Switzerland, known for its towering Alps and pristine lakes, has long been a cultural crossroads, absorbing and contributing to the rich artistic traditions of Europe. Despite its relatively small size, the country’s unique position at the heart of the continent—bordering France, Germany, Italy, and Austria—has shaped its art in profound ways. Swiss artists have drawn inspiration from these powerful neighbors while cultivating distinct regional identities. More importantly, Switzerland’s historical neutrality, its decentralized political system, and its linguistic diversity have fostered a pluralistic artistic tradition, rather than a single dominant national style.

While many European nations have art histories closely tied to royal courts or state patronage, Switzerland’s art has been largely shaped by religious institutions, wealthy merchant families, and private collectors. The absence of a centralized monarchy meant that different artistic movements flourished in various regions, influenced by both religious divides (Catholic vs. Protestant cantons) and external artistic trends. For example, while the Protestant Reformation suppressed religious iconography in some areas, Catholic regions like Lucerne and Valais continued to commission Baroque and Rococo masterpieces for their churches.

Key Themes in Swiss Art

Throughout its history, Swiss art has revolved around several recurring themes:

- The Swiss Landscape and National Identity

- The towering mountains, rolling valleys, and picturesque lakes of Switzerland have long inspired artists, from Romantic painters like Caspar Wolf to contemporary photographers.

- The Alps, in particular, became central to Swiss national identity, especially during the 18th and 19th centuries when the country’s tourism industry began to flourish.

- Religious and Political Influences

- The Protestant Reformation (spearheaded by figures like Huldrych Zwingli in Zurich and John Calvin in Geneva) led to a shift away from religious imagery in some regions, favoring iconoclasm and minimalism.

- Meanwhile, Catholic cantons continued to support elaborate altarpieces, frescoes, and ecclesiastical architecture, particularly in the Baroque and Rococo periods.

- Swiss Precision and Craftsmanship

- Switzerland’s reputation for meticulous craftsmanship is reflected in its artistic traditions. Whether in the intricate details of Gothic stained glass, Renaissance portraiture, or modernist architecture, Swiss art often emphasizes technical mastery.

- This precision extends beyond painting and sculpture—Switzerland’s expertise in watchmaking and graphic design also plays a role in its artistic identity.

- Avant-Garde and Artistic Innovation

- Switzerland has played a surprising role in the birth of modernist and avant-garde movements. Zurich was the birthplace of Dadaism, a revolutionary anti-art movement that emerged during World War I as a reaction to the horrors of war.

- Swiss artists like Paul Klee (associated with the Bauhaus) and Sophie Taeuber-Arp (a pioneer in Constructivism) helped shape 20th-century abstract and experimental art.

- Switzerland as a Hub for the Global Art Market

- Today, Switzerland is not just home to great artists but also to some of the world’s most prestigious art museums and collections. Institutions like the Kunsthaus Zürich, Kunstmuseum Basel, and Fondation Beyeler hold masterpieces spanning centuries.

- The country is also a key player in the contemporary art world, thanks to Art Basel, one of the most influential art fairs globally, where galleries, collectors, and artists converge to set trends in modern and contemporary art.

A Land of Tradition and Experimentation

The history of Swiss art is one of contrast and coexistence. While the country has a long tradition of Alpine landscapes, religious frescoes, and Renaissance portraiture, it has also been a hotbed of radical artistic experimentation. Switzerland has produced both highly detailed Gothic religious paintings and wildly abstract Dadaist performances. It has given the world both the architectural rigor of Le Corbusier and the playful, kinetic sculptures of Jean Tinguely.

As we explore Swiss art history, we will see how these themes evolve across different eras—from prehistoric carvings to medieval cathedrals, Romantic landscapes, and the cutting-edge conceptual art of today. Switzerland’s story is not just one of mountains and neutrality; it is also a story of artistic innovation, rebellion, and reinvention.

Prehistoric and Ancient Swiss Art

Long before Switzerland became a hub of European culture, its earliest inhabitants left their artistic mark on the landscape. The art of prehistoric Switzerland—stretching from the Paleolithic era to the arrival of the Romans—reflects both the deep spiritual life of its ancient peoples and their connection to the Alpine environment. Though overshadowed by the grand artistic traditions of later centuries, these early works provide a fascinating glimpse into the visual culture of Switzerland’s distant past.

The First Artists: Rock Carvings and Petroglyphs in the Alps

The earliest known art in Switzerland consists of rock carvings (petroglyphs), some of which date back as far as 10,000 BCE. These engravings, found primarily in alpine regions such as Valais, Ticino, and the Engadin, often depict animals, human figures, hunting scenes, and abstract symbols.

One of the most significant sites is Mont Bégo and the Vallée des Merveilles, located in the southwestern Alps near the Swiss border. While most of the carvings lie in present-day France and Italy, similar motifs have been discovered in Swiss alpine passes. These petroglyphs, believed to have been created by early agrarian and hunter-gatherer societies, suggest a ritualistic or communicative function, possibly related to fertility rites or religious beliefs.

The style of these carvings is simple yet evocative, often showing stylized animals such as deer, ibex, and cattle. Some figures appear in motion, their legs and tails elongated to suggest running or jumping—a remarkable early attempt at depicting movement. These motifs are strikingly similar to those found in prehistoric art across Europe, indicating that the early peoples of Switzerland were part of a broader cultural and artistic network.

The Celtic Helvetii and Their Artistic Legacy

By the Iron Age (circa 800–15 BCE), the region that would become Switzerland was inhabited by Celtic tribes, the most famous being the Helvetii. These Celts, known for their warrior culture and skilled craftsmanship, produced a wide array of metalwork, jewelry, and ritual objects that showcase their artistic sophistication.

Celtic Metalwork: Swords, Brooches, and Ritual Objects

Helvetian artisans were particularly skilled in metalworking, producing finely crafted bronze and iron weapons, jewelry, and ceremonial artifacts. Many of these objects have been discovered in burial sites and sacred locations, indicating that they played important roles in both daily life and spiritual practices.

- Swords and Scabbards: Helvetian warriors carried ornately decorated swords with intricate engravings. The La Tène culture (named after the archaeological site in Switzerland where such artifacts were found) is especially famous for its curvilinear designs, featuring swirling, organic shapes that later influenced Celtic art across Europe.

- Fibulae (Brooches): These metal clasps, used to fasten garments, were often adorned with intricate geometric patterns and stylized animal motifs. Some Helvetian fibulae feature zoomorphic designs, with birds or serpents intertwined in elaborate compositions.

- Torcs and Bracelets: The Helvetii, like other Celts, wore torcs—rigid, ring-like necklaces made of twisted metal. These were often reserved for warriors or nobles and were sometimes gilded or encrusted with coral and enamel.

Celtic Symbolism and Religious Imagery

Celtic art was deeply tied to spiritual beliefs. Many objects feature depictions of gods, animals, and abstract motifs that may have had protective or sacred meanings. Unlike the later, more realistic styles of Roman art, Helvetian artistic expression favored symbolism and abstraction, using flowing lines and repeated patterns.

Archaeological finds in Switzerland, such as those from La Tène (Lake Neuchâtel) and the oppidum of Avenches, reveal evidence of ritual deposits—offerings of weapons, jewelry, and other valuables thrown into lakes or buried in the earth. This suggests that the Helvetii engaged in sacrificial art rituals, believing in the sacred power of objects.

Roman Switzerland: The Arrival of Classical Art

By 15 BCE, the Roman Empire had conquered the Helvetii, bringing classical artistic traditions to Switzerland. Roman rule transformed the region’s artistic landscape, introducing new forms of sculpture, mosaic art, fresco painting, and architecture.

Roman Mosaics and Frescoes in Helvetia

The Roman city of Aventicum (modern Avenches), the capital of Roman Switzerland, became a center of artistic production. Here, archaeologists have uncovered elaborate mosaics and frescoes that once adorned the homes of wealthy Roman citizens.

- Mosaics: These were created using tiny colored stones (tesserae) arranged into geometric patterns, mythological scenes, and nature-inspired imagery. A famous mosaic from Orbe-Boscéaz (in Vaud) depicts Roman gods and symbolic animals in vivid detail.

- Frescoes: Inspired by Pompeian wall paintings, Roman homes in Helvetia featured frescoes painted in rich reds, blues, and golds, depicting mythological narratives, landscapes, and architectural trompe-l’œil effects.

Roman Sculpture and Public Art

Swiss archaeological sites have yielded numerous examples of Roman statuary, including busts of emperors, deities, and prominent citizens. Romanized Helvetians commissioned these sculptures to display status and loyalty to Rome. Some statues, such as those of Jupiter and Mars, were likely worshipped in Roman temples built in Switzerland.

Roman Influence on Architecture

Roman Switzerland saw the construction of temples, amphitheaters, and bathhouses, following classical Roman architectural principles. The remains of Aventicum’s amphitheater, one of the largest in Roman Gaul, stand as a testament to this era. Additionally, towns like Augusta Raurica (near Basel) became important Roman settlements, with well-preserved forums, aqueducts, and villas.

The Transition to Early Medieval Art

As the Roman Empire declined in the 5th century CE, Switzerland underwent profound cultural shifts. The influence of Germanic tribes, such as the Burgundians and Alemanni, brought new artistic traditions. This period saw a decline in classical realism and a return to simpler, more abstract forms of expression, paving the way for the medieval art that would define the next era of Swiss history.

Conclusion: A Foundation for Swiss Artistic Identity

Switzerland’s prehistoric and ancient art laid the foundation for its later artistic developments. From the mystical petroglyphs of the Alps to the intricate metalwork of the Helvetii, and the grand mosaics and sculptures of Roman Helvetia, each era added to the country’s visual heritage. These early artistic traditions—both indigenous and imported—set the stage for the medieval, Renaissance, and modernist movements that would follow.

In the next section, we will explore how Medieval Swiss art evolved, focusing on monastic illumination, Romanesque frescoes, and the rise of Gothic cathedrals.

Medieval Swiss Art: Romanesque and Gothic Influences

As Switzerland transitioned from the collapse of the Roman Empire into the medieval period, its artistic landscape was shaped by the growing power of the Church, the establishment of monasteries, and the evolving architectural styles of the Romanesque and Gothic periods. While Switzerland lacked a centralized monarchy to act as a major artistic patron (as seen in France or England), religious institutions played a crucial role in fostering artistic expression.

The Middle Ages in Switzerland saw the creation of illuminated manuscripts, frescoes, stained glass, and monumental church architecture, each reflecting the profound religious devotion of the era. From the austere yet striking Romanesque churches of the 11th and 12th centuries to the soaring elegance of Gothic cathedrals in the 13th and 14th centuries, Swiss medieval art developed in dialogue with wider European trends while maintaining distinctive local characteristics.

The Role of Monasteries in Swiss Medieval Art

In early medieval Switzerland, monasteries were the primary centers of artistic and intellectual life. Benedictine, Cluniac, and later Cistercian monks not only preserved classical knowledge but also created some of the most remarkable artistic works of the period.

Illuminated Manuscripts: The Artistic Treasures of Monastic Scriptoria

One of the most significant contributions of medieval Swiss monasteries to art history was the production of illuminated manuscripts—handwritten books adorned with decorative initials, intricate borders, and religious iconography.

- The Abbey of Saint Gall, founded in the 8th century, became a leading center of manuscript illumination in Europe. Monks there produced exquisitely detailed Gospels, Psalters, and theological texts, often decorated with vibrant pigments, gold leaf, and elaborate calligraphy.

- The Saint Gall Plan (circa 820), though not an illuminated manuscript in the traditional sense, is one of the most famous medieval architectural drawings. Created at Saint Gall, it presents an idealized blueprint for a Benedictine monastery and provides invaluable insight into medieval artistic and architectural thought.

- Another key example is the Evangeliary of Saint Gall, a richly illustrated Gospel book featuring ornate initial letters, classical motifs, and delicate figural representations of biblical scenes.

These manuscripts not only served religious and scholarly functions but also demonstrated the fusion of Carolingian, Ottonian, and later Romanesque artistic styles.

Romanesque Art in Switzerland (11th–12th Century)

As the Middle Ages progressed, Swiss religious art took on the Romanesque style, characterized by thick walls, rounded arches, and bold yet somewhat abstract forms. This style, prevalent from roughly 1000 to 1200, was deeply rooted in the influence of monastic culture and pilgrimage routes.

Romanesque Church Frescoes: A Visual Bible for the Faithful

Fresco painting flourished in Romanesque Switzerland, particularly in the interiors of monasteries and churches. These paintings, covering entire walls and ceilings, served as didactic tools to educate largely illiterate congregations about biblical stories.

- One of the most remarkable examples is found in the Church of Saint Martin in Zillis (Graubünden), famous for its painted wooden ceiling from the early 12th century. This masterpiece consists of 153 vividly colored panels depicting Christ’s life, the Last Judgment, and Old Testament scenes. The figures, rendered in a simplified yet expressive style, reflect the Romanesque tradition of symbolic storytelling over strict realism.

- The Abbey Church of Romainmôtier, one of the oldest monastic sites in Switzerland, features Romanesque frescoes that display a mix of Byzantine and Western influences, highlighting the interconnectedness of Swiss art with broader European trends.

- Other churches, such as those in Müstair (a UNESCO World Heritage Site), showcase large-scale fresco cycles blending Germanic, Byzantine, and Carolingian influences, demonstrating the diversity of Romanesque artistic expression.

Romanesque Sculpture and Stained Glass

Although Swiss Romanesque churches were often more austere than their French or Italian counterparts, they still featured remarkable stone carvings and early stained glass windows.

- Romanesque sculpture in Switzerland was mostly architectural—adorned on church portals, capitals, and cloisters. The Cathedral of Basel (Münster) retains relief carvings on its façade, depicting biblical figures and allegorical scenes.

- Early stained glass examples, though rare, can be found in the Abbey of Saint Urban and other monastic sites, with simple geometric patterns evolving into more narrative imagery in the Gothic period.

By the late 12th century, as Swiss cities grew and religious architecture evolved, Romanesque gave way to Gothic, introducing new forms of light-filled, soaring spaces and increasingly naturalistic artistic expression.

The Gothic Transformation: Swiss Art in the 13th–15th Century

The arrival of Gothic architecture and art in Switzerland during the 13th and 14th centuries marked a shift toward greater verticality, naturalism, and emotional intensity. Swiss Gothic art, though influenced by France and Germany, developed distinct regional characteristics, especially in its cathedrals, stained glass, and panel painting.

The Rise of Swiss Gothic Cathedrals

Unlike the grand Gothic cathedrals of Paris or Cologne, Swiss Gothic churches tended to be more restrained in scale and decoration, reflecting the country’s decentralized political structure and varied religious traditions. Nevertheless, several Gothic cathedrals stand as artistic masterpieces:

- The Lausanne Cathedral (begun in the late 12th century, completed in the 13th) is considered the finest Gothic church in Switzerland. Its stunning rose window, intricate sculptural details, and soaring ribbed vaults illustrate the full elegance of the Gothic style.

- The Basel Münster, originally Romanesque but later expanded with Gothic elements, features detailed portal sculptures and impressive ribbed vaulting.

- The Fraumünster Church in Zurich, while architecturally restrained, is famous for its stained glass windows, including modern works by Marc Chagall, blending medieval and contemporary artistic influences.

Stained Glass and Panel Painting: A New Artistic Flourish

Gothic Switzerland saw an explosion of stained glass artistry, as windows became larger and more intricate. Some of the most breathtaking examples include:

- The stained glass of Lausanne Cathedral, featuring highly detailed biblical narratives and rich color schemes.

- The Kloster Wettingen windows, which show a transition from medieval symbolism to a more lifelike depiction of religious figures.

Panel painting also gained prominence during this period, particularly in altarpieces commissioned for churches and monasteries. Swiss Gothic painting often displayed delicate figures, vibrant colors, and refined detailing, influenced by German and Flemish styles.

Late Medieval Sculpture and the Transition to the Renaissance

Late Gothic Switzerland also produced expressive wooden sculptures, particularly in altarpieces. Artists began experimenting with greater emotional depth and naturalism, setting the stage for the transition into the Swiss Renaissance of the 15th and 16th centuries.

Conclusion: The Foundation for Swiss Artistic Growth

The medieval period was instrumental in shaping Swiss artistic identity, as the country moved from the monastic Romanesque tradition to the grand Gothic cathedrals of the later Middle Ages. While Switzerland never had the grand palaces of France or the vast fresco cycles of Italy, its medieval art remains a testament to its spiritual devotion, craftsmanship, and adaptability to European artistic trends.

As we move into the Renaissance, we will see how Swiss art transformed under humanist influences, giving rise to portraiture, religious reform art, and the first stirrings of modern Swiss artistic identity.

The Renaissance and Reformation in Swiss Art

As the Renaissance swept across Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries, Switzerland found itself at a crossroads. While Italian humanism and artistic advancements made their way north, the Swiss Confederacy was undergoing profound political and religious changes. The rise of the Protestant Reformation, led by figures like Huldrych Zwingli in Zurich and John Calvin in Geneva, deeply impacted artistic production, leading to an ideological shift that diverged from the grand religious commissions of Catholic Europe.

Swiss Renaissance art, therefore, developed in a dual trajectory: on one hand, it embraced the naturalism, perspective, and humanist ideals of the Italian and German Renaissance; on the other, the growing influence of Protestant iconoclasm in the 16th century led to the destruction and rejection of religious imagery in many Swiss cities. This period saw the rise of secular portraiture, detailed altarpieces, and book illustration, as well as a stark contrast between Catholic and Protestant artistic traditions.

The Early Swiss Renaissance: The Influence of Italy and Germany

During the 15th century, Swiss artists were increasingly exposed to the artistic innovations of the Italian Renaissance and the Northern Renaissance. While Switzerland lacked major artistic centers like Florence or Bruges, Swiss painters, sculptors, and architects trained in Italy, Germany, and the Burgundian Netherlands, bringing new techniques back to their homeland.

Hans Holbein the Elder and Late Gothic Transition

One of the most significant early Swiss Renaissance painters was Hans Holbein the Elder (c. 1465–1524). Though he was still influenced by the Late Gothic style, his work demonstrated an increasing interest in realism, perspective, and human expression, key Renaissance characteristics.

- His Altarpiece of the Passion (Augsburg, 1495) shows Swiss Gothic traditions merging with early Renaissance realism.

- He influenced his son, Hans Holbein the Younger, who would become one of the greatest portraitists of the 16th century.

Niklaus Manuel Deutsch: The Shift Toward Humanism

Niklaus Manuel Deutsch (1484–1530), a painter, writer, and political figure, played a crucial role in introducing Renaissance humanism into Swiss art. His paintings, such as The Dance of Death, reflect not only Renaissance stylistic elements but also a growing interest in moral and social commentary—a theme that would become more prominent in Reformation-era art.

Hans Holbein the Younger: The Pinnacle of Swiss Renaissance Art

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497–1543) is Switzerland’s most internationally renowned Renaissance artist. Though he spent much of his career in England, working as court painter to Henry VIII, he was trained in Basel, where his early works reflect both Germanic realism and Italian Renaissance influences.

Holbein’s Mastery in Portraiture

Holbein revolutionized portrait painting with his attention to minute detail, psychological depth, and mastery of light and shadow. His portraits, often imbued with symbolic elements, capture the intellectual spirit of the Renaissance.

- Portrait of Erasmus of Rotterdam (1523) – A strikingly lifelike image of the Dutch humanist, reflecting Erasmus’ intellectualism and refinement.

- The Ambassadors (1533) – Though painted in England, this masterpiece features Swiss artistic precision combined with Renaissance symbolism, including the famous anamorphic skull (a distorted image that reveals itself when viewed from a particular angle).

Holbein’s ability to create realistic, three-dimensional figures, combined with his mastery of oil painting techniques, set him apart as the most important Swiss artist of the Renaissance.

The Protestant Reformation and Swiss Art (1520s–1600s)

While the Renaissance flourished in Catholic Europe, the Swiss Reformation (beginning in 1519) radically transformed the country’s artistic landscape. Protestant leaders, particularly Huldrych Zwingli in Zurich and John Calvin in Geneva, rejected religious imagery, viewing it as idolatrous. This led to the destruction of religious paintings, sculptures, and stained glass in Protestant regions.

Iconoclasm and the Destruction of Religious Art

During the 1520s–1530s, Protestant iconoclasts removed or destroyed Catholic religious imagery in churches across Zurich, Bern, and Geneva. This had a profound effect on Swiss art:

- Altarpieces were dismantled, statues were smashed, and frescoes were whitewashed.

- In Zurich and Basel, churches became stark and minimalist, reflecting the Protestant emphasis on scripture over visual representation.

- Many artists, once reliant on religious commissions, had to adapt by focusing on portraiture, landscapes, and printmaking.

Portraiture and Secular Art in Protestant Switzerland

With the decline of religious commissions, secular portraiture flourished in Protestant areas. Wealthy merchants, reformers, and scholars commissioned portraits to display status and intellect rather than religious devotion.

- Portrait of Huldrych Zwingli (Hans Asper, c. 1531) – A stark, serious depiction of the Swiss reformer, emphasizing his theological rigor.

- Felix and Regula Martyrdom Scenes – Protestant artists depicted biblical and historical figures in more didactic, restrained compositions.

The Role of Printmaking: Spreading Protestant Ideas

As religious imagery declined in Protestant areas, printmaking flourished as a means of disseminating Reformation ideals.

- Woodcuts and engravings became popular, often depicting moralizing themes or biblical scenes without Catholic iconography.

- Swiss printmakers played a crucial role in spreading Protestant propaganda, producing illustrated Bibles and theological treatises.

Catholic Swiss Art: The Persistence of Religious Imagery

While Protestant regions purged religious art, Catholic cantons such as Lucerne, Fribourg, and Valais continued commissioning elaborate religious works. Counter-Reformation art, designed to inspire devotion, led to the creation of new altarpieces, frescoes, and sculptures.

- Baroque influences began appearing in Swiss Catholic art, particularly in church interiors, which remained richly decorated.

- Painters like Tobias Stimmer (1539–1584) blended Renaissance realism with Catholic devotional themes.

Swiss Renaissance Architecture

Swiss Renaissance architecture reflected both Italian classical ideals and local traditions.

- Zurich’s Rathaus (Town Hall, 1698) – A blend of Renaissance symmetry with Swiss functionalism.

- Castles and civic buildings adopted Renaissance proportions but retained elements of medieval fortification.

Conclusion: The Diverging Paths of Swiss Art

The Swiss Renaissance was a period of both artistic flourishing and destruction. While Swiss artists like Holbein reached new heights in realism and humanism, the Reformation fractured the artistic landscape, leading to a stark contrast between Protestant minimalism and Catholic grandeur.

This era set the stage for Swiss Baroque and Rococo art, where Catholic regions embraced opulent decoration while Protestant cantons favored restrained elegance.

Baroque and Rococo Swiss Art

As the Renaissance gave way to the dramatic, emotionally charged style of the Baroque period (17th century) and the ornate elegance of the Rococo movement (18th century), Switzerland’s artistic landscape reflected the religious and cultural divisions that had taken root during the Reformation. In Catholic cantons, Baroque art flourished, characterized by grand church interiors, expressive paintings, and theatrical sculptures aimed at inspiring religious devotion. Meanwhile, Protestant regions, particularly Zurich, Basel, and Geneva, remained committed to more austere and restrained artistic expressions, leading to a unique contrast in Swiss Baroque aesthetics.

At the same time, Switzerland’s position as a hub of trade, diplomacy, and finance brought French, Italian, and German influences into its artistic production. Swiss artists, architects, and sculptors contributed to the development of European Baroque and Rococo while maintaining a distinctly Swiss sensibility—combining grandeur with precision, devotion with craftsmanship.

The Catholic Splendor of Swiss Baroque Art

In Catholic cantons such as Lucerne, Valais, Fribourg, and parts of Graubünden, the Counter-Reformation (a Catholic response to Protestantism) encouraged the creation of spectacular Baroque churches and religious art. The aim was to overwhelm the senses and inspire faith through light, movement, and dramatic compositions.

Swiss Baroque Church Architecture: Monumental and Theatrical

Baroque architecture in Switzerland followed Italian and German models, particularly inspired by the grandeur of Jesuit churches and the dramatic spatial effects of Italian Baroque masters like Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

- The Jesuit Church of Lucerne (1666–1677) is Switzerland’s first fully Baroque church, reflecting the grandeur of Roman Counter-Reformation architecture. Its stuccoed vaults, gilded altars, and illusionistic ceiling frescoes set a precedent for Swiss Baroque ecclesiastical design.

- Einsiedeln Abbey, a major pilgrimage site, was remodeled in the 18th century with elaborate Baroque decoration, including richly painted ceilings and intricate stucco work.

- The Abbey of Saint Urban (18th century) features a grand Baroque façade and an interior filled with lavish stuccoes and frescoes, making it a masterpiece of Swiss Baroque monastic architecture.

Baroque Painting in Switzerland: Drama and Devotion

Swiss Baroque painting, particularly in Catholic areas, emphasized religious ecstasy, dramatic lighting, and lifelike movement.

- Michael Willmann (1630–1706), though active mainly in Silesia, had Swiss ties and painted powerful biblical scenes reminiscent of Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro technique.

- Franz Carl Stauder (1691–1756) created expressive altarpieces and religious compositions, filled with swirling clouds, angelic figures, and deep emotional intensity.

Baroque painters in Switzerland often worked on fresco cycles, covering church ceilings with theatrical depictions of biblical narratives, reinforcing Catholic doctrine in the face of Protestant iconoclasm.

Swiss Baroque Sculpture: Theatrical Realism

Baroque Swiss sculpture, especially in Catholic regions, took inspiration from German and Italian Baroque traditions, emphasizing movement and theatricality.

- The High Altar of the Monastery of Einsiedeln, featuring elaborate gilded carvings and lifelike figures of saints, reflects the Baroque passion for dynamic composition.

- Johann Baptist Babel (1716–1799), the leading Swiss Baroque sculptor, created grand religious statues with expressive faces, flowing drapery, and intense realism, bridging the Baroque and Rococo periods.

Protestant Baroque: Austerity and Simplicity

In contrast to Catholic Baroque extravagance, Swiss Protestant regions maintained a restrained approach to art and architecture. The emphasis was on craftsmanship, symmetry, and functionality, avoiding religious imagery in favor of elegant yet understated design.

Protestant Church Architecture: Classical Restraint

- The Cathedral of Geneva, originally Gothic, underwent renovations in the Baroque period that stripped it of elaborate ornamentation, in line with Calvinist principles.

- Zurich’s Grossmünster, while retaining its medieval structure, adopted a more austere, neoclassical interior, reflecting the Protestant preference for unadorned sacred spaces.

- Basel’s Town Hall (Rathaus), expanded in the early 17th century, features Renaissance-Baroque fusion, with colorful murals but without excessive religious imagery.

Protestant Artistic Traditions: Portraiture and Still Life

Since large-scale religious art was discouraged, Swiss Baroque painting in Protestant regions focused on portraiture, still life, and allegorical themes.

- Johann Rudolf Huber (1668–1748) became one of the most sought-after portrait painters, capturing the wealth and power of Swiss burghers, bankers, and scholars. His work demonstrated Baroque realism, but without excessive ornamentation.

- Still life painting, influenced by Dutch and Flemish Baroque artists, became popular in Protestant areas. These works often carried moralistic themes, emphasizing the fleeting nature of life (Vanitas paintings).

The Rococo Period (18th Century): Elegance and Ornamentation

By the early 18th century, Baroque art in Switzerland softened into the Rococo style, which favored delicate ornamentation, pastel colors, and playful, light-hearted themes. While Rococo flourished in France and Bavaria, Switzerland adapted it in a more subtle and refined manner.

Swiss Rococo Architecture: Playful Yet Restrained

- The Benedictine Convent of Saint Urban (mid-18th century) features Rococo stuccoes and delicate frescoes, balancing Baroque grandeur with Rococo lightness.

- The Porrentruy Jesuit College, with its elegantly curved facades and decorative details, exemplifies Swiss Rococo civic architecture.

Rococo Painting and Decorative Arts

Swiss Rococo painters often worked in fresco decoration and portraiture, blending the elegance of French Rococo with Swiss craftsmanship.

- Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702–1789), one of Switzerland’s most celebrated Rococo artists, was known for his exquisite pastel portraits, capturing the refinement of European aristocracy. His delicate use of color and texture epitomized the Rococo aesthetic.

- Swiss artisans produced intricately carved furniture, clocks, and textiles, reflecting the ornamental elegance of Rococo design.

The End of the Baroque and Rococo Era: Shifting Toward Neoclassicism

By the late 18th century, the exuberance of Baroque and Rococo began to wane as Neoclassicism emerged. Inspired by Ancient Roman ideals, Neoclassical art favored clarity, order, and restraint, marking a shift away from the lavish excesses of previous centuries.

Conclusion: A Period of Contrast and Coexistence

The Baroque and Rococo period in Switzerland was deeply shaped by religious divisions. While Catholic cantons embraced the grandeur of Baroque churches and the lightness of Rococo decoration, Protestant regions favored austerity, focusing on portraiture, architecture, and craftsmanship.

This dual artistic trajectory laid the groundwork for the 19th-century movements of Romanticism and Realism, where Swiss artists would turn their attention to national identity, Alpine landscapes, and social themes.

Swiss Art in the 18th and 19th Century: Romanticism and Realism

As the 18th century gave way to the 19th, Swiss art underwent a profound transformation. The Age of Enlightenment introduced new ideas about nature, reason, and individualism, setting the stage for the rise of Romanticism—a movement that celebrated emotion, imagination, and the sublime power of nature. Switzerland, with its dramatic Alpine landscapes, became an ideal subject for Romantic painters who sought to capture both the beauty and the terror of the natural world.

By the mid-19th century, however, Romantic idealism gave way to Realism, a movement that focused on everyday life, social themes, and objective depictions of the world. Swiss artists began to explore the realities of rural labor, urbanization, and political change, reflecting the profound societal shifts taking place in the country.

This period saw the emergence of some of Switzerland’s most important painters, including Caspar Wolf, Alexandre Calame, and Albert Anker, who helped define both Romantic and Realist aesthetics in Swiss art.

Romanticism in Swiss Art (Late 18th–Mid 19th Century)

Romanticism, which flourished between 1780 and 1850, was deeply influenced by the philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who idealized the natural world and the simplicity of rural life. Swiss artists embraced these ideas, producing works that emphasized dramatic landscapes, heroic figures, and emotional intensity.

The Swiss Alps as a Romantic Symbol

The Alps became a central motif in Romantic painting, embodying both the sublime (awe-inspiring, terrifying nature) and national identity. Swiss artists played a key role in shaping the mythos of the Alps, which would later influence Swiss tourism and cultural identity.

- Caspar Wolf (1735–1783) was one of the first Swiss painters to depict the Alps with scientific accuracy and emotional grandeur. His works, such as “The Lower Grindelwald Glacier” (1774), capture the vastness and untamed power of Swiss nature, foreshadowing later Romantic landscapes.

- Alexandre Calame (1810–1864) became Switzerland’s most famous Romantic landscape painter. His dramatic mountain scenes, such as “The Lake of the Four Cantons” (1852), convey the majesty and isolation of the Swiss wilderness. Calame’s paintings were widely collected in France, Germany, and Britain, helping to popularize Swiss landscapes across Europe.

- François Diday (1802–1877), another leading Romantic landscape painter, was known for his detailed renderings of Alpine waterfalls, glaciers, and lakes, often bathed in dramatic lighting.

Romanticism in Swiss Portraiture and History Painting

While landscapes dominated Swiss Romanticism, portraiture and historical painting also flourished.

- Karl Georg Lory (1798–1846) created heroic depictions of Swiss national history, celebrating events such as the Battle of Morgarten and the exploits of William Tell.

- Firmin Massot (1766–1849) painted elegant portraits that reflected Romantic ideals of individuality and introspection. His subjects, often intellectuals and artists, were depicted with an air of sensitivity and poetic melancholy.

Realism in Swiss Art (Mid–Late 19th Century)

By the 1850s, Romanticism’s emphasis on emotion and the sublime began to fade, replaced by Realism—a movement that sought to depict life as it truly was, without idealization. Swiss Realist painters focused on rural scenes, working-class subjects, and the quiet dignity of everyday life.

Albert Anker: The Painter of Swiss Peasant Life

- Albert Anker (1831–1910) became the most beloved Swiss Realist painter, known for his tender, meticulously detailed depictions of rural life.

- His paintings, such as “Schoolboy Writing” (1874) and “The Village Teacher” (1896), portray Swiss village life with warmth, honesty, and social realism.

- Anker’s work reflected Swiss national identity, emphasizing simplicity, tradition, and family values in a rapidly modernizing world.

Ferdinand Hodler and the Shift Toward Symbolism

Although initially a Realist painter, Ferdinand Hodler (1853–1918) gradually transitioned toward Symbolism, blending bold colors, simplified forms, and allegorical themes.

- His early works, such as “The Woodcutter” (1885), align with Realist themes of labor and hardship, but his later works, like “The Night” (1890), introduce dreamlike, symbolic elements.

- Hodler became one of Switzerland’s most influential painters, bridging Realism, Symbolism, and early Modernism.

Swiss Realism in Urban and Social Themes

While much of Swiss Realism focused on rural life, some artists turned their attention to industrialization, urbanization, and social change.

- Rodolphe Théophile Bosshard (1889–1960) depicted Swiss workers, factories, and the effects of modernization with a sharp, observational eye.

- Adolf Dietrich (1877–1957) painted Swiss villages and small-town life, capturing the tension between tradition and modernity.

The Influence of Photography on Swiss Art

The invention of photography in the 19th century had a profound impact on Swiss art, influencing Realist painters and shaping new artistic trends.

- Early Swiss photographers, such as Eduard Spelterini, documented Alpine landscapes from the air, creating breathtaking panoramic images.

- Realist painters increasingly used photographs as references, enhancing their ability to capture minute details and lifelike compositions.

The Transition to Modernism

By the late 19th century, Swiss art was moving beyond strict Realism, incorporating Symbolist, Impressionist, and Expressionist influences. The works of Hodler, Giovanni Giacometti, and Cuno Amiet signaled the beginning of Swiss Modernism, which would fully emerge in the 20th century.

Conclusion: From Romantic Majesty to Realist Truth

The 18th and 19th centuries saw a dramatic evolution in Swiss art, from the sublime landscapes of Romanticism to the honest depictions of everyday life in Realism. These movements helped shape Switzerland’s national identity, emphasizing both the beauty of the Alpine landscape and the resilience of its people.

As Swiss art entered the 20th century, it would embrace abstraction, avant-garde movements, and modernist experimentation, setting the stage for the next chapter in Swiss artistic history.

Swiss Art in the Early 20th Century: Modernism and the Avant-Garde

As the 20th century dawned, Swiss art underwent radical transformations, mirroring the upheavals and innovations of the modern world. The rigid realism of the 19th century gave way to abstraction, bold color experiments, and revolutionary artistic movements that challenged traditional aesthetics.

Switzerland, a country known for its political neutrality, became a haven for avant-garde artists fleeing the turmoil of World War I. Zurich, in particular, played a pivotal role in the emergence of Dadaism, one of the most radical artistic movements of the 20th century. Meanwhile, Swiss painters like Ferdinand Hodler, Paul Klee, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp helped shape international modernist trends, from Expressionism and Cubism to Constructivism and Surrealism.

Despite its reputation for conservatism, Switzerland became a key center for modernist experimentation, laying the foundation for Bauhaus, kinetic art, and conceptual movements that would define later decades.

The Late Work of Ferdinand Hodler: Bridging Realism and Abstraction

Although Ferdinand Hodler (1853–1918) began his career as a Realist painter, his later works transitioned into Symbolism and Expressionism, making him a central figure in Swiss modernism.

- Hodler’s “Parallelism”: His personal theory of art emphasized symmetry, repetition, and simplified forms, seen in works like “The Night” (1890) and “Emotion” (1905).

- His paintings of the Swiss Alps and Lake Geneva became more abstract and decorative, paving the way for Swiss modernist landscape painting.

- Towards the end of his life, his brushstrokes became looser and more expressive, influencing younger Swiss painters like Giovanni Giacometti and Cuno Amiet.

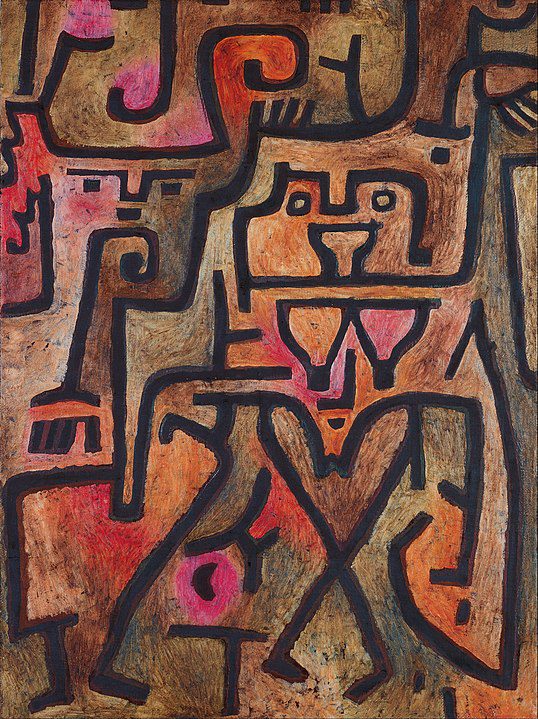

Paul Klee: A Swiss Master of Abstraction

Paul Klee (1879–1940) is one of the most internationally renowned Swiss artists of the 20th century. Though he spent much of his career in Germany at the Bauhaus, his Swiss heritage deeply influenced his artistic sensibilities.

- Klee’s style defies categorization—his work blends Expressionism, Cubism, and Surrealism with a unique, childlike playfulness.

- His color theory, inspired by Johannes Itten and Wassily Kandinsky, became a foundation for modern abstraction.

- Works like “Senecio” (1922) and “Twittering Machine” (1922) showcase his fascination with geometric shapes, vibrant colors, and dreamlike imagery.

Klee’s legacy cemented Switzerland’s role as a hub of modernist intellectualism, influencing both European and American abstractionists.

Dadaism: Switzerland as the Birthplace of the Avant-Garde

One of the most disruptive and revolutionary artistic movements of the 20th century—Dadaism—was born in Zurich in 1916. Amid the horrors of World War I, a group of exiled artists and intellectuals gathered at Cabaret Voltaire, rejecting traditional art in favor of absurdity, randomness, and anti-war protest.

Key Figures of Swiss Dadaism

- Hugo Ball: A German-Swiss writer and performance artist who founded Cabaret Voltaire. His sound poetry performances, where nonsense syllables replaced language, challenged the rationality of war and politics.

- Tristan Tzara: The movement’s main theorist, Tzara’s Dada Manifesto (1918) became a blueprint for anti-art movements.

- Hans Arp (Jean Arp): A Swiss-French sculptor and painter, Arp created biomorphic abstract compositions, rejecting rigid artistic rules. His collages made from torn paper represented a radical break from tradition.

- Sophie Taeuber-Arp: One of the few female pioneers of modernist abstraction, Sophie Taeuber-Arp combined textiles, dance, and Constructivist principles to redefine Swiss art. Her geometric compositions and marionettes became iconic symbols of early modernism.

Dada’s influence spread far beyond Zurich, influencing later avant-garde movements like Surrealism, Fluxus, and Conceptual Art.

Constructivism and the Rise of Geometric Abstraction

Following Dada, Swiss artists embraced Constructivism and the Bauhaus approach, emphasizing mathematical precision, geometric abstraction, and functional design.

- Max Bill (1908–1994), a Bauhaus-trained artist, became a leader in Concrete Art, an offshoot of Constructivism that aimed for pure abstraction through geometry and proportion. His works, such as “Tripartite Unity” (1948), embody Swiss modernist precision.

- Richard Paul Lohse (1902–1988) and Camille Graeser (1892–1980) pushed Swiss art further into systematic, grid-based abstraction, influencing international Minimalist and Op-Art movements.

This geometric, rationalist approach became a defining feature of Swiss design and visual culture, influencing everything from typography to industrial design.

Surrealism and the Swiss Connection

While Switzerland wasn’t a major center for Surrealism, Swiss artists played an essential role in the movement’s development.

- Meret Oppenheim (1913–1985), the most famous Swiss Surrealist, created the iconic “Object (Le Déjeuner en fourrure)” (1936)—a fur-covered teacup that became a symbol of Freudian dream logic and gender critique.

- Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966), while better known for his later existentialist sculptures, experimented with Surrealist painting and design in the 1920s, collaborating with André Breton.

- Kurt Seligmann (1900–1962), a Swiss-born Surrealist, developed fantastical imagery featuring mythological and alchemical themes, influencing American Surrealists after he emigrated.

Swiss Graphic Design and the Bauhaus Legacy

During the early 20th century, Switzerland also became a world leader in graphic design and visual communication. The Bauhaus-inspired Swiss Style (or International Typographic Style) revolutionized advertising, corporate branding, and typography.

- Josef Müller-Brockmann (1914–1996) developed grid-based design, influencing modern corporate identity.

- Armin Hofmann (b. 1920) created minimalist posters that emphasized typography and pure composition, setting the standard for global visual culture.

This Swiss modernist approach remains influential today, shaping everything from Google’s UI design to contemporary branding strategies.

The Influence of World War II on Swiss Art

While Switzerland remained neutral during World War II, the conflict deeply impacted Swiss artists. The war led to:

- Increased artistic isolation, forcing Swiss artists to develop self-contained movements.

- A rise in political poster art, as Switzerland used visual propaganda to promote national unity.

- A shift toward Existentialist themes, seen in the later works of Alberto Giacometti, whose elongated, fragile sculptures reflected postwar alienation and uncertainty.

Conclusion: Switzerland’s Role in the Birth of Modern Art

The early 20th century established Switzerland as a center for modernist innovation, from the birth of Dadaism in Zurich to the emergence of geometric abstraction and Constructivism. Swiss artists not only participated in international movements but often led them, shaping the future of contemporary art, design, and visual culture.

As Swiss art moved into the postwar period, new movements like Kinetic Art, Minimalism, and Conceptual Art would emerge, further solidifying Switzerland’s reputation as a pioneering force in global art history.

Swiss Art During and After World War II: Abstraction, Kinetic Art, and the Postwar Avant-Garde

As the world plunged into World War II, Switzerland maintained its stance of neutrality. However, while the country was spared from direct destruction, the war profoundly impacted its artistic landscape. Swiss artists responded to the anxieties and upheavals of the time in diverse ways—some retreated into pure abstraction, seeking order amid chaos, while others engaged with themes of existentialism, alienation, and political critique.

The postwar period saw Switzerland emerge as a major center for avant-garde movements, particularly in the fields of abstraction, kinetic art, and conceptual experimentation. Artists such as Max Bill, Jean Tinguely, and Alberto Giacometti helped redefine the boundaries of modern art, while Swiss graphic design and typography became the global standard for visual communication.

This period marked Switzerland’s transition from a refuge for wartime exiles to a leader in the international art scene, blending scientific precision with playful innovation in ways that continue to influence contemporary art today.

Swiss Art During World War II: Isolation and Existentialism

Although Switzerland remained politically neutral, the war deeply affected its artistic community. The rise of Fascism in Germany and Italy forced many artists to flee to Switzerland, turning cities like Zurich, Basel, and Geneva into safe havens for modernist experimentation.

Alberto Giacometti: Existentialist Sculpture and the Postwar Condition

No Swiss artist captured the existential weight of the 20th century quite like Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966). Though active in Paris, the war years forced him back to Switzerland, where his work took on a raw, skeletal quality that would define his legacy.

- His postwar sculptures, such as “L’Homme qui marche” (Walking Man, 1960) and “La Cage” (1950), depict elongated, fragile human figures, emphasizing themes of isolation, resilience, and alienation.

- Influenced by Sartre’s Existentialism, Giacometti’s figures seem trapped in space, embodying the disorientation of the postwar world.

- His unique, rough-textured approach became one of the most recognizable sculptural styles of the 20th century, influencing countless artists in Europe and the United States.

Political Art and Swiss War Posters

While Swiss artists rarely engaged directly with political propaganda, Swiss poster design flourished during WWII, shaping how the nation presented itself both domestically and internationally.

- Posters emphasized national unity, neutrality, and resistance to external forces, often using bold graphics and minimalism—a precursor to Swiss modernist design.

- Hans Erni (1909–2015), a Swiss painter and designer, created politically charged murals and posters, often incorporating Surrealist and Cubist influences to critique war and nationalism.

Postwar Swiss Art: The Rise of Abstraction and Concrete Art

Following the devastation of WWII, many Swiss artists rejected figurative art in favor of geometric abstraction, order, and clarity. This movement—known as Concrete Art—was pioneered by Swiss modernists such as Max Bill, Richard Paul Lohse, and Camille Graeser.

Max Bill: The Architect of Swiss Modernism

Max Bill (1908–1994) was a Bauhaus-trained Swiss artist, architect, and designer who became the leading figure in Concrete Art, a style based on mathematical precision and geometric purity.

- His sculptures, paintings, and industrial designs focused on harmonic proportions, influenced by Bauhaus theories.

- Works like “Endless Ribbon” (1947) exemplify his interest in infinity, continuity, and abstract form.

- As a teacher at the Zurich School of Arts and Crafts, Bill helped shape Swiss modernist design, influencing everything from architecture to typography.

Richard Paul Lohse and Camille Graeser: The Swiss Grid System

Alongside Max Bill, artists like Richard Paul Lohse (1902–1988) and Camille Graeser (1892–1980) developed Swiss-style geometric abstraction, often based on precise color fields and modular structures.

- Lohse’s grid-based paintings influenced graphic design, corporate branding, and architectural aesthetics.

- Graeser combined geometric rigor with vibrant color theory, paving the way for Minimalism and Op Art in the 1960s.

The Swiss preference for structure, order, and clarity became a defining feature of global modernism, particularly in architecture and design.

Jean Tinguely and Kinetic Art: Playfulness Meets Technology

One of the most radical and playful postwar Swiss artists was Jean Tinguely (1925–1991), a pioneer of Kinetic Art—a movement that incorporated movement, mechanics, and chance into artistic creation.

- Tinguely’s self-destructive machines, such as “Homage to New York” (1960), challenged the notion of permanence in art, embracing chaos and randomness.

- His welding-based sculptures fused engineering with Dadaist absurdity, reflecting Switzerland’s dual identity as both precise and rebellious.

- The Tinguely Museum in Basel remains a major center for interactive, kinetic, and mechanical art.

Tinguely’s work blurred the line between art and technology, influencing later generations of media artists, cybernetic sculptures, and conceptual designers.

The Emergence of Conceptual and Minimalist Swiss Art

By the 1960s and 70s, Swiss artists increasingly engaged with Conceptual Art, Minimalism, and environmental themes.

Dieter Roth: Experimental Art and Unconventional Materials

Dieter Roth (1930–1998) broke all artistic conventions by using decaying materials (cheese, chocolate, and organic matter) to explore ephemerality and decomposition.

- His “Literaturwurst” (1961) series, in which he turned books into sausages, was a critique of mass production and the art market.

- Roth’s edible sculptures introduced ideas of impermanence and entropy, which became key themes in postmodern art.

Swiss Minimalism and Conceptualism

- Roman Signer (b. 1938) used performance and ephemeral installations to explore the effects of time, movement, and destruction.

- Not Vital (b. 1948) combined Swiss minimalism with global influences, creating sculptural landscapes and architectural interventions.

Swiss Graphic Design: The Global Influence of the Swiss Style

Perhaps Switzerland’s most enduring postwar artistic contribution was in graphic design and typography.

- The Swiss International Typographic Style (1950s–70s), pioneered by Josef Müller-Brockmann and Armin Hofmann, revolutionized advertising, corporate branding, and editorial layouts.

- The invention of Helvetica (1957) by Max Miedinger became a defining typeface of the modern era, used in NASA, Apple, and the New York subway system.

Swiss design principles—clarity, simplicity, and function—became the standard for global visual communication.

Conclusion: Switzerland as a Global Art and Design Powerhouse

The postwar period saw Switzerland emerge as a leader in modernist abstraction, kinetic art, and conceptual design. Artists like Max Bill, Jean Tinguely, and Alberto Giacometti redefined sculpture, painting, and interactive art, while Swiss typography and design shaped the modern corporate aesthetic.

As the late 20th century approached, Swiss art would move toward video art, multimedia installations, and contemporary conceptual practices, setting the stage for today’s dynamic Swiss contemporary art scene.

Swiss Contemporary Art: Innovation and Global Influence

As Switzerland moved into the late 20th and early 21st centuries, its art scene continued to evolve, embracing conceptualism, new media, installation art, and global influences. While Swiss artists have maintained a strong connection to precision, abstraction, and craftsmanship, they have also pushed boundaries, engaging with political, social, and technological themes.

Switzerland has become a key player in the global contemporary art world, with institutions like Art Basel shaping market trends and artists like Pipilotti Rist, Thomas Hirschhorn, and Urs Fischer redefining the limits of artistic expression. This period marks a shift from the rigid structures of modernism to more experimental, interactive, and socially engaged art forms.

The Rise of Video and Digital Art: Pipilotti Rist

One of the most internationally celebrated Swiss contemporary artists is Pipilotti Rist (b. 1962), a pioneer of video and multimedia installations. Her work combines dreamlike imagery, feminism, and sensory experiences, often immersing viewers in vivid, color-saturated environments.

- Her breakthrough work, “I’m Not the Girl Who Misses Much” (1986), a heavily distorted video piece, critiques gender roles and mass media.

- “Ever is Over All” (1997), featuring a woman joyfully smashing car windows with a flower, became a landmark feminist artwork and was referenced in Beyoncé’s “Lemonade” visual album.

- Rist’s large-scale video installations, such as “Pixel Forest” (2016), transform exhibition spaces into immersive, sensorial experiences, bridging the gap between cinema, painting, and performance.

Her work has been exhibited at MoMA, the Venice Biennale, and major museums worldwide, making her a key figure in Swiss contemporary media art.

Swiss Conceptual and Political Art: Thomas Hirschhorn

Swiss contemporary art has also engaged with political activism, social critique, and conceptualism. One of the most provocative artists in this realm is Thomas Hirschhorn (b. 1957).

- His installations, often made from cheap, everyday materials like cardboard, foil, and duct tape, critique consumer culture, war, and media manipulation.

- “Gramsci Monument” (2013), a tribute to the Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci, was an interactive social experiment in a New York housing project, blending art, politics, and community engagement.

- Hirschhorn’s work is deliberately messy, confrontational, and ephemeral, challenging traditional notions of beauty and permanence in art.

By blurring the lines between art and activism, Hirschhorn has established himself as one of Switzerland’s most politically engaged contemporary artists.

Urs Fischer: Playfulness and Destruction in Contemporary Swiss Sculpture

Swiss contemporary sculpture has been transformed by the work of Urs Fischer (b. 1973), known for his whimsical yet unsettling large-scale installations.

- His “Untitled” (2007), a life-sized wax sculpture of a man slowly melting like a candle, explores impermanence and transformation.

- “Big Clay #4” (2013), a massive, seemingly unfinished clay form cast in aluminum, challenges ideas of scale and materiality.

- Fischer’s work is often humorous, surreal, and unpredictable, engaging with themes of decay, absurdity, and imperfection.

By combining traditional sculptural techniques with unconventional materials, Fischer has become a key figure in global contemporary art, with exhibitions at the Venice Biennale, the Guggenheim, and major galleries worldwide.

Swiss Installation and Environmental Art

Switzerland’s natural landscapes have inspired contemporary artists to engage with environmental themes and site-specific art.

- Roman Signer (b. 1938) creates ephemeral sculptures and time-based installations, often involving explosions, kinetic movement, and natural elements. His works are playful yet deeply philosophical, exploring chance, impermanence, and the passage of time.

- Not Vital (b. 1948) combines architecture and sculpture, creating large-scale land art projects in remote locations, including the Swiss Alps and the Sahara Desert.

These artists reflect a growing interest in Swiss contemporary art that interacts with space, nature, and environmental concerns.

Art Basel: Switzerland’s Global Influence in the Art Market

While Swiss contemporary artists have made their mark on the global art scene, Switzerland itself has also become a key center for art commerce and exhibition.

- Art Basel, founded in 1970, is now the world’s most prestigious contemporary art fair, attracting galleries, collectors, and institutions from around the globe.

- The Fondation Beyeler (Basel), Kunsthaus Zürich, and Kunstmuseum Basel continue to shape Swiss and international contemporary art discourse.

Switzerland’s role in the art economy has solidified its position as one of the most influential cultural hubs in the world.

Conclusion: The Future of Swiss Contemporary Art

Swiss contemporary art stands at the intersection of tradition and innovation, craftsmanship and experimentation. From Pipilotti Rist’s video dreamscapes to Thomas Hirschhorn’s political interventions and Urs Fischer’s melting sculptures, Swiss artists continue to push boundaries and challenge perceptions.

As technology, environmental concerns, and global politics evolve, Switzerland remains a leader in conceptual, multimedia, and experimental art, ensuring that its artistic legacy continues to shape the future.

Swiss Architecture: From Medieval Castles to Modernist Marvels

Swiss architecture, like its art, reflects the country’s unique blend of tradition and innovation. From the stone fortresses of the Middle Ages to the sleek, functionalist designs of modernist pioneers like Le Corbusier, Switzerland has played a crucial role in shaping European architectural history. Today, Swiss architecture is internationally renowned for its precision, sustainability, and avant-garde experimentation, with firms like Herzog & de Meuron and Peter Zumthor leading the way.

This section explores the evolution of Swiss architecture, from Gothic cathedrals and Baroque monasteries to Bauhaus-inspired minimalism and cutting-edge contemporary design.

Medieval Swiss Architecture: Castles, Cathedrals, and Fortifications

During the Middle Ages (10th–15th century), Swiss architecture was dominated by castles, Romanesque churches, and Gothic cathedrals. These structures were built for defense, worship, and civic life, reflecting the country’s fragmented political landscape.

Castles and Fortresses

Switzerland’s mountainous geography made it ideal for fortified castles and strongholds, many of which remain well-preserved today.

- Chillon Castle (12th century, Lake Geneva) – One of Switzerland’s most iconic castles, Chillon features Romanesque arches, Gothic frescoes, and a dramatic lakeside setting. It inspired writers like Lord Byron, who immortalized it in his poem The Prisoner of Chillon.

- Castles of Bellinzona (Ticino, 13th–15th century) – This UNESCO-listed fortress system, built by the Dukes of Milan, showcases the military engineering of the Middle Ages, protecting key Alpine passes.

Romanesque and Gothic Churches

Swiss medieval churches followed the major European styles of Romanesque (thick walls, rounded arches) and Gothic (stained glass, pointed arches, ribbed vaults).

- Lausanne Cathedral (12th–13th century) – One of the finest Gothic structures in Switzerland, featuring elaborate sculptures, flying buttresses, and a stunning rose window.

- Basel Minster (11th–15th century) – Originally Romanesque, it was later expanded with Gothic elements, creating a unique blend of styles.

Renaissance and Baroque Swiss Architecture (16th–18th Century)

The Renaissance and Baroque periods brought new artistic flourishes to Swiss architecture, especially in Catholic regions, where elaborate church designs flourished.

- Einsiedeln Abbey (18th century) – A masterpiece of Swiss Baroque architecture, featuring opulent frescoes, gilded interiors, and an awe-inspiring dome.

- The Jesuit Church in Lucerne (1666–1677) – The first large Baroque church in Switzerland, reflecting the Counter-Reformation’s emphasis on grandeur and emotional impact.

In Protestant regions, architecture remained simpler and more functional, favoring clean lines and classical proportions.

- Zurich Town Hall (1698) – A restrained yet elegant Renaissance-Baroque fusion, reflecting Protestant civic values.

19th-Century Swiss Architecture: Romanticism and National Identity

The 19th century saw a revival of medieval architectural styles, particularly Neo-Gothic and Neo-Romanesque designs, often used for public buildings and train stations.

- Federal Palace (Bundeshaus, Bern, 1857–1902) – The seat of the Swiss government blends Neo-Renaissance and Neo-Baroque elements, symbolizing Swiss national unity.

- Zurich Hauptbahnhof (1871) – One of Switzerland’s grandest train stations, showcasing Neo-Renaissance influences and the country’s industrial growth.

The Romantic fascination with the Alps also influenced Swiss architecture, leading to the rise of mountain chalets—a style that remains popular today in Swiss Alpine resorts.

Swiss Modernism and the Bauhaus Influence (20th Century)

By the early 20th century, Swiss architecture was profoundly shaped by Modernism, with a focus on functionality, minimalism, and rational design. The most influential Swiss architect of this era was Le Corbusier (1887–1965).

Le Corbusier: The Father of Modern Architecture

Though he spent much of his career in France, Le Corbusier was born in Switzerland (La Chaux-de-Fonds) and his early work reflects Swiss design principles.

- His “Five Points of Architecture”—pilotis (supports), open floor plans, horizontal windows, free façades, and rooftop gardens—became the foundation of modernist architecture.

- Works like Villa Savoye (1929, France) and Unité d’Habitation (1952) revolutionized urban housing.

- His ideas inspired Swiss public housing, offices, and universities, influencing generations of architects.

Other Swiss modernists, like Max Bill and Alfred Roth, expanded on Bauhaus and Constructivist principles, further establishing Switzerland as a center of modernist design.

Contemporary Swiss Architecture: Global Innovation and Sustainability

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, Swiss architecture became known for cutting-edge design, sustainability, and experimentation with materials.

Herzog & de Meuron: Swiss Architecture on the Global Stage

Perhaps the most famous contemporary Swiss architects, Herzog & de Meuron (founded in 1978) have designed some of the world’s most iconic buildings.

- Tate Modern (London, 2000) – Transformed an old power station into a world-class museum.

- Beijing National Stadium (“Bird’s Nest”, 2008 Olympics) – A futuristic steel structure, redefining stadium design.

- REHAB Basel (2002) – A rehabilitation clinic using natural materials and light to create a soothing environment.

Their work combines Swiss precision with daring forms, making them leaders in contemporary architecture.

Peter Zumthor: The Master of Minimalism

Known for his sensitive use of materials and light, Peter Zumthor (b. 1943) creates meditative, sensory experiences through architecture.

- Therme Vals (1996) – A luxury thermal spa in the Swiss Alps, built with locally quarried stone, blending seamlessly into its surroundings.

- Kolumba Museum (Cologne, 2007) – A stunning blend of historical preservation and modern minimalism.

Zumthor’s designs reflect Swiss craftsmanship, sustainability, and harmony with nature, earning him the Pritzker Prize in 2009.

Sustainable and High-Tech Swiss Architecture

With a strong focus on eco-friendly and high-tech solutions, Swiss architecture is leading the way in sustainability.

- Monte Rosa Hut (2010, Zermatt) – A solar-powered mountain refuge, showcasing Swiss innovation in Alpine architecture.

- Rolex Learning Center (2010, Lausanne, by SANAA) – A futuristic low-energy building, blending fluid curves with green technology.

Swiss architects continue to push boundaries in urban planning, smart cities, and carbon-neutral buildings, influencing global trends.

Conclusion: Tradition Meets Innovation in Swiss Architecture

From medieval fortresses and Gothic cathedrals to modernist masterpieces and eco-friendly high-tech buildings, Swiss architecture embodies a unique fusion of heritage and experimentation. Architects like Le Corbusier, Herzog & de Meuron, and Peter Zumthor have ensured that Switzerland remains at the forefront of global architecture, shaping the future of design.

As we move into the final section, we’ll explore Switzerland’s role in the global art market, its major museums, and the future of Swiss art.

Museums, Collections, and the Role of Switzerland in the Art Market

Switzerland is not only home to world-renowned artists and architects but also plays a pivotal role in the global art market, museum curation, and private collections. With some of the most prestigious art institutions in Europe, as well as a reputation for financial discretion, art conservation, and high-profile auctions, Switzerland has become a global center for both artistic preservation and commerce.

This section explores Switzerland’s major art museums, the influence of Art Basel, the role of Swiss banking in the art trade, and the country’s importance as a hub for collectors and cultural institutions.

Switzerland’s Major Art Museums: Guardians of Cultural Heritage

Switzerland boasts some of the world’s finest art museums, housing collections that span from medieval masterpieces to cutting-edge contemporary works.

1. Kunstmuseum Basel: The Oldest Public Art Collection in the World

Founded in 1661, Kunstmuseum Basel is Switzerland’s most prestigious fine arts museum and is considered the world’s oldest public art collection.

- The museum holds a world-class collection of Renaissance and Baroque works, including pieces by Hans Holbein the Younger, Rembrandt, and Rubens.

- Its modern and contemporary section features works by Pablo Picasso, Paul Klee, and Mark Rothko, making it a key destination for art lovers.

2. Kunsthaus Zürich: The Heart of Swiss Modernism

The Kunsthaus Zürich houses Switzerland’s most extensive collection of modern and contemporary art, particularly focused on Swiss artists like Ferdinand Hodler, Alberto Giacometti, and Paul Klee.

- It also features major works by Van Gogh, Monet, and Chagall, highlighting Switzerland’s deep ties to European art history.

- The museum’s recent expansion, designed by David Chipperfield Architects, reinforces Zurich’s position as a major cultural hub.

3. Fondation Beyeler (Basel): A Private Collection of Masterpieces

One of Switzerland’s most celebrated private collections, Fondation Beyeler, was founded by art dealer Ernst Beyeler and features an exceptional selection of modern masterpieces, including works by Picasso, Monet, Warhol, and Rothko.

- The museum’s minimalist design by Renzo Piano blends harmoniously with nature, offering a serene viewing experience.

- It regularly hosts blockbuster exhibitions, making it a must-visit institution for contemporary and modern art.

4. Zentrum Paul Klee (Bern): A Tribute to Swiss Modernism

Dedicated entirely to Paul Klee, this museum in Bern houses over 4,000 works by the Swiss master, making it the most comprehensive collection of his art.

- Designed by Renzo Piano, the museum’s wave-like architecture reflects Klee’s organic approach to form and color.

- It offers extensive research and educational programs, preserving Klee’s legacy for future generations.

5. Museum Tinguely (Basel): A Celebration of Kinetic Art

Dedicated to Jean Tinguely, this museum showcases mechanical, moving sculptures that blend engineering with absurdity.

- It remains one of the most interactive and playful museums in Switzerland, reflecting Tinguely’s Dadaist influences.

6. The Swiss National Museum (Zurich): A Chronicle of Swiss Art and Culture

For those interested in historical Swiss art, the Swiss National Museum (Landesmuseum Zürich) presents an extensive collection of medieval altarpieces, Gothic sculptures, and Renaissance artifacts, offering insight into Switzerland’s artistic evolution.

Switzerland and the Global Art Market: The Power of Art Basel

Switzerland is not just home to great museums—it is also one of the world’s leading art trade centers, largely due to Art Basel, the most influential contemporary art fair globally.

Art Basel: The Epicenter of the Contemporary Art World

Founded in 1970, Art Basel has grown into the most prestigious international contemporary art fair, with satellite events in Miami and Hong Kong.

- It attracts major collectors, galleries, and artists, influencing global trends in the art market.

- Art Basel’s exclusive private sales and VIP previews often set auction records, reinforcing Switzerland’s role as an art finance hub.

- The fair’s conversations, performances, and installations make it more than just a market—it’s a cultural event shaping the direction of contemporary art.

Switzerland’s Role in Art Finance and Private Collections

Switzerland’s banking secrecy laws, tax advantages, and expertise in art conservation have made it a major center for art investment and private collecting.

- Many high-value art transactions are handled through Swiss freeports (tax-free storage facilities for art and collectibles), where artworks are kept outside national tax jurisdictions.

- The Geneva Freeport is one of the largest in the world, holding billions of dollars’ worth of Picassos, Monets, and contemporary blue-chip artworks.

- Switzerland is home to some of the world’s most powerful private collectors, including the Beyeler family, the Hoffmann collection, and Uli Sigg, whose vast collection of Chinese contemporary art has shaped international museum holdings.

The Swiss Approach to Art Conservation and Cultural Preservation

Switzerland is also a leader in art restoration and preservation, with major institutions dedicated to conserving historical and contemporary artworks.

- The Swiss Institute for Art Research (SIK-ISEA) in Zurich is one of Europe’s most advanced centers for scientific analysis of artworks, helping to authenticate and restore masterpieces.

- Swiss conservationists have worked on major international projects, preserving everything from Renaissance paintings to 20th-century conceptual installations.

Conclusion: Switzerland as a Global Art Powerhouse

Switzerland is not just a country of artists—it is a global hub for art museums, the art market, and cultural preservation. From the world’s oldest public collection in Basel to the high-tech freeports of Geneva, Switzerland plays a pivotal role in shaping the global art landscape.

As we conclude our deep dive, we’ll reflect on Switzerland’s ongoing artistic contributions and its future in the digital age.

The Future of Swiss Art: Digital Innovations and Global Influence

As Switzerland moves further into the 21st century, its art scene continues to evolve, blending technology, sustainability, and new media with its rich artistic heritage. While Swiss artists have always been known for precision, craftsmanship, and conceptual depth, today’s art world demands digital engagement, global collaboration, and experimental practices.

From AI-generated art and blockchain-based digital ownership (NFTs) to eco-conscious architecture and interactive installations, Swiss artists and institutions are at the forefront of shaping the future of art. This final section explores how Switzerland’s artistic identity is evolving, the key trends defining its future, and the role it will play on the global stage.

1. Digital Art and AI in Swiss Creativity

The rise of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and digital tools has transformed artistic creation, and Switzerland is actively contributing to this new frontier.

Swiss AI Artists and Algorithmic Creations

- Mario Klingemann, an artist working with AI and neural networks, has explored how machines can generate new forms of artistic expression, blending data science with aesthetic philosophy.

- The ETH Zurich Media Lab is pioneering AI-driven generative art, exploring how algorithms can collaborate with human artists.

NFTs and Blockchain-Based Art in Switzerland

With crypto-friendly policies and strong financial infrastructure, Switzerland has become a major hub for NFT-based art and blockchain authentication.

- Swiss-based platforms like Sedition and ArtMeta enable artists to sell digital works securely using blockchain technology.

- Traditional institutions, such as Kunsthaus Zürich and Art Basel, are exploring NFT exhibitions and virtual collections, bridging the gap between traditional and digital art markets.

2. Interactive and Immersive Art Installations

Swiss contemporary art is increasingly moving beyond static objects toward interactive, multisensory experiences.

- Pipilotti Rist’s immersive video environments—which place visitors inside vibrant, dreamlike projections—continue to push the boundaries of museum installations.

- The Light Art Festival in Geneva showcases cutting-edge projects using augmented reality, projection mapping, and kinetic sculptures.

- Swiss museums are adopting VR and AR technologies, allowing visitors to engage with historical and contemporary art in entirely new ways.

3. Sustainability and Eco-Art: Swiss Artists Addressing Climate Change

Switzerland, with its commitment to environmental consciousness, is seeing a rise in eco-art and sustainable design.

- Olaf Breuning, a Swiss artist working internationally, creates works that critique consumer culture and environmental destruction.

- Not Vital’s land art projects in remote locations merge sculpture, nature, and ecological preservation.

- Swiss architects are leading the world in sustainable design, with firms like Herzog & de Meuron and Peter Zumthor integrating zero-carbon materials and renewable energy solutions into their structures.

4. The Expansion of Switzerland’s Art Market and Global Influence