The air in 1898 trembled with something unresolved. Artists, critics, and the public alike sensed that they stood in the charged pause before a break—though they could not yet name what exactly might be breaking. The long nineteenth century, with its academic certainties and imperial ambitions, was visibly fraying, but the shape of what might follow remained obscure. In the galleries of Paris, the salons of Vienna, and the newspapers of Berlin and London, familiar styles still held sway—but with mounting unease. Even the most celebrated works seemed to carry within them the faint crackle of self-doubt. This was not a revolution yet. It was a year of waiting, where aesthetic tradition no longer felt whole, and the future was something dim and speculative, flickering at the edges of the frame.

The Brussels International Exposition of 1897 had only just closed when the year turned, and its grandiose ambitions continued to provoke discussion well into 1898. Billed as a showcase of technical and cultural triumph, it offered a microcosm of European self-confidence—and, unintentionally, of its growing contradictions. The fair’s pavilions and decorative arts displays were replete with nationalist motifs and symbols of empire. Yet among the decorative exuberance and industrial pride, some critics sensed overreach, a forced celebration of order in a world tilting toward chaos. As reports and catalogues circulated through the first half of 1898, so too did the impression that cultural optimism had become a kind of defensive ritual.

Vienna Shakes Its Institutions

On March 26, 1898, a group of renegade artists in Vienna unveiled the first exhibition of the newly formed Vienna Secession. Led by Gustav Klimt, Josef Hoffmann, and Koloman Moser, the Secessionists staged their debut not simply as an aesthetic venture but as an existential challenge to the conservative grip of the Künstlerhaus, which they accused of stifling innovation and flattening vision. The Secession’s motto—“To every age its art, to every art its freedom”—read like a manifesto for a new century still unformed.

This first show was a carefully calculated provocation. It blended Symbolist painting with Japonisme, sinuous Art Nouveau graphics with polemical architecture. In the catalogue and the design of the exhibition hall itself, every gesture announced the break. But it was not only rebellion. What gave the exhibition its deeper charge was its ambiguity: its works often turned inward, toward dreams, myth, and sensation. The sharp rationalism of 19th-century historicism—rooted in Enlightenment values—was giving way to something more fragile and intuitive.

The public reception of the exhibition revealed a divided audience. Some critics denounced it as decadence or aesthetic obscurity, while others hailed it as salvation. But behind both reactions lay the same awareness: something old was ending, and it was no longer clear what would replace it.

The Political Weather Turns

If the Secession challenged art institutions, events elsewhere shook the wider cultural framework. In January 1898, Émile Zola published his incendiary letter J’accuse…! on the front page of L’Aurore, reigniting the Dreyfus Affair and plunging France into a moral and political crisis. Though not an artistic event per se, the Dreyfus Affair bled into the world of art with astonishing speed. Painters, printmakers, and writers took sides. Caricaturists sharpened their lines. Anti-Semitic tracts and pro-Dreyfus posters filled the kiosks of Paris. Even the Symbolist salons, usually allergic to politics, whispered with tension.

This moment revealed that the bourgeois ideal of aesthetic detachment, so central to late 19th-century art criticism, was untenable. The supposed neutrality of art—its “timeless” truths—was collapsing under the weight of events. Artists could no longer assume their audience came to the canvas in a shared civic or moral frame. A rift had opened, and even the most refined portrait or poetic allegory was not exempt.

The Death of a Monumentalist

In October, the painter Pierre Puvis de Chavannes died in Paris at the age of 73. Puvis had come to embody the spirit of the Third Republic’s public art—his murals graced the Sorbonne, the Panthéon, and countless civic buildings. In their pale classicism and mythic restraint, they offered visions of harmony and civic virtue, meant to stabilize a fractured modernity through shared visual heritage. But even as his admirers mourned him, a younger generation turned away. For artists like Odilon Redon or Gustave Moreau’s students, Puvis’ style represented an art grown too distant from experience, too serene for a time of friction.

His death was not only a personal loss—it marked the twilight of a style. Monumental public painting, once the highest aspiration of a painter’s career, now seemed compromised by politics, overly didactic, and emotionally inert. The funeral itself, solemn and state-endorsed, had the character of a final page turned.

Interior Worlds and Unstable Selves

While the public sphere throbbed with contradiction, a quieter revolution was underway. Artists were increasingly abandoning historical narrative and civic grandeur in favor of mood, dream, and psychological suggestion. Though Sigmund Freud would not publish The Interpretation of Dreams until 1899, his manuscript was already well underway in 1898, shaped by the death of his father and the strange symbolic logic of his own dreams. This subterranean shift—from a shared world to a private one—found echoes in the painting and graphic work of the year.

In galleries across Germany and Belgium, artists like Fernand Khnopff, Max Klinger, and Franz von Stuck explored themes of alienation, erotic confusion, and metaphysical longing. Their works, often dismissed by older critics as decadent or hermetic, reflected the same psychic pressures that Freud was beginning to theorize. The canvas became a site not for confirming the visible world, but for undermining it.

Among the most revealing works of 1898 were those that refused clarity: portraits with obscured eyes, landscapes drenched in unnatural light, figures caught in half-symbolic, half-erotic reverie. These were not the emblems of confidence but symptoms of a cultural mood shifting inward.

A Year Like a Fissure

In the end, 1898 felt less like a chapter and more like a fracture line—thin, sharp, and spreading. Nothing in that year declared itself the new style or the next age. The old institutions still stood. The grand salons opened on schedule. Patrons still wrote their checks. But inside the art, the paint began to shift. The brush hesitated. Symbols thickened. A curtain stirred, and the audience—though still applauding—looked over its shoulder toward a future it could not yet name.

Beneath all this lay a tension too complex to resolve in manifesto or image. Artists were no longer sure if they were offering visions of progress or elegies for meaning. In that uncertainty, 1898 revealed its essence: not as the end of something, nor the clear beginning of another, but as a trembling moment when the world’s surface still held, but the ground beneath had started to move.

Chapter 2: Klimt’s Vienna and the Rise of the Secession

When the Center Cannot Hold

In the spring of 1898, Vienna found itself at the epicenter of a quiet but irreversible upheaval. For decades, the city’s artistic life had been dominated by a single institution: the Künstlerhaus, a grand bastion of academic taste rooted in historicism and empire. Its exhibitions emphasized polish, idealization, and technical fidelity—values that seemed increasingly detached from the velocity of modern life. The rupture came the previous year, when a group of young artists, led by Gustav Klimt, formally seceded from the Künstlerhaus. By 1898, that break had become something solid: a new building, a new exhibition, and a new principle around which the future of Viennese art would pivot.

This new alliance, calling itself the Vienna Secession, declared its purpose with characteristic clarity: “To every age its art, to every art its freedom.” It was not just a rejection of academic control—it was a declaration of autonomy, of art unmoored from patronage and prescription. The group’s members were not bound by style, technique, or ideology. What they shared was dissatisfaction with the old order and a conviction that art must move with the age, not simply preserve its past.

A Temple to the New

What gave the Secession its force in 1898 was not merely its founding, but the construction of its headquarters. Designed by the architect Joseph Maria Olbrich, the Secession Building stood apart from Vienna’s imperial architecture like a strange modern temple. Its white walls, geometric form, and gilded dome made no gestures toward the architectural languages of the Renaissance or Baroque. It was austere, deliberate, and insistently modern.

The building served two purposes: it was a literal space for exhibitions and a symbolic object in itself. It embodied the group’s core ambition—to collapse the artificial boundaries between architecture, design, painting, and applied arts. Art, the Secessionists believed, should surround life. It should be integrated into the experience of space, ritual, and object. In a city long ruled by formal protocol and conservative tastes, this was an act of both aesthetic and civic defiance.

In its inaugural exhibition later that year, the building housed works not only by Viennese artists, but also by progressive figures from Germany, France, and beyond. This cosmopolitanism was a defining feature. Unlike national academies, which often exalted local traditions, the Secession looked outward. It embraced Symbolism, Art Nouveau, and the decorative flatness of Japanese woodblock prints. Its vision was European in scope and modern in method.

Klimt’s Transformation Begins

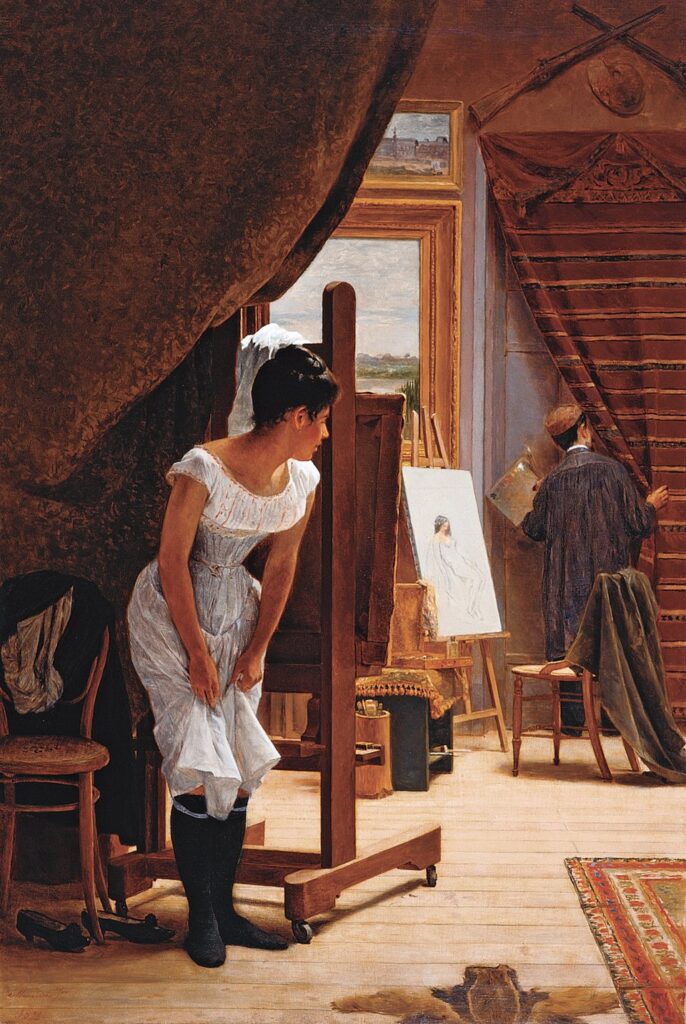

For Gustav Klimt, the year 1898 marked a turning point in both artistic identity and personal ambition. Known throughout the 1880s and early 1890s for his large-scale public commissions—mural cycles in Vienna’s museums and theaters—he had been, in many ways, a favored son of the establishment. But as his style evolved, so did his position. He began to turn away from straightforward allegory and embrace a more mysterious, inward, and ornamental language.

His 1898 painting Pallas Athena offers a kind of artistic manifesto. The classical goddess of wisdom and war is rendered not with academic realism, but with flattened forms, angular contours, and a severe, impenetrable gaze. Gold accents and decorative motifs drift toward abstraction, suggesting Klimt’s growing interest in surface, pattern, and psychological distance. The work is not a mere reinterpretation of myth—it is a rejection of narrative clarity altogether.

More than just a stylistic shift, Pallas Athena reveals a change in how Klimt thought about power, eroticism, and the role of the artist. The goddess, armored yet ornamental, appears both commanding and inaccessible. This ambiguity would become a signature of his mature work: figures suspended between sensuality and stillness, enigma and control.

The Exhibition That Divided Vienna

The 1898 exhibitions—both the initial show in spring and the unveiling of the Secession Building in autumn—divided the Viennese public. Conservative critics decried the movement as decadent, obscure, and dangerously foreign. The building was mocked as a bizarre dome of cabbages. Klimt’s painting was labeled cold, pagan, and even un-Austrian. Yet for a younger generation of artists, designers, and thinkers, the Secession became a beacon.

What shocked many was not just the content of the works but the manner of their display. The exhibitions were curated with meticulous attention to harmony between artworks and environment. Wall colors, lighting, typography, and furniture were considered integral parts of the experience. This approach, largely unprecedented in Vienna, proposed that art was not an isolated object to be venerated from afar—it was something to be lived with, surrounded by, and woven into the fabric of daily life.

In this integration of disciplines, the Secession echoed the ideas then stirring in other European centers: in Glasgow under Charles Rennie Mackintosh, in Munich under the Jugendstil, and in Paris with the architects and designers of the Art Nouveau movement. But the Vienna Secession was never a mere branch of those trends. Its particular tension—between aesthetic freedom and social control, between private symbolism and public display—was deeply Austrian.

Freedom, and Its Fragility

The Secession’s triumph in 1898 was both architectural and conceptual. It created not just a space but a platform for artistic freedom. Yet from the beginning, that freedom was fragile. The group was pluralistic by design—its members included traditional realists, decorative stylists, and emerging Expressionists—but such diversity carried the seeds of conflict. Without a shared doctrine, disputes would inevitably arise over direction, taste, and leadership.

Still, in that year, the vision held. Vienna became, briefly, a city where art stepped out of the shadow of patronage and declared its independence. The Secession was more than an artists’ society—it was a cultural signal, one that told the empire’s capital that something had shifted. The ornamental precision of the past was being reassembled into something unfamiliar: psychologically charged, formally experimental, and no longer beholden to inherited ideals.

The door had opened. What lay beyond it would not always be harmonious, but it would be new.

Chapter 3: The Death of Puvis de Chavannes and the End of a Style

A Painter Passes, and a Silence Follows

On October 24, 1898, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes died in Paris at the age of seventy-three. His death passed quietly in the newspapers but thundered in the salons, studios, and academies that had long looked to him as the ideal of public art. For nearly four decades, Puvis had defined the visual language of moral elevation, national unity, and civic nobility. His murals adorned the walls of the Panthéon, the Sorbonne, the Hôtel de Ville, and museums from Lyon to Boston. In a century that placed art in the service of empire, history, and education, no living painter had done more to shape the official face of France.

But by the time of his death, the style he embodied was already slipping from relevance. Puvis had painted in an idiom both idealized and subdued—flat, tranquil compositions drawn from myth, allegory, and the classical past. His palette was muted, his figures stoic, his spaces vast and calm. He did not moralize so much as reassure. His works promised continuity in an age of conflict, permanence in a time of rapid change. Yet as the century neared its end, that very serenity came to seem evasive. Younger artists no longer believed in the world Puvis had painted.

The Age of the Mural

Puvis rose to prominence during the Second Empire and matured under the Third Republic, a period in which the French state relied on monumental painting to stabilize national identity. After the trauma of the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune, France turned to allegorical mural cycles to reassert civic order. Museums, universities, and town halls commissioned vast programmatic schemes—decorative visions meant to soothe, unify, and elevate. Puvis mastered this language like no other.

In the 1860s, his murals for the Musée de Picardie in Amiens marked him as a new force in public painting. These included scenes such as The River and Work, images that transposed labor and nature into a classical idiom. Later, his commissions for the Sorbonne—especially the emblematic composition The Sacred Grove, Beloved of the Arts and Muses—refined this approach. The figures appeared timeless, not ancient exactly, but unmoored from modern specificity. The compositions avoided strong diagonals or dramatic gesture. Space stretched out quietly, rhythmically. The result was a visual vocabulary of calm authority, as if history itself had slowed its breath.

By the 1880s and 90s, this aesthetic had become the gold standard for public art. It was official without being propagandistic, historical without being particular. Puvis became, in effect, the painter of the Republic’s conscience—reassuring, secular, elevated.

A Style That Held Too Long

Yet even as Puvis’s commissions multiplied, resistance was growing. In private circles and avant-garde reviews, critics began to question the emotional detachment of his work. For younger artists—many of whom had admired Puvis’s early ability to synthesize modern and classical impulses—his late style began to appear ossified. His figures no longer spoke to the tensions of modern life. They floated above history, insulated from anxiety.

This distance became harder to accept as the 1890s wore on. The Dreyfus Affair, the rise of anarchist violence, economic instability, and growing class tensions made allegorical calm seem not noble, but delusional. Artists like Félix Vallotton and Odilon Redon looked instead to ambiguity, irony, or interiority. The moral clarity of allegory gave way to symbolic uncertainty, the human figure unmoored from civic purpose.

Even within the world of public commissions, Puvis’s dominance began to cast a shadow. His compositions had become a template, endlessly emulated by lesser painters. The effect was a proliferation of murals that mimicked his rhythm and palette without achieving his subtlety. In this repetition, the style lost power. It began to feel institutional in the worst sense—predictable, decorative, empty of risk.

The Final Years and Posthumous Reverberation

By the time of his death in 1898, Puvis was still revered. He had served as president of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, where his influence shaped the jury and exhibition culture of official French art. He remained admired across Europe—his works collected, copied, and studied in Germany, Britain, and the United States. Yet his passing also marked a release. Within months, younger artists and critics began to speak more openly of the need to move on.

In Symbolist circles, there was a curious ambivalence. Puvis had been a point of reference for many of them—his simplified forms and poetic stillness had inspired painters like Khnopff, Denis, and Hodler. But the younger Symbolists pursued dreams far darker, more unstable. They sought not civic harmony, but metaphysical rupture. Puvis’s calm became, in their eyes, a refusal to confront the disintegration of meaning.

One of the ironies of his legacy was that he had helped open the door he could not walk through. His flattening of space, reduction of gesture, and emphasis on mood rather than narrative foreshadowed some of the formal innovations of early modernism. But he stopped short of abstraction, and his allegiance to allegory held him in the orbit of tradition.

The End of Allegory?

By 1898, allegory itself was in retreat. Once the visual grammar of public architecture, it now felt increasingly hollow. In an age of scientific uncertainty, psychological complexity, and political fragmentation, the old symbolic personifications—Liberty, Justice, Labor, Truth—no longer held. They looked like actors on an empty stage, mouthing lines the audience no longer believed.

The public monument, too, was entering a crisis. Sculpture had already begun to strain against allegorical clarity, with Rodin’s unfinished monuments and Medardo Rosso’s blurred forms suggesting new directions. In painting, the mood was shifting toward the personal, the idiosyncratic, and the unresolved. Artists no longer saw themselves as illustrators of moral ideas. They had become investigators of perception, experience, and doubt.

Puvis’s death, then, was not merely the loss of a figure—it was the closing of a possibility. The idea that art could bind a society through shared symbols and public walls was becoming untenable. The 20th century would bring muralists again—Orozco, Rivera, Léger—but theirs would be murals of rupture, not harmony.

A Gentle Epilogue

In retrospect, it is possible to view Puvis de Chavannes not as a conservative, but as the last successful utopian. His art did not mock or lie; it hoped. He believed that a shared visual language, derived from the classical past, could still offer meaning to the modern world. That belief was not cowardice—it was conviction. But by 1898, it had become a lonely one.

He left no school, no direct heirs. His impact, once so central, dissolved into the background of institutions, commissions, and quiet echoes in technique. What he offered was a style for an era that no longer existed by the time he departed.

And so, as 1898 closed, a chapter in the history of public art closed with it. The walls were still covered, the allegories still in place, but the faith behind them had dimmed. The silence after Puvis’s death was not mourning. It was recognition. A style had ended.

Chapter 4: Félix Vallotton and the Nabis’ Print Revolution

A Knife Drawn in Silence

In late 1898, a series of stark, enigmatic woodcuts began to circulate in the Parisian journal La Revue Blanche. Rendered in flat black and white, with sharp silhouettes and no tonal gradation, these images depicted quiet, claustrophobic interiors—bedrooms, parlors, salons—each one suffused with tension. A man looms over a woman in a hallway; a couple quarrels beside a fireplace; hands grasp across a bed’s edge. The figures are reduced to outlines and shadows, yet the emotional charge is unmistakable.

The prints bore the signature of Félix Vallotton, a Swiss-born painter and member of the Nabi group who had, until then, been better known for his contributions to literary illustration. The series was titled Intimités, and its ten plates stood as a quiet revolution in modern printmaking. These were not decorative vignettes or narrative scenes. They were compressed dramas—wordless, acerbic, psychologically brutal. And they marked a moment in which the woodcut, an ancient medium long dismissed as archaic or utilitarian, became newly charged with modern power.

The Nabis and the Decorative Turn

By 1898, Vallotton was loosely affiliated with Les Nabis, a Paris-based collective of young artists that included Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, Maurice Denis, and Paul Sérusier. Though diverse in temperament and method, the Nabis shared a commitment to integrating the visual arts into the rhythms of daily life. Their name—“Nabi” meaning prophet in Hebrew—reflected their quasi-mystical sense of artistic mission. Drawing on Symbolism, Japanese prints, and the flattened compositions of Gauguin, they sought to dissolve the boundaries between painting, illustration, furniture, and design.

The Nabis were particularly drawn to the decorative potential of graphic art. They viewed posters, book illustrations, and prints not as inferior to painting, but as parallel expressions of the modern spirit. Vallotton, whose precise draftsmanship and acid wit set him apart from the more dreamlike moods of Bonnard or Vuillard, embraced this aesthetic pluralism with intensity. By the late 1890s, he had begun to experiment seriously with the woodcut—reviving a medium that had lain dormant in the fine arts since the Renaissance.

His early prints explored scenes from urban life: boulevards, theatergoers, anarchist demonstrations. But it was with Intimités that Vallotton found his true voice. Here, the street was replaced by the home, and the spectacle by the private sphere. Yet far from offering warmth or comfort, these interiors pulsed with dread.

The War Inside the Drawing Room

Each print in Intimités presents a scene of apparent domestic normalcy—married couples, drawing-room conversations, visits from lovers. But Vallotton strips these scenes of sentiment. The compositions are brutal in their economy: two or three figures, locked in ambiguous relation, defined only by light and shadow. No shading softens the contrast. Light becomes not illumination but exposure, and darkness a site of threat.

In one print, titled The Lie, a man whispers into a woman’s ear as she turns away, her face unreadable. In The Money, a man hands a bill to a woman in black, her body tense with resignation. In The Irreparable, a man kneels on a bed beside a collapsed woman, the aftermath of some private violence rendered in mute geometry.

These are not illustrations of a specific story. They offer no resolution, no explanation. Each image is a fragment of a larger, unspoken narrative. In this, Vallotton anticipates both the psychological disquiet of later modernism and the cinematic language of suspense and implication. The viewer becomes a voyeur, yet is offered no satisfaction—only unease.

Japan, Germany, and the Flat Knife

Vallotton’s woodcuts are frequently linked to the influence of Japanese ukiyo-e prints, which had flooded the Paris art world since the 1860s. Like the Japanese masters, Vallotton emphasized bold contours, asymmetric composition, and the use of empty space. But where Hokusai and Hiroshige celebrated pleasure, rhythm, or poetic moment, Vallotton introduced a moral chill. His world was not floating—it was frozen.

More surprising is the influence of German Renaissance printmakers, especially Hans Holbein and Albrecht Dürer. Vallotton admired the austerity and exactitude of their line work, as well as their moral severity. His decision to avoid hatching or gradation, and instead work in flat areas of black and white, was a radical aesthetic choice in an age increasingly defined by painterly touch.

It was also a statement of purpose. In a time when impressionism and post-impressionism had expanded the language of color and texture, Vallotton moved in the opposite direction—toward formal clarity, narrative ambiguity, and psychological compression. His prints did not charm. They accused.

Domesticity as Theater of Violence

What makes Intimités so unsettling is its refusal to romanticize the private sphere. At a time when middle-class life was often idealized in painting—especially in the softly lit interiors of Vuillard or the sentiment-laced portraits of bourgeois families—Vallotton offered something closer to an X-ray. He showed the home not as refuge, but as a site of negotiation, resentment, and repression.

The bourgeoisie, which dominated cultural production and patronage in 1890s Paris, saw itself reflected in these scenes. But not flatteringly. These were not noble allegories or idealized domestic bliss. They were glimpses of conversations too painful to overhear, of gestures just before or just after betrayal. There is little eroticism in these prints, even when depicting lovers. The male figures are often stiff, looming, or retreating. The women are watchful, resigned, calculating. No one is innocent.

This moral coldness, combined with the visual starkness, gave Vallotton’s work a chilling modernity. In retrospect, one can see in these prints the germ of 20th-century psychological realism, from film noir to the theater of Pinter or Beckett. Vallotton was not interested in beauty. He was interested in truth—and how it hides.

The New Seriousness of Print

By 1898, printmaking in France was no longer considered a merely reproductive or decorative practice. The efforts of artists like Toulouse-Lautrec, Bonnard, Redon, and Vallotton had restored the graphic arts to intellectual seriousness. Journals like La Revue Blanche and L’Estampe originale treated prints as sites of experimentation and critique, not just illustration.

Vallotton’s success with Intimités confirmed that the print could function as autonomous artwork—narrative, modern, moral. His woodcuts sold widely, were exhibited seriously, and attracted both praise and controversy. They also influenced other artists in Europe and abroad, particularly in Germany, where the early Expressionists would adopt the woodcut as their preferred medium of anxiety and protest.

What Vallotton had discovered was that the limits of woodcut—its refusal of subtle shading, its dependence on outline—could be a source of new precision. The medium, so often associated with the past, had become a tool for diagnosing the present.

A Revolution in Restraint

The revolution that Vallotton staged in 1898 was not loud. It came not with manifesto or mural, but with a small black square of paper, a few lines of ink, and a man and a woman in a silent room. And yet, in those scenes, something in art shifted. The domestic world—so long the domain of sentimental genre painting—was recast as a site of menace and ambiguity. The print—so long a reproductive form—became a scalpel.

In a century that would soon erupt into violence, Vallotton offered an early glimpse of the cold, interior battles already underway. He showed that the worst injuries were often invisible. And that intimacy, too, could leave a scar.

Chapter 5: Zorn, Sorolla, and the Question of Light

Sunlight, Interrupted

In an era of allegory and abstraction, two painters stood apart—not in rebellion, but in devotion. Joaquín Sorolla in Spain and Anders Zorn in Sweden had little interest in the symbolist haze that hung over much of the European avant-garde in 1898. They did not reject modernity, but they interpreted it differently: not as rupture or despair, but as an opportunity to see the world more fully, to trace its brilliance across skin and water, fabric and sea foam. In their hands, realism became not a matter of fidelity, but of intensity. They painted not what the eye sees, but what light reveals.

Both artists occupied an unusual position in 1898: widely admired, commercially successful, and technically dazzling, yet largely excluded from the histories being written by critics enthralled with Parisian experimentation. Their paintings hung in major exhibitions across Europe, and their portraits were sought after by aristocrats, bankers, and royalty. Yet their influence remained strangely subterranean, partly because what they pursued—clarity, atmosphere, sensation—was so hard to theorize. In a century rushing toward fracture, Zorn and Sorolla still believed in the visible.

Sorolla: The Anatomy of Sunlight

By the late 1890s, Joaquín Sorolla had become a master of the Mediterranean sun. His earlier works, often concerned with social themes and grounded in Valencian life, had begun to dissolve into light. The figures remained, but they were increasingly defined not by line or gesture, but by how sun wrapped around them—how it bounced off sails, filtered through linen, or refracted in seawater.

His technique evolved rapidly during this period. Rather than build form through tonal modeling, Sorolla developed a method that relied on temperature contrast: warm highlights against cool shadows, bright skies against lavender skin, the radiant push of late afternoon sun pressing against the folds of a dress or the curve of a shoulder. He did not paint sunshine; he painted the sensation of standing inside it.

A work from earlier in the decade, The Return from Fishing, gives some sense of the trajectory. Two fishermen strain to haul a boat ashore as a white ox trudges forward. The sails rise behind them like an abstract field of white, filled with light but without weight. The water shimmers, but it is the air—vibrant, transparent, kinetic—that dominates the painting. Though not from 1898 exactly, this painting crystallizes the ethos Sorolla would carry through the decade: a realism where color and light displace anatomy and story.

In 1898 itself, Sorolla continued to refine this vision in smaller coastal scenes and figure studies, many of them painted en plein air near Valencia. His palette grew lighter, his brushwork more open. Children on the beach, women carrying jugs, sunlit water lines—all became exercises in how quickly and accurately the eye could register shifts in color and light. It was not Impressionism in the French sense; Sorolla’s technique was more robust, his compositions more grounded. But the goal was parallel: to capture the flicker of perception before the mind imposed order.

Zorn: Firelight and Flesh

While Sorolla basked in Spanish sunlight, Anders Zorn explored the glow of northern firelight and the shimmer of skin against snow. Zorn, born in Mora, Sweden, trained as an academic painter but quickly moved toward a looser, more immediate handling of paint. By 1898, he was one of Europe’s most sought-after portraitists, rivaling John Singer Sargent in both reputation and output.

What set Zorn apart was his ability to render texture and tone with a limited palette. He famously worked with just four colors—white, black, yellow ochre, and vermilion—yet from these he conjured the full range of life. His paintings of bathers, nudes, and self-portraits shimmered with vitality, not through detail but through temperature and rhythm.

In works from the late 1890s, Zorn’s women appear not as mythological nudes, but as physical presences: full-bodied, strong, and modern. The setting is often unremarkable—a riverbank, a small cabin—but the light, whether from a kerosene lamp or the last rays of a Nordic summer day, transforms the scene. Zorn’s genius was to treat light not as background or atmosphere, but as a sculpting force.

Portraits from 1898 show the same command. His subjects—politicians, intellectuals, musicians—are caught in moments of both formality and ease. The faces are precise, but it is in the surrounding textures—silk, skin, beard, collar—that Zorn’s skill emerges. He understood that light touches everything differently, and that to paint light was to paint character.

Painting Without Shadows

What united Sorolla and Zorn was their rejection of chiaroscuro. The academic tradition had long taught that form should emerge from shadow—that depth was created by controlling value. Both painters abandoned this principle. For them, shadow was not the foundation of vision but its residue. They painted as if light alone could model the world.

This approach puzzled some critics. The works appeared unfinished, too bright, too loose. But to the artists themselves, this was fidelity of a higher order. Real light is harsh, inconsistent, quick. To paint it was to risk instability. But it also allowed access to a new kind of realism—one rooted not in ideal form but in sensory truth.

This change coincided with a broader shift in late 19th-century painting. Across Europe, artists were beginning to reconsider the hierarchy of tone, form, and color. Impressionism had already broken the old academic rules, but Sorolla and Zorn pushed further—not toward abstraction, but toward immediacy. Their realism was not nostalgic. It was experiential.

The Politics of Perception

The popularity of these painters in 1898 raises a question. If their work was so widely admired—by critics, patrons, and other artists—why were they largely excluded from the avant-garde narratives of modernism? Part of the answer lies in geography. Neither Paris nor Berlin was their primary base. Part lies in style: neither artist claimed revolutionary intent. And part lies in politics.

Zorn and Sorolla painted people, places, and sensations with a clarity that seemed apolitical. They did not engage in the overt symbolism or social critique that characterized much of contemporary European painting. But that surface neutrality is deceptive. What they offered was a quiet radicalism: the belief that close attention—to flesh, light, color—was itself a kind of resistance. In an age increasingly defined by fragmentation, their work insisted on coherence.

More importantly, they challenged the notion that modernity had to be ugly, dissonant, or opaque. Their paintings offered no allegories, no manifestos. But they did offer a vision: of bodies in sunlight, of faces lit from within, of the world as it could be seen, if one looked.

An Unclaimed Legacy

Today, the work of Zorn and Sorolla occupies an ambiguous place in the history of modern art. Too accomplished to ignore, too traditional to canonize, they remain on the edges of narratives still shaped by rupture and rebellion. But in 1898, they were central—not to theory or controversy, but to the act of painting itself.

Their work asked a simple but profound question: what happens when you remove the veil? Not the veil of illusion, but of interpretation—when you try to see the world not as a metaphor, but as it appears in a flash of light? That question has no final answer. But in the hands of Sorolla and Zorn, it yielded images that remain luminous, not because of what they mean, but because of how they see.

Chapter 6: The Salon and Its Discontents

A Ceremony Grown Hollow

By 1898, the Paris Salon still opened each spring with its usual ceremony, as it had for generations. The venue was impressive—the Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées gleamed with republican grandeur. Catalogues were printed, juries assembled, medals awarded. Thousands of works covered the walls in salon-style hangs, frame beside frame, from floor to ceiling. But something had changed. Though the institution moved with the ritual confidence of an empire, its relevance was slipping. Among critics and artists alike, the question hung in the air: was the Salon still the center of French art, or merely its residue?

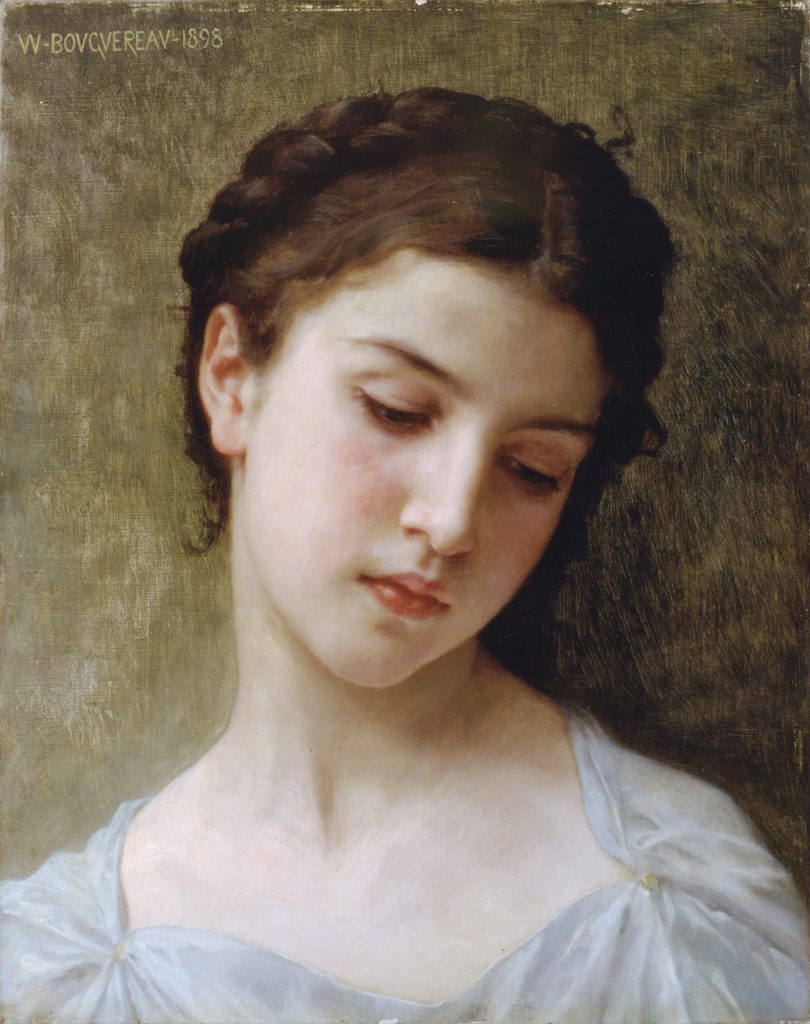

Throughout the 19th century, the Salon had been the single most important showcase in France—and arguably the world—for painting and sculpture. Its endorsement could launch careers; its rejection could ruin them. Painters like Ingres, Delacroix, and Bouguereau had made their names here. But by the last decade of the century, the authority of the Salon was being eaten away by internal stagnation and external challenge. The very success that had once made it indispensable now made it inert.

Competing Visions, Fractured Publics

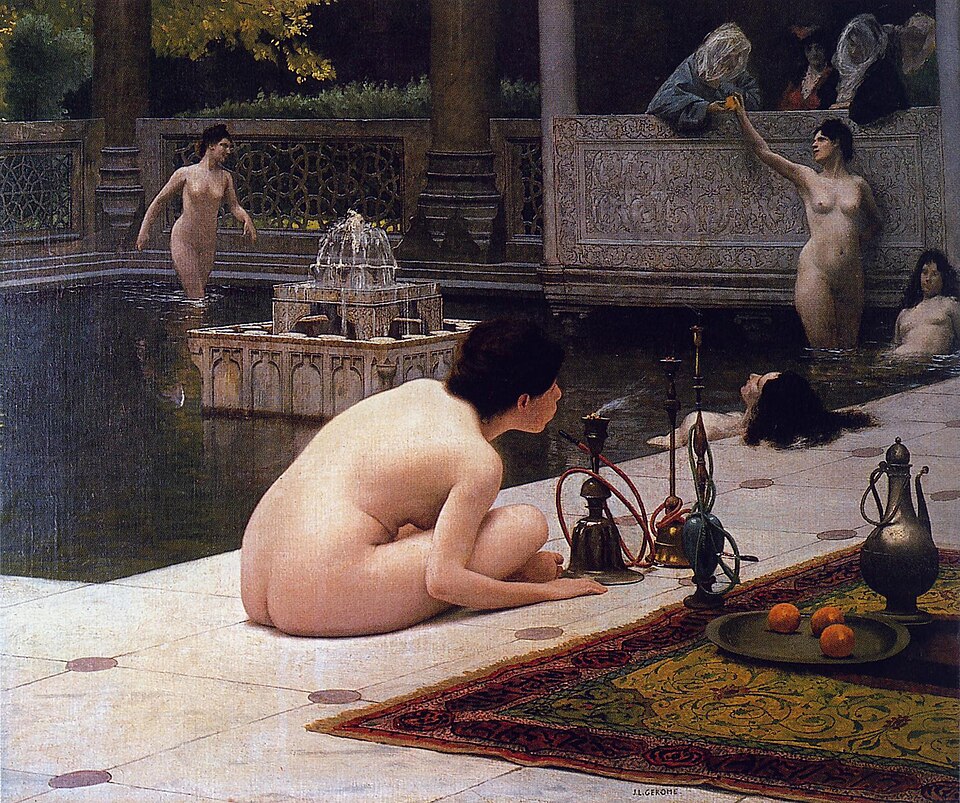

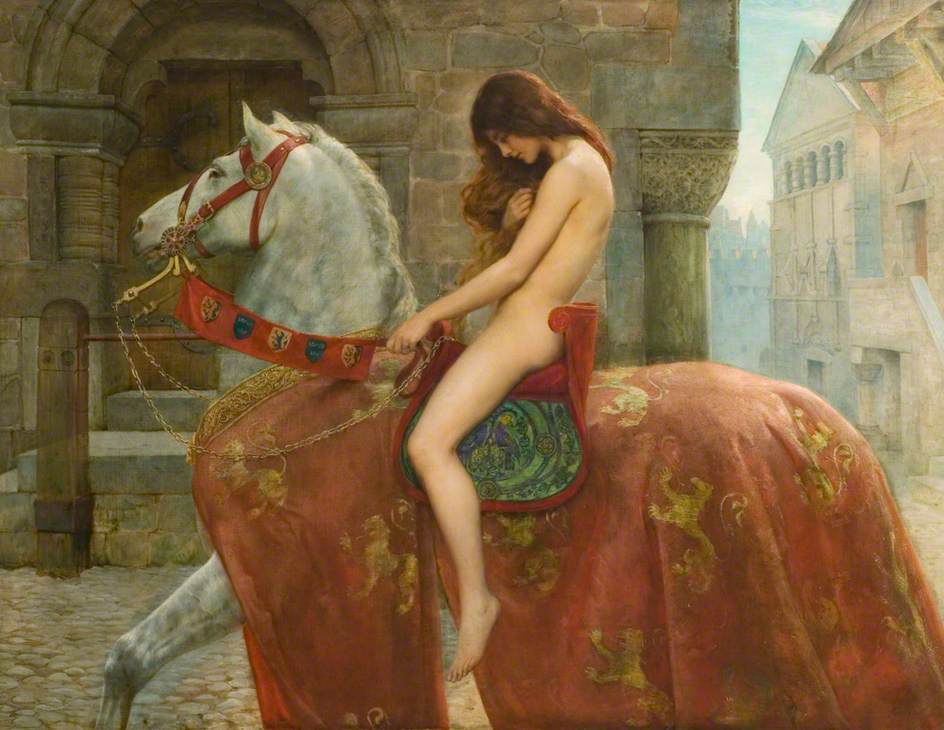

The Salon of 1898 was organized, as in previous years, by the Société des Artistes Français. While still robust in numbers, the exhibition bore the marks of exhaustion. The majority of its works adhered to predictable themes: grand mythological allegories, historical tableaux, military heroics, classical nudes, and sentimental genre scenes. Technical skill was abundant, but innovation was scarce.

Outside its walls, however, the Paris art world had changed. Independent salons and exhibitions had proliferated since the 1880s. The Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, founded in part to counter the conservatism of the official Salon, mounted its own rival exhibition nearby. The Salon des Indépendants offered space for unjuried, avant-garde work. The Salon de la Rose+Croix appealed to Symbolist mysticism. Artists’ groups, private galleries, and illustrated journals had begun to supplant the Salon as the place where new ideas took root.

This fragmentation reflected not only institutional rebellion but also the division of publics. In earlier decades, the Salon had drawn a unified audience—aristocrats, middle-class viewers, students, critics—all mingling under a shared assumption of what art should be. But by 1898, no such consensus remained. The bourgeoisie still admired academic finesse; the younger generation gravitated toward risk. Symbolists wanted ambiguity; realists wanted clarity. Traditionalists praised finish; modernists preferred process.

The result was a kind of dissonance: the Salon presented itself as the mirror of French taste, but no longer reflected the culture forming outside its gates.

The Tyranny of the Jury

At the heart of the Salon’s crisis was the jury system. The juries—composed largely of older academic painters—tended to favor works that fit established genres: history painting, portraiture, mythological allegory. This system protected a certain aesthetic code, but it also insulated the institution from change.

Younger artists who submitted bold, experimental works were routinely rejected or marginalized. Some adapted their style to increase their chances; others abandoned the Salon entirely. What emerged was a cycle of mutual mistrust: artists accused the Salon of being out of touch; the Salon dismissed them as unserious.

In 1898, this tension was palpable. While the official Salon presented hundreds of technically accomplished canvases, few were discussed in critical circles with urgency. Even the awards and purchases—once major news—now felt ceremonial. Critics remarked on the competence of the entries, the elegance of composition, the skillful anatomy. But words like “surprising,” “original,” or “urgent” appeared less and less.

The Ghost of Moreau

In the same year, the death of Gustave Moreau added another note of transition. Moreau had once been a fixture of the Salon—a painter of mythic dreamscapes and visionary symbolism—but had also taught younger artists who would eventually abandon its constraints. In the 1898 Salon, his absence was not remarked in grand speeches, but his presence lingered in the undercurrents. Several Symbolist painters exhibited works that bore his influence: strange narratives, ambiguous figures, decorative flatness.

Their inclusion, however, was marginal. Such works were hung on peripheral walls, low-traffic areas, or clustered as curiosities. The Salon tolerated them, but did not embrace them. Even as tastes changed, the institution could not fully absorb the new.

This resistance was not ideological so much as structural. The Salon had been designed to elevate a shared civic taste. It was an institution of consensus. But art in the 1890s had become a space of conflict—between reason and dream, nation and self, tradition and rupture. The Salon, built to house harmony, could not contain the noise.

Dignity Without Direction

One of the paradoxes of the 1898 Salon was its continued success. Attendance remained high. Sales were steady. The public still came. The problem was not absence—it was inertia. The Salon functioned, but without leading. It preserved a culture that no longer needed preserving.

That culture—academic, republican, cosmopolitan—had long believed in the capacity of art to instruct and uplift. In 1898, it still commissioned busts of statesmen and allegories of liberty. It still hung monumental canvases filled with pale goddesses and martial heroes. But fewer and fewer artists believed in that vision. The public admired it, perhaps, but with a growing sense of formality, even nostalgia.

By contrast, in the smaller salons and private galleries, new experiments were underway. Artists tested color theory, dream logic, psychological ambiguity, spiritual symbolism, and formal breakdown. The Salon had once feared revolution; now it feared irrelevance.

A Fading Empire of Frames

In the years that followed, the Salon would continue to operate, but as one venue among many. It would never again dictate the direction of art. Its reputation would become that of a relic: the place where the past lived on in polished form.

But in 1898, the tension was still unresolved. To walk through the Salon that year was to experience a strange duality: the confidence of the institution and the doubt in the air. The walls were covered, the lights adjusted, the juries proud. But among the younger visitors, in whispers and gestures, one could feel the shift.

The age of the Salon was not over—not yet. But its center no longer held. And the most vital energy in Paris had already moved on.

Chapter 7: The Crisis of Sculpture

A Monument Refused

In the spring of 1898, the Société des Gens de Lettres unveiled a full-scale plaster model of Auguste Rodin’s Monument to Balzac at the Salon. It had taken the sculptor seven years to produce. Commissioned in 1891 to honor the great novelist, the monument had been delayed, debated, postponed, and finally, when revealed, rejected. The refusal was not procedural—it was symbolic. The Society deemed the work an insult. What they had expected was a likeness. What they received was a vision.

Rodin’s Balzac did not resemble the man’s known portraits. It stood upright, robed like a prophet or a ghost, its features generalized, its form thick, abstract, looming. Critics were appalled. Some compared it to a swollen mummy. Others called it a mockery of the Republic. Even allies were stunned by its audacity. There was little precedent for such distortion in public sculpture. Rodin had offered not a commemorative image, but a psychological presence: Balzac as energy, as idea, as force.

This episode marked a turning point. The public rejection of the Balzac was not merely a scandal—it revealed a fracture in the very function of sculpture. For centuries, sculpture had been the art of solidity: weight, likeness, permanence. But in 1898, the medium began to lose its center. Artists were no longer sure what sculpture was for, or what it should represent. The old ideals of form and heroism no longer held. The crisis was not technical. It was existential.

Solid Form, Fading Purpose

The late 19th century had been a golden age of public monuments. Cities across Europe filled their squares and boulevards with generals, poets, martyrs, and myths. In bronze and marble, civic virtue was made visible. The statue functioned as pedagogy, as commemoration, as a kind of civic scripture. Rodin himself had been shaped by this tradition. His early commissions—like The Burghers of Calais—had tested its limits but still played within its bounds.

By the 1890s, however, the terms had begun to shift. Sculpture was increasingly out of step with painting, which had embraced symbolism, interiority, and abstraction. In galleries and private collections, smaller-scale sculptures proliferated, often in more delicate materials: wax, plaster, clay. These works were not meant for public spaces. They did not declare meaning. They suggested it.

In this changing context, Rodin’s Balzac became a flashpoint. It was intended for public honor, yet rejected as indecipherable. Its monumentality could not save it, because its meaning did not match its mass. The reaction to the work laid bare the unspoken expectations still governing sculpture: that it be comprehensible, reverent, literal. Rodin had violated all three. He had asked sculpture to become poetic.

Rosso: The Disappearance of Mass

If Rodin cracked the form, Medardo Rosso dissolved it entirely. The Italian sculptor, working in Paris in the 1890s, pursued a vision of sculpture that defied the classical norms of permanence, clarity, and anatomical fidelity. He cast in wax, plaster, and sometimes bronze, but always with an eye toward flux rather than solidity. His figures blurred at the edges. Details softened into atmosphere. The form did not assert itself against the space around it—it seemed to leak into it.

Rosso’s Sick Child, produced in multiple versions during the decade, encapsulates this approach. A child’s face emerges from a mass of textured wax, barely defined, almost spectral. The features seem in motion—not in time, but in perception. There is no clear beginning or end to the figure. It flickers in and out of form, like a memory recalled at the moment of forgetting.

To traditional eyes, these sculptures looked unfinished. But Rosso was not careless—he was deliberate. His work proposed a new idea: that sculpture, like painting, could evoke rather than define. That light, shadow, and mood could replace anatomy and gesture. That the material itself—fragile, luminous, impermanent—could be part of the subject.

This was more than aesthetic experiment. It was a philosophical departure. Rosso believed that modern life was not reducible to heroes or myths. It was fragmentary, contingent, fleeting. To sculpt it truthfully, one had to abandon marble certainties. One had to accept disappearance.

The Weight of the Public

The crisis of sculpture in 1898 was also a crisis of the public. Who was sculpture for? For most of the 19th century, the answer had been simple: the nation. The state commissioned statues; citizens passed them daily. They reinforced identity, memory, and power. But by the century’s end, the nation itself had grown unstable. France, in the throes of the Dreyfus Affair, was no longer a unified civic audience. Empire and democracy sat uneasily together. The arts reflected this tension.

Public sculpture could not reconcile the divides. Its language—allegorical, didactic, grand—no longer matched the political mood. Yet private sculpture had no clear path either. Collectors hesitated before abstract forms. Critics lacked a vocabulary for the new. Museums had little place for experimental wax heads or semi-melted busts. Sculpture, long a civic art, found itself homeless.

In this vacuum, artists like Rosso and Rodin continued to work, but their audiences changed. Their sculptures became not declarations but questions. What is presence? What is memory? Can form survive without clarity?

A Future Sculpted in Uncertainty

Rodin’s Balzac would not be cast in bronze until decades later, and only then as a kind of retrospective vindication. Rosso remained admired by some and ignored by many. Yet between them, they redrew the boundaries of their medium. They did not destroy sculpture—they unmoored it.

What followed in the 20th century—Brâncuși’s distillations, Giacometti’s ghosts, Moore’s voids—would be unthinkable without the hesitations of 1898. The year marked not the end of monumentality, but the recognition of its limits. It showed that mass alone no longer conferred meaning. That to endure, sculpture would have to become lighter, more uncertain, more aware of its own vanishing.

In that light, the crisis was not a failure. It was a passage. The pedestal remained. But what stood upon it had begun to change.

Chapter 8: The American Turn — Sargent, Eakins, and New Ambitions

Portraits Across the Ocean

In 1898, the transatlantic current in art was unmistakable. American painters who had once made pilgrimages to Europe for training, commissions, and prestige were no longer simply students of the Old World. They had become arbiters of taste themselves—cosmopolitan figures whose work shaped not just the image of America, but the image of modernity itself. Among them, John Singer Sargent stood at the apex: celebrated, envied, and sometimes quietly resented for his effortless fluency in the languages of elegance and oil paint.

Sargent, though born in Florence and trained in Paris, was unmistakably American in origin, and by the late 1890s, his career represented something new. He belonged neither wholly to Europe nor to the United States, yet moved between them with ease. His portraits—of aristocrats, industrialists, artists, and musicians—carried the mark of a global elite. In them, one could glimpse both the grandeur of inherited wealth and the anxiety of self-presentation in a changing age.

In 1898, Sargent was producing portraits at a formidable pace. His clientele expanded on both sides of the Atlantic. Though no single painting from that exact year stands as a defining masterpiece, his output reflects a consistency that verged on dominance. Each canvas balanced technical brilliance with psychological ambiguity: faces half-turned, hands relaxed but rehearsed, drapery rendered in liquid strokes that suggested both presence and performance.

For Sargent, portraiture was not merely record. It was negotiation. Between sitter and painter, between image and self, between surface and suggestion.

The Weight of Flesh: Eakins and American Gravity

While Sargent moved through drawing rooms and diplomatic circles, Thomas Eakins, working in Philadelphia, was digging in. If Sargent’s brush was all elegance and fluency, Eakins’s was deliberate, weighty, and anatomical. He was not interested in elegance. He was interested in truth—and truth, in Eakins’s view, required the body.

His 1898 painting Taking the Count, which depicts a boxing match at the moment a fighter is down, exemplifies this focus. The fallen figure sprawls on the canvas, legs askew, face turned. The referee hovers, counting out. The spectators blur in the background. The tension is physical, temporal, irreversible. There is no heroism here—only fatigue, gravity, and the reality of flesh in motion.

Eakins had always pursued the human form with obsessive precision. Trained in anatomy, a student of both medicine and the old masters, he believed that the body was the foundation of painting. Not just its subject, but its language. In an era when much of American art still leaned toward sentiment or idealization, Eakins insisted on fact. Muscles, bruises, wrinkles, scars. His realism was not photographic. It was moral.

By 1898, Eakins had long since alienated many patrons and institutions. His teaching methods—insisting on nude study, even in mixed classes—had caused scandal. His disdain for commercial flattery had closed doors. Yet he remained committed. His art was American not by theme, but by temperament: stubborn, grounded, resistant to illusion.

Museums Rise, Markets Shift

The 1890s were also a decade of infrastructure. Across the United States, new museums and academies opened their doors. Institutions such as the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York expanded their collections, publications, and prestige. Though still young compared to their European counterparts, they began to assert their own standards, their own ambitions.

For American artists, this shift mattered. No longer entirely dependent on Paris for recognition, painters like Sargent and Eakins could now imagine careers anchored at home. Collectors, too, began to look inward. While many still valued European work, there was growing interest in cultivating a national school—something distinct, serious, and worthy of permanence.

This was not merely patriotic. It was institutional. American art needed museums in which to grow, critics to interpret it, schools to train the next generation. The infrastructure was forming. By 1898, the conversation had changed. The question was no longer whether Americans could paint like Europeans. It was whether they should.

Diverging Visions

Sargent and Eakins, often compared, could not have been more different. One moved among elites, the other walked alone. One painted silk, the other painted sweat. Yet both represented the ambitions of American art at the fin de siècle: to matter, to endure, to prove that art in the United States was not merely provincial imitation but cultural production of weight.

Their differences illuminate the poles between which American painting moved in 1898. On one side, cosmopolitan polish: a fluency in European styles, a mastery of surface, a responsiveness to social codes. On the other, empirical gravity: an insistence on observation, on physical truth, on the body as subject.

Both directions had merit. Both would persist. But they suggested a broader truth: that American art, even in its moments of greatest self-confidence, was divided between two impulses—aspiration and introspection, performance and doubt.

Toward a National Vision

The end of the century found American painting at a crossroads—not of style, but of identity. The confidence that had animated the Gilded Age was tempered by economic anxiety, cultural uncertainty, and the lingering question of purpose. What should art do in a society defined not by aristocracy or church, but by commerce, pluralism, and expansion?

Sargent answered with elegance: paint the world’s surface with such precision that its depths shine through. Eakins answered with rigor: show the body, and you show the truth. Between them, they defined an American realism that would echo into the next century—through Ashcan painters, regionalists, and modernists alike.

In 1898, they were not anomalies. They were signs. That American art had arrived. And that it had work to do.

Chapter 9: The Symbolist Spiral

Dreams Without Anchors

In 1898, Symbolist painting no longer needed to justify itself. What had once seemed an esoteric reaction to realism had grown into an aesthetic language in its own right: diffuse, seductive, hermetic, and almost proudly aloof. By the end of the decade, Symbolism had developed its own iconography—mystical women, closed eyes, empty seascapes, mythic creatures, austere portraits—and its own logic: the inner world mattered more than the outer, suggestion outweighed description, and feeling eclipsed fact.

Yet the mood in 1898 was not triumphant. It was fugitive, coiled, unsure. The great moments of Symbolist assertion—such as the Salon de la Rose+Croix, which had organized its final exhibition the previous year—were already fading. Its prophet-organizer, Joséphin Péladan, had withdrawn into mysticism, and the salons he had championed were now looked on with equal parts nostalgia and amusement. Even the artists most closely associated with Symbolist ideals sensed that the spell was breaking. What had begun as revolt had become repetition.

Still, some painters continued to refine the language—quietly, darkly, and with increasing inwardness. If Symbolism had started as a retreat from the outer world, it now risked becoming a retreat from itself. Its most compelling images from 1898 do not proclaim or define; they hesitate, circle, spiral.

Khnopff and the Androgynous Threshold

No painter embodied this atmosphere more fully than Fernand Khnopff. The Belgian artist had, throughout the 1890s, developed a visual world suspended between dream and ritual. His figures rarely acted. They floated, looked away, or stared back without expression. The spaces they inhabited—minimal, symmetrical, often bordered by water or fog—suggested neither place nor memory, but a third state: something ungraspable.

His earlier work Caress of the Sphinx, completed in 1896, remained a touchstone in 1898 for Symbolist painters and critics. In it, a sphinx leans affectionately against a pale, androgynous youth. There is no violence, no sexuality, no narrative. Only proximity. The caress is not physical but metaphysical: an intimacy without explanation. The painting’s surface gleams with polished control, but beneath it lies a strange discomfort. Who touches whom? What do they share? What are we being shown?

Khnopff’s influence continued in 1898 not through new exhibitions, but through presence—his images circulated in journals, private collections, and conversation. He represented a version of Symbolism stripped of bombast. No saints, no roses, no sigils. Just stillness, tension, and unresolvable desire.

Osbert and the Ethereal Horizon

In France, Alphonse Osbert carried Symbolist ideals into the landscape, though his “landscapes” were more stage than earth. His paintings from the late 1890s present robed women under violet skies, lit by crescent moons or distant suns. Their color range is narrow—silver, blue, soft gold—and their figures often repeat, as if drawn from a private liturgy. Time does not pass in these paintings; it gathers.

Osbert’s work in 1898 distilled the Symbolist instinct to its essence: atmosphere without event. The human presence is not individual but emblematic. His women do not suggest character, only mood. Light becomes emotional, not spatial. In this, Osbert shared affinities with the musical Symbolists—composers like Debussy, whose Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune had, a few years earlier, explored the dissolution of time in sound.

This dissolution was the point. Symbolism, by 1898, had ceased to be concerned with the visible world. It no longer protested against realism. It simply ignored it. Its canvases depicted neither dreams nor memories, but the feeling of entering one.

The Death of Moreau

That same year, Gustave Moreau—once the central figure of French Symbolism—died in Paris. His legacy was both profound and unresolved. In life, Moreau had combined mythological erudition with painterly excess: opulent surfaces, cryptic allegories, and an obsession with ancient sources. His students had included Henri Matisse and Georges Rouault. Yet by 1898, Moreau’s vision was already receding. His ornate, narrative-heavy compositions—once radical in their departure from realism—now seemed distant from the pared-down Symbolist mood taking hold in Brussels, Vienna, and Munich.

Moreau’s death did not cause a rupture, but it marked the end of a possibility: that Symbolism might still serve history, that it could dramatize, instruct, or dazzle. What followed him was more inward, more hushed. The loud symbolism of peacocks, chalices, and prophets gave way to eyes half-closed and landscapes barely touched by light.

Still, his influence lingered—in the vocabulary of myth, in the elevation of suggestion over statement, and in the belief that painting could still summon the spiritual without the aid of religion or tradition. Moreau had opened the door. Others walked through, though not always in his direction.

Spiral as Structure

The title of this chapter—The Symbolist Spiral—reflects more than mood. By 1898, Symbolism had entered a recursive phase. It circled its own imagery: veiled women, haunted landscapes, ambiguous gestures. It repeated forms, tones, and figures not to develop them, but to deepen their mystery. Some critics called this stagnation. Others called it refinement.

Symbolism had always resisted progression. It valued depth over direction. But even its defenders sensed a loss of momentum. The avant-garde had begun to turn elsewhere: to expressive distortion, to spiritual abstraction, to new graphic languages. The most radical artists of the next decade would cite Symbolism as a source—but also as a limit.

Yet there was power in this inward turn. In refusing public meaning, Symbolist painters forced the viewer to do the work. Their images did not declare; they invited. And in that invitation lay something rare: a space for silence, for reverie, for not knowing.

Exit Signs

By the end of 1898, Symbolist painting had become a world unto itself. Not dead, not yet transformed, but sealed. Its ambitions no longer matched its context. Politics raged in the streets. Psychology reshaped the study of the mind. Technology redrew the map of daily life. And Symbolism floated above it all—untouched, immaculate, increasingly unmoored.

But within that unmooring, there remained beauty. The kind not bound to event or progress, but to state: the state of solitude, of stillness, of seeing without naming. Symbolism had never promised answers. In 1898, it no longer promised even clarity. What it offered instead was a spiral: descending, circling, dissolving. And for those willing to follow it down, that spiral still led somewhere.

Chapter 10: Empire and Exhibition

The Empire Behind the Curtain

In 1898, Europe was a continent obsessed with visibility. Nations clamored not only to dominate economically and militarily, but also to be seen—at home, abroad, and on the grand stages of international exhibition. The visual culture of empire no longer resided solely in maps, uniforms, or shipping manifests. It had begun to take shape in museums, world’s fairs, and galleries—places where power dressed itself in art and spectacle. If art in 1898 struggled with its sense of purpose, the imperial apparatus offered it one: to display, to order, and to impress.

The exhibition was no longer merely a format; it was an ideology. At a time when classical allegory was fading and avant-garde forms were still in gestation, the architecture of empire—pavilions, dioramas, cabinets, glass vitrines—offered a reassuring structure. It told stories of progress, conquest, and civilizational hierarchy with all the confidence that modern art increasingly lacked. And through these spectacles, the logic of imperialism seeped into culture not as argument, but as arrangement.

The year 1898 marked a high point in this visual consolidation. The art world’s ambivalence toward modernity found a counterpoint in the brash certainties of empire on display.

Brussels and the Colonial Spectacle

Although the Brussels International Exposition officially closed in 1897, its effects were felt long into 1898—not least through one of its most notorious features: the colonial section, and in particular the so-called “human zoo” of Congolese people exhibited in Tervuren. It was here, in a leafy suburb of the Belgian capital, that King Leopold II staged a vision of his private colony, the Congo Free State, as a space of exoticism, hierarchy, and tutelage.

That staging involved not only material artifacts—ivory, rubber, fabrics—but also human bodies, brought from Africa and made to perform daily rituals for the Belgian public. Visitors passed through the carefully landscaped parklands, past constructed huts, into the galleries that would eventually become the Royal Museum for Central Africa, which opened in 1898. It was exhibition as fantasy and domination fused into one.

The display served two purposes. It reassured European audiences of the nobility of their imperial missions—suggesting that colonized peoples were primitive but educable. And it distracted from the brutal realities of colonial administration. In this way, exhibitionism did not merely reflect empire. It naturalized it.

For art, this created a conundrum. The fine and decorative arts were displayed alongside ethnographic materials in a kind of aesthetic continuum, one that flattened cultural boundaries under the banner of curiosity and collection. The result was a new kind of visual hierarchy—one that claimed to be scientific, but functioned ideologically.

The Fair as Format

By 1898, the industrial exposition had become a dominant cultural form across the continent. From London’s Crystal Palace to Paris’s 1889 Exposition Universelle, the format had matured into a genre. Each exhibition offered nations the chance to present themselves—industrially, artistically, politically—to domestic and international audiences alike. Fine art was usually included as a major component, but increasingly as part of a broader field of national branding.

In these settings, painting and sculpture did not stand alone. They were framed by architecture, textiles, technological demonstrations, and themed interiors. A canvas was no longer just a canvas; it was an element in a cultural grammar. Visitors did not come to meditate on works of art—they came to be impressed, entertained, educated.

The role of art critics in this environment was diminished. What mattered was placement, spectacle, and circulation. Nations competed not only on aesthetic grounds but on the ability to construct immersive environments—pavilions that simulated colonial outposts, factories, or mythologized national pasts. In this sense, the exhibition was not just a container of artworks. It was itself an artwork—composed, curated, and constructed to shape public opinion.

The United States Joins the Parade

Though this chapter focuses on Europe, 1898 also marked the entry of the United States into the imperial competition—less in artistic terms than in geopolitical ones. With the conclusion of the Spanish-American War that year, the United States acquired new overseas territories: Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. While American visual culture had not yet developed a fully imperial aesthetic in the European mode, its institutions—museums, exhibitions, government-sponsored art—would soon follow suit.

What is notable in 1898 is how smoothly the European exhibition model adapted to new imperial contexts. The logic of categorization, hierarchy, and display proved exportable. Whether in Brussels or Boston, the world could be arranged and viewed from behind a velvet rope.

Art in Service

For academic painters who still enjoyed official commissions, the imperial turn provided a clear purpose. Historical painting—so beleaguered in avant-garde circles—found a new lease on life in colonial subjects. Artists painted generals in tropical uniforms, allegories of civilization raising the native from savagery, scenes of conquest rendered with classical dignity. These images adorned official salons and government buildings, helping to cement the narrative of righteous expansion.

Decorative artists, too, found opportunity in empire. Exotic motifs were lifted from colonized cultures and adapted for domestic interiors, furniture, and textiles. What had once been considered primitive was now desirable—so long as it could be disciplined into Art Nouveau lines or Orientalist tableaux.

In this way, the arts adapted to the imperial imagination without always declaring allegiance. Some did so willingly, others through silence. Aesthetic ambition found patrons in ministries of colonies and departments of foreign affairs. Prestige followed power.

The Absence of Doubt

If there was resistance to this machinery in 1898, it was faint. The most visible critics of imperial culture were not visual artists but writers, some of whom would soon begin to question the moral foundations of the system. But for now, in exhibitions, pavilions, catalogues, and galleries, doubt was not in fashion.

Artworks that questioned the empire—or even acknowledged its violence—were rare. Instead, what the imperial exhibition offered was a curated certainty: that history moved in one direction, that civilization had one center, and that art could illustrate, affirm, and even beautify this belief.

In the aesthetic realm, the effect was constricting. The more empire insisted on clarity and message, the more art became decorative or illustrative. Ambiguity was suspect. Irony had no place. Complexity was a danger.

Epilogue in Display Cases

By the end of 1898, the foundations had been laid not only for new museums of empire, but for a new way of thinking about art itself—as something that must travel through categories of race, region, and relevance. The exhibition replaced the altar. The vitrine replaced the easel. A fragment of sculpture, a textile, a tool, and a painting could all be placed side by side, their meanings subordinated to the order of the curator’s hand.

Art, once thought to lift the viewer above the world, now offered to map it. But in doing so, it risked becoming just another object in the imperial archive—measured, labeled, admired, and filed away.

Chapter 11: Modern Architecture’s Nervous Beginnings

Stone Skins and Steel Bones

By 1898, the facades of Europe still bore the weight of the past. Streets were lined with structures dressed in Renaissance, Gothic, or Baroque costume—decorative survivals meant to reassure the eye, not provoke it. But beneath those decorative skins, something was shifting. Architects across the continent had begun to speak in a new idiom, one shaped not by history, but by steel, glass, hygiene, and nervous anticipation. Their buildings whispered that tradition might no longer be enough.

The shift was not yet triumphant. It was subtle, uncertain, at times self-contradictory. It manifested in corners of the city—in apartment blocks, in pavilions, in furniture, even in manhole covers. And while the new architecture had not yet declared war on ornament, it had begun to question what ornament was for. The nervousness was architectural and philosophical: could buildings still express meaning in a culture that had stopped believing in inherited forms?

The answer came not in a manifesto—though there were those—but in materials, surfaces, and layout. A new kind of structure was emerging. One that reflected not just how people lived, but how they might live differently.

Otto Wagner and the Viennese Fracture

Nowhere was this tension more visible than in Vienna. At the twilight of empire, the city was at once stately and strained. Its wide boulevards, lined with government palaces and cultural monuments, spoke of authority. But just beyond them, in the turn-of-the-century apartment blocks being erected for the middle class, a quieter revolution was underway.

Otto Wagner stood at the center of it. By 1898, Wagner had completed a series of apartment buildings along the Linke Wienzeile, a new development corridor running parallel to the River Wien. The most notable of these—known now as the Majolikahaus and the Medallion House—appeared familiar only from a distance. Their facades had a rhythmic, symmetrical logic. But up close, they broke every expectation of academic architecture.

The Majolikahaus, in particular, stunned passersby with its skin: a glossy ceramic tile cladding, printed with floral designs in pale pinks and greens. There were no columns, no cornices, no sculpted allegories of civic virtue. Instead, there were grids, patterns, textures. The building did not speak the language of the academy. It did not recite. It pulsed.

Wagner’s use of industrial materials was not decorative whim. It was ideological. He believed architecture must respond to its time—to the technologies, the needs, the forms of daily life. In his 1898 second edition of Modern Architecture, he rejected historicism outright. Architecture, he argued, was not the servant of style but of function. Buildings should express their structure, their purpose, and their moment.

A Nervous Modernity

Wagner’s declarations were bold, but his buildings remained transitional. He did not yet strip away ornament. Instead, he recontextualized it. His facades fluttered with stylized motifs—grapes, vines, medallions—not as symbolic decoration, but as rhythmic surface. This was a new aesthetic: abstraction masquerading as flourish. The decoration no longer narrated; it animated.

But even Wagner’s confidence was layered with uncertainty. The apartment blocks, while innovative, still nodded to the street’s expectations. They were not brutalist or confrontational. They were polite radicals. And this ambivalence typified the moment. In 1898, the most forward-thinking architecture was not yet modernist in the later sense. It still bore traces of the old world—even as it hinted at its end.

That tension produced strange beauty. Interiors became experiments in geometry and light. Floor plans shifted to accommodate new domestic routines. Facades moved toward flatness. And yet, everywhere, one sensed hesitation: a fear that to step too far from the past might leave one with no language at all.

The Glasgow Parallel

Meanwhile, in Glasgow, Charles Rennie Mackintosh was developing his own answers. Working with the Glasgow School, Mackintosh merged Scottish baronial architecture with Japanese minimalism and floral Art Nouveau. His designs—both architectural and interior—pushed toward a purified decorative logic: stylized lines, elongated proportions, and a restrained palette.

His projects from the late 1890s—most notably the early stages of the Glasgow School of Art, which would be completed in the following decade—echoed Wagner in their hybridity. The building embraced new spatial ideas: large studios, visible structure, and rhythmic light. But it also indulged in surface play—iron railings that turned into vines, windows that became runes.

Mackintosh’s work struck a chord in Vienna, where it was exhibited and admired. A correspondence of sensibility emerged: both architects embraced a modernism that was emotional as well as functional. They sought not to erase ornament, but to make it meaningful again—less as narrative, more as pulse.

Ornament and Anxiety

What defined 1898 in architecture was not yet form, but feeling. There was a sense—among Wagner, Mackintosh, and their contemporaries—that the old codes were failing. Buildings could no longer rely on inherited grammar. They needed new words, new syntax. But no dictionary existed.

That absence created both freedom and anxiety. Some embraced abstraction. Others turned inward, designing total works of art in which architecture, furniture, lighting, and textiles formed a coherent world. Still others retreated into decorative excess, producing surfaces that shimmered with effort even as structure receded.

In this atmosphere, architecture became speculative. Not utopian, not yet dystopian, but speculative. What would it mean for a building to express modern life? Not as an image, but as an experience?

The answers were fragmentary. A tiled wall. A window grid. A staircase curve. The new architecture did not announce itself. It assembled itself—quietly, piece by piece.

Toward the Edge

By the end of 1898, the cracks in historicism were visible, but the structures of modernism had not yet risen. Architects were experimenting in plan, material, and skin, but the city still resembled its past. The revolution, such as it was, remained beneath the surface.

But it was coming. Wagner’s students would go further. Mackintosh’s interiors would influence Vienna’s Secessionists. The language of modern architecture—efficiency, clarity, honesty—would soon harden into doctrine. For now, it was a question.

And like all serious questions, it began not with clarity, but with unease.

Chapter 12: 1898 in Japan — Kiyochika and the Ghosts of Modernity

Shadows of a Vanishing City

In 1898, the streets of Tokyo were no longer recognizable to those who had known them in childhood. The wooden bridges, winding alleys, and dim lantern-lit quarters of Edo had given way to gaslights, brick buildings, and a growing chorus of industrial noise. The Meiji state’s project of rapid modernization had transformed Japan’s capital into a city of contradictions—where Western uniforms moved through old temples, and telegraph wires hung over traditional rooftops. Amid this transformation, one artist stood quietly at the edge, watching not with nostalgia but with something closer to fatalistic awe.

Kobayashi Kiyochika, then in his early fifties, was still making prints—though fewer than during his prolific 1870s and 1880s. His earlier fame had come from woodblock images of Tokyo under moonlight or firelight, a genre he helped pioneer through the atmospheric style known as kōsen-ga—“pictures of light rays.” But by 1898, his place in the Japanese art world was uncertain. The ukiyo-e tradition from which he emerged had declined under the weight of photographic reproduction, foreign influence, and changing taste. Yet Kiyochika remained, producing images that rendered the city’s new structures—its railroads, steamships, gaslights, and foreign-inspired buildings—not as emblems of progress, but as uncanny apparitions in a vanishing world.

In doing so, he left behind a record not of resistance, nor of celebration, but of reckoning.

Light Without Certainty