Spain’s art history is a testament to its complex and dynamic cultural identity. As a crossroads of civilizations, Spain has been shaped by influences from prehistoric settlers, Romans, Visigoths, Moors, and the Catholic monarchy, resulting in a uniquely layered artistic legacy. This blend of traditions created a vibrant and diverse art scene, spanning from the cave paintings of Altamira to the surrealist dreams of Dalí, and from the soaring Gothic cathedrals to the groundbreaking works of Picasso.

Spanish art is characterized by its emotional intensity, innovative spirit, and deep connection to cultural and religious identity. During the Spanish Golden Age, artists like Velázquez and El Greco redefined painting with their masterful use of light, composition, and symbolism. In the 20th century, Spain became a hub of modernist experimentation, producing some of the most influential figures in art history, including Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, and Salvador Dalí.

Today, Spain’s art continues to captivate global audiences, preserved in world-renowned institutions such as the Prado Museum in Madrid, the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, and the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona. Its legacy serves as a source of inspiration, reflecting centuries of innovation, resilience, and a profound connection to the human experience.

Chapter 1: Prehistoric and Early Iberian Art

Spain’s artistic journey begins in prehistory, with some of the world’s most remarkable examples of early human creativity found in its caves and landscapes. Over thousands of years, prehistoric settlers and early Iberian civilizations developed artistic traditions that would form the foundation of Spain’s cultural identity. From the haunting cave paintings of Altamira to the intricate sculptures of early Iberian tribes, this period reflects humanity’s first attempts to express ideas, beliefs, and emotions through art.

The Cave of Altamira: A Prehistoric Masterpiece

- Discovered in 1868 and dubbed the “Sistine Chapel of Prehistoric Art,” the Cave of Altamira in northern Spain features some of the finest examples of Paleolithic cave paintings.

- Artistic Features:

- Created around 36,000 to 13,000 BCE, the paintings depict bison, deer, horses, and wild boar in vivid earth tones derived from natural pigments.

- Artists used advanced techniques such as shading, engraving, and the contours of the cave walls to create a sense of volume and movement.

- Cultural Significance:

- These paintings are believed to have held spiritual or ritualistic purposes, connecting early humans with the animals and natural forces that sustained their lives.

- The discovery of Altamira revolutionized our understanding of prehistoric art, proving that early humans were capable of extraordinary artistic expression.

- Artistic Features:

Iberian Art: Sculptures and Symbols of a Complex Society

- By the first millennium BCE, the Iberian Peninsula was home to advanced civilizations that developed a distinct artistic identity.

- Sculptural Masterpieces:

- The Lady of Elche (circa 4th century BCE), a limestone bust adorned with intricate headdress and jewelry, exemplifies Iberian craftsmanship and aesthetic sophistication. It reflects influences from Mediterranean cultures such as the Phoenicians and Greeks.

- The Lady of Baza (circa 4th century BCE) combines funerary and religious elements, showcasing the Iberian tradition of creating detailed burial statues.

- Bronze and Ceramic Works:

- Iberian artisans excelled in creating bronze weapons, tools, and ceremonial objects, often decorated with geometric patterns and animal motifs.

- Pottery from this era, including urns and amphorae, features vibrant painted designs and reflects both local traditions and Mediterranean trade influences.

- Sculptural Masterpieces:

Rock Art of the Mediterranean Basin

- In addition to Altamira, Spain is home to numerous examples of Levantine Rock Art, dating from around 10,000 BCE to 5,000 BCE.

- Found in regions such as Catalonia and Valencia, these paintings depict scenes of hunting, dancing, and communal rituals, often using stick-figure representations of humans and animals.

- This art highlights the evolution of human storytelling and social organization, with depictions of group activities suggesting the beginnings of complex societal structures.

The Celtiberians and Artistic Fusion

- The Celtiberians, a hybrid culture that emerged from the blending of Iberian and Celtic tribes, contributed to Spain’s artistic heritage through metalwork and sculpture.

- Toros de Guisando: These granite sculptures of bulls, created between the 4th and 2nd centuries BCE, reflect both religious and agricultural significance, symbolizing fertility and strength.

- Warrior Statuettes: Celtiberian warriors were often depicted in intricate bronze statuettes, emphasizing the importance of martial valor in their culture.

Legacy of Prehistoric and Early Iberian Art

- Spain’s prehistoric and early Iberian art demonstrates humanity’s enduring need to create and communicate, capturing the spiritual, social, and practical concerns of ancient peoples.

- The fusion of local traditions with Mediterranean influences during the Iberian period laid the groundwork for Spain’s later artistic developments, reflecting a dynamic cultural exchange that would define the nation’s identity.

- Today, many of these artifacts, such as the Lady of Elche and the paintings of Altamira, are preserved in institutions like the National Archaeological Museum in Madrid, serving as powerful reminders of Spain’s ancient roots.

Chapter 2: Roman and Visigothic Art in Spain

The Roman conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in the 3rd century BCE marked the beginning of a transformative period in Spain’s artistic and cultural history. The Romans introduced their advanced engineering, architectural, and artistic techniques, leaving behind enduring landmarks. After the fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century CE, the Visigoths inherited this legacy and blended it with their own traditions, resulting in a unique fusion of styles that bridged classical antiquity and the medieval period.

Roman Art and Architecture in Hispania

- The Romans established Hispania as a vital part of their empire, leaving a profound impact on its urban planning, architecture, and decorative arts.

- Engineering Marvels:

- The Aqueduct of Segovia, constructed in the 1st century CE, stands as a testament to Roman engineering prowess. Built without mortar, its precision and durability have ensured its preservation as a functional structure into modern times.

- The Roman Bridge of Córdoba, spanning the Guadalquivir River, showcases the Romans’ expertise in creating enduring infrastructure.

- Monumental Architecture:

- The Theatre of Mérida, built in the 1st century BCE, is one of the best-preserved Roman theaters in the world. It could seat up to 6,000 spectators and hosted a variety of performances and ceremonies.

- The Temple of Diana in Mérida, dedicated to the Roman goddess, exemplifies the classical proportions and decorative richness of Roman temple design.

- Mosaics and Decorative Arts:

- Roman villas across Hispania, such as those in Itálica and Empúries, featured intricate mosaics depicting mythological scenes, daily life, and geometric patterns. These works demonstrate the Romans’ mastery of color, composition, and storytelling.

- Engineering Marvels:

The Transition to Visigothic Art

- The collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century CE saw the Visigoths, a Germanic tribe, establish their rule over Hispania. While retaining many Roman artistic traditions, the Visigoths introduced their own distinct styles, particularly in religious art.

- Visigothic Churches:

- The Church of San Juan de Baños (7th century), located in Palencia, is a quintessential example of Visigothic architecture. Its horseshoe arches and simple yet sturdy construction reflect both Roman influence and the Visigoths’ preference for practicality.

- Santa María de Quintanilla de las Viñas features ornate stone reliefs depicting biblical scenes and symbolic motifs, showcasing the Visigoths’ skill in sculpture and their focus on Christian themes.

- Metalwork and Jewelry:

- Visigothic artisans excelled in creating intricate gold and gemstone jewelry, often with religious significance. Examples include the Treasure of Guarrazar, a collection of 7th-century votive crowns and crosses adorned with pearls and sapphires, symbolizing royal and divine authority.

- Manuscripts:

- Though rare, Visigothic illuminated manuscripts demonstrate a blend of Roman calligraphic traditions and unique Christian iconography, serving both liturgical and decorative purposes.

- Visigothic Churches:

The Fusion of Roman and Visigothic Styles

- The Visigoths adopted and adapted Roman artistic and architectural techniques, creating a hybrid style that bridged antiquity and the medieval period.

- Horseshoe Arch: The Visigoths refined the horseshoe arch, which would later become a hallmark of Islamic architecture in Al-Andalus.

- Religious Symbolism: Both Roman and Visigothic art placed a strong emphasis on religious themes, with the Visigoths introducing a more symbolic and less naturalistic approach to figures and ornamentation.

Legacy of Roman and Visigothic Art in Spain

- Roman art and architecture in Hispania established a foundation of innovation and grandeur that influenced Spanish art for centuries, from the design of medieval cathedrals to modern infrastructure.

- The Visigoths’ contributions, though often overshadowed by Roman and Islamic achievements, provided a vital link between the classical and medieval periods, particularly in religious architecture and metalwork.

- Landmarks like the Aqueduct of Segovia and treasures such as the Guarrazar votive crowns remain iconic symbols of Spain’s cultural heritage, drawing visitors and scholars alike.

Chapter 3: Islamic and Mudéjar Art in Spain (8th–15th Century)

The Islamic conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in 711 CE marked the beginning of one of the most influential periods in Spanish art and architecture. Under Muslim rule, the region known as Al-Andalus became a cultural and artistic hub, blending Islamic traditions with local and classical influences. This period gave rise to some of Spain’s most iconic landmarks, while the coexistence of Muslim, Christian, and Jewish communities fostered the development of the Mudéjar style, a uniquely Spanish synthesis of Islamic and Christian aesthetics.

Islamic Art in Al-Andalus

- The art and architecture of Al-Andalus flourished under the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba, the Taifa kingdoms, and the Nasrid Dynasty of Granada, leaving an enduring legacy of refinement and innovation.

The Great Mosque of Córdoba (8th–10th Century)

- One of the most significant examples of Islamic art in Spain, the Great Mosque of Córdoba showcases the grandeur and ingenuity of Umayyad architecture.

- Architectural Features:

- The horseshoe arches, an evolution of Visigothic forms, and the alternating red-and-white voussoirs create a mesmerizing effect.

- The mihrab (prayer niche) is adorned with intricate mosaics and Arabic calligraphy, reflecting the mosque’s spiritual significance.

- Later expansions under Abd al-Rahman III and Al-Hakam II introduced domed ceilings and elaborate maqsuras (private prayer spaces for the elite).

- Cultural Significance:

- The mosque served as a center of worship, education, and cultural exchange, symbolizing the wealth and power of Al-Andalus.

- Architectural Features:

The Alhambra of Granada (13th–14th Century)

- The Alhambra, built during the Nasrid Dynasty, is a masterpiece of Islamic art and architecture, blending practical fortifications with breathtaking palatial elegance.

- Architectural Features:

- The Court of the Lions, with its central fountain supported by twelve intricately carved lion statues, exemplifies the harmony of form and function.

- The Hall of the Ambassadors features muqarnas (stalactite-like decorations) and geometric patterns that reflect the Islamic emphasis on symmetry and abstraction.

- Cultural Legacy:

- The Alhambra symbolizes the sophistication of Islamic Spain, drawing millions of visitors each year and influencing architects and artists worldwide.

- Architectural Features:

Mudéjar Art: A Fusion of Traditions

- Following the Christian Reconquista, many Muslim artisans remained in Spain, contributing to the development of the Mudéjar style. This style blended Islamic decorative techniques with Christian architectural forms, creating a uniquely Spanish aesthetic.

Key Features of Mudéjar Art

- Geometric Patterns: Intricate tilework (azulejos), wood carvings, and plaster decorations showcased Islamic design principles.

- Horseshoe and Pointed Arches: Adapted from Islamic architecture, these features became common in Christian churches and palaces.

- Brickwork and Domes: Mudéjar structures often utilized brick as a primary material, adorned with elaborate plaster or ceramic ornamentation.

Prominent Mudéjar Structures

- The Alcázar of Seville:

- Originally a Moorish fortress, the Alcázar was transformed by Christian rulers into a Mudéjar palace, combining Islamic and Gothic elements.

- The Ambassadors’ Hall features a domed ceiling adorned with gilded wood and geometric patterns.

- The Church of San Pablo in Zaragoza:

- Built in the 14th century, this church incorporates Mudéjar brickwork and decorative arches, showcasing the style’s integration into Christian religious architecture.

The Influence of Islamic Art on Spanish Culture

- Calligraphy and Ornamentation:

- Arabic calligraphy and vegetal motifs became integral to Spanish decorative arts, influencing textiles, ceramics, and metalwork.

- The use of intricate designs and vibrant colors became hallmarks of Spanish art, enduring even after the Reconquista.

- Scientific and Artistic Exchange:

- Al-Andalus was a center of learning, where advancements in mathematics, astronomy, and medicine influenced both art and science. This legacy would later inform the European Renaissance.

Legacy of Islamic and Mudéjar Art

- Islamic and Mudéjar art remain defining aspects of Spain’s cultural identity, illustrating the profound impact of cross-cultural exchange and coexistence.

- Masterpieces like the Alhambra and the Great Mosque of Córdoba continue to inspire architects, artists, and historians, serving as enduring symbols of Spain’s multicultural heritage.

- The Mudéjar style, with its seamless integration of Islamic and Christian elements, stands as a testament to the enduring power of artistic synthesis in bridging cultural divides.

Chapter 4: Gothic and Early Renaissance Art in Spain (13th–15th Century)

The Gothic and Early Renaissance periods in Spain were characterized by a flourishing of monumental architecture, elaborate religious art, and the gradual integration of humanist ideas from Italy. During this time, Spanish artists and architects began to develop a unique visual language, blending Gothic styles with influences from Islamic and Mudéjar traditions. The Catholic Church played a central role, commissioning cathedrals, altarpieces, and sculptures that reflected the spiritual and political aspirations of the era.

Gothic Architecture: Majestic Cathedrals and Urban Transformation

- Gothic architecture arrived in Spain in the late 12th century and reached its height in the 13th and 14th centuries. It marked a shift from Romanesque solidity to verticality, light, and intricacy.

Key Gothic Cathedrals

- Cathedral of Burgos (1221–1567):

- One of the finest examples of Spanish Gothic architecture, this cathedral was influenced by French Gothic but incorporated local decorative elements.

- The rose windows, spires, and richly carved portals exemplify the era’s emphasis on height and ornamentation.

- Seville Cathedral (1401–1506):

- Built on the site of a former mosque, this massive cathedral reflects the transition from Gothic to Renaissance styles. It remains the largest Gothic cathedral in the world.

- The Giralda Tower, originally a minaret, was repurposed as a bell tower, blending Gothic and Islamic elements.

- Cathedral of Toledo (1226–1493):

- Known as the “Magnum Opus of Gothic Architecture in Spain,” Toledo’s cathedral features stunning stained glass, intricate choir stalls, and a dazzling altarpiece known as the Transparente.

Mudéjar Influence in Gothic Architecture

- Many Gothic cathedrals incorporated Mudéjar elements, such as decorative tilework, horseshoe arches, and carved wood ceilings, reflecting Spain’s multicultural heritage.

Altarpieces and Religious Painting

- Gothic altarpieces (retablos) became a hallmark of Spanish religious art, featuring complex narratives and vivid imagery to inspire devotion.

- Master of Ávila: An anonymous Gothic painter known for richly colored panels depicting saints and biblical scenes, such as the Altarpiece of Saint Michael.

- Bartolomé Bermejo: A master of the late Gothic period, Bermejo’s works, like Saint Michael Triumphs over the Devil (1468), exhibit a remarkable attention to detail and emotion.

The Role of Sculpture

- Gothic sculpture in Spain was characterized by lifelike depictions of religious figures, emphasizing pathos and spirituality.

- Wooden polychrome sculptures, such as crucifixes and Madonna figures, were often painted in vivid colors to enhance their realism.

- The Cathedral of León houses a series of Gothic statues that exemplify the era’s intricate craftsmanship and expressive detail.

Early Renaissance Art in Spain

- By the 15th century, the influence of the Italian Renaissance began to permeate Spanish art, marking a shift toward humanism and naturalism.

- Italian Influence:

- Artists and architects traveled to Italy to study classical forms, bringing back ideas of proportion, perspective, and anatomical accuracy.

- The Cardinal Cisneros Altarpiece in Toledo Cathedral combines Gothic intricacy with Renaissance harmony.

- Flemish Connections:

- The Habsburg monarchy facilitated cultural exchange between Spain and Flanders, introducing Flemish oil painting techniques and detailed realism.

- Works by Flemish masters like Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden influenced Spanish artists, leading to a fusion of Northern and Southern European styles.

- Italian Influence:

Key Figures in the Early Renaissance

- Pedro Berruguete:

- Known as the first Spanish Renaissance painter, Berruguete’s works, such as Saint Dominic Presiding over an Auto-da-Fé (c. 1495), blend Gothic composition with Renaissance naturalism.

- Fernando Gallego:

- A transitional figure between Gothic and Renaissance styles, Gallego’s altarpieces feature detailed landscapes and emotionally charged figures.

Legacy of the Gothic and Early Renaissance Periods

- The Gothic and Early Renaissance periods established Spain as a center of monumental religious art and architecture, showcasing the nation’s spiritual fervor and artistic ambition.

- The integration of Mudéjar, Flemish, and Italian influences during this time laid the groundwork for the Spanish Golden Age, when these traditions would reach their zenith.

- Landmarks like the Cathedral of Seville and masterpieces by artists like Bartolomé Bermejo continue to captivate audiences, reflecting the enduring power of this pivotal era in Spanish art.

Chapter 5: The Spanish Golden Age (16th–17th Century)

The Spanish Golden Age (Siglo de Oro) marked an unparalleled flourishing of art and culture in Spain, driven by the nation’s political dominance, religious fervor, and the patronage of the Catholic monarchy and the Church. During this period, Spanish art reached new heights, with painters, sculptors, and architects creating masterpieces that reflected the dramatic, spiritual, and often somber ethos of the time. The Baroque style became dominant, emphasizing grandeur, emotion, and the interplay of light and shadow.

Religious Art and the Counter-Reformation

- The Catholic Church, responding to the Protestant Reformation, used art as a tool for religious devotion and propaganda. Spanish artists rose to the occasion, producing works that were deeply spiritual and emotionally evocative.

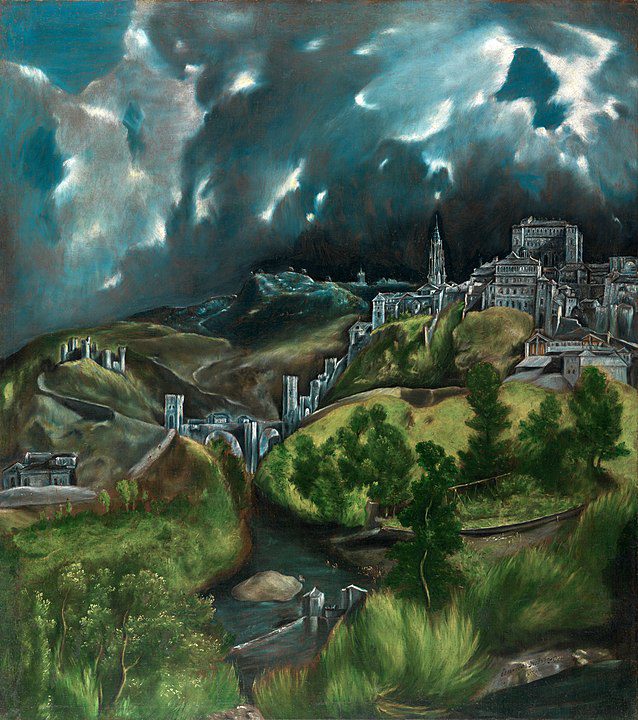

- El Greco:

- Born in Crete and trained in Italy, El Greco became one of the most iconic painters of the Spanish Golden Age.

- His works, such as The Burial of the Count of Orgaz (1586), are characterized by elongated figures, dramatic compositions, and a mystical use of light, reflecting both Mannerist and Baroque influences.

- El Greco’s art was deeply spiritual, often depicting visionary scenes that bridged the earthly and divine.

- Francisco de Zurbarán:

- Known as the “painter of monks,” Zurbarán specialized in religious paintings that conveyed a sense of quiet devotion and spiritual intensity.

- His works, such as Saint Serapion (1628), emphasize stark contrasts between light and shadow, lending his subjects an ethereal presence.

- El Greco:

Diego Velázquez: The Master of Realism

- Diego Velázquez (1599–1660) is widely regarded as one of the greatest painters in history, celebrated for his technical mastery and innovative compositions.

- Court Painter to Philip IV:

- As the official court painter, Velázquez created portraits that captured the humanity and complexity of his subjects, including Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1650) and Las Meninas (1656), his most famous work.

- Las Meninas is a masterful exploration of perspective, light, and the relationship between the artist, subject, and viewer, making it one of the most studied paintings in Western art.

- Genre Painting:

- Velázquez’s early works, such as Old Woman Frying Eggs (1618), demonstrate his ability to elevate everyday scenes to high art through meticulous attention to detail and dramatic use of light.

- Court Painter to Philip IV:

Baroque Sculpture: Pathos and Realism

- Spanish Baroque sculpture reached new heights during the Golden Age, with artists creating lifelike representations of religious figures that were both dramatic and deeply emotional.

- Gregorio Fernández:

- Fernández’s polychrome sculptures, such as Christ Carrying the Cross (1619), are noted for their vivid realism and emotional intensity, designed to inspire devotion among viewers.

- Juan Martínez Montañés:

- Known as the “God of Wood,” Montañés created exquisitely detailed wooden sculptures, such as the Crucifixion of El Escorial, blending anatomical accuracy with spiritual expression.

- Gregorio Fernández:

The Architecture of Grandeur

- Baroque architecture in Spain emphasized grandeur and ornamentation, with a focus on creating spaces that inspired awe and reverence.

- El Escorial:

- Built during the reign of Philip II, El Escorial served as a royal palace, monastery, and mausoleum. Its austere exterior contrasts with its richly decorated interiors, reflecting Philip’s piety and power.

- Granada Charterhouse:

- This Carthusian monastery is one of the most ornate examples of Spanish Baroque architecture, with its lavishly gilded altar and intricate stucco decorations.

- El Escorial:

Secular Art and Literature

- While religious art dominated, the Spanish Golden Age also saw the rise of secular themes, particularly in portraiture and literature.

- Portraiture:

- In addition to Velázquez, painters like Alonso Sánchez Coello and Juan Pantoja de la Cruz produced portraits of Spain’s elite, emphasizing status and individuality.

- Golden Age Literature:

- Writers such as Miguel de Cervantes, author of Don Quixote, and playwrights like Lope de Vega and Calderón de la Barca, contributed to the era’s cultural richness. These literary works often explored themes of identity, honor, and the human condition, paralleling the depth of the visual arts.

- Portraiture:

The Legacy of the Spanish Golden Age

- The Spanish Golden Age solidified Spain’s reputation as a global cultural powerhouse, producing works that continue to influence art and literature worldwide.

- Masterpieces by El Greco, Velázquez, and Zurbarán reflect the era’s spiritual intensity and technical innovation, while the grandeur of Baroque sculpture and architecture underscores Spain’s political and religious aspirations.

- The art of this period remains a cornerstone of Spain’s cultural identity, celebrated in institutions such as the Prado Museum in Madrid and admired by audiences around the globe.

Chapter 6: 18th-Century Art and the Age of Goya

The 18th century in Spain marked a period of transition in art and culture, influenced by the Enlightenment, the Bourbon monarchy, and political shifts across Europe. This era bridged the grandeur of the Baroque with the emerging Neoclassical style, setting the stage for one of Spain’s most influential artists: Francisco Goya. Goya’s work encapsulates the complexities of this period, reflecting both the ideals of Enlightenment and the darker realities of war and human suffering.

Neoclassicism and the Bourbon Influence

- The Bourbon dynasty, which ascended to the Spanish throne in 1700, brought French cultural and artistic sensibilities to Spain, including a preference for the Neoclassical style.

- Neoclassical Architecture:

- The Royal Palace of Madrid, designed by Italian architect Filippo Juvarra and completed under Francesco Sabatini, exemplifies Neoclassical elegance with its symmetry and grandeur.

- The Prado Museum, conceived during the reign of Charles III, was originally intended as a natural history museum but became one of the world’s most celebrated art institutions. Its Neoclassical design, by architect Juan de Villanueva, reflects the Enlightenment emphasis on rationality and order.

- Sculpture and Decorative Arts:

- Spanish sculptors embraced Neoclassical principles, creating works inspired by Greco-Roman antiquity. Artists like Alfonso Bergaz produced stately busts and reliefs that celebrated reason and civic virtue.

- Neoclassical Architecture:

The Rise of Francisco Goya

- Francisco Goya (1746–1828) emerged as the most significant artist of late 18th- and early 19th-century Spain, bridging the Neoclassical and Romantic movements while forging a style uniquely his own.

Early Career: Court Painter

- Goya began his career as a tapestry designer for the Royal Tapestry Factory, creating vibrant designs that depicted everyday life, such as The Parasol (1777) and The Pottery Vendor (1779). These works reveal his keen observation of human behavior and mastery of composition.

- As a court painter under Charles III and Charles IV, Goya produced elegant portraits of Spain’s elite, including The Family of Charles IV (1800), a strikingly candid portrayal of the monarchy.

The Enlightenment and Social Critique

- Goya’s art reflects his engagement with Enlightenment ideals, as well as his skepticism of the Church and aristocracy.

- In his series of etchings, Los Caprichos (1799), Goya critiques the superstition, corruption, and social inequalities of his time through biting satire and fantastical imagery. The famous print The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters captures the tension between rationality and human folly.

Romanticism and the Darker Realities of War

- The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) and the subsequent Peninsular War (1808–1814) had a profound impact on Goya’s work, marking a shift from Enlightenment optimism to a more somber and introspective perspective.

- The Disasters of War (1810–1820):

- This series of etchings depicts the brutality and suffering of the Peninsular War, offering an unflinching look at the horrors of conflict. Images such as What Courage! and The Third of May 1808 are haunting testaments to the human cost of war.

- The Third of May 1808 (1814):

- One of Goya’s most famous paintings, this work commemorates the massacre of Spanish rebels by Napoleonic troops. Its dramatic use of light, composition, and emotion makes it a powerful symbol of resistance and sacrifice.

- The Disasters of War (1810–1820):

Late Career and the Black Paintings

- In his later years, Goya withdrew from public life, creating some of his most enigmatic and personal works.

- The Black Paintings:

- Painted directly onto the walls of his home, these dark and haunting images, such as Saturn Devouring His Son and The Witches’ Sabbath, reflect Goya’s disillusionment with humanity and his preoccupation with mortality.

- Innovations in Technique:

- Goya’s loose brushwork and use of color anticipated modernist movements, earning him recognition as a precursor to Impressionism and Expressionism.

- The Black Paintings:

Legacy of Goya and 18th-Century Spanish Art

- Francisco Goya’s work remains a cornerstone of Spanish art, bridging traditional and modern approaches while capturing the complexities of his era.

- The Enlightenment ideals of reason and progress, along with the Romantic focus on emotion and individuality, are reflected in the art and architecture of 18th-century Spain.

- Goya’s masterpieces, preserved in institutions like the Prado Museum and the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, continue to resonate with audiences worldwide, cementing his status as one of history’s greatest artists.

Chapter 7: Modernism and the Avant-Garde (Late 19th–Early 20th Century)

The late 19th and early 20th centuries marked a period of radical transformation in Spanish art, as artists embraced modernist and avant-garde movements that reshaped the boundaries of creativity. From Antoni Gaudí’s architectural innovations to Pablo Picasso’s revolutionary Cubism and Salvador Dalí’s surrealist visions, Spain became a global epicenter for artistic experimentation. This era reflected both a deep connection to Spain’s cultural heritage and an openness to international influences, cementing its place at the forefront of modern art.

Catalan Modernism: Gaudí and Beyond

- Catalan Modernism (Modernisme) flourished in Barcelona during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, blending Gothic revival, Art Nouveau, and a deep respect for traditional Catalan craftsmanship.

- Antoni Gaudí (1852–1926):

- Gaudí’s innovative architecture redefined the possibilities of form, structure, and ornamentation. His work often drew inspiration from nature, incorporating organic shapes and vibrant mosaics.

- Key Works:

- Sagrada Família: Begun in 1882, this basilica remains one of Gaudí’s most iconic creations. Its soaring spires and intricate facades are a testament to his genius and spiritual vision.

- Park Güell: A public park featuring whimsical structures, vibrant ceramic mosaics, and panoramic views of Barcelona.

- Casa Batlló and Casa Milà: Residential buildings that exemplify Gaudí’s use of flowing lines, innovative materials, and a unique aesthetic.

- Other Catalan Modernist architects, such as Lluís Domènech i Montaner and Josep Puig i Cadafalch, contributed landmark structures like the Palau de la Música Catalana and Casa Amatller, blending functionality with ornate detail.

- Antoni Gaudí (1852–1926):

The Birth of Cubism: Pablo Picasso

- Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), born in Málaga, revolutionized modern art as one of the founders of Cubism, a movement that deconstructed perspective and form to explore multiple viewpoints simultaneously.

- The Cubist Period:

- Alongside Georges Braque, Picasso developed the Analytic Cubism style, exemplified by works like Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), which challenged traditional notions of beauty and representation.

- In Synthetic Cubism, Picasso incorporated collage techniques, combining painted and real elements, as seen in Still Life with Chair Caning (1912).

- Legacy:

- Picasso’s innovations in Cubism influenced a generation of artists and established Spain as a leader in the global modernist movement.

- The Cubist Period:

Surrealism and Salvador Dalí

- Spain became a key center for Surrealism, a movement that explored the subconscious and dreamlike imagery.

- Salvador Dalí (1904–1989):

- Dalí’s surrealist paintings, such as The Persistence of Memory (1931), with its iconic melting clocks, explore themes of time, identity, and the irrational.

- His eccentric personality and multimedia approach, including film and sculpture, made him one of the most recognizable figures in 20th-century art.

- Other notable Spanish surrealists included Joan Miró, whose abstract works blended vibrant colors and playful forms to evoke both childlike wonder and deep symbolism.

- Salvador Dalí (1904–1989):

The Influence of the Spanish Civil War

- The Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) profoundly impacted Spain’s artists, inspiring works that captured the turmoil and tragedy of the era.

- Picasso’s Guernica (1937):

- Commissioned for the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris, this monumental painting depicts the bombing of the Basque town of Guernica by Nazi forces. Its fragmented forms and anguished figures symbolize the horrors of war and human suffering.

- Luis Buñuel, a surrealist filmmaker, addressed themes of political oppression and societal hypocrisy in films like The Exterminating Angel (1962).

- Picasso’s Guernica (1937):

Architecture and Design in the Avant-Garde

- While Gaudí dominated Catalan Modernism, other architects and designers embraced the avant-garde spirit of the early 20th century.

- Rafael Masó, a contemporary of Gaudí, created structures that blended modernist innovation with traditional Catalan forms.

- Josep Maria Jujol, a collaborator of Gaudí, contributed intricate decorative elements to major projects like the Sagrada Família and Casa Batlló.

Themes and Legacy of Modernism and the Avant-Garde

- Spanish artists of this era pushed the boundaries of artistic expression, blending local traditions with cutting-edge techniques and ideas.

- The works of Gaudí, Picasso, Dalí, and Miró remain defining symbols of modern art, celebrated in institutions like the Museu Picasso in Barcelona, the Dalí Theatre-Museum in Figueres, and the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid.

- This period established Spain as a global leader in innovation and creativity, inspiring generations of artists worldwide.

Chapter 8: Post-Civil War Art and Franco’s Regime (1936–1975)

The aftermath of the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) and the subsequent dictatorship of Francisco Franco (1939–1975) ushered in a challenging period for Spanish art. Censorship, repression, and isolation from the broader European avant-garde characterized much of the era. However, artists found ways to navigate these constraints, producing works that either conformed to the regime’s ideals or subtly resisted them. By the later years of Franco’s rule, an underground art scene emerged, laying the foundation for Spain’s post-dictatorship artistic renaissance.

The Impact of Francoist Policies on Art

- Under Franco, art was used as a tool for propaganda, celebrating traditional Spanish values and glorifying the Catholic Church and the regime.

- State-Sponsored Art:

- Artworks and architecture commissioned by the regime often promoted conservative ideals, reflecting Franco’s vision of a unified, Catholic Spain.

- The Valley of the Fallen, constructed between 1940 and 1959, is a monumental basilica and memorial dedicated to those who died in the Civil War. Designed to project the regime’s power, it remains a controversial symbol of the dictatorship.

- Censorship and Control:

- Avant-garde movements were suppressed, and artists who expressed dissent or deviated from the regime’s approved narratives faced exile, censorship, or persecution.

- State-Sponsored Art:

Exile and Artistic Resistance

- Many prominent artists fled Spain during or after the Civil War, continuing their work abroad and often critiquing the Franco regime.

- Pablo Picasso:

- Picasso, who had already gained international acclaim, spent his later years in exile in France. His masterpiece Guernica (1937) became an enduring symbol of resistance to authoritarianism and war.

- Despite pressure from Franco’s government, Picasso refused to allow Guernica to return to Spain until democracy was restored.

- Joan Miró:

- While remaining in Spain during much of the dictatorship, Miró’s work often contained subtle acts of defiance. His abstract forms and vibrant colors were a stark contrast to the regime’s conservative aesthetic.

- Pablo Picasso:

Abstract Art and the Informalist Movement

- By the 1950s, an underground art scene began to emerge, with Spanish artists experimenting with abstraction and other modernist techniques.

- Informalism:

- This movement, inspired by Abstract Expressionism and Art Informel, emphasized materiality and spontaneity over traditional forms.

- Antoni Tàpies, one of the most influential Informalist painters, used unconventional materials like sand and marble dust in his works, creating textures that conveyed themes of oppression and transcendence.

- Luis Feito and Manuel Millares also contributed to the Informalist movement, using abstraction to explore existential and political themes.

- These artists often exhibited their works in international galleries, gaining recognition despite the regime’s efforts to suppress their voices.

- Informalism:

Surrealism and Film: Buñuel’s Return

- Luis Buñuel, a prominent surrealist filmmaker, returned to Spain in the 1960s after years of exile, creating films that subtly critiqued Francoist society.

- Viridiana (1961):

- Produced in Spain, this film exposed the hypocrisy of the regime’s moral and religious ideals. Despite winning the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, it was banned in Spain for years.

- Viridiana (1961):

The Role of Museums and Collectors

- While Franco’s regime limited artistic freedom, certain museums and private collectors played a crucial role in preserving and showcasing modern art.

- The establishment of the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo in Madrid in 1952 provided a platform for contemporary Spanish artists, though its exhibitions were often heavily monitored and curated by the state.

- Collectors like Margarita Nelken and Josep Suñol supported avant-garde artists, helping to protect and promote their works during the dictatorship.

Late Francoism and the Cultural Thaw

- By the 1960s and 1970s, economic modernization and the loosening of cultural policies allowed for greater artistic experimentation.

- Pop Art and Conceptualism:

- Artists like Eduardo Arroyo and Equipo Crónica used Pop Art techniques to critique consumerism and political propaganda.

- Conceptual artists such as Isidoro Valcárcel Medina explored themes of censorship, freedom, and identity, often using performance and ephemeral materials.

- Photography and Performance:

- Photography became a medium for documenting social realities, with figures like Francesc Català-Roca capturing the contrasts of Francoist Spain.

- Performance art also gained traction as a way to challenge societal norms and push boundaries.

- Pop Art and Conceptualism:

Legacy of the Franco Era in Art

- Despite the repression of the Franco regime, Spanish artists of this period demonstrated remarkable resilience and innovation, finding ways to navigate and challenge the constraints imposed on them.

- The groundwork laid by Informalism, conceptual art, and underground movements during this era helped shape Spain’s post-Franco artistic revival, which flourished after the dictator’s death in 1975.

- Today, the art of this period is preserved and studied in institutions like the Museo Reina Sofía and the Fundació Antoni Tàpies, serving as a testament to the enduring power of creativity in the face of oppression.

Chapter 9: Contemporary Spanish Art (1975–Present)

The death of Francisco Franco in 1975 marked a new era of freedom and creativity for Spanish art. The transition to democracy, known as the Spanish Transition, created an environment where artists could explore themes of identity, politics, and globalization without fear of censorship. Contemporary Spanish art reflects the country’s rich cultural heritage while engaging with international movements and modern technologies, solidifying Spain’s position as a global leader in the arts.

The Movida Madrileña: A Cultural Renaissance

- The Movida Madrileña was a countercultural movement in the late 1970s and 1980s, centered in Madrid, that celebrated freedom of expression, experimentation, and hedonism.

- Art and Multimedia:

- Artists like Ouka Leele, a pioneer in experimental photography, used vibrant colors and surreal compositions to capture the spirit of the era.

- Pedro Almodóvar, though better known as a filmmaker, incorporated art and design into his work, blending kitsch, surrealism, and pop culture influences.

- Street Art and Urban Interventions:

- The movement inspired a wave of street art and public installations, reflecting the energy and rebellion of post-Franco Spain.

- Art and Multimedia:

Globalization and Postmodernism

- By the 1990s, Spanish artists were deeply engaged with global artistic movements, exploring postmodern themes such as identity, memory, and consumerism.

- Sculpture and Installation Art:

- Cristina Iglesias, known for her monumental sculptures and site-specific installations, explores the interplay between space, architecture, and nature.

- Jaume Plensa creates large-scale public sculptures, such as Crown Fountain (2004) in Chicago, blending contemporary materials with universal themes of communication and human connection.

- Conceptual Art:

- Artists like Ignasi Aballí and Dora García use text, objects, and performance to question the boundaries of art and reality.

- Sculpture and Installation Art:

Photography and New Media

- Contemporary Spanish photographers and digital artists have embraced cutting-edge technologies to create works that explore both personal and societal themes.

- Chema Madoz:

- Known for his surreal black-and-white photography, Madoz creates thought-provoking images that challenge perception and meaning.

- Daniel Canogar:

- A leading figure in digital and video art, Canogar’s works often explore the intersection of technology, memory, and obsolescence, such as his interactive installation Pulse (2019).

- Chema Madoz:

The Influence of Regional Identity

- Regional cultures continue to play a significant role in Spanish art, with Catalonia, the Basque Country, and Galicia producing distinct artistic voices.

- Basque Artists:

- Eduardo Chillida, a sculptor celebrated for his abstract forms and monumental works, created pieces like Peine del Viento (1977) that blend with the natural landscape.

- The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, designed by Frank Gehry, has become a symbol of cultural revitalization in the Basque Country, hosting exhibitions by both Spanish and international artists.

- Catalonia:

- Barcelona remains a hub of contemporary art, with institutions like the MACBA (Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona) fostering innovation and collaboration.

- Basque Artists:

Themes in Contemporary Spanish Art

- Memory and Trauma:

- Many artists explore Spain’s complex history, particularly the Civil War and Francoist era, addressing themes of loss, resilience, and reconciliation.

- Alberto García-Alix, a photographer, captures intimate and raw portraits of individuals, reflecting Spain’s cultural transformation.

- Globalization and Environmental Concerns:

- Artists like Jorge Oteiza and Manuel Franquelo engage with themes of consumerism and ecological fragility, creating works that critique modern society.

- Identity and Feminism:

- Female artists such as Esther Ferrer and Marisa González challenge traditional gender roles, using performance and mixed media to explore themes of empowerment and representation.

Museums and Cultural Institutions

- Spain’s vibrant museum culture has played a significant role in promoting contemporary art, with institutions showcasing both Spanish and international works.

- Museo Reina Sofía (Madrid):

- Known for housing Picasso’s Guernica, the Reina Sofía also features a diverse collection of modern and contemporary art, including works by Miró, Dalí, and Tàpies.

- Guggenheim Museum Bilbao:

- A cornerstone of Spain’s contemporary art scene, this architectural marvel has hosted groundbreaking exhibitions by artists like Louise Bourgeois and Jeff Koons.

- Fundació Joan Miró (Barcelona):

- This museum celebrates the legacy of Joan Miró while supporting contemporary artists through exhibitions and residencies.

- Museo Reina Sofía (Madrid):

The Future of Spanish Art

- As Spain continues to embrace globalization and technological innovation, its artists are pushing the boundaries of creativity, engaging with pressing issues such as climate change, migration, and digital transformation.

- The nation’s rich artistic heritage serves as both inspiration and contrast, ensuring that contemporary Spanish art remains rooted in tradition while looking toward the future.

Legacy of Contemporary Spanish Art

- Spanish artists have played a vital role in shaping the global contemporary art scene, balancing their unique cultural identity with universal themes.

- Institutions like the Reina Sofía, MACBA, and Guggenheim Bilbao ensure that Spain remains a vibrant center for artistic exchange and experimentation.

- The works of modern Spanish artists continue to inspire audiences worldwide, reflecting the resilience and creativity of a nation with a deep commitment to the arts.

Chapter 10: Spanish Architecture as a Parallel Tradition

Spanish architecture is as diverse and dynamic as its art, evolving through centuries of cultural exchange and innovation. From ancient Roman structures to the futuristic designs of Santiago Calatrava, Spain’s architectural legacy reflects its unique position at the crossroads of civilizations. This chapter explores Spain’s architectural heritage, highlighting its key periods, styles, and landmarks that have shaped its urban and cultural identity.

Roman Foundations

- Roman architecture in Hispania laid the groundwork for Spain’s urban infrastructure, emphasizing durability, functionality, and grandeur.

- Aqueduct of Segovia:

- Built in the 1st century CE, this iconic aqueduct exemplifies Roman engineering precision, using no mortar yet remaining functional for centuries.

- Roman Theatre of Mérida:

- A masterpiece of Roman design, this theater could hold up to 6,000 spectators and is still used for performances today.

- Itálica:

- Founded in 206 BCE, this Roman city near Seville features a well-preserved amphitheater and intricate mosaics, showcasing the artistic sophistication of Roman Hispania.

- Aqueduct of Segovia:

Islamic and Mudéjar Marvels

- The Islamic conquest of Spain in the 8th century introduced architectural innovations that blended geometric precision with ornate decoration.

- The Alhambra (Granada):

- This Nasrid palace complex (13th–14th century) is a masterpiece of Islamic architecture, with its intricately carved stucco walls, lush courtyards, and reflective water features.

- The Great Mosque of Córdoba:

- Built in the 8th century, this structure’s horseshoe arches, double-tiered columns, and stunning mihrab highlight the sophistication of Umayyad architecture.

- Mudéjar Style:

- Following the Reconquista, the Mudéjar style emerged as a synthesis of Islamic and Christian design elements, seen in structures like the Alcázar of Seville and the Church of San Pablo in Zaragoza.

- The Alhambra (Granada):

Gothic Grandeur

- The Gothic period (13th–15th centuries) brought soaring cathedrals and intricate detailing, reflecting the growing power of the Catholic Church.

- Cathedral of Seville:

- The largest Gothic cathedral in the world, this monumental structure features the Giralda Tower, originally a minaret, and the magnificent altarpiece of the Capilla Mayor.

- Cathedral of Toledo:

- Known as the “Magnum Opus of Gothic Architecture in Spain,” Toledo Cathedral combines French Gothic influences with uniquely Spanish elements.

- Burgos Cathedral:

- This UNESCO World Heritage Site is famed for its elaborate spires, sculptural decoration, and stained glass.

- Cathedral of Seville:

Renaissance and Baroque Splendor

- During the Renaissance and Baroque periods, Spanish architecture reflected the influence of Italian humanism and the Catholic Counter-Reformation.

- El Escorial:

- Built under Philip II, this royal complex combines Renaissance symmetry with austere functionality, serving as a palace, monastery, and library.

- Granada Charterhouse:

- An ornate example of Spanish Baroque, this Carthusian monastery features intricate stucco work and gilded altars.

- Churrigueresque Style:

- Named after the Churriguera family, this highly decorative Spanish Baroque style is exemplified by the Plaza Mayor in Salamanca and the façade of the University of Valladolid.

- El Escorial:

Modernism and Antoni Gaudí

- The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the rise of Catalan Modernism, blending Gothic revival, Art Nouveau, and organic forms.

- Sagrada Família (Barcelona):

- Gaudí’s unfinished basilica is one of the most iconic buildings in the world, combining intricate detail with a profound spiritual vision.

- Casa Batlló and Casa Milà:

- These residential buildings showcase Gaudí’s innovative use of curved lines, mosaics, and imaginative structural designs.

- Park Güell:

- A colorful public park featuring whimsical structures and panoramic views of Barcelona.

- Sagrada Família (Barcelona):

Contemporary Architecture

- Spain’s contemporary architects have continued to innovate, blending tradition with cutting-edge design.

- Guggenheim Museum Bilbao:

- Designed by Frank Gehry and completed in 1997, this titanium-clad museum transformed Bilbao into a cultural hub and exemplified the “Bilbao Effect.”

- Santiago Calatrava:

- Known for his futuristic designs, Calatrava’s works include the City of Arts and Sciences in Valencia and the Turning Torso in Malmö.

- Adaptive Reuse:

- Modern architects have revitalized historic structures, such as the CaixaForum Madrid, a former power station converted into a cultural center.

- Guggenheim Museum Bilbao:

Themes and Legacy

- Spanish architecture reflects the nation’s ability to blend tradition and innovation, creating structures that are both functional and deeply symbolic.

- Landmarks like the Alhambra, Sagrada Família, and Guggenheim Museum Bilbao showcase Spain’s contributions to global architecture, inspiring generations of architects and designers.

- The integration of diverse cultural influences—Roman, Islamic, Gothic, and modern—underscores Spain’s unique position as a bridge between worlds.

Chapter 11: Conclusion—Spain’s Artistic Legacy

Spain’s art history is a testament to its profound cultural diversity, resilience, and innovation. From the prehistoric cave paintings of Altamira to the cutting-edge digital art of the 21st century, Spanish artists and architects have consistently pushed the boundaries of creativity while drawing deeply from their rich heritage. The nation’s ability to synthesize influences from Roman, Islamic, Gothic, Renaissance, and modernist traditions has produced an artistic legacy that is both uniquely Spanish and universally admired.

During the Spanish Golden Age, Spain solidified its place as a global cultural powerhouse, producing masterpieces by figures like El Greco, Velázquez, and Zurbarán that continue to captivate audiences. The revolutionary contributions of Goya, Picasso, Dalí, and Miró defined modern art and transformed Spain into a leader of global artistic movements. The architecture of Antoni Gaudí and the surrealist films of Luis Buñuel further exemplify Spain’s commitment to innovation and individual expression.

In the contemporary era, Spanish artists have engaged with themes of identity, memory, and globalization, reflecting the country’s dynamic transformation into a modern democracy. Institutions like the Museo Reina Sofía, Guggenheim Bilbao, and MACBA ensure that Spain remains a vibrant hub for artistic exchange, showcasing both historical treasures and cutting-edge works.

As Spain looks to the future, its artists and architects continue to navigate the challenges and opportunities of a rapidly changing world. Whether addressing environmental concerns, exploring the possibilities of new media, or reinterpreting traditional forms, they honor the enduring spirit of Spanish art: a spirit rooted in passion, exploration, and the profound belief in the power of creativity to inspire and transform.