The Netherlands has played an outsized role in the history of Western art, producing some of the most iconic artists, movements, and innovations. From the intricate panel paintings of the Northern Renaissance to the groundbreaking abstraction of De Stijl, Dutch art reflects a unique combination of technical mastery, innovative thinking, and cultural pride.

Nestled at the crossroads of European trade and culture, the Netherlands has long been a hub of creativity and commerce. Dutch art mirrors the nation’s values: its emphasis on detail and realism reflects a practical mindset, while its explorations of light, color, and emotion reveal a deep connection to beauty and humanity.

A Nation of Artistic Firsts

The Netherlands has contributed transformative innovations to the art world:

- Oil Painting: Early Netherlandish artists perfected oil painting techniques, revolutionizing European art with their luminous, detailed works.

- Genre Painting: During the Dutch Golden Age, scenes of everyday life became a celebrated subject, reflecting the growing importance of middle-class patronage.

- Abstraction: Movements like De Stijl challenged traditional notions of form, paving the way for modern art.

The Golden Thread of Dutch Art

Throughout its history, Dutch art has engaged with a consistent set of themes:

- Realism and Detail: From Jan van Eyck’s jewel-like precision to Vermeer’s luminous interiors, Dutch art has a remarkable eye for detail.

- Human Experience: Whether in the allegorical works of Bruegel or the intimate portraits of Rembrandt, Dutch art celebrates the complexities of life.

- Innovation and Experimentation: From the Renaissance to contemporary art, Dutch artists have consistently pushed the boundaries of their medium.

A Journey Through Dutch Art

This series explores the rich history of Dutch art, from medieval religious works to the contemporary global stage. Highlights include:

- The luminous oil paintings of Jan van Eyck and the surreal visions of Hieronymus Bosch.

- The Golden Age masterpieces of Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Frans Hals.

- The revolutionary abstraction of Piet Mondrian and the dynamic CoBrA group.

- The international influence of contemporary Dutch artists.

Each chapter delves into the movements, figures, and cultural forces that have shaped Dutch art, offering a comprehensive look at one of the world’s most celebrated artistic traditions.

Chapter 1: Medieval Art and the Early Dutch Tradition (1100–1500)

Before the Northern Renaissance brought the Netherlands to the forefront of European art, the medieval period laid the foundation for the region’s artistic identity. From illuminated manuscripts to Gothic architecture, medieval Dutch art reflected the region’s deep religious devotion and growing cultural significance within Europe.

Illuminated Manuscripts: Early Mastery in Detail

Illuminated manuscripts were among the most significant art forms of medieval Europe, and the Netherlands played a pivotal role in their development.

- The Utrecht Psalter (c. 820–850):

- Though technically predating the Netherlands’ rise as an art center, this manuscript reflects early Carolingian influence on the region.

- Its energetic pen illustrations inspired generations of manuscript illumination.

- The Hours of Catherine of Cleves (c. 1440):

- A masterpiece of Dutch illumination, this prayer book features intricate borders filled with flowers, insects, and religious scenes.

- The manuscript is a testament to the region’s technical skill and decorative imagination.

Gothic Architecture: Verticality and Light

The Gothic style dominated medieval architecture, influencing cathedrals, monasteries, and civic buildings across the Netherlands.

- St. John’s Cathedral, ’s-Hertogenbosch:

- A prime example of Brabantine Gothic, this cathedral is known for its elaborate stone carvings and soaring interior spaces.

- Construction began in 1220 and continued into the 16th century, showcasing the evolution of Gothic architecture.

- Town Halls and Civic Buildings:

- As cities like Bruges and Ghent flourished, civic architecture became more prominent.

- The Bruges Belfry (completed 15th century) exemplifies the fusion of functionality and Gothic ornamentation.

Panel Painting: The Beginnings of Netherlandish Art

By the late medieval period, panel painting emerged as a distinct art form in the Netherlands, laying the groundwork for the Northern Renaissance.

- Diptychs and Triptychs:

- Religious altarpieces were the primary subject of early Dutch panel painting.

- The Ghent Altarpiece (1432), completed by Jan and Hubert van Eyck, is an early masterpiece that would later influence Renaissance art.

- Innovations in Technique:

- Artists began experimenting with oil paint, which allowed for greater detail, depth, and luminosity compared to tempera.

Sculpture and Religious Devotion

Medieval Dutch sculpture reflected the centrality of religion in daily life.

- Wooden Altarpieces:

- Elaborate altarpieces carved from oak were common in churches throughout the Netherlands.

- These works often depicted scenes from the Passion of Christ, featuring intricate details and dramatic expressions.

- Madonna and Child Statues:

- Small devotional statues, often made from alabaster or ivory, were popular among wealthy patrons.

Themes of Medieval Dutch Art

Medieval Dutch art was characterized by its focus on spirituality, community, and craftsmanship:

- Religious Devotion: Art was primarily created for ecclesiastical purposes, emphasizing the spiritual over the personal.

- Craftsmanship and Detail: From manuscripts to woodcarvings, medieval Dutch art displayed a remarkable attention to detail and technical skill.

- Emerging Civic Pride: The growing importance of cities like Bruges and Ghent influenced the development of civic art and architecture.

The Transition to the Renaissance

By the late 15th century, the Netherlands was on the cusp of an artistic revolution. The invention of oil painting and the increasing influence of humanism set the stage for the Northern Renaissance, where Dutch art would achieve global renown.

Chapter 2: The Northern Renaissance and Early Netherlandish Art (1400–1600)

The Northern Renaissance transformed Dutch art, marking a period of extraordinary innovation and creativity. Early Netherlandish artists such as Jan van Eyck, Hieronymus Bosch, and Pieter Bruegel the Elder revolutionized European art with their pioneering use of oil paint, meticulous attention to detail, and exploration of complex themes. This era laid the foundation for the Dutch Golden Age and cemented the Netherlands as a center of artistic excellence.

Jan van Eyck: The Master of Oil Painting

Jan van Eyck (c. 1390–1441) is one of the most celebrated figures of the Northern Renaissance, renowned for his technical innovations and unmatched realism.

- The Ghent Altarpiece (1432):

- Created with his brother Hubert, this polyptych is a masterpiece of religious art, depicting scenes such as the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb in stunning detail.

- Van Eyck’s use of oil paint allowed for unprecedented luminosity and depth.

- The Arnolfini Portrait (1434):

- This enigmatic double portrait is celebrated for its intricate detail, symbolism, and use of light. The convex mirror in the background reflects the entire scene, showcasing van Eyck’s mastery of perspective.

Hieronymus Bosch: The Visionary

Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450–1516) is famed for his fantastical and often surreal imagery, which explored themes of morality, sin, and redemption.

- The Garden of Earthly Delights (c. 1490–1510):

- This triptych juxtaposes scenes of paradise, earthly pleasures, and hell in a work that defies easy interpretation. Its bizarre and imaginative figures are unparalleled in art history.

- The Haywain Triptych (c. 1516):

- Bosch’s moralistic storytelling is evident in this work, which critiques humanity’s pursuit of material wealth and pleasure.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder: The Painter of Peasants

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525–1569) brought a humanistic perspective to art, focusing on landscapes, folklore, and scenes of everyday life.

- Hunters in the Snow (1565):

- This iconic winter landscape captures the stark beauty of nature and the struggles of rural life with a poetic sensibility.

- The Tower of Babel (1563):

- A complex allegory about human ambition and divine punishment, this painting reflects Bruegel’s interest in moral and biblical themes.

Innovations in Detail and Symbolism

Early Netherlandish artists are renowned for their meticulous attention to detail and the symbolic richness of their works.

- Religious Symbolism:

- Van Eyck’s works are filled with religious symbols, such as the lamb in the Ghent Altarpiece, representing Christ’s sacrifice.

- Moral Allegories:

- Bosch’s paintings often serve as moral lessons, warning viewers against the dangers of sin and temptation.

- Everyday Life:

- Bruegel’s focus on peasants and daily activities brought a new dimension of realism to art, emphasizing humanity’s connection to nature.

Portraiture and Patronage

The rise of a wealthy merchant class in the Netherlands during this period created a demand for portraiture and secular themes.

- Realism in Portraiture:

- Artists like van Eyck elevated portraiture to a high art form, capturing their sitters’ personalities with remarkable fidelity.

- Secular Themes:

- While religious art remained dominant, artists increasingly explored secular subjects, including landscapes, domestic interiors, and still lifes.

The Influence of the Northern Renaissance

The innovations of the Northern Renaissance had a profound impact on European art:

- Oil Painting Techniques: Van Eyck’s mastery of oil paint set a standard that influenced artists across Europe.

- Complex Themes: The symbolic richness of Netherlandish art inspired artists to explore deeper moral and philosophical ideas.

- A New Realism: The detailed and lifelike quality of Northern Renaissance art paved the way for the realism of the Dutch Golden Age.

Transition to the Golden Age

As the 16th century gave way to the 17th, the Netherlands experienced a cultural and economic flourishing that would culminate in the Dutch Golden Age. The innovations of the Northern Renaissance provided the foundation for this unprecedented era of artistic achievement.

Chapter 3: The Dutch Golden Age: Mastery in Painting (1600–1700)

The Dutch Golden Age was a period of unparalleled artistic achievement, coinciding with the Netherlands’ rise as a global economic and political power. During this time, Dutch painters mastered a variety of genres, from portraits and still lifes to landscapes and genre scenes, reflecting the values of a prosperous and culturally vibrant society. Artists such as Rembrandt van Rijn, Johannes Vermeer, and Frans Hals produced works of extraordinary technical and emotional depth, solidifying the Netherlands as a leader in Western art.

The Context of the Golden Age

The Dutch Golden Age emerged from the unique conditions of 17th-century Netherlands:

- Economic Prosperity:

- The Dutch Republic became a major trading power, generating wealth that supported a flourishing art market.

- A wealthy middle class emerged, commissioning art for private enjoyment, which shifted the focus from religious themes to secular subjects.

- Religious and Political Climate:

- The Protestant Reformation discouraged religious imagery in public spaces, leading to the rise of secular art.

- The independence of the Dutch Republic from Spain fostered a sense of national pride, reflected in art.

Rembrandt van Rijn: The Master of Light and Shadow

Rembrandt (1606–1669) is often regarded as one of the greatest painters in Western art, known for his portraits, biblical scenes, and innovative use of chiaroscuro (light and shadow).

- The Night Watch (1642):

- One of the most iconic works of the Golden Age, this large-scale group portrait depicts a militia company in a dynamic, dramatic composition.

- The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632):

- This group portrait demonstrates Rembrandt’s ability to capture individuality and narrative within a collective setting.

- Self-Portraits:

- Rembrandt created over 80 self-portraits, charting his physical and emotional journey with unparalleled honesty and depth.

Johannes Vermeer: The Poet of Light

Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675) is celebrated for his intimate domestic scenes, where he masterfully depicted light and atmosphere.

- Girl with a Pearl Earring (c. 1665):

- Known as the “Mona Lisa of the North,” this portrait combines simplicity with mystery, showcasing Vermeer’s exquisite handling of light.

- The Milkmaid (c. 1658):

- A study of a domestic servant at work, this painting captures the dignity of everyday life with rich color and meticulous detail.

- The Art of Painting (c. 1666–1668):

- A complex allegory about the act of creation, this work reflects Vermeer’s profound engagement with the art of his time.

Frans Hals: The Painter of Life

Frans Hals (1582–1666) brought energy and spontaneity to portraiture, capturing his sitters’ personalities with remarkable vitality.

- The Laughing Cavalier (1624):

- Hals’ dynamic brushwork and vivid colors make this portrait a standout example of his lively style.

- Group Portraits:

- Hals excelled in group portraits, such as The Banquet of the Officers of the St. George Militia Company (1616), which convey a sense of camaraderie and individuality.

Other Key Genres of the Dutch Golden Age

Still Lifes: Beauty and Mortality

Still life painting flourished during this period, reflecting both the wealth and the piety of Dutch society.

- Vanitas Still Lifes:

- These works incorporated symbols of mortality, such as skulls, extinguished candles, and wilting flowers, reminding viewers of life’s transience.

- Floral Still Lifes:

- Artists like Rachel Ruysch and Jan Davidsz. de Heem created intricate compositions of flowers, showcasing the Dutch fascination with nature and luxury.

Landscapes: The Dutch Countryside and Beyond

The Dutch Golden Age saw the rise of landscape painting, capturing both the beauty of the Netherlands and its maritime power.

- Jacob van Ruisdael:

- Van Ruisdael’s dramatic landscapes, such as View of Haarlem with Bleaching Fields (1670), convey a sense of national pride and the sublime power of nature.

- Seascapes:

- Artists like Willem van de Velde the Younger depicted the Netherlands’ naval dominance with striking maritime scenes.

Genre Scenes: Everyday Life in Focus

Genre painting, which depicted scenes of everyday life, became a hallmark of the Dutch Golden Age.

- Jan Steen:

- Steen’s humorous and chaotic domestic scenes, such as The Feast of Saint Nicholas (1665–1668), offer a window into the moral and social dynamics of the time.

- Pieter de Hooch:

- Known for his quiet, orderly interiors, de Hooch’s works celebrate domestic harmony and light.

Themes of the Dutch Golden Age

The art of the Dutch Golden Age reflects the values and concerns of its time:

- Individualism: Portraiture celebrated the uniqueness of the individual, reflecting the rise of the middle class.

- Secularism: While religious art declined, secular themes like landscapes and genre scenes flourished.

- National Identity: Many works celebrated Dutch achievements in trade, science, and exploration.

The End of the Golden Age

By the late 17th century, political and economic challenges, including wars and declining trade, brought the Dutch Golden Age to a close. However, the innovations of this period continued to influence art for centuries, laying the groundwork for the next phases of Dutch artistic development.

Chapter 4: The 18th Century: Decline and Transition (1700–1800)

The 18th century was a quieter period in Dutch art, reflecting a decline in the Netherlands’ economic and political dominance. As the Dutch Republic faced competition from rising powers like Britain and France, its art market shifted focus. While the grand achievements of the Golden Age were no longer at the forefront, the period saw continued refinement in certain genres, particularly decorative arts, portraiture, and genre scenes, as well as the growth of academic influences.

Economic and Cultural Shifts

The decline of the Dutch Golden Age was tied to larger geopolitical and economic changes:

- Economic Decline:

- The Netherlands’ maritime dominance waned due to competition with Britain and other European powers.

- A reduction in middle-class patronage affected the demand for art.

- Changing Tastes:

Portraiture: Tradition and Refinement

Portraiture remained a vital genre during the 18th century, continuing to reflect the wealth and aspirations of Dutch society.

- Cornelis Troost (1696–1750):

- One of the standout portraitists of the era, Troost blended Dutch traditions with Rococo elegance. Works like Portrait of the Hartog Family exemplify his ability to capture personality and social standing.

- Formal and Intimate Portraits:

- Portraits ranged from grand, formal depictions of the elite to more intimate representations of the emerging bourgeoisie.

Genre Painting and Everyday Life

The 18th century saw a continuation of the genre painting tradition, though with a shift toward lighter, more decorative themes.

- Moralizing Scenes:

- Following the example of Golden Age artists like Jan Steen, 18th-century genre paintings often conveyed moral lessons, though with a softer tone.

- Everyday Settings:

- Artists like Jan Ekels the Elder depicted domestic and tavern scenes, focusing on humor and human interaction.

Still Lifes and Decorative Arts

Still life painting remained popular, reflecting the Dutch love for craftsmanship and luxury.

- Floral Still Lifes:

- The tradition of intricate floral arrangements continued, with artists like Jan van Huysum achieving fame for their vibrant, detailed compositions.

- Decorative Arts:

- The 18th century was a golden age for Dutch decorative arts, particularly ceramics and furniture.

- Delftware, a distinctive type of blue-and-white pottery, was highly prized both locally and internationally.

- Dutch cabinetmakers created finely crafted furniture that blended functionality with elegance.

The Rise of Academic Art

As the influence of the Dutch Golden Age waned, Dutch artists began engaging more with European academic traditions.

- Academic Painting:

- History Painting:

- Although less prominent than in earlier centuries, history painting began to re-emerge, influenced by European trends.

Themes of the 18th Century

The art of the 18th century reflects a period of transition and adaptation:

- Continuity and Change: Dutch art maintained its traditional strengths in portraiture and genre scenes while adapting to international tastes.

- Craftsmanship: The decorative arts flourished, showcasing the enduring Dutch commitment to fine craftsmanship.

- Moral and Social Commentary: Genre painting continued to explore themes of morality and social interaction, albeit in a less dramatic way than in the Golden Age.

The Path to Revival

While the 18th century was less dynamic than the Golden Age, it set the stage for the artistic resurgence of the 19th century. Dutch artists would soon engage with Romanticism and Realism, revitalizing their connection to landscape and narrative art while incorporating modern influences.

Chapter 5: The 19th Century: Romanticism and Realism (1800–1880)

The 19th century marked a revival in Dutch art, as artists began to engage with the broader European movements of Romanticism and Realism. While maintaining a connection to traditional Dutch genres such as landscapes and genre painting, Dutch artists infused their works with the drama, emotion, and social concerns characteristic of the era. This period also saw a renewed interest in national identity, as the Netherlands reasserted itself culturally after a period of decline.

Romanticism in Dutch Art

Romanticism in the Netherlands expressed an emotional connection to nature and history, often emphasizing dramatic landscapes, stormy seascapes, and nostalgic depictions of the Dutch countryside.

- Barend Cornelis Koekkoek (1803–1862):

- Known as the “Prince of Landscape Painting,” Koekkoek painted sweeping, idealized views of the Dutch and German countryside.

- Works like View of the Rhine near Cleves (1847) capture the Romantic fascination with nature’s beauty and power.

- Andreas Schelfhout (1787–1870):

- A master of winter landscapes, Schelfhout’s works, such as Winter Landscape with Ice Skaters (1838), evoke the serene beauty of Dutch winters while reflecting Romantic nostalgia.

Historical and Narrative Painting

Dutch artists engaged with historical and literary themes during this period, reflecting the Romantic interest in storytelling and the past.

- Johannes Hermanus Koekkoek:

- Known for his maritime scenes, Koekkoek depicted ships and coastal life with dramatic intensity, often focusing on stormy seas and heroic struggles.

- Willem Maris (1844–1910):

- While more closely associated with Realism, Maris’ works often blend the emotional tones of Romanticism with a focus on the beauty of rural life.

The Realist Movement

By the mid-19th century, Realism emerged as a dominant force in Dutch art, reflecting a shift toward the honest depiction of contemporary life and labor.

- Jozef Israëls (1824–1911):

- Known as the “Dutch Millet,” Israëls focused on the hardships of rural and working-class life.

- Paintings like Alone in the World (1856) and The Fisherman’s Family (1863) convey empathy and social awareness, showcasing the influence of French Realism.

- Hendrik Willem Mesdag (1831–1915):

- Mesdag specialized in marine scenes, such as The Bombardment of the Hague (1873), capturing the lives of fishermen and the power of the sea with striking realism.

The Hague School

The Hague School, a group of Realist painters active in the latter half of the 19th century, was inspired by both the Dutch Golden Age and the Barbizon School in France.

- Anton Mauve (1838–1888):

- Mauve’s pastoral scenes, such as The Return of the Flock (1872), highlight the quiet beauty of rural life, emphasizing mood and atmosphere.

- Jacob Maris (1837–1899):

- Known for his cityscapes and landscapes, Maris painted works like The Bridge at Rotterdam (1869), capturing the everyday charm of Dutch life.

- Willem Roelofs (1822–1897):

- Roelofs’ landscapes reflect the transition from Romanticism to Realism, with an emphasis on light and naturalism.

Genre Painting and Portraiture

Genre painting and portraiture also flourished during this period, often reflecting the social and cultural changes of 19th-century Netherlands.

- Portraiture:

- Artists like Jan Hendrik Weissenbruch (1824–1903) combined realism with psychological depth in their portraits, capturing the individuality of their subjects.

- Genre Scenes:

- Everyday life remained a popular subject, with artists focusing on rural labor, domestic interiors, and village life.

Themes of 19th-Century Dutch Art

The art of the 19th century reflects a period of renewal and transformation in Dutch culture:

- Nature and Rural Life: Romantic and Realist painters celebrated the Dutch landscape and rural traditions, connecting contemporary art to the Golden Age.

- Social Awareness: Realist artists addressed the challenges of industrialization and poverty, creating works that highlighted the dignity and struggles of ordinary people.

- National Identity: A renewed pride in Dutch culture and history permeated the art of this period, reflecting the country’s cultural revival.

The Path to Modernism

By the end of the 19th century, Dutch art was on the cusp of modernism. The emergence of painters like Vincent van Gogh and movements like the Hague School set the stage for a new era of innovation, bridging the traditional and the avant-garde.

Chapter 6: The Fin de Siècle: Vincent van Gogh and Post-Impressionism (1880–1900)

The late 19th century, or fin de siècle, was a transformative period for Dutch art, bridging the traditions of Realism with the emerging innovations of Modernism. This era is inseparably linked with Vincent van Gogh, whose revolutionary approach to color, emotion, and brushwork made him one of the most influential figures in art history. While van Gogh dominated the international stage, other Dutch artists continued to explore new styles and techniques, laying the groundwork for the 20th century.

Vincent van Gogh: The Genius of Emotion and Color

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) is undoubtedly the most famous Dutch artist of this period, and his work redefined the possibilities of painting.

- Early Career and The Hague School Influence:

- Van Gogh’s early works, like The Potato Eaters (1885), reflect his engagement with the Realism of the Hague School, emphasizing the struggles of rural life.

- These works are characterized by dark tones, earthy palettes, and a focus on social themes.

- The Paris Years (1886–1888):

- In Paris, van Gogh encountered the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, including Claude Monet, Paul Gauguin, and Georges Seurat.

- Works like Boulevard de Clichy (1887) showcase his experimentation with lighter colors and the influence of pointillism.

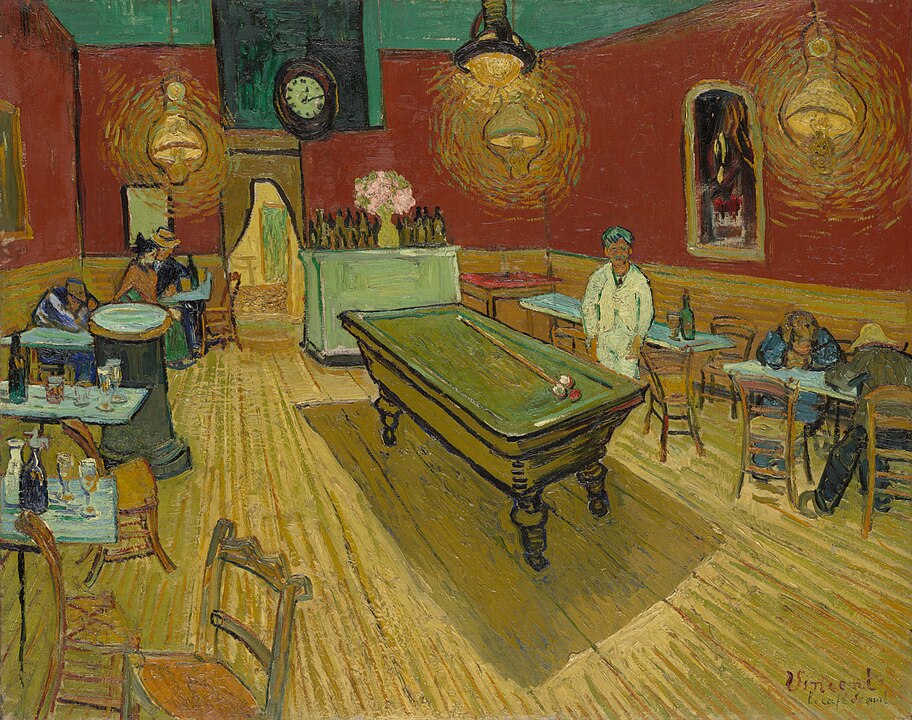

- The Arles Period (1888–1889):

- Van Gogh’s move to Arles in southern France marked a turning point in his art, with vibrant, expressive works like Sunflowers (1888) and The Bedroom (1888).

- His iconic The Starry Night (1889), painted during his stay at the asylum in Saint-Rémy, captures his emotional intensity and unique vision of the natural world.

- Legacy:

- Despite his tragic death at the age of 37, van Gogh’s body of work—over 2,100 pieces—remains a cornerstone of modern art, influencing movements from Fauvism to Expressionism.

The Hague School’s Transition

While van Gogh was breaking new ground internationally, many Dutch artists remained rooted in the traditions of the Hague School, blending Realism with modern influences.

- Jozef Israëls and Anton Mauve:

- These painters continued to create evocative depictions of rural life, emphasizing mood and atmosphere.

- Their work provided a foundation for younger artists, including van Gogh, who admired their ability to capture the human condition.

Symbolism and the Fin de Siècle

The late 19th century also saw the rise of Symbolism in Dutch art, a movement that explored the spiritual, the mysterious, and the imaginative.

- Jan Toorop (1858–1928):

- Toorop was one of the leading Dutch Symbolists, drawing inspiration from both traditional Dutch art and international styles like Art Nouveau.

- Works like The Three Brides (1893) exemplify his mystical approach, with intricate patterns and dreamlike compositions.

Landscape Painting and Urban Scenes

Dutch artists of this period also continued the country’s long tradition of landscape painting, blending Romanticism and Realism with modern techniques.

- Jacob Maris and Willem Maris:

- The Maris brothers remained prominent figures, capturing Dutch landscapes and seascapes with a poetic touch.

- George Hendrik Breitner (1857–1923):

- Breitner focused on urban life, painting bustling cityscapes of Amsterdam and Rotterdam. His works, such as Girl in a Red Kimono (1893), show his ability to blend realism with impressionistic influences.

The Influence of the Paris Art Scene

The proximity and cultural exchange with Paris played a crucial role in shaping late 19th-century Dutch art.

- Impact of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism:

- Dutch artists adopted the loose brushwork and vibrant palettes of Impressionism, integrating these techniques into traditional genres like landscapes and genre scenes.

- Paul Gabriël (1828–1903):

- Gabriël was known for his light-filled depictions of the Dutch countryside, influenced by French plein air painting.

Themes of the Fin de Siècle

The art of the fin de siècle reflects a period of transition, blending the old and the new:

- Emotion and Spirituality: Symbolist artists like Toorop explored themes of mystery, religion, and human connection.

- Nature and Landscape: The enduring beauty of the Dutch countryside remained a central subject.

- Experimentation and Modernity: Van Gogh and his contemporaries pushed the boundaries of traditional art, setting the stage for the 20th century.

The Dawn of Modernism

By the end of the 19th century, Dutch art was poised for a new era of innovation. Van Gogh’s groundbreaking work, the influence of Symbolism, and the continued refinement of Dutch traditions would inspire the abstract and modernist movements of the 20th century, including De Stijl and CoBrA.

Chapter 7: De Stijl and Early Modernism (1900–1940)

The early 20th century was a period of radical innovation in Dutch art, as artists sought new ways to respond to the rapidly changing world. The Netherlands became a major player in the development of modernism, most notably through the groundbreaking movement known as De Stijl. Led by Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg, De Stijl emphasized abstraction, geometry, and universal harmony, influencing art, design, and architecture worldwide. Alongside De Stijl, other Dutch artists explored Cubism, Expressionism, and the intersection of traditional and modernist aesthetics.

De Stijl: A Revolution in Abstraction

Founded in 1917, De Stijl was one of the most influential modernist movements of the 20th century. Its members sought to create a universal visual language based on geometric abstraction, balance, and harmony.

- Principles of De Stijl:

- Simplification of forms to basic geometric shapes (rectangles, squares).

- Use of primary colors (red, blue, yellow) combined with black, white, and gray.

- Emphasis on asymmetry and balance.

- A goal of integrating art with everyday life through architecture and design.

Piet Mondrian (1872–1944)

Mondrian was the most famous figure of De Stijl, whose works epitomized the movement’s ideals.

- Composition with Red, Blue, and Yellow (1930):

- This iconic painting exemplifies Mondrian’s mature style, with its grid of black lines and blocks of primary color.

- Evolution of Style:

- Mondrian’s early works, such as his naturalistic landscapes, show his gradual journey toward abstraction, influenced by Cubism.

Theo van Doesburg (1883–1931)

Van Doesburg was the primary theorist and organizer of De Stijl, expanding its influence beyond painting.

- The Red and Blue Chair (designed by Gerrit Rietveld, 1918):

- Though Rietveld was a designer, van Doesburg’s promotion of his furniture integrated De Stijl into three-dimensional design.

- Architecture and Typography:

- Van Doesburg’s experiments in architecture, such as the Café Aubette (1928), reflected De Stijl’s principles of harmony and abstraction.

Cubism and Early Modernism in the Netherlands

Before and alongside De Stijl, Dutch artists explored Cubism and other modernist styles, integrating international influences into their work.

- Piet Mondrian’s Early Cubism:

- Mondrian’s works like Gray Tree (1911) demonstrate his engagement with Cubist techniques before he fully embraced abstraction.

- Bart van der Leck (1876–1958):

- A founding member of De Stijl, van der Leck’s work combined Cubism with the movement’s emphasis on flat planes and bold colors.

Expressionism and Emotional Abstraction

While De Stijl focused on rationality and order, other Dutch artists embraced the emotional intensity of Expressionism.

- Charley Toorop (1891–1955):

- Toorop’s work reflects a blend of Expressionism and social realism, often addressing themes of labor and human struggle.

- Her painting The Friends’ Meal (1932–1933) captures the raw emotional power of the Expressionist style.

- Jan Sluyters (1881–1957):

- Sluyters explored vibrant color and dynamic compositions, moving between Expressionism and Fauvism.

Architecture and Design: A Total Art

De Stijl’s influence extended far beyond painting, shaping Dutch architecture and design in profound ways.

- Gerrit Rietveld (1888–1964):

- The Rietveld Schröder House (1924) in Utrecht is a masterpiece of modern architecture, embodying De Stijl’s principles in three dimensions.

- Rietveld’s furniture designs, such as the Red and Blue Chair, became icons of modern design.

- J.J.P. Oud (1890–1963):

- As a prominent architect of the time, Oud applied modernist principles to housing projects, contributing to functional and aesthetically innovative urban spaces.

Themes of Early Modernism in Dutch Art

The art and design of this period reflect a dynamic interplay between tradition and innovation:

- Abstraction and Universalism:

- De Stijl artists sought to transcend national boundaries by creating a universal visual language.

- Emotion and Individualism:

- Expressionist artists emphasized personal emotion and social issues, offering a counterpoint to De Stijl’s rationalism.

- Integration of Art and Life:

- The emphasis on architecture and design reflected a belief that art should enhance everyday living.

The Legacy of De Stijl and Early Modernism

The De Stijl movement profoundly influenced modern art, design, and architecture worldwide, inspiring movements like the Bauhaus and International Style. Its principles continue to resonate in contemporary design, while the Expressionist works of artists like Charley Toorop reflect the diverse approaches to modernism in the Netherlands.

As the Netherlands entered the mid-20th century, the country’s art scene would further expand its global influence, driven by experimentation and a redefinition of artistic identity.

Chapter 8: Post-War Dutch Art: Experimentation and Identity (1945–2000)

The aftermath of World War II ushered in a new era for Dutch art, defined by experimentation, innovation, and a search for identity in a rapidly changing world. Dutch artists played key roles in global avant-garde movements, from CoBrA to conceptual art. While rooted in the Netherlands’ artistic traditions, this period saw Dutch art breaking boundaries, engaging with international trends, and addressing contemporary social and political issues.

CoBrA: A Post-War Avant-Garde Movement

Founded in 1948, CoBrA (an acronym for Copenhagen, Brussels, Amsterdam) was an experimental collective that rejected academic traditions and celebrated spontaneity, emotion, and childlike creativity.

- Principles of CoBrA:

- Emphasis on freedom of expression, rejecting rigid forms and structures.

- Inspiration drawn from folk art, primitive art, and the drawings of children.

- A focus on vibrant colors, dynamic compositions, and raw emotional power.

- Key Dutch Members:

- Karel Appel (1921–2006):

- One of the most famous CoBrA artists, Appel’s bold, colorful works, such as Questioning Children (1949), reflect the movement’s anarchic spirit.

- Corneille (1922–2010):

- Corneille’s works, like Birds in the City (1953), combined abstract forms with playful imagery inspired by nature and mythology.

- Lucebert (1924–1994):

- A painter and poet, Lucebert explored themes of freedom, rebellion, and human struggle in his powerful, expressive works.

- Karel Appel (1921–2006):

Abstract and Conceptual Art

As the mid-20th century progressed, Dutch artists increasingly engaged with abstract and conceptual art, emphasizing ideas and process over traditional aesthetics.

- Jan Schoonhoven (1914–1994):

- Schoonhoven was a key figure in the Zero (or Nul) movement, creating minimalist reliefs that explored texture, repetition, and light.

- His works, such as R70-16 (1970), reflect a meticulous approach to abstraction, using simple materials like paper and cardboard.

- Stanley Brouwn (1935–2017):

- Brouwn’s conceptual works often dealt with themes of measurement, space, and human interaction, challenging traditional notions of art.

The Influence of Pop Art

Dutch artists absorbed the global Pop Art movement, reinterpreting its themes of consumerism, mass media, and modern life with a distinctly Dutch sensibility.

- Marinus Boezem (b. 1934):

- Boezem’s conceptual installations often incorporate humor and critique of consumer culture.

- Works like The Green Cathedral (1978) integrate nature and architecture, reflecting a playful yet critical approach to modernity.

Land Art and Environmental Art

The Netherlands’ relationship with its environment—defined by reclaimed land, waterways, and urban development—inspired significant contributions to land art.

- Robert Smithson’s Spiral Hill (1971):

- Although an American artist, Smithson’s work in the Netherlands, including Broken Circle/Spiral Hill, symbolizes the global exchange of ideas during this period.

- Hans Haacke (b. 1936):

- Haacke’s environmental installations, while global in reach, resonated in the Netherlands due to the country’s focus on ecological preservation.

Post-War Identity and Social Engagement

Post-war Dutch art often reflected a deep engagement with issues of national identity, history, and contemporary society.

- Photography and Film:

- Photographers like Ed van der Elsken (1925–1990) captured the energy and grit of post-war urban life, creating a vivid portrait of Dutch society.

- Filmmakers such as Joris Ivens (1898–1989) used the medium to explore themes of labor, politics, and international solidarity.

- Political Art:

- Artists like Marcel Broodthaers (1924–1976) used their work to critique consumerism, nationalism, and the commodification of art.

Themes of Post-War Dutch Art

The art of this period reflects a dynamic interplay of local traditions and global influences:

- Freedom and Experimentation: The CoBrA movement and conceptual art emphasized the importance of individual expression and creative freedom.

- Engagement with Society: Many artists addressed contemporary issues, from consumer culture to environmental challenges.

- A Search for Identity: Post-war Dutch art often grappled with questions of cultural and national identity in a modern, globalized world.

The Path to the 21st Century

By the end of the 20th century, Dutch art was firmly established as a global force, characterized by its diversity, innovation, and ability to adapt to changing times. Movements like CoBrA and the Zero group laid the groundwork for contemporary art, while Dutch artists continued to push boundaries in concept and form.

Chapter 9: Contemporary Dutch Art (2000–Present)

Contemporary Dutch art reflects a dynamic fusion of tradition, innovation, and global influence. In a world shaped by rapid technological advances and evolving social challenges, Dutch artists continue to push boundaries, addressing themes such as identity, sustainability, and the digital age. The Netherlands remains a hub of creativity, fostering a thriving art scene that spans diverse media, from traditional painting and sculpture to cutting-edge digital installations.

Art and Technology: The Digital Revolution

The 21st century has brought new opportunities for Dutch artists to integrate technology into their work, creating immersive and interactive experiences.

- Studio Drift:

- This Amsterdam-based collective combines art, technology, and nature to create thought-provoking installations. Their work Fragile Future (2005–present) features delicate sculptures of dandelion seeds fused with LED lights, exploring themes of fragility and innovation.

- Daan Roosegaarde:

- Roosegaarde’s interactive projects, such as Waterlicht (2015), use light and technology to create immersive environments that address climate change and the power of water in Dutch culture.

- Rafael Rozendaal:

- A pioneer in digital art, Rozendaal’s internet-based works and installations redefine the boundaries of traditional art, engaging with themes of interactivity and digital culture.

Sustainability and Environmental Art

The Netherlands’ historic relationship with water and land reclamation has made sustainability a central theme in contemporary art.

- Olafur Eliasson:

- While not Dutch, Eliasson’s large-scale installations, such as Your Waste of Time (2006), resonate with Dutch concerns about climate change and ecological preservation.

- Marinus Boezem:

- Boezem’s The Green Cathedral (1987–present), a living installation made of trees, continues to be a symbol of environmental awareness in contemporary Dutch art.

Explorations of Identity and Migration

The Netherlands’ multicultural society inspires many contemporary artists to explore themes of identity, migration, and globalization.

- Remy Jungerman:

- Jungerman’s work blends traditional Surinamese motifs with Dutch abstract art, reflecting his dual heritage and addressing colonial histories.

- His Horizon Verticals series (2016–present) integrates textiles, geometric patterns, and cultural symbolism.

- Iris Kensmil:

- Kensmil explores the contributions of the African diaspora to Dutch culture, using portraits and installations to address history and representation.

Photography and Contemporary Storytelling

Dutch photographers continue to innovate in visual storytelling, creating works that examine modern life and identity.

- Erwin Olaf:

- Known for his staged, cinematic photography, Olaf’s works, such as Grief (2007), explore themes of beauty, isolation, and societal expectations.

- Rineke Dijkstra:

- Dijkstra’s intimate portraits, such as her Beach Portraits series (1992–2002), capture moments of vulnerability and transformation, often focusing on youth and identity.

Public Art and Urban Spaces

Public art plays a significant role in contemporary Dutch culture, transforming urban landscapes into spaces for creative engagement.

- Joep van Lieshout:

- Van Lieshout’s large-scale sculptures and architectural installations, such as AVL-Ville (2001), challenge traditional notions of art, architecture, and urban planning.

- Banksy in Amsterdam:

- Though not Dutch, Banksy’s works have appeared in urban spaces throughout the Netherlands, highlighting the global exchange of street art culture.

Institutions and International Influence

The Netherlands continues to nurture its art scene through world-class institutions and festivals.

- The Rijksakademie:

- This prestigious residency program in Amsterdam supports emerging artists from around the world, fostering innovation and collaboration.

- Venice Biennale:

- Dutch artists regularly participate in the Venice Biennale, showcasing their work on a global stage.

- Museums:

- Institutions like the Rijksmuseum, Stedelijk Museum, and Van Gogh Museum remain central to Dutch cultural life, bridging past and present.

Themes of Contemporary Dutch Art

Contemporary Dutch art is defined by its engagement with critical issues and its embrace of new technologies:

- Technology and Interaction: Artists like Studio Drift and Daan Roosegaarde use technology to create immersive, socially relevant works.

- Multiculturalism and Identity: Dutch artists explore themes of heritage, migration, and representation in a globalized world.

- Environmental Awareness: Sustainability and ecological themes continue to resonate, reflecting the Netherlands’ historic relationship with the natural world.

The Future of Dutch Art

As Dutch artists look to the future, their work continues to balance innovation with tradition, addressing the pressing issues of our time while celebrating the Netherlands’ artistic legacy. Through their creativity, Dutch artists reaffirm their place as leaders in the global art scene.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Dutch Art

The history of Dutch art is a remarkable journey through centuries of innovation, technical mastery, and cultural expression. From the meticulous oil paintings of the Northern Renaissance to the bold abstractions of De Stijl and the dynamic, technology-driven works of today, Dutch artists have consistently pushed the boundaries of what art can achieve. This legacy reflects not only the Netherlands’ rich history but also its enduring ability to adapt to change and lead the way in creative expression.

Themes Across the Centuries

Throughout its history, Dutch art has been defined by several recurring themes:

- Innovation: Whether it was the invention of oil painting techniques or the birth of abstract art, Dutch artists have continually reshaped the artistic landscape.

- Realism and Detail: The Dutch Golden Age set a standard for lifelike representation, influencing generations of artists worldwide.

- Social Engagement: From the moral allegories of Pieter Bruegel the Elder to the contemporary explorations of identity and migration, Dutch art often reflects the concerns and values of its time.

- Integration of Art and Life: Movements like De Stijl and the environmental art of today emphasize the connection between art, design, and everyday life.

A Global Influence

The impact of Dutch art extends far beyond the borders of the Netherlands. The innovations of van Eyck, Bosch, and Rembrandt continue to inspire artists around the world, while movements like De Stijl shaped modernist design on an international scale. Dutch contemporary artists remain at the forefront of global art, addressing critical issues like climate change, migration, and the digital revolution.

A Living Tradition

What sets Dutch art apart is its ability to honor tradition while embracing the new. Whether revisiting the landscapes of the Golden Age or pioneering the use of digital media, Dutch artists consistently find ways to balance the past with the future, creating works that are both timeless and forward-thinking.

The Netherlands: A Beacon of Creativity

As a hub of artistic innovation, the Netherlands continues to play a vital role in shaping the cultural conversations of our time. Its world-class institutions, thriving contemporary art scene, and commitment to fostering creativity ensure that Dutch art remains as relevant and inspiring today as it has been for centuries.