Les Nabis was an influential group of Post-Impressionist artists in France during the late 19th century. The movement, active between 1888 and 1900, sought to bridge the gap between Impressionism and modernism. Their work was characterized by bold colors, decorative elements, and symbolic themes, heavily influenced by Japanese prints and Gauguin’s Synthetism. They believed in the importance of spirituality and the mystical nature of art, rejecting realism in favor of personal expression.

The name “Nabis” is derived from the Hebrew word for “prophet,” reflecting the group’s mission to revolutionize art. Key members included Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, Maurice Denis, Paul Sérusier, and Félix Vallotton. Each artist brought a unique vision to the group, yet they shared a collective goal: to infuse everyday life with artistic beauty. Their approach went beyond painting, influencing poster design, book illustration, and interior decoration.

Les Nabis formed in response to dissatisfaction with academic painting and the rigidity of Impressionism. They sought a new visual language, emphasizing flat planes of color and decorative patterns. They drew inspiration from the works of Paul Gauguin, whose bold use of color and rejection of perspective resonated with their aesthetic ideals. Their artwork often depicted intimate, domestic scenes but with a dreamlike quality, making everyday life appear poetic.

Though their movement was short-lived, the influence of Les Nabis endured. Their emphasis on design, abstraction, and emotional resonance paved the way for later modernist movements like Fauvism and Expressionism. Today, their works are celebrated in major museums worldwide, appreciated for their innovation and beauty. By looking at Les Nabis, we gain a deeper understanding of the transition from Impressionism to modern art and the visionary artists who shaped that transformation.

Origins and Influences of Les Nabis

Les Nabis emerged in the late 1880s, rooted in the artistic ferment of Paris. At the time, Impressionism was beginning to wane, and artists sought new ways to express their ideas. The group was formed by young students at the Académie Julian, a private art school that attracted aspiring artists dissatisfied with the École des Beaux-Arts. Paul Sérusier, a key figure in the movement, played a crucial role in defining its philosophy. Under the guidance of Paul Gauguin, Sérusier created The Talisman (1888), a small yet groundbreaking painting that became the movement’s manifesto.

Gauguin’s Synthetism had a profound impact on Les Nabis, particularly its emphasis on simplified forms and vibrant colors. Japanese art, particularly woodblock prints (ukiyo-e), also heavily influenced their work, inspiring their use of flat, decorative compositions. The Nabis rejected linear perspective, opting instead for two-dimensional arrangements that emphasized emotional depth over realism. They were also inspired by the Symbolist movement, which sought to evoke spiritual and emotional experiences rather than depict the external world.

In addition to artistic influences, literature and theater played a significant role in shaping the group’s aesthetic. Symbolist writers like Stéphane Mallarmé and Maurice Maeterlinck shared their vision of transcending material reality through art. The Nabis sought to integrate visual art with literature, music, and stage design, contributing to avant-garde theatrical productions. Their belief in the mystical power of art aligned with Symbolist ideas, reinforcing their commitment to personal expression.

The group’s name, “Nabis,” was suggested by Auguste Cazalis, a poet and friend of the artists. It underscored their belief that they were artistic prophets, destined to lead a new movement. Unlike the Impressionists, who focused on light and naturalistic scenes, the Nabis saw art as a vehicle for emotion and spirituality. Their bold approach set the stage for the vibrant and expressive art movements that would follow.

Key Members and Their Contributions

Les Nabis consisted of a core group of artists, each bringing their own style and perspective. Pierre Bonnard was one of the most prominent members, known for his vibrant use of color and intimate domestic scenes. His paintings often depicted everyday moments, yet he infused them with a dreamlike atmosphere. His later works, particularly those of interiors and still lifes, influenced later generations of modern painters.

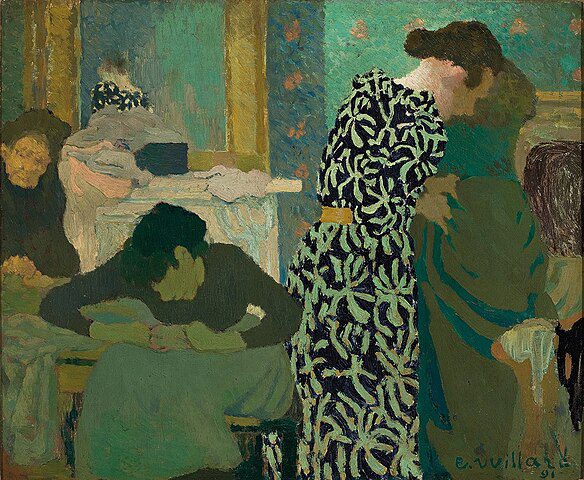

Édouard Vuillard specialized in interior scenes featuring intricate patterns and subdued colors. He had a keen eye for detail, capturing the quiet, introspective moments of daily life. Vuillard’s work was deeply personal, often depicting his family members and close friends. His compositions blurred the line between figure and background, creating a tapestry-like effect that emphasized decoration.

Maurice Denis was the philosophical voice of the group, articulating its principles through his writings. In 1890, he famously stated, “A painting, before being a battle horse, a nude woman, or some sort of anecdote, is essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order.” His religious faith also played a significant role in his art, as he explored Christian themes with a modern sensibility. His work bridged the gap between the Nabis and later Symbolist painters.

Paul Sérusier and Félix Vallotton contributed unique perspectives to the movement. Sérusier, under Gauguin’s mentorship, developed an abstract approach that emphasized bold colors and simplified shapes. Vallotton, on the other hand, brought a sharper, more graphic sensibility to the group, particularly in his woodcuts. His stark contrasts and satirical tone distinguished him from his peers, yet he remained deeply involved in the Nabis’ explorations of design and narrative.

The Talisman: The Birth of a Movement

One of the most defining moments of Les Nabis was the creation of The Talisman in 1888. Painted by Paul Sérusier under the guidance of Paul Gauguin, this small yet revolutionary work symbolized the group’s break from traditional painting. Sérusier painted it on a wooden cigar box lid while visiting Pont-Aven, a Breton village where Gauguin had established an artist colony. The painting’s bold colors and abstract forms shocked many but inspired his fellow students.

The Talisman was not merely an artwork but a manifesto for a new artistic vision. It rejected perspective and naturalistic shading, instead using intense colors and simplified shapes. This approach emphasized emotional expression over realism, a principle that became central to the Nabis. The painting’s title reflects its mystical significance, as the group saw it as a guiding force in their artistic journey.

When Sérusier returned to Paris, he showed The Talisman to his classmates at the Académie Julian. The painting’s unconventional style intrigued them, leading to the formation of Les Nabis. Maurice Denis, Pierre Bonnard, and Édouard Vuillard were particularly captivated by its radical departure from academic traditions. They recognized it as a declaration of independence from established artistic norms, encouraging them to experiment further.

Today, The Talisman is housed in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, where it is regarded as a seminal work of modern art. It encapsulates the Nabis’ core ideals: the rejection of realism, the pursuit of personal expression, and the belief in art as a spiritual act. Its legacy endures, serving as a symbol of artistic liberation and innovation.

Symbolism and Spirituality in Nabis Art

Les Nabis were deeply influenced by the Symbolist movement, which emphasized emotional depth and mystical themes. Rather than merely depicting the physical world, they sought to express the unseen—feelings, dreams, and spirituality—through their paintings. This approach aligned with Symbolist poets and writers of the time, such as Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Verlaine, who believed that art should evoke rather than describe. By integrating these ideas into their work, the Nabis moved beyond realism, creating a more profound connection between the viewer and the artwork.

Maurice Denis was the most overtly spiritual member of the group, and his paintings often contained Christian themes. He saw art as a form of devotion, a way to bridge the human and the divine. His work, such as The Mystical Nativity (1891), blended religious iconography with modern artistic techniques, demonstrating how faith could be reinterpreted in a contemporary context. His writings also reinforced this vision, particularly his statement that painting was “essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order.” This idea emphasized the spiritual and decorative qualities of painting over its representational function.

Other Nabis artists embraced spirituality in a more abstract way. Paul Sérusier, for instance, was drawn to esoteric philosophies and the idea that colors and shapes carried symbolic meanings. His works often featured enigmatic compositions that suggested hidden narratives or deeper truths. This fascination with the mystical was also evident in the works of Jan Verkade, a lesser-known Nabis painter who later became a Benedictine monk. Verkade’s paintings reflected his belief in the transcendental power of art, reinforcing the group’s broader interest in the unseen forces that shape existence.

The Nabis also experimented with the depiction of dreams and psychological states, inspired by the Symbolist fascination with the subconscious. Édouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard, for example, infused their domestic scenes with a dreamlike quality, where light, color, and texture merged in a way that suggested memory rather than mere observation. These interiors, filled with patterned wallpapers and soft, diffused light, had an intimate, almost hypnotic effect. Through these techniques, the Nabis demonstrated that the everyday world could be a gateway to deeper, more spiritual experiences.

The Nabis and Decorative Arts

Beyond painting, the Nabis had a significant impact on the decorative arts. They rejected the idea that fine art should be separate from everyday life, instead advocating for the integration of art into all aspects of living. This belief led them to work in a variety of mediums, including furniture design, wallpaper, textiles, and stained glass. Their influence extended into the burgeoning Art Nouveau movement, which sought to merge beauty and function in domestic spaces.

One of the key figures in this decorative approach was Pierre Bonnard, who designed posters and book illustrations alongside his paintings. His work with the famous art dealer and publisher Ambroise Vollard helped popularize the idea that printed materials could be as aesthetically significant as traditional painting. The flat planes of color and stylized figures in his posters reflected the influence of Japanese prints while maintaining the Nabis’ emphasis on emotion and design. His lithographs for La Revue Blanche, a leading avant-garde publication of the 1890s, were especially notable for their elegance and originality.

Édouard Vuillard also contributed significantly to the decorative arts, particularly in the realm of interior decoration. His large-scale murals adorned private homes and public buildings, blurring the boundaries between painting and architecture. His compositions, often featuring intimate domestic scenes, were designed to harmonize with their surroundings rather than dominate them. This holistic approach to art-making was in keeping with the Nabis’ belief that art should be an integral part of everyday life, rather than confined to museums and galleries.

Maurice Denis took this concept even further, working on large-scale decorative projects for churches and theaters. His murals for the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris demonstrated his ability to adapt the Nabis aesthetic to monumental public spaces. By emphasizing rhythmic patterns, flowing lines, and harmonious color schemes, he created immersive environments that transformed the viewer’s experience of a space. His religious murals, such as those at the Benedictine abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, reinforced his belief that art could serve both spiritual and decorative purposes.

Legacy and Influence of Les Nabis

Although the Nabis movement dissolved around 1900, its influence continued to shape modern art. Many of its members went on to have successful careers, contributing to subsequent artistic developments. Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard became prominent figures in early 20th-century painting, continuing to explore color and composition in ways that would influence later modernist movements. Bonnard’s later work, in particular, anticipated the color innovations of the Fauves, a group that included Henri Matisse and André Derain.

Maurice Denis remained an important art theorist and writer, advocating for the continued integration of decorative arts into modern life. His writings influenced later artists and designers, particularly those involved in the Arts and Crafts movement and Art Deco. His emphasis on spirituality in art also had a lasting impact, resonating with later Symbolist painters and religious artists. By articulating the idea that form and color were more important than subject matter, Denis helped lay the groundwork for abstraction.

Paul Sérusier continued to explore mystical and esoteric themes in his work, further developing the abstract tendencies that had first appeared in The Talisman. His later paintings, though less well known, contained many of the same bold colors and symbolic meanings that characterized his early Nabis work. He also became involved in teaching, passing on the group’s ideas to a new generation of artists.

The legacy of Les Nabis is evident in the continued appreciation of their work in museums and exhibitions worldwide. Their rejection of realism, embrace of decorative principles, and commitment to emotional expression helped bridge the gap between 19th-century art and the bold innovations of the 20th century. While their movement was relatively short-lived, their ideas had a lasting impact on modern art, influencing not only painting but also graphic design, interior decoration, and theater.

Key Takeaways

- Les Nabis was a group of late 19th-century French artists who sought to bridge Impressionism and modernism.

- Their work was influenced by Gauguin’s Synthetism, Japanese prints, and Symbolism, emphasizing emotion and spirituality.

- Key members included Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, Maurice Denis, Paul Sérusier, and Félix Vallotton.

- The Nabis extended their artistic vision beyond painting, influencing decorative arts, theater design, and book illustration.

- Though the movement dissolved around 1900, its ideas influenced Fauvism, Art Nouveau, and modern abstract art.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What does “Nabis” mean?

The word “Nabis” comes from the Hebrew word for “prophet,” reflecting the group’s belief that they were artistic visionaries.

Who were the main members of Les Nabis?

The core members included Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, Maurice Denis, Paul Sérusier, and Félix Vallotton. Each artist contributed unique styles and perspectives.

What was the significance of The Talisman?

The Talisman, painted by Paul Sérusier in 1888, was a manifesto of Nabis art, rejecting realism in favor of bold colors and symbolic abstraction.

How did Les Nabis influence later art movements?

Their emphasis on color, composition, and decoration influenced Fauvism, Art Nouveau, and modernist abstraction, shaping 20th-century art.

Where can I see works by Les Nabis today?

Their works are featured in major museums worldwide, including the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Tate Modern in London.