The story of Korean art is one of endurance, elegance, and the delicate balancing act between continuity and change. Nestled between powerful cultural forces—most notably China to the west and Japan to the east—Korea’s artistic heritage reflects both its engagement with and resistance to outside influence. Korean art, like the peninsula itself, has been shaped by a deep history of kingdoms, invasions, philosophical shifts, and an enduring sense of identity rooted in the land and its people. From Neolithic earthenware to contemporary digital installations, Korean art traces a path that is as poetic as it is political.

Unlike in the West, where art history often unfolds through the lens of individual genius, Korean art has long been defined by collective tradition and spiritual values. In fact, one of the most persistent themes throughout Korean aesthetics is the notion of harmony—between human and nature, material and emptiness, structure and spontaneity. This core ideal, evident from the earliest bronze mirrors to the brushwork of Joseon literati, resonates even in the high-tech minimalism of contemporary Seoul’s galleries.

Geography and Isolation: Fertile Ground for a Unique Aesthetic

Korea’s geography—mountainous, forested, and bounded by sea—has contributed profoundly to its artistic development. Though it was frequently a conduit for ideas traveling between China and Japan, Korea maintained a unique sense of cultural independence. This paradox of openness and insulation allowed Korean art to absorb external forms while reinterpreting them with native sensibilities. For example, while Buddhism arrived via China, Korean Buddhist art quickly evolved its own iconography, architectural styles, and expressive modes. Similarly, although Chinese ink painting influenced Korean literati, the Korean “true-view” landscape (jin-gyeong sansuhwa) eventually broke away from idealized mountains to depict real Korean scenery.

Korean artists were deeply tied to their environment. The mountains of the peninsula often serve as both literal subjects and metaphorical structures in art, anchoring the Korean worldview in nature’s cyclical rhythms. Unlike the symmetrical gardens of Kyoto or the grandeur of Beijing’s palaces, Korean design typically favors asymmetry, understatement, and the imperfect—qualities celebrated in the philosophy of naturalness (자연, jayeon).

Cultural and Philosophical Foundations

Three major belief systems—Shamanism, Buddhism, and Confucianism—form the spiritual and philosophical triad that has driven much of Korean art. Indigenous shamanistic practices provided early motifs of fertility, protection, and ancestor worship, which can still be seen in contemporary minhwa (folk painting). The introduction of Buddhism in the fourth century had perhaps the most profound impact on Korea’s artistic landscape, spawning temple complexes, serene sculptures, and illuminated sutras. Later, the rise of Neo-Confucianism during the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897) shifted the cultural elite’s focus to calligraphy, moral didacticism, and the intimate, restrained aesthetics of ink painting.

Importantly, these traditions didn’t replace one another—they layered. The shamanistic impulse towards nature spirits and talismans never disappeared; it simply took on new forms in the domestic paintings of the Joseon era or in the tiger-and-magpie motifs seen in folk art. Likewise, Confucian ideals might dominate official court painting, while Buddhist art persisted in private devotion and mountain temples. This interplay of belief systems created a visual culture that was not only rich in symbolism but adaptable across historical epochs.

Mediums and Mastery: A Versatile Visual Culture

Korean art excels in multiple mediums—ceramics, metalwork, calligraphy, painting, and architecture—but perhaps most famously in its ceramics. The Goryeo celadon glaze, with its translucent bluish-green tone, remains one of Korea’s most celebrated contributions to global art history. Joseon porcelain, spare and white, reflects Confucian values of purity and humility. Yet even within these stylistic bounds, Korean artists introduced subtle but groundbreaking innovations: inlay techniques, brush-carved motifs, and organic forms that emphasized function without sacrificing beauty.

The material culture of Korea reflects a deep sensitivity to tactile and visual experience. From the grain of pinewood in a scholar’s desk to the soft paper (hanji) used for calligraphy and doors, Korean design exudes a quiet, lived-in elegance. This attention to materiality continues into the present, with contemporary artists like Lee Ufan and Do Ho Suh incorporating traditional methods and philosophies into modern, often global, contexts.

A National Art in Flux

Periods of political instability—such as the Mongol invasions, Japanese colonial rule (1910–1945), and the division of the peninsula—deeply affected Korea’s cultural output. Yet even under suppression, Korean artists continued to work, often encoding subversion into traditional forms. During the colonial era, for instance, painting and poetry served as vehicles for both resistance and self-preservation. After the Korean War, divergent paths emerged: in the North, art became a tool of the state; in the South, it fractured into modernist experimentation, abstraction, and later, conceptual art.

Today, Korean art stands at an exciting crossroads. Institutions like the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), global platforms like the Gwangju Biennale, and internationally recognized artists have brought Korean aesthetics to the forefront of global discourse. Yet the essence of Korean art—its balance of stillness and dynamism, its ethical undercurrents, and its communion with nature—remains unmistakably rooted in its millennia-old traditions.

Toward a Deeper Understanding

This introductory panorama sets the stage for a deeper, period-by-period exploration of Korea’s visual culture. From tomb murals to NFTs, Korea’s art history is not simply a sequence of objects and styles, but a living record of its people’s values, struggles, and aspirations. As we journey through each epoch, we’ll uncover how Korean artists navigated their worlds—politically, spiritually, and aesthetically—and how they crafted a legacy that continues to resonate far beyond the peninsula’s shores.

Neolithic to Bronze Age – The Foundations of Aesthetic Expression

Long before Korea’s grand temples and royal tombs took shape, the seeds of its artistic legacy were already being sown in clay, stone, and pigment. The Neolithic and Bronze Age periods—spanning roughly from 8000 BCE to 1000 BCE—are often viewed primarily through the lens of archaeology. Yet the artifacts from these eras reveal much more than the practicalities of survival: they disclose a world rich in imagination, belief, and symbolic thinking. In the hands of early Korean peoples, even the simplest tools and vessels became expressions of cosmic order, ancestral reverence, and aesthetic curiosity.

These formative centuries may seem distant and opaque, yet they are vital to understanding the evolution of Korean art. They provide the visual and spiritual foundations that would echo—sometimes subtly, sometimes overtly—throughout the millennia.

Life Along the Riverbanks: The Neolithic Era (c. 8000–1500 BCE)

The Neolithic period in Korea is characterized by a shift from nomadic hunter-gatherer societies to more settled agricultural communities. Early settlements appeared along river valleys, especially in the northeastern and central parts of the Korean peninsula. The archaeological record from this era includes pit houses, stone tools, fishing gear, and—most importantly—ceramic vessels.

Korea’s comb-pattern pottery (jeulmun togi, 줄무늬 토기) is perhaps the most iconic artifact from this time. These vessels, made by coiling clay and firing it in open pits, were decorated with incised patterns resembling fish bones, zigzags, and herringbones. The name “comb-pattern” comes from the practice of impressing lines with a toothed or comb-like implement.

But these were not mere containers. The patterns often extended over the entire surface of the vessel, suggesting an aesthetic concern that surpassed functionality. The rhythmic lines may have symbolized water, fertility, or cosmological concepts, though their precise meanings remain debated. Some scholars propose that these pots had ritual significance, used in ceremonies related to planting, hunting, or burial.

In addition to pottery, we find traces of symbolic art in the form of petroglyphs—rock carvings that offer tantalizing glimpses into the Neolithic mind. Sites like Bangudae in Ulsan feature engravings of whales, tigers, deer, and human figures. These images are often interpreted as shamanic or totemic, linking the people to the animal spirits they depended upon. Their placement near water sources further hints at ritualistic functions.

The Bronze Age (c. 1500–300 BCE): Ritual, Hierarchy, and the Emergence of Elites

By the Bronze Age, Korean society had become more stratified. Agriculture was widespread, metallurgy was advancing, and burial practices revealed a growing concern with lineage and legacy. Art in this period shifted toward objects associated with ceremony, authority, and the afterlife.

One of the most distinctive forms from this era is the “dagger culture”—so called for the prevalence of bronze daggers found in tombs, particularly in the southern regions. These weapons, especially the Korean-style daggers (as opposed to Chinese imports), are finely crafted and often accompanied by jade ornaments, mirrors, and bronze bells. While they served as symbols of martial power, they also had ritual significance, suggesting a fusion of political and spiritual roles in early elites.

Dolmens (megalithic tombs) are another defining feature of the Korean Bronze Age landscape. Korea has the highest concentration of dolmens in the world—over 35,000—and their sheer number attests to a widespread, organized burial culture. These massive stone structures, built without mortar, house burial chambers and serve as markers of status. Though largely unadorned, the labor and planning required to construct them reveal a communal investment in honoring the dead and preserving lineage.

Artifacts found within dolmens—such as bronze mirrors with intricate geometric designs, crown-like headgear, and ceramic vessels—suggest not only artistic advancement but a codified visual language associated with rank, ritual, and cosmic order. Many of these motifs—spirals, concentric circles, and triskelions—have parallels in other Eurasian Bronze Age cultures, pointing to early networks of cultural exchange or parallel symbolic developments.

Shamanism and the Seeds of Spiritual Art

While written records from these eras are absent, the material remains point to a culture steeped in shamanistic beliefs—a spiritual system that predates organized religions like Buddhism or Confucianism. Shamanism’s focus on the natural world, spirit mediation, and sacred transformation would leave a lasting imprint on Korean art for centuries to come.

We see this in the emphasis on animal forms—both in petroglyphs and in small carvings of birds or tigers—which may have served as spirit guides or totemic protectors. We see it in the careful orientation of burial sites, likely tied to geomantic beliefs (pungsu-jiri). And we see it in the ceremonial tools—bronze bells, axes, and mirrors—whose form and decoration suggest usage in trance rituals or ancestor communication.

These shamanistic elements laid the emotional and conceptual groundwork for Korean spirituality, even as Buddhism and Confucianism later overlaid new systems of thought. The sacred mountain, the guardian animal, the ritual space—these core motifs begin here, in the foggy recesses of Korea’s prehistoric past.

Artistic Legacy and Continuity

Though often overshadowed by the sophistication of later dynasties, the Neolithic and Bronze Age artifacts hold a quiet power. Their patterns, forms, and functions establish a throughline that persists in later Korean art—especially in the emphasis on natural materials, repetitive symbolism, and spiritual resonance.

The comb-pattern pottery, with its understated elegance, prefigures the minimalist aesthetic of later white porcelain. The bronze mirrors, simultaneously practical and symbolic, mirror the dual function of many Joseon-era scholar’s objects. Even the petroglyphs—with their rhythmic, carved lines—echo in the brushstrokes of later ink paintings.

These early artists—unnamed and anonymous—did not work in studios or palaces. Yet they gave form to a worldview that prized the rhythms of nature, the mystery of life and death, and the unseen threads connecting humanity to the cosmos. In doing so, they created not only objects of use but a foundation for Korean visual culture that would stretch into the 21st century.

Three Kingdoms Period – Political Rivalry and Artistic Innovation

The Three Kingdoms Period of Korea, spanning roughly six centuries from 57 BCE to 668 CE, marks a pivotal chapter in the peninsula’s artistic and political development. During this time, three rival kingdoms—Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla—competed for dominance, not only on the battlefield but in the realm of culture and visual expression. Their rivalry spurred remarkable innovation across a wide array of media: from monumental tomb murals and Buddhist sculpture to gold regalia, temple architecture, and advanced metallurgy. Each kingdom cultivated a distinct visual identity, shaped by its geography, diplomatic relationships, and internal values, laying the groundwork for many of Korea’s defining artistic traditions.

Though often eclipsed in popular imagination by later dynasties like Goryeo or Joseon, the Three Kingdoms were responsible for establishing the first uniquely Korean approaches to art and spirituality. It was an era of statecraft and sanctity, of mythic kings and cosmic murals—where art was not only a reflection of political ambition but a medium through which divine order and royal legitimacy were proclaimed.

Goguryeo: Murals of the Spirit World

The northernmost and often most militarized of the three, Goguryeo (37 BCE–668 CE) was centered in what is now North Korea and southern Manchuria. It is best remembered for its elaborate tomb murals, which remain among the most significant contributions to East Asian painting.

These murals, found in stone-chambered tombs like those at Anak and Kangso, were painted directly onto the interior walls and ceilings of elite burials. Their themes blend shamanic symbolism, courtly life, and celestial cosmology. We see vivid depictions of warriors, dancers, animals, constellations, and heavenly guardians—rendered in bold lines and flat color planes that seem to pulse with life even today.

The famous Tomb of the Dancers, for example, features a procession of women in swirling robes, their arms raised in perpetual motion, suggesting not only a funerary ritual but a celebration of the spirit’s journey. In other tombs, fierce animals like tigers and phoenixes guard the soul, while celestial diagrams map the path of transcendence. These were not decorative frescoes—they were cosmological tools meant to assist the deceased in navigating the afterlife.

Goguryeo art, influenced by both Chinese Han dynasty traditions and local shamanic practices, emphasized dynamism, movement, and spiritual protection. The use of swirling clouds, exaggerated gesture, and symbolic color anticipated later Korean approaches to expressive linework and narrative painting.

Baekje: Elegance, Internationalism, and Buddhist Synthesis

To the southwest, Baekje (18 BCE–660 CE) emerged as a refined and outward-facing kingdom with strong cultural ties to both China’s southern dynasties and early Japan. Baekje was a key player in transmitting Buddhism and associated art forms across East Asia, and its court acted as a vital hub of exchange.

Baekje’s art is often characterized by graceful proportions, sophisticated ornamentation, and an almost lyrical aesthetic. While fewer tomb murals survive from Baekje compared to Goguryeo, archaeological finds such as the incised gold earrings, gilt-bronze incense burners, and architectural remains of temples (notably Mireuksa and Jeongnimsa) reflect a courtly taste steeped in cosmopolitan elegance.

A crown jewel of Baekje Buddhist sculpture is the Gilt-Bronze Incense Burner of Baekje, unearthed in 1993. This stunning object features a round base, an ornately decorated lid topped with a dragon, and intricate scenes of musicians, animals, and mountains sculpted in openwork relief. The object is as much a spiritual statement as a technological marvel, combining Taoist, Buddhist, and indigenous imagery into a single cosmic landscape. Its influence can be seen in Japanese Buddhist art, particularly during the Asuka period.

Baekje’s Buddhist sculptures, with their gentle smiles and fluid drapery, contrast markedly with the more solemn, muscular figures of Goguryeo. The kingdom’s embrace of softness and subtlety over heroic scale would become a hallmark of Korean spiritual aesthetics in later centuries.

Silla: Splendor, Spirituality, and the Birth of Gold Artistry

Occupying the southeastern portion of the peninsula, Silla (57 BCE–935 CE) began as the least centralized of the three but eventually emerged as the most powerful, thanks to its eventual unification of the Korean peninsula in 668 CE with the aid of China’s Tang dynasty.

Silla’s early art is best known for its royal tombs and opulent regalia. Excavations at sites like Gyeongju, the ancient Silla capital, have yielded an astonishing array of treasures: gold crowns, belt ornaments, glass beads, and bronze vessels, many of which rival the splendor of any Eurasian elite culture of the time.

The Silla crowns, in particular, are dazzling. Made of hammered gold and adorned with jade gogok (comma-shaped beads), these diadems feature vertical projections that evoke antlers or tree branches, linking the sovereign with the divine and natural worlds. Scholars believe these forms reflect Siberian shamanic influence, further tying Silla to a broader Northeast Asian ritual landscape.

By the 6th century, Silla had fully adopted Buddhism, constructing monumental temples and commissioning Buddhist sculpture that rivaled the best of China. The Seokguram Grotto, completed just after the Three Kingdoms period but initiated under Silla, remains one of the great architectural and spiritual masterpieces of Korean art. Its central image—a serene granite Buddha seated in lotus position—is a testament to the synthesis of engineering, iconography, and devotion.

Silla art, particularly in its golden age, embodied both grandeur and metaphysical precision. It fused shamanic symbolism with Buddhist idealism, producing works that transcended their political origins and ventured into the universal.

Interactions, Influence, and Artistic Exchange

While rivalry defined the political landscape, the cultural borders between the Three Kingdoms were more porous. Artists, monks, and merchants frequently traveled between kingdoms—and beyond. Each kingdom maintained diplomatic and cultural exchanges with China and, in Baekje’s case, with the Japanese archipelago.

This cross-cultural exchange enriched Korean art and established Korea as a cultural bridge in East Asia. It also introduced critical technologies—such as ink-making, bronze casting, and pagoda construction—that would continue to evolve into distinctly Korean forms in later periods.

Yet the distinctions between the kingdoms remained vivid. Goguryeo’s murals captured heroic vitality; Baekje emphasized gentle refinement; Silla mastered spiritual symbolism and goldwork. Together, they form a triadic vision of early Korean aesthetics, one that prefigures many of the dualities and harmonies that would define the peninsula’s later artistic identity.

Legacy and Transition

By 668 CE, Silla had succeeded in unifying most of the Korean peninsula, ushering in a new era of political stability and cultural consolidation known as the Unified Silla period. But the innovations of the Three Kingdoms did not vanish—they were absorbed, adapted, and elevated in the centuries that followed.

The tomb murals, Buddhist sculptures, and ritual objects of this era continue to influence contemporary Korean artists and inspire global scholarship. They remind us that art is not born in peace alone; it often flowers in competition, evolves through conflict, and survives because of its spiritual resonance and material excellence.

Unified Silla and the Golden Age of Buddhist Art

The unification of the Korean Peninsula under Silla in 668 CE marked a profound turning point in the nation’s history. For the first time, a single kingdom governed the majority of the land, creating a fertile environment for cultural consolidation, religious flourishing, and artistic refinement. This era, known as Unified Silla (668–935 CE), is widely regarded as a golden age of Korean Buddhism and one of the most spiritually and artistically accomplished periods in East Asian history.

During these nearly three centuries of relative stability, Silla channeled its resources and political legitimacy into monumental artistic production—most notably in the realms of Buddhist sculpture, temple architecture, and stonework. Art became a conduit for transcendence, embodying the kingdom’s aspirations toward moral harmony, cosmic order, and spiritual illumination.

A Unified Vision: Politics, Piety, and Patronage

Unification did not simply end conflict; it redefined the role of art and religion within the state. The Silla court embraced Buddhism not merely as personal belief but as a political ideology—a force capable of legitimizing royal authority and aligning the kingdom with cosmic law.

This Buddhist statecraft is visible in the sheer scale and ambition of Silla’s temple construction and sculpture projects. Large temples such as Hwangnyongsa (the “Temple of the Imperial Dragon”) and Bulguksa (“Temple of the Buddha Land”) were designed not just as places of worship but as architectural metaphors for the Buddhist universe. Patronage came directly from the court, aristocracy, and religious institutions, creating a triangle of spiritual, political, and economic support for the arts.

Bulguksa Temple: Stone, Space, and the Pure Land

Completed in the 8th century, Bulguksa Temple in Gyeongju remains one of the most iconic achievements of Unified Silla. Though much of the original structure has been reconstructed, its foundational elements—including stone pagodas, bridges, and staircases—survive as testament to the era’s sophistication.

The temple is a masterclass in Buddhist cosmology translated into architecture. The two stone pagodas—Seokgatap (the Pagoda of Shakyamuni) and Dabotap (the Pagoda of Many Treasures)—stand side by side in symbolic balance. Seokgatap’s simplicity reflects the spiritual purity of the historical Buddha, while Dabotap, ornately carved with complex symbolism, represents the richness of the Buddha’s teachings.

Equally striking is the temple’s entrance, which features two elegant stairways—Cheongungyo and Baegungyo—symbolizing the ascent from the mundane to the sacred. Visitors move from the “world of men” into a symbolic Pure Land, a journey both literal and spiritual. Every stone, joint, and carving contributes to a visual grammar of enlightenment.

Seokguram Grotto: Sculpture as Divine Presence

Perhaps the most celebrated artistic achievement of this period is the Seokguram Grotto, completed in 774 under the supervision of Prime Minister Kim Dae-seong. Located on Mount Toham, the grotto was constructed as a synthetic shrine to the Buddha, intended to mirror the cosmic order described in Mahayana Buddhist texts.

At its heart sits a majestic granite Buddha, seated in dhyanasana (meditative pose), eyes half-lidded in serene awareness. Carved from a single piece of stone and surrounded by 39 divine attendants and bodhisattvas, the central figure radiates both monumental power and intimate calm. The dome-shaped chamber that houses him is an architectural marvel of engineering and symbolism: a microcosmic mandala reflecting the spiritual structure of the universe.

Seokguram is not merely an artwork; it is a pilgrimage site, a spiritual machine, and a sculptural manifestation of Buddhist metaphysics. UNESCO has recognized it as a World Heritage Site, and it continues to be a source of national pride and spiritual inspiration.

A New Sculptural Language: Serenity and Transcendence

Unified Silla’s sculptural style matured into something distinct from both its Chinese and Indian antecedents. The figures from this period—whether standing Bodhisattvas or seated Buddhas—are marked by graceful proportion, serene facial expressions, and naturalistic drapery that hugs the body without exaggeration.

Gone are the rigid lines of early Buddhist statuary. In their place, we find a gentle curvature in the body, a softness in the face, and an inner tranquility that speaks to a deeply internalized spirituality. A prime example is the Gilt-bronze Seated Maitreya Bodhisattva, sometimes called the “Pensive Bodhisattva,” which portrays the future Buddha lost in contemplative thought. His body is elegant and relaxed, his finger touching his cheek, his expression caught between awareness and compassion. This sculpture, now housed in the National Museum of Korea, remains one of the most beloved icons of Korean art.

This era’s focus on interiority and spiritual stillness became a signature of Korean Buddhist aesthetics, setting it apart from the more dramatic or muscular styles seen in Tang China or Nara Japan. Unified Silla artists were not interested in theatrical spectacle—they aimed instead for transcendence.

Beyond Temples: Artistic Flourishing in Everyday Life

While temple complexes and stone sculpture dominated elite patronage, the influence of Buddhist aesthetics extended into more quotidian forms of art and design. Bronze bells, such as the massive Emille Bell, demonstrate the confluence of utility and spirituality. Cast in the 8th century and standing over three meters tall, the bell features lotus petals, Sanskrit mantras, and images of heavenly beings. According to legend, the bell emits an unearthly tone reminiscent of a child’s cry—emille, meaning “mommy” in old Korean—which is said to stem from a child sacrifice during casting.

Ceramics also underwent refinement. Unified Silla potters produced gray stoneware and early forms of glazed ceramics, foreshadowing the celadon revolution of the Goryeo period. Meanwhile, painted clay figurines and decorative tiles reflected Buddhist narratives and vegetal motifs.

Literature, calligraphy, and painting—though less well-preserved—also flourished, often commissioned by monasteries or aristocrats seeking to earn karmic merit. These works further disseminated Buddhist values into the broader cultural fabric.

End of an Era, Seeds of the Next

By the 9th century, Unified Silla began to decline under the weight of aristocratic fragmentation, regional uprisings, and economic strain. In 935, it ceded control to the newly rising Goryeo Dynasty, marking the end of its three-century reign. Yet its artistic legacy did not end—it morphed.

The serenity, formal clarity, and spiritual depth of Unified Silla sculpture directly influenced Goryeo Buddhist art, particularly in the refinement of Buddhist painting and celadon ceramics. Seokguram and Bulguksa continued to serve as spiritual lodestones, surviving war, neglect, and time.

More importantly, Unified Silla established the idea of Korean art as a vehicle for enlightenment, a tradition that would echo through every subsequent period—from Goryeo’s illuminated sutras to Joseon’s Confucian ink paintings and even the conceptual installations of modern Korean artists.

Goryeo Dynasty – The Sublime Elegance of Celadon

The Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392) is widely regarded as one of the most artistically refined periods in Korean history. Its legacy rests most famously on the ethereal beauty of celadon ceramics, but this era also witnessed profound achievements in Buddhist painting, metalwork, and manuscript production. While the Unified Silla period laid the metaphysical and artistic foundations, Goryeo took those impulses and turned them into objects of astonishing technical mastery and quiet, spiritual grace.

During these five centuries, Goryeo was a highly cultured and politically ambitious kingdom. Despite facing invasions, internal power struggles, and shifting allegiances—especially with China’s Song, Liao, and later Yuan dynasties—its aristocracy cultivated an opulent court culture rooted in elegance, contemplation, and visual splendor. Art was both an expression of spiritual aspiration and an assertion of courtly taste, fusing worldliness with transcendence.

The Spirit of Celadon: A Technological and Aesthetic Triumph

Celadon, or cheongja (청자), is perhaps the Goryeo Dynasty’s most enduring contribution to world art. Characterized by its soft jade-green glaze, celadon ceramics were inspired by Chinese Song prototypes but quickly evolved into uniquely Korean forms.

The color—cool, luminous, and otherworldly—was prized for its resemblance to polished jade, which in East Asian cultures symbolized purity, nobility, and moral integrity. But Goryeo celadon went beyond mere imitation. Korean potters developed an inlay technique called sanggam, whereby designs were incised into the clay body, filled with black or white slip, and then covered with the translucent glaze. This allowed for astonishingly delicate imagery—clouds, cranes, lotuses, willows, phoenixes—to appear beneath the glassy surface like dreams suspended in water.

The most celebrated examples of celadon include maebyeong vases, with their slender necks and swelling shoulders, and incense burners shaped like animals or miniature mountains. Objects were created not only for practical use—tea bowls, wine cups, storage jars—but also for spiritual and ritualistic purposes. A famous piece, the Celadon Ewer in the Shape of a Lotus Flower, exemplifies both sculptural grace and symbolic layering. The lotus, a Buddhist emblem of enlightenment, transforms a utilitarian object into a meditative metaphor.

Even Chinese connoisseurs of the time praised Goryeo celadon. In fact, Korean celadon was exported and collected across East Asia, often surpassing the prestige of its Chinese counterparts—a rare feat in a Sinocentric cultural landscape.

Buddhist Devotion and the Visual Arts

If Unified Silla was the age of monumental Buddhist sculpture, Goryeo was the era of painterly and literary devotion. The dynasty’s elite, particularly women of the court and temple patrons, funneled enormous resources into the production of illuminated sutras, mandalas, and gilded icons.

One of the most astonishing undertakings of the period was the creation of the Tripitaka Koreana, a complete woodblock printing of the Buddhist canon carved onto over 80,000 woodblocks, completed in the 13th century and still preserved today at Haeinsa Temple. It remains the most accurate and comprehensive version of the Tripitaka in the world. This feat of textual and visual culture was as much a spiritual act as a national one, intended to protect the kingdom through the power of the Dharma.

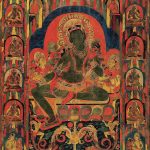

Meanwhile, Goryeo Buddhist paintings—many on silk, now held in museums in Japan, Korea, and the West—display remarkable attention to detail, cosmic grandeur, and luminous coloration. Paintings of Avalokiteshvara (Gwaneum Bosal), the Bodhisattva of Compassion, often show the deity seated on a rocky outcrop or floating amidst clouds, attended by celestial beings. These works combine ethereal composition with precise gold detailing and delicate linework, inviting meditation and visual immersion.

Despite the political dominance of Buddhism, these works were not just courtly commissions—they were devotional tools, meant to generate karmic merit and guide viewers toward enlightenment. The act of commissioning, viewing, and preserving these artworks was understood as a form of spiritual practice.

Court Culture and Decorative Arts

Outside the temples, the Goryeo aristocracy developed an opulent court culture that manifested in equally refined material goods. Goryeo was known for its lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl, gilt-bronze Buddhist ritual implements, and luxurious textiles. These were not merely items of wealth—they were signifiers of cultivated taste, often blending Buddhist motifs with courtly flourishes.

The banquet culture of the elite created a demand for elegant serving vessels, refined utensils, and display objects. Artisans competed in inventiveness, crafting both functional and purely decorative pieces that demonstrated the dynasty’s artistic ideals: elegance, harmony, and spiritual refinement.

Goryeo’s calligraphy—while less widely preserved—also played a key role in cultural life. Inspired by Tang and Song masters, Goryeo calligraphers sought a balance between disciplined form and expressive brushwork, often embedding Buddhist philosophy into the act of writing itself.

Political Upheaval and Artistic Resilience

The later Goryeo period was marked by turbulence: internal corruption, aristocratic factionalism, and increasing Mongol influence after Korea became a vassal to the Yuan dynasty in the 13th century. These pressures inevitably shaped the arts.

Celadon production, for instance, saw a decline in quality during the 14th century, with glazes becoming murkier and forms more standardized. Yet the cultural memory of the Goryeo style remained so powerful that even under the later Joseon dynasty, kilns tried to recreate its elegance—though with limited success.

Buddhism, too, came under attack as Neo-Confucianism began to rise, especially in the waning years of the dynasty. But even amid these changes, the Goryeo aesthetic persisted, refined through adversity, adapting to changing tastes while preserving its meditative core.

Legacy: The Quiet Glory of Goryeo

Today, Goryeo art is celebrated not for monumental ambition but for its quiet sophistication. In contrast to the bold expressiveness of Goguryeo murals or the monumental sculpture of Unified Silla, Goryeo’s greatness lies in detail, intimacy, and serenity. Whether it’s the soft bloom of a lotus on a celadon vase, the faint gold lines on a silk mandala, or the rhythm of brushstrokes in a sacred sutra, Goryeo art invites viewers not to marvel but to reflect.

It’s no coincidence that modern Korean artists, collectors, and institutions continue to hold this era in the highest esteem. Exhibitions of Goryeo celadon and Buddhist painting routinely draw international audiences, while contemporary potters and spiritual artists look to this period for inspiration. In the luminous green of a celadon vase or the tender expression of a painted Bodhisattva, one finds not just beauty, but a vision of a world steeped in grace and compassion.

Joseon Dynasty Part I – Confucianism and Literati Culture

With the founding of the Joseon Dynasty in 1392, Korea entered a new era defined by ideological transformation, social restructuring, and aesthetic redirection. After centuries of Buddhist dominance under Goryeo, the Joseon rulers established Neo-Confucianism as the official state ideology, fundamentally reshaping the nation’s cultural and artistic priorities. This shift did not merely affect court policy—it rippled across the entire visual landscape, replacing the opulent spiritual imagery of the past with a new emphasis on simplicity, intellectual refinement, and moral symbolism.

The early Joseon period, particularly from its foundation through the 16th century, witnessed the emergence of a distinct literati culture, modeled in part on Chinese Song dynasty traditions but deeply rooted in local Korean values. Scholars, painters, and calligraphers produced art not for decorative grandeur or divine worship, but as a form of self-cultivation, ethical reflection, and harmonious living.

From Temples to Academies: The Rise of Neo-Confucian Aesthetics

Unlike Buddhism, which focused on transcendence and salvation, Neo-Confucianism emphasized the ordering of human relationships, self-discipline, filial piety, and alignment with natural laws. Art under this framework became a tool for ethical introspection and scholarly virtue.

This transition was most clearly embodied in the rise of the “scholar-official” (seonbi) class, whose ideal combined administrative skill with artistic sensitivity and moral integrity. These men were expected to read the Confucian classics, write elegant poetry, master calligraphy, and engage in painting—not as a professional pursuit but as an expression of their cultivated inner selves.

Thus emerged the Korean version of “literati art” (muninhwa, 문인화), where simplicity was prized over technique, and personal sincerity over decorative appeal. The brush became not just a vehicle for line, but for spirit.

The Art of Ink: Landscape, Calligraphy, and Self-Cultivation

The early Joseon period saw the flourishing of ink painting as the dominant visual medium. While color painting did not vanish, the black ink wash painting—monochrome and understated—became the most esteemed form of expression among Confucian scholars.

The Korean landscape, already a source of artistic inspiration in earlier periods, took on new symbolic and introspective roles. Painters like An Gyeon (active c. 1440s) produced works such as Dream Journey to the Peach Blossom Land (1447), which combined elements of Chinese fantasy landscapes with specifically Korean scenery and poetic imagination. This painting, depicting a dream-vision of a utopian land, was not only a visual feast but a philosophical meditation on the human condition and the fleeting nature of paradise.

Other painters like Yi Sang-jwa, Yi Am, and Kim Myongguk followed, refining Korean brushwork traditions with a focus on subtle washes, spare compositions, and emotive linework. Trees bent with age, mist-shrouded mountains, and solitary pavilions all reflected the mood and morality of the artist rather than the grandeur of the natural world.

In this same spirit, calligraphy was considered the highest of the arts. Influenced by the Chinese masters but increasingly localized, Joseon calligraphy emphasized harmony of line, rhythm of stroke, and balance of void and form. The style known as chusa-che, developed later by Kim Jeong-hui, had its seeds in this early period’s insistence on ethical elegance.

To write well was to live well. The brushstroke became an act of character—a visual biography of the mind and heart.

The Scholar’s Studio: Aesthetic Minimalism and Material Intimacy

The scholar’s study, or sarangbang, became a symbolic microcosm of the Joseon literati ideal. Unlike the expansive Buddhist temples or ornate Goryeo courtly spaces, the sarangbang was spare, wooden, and orderly—often containing only a desk, bookshelves, inkstone, and calligraphy scrolls.

Artworks created for or within these spaces reflect their environment. Inkstone boxes, ceramic brush holders, paperweights, and folding screens bore subtle designs: pine trees, bamboo, plum blossoms—plants known as the “Four Gentlemen” (sagunja) for their moral symbolism (resilience, uprightness, purity, perseverance). These motifs not only decorated, but instructed.

Ceramics, too, followed the principle of aesthetic humility. The early Joseon period produced white porcelain (baekja) of remarkable clarity and restraint. These vessels—bowls, jars, bottles—were minimally decorated, if at all, and favored pure forms over elaborate ornament. When decoration did occur, it was often limited to a single brush-drawn bamboo shoot or a softly inscribed poetic line.

In this way, Joseon whiteware became the ceramic embodiment of Confucian virtue: clean, modest, strong in form but quiet in presence.

Women, Art, and Court Life

While much of early Joseon art was produced or commissioned by male scholar-officials, women—especially those within the royal court—played a significant, if often overlooked, role in cultural production. Royal women engaged in embroidery, poetry, and lacquerwork, and they frequently commissioned Buddhist artworks in private devotion, even as official state ideology grew increasingly Confucian.

Indeed, the court maintained complex rituals and aesthetic programs that often incorporated older traditions. The Joseon royal portraits of kings and queens—painted with exquisite realism and reverence—served not only as records but as ritual icons. These works, rendered in mineral pigments on silk, preserved elements of Goryeo ceremonial art while adapting them to Joseon hierarchies.

At the same time, court music, dance, and ceremonial design remained crucial outlets for creative expression, blending Confucian order with artistic flourish. Here, the rigid and the poetic coexisted—order beautified by discipline.

Artistic Nationalism and Identity

Although much of Joseon’s early visual culture was modeled on Chinese ideals, the kingdom increasingly asserted its distinct cultural identity through regional motifs, local subject matter, and uniquely Korean forms of visual rhythm. The “true-view” (jingyeong) landscape painting style, which would fully flower in the 18th century, had its roots in the early Joseon impulse to depict Korea’s own mountains, rivers, and architecture.

This nascent nationalism was also evident in the creation of Hangul, the Korean phonetic alphabet, in the mid-15th century under King Sejong. While not a visual art in itself, Hangul dramatically expanded literary and cultural expression, eventually influencing typography, graphic design, and popular art forms in later centuries.

The visual arts in early Joseon were thus quietly revolutionary: rejecting overt grandeur, they embraced a new language of visual modesty, intellectual reflection, and spiritual ethics. In doing so, they laid the groundwork for centuries of artistic innovation rooted not in spectacle, but in sincerity.

Joseon Dynasty Part II – Folk Art, Genre Painting, and Daily Life

As the Joseon Dynasty entered its later phase—from the 17th through the 19th centuries—Korean art began to reflect not just the ideals of the Confucian elite but the rhythms and realities of everyday life. While literati ink painting and white porcelain remained prestigious, a more diverse, colorful, and often humorous body of work flourished alongside them: folk painting (minhwa), genre scenes, portraiture, and popular decorative art. These works celebrated domestic virtues, festivals, superstitions, humor, and national identity in ways that were often more accessible—and more emotionally vivid—than their austere predecessors.

This period saw the rise of a visually democratic ethos, one in which kings, scholars, merchants, farmers, and commoners all found themselves represented in art. Stylistically, this era’s works are marked by bold linework, bright color, narrative clarity, and symbolic density—qualities that remain influential in contemporary Korean art.

Minhwa: The People’s Paintings

The term minhwa (민화), meaning “folk painting,” refers to a wide variety of anonymous, non-court, and non-literati paintings that circulated in homes, shrines, and public spaces during the late Joseon period. These works were created not by professional artists in the Dohwaseo (court painting academy) but by artisans and traveling painters who often worked without formal training or elite patronage.

Minhwa were deeply interwoven with daily life and seasonal cycles. They were used to celebrate births, ward off evil spirits, bless a marriage, ensure a bountiful harvest, or simply decorate one’s home with symbols of prosperity and protection. Their subjects included:

- Hwajodo (flower-and-bird paintings): signifying harmony and natural balance.

- Buchae-do (folding screen of books and scholarly objects): often seen in homes and offices as aspirational markers of education and success.

- Sansuhwa (mountain and water scenes): simplified landscapes with spiritual overtones.

- Horangi and ggach’i (tiger and magpie paintings): humorous and satirical compositions symbolizing authority and its watchers.

- Chilseong-do (Seven Stars painting): reflecting shamanistic beliefs and astrological protection.

These paintings, while simple in technique compared to literati art, are rich in symbolism and narrative warmth. A child grasping a peach in a hwajodo scene may symbolize longevity; a carp swimming upstream alludes to academic success. Color was used exuberantly—deep reds, cobalt blues, and lush greens—evoking a sense of festive vitality.

Importantly, minhwa challenged the top-down nature of official art. It gave voice to everyday aspirations, fears, and joys, often blending Buddhist, Confucian, Taoist, and shamanic elements without concern for orthodoxy. Though long dismissed by art historians, minhwa is now recognized as a vital expression of Korean cultural identity.

Genre Painting (Pungsokhwa): Capturing the Human Drama

Another major development in late Joseon art was the rise of genre painting, known as pungsokhwa (풍속화). These works portrayed the daily lives of ordinary Koreans with remarkable immediacy and empathy—farming, market scenes, schoolboys playing games, washerwomen by the river, or noblemen drinking in garden pavilions.

The most celebrated master of this style is Kim Hong-do (Danwon, 1745–c.1806). A member of the court painting academy, Kim broke from formal portraiture and landscapes to create vividly observed scenes of peasants, scholars, wrestlers, and laborers. His brushwork—at once loose and precise—captured gestures, expressions, and group dynamics with theatrical flair and psychological nuance.

His contemporary, Shin Yun-bok (Hyewon), explored a more erotic and satirical side of genre painting. His works often feature elegant courtesans, clandestine lovers, and courtship rituals with subtle humor and a keen eye for detail. While Kim Hong-do focused on public life, Shin Yun-bok portrayed the private and emotional undercurrents of Joseon society.

Together, these artists brought narrative and realism into Korean painting in ways not previously seen. Their works defy the stereotype of Joseon art as uniformly austere—they are lively, critical, and deeply humanistic.

Portraiture: Loyalty, Lineage, and the Human Face

Portraiture also took on new importance during the late Joseon era. While royal and official portraits had always existed, the increased emphasis on Confucian ancestor worship elevated the status of painted likenesses. Portraits of scholars, officials, and patriarchs were commissioned not for vanity but for ritual veneration and moral instruction.

These works are noted for their psychological realism and meticulous technique. Artists paid close attention to facial features, beards, robes, and posture, using fine brushwork and careful shading. The goal was to convey both outer likeness and inner virtue—a visual biography of character.

Portraits were typically enshrined in ancestral shrines, viewed during memorial rites and ceremonies. Over time, a visual canon developed, with stylized formats and compositional rules that linked individual identity to lineage and social order.

Decorative and Functional Arts: Everyday Aesthetics

Beyond painting, the late Joseon period saw the flourishing of decorative arts that merged function with beauty. This included:

- Painted folding screens (byeongpung) with calligraphy, landscapes, or floral motifs, often used in court and household settings.

- Lacquerware with inlaid mother-of-pearl, adorning boxes, trays, and writing desks.

- Textile arts, such as bojagi (wrapping cloths), which combined abstract design with practical use.

- Ceramics, particularly buncheong ware (a gray-green slipware) and Joseon white porcelain, which remained popular for their rustic charm and Confucian clarity.

These everyday objects reflected a uniquely Korean aesthetic sensibility: one that valued asymmetry, tactility, and quiet elegance. Whether a spoon case or a brush rest, objects were crafted to please both the hand and the eye, reinforcing the idea that beauty and virtue belonged in daily life.

The Rise of National Sentiment

The later Joseon period also coincided with growing intellectual and national awareness. Scholars began to advocate “silhak” (practical learning), encouraging attention to Korea’s own geography, economy, and culture rather than slavish imitation of Chinese models.

This nationalist impulse subtly influenced the visual arts. Landscapes depicted real Korean scenery rather than imagined Chinese mountains. Bookshelves in folding screens contained Korean texts. Clothing, faces, and architecture were rendered with local realism, asserting the value of Korean life and experience.

Even folk painting and genre scenes began to serve a larger cultural role, preserving social customs, dress, and rituals in the face of increasing foreign influence and impending modernity.

Court Painters and the Academy – The Role of the Dohwaseo

In the highly structured society of Joseon Korea, art was not only the domain of individual expression or spiritual aspiration—it was also a matter of statecraft. At the heart of this institutional framework stood the Dohwaseo (도화서), the official royal painting academy. For over five centuries, the Dohwaseo was responsible for producing the visual materials that maintained the political, ceremonial, and ideological order of the kingdom. From royal portraits and diplomatic gifts to ritual manuals and landscape scrolls, court painters shaped the public face of Joseon governance—and in the process, left behind a sophisticated and often underappreciated artistic legacy.

The story of the Dohwaseo reveals how centralized artistic production can both constrain and elevate creativity, how artistic labor was organized within a Confucian state, and how individual brilliance could still emerge within rigid hierarchies.

The Institutional Core of Joseon Art

The Dohwaseo—often translated as the Office of Painting—was established shortly after the founding of the Joseon Dynasty in 1392. It served multiple key functions:

- Training and maintaining a corps of professional painters for court service

- Producing artwork for royal use, including portraits, ceremonial illustrations, decorative paintings, and state-sponsored projects

- Managing the iconography and stylistic consistency of official artworks

Unlike the scholar-artists of the literati class, court painters (hwawon, 화원) were often from lower social backgrounds or the chungin (middle class). Despite their talent and prestige within the academy, they did not enjoy the same status as the yangban elite. Their work was not a means of self-expression, but a civic duty—a craft honed in service of the monarch and Confucian ideals.

The Dohwaseo had its own bureaucratic structure, with ranks, promotion systems, and official posts. Painters were tested through state examinations (gwageo) in drawing and calligraphy, and the most skilled were assigned to high-profile tasks, including the rare honor of painting the king.

Art in the Service of the State

Much of the academy’s output was functional: banners for court ceremonies, diagrams for royal processions, official maps, and painted screens for palaces and government buildings. These works were often collaborative and anonymous, reflecting collective authority rather than individual style.

However, some genres became highly specialized and artistically ambitious within this system:

- Royal Portraiture (Eojin, 어진): Kings and queens were painted in formal, highly controlled styles, following iconographic rules that emphasized moral virtue and dynastic continuity. These portraits were used in ancestor rites and often displayed in shrines.

- Banquet and Celebration Paintings (Gyehoedo, 계회도): Depicting government officials at feasts or scholarly gatherings, these works served as both documentation and reward, reinforcing social cohesion.

- Documentary Paintings (Uigwe, 의궤): Illustrated manuals recording royal rituals, weddings, and funerals. These combined precise illustration with calligraphic annotation and are now invaluable records of Joseon court life.

- Painted Screens: Used as backdrops in formal settings, screens could feature landscapes, Confucian texts, auspicious symbols, or depictions of idealized scholar’s objects.

Because of the academy’s role in preserving ceremonial and ideological order, much of this work was highly codified—rigid in composition, symbolically dense, and designed to reinforce orthodoxy. Yet within those constraints, painters often developed highly refined technical skills and distinctive aesthetic sensibilities.

Masters Within the System

While the Dohwaseo was largely a collective institution, certain artists rose to prominence and left a distinct mark on Korean art. Among them:

- Kim Hong-do (Danwon): Although best known for his genre scenes, Kim also served as a court painter and produced significant works in landscape and Confucian imagery. His dual career exemplifies the tension—and synergy—between official art and personal vision.

- Jang Seung-eop (Owon): A late Joseon painter of humble origins who rose to fame within the court, Jang mastered multiple genres—landscape, bird-and-flower, figure painting—and was known for his expressive brushwork and versatility.

- Jeong Seon (Gyeomjae): Though not a court painter in the strict sense, Jeong’s influence on landscape painting (particularly the “true-view” style) impacted the Dohwaseo’s later approach to Korean scenery.

These artists navigated the limitations of the system while pushing its aesthetic boundaries, proving that institutional art need not be soulless or static.

Education, Transmission, and Technique

The Dohwaseo also functioned as an educational center, training young painters in brush technique, ink control, color mixing, and composition. Students copied models and past works, learning to reproduce standard styles before developing their own interpretations. This ensured stylistic consistency across generations and a shared visual language for state rituals.

The materials and techniques favored in the academy reflected the prevailing tastes of the court: ink and mineral pigments on silk or paper, use of standardized motifs (clouds, pine trees, lotus blossoms), and meticulous linework.

However, late Joseon court painters also absorbed foreign influences—particularly from China’s Qing dynasty and Japanese painting—leading to subtle stylistic evolutions. By the 18th and 19th centuries, some works from the academy display softer outlines, richer coloration, and looser brush handling.

The Decline and Legacy of the Dohwaseo

As the Joseon Dynasty weakened in the late 19th century under foreign pressure and internal decline, the Dohwaseo lost its central place in court life. The modernizing reforms of the Gabo Reform (1894) and the eventual annexation of Korea by Japan in 1910 led to the abolition of the academy and the fragmentation of state-sponsored art.

Yet its legacy endured:

- The academy preserved and codified centuries of Korean visual culture, passing down techniques and iconography still studied today.

- Many genre-defining artworks—from royal portraits to decorative screens—came directly from its studios.

- The Dohwaseo helped establish a national artistic identity, grounded in Confucian ethics, technical precision, and symbolic clarity.

In contemporary Korea, artists and historians look back to the Dohwaseo as both a symbol of lost heritage and a model for disciplined artistry. Its blend of structure and creativity, obligation and vision, reflects a deeper truth about Joseon society: that even within the tightest social constraints, the human drive to create—and to leave a mark—found a way to flourish.

Art Under Colonial Rule (1910–1945): Suppression, Adaptation, and Resistance

The annexation of Korea by Japan in 1910 ushered in one of the darkest chapters in Korean history. For thirty-five years, the Korean Peninsula was subjected to Japanese colonial rule, marked by political repression, cultural erasure, and economic exploitation. In the visual arts, this period was one of profound tension. Korean artists were caught between colonial suppression, the allure (or imposition) of modern Western styles, and the desire to preserve or reclaim national identity. Despite these constraints, the period also witnessed remarkable innovation as Korean artists negotiated new visual languages—sometimes through adaptation, sometimes through resistance, and often through deeply personal reinvention.

Colonialism fractured Korean art, but it also catalyzed it. The visual arts of this era—complex, hybrid, and sometimes contradictory—offer a powerful window into a culture struggling to survive, speak, and evolve under occupation.

Cultural Suppression and the Politics of Art

From the outset, the Japanese colonial administration sought to suppress Korean cultural autonomy. Korean language and history were marginalized or erased from curricula, traditional institutions were dismantled, and national symbols were co-opted or banned. Art, as both a form of expression and identity, became a highly politicized terrain.

Traditional Joseon arts—ink painting, folk art, Confucian portraiture—were increasingly viewed by Japanese officials as backward or provincial. In their place, the Japanese colonial government promoted modernization through Japanization, introducing Western-style art education (via Tokyo’s Imperial Art School and similar institutions) while filtering Korean cultural expression through a Japanese lens.

Korean artists were encouraged—or pressured—to participate in colonial art exhibitions like the Joseon Art Exhibition (Joseon Misul Jeonramhoe, 1922–1944), which promoted academic painting styles aligned with Japanese aesthetics. This systematized cultural hegemony, shaping what kinds of art could be made, exhibited, and rewarded.

The Rise of Western-Style Painting (Seohwa)

One of the major shifts during the colonial period was the rise of Western-style oil painting, or seohwa (서화). Taught in colonial schools and academies, seohwa offered Korean artists a new visual language—perspective, chiaroscuro, realism, and the human figure—distinct from traditional ink painting.

Many young artists trained in Japan or studied under Japanese mentors. Some of the notable figures include:

- Ko Hui-dong (1886–1965): Often considered the first Korean painter to adopt oil painting, Ko studied in Tokyo and initially embraced Western techniques before returning to traditional styles later in life.

- Kim Eun-ho (1892–1979): Known for his portraits of women and historical subjects, Kim’s work blended Japanese academic realism with Korean themes. His depiction of court women and Confucian scholars earned him official acclaim—but also criticism for accommodating colonial taste.

- Lee Jung-seop (1916–1956): Though active slightly later, Lee’s work bridges this era and post-liberation. He is remembered for his expressive line drawings and paintings reflecting trauma, longing, and national identity.

While many of these artists produced work within colonial frameworks, they also used Western styles to explore themes of Korean life, memory, and identity, creating a hybrid form that both conformed to and questioned the norms of empire.

Ink Painting and Traditional Forms: Preservation or Adaptation?

Other artists resisted Westernization by remaining within the ink painting tradition—sumukhwa—but even this path was fraught. Artists like Chang Woo-soung and Byeon Gwansik adapted Chinese literati painting techniques to Korean subjects, maintaining Confucian ideals of modesty, nature, and ethical self-cultivation.

However, even traditional styles were subtly transformed. Exposure to Japanese nanga (Southern School painting) and Western composition led to new formats, broader brush techniques, and narrative inflections. The question for many artists became not just how to paint, but what painting meant in a colonized culture.

Should ink painting serve as cultural resistance, preserving Korean aesthetics against foreign influence? Or could it evolve, incorporating new ideas without losing its soul? These tensions defined much of the work from this era.

Visual Resistance and Symbolic Nationalism

While overt political dissent was often censored or punished, many artists coded resistance into their works. One common strategy was to depict Korean landscapes—familiar mountains, rivers, village scenes—as symbols of enduring identity. Painters like No Su-hyeon and O Ji-ho created quiet, contemplative views of the Korean countryside, imbuing them with emotional weight and subtle defiance.

Others explored themes of folk life, motherhood, hardship, and myth, reclaiming Korean culture through iconography rather than polemic. In craft and folk traditions, the continued use of minhwa, bojagi, and calligraphy became acts of cultural continuity.

Later in the colonial period, some artists began to experiment with expressionism, abstraction, and surrealism, drawing on global avant-garde movements to express alienation, fragmentation, and suppressed desire. These works—often small in scale and hidden from public view—functioned as personal acts of survival and psychological resistance.

Education and the Shaping of Future Movements

The colonial art education system—despite its imperial framework—produced a generation of technically skilled Korean artists. Many of these artists would go on to shape post-liberation modernism, bringing their training into new political and cultural contexts after 1945.

This period also laid the groundwork for Korean art criticism, publishing, and collecting, as artists, writers, and intellectuals debated the meaning of tradition, modernity, and nationhood under occupation.

Ironically, even Japanese efforts to formalize art through exhibitions and institutions helped infrastructure to emerge that would later serve independent Korean art. Museums, journals, and academies founded in this period were often repurposed or reclaimed after liberation.

Toward Liberation: Fragmentation and Endurance

As Korea approached liberation in 1945, its artistic community was deeply fragmented. Some artists had aligned with the colonial regime, others had resisted in secret, and many had simply tried to survive. Yet across this spectrum, a common thread emerged: the search for a visual language that could speak to Korean experience, even under censorship.

The end of Japanese rule did not bring immediate clarity. In fact, the post-liberation era would plunge Korean art into further division, as ideological rifts between North and South, tradition and modernity, nationalism and internationalism continued to fracture the field.

But the art of the colonial period endures as a testament to resilience. These works—often modest, conflicted, or ambiguous—are valuable not only for their aesthetic qualities but for their role in bearing witness. They reveal how art adapts, transforms, and endures in the face of coercion.

Modernization and Division – Art in Post-Liberation Korea (1945–1960s)

The liberation of Korea from Japanese colonial rule in August 1945 marked a seismic moment in national history—and in its art. But what might have been a new beginning quickly turned into a complex and harrowing era of ideological struggle, civil war, and national division. For Korean artists, the post-liberation years were not a simple return to tradition or an unproblematic embrace of modernity. Rather, they constituted a period of radical realignment, in which artists had to reinvent their roles, affiliations, and visual languages amid a fractured cultural landscape.

Between 1945 and the early 1960s, Korean art split along multiple axes: North versus South, tradition versus Western modernism, collective ideology versus personal expression. Each region developed distinct state-sponsored art systems, yet both sides also produced works that transcended propaganda and ventured into the experimental, the spiritual, and the deeply human.

This was a period of dislocation—but also of bold beginnings. The post-liberation decades laid the groundwork for the avant-garde, the institutionalization of modern Korean art, and the long, fraught search for identity in a divided nation.

Liberation and the Vacuum of Cultural Authority

In the immediate aftermath of liberation, Korean artists were left in a power vacuum. The Japanese colonial structures that had governed art education, exhibition, and publication were dismantled. The Korean peninsula was divided along the 38th parallel, with the North under Soviet influence and the South under American occupation. Political institutions were in flux, and so were cultural ones.

Artists responded in varied ways:

- Some turned to traditional forms—ink painting, calligraphy, folk motifs—as a way to reclaim national heritage.

- Others embraced Western modernist styles, including abstraction, cubism, and expressionism, as symbols of a break with the past.

- Many were unsure which direction to take, experimenting across genres, formats, and ideologies in search of a new voice.

Art societies and collectives proliferated in the South: the National Art Exhibition (Gukjeon) resumed under new management, and groups such as the Joseon Art Alliance, Modern Art Association, and New Realism Group emerged to champion different visions of Korean modernity.

North Korea: Socialist Realism and the Art of the State

In the North, under Kim Il-sung’s Soviet-backed regime, the state quickly established a centralized art apparatus modeled on Soviet Socialist Realism. Art became a tool of political ideology, with clear aesthetic mandates: glorify the working class, depict revolutionary struggle, and elevate the image of the leader.

The Mansudae Art Studio, established in 1959, became the heart of North Korean visual culture. Thousands of artists worked under state supervision to produce murals, propaganda posters, oil paintings, and monumental sculptures.

Key characteristics of Northern art during this period included:

- Heroic realism: Depictions of laborers, soldiers, and peasants in idealized, dynamic poses.

- Iconography of struggle: Emphasis on anti-Japanese resistance and national independence.

- Leader worship: Early visual mythology around Kim Il-sung, later expanded to include his family.

Despite the rigidity of these themes, the North developed a sophisticated infrastructure for artistic education and production. Artists were state-employed, trained at the Pyongyang University of Fine Arts, and given housing and resources in exchange for ideological loyalty.

Today, this system remains largely intact, making North Korea one of the most visually consistent (and politically controlled) art cultures in the world.

South Korea: Turmoil and the Search for Artistic Autonomy

In contrast, South Korean art after 1945 unfolded in a chaotic and pluralistic environment. The American military presence introduced new materials, media, and concepts, including oil painting, photography, and abstract expressionism. At the same time, civil unrest, the Korean War (1950–1953), and authoritarian leadership under Syngman Rhee meant that art was never far from politics.

Many Southern artists struggled to define what Korean modern art should be:

- Should it be realist, reflecting the trauma of war and displacement?

- Should it be abstract, aligning with international avant-garde movements and Western modernism?

- Should it return to tradition, reasserting cultural continuity amid political rupture?

Artists like Park No-soo and Kim Ki-chang continued the ink painting tradition but infused it with modernist sensibilities—brushstrokes that broke from literati decorum, compositions that hinted at abstraction. Others, such as Lee Jung-seop, used oil paint to portray scenes of family separation and human suffering in an expressionist style all his own.

The war had a profound impact on artistic themes. Refugee life, ruined cities, and emotional loss became frequent subjects. Yet even amid trauma, artists sought formal innovation, experimenting with printmaking, collage, and new materials.

Formation of Modern Art Institutions

Despite the turbulence, the South began to build artistic infrastructure in the 1950s and ’60s:

- The National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) was founded in 1969 (with earlier roots in 1950s exhibition culture).

- Art schools like Hongik University became training grounds for a new generation of modernists.

- Government-sponsored exhibitions such as the National Art Exhibition and private galleries helped cultivate both academic and experimental work.

South Korea’s connection to the West—via the U.S., Europe, and Japan—allowed Korean artists to engage with global art movements, though often through localized lenses. Abstract art, surrealism, and modern design found fertile ground, but were frequently tempered by traditional materials, themes, or philosophical ideas.

Personal Voices Amid Political Rupture

In both Koreas, individual artists had to navigate ideological minefields. Many had worked under the Japanese regime, raising questions of collaboration. Others were imprisoned, exiled, or silenced for political beliefs.

Yet many artists persisted, creating works that spoke to the human condition amid political dogma. Whether in a realist depiction of a refugee mother, an abstract meditation on loss, or a quietly rendered ink wash of a Korean mountain, these works gave voice to grief, longing, and the search for meaning.

Perhaps most movingly, the post-liberation period gave rise to a generation of displaced artists, caught between North and South, tradition and modernity. Their works do not offer answers—they pose questions, embody fractures, and bear witness to a Korea still struggling to find itself.

Contemporary Korean Art – Global Voices, Local Roots

Since the late 20th century, Korean contemporary art has emerged as one of the most dynamic and globally resonant movements in the international art world. From museum retrospectives in Paris and New York to biennales in Gwangju and Venice, Korean artists have gained critical acclaim for their conceptual rigor, emotional depth, and ability to merge tradition with innovation. Yet beneath this international success lies a persistent dialogue with Korea’s complex past: colonization, war, rapid modernization, and the tensions between individual agency and collective memory.

Contemporary Korean art is not defined by a single medium, style, or ideology. Rather, it is a constellation of practices—conceptual installation, video art, photography, sculpture, digital media, performance, and experimental painting—bound by an acute awareness of history, space, and identity.

Post-Minimalism and the Legacy of Dansaekhwa

Any discussion of contemporary Korean art must reckon with Dansaekhwa (단색화), or “monochrome painting,” a movement that emerged in the 1970s as a uniquely Korean response to both Western minimalism and local artistic philosophy. Dansaekhwa artists created large-scale, often monochromatic canvases using repetitive, meditative techniques—scraping, rubbing, layering pigment.

Key figures include:

- Lee Ufan, whose “From Line” and “From Point” series emphasized process over image, influenced by Japanese Mono-ha and Korean Daoist sensibilities.

- Park Seo-bo, whose “Ecriture” series involved repetitive pencil strokes across hanji paper mounted on canvas—an act of material ritual.

- Yun Hyong-keun, who applied umber and blue-black pigments in vertical columns, referencing Buddhist stillness and Korean ink traditions.

While these works initially received little attention abroad, they gained international recognition starting in the early 2000s, particularly through major exhibitions in Europe and the U.S. Critics now see Dansaekhwa not merely as a regional variant of minimalism, but as a profound fusion of spiritual philosophy, material engagement, and aesthetic discipline.

Conceptual and Political Art in a Democratizing Korea

Following decades of military rule, Korea entered a period of democratization in the 1980s and ’90s. This opened new space for critical, conceptual, and politically engaged art, especially among younger generations reacting against both tradition and authoritarianism.

Artists in this period often used installation, photography, and performance to critique state violence, gender norms, capitalist consumerism, and the lingering scars of war. The body, in particular, became a key site of resistance and transformation.

Notable figures include:

- Kimsooja, whose performances and installations explore themes of migration, labor, and global nomadism. Her signature work, A Needle Woman, features the artist standing motionless in crowded streets around the world, turning passive observation into quiet protest.

- Do Ho Suh, who creates translucent fabric reconstructions of homes, hallways, and architectural memories. His work speaks to themes of displacement, identity, and the domestic, reflecting his own life between Seoul and New York.

- Lee Bul, known for her futuristic sculptures and feminist interventions. Her early body-based performances challenged gender norms and later evolved into visionary installations mixing cybernetic forms, utopian architecture, and trauma narratives.

These artists brought Korean contemporary art into the global discourse, not as exotic or derivative, but as philosophically and politically urgent.

Technology, Urbanism, and the Global Stage

As Korea became one of the most technologically advanced nations in the world, its artists began to explore the digital, the virtual, and the posthuman. Seoul’s high-speed connectivity, dense urban fabric, and hybrid pop culture provided fertile ground for new modes of expression.

Artists such as:

- Yang Hae-gue, who merges sculpture, sound, and conceptual structure to examine bureaucracy, history, and emotional systems.

- Jeong Geum-hyung, whose uncanny performances with robots and prosthetic objects interrogate intimacy, surveillance, and embodiment.

- Choi Jeong-hwa, whose large-scale installations using plastic, consumer goods, and recycled materials blend kitsch aesthetics with pop Buddhist exuberance.

In parallel, platforms like the Gwangju Biennale (founded in 1995) and institutions such as the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) in Seoul have helped position Korean art on the world stage, curating exhibitions that challenge Eurocentric narratives and highlight Asia’s multiplicity.

Korean artists now regularly feature at Documenta, the Venice Biennale, Frieze, and Art Basel, and are collected by major institutions including MoMA, the Tate, and Centre Pompidou.

Memory, Trauma, and Historical Reckoning

One of the persistent undercurrents of Korean contemporary art is the effort to reckon with historical trauma. Whether through personal memory or collective history, many works grapple with the enduring legacies of:

- Colonial occupation

- The Korean War

- State repression under Park Chung-hee and Chun Doo-hwan

- The Gwangju Uprising (1980)

Artists such as Park Chan-kyong and Minouk Lim use video, text, and installation to probe memory, media, and myth. Their work destabilizes dominant narratives and surfaces the ghosts of unspoken pasts.

This strand of Korean art is not nostalgic—it is forensic, poetic, and insistently political. It seeks not to reconcile but to hold space for absence and contradiction.

Diaspora, Hybrid Identity, and the Korean Wave

Finally, contemporary Korean art is shaped by its global diaspora and the broader phenomenon of Hallyu, or the Korean Wave. As Korean culture—film, music, design—has gained global popularity, so too has interest in diasporic and hybrid identities.

Artists like:

- Nam June Paik, widely regarded as the father of video art, whose cross-cultural, techno-shamanistic work spanned Korea, Germany, and the U.S.

- Haegue Yang, whose mixed-heritage installations engage language, abstraction, and dislocation.

- Anicka Yi, a Korean-American artist who works with bacteria, scent, and AI to challenge boundaries between nature, science, and femininity.

These artists complicate what it means to be “Korean” in the 21st century. Their works traverse borders—national, conceptual, biological—and reflect the fluidity of contemporary identity in an age of migration, climate crisis, and digital transformation.

Themes, Symbols, and Techniques Unique to Korean Art

Across its long and diverse history, Korean art has developed a visual language all its own—one grounded in subtle emotional depth, spiritual resonance, and a keen sensitivity to the natural world. While individual periods, dynasties, and movements have introduced varying styles and influences, certain core themes, symbols, and techniques recur with remarkable consistency. These elements form the connective tissue of Korea’s artistic identity, creating works that may differ in medium or purpose but share a distinctive inner rhythm.

Unlike the overt monumentality often associated with Chinese imperial art or the stylized theatricality of Japanese aesthetics, Korean art has long been characterized by an ethos of restraint, sincerity, and balance—qualities that can be traced back to ancient pottery and continue through to contemporary installations.

Aesthetic Philosophy: Humility, Naturalness, and Emptiness

Korean art values what might be called poetic modesty. Rooted in Confucian ethics, Buddhist metaphysics, and indigenous shamanic beliefs, Korean aesthetics prize not excess but elegant understatement.

Key concepts include: