figure of the woman—at once muse, mystic, monster, and mirror.

In 1900, the Symbolist woman had taken on a particularly dual aspect. She was no longer just the Pre-Raphaelite maiden or the academic Venus. She was often ambiguous, and deliberately so. The Belgian artist Jean Delville, for example, painted women as androgynous beings bathed in mystic light, figures of transcendence and terror. In his School of Plato, the ethereal female students sit in a classical ruin, their faces veiled in idealism. Yet behind the calm lies something unsettling—a spiritual elitism that disdains the material world.

Klimt, in Vienna, was painting women not as allegories of virtue or vice, but as forces: erotic, autonomous, and often destructive. His Judith, completed in 1901 but conceived the year before, was emblematic of this shift. In her gaze is not seduction for the viewer’s sake, but the certainty of her own dominance. She is no longer the object of narrative. She has become the subject.

Death was the other constant companion in Symbolist work. Not just as an end, but as a threshold. Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead, though painted earlier, continued to influence artists through countless reproductions, and its quiet, mythic grief echoed in the work of others like Carlos Schwabe, who illustrated the Death and the Maiden motif with a solemnity that veered into liturgical reverence. In these images, death is not grotesque. It is ritualized, purified, even desired.

The Symbolists’ preoccupation with mortality, sexuality, and transcendence made them deeply unfashionable among critics who prized clarity and progress. Yet this very refusal to participate in the optimism of the age gave their work a strange relevance. In the next two decades, as Europe slid toward war and spiritual crisis, their once-dismissed obsessions would appear prophetic.

The spiritual undercurrent beneath modern unrest

Despite their air of detachment, many Symbolists engaged deeply with contemporary religious and esoteric movements, including Theosophy, Rosicrucianism, and Swedenborgian mysticism. These currents, often ridiculed today, were widely influential in 1900 artistic circles. They gave artists permission to treat the canvas as a sacred space, not merely a picture plane.

Redon explicitly stated that his goal was to make the invisible visible. His spiritual vision was neither dogmatic nor doctrinal, but experiential—an attempt to convey states of grace or terror beyond the reach of language. His interest in Buddhism, Catholicism, and Eastern philosophy fused into a visual language of floating forms and radiant silence.

In Russia, too, Symbolism was gaining traction through the Mir iskusstva (World of Art) movement, led by Sergei Diaghilev and Alexandre Benois, with painters like Mikhail Vrubel embracing myth and fairy tale with feverish intensity. Vrubel’s Demon Seated, painted in the 1890s but still exhibited and discussed in 1900, showed a fallen angel writhing in a fractured, jewel-like landscape—part Byzantine icon, part fever dream.

These works were not escapism. They were forms of resistance—not against society per se, but against a conception of the world that reduced man to mechanism and the soul to sentiment. The Symbolists were not utopians. They were metaphysical dissenters.

By the end of 1900, Symbolism was already yielding to the formal innovations of Fauvism, Cubism, and Expressionism, all of which would soon dominate the avant-garde. But its twilight was radiant. It had introduced themes—interiority, myth, psychology, dream—that would not vanish but migrate, transforming themselves in new visual languages. In that sense, Symbolism did not die. It transmuted.

Even today, its fingerprints remain: in surrealism, in psychedelic art, in certain strains of fantasy illustration and esoteric design. The Symbolists believed that art could awaken us to what lies beneath appearances. In 1900, as the world rushed toward steel and speed, they offered one last whisper from the shadows—a reminder that mystery, too, is a form of knowledge.

Academic Art Still Reigning

The Salon’s enduring grip

Despite the ferment brewing in avant-garde circles across Europe, the year 1900 still belonged—officially, institutionally, and economically—to academic art. The grand traditions of the 19th century remained firmly in place within the most powerful exhibitions, schools, and salons. For the average museumgoer, collector, or critic of the day, the stars of the art world were not Klimt, Redon, or Cézanne. They were the polished, virtuosic painters who upheld the values of the academy: historical grandeur, technical mastery, moral uplift, and visual clarity.

The most prominent of these artists continued to exhibit at the Paris Salon—then officially under the auspices of the Société des Artistes Français—as well as at the Salon du Champ de Mars and the newly added fine arts displays within the Exposition Universelle. These venues still determined artistic prestige on an international scale. Acceptance into the Salon meant visibility. A medal meant sales. A state purchase, particularly for the Musée du Luxembourg or provincial museums, could secure an artist’s livelihood for life.

The tone and subject matter of academic art in 1900 were largely continuations of the previous century’s ideals. Paintings depicted biblical scenes, Greco-Roman myth, French history, or allegories of virtue and vice. Bodies were idealized, drapery was elaborate, and settings were composed to impress. Even when artists turned to contemporary themes, they often did so through a lens of moral clarity or narrative sentiment.

This was not mediocrity. The best academic painters of the time possessed a level of technical precision and compositional control that would humble most modern viewers. But their vision of art was rooted in hierarchy—of subject matter, style, and purpose. They believed that painting was not merely imitation or decoration. It was a form of instruction.

Yet for all their institutional dominance, cracks were beginning to show. The public, increasingly exposed to the strangeness of Art Nouveau, the mysticism of Symbolism, or even the freshness of Impressionism, was growing more skeptical of historical pastiche and rigid formulas. Some younger artists who trained in academic ateliers were beginning to defect—or to quietly evolve their style into something less bound by convention.

Still, in 1900, the academy remained the gatekeeper. Its taste defined the museums. Its prizes shaped careers. Its values, though increasingly challenged, were far from overthrown.

Bouguereau, Gérôme, and the defense of tradition

Two towering figures still embodied the height of academic excellence at the turn of the century: William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Jean-Léon Gérôme. Though their reputations would later fall into eclipse with the rise of modernist criticism, in 1900 they were not only successful—they were revered.

Bouguereau, then in his mid-70s, had long been associated with a style of polished, sentimental realism that appealed to both institutional buyers and private patrons. His paintings of peasant girls, angels, Madonnas, and nudes—such as The Bohemian or Birth of Venus—were executed with an almost photographic smoothness. Every toe, curl, and fold of fabric was rendered with loving exactitude. To modern eyes, these works can seem saccharine or insubstantial. But to contemporary audiences, they represented beauty, purity, and moral refinement. Bouguereau was especially influential in the United States, where collectors in Boston, Chicago, and New York prized his balance of grace and control.

Gérôme, slightly older and more polemical, occupied a different corner of the academy. Trained under Paul Delaroche and known for his sharp eye and ethnographic detail, Gérôme painted everything from gladiatorial combat and Napoleonic battles to harem scenes and religious spectacles. His style was leaner than Bouguereau’s, and often tinged with irony. In works like Pollice verso or The Execution of Marshal Ney, he dramatized the collapse of idealism in the face of power or cruelty.

By 1900, Gérôme had also become a powerful administrator and theorist, defending academic principles in writing as well as paint. He vocally opposed Impressionism, which he dismissed as careless and anarchic. For him, art was a craft, and modernity was no excuse for sloppiness or vagueness. His pedagogical influence was vast—his students included not only traditionalists, but many later innovators who absorbed his technique even as they rejected his ideology.

Though Bouguereau and Gérôme were both nearing the end of their careers in 1900 (Gérôme died in 1904), they were still present in the public mind as exemplars of taste. Their portraits hung in prominent museums. Their names carried weight at juries and academies. They were the standard against which both admiration and rebellion were measured.

Aesthetic orthodoxy meets photographic precision

The visual language of academic art in 1900 was anchored in illusionism, but increasingly informed by the optical realism of photography. While academic artists had long resisted photography’s artistic legitimacy, by the end of the century, many had incorporated its insights into their own practice—sometimes subtly, sometimes quite directly.

One could see this especially in large-scale compositions: battle scenes, ceremonial portraits, crowd-filled historical panoramas. Artists used photographic reference to capture accurate anatomy, architectural detail, or lighting conditions. Some used photographs as preparatory studies; others even projected them onto canvases as guides. The camera became a secret collaborator—discreet but indispensable.

Yet this relationship remained uneasy. The academicians wanted to retain the moral superiority of hand-made image-making. Painting, in their view, was more than replication. It had to elevate, to interpret. To merely copy a photograph was vulgar. The ideal remained a kind of enhanced realism: clearer than reality, more orderly than nature, and suffused with symbolic resonance.

A few artists bridged this divide with great skill. Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, for example, combined photographic precision with religious themes in works like Breton Women at a Pardon. His method involved meticulous studies and photo-based compositions, but the result was painterly, not mechanical. Similarly, Jean-Paul Laurens brought a stern moral intensity to historical scenes that combined drama with documentary accuracy.

The growing sophistication of Pictorialist photography—which aimed to make photography painterly—further complicated the boundary. Exhibitions in Paris and London in 1900 showed photographs that mimicked the softness, tonality, and compositions of academic painting. The arts were beginning to circle one another, each asking the same question in different languages: what does it mean to represent reality?

By the end of 1900, the visual coherence of academic art still held, but the ground beneath it had begun to tremble. New movements were not only challenging its subjects and techniques—they were challenging its entire philosophy of art: its belief in hierarchy, narrative, moralism, and clarity.

For now, the statues still stood. The prizes were still awarded. The salons still opened with fanfare. But the revolution had already begun—in quiet studios, in strange new canvases, in younger artists turning their gaze not outward, but inward. The academy did not know it yet, but it was already living on borrowed time.

The Modernists Still Underground

Cézanne’s quiet revolution

If the Paris art world in 1900 still revolved around salons and academies, a quieter, more seismic shift was occurring far from the capital’s formal exhibition spaces. In the sun-washed hills of Aix-en-Provence, Paul Cézanne—already in his sixties—was conducting a solitary campaign to transform the foundations of painting. His work was largely ignored by the public and derided by many critics. Yet for the generation of younger artists gathering around Parisian studios and galleries, Cézanne was beginning to assume the stature of a prophet.

He did not exhibit at the Exposition Universelle. He was absent from the salons. But those who had seen his 1895 solo exhibition at Ambroise Vollard’s Paris gallery understood something extraordinary was happening. In 1900, Vollard continued to represent Cézanne’s work—landscapes, still lifes, and bathers painted with unorthodox structure, muted palette, and patient force. These canvases did not seek to capture light, like the Impressionists, but form. Cézanne painted as if the world were made of cylinders, spheres, and cones—and as if space itself could be reshaped through color and brushwork.

The critics often missed the point. One review that year called his work “bricks and blotches.” But painters were watching more carefully. For Henri Matisse, who visited Vollard’s gallery repeatedly, Cézanne offered a path out of both academic orthodoxy and the dissolving surfaces of Impressionism. His ability to flatten space without collapsing it, to render solidity without outline, would become the basis for Cubism, Fauvism, and beyond.

Cézanne’s revolution was not polemical. It was slow, internal, and cumulative. He did not write manifestos. He painted. One fruit bowl at a time. One mountain at a time. By 1900, his Mont Sainte-Victoire series was well underway, with the Provençal landscape becoming not just a motif, but a battleground—between perception and abstraction, between geometry and atmosphere.

His influence would not explode until after his death in 1906. But in 1900, Cézanne was already reshaping the language of painting. Silently, relentlessly, and with a sense of purpose that made him the true keystone of modernism—still unseen by the public, but increasingly indispensable to those who would define the next generation.

Matisse before Fauvism

Henri Matisse in 1900 was not yet a Fauvist. He was still searching—technically proficient, but aesthetically uncommitted. That year, he exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants and the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, where his work received modest attention. He painted domestic interiors, portraits, and the occasional landscape, often in a palette and manner not far removed from his academic training.

But beneath that surface, something was beginning to shift. His exposure to the work of Cézanne, van Gogh, and Gauguin—especially through Vollard’s gallery—was breaking apart his inherited visual language. So was his discovery of non-Western art, including Islamic ornament, Japanese prints, and African sculpture, which would become central to his vision in later years.

In 1900, Matisse was still digesting these influences. His self-doubts were profound; he destroyed many canvases. His brushwork was cautious compared to what it would become, but the first signs of his future liberation were visible. Works like Still Life with a Pewter Jug and The Dinner Table show a growing interest in pattern, bold color, and compositional flatness.

Matisse also spent part of that year teaching drawing, struggling financially, and reflecting on his own direction. He was not part of any group yet. No manifesto, no school. But the seeds of Fauvism, which would erupt in just five years, were germinating in these modest, experimental works.

1900 was Matisse’s crucible—not the year of his breakthrough, but the year of his discontent. It was the quiet forge in which his radicalism began to take shape—not through flamboyance, but through a slow, almost painful process of unlearning.

Young Picasso in Barcelona

In 1900, Pablo Picasso turned nineteen. He was living in Barcelona, immersed in the cafés, cabarets, and anarchist conversations of the city’s bohemian quarters. Still known as Pablo Ruiz Picasso, he had begun to sign his works simply “Picasso”—a signal of his growing independence from both paternal lineage and academic restraint.

That year marked a major transition. In February, he had his first exhibition at Els Quatre Gats, the famous modernist café modeled on Paris’s Le Chat Noir. His paintings were moody, dark, and dominated by blue and green tones—early signs of what would become his Blue Period, although the defining works of that phase would not appear until 1901.

His 1900 paintings combined academic solidity with Impressionist softness and Symbolist melancholy. Works like Science and Charity (painted a few years earlier) still bore the hallmarks of Spanish Realism, but he was moving quickly toward something more lyrical and expressive. His notebooks from this time are filled with sketches of performers, beggars, and street life—subjects that would dominate his early Paris years.

In October of 1900, Picasso made his first trip to Paris, visiting the Exposition Universelle and absorbing the city’s energy. He was overwhelmed by the scale, the variety, and the sophistication of the art world. He visited galleries, studied Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec, and began to see the outlines of a broader horizon. His time in Paris was brief—he returned to Barcelona before year’s end—but it changed him.

From this point on, Picasso’s development would be astonishingly rapid. But in 1900, he was still between worlds: between Spain and France, tradition and experiment, adolescence and authority. His work was uneven, but vibrant—charged with ambition and latent innovation.

Critics did not yet know his name. Dealers had not taken notice. But among a small circle of artists in Barcelona, it was already clear: Picasso was not merely talented. He was dangerous.

Women Artists Push Boundaries

The Red Rose Girls and American illustrators

In the world of 1900, a woman could model for art, inspire it, or serve as its allegory—but rarely was she invited to create it on equal terms. Art schools had begun admitting women by the late 19th century, but the path to serious recognition was obstructed by social custom, institutional bias, and the commercial structures of the art world itself. And yet, even within these constraints, women artists were making real headway. Not through rebellion alone, but through sheer discipline, skill, and strategic collaboration.

In Philadelphia, a group of American women known as the Red Rose Girls had carved out a place for themselves in the male-dominated world of illustration. Jessie Willcox Smith, Violet Oakley, and Elizabeth Shippen Green—all students of Howard Pyle at Drexel Institute—were commissioned to illustrate books and magazines for mainstream publishers, including Harper’s, Scribner’s, and The Ladies’ Home Journal. Their style was narrative, decorative, and rich with a kind of moral imagination. In a field still considered commercially acceptable for women, they excelled—and in doing so, elevated illustration into the realm of fine art.

In 1900, these three women moved into the Red Rose Inn, a shared home and studio near Villanova, Pennsylvania. It was more than a domestic arrangement. It was a professional alliance. Their success was no accident: they cultivated a working environment that was orderly, industrious, and socially conscious. Oakley, in particular, would go on to paint monumental murals in the Pennsylvania State Capitol—the first woman to receive such a commission.

Their work was never radical in content. It focused on childhood, motherhood, spiritual virtue, and the idealized female form. But the professionalism with which they pursued their careers—and the quality of their draughtsmanship—made a quiet mockery of the idea that women were unfit for serious artistic labor.

In this, they were not alone. Kate Greenaway in England and Beatrix Potter, whose Peter Rabbit was just beginning to gain traction in 1900, demonstrated that women illustrators could combine charm with artistic intelligence. Their influence would prove long-lasting—not just in publishing, but in how the visual imagination of early childhood was shaped in the modern West.

Käthe Kollwitz and graphic grief

If the Red Rose Girls represented the cultivated domestic virtues of womanhood, Käthe Kollwitz represented its furious compassion. Born in Prussia in 1867, Kollwitz came of age under Bismarck’s conservative regime but brought to her work a deep sense of social empathy and visual severity. By 1900, she had already gained significant attention in Germany, especially for her graphic cycles depicting the plight of the working class.

That year, her print series A Weavers’ Revolt (1893–97) was already circulating in exhibitions and publications. In these works, Kollwitz used etching, lithography, and woodcut not for decoration but for denunciation. Her lines were rough, urgent, and deliberately unpretty. Faces were wrinkled. Bodies sagged. Death, hunger, and defiance hovered on every page. She was not interested in showing women as objects of desire or symbols of virtue. She showed them in mourning, in rebellion, in childbirth, in grief.

Her style owed something to Goya, something to Millet, and much to her own moral clarity. In a period when most academic art still clung to historical costume and classical proportion, Kollwitz’s peasants and widows looked startlingly contemporary. They were not idealized. They were not allegorical. They were real.

And yet, despite the darkness of her themes, Kollwitz never surrendered to despair. Her works insist on dignity, resistance, and shared suffering—not as propaganda, but as witness. She lost a son in the First World War and later became a fierce critic of militarism. But even in 1900, one could sense in her work a prophetic grief.

Kollwitz was a rarity in more ways than one: a woman artist recognized by national academies (she became the first woman elected to the Prussian Academy of Arts), and a political artist whose imagery transcended ideology through sheer visual truth. In the masculine world of social realism, she staked a claim with unflinching grace.

Mary Cassatt’s twilight period

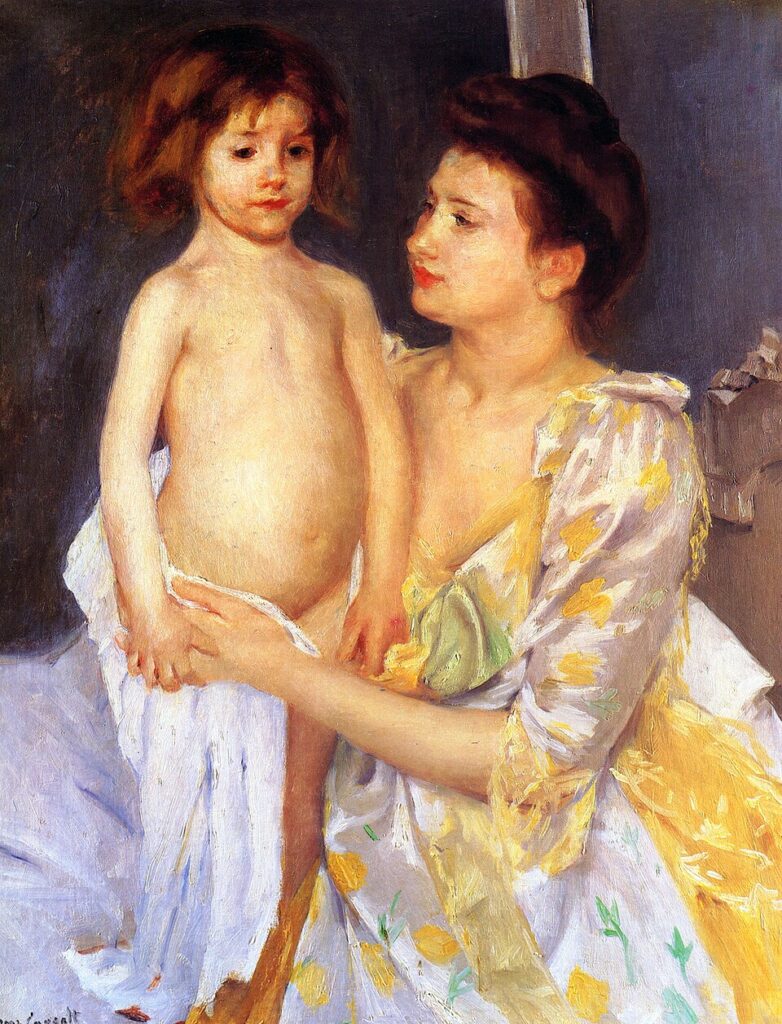

By 1900, Mary Cassatt was entering the final chapter of her career. At 56 years old, she was no longer the fiery American disciple of Degas, challenging the male Impressionists with her steady hand and uncompromising gaze. Her vision had softened—but it had also deepened. Her brushwork grew more luminous, her compositions more inward. She painted not with rebellion, but with confidence earned through years of quiet defiance.

Cassatt did not exhibit at the Exposition Universelle in 1900. But her reputation in France remained strong, and she continued to be collected and shown in both Paris and the United States. Her subjects remained what they had always been: women and children, painted not as sentimental icons but as thinking, breathing individuals. Her 1890s work, including The Bath and Young Mother Sewing, still held influence in 1900, particularly among American collectors seeking to bring European sophistication home.

Cassatt’s vision of womanhood was distinct. It neither eroticized nor idealized. She painted maternal intimacy with extraordinary subtlety—never posed, never saccharine. Her figures, often absorbed in mundane activity, conveyed a quiet strength and autonomy that set her apart from both the Symbolists and the Academics.

In 1900, Cassatt was also increasingly engaged in women’s suffrage, contributing works to exhibitions and charities supporting the cause. Her private life was reclusive, but her sense of duty to her sex remained acute. She believed that art could uplift women—not only by representing them differently, but by enabling them to see themselves differently.

Though her eyesight would soon begin to fail, and her painting would slow, Cassatt in 1900 stood as a pillar of integrity and craft. She had carved out a space in the Impressionist movement without compromising either her gender or her intellect. And her legacy was already beginning to inspire a generation of younger women artists on both sides of the Atlantic.

Photography as Art and Archive

The pictorialist experiment

At the dawn of the 20th century, photography stood at a cultural crossroads. Technically over sixty years old, the medium had evolved far beyond its primitive origins. By 1900, it was everywhere—from scientific laboratories to family albums, police records to commercial advertising. But for those who saw in it more than documentation, photography was also becoming something else: a fine art, capable not only of depicting the world, but of interpreting it.

The Pictorialist movement emerged in the 1890s as the dominant artistic tendency in photography. In 1900, it was still in full bloom. Pictorialists aimed to elevate the photograph beyond mere mechanical record by imbuing it with mood, composition, and craft—drawing inspiration from painting, especially Symbolism, Tonalism, and Impressionism. Their images were often softly focused, deliberately staged, and printed with elaborate techniques that emphasized atmosphere over accuracy.

Photographers like Robert Demachy in France, Frank Eugene in Germany, and Gertrude Käsebier in the United States used gum bichromate, platinum, and carbon printing to manipulate tone and texture. Some even scratched or brushed the surface of the negative to achieve painterly effects. Demachy’s Struggle (1900), for instance, evoked the raw muscle of Michelangelo in soft gray haze, blurring the line between sculpture and smoke.

Critics were divided. Some dismissed these works as mere imitation of painting, a photographic inferiority complex. Others saw in them a genuine effort to expand the medium’s expressive power. The Linked Ring in London and the Photo-Club de Paris supported this vision, organizing annual salons that exhibited photographic prints on par with oils and watercolors. These salons often borrowed the style and atmosphere of the Symbolist exhibitions: subdued lighting, minimalist framing, hushed reverence.

Though often sentimental or idealizing in subject, Pictorialist images were serious in ambition. They depicted:

- Solitary female figures, bathed in allegorical light, evoking purity or sorrow.

- Landscapes swathed in fog, where horizon lines vanish into mood.

- Portraits of artists or children, carefully posed in three-quarter light to evoke depth and dignity.

Photography was not just catching up to painting—it was challenging painting to reconsider its claim on reality.

Steichen, Stieglitz, and the Camera Work circle

In America, the leading force behind photography’s rise as a fine art was Alfred Stieglitz. By 1900, he was not yet the messianic figure of modernist promotion he would become, but he had already established himself as a key editor, theorist, and exhibitor. That year, he was preparing the launch of Camera Work, a quarterly publication that would begin in 1903 and serve as the most important photographic journal of the era. Its goal was clear: to show that photography was not a lesser art, but a new visual language in its own right.

Stieglitz’s own photographs from the period—including Winter on Fifth Avenue and The Terminal—captured urban life not as reportage, but as poetry in motion. Using hand-held cameras and atmospheric weather conditions, he depicted horse-drawn carriages dissolving into snow, steam rising from sewer grates, and faces vanishing behind umbrellas. His camera did not freeze time—it haunted it.

In 1900, Stieglitz was also beginning his collaboration with Edward Steichen, a younger, Luxembourg-born photographer and painter who brought a more European sensibility to the American scene. Steichen’s photographs from this period were among the most daring of the Pictorialist era. His 1900 portrait of Rodin at Work, shrouded in darkness and smoke, is less a likeness than a spiritual x-ray of the sculptor’s psyche. Likewise, his moody landscapes and portraits of women, printed in platinum or gum bichromate, suggested mystery rather than moment.

Stieglitz and Steichen would go on to found the Photo-Secession in 1902, but the seeds of that movement were already sprouting in 1900. They rejected commercial photography, snapshot realism, and the formulaic studio portrait. Instead, they pursued individual vision, aesthetic autonomy, and the belief that photography could do what no other medium could—distill time into tone.

They weren’t alone. Photographers like Clarence H. White in Ohio and Gertrude Käsebier in New York were advancing the cause, particularly in portraiture. Käsebier’s Blessed Art Thou Among Women (1899) was still widely exhibited in 1900 and offered a deeply spiritual maternal image without sentimentality. Her studio in New York became a haven for aspiring women photographers and a crucial link in the transatlantic network of artistic photography.

Together, this circle formed the backbone of early photographic modernism—not in content or style, but in attitude. They believed in authorship, experimentation, and photography’s full inclusion in the high arts. In 1900, that belief was still a minority view. But it was beginning to gain ground.

Photojournalism at the Exposition

If artistic photography was seeking admission into galleries and salons, documentary photography was exploding in the popular press. The 1900 Exposition Universelle was among the most photographed events in the world to date. Not only did official photographers document the construction, exhibits, and architecture of the fair, but photojournalists—a relatively new class of visual workers—captured candid scenes of visitors, workers, and the daily life of the event.

Publications like L’Illustration, Le Monde Illustré, and various international newspapers published halftone photo reproductions, made possible by advances in printing. For the first time, mass audiences could see actual images—rather than engravings—of events, people, and places from around the world.

Among the many subjects documented:

- The opulence of national pavilions, including their artwork and architectural flourishes.

- Crowds gathered around electric fountains or mechanized displays.

- Candid shots of foreign delegations, often presented with Orientalist flair.

These images were not without their manipulations. Staged scenes, selective framing, and imposed narratives often shaped how photographs were used to construct imperial ideology or celebrate Western progress. But their impact was immense. Photography had become the visual memory of the modern world, more trusted and more widely distributed than any painted canvas.

The tension between photography as art and archive—between personal expression and public record—was one that would persist for decades. But in 1900, both roles were expanding rapidly. Photographers were no longer technicians or documentarians alone. They were storytellers, interpreters, and sometimes visionaries.

Looking back, it becomes clear: the year 1900 did not just see photography’s rise in prestige. It saw the medium begin to reshape the very nature of seeing—not by replacing painting, but by challenging it to change.

Theaters of Painting: Russia, Spain, and Japan

Mikhail Vrubel and the Russian mystical strain

While France and Germany dominated the art conversation in 1900, other cultural centers were pursuing their own powerful, often overlooked artistic evolutions. In Russia, a distinct strain of Symbolist and spiritualist painting had emerged—part Orthodox icon, part Romantic fever dream, with a darkness and drama unmatched in the West. At the center of this movement stood Mikhail Vrubel, a painter so unique in style and so psychologically charged in vision that even sympathetic critics struggled to place him.

Vrubel’s defining work at the turn of the century was his “Demon” series, particularly The Demon Seated (1890) and The Demon Downcast (1902), which reflect both the metaphysical turbulence of late imperial Russia and the artist’s own growing instability. These canvases depicted a fallen angel—not as a satanic figure, but as a tragic, brooding outcast, torn between divine origin and earthly exile. His bodies were fragmented, crystalline, muscular, almost cubist before the term existed. His use of color—sharp blues, bruised purples, molten gold—felt volcanic rather than decorative.

By 1900, Vrubel was at work on mural commissions for the Church of St. Cyril in Kyiv and producing designs for the opera and ballet in Moscow. He also contributed strikingly original ceramic works, blurring the line between painting and decorative arts. His aesthetic—eccentric, symbolist, and steeped in myth—was closely aligned with the Abramtsevo Colony, a revivalist circle near Moscow dedicated to reanimating Russian folk culture and medieval art forms.

Vrubel’s spiritual intensity was not affectation. He would soon descend into mental illness, suffering hallucinations and institutionalization. But in 1900, his creative powers were still peaking. He was less a participant in the European avant-garde than a parallel phenomenon—a solitary fire burning in the vast Russian night, lighting the path toward what would soon become the Russian Silver Age.

Sorolla’s sunlit realism

In Spain, the most celebrated painter of 1900 was Joaquín Sorolla, a master of luminous impressionism and plein-air portraiture. His works dazzled critics at the Exposition Universelle, where he received a gold medal, and he was already gaining collectors in France, Britain, and the United States. Unlike Vrubel, Sorolla embraced the visible world—sun, sea, fabric, gesture—with an exuberance that was both modern and grounded in classical clarity.

His 1900 masterpiece Sad Inheritance!—a massive, compassionate canvas showing children with physical disabilities bathing under clerical supervision—won the Grand Prix in Paris. It stunned audiences not only for its technical mastery but for its moral courage. Rather than sentimentalize his subjects, Sorolla painted them with dignity and tenderness, the harsh sunlight revealing every detail of flesh and movement. It was a work both social and aesthetic—a rare combination at that scale.

Sorolla’s broader oeuvre from this period leaned toward regional genre scenes and seascapes, particularly his beloved Valencia coast. He painted boys running through surf, women in white carrying fishing nets, orange sellers and lace-makers caught in mid-task. But the brushwork was swift, loose, and informed by the light—always the light. Critics compared him to Monet and Sargent, but Sorolla’s style was entirely his own: warmer, faster, and more narrative.

While not a radical, Sorolla was not a conservative either. He navigated between the academies and the modernists, refusing to join any school or –ism. In 1900, he stood as an example of how an artist could innovate within representation, combining technical brilliance with humane observation. His popularity would only grow in the coming decade, culminating in his 1909 solo exhibition in New York, arranged by Archer Huntington and the Hispanic Society of America.

At a time when modernism often flirted with alienation or abstraction, Sorolla’s realism was an affirmation—not of the old order, but of the real, luminous world still worth painting with clarity and love.

Meiji-era echoes in Japanese nihonga

Far to the east, Japan’s artistic world in 1900 was experiencing its own kind of duality. Since the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the nation had rapidly industrialized and opened its cultural doors to the West. Japanese prints had influenced European artists for decades, but within Japan itself, the tension between tradition and innovation took on a more urgent and national character. Nowhere was this clearer than in the conflict between yōga (Western-style painting) and nihonga (Japanese-style painting).

By 1900, nihonga was not a nostalgic holdout—it was a living movement, newly codified and fiercely defended by artists who sought to preserve Japanese aesthetic values while incorporating select modern techniques. Artists like Yokoyama Taikan and Hishida Shunsō experimented with line, brushstroke, and space, reviving techniques from Kanō and Tosa schools while exploring new treatments of perspective and color.

Yokoyama’s scroll paintings and folding screens from this period employed soft gradients and atmospheric depth—often using the morotai (hazy style) method that eschewed hard outlines in favor of evanescent tonal transitions. The subject matter—landscapes, seasonal flora, poetic figures—was traditional, but the execution hinted at a subtle engagement with European painting, especially Impressionism and Symbolism.

At the 1900 Exposition Universelle, Japan presented both yōga and nihonga works in a carefully curated national display. The goal was not merely to impress, but to assert cultural identity: modern, sovereign, and uniquely Japanese. The pavilion, designed with architectural references to ancient Kyoto, showed lacquerware, woodblock prints, sculpture, and painting together as a holistic statement of aesthetic continuity.

Meanwhile, Kuroda Seiki, the leading advocate of yōga, had just returned from Paris and was promoting oil painting and academic techniques among Japanese artists. While controversial, his influence helped build institutional bridges between European realism and Japanese subject matter. The Tokyo School of Fine Arts, under his leadership, trained a new generation of painters equally fluent in East and West.

Thus in 1900, Japanese painting stood at a cultural junction—not imitating the West, but rather asserting a dual heritage, in which ink wash and oil pigment coexisted. Nihonga was not reactionary. It was modernity on its own terms: slow, refined, and fiercely aware of its national soul.

Architecture and the Total Work of Art

Hector Guimard and the Paris Métro

On the streets of Paris in 1900, one could descend into the future through a swirling canopy of iron and glass. The Métropolitain, newly opened that year to accommodate the crowds of the Exposition Universelle, was not merely a transport project. It was a visual statement, a marriage of engineering and ornament that placed design directly in the public sphere. Its author was Hector Guimard, a French architect who translated the spirit of Art Nouveau into architectural vocabulary more vividly than anyone else.

Guimard’s Métro entrances, now iconic, were unlike anything the city had seen. They featured asymmetrical cast-iron forms inspired by plants, dragonflies, and seaweed—forms that bent and bloomed rather than stood rigid. Letters melted into decoration, signs looked like petals, and handrails flowed like vines. He made no attempt to conceal the material nature of the structures. Iron, enamel, and glass were proudly displayed. But what set his work apart was its refusal to imitate historical styles. Instead of Gothic or Classical references, Guimard offered a new organic modernism, born not from precedent but from growth.

This was not architecture as monument—it was architecture as interface. He designed these public spaces with a sense of movement and permeability, anticipating how the public would touch, walk through, and encounter them daily. The Métro became not just a means of urban mobility, but a kind of civic choreography, in which design guided behavior. The entrances were made in modular components, allowing for efficient replication across the city without visual monotony—a triumph of artistic unity and practical planning.

Guimard’s vision extended beyond infrastructure. He also designed private residences, notably the Castel Béranger (1895–1898), a residential building in Paris’s 16th arrondissement that won city awards and stirred both admiration and controversy. Its façade was a riot of color, curve, and detail, covered in glazed stone, wrought iron, carved wood, and sinuous balconies. Every doorknob and cornice carried the stamp of Guimard’s hand, a testament to his pursuit of the Gesamtkunstwerk—the total work of art.

In 1900, Guimard was at the height of his powers. Though critics sometimes called his work excessive or effeminate, even they acknowledged its force. He did not just build. He composed. And in doing so, he turned the entrance to the underground into a passage to a new visual order.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh in Glasgow

Meanwhile, in Glasgow, another architect-designer was quietly building his own version of the total work of art—more rectilinear than Guimard’s, more restrained, but no less visionary. Charles Rennie Mackintosh, working in partnership with his wife Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, was crafting a distinct architectural language that combined Scottish tradition with modernist geometry and Symbolist mystery.

By 1900, Mackintosh had completed several key commissions, most notably the Glasgow School of Art, which was nearing its first phase of completion. The building, stark and asymmetrical from the outside, opened into a series of luminous, carefully proportioned interiors where every element—from the banisters to the lanterns to the furniture—reflected a coherent aesthetic sensibility. The classrooms were flooded with natural light, designed to encourage not only work but contemplation. Stone and wood were left honest, clean, and unadorned, except where ornament served function or symbolism.

Unlike the florid curves of Parisian Art Nouveau, Mackintosh favored verticals, grids, and stylized motifs, often incorporating Celtic symbols and elongated forms that hinted at the spiritual without being didactic. His high-backed chairs, thin and austere, looked more like totems than furniture. His decorative panels, painted by Margaret, were ethereal, filled with ghostly female figures, moonflowers, and abstracted forms that hovered between dream and diagram.

The Mackintoshes exhibited their work at the Vienna Secession in 1900, where they were enthusiastically received. The Austrians recognized in the Glasgow pair something kindred: a commitment to synthesis, to abstraction, and to the idea that modern design could carry metaphysical weight. Josef Hoffmann and Gustav Klimt both praised the Mackintoshes’ contribution, and their visit to Vienna marked the beginning of a fruitful cultural exchange between the Scottish and Austrian avant-garde.

In 1900, Mackintosh had few clients and many admirers. His work would remain underappreciated for decades, often misunderstood in his native Britain. But among architects and designers of the day, he represented an alternative path to modernism—one that valued interiority, rhythm, and craftsmanship over spectacle.

Otto Wagner’s rational dream

In Vienna, where the Secessionist movement was in full bloom, Otto Wagner stood as a senior figure, bridging the ornate historicism of the 19th century with the stripped-down rationalism that would soon define modern architecture. In 1900, Wagner was in the midst of his most productive period, designing public infrastructure and theorizing a new urbanism for the age of steel, glass, and electricity.

His Stadtbahn stations, built for Vienna’s metropolitan railway system and completed just before 1900, showcased his unique ability to fuse function with style. With arched iron roofs, elegant gold ornamentation, and modular platforms, the stations were both efficient and expressive—small civic temples for the modern commuter. Unlike Guimard’s vegetal exuberance, Wagner’s stations were balanced, rational, and composed, reflecting his belief that modernity need not discard beauty, but must ground it in logic and need.

Wagner’s ideas were codified in his book “Moderne Architektur”, first published in 1896 and expanded by 1900. In it, he argued that architecture must evolve from contemporary life, not from past forms. This was not a rejection of ornament, but a rejection of irrelevant ornament. A bank should not look like a Gothic cathedral; a train station should not resemble a baroque palace. Architecture, in Wagner’s vision, should reflect the material and moral truths of its age.

In 1900, Wagner’s influence extended through the Vienna School of Architecture, where he trained a new generation of designers—including Josef Hoffmann, Joseph Maria Olbrich, and later, Adolf Loos. His own projects, such as the Postsparkasse (Postal Savings Bank)—soon to begin construction—demonstrated how glass, aluminum, and stone could be combined into monumental restraint, functional and yet ceremonial.

Wagner’s modernism was not ideological. It was civic. He believed that cities should be humane, logical, and forward-looking. His work was grounded in the needs of public life—not utopia, but better order. And in 1900, as Vienna trembled with change, Wagner’s rational dream offered a clear-eyed vision of a future built not from fantasy, but from disciplined invention.

The Year’s Artistic Legacy: 1900 as Pivot, Not Peak

Not a climax, but an overture

The year 1900 was filled with ceremony. Monarchs toasted the achievements of their empires. Journalists proclaimed the triumph of industry. Architects, painters, sculptors, and designers gathered in Paris to exhibit their latest works beneath domes of glass and stone. To many at the time, it seemed the world had reached a zenith—a cultural apex built on the accumulated mastery of the 19th century and adorned with the ornament of modern invention.

But with the benefit of hindsight, it is clear that 1900 was not a culmination. It was a pivot point. The styles celebrated that year—Art Nouveau, Symbolism, academic realism, Pictorialism—were nearing their final moments as dominant modes. What came next was not refinement, but rupture.

Within five years, Fauvism would explode into the salons. Within ten, Cubism would begin to fracture visual space. Within twenty, the world would be at war, and Europe’s cultural centers would shift beneath the weight of devastation. What 1900 offered was not a vision of what the 20th century would be—but a snapshot of what was about to become obsolete.

Even the most forward-looking movements of the year—the Vienna Secession, the Photo-Secession, early modernist painting—still carried with them a reverence for unity, for symbolic meaning, for the potential of beauty to guide social order. That optimism would not survive the trenches of the First World War or the brutal logic of mechanized politics. What began in marble and gold would soon be redrawn in iron and ash.

Yet that does not diminish 1900. On the contrary, it reveals its particular virtue: the ability to stand at the threshold—half in the past, half peering into the fog of the future—with both reverence and unease.

Who was ignored in 1900—and who shaped 1901

Despite the enormous artistic activity of the year, many key figures of the 20th century were still unrecognized or unformed in 1900. Pablo Picasso had not yet reached his Blue Period. Henri Matisse was still painting like a conservative. Kandinsky, Schiele, and Malevich were names unknown outside their immediate circles. In Germany, Die Brücke had not yet formed. In Italy, Futurism had not yet declared war on the museum. The Bauhaus was decades away.