The story of Athens is a story of art, inscribed across millennia in marble, clay, pigment, and bronze. Few cities in the world possess a legacy so deeply intertwined with the development of visual culture. From the austere beauty of Cycladic figurines to the grandeur of the Parthenon, and from Byzantine mosaics to the graffiti of Exarchia, Athens has been a living canvas on which the aesthetic ideals, political ideologies, and spiritual beliefs of entire civilizations have been projected, contested, and reinvented.

What makes Athens exceptional is not simply the quality or quantity of its artistic output, but its ability to generate meaning across time. This is a city where the ruins of classical temples coexist with Ottoman mosques, where neoclassical facades stand beside Bauhaus apartments, and where street murals protest economic austerity only blocks away from the ancient Agora. It is a palimpsest of artistic epochs, a place where every stone tells a story and every visual style echoes a different moment in history.

Art in Athens has always been more than ornament. In the 5th century BCE, it was a tool of civic identity, a public declaration of democratic values and collective memory. Later, under Roman and Byzantine rule, art became an expression of imperial prestige and divine authority. During the long centuries of Ottoman occupation, its role shifted again—reduced, preserved, or transformed in subtle ways, often with an undercurrent of resistance. Then, in the 19th century, Athens was recast by European philhellenism and Greek nationalism as the birthplace of Western civilization, its ancient art elevated as a standard for global beauty and reason.

But Athens is not a museum. Despite the overwhelming presence of antiquity, the city pulses with artistic life in the present. It is home to radical new art spaces, activist collectives, and biennials that grapple with the complexity of Greece’s place in the modern world. These contemporary voices do not ignore the past—they wrestle with it, reinterpret it, sometimes even deface it, revealing an ongoing conversation between generations of creators.

In this deep dive, we will walk through the long arc of Athenian art history—from the earliest human traces to today’s multimedia experiments—asking not only what was made and why, but how each artistic era interacted with the ones before and after it. We’ll meet the nameless artisans of the Bronze Age, the famed sculptors of the Classical period, the Christian icon painters of Byzantium, and the street artists of modern Plaka. We’ll explore materials and techniques, myths and politics, ruins and restorations.

By tracing this continuum, we aim to understand Athens not merely as a repository of heritage, but as a creative force that has continually reinvented itself through its art. Whether as an imperial capital, a colonized province, or a modern European city, Athens has always made visible the ideas it wished to project—and the tensions it tried to conceal. In short, to follow the art of Athens is to follow the soul of a civilization.

Prehistoric and Bronze Age Roots: Cycladic and Mycenaean Echoes

Long before the marble of the Parthenon gleamed under the Athenian sun, before democracy, drama, and Doric columns, the land that would become Athens was already home to artistic expression. The earliest artistic roots of Athens are buried deep in the prehistoric layers of the Aegean world—an interconnected cultural web that included the Cycladic islands, the Minoan palaces of Crete, and the fortified citadels of the Mycenaean mainland. Though Athens itself played a relatively modest role in the Bronze Age compared to Mycenae or Knossos, the art of this era laid essential foundations: symbolic systems, visual languages, and material traditions that would echo through Athenian history for centuries.

The First Settlers and the Neolithic Imprint

Archaeological evidence places human settlement on the Acropolis hill as early as the Neolithic period (circa 5000 BCE). These early inhabitants left behind fragments of pottery, tools, and rudimentary figurines—objects that, while lacking the refinement of later Greek art, mark the first stirrings of a visual culture. Designs were often geometric, abstract, and repetitive—elements that would resurface millennia later in the Geometric art of early Athens. The emphasis on symmetry and symbolic decoration was not just aesthetic; it pointed to a worldview rooted in ritual, agriculture, and the rhythms of nature.

Cycladic Influences: Abstraction Before Abstraction

Although centered in the islands to the south, Cycladic culture (circa 3200–2000 BCE) cast a long shadow over the Aegean world, including Attica. The iconic Cycladic figurines—usually female, carved in white marble, and strikingly minimal—are among the earliest known examples of stylized human representation in European art. Their flattened forms, folded arms, and featureless faces (save for a single prominent nose) evoke a modernist sensibility that later artists like Modigliani, Brâncuși, and Picasso would admire and emulate. While no major Cycladic sanctuary has been found in Athens, the city’s early tombs and archaeological strata include Cycladic imports, suggesting early trade and cultural transmission.

These figurines weren’t mere decorations. They likely played roles in religious rites or funerary practices, speaking to an early use of art as a spiritual mediator. Their abstraction wasn’t a lack of skill—it was a deliberate aesthetic choice, perhaps aimed at universality or timelessness.

Minoan Echoes and the Flow of Ideas

By the Middle Bronze Age, Athens became increasingly connected to Minoan Crete, a civilization renowned for its vibrant frescoes, palatial architecture, and naturalistic design. While Athens did not replicate the monumental Minoan structures, motifs such as spirals, marine life, and floral patterns made their way into Athenian ceramics and small-scale art. These early cross-cultural interactions planted the seeds for the eclecticism that would later characterize Athenian style: the ability to absorb, adapt, and refine external influences.

Mycenaean Athens: Citadels and Symbolic Power

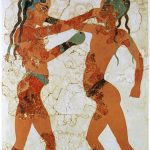

Around 1600 BCE, the Greek mainland entered the Mycenaean period, and Athens—though not a leading Mycenaean power—developed as a fortified settlement centered on the Acropolis. Mycenaean art is often described as martial and monumental, but it also possessed a deep symbolic vocabulary. The art of this period included painted pottery, gold death masks, elaborate frescoes, and intricately carved seals and signet rings.

In Athens, archaeological finds from the Mycenaean period—such as the chamber tombs in the area of Kolonos and pottery from the Agora—demonstrate a city participating in this broader visual culture. The imagery on these artifacts often featured chariots, lions, warriors, and spiral motifs. These weren’t merely decorative scenes; they reflected a society organized around hierarchy, warfare, and divine legitimation. The use of art in burial contexts suggests it had a role in negotiating the afterlife and asserting status.

A particularly significant legacy of Mycenaean Athens lies not in its material remains but in myth. Later Athenian identity would root itself in the mythic kings of the Bronze Age—Cecrops, Erechtheus, Theseus—figures who were retroactively placed into a cultural genealogy that justified Athens’ greatness. Theseus, the slayer of the Minotaur, is a case in point: a heroic bridge between Mycenaean legacy and Classical imagination, his myth anchoring Athenian claims to ancient nobility and cultural centrality.

The Collapse and a Silent Interlude

Around 1200 BCE, the Mycenaean world collapsed in a wave of upheaval that swept across the Eastern Mediterranean. Cities were abandoned, palaces burned, and systems of writing disappeared. Athens, however, uniquely survived the Bronze Age collapse without total destruction. While its influence waned, it remained continuously inhabited, preserving threads of artistic and cultural continuity. This resilience would become central to Athenian self-identity later on—Athens as the eternal city, never conquered, always reborn.

What followed was a so-called “Dark Age” (circa 1100–800 BCE), during which artistic production slowed, but did not cease. Simpler pottery styles, such as the Submycenaean and Protogeometric, continued, hinting at an undercurrent of survival and adaptation. Even in decline, the visual language of Athens was evolving, preparing for the burst of innovation that would arrive with the Geometric period.

The prehistoric and Bronze Age chapters of Athens’ artistic story are often overshadowed by the dazzling heights of the Classical period. But these early epochs laid the foundation for everything that followed. They shaped how Athenians saw the body, the divine, and their place in the cosmos. They taught the value of symbolism, of abstraction, of material power. And they ensured that when Athens finally rose to glory, it did so on a bedrock of artistic memory stretching back thousands of years.

The Geometric and Archaic Periods: Foundations of Greek Aesthetic Ideals

Between the twilight of the Mycenaean world and the dawn of Classical Athens lies a transformative era often overlooked in popular histories but crucial to understanding the emergence of Greek—and especially Athenian—art. The Geometric (circa 900–700 BCE) and Archaic (circa 700–480 BCE) periods were not merely transitional. They were formative, laying the aesthetic, symbolic, and narrative groundwork for the artistic explosion of the 5th century BCE. This was a time when Athens began to define its artistic voice, experimenting with form, myth, and monumental expression.

The Geometric Period: Order from Chaos

The Geometric period derives its name from the striking pottery that began to appear in Athens around the 9th century BCE. These vessels, covered in meanders, concentric circles, zigzags, and triangles, marked a radical departure from the looser, naturalistic forms of the Mycenaean age. This was a time of reorientation—after centuries of decline, Athens and other Greek cities were reinventing their cultural identities. The visual emphasis on symmetry and pattern reflected a deeper desire for order, clarity, and structure.

One of the most iconic works from this era is the Dipylon Amphora, a nearly 5-foot-tall funerary vase found near the Dipylon Gate in Athens’ Kerameikos cemetery. Covered in intricate geometric designs, it features a scene of mourning—a deceased figure lying in state surrounded by mourners who raise their arms in stylized grief. This is one of the earliest instances of narrative in Greek art: not merely decoration, but a story rendered in visual form. It demonstrates an emerging sophistication in the use of art to express communal rituals and societal values.

These large vessels were used as grave markers, linking art with public memory and social hierarchy. In a sense, they were among the first monuments of the Athenian polis, staking a claim in time and space for individual legacy and collective tradition.

The Emergence of the Human Figure

During the Late Geometric period, a dramatic development occurred: the reappearance of the human form. At first, figures were highly stylized—stick-like bodies, triangular torsos, dot eyes—but they were dynamic. Scenes depicted warriors in chariots, naval battles, funerary processions, and mythic duels. The Athenian imagination was expanding. Art was not merely mimetic; it was becoming a tool of storytelling and identity formation.

What’s striking is how quickly this figural tradition evolved. By the 8th century BCE, artists were already pushing the boundaries of what clay could convey, foreshadowing the naturalism that would become a hallmark of later Greek sculpture and painting.

The Archaic Period: The Smile Before the Revolution

By the early 7th century BCE, Athens entered the Archaic period—a time of monumental ambition and cultural exchange. As trade and contact with the Near East and Egypt intensified, so too did the complexity of Greek art. This era saw the adoption of new motifs—lotuses, griffins, sphinxes—as well as technical innovations like black-figure pottery and monumental stone sculpture.

In Athens, the Archaic period was a time of civic emergence. The city began to organize itself around proto-democratic institutions, religious sanctuaries, and formal laws. Art followed suit, taking on public and sacred functions. One of the great artistic inventions of this period was the kouros (male nude statue) and kore (clothed female figure), both used as votive offerings and grave markers.

Athens developed its own distinctive kouroi—tall, idealized youths standing rigidly with one foot forward, fists clenched, eyes wide, and mouths curled in the enigmatic “Archaic smile.” These figures were not portraits; they were symbols—of virtue, beauty, and civic pride. Their stylized anatomy showed an increasing attention to musculature and proportion, but they were still deeply abstracted, caught in a moment of formal experimentation.

The Acropolis Kore statues, a group of Archaic female figures found on the Athenian Acropolis, demonstrate both the richness of Athenian style and the religious fervor of the time. These brightly painted statues (yes, the ancients loved color) were dedicated to Athena and other deities, and their intricate drapery and detailed hair reveal an evolving sensitivity to texture and realism.

Black-Figure Ceramics: Athenian Craft Takes the Lead

While Corinth initially led the development of black-figure pottery (a technique where figures were painted in silhouette with added incised detail), Athens quickly became a center of innovation. By the mid-6th century BCE, Athenian potters and painters like Exekias elevated black-figure to a high art form.

Exekias’ amphora depicting Achilles and Ajax playing a board game is a masterclass in narrative restraint and psychological nuance. The figures, though locked in a quiet moment, are warriors fated for tragic ends. The scene becomes a meditation on fate, chance, and heroism—timeless Athenian themes.

Such pottery was not just for local use. Athenian ceramics were exported across the Mediterranean, becoming cultural ambassadors for the city. These vessels carried Athenian myths, values, and aesthetics far beyond Attica.

Myth-Making and Identity

Throughout the Archaic period, art in Athens began to embrace myth not just as entertainment, but as ideology. Depictions of Theseus, Athena, Herakles, and the Gigantomachy (battle between gods and giants) proliferated. These were not neutral tales—they were Athenian myths, used to assert primacy, heroism, and divine favor. In sculpture, pottery, and even temple decoration, the Athenians were laying visual claim to a past that legitimized their present.

One critical example is the early temple of Athena on the Acropolis, often called the “Bluebeard Temple” due to fragments of a pediment sculpture showing a bearded figure with serpent tails. Though fragmentary, it points to an early interest in large-scale public art tied to myth and civic identity—a prelude to the monumental programs of the Classical era.

By the end of the Archaic period, Athens had built the scaffolding of its future glory. Its artists were exploring anatomy, emotion, and narrative with increasing sophistication. Its myths had found visual form. Its public spaces were beginning to fill with art that reflected and shaped civic life. In these centuries, Athenian art transitioned from the abstract to the human, from the functional to the ideological—from pattern to presence.

What would come next, in the Classical period, was not an emergence from a vacuum but an elevation built on these essential foundations.

The Classical Golden Age: Art and Democracy in Periclean Athens

The 5th century BCE was a miracle of convergence—a moment when politics, philosophy, and art aligned to produce a cultural flowering that would become the bedrock of Western aesthetic ideals. At the heart of it all was Athens. Under the leadership of Pericles, and amid the backdrop of democratic revolution, imperial ambition, and philosophical inquiry, Athens embarked on an extraordinary project: to make its values visible. Through temples, sculptures, and civic monuments, the city constructed a new visual language—one that embodied order, rationality, and the potential of the human form. This was not just a golden age; it was a manifesto in marble.

Democracy as Muse

The early 5th century BCE was shaped by two defining events: the defeat of the Persian Empire and the consolidation of Athenian democracy. The Persian Wars (490–479 BCE) were more than military victories—they were existential affirmations. In their aftermath, Athens claimed not only security but cultural superiority. Art became a way to express this confidence, to monumentalize memory, and to define what it meant to be Greek—and, more specifically, Athenian.

Pericles, a statesman of remarkable vision, understood the power of art as a political tool. His building program on the Acropolis was as much about ideology as architecture. With funds from the Delian League—a coalition of Greek city-states that Athens dominated—Pericles turned the city into a showcase of imperial and democratic power. The result was a civic center unmatched in its scale and symbolism.

The Parthenon: Perfection in Stone

At the summit of this artistic endeavor stood the Parthenon, a temple to Athena Parthenos, the city’s patron deity. Designed by Iktinos and Kallikrates and adorned with sculpture by Phidias, it was completed between 447 and 432 BCE. More than a temple, the Parthenon was a statement: of balance, control, proportion, and piety. Every detail—from the slight curvature of its columns to the idealized figures in its pediments—was calculated to create harmony.

The sculptural program was equally ambitious. The east pediment depicted the birth of Athena from the head of Zeus; the west, her contest with Poseidon for the city. The metopes (square panels above the columns) portrayed mythic battles: Lapiths vs. centaurs, Greeks vs. Amazons, gods vs. giants—each a metaphor for order triumphing over chaos. Most famously, the Panathenaic frieze, which ran along the inner perimeter of the temple, depicted a religious procession involving citizens, priests, and sacrificial animals. This was radical: for the first time, mortals appeared in a temple’s decorative scheme, suggesting a divine civic harmony between gods and Athenians.

At the center stood the chryselephantine statue of Athena, a towering image made of gold and ivory, designed by Phidias. Though lost, its descriptions evoke awe: helmeted, spear in hand, shield at her side, she embodied martial wisdom and serene power. She was Athens itself, personified.

Phidias and the Sculptural Revolution

Phidias, often considered the greatest sculptor of antiquity, was the artistic director of the Periclean building program. His work marked a turning point in the representation of the human form. Where earlier statues had been stiff and formulaic, Phidias introduced fluidity, depth, and dignity. Drapery clung to bodies like wet fabric, revealing musculature and movement beneath. Faces radiated calm intelligence—neither ecstatic nor rigid, but poised.

Though we possess no originals attributed definitively to Phidias, Roman copies of his works—such as the Zeus of Olympia, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World—suggest a genius for scale and symbolism. His influence was immediate and enduring. Artists like Polykleitos and Myron followed, each pushing the boundaries of anatomy and poise, creating what would later be termed the Classical canon.

Architecture and Civic Space

Beyond the Parthenon, Athens bloomed with civic and religious structures: the Erechtheion, with its famous Caryatid porch, demonstrated a lyrical elegance, where columns became draped female figures supporting the temple’s weight. The Propylaea, designed by Mnesikles, marked the dramatic entrance to the Acropolis, blending military form with ceremonial function.

These buildings were not isolated monuments—they were embedded in the city’s social and political life. The Acropolis became a visual map of Athenian values: reverence for the gods, celebration of civic identity, and the fusion of art and reason. Down below, the Agora, or public square, was ringed by stoas, statues, and altars. It was not just a marketplace—it was the stage of democracy, a space where rhetoric, philosophy, and law intersected with everyday life.

The Role of the Citizen in Art

What’s remarkable about Classical Athenian art is how it made the citizen central. While the gods still loomed large, the human figure took on unprecedented prominence. The ideal male nude—athletic, calm, perfectly proportioned—represented not only physical beauty but moral virtue. The citizen-soldier was elevated to the realm of the heroic. Female figures, while still idealized, began to show greater nuance and individuality, especially in funerary sculpture.

This was the age of the stele, or gravestone relief, many of which were erected in the Kerameikos cemetery. These scenes—of women bidding farewell to family, of men in quiet contemplation—are haunting in their intimacy. They reveal a new sensitivity to emotion and memory, an Athenian vision of death as a personal and civic event.

Drama, Philosophy, and the Visual Mind

Art in Classical Athens was never siloed. It existed in dialogue with other forms of expression. The tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides—staged in the Theater of Dionysus—explored the same myths depicted on vases and friezes. The philosophies of Socrates and Plato emerged amid a culture obsessed with proportion, order, and the nature of beauty. Art was not merely decoration—it was an argument, a reflection of how the world ought to be.

This intellectual ferment gave Classical art its singular quality: idealism grounded in realism. Artists strove not just to depict what they saw, but what they believed could exist—the perfect body, the just city, the noble citizen.

By the close of the 5th century BCE, Athens had created an artistic identity that would resonate for millennia. The Classical style—balanced, rational, ideal—would become the benchmark for Western art, revived again in the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, and even in modern democratic architecture. But in its own time, it was a living language, born from a radical experiment in self-governance and collective imagination.

Athens had built not only temples and sculptures but a visual system for understanding human potential. And though war, plague, and internal strife would soon shake the city, the artistic legacy of the Classical period would remain indelible.

Sculpture and Humanism: The Idealized Body and the Birth of Naturalism

If the Classical period was the golden age of Athenian art, then sculpture was its most eloquent expression. Through sculpture, Athens articulated its deepest beliefs—about divinity, beauty, mortality, and what it meant to be human. This was not merely art as decoration or religious offering; it was art as philosophy made flesh. In stone and bronze, the Greeks—especially the Athenians—attempted something audacious: to depict the human body not as it was, but as it ought to be. In doing so, they created a visual language of perfection that would define Western ideals of form and proportion for centuries to come.

The Turn Toward Naturalism

To appreciate the revolutionary leap of Classical sculpture, one must first understand what came before. Archaic figures—like the kouros and kore—were static, symmetrical, and abstracted. They hinted at anatomy but did not fully embrace it. Then, around 480 BCE, something shifted. In a series of works often referred to as the Severe Style, Athenian sculptors began experimenting with weight distribution, musculature, and expression. The result was a new sense of physical presence, a recognition that the human figure was not a symbol but a dynamic organism.

One early masterpiece is the Kritios Boy, found on the Athenian Acropolis and dated to around 480 BCE. Though missing its arms and lower legs, this sculpture marks a clear break from the past. The body stands in contrapposto—a slight shift in weight onto one leg, causing the hips and shoulders to tilt in opposite directions. The result is a relaxed, lifelike pose. The face is serene, even inward-looking, reflecting a growing Athenian interest in the interior life as well as external form.

This was the beginning of naturalism, not just in the anatomical sense, but in the philosophical one. The human form was no longer a rigid archetype—it was a site of balance, reason, and introspection.

Polykleitos and the Canon of Proportion

While many of the most famous Classical sculptors worked across the Greek world, their influence was profoundly felt in Athens. Among them, Polykleitos of Argos was a towering figure. Though not Athenian, his treatise—the Canon—and his sculpture of the Doryphoros (Spear Bearer) became deeply influential in the Athenian context.

Polykleitos believed that beauty lay in mathematical proportion. He developed a system of ratios for every part of the body, believing that perfect harmony could be achieved through precise measurement. The Doryphoros is the visual realization of this theory: a poised, muscular youth, balanced yet dynamic, ideal yet believable. Though the original bronze is lost, Roman marble copies proliferate, underscoring its long-lasting impact.

Athens, in its pursuit of order and democracy, found a kindred spirit in Polykleitos’ method. His approach mirrored the city’s broader cultural project: the reconciliation of chaos and order, emotion and reason, self and society.

Myron and the Art of Motion

Another influential figure was Myron, whose Discobolus (Discus Thrower) captured a moment of athletic motion frozen in time. Here, too, we see the fusion of naturalism and idealism. The pose is anatomically impossible—no athlete could hold it—but it conveys the essence of physical tension, concentration, and harmony.

Athleticism was central to Athenian identity. The gymnasium was a civic institution, a place where the mind and body were trained together. Myron’s work doesn’t just celebrate physical prowess; it embodies the Athenian belief in arete—excellence in all things, including the cultivation of the body as a moral and political act.

Phidias and the Divine Human

While Polykleitos and Myron explored idealized mortals, Phidias remained the master of the divine. His great works—the chryselephantine statues of Athena Parthenos in the Parthenon and Zeus at Olympia—were more than religious icons. They were ideological monuments, merging human perfection with godly grandeur.

Phidias’ gods looked like Athenians—not in dress or demeanor, but in form. They were majestic, calm, rational, and beautiful. Their divinity lay not in supernatural features but in the amplification of human qualities. This was humanism in its most elevated form: not a denial of the divine, but a reshaping of it in human terms.

The sculptural decoration of the Parthenon, largely attributed to Phidias and his workshop, reflects this ethos. The figures on the metopes, frieze, and pediments—whether gods, heroes, or mortals—are all rendered with the same attention to anatomy, emotion, and dignity. Even in battle scenes, there is no gore or agony, only noble struggle.

The Female Form and the Kore Transformed

Classical Athens remained a deeply patriarchal society, and this is reflected in its art. Yet female figures in sculpture also underwent a transformation. The rigid korai of the Archaic period gave way to more naturalistic, emotive women—especially in funerary sculpture. The Stele of Hegeso, a marble grave relief from the late 5th century BCE, shows a woman seated, examining a piece of jewelry handed to her by a servant. The scene is quiet, domestic, but the rendering of drapery and expression is extraordinarily refined. This was sculpture not of power, but of memory, intimacy, and loss.

Religious sculpture also began to explore the feminine divine in new ways. Though the full nudity of female figures was largely avoided until the later Classical and Hellenistic periods, statues of goddesses like Aphrodite, Artemis, and Athena began to show more psychological depth and formal complexity.

Bronze and Marble: Material and Message

While many of the sculptures we see today are marble, the true glory of Classical sculpture was bronze. Lightweight, durable, and capable of finer detail, bronze allowed for dynamic poses and expressive surfaces. Unfortunately, bronze was often melted down in later periods, making surviving originals rare. But the few that remain—such as the Riace Warriors or the Bronze Youth of Antikythera—reveal the astonishing vitality of Classical bronze work.

In Athens, both marble and bronze served different functions. Marble was often used for temples and funerary monuments—works meant to endure and impress. Bronze, meanwhile, populated public spaces, honoring victors, deities, and civic heroes. These statues were not isolated art objects—they were integrated into the cityscape, part of the visual and moral education of the citizen.

By the late 5th century BCE, Athenian sculpture had achieved a synthesis rarely equaled in the history of art. It married technical mastery with philosophical depth, political ideology with individual emotion. It created a standard of human form and expressive restraint that would be copied and contested for millennia.

In this pursuit of the ideal body, Athens revealed its deepest convictions: that beauty lay in balance, that humanity could aspire toward the divine, and that art was not mere imitation of nature, but a shaping of it toward a vision of perfection.

The Painted City: Vase Painting, Narrative, and Daily Life

In ancient Athens, the walls of homes were bare and whitewashed, but the city was anything but visually plain. Its art was not confined to monumental sculpture and temple friezes—it lived on everyday objects. Nowhere is this clearer than in the vast corpus of painted pottery that has survived from antiquity. These vessels, once used for everything from wine storage to funerary rituals, are not just remnants of utilitarian craft. They are the visual literature of Athenian life—filled with myth, gossip, celebration, and the subtle codes of social life.

Vase painting in Athens reached its technical and artistic peak between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE. During that time, Athenian potters and painters created a dazzling range of ceramic works that were exported across the Mediterranean. The motifs painted on these pots were not arbitrary. They reveal what Athenians admired, feared, joked about, and remembered. In a city where civic pride and mythic consciousness went hand-in-hand, the painted vase was both an art object and a mirror of society.

Black-Figure Beginnings: Incised Mythology

The black-figure technique, developed in Corinth in the 7th century BCE and perfected in Athens in the 6th, involved painting figures in a black slip on red clay and incising details with a sharp tool. This allowed for fine linear work and dramatic contrasts, especially when enhanced with white and red highlights.

Early Athenian black-figure painters such as the Amasis Painter, Lydos, and above all Exekias, elevated the form into a high art. Exekias was both potter and painter—a rare combination that allowed him full control over both shape and surface. His amphora showing Achilles and Ajax playing dice is a masterclass in composition and psychological storytelling. The warriors, seated in calm anticipation, are poised between leisure and destiny—a quiet moment heavy with the weight of myth. Their names are incised above their heads, as if to immortalize the scene as both mythic tableau and domestic familiarity.

Black-figure was ideal for mythological drama: battles between gods and giants, Herakles’ labors, Dionysian revels, and Theseus’ exploits adorned countless vessels. Yet even in these mythic scenes, the painter often injected distinctly Athenian values—cunning, moderation, piety, and civic virtue.

Red-Figure Revolution: Painting with the Brush

Around 530 BCE, a major innovation occurred in Athenian pottery: the red-figure technique. Here, the background was painted in black slip, leaving the figures in the natural red of the clay. Instead of incision, details were painted with a fine brush, allowing for greater flexibility, fluidity, and realism. Musculature, facial expression, drapery folds—all became more expressive and nuanced.

Red-figure rapidly eclipsed black-figure as the dominant style, and Athenian workshops exploded with innovation. Euphronios, Euthymides, Douris, and later Makron, The Niobid Painter, and Meidias Painter each developed distinct styles and favored themes.

Euphronios’ calyx krater, depicting the death of Sarpedon (a son of Zeus), is one of the most famous red-figure works. Winged personifications of Sleep and Death carry the hero’s body from the battlefield while Hermes looks on. The anatomy is rendered with surgical precision, but what lingers is the gravity of the moment—the transcendence of myth through naturalistic form. It is art in full command of both realism and metaphor.

Daily Life on Display

While myth remained a popular theme, Athenian red-figure pottery also turned its gaze inward—to the everyday world of its citizens. Banquets, athletic training, weddings, music lessons, and erotic encounters were all depicted with the same care as divine dramas. A kylix (drinking cup) by the Brygos Painter, for example, might show symposiasts reclining with lyres and wine, surrounded by servants and jesters, their postures loose and gestural. These scenes were not merely decorative; they reflected the habits and values of the elite, the rhythms of ritualized leisure, and the codes of gender and class.

Women, though largely confined to domestic spaces in Athenian society, also appeared frequently on vases. Scenes of women at the loom, preparing for weddings, or honoring the dead reveal both the expectations and reverence tied to female roles in the household and religious life. The white-ground lekythoi (funerary oil jars) often depicted quiet, mournful scenes of women at tombs—delicate, haunting, and deeply human.

The Vase as Object and Storyteller

These vessels were not passive objects. They were used, broken, buried, and treasured. Their shapes were specialized: amphorae for storage, kraters for mixing wine and water, kylikes for drinking, lekythoi for perfumes and funerary rites. The form of each pot influenced its decoration. Kylikes, for instance, often featured interior tondo scenes that were only revealed as one drank—creating surprise, humor, or reflection.

The export of Athenian pottery across the Mediterranean also turned it into a kind of artistic currency. Athenian red-figure wares have been found from Spain to the Black Sea, often in elite tombs. Foreigners valued them for their technical brilliance, but the imagery they carried also helped spread Athenian myths, aesthetics, and cultural values abroad.

The Painters: Known but Anonymous

Remarkably, hundreds of vase painters signed their work—either with epoiesen (“made it”) for the potter, or egraphsen (“painted it”) for the painter. This record has allowed scholars to identify and group works by individual hands and workshops. Still, many painters remain anonymous and are known only by their most famous piece—hence names like the Berlin Painter, the Achilles Painter, or the Pan Painter.

This mixture of fame and anonymity is part of the unique character of Athenian ceramic art: a space where individual expression flourished within the constraints of a collaborative and commercial craft.

Athenian vase painting offers an unparalleled visual archive—not just of gods and heroes, but of gesture, posture, attire, and attitude. These painted scenes give voice to a society that valued storytelling, idealized its myths, and documented its rituals. In them, the lines between art and object, image and function, dissolve.

Athens was not only a city of temples and statues—it was a painted city, alive with narrative, encoded in clay, and passed from hand to hand across time.

Hellenistic Athens: Legacy and Adaptation in a Cosmopolitan Era

By the late 4th century BCE, Athens was no longer the undisputed center of the Greek world. The rise of Macedon under Philip II and Alexander the Great shifted political and cultural gravity northward, while the conquest of Persia expanded Hellenic influence far beyond its Aegean roots. Yet, Athens remained a vital and symbolic heart of Greek identity. As power decentralized, art diversified—and in this new, more interconnected world, Athens adapted. The Hellenistic period (323–31 BCE) did not diminish Athens as an artistic city; rather, it gave the city new roles: as curator of its own classical legacy, participant in wider stylistic currents, and cradle of humanistic expression more focused on emotion, individuality, and complexity.

The Aftermath of Empire

Alexander’s death in 323 BCE unleashed a scramble for power across the territories he had conquered. Athens, initially resistant to Macedonian domination, found itself politically constrained but culturally resilient. Despite being under the sway of Hellenistic rulers—first the Antipatrids, later the Ptolemies and others—Athens retained its prestige as an intellectual and artistic beacon.

It is telling that many of the new Hellenistic cities, from Alexandria to Pergamon, styled themselves after Classical Athens. They built stoas, gymnasia, theaters, and agoras. They commissioned statues in the Attic style. Even as the locus of innovation moved elsewhere, Athens was the standard against which all other Hellenistic urban centers measured themselves.

The Changing Face of Sculpture

One of the hallmarks of Hellenistic art is emotional expressiveness, a departure from the restrained idealism of the Classical period. This shift did not bypass Athens. Sculptors began to explore new subjects: elderly bodies, laughing children, dramatic gestures, and intimate moments. Statues were no longer just about perfection—they were about presence, character, and story.

Take, for instance, the Old Market Woman or Drunken Satyr types: often considered products of broader Hellenistic trends, yet popular in Athenian workshops. These figures are contorted, expressive, sometimes grotesque. They invite empathy, curiosity, even discomfort. Where the Classical nude had been about the ideal, the Hellenistic nude explored the real—even the vulnerable.

Portraiture also flourished. Philosophers, orators, and civic leaders were increasingly memorialized in lifelike busts. The portrait of Demosthenes, for example, reflects a sober realism, capturing not only the man’s visage but also his intellectual gravity and internal tension. This was sculpture as psychological portrait, revealing the individual behind the public role.

Architecture and Civic Renewal

In response to both decline and ambition, Athens embarked on several civic building projects during the Hellenistic period, many funded by foreign benefactors eager to associate themselves with the cultural capital of the Greek world.

The Stoa of Attalos, built by King Attalos II of Pergamon in the 2nd century BCE, is one such example. A grand, colonnaded walkway in the Agora, it combined utility with symbolism. Its size and elegance spoke to Athens’ enduring importance, while its donor made a visible claim to cultural kinship. The reconstructed stoa, now part of the Agora Museum, stands as a rare and instructive survival of Hellenistic civic architecture in Athens.

The Theater of Dionysus was also renovated and expanded during this time, cementing Athens’ role as a theatrical and dramatic hub, even as playwrights like Menander ushered in the subtler, domestic style of New Comedy. Art and performance, public life and leisure, were still deeply intertwined.

The Intellectual City

Art in Hellenistic Athens must also be understood in the context of its intellectual milieu. Though eclipsed by Alexandria as a scientific center, Athens remained a philosophical powerhouse. The Lyceum, founded by Aristotle, and the Academy, founded by Plato, continued to attract students from across the Mediterranean. Stoicism, Epicureanism, and Skepticism all took root in the city’s shaded groves and colonnades.

This intellectual climate shaped artistic taste. While the broader Hellenistic world often embraced spectacle and sensuality, Athenian art retained a degree of reserve and introspection. This was a city where aesthetics were debated, not just admired—where beauty was still linked to ethics, proportion to virtue.

Funerary and Domestic Art

Athenian graves of the Hellenistic period continued to feature sculptural reliefs, but the emphasis shifted. Scenes of domestic tenderness—parents and children, spouses, solitary thinkers—suggest a growing focus on the private sphere. Art was no longer purely public performance; it was increasingly a site of personal memory and reflection.

Mosaics began to appear in Athenian homes, often depicting Dionysian scenes or marine life, rendered with meticulous detail. These domestic artworks, though more modest than temple sculpture, reflect the diffusion of visual sophistication into everyday life. Art was not just in the polis—it was in the oikos.

Athens and the Roman Gaze

As Rome rose in power and influence, Athens became something new: not a hegemon, but a cultural touchstone. Wealthy Romans flocked to the city as students, tourists, and art collectors. Athenian workshops produced countless copies of Classical masterpieces for Roman villas. The city’s sculptors, potters, and architects became both conservators and exporters of their own heritage.

The Roman appetite for Classical art—especially the style of 5th-century Athens—further crystallized Athenian identity as the cradle of ideal form. Ironically, in order to survive in the Hellenistic and Roman worlds, Athens became a kind of open-air museum of itself. But this was not passive preservation; it was strategic curation.

The Hellenistic period in Athens is a study in resilience and reinvention. Though its political power waned, its artistic and intellectual life remained remarkably vibrant. Artists navigated a cosmopolitan world while anchoring themselves in a classical past. They expanded the emotional range of sculpture, adapted architectural forms to new donors and audiences, and helped define a cultural brand that would endure through centuries of occupation and emulation.

Athens, in the Hellenistic age, was no longer simply a creator—it was a custodian, a commentator, and a connoisseur of its own legacy.

Roman Athens: A Cultural Colony and Curated Past

By the time the Romans set their sights on Greece in the 2nd century BCE, Athens was no longer a dominant city-state but a revered symbol—a living monument to the ideals of Classical antiquity. For Rome, conquering Athens was not just a military act; it was an act of cultural inheritance. The Romans saw themselves as the heirs to Greek civilization, and no Greek city captured that legacy more potently than Athens. In the centuries that followed, Athens became both a provincial city and a global intellectual center—a place where past and present merged in stone, bronze, and thought.

Under Roman rule, Athenian art took on new roles: it preserved the Classical ideal, taught Roman patrons and students how to see, and quietly adapted to the aesthetic desires of its imperial overlords. This was not a time of decline, but of transformation. Athens, long accustomed to political subjugation and cultural reinvention, became a curator of its own past, even as it remained artistically and intellectually active.

The Roman Gaze: Athens as Memory and Museum

To the Romans, Athens was a city of mythic prestige. It was where Socrates had walked, where the Parthenon gleamed, where the visual embodiment of rational order had been perfected. For wealthy Romans, especially in the late Republic and early Empire, Athens was both pilgrimage site and educational destination.

Figures such as Cicero, Hadrian, and Emperor Augustus admired the city deeply. They came to Athens to study rhetoric, philosophy, and art. Roman elites filled their villas with copies of Athenian sculpture—the Discobolus, the Doryphoros, the Venus of Knidos. These replicas, often made in Athenian workshops, preserved works that would have otherwise been lost and disseminated the Athenian aesthetic across the empire.

This process of replication made Athens a kind of artistic archive. Its workshops specialized in reproducing the masterpieces of the Classical period, becoming agents in the invention of “Classical art” as a fixed, timeless category.

Imperial Benefaction: Building Rome into Athens

Though the city had suffered under earlier Roman interventions—most notably during Sulla’s sack of Athens in 86 BCE, which caused enormous destruction—the Augustan and Hadrianic periods ushered in a wave of renewal. Roman emperors, keen to associate themselves with the cultural prestige of Athens, funded major building projects that reshaped the cityscape.

Emperor Hadrian, a committed philhellene, left the largest mark. He saw himself not only as a patron but as a restorer of Greek greatness. His contributions included:

- Hadrian’s Library (built circa 132 CE): An ornate cultural complex with reading rooms, lecture halls, and a central courtyard surrounded by columns. It stood as a symbol of Roman-Athenian synergy, housing texts and serving as a center for philosophical discourse.

- The Olympieion (Temple of Olympian Zeus): Begun in the 6th century BCE but left unfinished for centuries, it was completed by Hadrian, who placed his own statue beside that of Zeus inside the temple. This act of self-association with divine power mirrored his ambitions as a pan-Hellenic ruler.

- The Arch of Hadrian: A triumphal arch near the Olympieion, inscribed with a telling dual dedication. On one side, it reads, “This is Athens, the ancient city of Theseus”; on the other, “This is the city of Hadrian, not of Theseus.” It was both a homage and a rebranding—Athens as Roman masterpiece.

These structures exemplified Roman artistic style—grand, axial, symmetrical—yet were executed with Athenian craftsmanship and often incorporated Classical Greek motifs. The result was a hybrid visual language: part reverence, part reinvention.

Sculpture: Between Copy and Originality

The Roman era saw a complex interplay between reproduction and innovation in sculpture. While many Athenian workshops specialized in Roman copies of Classical works, others produced original pieces that reflected contemporary Roman tastes—more dramatic expressions, individualized portraits, and mythic scenes rendered with a touch of theatricality.

One important genre was philosopher portraiture. Busts of Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and Zeno adorned public spaces and private homes, often reimagined with Roman verism—deep lines, furrowed brows, the marks of wisdom and labor. These were not just icons of the past; they were role models, visual guides for Roman intellectuals and politicians.

Funerary art also evolved. Roman-style sarcophagi, adorned with reliefs of mythological scenes—Achilles, Dionysus, Eros and Psyche—began to appear in Athens. These works bridged Greek myth with Roman funerary customs, allowing elite Athenians and Romans alike to see themselves within the mythic continuum.

Painting and Domestic Art

Though few wall paintings survive from Roman Athens, literary sources and comparative evidence from Pompeii and Delos suggest that homes and public buildings were increasingly decorated in the Roman style: illusionistic architectural scenes, mythological tableaux, and still lifes. These paintings would have occupied the walls of elite Athenian villas, blending Classical themes with Roman interior design.

Meanwhile, mosaics continued to flourish. Floors from Roman-era Athens display geometric motifs, marine creatures, and mythological scenes—sometimes with Latin inscriptions, sometimes with Greek. These works exemplify the cultural hybridity of the time: Athens was both proud of its heritage and adept at absorbing new visual vocabularies.

Religion, Ritual, and Continuity

Despite Roman domination, the Athenian religious landscape remained remarkably resilient. Temples continued to function, rituals like the Panathenaia persisted, and cultic art retained many Classical forms. However, Roman emperors—especially Hadrian—were often inserted into these traditions. Hadrian was worshipped in Athens not just as a benefactor but as a god, and his images appeared in temples alongside traditional deities.

This religious blending extended into visual culture. Reliefs and statues might depict Athena alongside Roman eagle standards, or Dionysus in a Bacchic frenzy more typical of Roman sarcophagi than Greek sanctuaries.

The City as Classroom

By the 2nd century CE, Athens was a major destination for Roman students of rhetoric and philosophy. Schools like the Academy and the Lyceum were revived under Roman patronage. The city’s artistic atmosphere played a key role in this educational mission. Students were immersed not only in texts and arguments, but in a built environment that embodied the ideals they studied.

In this context, art became didactic. Statues were not just beautiful—they were instructive. They were manifestations of ethical and civic models: the courageous hero, the wise thinker, the just ruler. The visual and intellectual landscapes were deeply intertwined.

Under Roman rule, Athens was no longer at the cutting edge of artistic innovation—but that wasn’t its role anymore. Instead, it became a curated city, a museum of Classical ideals, a proving ground for Roman philhellenism. Its workshops preserved the styles and techniques of its golden age, even as they responded to the demands of a new imperial audience. Its monuments honored the past while speaking in the idioms of empire.

Athens became, in essence, the visual conscience of Rome—a reminder of what civilization could and should look like.

Byzantine Athens: From Pagan Temples to Christian Icons

By the time the Roman Empire shifted its spiritual allegiance from the old gods to Christianity, Athens—long the guardian of Classical aesthetics and polytheistic grandeur—faced a dramatic transformation. The art that once celebrated Olympian deities and heroic mortals was slowly redirected toward a new visual language: one of saints, icons, and the transcendent divine. In the Byzantine period (roughly 4th to 15th centuries CE), Athens became a quieter city on the margins of empire. Yet its artistic life did not end. Instead, it adapted—layering Christian meaning atop pagan forms, reusing ancient materials for new churches, and developing a distinctly Eastern Orthodox artistic identity rooted in spiritual abstraction, sacred geometry, and devotional intimacy.

The End of Pagan Art and the Rise of the Icon

The Christianization of the empire, especially after Constantine’s Edict of Milan (313 CE), gradually led to the suppression of pagan cults and the reappropriation of their artistic infrastructure. In Athens, as elsewhere, this transition was both abrupt and layered. Temples were shut down or repurposed; rituals were outlawed, but their aesthetic frameworks persisted. The very bones of ancient Athens—its marbles, columns, and friezes—were reused in Christian churches, a practice known as spolia.

The Parthenon itself was converted into a Christian church by the 6th century CE, dedicated first to the Virgin Mary. Its pagan iconography was reinterpreted through Christian typology. Athena, once the embodiment of wisdom and war, became Mary, Mother of God—protector of the city in a different spiritual register. The sculptures were mutilated or covered, yet the structure remained central to religious life.

Church Building and Athenian Adaptation

Byzantine Athens never regained the political or artistic prominence of its Classical or even Roman past, but it became an important religious and monastic center. A number of small but architecturally refined churches were built from the 9th through 12th centuries, reflecting the Middle Byzantine period’s flourishing of religious art.

The most notable examples include:

- The Church of the Holy Apostles in the Ancient Agora (10th century), a small cross-in-square structure with exquisite brickwork and later frescoes.

- Kapnikarea (11th century), built on the ruins of a classical temple, stands today in the heart of modern Athens. It features intricate stonework and layers of fresco painting added in subsequent centuries.

- Daphni Monastery, located just outside the city, houses some of the finest Byzantine mosaics in Greece, including a towering Christ Pantokrator in the central dome—calm, omniscient, and rendered in shimmering tesserae of gold, blue, and ochre.

These buildings speak a new artistic language: one of divine order rather than human perfection, inward contemplation rather than civic pride. The decoration turned from sculpture to mosaic and fresco, media better suited to ethereal, unchanging truths. Christ, the Virgin, apostles, and martyrs replaced Athena, Herakles, and Dionysus as the central visual figures—but the desire to make the divine visible remained.

Aesthetic Shifts: From Form to Spirit

Whereas Classical art celebrated movement, anatomy, and ideal form, Byzantine art emphasized abstraction and symbolic meaning. Figures were front-facing, flattened, and hieratic. The focus was not on individual likeness but spiritual presence. Gold backgrounds obliterated natural space, situating saints and holy figures in an eternal, heavenly realm. Proportion was inverted to emphasize theological rather than physical realities.

And yet, Byzantine Athens never completely severed its ties to antiquity. The geometric and architectural clarity of Classical design persisted in the symmetrical plans of Byzantine churches. Columns and capitals from ancient temples reappeared in Christian naves. Even the aesthetics of light—so central to both Classical temples and Byzantine mosaics—remained a through-line.

Icons and the Culture of Devotion

By the later Byzantine period, icons—painted panels of Christ, the Virgin, and the saints—became central to devotional life. Though the Iconoclastic Controversy (8th–9th centuries) led to the destruction of many images, by the 10th century, icon painting had become a defining art form of Orthodox Christianity.

In Athens, local workshops produced portable icons for churches and private devotion. These images followed strict stylistic conventions but also bore the touch of local hands. The eye contact between the icon and the viewer created a sacred relationship, collapsing the distance between heaven and earth. Unlike the narrative scenes of ancient vase painting or the dramatic gesture of Hellenistic sculpture, icons communicated through stillness and gaze.

These were not just images to admire—they were objects to venerate. Art had moved from the public square to the private soul.

Ruins and Revival: Athens in the Byzantine Imagination

Even as it became a modest provincial city, Athens retained a symbolic weight. Byzantine writers and pilgrims often described it with reverence, as the birthplace of philosophy and rhetoric—even as they lamented its faded grandeur. The physical ruins of antiquity, still visible in the Athenian landscape, became sites of Christian contemplation and reinterpretation.

One notable moment came in the 11th century, when Michael Psellos, a Byzantine scholar, praised the city’s past while celebrating its Christian transformation. To him, Athens was not lost—it had been transfigured. Its wisdom now served a higher truth.

The Byzantine era in Athens marked a profound reorientation of art—from civic display to sacred encounter, from human idealism to divine transcendence. The transition was not simply a rupture, but a palimpsest. Pagan temples became churches; gods became saints; marble was turned to mosaic. Athens learned, once again, to adapt—to reshape its artistic language while holding onto its structural and symbolic core.

This chapter is essential to understanding Athenian art as a continuum. It reminds us that Athens has always been a city of conversions—not just spiritual, but visual and material, where every new faith or empire found a way to write itself upon the stones of the past.

Ottoman Athens: Decline, Continuity, and Cultural Layering

When the Ottoman Turks captured Athens in 1458—just five years after the fall of Constantinople—it marked another dramatic chapter in the city’s long history of conquest and transformation. To many European observers, this era was seen as a period of cultural decline, when the glories of Classical and Byzantine Athens lay buried under layers of foreign rule. But this interpretation misses a more nuanced truth. Ottoman Athens was not a city frozen in decay—it was one shaped by continuity, adaptation, and complex cultural layering.

Though diminished in stature, Athens remained a living, breathing urban center during the nearly four centuries of Ottoman rule (1458–1833). Its art and architecture reflected the tensions and syntheses of an imperial Islamic administration governing a Christian Orthodox population amid the monumental debris of pagan antiquity. It was a city of mosques and churches, minarets and domes, Byzantine chapels tucked between Ottoman fountains and repurposed classical ruins.

The Conquest and Its Immediate Impact

The Ottoman conquest of Athens was relatively bloodless, negotiated between local elites and Sultan Mehmed II. The Sultan, himself a patron of learning and admirer of antiquity, spared much of the city from destruction. Yet, the Ottoman administration quickly reoriented Athens toward Islamic governance and aesthetics.

The Parthenon, which had served as a Christian church for nearly a millennium, was converted once again—this time into a mosque. A minaret was added at its southwest corner, and its pagan and Christian sculptures were further mutilated or obscured. This act, while symbolically powerful, followed a long-standing pattern in Athens: the reuse and reinterpretation of sacred space. The Parthenon had now served three religions over two millennia—pagan, Christian, and Muslim—each layering its own theology and iconography onto the bones of the city.

Art Without Monuments?

The Ottoman Empire, especially in its earlier centuries, emphasized imperial Istanbul as its cultural and artistic core. Athens, by contrast, became a provincial town—a regional capital within the larger structure of Ottoman Rumelia (the Balkans). As a result, it produced relatively few grand architectural statements.

Yet art did not disappear. Rather, it shifted into smaller, more modest forms. Ottoman architecture in Athens included:

- Mosques, such as the Fethiye Mosque (built c. 1458–60 to celebrate Mehmed II’s conquest), located in the Roman Agora and recently restored. These buildings often utilized spolia—reclaimed columns and capitals from ancient temples—creating a physical dialogue between Islamic design and Classical forms.

- Fountains and baths, often inscribed with Arabic calligraphy, brought elements of Ottoman daily life and aesthetics into the city. These were utilitarian but elegant, expressions of public charity and civic identity.

- Houses in the Ottoman style, featuring wooden balconies, inward-facing courtyards, and finely carved interiors. Though few remain today, they were once a defining feature of the Athenian urban fabric.

This was a different kind of art—one grounded in domestic life, in pattern rather than monument, in the repetition of tilework, textiles, and inscriptions. It was not the art of marble and heroism, but of shadow, texture, and daily ritual.

Christian Art in an Islamic City

Though under Islamic rule, the majority of Athens’ population remained Christian Orthodox. The Ottoman millet system allowed religious minorities a degree of autonomy, and churches continued to function—though new construction was often limited.

Byzantine chapels from earlier centuries were maintained, and in some cases, new churches were discreetly built or renovated. Inside, icon painting flourished, especially in the late Ottoman period. These icons preserved older Byzantine styles but also absorbed baroque and western influences brought by traveling artists or imported prints.

Artisans painted with egg tempera on wood, creating luminous figures of saints, Christ Pantokrator, and the Virgin. These icons, often unsigned and produced in workshops, became central to both personal devotion and communal identity. In a world where Orthodox Christians were politically subordinate, religious art became a subtle means of resistance and continuity.

One of the most important centers for this tradition was Mount Athos, but Athenian workshops—especially during the 17th and 18th centuries—also contributed to the regional iconographic vocabulary.

Travelers and Antiquarians: The Western Gaze

During the Ottoman period, Athens became a destination for European travelers, antiquarians, and artists who were drawn by the ruins of antiquity and the romance of the East. Figures like James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, who visited in the mid-18th century, documented the city’s monuments with obsessive precision. Their Antiquities of Athens (1762 onward) helped shape the neoclassical revival in Europe and reframed Athens as a site of lost grandeur awaiting rescue.

At the same time, their writings—and those of later travelers like Lord Byron—frequently dismissed Ottoman Athens as degraded, a fallen world obscured by foreign rule. This orientalist lens both romanticized and distorted the lived reality of the Ottoman city.

Their sketches and journals, however, remain valuable records—capturing what was still standing before the depredations of war and neglect took their toll.

Tensions and Transformations

As Greek nationalism grew in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the art and material culture of Ottoman Athens began to shift. Churches were increasingly adorned with national symbols, like the double-headed eagle of Byzantium, and liturgical art became a site of resistance and identity. Secret schools, folk embroidery, and church frescoes began to encode patriotic as well as spiritual messages.

This rising consciousness culminated in the Greek War of Independence (1821–1830), during which Athens changed hands multiple times and suffered severe destruction. The Parthenon, which had been used as an Ottoman munitions depot, was catastrophically damaged when it exploded during a Venetian bombardment in 1687—a wound that symbolically echoed through the nationalist imagination.

Ottoman Athens was not a void between golden ages, but a palimpsest—a city of layers and negotiations. Its art was quieter, more intimate, rooted in ritual and memory. It expressed itself in prayer niches and icons, in the geometry of fountains and the shadow of minarets. It bore the weight of past greatness while accommodating the realities of imperial administration, religious pluralism, and survival.

In the Ottoman period, Athens learned how to carry its past without always displaying it—how to make art in the margins, and how to keep faith, quite literally, in its visual forms.

Neoclassical Revival and the Making of a Modern Greek Identity

When Athens was declared the capital of the newly independent Greek state in 1834, it was a city of ghosts and fragments—half-ruined temples, Ottoman houses, Byzantine chapels, and scattered memories of ancient grandeur. But for the emerging Greek nation, these fragments were not just remnants—they were foundations. The art and architecture of 19th-century Athens became a conscious act of resurrection: a Neoclassical revival not only in style but in spirit, one that aimed to craft a modern identity rooted in the visual language of ancient glory.

This was more than aesthetic preference. It was cultural strategy. The new Greek state needed symbols—images, monuments, and buildings—that could assert continuity with the Classical past, align with European expectations, and assert national legitimacy. Art became a vehicle of rebirth, a means of transforming a former Ottoman province into the symbolic heart of a Western, modern nation.

Athens as a Capital of Memory

The selection of Athens as capital was itself an artistic and ideological decision. The city was relatively small and underdeveloped compared to other options, but it held unmatched symbolic power. To European philhellenes and Greek intellectuals alike, Athens represented not just antiquity, but the very idea of civilization.

The 19th-century Athenian landscape was reshaped with this in mind. Ruins were cleaned, excavated, and re-presented as national heritage. Ottoman-era buildings were often demolished or neglected, while ancient and early Christian structures were preserved. This selective archaeology served a political and cultural agenda: to foreground the Classical while marginalizing the intervening layers of Byzantine and Ottoman history.

The Neoclassical Aesthetic: Ancient Forms for a New Nation

Inspired by the European Neoclassical movement—already in full swing since the late 18th century—Greek architects, often trained in Munich, Berlin, or Paris, began designing buildings that emulated the forms of antiquity. Columns, pediments, and symmetry returned to the city’s skyline—not as archaeological fragments, but as freshly built declarations of national identity.

Three monumental projects in central Athens epitomized this movement and are often referred to collectively as the “Athenian Trilogy”:

- The University of Athens (1837–1864), designed by Christian Hansen, featured Ionic columns and a richly decorated facade that positioned learning within the visual tradition of the Academy and Lyceum.

- The Academy of Athens (1859–1885), designed by Theophil Hansen (Christian’s brother), took the form of a Classical temple, complete with allegorical statues of Athena and Apollo flanking the entrance.

- The National Library of Greece (1888–1903), also by Theophil Hansen, was built in marble with a monumental staircase reminiscent of ancient stoas.

These buildings didn’t just recall the past—they reanimated it. For a people emerging from centuries of foreign domination, Neoclassicism offered a clear visual declaration: we are the heirs of Pericles and Plato.

Romanticism and Philhellenism: The Western Imagination

Western European artists and intellectuals had long been enchanted by Greece, often filtering it through the lens of Romanticism. Painters like Eugène Delacroix, whose “Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi” (1826) became iconic, used allegory and emotion to depict Greece as a noble but suffering figure—beautiful, tragic, and reborn through struggle.

This philhellenic sentiment also shaped the tastes of foreign patrons and collectors. The Elgin Marbles, controversially removed from the Parthenon in the early 19th century and housed in the British Museum, were celebrated in London as icons of aesthetic purity. Meanwhile, travelers continued to flock to Athens, sketching ruins and imagining themselves in the footprints of Socrates or Pericles.

Such foreign interest encouraged the Greek state to focus its artistic and archaeological energies on antiquity. Museums were founded, excavations increased, and classical art was reproduced, taught, and canonized.

Painting the Nation: The Munich School and Greek Historical Art

In this context, a new generation of Greek painters emerged—many of whom studied in Munich under German academic painters and became known as the Munich School. Their work combined academic technique with national themes, depicting scenes from the Greek War of Independence, daily rural life, and imagined moments from ancient history.

Key figures included:

- Theodoros Vryzakis, whose historical paintings celebrated the revolution and national heroes in grand, Romanticized style. His “The Reception of Lord Byron at Missolonghi” (1861) tied Classical admiration to modern political myth.

- Nikolaos Gyzis, who turned increasingly toward allegorical and religious subjects, creating haunting, richly symbolic compositions that echoed both Byzantine iconography and German Romanticism.

- Nikiphoros Lytras, who combined portraiture with ethnographic sensitivity, depicting peasants, students, and everyday life with quiet dignity.

These artists helped shape a visual narrative of Greek identity—one that merged ancient pride with Christian resilience and rural authenticity.

Monumental Sculpture and National Memory

Public sculpture also played a vital role in visualizing the new Greek state. Statues of heroes of the revolution—Kolokotronis, Karaiskakis, and others—rose in city squares, usually in heroic, equestrian poses. Alongside them, busts of ancient philosophers, poets, and generals were installed on university grounds, in parks, and around archaeological sites.

This dual commemoration—of ancient greatness and modern liberation—created a continuous visual line between past and present, embedding patriotic ideology in the very fabric of the city.

Domestic Architecture and the “Greek House”

Neoclassicism also entered domestic life. Wealthier Athenian homes adopted elements of Classical design: painted friezes, columned porticoes, and pedimented facades. These houses often blended the symmetry of ancient temples with the intimate scale of bourgeois life, creating a hybrid aesthetic of middle-class classicism.

Even modest homes incorporated neoclassical motifs—often mass-produced or painted onto plaster facades—democratizing the aesthetic and making the past part of everyday living.

The Neoclassical revival in 19th-century Athens was more than an aesthetic preference. It was a deliberate cultural project, a visual language of nation-building that drew on antiquity to craft a new modern identity. Through architecture, painting, sculpture, and urban design, Athens was reimagined not as a faded ruin, but as the reawakened heart of Western civilization.

This period cemented many of the visual codes we still associate with Greece today: the white column, the heroic figure, the marble cityscape. It also laid the groundwork for future tensions—between past and present, between cultural heritage and lived reality, between art as myth and art as critique.

Contemporary Athens: Postmodernism, Street Art, and Crisis Aesthetics

Athens today is not merely a city of antiquities—it’s a laboratory of contemporary art, where history collides with urgency. The marble columns and neoclassical facades remain, but they stand beside spray-painted slogans, guerilla installations, and experimental performance spaces. Over the last few decades, particularly since the Greek debt crisis of the 2010s, Athens has emerged as one of Europe’s most compelling and unpredictable art scenes. Here, contemporary artists engage not only with global movements but also with the city’s own long, layered past—reframing it, defacing it, and recharging it.

This is the age of postmodern Athens: fragmentary, ironic, deeply political, and defiantly alive.

From the Margins to the Center: Athens in the Post-Crisis Imagination

For much of the 20th century, Athens remained on the periphery of the contemporary art world. Its major modernist voices—like Yannis Tsarouchis, Takis, or Chryssa—were respected but often lived abroad. The city lacked the institutional gravity of Paris, London, or Berlin. But that began to change after 2008, when the global financial crisis triggered a decade of austerity in Greece.

What followed was an explosion—not only of protests and political upheaval but of artistic experimentation. Vacant buildings became studios. Graffiti turned into muralism. Institutions adapted or collapsed. Amid economic collapse, a kind of creative lawlessness took hold, drawing comparisons to post-wall Berlin or 1980s New York.

In this context, Athens became a destination—for artists fleeing the high costs of northern Europe, for curators seeking authenticity, and for a new generation of Greek creators rethinking what art could do in public space.

The Rise of Street Art and Urban Intervention

Nowhere is the contemporary art of Athens more visible—or more raw—than on its walls. The neighborhoods of Exarchia, Metaxourgeio, and Psiri are covered in sprawling murals, stencils, wheat-paste posters, and political graffiti. This is not street art as decoration—it is a mode of discourse.

Artists like WD (Wild Drawing), INO, and Bleeps.gr have gained international attention for large-scale works that tackle themes of surveillance, inequality, and national identity. INO’s piece “Snowblind”—a blindfolded statue-like figure painted on a building in Omonia—became an emblem of the social trauma inflicted by austerity and corruption.

Graffiti, long viewed as vandalism, became a dominant visual form—equal parts protest, poetry, and psychological map. Slogans like “No Justice, No Peace”, “Tourists Go Home”, or “We Are the Crisis” speak to a city in constant negotiation with itself.

The city’s ancient and neoclassical architecture becomes part of this dialogue. Artists deface, protect, or ignore the ruins—depending on their message. In Athens, history is not off-limits. It’s part of the fight.

Institutions in Flux: Museums, Biennials, and Alternatives

Despite its reputation for DIY rebellion, Athens also developed a more formal contemporary art infrastructure in recent decades. The National Museum of Contemporary Art (EMST)—long in limbo—finally opened in the former Fix brewery in 2020, presenting exhibitions of Greek and international artists. Its architecture, raw and industrial, reflects the spirit of adaptation and survival.

In 2017, Athens hosted Documenta 14, the influential German art exhibition held for the first time outside its usual Kassel base. Titled “Learning from Athens,” the show used the city as both backdrop and case study—exploring themes of colonialism, debt, and southern resilience. While its reception was mixed, Documenta solidified Athens’ status as a contemporary art capital—not in the polished, market-driven sense, but as a site of ethical and aesthetic provocation.

Alongside these institutions, dozens of artist-run spaces, collectives, and pop-up galleries flourish. Spaces like State of Concept, Snehta Residency, and Atopos CVC foster dialogue between Greek and international artists, curators, and thinkers. These platforms often blend installation, theory, and activism—bridging the local and the global.

Performance, Protest, and the Politics of the Body

In Athens, contemporary art often spills into performance and protest. Artists like Dimitris Papaioannou, known for his choreography in the 2004 Olympics and post-human stage works, explore the body as mythic and vulnerable terrain. Others, like Lina Theodorou, use performance to critique surveillance, nationalism, and gender roles.

Public squares, abandoned buildings, and even archaeological sites become stages. In some cases, protests themselves are choreographed spectacles—with banners, chants, and symbolic gestures forming living artworks. The line between activism and art is porous.

This fusion is rooted in a long Greek tradition of political theatre and philosophical inquiry. But in the 21st century, it becomes more urgent: a way of reclaiming space, asserting visibility, and confronting power.

Revisiting Antiquity with Irony and Intimacy

One of the defining features of contemporary Athenian art is its relationship to antiquity. Rather than treating the past as sacred, many artists engage with it critically or playfully. They quote, remix, and subvert Classical imagery to interrogate its meanings.

Photographer Yiorgos Kordakis reimagines ancient statues through digital distortion. Video artist Eva Stefani places everyday Athenian life in dialogue with ancient myths. Artist Daphne Iliadi creates minimalist works that echo ancient votives but speak to modern alienation.

These gestures reveal a postmodern impulse: to historicize the ruins, but also to humanize them. Instead of idealizing the past, contemporary Athenian artists ask, What does it mean to live among ruins? How do we make art when our history is a brand, a burden, and a myth all at once?

Migration, Memory, and the Mediterranean Now

Athens is also at the crossroads of the refugee crisis, the climate crisis, and the housing crisis. These intersecting challenges have become key themes in recent art. Installations address displacement, maps are redrawn through migrant journeys, and temporary shelters become sculptural sites.

Artists like Georgia Sagri explore care and vulnerability in performance. Collectives like Chto Delat and Filopappou Group create socially engaged works that include migrants and precarious communities in their creation. Here, contemporary art is not just commentary—it’s infrastructure, pedagogy, and solidarity.

In contemporary Athens, the past is never far—but it is not a prison. It is a resource, a provocation, and sometimes a shadow. The artists of this city don’t simply imitate their ancestors; they argue with them, laugh at them, and, occasionally, ask for guidance.

What emerges is an aesthetic of survival—improvised, layered, deeply engaged. From ruins to resistance, marble to spray paint, Athens continues to reinvent what it means to make art in a city where every surface remembers.

Archaeology as Art: Museums, Ruins, and the Curation of Memory