In the final year of the 19th century, the world of art vibrated with anticipation, contradiction, and unease. There was no singular movement, manifesto, or dominant school in 1899—only a gathering sense that something was ending, and something else was hesitating to begin. Artists worked under the shadow of a century’s weight, but also under its influence: the refined techniques of academic art still held prestige, while radical energies pushed against them from below. The cultural imagination was saturated with beauty and anxiety, often at once.

This duality—exquisite surfaces overlaying existential dread—marked the fin de siècle as more than a stylistic moment. It was a psychological condition. Everywhere, art was pulling in multiple directions: inward toward symbolist introspection, outward toward decorative experimentation, and downward into the unsettling regions of science and dream. A sense of inevitability pressed against the ornate facades, and many artists responded with a mixture of hedonism and prophecy.

Veils of Meaning: Barrias and the Science of Allegory

Few works more perfectly captured this moment of paradox than Louis-Ernest Barrias’s Nature Unveiling Herself Before Science, dated to circa 1899, with versions exhibited and cast between the mid-1890s and the early 1900s. The marble and onyx sculpture, held today in several major collections including the Musée d’Orsay and the Walters Art Museum, depicts a serene, partially nude woman gently drawing back a veil. She is not an individual but an allegory: the personification of Nature herself.

Barrias, trained in the traditions of the French academic style, used classical materials and proportions. Yet the sculpture is saturated with the visual logic of Art Nouveau: the sinuous lines, the emphasis on sensual surface, the mingling of organic form and idealized anatomy. Her robe, carved from delicate Algerian onyx, glows with translucent warmth; her skin emerges from mineral texture like an apparition. It is an image of revelation, but also of seduction—suggesting that what science claims to uncover, it also desires.

Biology as Aesthetic: Ernst Haeckel’s Organic Imagination

Barrias’s sculpture became widely known in artistic and intellectual circles by 1899, when reproductions and casts began appearing more frequently, and its thematic content mirrored a growing interest in the tensions between knowledge and mystery, body and spirit, empiricism and aesthetics. It was not a satire of science, nor a rejection of modernity, but a visual record of ambivalence—celebrating the unveiling of nature even as it questioned what lay beneath the veil.

If Barrias offered the sensual metaphor of nature unveiled, the German biologist Ernst Haeckel provided its visual vocabulary. In 1899, Haeckel began releasing the first fascicles of Kunstformen der Natur (Art Forms in Nature), a lavishly illustrated series that would continue until 1904. Each plate rendered with exquisite detail the forms of microscopic organisms: radiolarians, siphonophores, medusae, and diatoms. They were scientifically accurate, but their elegance astonished even those outside the biological sciences.

The Diagram Becomes Ornament

The plates of Kunstformen became an underground atlas for designers. Their influence on Art Nouveau ornamentation was immediate and widespread. The spirals of ammonites, the fronds of algae, the symmetry of radiolarians—these appeared not only in academic settings but in the motifs of architectural ironwork, textile patterns, glasswork, and book illustration. The natural world, viewed through the lens of scientific observation, had become a wellspring of form and rhythm.

Even more striking was how these organisms, often invisible to the naked eye, resonated with the fin-de-siècle fascination with transformation and instability. Haeckel’s creatures, suspended in their translucent environments, seemed to float free of gravity and scale. They echoed the era’s interest in spiritualism, dream states, and subconscious processes—offering an aesthetic of dissolution rather than structure.

Three qualities of this emerging visual culture made it distinct:

- A preference for asymmetrical, flowing lines over classical balance and proportion.

- An elevation of decorative and applied arts to the level of fine art.

- A synthesis of the scientific and the mystical, often within a single image.

Symbols, Shadows, and the End of Certainty

This convergence can be seen not only in the visual arts but in broader intellectual movements—from Theosophy and symbolism to the proto-psychoanalytic writings of Freud and the dark utopias of fin-de-siècle literature.

As 1899 unfolded, Symbolist painting reached its most ethereal and introspective phase. Across Belgium, France, and central Europe, painters and illustrators continued to reject naturalism in favor of ambiguity. The human figure became stylized, often androgynous or mask-like; landscapes melted into vaporous settings devoid of horizon. Time and space dissolved. Artists like Fernand Khnopff and Odilon Redon conjured silent rooms, staring eyes, and ghostly silhouettes. The visual world was no longer descriptive—it was suggestive.

Between Mystery and Modernity

Symbolism in 1899 was no longer merely an avant-garde rebellion against realism; it had become its own tradition, with salons, reviews, and critical treatises. But rather than consolidating, the movement fractured. In some cases, it became decorative and escapist; in others, mystical and abstract. Redon, working in charcoal and pastel, produced floating heads, radiant flowers, and mythic beasts, but he no longer explained them. His pictures did not narrate—they evoked.

This tension is echoed in the Symbolist salons of the time, where allegory, eroticism, and dream logic cohabited uneasily. The artists’ rejection of materialism and rationalism came at a moment when industrial power, colonial expansion, and technological progress seemed irresistible. In that context, Symbolism functioned not merely as an aesthetic choice, but as a refusal.

1899 as a Threshold

A refusal, yes—but also a search. Even the most decadent images of the time bear traces of longing: for permanence, for beauty, for the soul’s survival. That is what separates the fin de siècle from simple nostalgia or pessimism. Its best works—whether a sculpted veil, a biologic diagram, or a charcoal cloud—are haunted not only by what is passing away, but by what might still be possible.

The art of 1899 does not belong neatly to the 19th century, nor does it yet fully speak the language of the 20th. Instead, it stands in a space of tension—rich, unsettled, and revelatory. Forms swirl and fade; surfaces shimmer; meanings retreat behind veils. It is a moment not of resolution, but of exquisite instability.

At the century’s hinge, artists looked both inward and outward. Their works reflect a world already drifting into the dreamlike atmosphere that modernism would later shatter or sublimate. The veil had been lifted—but what stood behind it was not clarity, but a deepening mystery.

Chapter 2: Vienna in Bloom

A City Suspended Between Ornament and Upheaval

In 1899, Vienna was not merely a city; it was an aesthetic engine running on contradictory fuel—conservatism and rebellion, opulence and anxiety, ceremony and rupture. Now the capital of a vast and creaking Austro-Hungarian empire, it was also becoming the capital of an artistic revolution. The center of this upheaval was the Vienna Secession, a group of artists and architects who had broken away from the rigid conventions of the imperial Academy of Fine Arts. Their motto, inscribed above their new building’s entrance, was both elegant and radical: To every age its art, to art its freedom.

The year marked a turning point. The Secession was no longer a tentative experiment. In 1899, it became a platform of serious cultural ambition, and its exhibitions took on a gravitational pull that reshaped the artistic life of the empire. With Gustav Klimt rising to new heights, Koloman Moser redefining design, and an increasingly international curatorial vision, Vienna’s fin-de-siècle bloom reached full flower—just as its political and psychological ground began to shift.

Klimt’s Schubert at the Piano and the Cult of the Interior

In 1899, Gustav Klimt completed Schubert at the Piano, a large and lavish painting that marked a pivotal stage in his transformation from accomplished academic painter to the leading figure of the Viennese avant-garde. The work, now lost and known only through black-and-white photographs, depicts the Romantic composer Franz Schubert seated at a piano, surrounded by an attentive, dreamlike circle of women. They do not so much listen as absorb—silent, spectral, almost icon-like in their stillness.

Though the subject is ostensibly musical, the real focus is mood: this is a painting about absorption, reverie, and emotional containment. Klimt dissolves architectural structure into ornamental shadow; the background becomes a field of pattern and suggestion. It is an early gesture toward the decorative-symbolist mode that would define his mature work, especially Philosophy (1900) and The Beethoven Frieze (1902). Here in 1899, the transformation is in motion.

What is notable is the way Klimt turns Schubert into a conduit for something larger than music—something like cultural inheritance or collective yearning. By placing him in a quasi-domestic, feminized space, Klimt blurs the line between historical commemoration and spiritual séance. In a city obsessed with memory, Schubert at the Piano turns the past into ornament and reverie—an emblem of the Secession’s search for meaning beyond monumentality.

The Fourth Secession Exhibition: Expanding the Frame

The Vienna Secession held its fourth exhibition in March 1899, and by now, the group had outgrown its early uncertainty. The show featured work not only by Austrian members but by invited artists from Germany, Belgium, and Britain, signaling a more expansive European outlook. The staging was striking: rooms were arranged with unity of design, eschewing traditional salon hang for a more holistic presentation—one that included wall treatments, decorative panels, and furniture as part of the visual experience.

This approach, sometimes called the “Gesamtkunstwerk” or “total work of art,” was central to the Secessionist ethos. Art was not to be contained in frames; it was to shape the environment. In the 1899 exhibition, decorative works by Koloman Moser and others mingled with paintings and sculpture. The effect was immersive, designed to envelop the viewer in a visual atmosphere rather than a chronological or thematic survey.

Three elements set this exhibition apart:

- A rejection of academic naturalism in favor of symbolic, mythic, or dreamlike subject matter.

- A blending of applied and fine arts, with furniture and poster design granted equal footing.

- A meticulous concern with spatial experience—how the work was seen, not just what it depicted.

The press reaction was mixed. Conservative critics balked at the abstraction and stylization. But for younger artists and progressive patrons, the Secession offered a glimpse of what modern art could become: not merely expressive, but environmental; not merely individual, but cultural.

Koloman Moser and the Elegance of Utility

Among the most distinctive voices at the 1899 exhibition was Koloman Moser, whose designs for furniture, glass, wallpaper, and printed matter crystallized the visual language of the Viennese avant-garde. One of his best-known contributions from that year was a poster for the “five-art” exhibition of the Secession, a bold black-and-white composition with classical figures and sharp vertical rhythms. Moser’s graphic clarity and sense of rhythm stood in contrast to the floral excesses of Art Nouveau elsewhere in Europe. He cultivated restraint, not indulgence.

Moser and his colleagues were pushing toward a new synthesis: an art that was not merely aesthetic but functional, not merely elite but accessible. His work presaged the formation of the Wiener Werkstätte in 1903, but the seeds were clearly present in 1899. Even in his earliest designs, utility and elegance are inseparable. He did not wish to decorate life—he wanted to redesign it.

Fractures Beneath the Surface

For all the harmony on the walls of the Secession building, fractures were developing beneath them. Some members began to question the group’s increasingly decorative tendencies. Others saw the Secession becoming a closed circle, less a rebellion than a new orthodoxy. These tensions would later result in schisms, with figures like Josef Hoffmann and Moser breaking away to pursue design reform more independently.

But in 1899, the movement still held. It had momentum, cohesion, and an urban audience hungry for new forms of visual pleasure and cultural depth. Vienna, for a brief moment, became a city where art was no longer merely displayed—it was lived.

A Moment That Couldn’t Last

Looking back, 1899 was the moment just before the mask cracked. The empire still stood, the salons were still full, and Klimt’s gold leaf had not yet been applied. But the psychological unease that would define Vienna’s early modernism—its Freudian introspection, its architectural anxieties, its aesthetic crises—was already pressing against the surface.

The city bloomed in ornament and ceremony, but it was the bloom of late summer, lush and faintly overripe. In the Secession, beauty was reimagined as interior truth; in Klimt, reverie replaced history; in Moser, line and function became the new luxury. And behind it all, the knowledge that the century was not just ending—it was preparing to explode.

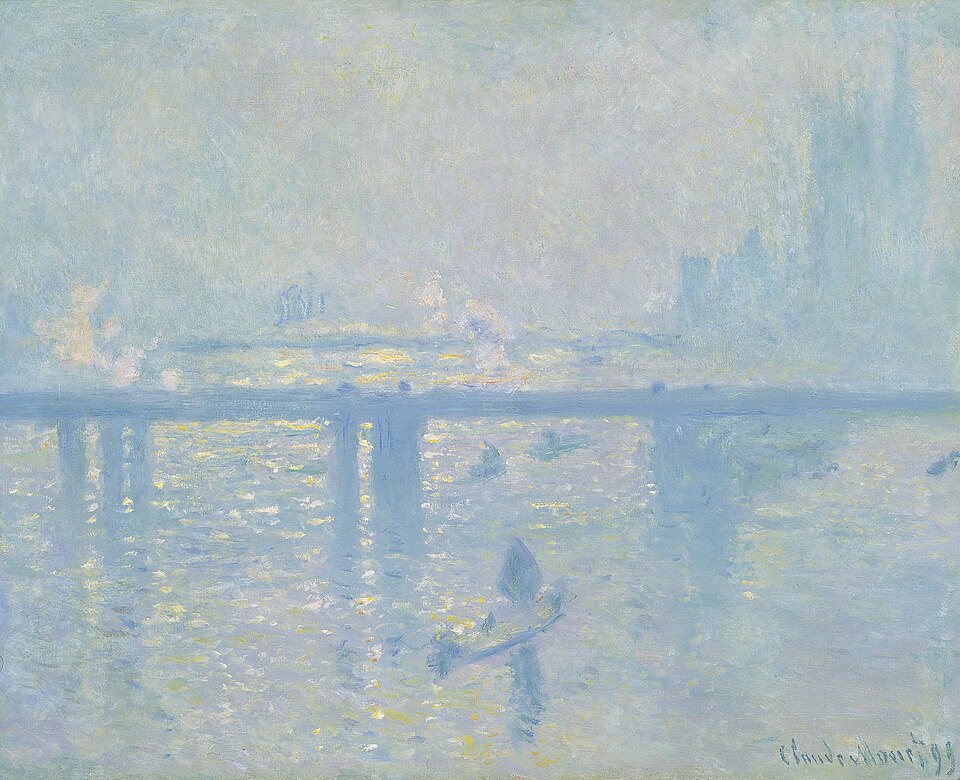

Chapter 3: Parisian Reverberations

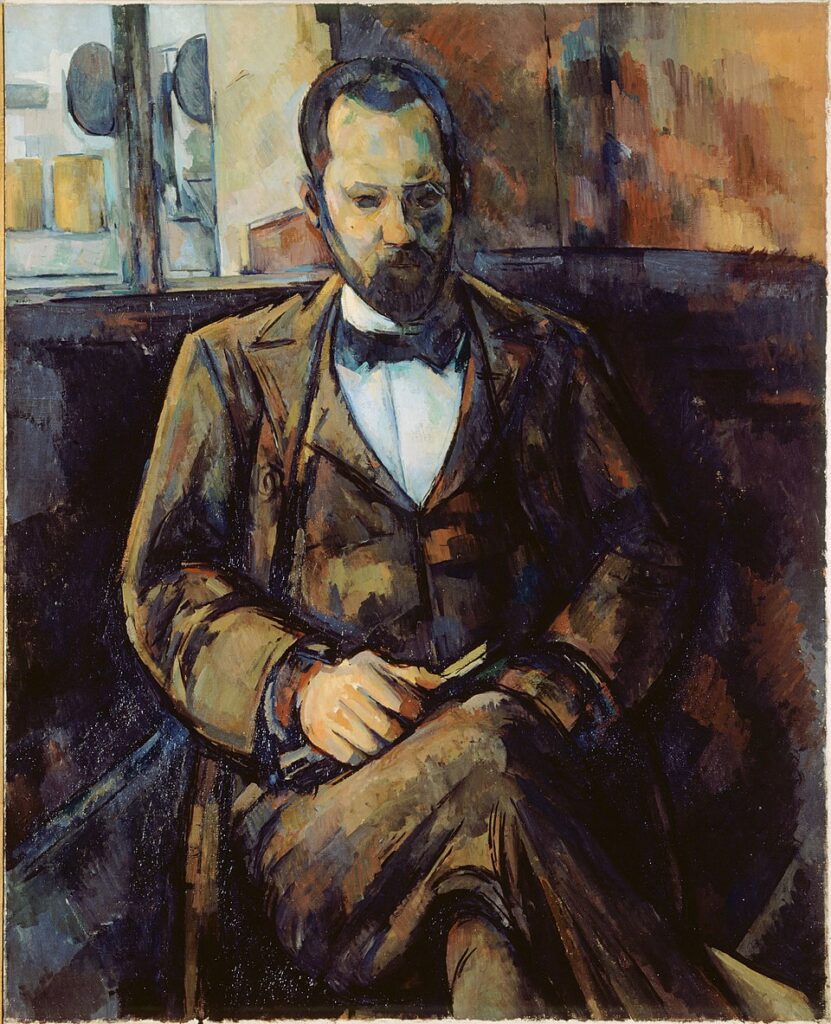

Bonnard, Vuillard, and the Nabis Retreat Inward

In 1899, the grand salons of Paris still echoed with the legacy of Impressionism, but on the quiet edges of the city’s cultural life, a different kind of painting was taking root. It was smaller, more domestic, more secretive. Gone were the sweeping boulevards and bright gardens of the 1870s and 1880s. In their place came lamplit parlors, printed wallpaper, quiet women in patterned robes. This was the world of the Nabis—a loose group of painters including Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, Maurice Denis, and Félix Vallotton—who by the close of the century had turned their gaze away from public spectacle and toward the rituals of daily life.

Their name, “Nabis,” derived from the Hebrew word for prophet, once carried the weight of ambition. In the early 1890s, these painters aimed to revitalize art with spiritual symbolism, cloaked in simplified forms and decorative structure. By 1899, that spiritual fervor had cooled, but the aesthetic innovations remained. The Nabis were no longer visionaries in the mystical sense; they had become chroniclers of interior experience.

Vuillard’s Cloistered Vision

In 1899, Édouard Vuillard produced some of his most enveloping interior scenes—modest in scale but rich in pattern, texture, and psychological density. These were not grand declarations of modernity. They were paintings of mothers sewing, women writing letters, or solitary figures absorbed in thought, often set within claustrophobic apartments or bourgeois sitting rooms.

One striking example is La table de toilette (The Dressing Table), painted in 1899 and now in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay. It shows a woman in profile, half-obscured by the soft chaos of furniture, textiles, and wallpaper. There is no narrative, no gesture of action—just stillness, intimacy, and the eerie equilibrium of closed space. Vuillard renders the room not as architecture but as a cocoon. His surfaces vibrate with tactile echoes: the pattern of a carpet echoes the folds of a skirt, which blend into the background’s faded floral wallpaper. There is almost no distinction between figure and setting. The self dissolves into its environment.

This is not Impressionism—it is its opposite. Where Monet chased light across rivers and cathedrals, Vuillard stayed indoors and painted air that barely moved.

Bonnard and the Intimacy of the Unspoken

Pierre Bonnard, too, was turning inward in 1899. His work that year often hovered at the threshold between painting and memory. In Femme à sa toilette (1899, private collection), he paints his longtime partner Marthe de Méligny as she dresses, captured not in realism but in memory’s hue: soft oranges, vaporous violets, shimmering flesh. The perspective is compressed; the outlines fluctuate. Nothing in the picture insists on itself. Bonnard invites you to linger, to notice, and then to forget.

Though he was a keen observer of domestic life, Bonnard resisted sentimentality. His interiors are tender but disquieting. Even when his subjects are bathed in color, there’s a strange solitude to them—figures caught in routine, seen but unreachable.

Three tendencies unify the Nabis’ 1899 work:

- A rejection of grand subject matter in favor of the minor, marginal, and routine.

- A flattening of pictorial space, influenced by Japanese prints and stained-glass structure.

- A preference for muted psychological tone—neither dramatic nor detached, but quietly charged.

Symbolism’s Fading Light

Meanwhile, other corners of the Parisian art world still bore the imprint of Symbolism, though by 1899, its energies were beginning to fray. Gustave Moreau had died the year before. Odilon Redon remained active, his pastel works moving toward luminous, floral abstraction, though less haunted than in his earlier charcoal noirs. The Symbolist impulse, once radical, was beginning to be absorbed by commercial illustration, fashion, and the decorative arts. Its last convulsions, though still potent, were no longer central.

Yet that fading was itself expressive. Paris in 1899 was a city unsure of its cultural destiny. The Impressionists were dead or aging. The avant-garde had splintered. Art Nouveau filled the streets and galleries with its elegant tendrils, but it often felt more like a style of presentation than a challenge to content. The most original work of the year wasn’t bombastic. It was modest, private, and formally subtle.

The Sound of a Movement Withdrawing

The Nabis would soon disband. Denis turned increasingly toward religious mural painting. Vallotton moved into biting satire and woodcuts. Bonnard and Vuillard, the two most poetic of the group, retreated into their own personal mythologies—each constructing a kind of visual diary that spanned the next three decades.

In 1899, though, there was still a shared ethos. These artists believed that everyday life—its textures, its repetitions, its silences—could be a legitimate subject for painting. They did not seek to change the world. They sought to describe, with infinite delicacy, how the world felt from inside a room.

It was a minor revolution, and all the more enduring for that.

Chapter 4: The Death of Rosa Bonheur

A Funeral for a Fame Already Fading

When Rosa Bonheur died on May 25, 1899, at her château near Fontainebleau, the obituaries were swift and respectful. In France and abroad, she was praised as one of the most successful and accomplished painters of her time. The London Times called her “the most celebrated woman artist of the century.” The New York Times described her as “peerless in her field.” Yet behind these tributes was an unmistakable tone of finality. It was as if Bonheur had already receded into the past, her achievements embalmed rather than sustained. The funeral was not a passing of the torch. It was the sealing of a tomb.

This premature burial of her reputation was not entirely a surprise. In the last decade of her life, Bonheur had increasingly withdrawn from the Parisian art scene, rarely exhibiting, rarely traveling, and refusing to adapt to the changing tastes of fin-de-siècle aesthetics. Once the embodiment of mid-century artistic triumph, she had become a monument out of step with the moment.

The silence that followed her death was not personal—it was cultural. By 1899, the very qualities that had made her a phenomenon in the 1850s and 1860s had come to seem outdated, even unfashionable. Bonheur had painted with rigorous realism, moral clarity, and technical brilliance. But in an age leaning toward Symbolism, Art Nouveau, and psychological interiority, her vivid animal portraits and pastoral scenes began to feel like echoes from a vanished order.

The Cult of Technique: Bonheur’s Mastery

In her prime, Rosa Bonheur had been a sensation. Her 1853 painting The Horse Fair—a monumental panorama of Percherons and dealers in the Parisian horse market—was hailed as a masterpiece in both France and Britain. It toured widely, drew crowds in New York, and was eventually purchased by Cornelius Vanderbilt, who donated it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it still hangs today.

Bonheur’s technical precision was astonishing. She spent days in slaughterhouses dissecting animal musculature. She wore trousers—then illegal for women without a police permit—so she could move more freely through muddy livestock fields. Her canvases were feats of anatomical knowledge and painterly control. Critics, even those skeptical of women artists, grudgingly admitted her superiority in this genre. She wasn’t a “great woman painter”; she was, in their words, simply “a great painter.”

But her greatness was tethered to a world of visual authority and representational transparency. Bonheur believed in painting what she saw, and she believed the artist’s job was to master, not subvert, reality. There was no irony, no ambiguity in her work. The horse reared. The cow grazed. The mountain rose behind the tree line. It was an art of presence, not of atmosphere.

By 1899, this clarity had come to seem too clear.

Gender, Genre, and the Erasure of Authority

Bonheur’s career had always been a challenge to social norms. She lived with women, rejected marriage, dressed in men’s clothes, and operated with fierce independence. She was awarded the Légion d’honneur by Empress Eugénie in 1865—the first woman to receive the honor for artistic achievement. Her studio, Château de By, became a near-mythic retreat: equal parts fortress, salon, and sanctuary.

And yet her posthumous eclipse reveals the limits of recognition for women artists at the end of the 19th century. In life, Bonheur was admired for her exceptionality. In death, that exception became isolation. Unlike her male contemporaries, whose reputations evolved through critical reappraisal and institutional canonization, Bonheur’s fame stalled. She had no school, no clear stylistic descendants, no place in the emerging narratives of modernism.

Three interlocking reasons account for her rapid disappearance:

- Genre hierarchy: Animal painting, long considered a “lesser” category, lacked the symbolic or historical prestige favored by the academy and avant-garde alike.

- Gendered framing: Her life was celebrated, but her work was often discussed as a novelty—emphasizing her eccentricity over her artistry.

- Aesthetic shift: The late 19th century favored ambiguity, introspection, and abstraction—qualities at odds with her empirical, outward-facing realism.

The Salon Era’s Final Curtain

Bonheur’s death in 1899 was more than a personal loss. It marked the end of an era. She had emerged from the world of the Paris Salon, with its juried exhibitions, grand prizes, and rigid genre structures. That world had already begun to decay. The Secession movements in Vienna, Munich, and Berlin were challenging academic authority. The Impressionists had shown that rejection could be a strategy. The Nabis had collapsed the border between fine and decorative art. Auguste Rodin was turning public sculpture into psychological drama.

Bonheur had no interest in these upheavals. She remained committed to an older vision of the artist as craftsperson, observer, and moral guide. And in some ways, she was right to resist. There was—and remains—extraordinary value in the vision she sustained: a clarity of form, an ethical seriousness, a refusal to bend to fashion.

But in the culture of 1899, she was no longer at the center. The center had moved.

The Afterlife of a Forgotten Master

Today, Rosa Bonheur’s name is returning to scholarly and curatorial conversations, but in 1899, her legacy was already retreating. The museums that had once prized her work relegated it to side halls. Her reputation was remembered fondly, but not forcefully. In a century defined by rupture and reinvention, she became a symbol not of continuity but of distance.

Yet there is something strangely fitting about her exit. Bonheur, so often defiant of convention, refused even to die on cultural cue. She left at the exact moment when the 19th century itself was preparing to vanish. The century she had helped to define had no room left for her. But it also had no one who could quite take her place.

Chapter 5: Toulouse-Lautrec in Decline

The Painter of Paris Sinks Into the Margins

In 1899, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was 35 years old, and already dying by degrees. The brilliance of his earlier decade—the posters, the cabaret scenes, the bold lithographs that had made him the definitive visual chronicler of Montmartre—was fading under the pressure of physical deterioration, alcoholism, and psychological collapse. He had lived fast, painted faster, and by 1899, the machinery was breaking down. That spring, his family committed him to a private clinic in Neuilly-sur-Seine, where he would undergo enforced rest and treatment for syphilis and chronic alcoholism.

The confinement might have saved his life, at least temporarily. It also produced some of the most haunting and lucid work of his final years. In a cruel twist of fate, Toulouse-Lautrec’s decline brought with it a late surge of clarity: an art no longer intoxicated by spectacle, but sober in its observation of human isolation, vulnerability, and performance. The man who had once reveled in the nocturnal theatre of Paris now painted its backstage sorrow with exquisite restraint.

Drawing in Confinement: The Clinic Sketches

During his three-month stay in the Neuilly clinic from February to May 1899, Toulouse-Lautrec was allowed to draw. He filled the time obsessively with sketchbooks, producing a suite of circus scenes and character studies from memory. These drawings, now scattered across several collections, are unlike his earlier flamboyant posters. The line is sharp but unhurried; the figures are more fragile than ironic. He returned to themes that had obsessed him: acrobats, clowns, dancers, prostitutes, and drunks—those who, like himself, lived between spectacle and collapse.

Among the most remarkable of these is a drawing of the equestrienne Charmion performing a trick ride. The composition is spare: just a single horse, a taut female figure, and the exaggerated tilt of the circus ring. But the perspective is disoriented, the atmosphere charged with quiet unease. There’s no audience, no applause—only the performer and the effort to maintain poise. It is Toulouse-Lautrec’s situation exactly.

The drawings were so vivid that his doctors deemed him mentally competent and released him. But the judgment, though optimistic, was not prophetic. Within weeks, he was drinking again.

The End of the Dance-Hall Painter

In the months following his release, Toulouse-Lautrec resumed painting and occasional travel, but his health and stability were clearly failing. He began a final series of lithographs and oils in 1899 that now read as elegies to a world he had once dominated. Examination at the Brothel (1899), for instance, depicts the grim medical inspection of sex workers—a bureaucratic humiliation rendered with quiet, documentary stillness. The tone is observational but tender. Gone is the voyeuristic thrill of the earlier Salon de la Rue des Moulins. In its place: fatigue, resignation, and empathy.

Another late painting, Portrait of Madame la Comtesse Adèle de Toulouse-Lautrec (1899), his mother, shows her seated in black, back stiff, gaze withdrawn. It is a painful image. The woman who had devoted her life to protecting and promoting him now looked like a mourner awaiting a death not yet announced. The portrait feels both dutiful and unsentimental. There is no idealization. Only waiting.

Three defining characteristics emerge from his 1899 output:

- A stripped-down palette, increasingly monochrome and muted.

- Compositions that isolate figures in compressed, almost airless spaces.

- A growing attention to repetition and routine rather than entertainment or novelty.

A Life Played Out in Public

Toulouse-Lautrec had always been both subject and observer. His own body—stunted, twisted by a congenital disorder, and treated with contempt by the polite society he rejected—was inseparable from his art. He knew the underside of Paris not as a tourist, but as a participant. He lived in the brothels he painted. He drank with the performers he sketched. He was not illustrating decadence—he was drowning in it.

In 1899, the bohemianism that had once made him a cult figure now seemed like a curse. Montmartre was changing. The Moulin Rouge no longer shocked. The avant-garde had moved on. The poster craze he had helped ignite was already waning. Toulouse-Lautrec was no longer ahead of his time. He was behind, and visibly unraveling.

Yet even in decline, he saw more clearly than most. His art had always contained a double edge—satire and sympathy. By 1899, the satire was gone, but the sympathy had deepened. He painted those on the margins not as grotesques or symbols, but as fellow strugglers. His brush had slowed, but it had not failed.

What Remained

By the end of 1899, Toulouse-Lautrec was living under his mother’s care at Malromé, painting sporadically and speaking of Paris with a mixture of longing and dread. He had fewer commissions, fewer allies. His drinking worsened. Yet even then, in physical collapse, he remained lucid about what mattered. “I have tried to do what is true and not ideal,” he once said. That commitment, more than any stylistic novelty, is what gives his late work its extraordinary gravity.

He would die two years later, in 1901. But in 1899, the final chapter had already begun. And though the world around him looked away, the artist saw more clearly than ever. Not the glamour, but the exhaustion behind it. Not the dancer, but her blistered feet.

Chapter 6: Whistler’s American Echoes

A Reluctant Return Across the Atlantic

By 1899, James Abbott McNeill Whistler was entering the last act of a long and combative career. He was living in London, estranged from many of his former allies, increasingly frail after the death of his wife Beatrix in 1896, and more concerned with legacy than provocation. Yet even as his physical energy waned, Whistler’s influence was cresting—especially in the country of his birth. After decades of self-imposed European exile, the American art world had come back into his orbit, eager to claim him as one of their own.

It was a strange reversal. Whistler had long distanced himself from American artistic provincialism, once declaring that he had “nothing in common” with his homeland’s tastes. But by 1899, museums and collectors in Boston, Philadelphia, and New York were seeking out his etchings and tonal portraits with growing reverence. Aestheticism—once ridiculed in American circles as effete or elitist—was becoming the language of a new cultural class, and Whistler’s moody harmonies and self-fashioned mystique fit the moment precisely.

His return to American attention in 1899 was not a physical homecoming—he never visited again—but an ideological one. The man who had once infuriated critics on both sides of the Atlantic was now being absorbed into the canon. But absorption was not affection. Whistler was admired, but still misunderstood.

Portraits in Grey and Gold

In 1899, Whistler completed several late portraits, including Miss Rosalind Birnie Philip—his sister-in-law and, by then, his studio assistant and chief archivist. Painted in soft, nearly monochrome hues, the portrait continues his long preoccupation with harmony and restraint. It is neither dramatic nor psychologically probing. Instead, it offers a studied, almost musical elegance: the pose understated, the palette reduced to silvers and blacks, the figure balanced like a note in a silent chord.

What Whistler sought in portraiture was not likeness, but atmosphere. He titled his paintings like musical compositions—Symphony in White, Arrangement in Grey and Black—emphasizing form over narrative. In Miss Philip’s portrait, as in his earlier masterworks, the sitter becomes less a subject than a component in an overall aesthetic structure.

American collectors in 1899 were finally coming around to this idea. The Gilded Age had matured. Its nouveaux riches, once hungry for European Old Masters, now turned to Whistler as a bridge between taste and modernity. His work, once dismissed as mannered or empty, began appearing in serious exhibitions, acquired by figures like Charles Freer, who would go on to found the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., with Whistler as its centerpiece.

Aestheticism Takes Root

Whistler’s broader aesthetic theories were also gaining traction in American art schools and journals. His 1890 book The Gentle Art of Making Enemies, a combative and aphoristic volume of letters, lectures, and courtroom jousts, had been dismissed at first as theatrical. But by 1899, its ideas had filtered into teaching studios and critical debates. The notion that art should be independent of moral or didactic purpose—that beauty could be its own justification—was now being seriously entertained by younger artists.

In cities like Philadelphia and Chicago, Whistler’s etchings were being studied alongside those of Rembrandt and Meryon. His influence could be seen in the tonal realism of Thomas Dewing and the muted harmonies of Abbott Handerson Thayer. Even John Singer Sargent, who had once taken a more robust, cosmopolitan approach to portraiture, began experimenting with looser, more atmospheric effects.

Three currents flowed from Whistler’s influence in 1899:

- A shift in portraiture from heroic depiction to tonal impression and compositional balance.

- A new prestige for etching and lithography as autonomous, expressive media rather than reproductive tools.

- A growing acceptance of aestheticism as a serious artistic philosophy rather than a social eccentricity.

Fighting for Posterity

Yet Whistler was not basking in triumph. He remained bitter, guarded, and embattled. The death of his wife had deepened his isolation. His health was deteriorating—he suffered from chronic illness and fatigue—and his circle of intimates had grown small. In 1898, he had closed his cherished Chelsea studio, the “White House,” and moved to a smaller flat in Fitzroy Street.

In 1899, much of his energy was devoted to organizing and editing his legacy. He worked closely with Rosalind Philip to archive correspondence, catalog works, and manage reproductions. He was deeply suspicious of misinterpretation. Every brushstroke, every title, every placement in an exhibition mattered. His aesthetic vision was total, and even at the edge of collapse, he guarded it with ferocity.

There were exhibitions of his work in London and Paris in 1899, and tentative interest from American institutions in organizing a retrospective. Whistler responded with a mixture of scorn and exactitude, issuing instructions, correcting catalogues, and fighting over attributions.

Distance, Control, and the Myth of the Artist

Whistler’s American echo in 1899 was both triumph and irony. He had spent decades cultivating an identity apart from nation and tradition: the cosmopolitan dandy, the artist as sovereign. Now, his native country sought to recover him, to convert the provocateur into a monument.

But Whistler could not be easily reclaimed. His work resisted narrative. His portraits concealed more than they revealed. His writings bristled with wit but refused coherence. Even in his final years, he remained a figure of productive contradiction: a man of absolute control who courted chaos; an American who became definitively European; a realist who dissolved form into haze.

In 1899, as Europe’s avant-garde fractured into Expressionism, Symbolism, and Secession, Whistler seemed already from another time—and, in some ways, from a future that hadn’t arrived. His insistence on form, abstraction, and beauty as values unto themselves would soon be echoed by modernists who never knew him. But in that year, his legacy was still a question mark. Celebrated, yes. But not yet understood.

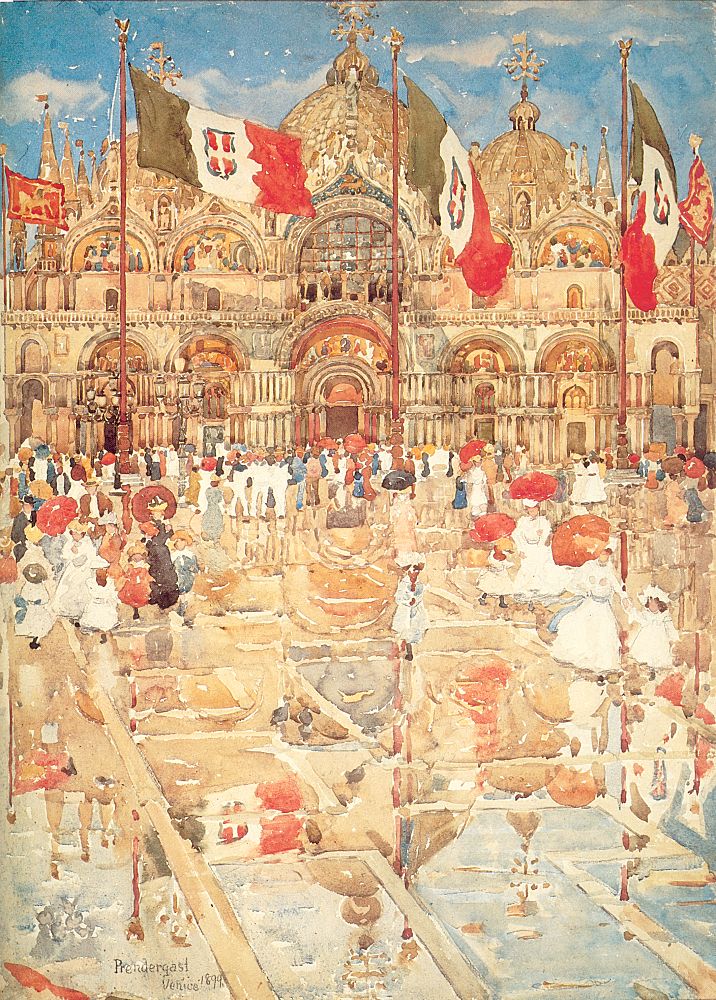

Chapter 7: Imperial Aesthetics in Japan and Britain

Two Empires, One Exhibitionary Obsession

In 1899, the British Empire and the Empire of Japan—one in the full flush of global dominance, the other freshly emerged from centuries of enforced isolation—were both deepening their engagement with the visual arts. But they did so under very different pressures. Britain’s artistic culture was embroiled in debates over mass production, national taste, and the unfinished mission of the Arts and Crafts movement. Japan, by contrast, was engaged in a bold project of modern state-building that treated the visual arts as both diplomatic tool and ideological stage. What united them was a growing belief that national prestige could, and should, be embodied in objects.

That year marked key developments on both sides: in London, the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society held one of its most ambitious displays to date; in Tokyo, the newly formed Ministry of Education codified fine arts as a central pillar of national identity. Across both empires, beauty was becoming a form of soft power—and the exhibition hall, a political theatre.

The Arts and Crafts Dilemma

The British Arts and Crafts movement, now over a decade old, entered 1899 with confidence and confusion in equal measure. The ideals of William Morris—handcraftsmanship, local labor, ethical design—had inspired a generation of artists, architects, and reformers. But the movement faced a paradox: its aesthetic success had outpaced its social agenda. The handmade furniture, textiles, and printed books it championed were now prized by the upper middle class, precisely those consumers it had once hoped to reform.

The Arts and Crafts Exhibition of 1899, held at the New Gallery in Regent Street, brought this tension to the surface. On display were works by leading figures like C.F.A. Voysey, Walter Crane, and Ernest Gimson: furniture with clean geometry, textiles rich in vegetal pattern, and illustrations infused with medievalist charm. The craftsmanship was superb. The design language, coherent. But the prices were high. The moral argument—the idea that good design could elevate working life and restore dignity to labor—was losing ground to market success.

Three contradictions defined the British situation in 1899:

- Aesthetic ideals rooted in socialism, yet realized through elite consumption.

- A critique of industrial capitalism, yet a dependence on the gallery and department store.

- A call for national renewal, yet a retreat into medieval nostalgia.

What had begun as a radical design philosophy was becoming a style—refined, beautiful, and safe. Even figures like Walter Crane, once overtly political, now found their allegorical paintings more welcome in drawing rooms than in agitational pamphlets.

Japan’s Official Turn to Fine Art

Half a world away, Japan’s relationship with visual art was moving in a sharply different direction. Having undergone the Meiji Restoration just three decades earlier, the country was aggressively modernizing. But modernization, in Japan’s case, did not mean Westernization wholesale. Instead, it meant strategic synthesis. In 1899, the Japanese government institutionalized the fine arts with unprecedented formality: it placed painting and sculpture under the purview of the Ministry of Education, designated specific genres for state sponsorship, and encouraged the export of traditional crafts as diplomatic instruments.

This was not a grassroots movement—it was statecraft. Japan’s participation in international expositions in the 1880s and 1890s had revealed the soft power of lacquerware, porcelain, and silk. The West adored “Japanese taste,” but rarely grasped its internal complexity. The government, recognizing this, began shaping export aesthetics to fit Western expectations. Satsuma ceramics became more ornamental. Kachō-ga (bird-and-flower painting) was promoted abroad. Ukiyo-e declined at home, even as it enchanted Paris.

By 1899, a dual-track art system had emerged in Japan:

- Nihonga (“Japanese-style painting”)—rooted in traditional techniques, supported by the state.

- Yōga (“Western-style painting”)—based on oil painting, perspective, and academic realism, taught in state schools.

Rather than choose between them, Japan cultivated both, assigning them to different functions. Nihonga expressed cultural continuity. Yōga demonstrated modern competence. Both served the national image.

Aesthetic Diplomacy and Colonial Blindness

Exhibitions were the crucible where these two imperial aesthetics were tested and compared. In London, Japanese art was shown as exotic inspiration. In Tokyo, British design reform was studied as a technical model. Yet neither side fully understood the internal tensions of the other. British admirers of Japanese design rarely grasped its political orchestration. Japanese artists who emulated Arts and Crafts forms often did so with little awareness of their ideological roots in guild socialism or Morrisian utopia.

The mutual admiration masked profound structural differences. Britain’s design reform struggled against its own class system and industrial logic. Japan’s state-driven aesthetics operated within a nationalist project that would soon become expansionist. The objects glowed with harmony; the forces behind them were far from benign.

Even so, 1899 offered moments of startling cross-cultural resonance. Japanese designers adapted Morrisian botanical motifs to kimono silks. British potters studied raku ware. Architects in both countries experimented with asymmetry, craftsmanship, and unity of detail. These exchanges did not produce stylistic fusion—but they did generate new models of what art could be: not only expression, but identity; not only ornament, but ideology.

Beauty as a Tool of Power

By the close of 1899, both empires had developed a confident, exportable aesthetic. In Britain, it was the restrained, moralized elegance of Arts and Crafts. In Japan, it was the disciplined revival of classical techniques, recalibrated for international eyes. Neither aesthetic was innocent. Both were charged with the weight of national aspiration, political anxiety, and imperial ambition.

In this context, art became more than an object. It became a demonstration. A claim. A flag. The result was often beautiful—but the beauty, like the empires behind it, was double-edged.

Chapter 8: Rodin at the Summit

The Sculptor Faces the Crowd—and Its Contempt

By 1899, Auguste Rodin stood atop the French artistic world—but not without resistance beneath his feet. For two decades, he had redefined sculpture: rejecting the neoclassical smoothness of academic convention in favor of muscular, torqued, often unfinished forms that seemed to breathe with emotion. His name was known throughout Europe. His studio was busy with commissions, assistants, and controversies. But the year brought a crisis—and a revelation.

That crisis came in the form of a long-delayed monument: his bronze statue of the novelist Honoré de Balzac. Commissioned in 1891 by the Société des Gens de Lettres, it was meant to be a grand tribute to the literary titan. Rodin, however, spent seven years searching for a form that could do justice not to the man’s likeness, but to his psychic weight. What he unveiled in 1898—and what continued to dominate debate in 1899—was not a statue in the traditional sense. It was a colossus in a robe: head tilted back, body swallowed by drapery, facial features pushed to the brink of caricature. It was strange. It was grotesque. It was, unmistakably, alive.

The backlash was instant.

Balzac the Monument, Balzac the Monster

Rodin’s Monument to Balzac, exhibited at the 1898 Salon and continuing to spark debate through 1899, was not what the literary committee had imagined. They had wanted dignity. He gave them density. They wanted realism. He gave them presence. The Société rejected the sculpture outright. Rodin, humiliated but defiant, refused to alter it. He withdrew the piece and declared it a personal work.

In the meantime, the public was scandalized. Critics called it a “mummified baboon,” a “sack of flour,” an “insult to French genius.” Others praised its vigor, its honesty, its psychological force. The divide was stark. To traditionalists, Rodin had failed to respect the solemnity of public commemoration. To modernists, he had created the most powerful sculpture of the century.

Rodin had aimed not to depict Balzac’s body, but to channel his essence. “What makes my Balzac a sculpture,” he wrote, “is not the exact copy of the man, but the translation of his character into form.” The robe, far from a cover-up, became a second skin—an emotional terrain. The twisted stance, the massive head, the absence of overt gesture: these were the sculptural equivalents of literary labor, concentration, and isolation.

In 1899, this kind of abstraction was still shocking. But it would soon become the language of modern sculpture.

Material, Motion, and the Fragment

Rodin’s Balzac controversy cast a retrospective light over his entire oeuvre. Critics and supporters alike began to reassess earlier works—the restless, unfinished surfaces of The Gates of Hell, the sensual charge of The Kiss, the collapsing body of The Age of Bronze. What had once seemed sloppy or chaotic now looked deliberate: a philosophy of incompletion, an aesthetic of tension.

In 1899, Rodin’s studio continued to produce castings of earlier models, including new versions of The Thinker and The Burghers of Calais. But the public debate was no longer about subject matter. It was about method. Rodin’s partial figures, his jagged textures, his refusal to polish every surface—these became points of admiration or attack, depending on the viewer’s allegiance.

Three traits defined Rodin’s mature style by this moment:

- Surfaces that moved, catching light in broken rhythms rather than smooth planes.

- Anatomy that resisted idealization, emphasizing torsion, fatigue, and weight.

- A preference for expressive distortion over photographic accuracy.

In the sculptural world of 1899, this was radical. Most public monuments still clung to the neoclassical idiom—heroic nudity, symmetrical composition, polished marble. Rodin had torn all that away.

State Patronage, Private Tension

Ironically, while his Balzac was rejected, Rodin remained a favorite of the French state. He received commissions, honors, and invitations to exhibit abroad. But his relationship with official institutions was always ambivalent. He sought their approval, but resented their expectations. He wanted freedom, but not obscurity. In 1899, that tension became harder to manage.

The Balzac episode reminded him of what the public could not tolerate: ambiguity. His defenders within the avant-garde—especially critics like Gustave Geffroy and collectors like Maurice Fenaille—rallied to his side. But the institutional world was cautious. Museums hesitated. The French state did not purchase the Balzac. It would not be cast in bronze until 1939, decades after Rodin’s death.

Meanwhile, Rodin’s personal life was growing more complex. His lifelong partner, Rose Beuret, remained at his side, but his passionate (and increasingly strained) relationship with Camille Claudel haunted his studio and reputation. Claudel, herself a formidable sculptor, was struggling with mental health and professional marginalization. Their tangled history cast shadows over both artists’ careers.

Beyond Sculpture, Toward the Century

By 1899, Rodin was more than a sculptor. He was a symbol—a test case for how far art could push against tradition and still remain part of the public sphere. The controversy over Balzac was not just about one figure. It was about what kind of memory a nation could tolerate. Did monuments need to resemble their subjects? Did they need to flatter, to console, to idealize? Or could they disturb, challenge, provoke?

Rodin chose the latter path. And in doing so, he set the stage for modern sculpture—from Brancusi’s smooth abstractions to Giacometti’s haunted elongations. But in 1899, that legacy was uncertain. He had reached the summit. But the wind was rising.

Chapter 9: Edvard Munch’s Berlin Troubles

A Scandinavian Painter Struggles in Germany

In 1899, Edvard Munch was no longer a scandalous newcomer in Berlin. He was something more difficult to sustain: a polarizing presence with a damaged reputation and an uncertain audience. Five years had passed since his infamous 1892 exhibition at the Verein Berliner Künstler, which was shut down after just one week, denounced for its “un-German” spirit and “pathological” imagery. That incident made Munch famous—but not accepted. By 1899, he was trying to reenter Berlin’s art world on more stable terms. It did not go smoothly.

He returned to the city that year for exhibitions, negotiations, and studio visits. He hoped to establish himself not merely as a sensational import but as a serious artist with staying power. He was working on a new suite of paintings and lithographs—variations on his evolving Frieze of Life series—and was attempting to rebuild both his market and his morale. But the Berlin of 1899 was no longer the same experimental hotbed he had first encountered. Its avant-garde was fragmenting. Its critics were sharpening. And Munch himself was beginning to unravel.

Exhibiting Unease: The Frieze of Life Fractures

Munch’s central project at the time—the Frieze of Life—was an ambitious, nonlinear series of paintings and prints meditating on love, anxiety, jealousy, and death. Some of the key works had already been created earlier in the decade: Madonna (1894–95), Anxiety (1894), and The Scream (1893). But in 1899, he was developing new variations, particularly in printmaking, and attempting to sequence the works in a coherent whole.

That year, he exhibited a selection of Frieze paintings in Berlin, in private and semi-public venues, hoping to craft a more unified presentation of his psychological worldview. But coherence eluded him. The reception was mixed at best. Conservative critics still viewed his work as degenerate, hysterical, and dangerously foreign. Even among the avant-garde, enthusiasm was inconsistent. His art didn’t inspire allegiance—it provoked discomfort.

The discomfort was built in. In a lithograph version of Madonna produced in 1899, Munch added a swirling black background, red tinges, and a grotesque foetus in the corner—transforming the image of erotic transcendence into one of maternal ambivalence and death-haunted seduction. In another 1899 print, The Kiss IV, the lovers’ faces merge so completely that they lose individuality—a union bordering on suffocation.

These were not love stories. They were rituals of emotional breakdown.

Alien in a Changing Berlin

By the end of the decade, Berlin’s once-fractious art scene was becoming institutionalized. The Berlin Secession, founded in 1898 by Max Liebermann and others, aimed to provide a platform for modern art, but with certain limits: technical polish, aesthetic dignity, and emotional control. Munch didn’t fit that mold. He remained too raw, too Northern, too disturbing.

His supporters included a few collectors—most notably Max Linde, a patron from Lübeck who commissioned work and championed Munch’s psychological insight. But such allies were rare. In Berlin, he was still viewed as an outsider: a Norwegian with unstable technique, unwholesome themes, and a disordered personal life.

That disorder was becoming harder to conceal. Munch drank heavily. He fought with colleagues and lovers. His moods swung violently. He was haunted by memories of childhood illness and loss, and his own health—mental and physical—was deteriorating. Berlin had once thrilled him with its intensity. Now it simply overwhelmed him.

Three elements defined Munch’s Berlin experience in 1899:

- Ongoing suspicion from institutional gatekeepers despite prior notoriety.

- An evolving, but disjointed, Frieze of Life—deepening in symbolism but struggling to gain critical coherence.

- Mounting personal instability, bleeding into both his subject matter and his social standing.

The Art of Inner States

What Munch was painting in 1899 was not new in subject—but it was evolving in tone. His earlier works had sometimes relied on theatrical gesture: wide eyes, scream-filled mouths, angular postures. Now his figures became quieter, more petrified. They stood in twilight, turned away, submerged in shadow. The anxiety was no longer eruptive—it was ambient. A spiritual atmosphere rather than a narrative.

In works like Melancholy and Separation, he developed a visual language of emotional stasis. Bodies drifted apart or stood still against churning seas. The composition remained spare, the colors muted but emotionally charged. He wasn’t illustrating ideas—he was constructing mood.

Printmaking, especially lithography, allowed him to modulate these moods with astonishing control. His reworking of earlier images in 1899 reveals an artist not repeating himself, but refining his emotional grammar: a little more shadow, a heavier line, a deeper black.

Foreshadowing Collapse

Munch’s attempts to stabilize his reputation in 1899 would fail. The following years would see him plunge into greater personal crisis, culminating in a breakdown in 1908 that led to institutionalization. But the work he produced in this period—often overlooked—contains the essence of what made him great: not the famous scream, but the slow internal leak of dread.

He was not a dramatist. He was a chronicler of psychic climate.

In 1899, that climate was darkening. But from the fog of rejection and emotional turbulence, Munch continued to conjure forms—raw, difficult, and enduring.

Chapter 10: American Art’s Institutional Ascent

A Nation Builds Its Canon

In 1899, American art stood at an inflection point. After decades of artistic dependence on Europe—its academies, its critics, its tastes—the United States was beginning to assert itself as a cultural force with its own institutions, collectors, and ambitions. But this ascent was uneven, marked by internal contradictions and cultural anxieties. While American artists pushed to define a national aesthetic, their work was filtered through conservative academies, elite patrons, and still-fragile museums. The tension between originality and respectability shaped every decision: what to paint, how to paint it, and who got to see it.

Institutions played a central role in this drama. The National Academy of Design in New York, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, and newly expanding museum collections in Boston, Chicago, and Washington were building the scaffolding of American artistic authority. But in 1899, these institutions often favored a vision of art that looked backward rather than forward—celebrating narrative realism, genteel portraiture, and moralized genre scenes. The result was a canon in formation, but not yet in motion.

Cecilia Beaux and the High Craft of Restraint

Among the most prominent figures in this environment was Cecilia Beaux, whose career in 1899 stood as a counterpoint to the assumption that American women artists occupied a marginal place. Beaux, then in her mid-forties, was a portraitist of remarkable subtlety and technical control. Critics likened her to Sargent, and she was often favorably reviewed in the Century Magazine, Harper’s, and other elite publications.

In 1899, she exhibited her portrait Man with the Cat (Henry Sturgis Drinker) at the Pennsylvania Academy—an intimate, psychologically complex image of her brother-in-law posed in a Victorian parlor, hands folded, a white cat draped across his lap. It was both elegant and unsettling. The figure is enclosed, almost trapped, by patterned wallpaper, heavy furnishings, and domestic stillness. The effect is not decorative but diagnostic. Beaux reveals character through stillness, gesture, containment.

Her work reflected the American academic tradition at its best: refined, thoughtful, beautifully painted. But it also exposed the limits of the system. Beaux’s success, while significant, was framed as exceptional—her gender always mentioned, her femininity always described as a “graceful” addition to her skill. The institutions that praised her work were still hesitant to support female peers or students with equal seriousness.

Thomas Eakins and the Cost of Integrity

In stark contrast to Beaux’s growing acclaim, her former mentor Thomas Eakins remained semi-exiled from institutional favor in 1899. His forced resignation from the Pennsylvania Academy in 1886 (for allowing female students to study nude male models) had permanently altered his career. Although he continued to paint, his relationship with public exhibitions and commissions was strained.

Eakins’s output that year included Wrestlers (1899), a powerful, ambiguous painting of two men grappling on a mat—muscles taut, limbs intertwined, observed with anatomical precision and erotic tension. It was not a popular work. Critics found it uncomfortable, its homoerotic charge too visible, its subject too raw. Yet in hindsight, it was a masterpiece of American realism: unflinching, unsentimental, and deeply committed to the truth of the body.

Eakins embodied a form of artistic integrity that institutions found difficult to manage. He refused to flatter his subjects. He painted surgeons, rowers, and friends with an intensity that verged on psychological exposure. His work challenged the genteel decorum of the Gilded Age. And for that, he was pushed aside.

Three opposing forces were shaping the American art world in 1899:

- Institutional decorum, which favored respectable themes and polished style.

- Artistic realism, which demanded a closer, more difficult encounter with truth.

- Gender and class gatekeeping, which determined who could succeed—and how.

Patrons, Power, and the Making of Taste

American museums and collectors were not neutral observers. They shaped taste through acquisition, exhibition, and patronage. In 1899, Charles Lang Freer began acquiring large numbers of works by James McNeill Whistler, whose reputation was still ambivalent in America. Isabella Stewart Gardner in Boston was building the foundation of her Venetian palazzo museum, soon to house works by Titian, Sargent, and others. These private collectors often had more daring taste than public institutions—and more power to enact it.

But their preferences still reflected class aspirations. Gilded Age collectors sought art that signaled cultivation and refinement. They embraced the exotic, the decorative, the portrait. Radical experimentation had few buyers. There was little room, in 1899, for the kind of abstraction or symbolism that was emerging in Europe.

Yet within this polite world, change was beginning. The Art Students League in New York offered alternative instruction. The rise of photography challenged traditional ideas about portraiture and representation. And younger artists—many of them women—began to navigate new paths through illustration, design, and mural painting, often outside the academy’s reach.

The Institutions Begin to Shift

By the close of 1899, American art was not yet modern. But it was preparing. The structures were in place: schools, journals, collectors, museums. The question was what they would allow.

Beaux’s restraint, Eakins’s rigor, and Whistler’s ambiguity formed the poles of a triangle. Around them gathered others: John Henry Twachtman with his tonalist landscapes; Winslow Homer, still painting sea-driven dramas in Maine; and Mary Cassatt, active in Paris but increasingly influential at home. They were building, piece by piece, the foundations of a national visual language—one shaped as much by what was rejected as by what was shown.

In 1899, American art institutions offered both support and suppression. But out of that contradiction emerged a distinctive voice: serious, searching, and slowly becoming audible.

Chapter 11: The Stage as Canvas

When Painters Designed Performance

In 1899, the borders between visual art and live performance grew porous. Across Europe and Russia, artists turned their attention not just to what hung on walls, but to what moved on stages: opera, ballet, pantomime, cabaret. Designers, painters, and illustrators began to craft backdrops, costumes, and scenic concepts with the same seriousness once reserved for oils and frescoes. The result was a surge of theatrical innovation that transformed the stage into a living canvas—blurring the line between fine art and ephemeral spectacle.

This was not mere decoration. What emerged in the final years of the 19th century was a new understanding of performance as total design—a synthesis of gesture, movement, color, and form. Artists trained in composition and draftsmanship brought their sensibilities into rehearsal rooms and dressing halls. The theatres of Moscow, Paris, and Munich became experimental spaces where symbolism, abstraction, and emotional intensity could unfold in real time.

By 1899, this crossover was no longer an exception—it was a current. Painters who once disdained theatre now embraced it. The results were unpredictable, but they carried unmistakable energy. A century born in galleries was preparing to enter the spotlight.

Paris: Maeterlinck, Mélisande, and the Shadow Stage

One of the most influential theatrical works of the era, Maurice Maeterlinck’s Pelléas et Mélisande, premiered in 1893. But its visual aftershocks continued into 1899, as artists and designers across Europe attempted to give form to its strange, dreamlike world. In Paris, Symbolist theatre companies such as Lugné-Poe’s Théâtre de l’Œuvre staged plays in dimly lit spaces, with misty backdrops and simplified sets inspired by Japanese screens and medieval tapestries.

Painters including Pierre Bonnard and Maurice Denis contributed scenic designs to these productions, treating the stage not as a place for realism but for mood. Denis’s sets for Axël and other Symbolist dramas rejected illusionistic space, favoring flattened planes, bold silhouettes, and spiritual resonance. The goal was not to simulate nature, but to evoke psychic states.

By 1899, this approach had become a model. Posters for productions were often designed by the same artists involved in set creation, reinforcing the idea of unity between public image and stage environment. A production was no longer just a script—it was a spatial event.

Three theatrical trends became clear in Paris at century’s end:

- Flattened pictorial space in scenic design, echoing Symbolist painting.

- Lighting as narrative, with dim, colored effects replacing naturalism.

- Actors as icons, their movements stylized to match visual themes.

This was theatre as tableau vivant: not realism, but revelation.

Moscow: The First Ripples of a Russian Revolution

In Moscow, a quieter but more foundational transformation was underway. In 1898, the Moscow Art Theatre had staged its landmark production of Chekhov’s The Seagull, directed by Konstantin Stanislavski and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko. The production was hailed for its naturalism and psychological depth. But in its wake, another force began to stir: the idea that theatre could also be formal, symbolic, abstract.

By 1899, Russian artists like Léon Bakst and Alexandre Benois—founding members of the group Mir Iskusstva (“World of Art”)—began to explore theatrical design as an extension of their painterly practice. Though their major contributions would come in the following decade with the Ballets Russes, the seeds were planted in this year: sketches, costume designs, studies of theatrical gesture.

The World of Art group, centered in St. Petersburg but active in Moscow circles, brought with it a commitment to elegance, stylization, and pan-European visual sensibility. They saw in theatre a way to re-enchant public experience—drawing on Rococo, Persian, Byzantine, and early modern styles. For them, the stage was not a machine. It was a mirror of cultural memory.

Though large-scale productions were still rare, their vision shaped the aesthetics of Russian performance for decades. What they imagined in 1899 would become reality in the 1900s.

Munich and Vienna: Gesamtkunstwerk Emerges

Meanwhile, in German-speaking Europe, the Wagnerian concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk—the total work of art—was finding new expression in theatre and design. In Munich, members of the Jugendstil movement collaborated on productions that fused architecture, costume, and narrative into unified experiences. In Vienna, the Secessionists brought theatricality to exhibition design itself, blurring the distinction between performance and installation.

Artists like Koloman Moser and Alfred Roller—both active by 1899—began designing not only objects and interiors but also theatrical sets. Roller, in particular, would soon become a leading figure in operatic design, influencing Gustav Mahler’s productions at the Vienna Court Opera. But even at this earlier date, the aesthetic principles were in place: clarity of line, symbolic color, and spatial rhythm.

These artists didn’t see the stage as separate from their main practice. Rather, they understood it as the most public arena in which art could operate. It was there that composition came alive.

Art That Moves

Theatre in 1899 was no longer just about drama. It had become a field of experimentation for visual form—transient, collaborative, and emotionally immediate. Artists used it to test ideas they could not contain on canvas. Space became narrative. Color became mood. Gesture became design.

The impulse to integrate all arts—painting, music, costume, story—was not new. But in 1899, it accelerated. What had once been decoration became dramaturgy. What had once been background became substance.

Soon, this impulse would culminate in the revolutionary productions of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, the expressionist theatres of Weimar Germany, and the multi-sensory designs of the Bauhaus stage. But in 1899, the stage was just beginning to shimmer with artistic ambition.

It was the art world’s first step into motion.

Chapter 12: Toward the 20th Century

What the Century Had Already Let In

Standing on the brink of 1900, it becomes clear that the future had already begun to seep into the art of 1899—not through rupture, but through slippage. No single movement, manifesto, or style declared the arrival of modernism that year. And yet, the boundaries that had defined 19th-century art—between genre and experimentation, between representation and mood, between artist and institution—had begun to dissolve. What remained was a field of possibility, saturated with tension.

The transitions were not always loud. In Paris, Bonnard’s shrinking rooms whispered a new kind of pictorial privacy. In Berlin, Munch’s disintegrating figures carried dread across the gallery wall. In Vienna, Klimt’s decorative masks began to fracture under their own gold. These were not revolutions, but shifts in gravity—small tilts in orientation that would, within a few years, unmoor the entire structure of academic art.

The year 1899 was not a prelude to modernism. It was part of it. Modernism, before it had a name, was already present in the form of doubt.

The Shape of the New to Come

One way to read 1899 is through its unresolved contradictions. Symbolist introspection thrived alongside imperial spectacle. Craft was celebrated, yet subordinated to class systems. Artists sought spiritual depth through myth, but also surrendered to surface. Decoration was both escape and critique.

Even the best-known artists of the year—Rodin, Klimt, Whistler—were struggling against the constraints of the institutions that celebrated them. Rodin’s Balzac was rejected. Klimt’s early Secession works scandalized even his peers. Whistler, revered but ill, retreated into increasing secrecy. None of them fit comfortably into the national narratives forming around them.

Meanwhile, lesser-known movements were germinating in quiet: Edvard Munch’s anxiety-laden imagery in Berlin, the Mir Iskusstva circle in St. Petersburg, early stirrings of abstraction in color theory and decorative design. No one could yet predict Kandinsky, Picasso, or Malevich. But the forms that would make them possible—flattened perspective, symbolic color, expressive distortion—were already coalescing.

Three tendencies stand out as signals of what was already modern in 1899:

- Form was beginning to speak as content. In Rodin’s sculpture, in Vuillard’s interiors, in Moser’s posters, the shape of things began to carry meaning independently of narrative or allegory.

- The subject became unstable. Figures blurred into their surroundings. Identity dissolved into gesture or atmosphere. Portraiture no longer promised psychological clarity.

- Mediums crossed boundaries. Printmaking, poster art, set design, and decorative objects became central, not peripheral, to artistic innovation.

The radical transformations of the early 20th century—Cubism, Expressionism, Futurism, Constructivism—would push these tendencies to extremes. But their roots are visible in 1899, not as ruptures, but as quiet deviations.

Memory, Melancholy, and the Year That Closed

Looking back from the 21st century, it is tempting to cast 1899 as the end of an era—a final bow before the curtain of war, ideology, and industrialized modernity fell over the continent. The temptation is understandable. The Habsburg empire still stood. Paris still sparkled. The trains still ran on time to the salons and theatres and lakeside sanatoria. But such a view misses the deeper tremors that year.

There was fear in the air. Fear of obsolescence, of degeneration, of mechanized life. Fear of women stepping into public space. Fear of sexual ambiguity. Fear of loss—of belief, of God, of center. The art of 1899 did not soothe these fears. It recorded them. Stylized them. Reflected them back.

Yet alongside fear was vision. Even the most inward-looking works of the year carried seeds of imagination: a new way of seeing, of being, of arranging the world. From Bonnard’s wallpapers to Barrias’s veils, from Mucha’s posters to Redon’s apparitions, artists searched for forms that could hold meaning when belief had frayed.

Their search did not end with resolution. But it began something.

The Century Opens, Already in Motion

What followed 1899 is familiar: the roaring acceleration of modernism, the trauma of war, the disintegration of old orders. But what came before it is harder to see—and perhaps more instructive. The year did not announce a break. It hummed with hesitation. The painters, sculptors, designers, and dreamers of that time were not yet radicals. But they were already off balance.

That is what makes the art of 1899 so compelling. It reveals a world that could still pretend to continuity, even as its seams began to show. A world of extraordinary beauty that could no longer explain itself. A world that, unknowingly, had already begun to change.