For centuries, the Swan Maiden has captivated artists and audiences alike, appearing again and again in stunning visual works that bring the ancient myth to life. The image of a woman caught between human and swan, poised on the edge of transformation under moonlight, has inspired painters, sculptors, and stage designers from the 1800s through the modern era. This enduring myth resonates because it reflects universal themes of freedom and confinement, identity and loss, all rendered in a visual language that transcends time. Let’s explore how the Swan Maiden’s story has been interpreted in visual art, from classical painting to contemporary sculpture, revealing the powerful symbolic and aesthetic ideas that continue to make her a compelling subject.

The Myth Behind the Muse – Who Is the Swan Maiden?

The Swan Maiden myth typically involves a supernatural woman who transforms between swan and human, often through a feathered cloak or robe. In many cultural traditions, a man finds the Swan Maiden bathing, steals her cloak to prevent her return to the sky, and compels her into marriage, only to have her escape when she regains her garment. This visual tale offers rich material for artists because it encapsulates movement, dual identity, and emotional tension in one striking image. The myth’s narrative components—the stolen cloak, the reluctant bride, the moment of flight—are almost cinematic, and painters have seized on these moments to create works that explore both narrative and form.

Common Narrative Structure Across Cultures

Artists have drawn from a range of cultural sources to portray the Swan Maiden, finding in this myth a universal visual vocabulary. In Norse-inspired works, for example, Valkyrie-like figures with feathered cloaks hover between sky and sea, capturing the viewer’s gaze with a sense of foreboding grace. Similarly, in Celtic-influenced imagery, swan women are often set against lush landscapes, their elongated forms blending into currents of water and wind. These variations reflect how the core narrative structure adapts to different aesthetic traditions while preserving the myth’s emotional and symbolic power.

Painters such as Odilon Redon (born 1840, died 1916) embraced the Swan Maiden’s dreamlike qualities, rendering her in soft pastels and muted palettes that emphasize mystery and transformation. Sculptors in the early 1900s, influenced by Symbolism and Art Nouveau, translated the fluid lines of feathered wings into flowing bronze and stone. These works often blur the boundary between human and bird, inviting viewers to contemplate identity, desire, and the tension between mortal and divine realms. In each interpretation, the central story of the Swan Maiden serves as both narrative and metaphor, enabling artists to explore timeless questions through evocative imagery.

The enduring popularity of the Swan Maiden across art traditions suggests that her story resonates beyond simple folklore, tapping into visual archetypes that speak to the human experience of longing and liberation. Viewers encounter not just a figure of myth but a complex symbol of transformation itself, raising questions about the nature of freedom and the price of captivity. By bringing this myth into the visual sphere, artists allow audiences to witness the moment of metamorphosis, to feel the tension between earthbound bonds and the yearning for the sky. In doing so, the Swan Maiden becomes more than a tale; she becomes a mirror of our own struggles for self-realization.

Feathers and Flesh – Artistic Depictions of Transformation

Throughout art history, the moment of transformation—the shift between swan and human—has been a favorite subject of visual artists who wish to convey motion and metamorphosis. This liminal state, rendered in texture and form, allows creators to explore how identity can be fluid and multifaceted, just as paint or stone itself can shift under the hand of the artist. In many depictions, the Swan Maiden’s feathers blend seamlessly into human skin, suggesting a unity of body and spirit that defies rigid classification. Such portrayals emphasize not only the physical change but also the emotional and psychological transition inherent in the myth.

Symbolism in Texture, Motion, and Form

Artists often give particular attention to the feathered cloak or robe, using it to symbolize the Swan Maiden’s shifting identity and nature. In works influenced by Art Nouveau around the turn of the 20th century, for example, feather motifs are exaggerated into sinuous lines that echo the currents of water and air. These decorative elements give the figure a sense of movement even in stillness, suggesting that transformation is ongoing rather than a single fixed moment. The tactile quality of feathers versus flesh becomes a visual metaphor for internal change.

Odilon Redon’s pastel works from the late 1800s stand as exemplary in their dreamlike rendering of the Swan Maiden, with soft edges and subdued colors that evoke dusk and mystery. His figures often seem suspended in a realm between waking and dreaming, enhancing the myth’s otherworldly qualities. Later, artists such as Dorothea Tanning (born 1910, died 2012) experimented with the theme by dissolving the boundary between body and form, hinting at transformation in ambiguous, shadowy compositions. These modern interpretations reflect broader artistic movements that embraced visual ambiguity and emotional complexity.

Through these varied stylistic approaches, the Swan Maiden’s metamorphosis remains fertile ground for artists seeking to visualize change itself. Her shifting form invites viewers to ponder their own transitions—between roles, identities, or life stages—in a visceral and aesthetic experience. By focusing on texture, motion, and form, artists create works that speak to both the eyes and the imagination, using myth as a bridge between ancient narrative and contemporary expression.

Stolen Cloaks – Visual Metaphors of Captivity and Control

One of the most dramatic moments in the Swan Maiden myth occurs when a man steals her feathered cloak, preventing her return to the supernatural realm. This act has been portrayed in art not only as a turning point in the story but also as a visual study in contrast—between concealment and exposure, freedom and limitation. Artists frequently choose this moment for its emotional and visual intensity, often framing the Swan Maiden with lowered gaze or outstretched hand, caught at the intersection of enchantment and earthly reality. These compositions reveal the complexities of the moment without editorializing, allowing viewers to interpret the scene through timeless symbolism.

Composition, Contrast, and Narrative Focus

The theft of the cloak offers painters and illustrators an opportunity to explore themes of possession, choice, and hidden knowledge without overt moralizing. In Romantic and Victorian works, the Swan Maiden is often shown unaware of the theft, adding tension to the scene. Classical compositions from the 1800s relied on rich color and dramatic contrast between light and shadow to highlight the moment of loss. These techniques focus on the aesthetic storytelling—drawing attention to mood, gesture, and emotional nuance.

In other works, the Swan Maiden appears aware but powerless, evoking a mood of quiet resignation. Rather than critique or idealize the figures, artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries often sought to capture the emotional truth of a mythic moment. By avoiding overt judgment, they preserved the story’s mystery and allowed the visual details to speak for themselves. The cloak, rendered in fine detail or luminous drapery, becomes a central visual element symbolizing both transformation and captivity.

These visual interpretations do not rely on ideological messages but instead elevate the narrative through composition and symbolic focus. By emphasizing beauty, mystery, and storytelling, artists preserve the myth’s enduring power. Each viewer brings their own understanding to the image, engaging with the ancient theme through the universal language of art.

The Maiden in Flight – Liberation on Canvas and Stage

Another powerful visual moment in the Swan Maiden myth occurs when she finally regains her feathered cloak and returns to the sky. This moment of flight is rich with symbolic meaning and artistic possibility, allowing painters, sculptors, and designers to depict elevation, release, and restored identity. Whether through the outspread wings of a sculpture or the upward lines of a painted figure, the Swan Maiden’s flight has remained a compelling subject for those seeking to capture transcendence. Artists have used this visual language to emphasize the beauty of movement and the emotional satisfaction of return.

The Return to the Sky: Escaping the Frame

In many visual representations, the Swan Maiden’s ascent symbolizes more than physical escape—it represents a return to her essential nature. Romantic painters of the 1800s often depicted her departure against dramatic skies, using light and atmosphere to enhance the sense of release. Sculptures and stage designs from the same period mirrored this upward motion in the curve of wings or fabric, reinforcing the idea of rising above the earthly condition. The story’s resolution becomes an opportunity to express grace, dignity, and serenity.

The ballet Swan Lake (composed by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky in 1875–1876) visually embodies this moment in its final acts. Though it diverges from the traditional myth, its choreography and staging reflect similar themes of transformation and return. The swan-themed costumes and ethereal movement emphasize fluidity and ascension, while the scenic design often depicts lakes, skies, and veils of mist to heighten the sense of departure. These theatrical elements enrich the visual vocabulary of the myth without departing from its emotional core.

By depicting the Swan Maiden in flight, artists affirm her enduring role as a symbol of beauty restored and selfhood regained. The image of her rising into the air—cloak reclaimed, gaze lifted—is one of triumph and return. Whether through oil painting, sculpture, or stagecraft, this moment continues to inspire artworks that celebrate the power of restoration and release.

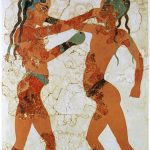

Cultural Variants – Visual Traditions Beyond the West

The Swan Maiden is not confined to Western myth or European art. Across the globe, similar tales have inspired distinct artistic traditions, each rich with local symbolism and aesthetic values. In Japan, for example, the Tennin—a celestial maiden who wears a feathered robe—has long appeared in painted scrolls, theater costumes, and masks. Russian folklore includes bird-maiden figures in illuminated manuscripts and folk paintings, while Indigenous traditions in North America depict winged women in ceremonial regalia and modern symbolic art.

Japanese, Slavic, and Indigenous Representations in Art

Japanese depictions of Tennin during the Edo period (1603–1868) show graceful, floating figures wearing their signature feathered robes known as hagoromo. These works often emphasize calm, spiritual beauty and are rendered with elegant brushwork, soft tones, and minimal composition. In Noh theater, the motif continues with stylized movements and symbolic robes, emphasizing the maiden’s otherworldliness. The visual language is restrained yet evocative, showing the Swan Maiden archetype as a bearer of peace and celestial harmony.

Slavic visual interpretations, especially in Russia, include images of the Firebird and bird-women in vibrant folklore art and ballet stage design. The Firebird, while more fiery than feathery, shares visual DNA with the Swan Maiden, especially in the grandeur of her plumage and her otherworldly origin. Folk illustrations and embroidered garments often depict feathered beings or bird-masked maidens, blending myth with daily cultural symbolism. These designs highlight how the myth has filtered into every level of visual culture, not just elite painting or sculpture.

In Indigenous North American traditions, stories of women who take the form of birds or return to the sky appear in ceremonial regalia and storytelling motifs. Modern Native artists have revisited these themes, painting or sculpting women with feathered cloaks or wings, often using natural materials and earth tones. These depictions emphasize the sacredness of flight and connection to nature, rather than conflict or loss. The Swan Maiden figure becomes a cultural bridge between human and spirit, not merely a narrative device.

These global perspectives enrich our understanding of how the Swan Maiden myth travels and transforms. Each culture adapts the visual form to its own spiritual and artistic values, yet the core elements—feathers, flight, and feminine grace—remain surprisingly constant. The result is a tapestry of art that speaks not just to mythology but to humanity’s deep longing for transcendence.

The Myth Reimagined – Contemporary Artists and Symbolic Views

In the 20th and 21st centuries, artists began revisiting the Swan Maiden myth through new visual languages, using the story not only for its aesthetics but also its symbolic potential. Rather than retelling the old tale, these creators have focused on universal ideas like personal transformation, identity, and the role of myth in modern life. Materials such as metal, glass, fabric, and even digital media have expanded the way this ancient figure is interpreted. The focus has shifted from folklore illustration to metaphysical meditation.

Reclaiming the Swan Maiden in Modern Visual Language

One artist who has repeatedly explored these themes is Kiki Smith (born 1954), whose works often center on the human body, myth, and the natural world. Her sculptures and prints evoke transformation through subtle, almost anatomical renderings of skin, feathers, and wings. In pieces like Born (2002) and Fountainhead (1991), she creates forms that suggest metamorphosis without declaring it outright, echoing the ambiguous moment of the Swan Maiden’s change. Smith’s interest in mythology allows her to channel old stories into contemporary visual codes.

Contemporary reinterpretations frequently favor abstraction and symbolism over direct narrative. A cloak might appear as a floating veil of translucent material, a body as fragmented or suspended in space. These visual choices emphasize mood and metaphor rather than storytelling, inviting viewers to project their own meanings onto the figure. Rather than reinforcing a linear tale, these artworks open the myth into a space of personal reflection and spiritual contemplation.

Such works avoid didacticism and instead focus on form, beauty, and complexity. In gallery spaces and public installations, the Swan Maiden becomes a symbol of artistic freedom—unbound by medium, culture, or dogma. Her presence lingers in the wings of a sculpture, the curve of a drawing, or the reflective surface of a textile, encouraging viewers to see transformation not as loss, but as elevation.

By bringing new materials and interpretive freedom to this ancient figure, today’s artists continue the Swan Maiden’s visual journey. They ensure her flight remains not only a tale from the past, but a living symbol for those seeking grace, identity, and renewal in the visual arts.

Conclusion

The Swan Maiden’s journey from legend to canvas reveals a myth that transcends centuries and cultures. Her image—whether soaring skyward, shedding her cloak, or caught between worlds—has offered artists a way to explore change, beauty, and the limits of human experience. From 19th-century masters like Odilon Redon to contemporary creators like Kiki Smith, artists have used this figure to evoke wonder, longing, and the search for meaning. Whether in Japanese scrolls, Russian ballet, or modern sculpture, the Swan Maiden continues to inspire awe and imagination.

Her power lies in what she represents: the mystery of transformation, the tension between freedom and constraint, and the deep human yearning for flight. These themes, rendered in pigment, stone, or movement, offer viewers more than a story—they provide a visual experience of the spiritual and emotional depth found in ancient myth. The Swan Maiden reminds us that art, like story, evolves without losing its core. Her image remains timeless.

As long as artists seek to portray change and grace, the Swan Maiden will remain in flight—an enduring symbol of transformation, rendered across the visual traditions of the world.

Key Takeaways

- The Swan Maiden myth has inspired art across cultures and time periods.

- Visual artists focus on transformation, flight, and symbolic contrast.

- Japanese, Slavic, and Native traditions interpret the myth uniquely.

- Modern artists like Kiki Smith revisit the theme with abstract language.

- The Swan Maiden remains a powerful visual symbol of change and beauty.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is the Swan Maiden myth and how is it used in art?

- Which cultures feature similar winged maiden figures in their traditions?

- How do artists depict the transformation between swan and woman?

- Are there modern artists who still reference the Swan Maiden?

- Why has the myth remained visually relevant for so long?