Polish art is a reflection of a nation with a resilient spirit, a deep connection to its cultural heritage, and a long history of adapting to challenges. From medieval Gothic cathedrals to the avant-garde movements of the 20th century, Polish artists have consistently found ways to blend local traditions with broader European currents. Despite centuries of political upheaval, partitions, and war, Poland’s artistic legacy endures as a testament to its cultural strength and creative innovation.

A Nation of Crossroads

Situated at the crossroads of Central and Eastern Europe, Poland has been influenced by a variety of cultural traditions, including:

- Western Europe: The Renaissance and Baroque periods brought Italian and French influences, visible in Polish architecture and painting.

- Eastern Orthodoxy and Byzantine Art: Polish religious art reflects elements of Eastern iconography, particularly in regions near modern-day Ukraine.

- Local Folk Traditions: Polish art maintains a strong connection to folk motifs, seen in textiles, woodcarvings, and patterns inspired by rural life.

Recurring Themes in Polish Art

Polish art has consistently engaged with themes that reflect its history and identity:

- National Pride and Resistance: Many Polish artworks serve as acts of defiance and expressions of national pride, particularly during periods of foreign rule.

- Religious Devotion: The Catholic Church has played a significant role in shaping Polish art, from medieval altarpieces to Baroque grandeur.

- Innovation and Experimentation: Polish artists have often been at the forefront of European avant-garde movements, contributing to global art history.

A Journey Through Time

This exploration of Polish art will cover over a thousand years of creativity, highlighting:

- The Romanesque churches and Gothic cathedrals of medieval Poland.

- The grandeur of the Polish Renaissance and Baroque.

- The Romantic movement’s role in preserving national identity during times of partition.

- The 20th century’s avant-garde innovations and challenges under Socialist Realism.

- The vibrant, global-facing art scene of contemporary Poland.

Poland’s art is a story of resilience and renewal, showcasing the power of creativity to sustain a nation through its darkest and brightest moments.

Chapter 1: Medieval Art in Poland (1000–1500)

The medieval period marked the beginning of Poland’s artistic tradition, as Christianity became the dominant cultural and religious force in the region. This era saw the construction of monumental Romanesque and Gothic churches, the production of illuminated manuscripts, and the emergence of distinct Polish styles in sculpture and religious art.

Romanesque Art and Architecture (1000–1250)

Romanesque art in Poland reflected the influence of Western Europe while incorporating local traditions.

- Key Features:

- Thick stone walls, rounded arches, and small windows typify Romanesque church design.

- Religious reliefs and sculptures adorned churches, often depicting biblical stories and saints.

- Notable Examples:

- Gniezno Cathedral:

- One of Poland’s oldest cathedrals, originally built in the Romanesque style, served as the coronation site for early Polish kings.

- St. Andrew’s Church, Kraków:

- A well-preserved example of Romanesque architecture, this fortress-like church reflects the practical need for defense in medieval Poland.

- Gniezno Cathedral:

The Gothic Revolution (1250–1500)

The Gothic style brought dramatic changes to Polish art and architecture, emphasizing height, light, and intricate detail.

- Cathedrals and Churches:

- Wawel Cathedral, Kraków:

- A masterpiece of Gothic architecture, the cathedral became the coronation site for Polish monarchs.

- Its chapels and tombs are adorned with intricate stonework and stained glass.

- St. Mary’s Basilica, Kraków:

- Famous for its towering spires and stunning interior, including the Veit Stoss Altarpiece, an extraordinary Gothic woodcarving.

- Wawel Cathedral, Kraków:

- Illuminated Manuscripts:

- The production of illuminated manuscripts flourished in medieval Poland, often commissioned by the Church or the nobility.

- The Codex Aureus Gnesnensis (Golden Codex of Gniezno) is a stunning example, featuring richly decorated miniatures.

Religious Sculpture and Art

Sculpture played a vital role in medieval Polish art, often adorning churches and chapels with religious imagery.

- Veit Stoss (Wit Stwosz):

- A German-born sculptor who worked extensively in Kraków, Veit Stoss created the monumental Altarpiece of St. Mary’s Basilica (1477–1489), one of the largest and most intricate Gothic altarpieces in Europe.

- Wooden Madonnas:

- Wooden sculptures of the Virgin Mary, often painted and gilded, were popular devotional objects.

Castles and Secular Architecture

While religious art dominated the medieval period, Poland also saw the construction of castles and civic buildings that reflected its growing power and wealth.

- Malbork Castle:

- Built by the Teutonic Knights, Malbork Castle is the largest brick fortress in the world and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Its blend of Gothic architecture and military functionality reflects Poland’s strategic importance during the Middle Ages.

Themes of Medieval Polish Art

Medieval Polish art was deeply connected to the Church and the nation’s growing identity:

- Religious Devotion: Art served as a tool for worship and education, communicating biblical stories to a largely illiterate population.

- Cultural Crossroads: Situated between East and West, Polish medieval art reflects influences from both Western Europe and Byzantine traditions.

- Monumentality and Permanence: The construction of grand cathedrals and castles symbolized the strength and stability of the Polish state.

The Transition to the Renaissance

By the late 15th century, Poland was on the cusp of a cultural transformation. The introduction of Renaissance ideas would bring new styles and techniques, ushering in a golden age of Polish art.

Chapter 2: The Polish Renaissance (1500–1600)

The Renaissance in Poland was a period of flourishing cultural and artistic achievement, deeply influenced by Italian humanism while retaining a distinctly Polish identity. The spread of Renaissance ideas across Europe coincided with Poland’s Golden Age, a time of political stability, economic prosperity, and intellectual growth under the Jagiellonian dynasty. During this era, Polish art, architecture, and literature reached new heights, blending classical ideals with local traditions.

Renaissance Architecture: The Italian Influence

Italian architects played a significant role in introducing Renaissance styles to Poland, leading to the creation of grand palaces, churches, and civic buildings.

- Wawel Castle, Kraków:

- Rebuilt in the Renaissance style during the reign of King Sigismund I the Old, Wawel Castle became a symbol of royal power and sophistication.

- The Arcaded Courtyard is a masterpiece of Renaissance design, featuring elegant columns and symmetrical proportions.

- Zamość: The Ideal Renaissance City:

- Designed by Italian architect Bernardo Morando, Zamość is a prime example of Renaissance urban planning.

- Its harmonious layout, with a central market square and arcaded townhouses, reflects the humanist ideals of order and symmetry.

Painting and Sculpture: A Fusion of Styles

Polish Renaissance art combined Italian techniques with Gothic traditions, producing works that reflected both local and European influences.

- Stanisław Samostrzelnik (c. 1480–1541):

- A monk and artist, Samostrzelnik is known for his illuminated manuscripts, which blend Gothic intricacy with Renaissance realism.

- His works, such as the Missal of Piotr Tomicki, showcase vibrant colors and detailed figures.

- Jan Michałowicz of Urzędów (c. 1530–1584):

- A sculptor and architect, Michałowicz created intricate tomb monuments, such as the Tomb of King Sigismund I, which combine Gothic and Renaissance elements.

- The Kraków School:

- A group of artists centered in Kraków produced religious and secular paintings that incorporated Renaissance techniques, such as perspective and naturalism.

Patronage and Cultural Flourishing

The Polish nobility, particularly the magnates, played a crucial role in fostering the Renaissance in Poland by commissioning art, architecture, and literature.

- King Sigismund I the Old and Queen Bona Sforza:

- This royal couple invited Italian artists, architects, and scholars to Poland, transforming Kraków into a Renaissance cultural hub.

- The Nobility and Sarmatism:

- While adopting Renaissance styles, Polish art retained elements of local identity, reflecting the ideals of Sarmatism, which celebrated the nobility’s unique role in Polish society.

Literature and Humanism

The Renaissance in Poland extended beyond the visual arts to literature, philosophy, and science.

- Mikołaj Kopernik (Nicolaus Copernicus):

- Though primarily known as a scientist, Copernicus was a product of the Renaissance’s intellectual climate, embodying the era’s emphasis on reason and observation.

- Jan Kochanowski (1530–1584):

- Often regarded as the father of Polish poetry, Kochanowski wrote in Polish and Latin, blending classical themes with local traditions.

- His collection Treny (Laments) is a masterpiece of Renaissance humanism, reflecting personal grief and universal themes.

Themes of the Polish Renaissance

The Renaissance in Poland reflected the era’s intellectual and artistic ideals while maintaining a distinct Polish character:

- Harmony and Balance: Renaissance art and architecture emphasized proportion, symmetry, and order, inspired by classical antiquity.

- Humanism and Individualism: Art and literature celebrated the human experience, focusing on personal achievement and intellectual growth.

- Cultural Identity: While influenced by Italy and Western Europe, Polish Renaissance art incorporated local motifs and traditions, creating a unique blend of styles.

Transition to the Baroque

By the late 16th century, the Renaissance in Poland began to give way to the dramatic and emotional style of the Baroque. This transition reflected the growing influence of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, which would dominate Polish art and culture in the coming century.

Chapter 3: The Baroque Era in Poland (1600–1750)

The Baroque era in Poland was a time of grandeur, drama, and religious fervor, deeply influenced by the Catholic Counter-Reformation. During this period, art and architecture were used to inspire awe, express power, and reinforce Catholic values in response to the Protestant Reformation. Lavish churches, ornate palaces, and dynamic portraiture flourished, blending European Baroque styles with uniquely Polish elements, particularly in the noble Sarmatism aesthetic.

The Catholic Counter-Reformation and Religious Art

The Baroque era was shaped by the Catholic Church’s efforts to reassert its dominance through art that evoked emotion and devotion.

- Key Features:

- Dramatic use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro).

- Theatrical compositions designed to engage the viewer emotionally.

- Elaborate decoration emphasizing divine glory.

- Notable Churches:

- Church of St. Anne, Kraków:

- This Jesuit church epitomizes Polish Baroque, with its grandiose facade and richly decorated interior.

- Holy Trinity Church, Kraków:

- Known for its dynamic Baroque altars and ceiling frescoes.

- Church of St. Anne, Kraków:

Baroque Architecture: Magnificence and Splendor

Baroque architecture in Poland reflected the wealth and power of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, combining Italian influences with local traditions.

- Wilanów Palace, Warsaw:

- Built for King Jan III Sobieski, this royal residence exemplifies Polish Baroque with its symmetrical design and richly ornamented interiors.

- The palace’s gardens integrate Baroque geometry with Polish landscape aesthetics.

- Krasiczyn Castle:

- A fusion of Renaissance and Baroque styles, this castle is adorned with intricate sgraffito decorations depicting allegories and historical scenes.

Sarmatian Portraiture and Nobility

The Polish nobility, or szlachta, embraced the Baroque style to assert their cultural identity and social status. This unique aesthetic, known as Sarmatism, blended grandeur with symbolic representation.

- Sarmatian Portraiture:

- Portraits of nobles often featured elaborate costumes, armor, and accessories, symbolizing wealth, honor, and patriotism.

- Artists such as Daniel Schultz painted lifelike and imposing portraits of magnates like King Jan III Sobieski.

- Themes of Sarmatism:

- Sarmatism celebrated the supposed descent of Polish nobles from ancient Sarmatian warriors, emphasizing values like bravery, loyalty, and religious devotion.

Baroque Sculpture and Decorative Arts

Baroque sculpture in Poland was closely tied to religious and architectural settings, featuring dynamic forms and intricate details.

- Religious Sculpture:

- Altarpieces and pulpit decorations were often crafted from wood, painted, and gilded to dramatic effect.

- Decorative Arts:

- Luxurious furnishings, textiles, and silverware reflected the opulence of the era.

- Amber became a prized material for jewelry and decorative objects, with Polish artisans crafting intricate amber altarpieces and reliquaries.

Baroque Painting

While Poland did not produce as many renowned Baroque painters as Italy or Spain, its artists contributed significantly to religious and secular art.

- Religious Compositions:

- Frescoes and altarpieces adorned churches across Poland, often depicting biblical scenes with dramatic lighting and emotional intensity.

- Historical Paintings:

- Scenes of military victories and national pride were popular, such as those commemorating King Jan III Sobieski’s victory at the Battle of Vienna (1683).

Themes of the Baroque in Poland

The Baroque era in Poland reflected both European trends and uniquely Polish elements:

- Religious Devotion: The Counter-Reformation inspired a wave of deeply emotional and theatrical religious art.

- Noble Identity: The Sarmatian aesthetic emphasized the distinctiveness and power of the Polish nobility.

- Grandeur and Ornamentation: Art and architecture during this period were designed to dazzle, inspire, and elevate.

Transition to the Rococo and Enlightenment

By the mid-18th century, the dramatic intensity of the Baroque gave way to the lighter, more decorative style of the Rococo. This transition marked a shift toward elegance and refinement, setting the stage for the Enlightenment’s influence on Polish art.

Chapter 4: The Age of Enlightenment and Rococo (1750–1800)

The Age of Enlightenment in Poland marked a shift from the dramatic grandeur of the Baroque to the refined elegance of the Rococo. This period reflected a growing emphasis on reason, scientific inquiry, and secularism, which influenced Polish art, architecture, and culture. While religious art remained important, the Enlightenment encouraged a rise in secular themes, including portraiture, decorative arts, and palace design.

Rococo Architecture: Elegance and Ornamentation

Rococo architecture in Poland emphasized lightness, grace, and intricate detail, often seen in the decoration of palaces and churches.

- Łazienki Palace (Palace on the Isle), Warsaw:

- Originally a bathhouse, this Rococo palace was transformed by King Stanisław August Poniatowski into a summer residence.

- Its interiors feature delicate stucco work, gilded accents, and pastel hues characteristic of the Rococo style.

- Branicki Palace, Białystok:

- Known as the “Polish Versailles,” this grand residence exemplifies Rococo elegance with its symmetrical design, ornamental gardens, and richly decorated interiors.

The Rise of Secular Art and Portraiture

The Enlightenment’s focus on humanism and individualism led to a flourishing of portraiture and secular themes in Polish art.

- Stanisław August Poniatowski’s Portrait Collection:

- The last King of Poland, Stanisław August Poniatowski, was a major patron of the arts, commissioning portraits that celebrated Enlightenment ideals.

- Artists such as Marcello Bacciarelli and Bernardo Bellotto created lifelike depictions of the king, nobility, and intellectuals.

- Sarmatian Portraits in Transition:

- While Sarmatian portraiture continued, it became less grandiose, reflecting the Rococo’s emphasis on elegance and intimacy.

Decorative Arts: Rococo’s Influence

The decorative arts flourished during this period, with Polish artisans producing luxurious objects that blended Rococo aesthetics with local traditions.

- Furniture and Interiors:

- Polish craftsmen created ornate furniture with curved lines, gilded carvings, and intricate inlays.

- Decorative ceilings and walls were adorned with stucco reliefs and pastel-colored frescoes.

- Textiles and Ceramics:

- Tapestries and embroidered textiles featured floral motifs, reflecting the Rococo’s light and playful character.

- The Porcelain Factory in Korzec produced elegant porcelain wares inspired by French and German styles.

Scientific and Educational Themes in Art

The Enlightenment’s emphasis on education and science influenced Polish art and culture during this period.

- Commissioning of Scientific Illustrations:

- Botanical and zoological illustrations became popular, often commissioned for scientific studies and encyclopedias.

- Theater and Literature:

- Artists contributed to set design and book illustration, fostering collaboration between visual and literary arts.

Architectural and Urban Planning Innovations

The Enlightenment also inspired advancements in urban planning and public architecture.

- Kraków’s Market Square Revitalization:

- Efforts to modernize Polish cities included the beautification of public spaces and construction of elegant townhouses with Rococo facades.

- Educational Institutions:

- Buildings for universities and schools were designed to reflect Enlightenment ideals of clarity and order, such as the expansion of the Collegium Nobilium in Warsaw.

Themes of the Enlightenment and Rococo in Poland

The art and architecture of this period reflected broader European trends while incorporating Polish cultural identity:

- Elegance and Intimacy: Rococo art celebrated beauty, lightness, and personal expression, moving away from the dramatic intensity of the Baroque.

- Reason and Progress: The Enlightenment’s focus on education and science influenced both public and private art commissions.

- Noble Patronage: The Polish nobility remained key supporters of the arts, fostering a uniquely Polish interpretation of Rococo style.

The Transition to Romanticism

By the late 18th century, Poland faced significant political challenges, culminating in the partitions of the country by neighboring empires. As a result, Polish art began to reflect themes of resistance, patriotism, and national identity, setting the stage for the Romantic movement of the 19th century.

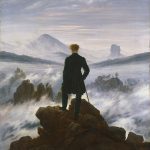

Chapter 5: The Romantic Movement and National Identity (1800–1850)

The Romantic movement in Poland was deeply intertwined with the nation’s struggle for independence and the preservation of its cultural identity during the partitions. With Poland divided among Russia, Prussia, and Austria, artists turned to Romantic ideals of heroism, nationalism, and emotional expression to inspire hope and resilience. This period produced some of the most iconic works in Polish art and literature, emphasizing themes of resistance, history, and the beauty of the Polish landscape.

Romanticism as a Tool for National Identity

Romanticism in Poland was not just an artistic movement but a form of cultural resistance against foreign rule. Art became a medium to preserve and celebrate Poland’s heritage, mythology, and ideals.

- Key Themes:

- National pride and the fight for independence.

- Nostalgia for Poland’s past glory, particularly the medieval era.

- Emotional connection to the Polish landscape.

Jan Matejko: The Painter of Polish History

Jan Matejko (1838–1893), although active slightly after the Romantic period, embodies the movement’s ideals in his monumental historical paintings.

- Battle of Grunwald (1878):

- This dramatic depiction of a medieval Polish victory over the Teutonic Knights celebrates Polish strength and heroism.

- Though painted later, Matejko’s work reflects Romantic themes of national pride and dramatic storytelling.

Historical and Mythological Painting

Romantic painters often drew inspiration from Polish folklore, legends, and history, creating works that connected contemporary struggles to Poland’s heroic past.

- Piotr Michałowski (1800–1855):

- Known for his equestrian portraits, Michałowski’s Napoleon on Horseback reflects the Romantic fascination with historical figures and their symbolic power.

- Artur Grottger (1837–1867):

- Grottger’s series of drawings, such as Polonia and Lithuania, depict the struggles of Polish patriots during uprisings against foreign powers, emphasizing themes of sacrifice and resilience.

The Polish Landscape as a Symbol of Identity

Romantic painters often used the Polish countryside to evoke a sense of national pride and spiritual connection to the land.

- Józef Chełmoński (1849–1914):

- Although primarily a Realist, Chełmoński’s early works reflect Romantic influences, portraying the Polish landscape with emotion and grandeur.

- Works like The Storks (1870) highlight the beauty and symbolism of rural Poland.

Romanticism in Polish Literature and Music

While the visual arts played a crucial role in Polish Romanticism, literature and music were equally important in preserving and celebrating Polish identity.

- Adam Mickiewicz (1798–1855):

- Mickiewicz, Poland’s national poet, was a key figure in Romantic literature. His epic poem Pan Tadeusz captures the spirit of Polish life, history, and ideals.

- Fryderyk Chopin (1810–1849):

- Chopin’s piano compositions, such as his Polonaises and Mazurkas, blend Romantic emotion with Polish folk traditions, becoming symbols of national pride.

Themes of Polish Romantic Art

Romantic art in Poland was characterized by its deep emotional resonance and patriotic focus:

- Nationalism and Patriotism: Art celebrated Poland’s history, heroes, and cultural identity, often as a form of defiance against foreign rule.

- Nature and the Sublime: The Polish landscape was depicted as a source of strength and inspiration, symbolizing the enduring spirit of the nation.

- Historical Mythology: Artists drew on Polish legends and historical events to connect the present to the past.

The Transition to Realism

As the 19th century progressed, Romantic ideals began to give way to Realism, reflecting changing social and political conditions. However, the themes of national pride and resistance established during the Romantic period continued to influence Polish art for decades to come.

Chapter 6: Realism and the Young Poland Movement (1850–1900)

The second half of the 19th century marked a transition in Polish art from the dramatic and emotional themes of Romanticism to the grounded depictions of Realism. As Poland remained under partition, artists began to focus on the everyday lives of the Polish people, rural traditions, and social struggles. Toward the end of the century, the Young Poland Movement emerged, blending Symbolism, Art Nouveau, and Impressionism into a vibrant cultural renaissance.

Realism: Art for the People

Realism in Poland developed as a response to the Romantic focus on myth and heroism, instead highlighting the daily lives and challenges of ordinary people.

- Key Features of Realism:

- A focus on rural life and working-class struggles.

- Detailed and honest depictions of people and landscapes.

- A sense of empathy and social awareness.

- Józef Chełmoński (1849–1914):

- One of Poland’s greatest Realist painters, Chełmoński captured the beauty and hardships of rural life.

- Works like Bociany (The Storks) (1900) and Babie Lato (Indian Summer) (1875) evoke the rhythms of nature and human connection to the land.

- Aleksander Gierymski (1850–1901):

- Gierymski’s paintings, such as The Peasant Woman with a Cow and Jewish Woman Selling Oranges, depict the lives of marginalized communities with empathy and dignity.

The Rise of the Young Poland Movement (1890–1914)

As the century drew to a close, the Young Poland Movement emerged as a reaction against the strict realism of earlier decades. Inspired by Symbolism, Art Nouveau, and Impressionism, this movement sought to explore spirituality, emotion, and the inner world.

- Key Figures of the Young Poland Movement:

- Jacek Malczewski (1854–1929):

- Malczewski is considered one of the greatest Polish Symbolists. His works, such as Melancholia (1894), blend mythological and allegorical themes with personal introspection.

- Stanisław Wyspiański (1869–1907):

- A painter, playwright, and designer, Wyspiański created stunning stained glass windows and pastels that reflect Art Nouveau’s emphasis on line and color.

- His work Chochoły (The Mounds) (1898) exemplifies the fusion of Polish folklore and modern aesthetics.

- Józef Mehoffer (1869–1946):

- Known for his decorative art and stained glass, Mehoffer’s The Strange Garden (1903) is a masterpiece of Young Poland’s dreamlike, symbolic style.

- Jacek Malczewski (1854–1929):

Architecture and Decorative Arts

The Young Poland Movement extended beyond painting to architecture, furniture, and textiles, creating a comprehensive cultural aesthetic.

- Art Nouveau in Kraków:

- Kraków became a hub of the movement, with buildings and interiors designed in the flowing, organic forms of Art Nouveau.

- Artists like Wyspiański and Mehoffer contributed stained glass and murals to public and private spaces.

- Zakopane Style:

- The architect and designer Stanisław Witkiewicz developed the Zakopane Style, a unique blend of Art Nouveau and traditional highland (Górale) architecture.

- This style celebrated Polish folk culture, featuring wooden structures with intricate carvings and motifs inspired by local traditions.

Themes of Realism and Young Poland

The art of this period reflected a complex interplay of grounded observation and imaginative exploration:

- Social Awareness: Realist works highlighted the struggles of peasants, workers, and marginalized communities, fostering empathy and solidarity.

- Cultural Renewal: The Young Poland Movement sought to revive and celebrate Polish identity through folklore, mythology, and contemporary aesthetics.

- Nature and Spirituality: Both Realism and Young Poland emphasized a deep connection to the Polish landscape, whether through literal depictions or symbolic interpretations.

The Transition to Modernism

As the 20th century approached, Polish art began to embrace more experimental forms, including abstraction and Cubism. The foundations laid by the Realist and Young Poland movements would influence the avant-garde and modernist developments of the early 20th century.

Chapter 7: Modernism and Avant-Garde Movements (1900–1945)

The early 20th century was a transformative period for Polish art, as artists engaged with modernist movements sweeping across Europe. From Cubism and Constructivism to the avant-garde experimentation of the interwar period, Polish artists pushed boundaries and contributed significantly to international art. Despite political challenges and the looming specter of World War II, this era saw a flourishing of creativity that laid the groundwork for contemporary Polish art.

The Influence of European Modernism

Polish artists were deeply influenced by modernist movements in Paris, Vienna, and Berlin, incorporating these ideas into their work while maintaining a distinct Polish identity.

- Cubism:

- Artists like Tytus Czyżewski (1880–1945) explored Cubist principles, blending fragmented forms with traditional Polish themes.

- His works, such as The Musician (1922), demonstrate a dynamic synthesis of Cubism and Expressionism.

- Expressionism and Symbolism:

- Polish Expressionists, including Leon Chwistek (1884–1944), used bold colors and distorted forms to explore themes of emotion and spirituality.

- Symbolism persisted in the works of Władysław Podkowiński, whose Frenzy of Exultations (1894) bridges the gap between Symbolism and early modernism.

The Avant-Garde in Interwar Poland

The interwar period was a golden age for Polish avant-garde movements, particularly in painting, sculpture, and graphic design.

Polish Constructivism

Polish artists embraced Constructivism, emphasizing geometry, abstraction, and functionality.

- Władysław Strzemiński (1893–1952):

- A leading figure in Polish Constructivism, Strzemiński developed the theory of Unism, which sought harmony in composition by eliminating contrasts.

- His works, such as Architectural Compositions (1929), exemplify a minimalist approach to abstraction.

- Katarzyna Kobro (1898–1951):

- A pioneering sculptor, Kobro’s abstract works emphasized spatial relationships and integration with their surroundings.

The Formists

The Formists were a Polish avant-garde group active in the 1920s, blending Cubism, Futurism, and Expressionism with Polish folk traditions.

- Key Figures:

- Tytus Czyżewski and Zbigniew Pronaszko were central to the Formist movement, producing works that combined geometric abstraction with a playful, experimental spirit.

- Andrzej Pronaszko (1888–1961): Known for his avant-garde theatrical designs, Andrzej extended the Formist aesthetic into stage and set design.

Graphic Design and Poster Art

The interwar period saw Polish artists excelling in graphic design, particularly in the production of innovative posters.

- Stanisław Wyspiański (1869–1907):

- Though more commonly associated with Young Poland, Wyspiański’s early poster designs influenced later avant-garde graphics.

- Władysław Skoczylas (1883–1934):

- Known for his woodcut prints, Skoczylas created bold and stylized works that celebrated Polish folk traditions.

Polish Modernist Painters

A number of Polish painters continued to innovate, blending traditional themes with modernist experimentation.

- Zofia Stryjeńska (1891–1976):

- Known as the “princess of Polish painting,” Stryjeńska incorporated folk motifs and decorative patterns into her modernist works.

- Jan Cybis (1897–1972):

- A painter associated with the Kapists (Paris Committee), Cybis explored vibrant color palettes and bold compositions inspired by French modernism.

Architecture and Design

The modernist emphasis on functionality and simplicity extended to Polish architecture and design.

- Warsaw Modernism:

- Architects such as Bohdan Pniewski and Józef Szanajca designed streamlined, functional buildings that reflected the principles of the Bauhaus.

- Furniture and Interiors:

- Polish designers embraced modern materials like steel and glass, creating innovative furniture and interiors that combined utility with elegance.

Themes of Modernism and Avant-Garde Movements

Polish modernist art was defined by its engagement with international trends and its commitment to innovation:

- Abstraction and Geometry: Movements like Constructivism and Unism emphasized formal harmony and abstraction.

- Cultural Synthesis: Avant-garde artists blended modernist aesthetics with traditional Polish motifs and themes.

- Social and Political Engagement: Many artists addressed the challenges of their time, from industrialization to the tensions of the interwar period.

Impact of World War II

The outbreak of World War II in 1939 brought an abrupt end to Poland’s avant-garde experiments. Many artists faced exile or hardship, and the art world’s focus shifted to documenting the horrors of war and preserving Polish culture under threat. Despite these challenges, the foundations laid during this period would influence post-war art in Poland and beyond.

Chapter 8: Post-War Polish Art: Socialist Realism and Beyond (1945–1990)

The post-war era in Poland was a time of profound artistic upheaval, shaped by the devastation of World War II and the imposition of Communist rule. Under Stalinist influence, the Polish government promoted Socialist Realism as the official art style, glorifying workers, peasants, and the ideals of socialism. However, this period also saw significant resistance from artists, who sought ways to innovate and express individual creativity within the confines of political control. By the 1960s, Poland’s art scene expanded to include abstraction, conceptual art, and performance, reflecting a broader global engagement.

Socialist Realism: Art Under the State (1945–1955)

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, Polish artists were tasked with rebuilding both physical and cultural landscapes. Under Communist rule, Socialist Realism became the mandated style, emphasizing accessible, optimistic imagery that glorified labor and the collective good.

- Key Features:

- Heroic depictions of workers, farmers, and industrial progress.

- Simplified, easily understood compositions with a clear ideological message.

- Monumental architecture and sculpture celebrating socialism.

- Notable Examples:

- Palace of Culture and Science, Warsaw:

- Gifted by the Soviet Union, this iconic building exemplifies Socialist Realist architecture, blending Polish motifs with Soviet grandeur.

- Włodzimierz Zakrzewski (1916–1992):

- Known for his Socialist Realist paintings depicting workers and industrial scenes, Zakrzewski was a leading artist of the era.

- Palace of Culture and Science, Warsaw:

The Thaw: Abstraction and Innovation (1956–1970)

After the death of Stalin in 1953, Poland experienced a cultural thaw under Władysław Gomułka’s leadership, allowing for greater artistic freedom. This period saw the rise of abstraction and experimentation in Polish art.

- Abstract Painting:

- Władysław Strzemiński (1893–1952):

- Although he died before the thaw, Strzemiński’s theories of Unism influenced younger artists, who embraced non-figurative art.

- Tadeusz Kantor (1915–1990):

- Kantor’s early abstract works, inspired by Constructivism, set the stage for his later innovations in performance and theater.

- Władysław Strzemiński (1893–1952):

- Polish School of Posters:

- Polish graphic designers gained international acclaim during this period, blending abstraction, surrealism, and wit.

- Henryk Tomaszewski (1914–2005):

- A pioneer of the Polish School of Posters, Tomaszewski’s designs combined bold imagery with conceptual depth.

Conceptual Art and Performance (1970s)

As the political climate tightened again in the late 1960s, many Polish artists turned to conceptual and performance art as forms of subtle resistance.

- Tadeusz Kantor:

- Kantor became a leading figure in experimental theater, blending visual art and performance in works like The Dead Class (1975), which explored memory, loss, and history.

- Jerzy Beres (1930–2012):

- Beres used performance and sculpture to critique political oppression, often incorporating Polish national symbols in provocative ways.

The Rise of Film and Photography

Polish artists also embraced film and photography as mediums for exploring contemporary life and documenting social change.

- Andrzej Wajda (1926–2016):

- Wajda’s films, such as Ashes and Diamonds (1958), combined stark realism with poetic imagery, reflecting Poland’s post-war struggles.

- Zofia Rydet (1911–1997):

- Rydet’s photographic series Sociological Record (1978–1990) captured intimate portraits of rural Polish life, blending ethnography with artistic vision.

The Solidarity Movement and Art as Protest (1980s)

The rise of the Solidarity movement in the 1980s, which challenged Communist rule, inspired a wave of politically charged art.

- Political Posters:

- Artists created bold graphic designs supporting Solidarity, often using symbolism and humor to bypass censorship.

- Jerzy Kalina (b. 1944):

- Kalina’s installations, such as Intervention in the Water (1980), reflected the tensions and aspirations of the Polish people during this time.

Themes of Post-War Polish Art

The art of this period reflects the complex interplay between political control and creative freedom:

- Adaptation and Resistance: Artists navigated the challenges of Socialist Realism, finding ways to innovate within its constraints or resist it outright.

- National Identity: Many works emphasized Poland’s cultural heritage, using traditional motifs as symbols of resilience.

- Experimentation: From abstraction to performance, Polish artists embraced a wide range of styles and media to express their visions.

The Transition to Contemporary Art

By the late 1980s, the fall of Communism in Poland opened the door to even greater artistic freedom and international collaboration. The foundations laid by post-war artists provided a strong platform for the emergence of contemporary Polish art in the 21st century.

Chapter 9: Contemporary Polish Art (1990–Present)

The fall of Communism in 1989 ushered in a new era for Polish art, characterized by freedom, global engagement, and an exploration of national identity in a rapidly changing world. Contemporary Polish artists have embraced a wide range of media, from painting and sculpture to video installations and digital art, gaining international recognition for their innovation and critical engagement with history, politics, and culture.

Global Recognition of Contemporary Polish Artists

Poland’s transition to democracy and its integration into global markets allowed its artists to emerge on the international stage.

- Wilhelm Sasnal (b. 1972):

- A leading contemporary painter, Sasnal’s works address themes of memory, history, and consumer culture.

- His painting Airplanes (2001) reflects the lingering impact of 20th-century conflicts on collective memory.

- Paulina Olowska (b. 1976):

- Olowska blends retro aesthetics, Polish design, and feminist themes in her paintings and installations, such as Alphabet (2005).

- Agnieszka Polska (b. 1985):

- Polska uses video and digital media to explore themes of communication, memory, and environmental concerns.

Art and Memory: Revisiting History

Polish contemporary art often grapples with the country’s complex history, from World War II to the Communist era.

- Mirosław Bałka (b. 1958):

- Known for his minimalist sculptures and installations, Bałka addresses themes of trauma, memory, and identity. His work How It Is (2009), exhibited at the Tate Modern, is a haunting meditation on absence and emptiness.

- Joanna Rajkowska (b. 1968):

- Rajkowska’s public art installations, such as Greetings from Jerusalem Avenue (2002), use urban spaces to provoke conversations about memory and belonging.

Multimedia and Digital Innovation

Contemporary Polish artists are at the forefront of using digital media, video, and performance art to address contemporary issues.

- Katarzyna Kozyra (b. 1963):

- Kozyra’s provocative works challenge societal norms and explore themes of gender and identity. Her video installation The Bathhouse (1997) critiques traditional representations of the female body.

- Artur Żmijewski (b. 1966):

- Żmijewski’s politically charged videos, such as Them (2007), engage with collective identity and the dynamics of power.

Street Art and Public Engagement

Street art and public installations have become vital components of Poland’s contemporary art scene, reflecting the democratization of art.

- NEON Muzeum, Warsaw:

- This museum celebrates Poland’s neon signage legacy, blending nostalgia with contemporary design.

- Street Artists:

- Urban artists like M-City (Mariusz Waras) create large-scale murals that explore industrial and social themes.

Environmental and Social Concerns

As global issues like climate change and social justice gain prominence, Polish artists have incorporated these themes into their work.

- Cecylia Malik (b. 1975):

- Malik’s performance art and photography focus on environmental activism, such as her project 365 Trees, which highlights urban deforestation.

- Julita Wójcik (b. 1971):

- Wójcik’s participatory installations, such as The Rainbow (2011), address themes of community, equality, and public space.

Art Institutions and Festivals

Poland’s vibrant art scene is supported by world-class museums, galleries, and festivals.

- Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw:

- A hub for contemporary art, showcasing works by both Polish and international artists.

- Kraków Photomonth Festival:

- A leading photography event that highlights contemporary trends and experimental practices.

- Wrocław Contemporary Museum:

- Focused on promoting modern and contemporary art, the museum explores themes of postmodernity and globalization.

Themes of Contemporary Polish Art

Contemporary Polish art reflects a diverse and evolving cultural landscape:

- Memory and Identity: Artists grapple with Poland’s history while exploring personal and collective identity in a globalized world.

- Innovation and Technology: Multimedia and digital art push the boundaries of traditional practices.

- Engagement and Activism: Many works address pressing social and environmental issues, fostering dialogue and awareness.

Looking Ahead

Poland’s contemporary art scene is a testament to its resilience and adaptability, blending tradition with innovation. As Polish artists continue to engage with global issues and expand their influence on the international stage, they reaffirm the nation’s enduring cultural legacy.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Polish Art

The story of Polish art is one of resilience, reinvention, and profound cultural expression. Across centuries, Poland’s artists have navigated periods of great prosperity, political upheaval, and profound social change, all while contributing richly to the broader tapestry of European and global art. From the grandeur of medieval cathedrals to the innovative multimedia works of today, Polish art reflects a nation’s spirit and its unyielding dedication to preserving and evolving its cultural identity.

Themes Across Time

Polish art has consistently embraced and reflected key themes:

- National Identity: Whether through the Sarmatian portraits of the Baroque era or the Romantic landscapes of the 19th century, Polish art has celebrated its unique heritage and served as a vessel for national pride.

- Cultural Synthesis: Situated at the crossroads of Eastern and Western Europe, Poland has skillfully blended influences from its neighbors with its own traditions.

- Innovation and Experimentation: From Constructivist pioneers like Władysław Strzemiński to contemporary multimedia artists like Agnieszka Polska, Polish artists have continually pushed boundaries and embraced new technologies.

Poland’s Global Contributions

Poland’s contributions to the global art scene are significant and enduring:

- The Romantic masterpieces of artists like Jan Matejko and composers like Fryderyk Chopin shaped European culture.

- Avant-garde movements in the interwar period influenced the trajectory of modern art.

- Contemporary artists continue to engage with critical global issues, earning recognition on the world stage.

A Living Tradition

As Polish art moves forward, it maintains its deep connections to history while embracing the challenges and opportunities of the present. Institutions, festivals, and a thriving creative community ensure that Poland’s art scene remains vibrant, relevant, and impactful.

Poland’s art is not only a mirror of its past but also a beacon for its future—bold, innovative, and deeply rooted in a rich cultural legacy that continues to inspire.