Nestled on the banks of the Isar River, Munich might first evoke visions of Oktoberfest, beer gardens, and Baroque palaces — but beneath its postcard surface lies a city whose soul has been shaped as much by paint and plaster as by hops and hedonism. For centuries, Munich has served as one of Europe’s great crucibles of art, an ever-evolving atelier where the sacred, the sublime, and the subversive have all found fertile ground.

It was never a coincidence. Munich’s development as a cultural capital was as strategic as it was organic. By the time Bavaria emerged as a political force in the Holy Roman Empire, Munich — whose name literally means “home of the monks” — had already begun to gather the visual wealth of religious institutions. But its leap into the artistic spotlight was catalyzed by something more enduring than ecclesiastical ambition: the sustained patronage of powerful dynasties, particularly the Wittelsbachs, who turned the city into a cultural greenhouse for styles imported from Italy, France, and later Vienna and Berlin.

The seeds planted by these rulers grew into a formidable ecosystem. Munich’s Old Masters collections would eventually rival those of Florence and Paris. Its academies became magnets for talent across Central and Eastern Europe. Its salons and beer halls served as battlegrounds for aesthetic debate — from the fine line between Romanticism and sentimentality to the explosive break with realism that birthed Expressionism.

Even in times of turmoil — and there were many — the city remained an artistic lightning rod. The 20th century alone saw Munich alternate between being the cradle of avant-garde movements and a stage for fascist cultural propaganda. In 1937, it was here that the Nazis launched the infamous “Degenerate Art” exhibition, mocking the very modernist innovations that had once made the city a beacon of creativity. And yet, in the post-war years, Munich once again asserted itself as a space for artistic rehabilitation and reinvention, becoming home to new waves of conceptual and contemporary art.

To walk through Munich today is to experience an architectural palimpsest — medieval alleys open onto neoclassical plazas; Jugendstil façades curve sensuously beside Brutalist concrete; public art installations interrupt baroque vistas with provocative wit. The city’s three Pinakothek museums alone encapsulate 800 years of European art history. And beyond these institutional walls, a living, breathing art scene continues to thrive — in studio collectives in Haidhausen, in experimental exhibitions in the Kunstareal, and in graffiti along the Isar embankments.

But Munich’s role as a cultural capital cannot be understood in isolation. It must be seen in relation to the artistic currents flowing through Europe — in dialogue with Paris, in tension with Berlin, and often ahead of its time. The story of Munich’s art is not merely one of style, but of struggle: between tradition and rebellion, between state control and artistic freedom, between the desire to preserve and the impulse to destroy.

In this deep dive, we’ll trace the city’s visual history from its medieval foundations to the cutting edges of contemporary practice. Along the way, we’ll meet eccentric dukes, utopian painters, radical secessionists, and underground provocateurs. Through them, Munich’s art history unfolds — not just as a mirror to the city’s soul, but as a powerful lens on the cultural and political transformations of Europe itself.

Medieval Foundations and Gothic Flourishes

Long before Munich became a city of galleries and manifestos, it was a city of guilds and monasteries. In the Middle Ages, art in Munich was inseparable from the rhythms of religious life. It was sacred, symbolic, and steeped in ritual. While not yet a cultural powerhouse, Munich during the Gothic period laid the groundwork for the city’s artistic ascendancy, both literally and figuratively — in towering churches and the slow accumulation of skilled craftsmanship that would one day serve courts and kings.

Founded officially in 1158, Munich was born at a time when Europe was caught in the powerful grip of the Gothic imagination. This was an age of soaring cathedrals, pointed arches, and intricate stained glass. Art was a divine language meant to instruct and inspire a largely illiterate population. From the very beginning, Munich was part of this spiritual and aesthetic current, even if its early visual culture was more provincial than imperial.

One of the earliest and most enduring Gothic landmarks in Munich is the Church of Our Lady, better known as the Frauenkirche. Construction began in the late 15th century, a relatively late phase of the Gothic period, and the church was completed in just 20 years — a feat of ambition and precision. With its twin onion-domed towers rising over the city, the Frauenkirche became not only a religious symbol but also an emblem of Munich’s identity. While its interior was later altered in subsequent centuries, its Gothic skeleton remains a vital artifact of the era.

But beyond monumental architecture, much of medieval Munich’s art lived in wood and stone. The flourishing of local craft guilds — from stonemasons to goldsmiths — gave rise to an ecosystem of artists who often worked anonymously, creating elaborate altarpieces, carved pulpits, reliquaries, and tomb monuments. The visual language was dense with iconography: saints gazed skyward in wooden agony, angels folded into the curves of pointed niches, and Madonnas exuded serene dignity, often enthroned in carved retables glowing with gold leaf.

One remarkable artifact of this period is the high altar of the Church of St. Peter, a gothic masterpiece that once served as the focal point of Munich’s oldest parish church. Though many works have been lost or altered over the centuries — victims of fires, wars, or Baroque makeovers — what remains reveals a deep commitment to visual storytelling and theological detail.

It’s important to understand that Munich in the Middle Ages was not an artistic leader in the way cities like Nuremberg or Cologne were — both of which had deeper roots in trade and intellectual exchange. But what Munich did possess was stability, bolstered by its strategic location and growing political significance in Bavaria. This stability allowed for the gradual accumulation of wealth and ecclesiastical influence — the two engines that powered much of medieval art. By the 14th century, the city had already attracted the interest of the Wittelsbach dynasty, who would later become its great cultural patrons.

Interestingly, Munich’s position as a cultural “late bloomer” in this period meant that its Gothic art often bore traces of earlier innovations from other regions. One sees the influence of Bohemian elegance in drapery, Franco-Flemish realism in facial expressions, and Italian spatial concerns in panel painting. Munich became a kind of visual crossroads — not yet innovating, but absorbing and refining with increasing skill.

Another often overlooked aspect of Gothic Munich was its manuscript illumination. Monasteries like the Benediktbeuern Abbey (just outside the city) were centers of illuminated scripture, chant books, and devotional miniatures. Though fewer of these fragile artifacts have survived, they reveal the intricate detail and meditative focus that characterized the city’s early visual culture. The colors were rich but subtle — burnt umber, lapis lazuli, crimson made from crushed insects — applied with reverent precision. These books were not only read but venerated, embodying the spiritual gravity of an age where art and devotion were one and the same.

As the Gothic period waned in the 16th century, Munich stood on the cusp of a transformation. The Renaissance would bring new ideas of perspective, humanism, and individual artistic identity — but it would not erase what came before. Even in later centuries, the gothic foundations remained, both physically embedded in the city’s skyline and culturally imprinted in its visual memory.

Today, walking through Munich’s old town reveals ghosts of this medieval era: a pointed arch here, a carved tympanum there, the echo of Gregorian chant in a cool stone nave. These fragments remind us that before the manifestos and modernists, before the salons and secessions, Munich was a city where art was a window to the divine — meticulous, mystical, and meant to endure.

Renaissance and Early Modern Patronage

As the late Middle Ages gave way to the dawn of the Renaissance, a profound shift swept across Europe — one that redefined not only how art looked, but why it was made. In Munich, this transformation arrived gradually, pulled along by the long, steady hand of the Wittelsbach dynasty, who by the 16th century had begun to consolidate their cultural ambitions. No longer just patrons of piety, Bavaria’s rulers increasingly saw art as a tool of statecraft — a mirror of their taste, learning, and legitimacy. In this period, Munich became more than a city of sacred stone. It became a laboratory of princely identity.

The story really begins with Duke Wilhelm IV (reigned 1508–1550), a cultivated and ambitious patron who brought Italian and Netherlandish influences to the court. Wilhelm’s rule marked the transition from medieval guild-driven production to centralized, court-sponsored creation. He saw in art the power to project a more refined, worldly Bavaria — one tied to Renaissance ideals of proportion, harmony, and humanism, yet firmly Catholic in its allegiance during the turbulent years of the Reformation.

One of the pivotal moments of Wilhelm’s reign was the commissioning of the Old Court Chapel (Alte Hofkapelle), where early Renaissance frescoes still survive — tentative but vivid attempts at a new pictorial language. More significantly, Wilhelm and his successors began to collect art systematically. They acquired tapestries from Brussels, altarpieces from Swabia, and portraits from Venice. Their palaces became showcases for cosmopolitan refinement, signaling to rival courts that Munich was no provincial backwater, but a rising cultural center.

Enter Albrecht V (reigned 1550–1579), perhaps the most important art patron in Munich’s Renaissance history. A true lover of the arts, Albrecht married into the Habsburg family and maintained close ties with Italian courts, absorbing the lessons of Florence, Rome, and Mantua. He founded what would later become the Bavarian State Collection of Antiquities, and in 1563 he established the Kunstkammer — a “cabinet of curiosities” that fused scientific wonder, exotic artifacts, and fine art into a single princely display. This wasn’t just a personal passion project; it was a conscious effort to place Munich on the European cultural map.

Albrecht’s patronage extended beyond objects to people. He hired Italian sculptors, Flemish painters, and German humanists, creating a polyglot court of creativity. One of the most notable commissions of his reign was the work of Hans Mielich, a Munich-born artist whose paintings and manuscript illuminations, including the elaborately illustrated Liber ad honorem Augustissimi Principis Alberti, blended late Gothic intricacy with Italianate form. Mielich’s delicate portraits of court figures capture not only their likeness but the dawning self-awareness of Renaissance individualism.

This flourishing of art under the Wittelsbachs coincided with — and was complicated by — the rise of the Protestant Reformation. While many regions of Germany fell into iconoclastic fervor, destroying religious images, Munich remained a staunch Catholic stronghold. This conservatism had artistic consequences: religious commissions continued unabated, but with a heightened theatricality, paving the way for Baroque grandeur. Art in Munich thus retained a didactic, devotional function while adopting the visual vocabulary of the Renaissance.

Architecturally, the Renaissance left a more subtle imprint on the cityscape than in Italy. Munich’s churches and palaces often blended Gothic frames with new classical elements: rounded arches, symmetrical façades, and sculptural ornamentation rooted in antiquity. One key structure was the Residenz, the evolving palace complex of the Wittelsbachs, which would become a visual palimpsest of styles — from its Renaissance Grotto Court to later Baroque and Neoclassical additions. Albrecht V’s Antiquarium, completed in 1571, remains one of the most impressive Renaissance interiors in Germany: a long vaulted hall lined with busts, grotesques, and Roman mosaics that declared, unequivocally, Munich’s embrace of humanist culture.

By the early 17th century, Munich had become a cultural capital in its own right. The city’s blend of late Renaissance elegance and Catholic intensity gave it a unique artistic identity, one that foreshadowed the exuberant theatricality of the Baroque era to come. But more importantly, the foundations were set: a centralized, dynastic model of patronage that would define Munich’s cultural life for centuries.

This early modern period also marked the emergence of the artist as courtier, rather than artisan. Painters and sculptors began to be seen as intellectuals — not merely makers, but thinkers and advisors. This evolution in status allowed for more personal expression and experimentation, even within the constraints of courtly decorum. The seeds of modern art, small and tentative, were already being planted.

Baroque Splendor and Rococo Fantasy

By the early 17th century, the cultural gears of Munich had fully shifted. Gone were the solemn harmonies of the Renaissance — in their place came drama, grandeur, and emotional excess. This was the age of the Baroque, and Munich embraced it with the fervor of a city both devoutly Catholic and politically ambitious. Art became spectacle. Architecture became theater. And nowhere was this synthesis more vividly realized than in the churches, palaces, and civic spaces that began to reshape the Munich skyline.

The Baroque period in Munich coincided with the consolidation of absolutist rule in Bavaria. The Wittelsbachs, having survived the upheavals of the Thirty Years’ War, emerged determined to project their power more ostentatiously than ever. Under Elector Maximilian I, Munich became the heart of the Counter-Reformation in southern Germany, a movement that saw the Catholic Church use art not just as a devotional tool, but as an instrument of persuasion — and even seduction. Baroque art’s emotional intensity, movement, and illusionistic space were ideally suited for this purpose.

One of the era’s defining characteristics in Munich was architectural opulence. Churches were transformed into visual feasts, their interiors designed to overwhelm the senses and draw the faithful into divine ecstasy. Among the most spectacular examples is the Asamkirche, formally known as St. Johann Nepomuk, a small private chapel built in the 1730s by the Asam brothers, Cosmas Damian Asam and Egid Quirin Asam. Though only a few meters wide, the church packs an operatic punch: gilded stucco cascades from the ceiling, light filters through hidden windows in theatrical shafts, and painted illusions blur into sculptural reality. Every surface is alive — curling, glowing, ascending toward the heavens.

The Asam brothers were emblematic of a new kind of artist emerging in Munich at the time: both deeply spiritual and technically audacious. Trained in Italy, they brought a Roman exuberance to Bavarian piety, creating altarpieces, ceiling frescoes, and sculptural ensembles that fused architecture, painting, and illusion into seamless wholes. Cosmas Damian’s frescoes, in particular, exhibit a mastery of perspective that rivals anything in Venice or Vienna. He was a virtuoso of di sotto in sù — the illusionistic ceiling view — painting heavenly visions that seemed to open the roof itself.

Another towering figure of this era was Balthasar Neumann, an architect who would become a legend in Southern Germany’s Rococo movement. Though his most famous works lie outside Munich (such as the Würzburg Residence), his influence radiated throughout Bavaria. In Munich, his fluid, curved spatial designs and delicate ornamentation were echoed in the city’s evolving architectural vocabulary, particularly in palatial interiors and chapel architecture.

Under Elector Maximilian II Emanuel (r. 1679–1726) and later his son Elector Karl Albrecht, Munich entered what might be called its Versailles moment. Both rulers were keen to emulate the grandeur of the French court. They expanded the Munich Residenz, turning it into a labyrinth of ceremonial halls, stuccoed chambers, and baroque theatrics. At the same time, they commissioned grand suburban retreats, most notably the Nymphenburg Palace, a sprawling estate that became a symbol of Wittelsbach splendor. There, the Amalienburg pavilion — designed by François de Cuvilliés — stands as one of the most exquisite examples of Rococo architecture in Europe: a pastel dream of mirrors, stucco, and silver that seems more confection than construction.

The Rococo style, which emerged out of the later Baroque, took ornamentation to ethereal extremes. Where Baroque was grand and dramatic, Rococo was intimate and whimsical. In Munich, it found its highest expression not just in palaces but in parish churches and even secular townhouses. The shift from religious awe to aristocratic delight is palpable: angels become cherubs, divine light becomes golden glow, and heaven is imagined more like a courtly masquerade than a battlefield of saints.

Yet even at its most decadent, Munich’s Baroque and Rococo art retained a sense of spiritual gravity. This was, after all, a deeply Catholic city. Every flourish, however playful, had a sacred subtext. This duality — of splendor and sincerity — is part of what makes Munich’s Baroque legacy so enduring.

Music and visual art were also deeply intertwined during this period. Baroque composers like Johann Kaspar Kerll and later Carl Orff (though working later) inherited a visual tradition that influenced performance spaces and scenography. Art was no longer confined to canvases or altars — it became immersive, multisensory, a total environment. The Jesuits, ever influential in Munich, used such multimedia tactics to great effect in their churches and schools, training generations of citizens not only in theology but in aesthetic literacy.

By the mid-18th century, however, the Rococo’s delicacy began to feel outdated in the face of rising Enlightenment ideals. The pendulum would soon swing back toward sobriety, symmetry, and antiquity — and Munich would follow suit, trading its cherubs and gilded scrolls for marble columns and stoic busts.

But the Baroque and Rococo eras left indelible marks on the city — not only in its architecture and churches, but in its cultural DNA. To this day, Munich’s art scene carries traces of this theatrical lineage: a flair for spectacle, a love of detail, and a deep belief in the power of visual beauty to move the soul.

Neoclassicism and the Rise of Academic Art

By the late 18th century, a cultural tide was turning. Across Europe, the ornate sensuality of the Rococo had begun to feel frivolous, even decadent. In its place came a wave of aesthetic reform rooted in Enlightenment ideals — a return to order, clarity, and moral gravity. For Munich, this meant a pivot toward Neoclassicism, a style that looked back to ancient Greece and Rome not just for inspiration, but for instruction. It was no longer enough for art to dazzle; it had to edify, to discipline, to speak the language of reason. And nowhere was this transformation more visible than in the institutions that rose to define Munich’s art world in the 19th century.

The shift began under Elector Charles Theodore (r. 1777–1799), but it was Maximilian I Joseph, the first king of Bavaria, who truly pushed Munich into the modern cultural era. His reign (1806–1825) marked a moment of reinvention, as Bavaria was elevated from electorate to kingdom — and Munich, in turn, sought to position itself as a serious European capital. Art became both a symbol and a tool of this transformation.

The guiding hand behind Munich’s Neoclassical vision, however, belonged to Crown Prince Ludwig, later King Ludwig I of Bavaria (r. 1825–1848). A passionate lover of antiquity and tireless patron of the arts, Ludwig envisioned Munich as a “new Athens on the Isar.” His goal was nothing short of civic and cultural rebirth. To that end, he launched a massive program of architectural and artistic development, employing leading architects like Leo von Klenze and commissioning buildings that would fundamentally reshape the city’s identity.

Nowhere is this ambition clearer than in the Königsplatz, a grand Neoclassical square designed by von Klenze as a monumental stage for the arts. Flanked by the Glyptothek and the Staatliche Antikensammlungen (State Collections of Antiquities), the square became Munich’s answer to Rome’s Capitoline Hill or Paris’s Louvre courtyard. The Glyptothek, completed in 1830, was the first museum in the world dedicated solely to ancient sculpture. Its marble halls were a manifesto in stone — an assertion that Bavaria, through the power of art, belonged to the lineage of classical greatness.

Ludwig’s efforts weren’t limited to architecture. In 1808, under the earlier initiative of Maximilian I, the Academy of Fine Arts Munich (Akademie der Bildenden Künste München) was formally institutionalized, although its origins trace back to the mid-18th century. By the 19th century, it had evolved into one of Europe’s premier centers of academic art education. Its curriculum emphasized drawing from life, mastering anatomy, and understanding classical composition — all hallmarks of Neoclassical theory. Students were trained in a rigorous style that balanced intellectual control with technical precision, preparing them to serve the needs of court, church, and bourgeois collectors alike.

Neoclassicism in Munich wasn’t just an aesthetic; it was a philosophy of statehood. Artists like Peter von Cornelius, Wilhelm von Kaulbach, and Joseph Karl Stieler were not only painters but visual narrators of national destiny. Cornelius, for example, became a central figure in Ludwig’s mural programs, overseeing vast allegorical and historical frescoes in institutions like the Ludwigskirche and the Alte Pinakothek. His art fused Renaissance grandeur with a stern moralism, intended to elevate public taste and reinforce civic virtue.

Stieler, by contrast, brought a softer, more intimate sensibility to Ludwig’s cultural agenda. As court painter, he created the famous “Gallery of Beauties” (Schönheitengalerie) in Nymphenburg Palace — a series of idealized yet individualized portraits of women from various social backgrounds. These portraits combined Neoclassical grace with a proto-Romantic attention to personality, showing that even within an age of order, the personal and emotional could still be honored.

The crown jewel of Ludwig’s cultural reign, however, was the Alte Pinakothek, completed in 1836 — one of the oldest public art museums in the world. Designed again by Leo von Klenze, the museum housed the royal painting collections, showcasing Old Masters from Dürer to Rubens. Its creation was a radical gesture: to place great art in a public institution, accessible to students, artists, and citizens alike. It was a democratization of taste, even as it reinforced a hierarchy of styles and values rooted in classical idealism.

This flourishing of state-supported art also had a paradoxical effect: it calcified. By the mid-19th century, the academic system in Munich had become rigid, even oppressive. Innovation was stifled beneath the weight of tradition. History painting, the highest genre in academic hierarchies, dominated at the expense of genre scenes, landscapes, or emerging forms of realism. Young artists began to chafe at the constraints of idealized anatomy and heroic narrative.

Still, for decades, Munich was a magnet for talent across Europe. Russian, Scandinavian, and Central European painters flocked to the Academy. They studied casts of antique statues, debated composition under candlelight, and filled the city’s cafés with sketches and polemics. What Paris was to Impressionism, Munich was to academic excellence. Its art scene, deeply institutional and ideologically coherent, created a powerful — if eventually brittle — model of state-sanctioned beauty.

As the 19th century wore on, however, the cracks would widen. A new generation, impatient with moralizing murals and Greco-Roman ideals, would push back. The seeds of rebellion were germinating in the very academies that trained them — and soon, Munich would explode into modernism.

The Munich Secession and Jugendstil

By the final decades of the 19th century, the finely sculpted world of academic art in Munich was cracking under its own weight. For decades, the city had flourished as a stronghold of classical training and historical painting, but a new generation of artists — younger, restless, and plugged into international currents — was no longer content to render gods and generals in the prescribed idioms of Neoclassicism. They wanted to paint life as it was, and as it could be. In 1892, that hunger erupted into open revolt with the founding of the Munich Secession — a bold rejection of institutional dogma that would help launch Munich into the avant-garde and introduce the world to Jugendstil, one of the most enchanting and rebellious styles of the modern era.

The Munich Secession didn’t emerge in a vacuum. It was part of a broader wave of artistic secessions across Europe — most famously in Vienna and Berlin — that sought to liberate artists from the control of academic juries and state-funded exhibitions. In Munich, frustration had been simmering for years. The Academy’s conservative grip on public taste, combined with its tendency to reward monumental historical canvases, had marginalized more intimate, decorative, and experimental work.

Led by figures like Franz von Stuck, Fritz von Uhde, and Lovis Corinth, the founding members of the Munich Secession declared their intent to exhibit independently, without the censorship of academic juries. Their first exhibition in 1893 was a triumph, both critically and commercially. For the first time, Munich audiences were exposed to Symbolist themes, Impressionist brushwork, and a daring exploration of mood, psychology, and sensuality that defied the moral certitudes of the academic tradition.

Among the most emblematic artists of this breakaway generation was Franz von Stuck, whose work straddled myth, erotica, and existential dread. His painting The Sin (1893), a haunting image of a nude woman coiled with a serpent, became a kind of totem for the movement. With its dark palette, luminous flesh, and fusion of classical and Symbolist elements, it captured the tension at the heart of the Munich Secession: the simultaneous embrace of tradition and rebellion. Stuck was also a gifted architect and designer; his Villa Stuck, built in 1898, remains a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) — a living embodiment of Jugendstil ideals, from its painted ceilings to its sculpted door handles.

And what exactly was Jugendstil? Named after the Munich-based magazine Die Jugend (founded in 1896), this German-language Art Nouveau movement was more than a style — it was a philosophy of unity. It rejected the hierarchy between “high” and “applied” arts, advocating instead for an integration of painting, graphic design, architecture, furniture, typography, and even fashion. Its visual language was organic and fluid: undulating lines, botanical motifs, and symbolic female figures dominated its canvases and objects alike. It was both romantic and radical, embracing beauty not as decoration, but as a means of personal and social transformation.

In Munich, Jugendstil took root not only in paintings and posters but in the very fabric of the city. Buildings such as the Müllersches Volksbad (a public bathhouse built in 1901), the Prinzregententheater, and numerous private residences in Schwabing and Bogenhausen reflect Jugendstil’s curving lines, stylized ornamentation, and love of craftsmanship. Architects like Richard Riemerschmid and August Endell worked closely with designers and artists, erasing the borders between disciplines. A doorway might echo the curve of a theater curtain; a teacup might reflect the shape of a leaf. Beauty became immersive.

One of the central gathering places for this new aesthetic was the neighborhood of Schwabing, Munich’s bohemian quarter, where artists, poets, and students mingled in cafes, studios, and salons. This was the era of Stefan George and Rainer Maria Rilke, of Wassily Kandinsky arriving in 1896 and absorbing the Symbolist ethos that would soon erupt into abstraction. Schwabing pulsed with intellectual energy. It was cosmopolitan, sexually permissive, and artistically restless — the closest Munich ever came to Parisian Montmartre.

The Munich Secession and Jugendstil were not purely aesthetic revolts. They carried with them a critique of industrial modernity, a yearning for a more spiritual, holistic way of life. This tension between nature and machine, between body and soul, gave Jugendstil both its lyrical beauty and its fragility. It was always on the edge of disappearing — too sincere, too refined, too intimately tied to a moment.

By the early 20th century, the movement began to fragment. Some artists, like Kandinsky, pushed further into abstraction, founding the Phalanx Group and laying the groundwork for Der Blaue Reiter. Others, like Stuck, grew more conservative or became absorbed into teaching roles. The rise of Expressionism, Cubism, and Futurism rendered Jugendstil’s curvilinear grace passé. And yet, the movement’s legacy endured — not just in posters or balconies, but in the idea that art could reshape life.

Munich’s embrace of the Secession and Jugendstil marked a profound turning point. The city, long seen as a bastion of tradition and royal patronage, had reinvented itself as a hub of modernism. It opened its doors to new media, new forms, and new voices. And in doing so, it gave birth to something larger than a style: a culture of artistic independence that would echo through the 20th century and beyond.

Blue Rider and the Birth of Expressionism

At the dawn of the 20th century, Munich was already an established capital of art — steeped in tradition, energized by rebellion, and teeming with intellectual crosscurrents. The Secession and Jugendstil had shattered the constraints of academic painting, opening a path for experimentation and symbolism. But it was the emergence of Der Blaue Reiter — The Blue Rider — in 1911 that would propel Munich onto the international stage as the birthplace of a new language of modernism: Expressionism.

The Blue Rider was not a school or a style. It was a movement of spirit — a coalition of artists, writers, and thinkers united not by aesthetic rules, but by a shared belief in art’s spiritual dimension. It was, at its core, a reaction: against naturalism, against materialism, against the idea that art should merely reflect the visible world. For the Blue Riders, art was a gateway to the invisible — to emotion, intuition, and the inner truths that lay beneath appearances.

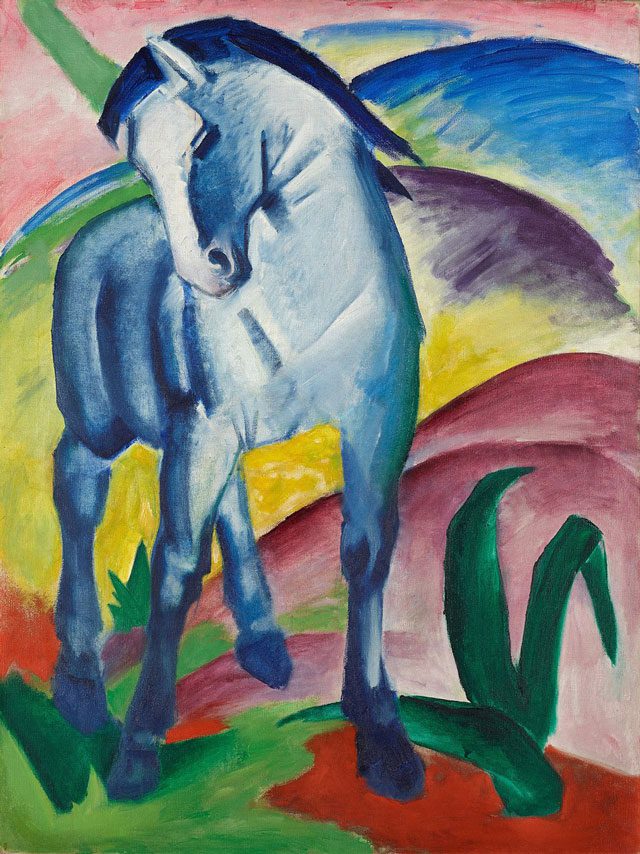

The movement was founded by two visionaries: Wassily Kandinsky, a Russian painter and theorist who had settled in Munich in 1896, and Franz Marc, a German artist whose luminous depictions of animals evoked a kind of mystical pantheism. Both men were deeply influenced by Theosophy, music, and non-Western art, and both believed that color, form, and abstraction could evoke the metaphysical in a way that realism never could.

The name “Blue Rider” itself was deliberately ambiguous. According to Kandinsky, it was inspired simply by his love of blue and Marc’s fascination with horses. But the symbolism runs deeper: the rider becomes a metaphor for the artist as spiritual seeker, galloping through the chaos of modernity toward transcendence. And blue — a color Kandinsky associated with depth, distance, and the eternal — was the hue of the soul.

In 1911, the group published its first (and only) almanac, Der Blaue Reiter Almanach, a radical and eclectic collection of essays, reproductions, and manifestos. It included everything from folk art and children’s drawings to African sculptures and medieval icons. The message was clear: the old hierarchies of “high” and “low” art were irrelevant. What mattered was expressiveness, authenticity, and inner necessity — Kandinsky’s term for the driving impulse behind true art.

Exhibitions followed — first in Munich, then throughout Germany — showcasing the explosive energy of the Blue Rider circle. Alongside Kandinsky and Marc were artists like Gabriele Münter, a pioneering painter and one of the few prominent women in the movement; August Macke, whose vibrant scenes of leisure shimmered with color and motion; Alexej von Jawlensky, with his haunting, mask-like portraits; and Paul Klee, the lyrical mystic who would later become a foundational figure at the Bauhaus.

Their styles varied wildly — from Marc’s crystalline blue horses to Kandinsky’s floating geometric symphonies — but all shared a rejection of mimetic representation and a search for spiritual resonance. They were not painting what they saw, but what they felt. A landscape became a symphony; a horse, a hymn. Their use of color was intuitive, symbolic, and often ecstatic. The results were electrifying — and controversial.

Munich, for a time, was the epicenter of this artistic revolution. The city’s cafes, salons, and studios buzzed with debate. In Schwabing, the Blue Riders gathered in Münter’s home — the so-called “Russenvilla” — discussing music, synesthesia, and the future of art. Kandinsky, ever the theorist, lectured at the Phalanx School and wrote Concerning the Spiritual in Art, one of the first major texts to articulate a philosophy of abstraction. The book would become a manifesto for 20th-century modernism, influencing generations of artists from Rothko to Pollock.

But this golden moment was short-lived. In 1914, with the outbreak of World War I, the movement collapsed. Kandinsky, a Russian citizen, was forced to leave Germany. Marc and Macke volunteered for the army and were both killed in combat — Marc at Verdun, Macke on the Western Front. Their deaths cast a shadow over the movement, imbuing it with a sense of martyrdom. The luminous optimism of the Blue Rider gave way to the darker tones of German Expressionism, which would later emerge in Berlin and Dresden with more angst, more anger, and more nihilism.

Even so, the legacy of the Blue Rider was profound. The group had not only anticipated abstraction but had framed it as a spiritual necessity. They had expanded the boundaries of what art could be — integrating non-Western forms, celebrating the unconscious, and elevating the expressive over the representational. In many ways, they planted the seeds for the Bauhaus, Surrealism, and Abstract Expressionism.

In Munich, the memory of the Blue Rider endures. The Lenbachhaus Museum, which houses the world’s largest collection of Blue Rider works, is a shrine to this extraordinary moment. Its galleries pulse with Marc’s red deer, Kandinsky’s glowing orbs, and Münter’s expressive portraits. It is one of the few places on earth where you can feel, viscerally, the revolution they dreamed of — a world where art is not decoration, but revelation.

Nazi Art Policy and the “Degenerate Art” Exhibition

In the summer of 1937, a new exhibition opened in Munich that would shock the world and devastate the German art scene. Titled “Entartete Kunst” — Degenerate Art — it was a grotesque, state-sponsored spectacle designed to mock and condemn the very modernist movements that had once flourished in the city. On the walls of a crowded, intentionally chaotic display, hung the works of artists once celebrated in Munich’s cafés, academies, and museums: Kandinsky, Marc, Klee, Nolde, Kirchner. Their paintings were defaced with hostile captions. Their names were vilified. And their legacy — carefully cultivated over decades — was now publicly dismantled.

The rise of Nazism brought with it not only political terror but a totalitarian vision of culture. Adolf Hitler, himself a failed painter who had once been rejected by the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, carried a deep personal grudge against modernist art. He viewed Expressionism, Dada, Cubism, Surrealism — essentially anything non-representational or emotionally raw — as decadent, un-German, and racially corrupt. Art, in the Nazi worldview, was to serve the Volk: it was to be realistic, heroic, racialized, and above all, obedient.

Munich — once the birthplace of the Blue Rider — was transformed into what Hitler ominously declared the “Capital of German Art.” The city, long associated with avant-garde culture, now became the heart of Nazi aesthetic propaganda. New institutions were repurposed or built to reflect the regime’s vision. Chief among them was the Haus der Deutschen Kunst (House of German Art), designed by architect Paul Ludwig Troost in a stripped-down neoclassical style. Completed in 1937, it was the stage for the Great German Art Exhibition (Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung) — an annual showcase of officially sanctioned art that embodied Nazi ideals: idealized peasants, Aryan athletes, mythic warriors, and pastoral landscapes.

The opening of the Haus der Deutschen Kunst was no ordinary affair. Hitler himself gave the keynote address, declaring the death of modern art and the rebirth of a racially pure aesthetic. Just a few blocks away, the “Degenerate Art” exhibition opened as a perverse counterpoint — a traveling exhibition that began in Munich and would be seen by millions across Germany. It was, in its own twisted way, a propaganda success. Visitors poured in — some to mock, others to mourn. The display was intentionally chaotic: works were hung crookedly, lighting was poor, rooms were overcrowded, and mocking slogans scrawled across the walls. Paintings were labeled as the product of madness, communism, or Jewish degeneracy. Among the pieces on view were works by Paul Klee, Emil Nolde, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Otto Dix, and, of course, Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc.

The irony was bitter. Franz Marc, whose work was included in the show, had died serving the German army in World War I. Emil Nolde, a devout nationalist and early supporter of the Nazis, saw over a thousand of his works confiscated. The regime’s criteria were not only aesthetic, but deeply racialized and ideologically incoherent. Jewish artists were automatically banned, regardless of style. Abstract painters were vilified as mentally ill. Surrealists were condemned as enemies of the state. The art world became a field of persecution.

The purge extended beyond exhibitions. Works were removed from public collections — including the Bavarian State Collections, which saw hundreds of paintings confiscated or destroyed. Some were sold on the international market to raise funds for the regime. Others were burned in secret. The Lenbachhaus, once a sanctuary of Expressionism, was largely gutted. Museums, galleries, and schools were purged of “undesirable” works and staff. Professors and curators were forced to conform or be dismissed.

Munich’s once-vibrant artistic ecosystem was thus decimated from within. The Bauhaus had already been closed in 1933. The avant-garde diaspora — artists, intellectuals, musicians — fled abroad, many to France, Britain, or the United States. Those who stayed either conformed, fell silent, or suffered. The city that had once incubated some of Europe’s most radical artistic experiments was now a mausoleum of aesthetic conformity.

And yet, paradoxically, the regime’s attempt to erase modernism preserved it. The “Degenerate Art” exhibition, for all its cruelty, gave modernist work a new audience. The very act of banning and condemning these artists elevated their cultural status. Many visitors to the exhibition were shocked not by the art, but by the regime’s vulgarity. After the war, the works that survived became rallying points in the rebuilding of European art history — symbols of resistance, integrity, and human imagination.

Today, the legacy of this chapter is carefully preserved in Munich. The Haus der Kunst (formerly the Haus der Deutschen Kunst) still stands, but its mission has radically changed. It is now a center for contemporary and critical art, often hosting exhibitions that grapple directly with its fascist past. The Lenbachhaus has reclaimed its Expressionist heritage, and the city’s museums now openly display works once labeled degenerate — not only as masterpieces, but as emblems of resilience.

This period remains one of the most painful in Munich’s art history — a reminder that art is never just about beauty, but about power, politics, and freedom. It shows how fragile the creative spirit can be under authoritarianism — and how fiercely it fights to survive.

Post-War Recovery and Avant-Garde Revival

In the spring of 1945, as Allied forces moved into Munich, they found a city in ruins — its historic center devastated by bombs, its art institutions hollowed out, and its cultural memory fragmented by twelve years of totalitarian control. The so-called “Capital of German Art” had become a city haunted by the ghosts of propaganda, war, and suppression. And yet, in the rubble, seeds of rebirth were already taking root.

The immediate post-war years in Munich were defined by cleansing and recovery. The Allied denazification programs dismantled Nazi cultural institutions, but left behind a generation of traumatized artists, many of whom had been silenced, exiled, or marginalized. Galleries and museums were slowly reopened, but with collections decimated and morale low. There was a sense that the city had to start over, not only materially, but morally.

For many artists in Munich, this blank slate was both a burden and an opportunity. They faced the dual task of reckoning with the past and forging a new visual language that could address the horrors of the Holocaust, the absurdities of ideology, and the existential void left by total war. The post-war avant-garde emerged not in grand gestures, but in experiments, provocations, and quiet revolutions.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Munich saw the formation of several artist collectives and exhibition spaces that rejected both academic tradition and nationalist aesthetics. Among the earliest and most influential was the ZEN 49 group, founded in 1949 by abstract painters such as Rupprecht Geiger, Fritz Winter, and Willi Baumeister. While based partly in Munich and partly in Stuttgart, ZEN 49 marked an important step in the rehabilitation of abstraction — a style demonized by the Nazis but embraced now as a symbol of intellectual and spiritual freedom. These artists were deeply engaged with international movements like Tachisme, Informel, and Abstract Expressionism, positioning themselves in conversation with artists from Paris and New York.

Meanwhile, Munich became a node in the sprawling network of Fluxus, a radical movement of the 1960s that blended visual art, music, performance, and absurdity. Though Fluxus was more active in cities like Wiesbaden and Düsseldorf, key figures like Joseph Beuys and Nam June Paik performed in Munich, where a small but energetic scene of experimental artists and students embraced the group’s ethos: art as life, life as provocation. Performances were held in unconventional spaces — lofts, lecture halls, even sidewalks. The goal was not to decorate the world, but to disrupt it.

Parallel to these experimental scenes, Munich also nurtured a revival of photography, led by artists like Heinrich Riebesehl and Floris Neusüss, as well as a resurgence of conceptual art and critical installation work in the 1970s. The city’s many art schools, particularly the Akademie der Bildenden Künste München, adapted to the times by hiring more progressive faculty and encouraging interdisciplinary exploration. Sculpture, video art, feminist performance — all found tentative but growing space in Munich’s evolving ecosystem.

One of the most striking features of Munich’s post-war revival was its redefinition of public space. With so much of the city center rebuilt after the war, artists and architects were given rare opportunities to reshape Munich’s visual identity from the ground up. This was not always done radically — Munich, after all, remained more conservative than Berlin or Cologne — but it opened new terrain for public art, modernist facades, and urban design informed by cultural memory. Sculptors like Eduardo Chillida and Fritz Koenig contributed monumental works to public plazas and university campuses, blending abstraction with civic reflection.

Meanwhile, the city’s museums underwent a slow but steady transformation. The Lenbachhaus, once hollowed out by the Nazi purge, began actively rebuilding its collection of Blue Rider and Expressionist works, aided by key donations and a renewed scholarly focus on modernism. The Haus der Kunst, stripped of its fascist function, struggled for years with its ideological baggage before emerging in the late 1990s as a space for global contemporary art, often staging critical exhibitions that addressed its own fraught history. This recontextualization of institutional memory became central to Munich’s post-war cultural identity: a commitment to remember, rebuild, and rethink.

By the 1980s and 1990s, Munich had regained its standing as a major cultural hub, albeit a quieter, more introspective one than during the Jugendstil or Blue Rider years. Its art scene was characterized not by flamboyant movements but by diversity, reflection, and professionalism. Commercial galleries proliferated. Artist-run spaces thrived in repurposed buildings. International biennials, design fairs, and academic conferences brought global attention, but the mood was often one of understated confidence rather than radical rupture.

This era also saw the rise of postmodern tendencies in Munich’s art, particularly in the work of artists like Gerhard Merz, whose minimalist installations interrogated space, language, and architectural authority. Meanwhile, younger generations explored themes of memory, media, and migration, echoing broader European trends but grounded in Munich’s specific post-war context.

The legacy of Munich’s post-war art scene is not one of flamboyant manifestos or market-driven spectacle, but of slow, deliberate healing through creativity. It is a city where museums themselves are texts, where performance art can be a form of protest or mourning, and where abstraction became, once again, a sign of liberation. It is also a city that has never fully outrun its past — and perhaps wisely so. Instead of pretending to forget, Munich has made memory part of its aesthetic DNA.

Museums and Institutions – Guardians of Heritage

Few cities in Europe can claim a museum landscape as rich and interconnected as Munich’s. From Old Master galleries housed in stately 19th-century halls to cutting-edge contemporary art centers grappling with digital culture and postcolonial critique, Munich’s institutional art scene is not simply a repository of objects — it is a living archive, a space of debate, education, and memory. These institutions are the city’s visual soul, bearing witness to centuries of artistic evolution and cultural transformation.

At the heart of this landscape lies the Kunstareal, Munich’s designated “art district,” an expansive neighborhood in Maxvorstadt where the city’s major museums, universities, and galleries are clustered in walkable proximity. Here, visitors move not only across physical spaces, but across epochs — from medieval devotional art to experimental media installations. The Kunstareal isn’t just an urban plan; it’s a philosophy. Art, in Munich, is civic infrastructure.

Alte Pinakothek – The Temple of the Old Masters

Any tour of Munich’s art institutions begins with the Alte Pinakothek, one of the oldest and most prestigious art museums in the world. Commissioned by King Ludwig I and designed by Leo von Klenze, it opened in 1836 as a radical new model of a public museum — meant to educate, elevate, and unify citizens through shared cultural heritage. Its grand, light-filled halls display a who’s who of European painting from the 14th to the 18th centuries: Dürer, Rubens, Rembrandt, Raphael, Titian, and Van Dyck.

What sets the Alte Pinakothek apart isn’t just the quality of its holdings, but its emphasis on continuity. The collection doesn’t isolate national schools but places them in dialogue. A room of Italian Renaissance works flows into German panel paintings; a Rubens wall spills into Dutch realism. This curatorial strategy speaks to Munich’s identity: not isolated, but deeply interwoven with European currents.

Neue Pinakothek – Bridging the Classical and the Modern

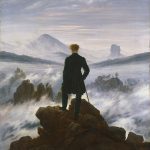

Directly across the street once stood the Neue Pinakothek, founded in 1853 and focused on 19th-century art. Though currently under renovation (as of the 2020s), its collection represents a pivotal transitional era: Romanticism, Realism, Impressionism. Here, one finds Caspar David Friedrich, Gustave Courbet, Édouard Manet, and Vincent van Gogh — artists who laid the groundwork for the ruptures of the 20th century.

The Neue Pinakothek embodies Munich’s dual allegiance to academic heritage and stylistic rebellion. It holds works from both establishment figures and those who challenged them, echoing the very tensions that once split the Munich Secession from the Academy. When it reopens, it is expected to offer an even more expansive lens on this dynamic, potentially incorporating overlooked female artists and colonial critiques into its new narratives.

Pinakothek der Moderne – A 21st-Century Cathedral

Opened in 2002, the Pinakothek der Moderne is Munich’s declaration that history does not end in 1900. A sleek, minimal structure designed by Stephan Braunfels, the museum brings together four major disciplines under one roof: modern and contemporary art, architecture, design, and works on paper. It’s not merely a museum — it’s a cultural ecosystem, where Picasso and Beuys share a home with Bauhaus chairs, conceptual blueprints, and 21st-century digital art.

The modern art collection is particularly robust, featuring Paul Klee, Max Beckmann, Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke, Neo Rauch, and international figures like Dan Flavin, Andy Warhol, and Cindy Sherman. Exhibitions here are often bold, unafraid to tackle contemporary issues — climate, gender, surveillance — and serve as a barometer for where visual culture is headed.

Lenbachhaus – The Soul of the Blue Rider

If the Alte Pinakothek is the seat of power, the Lenbachhaus is the heart — intimate, evocative, and emotionally charged. Housed in the former villa of painter Franz von Lenbach, the museum is best known for its world-leading collection of Blue Rider art: Kandinsky, Marc, Münter, Macke, and Jawlensky. These works are more than historic; they are local legends.

But the Lenbachhaus is not mired in nostalgia. A dramatic 2013 renovation and expansion brought it into the 21st century, and it now curates major contemporary exhibitions alongside its modernist core. It also takes seriously its commitment to inclusivity and reinterpretation, regularly staging exhibitions that reframe Munich’s artistic canon through feminist, queer, and decolonial lenses.

Haus der Kunst – From Fascism to Global Contemporary

No museum in Munich carries more historical baggage than the Haus der Kunst, built by the Nazis in 1937 to house state-sanctioned art. For decades after the war, the building stood as a monumental reminder of fascist aesthetic ideology — neoclassical, imposing, and ideologically fraught. But beginning in the 1990s, the Haus der Kunst undertook a dramatic reinvention, becoming one of Germany’s most important venues for global contemporary art.

Under directors like Okwui Enwezor, the museum became a platform for artists from the Global South, for postcolonial critique, for large-scale retrospectives of figures like Ai Weiwei and El Anatsui. The building itself was never hidden — its past was acknowledged, critiqued, and integrated into its programming. In this way, the Haus der Kunst became a model for how institutions can confront history without being defined by it.

Other Pillars: Museum Brandhorst, Bavarian National Museum, Villa Stuck

Munich’s institutional richness doesn’t stop with the Pinakotheken. The Museum Brandhorst, opened in 2009, houses a world-class collection of contemporary art, particularly strong in American postwar painting — including the largest group of Cy Twombly works outside the U.S. The Bavarian National Museum, often overlooked, is a treasure trove of decorative arts, folk culture, and medieval sculpture, offering a broader social and material context to Munich’s fine art legacy. And the Villa Stuck, home of Jugendstil master Franz von Stuck, is both museum and gesamtkunstwerk — a total aesthetic environment and shrine to a vanished era.

Together, Munich’s museums form more than a cultural infrastructure — they represent a collective memory, a conversation across centuries. They are spaces where the past is curated, the present is interrogated, and the future is envisioned. Each institution, in its own way, asks the same question: What does it mean to see — and to remember — in Munich?

Contemporary Art and the Global Stage

In the age of biennials, blockchain, and Instagram, art has become a global language spoken across borders and platforms. But Munich — with its deep historical roots and institutional muscle — hasn’t been left behind. On the contrary, it has emerged as a uniquely poised hub where tradition and innovation collide, producing a contemporary art scene that is both intellectually rigorous and aesthetically bold.

Contemporary art in Munich thrives across multiple registers: in museums and galleries, in public interventions and private collections, in art schools and DIY spaces. What makes the scene particularly rich is its pluralism. There is no single dominant trend or “Munich style” today. Instead, the city fosters a diverse ecosystem, where minimalism coexists with surrealism, conceptualism mingles with digital media, and established stars show alongside emerging voices.

Institutional Powerhouses as Contemporary Engines

Munich’s museums — particularly the Haus der Kunst, Pinakothek der Moderne, and Museum Brandhorst — have become powerful engines for contemporary discourse. The Haus der Kunst, for example, regularly commissions new work from international artists, with an emphasis on non-Western perspectives, diasporic narratives, and postcolonial critique. Under directors like Andrea Lissoni and the late Okwui Enwezor, the museum staged ambitious exhibitions that transcended national frames — spotlighting artists such as El Anatsui, Hito Steyerl, Joan Jonas, and Theaster Gates.

At the Pinakothek der Moderne, contemporary programming is integrated with broader conversations around design, architecture, and media. Exhibitions often reflect current urgencies: climate change, surveillance capitalism, gender fluidity. Meanwhile, the Brandhorst Museum focuses heavily on contemporary painting, photography, and installation, with deep holdings in works by Andy Warhol, Cy Twombly, Isa Genzken, Bruce Nauman, and Kara Walker. Brandhorst’s sleek, color-tiled façade mirrors its mandate: sharp, current, and open-ended.

Munich’s Gallery Scene: Established and Independent

Outside the institutional sphere, Munich’s commercial and alternative gallery scenes continue to shape the city’s contemporary art identity. Established galleries like Barbara Gross Galerie, Galerie Sabine Knust, and Galerie Jo van de Loo represent both blue-chip and emerging artists, often with an emphasis on conceptual rigor and political engagement. These spaces regularly participate in international art fairs, including Art Basel and Frieze, helping to maintain Munich’s presence on the global stage.

Simultaneously, a younger generation of artists and curators is cultivating non-commercial spaces — often in repurposed buildings, former industrial zones, or temporary squats. Collectives like Lothringer 13 Halle, Ruine München, and Loggia offer a more experimental, grassroots approach. These venues emphasize process over product, and are often interdisciplinary: part exhibition space, part laboratory, part gathering point for performance, lectures, and publications.

The Role of the Akademie and New Media

At the pedagogical core of Munich’s contemporary scene remains the Akademie der Bildenden Künste, the Academy of Fine Arts, which continues to attract and produce talent from across Europe and beyond. With programs in painting, sculpture, media art, and interdisciplinary practice, the Academy nurtures critical dialogue and supports experimentation. Alumni often stay in Munich to establish studios, found collectives, or contribute to its teaching network.

A significant thread in Munich’s contemporary scene is the embrace of new media and digital art. Artists working in video, sound, coding, and interactive installation are increasingly visible — both within institutional exhibitions and independent showcases. Munich’s proximity to the creative tech industries — including gaming, design, and software — has allowed for fertile collaborations that blur the line between art and technology.

Art festivals like the Digitalanalog Festival and initiatives at ZKM Karlsruhe (within easy reach) create regional synergy, while local studios explore AI-generated imagery, XR performance, and immersive environments. Munich is no longer just a city of paintings on walls; it’s a city of light, code, sound, and networks.

Public Art and Urban Interventions

Contemporary art in Munich also extends into the urban landscape. From large-scale commissions in subway stations to ephemeral performances in public parks, the city continues to support a robust program of public art. Sculptures by artists like Olaf Metzel and Rita McBride disrupt traditional notions of monumentality, while temporary installations — often part of city-sponsored festivals — bring art into conversation with everyday life.

The Kunst im öffentlichen Raum program (Art in Public Space) is particularly active, funding site-specific projects that range from socially engaged work to architectural interventions. These projects often foreground community participation, environmental concerns, or historical memory, reinforcing the idea that Munich’s contemporary art scene is not just global, but civic.

Private Collections and Patronage

Munich is also home to a number of significant private collectors, many of whom support public exhibitions or open their collections to scholars and the public. Patrons like the Goetz Collection — founded by collector Ingvild Goetz — have been instrumental in supporting contemporary video, photography, and installation art. Housed in a Herzog & de Meuron-designed cube in Oberföhring, the Goetz Collection is a private museum with a public mission: to support the boldest and least commodified edges of contemporary practice.

Challenges and Horizons

Like many European cities, Munich faces questions about accessibility, diversity, and the role of contemporary art in an increasingly polarized cultural landscape. Rising real estate prices and the pressures of tourism risk squeezing out grassroots initiatives. Meanwhile, debates around cultural restitution, colonial legacies, and climate responsibility are reshaping curatorial agendas and funding priorities.

And yet, there’s a sense of quiet resilience in the Munich art scene — a confidence drawn not from trend-chasing, but from centuries of continuity and reinvention. Contemporary artists in Munich are not burdened by their past, but emboldened by it. They move through spaces once occupied by Dürer, Marc, Kandinsky, and Beuys, not in imitation, but in dialogue.

Munich may not scream for attention like Berlin or Venice, but it doesn’t need to. Its contemporary scene is deep rather than loud, cosmopolitan without pretense, and critical without nihilism. It is a city where the future of art is not just imagined — it is carefully, quietly, and beautifully built.

Munich’s Legacy in European Art

Walk through Munich’s city center today, and you’ll find traces of nearly every major chapter in European art history pressed into its architecture, institutions, and atmosphere. Gothic spires rise beside Neoclassical museums; Jugendstil flourishes peek from 19th-century facades; conceptual installations lean into public plazas. It’s a city that doesn’t just contain art — it remembers, confronts, and lives it. Munich’s legacy in European art is not the tale of a single golden age, but of continuity through contradiction, of tradition shaped and reshaped by rebellion.

The city’s cultural identity has always pivoted on its ability to mediate extremes. In the Baroque, it merged Catholic spectacle with political power. In the 19th century, it fused Romantic introspection with academic structure. In the early 20th century, it harbored both utopian abstraction and destructive ideology. And in the wake of war, it chose not to erase its past, but to interrogate it — becoming a case study in how a city can reclaim art as a form of civic truth-telling.

Few cities have been so central to both the rise and suppression of modernism. Munich gave birth to the Blue Rider, fostered Kandinsky and Marc, and offered fertile ground for Expressionism — only to become, under Nazi rule, the epicenter of its repudiation. This duality is Munich’s burden, but also its strength. It has made the city acutely aware that art is never neutral — that it is always entangled with ideology, identity, and power.

Yet Munich’s story is not just about loss and recovery. It is also about continuity — of patronage, education, and a certain humanistic ideal that has survived empires and ideologies. The institutions established under the Wittelsbachs in the 16th and 17th centuries still anchor the city’s cultural infrastructure. The Academy, the Pinakotheken, and the Lenbachhaus form a centuries-spanning dialogue between old and new, sacred and secular, local and international.

This historical depth has allowed Munich to play an unusually long game in the European art world. While cities like Paris and Berlin may dominate headlines, Munich often operates with a quiet but powerful curatorial intelligence — a capacity to shape discourse not through spectacle, but through depth. Whether in the careful rehanging of the Alte Pinakothek’s Flemish masters, the critical recontextualization of the Haus der Kunst, or the pioneering digital installations at the Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich reminds us that legacy is not only what you preserve — but how you evolve it.

Moreover, Munich’s position at the intersection of German, Austrian, Italian, and Eastern European cultural spheres has made it a cultural hinge — a place of encounter and translation. From its medieval beginnings as a crossroads of trade and pilgrimage to its role today in global art fairs and biennials, Munich has always been more outward-facing than it may appear. Its cosmopolitanism is subtle, embedded not in flash, but in fluency — a fluency in history, form, and ideas.

In many ways, Munich’s art history is also a microcosm of Europe’s. It reflects the continent’s ongoing struggle between memory and modernity, form and freedom, reason and feeling. It shows us that the city — as both place and symbol — can be a canvas for the best and worst of human ambition. And yet, in that canvas, we find resilience: in paint, in stone, in movement, in sound.

To understand the art of Munich is to understand not just a series of styles or movements, but a philosophy of looking — a belief that art matters, that it can shape societies, and that it must be reckoned with, whether it consoles or confronts.

In the 21st century, as cities around the world rethink the role of culture in the face of ecological crisis, social change, and digital transformation, Munich remains a critical case study — not as a model to replicate, but as a legacy to engage. Its past is dense, but its present is alive. And its future, like its best artworks, remains open to interpretation.