Gunnar Fredrik Berndtson (1854–1895) was one of the most technically gifted painters to emerge from Finland in the 19th century, yet his name is often missing from popular surveys of Nordic art. Born into an educated Swedish-speaking family in Helsinki, Berndtson chose a different path from his nationalist contemporaries, aligning himself with the classical realism of the French academic tradition. His polished style, refined draftsmanship, and unyielding attention to detail reflect his training under Jean-Léon Gérôme at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. While others chased romantic myths or rustic symbolism, Berndtson painted what he saw—with clarity, quiet emotion, and disciplined technique.

His artistic career took him from the drawing rooms of Helsinki to the art salons of Paris and the deserts of Egypt. He participated in archaeological expeditions, taught future generations of Finnish artists, and executed portraits for the country’s elite. Although he never achieved the fame of painters like Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Berndtson’s academic work stands apart for its technical mastery and cosmopolitan elegance. He neither rejected tradition nor succumbed to the pressures of modernism; instead, he remained true to the principles of realism throughout his life.

Berndtson’s paintings were praised during his lifetime, particularly in academic circles and aristocratic salons, but his career was cut short when he died of illness in 1895 at the age of just 41. Despite his early death, he left behind a compelling body of work—portraits, interiors, and orientalist studies—that continues to gain scholarly attention. His contributions, long overshadowed by nationalist narratives in Finnish art history, are now being reevaluated by critics and institutions alike.

Today, his paintings can be found in museums such as the Ateneum in Helsinki, and his reputation has grown through exhibitions and digital archives. With greater access to his works and writings, Berndtson is emerging not just as a skilled technician, but as a singular voice in 19th-century Nordic realism. His art offers a glimpse into a quieter, more measured approach to beauty—one that values discipline over drama, and clarity over noise.

Early Life and Family Background

Gunnar Berndtson was born on October 24, 1854, in Helsinki, the capital of the Grand Duchy of Finland, then under Russian rule. He came from a Swedish-speaking Finnish family of high standing, part of the cultural and intellectual elite of the city. His father, Carl Harald Berndtson (1817–1877), was a noted journalist, writer, and critic who contributed significantly to Finnish literary and cultural life. Growing up in such a household gave Gunnar early access to books, art, and music, setting the foundation for his lifelong commitment to aesthetics and learning.

As a child, Berndtson showed signs of careful observation and a deep interest in the visual world. Although there are few surviving details about his early artistic activities, records indicate that he was surrounded by cultured family members who supported his interest in painting. His education began at a Swedish-language school in Helsinki, followed by studies at the University of Helsinki, where he initially pursued engineering. However, his passion for art proved stronger, and by the mid-1870s, he had redirected his focus entirely toward becoming a professional painter.

Formative influences: family, schooling, and the Finnish cultural elite

Berndtson’s shift from engineering to art was not an easy decision, especially in a society that valued practical professions. However, his family’s connections in Helsinki’s intellectual circles gave him access to key figures in the Finnish art world, including teachers at the Finnish Art Society’s Drawing School. Founded in 1848, the school was Finland’s primary institution for academic art training at the time. Berndtson enrolled in 1876 and studied under teachers influenced by European academic ideals, where his precise draftsmanship quickly set him apart.

Despite his artistic ambitions, Berndtson was never the bohemian type. He was reserved, methodical, and highly focused, qualities that would define both his character and his art. He avoided the emotional dramatics that often accompanied Romantic nationalism, preferring instead to hone his skill in drawing, anatomy, and composition. This quiet dedication was not always understood by his peers, but it helped him develop a solid technical base that would carry him into international art circles. His early years in Finland were formative not only for his skillset but for shaping the disciplined mindset that would guide him for the rest of his life.

Paris and the Academic Influence

In 1878, Berndtson left Helsinki for Paris, determined to refine his skills in what was then the center of the Western art world. He enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts and was accepted into the atelier of Jean-Léon Gérôme, a leading figure in academic realism. Gérôme’s teaching emphasized technical control, anatomical precision, and historical subject matter, and his influence would remain with Berndtson for the rest of his life. At the École, Berndtson was immersed in a rigorous, structured curriculum that included life drawing, perspective, and classical sculpture studies.

He quickly distinguished himself in Gérôme’s studio, not by bold experimentation, but through precision and restraint. He studied with peers from across Europe, exposing him to a wide range of cultural and stylistic influences while reinforcing his preference for the discipline of academic painting. His palette during this period remained cool and composed, favoring tonal harmony over dramatic contrast. Though he admired the fluidity of Romanticism and the freshness of Impressionism, Berndtson never adopted their approaches; he stayed firmly rooted in academic ideals.

Parisian success and participation in the Salon

Berndtson began exhibiting at the Paris Salon in the early 1880s, with documented entries in 1882 and 1883. His works were praised for their elegant composition and high finish, qualities that appealed to jurors and collectors alike. The Salon was the most prestigious art exhibition in Europe at the time, and acceptance was a mark of professional success. Unlike many Scandinavian artists who felt overshadowed in the French capital, Berndtson flourished there, finding both inspiration and validation among the city’s rigorous standards.

He also formed relationships with other academic painters such as Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier and William-Adolphe Bouguereau, both known for their technical brilliance. While Berndtson admired these figures, he did not become their imitator. Instead, he developed a subtle, introspective variation of realism that emphasized human presence and atmosphere over theatricality. In many ways, Paris gave Berndtson the tools and vocabulary he needed—but he remained a uniquely Nordic voice in a sea of cosmopolitan influence.

Travel and Orientalist Themes

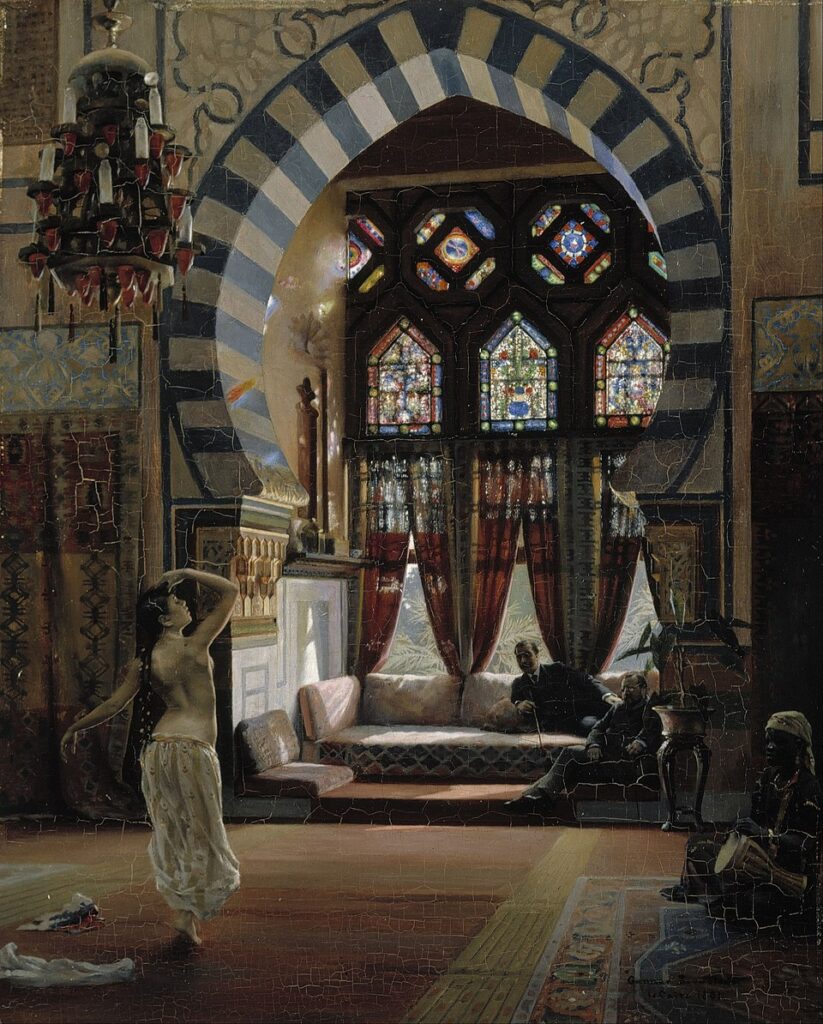

In 1882, Berndtson joined an archaeological expedition to Egypt led by the French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero, spending nearly a year documenting digs, artifacts, and the surrounding landscapes. This experience opened a new chapter in his work, introducing themes and colors drawn from North African life. Unlike the fantastical or eroticized portrayals common among some European Orientalist painters, Berndtson’s works from this period are marked by restraint and observation. His scenes are carefully composed and richly detailed, focusing on daily life rather than exotic spectacle.

The Egyptian paintings reveal a warmer palette, with ochres, browns, and sun-bleached whites replacing the cooler tones of his earlier interiors. He painted scenes of market vendors, seated figures, and desert architecture with the same clarity he applied to his portraits. These works demonstrate his ability to adapt academic technique to new subject matter without losing precision. Though never prolific in this genre, his Egyptian studies added a valuable dimension to his oeuvre.

A realist among Orientalists

Unlike some contemporaries who indulged in Orientalist fantasy, Berndtson approached his subjects with care and accuracy. His time in Egypt was not simply a tourist adventure—it was a working expedition, and his sketches were both artistic and documentary in nature. He respected the local culture and refrained from depicting caricatures or stereotypes. His focus remained on texture, composition, and light, using the environment to showcase the forms of everyday people in natural poses.

Upon returning to Paris, Berndtson exhibited some of his Egyptian scenes, receiving favorable notice for their calm beauty and lack of sensationalism. While he did not continue to produce many Orientalist works, the experience had a lasting effect on his sense of color and spatial design. The sun-drenched clarity and architectural motifs of Egypt subtly influenced his later works, including portraits and interiors. This phase of his career underscores his commitment to realism, even when engaging with foreign and unfamiliar themes.

Return to Finland and Artistic Career

After several years of studying and exhibiting in Paris, Berndtson returned to Finland in the mid-1880s, bringing with him the polished style and academic discipline he had mastered abroad. His return marked a transition into a more settled period, both personally and professionally. He became a sought-after portraitist among the Finnish elite, commissioned by members of the nobility, clergy, and cultural figures. Unlike some of his contemporaries who embraced nationalism in their themes, Berndtson continued to focus on realism, with his subjects depicted in refined, often luxurious surroundings that reflected their social standing.

Finland in the 1880s was undergoing cultural and political changes, with growing nationalist sentiment influencing the arts. Painters like Akseli Gallen-Kallela and Albert Edelfelt turned toward folkloric or historical motifs to express Finnish identity. Berndtson’s work, by contrast, remained cosmopolitan and apolitical, drawing admiration for its precision rather than patriotic fervor. His portraits displayed a quiet dignity, with carefully rendered fabrics, textures, and poses that reflected both the sitter’s character and the artist’s skill. While his work was appreciated by the upper class, it was sometimes criticized for lacking the “Finnishness” championed by the era’s nationalist movement.

Teaching and influence on younger artists

In 1883, Berndtson began teaching at the Drawing School of the Finnish Art Society, where he mentored several younger artists who would go on to have significant careers. His focus on technical drawing, proportion, and observational study made him a popular and respected teacher. Unlike many instructors of his time, Berndtson avoided harsh criticism and encouraged self-discipline and quiet focus in the studio. His influence extended to students who admired his Parisian training and international outlook, including artists who would later travel to France themselves.

Teaching also allowed Berndtson to contribute to the development of a more professionalized art community in Helsinki. He participated in exhibitions, served on juries, and helped raise the standards of Finnish art education. Although he never ran his own school, his private instruction and critiques were widely sought. This role as a mentor and educator enhanced his standing in the Finnish art world, even if he never fully embraced the nationalist artistic direction that came to dominate in the 1890s. His contribution was foundational: a bridge between Finland’s emerging identity and the traditions of academic Europe.

Style, Technique, and Major Works

Berndtson’s painting style is best described as meticulous academic realism, marked by technical refinement, compositional balance, and a quiet emotional tone. His brushwork is smooth and controlled, often invisible to the naked eye, creating surfaces that appear polished and almost photographic. He paid particular attention to fabrics, skin tones, and interior lighting—rendering textures with a level of detail that rewards prolonged viewing. Rather than grand narratives or dramatic poses, his paintings often depict a moment of introspection, a glance, or the play of sunlight across a velvet curtain.

His most notable works include Portrait of a Lady (1880s), a soft yet commanding depiction of a woman seated in an armchair, dressed in a fine gown with lace detail. The painting, now housed at the Ateneum Art Museum in Helsinki, shows Berndtson’s mastery of fabric, posture, and personality. Another important piece is Orientalist Scene (c. 1883), based on his travels in Egypt, which features two seated men in traditional robes amid architectural ruins. The piece blends his academic training with a subtle evocation of place and culture. He also painted interior studies such as Young Woman Reading, notable for its gentle lighting and domestic calm.

Comparing Berndtson to his contemporaries

In comparison to contemporaries like Albert Edelfelt or Helene Schjerfbeck, Berndtson’s work stands out for its fidelity to academic tradition. Where Edelfelt embraced looser brushwork and national themes, and Schjerfbeck evolved into modernist minimalism, Berndtson stayed rooted in 19th-century realism. His allegiance to the French academy made him something of a rarity in Finland, especially as other artists experimented with symbolism and impressionism. He did not innovate in form, but instead elevated execution to its highest possible standard.

Though some critics accused his work of being cold or impersonal, this was often a misunderstanding of his intent. Berndtson was not interested in spectacle; he was interested in truth. His portraits are quiet but intimate, showing individuals as they are, rather than idealized or dramatized. His attention to detail was not superficial but deeply respectful. In a time when many artists used their canvases to make political or nationalistic statements, Berndtson used his to honor beauty, refinement, and the skill of the human hand.

Critical Reception and Legacy

During his lifetime, Berndtson was respected among academic and aristocratic circles but was never embraced by the wider nationalist art movement in Finland. His quiet, reserved nature and traditionalist technique set him apart from the more ideologically driven artists of his generation. Nonetheless, his works were regularly exhibited, and his portrait commissions placed him in the homes of some of Finland’s most prominent families. He was known for arriving on time, working with focus, and delivering portraits that pleased his patrons with both likeness and elegance.

In France, his work received modest attention, particularly through his appearances at the Salon. While he never achieved widespread fame there, his inclusion in such exhibitions validated his technical ability. However, as the art world began to shift toward modernism in the 1890s, artists like Berndtson were increasingly seen as old-fashioned. The posthumous reception of his work suffered during the 20th century, when abstraction, symbolism, and nationalism became dominant themes in Nordic art history. Berndtson’s realism was viewed as conservative—sometimes even irrelevant.

Modern reassessment and museum collections

Only in recent decades has Berndtson’s contribution begun to receive the recognition it deserves. Art historians and curators have reevaluated his work in light of its craftsmanship, cross-cultural engagement, and pedagogical importance. His paintings have been featured in retrospective exhibitions in Finland, and digital archives have made his work more accessible to scholars around the world. In particular, the Ateneum Art Museum in Helsinki holds several of his major works and has helped promote his legacy through curated exhibitions and scholarly research.

Today, Berndtson is appreciated not as a radical or a reformer, but as a master of his craft. His place in Finnish art history is becoming more secure as critics recognize that not all contributions must be revolutionary to be valuable. His dedication to realism, in an age increasingly drawn to symbolism and ideology, now stands out as a statement in itself. In staying true to what he believed, Berndtson left behind a body of work that continues to captivate viewers through quiet elegance and technical excellence.

Personal Life and Untimely Death

Despite his public role as an artist and teacher, Berndtson was known to be intensely private. He never married, and no significant romantic relationships are recorded in his surviving correspondence or biographies. Friends and students described him as calm, serious, and introspective—a man who preferred the studio to the salon. While he was well-liked and respected in academic circles, he avoided social intrigue and artistic cliques, maintaining a small circle of close associates and family ties.

His health began to deteriorate in the early 1890s, possibly due to respiratory illness, though records are vague. In 1895, his condition worsened significantly, and he died later that year on April 9, 1895, in Helsinki. He was just 41 years old. His early death shocked the Finnish art community and cut short a career that was still gaining momentum. At the time of his passing, he was still teaching and accepting commissions, with several unfinished works left in his studio.

Burial and the quiet end of a quiet life

Berndtson was buried at the Hietaniemi Cemetery in Helsinki, a resting place for many of Finland’s most prominent artists, writers, and statesmen. His grave, marked by a modest stone, reflects the simplicity and humility that defined much of his life. There were no grand memorials or posthumous honors; his passing was marked with quiet respect. Over the decades, interest in his life waned as Finland’s art scene shifted toward more modern and ideological expressions.

Yet even in death, Berndtson’s reputation endured among those who valued craftsmanship and classical values. His lack of personal drama, often a liability in the art world, became a kind of strength. He lived a life of purpose, discipline, and refinement, avoiding the chaos that consumed many artists of his generation. Though not a celebrity in his time, his commitment to beauty and precision ensured that his work would outlive the noisy movements of fashion and politics.

Rediscovering Berndtson Today

In the 21st century, Berndtson’s work is undergoing a thoughtful revival, driven by curators, scholars, and digital historians seeking to expand the canon of Finnish art beyond nationalist themes. His portraits, once dismissed as aristocratic relics, are now viewed with appreciation for their technical mastery and psychological insight. Recent exhibitions at the Ateneum and online platforms have brought his work to new audiences, including international viewers unfamiliar with the Nordic realist tradition. This rediscovery has reestablished his role as a key figure in the Finnish academic movement.

One major reason for his renewed appeal is the timelessness of his style. In an age of visual noise and fragmented attention, Berndtson’s controlled compositions and serene subjects feel refreshing. Art students, in particular, are revisiting his work as a model of draftsmanship, tonal control, and compositional balance. His legacy is also being reevaluated through a broader understanding of 19th-century Orientalism, where his respectful portrayals of Egypt now stand apart from more sensational examples. His work offers a bridge between cultures, epochs, and artistic ideals.

Digital archives and institutional support

Institutions like the Finnish National Gallery and RKD Netherlands have made high-resolution images and biographical records of Berndtson’s work available online. These resources have allowed a new generation of researchers to engage deeply with his paintings and understand their historical context. His art has been featured in museum blogs, educational materials, and even virtual reality exhibitions. These tools are helping to integrate Berndtson into broader discussions about European realism, academic training, and Nordic art.

Today, Berndtson is recognized not only as a skilled technician, but as an artist of integrity and vision. He avoided trends, pursued excellence, and left behind a legacy built on discipline and devotion to beauty. In a world that often rewards noise and novelty, his work reminds us that quiet mastery still matters. His rediscovery is not a correction of history, but a long-overdue appreciation for an artist who spoke softly but painted boldly.

Key Takeaways

- Gunnar Berndtson was a Finnish academic realist painter born in 1854 in Helsinki.

- He studied in Paris under Jean-Léon Gérôme and exhibited at the Paris Salon in the 1880s.

- His works include refined portraits and Egyptian-themed paintings based on a 1882–83 expedition.

- Berndtson taught at the Finnish Art Society’s Drawing School and influenced younger artists.

- Though he died in 1895 at age 41, his work is now being reevaluated and appreciated anew.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What style did Gunnar Berndtson paint in?

He painted in the academic realist style, emphasizing technical skill and naturalistic detail. - Why is Berndtson less well known than other Finnish painters?

His work didn’t align with the nationalist themes popular in Finland during his lifetime. - Did Gunnar Berndtson travel outside Finland?

Yes, he studied in Paris and joined an archaeological expedition to Egypt in 1882–83. - Where can I see his work today?

His paintings are in the Ateneum Art Museum and other collections in Finland and Europe. - Was he part of any major art movements?

No, Berndtson remained independent, loyal to the academic realist tradition throughout his life.