Pennsylvania Impressionism was a regional American art movement that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Inspired by French Impressionism (1860s–1890s) but adapted to the American landscape, these artists captured seasonal changes, rural life, and natural light with expressive brushwork. Unlike their European counterparts, Pennsylvania Impressionists emphasized bold color, structured compositions, and thick impasto techniques. Their paintings reflected a uniquely American interpretation of Impressionism, blending traditional realism with the vibrancy of modern painting.

The movement began around 1898, when a group of artists—including Edward Redfield (1869–1965), Daniel Garber (1880–1958), and Walter Schofield (1867–1944)—settled in New Hope and Solebury along the Delaware River. Many had trained in Philadelphia and Paris, where they absorbed Impressionist techniques but sought to apply them to distinctly American subjects. Unlike French Impressionists, who often painted city scenes, Pennsylvania Impressionists focused on the changing countryside, small villages, and river landscapes. Their ability to capture the character of Pennsylvania’s landscape helped define one of America’s most important regional art movements.

The New Hope School, as it was sometimes called, became one of the most influential art colonies in the United States. The artists lived close to nature, often painting outdoors in a single session to capture fleeting light and atmosphere. Their work was regularly exhibited in Philadelphia, New York, and Chicago, where it gained national recognition. Today, Pennsylvania Impressionism is celebrated for its rich textures, dynamic compositions, and enduring connection to the American landscape.

This article explores the history, techniques, key figures, and lasting impact of Pennsylvania Impressionism. By examining its roots in American art, major artists, and stylistic innovations, we can understand why this movement remains one of the defining chapters of American Impressionism.

The Origins of Pennsylvania Impressionism

Pennsylvania Impressionism developed as part of a broader shift in American painting during the late 19th century. The Industrial Revolution (c. 1760–1840) had transformed much of the American landscape, leading many artists to seek rural subjects as a retreat from urbanization. At the same time, the influence of European Impressionism was spreading across America, reshaping traditional realist landscape painting. These combined forces led to the rise of a distinctly American form of Impressionism in Pennsylvania.

Many of the Pennsylvania Impressionists studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), founded in 1805. PAFA was one of the leading art schools in the United States, training painters in both academic realism and modern techniques. Several artists, including Edward Redfield and Daniel Garber, also traveled to Paris to study at the Académie Julian, where they were introduced to French Impressionist methods. However, rather than imitating Monet and Renoir, they returned to the U.S. with the goal of creating an Americanized version of Impressionism.

The Bucks County region, with its rolling hills, winding rivers, and historic farms, provided an ideal setting for this movement. The area’s changing seasons and atmospheric conditions made it a perfect subject for artists who wanted to capture fleeting light and mood. Unlike the industrialized cities of the East Coast, Bucks County still retained a sense of untouched rural beauty, which these artists sought to preserve on canvas.

By the early 1900s, New Hope had become a thriving artist colony, attracting painters from across the country. The Delaware River, covered bridges, and historic barns became some of the most frequently depicted subjects. Many Pennsylvania Impressionists worked outdoors in freezing winter temperatures or under the bright summer sun, painting the landscape in all its seasonal diversity. This dedication to plein air painting became one of the hallmarks of the movement.

Key Artistic Techniques and Innovations

Pennsylvania Impressionists adopted many of the techniques of French Impressionism, but they developed their own distinct approach to light, color, and texture. Their brushwork was often bolder and more dynamic, using thick layers of paint (impasto) to create depth and movement. Unlike the delicate, soft brushstrokes of Monet or Renoir, Pennsylvania Impressionists applied vigorous, expressive strokes, often completing a painting in a single session outdoors.

Color was another defining feature of the movement, as artists experimented with vibrant hues and rich contrasts. Pennsylvania Impressionists frequently painted autumn and winter landscapes, using fiery oranges, deep blues, and brilliant whites to emphasize the changing seasons. In works by Redfield and Schofield, snow is not just white—it reflects shades of violet, blue, and gold, creating an almost luminous effect.

Plein air painting was central to their approach, as they aimed to capture light and atmosphere in real-time. Instead of working from sketches in a studio, artists set up their easels on riverbanks, in forests, or in open fields, painting directly from nature. This allowed them to record the ever-changing light conditions, producing paintings that felt immediate and alive.

Compositionally, Pennsylvania Impressionists balanced spontaneity with structure, ensuring their landscapes retained a solid, organized sense of space. Unlike some European Impressionists, who focused on fleeting, momentary impressions, Pennsylvania artists often included detailed elements such as fences, farmhouses, or distant hills, grounding their paintings in a strong sense of place.

The Great Masters of Pennsylvania Impressionism

Edward Redfield (1869–1965) – The Boldest Brushwork

- Known for thick impasto, dynamic compositions, and energetic plein air painting.

- Often completed large canvases in a single day, capturing fleeting light and movement.

- Major work: Winter Sunlight (1911) – a bright, snow-covered landscape with striking contrasts of light and shadow.

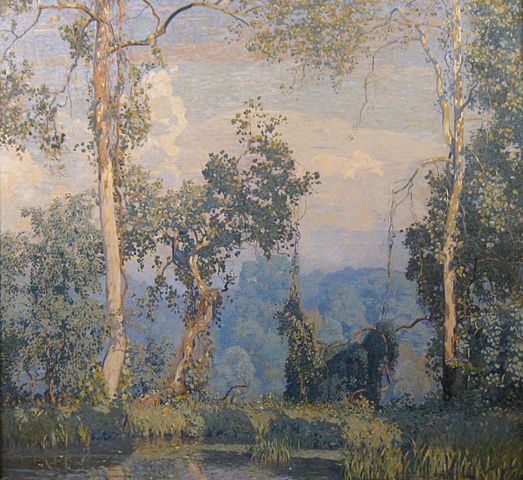

Daniel Garber (1880–1958) – The Decorative Impressionist

- Blended Impressionism with a sense of decoration and detail, creating luminous, glowing landscapes.

- Specialized in river scenes, sunlit forests, and delicate patterns of light filtering through trees.

- Major work: Taniers Creek (1918) – a dreamlike landscape with intricate brushwork and atmospheric effects.

Walter Schofield (1867–1944) – The Painter of Pennsylvania Winters

- Painted powerful winter scenes, emphasizing color and texture.

- His work combined Impressionist brushwork with a strong, structured composition.

- Major work: Overlooking the Valley (c. 1920s) – a vibrant winter scene with dynamic brushwork and thick layers of paint.

William Lathrop (1859–1938) – The Founder of the New Hope School

- Helped establish New Hope as an artist colony, fostering a community of plein air painters.

- His landscapes emphasized atmosphere, soft light, and a poetic connection to nature.

- Major work: The Delaware at New Hope (1916) – a misty, peaceful depiction of the river at dawn.

The Influence of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA)

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) played a crucial role in shaping Pennsylvania Impressionism. Founded in 1805 in Philadelphia, PAFA was the first art school and museum in the United States, providing formal training for many American artists. Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, PAFA promoted a balance between traditional academic realism and emerging modern styles, making it a key center for artistic development. Many Pennsylvania Impressionists, including Edward Redfield, Daniel Garber, and Walter Schofield, studied at PAFA before traveling abroad.

During the 1880s and 1890s, PAFA encouraged its students to study in Paris, where they were exposed to French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist movements. The Académie Julian, one of the leading art schools in Paris, trained many future Pennsylvania Impressionists, teaching them plein air techniques, color theory, and spontaneous brushwork. However, when these artists returned to the United States, they sought to adapt these European techniques to American subjects, moving away from the urban and social themes of French Impressionism.

PAFA’s emphasis on landscape painting also contributed to the rise of Pennsylvania Impressionism as a regional movement. Instructors like Thomas Eakins (1844–1916) promoted the study of nature, anatomy, and direct observation, influencing how Pennsylvania Impressionists approached their compositions. While PAFA initially favored historical and figurative painting, by the early 20th century, it fully embraced landscape painting as a major genre, reinforcing the movement’s legitimacy.

By the 1920s and 1930s, PAFA played a critical role in preserving and promoting Pennsylvania Impressionism. Many New Hope artists exhibited at PAFA’s annual exhibitions, helping bring their work to national attention. Even as modernist movements such as Cubism, Futurism, and Abstract Expressionism gained popularity, PAFA continued to support traditional landscape painting, ensuring that Pennsylvania Impressionism remained an essential part of American art history.

The New Hope Art Colony and Its Impact

New Hope, Pennsylvania, became the heart of the Pennsylvania Impressionist movement, attracting artists who sought to live and work in nature. By the early 20th century, New Hope and the surrounding Bucks County region had developed into one of the most important art colonies in America, much like Old Lyme in Connecticut and Woodstock in New York. The community fostered a spirit of collaboration, artistic experimentation, and dedication to plein air painting.

The New Hope colony was initially founded by William Lathrop in the late 1890s, and it quickly attracted painters such as Edward Redfield, Daniel Garber, and Charles Rosen (1878–1950). Many artists purchased farmhouses and converted barns into studios, painting the surrounding countryside, rivers, and changing seasons. The Delaware River, rolling hills, and historic villages became recurring subjects in their work. Unlike urban-based artists, who often depicted city life and industrialization, Pennsylvania Impressionists celebrated rural American beauty and traditional landscapes.

The Phillips Mill community, established in 1913, became the central hub for New Hope artists, hosting exhibitions, gatherings, and discussions. The annual Phillips Mill Art Exhibition, which still continues today, helped promote Pennsylvania Impressionism to a wider audience. The cooperative environment allowed artists to exchange ideas and techniques, fostering a shared artistic vision while maintaining individual styles.

One of the defining aspects of the New Hope Art Colony was its emphasis on plein air painting and the immediacy of nature. Unlike studio-bound painters, these artists worked directly in the field, often braving harsh weather conditions to capture the atmospheric effects of light and shadow. Their dedication to realism and the American landscape ensured that their work remained distinct from European Impressionism, creating an artistic legacy that endures to this day.

The Decline of Pennsylvania Impressionism

By the mid-20th century, Pennsylvania Impressionism began to decline as new artistic movements gained prominence. The rise of Modernism, Abstract Expressionism, and Regionalism shifted attention away from traditional landscape painting. Artists such as Jackson Pollock (1912–1956) and Willem de Kooning (1904–1997) championed non-representational abstraction, making Impressionist techniques seem old-fashioned.

Economic and societal changes also played a role in the movement’s decline. The Great Depression (1929–1939) reduced patronage for landscape painters, as collectors and museums favored modernist and socially conscious art. Additionally, the urbanization and industrialization of America changed the national artistic focus, leading to an emphasis on cityscapes, industrial subjects, and conceptual art.

Despite its decline in popularity, Pennsylvania Impressionism remained influential, particularly among American regional painters. Many artists continued to paint in the Impressionist style, though their works received less critical attention than before. However, dedicated collectors and institutions preserved and promoted Pennsylvania Impressionist paintings, ensuring that their artistic legacy endured.

In recent decades, there has been a renewed interest in Pennsylvania Impressionism, particularly through museum exhibitions, scholarship, and art market appreciation. The movement’s dedication to natural beauty, American landscapes, and plein air techniques continues to inspire contemporary artists. Today, Pennsylvania Impressionism is recognized as one of the most significant regional movements in American art history, preserving a unique blend of Impressionism and American realism.

The Lasting Legacy of Pennsylvania Impressionism

Although Pennsylvania Impressionism declined as a dominant movement, its impact on American landscape painting and regional art traditions remains strong. The artists of New Hope and Bucks County created a distinctive form of Impressionism, one that reflected both European influences and uniquely American themes. Their work laid the foundation for future generations of painters who sought to capture the beauty of the natural world.

Several major museums and institutions continue to preserve and celebrate Pennsylvania Impressionism. The James A. Michener Art Museum in Doylestown, PA, houses one of the largest collections of Pennsylvania Impressionist paintings. Other institutions, including the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), also feature significant works by Redfield, Garber, Schofield, and Lathrop. These collections ensure that new audiences can appreciate the movement’s contributions to American art.

Pennsylvania Impressionism also influenced later American realist and landscape painters, including artists working in the Hudson River School tradition. The movement’s emphasis on plein air painting and regional identity can be seen in contemporary landscape artists who continue to explore natural light, texture, and seasonal variation.

In the modern art world, where abstract and conceptual art dominate, Pennsylvania Impressionism remains a reminder of the enduring power of nature, light, and color. Collectors, historians, and painters continue to study and admire the works of New Hope School artists, ensuring that their vision of the American countryside remains alive.

Key Takeaways

- Pennsylvania Impressionism (1898–1940s) blended French Impressionist techniques with American rural landscapes.

- It was centered in New Hope and Bucks County, Pennsylvania, attracting artists who painted plein air seasonal landscapes.

- Key artists: Edward Redfield, Daniel Garber, Walter Schofield, and William Lathrop.

- The movement was influenced by PAFA, the Académie Julian, and the New Hope Art Colony.

- Although it declined in the mid-20th century, it remains an important part of American art history.