Strasbourg is a city unlike any other in Europe — a vibrant tapestry woven from centuries of cultural exchange, political upheaval, and artistic innovation. Situated on the banks of the Rhine, Strasbourg’s very geography has made it a perpetual meeting ground: between Latin and Germanic cultures, between Catholicism and Protestantism, between tradition and revolution. Its art history, much like its political fate, is a story of fusion and transformation, where each era left a distinct mark on the city’s aesthetic soul.

First mentioned by the Romans as Argentoratum in the first century BCE, Strasbourg’s origins were military and pragmatic. But even in its earliest days, life on the frontier of the Roman Empire exposed it to a confluence of artistic influences, from Roman mosaics to local Gallic crafts. Over time, the modest outpost evolved into a powerful free city within the Holy Roman Empire, its prosperity manifesting in one of the crowning achievements of Gothic architecture: the Strasbourg Cathedral.

Throughout the Middle Ages, Strasbourg became an important center for craftsmanship, manuscript illumination, and later, the burgeoning industry of printing. Gutenberg himself worked in Strasbourg during the development of movable type, an invention that would democratize knowledge and drastically impact artistic production across Europe. Here, too, the Reformation took hold early and fervently, coloring not just religious life but visual culture — simplifying ecclesiastical art and promoting new forms of expression.

If Strasbourg’s medieval and Renaissance achievements reflected its prominence within the German-speaking world, its later history mirrored the volatile Franco-German struggle for dominance. After centuries of relative independence, Strasbourg fell under French control in 1681, becoming a symbol of Louis XIV’s expansionist ambitions. French rule brought Baroque and Rococo flourishes to the cityscape, superimposing new artistic styles atop Gothic foundations. Yet even as political allegiances shifted, Strasbourg’s identity remained stubbornly hybrid: Germanic traditions persisted in architecture, painting, and folk art.

The French Revolution ushered in a period of iconoclasm and upheaval, but it also paved the way for a rebirth. The 19th century saw Strasbourg reimagine itself yet again, embracing Romantic nationalism and fostering a renewed interest in regional culture. This was the era of historical painting, of grand public monuments celebrating both French unity and Alsatian uniqueness.

Strasbourg’s art history cannot be told without addressing the scars of conflict — particularly the Franco-Prussian War, World War I, and World War II — each of which left the city politically and culturally fragmented. Yet each rupture was followed by remarkable cultural resilience. In the 20th century, Strasbourg emerged as a beacon of European cooperation, home to the Council of Europe and the European Parliament. This new role was reflected in its art, which became increasingly cosmopolitan, experimental, and forward-looking.

Today, Strasbourg is celebrated not only for its medieval wonders but also for its vibrant contemporary art scene, its world-class museums, and its dynamic cultural festivals. It is a city where the past and present coexist gracefully, where Gothic spires shadow sleek modernist installations, and where art continues to serve as a powerful language of identity, memory, and hope.

As we embark on a deep exploration of Strasbourg’s artistic evolution, from Roman mosaics to avant-garde installations, one truth will become clear: Strasbourg’s art is, above all, a testament to the power of place — a crossroads where history flows not as a straight line but as a rich, ever-changing current.

Roman Roots and Early Artistic Heritage

Long before Strasbourg became a medieval powerhouse or a modern European capital, it began as a strategic Roman outpost known as Argentoratum. Founded around 12 BCE by Nero Claudius Drusus, the stepson of Emperor Augustus, this small military settlement was one of many along the Rhine frontier, part of Rome’s vast network of border defenses. Yet even in its infancy, Argentoratum was more than a simple garrison: it was a place where Roman civilization met the wildness of the northern frontiers — a point of exchange, adaptation, and hybridization that would foreshadow the city’s complex artistic future.

Roman art was, at its core, an expression of imperial power, cultural aspiration, and religious devotion. The traces left behind in Strasbourg show that even a provincial settlement participated in this wider artistic language. Archaeological excavations throughout the city, particularly beneath Place Kléber and along the riverbanks, have unearthed a fascinating array of Roman artifacts: mosaic floors, fragments of statuary, coins, ceramics, and architectural remnants. These objects, while often modest compared to the grandeur of Rome itself, reveal a surprising level of sophistication and suggest that even the distant outposts of the empire were tied into a larger aesthetic and ideological system.

One of the most significant discoveries is the series of mosaic floors found beneath modern Strasbourg. These mosaics, composed of small tesserae of stone and glass, depicted geometric patterns, floral motifs, and occasionally mythological scenes. While none rival the complexity of mosaics from Roman North Africa or Italy, they nonetheless illustrate a localized interpretation of Mediterranean artistic conventions. The craftsmanship suggests the presence of trained artisans or at least access to Roman models and techniques, likely transmitted along the vital trade routes that threaded through the empire.

Religious art also played a crucial role in Argentoratum. Small altars and votive inscriptions dedicated to Roman gods such as Jupiter, Mars, and Minerva have been found, often blending traditional Roman imagery with local, sometimes Celtic, iconography. For instance, some depictions of deities incorporate elements foreign to classical Roman art, such as local animal symbols or stylized representations of nature, indicating an early form of syncretism — a blending of religious and artistic traditions that would become a recurring theme in Strasbourg’s history.

Military art, too, made its presence felt. Reliefs depicting legionary standards, triumphal scenes, and martial deities would have adorned public spaces, serving both decorative and propagandistic functions. Soldiers stationed in Argentoratum were not just warriors; they were carriers of Roman culture, commissioning statues, participating in local construction projects, and patronizing the arts.

Life in Roman Strasbourg, however, was precarious. The settlement faced repeated invasions by Germanic tribes, culminating in a devastating sack by the Alemanni in 357 CE, during which the Roman army suffered a significant defeat at the Battle of Argentoratum. This instability had a profound impact on the artistic record: many structures were abandoned, repurposed, or buried beneath new layers of occupation. Yet even through periods of destruction, the Roman artistic legacy endured — quite literally, as medieval builders would later repurpose Roman stones and foundations for new structures, embedding the classical past into the very fabric of the evolving city.

Perhaps most intriguingly, the Roman influence on Strasbourg’s art was not one of simple inheritance but of creative adaptation. Unlike cities that sought to perfectly replicate Roman models, Argentoratum’s art reflects a dialogue between imperial ideals and local realities. Its mosaics, temples, and everyday objects stand as early testaments to Strasbourg’s future character: a city where multiple identities, traditions, and artistic languages could coexist, sometimes uneasily, but often beautifully.

As the Western Roman Empire crumbled in the 5th century, Argentoratum — by then simply known as Strateburgum — transitioned into a new era. The structures of Roman authority disintegrated, but the artistic and cultural seeds planted during centuries of Roman rule continued to influence the emerging medieval society. The Roman stones remained, buried but not forgotten, ready to be built upon — quite literally — as Strasbourg moved toward its destiny as a medieval and modern artistic hub.

The Birth of Gothic Splendor: Strasbourg Cathedral and Medieval Art

If the Roman roots of Strasbourg laid the city’s foundations, it was the Middle Ages that gave it its soaring soul. And nothing embodies this transformation more vividly than the Strasbourg Cathedral — a monumental testament to faith, ambition, and artistic ingenuity. Towering over the city like a stone sentinel, the cathedral is not merely a building; it is a living chronicle of Strasbourg’s ascent as a cultural and spiritual powerhouse in medieval Europe.

The story of Strasbourg Cathedral (Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Strasbourg) begins in the early 11th century, during a period of burgeoning urban prosperity. The first Romanesque cathedral on the site, initiated by Bishop Werner von Habsburg around 1015, reflected the dominant style of the time: heavy, earthbound structures with rounded arches and thick walls. This early construction already set Strasbourg apart, boasting a scale and grandeur unusual for the region. However, fire ravaged the original Romanesque structure in 1176, providing a canvas for something even more extraordinary.

By the late 12th century, the Gothic style — born in the Île-de-France with the Abbey of Saint-Denis — had begun to spread across Europe. In Strasbourg, local and foreign artisans embraced and reinterpreted Gothic principles with stunning originality. The new cathedral project, launched shortly after the fire, reflected not only theological shifts emphasizing light and height as metaphors for divine presence but also the city’s growing wealth and competitive spirit. Strasbourg, a Free City of the Holy Roman Empire, was eager to demonstrate its importance, and nothing declared civic pride like a cathedral that touched the heavens.

Under the masterful hands of architects such as Erwin von Steinbach, construction flourished through the 13th and 14th centuries. Erwin is often credited with designing the celebrated western façade — a vertiginous tapestry of intricate stonework that still dazzles today. Here, the Gothic aesthetic reaches a rarefied perfection: soaring vertical lines, pointed arches, delicate tracery, and an overwhelming abundance of sculptural detail. Yet, despite its grandeur, the façade maintains a sense of ethereal lightness, as if the stone itself aspired to transcend its material nature.

The cathedral’s south tower, completed in 1439, became the tallest structure in Christendom at the time, a record it held for centuries. Its singular spire, rather than the more typical symmetrical twin towers, gives Strasbourg Cathedral its instantly recognizable silhouette. This architectural decision was not merely practical — funding shortages curtailed the second tower — but it also imbued the cathedral with a dynamic, almost dramatic character, emphasizing aspiration over symmetry.

The cathedral’s interior is equally breathtaking, though less ostentatious than the exterior. Bathed in shifting, colorful light from its magnificent stained glass windows — many of which date from the 12th to 14th centuries — the nave and choir exude a solemn majesty. The windows, masterpieces of medieval craftsmanship, depict biblical scenes, saints, and intricate geometric patterns, weaving narratives for an illiterate populace whose spiritual understanding was mediated through images.

Of particular note is the astronomical clock, a Renaissance marvel installed in the 16th century but housed in the cathedral’s medieval shell. This complex mechanical wonder reflects Strasbourg’s later role as a center of scientific and artistic innovation — a topic we will explore more fully in a later section.

Beyond the cathedral itself, Strasbourg’s medieval artistic life flourished in the surrounding city. The Maison Kammerzell, a stunning example of late Gothic civic architecture near the cathedral square, showcases intricate wood carvings and painted decorations that blend Gothic tradition with early Renaissance humanism. The city’s guilds — powerful associations of craftsmen, merchants, and artists — played a vital role in commissioning public works, adorning squares, and fostering a rich visual culture that extended beyond religious devotion into everyday life.

Religious art was omnipresent. Sculptures of saints adorned public fountains and marketplaces. Illuminated manuscripts, produced by monastic and later secular scriptoria, reflected Strasbourg’s intellectual vitality. The famed Hortus Deliciarum, an illuminated encyclopedia created by Herrad of Landsberg in the 12th century at the nearby Mont Sainte-Odile Abbey, stands as one of the most remarkable works of medieval Alsatian art, even though it was tragically destroyed during the Siege of Strasbourg in 1870. Surviving copies and reconstructions testify to its sophisticated synthesis of text and image, learning and devotion.

Meanwhile, Strasbourg’s strategic location along key trade routes ensured exposure to a broad range of influences: Germanic, French, Flemish, and Italian. This cosmopolitanism enriched its artistic vocabulary, fostering a distinctive regional style that prized intricate detail, emotional expressiveness, and technical mastery.

Yet the medieval era was not without its shadows. The Black Death, waves of anti-Jewish violence, and periodic political turmoil all left their mark. Strasbourg’s Jewish community, among the oldest in Europe, suffered devastating pogroms in 1349, an event that decimated a vibrant culture that had also contributed significantly to the city’s artistic and intellectual life.

By the dawn of the 15th century, Strasbourg had firmly established itself as a city where art, faith, and civic identity intertwined inextricably. The Gothic cathedral, standing proudly against the sky, symbolized not only religious devotion but also the collective aspirations of a community that saw itself as part of a divine, cosmic order — yet one increasingly aware of its own agency and creative power.

This dynamic tension between tradition and innovation, between collective memory and individual expression, would continue to shape Strasbourg’s artistic journey, propelling it into the dazzling transformations of the Renaissance.

Illuminated Manuscripts and the Strasbourg Scriptorium

In an age when the written word was as precious as gold, Strasbourg emerged as a luminous center for the production of illuminated manuscripts. Before the invention of movable type, books were handmade objects — intricate, labor-intensive artifacts that combined textual knowledge with dazzling visual artistry. In medieval Strasbourg, the scriptorium — both in monastic settings and, increasingly, in secular workshops — was a crucible of creativity, where theology, science, and aesthetics blended on shimmering pages of vellum.

The practice of manuscript illumination in Strasbourg dates back at least to the Carolingian Renaissance of the 9th century, when Charlemagne’s efforts to revive classical learning reached deep into the region. Monasteries like the Abbey of Honau and later the more prominent Mont Sainte-Odile Abbey became centers of scriptural and artistic production. Early works from this period reveal a strong influence of Carolingian styles: clear, Romanesque lettering, restrained but elegant ornamentation, and a commitment to transmitting classical knowledge through Christian lenses.

However, it was in the High Middle Ages, particularly the 12th and 13th centuries, that Strasbourg’s manuscript tradition truly flourished. The increasing wealth of the city, combined with its strategic position between the Latin and Germanic worlds, fostered a unique environment where intellectual and artistic currents from Paris, Cologne, and even Lombardy met and mingled.

One of the most significant achievements of this era was the Hortus Deliciarum (The Garden of Delights), created by Herrad of Landsberg, abbess of Hohenbourg (Mont Sainte-Odile). Compiled between 1167 and 1185, this encyclopedic manuscript was intended as an educational guide for nuns, blending theological, philosophical, and scientific knowledge with an astonishing richness of illustration. The Hortus Deliciarum contained over 600 miniatures: scenes from the Bible, allegorical diagrams, personifications of virtues and vices, and even depictions of contemporary monastic life.

Herrad’s manuscript represents more than just a teaching tool — it is an extraordinary window into the intellectual life of medieval Strasbourg and a rare example of a woman-led artistic project in an era dominated by male scribes and illuminators. Tragically, the original was destroyed during the Siege of Strasbourg in 1870, when fire consumed the municipal library where it was housed. Yet thanks to 19th-century facsimiles and detailed studies, much of its visual and textual content survives, continuing to inspire scholars and artists alike.

Strasbourg’s scriptoria — particularly those attached to its ecclesiastical institutions — produced a wide range of manuscripts beyond theological works. Legal codes, medical treatises, astronomical charts, and chronicles all received careful, often elaborate, treatment. The blend of functionality and beauty was essential: a manuscript was not merely a container of information but a sacred object, its ornamentation an offering to God and a reflection of divine order.

The artistic techniques employed by Strasbourg illuminators were sophisticated. Vellum prepared from calfskin provided a smooth, durable surface. Gold leaf, painstakingly applied, created radiant backgrounds and emphasized key figures. Pigments derived from rare minerals like lapis lazuli (for deep blues) or ground malachite (for greens) offered vivid colors that have survived centuries. Stylized vinework, fantastical creatures, and marginalia — sometimes serious, sometimes delightfully whimsical — adorned the pages, creating layered texts where meaning and beauty intertwined.

Interestingly, Strasbourg’s manuscripts exhibit a stylistic versatility that reflects the city’s cosmopolitan nature. Some works, particularly earlier ones, show the influence of Ottonian art from Germany: bold outlines, hierarchical compositions, and monumental figures. Others reveal a more French Gothic sensibility, with flowing lines, delicate gestures, and an emphasis on naturalistic details. This cross-fertilization would continue to define Strasbourg’s artistic character for centuries.

By the late 14th century, secular workshops began to rival monastic scriptoria in importance. Professional illuminators, often organized into guilds, catered to an increasingly diverse clientele — not only clergy and scholars but wealthy merchants and civic officials. Books of Hours, personal prayer books lavishly decorated with miniature paintings, became particularly popular among the laity, offering a more intimate form of devotion while serving as status symbols.

One notable figure emerging from this milieu was Diebold Lauber of Haguenau, a town just north of Strasbourg. In the early 15th century, Lauber operated what some scholars have called a “manuscript publishing house,” producing numerous illustrated texts aimed at a broader, increasingly literate public. While not based directly in Strasbourg, Lauber’s innovations reflect the region’s broader transition toward a more commercialized, secularized production of art — a development that would accelerate dramatically with the invention of printing.

Indeed, Strasbourg’s vibrant manuscript culture laid essential groundwork for the technological revolution on the horizon. Artists, scribes, and illuminators who had honed their skills illuminating manuscripts would find new opportunities — and new challenges — in the era of the printed book, which Strasbourg would help pioneer in Europe.

As we turn to the next chapter of Strasbourg’s art history, we will see how the profound traditions of illumination, storytelling, and visual craftsmanship evolved into a revolutionary force that reshaped not only art but society itself.

Renaissance Influences: Humanism and Print Culture

As the embers of the medieval world began to cool, Strasbourg found itself at the heart of a new fire: the Renaissance. But in Strasbourg, the Renaissance did not arrive in the same flamboyant form as it did in Italy; instead, it unfolded with a quieter, deeply intellectual fervor, shaped by Humanism, technological innovation, and a restless spirit of reform. Central to this transformation was the rise of print culture — and Strasbourg would play a pivotal role in that world-altering revolution.

The Renaissance, broadly speaking, was a rebirth of classical learning, a rediscovery of ancient Greek and Roman texts, and a renewed emphasis on human potential and reason. In the German-speaking lands, this took on a particular character: a scholarly, religious, and philosophical movement closely tied to the emerging forces of Protestantism. Strasbourg’s geographic and cultural position — poised between the Latin south and the Germanic north — made it an ideal incubator for this new way of thinking.

By the early 15th century, Strasbourg was already a prosperous, cosmopolitan city, its guilds powerful, its university thriving, and its merchant class hungry for knowledge and innovation. Into this fertile ground fell one of the most important seeds of the Renaissance: movable type printing. While Johannes Gutenberg would gain lasting fame for perfecting the technology in nearby Mainz, his early experiments occurred in Strasbourg, where he lived and worked during the 1430s and 1440s. Legal records from the city even mention a “venture in printing” associated with Gutenberg before his historic Bible project.

The impact of printing on Strasbourg’s artistic and cultural life was nothing short of seismic. Before movable type, books were precious, rare, and laboriously hand-copied — accessible only to the elite. Now, ideas could be reproduced rapidly, disseminated widely, and consumed by an ever-growing literate public. Art and text, previously confined to illuminated manuscripts, became democratized.

Strasbourg’s first major printer was Johann Mentelin, who established a press in the 1450s. His crowning achievement was the Mentelin Bible, printed around 1460 — one of the earliest German-language Bibles and a landmark in vernacular publishing. Unlike earlier illuminated manuscripts, Mentelin’s Bible relied on blackletter type: a bold, ornate script that preserved the aesthetic of medieval calligraphy while enabling mass production. The visual dimension of printed books remained crucial; printers like Mentelin and later figures such as Martin Schott and Johann Grüninger employed woodcut artists to embellish their volumes with illustrations, decorative initials, and title page designs.

These woodcuts were not merely decorative; they served as essential narrative tools, especially in religious texts, where they guided readers visually through complex theological concepts. Artists adapted medieval traditions of manuscript illumination to the new medium, creating a hybrid art form that married Gothic visual sensibilities with Renaissance humanist ideals.

One of Strasbourg’s most remarkable contributions to Renaissance art was its early embrace of satirical and moralizing imagery. The city’s printers produced broadsheets and pamphlets filled with allegorical woodcuts, poking fun at corruption, vice, and folly. This visual satire, often rooted in a moralizing Christian ethos, reflected the broader currents of reform that were beginning to sweep through Europe.

Perhaps the most famous example of this trend is the Ship of Fools (Das Narrenschiff), first published in Basel in 1494 but widely disseminated in Strasbourg and deeply influential there. Written by Sebastian Brant, a Strasbourg native, Ship of Fools was a biting allegory criticizing the moral decay of society, and it featured dozens of vivid woodcut illustrations, some attributed to a young Albrecht Dürer. These images captured the spirit of the Northern Renaissance: a blend of grotesque humor, moral seriousness, and extraordinary artistic skill.

Strasbourg’s printers and artists were not isolated artisans; they were part of an expansive network that connected them to Italy, the Low Countries, and beyond. They imported and adapted Renaissance ideas about proportion, perspective, and classical antiquity, blending them with their own Gothic inheritance. The result was a visual culture that was both distinctly Alsatian and unmistakably modern.

Architecturally, the Renaissance left its subtle mark on Strasbourg as well. Although the city retained much of its medieval character, some new buildings incorporated Renaissance elements: symmetrical facades, classical columns, and decorative motifs inspired by Roman antiquity. The Maison des Tanneurs (Tanners’ House) and parts of the Palais Rohan show the cautious, graceful integration of Renaissance principles into Strasbourg’s urban fabric.

Yet perhaps the most profound impact of the Renaissance on Strasbourg was ideological. Humanist scholars such as Jakob Wimpfeling and Johannes Sturm, both connected to Strasbourg, emphasized education, civic responsibility, and moral reform. Sturm would later found the Gymnasium Argentinense, a humanist school that became one of the leading educational institutions in Europe. Art and education, printing and politics — all these realms converged in Strasbourg, making it a beacon of early modern thought.

As the 16th century dawned, the city stood on the brink of another dramatic transformation. The seeds of Protestantism, nourished by Humanist critique and fueled by the power of the press, were about to erupt into full flower — and Strasbourg’s art would once again change, reflecting the profound spiritual and social upheavals of the Reformation.

Baroque and Rococo: Shifting Tastes in a Changing City

By the 17th century, Strasbourg found itself facing a dramatic new chapter in its history — and its art. The city, long proud of its status as a Free City within the Holy Roman Empire, was forcibly annexed by France under Louis XIV in 1681. This political shift was not merely administrative; it brought a profound cultural transformation that rippled through Strasbourg’s architecture, painting, sculpture, and decorative arts. The austere forms and moral certainties of the Reformation era gave way to the lavish exuberance of the Baroque — and later, the playful elegance of the Rococo.

The French annexation initially met with considerable resistance, both political and cultural. Strasbourg had been a bastion of Protestantism and a hub of Germanic culture. Now it was being absorbed into the absolutist orbit of Versailles, where art was not simply a matter of taste but an instrument of royal power. Louis XIV understood better than most the capacity of spectacle to solidify authority, and under his rule, Strasbourg was subtly but steadily reshaped to reflect the aesthetic ideals of the French Baroque.

One of the most visible manifestations of this shift was the construction of the Palais Rohan, built between 1732 and 1742 under the supervision of Robert de Cotte, the chief architect of the king. Commissioned by Cardinal Armand Gaston de Rohan, the palace was intended to serve as a residence for the prince-bishops of Strasbourg. Its design — austere yet monumental on the exterior, richly ornate within — exemplifies the classical French Baroque style. Grand reception rooms, sweeping staircases, gilded boiseries (wood paneling), and opulent ceiling paintings all conveyed a clear message: Strasbourg was now a city of the king.

Inside the Palais Rohan, visitors today can still glimpse the full flowering of Baroque and Rococo aesthetics. The apartments are adorned with intricate stucco work, luxurious tapestries, and painted allegories that celebrate royal virtues and religious devotion. Artists and artisans from across France were brought to Strasbourg to execute these works, importing the latest trends from Paris and Versailles.

This infusion of French taste did not erase Strasbourg’s Germanic heritage but rather created a fascinating cultural hybrid. Many local artists adapted to the new styles while infusing them with regional sensibilities. Painters like Joseph Melling, who would later direct the École de dessin de Strasbourg (founded in 1760), skillfully blended French academic traditions with a more intimate, expressive approach typical of German painting.

Religious art, too, underwent a profound transformation. The Protestant churches of Strasbourg, which had emphasized plainness and scriptural centrality, remained largely unadorned. However, Catholic spaces — notably the Strasbourg Cathedral, reclaimed by Catholics after the annexation — were subtly re-Frenchified. Baroque altarpieces, ornate confessionals, and dramatic sculptural ensembles began to appear, reasserting the visual authority of Catholicism in a city long shaped by Protestant restraint.

Sculpture during this period blossomed with a particular vitality. Public fountains, tomb monuments, and church interiors displayed a new emphasis on dynamic poses, flowing drapery, and emotive expression. The Fontaine de Janus, built in the 18th century, though now lost, was one such example of the Baroque impulse to combine utility, allegory, and theatricality in urban spaces.

By the mid-18th century, the Rococo style — a lighter, more whimsical evolution of the Baroque — began to influence Strasbourg’s interiors, especially among the bourgeoisie and clergy. Rococo art delighted in asymmetry, pastel colors, delicate ornamentation, and themes of love, nature, and leisure. Decorative arts thrived: cabinetmakers, silversmiths, and porcelain manufacturers produced exquisite objects that reflected the city’s growing prosperity and taste for refined living.

One fascinating manifestation of Rococo culture in Strasbourg was the rise of private art collections. Wealthy citizens began commissioning portraits, genre scenes, and still lifes — often from itinerant or court-connected artists — to decorate their homes. Art was no longer solely the domain of the Church or the state; it became a personal pleasure, a marker of taste and education.

Music, too, played an important role in the cultural life of Baroque and Rococo Strasbourg. The cathedral’s grand organ, built by Andreas Silbermann in 1716, remains one of the finest instruments of its kind and a testament to the period’s love of grandeur and complexity. Silbermann’s organs, spread across Alsace, embodied the same blend of French and German traditions that characterized the city’s visual arts.

Despite these rich developments, the Baroque and Rococo eras in Strasbourg were always tinged with a certain ambivalence. The French cultural dominance was undeniable, yet beneath it simmered a strong regional identity that clung to older traditions, languages, and forms. In some ways, the art of this period can be seen as a negotiation — a dialogue between the imposed aesthetics of Versailles and the stubborn spirit of Alsace.

As the 18th century waned, this tension would sharpen into outright upheaval. The French Revolution was on the horizon, and with it would come an iconoclastic fury that would sweep away much of the ancien régime’s artistic legacy. Yet even as palaces were stormed and churches desecrated, the deep artistic currents that had shaped Strasbourg for centuries would prove remarkably resilient — adapting, transforming, and reemerging in new forms.

Revolutionary Turmoil and the Impact on Artistic Life

By the late 18th century, the gilded splendor of Strasbourg’s Baroque and Rococo periods faced a rising tide of revolutionary change. The French Revolution, which erupted in 1789, swept through Strasbourg with a force that profoundly altered every aspect of its cultural life — including the arts. Where once art had been a medium of religious devotion and aristocratic display, it now became a battleground for ideological expression, civic identity, and, often, survival.

Strasbourg’s initial embrace of revolutionary ideals was enthusiastic. The city had long harbored a spirit of independence, and its educated bourgeoisie found the calls for liberty, equality, and fraternity deeply appealing. Yet the revolution was not a gentle transition; it was a radical rupture. The ancien régime’s artistic and religious symbols, so carefully cultivated over centuries, were suddenly seen as emblems of oppression and superstition.

One of the first victims of this cultural upheaval was religious art. Strasbourg’s churches — including the mighty Cathedral of Notre-Dame — faced waves of iconoclasm. Statues of saints were smashed, altarpieces dismantled, and reliquaries looted. In 1793, during the height of the Reign of Terror, the cathedral itself was rebranded the “Temple of Reason,” stripped of its religious functions and turned into a revolutionary space. The spire of the cathedral, which had once proclaimed civic pride and Christian piety, became a target for anti-clerical fervor; it was only spared destruction when a local official ingeniously crowned it with a massive Phrygian cap — the symbol of revolutionary liberty.

Artistic production during the revolutionary years shifted dramatically from the sacred and the aristocratic to the secular and the civic. Public monuments celebrating kings and cardinals were torn down, and new monuments honoring revolutionary martyrs and ideals were erected. In Strasbourg, as elsewhere in France, public squares became theaters of political pageantry, with ephemeral architecture — arches of triumph, liberty trees, and altars to Reason — quickly constructed for festivals and ceremonies.

Painters and sculptors adapted, often out of necessity. Religious commissions dried up, and patronage from the nobility vanished. Artists turned to revolutionary themes: allegories of Liberty, Equality, and the Rights of Man; portraits of revolutionary leaders; and scenes depicting heroic sacrifice for the Republic. Art workshops, formerly sustained by ecclesiastical and aristocratic demand, found new life producing patriotic imagery, civic emblems, and even propaganda.

One particularly fascinating development was the rise of “popular art” — woodcuts, prints, and inexpensive paintings aimed at a broader, less elite audience. Revolutionary pamphlets often featured crude but powerful images meant to inflame public sentiment and vilify enemies of the state. Strasbourg’s printers, with their long tradition of woodcut illustration, played a significant role in this new, populist visual culture.

Yet the revolution’s impact on Strasbourg’s art world was not purely destructive. It also laid the groundwork for a new democratization of culture. Museums, previously the private preserves of monarchs and aristocrats, began to open their doors to the public. Strasbourg’s Musée des Beaux-Arts, for example, was founded in 1801 under Napoleon’s rule, part of a broader campaign to make art accessible to all citizens. The museum initially drew much of its collection from secularized churches and confiscated noble estates — a bittersweet legacy of revolutionary expropriation.

Architecture, too, underwent a radical shift. Revolutionary ideals called for a new kind of public space: rational, symmetrical, and free from the ostentation of monarchy. In Strasbourg, while the medieval and Baroque fabric of the city remained largely intact, new urban projects reflected Enlightenment values: open squares, neoclassical facades, and functional civic buildings designed to serve the needs of a free citizenry.

The revolution also fostered a new type of artist: one who was politically engaged, socially conscious, and often precariously employed. The old structures of patronage had collapsed, and artists were now expected to find their place in a competitive, sometimes hostile public marketplace. This shift foreshadowed many aspects of modern artistic life — the tension between creative freedom and political engagement, between individual expression and public expectation.

Despite the violence and upheaval, Strasbourg’s cultural resilience was remarkable. By the turn of the 19th century, as the revolutionary fervor gave way to the more stable authoritarianism of Napoleon’s rule, the city’s artistic institutions began to recover and even flourish. The seeds planted during the revolution — of public education, civic art, and the democratization of culture — would continue to shape Strasbourg’s artistic evolution for generations to come.

Yet the scars remained: shattered sculptures, lost masterpieces, desecrated churches. The memory of this cultural violence lingered in Strasbourg’s collective consciousness, a reminder that art, like politics, can be a site of both profound creation and devastating destruction.

As we move into the 19th century, we will see how Strasbourg’s artists, architects, and intellectuals sought to reclaim and redefine their identity — often looking backward to their medieval and Renaissance heritage even as they grappled with the demands of a new, modern world.

19th Century Romanticism and National Identity in Art

The 19th century was a period of profound transformation for Strasbourg — politically, culturally, and artistically. Following the turbulence of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic era, Strasbourg found itself, once again, at the intersection of national ambitions. As power shifted and borders redrew, the city’s art reflected a deepening engagement with questions of identity, history, and belonging. Romanticism, with its passionate embrace of emotion, nostalgia, and national myth, found fertile ground here, shaping a new artistic and cultural awakening.

After Napoleon’s fall in 1815, Strasbourg was firmly re-integrated into France, but its proximity to Germany and its deep-rooted Germanic cultural heritage made it a unique case. Throughout the 19th century, Strasbourg embodied a cultural duality, both French and German, and this tension became a central theme in its artistic production.

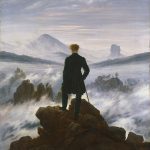

Romanticism, which swept across Europe in the early 19th century, was a natural fit for Strasbourg’s historical and emotional landscape. The Romantic sensibility valued medievalism, gothic ruins, sublime nature, heroic struggle, and deep feeling — all elements that resonated powerfully in a city overshadowed by its grand cathedral and centuries of complex history.

Artists and writers in Strasbourg began to look backward with longing and pride. The cathedral, which had survived the revolutionary era scarred but standing, became a potent symbol not only of religious faith but of cultural endurance. Painters and illustrators captured it obsessively, emphasizing its soaring Gothic lines and weathered stone — a visual language that spoke to the Romantic ideals of grandeur, decay, and continuity.

One key figure of this era was Théophile Schuler (1821–1878), a Strasbourg-born painter and illustrator whose work embodies the Romantic spirit of the city. Deeply influenced by both German Romanticism and French literary movements, Schuler is best known for his haunting painting The Chariot of Death (1848–1851), a monumental canvas now housed in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg. This apocalyptic vision, painted in the wake of the 1848 revolutions that shook Europe, blends medieval allegory, religious symbolism, and raw emotional power, capturing the era’s sense of tumult and hope betrayed.

Schuler was also a prolific illustrator, contributing to numerous editions of classic literary works — including Victor Hugo, Goethe, and Shakespeare — thereby weaving together Strasbourg’s cross-cultural affinities. His art often features medieval knights, Gothic ruins, and spectral landscapes, echoing Strasbourg’s own layered, haunted history.

Architecture, too, reflected the Romantic fascination with the past. A movement known as Gothic Revival took hold in Strasbourg, part of a broader European trend to restore — and sometimes “improve” — medieval monuments. In the mid-19th century, major restoration work began on Strasbourg Cathedral under the direction of architects like Émile Boeswillwald and, later, Gustave Klotz. These restorations aimed to return the cathedral to an imagined medieval purity, sometimes adding elements that were more idealized than historically accurate.

The Gothic Revival was not just about nostalgia; it was also deeply political. In the context of rising nationalism — both French and German — the medieval period was seen as a touchstone for authentic national identity. For French Romantic nationalists, Strasbourg’s Gothic cathedral was a testament to French genius and Christian civilization. For German nationalists, it was evidence of Germany’s deep-rooted cultural greatness. Thus, Strasbourg’s art and monuments became battlegrounds for competing historical narratives.

This tension only deepened after the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), when Strasbourg, after a brutal siege and bombardment, was annexed by the newly unified German Empire. The war and annexation had a devastating impact on the city’s artistic and cultural institutions. Many buildings were damaged or destroyed, including the municipal library, where priceless medieval manuscripts like the original Hortus Deliciarum perished in the flames.

Yet out of this trauma emerged a new phase of Romantic nationalism. German authorities undertook major cultural projects in Strasbourg, aiming to showcase the city as a jewel of the new Reich. They built the Neustadt (New City) district — a vast urban expansion in neo-Renaissance and neo-Gothic styles, designed to express imperial pride and Germanic heritage. Strasbourg thus became a kind of living museum of architectural styles, where medieval, Baroque, and 19th-century historicism jostled side by side.

Artists, too, responded to the annexation with a new intensity. Some, like the Strasbourg-born painter Charles Spindler, turned to Alsatian folk life and traditions as subjects, documenting village customs, costumes, and landscapes with a loving ethnographic eye. Spindler’s work — particularly his marquetry panels and illustrated books — sought to preserve and celebrate a distinct Alsatian identity at a time when that identity was being politically contested.

Literature also flourished in this period. Writers like Émile Erckmann and Alexandre Chatrian (known collectively as Erckmann-Chatrian) wrote novels and stories set in Alsace, blending local color with patriotic sentiment. Their works, widely read across France, helped cement Strasbourg’s image as a land of brave, suffering people caught between empires.

By the end of the 19th century, Strasbourg had been transformed — physically, politically, and artistically. Romanticism, with its emphasis on memory, identity, and emotional truth, had left an indelible mark. Yet as the century closed, new artistic movements — Realism, Impressionism, Symbolism — were beginning to challenge Romantic ideals, setting the stage for further upheaval and innovation in the city’s vibrant artistic life.

The 19th century taught Strasbourg that art was not just a mirror of society but a means of survival — a way to claim and reclaim identity in the face of conquest, loss, and change. That lesson would continue to shape the city’s art well into the modern era.

Strasbourg School of Art and the Rise of Regionalism

As Strasbourg transitioned into the 20th century, the city’s art world experienced a subtle but profound shift. While the grand ideologies of Romantic nationalism had dominated the 19th century, the dawn of a new era brought a quieter, more introspective movement to the fore: regionalism. It was an artistic current rooted not in sweeping political myths, but in the intimate, everyday life of Alsace — its villages, its traditions, its landscapes, and its people. At the heart of this movement was the emergence of what is often called the Strasbourg School of Art.

Regionalism in Strasbourg was a response to the profound cultural anxieties that followed decades of political upheaval. After the Franco-Prussian War and annexation by Germany, Alsatians found themselves grappling with questions of loyalty and identity. Were they French? German? Something else entirely? Regionalist artists answered by turning their gaze inward, emphasizing the distinctiveness of Alsace itself — its unique fusion of cultures, languages, and customs.

The Strasbourg School was less a formal institution than a shared sensibility among a group of artists, writers, and craftsmen who sought to celebrate Alsace’s particular character. They produced paintings, prints, marquetry, illustrated books, and decorative objects that depicted Alsatian folk life with vivid detail and affectionate realism.

One of the leading figures of this movement was Charles Spindler (1865–1938), a painter, marquetry artist, and publisher whose work became emblematic of Strasbourg’s regionalist spirit. Spindler grew up in the Alsatian countryside and was deeply influenced by its rhythms and traditions. His art lovingly chronicled rural scenes: harvest festivals, village fairs, peasant weddings, and daily labor in the fields. His famous marquetry panels — intricate images made from inlaid woods of different colors — transformed simple acts of life into exquisite works of art, bridging fine art and craft in a distinctly Alsatian way.

Spindler also played a crucial role in reviving and promoting local traditions. In 1898, he founded the Revue Alsacienne Illustrée, an influential journal that combined literature, art, and ethnography. Its mission was clear: to document, celebrate, and preserve Alsatian culture at a time when it was threatened by both German imperial assimilation and, later, French centralization. Writers, poets, and illustrators gathered around the Revue, creating a vibrant artistic community determined to assert regional identity through beauty and scholarship.

Another important figure was Léo Schnug (1878–1933), a painter known for his romanticized depictions of medieval life and Alsatian folklore. Trained at the Strasbourg School of Decorative Arts (École des arts décoratifs de Strasbourg), Schnug developed a style rich in historical detail, sumptuous color, and a touch of theatrical fantasy. His murals, book illustrations, and costume designs reflected an intense love for the past, particularly the pageantry of Strasbourg’s medieval and Renaissance eras.

Schnug’s most famous works include his decorations for the Château du Haut-Koenigsbourg, a medieval castle restored (and somewhat reconstructed) by order of Kaiser Wilhelm II in the early 20th century. Schnug’s murals there blend historical imagination with nationalist symbolism, underscoring the complex ways regional art was entangled with larger political narratives — German imperial pride in this case, but with a distinctively Alsatian flavor.

Education also played a critical role in shaping the Strasbourg School. The École des arts décoratifs de Strasbourg, founded in 1892, became a key institution for training artists in both fine and applied arts. Under the leadership of figures like Anton Seder, a German-born artist who brought influences from the Jugendstil (Art Nouveau) movement, the school encouraged a synthesis of regional tradition and modern design principles. Students were taught not only painting and sculpture but also graphic design, furniture making, stained glass, and book illustration — preparing them to contribute to a broad cultural renaissance.

Indeed, regionalism in Strasbourg was not merely about nostalgia; it was also about modernity. Many artists engaged with the broader European movements of their time — Art Nouveau, Symbolism, Jugendstil — but adapted them to local themes and materials. There was a conscious effort to root innovation in tradition, to show that Alsatian culture could be both proudly distinctive and fully modern.

This regionalist ethos extended into architecture and the decorative arts as well. In the Neustadt district, grand civic buildings blended neo-Renaissance forms with subtle local touches. In private homes, artisans created furniture, textiles, and glassware that combined Alsatian motifs with contemporary design. Strasbourg’s streets, interiors, and printed works all bore the mark of a city rediscovering its soul through art.

However, the shadow of geopolitics never fully lifted. After World War I and the return of Alsace to France, regionalist artists faced new challenges. French authorities promoted an official vision of “Frenchness,” and some aspects of local culture were marginalized or reinterpreted through a nationalist lens. Yet even under these pressures, the Strasbourg School endured, evolving, adapting, and quietly preserving a vision of Alsace that was neither wholly German nor wholly French, but fiercely, beautifully its own.

The legacy of this period is profound. Even today, in Strasbourg’s markets, festivals, museums, and galleries, one can feel the lasting impact of those artists who chose to turn their attention not to the centers of power, but to the fields, forests, and villages of their homeland — finding there a source of endless inspiration and quiet defiance.

As the 20th century moved forward, however, new forces would sweep through Strasbourg — avant-garde modernism, war, reconstruction — challenging the regionalist idyll and propelling the city’s art scene into a more turbulent, experimental future.

Modernism and Avant-Garde Movements: Between France and Germany

The dawn of the 20th century brought profound change to Strasbourg’s art scene. The regionalist idyll that had dominated the late 19th century began to give way to new forces: industrialization, urbanization, war, and — crucially — modernism. As old certainties crumbled, Strasbourg’s artists found themselves once again at a cultural crossroads, caught between the radical innovations of Paris and Berlin. What emerged was a vibrant, if often conflicted, artistic ferment that positioned Strasbourg as a key player in the story of European modernism.

The shock of World War I (1914–1918) was pivotal. When the war ended, Alsace-Lorraine was returned to France after nearly 50 years of German rule. This political change was accompanied by a cultural campaign to re-Frenchify Strasbourg, encouraging French language, customs, and institutions. For artists, this meant grappling with new audiences, new expectations, and new opportunities.

The École des arts décoratifs de Strasbourg — long a symbol of Germanic art education — was reorganized under French direction but retained its strong emphasis on applied arts and graphic design. In many ways, Strasbourg was perfectly positioned to absorb and synthesize the twin energies of the Parisian avant-garde and the German Expressionist and Bauhaus movements.

One of the earliest signs of this modernist turn was the Salon des artistes indépendants d’Alsace, founded in 1920. Inspired by the Parisian model, the salon provided a platform for artists outside the academic mainstream to exhibit their work freely. Young painters, sculptors, and designers explored Fauvism’s bold colors, Cubism’s fractured perspectives, and Expressionism’s emotional intensity, often fusing these international styles with regional or personal themes.

A crucial figure in this new era was Jean-Jacques Waltz, better known by his pseudonym Hansi. Though often remembered for his satirical, folk-inspired illustrations celebrating Alsatian culture, Hansi’s art also incorporated modern graphic sensibilities: simplified forms, vivid colors, and a keen sense of composition influenced by Art Nouveau and early modern poster design. His politically charged works — fiercely pro-French and anti-German — reflect the complicated loyalties and artistic tensions of the period.

Meanwhile, other artists pushed even further into modernist experimentation. Jean Arp (Hans Arp), born in Strasbourg in 1886, would become one of the most influential abstract artists of the 20th century. A founding member of the Dada movement in Zurich during World War I, Arp embodied the spirit of radical rebellion against traditional art forms. His biomorphic sculptures, collages, and poetry rejected rationalism and embraced chance, spontaneity, and organic forms.

Though Arp spent much of his career abroad, his Alsatian roots profoundly shaped his sensibility — a love of fluidity, ambiguity, and hybrid identities. His connection to Strasbourg is a reminder that the city’s modernism was not simply an imported fashion but grew out of its unique historical and cultural tensions.

Strasbourg’s engagement with modernist architecture also deserves special mention. During the 1920s and 1930s, the city saw the construction of new housing projects, schools, and public buildings that reflected the clean lines and functional ethos of modern design. Influences from the Bauhaus and Le Corbusier’s rationalist ideals found expression in the city’s urban renewal projects, albeit often tempered by local materials and stylistic traditions.

However, Strasbourg’s modernist flowering was brutally interrupted by the outbreak of World War II. Once again, Alsace was annexed by Germany, and Strasbourg was subjected to intense cultural Germanization. Many artists fled, went underground, or adapted their work in subtle ways to survive the repressive atmosphere.

In the postwar years, Strasbourg reemerged battered but resilient, its art scene deeply marked by the experiences of war and occupation. Jean Arp, by then internationally renowned, returned periodically to Alsace and became a symbol of the region’s enduring creativity. His collaborations with his wife, the artist Sophie Taeuber-Arp, and their commitment to pure abstraction, influenced a generation of younger Alsatian artists.

The immediate postwar period also saw a resurgence of figurative art, often infused with existential themes — reflections on trauma, survival, and the search for meaning in a shattered world. Strasbourg’s artists engaged in dialogues with broader European movements like Art Informel, CoBrA, and later, New Realism, but always with a local inflection, balancing international trends with a deep awareness of place and history.

Public institutions played a key role in nurturing this complex modernist legacy. The Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain de Strasbourg, inaugurated much later in 1998, brought together decades of modern and contemporary art, cementing Strasbourg’s position not just as a historical city but as a dynamic center for living, evolving art.

Through all its upheavals, the art of modernist Strasbourg remained true to a central theme: hybridity. It is a city where abstraction and memory, rebellion and tradition, French and German influences collide and merge, creating forms that are never purely one thing or another — just as Strasbourg itself has never been defined by a single identity.

As we move forward into the contemporary period, we’ll see how this spirit of openness, complexity, and resilience continues to shape Strasbourg’s vibrant art scene today.

Contemporary Art Scene: From Public Art to European Institutions

Today, Strasbourg stands as a city where the layers of history do not weigh it down but rather lift it into continual reinvention. Its contemporary art scene is a vibrant testament to that energy — an ever-evolving dialogue between tradition and innovation, local identity and European ambition. From bold public art installations to cutting-edge contemporary exhibitions, Strasbourg has become not just a preserver of heritage but a vital producer of new cultural life.

One of the most visible signs of Strasbourg’s modern artistic vitality is its embrace of public art. Across the city, art spills out of museums and galleries into streets, parks, and civic spaces, making creativity part of daily life. In the historic center, near the Place Kléber, sculptures, murals, and installations bridge the Gothic and Renaissance façades with contemporary expressions.

A standout example is the Aire de Jeux, a large-scale public artwork by Jean-Luc Vilmouth, designed as a playful reimagining of urban space. Similarly, the “Two Shores Garden” (Jardin des Deux Rives) along the Rhine, linking Strasbourg with Kehl in Germany, features numerous art installations that emphasize the themes of dialogue, reconciliation, and European unity — powerful messages in a city that has experienced both division and cooperation.

Another striking feature of Strasbourg’s public art is its openness to experimentation. Temporary exhibitions, performances, and urban art festivals animate the city year-round. The L’Industrie Magnifique festival, launched in 2018, brings together artists, industries, and the public in an open-air celebration of sculpture, design, and creative partnerships — blurring the traditional boundaries between fine art and applied art, creator and audience.

At the heart of Strasbourg’s contemporary art life is the Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain de Strasbourg (MAMCS). Opened in 1998 on the banks of the Ill River, the museum itself is a bold architectural statement, designed by Adrien Fainsilber. Its luminous spaces house an impressive collection spanning the late 19th century to today, including works by Gustave Doré (a native of Strasbourg), Jean Arp, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, and contemporary artists from Europe and beyond.

The MAMCS is not just a repository of art but a living center of research, creation, and exchange. Temporary exhibitions regularly showcase emerging trends, from digital installations to socially engaged art practices. The museum also maintains a deep commitment to the city’s own avant-garde legacy, frequently revisiting the Dada movement, abstraction, and the intersections of art and political identity.

Strasbourg’s contemporary art scene is also deeply tied to its role as a European capital. Hosting institutions like the European Parliament, the Council of Europe, and the European Court of Human Rights, Strasbourg embodies ideals of cross-cultural dialogue, democracy, and human rights. Artists often engage with these themes, using their work to comment on migration, memory, citizenship, and the complexities of European identity.

One notable example is the Parlement de Strasbourg art program, which invites contemporary artists to create works specifically for the European institutions. Artworks such as monumental tapestries, installations, and site-specific sculptures underscore the city’s unique status as a meeting ground for ideas and cultures.

Artist residencies, workshops, and collaborations flourish here, supported by organizations like the CEAAC (Centre Européen d’Actions Artistiques Contemporaines). Founded in 1987, the CEAAC promotes the exchange of artists across Europe, organizing exhibitions, public art projects, and residencies that foster creative dialogue beyond national borders.

Strasbourg also nurtures a dynamic independent scene. Alternative spaces such as La Semencerie, a collective run by and for artists, provide platforms for experimental and non-commercial work. Here, young creators challenge conventions, explore new media, and engage directly with local and global issues, keeping the city’s artistic pulse fresh and vital.

Annual events like the Strasbourg Contemporary Art Biennale (founded in 2018) further elevate the city’s reputation as a hub for new artistic thinking. The Biennale brings together international artists working across mediums — video, installation, painting, performance — often centered on urgent themes like climate change, political upheaval, and the reimagining of public space.

Yet even amidst these innovations, Strasbourg never entirely abandons its history. Contemporary artists often engage directly with the city’s past: reinterpreting its medieval myths, addressing the scars of war and displacement, or reimagining its architectural heritage through new lenses. This continuous dialogue between memory and invention gives Strasbourg’s contemporary art a distinctive depth and resonance.

Today, Strasbourg is not merely a place where art is displayed; it is a place where art is lived. Whether in the bustling halls of MAMCS, the quiet interventions in public squares, the charged debates inside the European Parliament, or the experimental studios tucked into old industrial neighborhoods, art here is a way of thinking, questioning, belonging — and sometimes resisting.

In the story of Strasbourg, art has always been more than decoration: it is an act of identity, a means of survival, a tool of hope. And in the contemporary moment, more than ever, it is a declaration that the crossroads of Europe is not a place of borders, but a place of endless beginnings.

Cultural Institutions and Museums: Guardians of Strasbourg’s Artistic Legacy

In a city where history seems to rise from every stone and every street corner, cultural institutions play a crucial role not just as caretakers of the past, but as living conduits between yesterday and today. Strasbourg’s museums and cultural centers stand as guardians of a multifaceted artistic legacy — one shaped by Roman roots, Gothic grandeur, Renaissance innovation, revolutionary upheaval, Romantic passion, and modernist daring.

The Musée des Beaux-Arts is perhaps the most iconic among them. Located within the resplendent Palais Rohan, a Baroque masterpiece built for the prince-bishops of Strasbourg, the museum houses a rich collection that spans from the early Renaissance to the mid-19th century. Its holdings are remarkably diverse, featuring Italian masters like Botticelli and Raphael, Flemish luminaries such as Rubens and Van Dyck, and French painters like Chardin and Delacroix.

Yet what truly distinguishes the Musée des Beaux-Arts is not only the quality of its collection but the story it tells about Strasbourg’s place at the crossroads of Europe. The works within reflect a city that has always absorbed and reflected broader artistic currents while maintaining its own distinct flavor. A visitor wandering through the galleries moves seamlessly between Italian grace, Dutch realism, and French romanticism — a journey mirroring Strasbourg’s own layered identity.

Closely tied to this is the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame, one of Europe’s finest museums dedicated to medieval and Renaissance art from the Upper Rhine region. Housed in a series of charming historic buildings near the cathedral, the museum preserves stone sculptures, stained glass, altarpieces, and decorative arts — many salvaged from the cathedral itself or nearby churches. Walking through its atmospheric halls, one can trace the evolution of Strasbourg’s Gothic brilliance and understand how deeply the city’s medieval artisans influenced the broader Germanic world.

The museum also serves as a reminder that Strasbourg’s art history is not just a parade of great names but a story of anonymous craftsmen — stone carvers, glaziers, goldsmiths — whose collective genius shaped one of Europe’s great cultural centers.

No exploration of Strasbourg’s cultural institutions would be complete without returning to the Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain de Strasbourg (MAMCS), a beacon of living creativity. As discussed earlier, MAMCS not only curates an impressive collection of modern art — including important works by Gustave Doré, Jean Arp, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp — but also acts as an incubator for contemporary talent. Temporary exhibitions, artist residencies, and public programs ensure that the museum remains a dynamic, ever-changing space, connecting Strasbourg’s avant-garde legacy to its future.

Beyond these flagship museums, Strasbourg boasts an array of specialized institutions that enrich its cultural tapestry:

- The Musée Historique de Strasbourg chronicles the city’s political, economic, and social history from the Middle Ages to the present day, offering fascinating insights into how art and daily life intertwine.

- The Musée Alsacien, housed in a cluster of 16th- and 17th-century houses, presents a lovingly detailed portrait of rural Alsatian life, showcasing folk art, costumes, religious objects, and domestic interiors. This museum embodies the regionalist spirit that has so often shaped Strasbourg’s cultural imagination.

- The Tomí Ungerer Museum honors one of Strasbourg’s most famous modern illustrators. Ungerer’s biting, often provocative drawings — spanning children’s literature, satire, and erotica — reflect a spirit of creative freedom and political engagement that remains central to Strasbourg’s artistic life.

Strasbourg’s commitment to cultural preservation extends beyond traditional museums. Institutions like the Bibliothèque nationale et universitaire de Strasbourg safeguard manuscripts, rare books, and archives, including materials rescued after the devastating fires of the Franco-Prussian War. Meanwhile, contemporary venues like La Laiterie and Le Maillon offer spaces for experimental music, theater, and performance art, ensuring that the city’s cultural life remains as dynamic and unpredictable as its history.

Another powerful symbol of Strasbourg’s cultural vision is the integration of art into public and civic life. The restoration of historical sites, the commissioning of new public artworks, and the support for multidisciplinary festivals — such as the Festival Musica (contemporary music) and Ososphère (digital arts) — show a city that refuses to let its past fossilize. Instead, Strasbourg treats its cultural heritage as a living organism, constantly renewing itself.

The presence of the European institutions in Strasbourg has also influenced its cultural policies, fostering an ethos of openness, diversity, and dialogue. Cross-border collaborations with neighboring German cities like Kehl and Karlsruhe, artist exchanges, and EU-funded cultural programs have transformed Strasbourg into a true European cultural capital — a meeting place not only for nations but for ideas, visions, and artistic practices.

In many ways, Strasbourg’s museums and cultural institutions do more than house artworks: they tell the city’s story. A story of survival and reinvention, of negotiation between competing traditions, of creativity born from conflict and fusion. They remind visitors — and residents — that art is not a luxury or an ornament, but a fundamental part of what it means to be human, especially in a place where history is never just in the past but woven into the very air.

As we look next at the key figures who helped shape Strasbourg’s artistic legacy — the artists, architects, and patrons who made it all possible — we see that the institutions standing today are not mere monuments, but living testaments to their vision, struggle, and triumph.

Key Figures: Artists, Architects, and Patrons of Strasbourg

The art history of Strasbourg is not merely a sequence of movements and styles; it is, above all, a human story. Across centuries, individuals — visionary artists, brilliant architects, generous patrons — have shaped the cultural soul of the city. Their contributions, whether monumental or subtle, have made Strasbourg one of Europe’s richest artistic centers. To understand the city’s creative pulse, we must meet the people who fueled it.

Erwin von Steinbach (c. 1244–1318) stands at the very beginning of Strasbourg’s golden age. As one of the principal architects of Strasbourg Cathedral, Erwin von Steinbach became a near-mythic figure. Although much of what is known about him is shrouded in legend, his name is closely linked to the cathedral’s awe-inspiring west façade. His work epitomizes Gothic innovation: a complex interplay of soaring verticality, intricate sculpture, and symbolic narrative. Erwin’s vision helped define not only Strasbourg’s skyline but its identity as a beacon of medieval creativity.

Following the trail into the Renaissance, Strasbourg became a center for early printing — and with it, a new kind of artistic figure emerged. Johannes Gutenberg, though more closely associated with Mainz, spent formative years in Strasbourg. Here, he experimented with movable type, fundamentally altering the dissemination of art and knowledge. His indirect influence on Strasbourg’s visual culture was enormous: the city’s manuscript illuminators transitioned into book illustrators, fostering an explosion of printed images.

Among those who embraced the marriage of art and print was Sebastian Brant (1457–1521), humanist, poet, and author of Das Narrenschiff (The Ship of Fools). His sharp wit and moralistic satire captured the spirit of early Strasbourg Humanism. Collaborating with artists (possibly even a young Albrecht Dürer), Brant’s work made Strasbourg a European center for illustrated books — a legacy still alive today.

The Baroque and Rococo periods saw the arrival of powerful patrons, especially from the Church. The Rohan family, particularly Cardinal Armand Gaston de Rohan, commissioned major projects like the Palais Rohan. While artists of the court, architects like Robert de Cotte — principal architect to Louis XIV — brought the refined elegance of French classicism to Strasbourg, giving the city some of its most lasting architectural jewels.

In the revolutionary era, political upheaval largely displaced individual artistic figures in favor of collective civic actions — but the 19th century brought a renewed focus on individual artistic identities. Among the most significant was Théophile Schuler (1821–1878), whose intense Romantic paintings, especially The Chariot of Death, captured the turmoil and idealism of the period. Schuler’s influence extended beyond painting: he served as a mentor to younger artists and helped lay foundations for Strasbourg’s continued artistic dynamism.

Charles Spindler (1865–1938) was perhaps the most emblematic figure of Alsatian regionalism. Painter, marquetry master, publisher, and cultural activist, Spindler’s loving depictions of Alsatian rural life helped preserve local identity through some of the most politically volatile decades. His Revue Alsacienne Illustrée not only celebrated Alsatian folk culture but also engaged in an early form of cultural preservation against the forces of assimilation.

The early 20th century saw Strasbourg contribute directly to the avant-garde through the visionary work of Jean Arp (1886–1966). As a founder of the Dada movement and later a pioneer of abstract sculpture, Arp’s biomorphic forms and collaborations with figures like Sophie Taeuber-Arp placed Strasbourg firmly within the map of European modernism. His art, both playful and profound, echoes Strasbourg’s own complex identity — fluid, hybrid, in constant negotiation with history.

In the world of architecture, Auguste Dollfus and others contributed significantly to the city’s post-Franco-Prussian War reconstruction and the shaping of the Neustadt district. Their works combined French urban planning ideals with German historicism, resulting in a striking, eclectic urban landscape that remains one of Strasbourg’s defining features.

Contemporary Strasbourg continues to be shaped by key cultural figures. Curators at institutions like the Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain de Strasbourg (MAMCS) — including figures like Estelle Pietrzyk — have positioned Strasbourg at the forefront of European contemporary art through innovative programming and international collaborations.

Patrons today are not only wealthy individuals or aristocrats, as in the past, but civic institutions, NGOs, and the European bodies based in the city. Initiatives like the CEAAC and the Fondation de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame — which has cared for the cathedral’s fabric and associated artworks since the Middle Ages — show how collective stewardship continues to support Strasbourg’s artistic life.

Through all periods, one sees a pattern: Strasbourg’s art has been driven by a special blend of individual genius and communal vision. Whether in the form of a single soaring spire, a hand-illuminated manuscript, a radical abstract sculpture, or a city-wide contemporary art festival, Strasbourg’s creativity has always relied on people willing to look beyond the immediate moment — people who recognized that art, at its best, both preserves memory and shapes the future.

As we turn toward our final sections — the influence of Strasbourg’s multicultural identity and a broader conclusion — it becomes even clearer that this city’s artistic journey is not simply one of evolution, but of constant rebirth.

The Influence of Strasbourg’s Multicultural Identity on Its Art

Strasbourg is a city of bridges — not only the physical spans that cross the Rhine, but the cultural, linguistic, and historical bridges that have defined its very essence. Located at the junction of Latin and Germanic Europe, contested by empires and claimed by nations, Strasbourg has long refused the comfort of a single identity. Instead, its art has flourished in the tension, beauty, and complexity of multiplicity. From medieval times to the contemporary era, Strasbourg’s multicultural identity has not only influenced its art — it has been its generative force.

Throughout history, Strasbourg has absorbed and blended the styles, ideas, and techniques of neighboring cultures. In the Middle Ages, it drew equally from the Gothic traditions of France and the monumental sacred art of the Germanic world. The very architecture of Strasbourg Cathedral reflects this: its asymmetrical towers and narrative-rich façades nod to French models like Reims and Chartres, while its sculptural detail and interior program are steeped in Germanic symbolism and spatial logic. It is a church, and a city, both west and east — never one without the other.

The city’s geographic location also made it a major trade and pilgrimage route, exposing it to artistic and material cultures from the Low Countries, Switzerland, Italy, and the Rhineland. This exposure enriched its visual vocabulary: from Flemish oil painting techniques to Italianate decorative motifs, from German printmaking to French courtly fashion, Strasbourg internalized it all and made it its own.

Language has been another powerful vehicle of hybridity. Strasbourg has long been bilingual, with Alsatian dialects shaped by German grammar and French vocabulary. This linguistic duality shaped the literary and visual arts alike. Humanist writers of the Renaissance, such as Jakob Wimpfeling and Johann Geiler von Kaysersberg, wrote in Latin, German, and French — often blending theological critique with popular allegory. Their texts, frequently illustrated by woodcuts, offered visual artists a wide range of symbols and subjects, reflecting the shifting religious and political climate of their multilingual world.

The Reformation brought new urgency to this blending of word and image. Strasbourg’s embrace of Protestantism in the early 16th century was deeply influenced by German theological thought, yet its reformers, like Martin Bucer, emphasized moderation and civic cooperation — more aligned with French humanism. Artists adapted accordingly. Religious paintings gave way to printed broadsheets, satirical woodcuts, and allegorical engravings that could reach a broader, literate public in multiple languages. Art became a tool of persuasion, and its success depended on speaking in many tongues — visually and textually.

Even in the age of nationalism, Strasbourg’s art continued to resist singular identity. The Romantic painters and writers of the 19th century often grappled openly with Alsace’s cultural duality. Charles Spindler and his peers depicted Alsatian peasants in clothing that was Germanic in origin but filtered through a French ethnographic lens. Their work, while deeply local, was a conscious act of cultural diplomacy — an effort to assert the value of a hybrid identity in an age obsessed with purity.

Perhaps no figure embodies this fluid identity more than Jean Arp, born Hans Arp, who navigated the cultural spaces between French Dada and German abstraction, between poetry and sculpture, between nationalism and cosmopolitanism. His decision to use different names in different contexts — Jean in French-speaking settings, Hans in German ones — is a telling expression of Strasbourg’s artistic ambiguity. His art, too, refused borders: abstract yet organic, playful yet profound, rooted in a specific place but always pointing toward something universal.

The multicultural richness of Strasbourg also extends beyond the Franco-German axis. In the postwar decades, and especially since the founding of the European Union’s institutions in the city, Strasbourg has become a hub of pan-European and international culture. Artists from across the continent now exhibit, collaborate, and teach here. Migrant and diasporic voices — from North Africa, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Sub-Saharan Africa — have also begun to shape the city’s creative fabric.

Contemporary art festivals and institutions have embraced this evolution. The CEAAC regularly hosts artists-in-residence from across Europe and beyond, encouraging work that reflects transnational concerns: borders, identity, displacement, and coexistence. Public art projects, especially in Strasbourg’s eastern neighborhoods, engage with the city’s growing diversity, offering platforms for marginalized voices and new forms of expression.

At the same time, Strasbourg’s multiculturalism has also raised critical questions. What does it mean to represent a region so often stereotyped as folkloric or caught between identities? How can art navigate the legacies of conquest, assimilation, and exclusion — while still celebrating hybridity? Many of Strasbourg’s most interesting contemporary artists take these questions head-on, producing work that interrogates as much as it affirms.

This dual nature — celebratory and critical, historical and experimental — defines Strasbourg’s relationship with multiculturalism. It is not a simple harmony, but a dynamic, often tense dialogue. Yet it is precisely this dialogue that gives the city’s art its power: an art that does not erase difference but dwells within it, searching for meaning at the intersection of traditions, tongues, and truths.

As we move into our concluding section, we’ll look back across this long and layered journey — from Roman mosaics to digital installations — and ask what Strasbourg’s art history tells us not only about one city, but about the role of art in places shaped by complexity, conflict, and connection.