Tonalism was a revolutionary art movement that emerged in the United States during the late 19th century, bringing a new, atmospheric approach to landscape painting. Unlike the bright, energetic brushstrokes of Impressionism, Tonalist artists embraced soft, muted colors and subtle gradations of tone to create poetic, dreamlike scenes. Their paintings often depicted quiet landscapes at dawn, dusk, or under moonlight, evoking a sense of mystery and contemplation. Though the movement faded in popularity by the early 20th century, its influence continues to be felt in modern landscape painting and photography.

The movement was deeply inspired by European art, particularly the Barbizon School of France, and philosophical ideas that emphasized a spiritual connection to nature. James McNeill Whistler and George Inness became leading figures in the style, helping to define its core aesthetic principles. These artists rejected rigid realism in favor of evocative mood and atmosphere, using soft edges and a limited color palette to suggest rather than describe their subjects. This approach created a distinctive, meditative quality that set Tonalism apart from other movements of the time.

At its height, Tonalism dominated American landscape painting, influencing countless artists in New York and beyond. As new styles like Impressionism and Modernism gained prominence in the early 20th century, Tonalism gradually declined, though many artists continued to work in its style. Today, the movement is experiencing renewed appreciation among collectors, scholars, and contemporary painters who value its quiet beauty. This article explores the origins, defining characteristics, major artists, decline, and lasting impact of Tonalism, providing a comprehensive look at one of America’s most poetic artistic movements.

The Origins and Influences of Tonalism

Tonalism developed in the 1870s and 1880s, largely as a response to the artistic trends of the time. Many American painters had been exposed to European art movements, particularly the Barbizon School, which emphasized naturalistic yet emotionally resonant depictions of the landscape. Artists like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Théodore Rousseau painted rural scenes with a focus on atmosphere and mood rather than strict detail. American painters took inspiration from this approach but refined it further, using even softer color transitions and a more intimate, contemplative style.

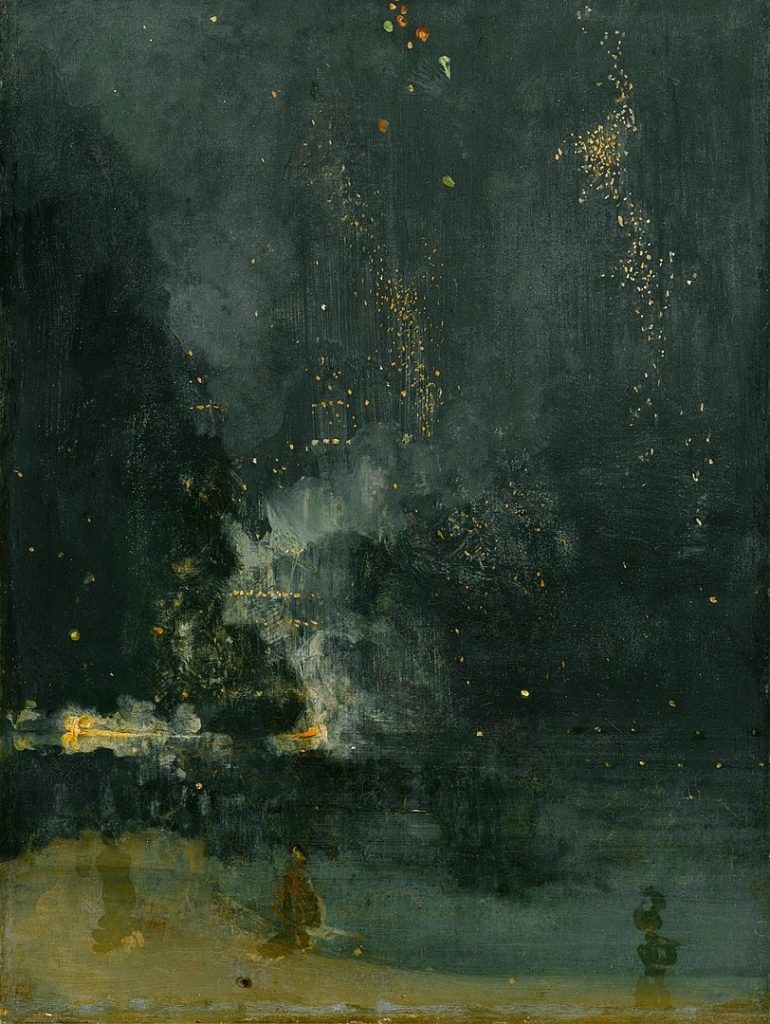

One of the most important early influences on Tonalism was James McNeill Whistler, an American artist who spent much of his career in Europe. His famous series of Nocturnes, painted in the 1860s and 1870s, featured misty, twilight scenes rendered in limited color palettes. Whistler believed that paintings should function like music, with harmonious arrangements of tone rather than detailed realism. His emphasis on art for art’s sake and his rejection of narrative storytelling were key principles that would define the Tonalist movement.

Another major influence on Tonalism was Transcendentalist philosophy, particularly the writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. These thinkers championed the idea that nature was a reflection of the divine and that human beings could attain spiritual insight through contemplation of the natural world. Many Tonalist artists, particularly George Inness, were deeply influenced by these ideas, seeking to create paintings that conveyed a sense of the unseen, the mystical, and the eternal.

By the late 1880s, Tonalism had become a dominant movement in American landscape painting. Many of its leading artists were based in New York and Boston, where they exhibited their works in major galleries. The movement flourished alongside American Impressionism, though the two styles had distinct differences. While Impressionism focused on the fleeting effects of light and color, Tonalism prioritized a sense of timelessness and introspection, making it a unique and deeply expressive approach to painting.

The Defining Characteristics of Tonalist Art

Tonalist paintings are defined by their limited color palette and soft, atmospheric compositions, which create an overall sense of mood rather than focusing on precise detail. Unlike the bold, vibrant hues of Impressionist paintings, Tonalist works use a more restrained approach, often dominated by grays, browns, and deep blues. These subtle tones allow for gentle transitions between light and shadow, giving the paintings a dreamy, meditative quality. This careful control of tone is what gives the movement its name.

Another key characteristic of Tonalist art is its focus on mood rather than realism. Instead of painting landscapes as they appeared in sharp detail, Tonalists sought to capture the emotional essence of a scene. Many Tonalist paintings depict misty mornings, twilight hours, or moonlit landscapes, where the atmosphere is more important than the individual elements within the scene. The goal was not to document nature but to evoke a feeling of tranquility, melancholy, or mystery.

The techniques used by Tonalist artists also contributed to the movement’s distinct look. Many painters used soft, blended brushstrokes to create seamless transitions between shapes and colors. Outlines were often blurred or eliminated entirely, allowing forms to merge naturally into one another. This technique created a sense of depth and distance while reinforcing the movement’s emphasis on harmony and unity.

Tonalist subject matter typically included quiet, meditative landscapes, often featuring elements like rivers, forests, meadows, or solitary figures. Unlike the grand, dramatic vistas of the earlier Hudson River School, Tonalist landscapes were more intimate and subdued. The goal was to suggest rather than describe, inviting viewers to interpret the scene emotionally rather than analytically. This subtle and poetic approach to painting set Tonalism apart from other movements of its time.

James McNeill Whistler and His Pioneering Role in Tonalism

James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) played a crucial role in shaping the aesthetic foundations of Tonalism. Born in Lowell, Massachusetts, he spent much of his artistic career in Europe, where he was influenced by the works of J.M.W. Turner and Japanese prints. He believed that painting should evoke a sense of harmony and beauty, much like music, and he often gave his works musical titles like Nocturne or Symphony. His belief in art for art’s sake directly influenced the philosophy behind Tonalism.

Whistler’s Nocturne series, painted between the 1860s and 1870s, is considered one of the earliest examples of Tonalist painting. These works depicted London’s Thames River at night, shrouded in mist and illuminated by soft, glowing lights. Rather than focusing on architectural details, Whistler used delicate brushstrokes and veiled color transitions to create a sense of stillness and mystery. His paintings were often criticized for their lack of traditional realism, but they were deeply influential on American Tonalist artists.

One of the most famous controversies of Whistler’s career was his legal battle with art critic John Ruskin in 1878. Ruskin harshly criticized Whistler’s painting Nocturne in Black and Gold, accusing him of “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.” Whistler sued for libel and won the case, but the trial left him financially devastated. Despite this, his innovative approach to painting helped establish Tonalism as a respected artistic movement.

Whistler’s impact extended beyond painting, influencing interior design, printmaking, and photography. His use of subtle gradations of tone and emphasis on mood over detail became defining features of Tonalism. While he did not directly align himself with the movement, his work laid the foundation for many of its core principles, and his influence can be seen in countless American painters who followed.

George Inness and the Spiritual Essence of Tonalism

George Inness (1825–1894) was one of the most significant figures in the Tonalist movement, known for his deeply spiritual approach to landscape painting. Born in Newburgh, New York, he began his artistic training in the Hudson River School tradition, which emphasized grand, detailed landscapes. However, as his style evolved, he moved away from rigid realism and adopted a softer, more atmospheric approach. Inness believed that paintings should not just depict nature but should also evoke a sense of the divine and the eternal, a philosophy that aligned closely with the principles of Tonalism.

Inness was profoundly influenced by Swedenborgian mysticism, a spiritual movement based on the teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg, an 18th-century philosopher and theologian. Swedenborg taught that the physical world was a reflection of the spiritual world, a concept that resonated deeply with Inness. His paintings often featured hazy, glowing landscapes bathed in golden light, symbolizing the presence of something greater than what the eye could see. Works like The Lackawanna Valley (1855) and Sunset on the Passaic (1891) exemplify his ability to create scenes that feel meditative and transcendent.

Rather than painting with sharp lines and clear details, Inness used soft brushwork and delicate color transitions to create an almost dreamlike effect. His landscapes often depicted fields, rivers, and woodlands at twilight, enveloped in mist or fading light. He was particularly skilled at capturing the interplay of light and shadow, using it to create mood rather than simply to depict a specific time of day. This technique gave his work a timeless, poetic quality that defined Tonalism as a movement focused on emotion rather than factual representation.

As one of Tonalism’s most influential painters, Inness helped establish the movement as a major force in American art. His emphasis on spirituality, harmony, and mood made his paintings deeply personal yet universally resonant. Even after his death in 1894, his influence continued to shape later generations of landscape painters, who admired his ability to express something beyond the visible world through color, tone, and composition.

Other Prominent Tonalist Artists and Their Contributions

While Whistler and Inness were the most famous names associated with Tonalism, many other artists contributed to the movement’s richness and diversity. Dwight Tryon (1849–1925) was one of the key figures, known for his serene depictions of early morning and twilight scenes. His paintings often featured subtle variations in tone, creating a sense of stillness and quiet beauty. Unlike Impressionists, who sought to capture fleeting moments of light, Tryon’s work conveyed a lasting, meditative mood, making him one of the purest practitioners of Tonalism.

Another notable Tonalist painter was Thomas Wilmer Dewing (1851–1938), who took the movement’s principles and applied them to figurative painting rather than landscapes. His works often depicted elegant, ghostly female figures enveloped in misty, atmospheric settings. Dewing’s use of delicate brushwork and muted colors gave his paintings a dreamlike quality, making them feel almost like visual poetry. His unique approach expanded the scope of Tonalism beyond landscapes, showing that its techniques could be used for intimate, contemplative portraiture as well.

Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847–1917) was another artist who contributed to Tonalism, though his work had a more mystical and symbolic quality. His paintings often depicted moody seascapes, dark forests, and mythological scenes, rendered in thick, textured paint that added to their sense of depth and mystery. Ryder’s art had an almost visionary quality, making it distinct from other Tonalist works, yet it shared the movement’s emphasis on atmosphere, emotion, and spiritual resonance.

One of the lesser-known but highly skilled Tonalist painters was Leon Dabo (1864–1960), whose landscapes were characterized by broad, sweeping compositions and luminous color harmonies. His paintings of rivers, mountains, and quiet shorelines often featured a misty, otherworldly atmosphere, reinforcing the dreamlike aesthetic of Tonalism. While he was not as widely recognized as Whistler or Inness, Dabo’s work remains an important part of the movement’s legacy, demonstrating the depth and variety of Tonalist expression.

The Decline of Tonalism and the Rise of New Art Movements

By the early 20th century, Tonalism began to fade as newer artistic movements gained prominence. Impressionism, with its focus on vivid colors and lively brushwork, had already begun to overshadow the quieter, more restrained approach of Tonalist painters. American artists such as Childe Hassam and William Merritt Chase embraced Impressionist techniques, moving away from the monochromatic palettes of Tonalism. This shift marked the beginning of the movement’s decline, as bright, dynamic compositions became the new standard in American art.

Another major challenge to Tonalism came with the rise of the Ashcan School, a group of painters who focused on urban realism and everyday life. These artists rejected the serene, poetic landscapes of Tonalism, instead depicting gritty street scenes, bustling city life, and working-class subjects. Painters like Robert Henri and George Bellows sought to capture the energy and social realities of modern America, leaving little room for the meditative, dreamlike qualities of Tonalist landscapes.

The 1913 Armory Show in New York further accelerated the decline of Tonalism by introducing European Modernism to American audiences. The exhibition showcased radical new styles such as Cubism, Fauvism, and Futurism, which completely redefined artistic expression. Compared to the bold, fragmented compositions of Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, Tonalism seemed subdued and old-fashioned, leading many artists to abandon the movement in favor of newer, more experimental approaches.

Despite its decline, Tonalism never truly disappeared. Many of its core principles—the use of tone to create mood, the emphasis on atmosphere, and the spiritual approach to nature—continued to influence later artistic movements. Even as American art embraced modernism, Tonalism retained a dedicated following among collectors and painters who appreciated its quiet beauty and emotional depth.

The Lasting Influence and Revival of Tonalism

Although Tonalism was largely eclipsed by modern art movements, its influence continued to be felt throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Many later painters, particularly Luminists and Color Field artists, drew inspiration from Tonalism’s emphasis on subtle gradations of light and color. The meditative, atmospheric quality of Tonalist paintings found new expression in minimalist and abstract landscapes, showing the movement’s enduring relevance.

In recent decades, there has been a renewed interest in Tonalist art, particularly among collectors and contemporary landscape painters. Museums and galleries have begun to re-evaluate the movement’s contributions, organizing exhibitions that highlight its unique aesthetic. Many contemporary painters, such as Wolf Kahn and April Gornik, have drawn on Tonalist principles, integrating soft color harmonies and atmospheric depth into their own work.

Tonalism has also found a new audience in digital and photographic arts, where its principles of subtle tonal shifts and emotional depth continue to be explored. Photographers who work in black-and-white or muted color palettes often use Tonalist techniques to evoke mood and narrative. This adaptation shows how the movement’s core ideas remain powerful, even as artistic mediums evolve.

Ultimately, Tonalism remains a timeless and evocative style, offering a meditative alternative to the fast-paced visual culture of today. Its emphasis on harmony, emotion, and spirituality continues to resonate, proving that even in an age of modernity, there is still a place for the quiet beauty of Tonalist landscapes.

Key Takeaways

- Tonalism was an American art movement from the late 19th to early 20th century, focusing on atmosphere, mood, and soft color harmonies.

- James McNeill Whistler and George Inness were leading figures, influencing many artists with their meditative, dreamlike compositions.

- The movement emphasized subtle tonal variations and often depicted quiet landscapes at dawn, dusk, or under moonlight.

- Tonalism declined with the rise of Impressionism, the Ashcan School, and European Modernism in the early 20th century.

- In recent years, Tonalism has experienced a revival, influencing modern landscape painters and photographers.

FAQs

1. What is the main characteristic of Tonalist paintings?

Tonalist paintings emphasize soft, muted colors, atmospheric effects, and emotional depth, often depicting quiet landscapes at twilight or under moonlight.

2. How did Tonalism differ from Impressionism?

Unlike Impressionism, which used bright colors and rapid brushstrokes, Tonalism focused on subtle gradations of tone and mood, creating a more meditative and poetic effect.

3. Who were the most famous Tonalist artists?

James McNeill Whistler, George Inness, Dwight Tryon, Thomas Wilmer Dewing, and Albert Pinkham Ryder were among the most important Tonalist painters.

4. Why did Tonalism decline in popularity?

Tonalism declined with the rise of American Impressionism, the Ashcan School, and Modernist movements like Cubism and Fauvism in the early 20th century.

5. Is Tonalism still influential today?

Yes, Tonalism continues to influence contemporary landscape painters, photographers, and digital artists, particularly in their use of subtle tonal shifts and atmospheric depth.