The oldest artworks in Saitama are silent, brittle, and buried—yet they speak across millennia with astonishing force. Long before calligraphy, castles, or sculpture parks, the region’s artists molded clay into strange, compelling forms that mingled the spiritual with the sensual. The soil of Saitama is rich with relics from the Jōmon period (c. 14,000–300 BC), when hunter-gatherer communities built no cities, spoke no known written language, and yet created some of the most intricate ceramics the world had seen by that time. These early objects—figurines, fire pots, and ritual vessels—lay the foundation for any serious understanding of Saitama’s artistic history. They offer not only a record of aesthetic choices but a glimpse into an ancient cosmology.

Unearthing the Dōgu: Ceramic echoes from ancient settlements

In the early 20th century, Japanese archaeologists began excavating what would become known as the Kamikuroiwa site in Saitama’s Hiki District. The ground gave way to the unmistakable silhouette of a dōgu—a Jōmon-era clay figurine with exaggerated features, wide hips, and hollow eyes. These dōgu are unlike anything in Chinese or Korean Bronze Age art. Found in dozens of Saitama locations such as Kasukabe, Kumagaya, and Hanno, they reveal a kind of local ritual culture that was less about dominance and more about fertility, protection, or the supernatural.

Dōgu from Saitama often show signs of intentional breakage, a clue that they may have been used in ritual destruction—a symbolic shattering meant to endow a harvest, bless a birth, or banish misfortune. Unlike Egyptian statuary designed to last for eternity, these figures were made to be destroyed. That aesthetic—the idea that art need not be permanent to be powerful—echoes across Japanese visual culture centuries later, especially in the ephemeral elegance of Edo-era printmaking or the staged decay in contemporary installation work.

Scholars still debate the function of these figures, but in Saitama, they appear most frequently near water sources and burial grounds. Whether they were meant as companions to the dead, offerings to the gods, or guardians of fields remains unknown. But the consistency of their design across different villages hints at a shared religious or magical worldview among Saitama’s prehistoric peoples. One finds recurring motifs:

- Triangular incised patterns across the belly and chest

- Swirling eyes with radiating lines resembling proto-solar imagery

- Flat or broken limbs, often pre-damaged before burial

All of this suggests a worldview deeply concerned with cyclical life, transformation, and the thin veil between human and spirit worlds.

Fire-flame vessels and the Kōnan kiln sites

Beyond figurines, Saitama’s most striking contribution to Jōmon-era art lies in its kaen-doki—”fire-flame” pots with swirling, almost Baroque rims that explode outwards in dramatic undulations. The town of Kōnan, now part of Kumagaya City, has revealed entire kiln fields where these ceramics were likely fired. These vessels served no practical cooking function. Their ornate, asymmetric rims would have made boiling impossible. Instead, they seem made for display or ritual, perhaps linked to seasonal festivals or clan ceremonies.

The flame vessels of Kōnan are not merely decorative. They reflect a central Jōmon tension: the marriage of chaos and control. The bodies of the pots are symmetrical, coiled with painstaking precision, but the rims defy balance, as if pulled outward by invisible energy. The result is a kind of early sculptural dynamism that anticipates much later Japanese avant-garde ceramics. Their visual rhythm—fluid yet fierce—also inspired certain 20th-century Saitama potters who saw in these ancient forms a defiant rejection of Western symmetry.

One such potter was Fujiwara Taku, a midcentury craftsman from Kawagoe who deliberately echoed kaen-doki motifs in his postwar raku ware, describing the old flame pots as “burning prayers frozen in clay.” Though Fujiwara’s statement is poetic, it’s also grounded in archaeological reality: the vessels were almost certainly connected to ritual fire use, as scorch marks inside many excavated pots indicate ceremonial burning, not cuisine.

This blend of sacred function and wild form sets early Saitama ceramics apart from those found in more centralized areas like Nara or Kyoto, where state-sponsored Buddhist aesthetics later reigned. In Saitama, the primal and the personal seem to dominate—community-based, mysterious, and unconcerned with codified doctrine.

Prehistoric aesthetics and modern interpretations

In 1990, the Saitama Prefectural Museum of History and Folklore curated a controversial exhibit titled “Unknown Sculptors of the Earth: Jōmon Art in Saitama.” What made it controversial wasn’t the age of the pieces—many had been unearthed decades earlier—but the curatorial framing, which positioned these anonymous ancient craftspeople as artists in the modern sense, not mere functional craftsmen. The exhibition asked: Can we speak of art without authorship?

This shift echoed larger 20th-century currents in Japanese art scholarship, where the modern tendency to valorize individual genius clashed with Japan’s long-held emphasis on collective, anonymous creation. But in Saitama, the clay itself seemed to demand recognition. The dōgu and flame pots, especially when placed next to contemporary works by local artists, revealed striking continuities:

- Shared organic forms in both ancient and modern Saitama ceramics

- Use of asymmetry and visual rhythm as organizing principles

- Emphasis on tactile surface texture, inviting physical as well as visual engagement

Local artist collectives, particularly in Tokorozawa and Chichibu, began referencing these Jōmon forms in postwar sculpture and pottery. The Jōmon aesthetic, once relegated to museums and textbooks, began to reemerge in civic installations and private studios.

One notable example is the “Earth Memory” project in Higashimatsuyama—a community clay garden where residents sculpt public kilns and fire collaborative vessels in the style of ancient techniques. This reanimation of Jōmon practice isn’t nostalgia. It reflects a broader Saitama ethos: the belief that art belongs not only to galleries and critics but to soil, fire, and ritual.

There’s something quietly defiant about this return to primal forms in the shadow of Tokyo’s steel and glass. It suggests that Saitama’s artistic legacy is not a pale echo of the capital’s grandeur, but a deep-rooted, self-renewing tradition—one that still listens to the voices beneath the ground.

Provincial Splendor: Buddhist Art and the Rise of Temple Patronage

The clang of bells and scent of incense once echoed through the wooded hills and river plains of Saitama, as Buddhist monasteries rose amid rice fields and footpaths. With the spread of Buddhism during the Nara period (710–794 AD) and into the Heian (794–1185), Saitama, though distant from the political center of Kyoto, became a fertile ground for religious art. Temples served not only as places of worship but also as hubs of cultural and visual production, where sculpture, painting, and architecture coalesced in the service of transcendence. While the capital drew the grand commissions, the provinces—especially places like Saitama—produced work marked by intimacy, restraint, and local character.

The Nara influence and Saitama’s early temple art

Buddhism entered Japan formally through the Yamato court in the 6th century, and its early monumental art—heavily influenced by Chinese and Korean prototypes—was concentrated in Nara and later Kyoto. Yet it was the smaller, less centralized regions like Musashi Province (which includes modern Saitama) that offered fertile ground for adapting these forms into something distinct. The earliest Buddhist structures in Saitama appear during the late Nara and early Heian periods, often modest in scale but rich in expressive power.

Archaeological remains from the Kōzōji Temple ruins near Gyōda show early examples of roof tile decoration, including lotus motifs and spiral patterns typical of Nara influence, but executed with a rustic flair. These were not the precision-fired tiles of Tōdai-ji but the product of local kilns working with coarse clay and unsteady molds. The result was a style that felt rooted, almost folkloric.

More striking are the Buddhist bronze fragments found at the Kurohime Temple site in Saitama’s Hiki District. These include pieces of a seated Amida Buddha and bodhisattvas, smaller in scale than court commissions but bearing an emotional softness—rounded cheeks, lowered eyes, hands that seem more hesitant than commanding. Scholars have noted that while the Nara bronzes exude cosmic authority, Saitama’s early Buddhist sculpture often suggests inwardness, a quiet compassion in form.

By the 9th century, itinerant sculptors—many trained in the Nara and Heian capitals—began traveling to outlying regions like Saitama, often patronized by local clans, wealthy landowners, or small Buddhist communities. This patronage created a fusion of high-style iconography with regional sensibilities. The statue of Yakushi Nyorai (the Healing Buddha) at Hoshino Kannondō, for instance, is attributed to this period. Though weathered by time, its proportions echo Kyoto prototypes, while the treatment of the robes and the expression are distinctly provincial—gentler, more human.

These works reflect a key characteristic of Saitama’s Buddhist art: the translation of cosmopolitan religious ideals into local visual dialects. Rather than competing with the grandeur of the capitals, Saitama’s temples offered something more accessible: an art of piety woven into the rhythms of rural life.

Kannon statues at Hoshino and the role of itinerant sculptors

The cult of Kannon, the bodhisattva of mercy, gained particular traction in Saitama between the 10th and 13th centuries. Known for her thousand arms and ability to take on many forms, Kannon became a favored subject in both temple and roadside shrines. Saitama’s Hoshino region, now part of Chichibu, became renowned for its Kannon statues—most notably the “Thirty-three Kannon Route” that still attracts pilgrims today.

These statues, many carved directly into cliff faces or placed in modest wooden halls, reflect the hand of craftsmen whose names have long been forgotten. Unlike the court ateliers of Kyoto, these were likely wandering artisans—skilled but independent, often working alone or in small family units. Their techniques were a blend of Yosegi zukuri (joined woodblock construction) and simpler single-block carvings, depending on the resources available.

One surviving example at Jōrin-ji Temple shows a standing Kannon carved in cypress wood, measuring just under four feet. The figure’s posture is traditional, but the surface treatment reveals a local touch—less emphasis on flowing drapery, more on expressive hand gestures and a serene, contemplative face. The wood is untreated, exposed to the elements, creating a fusion of sculpture and environment. This physical vulnerability became part of the aesthetic itself—a sacred image that ages alongside the world it protects.

What made Saitama’s Kannon imagery distinct was this spiritual accessibility. In contrast to the golden statuary of Kyoto’s Kiyomizu-dera, these Kannon figures invited closeness. They were touched, prayed to, adorned with flowers by farmers and fishermen, not cordoned off in sanctuaries. Over centuries, many of these figures wore down, not from neglect but from devotional interaction—prayer beads rubbed against wooden knees, water offerings poured over the hands, incense burned at their feet.

This intimacy speaks to a deeper truth: in Saitama, religious art was not passive decoration. It was part of the daily exchange between heaven and earth, maintained not by scholars or aristocrats but by ordinary people.

Local beliefs woven into Buddhist iconography

As Buddhism spread through Japan, it merged with older Shinto beliefs, especially in the provinces. In Saitama, this syncretism took visual form in the decoration and symbolism of religious objects. At sites like Chichibu’s Mitsumine Shrine, one sees Buddhist guardian statues placed beside Shinto shishi lions; mountain deities appear alongside bodhisattvas; even temple architecture blurs lines, with pagodas sporting torii-like gates.

Artists in Saitama often incorporated natural motifs that reflected local geography—waves for river spirits, pine branches for local kami, mountain ridges in halo designs. This layering of sacred traditions shows up vividly in mandala paintings from the Kamakura period, several of which have been preserved in regional temple archives. These works depict a world not strictly defined by Buddhist cosmology but one in which Buddhas, ancestors, spirits, and local gods coexisted in a single pictorial field.

An especially vivid example comes from Shōmyō-ji, where a 13th-century painted scroll shows Kannon flanked not by celestial musicians, but by animals—foxes, deer, and birds native to the surrounding forests. The iconography departs from canon, but it’s not arbitrary. It reflects a local belief in nature’s sacred animacy, a worldview in which the Buddhist pantheon was expanded, not replaced, by local spirits.

This fusion of formal Buddhist iconography and regional spirituality is one of Saitama’s most enduring artistic traits. It anticipates similar hybrid aesthetics that later emerge in Edo-period painting and even in modern Saitama art installations that blend folk motifs with sacred themes.

By the late medieval period, Saitama’s temples were no longer simply outposts of capital influence—they had become centers of localized aesthetic and spiritual synthesis. The art produced within and around them was neither purely Buddhist nor purely Shinto, neither high court nor rustic craft. It was something unique: a provincial splendor, rooted in the soil and soul of Saitama.

Warrior Culture and Art: Kamakura to Muromachi Periods

Steel, ink, and stone defined the art of the Kamakura (1185–1333) and Muromachi (1336–1573) periods—and in Saitama, all three came together under the shadow of rising samurai power. As the imperial court’s influence waned and warrior rule hardened across the archipelago, a new aesthetic took hold: disciplined, austere, and grounded in action rather than ornament. The warriors of Saitama—once peripheral to the Kyoto-centered world—now helped shape a distinctive martial culture that blended utility with refinement. This shift is vividly visible in the region’s surviving architecture, arms, sculpture, and painting, where the sword and the sutra often shared space.

Samurai patronage and the aesthetics of discipline

The rise of the Kamakura shogunate, headquartered in nearby Sagami Province (present-day Kanagawa), had a profound effect on Saitama, strategically located just north of the political center. Local warrior families—especially the Ōkouchi, Hatakeyama, and Narita clans—emerged as important landholders and patrons of religious and artistic institutions. Their wealth funded the construction of Zen temples, stone pagodas, and martial training halls, each bearing the imprint of the new order: restrained, unpretentious, and highly symbolic.

One of the most evocative examples of this martial aesthetic is found in the Shōbōji Temple in present-day Kumagaya. Founded by a local retainer in the early 14th century, the temple complex features stone tōrō lanterns with minimal carving, square layouts, and rough-hewn surfaces. These weren’t decorative flourishes but offerings of loyalty and piety. The warrior who carved his name into the base of one lantern did so not as an artist but as a man entrusting his soul to the Dharma.

Even more telling are the portrait sculptures of armored patrons found at temple sites across Saitama. These seated effigies, carved in wood and often coated in black lacquer, show their subjects not in idealized youth but in age and repose—wrinkled, alert, hands resting on their knees. A surviving figure at Ryōshōji Temple in Ageo depicts a retired retainer with grizzled features and a faint smile, robes arranged simply, a sword laid beside him. This realism, a hallmark of Kamakura-period sculpture, emphasized virtue over vanity: to be remembered was not to be beautiful, but to be brave, loyal, and prepared to die.

These warrior patrons also sponsored Buddhist carvings, especially of Fudō Myōō, the wrathful protector deity often favored by samurai. His fierce expression and sword of wisdom aligned with the warrior code of unwavering focus and moral clarity. In Saitama, several wooden statues of Fudō survive in rural temples, their paint faded, their eyes still burning. The iconography is constant: flames rise behind him, a rope binds the unrepentant, and his left hand clutches the vajra, symbol of indestructible truth.

What emerges from this era in Saitama is an aesthetic of stoic devotion—a vision of art not as luxury but as moral testimony.

Armor, swords, and the fusion of form and function

If there is one object that crystallizes the artistic worldview of medieval Saitama, it is the katana—not merely a weapon, but a confluence of metallurgy, calligraphy, and spiritual practice. Though the great swordmaking centers were located elsewhere (notably in Bizen and Yamato), Saitama’s proximity to Edo and its strategic river routes made it a hub for the use and commissioning of fine arms.

Excavations at Iwatsuki Castle, an important Muromachi-era stronghold, have revealed fragments of decorated sword guards (tsuba) and helmet ornaments (maedate) bearing clan crests and Buddhist motifs. These objects, though functional, reflect remarkable craftsmanship. The tsuba, often made of iron or copper alloy, were engraved with:

- Dragonflies, symbols of agility and perseverance

- Lotus flowers, reminders of the warrior’s spiritual duty

- The full moon, associated with enlightenment and vigilance

These motifs weren’t chosen arbitrarily. They reflected the mindset of a warrior class increasingly shaped by Zen Buddhism, which emphasized direct action, inner stillness, and mastery of self. The swordsmith’s work, then, became a kind of meditative precision—a task that demanded not only technical skill but spiritual clarity.

One surviving Saitama-made tsuba, now held at the Saitama Prefectural Museum, bears a stylized image of Fudō Myōō’s face surrounded by swirling flames. The engraving is deep, almost crude, but its intensity speaks to its function: not beauty for its own sake, but beauty in the service of resolve.

This principle extended to armor, particularly the lacquered cuirasses and iron helmets worn by Saitama’s military retainers. The kozane (small iron plates laced together with silk cord) were often dyed in clan colors, while the helmets bore family mon, or crests, in stylized form. One particularly arresting piece recovered from a temple storehouse in Hanno includes a crescent moon crest in beaten iron, framed by antler-like horns—a fusion of celestial and terrestrial imagery that reflected the wearer’s aspirations toward both martial and spiritual ascent.

These pieces were not mass-produced nor purely ornamental. They were portraits in steel, made to accompany a man to death, battle, or prayer.

The rise of ink painting and Zen visual culture in provincial strongholds

By the mid-14th century, the influence of Zen aesthetics—brought to Japan from China via monastic channels—had begun to permeate not only architecture and philosophy but also painting. The suiboku-ga (ink wash) style, with its sparse lines and empty spaces, found particular resonance among the warrior elite. In Saitama, Zen temples became quiet laboratories for this visual language.

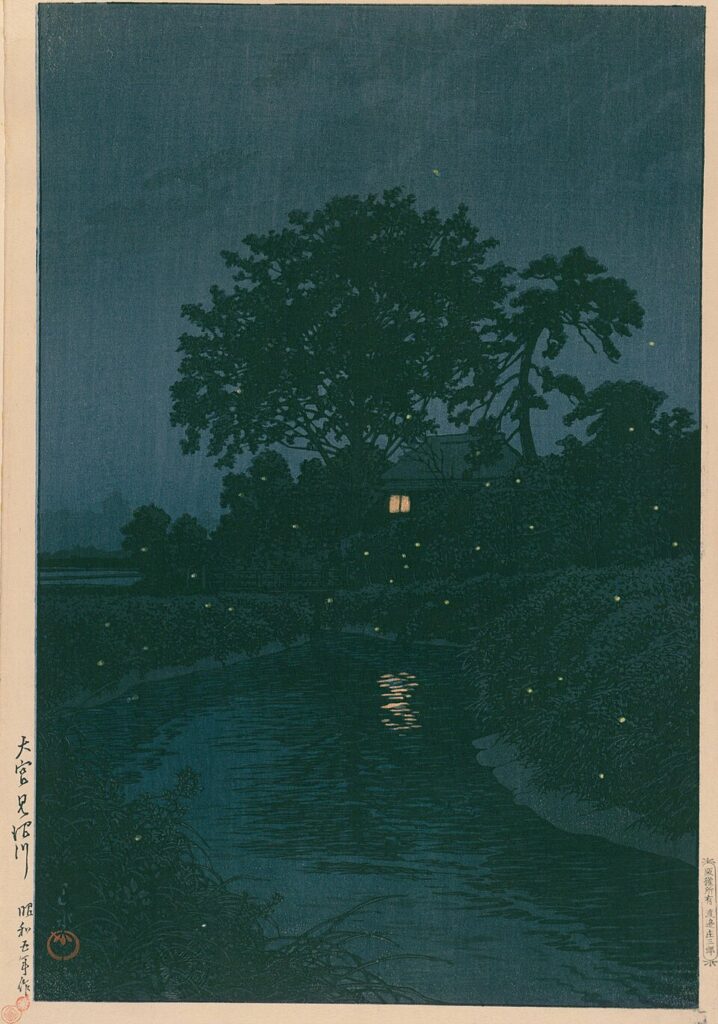

While few signed works survive, temple records and preserved scrolls from the Chichibu and Sayama regions indicate a tradition of local Zen-inspired painting, often depicting landscapes, sages, or natural scenes in monochrome ink. These were not intended for public display but for private contemplation—hung in tokonoma alcoves or kept in scroll boxes for use during retreats.

One scroll from Shōgan-ji Temple shows a lone pine tree rendered with five sweeping brushstrokes, standing beside a mountain path where a monk disappears into mist. The inscription reads simply: “The path does not ask where it leads.” The work’s power lies in its restraint—a hallmark of Zen influence, but also a reflection of Saitama’s provincial disposition. Here, art was meant to quiet the mind, not dazzle the eye.

These practices laid the groundwork for later tea ceremony aesthetics, including wabi-sabi, the celebration of imperfection and impermanence. In many ways, Saitama’s warrior-period art stands at the intersection of two disciplines: the martial and the contemplative. Armor and ink, blade and brush—each forged under pressure, each revealing the soul of its maker.

The Kamakura and Muromachi periods in Saitama mark a cultural transformation: from rustic Buddhist piety to refined warrior patronage, from devotional sculpture to disciplined painting. Through it all, the region’s art maintained a grounded, often understated power—less concerned with spectacle than with virtue, restraint, and endurance.

Edo-Era Refinement: Ukiyo-e, Fan Painting, and the Highway Culture

The Edo period (1603–1868) brought with it more than peace and political consolidation—it created a cultural landscape shaped by movement, leisure, and refinement. While the shogunate ruled from nearby Edo (modern-day Tokyo), Saitama became a key corridor in Japan’s developing network of roads and post towns. The result was a region increasingly touched by the rhythms of travel, the taste of merchants, and the quiet hand of artisans who adapted courtly traditions for a broader, more mobile audience. In this environment, the visual arts of Saitama flourished—not in the form of grand temples or war banners, but in paper, pigment, and portable beauty.

Nikkō Kaidō and the artistic culture of the Tōkaidō travelers

Though not on the famed Tōkaidō itself, Saitama was crisscrossed by major Edo-period highways such as the Nikkō Kaidō, Ōshū Kaidō, and Nakasendō, all of which linked the capital with the provinces. These roads brought an influx of pilgrims, merchants, and bureaucrats, each requiring lodging, food, and often entertainment. Along these routes, shukuba (post towns) like Kawagoe, Kumagaya, and Iwatsuki grew into thriving waystations—and with them grew a visual culture tailored to transience.

Art along the road was light, accessible, and often humorous. Travelers purchased painted fans, woodblock-printed guidebooks, and illustrated maps that turned geography into ornament. These weren’t merely souvenirs; they were part of a shared cultural literacy. Owning a fan painted with Mount Nikkō or a folding screen with scenes from Chichibu’s pilgrimage route marked one as both devout and fashionable.

Saitama’s artists, particularly in Kawagoe, became adept at catering to this demand. Though overshadowed by the ukiyo-e giants of Edo, a number of regional painters and printmakers developed distinctive styles that emphasized local scenery, seasonal beauty, and popular festivals. Among them was Kaneko Tōrin, a little-known but prolific painter active in the early 1800s, whose works combined classical motifs with scenes from Saitama’s riverbanks and mountains. One surviving handscroll in a Kawagoe collection shows a procession of townspeople attending a lantern festival, rendered with delicate brushwork and subtle color washes, the mood celebratory yet grounded.

The blending of travel, commerce, and art reached its height in the illustrated guidebooks that flowed from Saitama’s printing houses. These books, often adorned with miniature landscapes or local legends, functioned like today’s travel blogs—offering not only directions but images of what to admire, how to behave, and where to find beauty.

In this way, art became an extension of pilgrimage and pleasure, a visual memory that could be folded into a kimono sleeve or hung in a shop.

Itinerant printmakers and Saitama’s roadside stations

Though major ukiyo-e workshops were based in Edo, itinerant printmakers regularly passed through Saitama’s towns, selling prints, taking commissions, and sometimes setting up temporary studios. These artisans, known as machi-eshi (town painters), operated on the margins of the official art world but left behind a valuable record of regional taste and experimentation.

The woodblock prints they produced often combined classical themes—like views of Mount Fuji or seasonal flowers—with specific Saitama landmarks. One such example, discovered in a private archive in Fukaya, depicts the Arakawa River in winter, a fisherman hauling nets in the foreground while smoke rises from a distant bathhouse. The style is less polished than Edo prints, but it possesses a vivid immediacy—a sense of having been made quickly, for a known audience, in a known place.

Some of these machi-eshi adapted surimono techniques—privately commissioned prints that paired poetry with imagery. Wealthy merchants and educated travelers might request a personalized print to commemorate a trip to Chichibu’s 34 Kannon Temples, or to mark the first cherry blossoms in Gyōda. These prints, smaller in scale, often employed luxurious materials: mica for shimmering skies, embossed paper, and silver ink.

Though not revolutionary in design, these works are invaluable for understanding the provincial diffusion of ukiyo-e aesthetics. They show how the vocabulary of Edo’s floating world was translated into Saitama’s local idiom: less courtesan, more countryside; less Kabuki actor, more pilgrim on the road.

Three subjects were especially common:

- Landscapes of pilgrimage routes, often with poetic captions

- Local legends illustrated with didactic or humorous flair

- Seasonal festivals, capturing the calendar of provincial life

These motifs created a portable, popular art—one that blurred the line between image and artifact, map and memory.

The aesthetics of ephemerality in fans, prints, and poetry

Among the most elegant forms of Edo-period art in Saitama were painted folding fans (sensu), prized not only for their utility but for their subtle beauty. Many of these were produced by Kawagoe and Urawa workshops, where artisans collaborated with poets and calligraphers to create fans that blended image, verse, and gesture. A single fan might bear a moonlit scene of Chichibu’s hills on one side and a haiku on the other, written in flowing kana script.

These fans, like the woodblock prints and guidebooks, celebrated impermanence—the fleeting pleasures of travel, seasons, and social ritual. They were made to be used, not preserved: opened during a summer evening stroll, waved during a dance, then tucked away until the next festival. That very fragility gave them meaning. In the Japanese aesthetic tradition, to perish is not to fail, but to fulfill one’s purpose.

One particular form, the uchiwa-e (rigid fan print), became a minor specialty in Saitama. These were printed designs intended to be pasted onto round, rigid fans. Often seasonal or humorous in nature, they depicted everything from fireworks over the river to drunken monks or local actors. Few survive in good condition, but their designs have been cataloged by the Saitama Historical Society, revealing a world of lighthearted, vernacular imagery often absent from official histories.

This visual culture was intimately tied to poetry and performance. During Saitama’s many obon festivals, lantern parades, and shrine celebrations, fans and prints served as props—objects to be seen in motion, not framed. Even now, reenactments of these events in towns like Hanno or Kasukabe include workshops where children create traditional fans or stamp paper prints using blocks based on Edo-era designs.

What emerges from this period is a distinctive vision of art as portable, seasonal, and shared. In the shadow of the capital, Saitama developed a visual culture that resisted grandeur in favor of rhythm: the cycle of nature, the steps of a journey, the beat of a festival drum.

The Edo era in Saitama was not one of artistic revolution, but of elegant continuity—a time when pictures moved with people, beauty was meant to be held in the hand, and the world could be remade in ink, paper, and breath.

Hidden Halls: Saitama’s Artisans and the Power of the Local Guild

Behind the surface elegance of Edo-period fan paintings and road prints stood another, often overlooked engine of artistic life in Saitama: its artisan guilds. These were not the courtiers, painters, or monks who filled scrolls and palaces, but the skilled laborers whose hands shaped the everyday objects of beauty and function—lacquered boxes, ceremonial combs, finely wrought metal tools, dyed textiles, and carved festival floats. In towns like Kawagoe, Iwatsuki, and Hanno, these artisans worked not in solitude but within tightly organized guild systems that preserved technique, ensured economic stability, and transmitted aesthetic knowledge across generations. If the floating world brought art to the street, the guilds kept it anchored to the ground.

Lacquerware, metalwork, and craft lineages

Among the most respected of these crafts in Saitama was lacquerware—a tradition that combined Chinese techniques with native innovation. Saitama’s artisans, especially in Kawagoe, developed a style characterized by black or vermilion lacquer, sometimes inlaid with gold powder (maki-e) or mother-of-pearl. The work was not flashy, but refined: storage boxes, writing desks, combs, and portable shrines for household use.

These pieces served a dual role: they were functional objects and status symbols, exchanged as gifts between merchants or used to decorate the homes of upwardly mobile townsmen. The makers of such items belonged to hereditary guilds that operated with precision and discipline, often under the patronage of regional daimyō. These guilds controlled access to raw materials, guarded recipe secrets for lacquer blends, and ensured stylistic consistency through rigorous apprenticeship.

Saitama’s lacquerwork, while less famous than that of Kyoto or Kanazawa, had a distinctive personality: less ornate, more architectural. Decorative restraint became a form of virtue. A surviving calligraphy box from late Edo-period Kawagoe, for example, features no surface painting—only the grain of the wood beneath the lacquer, polished to a deep mirror finish. The effect is austere, almost Zen-like, evoking silence more than splendor.

In parallel, metalworking guilds flourished in towns like Hanno and Fukaya, producing iron tools, sword fittings, and religious ornaments. These included temple bell caps, lantern finials, and roof tiles, many of which still adorn local shrines. These were not mere technicians. The best among them were artists of the forge, shaping spiritual and civic life with hammer and fire.

Notably, several Saitama guilds maintained direct ties to larger urban craft networks, including those in Edo. This meant that provincial styles remained dynamic, not insular. Traveling craftsmen brought with them news of trends, while Saitama’s artisans sent their goods to markets far beyond the prefecture’s borders.

Folk art traditions passed through generations

Beyond the formal guilds lay another layer of artistry: the folk crafts made by farmers, villagers, and seasonal workers during the agricultural off-season. These included toys, dolls, talismans, festival banners, and embroidered garments. What these lacked in polish they made up for in expressive charm and symbolic depth.

Saitama’s Chichibu region, in particular, became a cradle for vibrant folk textile traditions. Women in mountain villages practiced sashiko, a decorative mending technique that used white cotton thread on indigo cloth to create repeating geometric patterns. Originally born of necessity—to reinforce worn-out garments—sashiko evolved into an aesthetic practice in its own right. Quilts, jackets, and firemen’s coats from Chichibu display complex designs that blur the line between utility and art.

Another folk tradition unique to Saitama was the making of hand-carved masks for the annual Shishi-mai (lion dance). These masks, sometimes grotesque and sometimes comic, were carved from local wood and painted with natural pigments. Each bore the marks of individual temperament—thick eyebrows, bulging eyes, exaggerated smiles—creating a kind of regional iconography for the spirits and emotions of rural life.

These folk arts were rarely signed. They emerged from a communal ethos, where authorship was less important than continuity and participation. And yet they shaped the aesthetic environment of Saitama just as profoundly as lacquerwork or temple sculpture. Even today, the influence of these objects can be seen in contemporary design studios that revisit folk forms in modern materials.

Three characteristics marked these regional crafts:

- Functionality enhanced by beauty, not sacrificed to it

- Local materials and symbols, rooted in geography and myth

- Generational continuity, where innovation came through repetition, not rebellion

It is here—in the balance of hand, eye, and tradition—that Saitama’s true artistic backbone lies.

The artistic role of merchant culture in castle towns

The city of Kawagoe, sometimes called “Little Edo,” serves as a case study in how merchant culture supported and shaped artistic life. Unlike the samurai who commissioned grand works for status or salvation, the merchant class in towns like Kawagoe fostered a more pragmatic and elegant style, combining art with business, taste with thrift.

Kawagoe’s merchants, many of whom grew wealthy supplying rice, textiles, or timber to Edo, used their resources to commission storefront signboards, festival floats, and shop interiors that doubled as artistic statements. These often incorporated carved woodwork, decorative tiles, and fine paper hangings. The Kurazukuri warehouse buildings—some still standing—featured ornate clay roof tiles with stamped family crests, wooden lattice windows, and elegantly proportioned facades.

These were not displays of idle wealth. They were public markers of credibility and refinement, a visual language that said, “This house is stable. This family endures.” In this context, the arts functioned as both ornament and proof.

Merchant families also patronized local painters and calligraphers, inviting them to decorate tea rooms, produce genealogical scrolls, or create New Year’s greetings on behalf of the household. In return, these artists received lodging, meals, and introductions to clients—further entrenching the arts within Saitama’s civic fabric.

Perhaps most notably, these same merchants funded many of the region’s festivals, particularly in the 18th and 19th centuries, commissioning elaborate floats, lanterns, and costumes. The famous Kawagoe Festival, still held today, owes much of its visual splendor to the tastes and ambitions of these patrons.

The art of Saitama’s Edo-era towns was neither courtly nor rustic. It was a middle-class aesthetic, marked by careful restraint, community purpose, and quiet excellence. What mattered was not to astonish, but to endure.

By the end of the Edo period, Saitama had become a place where guild hall, farmhouse, and storefront each contributed to a broad artistic ecosystem—one based not on spectacle or ideology, but on skill, continuity, and local pride.

Meiji Modernity and the Collapse of the Old Order

The fall of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1868 and the rise of the Meiji state marked one of the most dramatic ruptures in Japanese history. Castles fell quiet, guilds dissolved, and the old world of samurai, merchants, and monks gave way to conscription, railways, and parliamentary reform. For artists and craftsmen in Saitama, the shift was not only political but existential. The Meiji government, eager to modernize Japan on Western terms, redefined the very meaning of art. In doing so, it severed Saitama’s centuries-old aesthetic traditions from their social foundations and forced its creators to navigate a new and often bewildering cultural terrain. Some adapted, others vanished. A few transformed adversity into innovation.

Westernization, railroads, and new urban aesthetics

The Meiji regime’s obsession with progress manifested most immediately in infrastructure. Railroads were laid across the Kanto plain, including major lines through Omiya, Kawagoe, and Urawa, bringing telegraph poles, factory chimneys, and new patterns of life. Towns that had once been sleepy post stations found themselves transformed into industrial centers, commuter hubs, or military supply depots.

With this shift came a new built environment—and new visual priorities. In place of tiled roofs and painted lanterns came brick façades, gaslights, and imported ironwork. Government buildings, post offices, and banks in Saitama adopted Western architectural styles: Italianate cornices, arched windows, and columned entrances. The Kawagoe Branch of the Bank of Japan, constructed in the early 20th century, resembles a European consulate more than a samurai warehouse.

These aesthetic imports reflected not only taste but ideology. Meiji modernizers believed Japan must look Western to be treated as modern, and visual culture was conscripted into this campaign. Traditional arts were either rebranded as “national treasures” for export or discarded as primitive. In this context, Saitama’s craft traditions struggled. Lacquerware guilds saw their markets evaporate. Metalworkers now forged parts for train cars and military hardware, not lanterns or sword fittings.

However, the railway also created new circuits of cultural exchange. Artists in Saitama could now travel to Tokyo in hours, study European painting techniques, or exhibit work alongside those from Nagoya, Osaka, or even Paris. The painter Kobayashi Kokei, born in Takasaki but active in Saitama in the early 20th century, personifies this moment. Trained in both Nihonga (traditional Japanese painting) and Yōga (Western-style oil painting), he painted landscapes and figures that combined subtle Japanese linework with Western volumetric shading. His success showed that Saitama artists could adapt—but not without tension.

The fall of guilds and the rise of Saitama’s painters’ associations

Perhaps the most consequential artistic shift of the Meiji period was the collapse of hereditary craft guilds. The new civil code abolished their legal privileges, and younger generations—now required to attend state-run schools—were often steered away from artisan trades altogether. The result was a sudden break in the apprenticeship chains that had preserved regional styles for centuries.

In their place arose art societies, painters’ salons, and study groups—new institutions modeled on Western academies. Saitama’s first notable artists’ collective was founded in Urawa in the late 1890s, focusing on calligraphy and ink painting. Within a decade, groups had formed in Kawagoe and Omiya, offering exhibitions, critiques, and access to government-sponsored competitions. These organizations provided a lifeline for traditional aesthetics, even as their language shifted to meet modern expectations.

One of the earliest and most influential was the Musashi Art Association, which held its first public exhibition in 1912. Though now mostly forgotten, it brought together a cohort of painters, woodblock printers, and amateur sculptors committed to preserving Saitama’s local landscapes and festivals in visual form. Many were schoolteachers, postal clerks, or former guild apprentices who sought to record what they feared would vanish. Their work—small in scale, earnest in tone—captures the uneasy beauty of a world slipping away.

Among their preferred subjects:

- Rural shrines engulfed by factories

- Old women weaving sashiko under electric lights

- Festival floats parked beside telegraph wires

These images offer more than nostalgia. They document the collision of temporalities, where centuries of visual habit meet the blunt edge of progress.

Yōga vs. Nihonga: Debates in an evolving identity

Perhaps nowhere was the Meiji struggle for cultural identity more pronounced than in the debate between Yōga and Nihonga—Western-style vs. Japanese-style painting. This was not a stylistic disagreement but a philosophical one: Should Japanese artists imitate the West, or reassert their own tradition in modern form?

In Tokyo, this debate played out in major exhibitions and elite academies. But in Saitama, it surfaced in quieter forms: community debates, school curricula, and the choices made by individual painters. One such artist was Shibata Zeshin, known for his mastery of both traditional lacquer techniques and Western-style perspective. Though based primarily in Tokyo, Zeshin’s followers opened studios in Kawagoe and Urawa, blending Meiji realism with Edo-era subjects.

Local art schools began offering classes in both traditions. In one 1908 curriculum from a Kawagoe girls’ school, students were expected to study Japanese ink painting on Mondays and watercolor still lifes on Thursdays—a schizophrenic compromise emblematic of the era.

This dual training produced a distinctive hybrid style in Saitama: rural genre scenes rendered in European perspective, or temple icons shaded with chiaroscuro. Some critics saw this as dilution. Others saw it as synthesis. Either way, it marked a profound transformation in the region’s visual language.

By 1910, prefectural exhibitions had become regular affairs, often held in train stations or public halls. These shows brought together traditional crafts, school art, and new media in uneasy juxtaposition. One observer, writing in the Saitama Shinbun in 1911, lamented: “What once belonged to the soul now belongs to the wall.”

That remark, mournful and sharp, captures the central drama of Meiji-era Saitama: the redefinition of art from embedded communal practice to individual visual product. Where once art adorned tools, homes, and festivals, it now hung alone, labeled, judged.

Still, the period was not without achievement. It produced new kinds of artists, new institutions, and new ways of seeing. But it did so at a price: the fragmentation of a world in which form, faith, and function had once been whole.

War and Occupation: The Silence of the Canvas

Art does not thrive under bayonets, but it does not entirely vanish either. The decades between the late 1930s and the early 1950s saw Saitama’s artistic life enter a long, muffled twilight—pressed into service by the state, stifled by scarcity, and quietly reconstituted beneath layers of censorship and rubble. The imperial war effort transformed Japan’s cultural apparatus into a machine for national unity, moral indoctrination, and visual propaganda. Painters became illustrators of “spirit,” craftsmen were conscripted into manufacturing, and art schools were repurposed as technical academies for military industry. Yet even within these constraints, Saitama’s artists found subtle ways to express endurance, grief, and, in a few cases, resistance.

The militarization of art and school aesthetics

By the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, the Japanese state had fully subordinated the arts to its ideological apparatus. Artists in Saitama were not spared. Government mandates required all prefectural exhibitions and school contests to feature themes aligned with patriotism, sacrifice, or imperial glory. Even traditional arts were reinterpreted to fit militarist values: lacquered armor became a symbol of eternal duty, ink paintings of Mount Fuji were reframed as signs of national destiny, and calligraphy competitions began to favor phrases like “Kokutai no hongi” (the national essence).

At the local level, this meant that students across Saitama—whether in Urawa, Kumagaya, or Kawagoe—were trained to draw soldiers, planes, and battleships. The art classroom became a preparatory space for future sacrifice. The Ministry of Education distributed textbooks featuring sample illustrations of kamikaze pilots, naval drills, and rural families waving flags. One such volume, published in 1942 and still held in the Saitama Prefectural Archives, includes step-by-step instructions for drawing a Zero fighter plane.

In parallel, many adult artists were mobilized into the Nihon Bijutsukai, the state-approved art society, which organized exhibitions that glorified war. Participation was often compulsory for continued access to materials and commissions. Some Saitama artists complied, painting scenes of soldiers on the Manchurian front or rice fields blooming under wartime slogans. Others turned inward, producing still lifes, landscapes, and anonymous portraits that quietly sidestepped the imposed narrative.

But the line between collaboration and survival was thin. The painter Hayashi Keiji, born in Saitama in 1908, won national acclaim for his ink illustrations of army life—spare, elegant, almost tender in tone. After the war, he was ostracized for having lent his talent to the state. Yet to judge his work solely by subject matter is to ignore its ambiguity: many of his soldier portraits depict not triumph but fatigue, not rage but resolve without joy.

It is in this ambiguity that the aesthetic reality of wartime Saitama begins to emerge—a world where visual art walked a knife’s edge between duty and despair.

Blackouts, paper shortages, and censored imagery

As the war dragged on and Allied bombing intensified, material scarcity began to strangle the visual arts at their most basic level. Paint, paper, ink, and canvas were rationed or unavailable. Art supply shops in Omiya and Kawagoe shuttered their doors or converted to military use. The Saitama Prefectural Art School suspended its courses in 1944, citing both safety and lack of materials.

Artists responded with ingenuity. Ink was stretched with water; old scrolls were repurposed for new work. Some turned to charcoal drawing, using kitchen coals on salvaged cardboard. These works, rarely preserved, carry a haunting immediacy. A surviving piece from 1945, signed only “S,” depicts a mother and child crouched beneath a darkened sky, the shading uneven, the figures blurred as if by smoke.

Censorship further narrowed the field. All public exhibitions were screened by censors for “unpatriotic content.” Artists known for ambiguous or subversive work were monitored. Some ceased to exhibit altogether, choosing instead to paint for private eyes—or none. These “closet paintings,” as they came to be known, formed a quiet canon of wartime interiority: portraits of aging parents, empty temples, dead trees. They were rarely signed, often dated only vaguely, and almost never sold.

Meanwhile, bombing raids over the Kanto region—including the devastating March 1945 Tokyo air raids—spilled into parts of southern Saitama. Blackouts became routine. In such conditions, the idea of visual pleasure, let alone artistic growth, seemed obscene. But in the stillness, some painters returned to essentials: the play of shadow, the memory of form, the persistence of light.

In a 1946 oral history, one painter from Chichibu recalled, “We painted not what we saw, but what we could not say.” That silence—imposed, endured, and finally expressive—became the dominant tone of wartime art in Saitama.

Urawa’s dormancy and the artists who went underground

Urawa, long a center of Saitama’s cultural and administrative life, was particularly hard hit by wartime austerity. Its previously lively salons and painters’ collectives either dissolved or fell dormant. The Musashi Art Association, once the pride of the region, held no exhibitions after 1942. Their gallery was converted into a rationing office; their archives, partially destroyed by fire.

And yet a few artists continued to meet in secret—in homes, tea rooms, even abandoned kura storehouses—to share sketches, read foreign art journals smuggled in from the black market, and discuss what might come after the war. One such gathering, known informally as the “Midnight Group,” included young painters, calligraphers, and teachers who resisted both militarism and nihilism. Their motto, recorded in a surviving notebook, was: “Not protest, not escape, but preparation.”

These quiet meetings laid the foundation for the Urawa Art Movement of the 1950s, but at the time, they were simply acts of cultural survival. Members worked in schools by day, wrote letters to each other by candlelight, and preserved books and prints from destruction. In doing so, they became unlikely curators of a broken visual tradition.

In the final months of the war and during the U.S. occupation that followed, Urawa became a place of rebuilding—slow, careful, and often lonely. The American authorities encouraged exhibitions and public art as tools of democratization, but the emotional damage lingered. Many artists had lost studios, families, or entire bodies of work. Some never painted again.

Yet in that silence, something began to grow. Sketchbooks reappeared. Brushes were cleaned. The war had left a crater in the heart of Saitama’s artistic life, but the edges of that crater began to bloom—not in defiance, but in quiet continuity.

Postwar Rupture: Urawa Art Movement and Avant-Garde Rebirth

What emerged from the ashes of war in Saitama was not simply a revival of old forms but a profound rupture—a radical rethinking of what art was, whom it served, and how it ought to speak. In the early 1950s, a constellation of painters, printmakers, and thinkers gathered in Urawa and nearby towns to form what became known as the Urawa Art Movement. This was not a school in the academic sense, nor a coordinated group with manifestos or dogmas. It was a regional avant-garde, shaped by trauma, exile, and a desire to forge meaning in a society that had not yet found its footing.

The movement was quiet but electric. In a nation occupied, censored, and wrestling with its identity, Urawa’s artists turned to abstraction, introspection, and radical formal experimentation. Their work was not an imitation of Tokyo’s modernists, nor a provincial echo of Western trends—it was its own answer to catastrophe, forged in humble studios and community halls, often with borrowed materials and uncertain audiences.

The 1950s Urawa artists and the rise of abstract painting

The earliest stirrings of the movement came in 1948, when a handful of painters—many former members of the prewar Musashi Art Association—began holding informal exhibitions under the title Urawa Bijutsu Dōmei (Urawa Art League). Their early shows, held in makeshift venues such as school auditoriums or bookstore basements, included not only paintings but also calligraphy, sculpture, and handmade posters. They were intentionally democratic—unjuried, inclusive, and open to criticism.

Among the leading voices was Hasegawa Saburō, a painter who had trained in traditional Nihonga techniques but abandoned figuration entirely after the war. His 1952 work Composition in Ash and Vermilion—a stark, layered abstraction made with soot, pigment, and sand—became an early icon of the movement. Hasegawa’s approach was not decorative. He once wrote, “Beauty is not the goal. Only the trace of thought made visible.”

Others followed suit. Tsuchiya Shigeo, another central figure, brought elements of Surrealism and existentialism into the fold, inspired by fragments of French and German literature circulating through black-market bookstores. His canvases from the mid-1950s depict fractured landscapes and isolated forms—dreamlike but never whimsical.

What unified these artists was their rejection of narrative and sentimentality. Unlike the sentimental realism that dominated state-sponsored art in the 1930s and 40s, Urawa painters favored ambiguity, fragmentation, and tension. Their work embodied the unspoken: the burned house, the missing father, the moral vacuum. In doing so, they gave visual form to Japan’s unarticulated postwar psyche.

And yet, their art was not morose. It carried within it the energy of reclamation. In a nation flooded with American pop culture, Soviet propaganda, and Tokyo’s rapid commercialization, these Saitama artists carved out a space for quiet, dignified inquiry. They asked not what art could sell, but what it could withstand.

Gashōjin and the challenge to official art salons

By the mid-1950s, the Urawa movement had attracted a small but passionate group of younger artists who, frustrated by the conservatism of official art salons, formed their own exhibition society under the name Gashōjin (画匠人)—a deliberately archaic term meaning “craftsman-painters.” This was a conscious rebuke of both bureaucratic art and Tokyo’s increasingly fashionable “Art Informel” scene.

The Gashōjin group operated as a roving exhibition circle, organizing traveling shows in libraries, schools, and train stations across Saitama Prefecture. Their catalogs, crudely printed and sparsely written, emphasized the process of making over theoretical posturing. The works themselves spanned mediums: layered collage, mixed-media assemblages, printmaking, and even early experiments in installation.

In a 1956 group exhibition in Kawagoe, one participant displayed a canvas pierced with nails and stitched with thread, titled simply Mother’s Apron. Another submitted a floor-bound sculpture made of melted roofing tiles and charred wood from his family’s wartime home. These works were raw, not only in material but in purpose: memorials disguised as modernism.

The Tokyo critics ignored them. But among Saitama’s students, schoolteachers, and amateur artists, the Gashōjin exhibitions sparked excitement. Art was no longer an elite performance, but a public reckoning. It was honest, handmade, and deeply local.

Three principles quietly emerged from their practice:

- Refusal of institutional approval as a prerequisite for artistic legitimacy

- Elevation of memory and material over polish or ideology

- Commitment to art as a form of personal and regional autonomy

This last point matters most. At a time when Tokyo’s art scene was increasingly pulled toward commercial galleries and international biennials, Urawa’s artists insisted on working from where they stood, even if it meant obscurity.

How one Saitama gallery changed the landscape

The tide began to shift in 1958 with the founding of the Urawa Gallery of Contemporary Art, a modest exhibition space launched by a local bookseller, Abe Masaki, who had long supported regional artists. Located above his family’s stationary shop, the gallery had white walls, poor lighting, and a cement floor—but it quickly became a nerve center for avant-garde activity in Saitama.

Abe’s vision was simple: give artists space, demand nothing in return, and trust the work to speak. He refused to charge exhibition fees, allowed controversial work, and welcomed unknowns. Over the next decade, the gallery hosted over 200 exhibitions, including the early shows of several figures who would later gain national recognition.

One such artist was Kumagai Kazuya, whose early woodblock prints of collapsing staircases and industrial ruins drew comparisons to German Expressionism. Another was Yamamoto Rieko, whose calligraphic abstractions—drawn with broom-sized brushes—merged Zen aesthetics with postwar fury. Both credited the Urawa Gallery as the only place in postwar Japan where they felt free to “fail publicly.”

The gallery’s success inspired a wave of similar ventures throughout Saitama: artist-run spaces in Kasukabe, Tokorozawa, and Chichibu, often located in former kura warehouses, schoolrooms, or shrines. These spaces were not commercial. They functioned as gathering points, laboratories, and sanctuaries. Some lasted only a year. Others still exist in altered form.

What emerged by the mid-1960s was a networked regional avant-garde, bound not by doctrine but by mutual respect, shared history, and an ethos of sincerity. Urawa had become more than a city; it was a state of mind—an artistic stance rooted in humility, experimentation, and emotional truth.

In the history of modern Japanese art, Saitama’s contribution is often overlooked. But the Urawa Art Movement offers something that Tokyo, for all its glamour, could not: a slow, principled rebirth, forged in the shadow of ruin, in the language of clay, soot, and silence.

Public Art and the Urban Landscape: Sculpture Parks and Train Stations

By the 1970s, Saitama had completed its transformation from a postwar refuge to a fully integrated extension of metropolitan Tokyo. Highways carved through rice fields, commuter trains stitched distant suburbs to the city center, and housing developments sprawled across what had once been farmland and pilgrimage routes. Yet amid the concrete and transit, a new kind of art quietly took root: public sculpture, municipal murals, and architecturally embedded artworks designed not for galleries, but for streets, parks, and train stations. These works, though often overlooked in national art histories, marked a critical shift in the region’s cultural philosophy—art not as display, but as infrastructure.

In Saitama’s cities and towns, civic identity began to be expressed through form and texture: a bronze figure on a plaza, a relief mural on a station wall, a stone installation beside a schoolyard. These weren’t mere decorations. They were deliberate interventions, shaping the rhythm of public life and embedding artistic presence into the everyday.

Sculptural interventions in Saitama’s new towns

During Japan’s economic boom of the 1960s and 70s, the national government began building planned communities to accommodate the growing urban population. In Saitama, these included developments like Shintoshin, Midori Ward, and Sakado City, all of which followed a now-familiar pattern: clustered high-rise housing, parks, civic centers, and transit nodes. But in contrast to the brutalist uniformity of other postwar developments, Saitama’s planners often included art commissions in their blueprints.

The result was a surprising proliferation of public sculpture, much of it abstract and executed in stone, concrete, or metal. These works were typically sited in open plazas, roundabouts, or school entrances—places of daily circulation rather than reflection. One striking example is Abe Shigeyuki’s 1981 installation in Omiya’s Civic Green: a cluster of interlocking granite forms, evoking both geological layering and traditional architectural brackets. Without a plaque or explanatory text, the sculpture quietly invites touch, play, or pause.

What distinguished Saitama’s approach to public sculpture was its refusal to monumentalize. Unlike the towering war memorials or nationalist bronzes found elsewhere, these pieces were modest in scale and tone. They didn’t instruct the viewer—they coexisted. Their value lay not in their iconography but in their presence.

In the 1980s, this philosophy crystallized in the “Saitama Sculpture Exhibition,” an open-air biennial launched by a coalition of local artists, city planners, and educators. The exhibition rotated through different towns—Urawa, Kawagoe, Chichibu—and prioritized site-specific works. Sculptors were encouraged to work with local materials, respond to geographic features, and consider use patterns of pedestrians. The result was not a temporary spectacle, but a distributed museum, free and permanent.

Some highlights from this period:

- A corten steel spiral embedded in the lawn of a Kasukabe library, designed to change color with the seasons

- A calligraphy-inspired concrete ribbon at a Saitama University walkway, referencing both brushwork and expressway curves

- A sound sculpture installed beneath an overpass, where dripping water activated chimes during rainstorms

These works reflect a unique ethos: art as quiet punctuation in the urban sentence. They don’t demand interpretation. They reward return.

Tokorozawa and the intersection of transit and muralism

One of the most ambitious public art programs in postwar Saitama unfolded not in the capital, but in Tokorozawa, a city once known for its airbase and now a major commuter hub. In the late 1970s, as the Seibu Railway expanded, city officials partnered with a group of painters and ceramicists to transform station interiors into sites of narrative art.

The centerpiece was the “Railway Chronicle Mural” at Tokorozawa Station, completed in 1983 by artist Murata Hiroko. Spanning over 30 meters of platform wall, the mural traces the city’s history from medieval farming village to aerospace site to suburban center. Rendered in stylized relief and glazed ceramic, the work combines traditional visual motifs—plowing oxen, shrine gates—with modern forms like airplanes, gears, and commuter trains.

But this was no nostalgic pastiche. The mural’s central conceit is motion itself: everything curves, flows, and migrates. Viewers move along the mural just as trains glide through the station. Art and transit are made inseparable.

Similar projects followed. The Kotesashi Station Mosaic, installed in 1987, combined aluminum sheeting with painted tile, depicting seasonal flora from Saitama’s hills. The artists collaborated with local schoolchildren, incorporating their drawings into the final design. This approach—collective authorship with civic intent—became a Tokorozawa hallmark.

What made these murals effective was not their technical execution, which was uneven, but their integration into the experience of place. They weren’t merely seen—they were encountered, passed by, relied upon as landmarks. In this way, they resurrected an older tradition: the narrative frieze, adapted to the logic of the commuter age.

Art as urban planning: civic pride through concrete and bronze

By the late 1980s and into the 1990s, Saitama’s municipalities increasingly embraced public art as a tool of civic branding. This trend coincided with a national push for “furusato” (hometown) identity campaigns, designed to counteract urban alienation and demographic decline. For cities like Chichibu, Fukaya, and even Saitama City itself, the answer was to embed visual art into urban renewal projects.

One striking example is the Chichibu Station Square redevelopment of 1995. As part of the redesign, planners commissioned a bronze sculpture series titled Echoes of the Mountains, depicting figures from regional folklore—forest spirits, travelers, and festival dancers. Rather than standing on plinths, these sculptures were placed at ground level, designed to be walked around, leaned against, or integrated into street furniture.

Likewise, in Urawa’s Kita Ward, a 1998 housing complex included not only sculptural courtyards but also ceramic wayfinding tiles embedded in the sidewalks, each designed by a different local artist. These works combined aesthetic utility with symbolic geography: flowers for parks, cranes for hospitals, bells for schools.

In these projects, art became inseparable from civic architecture. It marked boundaries, suggested routes, softened corners. It made cities legible—not through signs alone, but through shape, color, and memory.

Crucially, these efforts were locally commissioned, often involving open calls or public juries. They reflected not a national style but a municipal voice, rooted in the textures of daily life: the curve of a park bench, the shadow of a tower, the mosaic underfoot.

For a prefecture long dismissed as Tokyo’s backyard, this investment in public art was not just beautification—it was a quiet claim to identity, continuity, and autonomy.

Saitama’s sculpture parks, murals, and urban installations remind us that the frontier of artistic innovation is not always in studios or museums. Sometimes, it is where a child meets a shadow on a plaza, or a commuter glances at a tile and remembers a name. Art, here, is not spectacle. It is structure.

Manga, Animation, and Pop Art: From Saitama to the Screen

If the shrine and the train station defined the past and present of Saitama’s public art, the next frontier unfolded not in stone or canvas, but on paper, screen, and satellite broadcast. From the 1990s onward, Saitama emerged—somewhat unexpectedly—as a crucible for manga culture, animated television, and mass-media visual art, exporting its identity across Japan and, eventually, the world. This transformation was not driven by policy or planning. It was a grassroots cultural explosion, shaped by local studios, quirky characters, and an audience hungry for stories grounded not in the mythical or historical, but in the banal, familiar, and absurd.

Manga and anime in Saitama did not glorify the region. Instead, they embraced its ordinariness—its suburbs, train lines, and shopping arcades—as narrative stage. In doing so, they created a new kind of regional art: one born not in temples or ateliers, but in convenience stores, apartment balconies, and fictional fourth-grade classrooms.

Crayon Shin-chan and the Kasukabe phenomenon

No figure looms larger in Saitama’s contemporary cultural output than Crayon Shin-chan, the mischievous, inappropriate, and hilariously blunt preschooler created by manga artist Usui Yoshito. First serialized in 1990 and quickly adapted into a long-running animated series, Crayon Shin-chan is explicitly set in Kasukabe, a real-life city in eastern Saitama. The show makes no attempt to disguise the location—characters refer to local stations, streets, and landmarks by name. Viewers around Japan, and eventually across the globe, were introduced to Saitama through the antics of a five-year-old with terrible manners and surprisingly sharp observations.

What made Shin-chan revolutionary wasn’t its animation (which was crude), nor its writing (which was often gleefully vulgar), but its hyperlocal realism. The show’s creators insisted on grounding the comedy in the texture of everyday life in suburban Saitama. Shin-chan’s house is a typical two-story prefab. His father works a dreary corporate job in Tokyo. His mother shops at a local supermarket. The family’s dramas—debt, dinner, discipline—reflect a life lived within the gravitational pull of the metropolis, but outside its glamour.

Saitama quickly embraced the accidental fame. Kasukabe’s city tourism office began producing Shin-chan-themed guides and maps. Statues of the character appeared near the station. In 2006, the Kasukabe Municipal Art Museum even hosted a retrospective on the visual evolution of the show, complete with Usui’s original drawings, character model sheets, and episode layouts.

The significance of Crayon Shin-chan goes beyond merchandising. It made the suburban middle-class aesthetic—so often dismissed or ignored—into a site of satire, empathy, and national recognition. Shin-chan’s crude crayon drawings, in the hands of Usui and his team, became symbols of an unpolished but enduring cultural reality: life in the shadow of Tokyo, defined by routine, interruption, and humor.

Saitama’s unexpected role in the manga boom

Beyond Shin-chan, Saitama has quietly become home to a number of influential manga artists and studios, drawn by its proximity to Tokyo, affordable rents, and residential quiet. Unlike the tightly packed quarters of Shinjuku or Nakano, the cities of Koshigaya, Warabi, and Tokorozawa offer young artists the space to work and the mental breathing room to create.

In the early 2000s, the prefecture gained new prominence with the serialization of One-Punch Man, a manga created by the artist known as ONE, and later illustrated by Yusuke Murata. Though the series is more fantastical than Shin-chan, it, too, is set in a vaguely Saitama-like world. Its protagonist, the bald and bored superhero Saitama, is named after the prefecture itself—a subtle joke on its reputation for being unremarkable, especially compared to its glamorous neighbor.

This tongue-in-cheek naming captured a new generation’s ironic relationship with regional identity. Far from hiding their suburban roots, artists began to flaunt them. Saitama became a stand-in for the everyman Japan—neither rural nor urban, traditional nor cutting-edge, but somewhere in between. A place of budget groceries, long train rides, and anonymous apartment towers.

The manga community responded. Fan conventions and dōjinshi markets began popping up in Saitama City and Kawagoe. The annual Saitama Comic Festival, launched in 2008, now attracts thousands of amateur and professional artists. Local libraries expanded their manga collections; even academic conferences began exploring manga as serious visual literature, with Saitama frequently cited as a case study in regional representation.

Meanwhile, smaller studios based in Omiya and Fukaya began producing animated shorts for television and web release, many of which used local landmarks or dialects. This localization—once avoided—became a mark of distinction, part of a growing national movement toward “local manga” (chiiki manga), where artists adopt their hometowns as narrative stage and subject.

Saitama, long seen as a cultural satellite, had now become a generator of stories that resonated nationally and internationally, not in spite of its ordinariness, but because of it.

When commercial art becomes cultural heritage

By the 2010s, it had become clear that manga and animation were not passing trends but pillars of Japan’s cultural diplomacy and identity. Saitama responded by institutionalizing what had once been considered low art. The Saitama Manga and Anime Museum, opened in 2015 in a former bank building in Kasukabe, now houses thousands of original storyboards, production cels, and interview recordings. Its mission is both preservational and educational—treating manga not merely as media but as a visual art with narrative depth and social function.

Visitors can view the pencil sketches behind iconic anime sequences, participate in drawing workshops led by local illustrators, and explore the evolution of manga printing techniques from the 1960s to the digital present. Special exhibits have included retrospectives on Shin-chan, One-Punch Man, and lesser-known series like “Chichibu Night Express,” a local romance manga set entirely on the Seibu Railway.

This institutional embrace mirrors a broader shift in Japan’s cultural policy. As the government pushes manga and anime as part of its “Cool Japan” initiative, local prefectures are rebranding themselves through pop-cultural identity. Yet in Saitama, the process feels less like marketing than memory work. The region isn’t inventing new icons—it’s claiming those already born from its streets, stations, and classrooms.

The boundary between commercial and cultural art has blurred. Statues of Shin-chan are not advertisements. They are folk monuments. Manga anthologies once sold for pocket change are now archival records of a region’s psychology, humor, and values.

Saitama’s journey from clay dōgu to digital anime is not linear, but it is coherent. At every turn, its artists have adapted to medium, audience, and circumstance without abandoning the local. Even when broadcast on national TV, even when translated into Portuguese or Korean, Saitama’s pop art remains stubbornly itself—irreverent, provincial, honest, and unafraid to laugh at its own reflection.

Contemporary Voices: Museums, Biennials, and the Art Schools of Today

By the 21st century, Saitama had completed a cultural arc few regions in Japan could match: from prehistoric ritual clay to pop-cultural satire, from medieval temples to suburban manga studios. Yet what defines the current era is neither a return to tradition nor a complete embrace of global trends. Instead, contemporary art in Saitama sits in productive tension—between local heritage and international dialogue, between institutional seriousness and playful experimentation. Its museums, art schools, and regional festivals form the backbone of a living, evolving artistic ecosystem—one that builds on the past without being beholden to it.

In studios, lecture halls, and gallery spaces across the prefecture, artists are reimagining Saitama not as periphery but as platform—a stage from which to speak both to the neighborhood and the world.

Saitama Museum of Modern Art and its unique curatorial vision

At the institutional level, the centerpiece of Saitama’s contemporary art infrastructure is the Saitama Museum of Modern Art (埼玉県立近代美術館), often abbreviated as MOMAS. Located in Kita-Urawa Park, the museum was designed by celebrated architect Kurokawa Kisho and opened in 1982. Its austere glass-and-concrete form houses one of the most thoughtful regional collections in Japan, bridging early 20th-century European modernism, Japanese avant-garde work, and contemporary regional voices.

From its inception, MOMAS has avoided the grand, nationalistic narratives that dominate larger institutions in Tokyo or Kyoto. Instead, it has focused on themes of memory, material, and place. Its exhibitions often pair local Saitama artists with international figures, placing, for example, a GUTAI movement painting beside an Urawa abstractionist, or a Bauhaus chair alongside furniture designs by students from a Saitama technical college.

This curatorial strategy underscores one of the museum’s unspoken missions: to collapse the divide between global modernism and regional craft. The museum’s permanent collection includes works by Paul Klee, Alexander Calder, and Le Corbusier, but also highlights Saitama-based artists like Kobayashi Kokei and Tsuchiya Shigeo. More than just a gallery, the museum serves as a civic forum, hosting lectures, hands-on workshops, and collaborations with local schools.

A particularly successful program has been its “Artist in Community” residency series, launched in 2008, which invites contemporary Japanese artists to embed themselves in specific neighborhoods of Saitama, from Kasukabe’s housing blocks to Chichibu’s mountainside villages. The resulting work is shown not just in the museum but in community centers, shopping arcades, and even train cars. This reflects the institution’s conviction that art is not something to be extracted from the region for display—it must grow within it.

The sculptural programs of Saitama University

While MOMAS anchors the prefecture’s public cultural sphere, Saitama University plays an equally vital role in cultivating the next generation of artists. Though known primarily as a research institution, its Faculty of Education includes a rigorous fine arts track, with a longstanding emphasis on sculpture, installation, and materials experimentation.

Since the 1990s, the sculpture department has fostered a unique pedagogical model: combining material technique with site-specific engagement. Students are expected not only to master stone carving, bronze casting, and mixed-media construction, but to develop public works responsive to space, audience, and historical context. The campus itself functions as an open-air gallery, dotted with student projects that change annually—some formal, others ephemeral, but all bound by a logic of place.

Graduates from the program have gone on to receive national and international commissions, but many choose to stay within the prefecture, teaching in high schools, running community art programs, or opening small independent galleries. One such alumna, Arai Junko, operates Gallery Den in Saitama City—a minimalist space known for showing large-scale environmental sculpture and experimental ceramics, often in partnership with the university.

The connection between the school and the community is further reinforced by its collaborations with Saitama’s technical high schools, many of which maintain strong art departments with curricula that include metalwork, mural design, and architectural modeling. This reinforces a distinctly Saitama tradition: blurring the line between fine art, industrial craft, and civic labor.

Perhaps the best example of this ethos is the “Transit Formations” project, launched in 2014, where sculpture students partnered with local train operators to create temporary art installations in unused station buildings. These works included light sculptures, video projections, and kinetic sound machines—each engaging the architectural detritus of modern transit with a sense of memory and repurposing.

Biennials, workshops, and the rebirth of regional craft

In recent years, the most vibrant pulse of contemporary art in Saitama has come not from major institutions but from regional biennials, local workshops, and craft revival initiatives. These programs reflect a deepening desire among artists and organizers to rediscover the artisanal heritage of Saitama, while pushing its forms into the realm of conceptual and social practice.

The Chichibu Art Trail, established in 2016, is a prime example. Every two years, artists from across Japan—and increasingly from overseas—are invited to create works installed along a mountainous walking route that winds through temples, farms, and abandoned houses. The works are often site-specific and temporary: a sound installation in a disused sake brewery, a video projection inside a defunct coal tunnel, or a tapestry made of local wool suspended over a dry riverbed. What distinguishes the Trail is not just the art, but the deep integration with local residents, who often host artists in their homes, cook for them, or assist in fabrication.

Similar energy animates the Kawagoe Clay Revival Workshop, which has brought together local potters, university researchers, and contemporary artists to recreate ancient Jōmon techniques using native soils and open-air kilns. The project, part craft and part conceptual archaeology, treats the act of making as both historical research and aesthetic statement. The finished objects—coiled vessels, fire-flame rims, earth-stained figures—are exhibited not in pristine galleries but in storefront windows, community centers, and schoolyards.

Three distinctive threads unite these contemporary efforts:

- Emphasis on place-based work, rooted in Saitama’s physical and cultural landscapes

- Reanimation of endangered techniques, such as sashiko embroidery, straw weaving, and urushi lacquering

- Deep collaboration between artists and non-artists, treating community as medium, not just audience