Russian art is a reflection of the country’s vast, complex history—an intersection of East and West, tradition and revolution, spirituality and politics. From the mystical Orthodox icons of the medieval period to the radical experiments of the avant-garde, Russian art has continuously evolved, shaped by historical upheavals, ideological shifts, and cultural crosscurrents.

Art in Russia has always carried deep symbolic weight, often intertwined with religious devotion, imperial ambitions, and political propaganda. The country’s unique geographic position—bridging Europe and Asia—has made its artistic identity fluid and dynamic, borrowing from Byzantine, Western European, and indigenous Slavic influences. Over time, these elements fused into something distinctly Russian: a visual language that oscillates between grandeur and austerity, realism and abstraction, repression and rebellion.

In the early periods, Russian art was deeply religious, with icon painting dominating the artistic landscape for centuries. The influence of Byzantium was strong, as the adoption of Orthodox Christianity in 988 brought with it a rich tradition of sacred imagery. These early icons, with their rigid, spiritual compositions, defined Russian art for nearly a millennium. But as Russia expanded its empire and sought closer ties with Europe, artistic styles began to diversify.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, Russian art had absorbed Baroque, Neoclassical, and Romantic influences, producing grand imperial portraits, sweeping historical canvases, and the emergence of a uniquely Russian school of Realism. The Peredvizhniki (Wanderers), a group of rebellious painters, rejected academic constraints in favor of socially conscious themes, depicting the struggles of peasants, workers, and the poor.

The early 20th century saw Russia at the forefront of artistic innovation, with movements like Suprematism and Constructivism breaking away from traditional forms. Artists like Kazimir Malevich, Wassily Kandinsky, and Vladimir Tatlin pushed the boundaries of abstraction, influencing global modernism. However, this creative explosion was short-lived, as Stalin’s regime imposed Socialist Realism, a state-controlled aesthetic that glorified Soviet ideals and suppressed experimental art.

Despite Soviet-era censorship, underground art movements persisted, paving the way for a post-Soviet artistic renaissance in the 1990s and beyond. Today, Russian artists engage with contemporary themes, blending traditional techniques with digital media, performance, and conceptual art. The country’s artistic legacy remains one of reinvention—an ongoing dialogue between past and future, oppression and expression.

Early Slavic and Medieval Art

Before Russia became the vast empire known today, its artistic traditions were shaped by the beliefs and lifestyles of early Slavic tribes. These pre-Christian Slavs, living in what is now Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, practiced a form of nature worship, creating ritualistic objects, wooden idols, and intricate metalwork that reflected their animistic worldview. Much of this early art has been lost due to the transient nature of wood-based craftsmanship, but traces remain in archaeological finds, folk motifs, and later artistic traditions.

The most significant shift in Russian art occurred in 988, when Prince Vladimir of Kievan Rus adopted Eastern Orthodox Christianity from the Byzantine Empire. This momentous event introduced Byzantine artistic traditions to the Slavic world, radically transforming the region’s visual culture. Churches were erected, and religious imagery—particularly icons—became the dominant form of artistic expression.

The Importance of Icon Painting

Icons (from the Greek eikōn, meaning “image”) were sacred paintings depicting Christ, the Virgin Mary, saints, and biblical scenes. Unlike Western religious paintings, which evolved toward realism, Russian icons were highly stylized, emphasizing spiritual presence over physical accuracy. Figures were elongated, faces were solemn and otherworldly, and gold backgrounds symbolized divine light. These works were not meant to be mere representations; they were considered sacred windows into the divine realm, capable of performing miracles.

One of the earliest and most famous Russian icons is the Virgin of Vladimir (c. 1130), which exemplifies the tenderness and spiritual depth characteristic of Byzantine-influenced Russian iconography. This image of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child, with their faces pressed together in a gesture of divine compassion, set the standard for Russian religious painting.

The Architecture of Kievan Rus

In addition to painting, medieval Russian architecture flourished under Byzantine influence. The earliest churches, such as the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv (built in the 11th century), followed Byzantine models but incorporated uniquely Russian elements, including onion domes, which later became a hallmark of Russian architecture. The domes’ bulbous shapes were designed to withstand Russia’s harsh climate and were often gilded, creating dazzling spectacles in the sunlight.

Another prime example of medieval Russian architecture is the Cathedral of Saint Sophia in Novgorod, completed in the 11th century. This structure, with its austere stone walls and five silver domes, reflects the growing independence of Russian art from its Byzantine origins, moving toward a simpler, more monumental style.

The Mongol Invasion and Artistic Decline

The development of Russian art was severely disrupted in the 13th century by the Mongol invasion, which devastated Kievan Rus. Many cities were burned, churches were destroyed, and artistic production stagnated under Mongol rule. However, some artistic traditions survived, particularly in the northern regions like Novgorod and Pskov, where craftsmen continued to produce icons and frescoes.

It was in these isolated northern regions that Russian art began to take on a more distinctly Slavic character, blending Byzantine religious themes with local folk aesthetics. This fusion laid the groundwork for the golden age of Russian icon painting, which would reach its peak in the 15th century with the work of Andrei Rublev.

The Rise of Icon Painting

By the late medieval period, icon painting had become the dominant artistic tradition in Russia, deeply embedded in religious life and cultural identity. These sacred images adorned churches, homes, and even battle standards, believed to hold divine power and offer protection. While earlier Russian icons were heavily influenced by Byzantine prototypes, by the 14th and 15th centuries, a distinctly Russian style had emerged, characterized by greater emotional depth, softer color palettes, and a focus on spiritual transcendence.

Andrei Rublev: Master of Russian Iconography

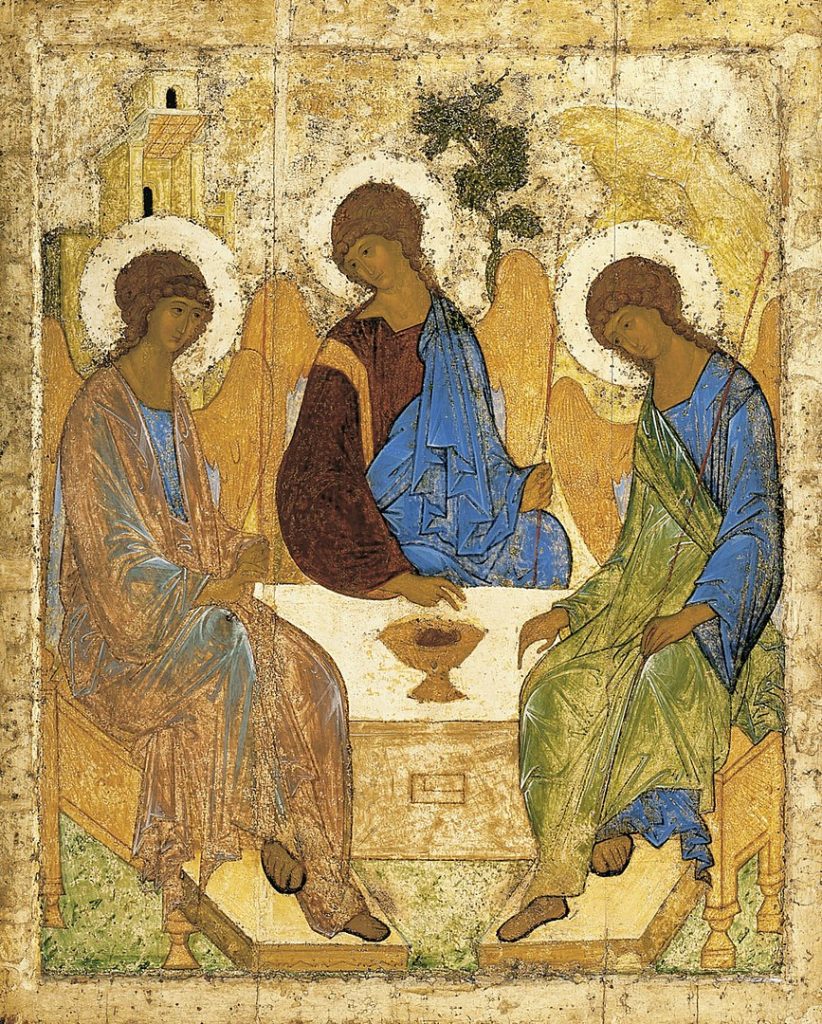

The pinnacle of Russian icon painting came with Andrei Rublev (c. 1360–1430), the most revered icon painter in Russian history. Rublev’s work epitomized the spiritual idealism of Russian Orthodoxy, emphasizing harmony, divine light, and an ethereal quality that set his icons apart from their Byzantine predecessors. His most famous work, The Trinity (c. 1411), remains one of the greatest achievements in religious art.

Rublev’s Trinity is a masterpiece of composition and symbolism. Depicting the three angels who appeared to Abraham in the Old Testament, the icon represents the unity of the Holy Trinity while embodying a sense of profound peace and spiritual contemplation. The figures are arranged in a perfect balance, their gazes forming an invisible circle that draws the viewer inward. The use of soft blues, golds, and warm earth tones enhances the painting’s dreamlike quality, reflecting the mystical nature of faith.

Rublev’s approach to iconography influenced generations of Russian painters, setting the standard for Orthodox religious art. His emphasis on gentleness, luminosity, and inner divinity distinguished Russian icons from their more rigid Byzantine counterparts.

The Iconostasis: A Visual Gateway to the Divine

During this period, the iconostasis—a massive screen of icons separating the nave from the sanctuary in Orthodox churches—became a central feature of Russian religious architecture. These towering icon walls, often gilded and ornately decorated, served both a practical and spiritual purpose, reinforcing the idea that icons were not merely decorative but sacred conduits between the human and divine realms.

One of the finest examples is the iconostasis of the Assumption Cathedral in the Kremlin, featuring rows of icons depicting Christ, the Virgin Mary, saints, and biblical events. These works were arranged in hierarchical order, with the most sacred figures at the top, reinforcing Orthodox theological principles through visual storytelling.

The Spread of Russian Icon Painting

Rublev’s legacy inspired a flourishing of icon workshops in Moscow, Novgorod, and Pskov. Each region developed its own stylistic traits:

- Novgorod icons were known for their bold, vibrant colors and expressive lines, reflecting the city’s relative independence from Mongol rule.

- Moscow icons followed Rublev’s style, emphasizing soft, harmonious compositions and a more meditative atmosphere.

- Pskov icons retained an earthy, folk-like quality, often featuring simplified forms and darker palettes.

By the 16th century, icon painting had become institutionalized, with artists working in large studios under royal and church patronage. However, as Russian rulers sought greater ties with Western Europe, new artistic influences began to challenge the dominance of traditional iconography.

Moscow Baroque and Imperial Art

As Russia transitioned from the medieval period into the early modern era, its art underwent a dramatic transformation. The 17th and 18th centuries saw the rise of Moscow Baroque, a style that blended traditional Russian iconography with Western European influences. However, the most radical shift came under Peter the Great (1682–1725), who sought to modernize Russia by embracing the artistic styles of France, Italy, and the Netherlands. This period marked the decline of purely religious art and the rise of secular painting, portraiture, and grand architectural projects.

The Moscow Baroque: A Bridge Between Old and New

Before Peter the Great’s reforms, Russian art was already evolving. The Moscow Baroque style emerged in the late 17th century, combining traditional Orthodox aesthetics with elements borrowed from Italian and Polish Baroque. This can be seen in the architecture of the Church of the Intercession at Fili (1690s), which features elaborate white stone carvings and richly ornamented interiors—a stark contrast to the austere medieval churches of earlier centuries.

Icon painting also adapted to the new aesthetic. Artists like Simon Ushakov (1626–1686) introduced realistic shading, soft facial expressions, and perspective, moving away from the rigid, symbolic style of Andrei Rublev. Ushakov’s The Savior Not Made by Hands (1658) showcases these Western-inspired techniques while maintaining the spiritual intensity of traditional iconography.

Peter the Great’s Artistic Revolution

Peter the Great’s reign marked the most radical shift in Russian art history. Determined to align Russia with the cultural and technological advancements of Western Europe, he abolished medieval artistic traditions, promoted secular art, and established St. Petersburg as a new, European-style capital.

One of Peter’s most significant acts was the creation of the Imperial Academy of Arts (1757), which trained Russian artists in the classical traditions of Italy and France. Under this new system, historical painting, portraiture, and landscape art flourished, replacing religious iconography as the dominant artistic form.

The Rise of Portraiture

The most visible result of Peter’s reforms was the rise of secular portraiture, which had been nearly nonexistent in Russia before the 18th century. Inspired by Dutch and French examples, Russian artists began painting lifelike images of the tsar, nobles, and military leaders.

- Ivan Nikitin (1680s–1740s), one of the first great Russian portraitists, painted strikingly realistic depictions of Peter the Great and his court. His Portrait of Chancellor Gavriil Golovkin (1720s) demonstrates the newfound attention to psychological depth and individual character.

- Later, Dmitry Levitsky (1735–1822) refined this tradition, producing elegant portraits of Catherine the Great and Russian aristocrats that rivaled the work of European masters.

St. Petersburg: A New Artistic Center

Under Peter the Great and his successors, St. Petersburg became the heart of Russian art and architecture, featuring grand palaces, sculptures, and neoclassical monuments.

- The Winter Palace, completed in 1762, is a masterpiece of Elizabethan Baroque, with lavish gold detailing, towering columns, and grand staircases.

- The Smolny Cathedral, designed by the Italian architect Francesco Bartolomeo Rastrelli, epitomizes the fusion of Russian tradition with European luxury.

As Russia moved further into the Age of Enlightenment, the groundwork was laid for the Romanticism and Realism movements of the 19th century, where Russian art would find its own distinct voice once again.

Romanticism and Realism: The Rise of the Peredvizhniki

As Russia entered the 19th century, its art scene underwent another dramatic shift. The influence of European Romanticism brought about a fascination with national identity, history, and the sublime beauty of the Russian landscape. However, by the mid-19th century, this gave way to a more grounded and socially engaged movement—Realism. At the forefront of this transformation was the Peredvizhniki, or “The Wanderers,” a group of radical artists who rejected academic constraints and sought to depict the harsh realities of Russian life.

The Influence of Romanticism in Russian Art

In the early 19th century, Russian artists, much like their European counterparts, embraced Romanticism, a movement that emphasized emotion, individualism, and the power of nature. The works of Karl Bryullov (1799–1852) and Orest Kiprensky (1782–1836) exemplify this period, blending dramatic compositions with a newfound focus on Russian subjects.

- Karl Bryullov’s masterpiece, The Last Day of Pompeii (1833), showcases a grand, theatrical composition reminiscent of French and Italian Romanticism. However, Bryullov also painted intimate, deeply expressive portraits, such as The Rider (1832), which conveyed the inner depth of his subjects.

- Orest Kiprensky, often considered Russia’s first true Romantic painter, captured the fiery spirit of his era in works like Portrait of Alexander Pushkin (1827), immortalizing the poet who would become a national icon.

Despite their accomplishments, these artists were still tied to the Imperial Academy’s traditional approach, which emphasized idealized historical subjects. But a new generation of painters sought a more honest, unfiltered depiction of Russian life—a shift that would culminate in the rise of Realism.

The Birth of Russian Realism and the Peredvizhniki Movement

By the 1860s, a growing dissatisfaction with the rigid academic traditions of the Imperial Academy led to the formation of the Peredvizhniki, or Wanderers—a group of artists who rejected state-controlled commissions in favor of independent, socially conscious art. Led by figures such as Ivan Kramskoi, Ilya Repin, Vasily Perov, and Isaac Levitan, they took their work “on the road,” organizing traveling exhibitions to bring art to the Russian people.

The Peredvizhniki believed that art should serve a moral and educational purpose, shedding light on the struggles of peasants, workers, and the oppressed. They painted gritty, unidealized scenes of everyday life, portraying the suffering, dignity, and resilience of ordinary Russians.

Key Works and Artists of the Peredvizhniki

- Ilya Repin (1844–1930) is widely regarded as the greatest of the Peredvizhniki. His Barge Haulers on the Volga (1873) is a powerful indictment of social inequality, depicting exhausted laborers struggling against the weight of their burdens. Repin’s work was deeply psychological, as seen in Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan (1885), a haunting portrayal of a tsar driven to madness.

- Vasily Perov (1834–1882) captured the struggles of the lower classes in works like The Drowned Woman (1867) and Troika (1866), emphasizing stark realism over sentimentality.

- Isaac Levitan (1860–1900) revolutionized Russian landscape painting with his deeply atmospheric depictions of nature. The Vladimirka Road (1892) is a poignant representation of exile and suffering, showing a desolate road that once led prisoners to Siberia.

The Peredvizhniki movement profoundly shaped Russian art, bridging the gap between Romantic idealism and the raw truths of Realism. Their influence would persist into the 20th century, laying the groundwork for both Soviet Socialist Realism and later avant-garde movements.

The Silver Age & Symbolism: Mysticism and Modernity in Russian Art

As the 19th century gave way to the 20th, Russian art entered one of its most enigmatic and experimental periods—the Silver Age. This era, roughly spanning from the 1890s to the early 1920s, saw a flourishing of Symbolism, Art Nouveau, and early modernist movements. Russian artists, poets, and intellectuals turned toward mysticism, fantasy, and spiritual exploration, rejecting the stark realism of the Peredvizhniki in favor of evocative, dreamlike imagery.

At the heart of this transformation was Symbolism, a movement that sought to express the unseen, the emotional, and the transcendent through allegory, mythology, and rich color symbolism. Russian Symbolist painters created works suffused with mystery, spirituality, and psychological depth, anticipating the avant-garde revolutions to come.

Mikhail Vrubel: The Visionary of Russian Symbolism

Few artists embody the mystical grandeur of the Silver Age more than Mikhail Vrubel (1856–1910). A painter, illustrator, and stage designer, Vrubel fused elements of Byzantine iconography, Russian folklore, and Symbolist abstraction, creating a highly unique and deeply expressive style.

His most famous works include:

- “The Demon Seated” (1890) – A haunting depiction of the melancholic, brooding figure from Mikhail Lermontov’s epic poem The Demon. The fractured brushstrokes and iridescent, jewel-like colors evoke an otherworldly atmosphere, reflecting Vrubel’s belief in art as a bridge between material and spiritual realms.

- “The Swan Princess” (1900) – Inspired by Russian fairy tales and Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera The Tale of Tsar Saltan, this ethereal portrait blends Symbolist mysticism with elements of Art Nouveau, particularly in its flowing lines and delicate luminosity.

Vrubel’s work was both celebrated and misunderstood in his time. His obsession with the mystical and the demonic, combined with his increasingly abstract techniques, set him apart from his contemporaries. Tragically, he suffered from severe mental illness in his later years, and his art became even more fragmented and visionary.

Art Nouveau and Russian Decorative Arts

Alongside Symbolist painting, the Art Nouveau movement (known in Russia as Stil’ Modern) transformed Russian architecture, design, and illustration. Characterized by flowing organic forms, intricate ornamentation, and a fascination with nature, Russian Art Nouveau was particularly influential in book illustration and theatrical design.

- Leon Bakst (1866–1924) and Alexandre Benois (1870–1960) revolutionized set and costume design for the Ballets Russes, infusing performances with exotic, dreamlike aesthetics that captivated audiences across Europe.

- Ivan Bilibin (1876–1942) created some of the most iconic illustrations of Russian folklore, blending traditional Slavic motifs with the curving lines and decorative elegance of Art Nouveau. His work remains a defining visual interpretation of Russian fairy tales.

The Transition to Early Modernism

By the early 1910s, the mystical Symbolism of the Silver Age began evolving toward the radical avant-garde movements that would soon dominate Russian art. Artists like Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin experimented with perspective and color theory, while others, like Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov, began pushing toward Futurism and Rayonism.

The Silver Age was ultimately cut short by the Russian Revolution (1917), which ushered in a new era of political upheaval and artistic experimentation. The mystical, introspective art of the Symbolists gave way to the bold abstraction of the Russian Avant-Garde, where painters like Kazimir Malevich and Wassily Kandinsky would take Russian art in an entirely new direction.

The Russian Avant-Garde (1910s–1920s): Revolutionizing Art

The early 20th century was a time of seismic change in Russian art. The Russian Avant-Garde—one of the most revolutionary movements in modern art history—emerged from the radical experiments of the Silver Age, breaking away from traditional forms in favor of abstraction, geometry, and bold new artistic theories. This movement coincided with the political upheaval of the Russian Revolution (1917), and many avant-garde artists saw their work as part of a broader effort to reshape society.

At the heart of the Russian Avant-Garde were two major movements: Suprematism and Constructivism. These styles sought to move beyond representation, embracing pure artistic expression and the idea that art could directly shape human perception and even social structures.

Suprematism: The Art of Pure Abstraction

Founded by Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935) in 1915, Suprematism was a radical movement that sought to liberate art from the constraints of representation. Malevich believed that art should be reduced to its purest forms—basic geometric shapes, limited colors, and complete detachment from the physical world.

His most famous work, “Black Square” (1915), is one of the most iconic paintings of the 20th century. A simple black square on a white background, the painting was intended as the ultimate rejection of narrative, symbolism, and realism. Malevich called it “the zero of form”—a new beginning for art.

Other key Suprematist works include:

- “White on White” (1918) – A nearly invisible composition that pushes abstraction to its limit, consisting of a white square set against a slightly different white background.

- “Suprematist Composition” (1916–1917) – A dynamic arrangement of geometric shapes floating in space, emphasizing movement and balance.

Suprematism was not just an artistic movement—it was a philosophy. Malevich believed that his non-objective art could free the human spirit from material concerns. However, as Soviet ideology became increasingly focused on utilitarian art, Suprematism was gradually sidelined in favor of Socialist Realism.

Constructivism: Art as a Tool for Society

While Suprematism was concerned with pure form, Constructivism—founded by Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953) and later developed by Alexander Rodchenko (1891–1956)—was an attempt to apply avant-garde aesthetics to real-world social and industrial concerns.

Constructivists believed that art should be practical, serving the needs of the new Soviet society. This philosophy led to the creation of revolutionary architecture, graphic design, and propaganda posters.

- Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International (1920) – A never-built, spiraling tower of steel and glass, designed as a symbol of Communist progress.

- Rodchenko’s Graphic Design – Rodchenko pioneered bold propaganda posters, using geometric forms, photomontage, and striking typography to convey Soviet ideals.

Constructivism influenced everything from fashion and furniture design to architecture and industrial production. It sought to dissolve the boundaries between art and everyday life, promoting a utopian vision of a socialist future.

The End of the Avant-Garde

Despite their revolutionary energy, the avant-garde movements faced increasing opposition in the late 1920s. Joseph Stalin’s rise to power led to the suppression of abstract art, which was seen as too “elitist” and disconnected from the common people. By the early 1930s, Socialist Realism became the official artistic style of the Soviet Union, forcing avant-garde artists into exile, silence, or conformity.

Although short-lived, the Russian Avant-Garde had an immense global impact. It influenced the Bauhaus movement in Germany, De Stijl in the Netherlands, and even American abstract expressionism decades later. Today, Suprematist and Constructivist works remain some of the most studied and celebrated pieces in modern art history.

Soviet Art and Socialist Realism: The Art of Propaganda (1930s–1950s)

As the Soviet Union solidified its control under Joseph Stalin, the bold experimentation of the Russian Avant-Garde was cast aside in favor of a new state-mandated style: Socialist Realism. This official artistic doctrine, established in the 1930s, demanded that all art serve the ideological goals of the Communist Party, glorifying the working class, the state, and Soviet leadership.

Gone were the abstract forms of Malevich and Tatlin—instead, Soviet art was dominated by heroic depictions of workers, farmers, and soldiers, painted in a realistic, optimistic, and highly idealized style. Art became a tool for propaganda, used to shape public perception and instill loyalty to the state.

The Principles of Socialist Realism

Socialist Realism was not merely a style but a state-enforced artistic doctrine, defined by the following principles:

- Idealization of the Soviet Citizen – Art depicted workers, farmers, and soldiers as strong, noble, and heroic, often shown in uplifting and triumphant poses.

- Glorification of Soviet Leadership – Paintings and sculptures celebrated figures like Lenin, Stalin, and other Communist leaders, portraying them as benevolent visionaries.

- Optimistic and Uplifting Imagery – There was no place for suffering, hardship, or criticism; instead, art was meant to convey a bright Soviet future where Communism was victorious.

- Realistic, Clear, and Accessible – Unlike the abstraction of the avant-garde, Socialist Realist art had to be easy to understand, making it accessible to the masses.

Key Artists and Works of Socialist Realism

- Isaak Brodsky (1883–1939) was one of the leading Socialist Realist painters. His “Lenin in Smolny” (1930) is a quintessential example, depicting Lenin as a calm, intelligent leader working tirelessly for the revolution.

- Alexander Deineka (1899–1969) focused on industrial progress and the Soviet workforce, producing dynamic compositions like “The Defense of Petrograd” (1928), which showed soldiers and workers marching together in unity.

- Vera Mukhina (1889–1953) created one of the most famous Soviet sculptures, “Worker and Kolkhoz Woman” (1937)—a monumental statue of a male worker and a female collective farmer striding forward together, holding a hammer and sickle.

Soviet Art as a Political Weapon

Under Stalin’s rule, art was tightly controlled, and deviation from Socialist Realism was met with harsh consequences. Avant-garde artists were either forced to conform or silenced. Many were labeled as “bourgeois formalists” and blacklisted, imprisoned, or even executed.

Censorship extended beyond painting and sculpture to film, literature, and theater. Sergei Eisenstein, the celebrated filmmaker behind Battleship Potemkin (1925), had to navigate strict ideological constraints in his later works to avoid political repercussions.

The Role of Socialist Realism in Soviet Propaganda

Socialist Realism was not just about paintings and statues—it permeated every aspect of Soviet visual culture, including:

- Posters and propaganda – Striking images encouraged people to work harder, fight for the state, and glorify Soviet leaders.

- Murals and mosaics – Public buildings were adorned with idealized scenes of Soviet industry, agriculture, and military victories.

- Soviet architecture – Buildings like Moscow’s Seven Sisters (Stalinist skyscrapers) embodied the monumentalism and grandeur of Socialist ideals.

The Decline of Socialist Realism

After Stalin’s death in 1953, the rigid constraints of Socialist Realism began to loosen. Under Nikita Khrushchev’s “Thaw” (1950s–1960s), artists were given slightly more creative freedom, leading to the emergence of Nonconformist and Underground Art movements. However, Socialist Realism remained the dominant state-approved style well into the 1980s.

While many dismissed Socialist Realism as forced propaganda, it remains an important chapter in Russian art history. It demonstrated the power of art as a political tool, but it also led to stagnation, suppressing artistic individuality in favor of state control.

The Thaw and Nonconformist Art: Breaking Free from Socialist Realism (1950s–1980s)

With Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953, the rigid artistic controls of Socialist Realism began to loosen. Under Nikita Khrushchev’s “Thaw” (1950s–1960s), Soviet society saw a brief period of cultural relaxation, allowing artists to explore new themes, techniques, and even limited forms of abstraction. However, this newfound freedom was short-lived. By the late 1960s, artistic repression returned under Leonid Brezhnev, forcing many avant-garde and dissident artists to work underground.

This period saw the rise of Nonconformist Art, a broad term for Soviet artists who rejected state-imposed artistic norms. These artists experimented with abstraction, conceptualism, and political satire, often at great personal risk. Their work laid the foundation for the post-Soviet art movements of the 1990s and beyond.

The Khrushchev Thaw: A Taste of Freedom

Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization policies (1956) allowed for a slight loosening of artistic restrictions. While Socialist Realism remained the official style, artists were permitted to explore more expressive, psychological, and experimental techniques—as long as their work did not directly criticize the Soviet system.

Some key artists of this period include:

- Alexander Deyneka (1899–1969), a former Socialist Realist, began introducing dynamic movement and modernist influences into his depictions of Soviet life.

- Gelii Korzhev (1925–2012) created searing psychological portraits, such as his “Scorched by the Sun” (1957–1960), reflecting the emotional toll of war and repression.

- Tair Salakhov (1928–2021) explored the gritty reality of Soviet workers, moving away from idealized depictions.

Khrushchev’s Attack on Modern Art

Despite the slight artistic liberalization, Khrushchev was personally hostile to abstract and experimental art. This became clear in 1962 when he visited the “30 Years of Moscow Art” exhibition, where he publicly ridiculed abstract and nontraditional paintings, calling them “dog shit” and “degenerate art.”

His outburst signaled that full artistic freedom was still impossible, leading to a cultural crackdown in the later years of his rule.

The Rise of Underground and Nonconformist Art

As Leonid Brezhnev took power in 1964, the Soviet Union entered a period known as the Brezhnev Stagnation (1964–1982). Cultural repression intensified, forcing many artists to work outside official state channels.

These underground artists formed what became known as Nonconformist or “Unofficial” Art. Their works were never exhibited in state galleries but were secretly shown in private apartments, unofficial spaces, or even smuggled abroad.

Some of the most important Nonconformist artists include:

- Oskar Rabin (1928–2018) – Used collage and expressive brushwork to depict the grim realities of Soviet life, often incorporating banned imagery like crosses and religious symbols.

- Erik Bulatov (b. 1933) – Created striking conceptual works blending Soviet propaganda slogans with surreal landscapes.

- Ilya Kabakov (b. 1933) – A pioneer of Soviet conceptualism, he created ironic installations about the absurdity of Soviet bureaucracy.

The Bulldozer Exhibition (1974): A Turning Point

One of the most dramatic moments in Soviet Nonconformist Art occurred in 1974, when a group of artists attempted to hold an independent open-air exhibition in a Moscow field. The Soviet authorities sent bulldozers and water cannons to destroy the artwork, violently dispersing the crowd.

This event, known as the “Bulldozer Exhibition”, exposed the Soviet government’s intolerance for artistic dissent to the international community. As a result, some Nonconformist artists were later allowed to exhibit their work in state galleries—though still under tight censorship.

The Late Soviet Period: Art on the Edge of Change

By the 1980s, under Mikhail Gorbachev’s policies of Glasnost (openness) and Perestroika (restructuring), artistic repression eased. Galleries cautiously began exhibiting underground works, and Soviet artists gained more exposure to Western influences.

This period marked the transition into the Post-Soviet Art Scene, where Russian artists would finally gain full creative freedom after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Contemporary Russian Art: Post-Soviet Expression in a Globalized World (1991–Present)

With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russian artists were finally freed from state control, entering a period of unprecedented creative freedom. This transition, however, was not smooth. The 1990s were marked by economic instability, political uncertainty, and cultural fragmentation, all of which deeply influenced Russian art.

For the first time in decades, Russian artists could fully engage with international movements, experiment with new media, and openly critique the social and political landscape. Contemporary Russian art is characterized by a blend of traditional influences, post-Soviet identity struggles, and global artistic trends.

The 1990s: Chaos and Reinvention

The immediate post-Soviet years were a period of radical artistic reinvention. With the collapse of government funding for the arts, many artists struggled financially, but this also led to a wave of independent and underground creativity.

Some key trends of the 1990s include:

- Conceptual and Performance Art – Artists like Oleg Kulik became known for provocative performances, such as his famous “dog act,” where he lived as a dog to symbolize Russia’s identity crisis.

- Political and Satirical Art – The group AES+F created bold, surreal imagery that critiqued consumerism, war, and Russian society’s transition to capitalism.

- Graffiti and Street Art – The collapse of the Soviet Union saw an explosion of urban and street art, influenced by Western graffiti movements.

Despite the artistic freedom, the 1990s were a financially challenging time for Russian artists. Many left the country or struggled to find an audience in the chaotic post-Soviet economy.

The 2000s: Globalization and New Media

By the early 2000s, Russia’s economy stabilized under Vladimir Putin, and Russian artists gained greater access to global networks, museums, and biennales. Art markets flourished, and Russian artists began gaining international recognition.

Some defining aspects of the 2000s:

- Multimedia and Digital Art – Artists like Dmitry Gutov and Olga Chernysheva explored video, installation, and digital media, reflecting the growing role of technology in Russian society.

- Reinterpretation of Soviet Aesthetics – Many artists began revisiting and deconstructing Soviet imagery, using irony and nostalgia to explore its meaning in the modern world.

- Rise of Private Art Institutions – Museums like Garage Museum of Contemporary Art (founded by Dasha Zhukova in 2008) provided new spaces for experimental and independent artists.

Political and Protest Art in the 2010s

While the 2000s saw a relative boom in Russian contemporary art, the 2010s were marked by increasing state control, censorship, and political repression. This led to the rise of protest art, with artists using their work to challenge government policies, human rights violations, and authoritarianism.

Some of the most well-known examples of political Russian art:

- Pussy Riot (founded in 2011) – The feminist punk collective used performance art and music to protest political oppression, most famously in their 2012 “Punk Prayer” at Moscow’s Christ the Savior Cathedral, which led to the imprisonment of several members.

- Pyotr Pavlensky – Known for his extreme body performance art, including sewing his mouth shut and nailing his scrotum to Red Square as a protest against state repression.

- Blue Noses Art Group – A satirical collective that used humor and absurdity to criticize Russian politics and corruption.

The 2020s: Art in an Era of Uncertainty

The 2020s have been a challenging time for Russian artists, with increasing censorship, political crackdowns, and international isolation due to geopolitical conflicts. Many artists have been forced into self-censorship, exile, or underground movements.

However, despite these obstacles, contemporary Russian art continues to thrive in new forms:

- AI and Digital Art – Russian artists are increasingly exploring NFTs, AI-generated art, and virtual reality as new frontiers of expression.

- Diaspora and Exiled Artists – Many Russian artists have left the country and are now creating powerful work from Europe, the U.S., and beyond, exploring themes of identity, exile, and resistance.

Conclusion: Russian Art as a Story of Resilience

From Byzantine icons to avant-garde experiments, from Soviet propaganda to underground rebellion, Russian art has continually evolved, responding to the shifting tides of history. Whether under tsarist autocracy, Soviet control, or modern political challenges, Russian artists have found ways to express, resist, and innovate.

Today, Russian art stands at a crossroads. Political repression and global isolation have made it more difficult for artists to work freely, yet the spirit of creativity, defiance, and reinvention remains. Whether within Russia or in the global diaspora, Russian artists continue to shape the future of contemporary art, proving that no system can fully silence artistic expression.