Rosa Bonheur was born on March 16, 1822, in Bordeaux, France, during a time when few women had the freedom to pursue careers in the fine arts. She came from a creative and politically minded family. Her father, Oscar-Raymond Bonheur, was a landscape and portrait painter, while her mother, Sophie Bonheur, was a piano teacher. Both parents deeply influenced Rosa’s early development, especially through their unconventional views on society and education.

Oscar-Raymond was a supporter of Saint-Simonianism, a utopian socialist movement in France that emphasized equality between the sexes, education reform, and communal life. He passed these beliefs on to Rosa, encouraging her interest in art and reinforcing the notion that a woman could pursue a life outside traditional roles. Rosa’s mother died in 1833, when Rosa was just 11 years old, a loss that left a deep emotional mark. Despite this hardship, Rosa continued to grow artistically under her father’s guidance.

Although Rosa struggled in school—she was expelled from several institutions—she found solace and purpose in drawing and studying the natural world. From a young age, she was more fascinated by animals and nature than books or academic studies. This curiosity laid the foundation for her future as one of the most skilled animal painters of the 19th century. While other girls her age played with dolls, Rosa was often outside observing horses, cattle, and goats.

A Childhood Shaped by Art and Ideals

When the family relocated to Paris in the early 1830s, Rosa’s exposure to the artistic world intensified. Her father opened a modest studio and took her on as a pupil, training her in drawing and oil painting. With no access to formal academic instruction—then closed to women—Rosa learned by copying prints, painting still lifes, and practicing under her father’s watchful eye. These foundational years developed both her technical skill and her unwavering confidence in her own abilities.

The Path to Becoming an Artist

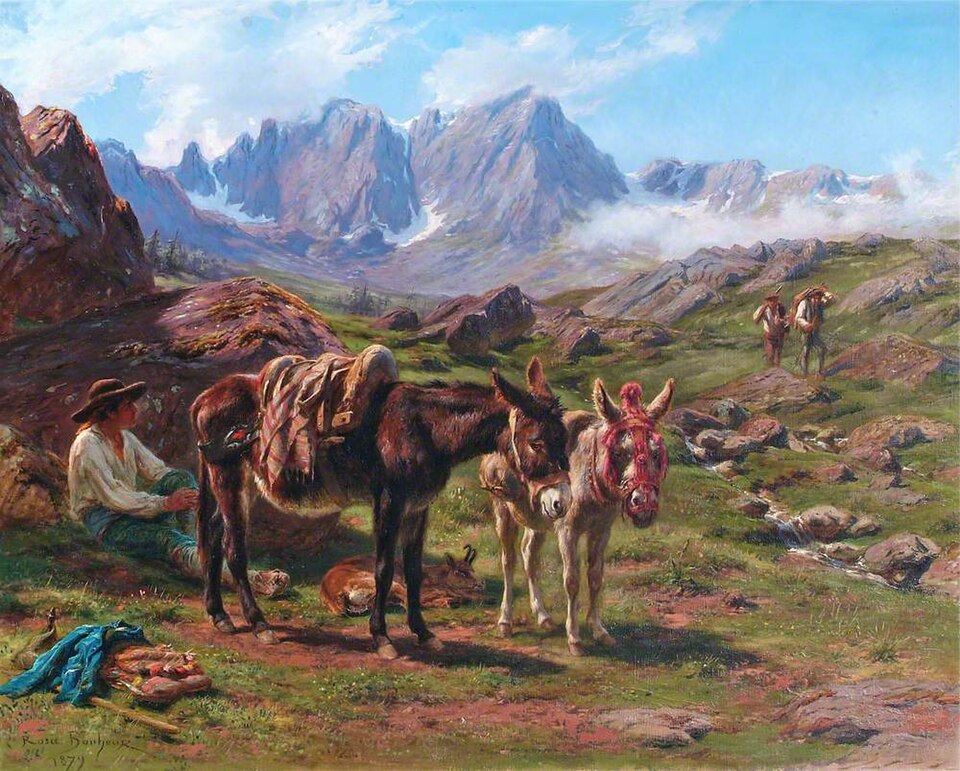

Denied access to the École des Beaux-Arts due to her gender, Rosa forged her own path. Her training came not from professors but from the streets, fields, and livestock markets of Paris. She studied the musculature of animals in extraordinary detail, often visiting slaughterhouses and abattoirs to dissect carcasses and sketch anatomy with scientific precision. Her dedication and boldness were almost unheard of for a young woman in 1830s France.

She often sketched for hours in the Jardin des Plantes or along the banks of the Seine, observing how animals moved and interacted with their environment. Her fascination with realism and the natural world became the hallmark of her artistic identity. Unlike many of her male peers who focused on mythological or historical subjects, Rosa honed her attention on the honest, unsentimental portrayal of animals. This would later distinguish her work from many others of the period.

Training Outside the Academy

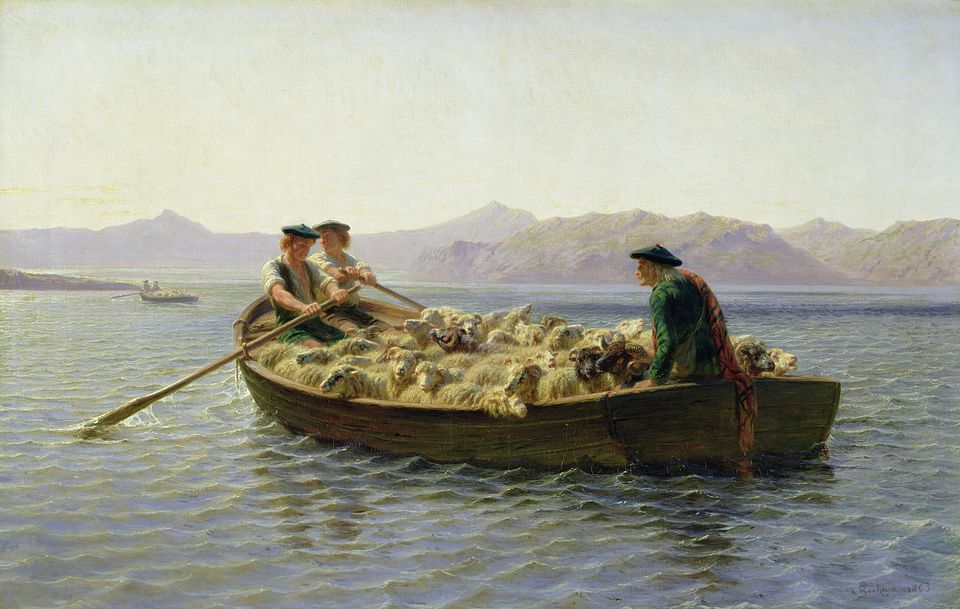

In 1841, at the age of 19, Bonheur submitted her first work to the prestigious Paris Salon. The piece, Goats and Sheep, was accepted—an enormous accomplishment for an untrained, female artist. Her paintings continued to appear in the Salon throughout the 1840s, gradually gaining the attention of patrons and critics. In 1848, she won a gold medal for her painting Oxen Plowing in the Nivernais, commissioned by the French government.

That same year marked the beginning of widespread recognition for her distinctive style. Her precise draftsmanship, mastery of texture, and eye for detail earned her admiration across France. Though she was still considered eccentric by many, her skill was undeniable. Rosa was becoming not just a novelty as a female artist, but a respected figure in the broader art community.

Breakthrough Success and International Fame

Rosa Bonheur’s rise to international fame came with the unveiling of The Horse Fair, painted between 1852 and 1855. The massive work, measuring over 16 feet in length, captured the energy and muscularity of a live Parisian horse market. The painting showcased Percheron horses being led in a dynamic circular pattern, with dust flying and hooves pounding. Bonheur’s anatomical accuracy and dramatic composition left audiences stunned.

The work was displayed at the Paris Salon in 1853 to great acclaim. It later toured Britain and the United States, where it drew large crowds and glowing reviews. British art dealer Ernest Gambart purchased the piece and helped introduce Bonheur to an international audience. In 1857, The Horse Fair was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where it remains today. This established her as one of the foremost animal painters in the world.

“The Horse Fair” and Global Recognition

While visiting England, Bonheur met Queen Victoria in 1855. The Queen, an admirer of her work, received her at Windsor Castle—a rare honor for a female artist. This royal meeting cemented Bonheur’s reputation among the European elite. She was also awarded the prestigious Cross of the Legion of Honour in 1865 by Empress Eugénie, becoming the first woman to receive the medal for artistic achievement.

By the 1860s, Bonheur had reached the height of her career, earning considerable income from her sales and commissions. She purchased the Château de By in 1860, a large estate near the forest of Fontainebleau. The estate became her studio, residence, and sanctuary. It was also a place where she could raise animals and immerse herself fully in the rural life that so deeply inspired her work.

Personal Life and Lifelong Partnerships

Rosa Bonheur never married and lived a highly unconventional life by the standards of her time. Her closest companion for over 40 years was Nathalie Micas, an inventor and fellow artist. The two women lived together at the Château de By, maintaining a partnership that was both emotional and professional. Micas helped Bonheur manage her business affairs and provided technical support in her artistic endeavors.

While contemporary accounts avoid modern labels, many scholars agree that their relationship was deeply intimate and enduring. They shared domestic life, artistic projects, and travel experiences until Micas’ death in 1889. Their home was filled with both art and animals, including dogs, deer, and even a lion cub. It was a world that Bonheur had crafted entirely on her own terms.

Nathalie Micas and Anna Klumpke

After Micas’ passing, Bonheur formed a close connection with American portrait painter Anna Klumpke. The two met in 1898 when Klumpke came to paint Bonheur’s portrait. The relationship quickly deepened into a companionship that lasted until Bonheur’s death the following year. Klumpke later wrote Bonheur’s authorized biography and was entrusted with her artistic legacy.

Rosa Bonheur died on May 25, 1899, at the age of 77. Honoring her final wishes, she was buried alongside Nathalie Micas at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. Her home and studio were left to Klumpke, who preserved much of Bonheur’s work and belongings. Together, these women shaped and sustained a life and career that defied societal norms.

Defying Gender Norms and Gaining Autonomy

Throughout her life, Rosa Bonheur defied conventional expectations for women. One of the most discussed aspects of her personal style was her preference for wearing men’s clothing. This was not a political statement, but rather a practical one. She found that trousers and work boots allowed her to move more freely when sketching in the field or visiting slaughterhouses.

Because French law in the 19th century restricted cross-dressing without official permission, Bonheur secured a police permit in 1852 to wear men’s clothing. She renewed it periodically for the rest of her life. Her clothing choices shocked some and amused others, but for Bonheur, they were merely a matter of function. She once said, “I am a painter. I have earned the right to live freely.”

Cross-Dressing Permits and Social Critique

While many critics tried to frame her as radical or rebellious, Bonheur maintained that she simply wanted the freedom to work. Her lifestyle reflected her values: independence, discipline, and devotion to her art. She declined marriage offers and avoided salons and social events that didn’t serve her professional goals. In many ways, her quiet defiance was more effective than any manifesto.

Her disregard for feminine conventions was not just personal—it also influenced how she painted. Bonheur portrayed animals and rural life with a realism and seriousness that male critics often reserved for historical or religious subjects. Her work pushed boundaries not by loud declarations, but through excellence and integrity. That was her way of carving space in a male-dominated world.

Later Years and Lasting Influence

Rosa Bonheur remained active in her art well into her 70s. Despite the rise of Impressionism and changing artistic tastes, she held firm to her realistic style. She continued to paint animals, rural scenes, and landscapes from her estate at Château de By. Her studio, filled with taxidermied specimens and live animals, resembled a naturalist’s laboratory more than a conventional atelier.

Her friendship with Anna Klumpke brought renewed energy and emotional comfort during her final years. Klumpke helped her document her artistic philosophy and daily life. In her last works, Bonheur focused on lions and exotic animals, which she studied from life and taxidermy. Even in her advanced age, she pursued accuracy and authenticity with unrelenting commitment.

Honors, Final Works, and Legacy Building

Bonheur passed away peacefully at Château de By on May 25, 1899. Her funeral drew significant attention, and she was celebrated as a national treasure in France. She left behind hundreds of works, including paintings, sketches, and personal journals. Klumpke spent the following years cataloging and preserving Bonheur’s art and reputation.

The studio at Château de By was eventually transformed into a museum. Though the 20th century saw her reputation decline in favor of avant-garde movements, the 21st century brought renewed interest in her work. Bonheur’s paintings are now seen not only as technical achievements but as part of a larger legacy of female autonomy and creative mastery.

Legacy in the Modern Art World

Although Rosa Bonheur was widely celebrated in her lifetime, her reputation faded in the early 20th century as academic realism gave way to modernism. Critics of the time dismissed her work as outdated, overly sentimental, or too traditional. As a result, her contributions were overlooked in art history texts for decades. However, recent scholarship has reignited interest in her skill, life story, and trailblazing career.

Major exhibitions in France during the 2022 bicentenary of her birth helped bring her back into public consciousness. These shows featured her best-known works, including The Horse Fair, Ploughing in the Nivernais, and lesser-known paintings that demonstrate her wide range. Visitors were often struck by her draftsmanship, attention to animal movement, and her bold personality. Her life story now inspires not only artists but historians and cultural scholars.

Reclaiming Rosa Bonheur Today

Today, Rosa Bonheur is recognized as one of the most important women artists of the 19th century. She helped pave the way for future generations of female painters and stood as an example of how talent and perseverance can overcome societal limits. Her refusal to compromise on her vision or her lifestyle made her a quietly revolutionary figure. Many now consider her a role model for artistic and personal integrity.

Bonheur’s influence extends beyond her paintings. Museums, galleries, and feminist scholars have embraced her as a complex and courageous figure. Her story is no longer just about art—it’s about resilience, excellence, and standing firm in one’s calling. Whether studying her brushstrokes or her biography, one thing is clear: Rosa Bonheur lived boldly and painted with purpose.

Key Takeaways

- Rosa Bonheur was born in 1822 and became one of France’s most acclaimed animal painters.

- She was trained by her father and gained fame for works like The Horse Fair.

- Bonheur lived with Nathalie Micas for 40 years and later with Anna Klumpke.

- She wore men’s clothing legally to pursue her art without restriction.

- Her work is being rediscovered and celebrated in the 21st century.

FAQs

- Where was Rosa Bonheur born?

Rosa Bonheur was born in Bordeaux, France, on March 16, 1822. - What is Rosa Bonheur’s most famous painting?

Her most famous work is The Horse Fair, completed between 1852 and 1855. - Did Rosa Bonheur marry?

No, she never married and lived with long-term companions Nathalie Micas and later Anna Klumpke. - How did Rosa Bonheur train as an artist?

She trained under her father and studied animals in markets, slaughterhouses, and zoos. - When did Rosa Bonheur die?

She died on May 25, 1899, at the age of 77.