Romanticism was an artistic, literary, and intellectual movement that flourished from c. 1800 to 1850. It emerged as a reaction against the rationalism and order of Neoclassicism (c. 1750–1830) and the industrialization of Europe. Romantic artists sought to express intense emotions, the beauty of nature, and the power of the imagination. The movement celebrated individualism, the sublime, and the supernatural, making it one of the most expressive and dramatic art movements in history.

The roots of Romanticism can be traced back to the late 18th century, influenced by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), and Edmund Burke (1729–1797). The French Revolution (1789–1799) and the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) further shaped the movement, inspiring themes of freedom, heroism, and national identity. In art, Romanticism rejected the strict rules of Neoclassicism, instead emphasizing dynamic compositions, emotional intensity, and dramatic contrasts of light and color.

Romanticism was not confined to one country, but flourished across France, Germany, Britain, and Spain, before influencing America and Russia. Artists such as Francisco Goya (1746–1828), Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840), J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851), and Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) defined the movement with their expressive, symbolic, and sometimes politically charged works. Their art captured themes of nature’s grandeur, human struggle, folklore, and the supernatural, breaking away from the calm and structured compositions of the Enlightenment era.

This article explores the historical origins, defining characteristics, key artists, and major artworks of Romanticism. We will also examine how the movement influenced later artistic styles, including Realism (1840s–1890s) and Symbolism (1880s–1910). By the end, readers will understand why Romanticism remains one of the most influential and emotionally powerful movements in art history.

The Historical Context Behind Romanticism

Romanticism arose during a time of profound social and political change in Europe and America. The French Revolution (1789–1799) had overthrown the monarchy and introduced radical ideas of liberty, equality, and fraternity. The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) followed, spreading both nationalism and destruction across the continent. Romantic artists, deeply affected by these events, explored themes of heroism, revolution, and individual struggle.

Another major factor influencing Romanticism was the Industrial Revolution (c. 1760–1840), which transformed agriculture, industry, and urban life. While Neoclassicism celebrated progress and reason, Romantics reacted against mechanization and urbanization, longing for a return to nature, imagination, and emotion. Painters like John Constable (1776–1837) depicted idyllic rural landscapes, mourning the loss of traditional ways of life.

Philosophy and literature also played a crucial role in shaping Romantic ideals. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in works like Emile (1762), championed the idea that emotion and nature should guide human experience. Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757) defined the sublime as something that evokes awe, terror, and grandeur, a concept that became central to Romantic art. Writers like Goethe, Lord Byron (1788–1824), and Mary Shelley (1797–1851) infused their works with themes of gothic horror, the supernatural, and the rebellious hero.

By the early 19th century, Romanticism had spread across Europe and America, influencing painting, literature, music, and architecture. It thrived in France, Germany, Britain, and Spain, each region developing its own distinct interpretation. However, despite regional variations, Romantic artists were united by a shared rejection of classical order and a deep desire to express the human soul in its rawest form.

Key Themes and Characteristics of Romantic Art

Romantic artists rejected the rationalism and order of Neoclassical art, embracing emotion, imagination, and the unpredictable forces of nature. Their paintings often depicted dramatic landscapes, supernatural scenes, historical conflicts, and heroic struggles. These works emphasized the sublime, where nature was presented as both awe-inspiring and terrifying.

One of the most striking features of Romantic art was the focus on emotion and individual experience. Instead of idealized, composed figures, Romantic paintings portrayed intense facial expressions, powerful body language, and raw human suffering. Francisco Goya’s The Third of May 1808 (1814), for example, captures the brutal execution of Spanish rebels by Napoleon’s forces, emphasizing fear, agony, and injustice. This kind of emotional storytelling became central to Romantic painting.

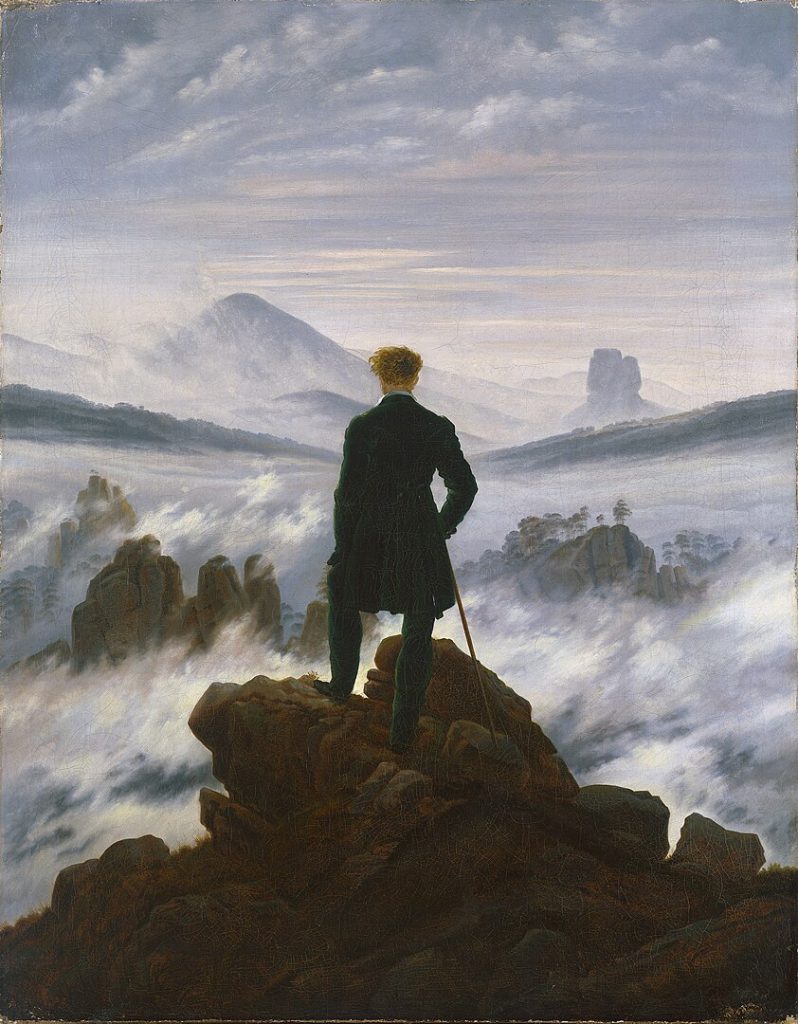

Nature was another dominant theme in Romanticism, often portrayed as a force greater than humanity. Unlike the balanced, harmonious landscapes of Neoclassicism, Romantic artists painted storms, raging seas, towering mountains, and dark forests. Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818) depicts a solitary figure gazing over a misty, treacherous landscape, symbolizing human isolation and the vast power of nature.

Romanticism also explored the mystical, supernatural, and irrational. Painters often depicted ghosts, gothic ruins, and eerie dreamlike scenes, inspired by folklore, mythology, and medieval legends. Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare (1781), with its dark, haunting imagery of a demonic incubus sitting on a sleeping woman’s chest, exemplifies this fascination with the unconscious and the surreal.

The Great Masters of Romanticism

Several artists defined Romanticism, each bringing their unique perspective and techniques to the movement. These artists broke away from classical traditions, embracing personal expression, movement, and dramatic contrasts.

Francisco Goya (1746–1828) – The Spanish Visionary

- One of the most influential Romantic painters, known for his dark, politically charged works.

- Created haunting depictions of war, oppression, and the supernatural.

- Major works: The Third of May 1808 (1814) – a brutal anti-war statement, and Saturn Devouring His Son (c. 1819–1823) – a nightmarish image of destruction and fear.

Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840) – The Poet of Nature

- German painter known for mystical, atmospheric landscapes that reflect human solitude and divine presence.

- Explored themes of the sublime, spirituality, and the insignificance of man in nature.

- Major works: Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818) – a powerful image of isolation and contemplation, and The Abbey in the Oakwood (1809–1810) – a gothic, haunting vision of decay and eternity.

J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851) – The Master of Light and Motion

- British painter known for dramatic seascapes and stormy skies, capturing the raw power of nature.

- Used bold, expressive brushwork that prefigured Impressionism (1860s–1890s).

- Major works: The Fighting Temeraire (1839) – a melancholic tribute to Britain’s naval past, and Rain, Steam, and Speed (1844) – an exploration of modern progress and industrialization.

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) – The Revolutionary Romantic

- French painter who brought energy, color, and drama to Romantic art.

- His works reflected passion, revolution, and heroic struggle.

- Major works: Liberty Leading the People (1830) – a celebration of the French Revolution, and The Death of Sardanapalus (1827) – a sensual, chaotic scene of destruction and excess.

Romanticism in Sculpture and Architecture

While Romanticism is primarily associated with painting and literature, it also influenced sculpture and architecture in significant ways. Unlike the idealized, balanced forms of Neoclassicism, Romantic sculpture emphasized movement, intense emotion, and dynamic compositions. Artists sought to capture heroic struggle, raw passion, and mythological drama, often depicting historical events or supernatural themes.

One of the most famous Romantic sculptors was François Rude (1784–1855), who created the highly expressive relief sculpture La Marseillaise (1833–1836) on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. This monumental work depicts French revolutionaries charging forward with fierce determination, symbolizing nationalistic fervor and the fight for freedom. The figures are dramatically posed, with exaggerated facial expressions and flowing garments, reflecting Romanticism’s emphasis on emotional intensity and movement.

Another major Romantic sculptor was Antoine-Louis Barye (1795–1875), who specialized in dynamic, lifelike animal sculptures. His works, such as Tiger Devouring a Gavial (1831), captured the raw energy and violence of nature, aligning with the Romantic fascination with the sublime and the untamed wilderness. Barye’s attention to anatomical accuracy and dramatic composition set him apart from earlier classical sculptors.

In architecture, Romanticism inspired a revival of Gothic, medieval, and exotic styles, rejecting the strict symmetry and rationality of Neoclassicism. The Gothic Revival (c. 1830–1900) became one of the most important architectural movements of the 19th century, with designers embracing pointed arches, spires, stained glass, and intricate ornamentation. One of the most famous examples is the Palace of Westminster (1840–1876) in London, designed by Charles Barry (1795–1860) and Augustus Pugin (1812–1852).

Beyond Gothic Revival, Romantic architecture also drew inspiration from Eastern and exotic cultures. The Royal Pavilion (1815–1823) in Brighton, England, designed by John Nash (1752–1835), features Indian and Chinese architectural influences, reflecting Europe’s fascination with the mystical and the foreign. This blending of styles showcased Romanticism’s rejection of rigid rules and embrace of imagination and fantasy.

The Role of Nationalism and Folklore in Romanticism

Romanticism was deeply connected to nationalism, inspiring artists and writers to explore their cultural heritage, folklore, and historical struggles. As European nations sought to define their identities in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), Romanticism became a means of celebrating national heroes, legends, and folk traditions.

In Germany, artists like Caspar David Friedrich painted landscapes infused with spirituality and patriotism, while writers such as the Brothers Grimm (Jacob Grimm, 1785–1863, and Wilhelm Grimm, 1786–1859) collected traditional folktales like Hansel and Gretel and Snow White to preserve German cultural identity. Their work influenced Romantic literature across Europe, inspiring a renewed interest in mythology and medieval legends.

In France, Eugène Delacroix captured the spirit of revolution and national pride in works such as Liberty Leading the People (1830), which depicted the July Revolution of 1830 in a highly dramatic and emotionally charged manner. French Romantic composers like Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) infused their music with nationalistic themes, as seen in his Symphonie Fantastique (1830), which tells the story of an artist’s intense emotions and visions.

In Spain, Francisco Goya painted the horrors of war and oppression, particularly in works like The Third of May 1808 (1814), which depicted the brutal execution of Spanish rebels by French forces. His later works, including the haunting *Black Paintings (c. 1819–1823), explored superstition, fear, and psychological turmoil, reflecting the darker side of Romanticism.

Romanticism also influenced the United States, where artists of the Hudson River School (c. 1825–1875), such as Thomas Cole (1801–1848) and Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), painted vast, dramatic landscapes that celebrated American wilderness and national identity. Their works, such as Cole’s The Oxbow (1836) and Church’s *Heart of the Andes (1859), reflected the Romantic belief in the power and beauty of untouched nature.

The Decline of Romanticism and the Rise of Realism

By the mid-19th century, Romanticism began to decline as social, political, and technological changes led to a shift in artistic priorities. The Industrial Revolution (c. 1760–1840) continued to transform society, bringing urbanization, mass production, and scientific advancements that clashed with Romantic ideals of emotion, nature, and mysticism.

The Revolutions of 1848, which swept across France, Germany, Italy, and Austria, led to political instability and growing disillusionment with Romantic notions of heroic struggle and national glory. Artists and writers turned to Realism (c. 1840s–1890s), a movement that rejected Romantic escapism in favor of depicting everyday life and social realities.

One of the first artists to break away from Romanticism was Gustave Courbet (1819–1877), who famously declared, “Show me an angel and I’ll paint one.” His works, such as The Stone Breakers (1849), depicted ordinary laborers in an unidealized, gritty manner, signaling a rejection of Romantic fantasy.

Similarly, Jean-François Millet (1814–1875) painted scenes of rural peasants, while Honoré Daumier (1808–1879) used his art to criticize social injustice and political corruption. This transition from Romantic idealism to Realist objectivity marked a major turning point in art history.

Despite its decline, Romanticism continued to influence later artistic movements, including Symbolism (1880s–1910) and Expressionism (1905–1930s). Its themes of emotion, imagination, and individualism also shaped modern cinema, literature, and music, proving its enduring impact on Western culture.

The Lasting Legacy of Romanticism

Although Romanticism declined as a dominant movement by the mid-19th century, its influence remains profound and widespread. It reshaped how artists, writers, and musicians approached emotion, nature, and personal expression. Romantic ideals inspired later movements such as:

- Symbolism (1880s–1910) – Artists like Gustav Klimt (1862–1918) and Odilon Redon (1840–1916) continued exploring dreamlike, mystical themes.

- Expressionism (1905–1930s) – Painters such as Edvard Munch (1863–1944) drew on Romantic emotion and psychological intensity.

- Modern Film and Literature – Romantic themes of heroism, the supernatural, and nature’s power continue to shape movies, novels, and poetry today.

Museums such as the Louvre, the Prado Museum, the Tate Britain, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art house iconic Romantic paintings, ensuring the movement’s enduring legacy. Romanticism’s emphasis on passion, the sublime, and the unknown still resonates with artists, writers, and audiences worldwide.

Key Takeaways

- Romanticism (c. 1800–1850) emphasized emotion, nature, and individualism, rejecting Neoclassical rationalism.

- It flourished in France, Germany, Britain, Spain, and America, shaping painting, sculpture, literature, and music.

- Key artists: Francisco Goya, Caspar David Friedrich, J.M.W. Turner, Eugène Delacroix.

- Romanticism inspired later movements such as Realism, Symbolism, and Expressionism.

- Its influence continues to be seen in modern art, cinema, and literature.