The Symbolism movement emerged in the late 19th century, flourishing as a reaction to the rigidity of realism and naturalism. It was deeply rooted in the Romantic era’s yearning for imagination, mystery, and emotion. This artistic wave began in France and Belgium during the 1880s, a time when industrialization was rapidly altering societal values. Symbolism sought to counteract the mundane aspects of modern life, emphasizing spirituality and the subconscious.

Literary figures played a crucial role in shaping the ideological foundation of Symbolism. Charles Baudelaire’s poetry, particularly his 1857 work Les Fleurs du mal, was a precursor to the movement’s themes of beauty, decadence, and melancholy. His vision inspired artists to explore profound emotions and metaphysical concepts. Other writers, such as Paul Verlaine and Stéphane Mallarmé, advanced the ideals of Symbolism by rejecting straightforward narrative and embracing poetic ambiguity.

The movement was also heavily influenced by philosophies questioning materialism and promoting introspection. Nietzsche’s ideas on individuality and Schopenhauer’s focus on the will and human desire resonated with Symbolist artists. These philosophies encouraged a shift away from depicting the external world toward illustrating inner thoughts and feelings. This introspective focus set Symbolism apart as a distinctly modern yet mystical art movement.

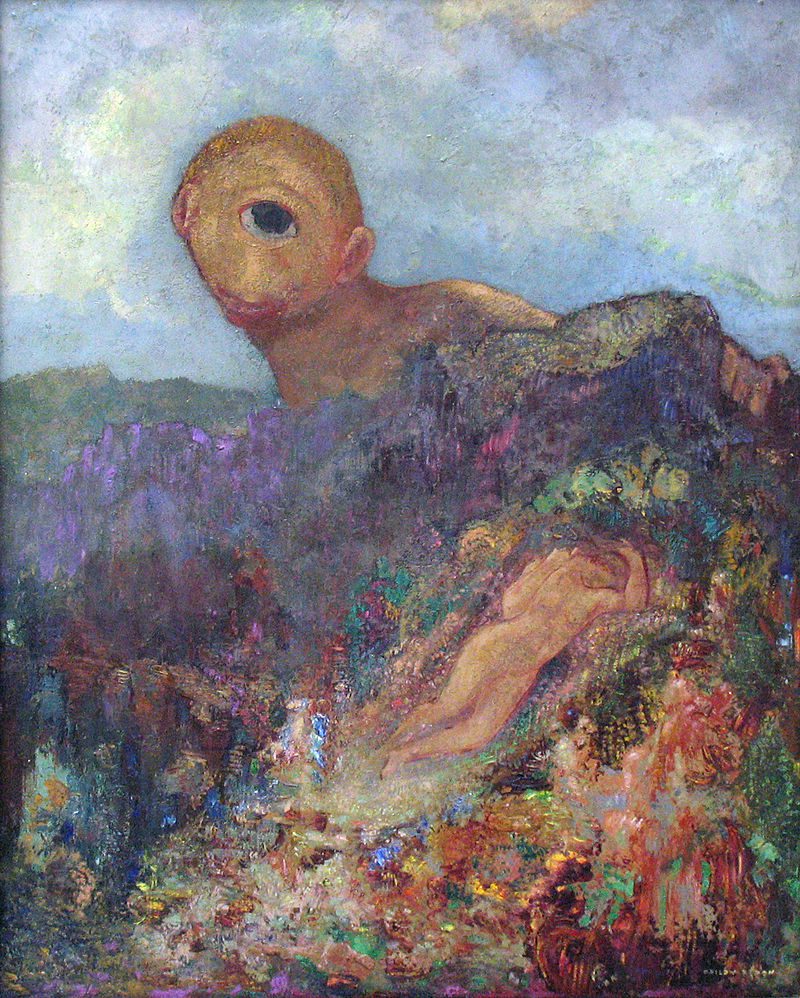

Artists like Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon became early visual pioneers of Symbolism. They turned their backs on the photographic realism dominating contemporary art, instead favoring dreamlike compositions filled with allegory. Their works set the tone for what Symbolism would become—a marriage of imaginative visuals and esoteric meaning that invited viewers to contemplate deeper truths.

Defining Characteristics of Symbolism

Symbolism revolved around capturing the intangible—dreams, emotions, and spiritual realms—through visual art. Artists abandoned realistic depictions of the world, opting instead for abstract and often fantastical imagery. Their works featured rich, saturated colors and forms that conveyed mood rather than physical accuracy. The art was imbued with symbolism, where each object and figure carried layered meanings.

Recurring themes included mysticism, mythology, and the exploration of the subconscious. Symbolist art often depicted otherworldly landscapes, ethereal beings, and scenes steeped in melancholy. Gustave Moreau’s paintings, for example, frequently referenced mythological subjects to convey universal truths about human experience. This thematic focus gave Symbolism its unique voice, setting it apart from other movements of its time.

The aesthetic of Symbolism also emphasized emotional resonance over technical perfection. While previous art movements had prized lifelike precision, Symbolism valued an evocative atmosphere. Odilon Redon’s pastel works, filled with ghostly figures and mysterious flowers, exemplify this approach. His art invited viewers to interpret the meaning behind the imagery, creating a deeply personal experience for each observer.

The rejection of contemporary societal norms was another defining trait of Symbolism. Artists and writers associated with the movement sought to transcend materialism and rationality. Their works often contained elements of mysticism or the occult, reflecting a fascination with the unseen. These characteristics gave Symbolism its reputation as an enigmatic and deeply introspective movement.

Pioneering Figures and Their Contributions

Gustave Moreau, a French painter born in 1826, is often hailed as a father of Symbolism. His works, such as Oedipus and the Sphinx (1864), blended mythological themes with ornate, detailed compositions. Moreau’s career milestones include his appointment as a professor at École des Beaux-Arts, where he influenced a generation of Symbolist artists. His focus on allegorical storytelling made him a pivotal figure in the movement’s development.

Odilon Redon, another French visionary, was born in 1840 and became known for his ethereal and dreamlike works. His charcoal drawings and pastels, including The Eye Like a Strange Balloon (1882), showcased a mastery of the surreal and the symbolic. Redon’s ability to blend the macabre with the sublime earned him acclaim as one of Symbolism’s most innovative artists. His art often explored the boundaries of reality and imagination.

Arnold Böcklin, a Swiss painter born in 1827, contributed significantly to the movement with his hauntingly atmospheric pieces. Works such as Isle of the Dead (1880) captured a sense of foreboding and mystery that became hallmarks of Symbolist art. Böcklin’s paintings resonated with the movement’s interest in mortality and the metaphysical. His influence extended beyond painting, inspiring composers like Sergei Rachmaninoff to create works based on his imagery.

The collaborations and relationships within the Symbolist community also shaped its trajectory. Moreau’s mentorship of artists like Georges Rouault ensured the continuity of Symbolist ideals into the 20th century. Meanwhile, literary figures like Mallarmé and Verlaine interacted closely with visual artists, fostering a vibrant, interdisciplinary exchange of ideas that enriched the movement.

Symbolism’s Relationship with Literature and Music

The Symbolist movement had profound ties to literature, particularly poetry, where its ideals first gained prominence. Writers like Charles Baudelaire and Paul Verlaine emphasized mood, emotion, and suggestion over direct narrative. Their works inspired visual artists to adopt similar approaches, creating art that invited interpretation rather than dictating meaning. This synergy between the arts became a defining feature of Symbolism.

Stéphane Mallarmé’s poetry epitomized the Symbolist ethos, blending complex imagery with abstract themes. His work influenced artists to explore similar abstract expressions in their paintings and drawings. The dialogue between poetry and visual art was not merely thematic but often collaborative, with artists illustrating poems or creating works inspired by literary texts. This interplay enriched both mediums and expanded Symbolism’s reach.

Music also played a significant role in the Symbolist movement. Composers like Claude Debussy drew inspiration from Symbolist literature and visual art. Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (1894), inspired by Mallarmé’s poem, captured the ethereal and dreamlike quality of the movement. Richard Wagner’s operatic works, with their emphasis on myth and emotion, resonated deeply with Symbolist ideals.

Symbolist theater emerged as another interdisciplinary expression of the movement’s themes. Plays by Maurice Maeterlinck, such as Pelléas et Mélisande (1892), incorporated symbolism and allegory to evoke emotion and thought. The integration of music, literature, and visual art created a cohesive cultural wave that defined Symbolism as a holistic movement, not just an art style.

International Reach and Evolution of Symbolism

While Symbolism originated in France and Belgium, its influence quickly spread across Europe. In Russia, the movement inspired a new generation of artists and writers, including figures like Mikhail Vrubel. Vrubel’s works, such as The Demon Seated (1890), combined Symbolist themes with Russian folklore, creating a uniquely regional expression of the movement. This cross-pollination of ideas enriched Symbolism’s global impact.

The Netherlands also embraced Symbolism, with artists like Jan Toorop incorporating its ideals into their works. Toorop’s painting The Three Brides (1893) featured mystical and allegorical elements characteristic of Symbolism. In Austria, Gustav Klimt’s decorative and emotive style bore the hallmarks of Symbolist influence, particularly in works like The Kiss (1907-1908). These artists demonstrated how Symbolism adapted to different cultural contexts.

Symbolism’s reach extended beyond painting, influencing movements like Art Nouveau and Surrealism. The fluid lines and intricate details of Art Nouveau owed much to Symbolist aesthetics. Meanwhile, the introspective and dreamlike qualities of Surrealism can be traced back to Symbolist explorations of the subconscious. The movement’s legacy persisted long after its peak, shaping the trajectory of modern art.

The global adoption of Symbolism underscored its versatility and universality. Its themes of spirituality, emotion, and the metaphysical resonated with artists and audiences across cultures. As the movement evolved, it laid the groundwork for new artistic expressions, ensuring its continued relevance in the ever-changing world of art.

Symbolism’s Role in Challenging Traditional Norms

Symbolism represented a bold departure from traditional art forms, challenging established norms and conventions. It rejected the objective realism that had dominated art since the Renaissance, instead embracing subjective interpretation and emotion. This shift encouraged artists to delve into their personal experiences and inner worlds, redefining the purpose of art. By doing so, Symbolism questioned the very nature of artistic representation.

The movement’s emphasis on spirituality and mysticism contrasted sharply with the materialism of the 19th century. Symbolist artists often explored themes of mortality, transcendence, and the supernatural, offering a counterpoint to the era’s focus on industrial progress. This focus on the intangible made Symbolism a deeply philosophical and introspective movement, inviting viewers to reflect on life’s deeper meanings.

Symbolism also challenged societal expectations of art’s role in addressing social issues. While movements like Realism and Impressionism focused on depicting everyday life, Symbolism turned inward. Its artists sought to create works that transcended the mundane, offering viewers a glimpse into a more poetic and mystical realm. This approach reshaped the way art was perceived and appreciated.

Critical reception of Symbolism during its height was mixed, with some praising its innovation and others dismissing it as overly esoteric. Critics often misunderstood its abstract and enigmatic nature, viewing it as inaccessible. However, this resistance only reinforced Symbolism’s role as a revolutionary movement, unafraid to challenge the artistic status quo.

Legacy and Influence of Symbolism in Modern Art

Symbolism’s influence extended far beyond its late 19th-century origins, leaving an indelible mark on modern art. Its exploration of the subconscious paved the way for Surrealism, a movement that would dominate the 20th century. Artists like Salvador Dalí and Max Ernst drew heavily on Symbolist themes, blending dreamlike imagery with symbolic meaning. This continuity underscored Symbolism’s enduring relevance.

The movement also influenced Abstract Expressionism, particularly in its focus on emotion and the intangible. Artists such as Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock echoed the Symbolist ethos of expressing inner thoughts through abstract forms. Their works embodied the movement’s legacy of prioritizing emotion over representation, pushing the boundaries of art even further.

Contemporary art continues to draw inspiration from Symbolist ideals. Themes of spirituality, mysticism, and the metaphysical remain prevalent in many modern works. Artists today often revisit Symbolist concepts, adapting them to new mediums and cultural contexts. This ongoing dialogue highlights Symbolism’s ability to resonate across generations.

Symbolism’s impact is also evident in popular culture, from film to literature. Its emphasis on mood and atmosphere has influenced filmmakers, writers, and musicians. By redefining the relationship between art and imagination, Symbolism established itself as a cornerstone of artistic innovation, inspiring creativity in countless forms.

Key Takeaways

- Symbolism emerged in the 1880s as a reaction to realism and naturalism, emphasizing spirituality and the subconscious.

- The movement featured pioneering artists like Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Arnold Böcklin.

- Symbolism’s interdisciplinary nature connected it to literature, music, and theater, fostering a rich cultural exchange.

- The movement’s themes of mysticism and introspection influenced modern art movements like Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism.

- Symbolism’s legacy continues to inspire contemporary artists, showcasing its timeless appeal.

FAQs

- What is Symbolism in art? Symbolism is an art movement that emphasizes spirituality, dreams, and the subconscious over realism.

- Who were key artists in the Symbolism movement? Notable figures include Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Arnold Böcklin.

- How did Symbolism influence modern art? It paved the way for movements like Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism by exploring emotional and metaphysical themes.

- What themes define Symbolist art? Key themes include mysticism, mythology, mortality, and the exploration of the subconscious.

- Where did Symbolism originate? The movement began in France and Belgium during the 1880s.