Can you feel the sunlight flickering through trees? Or hear the clatter of a bustling Parisian café at twilight? Impressionism wasn’t just a style of painting; it was a radical shift in how artists viewed and captured the world. It wasn’t about details but rather the overall impression—how light danced, how colors vibrated, how moments felt.

Origins of Impressionism

Picture Paris in the mid-19th century: cobblestones, cafés, and a growing sense of change. The city wasn’t just the capital of France—it was the heart of Western art. The Académie des Beaux-Arts was the gatekeeper of artistic success, promoting grand historical paintings and mythological themes. It was all about realism, polish, and moral stories—what was often called “Academic Art.”

The annual Salon de Paris exhibition, organized by the Académie, was the most prestigious art event. Acceptance meant fame; rejection could end a career. But the rules were strict: large canvases, classical subjects, and realistic details. The judges were conservative, favoring works that were carefully finished, blending brushstrokes into an almost photographic realism.

However, the city was changing. The industrial revolution brought new railways, factories, and a bustling urban environment that intrigued younger artists. They wanted to paint the world they saw around them—lively streets, working-class life, and natural landscapes. Meanwhile, the advent of photography in the 1830s and 1840s raised questions about the role of painting. Why compete with a camera’s accuracy? The new goal became capturing the fleeting, subjective experience of a moment.

A turning point came in 1863, with the creation of the Salon des Refusés (Salon of the Rejected). This alternative exhibition was set up by Emperor Napoleon III in response to protests over rejected works from the official Salon. It featured paintings like Édouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863), which scandalized viewers with its modern, unconventional subject. Though not technically Impressionist, Manet’s rebellion against tradition inspired many younger artists.

The Birth of Impressionism

The birth of Impressionism is often marked by the 1874 exhibition organized by the Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs (Cooperative and Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers). This bold move bypassed the Salon entirely, with the exhibition held at Nadar’s photography studio on Boulevard des Capucines in Paris.

Among the works was Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872), a hazy depiction of Le Havre harbor at dawn. It was this painting that prompted critic Louis Leroy to mock the artists in Le Charivari, calling their work mere “impressions.” The term stuck, and the artists adopted it as the name for their movement.

Impressionists aimed to capture the effects of light, movement, and color in a way that felt spontaneous and immediate. Their paintings were often described as “unfinished” due to their sketch-like appearance, with visible brushstrokes and vivid colors that conveyed mood rather than detail. Unlike the carefully blended realism of Academic Art, Impressionism celebrated roughness and imperfection.

During the early exhibitions, the response from critics and the public was mixed. Many criticized the works as crude or incomplete. Still, the artists were undeterred. Monet, Renoir, Degas, Pissarro, and Morisot were among the key figures who continued to exhibit together, organizing eight exhibitions between 1874 and 1886.

The Key Figures of Impressionism

Claude Monet: The Light Chaser

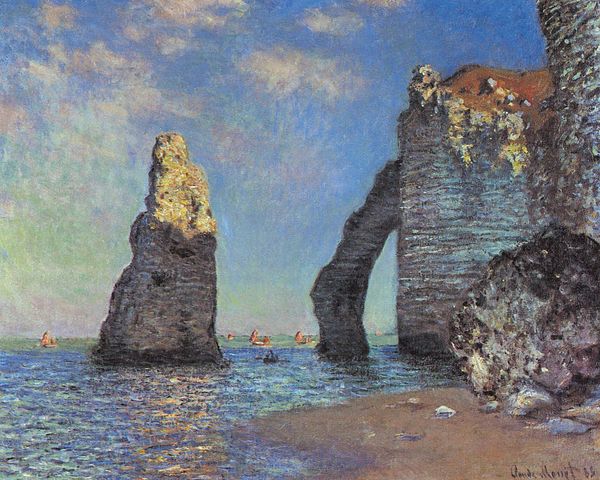

Claude Monet is often considered the leader of Impressionism. Born in Paris in 1840, Monet’s early years were filled with financial struggles and repeated rejections from the Salon. His passion, however, was unwavering. He focused on capturing light, color, and atmosphere in a way that felt almost tangible.

Monet often painted the same scene multiple times to show the changing effects of light throughout the day. His series paintings, such as the Rouen Cathedral, Haystacks, and Water Lilies, are iconic. In the Haystacks series (1890-1891), Monet painted the same haystacks at different times of day and in different weather, revealing how light could transform a simple subject.

Despite early struggles, Monet achieved considerable success by the 1890s, with his work becoming widely celebrated. He spent his later years in Giverny, where he created his Water Lilies series, a project that consumed him for decades and symbolized his dedication to capturing fleeting impressions of nature.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir: The Painter of Joy

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, born in 1841, began his artistic career as a painter of porcelain before attending the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Renoir’s work is known for its warm colors, loose brushstrokes, and depictions of joyful scenes. His paintings often featured lively social gatherings, such as Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette (1876), which captures a sunlit afternoon in Montmartre.

Renoir’s famous Luncheon of the Boating Party (1881) exemplifies the Impressionist spirit, combining elements of portraiture, still life, and landscape. It portrays a group of Renoir’s friends enjoying a relaxed lunch by the Seine, encapsulating the carefree nature of the movement.

In the 1880s, Renoir’s style became more classical, emphasizing line and form. This shift, known as his “Ingres period,” was influenced by the neoclassical artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Although Renoir experimented with a more traditional approach, he remained associated with Impressionism due to his continued focus on capturing light and color.

Edgar Degas: The Observer of Movement

Edgar Degas, born in 1834, was one of the oldest and most unconventional Impressionists. Unlike his peers, Degas rarely painted landscapes or outdoors. Instead, he focused on indoor scenes—ballet studios, cafés, and racecourses—where he could observe human movement. Degas’ painting The Dance Class (1874) is a prime example, showing ballerinas in rehearsal with light streaming through the windows.

Degas often used unusual angles and cropping in his compositions, giving his works a sense of immediacy and spontaneity. His method, however, was anything but spontaneous; Degas planned his paintings meticulously, often using pastels for their rich, layered textures. He famously stated, “No art was ever less spontaneous than mine.”

Despite his differences with other Impressionists, Degas was a crucial part of the movement, participating in nearly all the group exhibitions. His work brought a psychological depth that complemented the lighter themes of his contemporaries.

Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt: Women of Impressionism

Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt were among the few women who found success within the male-dominated world of Impressionism. Morisot, born in 1841, was known for her soft, airy brushwork and focus on domestic life. Her painting The Cradle (1872) portrays a mother watching over her sleeping child, a scene filled with intimacy and tenderness.

Cassatt, an American expatriate who settled in Paris, often depicted mothers and children in her work. Her painting The Child’s Bath (1893) shows her distinctive use of strong lines and flattened space, influenced by Japanese art. Cassatt was also a vocal advocate for women’s rights, using her art to offer nuanced insights into women’s lives.

Both Morisot and Cassatt were instrumental in promoting Impressionism. Morisot helped organize exhibitions, while Cassatt played a key role in introducing the movement to American collectors, boosting its international presence.

Impressionism’s Techniques and Innovations

Impressionism introduced several key innovations that set it apart from traditional art:

- Broken Brushstrokes: Artists applied paint in short, quick strokes, creating a vibrating effect that captured movement.

- Bright Colors: Unmixed colors were often used to depict natural light, with complementary colors placed side by side to enhance contrast.

- En Plein Air: Painting outdoors allowed artists to capture natural light directly, a departure from the controlled lighting of studios.

- Japanese Influence: Impressionists were inspired by Japanese prints, which featured flat color planes, strong outlines, and unusual perspectives.

These techniques were not just stylistic choices—they were a deliberate attempt to depict the sensory experience of a scene rather than a precise representation of it.

Major Exhibitions and Public Reaction

Between 1874 and 1886, the Impressionists held eight exhibitions, each one pushing boundaries and challenging critics. The second exhibition, in 1876, featured notable works like Renoir’s Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette, Monet’s The Seine at Argenteuil, and Morisot’s Reading.

Public reaction was mixed. Critics often labeled the works as “unfinished” or “childlike.” However, the exhibitions gradually attracted more positive attention, especially among younger artists and collectors who appreciated the fresh approach. By the 1880s, dealers like Paul Durand-Ruel began to see the commercial potential of Impressionist art, helping the movement gain financial success.

Influence on Later Movements

Impressionism laid the foundation for later movements like Post-Impressionism, Neo-Impressionism, and even elements of Fauvism and Cubism. Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cézanne adopted Impressionism’s color focus but added more structure and emotional depth. Georges Seurat’s Neo-Impressionism, marked by Pointillism, built on Impressionist ideas of optical color mixing.

The emphasis on light, color, and immediacy in Impressionism also influenced modern photography and cinema, where natural lighting and spontaneous composition became valued techniques.

“It took me time to understand my water lilies. I had planted them for pleasure; I grew them without thinking of painting them.” — Claude Monet

FAQs

- What is Impressionism?

Impressionism is an art movement that emerged in 19th-century France, focusing on capturing light, color, and fleeting moments. - Who started Impressionism?

Artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Edgar Degas are credited with founding Impressionism. - Why is Impressionism important?

It broke away from formal painting styles, paving the way for modern art. - What are some famous Impressionist paintings?

Impression, Sunrise by Monet, Luncheon of the Boating Party by Renoir, and The Ballet Class by Degas. - How did Impressionism influence modern art?

It inspired later movements like Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and aspects of abstract art.

Key Takeaways

- Impressionism focused on light, movement, and capturing real-life scenes.

- The first exhibition in 1874 marked the birth of the movement, despite initial criticism.

- The movement had a lasting influence on modern art and techniques.