Modern Art is often confused with Contemporary Art, but the two represent vastly different eras, mindsets, and artistic commitments. Modern Art refers to the movement that emerged in the late 19th century and flourished through the mid-20th century. Artists in this period were reacting to the rapid changes brought about by industrialization, urbanization, and shifting cultural values. Yet, even as they broke from traditional academic rules, they never lost their reverence for beauty, form, and the human experience.

This period includes iconic movements like Impressionism, Cubism, Fauvism, Surrealism, and Abstract Expressionism. These styles shared one common thread: they evolved from solid artistic foundations. For example, Claude Monet, a founding figure in Impressionism, had a classical education in drawing before painting his iconic Impression, Sunrise in 1872. Similarly, even as Pablo Picasso revolutionized form through Cubism, his early works from the Blue Period and Rose Period (1901–1906) show remarkable technical skill rooted in realism.

Modern artists grappled with the meaning of life, faith, loss, progress, and the complexities of the 20th century. Whether it was Edward Hopper capturing urban loneliness or Marc Chagall weaving Jewish folklore into fantastical dreamscapes, these artists conveyed deep emotional resonance through visual mastery. The art of this era honored the viewer by making work that was not just intellectual but also deeply accessible.

What set Modern Art apart was its pursuit of truth and universality. Whether abstract or representational, artists aimed to say something that transcended the temporary. The paintings weren’t just meant for elite theorists—they were meant to move anyone with eyes to see.

From Impressionism to Cubism: Innovation with Discipline

The birth of Modern Art began with the Impressionists in the 1860s, particularly in France. These artists, including Monet, Renoir, and Degas, rejected the rigid demands of the French Academy but remained dedicated to portraying real-life scenes with honesty and light. Their brushwork became looser, and they captured fleeting moments, yet always with discipline.

By the early 20th century, Modern Art had evolved into Cubism, a movement spearheaded by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Their 1907–1914 work, including Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), deconstructed form into geometric shapes. But even at its most radical, Cubism retained spatial understanding, composition, and a reverence for three-dimensional form. These weren’t just scribbles on canvas—they were grounded studies in structure and perception.

Movements like Fauvism, pioneered by Henri Matisse around 1905, pushed color beyond realism but still aimed at emotional impact. The Surrealists of the 1920s, including Salvador Dalí and René Magritte, painted dreams with painstaking realism. And in the 1940s and 50s, Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko experimented with spontaneity and scale, yet continued to demand something from the viewer: awe, introspection, and wonder.

Modern Art, in all its diversity, never let go of the basic understanding that art should be meaningful and skillfully executed. Even the most radical Modern works reflect years of training and genuine artistic intention.

Modern Masters: Picasso, Monet, and Rothko

Claude Monet, born in 1840, studied at the Académie Suisse in Paris and became a key figure in breaking away from rigid formalism. He painted the same haystacks at different times of day—not out of laziness, but to study the effects of light, air, and atmosphere. His Water Lilies series, painted between 1897 and 1926, remains one of the most beloved examples of harmony between man and nature.

Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) began drawing at age seven and was admitted to Barcelona’s School of Fine Arts at just 13. Though remembered for his abstract work, early pieces like Science and Charity (1897) show his academic mastery. His transition into Cubism wasn’t a rejection of skill—it was a reinterpretation based on deep understanding.

Mark Rothko (1903–1970), often dismissed by critics of abstract art, was deeply philosophical. His massive color field paintings from the 1950s and 60s were carefully layered and composed to evoke spiritual reflection. He famously said, “The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them.” Whether one loves or hates his work, Rothko’s paintings were never superficial.

These men, among others, left behind a legacy rooted in skill, conviction, and the desire to elevate the viewer, not alienate him.

Key Modern Art Movements:

- Impressionism

- Fauvism

- Cubism

- Surrealism

- Abstract Expressionism

What Defines Contemporary Art?

Contemporary Art generally refers to art produced from the 1970s to the present. While it may visually resemble Modern Art at times, it fundamentally differs in philosophy and purpose. Rather than seeking beauty or truth, much of Contemporary Art focuses on identity, politics, irony, and sometimes sheer provocation. Concepts often matter more than execution.

This shift began as early as the late 1950s, with artists like Marcel Duchamp laying the groundwork. His infamous Fountain (1917)—a porcelain urinal signed “R. Mutt”—was later reinterpreted by conceptual artists as proof that “anything can be art.” From there, the idea began to replace the image, and artistic skill was devalued.

By the 1990s, the landscape had shifted dramatically. Conceptualism, minimalism, performance art, and installation pieces dominated gallery spaces. These works often required elaborate wall texts or theoretical context to be understood. Art was no longer about what was on the canvas, but the commentary surrounding it.

Contemporary Art often aligns itself with social or political causes. It’s not uncommon to find exhibitions centered around climate activism, gender identity, or historical grievances. The artist’s intent is frequently more political than aesthetic. This isn’t creation—it’s activism masquerading as art.

Concept Over Craft: The Death of Technique

Many contemporary artists lack even basic training in anatomy, color theory, or perspective. Instead of years spent mastering a brush, artists now may submit found objects, digital files, or performance stunts. This isn’t just a stylistic shift—it’s a philosophical rejection of traditional standards.

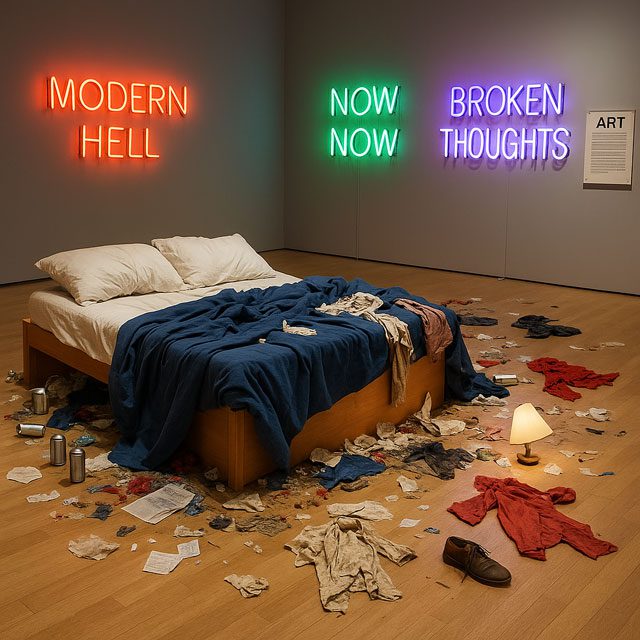

The 1999 Turner Prize was awarded to Tracey Emin for My Bed, which was literally her unmade bed surrounded by cigarette butts, used underwear, and stained sheets. The message? Something vague about vulnerability and personal trauma. But the product itself required no craftsmanship—only the willingness to shock.

In 2019, Maurizio Cattelan famously taped a banana to a wall at Art Basel Miami Beach and called it Comedian. It sold for $120,000. There was no innovation in material, no technique, no emotional resonance—just irony and status signaling.

This trend of valuing provocation over creation has hollowed out the soul of art. Technique is not elitist—it’s the very foundation of communication through image.

The Rise of Identity Politics and Activism in Art

Today’s art world is heavily influenced by the language of inclusion, equity, and social justice. While artists have always responded to their times, Contemporary Art often feels like a lecture, not a revelation. The goal is frequently to make a statement, not to make something meaningful.

Art institutions like the Tate Modern or MoMA have entire curatorial departments focused on “decolonizing the museum” or “queering the gallery space.” These efforts often elevate art based on the artist’s background rather than the quality of the work.

NEA funding and university art programs now prioritize ideological content. Grants often ask whether a piece “addresses systemic inequity” before asking if it’s any good. When art becomes a vessel for ideology, rather than expression, it stops being art and becomes propaganda.

This environment discourages dissent and breeds sameness. Artists toe the ideological line to gain visibility, funding, and exhibitions—not because they believe in the message, but because they must.

The Beauty Standard: Lost or Rejected?

Modern Art, even in its most radical expressions, never lost sight of beauty. Whether it was Monet’s luminous gardens or Matisse’s vibrant still lifes, there was always an intention to create harmony and evoke joy or introspection. Contemporary Art, on the other hand, frequently dismisses beauty as outdated, oppressive, or irrelevant.

Beauty in art used to be an ideal—something to strive toward. In Classical and Renaissance traditions, beauty was associated with order, proportion, and divinity. Even in abstraction, Modern artists sought balance and emotional impact through visual form. Beauty was not mere decoration; it was a pathway to truth.

In today’s art world, beauty is often treated with suspicion. Artists are praised for being “subversive” or “transgressive” rather than beautiful. Ugly or chaotic works are applauded because they supposedly challenge societal norms. But in reality, they often just reflect a culture that has forgotten how to aspire to higher ideals.

This rejection of beauty has consequences. A society that no longer honors beauty in art is less likely to honor beauty in behavior, belief, or tradition. When ugliness is normalized, it doesn’t just stay on the canvas—it seeps into everything.

Harmony and Proportion in Modern Works

Harmony and proportion were central to the achievements of Modern artists. Even when departing from realism, they maintained internal consistency. Consider the work of Piet Mondrian, whose Composition with Red, Blue and Yellow (1930) may appear simple, but it was meticulously planned for balance.

Similarly, Georges Braque and Picasso’s Cubist compositions broke down the visible world but reassembled it with logic and visual rhythm. These works demonstrate a belief in structure and coherence, even in abstraction.

Even Abstract Expressionists like Rothko or Barnett Newman sought sublime impact through color and proportion. Their works weren’t random; they were studies in emotional resonance through minimal form. Viewers responded not to chaos, but to the deliberate crafting of mood and space.

This underlying respect for order is what separates Modern Art from much of today’s chaos-in-a-frame. Even when abstract, it honored the viewer’s intelligence and aesthetic sensitivity.

Deconstruction and the Aesthetics of Decay

In contrast, many Contemporary artists take pride in deconstruction—breaking things down without the intention to rebuild. This reflects a broader cultural cynicism. If Modern Art was about searching for meaning, Contemporary Art often revels in its absence.

The aesthetic of decay—whether literal or symbolic—is now a common theme. Works made of garbage, decaying food, or industrial debris aim to comment on waste, consumerism, or mortality. But too often, these messages feel shallow, because the art itself lacks depth or resonance.

British artist Damien Hirst, for example, gained fame for suspending dead animals in formaldehyde. His 1991 piece The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living features a 14-foot shark in a glass tank. It’s shocking, yes—but is it beautiful? Is it meaningful beyond its gimmick?

Rather than edifying the viewer, many of these works numb or confuse. They mirror cultural decay rather than offer a way out of it.

Skill, Training, and Craftsmanship Then vs. Now

One of the most glaring differences between Modern and Contemporary Art is the decline of skill and craftsmanship. Modern artists, even those who experimented with abstraction, typically spent years studying drawing, anatomy, and classical techniques. Their creativity was built on a foundation of hard-earned knowledge. Today, many contemporary artists receive little to no technical training, instead focusing on theoretical approaches and personal expression.

Artists like Edgar Degas and Édouard Manet trained rigorously under academic painters. Degas, for instance, enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1855 and spent time copying Old Masters in the Louvre. This practice wasn’t about imitation—it was about understanding line, proportion, and form. Such discipline gave artists the ability to innovate without abandoning excellence.

Even abstract painters like Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee had solid grounding in composition and color theory. Kandinsky’s Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1911) shows deep intellectual and technical engagement with his medium. These weren’t untrained rebels—they were serious thinkers with formidable skills who chose abstraction as a means to elevate emotion, not to excuse a lack of ability.

Contemporary art programs today often prioritize conceptual development over technical proficiency. Studio courses may spend more time discussing “identity narratives” or “cultural displacement” than teaching how to draw a human figure or paint with oils. This shift has created a generation of artists who can talk about art but struggle to produce anything visually compelling.

Atelier Tradition vs. MFA Conceptualism

The atelier model—where students worked under the guidance of a master—was the gold standard of artistic education for centuries. Students spent years copying plaster casts, studying anatomy, and learning to observe the world with precision. This was the tradition inherited by many 19th- and early 20th-century artists, and it laid the groundwork for their later innovations.

By contrast, the rise of the Master of Fine Arts (MFA) system in the mid-20th century marked a significant change. Many MFA programs, particularly after the 1960s, moved away from technical training and embraced a more theoretical and critical studies approach. Courses in “visual semiotics” or “postcolonial frameworks” replaced life drawing and plein air painting.

This trend has accelerated in recent decades. It is now possible to complete a fine arts degree without ever mastering perspective, human anatomy, or color mixing. The result is a body of work that may be politically loud or conceptually dense—but visually underwhelming.

While some ateliers and classical academies have seen a revival in recent years, they remain the exception rather than the rule. Most art schools continue to produce graduates skilled in academic jargon, but lacking the tools to create beauty.

What Happened to Drawing and Painting Skills?

In the past, drawing and painting were essential to any serious artist’s education. Mastery of the figure, the landscape, and still life provided a visual vocabulary through which complex ideas could be expressed. Artists were not only creators, but craftsmen. Today, these skills are often viewed as old-fashioned or even oppressive by contemporary institutions.

This neglect is evident in many contemporary galleries. It’s not uncommon to find video installations, piles of dirt, or abstract prints accompanied by long descriptions—but no actual drawing or painting. When drawing does appear, it’s often intentionally crude or ironic, signaling a disdain for tradition rather than engagement with it.

The abandonment of skill is not a neutral choice. It reflects a cultural moment that values commentary over clarity, disruption over discipline. Without the ability to render an idea with precision, many artists fall back on spectacle, digital tools, or political content to gain attention.

There are, of course, exceptions—some contemporary artists are skilled draftsmen and painters—but they are rarely promoted by major institutions unless their work fits a prevailing ideological mold.

The Role of Meaning: Genuine vs. Manufactured

Modern Art often addressed the universal: love, loss, spirituality, fear, nature, and the human condition. Even when abstract, its aim was to elevate or illuminate something shared by all. Contemporary Art, by contrast, frequently wraps itself in ambiguity or irony. Meaning becomes either impossibly abstract or narrowly ideological, making the work inaccessible or divisive.

Jackson Pollock’s Number 1, 1950 (Lavender Mist) isn’t easy to interpret, but it communicates a raw intensity, a form of spiritual ecstasy through motion and form. His drip technique may look chaotic, but it was anything but random. His work wasn’t about Pollock—it was about emotion, energy, and being.

In contrast, many contemporary works require written statements longer than the piece itself to explain their “meaning.” A row of used milk cartons in a gallery might be said to “challenge the hegemony of domestic gender roles.” A broken mirror installation may claim to “interrogate surveillance capitalism.” Without the wall text, the viewer is left bewildered or indifferent.

This over-reliance on theory and explanation separates contemporary pieces from the universal appeal of earlier art. If a painting requires a degree in cultural studies to be understood, it’s not communicating—it’s hiding behind abstraction.

Modernism’s Search for Universal Truth

Modern artists believed in something higher. Whether it was truth, beauty, or the divine, their work pointed beyond themselves. Wassily Kandinsky believed color and form could communicate spiritual truths. Georgia O’Keeffe used large, vibrant floral imagery to evoke emotional responses rooted in nature, not ideology.

Even during the chaos of World War I and II, Modern artists often responded with a call for meaning. In the wake of destruction, they created works that tried to reassert human dignity and emotional resilience. This is seen in the post-war works of Henry Moore and even in the somber abstraction of Rothko.

Modernism was, in many ways, a conversation between the artist and mankind. It asked: What does it mean to be alive in this time? How can form and color help us understand our place in the world? The answers were not always literal, but they were honest attempts to make sense of things.

This search for universal meaning gave Modern Art a sense of weight. It wasn’t always beautiful in the traditional sense, but it always sought to express something real.

Contemporary Art’s Obsession with the Niche

In contrast, much of Contemporary Art is preoccupied with the niche, the personal, and the hyper-political. Art is often used as a vehicle for identity narratives or ideological points, and the result is a form of cultural balkanization. Rather than appealing to shared experiences, many works emphasize difference, grievance, or marginality.

This trend has been encouraged by the academic and curatorial class, which rewards work that aligns with fashionable political ideologies. Artists are praised for “disrupting norms” or “amplifying voices,” but rarely for achieving beauty, clarity, or depth.

The obsession with niche perspectives also makes much of today’s art ephemeral. Once the political context changes—or the ideology loses popularity—the work often loses its relevance. It becomes a time capsule of fleeting discourse, rather than a timeless expression of the human spirit.

This is not to say art cannot be political. But when politics become the only lens through which art is made and judged, something essential is lost.

Patronage, Politics, and Power in the Art World

Modern Art rose in a world where patronage was still based, to some extent, on merit. Collectors, museums, and even governments sought out works that displayed skill, innovation, or emotional power. Today, the art world is deeply entangled in political ideology and institutional power plays. Grants, exhibitions, and even critical reviews are often awarded based on ideology rather than excellence.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, collectors like Peggy Guggenheim, Albert Barnes, and Gertrude Stein supported artists not because of their political views but because of the unique vision and talent they offered. Their patronage helped launch the careers of Modigliani, Pollock, and others.

Since the 1970s, however, state-funded institutions and university art departments have played an increasingly dominant role. Bureaucracies like the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) began granting money based on social messaging rather than visual achievement. The infamous funding of Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ in 1987 is a prime example. The backlash wasn’t just about the subject—it was about the taxpayer being forced to subsidize sacrilege disguised as art.

Today, many prominent art fairs and galleries require artists to align with ideological buzzwords to be considered. Terms like “decolonize,” “climate justice,” or “post-human” appear more frequently in press releases than “beauty” or “craft.” Artists are no longer just creators—they’re expected to be political actors.

The Old Art Patron vs. The Modern Bureaucrat

The classical patron took risks on new talent, often providing them with housing, materials, and access to networks. Patrons didn’t need degrees in art theory—they needed eyes and instincts. They valued beauty, originality, and the impact a piece could have on viewers, not whether it checked every sociopolitical box.

In contrast, today’s funding bodies are bureaucracies mired in paperwork, politics, and panels. Grant applications ask for community impact statements and diversity metrics, not portfolios of prior work. The artist’s background and political alignment often matter more than their output.

This shift discourages artistic risk-taking in the traditional sense. Artists must conform ideologically to secure funding, leading to homogenous work that says the same things, in the same style, using the same phrases. Instead of inspiring a generation of visionaries, the system rewards conformity.

Art has become a branch of policy implementation rather than an independent creative pursuit.

Art Fairs, Grants, and the Politics of Inclusion

Major art fairs like Art Basel and Frieze are not merely marketplaces—they are ideological showcases. Galleries curate works that align with current socio-political narratives to remain in the good graces of critics and buyers. The result is an echo chamber of art that reinforces elite talking points rather than challenging or elevating culture.

Grants and residencies are often awarded based on inclusionary goals rather than merit. Artist collectives boasting “queer decolonial praxis” or “intersectional abolitionist frameworks” are more likely to receive institutional support than a skilled oil painter exploring beauty or faith. This is not diversity—it’s dogma.

Inclusion should mean broadening the range of voices and styles—but in practice, it has meant narrowing them to a handful of approved themes. The aesthetic variety of the Modern period has given way to uniformity under the guise of pluralism.

Without a course correction, the art world risks becoming completely irrelevant to anyone outside its ideological bubble.

Public Response: Ordinary People Know What’s Good

While the art elite continues to celebrate conceptual installations and identity-driven performance pieces, the general public often responds very differently. Put simply, ordinary people still prefer beauty, skill, and emotional resonance. When crowds gather at museums, it’s not to stare at a pile of bricks or a flickering video loop—it’s to marvel at a Monet or a Van Gogh.

The average person may not have a degree in art history, but they know what speaks to their soul. A Rembrandt portrait or a Hopper cityscape elicits admiration and reflection. These works don’t require a lecture to be understood—they communicate directly, often powerfully, across cultures and generations. This is precisely why Modern Art remains broadly popular.

Contemporary Art, on the other hand, often leaves viewers cold or bewildered. Exhibits featuring garbage, bodily fluids, or offensive imagery may provoke curiosity or controversy, but rarely inspire lasting appreciation. Visitors may chuckle or frown at the spectacle, but few return for a second look. The experience becomes more about the stunt than the substance.

This disconnect between elite taste and public preference exposes a deeper issue: the cultural divide between the art world and the rest of society. The public still wants art that uplifts, inspires, and educates—not art that mocks their values or tests their patience.

Modern Art’s Mass Appeal

The enduring appeal of Modern Art is easy to measure. Exhibitions of Monet, Van Gogh, or Matisse consistently break attendance records at major institutions. A 2019 exhibit of Van Gogh’s work at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston drew more than 400,000 visitors in just a few months. These works still move people—because they combine vision with craftsmanship.

Posters and prints of Modern works are staples in homes, classrooms, and public spaces. You don’t see many people hanging prints of conceptual toilet installations or smeared canvas rants about global warming. Modern Art speaks in a language that doesn’t go out of style—form, color, emotion, and beauty.

Public appreciation is also evident in the success of digital exhibits like “Van Gogh Alive” or “Monet & Friends,” which draw crowds worldwide. Even the digital age hasn’t diminished the hunger for meaningful, visually rich art.

Modern Art continues to resonate because it honors timeless human themes while remaining visually accessible. It is a legacy of sincerity, not sarcasm.

Contemporary Art’s Insider Club

Contemporary Art often functions as an insider’s game. It requires specialized knowledge, ideological alignment, or a decoder ring to fully “get” what’s being presented. The result is a closed circle of curators, critics, and collectors congratulating one another while the public remains alienated.

Some of this exclusivity is intentional. It keeps Contemporary Art niche, provocative, and “edgy,” while reinforcing the idea that those who don’t understand it are simply unsophisticated. But when art becomes a series of in-jokes or ideological checklists, it ceases to be a shared cultural language.

This phenomenon helps explain why many people feel unwelcome or uninterested in modern gallery spaces. Instead of inviting contemplation or joy, they deliver confusion or ideological posturing. They don’t connect—they confront.

In this context, it’s no surprise that ordinary viewers gravitate to the works of Modern masters, while elite circles continue to elevate art that requires justification more than appreciation.

Notable Examples of Contemporary Art Confounding the Public:

- Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian (banana duct-taped to wall)

- Tracey Emin’s My Bed (unmade bed with personal debris)

- Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ (photograph of a crucifix in urine)

- Martin Creed’s Work No. 227 (lights turning on and off in a room)

- Entire exhibitions consisting of blank canvases or empty rooms

Museums and Market Manipulation

The modern museum system has increasingly abandoned its mission to preserve beauty and cultural excellence. Instead, it often functions as a marketing machine, inflating the value of vapid or offensive work through sheer visibility. This manipulation of the market benefits a handful of insiders—curators, dealers, and speculative investors—while diminishing public trust.

Unlike the natural appreciation of Modern masterpieces, the value of many Contemporary works is artificially manufactured. Shock value, name recognition, and media coverage do more to drive price than quality or emotional impact. A banana taped to a wall can sell for six figures—not because it’s good, but because it made headlines.

Auction houses like Christie’s and Sotheby’s play a significant role in this inflation. Works by living artists sometimes fetch millions based on trendiness rather than merit. It’s a game of speculation—art as investment portfolio, not cultural treasure.

This has led to a system where monetary value is detached from intrinsic artistic worth. Real talent often goes unnoticed, while absurdity is praised as innovation—so long as it generates clicks and cash.

Auction Houses and Artificial Scarcity

The economics of Contemporary Art often rely on artificial scarcity and hype. Artists produce limited editions or single installations, which are promoted as groundbreaking, controversial, or avant-garde. These works are then auctioned off to wealthy collectors who view them as assets rather than expressions of the human spirit.

The famous “shredding” of Banksy’s Girl with Balloon during a 2018 Sotheby’s auction is a case in point. The artwork partially self-destructed after selling for $1.4 million. Instead of being a critique of commodification, the stunt actually increased the piece’s value. It was a media event disguised as art, and the art world applauded.

Such manipulations drive up prices while detaching the work from meaning. The result is a marketplace that favors spectacle over substance and leaves traditional, skilled artists without a foothold.

This is not how culture should work. Art that matters should be appreciated because of its beauty, depth, and craft—not because it made headlines.

Gatekeeping in Curatorial Circles

Today’s curators often act as gatekeepers, deciding which artists deserve attention, funding, and inclusion in prestigious shows. Their decisions are rarely based on technical ability or emotional power. Instead, they reward ideological conformity and conceptual novelty.

Major institutions like the Tate Modern or the Whitney frequently promote work that advances a progressive narrative or challenges “normativity.” Traditional painters and sculptors, no matter how skilled, are often left out unless they adapt to these prevailing themes.

This curatorial gatekeeping has created a predictable pattern in gallery exhibitions. The same types of artists, themes, and materials are presented over and over again, often wrapped in similar language about “decolonization,” “gender fluidity,” or “climate justice.”

Such conformity doesn’t just stifle creativity—it erodes public trust. When art becomes a tool for activism and elitism, its ability to unite and inspire is lost.

How We Got Here: Cultural Decline and the Postmodern Mindset

The shift from Modern to Contemporary Art parallels a broader cultural change—a turn away from shared values and toward relativism, irony, and fragmentation. At the heart of this transition lies postmodernism: a worldview that rejects objective truth, deconstructs meaning, and distrusts tradition.

Beginning in the 1960s and 70s, art schools and intellectual circles embraced postmodern theory. Influenced by thinkers like Foucault and Derrida, they argued that meaning was subjective, that beauty was a social construct, and that all grand narratives were oppressive. In this environment, irony replaced sincerity, and identity replaced universality.

Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) is often seen as the first shot fired in this direction. By submitting a urinal as art, Duchamp declared that context, not creation, defines artistic value. While this might have been provocative in 1917, the message became a crutch for lesser artists in the decades that followed.

As these ideas took hold, traditional standards were cast aside. Art stopped aiming at transcendence and began orbiting around critique. The goal was no longer to express beauty or truth—but to challenge, disrupt, and deconstruct.

The Impact of Postmodern Philosophy on Art

Postmodernism ushered in a view of art as text—something to be “read,” decoded, and interpreted through endless layers of meaning. Beauty became suspect, as did craftsmanship. What mattered was subverting expectations, not satisfying them.

This philosophical shift found fertile ground in academia and spread to museums and galleries. Terms like “intertextuality” and “hyperreality” began replacing “composition” and “aesthetic.” The artist became a theorist rather than a maker.

In this intellectual soup, standards dissolved. If all meaning is relative, then nothing is sacred—not technique, not tradition, not even truth. Art became a mirror to a culture that had lost confidence in itself.

The consequence? A gallery world full of cleverness but devoid of heart.

When Standards Died: From Duchamp to the Present

Once Duchamp declared that anything could be art, the floodgates opened. What began as a challenge to convention became an abandonment of excellence. By the 1980s, shock art had replaced sincerity, and by the 2000s, politics had replaced beauty.

Art once aimed for permanence. The Sistine Chapel, the Mona Lisa, and even Guernica were created to last. Contemporary Art, by contrast, is often made of trash, food, or digital ephemera. Its message is temporary—and so is its value.

With no standards, anything goes. And when anything goes, nothing matters.

What Can Be Done? Restoring Art’s Purpose

The current state of art is not inevitable, and it is not irreversible. A cultural renewal is possible—but it requires courage, vision, and a return to timeless values. Beauty, discipline, meaning, and craftsmanship must once again become central to artistic creation.

Artists must be trained—not just encouraged. They should learn to draw, to paint, to sculpt, and to observe the world with reverence. Technique should not be seen as elitist, but as the foundation of expression. Without it, creativity flounders.

Collectors and patrons play a critical role as well. Rather than investing in shock or fashion, they should support artists who honor tradition and aim for lasting impact. Funding should be based on quality, not ideology.

Museums and critics must begin to reward genuine excellence. That means recognizing beauty as a legitimate goal—and rejecting the notion that offense or novelty alone constitute artistic merit.

Supporting Classical Training and Art Renewal

A growing movement of ateliers, classical academies, and traditional art schools offers hope. Institutions like the Florence Academy of Art and Grand Central Atelier are bringing back serious training. These schools teach observation, anatomy, and technique in ways that the Modern masters would recognize—and approve of.

Young artists who seek meaning, skill, and beauty now have options outside of the mainstream. They can build careers based on quality, not conformity. But they need support—from collectors, curators, and communities willing to stand against the current.

Renewal begins with education. If we want art to mean something again, we must train artists not just in theory, but in mastery.

The Role of Critics, Collectors, and Communities

Critics must recover their integrity. Rather than parroting political talking points or celebrating the obscure, they should champion work that uplifts and endures. The critic’s role is not to be a mouthpiece for ideology, but a guide for the public.

Collectors, meanwhile, must put their money where their values are. Buying beauty is not nostalgia—it’s an investment in civilization. Supporting good artists today will determine what survives tomorrow.

Communities can help by creating demand for beauty. From local galleries to public art projects, we can choose to elevate what is true, not just what is trendy. Art is a reflection of who we are—and who we hope to become.

Key Takeaways

- Modern Art emphasized beauty, meaning, and technique, unlike much of Contemporary Art.

- Contemporary Art often replaces skill with ideology, spectacle, or irony.

- The public continues to prefer beauty and craftsmanship over confusion or provocation.

- Museums and markets frequently inflate the value of Contemporary works through hype.

- A renewal of traditional artistic values is possible through education and principled support.

FAQs

- What’s the difference between Modern and Contemporary Art?

Modern Art spans roughly from the 1860s to 1970s, focusing on innovation with discipline. Contemporary Art includes work from the 1970s to today and is often concept-driven. - Why is Modern Art considered better by many?

It combines emotional depth, technical skill, and aesthetic appeal, making it more accessible and lasting. - Why does Contemporary Art often seem meaningless?

Many contemporary works prioritize shock or political messaging over clarity, craftsmanship, or emotional connection. - Is all Contemporary Art bad?

No, but much of it lacks the depth and skill that defined earlier periods. Some contemporary artists still uphold classical standards. - Can art standards be restored?

Yes—through better education, principled patronage, and a cultural shift back to beauty and truth.