New Orleans is unlike any other city in America, and nowhere is that more evident than in its cemeteries. Locals call them “Cities of the Dead,” and it’s an apt name. Behind their wrought-iron gates lie rows of whitewashed tombs that resemble miniature houses, each one adorned with symbols, carvings, and statuary that speak to the city’s long, layered history. The art of New Orleans cemeteries is more than decoration—it’s a blend of faith, architecture, and identity that reflects the spirit of a place where French, Spanish, African, and American traditions meet.

A City Built Above the Water—and the Dead

The story of New Orleans cemeteries begins with geography. The city was founded in 1718 by the French near the mouth of the Mississippi River, on low, swampy ground. Early settlers soon discovered a problem: the water table was too high for traditional burials. When heavy rains came, coffins floated up out of the ground. The solution, borrowed from European and Caribbean traditions, was to bury the dead above ground in masonry tombs.

These early tombs were built of brick and covered with stucco, painted white to reflect the sun. Many of them resembled small chapels or homes, complete with arched doors and ironwork. Over time, entire “streets” of these family vaults grew into neighborhoods of the dead—an eerie yet oddly welcoming sight. The arrangement of these tombs, with narrow walkways and ornate facades, gives each cemetery the feeling of a small, silent town.

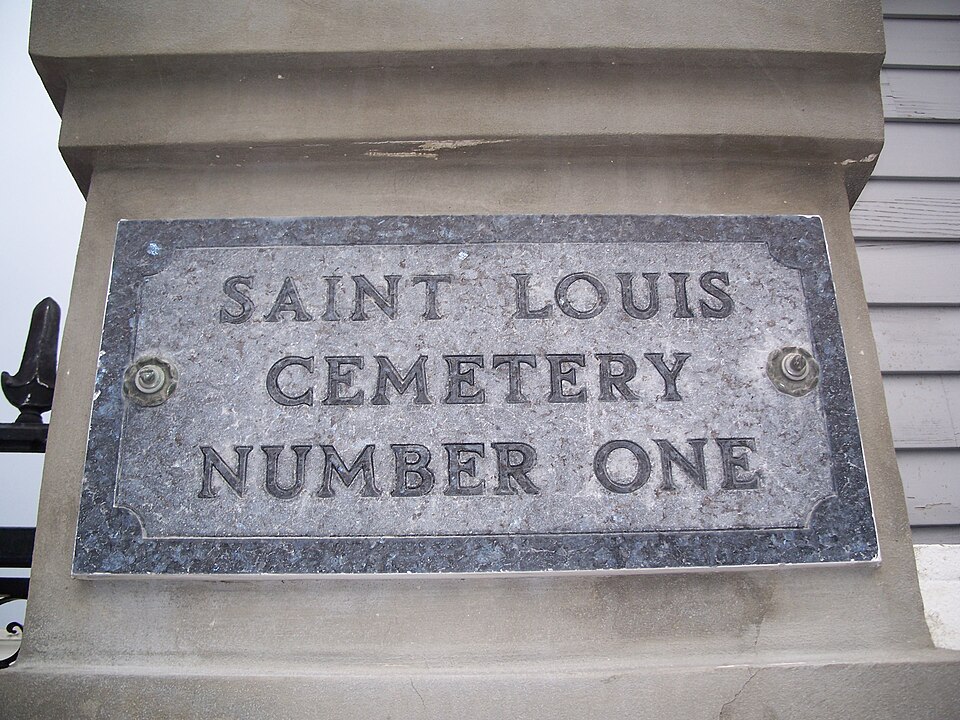

The Catholic Church played a guiding role in the design of these cemeteries. St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, established in 1789, remains the most famous. It’s the final resting place of local figures like the famed Voodoo practitioner Marie Laveau and the architect Benjamin Latrobe. Its mixture of French neoclassical and Creole styles set the pattern for generations of burial art to come.

The Architecture of Mourning

The artistry of New Orleans cemeteries lies as much in their architecture as in their symbolism. In the 19th century, as the city prospered from trade along the Mississippi, families expressed their wealth and taste through the design of their tombs. Architects and stone masons crafted elaborate vaults that rivaled the city’s finest buildings.

Many of these structures borrow elements from classical design—columns, pediments, and cornices drawn from Greek Revival or Romanesque styles. Others reflect the French and Spanish influences that shaped Creole culture. Some even imitate Gothic cathedrals in miniature, complete with pointed arches and carved finials.

Materials were often imported: marble from Italy, slate from Vermont, wrought iron from France. Local artisans added their own touches. You’ll find cast-iron fences with fleur-de-lis motifs, carved angels with weathered wings, and crosses fashioned in both Latin and Greek forms. The craftsmanship is remarkable, considering the city’s harsh climate and the centuries that have passed.

The vault system itself had an artistic logic. Because tombs could not be reused for several years (the heat of New Orleans hastened decomposition), families developed a method called “rotation burial.” Once remains were reduced to bones, they were placed in a chamber below, making room for the next generation. These family vaults thus became living records of lineage, their facades often inscribed with dozens of names—a sculptural family tree carved in stone.

The Symbolic Language of Death

The art of New Orleans cemeteries speaks in a rich symbolic language, one that merges Catholic devotion with classical imagery and folk belief. Every symbol carved into stone carries a message.

The cross, of course, dominates, representing salvation and eternal life. But there are subtler emblems too: draped urns signify mourning, broken columns mark a life cut short, and clasped hands suggest farewell and reunion in heaven. Ivy represents fidelity, laurel suggests victory over death, and lambs denote innocence, often carved on children’s tombs.

Angels appear everywhere, sometimes triumphant, sometimes weeping. Some bear trumpets, echoing the Book of Revelation’s promise of resurrection. Others hold flowers—roses for love, lilies for purity. Many of these sculptures were mass-produced in northern foundries during the Victorian era, but New Orleans artists often re-worked them, giving each figure a distinct local character.

Catholic imagery also blends with African and Creole elements, especially in older cemeteries. The tomb of Marie Laveau, for example, is famously covered in small “X” marks, left by those who believe in her spiritual power. Offerings—coins, candles, beads—collect at her vault, merging Christian and African spiritual traditions in a uniquely New Orleanian way. Even the practice of leaving such tokens echoes ancient folk customs, linking the living and the dead through acts of devotion.

Cemeteries as Sculpture Gardens

Walk through Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 in the Garden District, and it feels almost like a museum. Founded in 1833, it holds more than 1,000 family tombs arranged in neat, tree-lined aisles. Each vault tells a story through its design. Some are stark and neoclassical; others bristle with ironwork or bear finely carved epitaphs. The play of light and shadow across white plaster and gray stone creates a haunting beauty that photographers and painters have long sought to capture.

The effect is heightened by decay. In New Orleans, even death weathers gracefully. Moss drapes over crosses; lichen blooms on marble angels. Cracked stucco reveals red brick beneath, giving each tomb a patina of age. For many visitors, this mixture of beauty and ruin feels almost romantic, a reminder of the passage of time and the endurance of memory.

Artists have drawn inspiration from this atmosphere for generations. The poet Walt Whitman, visiting in the 1840s, wrote of the “silent majesty” of these tombs. Contemporary painters often render their geometric forms in bright Louisiana light, turning decay into art. Even filmmakers—from Easy Rider to Interview with the Vampire—have used these cemeteries as backdrops, recognizing their cinematic blend of solemnity and splendor.

The Creole Influence and Cultural Fusion

The art of New Orleans cemeteries cannot be understood apart from the city’s Creole heritage. The word “Creole” once referred broadly to people born in Louisiana of European descent, but over time it came to include a diverse mix of French, Spanish, African, and Caribbean ancestry. This cultural fusion shaped every aspect of local life—language, food, architecture, and faith—and the cemeteries are no exception.

French and Spanish Catholic traditions encouraged elaborate above-ground tombs, while African customs emphasized honoring ancestors through offerings and ritual. The result is a blend that feels both sacred and communal. Many burial societies, such as the Société Française de Bienfaisance, maintained large group tombs for members who could not afford private ones. These “benevolent society” tombs often bear decorative plaques or sculptures that celebrate fraternity and shared faith.

African influence also appears in the symbolic use of color and rhythm. Whitewashing tombs each All Saints’ Day—a custom that continues in parts of Louisiana—echoes African practices of tending ancestral graves. Music, too, plays a role. The tradition of the jazz funeral, born from a mixture of Catholic ritual and African celebration, turns mourning into a procession of both sorrow and joy. The brass band leads mourners from the church to the cemetery with hymns, then bursts into lively jazz on the way back, symbolizing the soul’s release. This ritual transforms death into a work of art in motion.

Preservation and the Challenge of Time

Despite their enduring beauty, New Orleans cemeteries face serious threats. Humidity, flooding, and neglect have taken their toll. Hurricanes have toppled statues and dislodged tombs, while salt and mold eat away at marble inscriptions. In the past century, some cemeteries were abandoned or vandalized as the city expanded and maintenance costs grew.

Preservation efforts have increased in recent decades. Organizations like Save Our Cemeteries and the Archdiocese of New Orleans work to restore tombs, document inscriptions, and educate the public. Restoration requires skill, since old materials must be matched carefully and drainage problems solved without disturbing remains. It’s not simply about saving history—it’s about preserving a unique form of art that belongs to the city’s soul.

Tourism brings both funding and strain. Cemeteries like St. Louis No. 1 now require guided tours to prevent damage. This has sparked debate among locals who see the cemeteries as sacred places rather than attractions. Yet responsible tourism also helps protect them, ensuring that new generations understand their beauty and meaning.

Art, Faith, and the Living City

To walk through a New Orleans cemetery is to walk through layers of art and faith intertwined. The design of each vault, the symbolism carved in each stone, and the customs surrounding burial all express a belief in the continuity of life and death. For the people of New Orleans, remembrance is not passive—it is active, creative, and communal.

Even today, new tombs are built with artistic care. Modern masons echo the old forms, while artists and sculptors continue to decorate these sacred spaces. Photography exhibitions, watercolor studies, and even architectural surveys treat the cemeteries as living art forms. They are reminders that beauty and mortality can coexist, and that faith can find expression not only in churches but in the quiet streets of the dead.

In a city famous for its music and revelry, the cemeteries offer a counterpoint—a silent harmony to the life that pulses outside their walls. The artistry found there is not merely ornamental; it’s an act of defiance against time. Each statue, each name carved in stone, each chipped cornice whispers the same message: life is fleeting, but art endures.

Why the “Cities of the Dead” Endure in the Imagination

What draws people to these cemeteries year after year? Part of it is the visual splendor, part is curiosity, and part is something deeper. The “Cities of the Dead” embody the paradox at the heart of New Orleans: the coexistence of joy and sorrow, faith and superstition, decay and renewal. They show how a city that has endured floods, fires, and epidemics still finds beauty in remembrance.

Artists, historians, and visitors alike sense that these places are more than graveyards. They are archives of culture—open-air galleries where art, architecture, and faith tell a shared story. In the iron lacework, the crumbling stucco, the glint of marble under moss, you can read the whole character of New Orleans: elegant, eccentric, devout, and unafraid of the passage of time.

In the end, the art of New Orleans cemeteries reflects a truth as old as civilization itself—that honoring the dead is a form of creating art for the living. These tombs are not monuments to despair but to continuity. They remind us that memory, like architecture, must be built to last.

Key Takeaways

- Geography shaped design: New Orleans’ high water table required above-ground burials, leading to the distinctive “Cities of the Dead.”

- Art and architecture merge: The cemeteries showcase Greek Revival, Gothic, and Creole styles, crafted with marble, iron, and stucco.

- Symbolism abounds: Crosses, angels, urns, and floral motifs communicate faith, love, and resurrection.

- Cultural fusion defines them: French, Spanish, African, and Caribbean influences blend in burial art and ritual.

- Preservation is vital: Restoration efforts protect these unique artistic and historical landmarks for future generations.

FAQs

1. Why are New Orleans cemeteries built above ground?

Because the city sits below sea level, traditional burials caused coffins to rise during floods. Above-ground tombs solved the problem and became a local tradition.

2. What makes St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 famous?

It’s the oldest in the city, dating to 1789, and holds the tombs of notable figures such as Marie Laveau and architect Benjamin Latrobe.

3. How do Creole and African traditions influence cemetery art?

They shaped burial societies, ancestor veneration, and rituals like jazz funerals, merging Catholic faith with African spirituality.

4. Are the cemeteries still in use today?

Yes, many family vaults continue to serve descendants, and new tombs are built in traditional styles.

5. Can visitors tour the cemeteries?

Yes, though major ones like St. Louis No. 1 require guided tours to prevent damage and protect historic tombs.