Long before the land we now call North Dakota was marked by railroads or fenced into townships, it was mapped in color, geometry, and movement by the art of American Indian peoples—particularly the Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Dakota, and Ojibwe. These cultures generated a visual language deeply tied to ritual, survival, and social memory. Unlike the European concept of fine art, their artistic traditions were not divorced from utility or spirituality. They were embedded in clothing, architecture, storytelling, and ceremony—in the way a tipi was painted, a robe was quilled, or a dance was costumed. In these works, the line between the beautiful and the necessary disappeared.

Sacred Geometry on the Plains

The earliest enduring aesthetic forms in the northern plains were neither figurative nor purely decorative: they were symbolic, abstract, and cosmological. The circular design of the earthlodge—used by Mandan and Hidatsa peoples—mirrored their understanding of the universe. Its central fire represented the sun; the entrance, the east; the sky-hole, a connection to the spirit world. This spatial symbolism extended to portable objects: shields, war shirts, and cradleboards were adorned with patterns that encoded prayers, visions, and clan affiliations. These were not “designs” in the Western sense, but cosmograms—microcosms of the universe made wearable.

Quillwork and beadwork further articulated this geometry. Before European contact, dyed porcupine quills were flattened and wrapped around sinew or leather to create patterns of remarkable intricacy. Triangles, diamonds, and concentric forms emerged, often representing protective spirits or sacred sites. After the introduction of glass beads by European traders in the 18th and 19th centuries, these same motifs were reinterpreted with dazzling chromatic intensity. Importantly, these forms were not overwritten by the new materials—they evolved. The medium changed, but the message remained legible within the communities that understood its codes.

Three recurring patterns exemplify this sacred abstraction:

- The four-pointed cross, signifying the cardinal directions and balance.

- The stepped triangle, symbolizing mountains or spiritual ascent.

- The zigzag or serpent line, often linked to lightning or transformation.

These visual codes were not static. They shifted across generations, adapted to personal visions, or responded to historical trauma. But they persisted, grounding the work of even contemporary American Indian artists in a lineage that predates the state by centuries.

Ledger Art and the Transition to Paper

One of the most poignant transformations in American Indian visual expression emerged during the late 19th century with the rise of ledger art. As traditional lifeways were disrupted by war, disease, and displacement, many Plains artists began using ledger books—often supplied by missionaries or soldiers—as new surfaces for expression. These bound books, originally intended for accounting, became the site of both resistance and reinvention.

The transition from hide painting to paper drawing was not merely technological. It was a shift in audience, format, and even temporality. On buffalo hides, the painted narrative of a hunt or battle was communal and ceremonial; on paper, it became more intimate and portable, a kind of visual diary. Yet the content often remained the same: depictions of warfare, courtship, ceremony, and cosmology, rendered in fine pencil or colored crayon with the same linear dynamism seen in older forms.

The Dakota artist Amos Bad Heart Bull, for example, documented not only traditional scenes of horse raids and dances but also images of American flags, rifles, and railroads—symbols of an encroaching order. His work is not nostalgic; it is forensic, trying to reconcile two overlapping worlds. Ledger art, in this way, became both a record of cultural continuity and a critique of cultural interruption. It was history from the ground level—drawn in silence, often by men held in prisons or confined to reservations, reasserting their presence on every page.

Ceremonial, Functional, Eternal

To think of American Indian art in pre-statehood North Dakota as purely visual is to miss its function as memory, protection, and invocation. Objects were made to carry power. A parfleche—painted rawhide envelope—held not only goods but a cosmological map. A feathered headdress encoded achievements and responsibilities. Even the simplest pipe bag or moccasin carried stories within its patterning. Each object was meant to be handled, worn, or given, and often destroyed in ceremony. Permanence was not the point. Reverence was.

The persistence of these forms—despite forced assimilation, boarding schools, and religious bans—speaks to a deeper continuity. Knowledge was preserved orally, embodied in gesture, remembered through making. Among the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara, ceremonial bundles contained sacred items passed across generations. Their care and use were as important as their contents. A rawhide rattle used in a medicine ceremony might outlast any painting on canvas.

One narrative often cited in Hidatsa tradition recounts a woman named Turtle Head Woman who dreamed of a powerful being that gave her a specific geometric design to paint on her robes. The vision was considered so important that it was adopted by others and eventually became associated with a clan. Her art was not a signature—it was a transmission.

Even in the early 20th century, anthropologists and collectors often failed to recognize this context. They sought beauty, rarity, or exoticism. They classified pieces as “craft” or “primitive art.” But for the makers, what mattered was the purpose and the prayer, not the preservation. Much of the work that has survived—now housed in collections from Bismarck to Berlin—was never meant to be seen in isolation. It was part of a ceremony that moved, sang, and ended.

The paradox of American Indian art before the state is that it was simultaneously everywhere and almost invisible to the colonial gaze. Painted lodges, tattooed faces, decorated tools, carved pipes—art saturated life, but it was not named as such by those who built museums and wrote art histories. Yet in quiet, defiant continuity, these traditions seeded a future. They form the deep root system beneath what North Dakota’s art would become: resilient, place-bound, and often misunderstood by those who fail to look long enough.

Pictographs and Petroglyphs in the Badlands

Before paper, before hides, before even the concept of a North Dakota, there were stones etched and painted with meaning. In the winding canyons and wind-scoured plateaus of the Badlands, the earliest artists in the region—ancestral to today’s American Indian tribes—left behind an archive of images carved into rock and painted onto cliff walls. These works, often centuries or even millennia old, are not silent fossils. They are visual traces of living systems: communication, vision-seeking, migration, boundary marking, and spiritual experience. Though often dismissed as primitive or merely decorative, the petroglyphs and pictographs of North Dakota hold their own complex visual grammar—and, increasingly, they demand to be read.

Stone as Canvas

The terrain of western North Dakota does not immediately suggest the permanence of great art. Erosion is constant; seasons brutal. Yet this very impermanence lends weight to the marks that have endured. At sites like Writing Rock near Grenora or Medicine Rock near Elgin, figures etched into sandstone boulders remain visible even after centuries of ice, rain, and wind. The technique of pecking or incising images into rock requires both time and intent—often involving the rhythmic striking of stone against stone, hour after hour, to create grooves deep enough to survive the elements.

The forms are rarely figurative in the Western sense. At Writing Rock, for instance, the most iconic glyphs resemble large thunderbirds with stylized, cross-shaped wings and circular heads. These motifs are not idiosyncratic: similar images appear across the Plains, from Alberta to Nebraska. Some scholars suggest they represent sky spirits or cosmological events. Others argue they mark territory or encode ceremonial knowledge. None of these interpretations are mutually exclusive. In cultures where the material, spiritual, and political were tightly interwoven, a single glyph could signify all three.

At nearby Medicine Rock, one finds handprints, buffalo tracks, suns, concentric circles, and abstract patterns whose meaning eludes easy translation. Oral histories of the Dakota and Hidatsa peoples connect these rocks to vision quests—places where young men and women, isolated from the village and fasting for days, would encounter spirits who left behind messages. The rock was not simply a surface for drawing. It was a participant. A threshold.

One particularly haunting example: a deep spiral carved into a vertical stone face that seems to trace the path of a journey inward. Whether it marks the location of a dream, a burial, or a celestial event, no one can say for certain. But its precision is unmistakable. The spiral is nearly perfect, and its alignment with the summer solstice sunrise—verified in recent decades by archaeologists—suggests an astronomical awareness more sophisticated than outsiders have often acknowledged.

Sites of Memory and Survival

These carvings and paintings are not dispersed randomly. They cluster around specific landscapes—ridges, water sources, rock outcroppings—with repeated spiritual significance. In American Indian cosmology, certain places are not just topographical features; they are beings, or doors between worlds. Rock formations were often seen as alive, with their own personalities and capacities to speak or respond. The images inscribed on them were not merely left behind—they were addressed to the place itself.

One such site, the so-called “Bear’s Den” near the Killdeer Mountains, features a small cave entrance lined with red ochre markings, many now faded. Local Mandan and Hidatsa stories speak of a spirit bear who lived in the hills and offered protection to those who honored him properly. The act of painting there was both an offering and an invocation. The ochre, mixed with animal fat and applied with fingers or primitive brushes, would glow freshly in the dim rock shelter, only to darken and flake with time—its ephemerality mirroring the conditions of the quest it represented.

During the 19th century, as American Indian tribes were pushed onto reservations and their sacred lands increasingly encroached upon, these rock sites took on another function: as repositories of memory. Elders would return to them, sometimes secretly, to teach the young. They pointed out old marks, told stories, recalled ancestors. These visits were acts of resistance. In a world where dances were banned and languages forbidden in schools, the rocks could not be silenced so easily.

Yet even in the 20th century, many of these sites were neglected or desecrated. Farmers plowed near them. Tourists defaced them. Some carvings were dynamited by early homesteaders who feared they might attract legal restrictions. Others were taken, stone by stone, and shipped to museums in Chicago or New York—divorced from their settings, their meanings fragmented.

Decay, Discovery, and Documentation

In recent decades, a slow but significant shift has occurred. Archaeologists, tribal historians, and artists have begun working together to map, preserve, and interpret the rock art of North Dakota—not as inert heritage, but as part of a living continuum. This is not a matter of decoding symbols, as if they were ancient puzzles, but of understanding the conditions and intentions behind their making.

Technological advances have helped. Photogrammetry and 3D scanning now allow researchers to capture surface data invisible to the naked eye. Infrared imaging can reveal faded pigments. But even the most precise digital model cannot replace standing before a glyph as the light shifts across its surface, or hearing a Dakota elder describe the spirit that dwells in the stone. The meaning is not only in the mark—it’s in the context, the repetition, the story.

Contemporary artists have also taken inspiration from these ancient works. In 2016, Ojibwe painter Jonathan Thunder created a series of mixed-media pieces that reimagined petroglyphs as digital animations, showing thunderbirds rising from cracked stone and figures dancing across layered time. His work does not attempt to recreate the past, but to extend its relevance—to insist that these old marks still vibrate in the present.

Three recent preservation efforts reflect this growing awareness:

- Writing Rock State Historic Site, now protected and interpreted in consultation with tribal experts.

- Medicine Rock, currently undergoing a reevaluation of its spiritual status and accessibility protocols.

- Collaborative documentation projects between UND researchers and Mandan elders to record oral histories linked to carvings before they are lost.

These efforts are not acts of nostalgia. They are acts of continuity. The rock art of the Badlands is not a prelude to history—it is part of an unbroken story whose next chapters are still being written in ceremony, scholarship, and art.

The carvings in stone whisper what paintings and museums often fail to say: that art was always here, watching, waiting, weathering the wind—not as a record of what was lost, but as proof that something essential remains.

Forts, Missions, and Motifs: 19th-Century Colonial Aesthetics

By the early 1800s, the visual world of what is now North Dakota began to change—subtly at first, and then with accelerating force. Alongside the ancient traditions of American Indian expression and the enduring marks carved into the Badlands came a new wave of aesthetic imposition: the art of soldiers, surveyors, missionaries, and traders. This was not yet the full machinery of American empire, but it was a prelude. At military forts and Christian missions, in ledger books and illustrated bibles, art became an instrument of interpretation, assimilation, and authority. These colonial images were not simply reflections of their time—they were tools of it, framing land, people, and history through imported visions.

Painting the Conquest

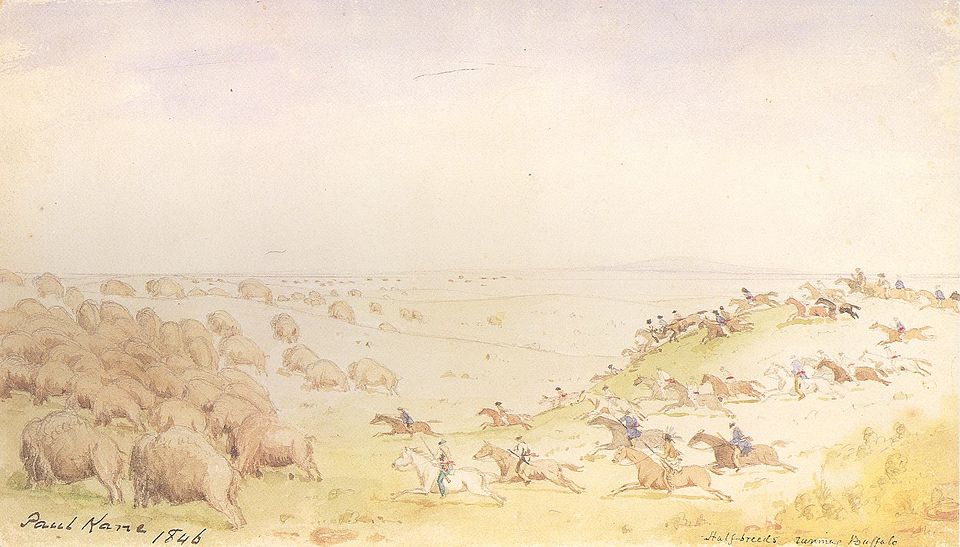

Art arrived with the frontier army long before photography could reliably function on the plains. Officers stationed at Fort Union or Fort Abraham Lincoln frequently kept sketchbooks, some as personal journals, others as proto-ethnographic records. Their drawings captured scenes of buffalo hunts, American Indian dances, and fort life with a mixture of fascination, detachment, and paternalism. These were not neutral images. They were efforts to fix an understanding of a world that was, from the colonial perspective, wild and rapidly vanishing.

The most well-known example of this is the work commissioned by George Catlin, whose travels through the Upper Missouri in the 1830s produced a vast portfolio of portraits, landscapes, and scenes of ceremonial life among the Mandan, Hidatsa, and other Plains tribes. Though not North Dakotan by residence, Catlin spent extended time at Fort Clark and painted Chief Four Bears (Ma-to-toh-pa), a leader of the Mandan whose haunting, confrontational gaze survives in oils now housed at the Smithsonian.

Catlin saw himself as a preservationist—a recorder of “noble savages” on the edge of extinction. But his lens was deeply flawed. He sanitized complex societies, exoticized bodies, and framed American Indians as aesthetic subjects rather than political actors. His portraits, though often technically accomplished and valuable as historical records, were laden with the implicit message that these people were beautiful in their obsolescence.

Not all military artists were so romantic. At Fort Rice, an unknown draftsman sketched a detailed panorama of the Missouri River’s edge, featuring rows of infantry tents, fenced fields, and a small group of Dakota figures rendered almost as afterthoughts. The central focus was the fort itself—a geometric order imposed on the undulating terrain. The image, in its composition alone, reveals the intention: domination through grid, presence through drawing.

These visual conventions would soon shape the region’s first maps, survey sketches, and even land advertisements—every frame reinforcing a story that the territory was “open,” “unsettled,” or “waiting.” The erasure was not just political; it was aesthetic.

Dakota and Métis Craft Traditions

Yet even as these colonial images proliferated, alternative traditions persisted—especially among the Dakota and Métis communities, whose art resisted reduction. The Métis, of mixed Indigenous and European heritage, developed a hybrid decorative language rooted in both Ojibwe floral beadwork and French embroidery traditions. By the mid-19th century, Métis women in what is now North Dakota were producing some of the most intricate quilled and beaded items on the continent: sashes, pipe bags, gun cases, and fire bags, often adorned with vibrant floral sprays set against dark wool cloth.

These pieces functioned as both identity markers and economic tools. Métis crafts circulated through fur trade networks that linked Fort Garry, Fort Union, and St. Paul. A beaded bag might carry tobacco one year and a political message the next. While military art sought to codify and contain, Métis decorative arts flexed, adapted, and travelled.

Dakota artists continued their own beadwork and painted traditions under increasing pressure. Christian missions—such as those established by the Presbyterians and Episcopalians—offered education in Western visual forms, including drawing and textile design. Missionary women sometimes encouraged Dakota girls to apply their beadwork skills to more “acceptable” patterns, like crosses or alphabet samplers. But resistance thrived in the margins.

A remarkable example survives in a Dakota-made vest from the 1870s, housed at the North Dakota Heritage Center. At first glance it appears to follow Victorian lines: symmetrical, neat, almost European. But closer inspection reveals stylized horses, medicine wheels, and a single, unmistakably Dakota handprint sewn into the back lining—a quiet rebellion against erasure.

The Visual Politics of Settlement

By the late 1800s, as the Dakota Territory opened to homesteaders and railroads extended their grids across the prairie, the visual aesthetic of North Dakota underwent a further transformation. It became increasingly focused on domestication—not just of land, but of image. Paintings and illustrations showed log cabins surrounded by tidy fields, white church steeples rising from new towns, and endless skies unbroken by tipi poles.

Settlement photography emerged as both documentation and propaganda. Photographers such as Frank Fiske, based at Fort Yates on the Standing Rock Reservation, walked the line between portraiture and politics. Fiske, whose studio operated in the early 20th century but whose influences were rooted in the earlier century’s ethos, captured both Dakota dignitaries in full regalia and scenes of assimilation: children in school uniforms, families in front of frame houses. His work is complex—neither wholly exploitative nor fully autonomous—often depending on the context of display and interpretation.

In visual terms, the 19th century in North Dakota was marked by three entwined forces:

- Colonial image-making, designed to capture and categorize Indigenous life as something passing.

- American Indian artistic continuity, often carried in bead, quill, and hide under conditions of profound disruption.

- Emergent settler aesthetics, which sought to naturalize the presence of fences, churches, and government outposts as self-evident features of the landscape.

Each of these currents left visual residue still legible in today’s collections, archives, and oral traditions. But they did not coexist peacefully. They clashed, often violently, on the walls of forts and missions—where one kind of image was imposed, and another survived in shadow.

The 19th-century art of North Dakota, then, cannot be cleanly divided between “European” and “Indigenous” styles. It must be read as a series of visual negotiations over meaning, land, and future. The margins of a missionary schoolgirl’s sampler, the faded strokes on a Dakota war shirt, the draftsmanship of a fort-bound lieutenant—all carry the tensions of a place being redefined in real time.

The Era of Surveyors and Artists: Mapping a Territory Through Art

Before the territory of North Dakota became legible as a geopolitical entity—before it was drawn into statehood, parceled into counties, or sliced by highways—it was shaped through acts of visual translation. Cartographers, military illustrators, and expedition artists rendered the land not only as space to be understood but as property to be possessed. These images, some of them detailed and exquisitely composed, served both scientific and symbolic functions. They mapped topography and ambition alike. And in doing so, they helped reframe a lived landscape into a landscape for sale.

Railroad Commissions and Western Fantasies

The expansion of the Northern Pacific Railway across Dakota Territory in the 1870s marked a turning point in how the region was depicted. For railroad companies, maps were not enough. They needed visuals that could attract settlers, investors, and Eastern audiences eager for the promise of the frontier. To that end, railroads commissioned artists to accompany survey expeditions and return with picturesque views of the open plains, wide rivers, and majestic buttes.

Among the most influential of these projects was the 1871 survey led by General Henry T. Blake, which employed artists like Henry Jackson and photographers like William Henry Illingworth. Though primarily based in what would become Montana, their works often extended into the western reaches of North Dakota. The images that emerged showed a territory seemingly waiting for cultivation: unpeopled, sunlit, and pristine. Even where American Indian encampments appeared, they were framed as temporary or romantic—part of a fading past rather than a present presence.

These railroad images often exaggerated the landscape’s gentleness. The rolling plains of central Dakota were rendered as near-pastoral, inviting comparisons to classical European scenery. The arid badlands were softened, their strangeness muted. Rivers were widened, skies brightened. The effect was not accidental. It was a visual seduction, promising an Edenic frontier to those willing to buy a ticket west.

Some of the printed lithographs from this period circulated widely in Eastern cities, appearing in Harper’s Weekly or framed in the homes of land agents. They formed part of a larger feedback loop: art informed perception, perception informed policy, and policy reshaped the land itself. In a sense, these early visualizations were speculative renderings—not unlike architectural drawings of buildings not yet constructed.

Karl Bodmer’s Ethnographic Eye

More complex and enduring than the promotional art of the railroads was the work of Karl Bodmer, a Swiss artist who accompanied the German naturalist Prince Maximilian of Wied on a Missouri River expedition from 1832 to 1834. While their travels predate the height of U.S. expansion into Dakota Territory, their extended stay at Fort Clark—just south of present-day Stanton—produced some of the most detailed and respectful depictions of Mandan and Hidatsa life ever created.

Bodmer’s watercolors are notable for their restraint and precision. He did not reduce his subjects to stereotypes or strip their settings of complexity. In his famous portrait of Mato-Tope (Four Bears), Bodmer captures both the chief’s regalia and his unflinching expression. The quillwork on his shirt, the eagle feathers in his headdress, the painted face markings—all are rendered with care and specificity. These were not generalized “natives.” They were individuals with names, positions, and stories.

Perhaps even more striking are Bodmer’s scenes of daily life: a woman scraping a buffalo hide, children playing beside the lodge, a ceremonial gathering under a cottonwood. These images, unlike the grandiose panoramas of later railroad art, are grounded in intimacy. They suggest a different kind of mapping—one not based on grids and distances, but on social relations and lived rhythms.

Yet even Bodmer’s work, as nuanced as it was, served European ends. His illustrations were later published in atlases meant to accompany scientific texts, helping to establish the Upper Missouri as a site of ethnographic interest. In the long arc of colonial image-making, such depictions walked a fine line: they preserved what they also helped to exoticize.

Bodmer’s legacy, however, continues to complicate the narrative. His paintings are now housed in collections as far-flung as Basel and Omaha, and they remain among the few 19th-century European records that American Indian communities themselves sometimes consult when reconstructing regalia, protocols, or village layouts lost to time and colonization.

Lithographs of Dominion

As statehood approached in the 1880s, the production of official imagery accelerated. County atlases, land plats, and promotional lithographs filled with detailed bird’s-eye views began to circulate through the Midwest. These works, often produced by firms like L.H. Everts & Co. or the Western Publishing House, combined cartography with illustration to sell a vision of order: churches, farms, rivers, rail lines—all perfectly aligned with Manifest Destiny.

One such atlas, published in 1884, features panoramic lithographs of Bismarck, Fargo, and Grand Forks. The cities appear almost utopian in their symmetry. Grain elevators gleam. Horse-drawn wagons roll down graded streets. The Missouri River meanders calmly past newly platted neighborhoods. There is no trace of resistance, no dust, no Dakota presence. It is an aesthetic of dominance—precise, crisp, and eerily void.

The visual format of these atlases helped codify a new sense of place: one defined not by sacred geography or oral tradition, but by surveyed acreage, taxable property, and civic ambition. Even the act of drawing the town became a political gesture. It said, “this is real, this is ours, and it will endure.”

But in retrospect, these lithographs often feel like overstatements. Many of the early buildings depicted were wood-framed, prone to fire, or quickly replaced. Some of the towns never grew into their illustrated promise. What survives is the image itself—a fossil of optimism, framed by quiet erasures.

And yet, across the margins of these documents, one occasionally finds an anomaly: a painted tipi near a rail depot, or a solitary figure on horseback gazing across a vast, undivided prairie. These small insertions, intentional or not, suggest the ghost of the old world, still faintly visible beneath the inked lines of a new one.

Prairie Impressionism and the Arrival of Easel Painting

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, North Dakota’s visual culture shifted again—not with the stark violence of conquest or the deliberate calculations of cartographers, but with a subtler transformation: the arrival of easel painting. Artists trained in European or Eastern American traditions began to set up studios in Fargo, Bismarck, and Grand Forks. Some were recent arrivals; others were local enthusiasts responding to national currents. In either case, the work they produced marked a new approach to seeing the land. No longer just a space to be mapped, claimed, or mythologized, the North Dakota landscape became a subject for atmospheric interpretation—for light, color, and form. This was the dawn of Prairie Impressionism, a movement often overshadowed by its coastal cousins but rooted in the same desire: to make the fleeting visible.

Imported Ideals, Local Light

Easel painting arrived in North Dakota through teachers, immigrants, and traveling exhibitions. Many of the region’s first art instructors had studied at institutions like the Art Institute of Chicago or the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, bringing with them a curriculum steeped in tonalism, realism, and early modernist currents. These artists, in turn, encountered a landscape unlike any they had known: vast, horizon-bound, often empty to the eye yet rich in subtle shifts of weather and vegetation.

This new visual field required adjustment. The strong verticals of Eastern forests gave way to long, unbroken planes. The color palette changed, too—blues grew cooler, ochres paler, greens more sun-bleached. And the light, so often the chief actor in Impressionist painting, behaved differently here: drier, higher, and more insistently horizontal.

One early adapter was F. W. Stiegele, a Fargo-based painter active in the 1910s, known for his gently expressive renderings of homesteads, tree rows, and cultivated fields. His work rarely ventured into abstraction, but it flirted with the dissolving boundaries of form common to Impressionism. A barn might shimmer slightly in a haze of summer heat; a snowbank might catch faint pinks and violets at dusk. In Stiegele’s paintings, there is always the sense of a moment just about to change.

Another key figure was Margaret Cable, better known for her ceramics but also a painter of regional landscapes. Cable’s work at the University of North Dakota helped establish a studio environment that valued close observation and local subjects. Her small-scale oil studies of the Red River Valley—never widely exhibited—display a sensitivity to light and atmosphere that rivals more celebrated Impressionist canvases from New England or California.

These painters were not revolutionaries. They were interpreters. But their interpretations helped recast a land long represented as austere or adversarial into one capable of softness, mystery, and even pleasure. The prairie, under their brush, was no longer only a frontier—it became a place of mood.

The Rise of Regional Landscapes

By the 1920s and ’30s, regionalism had become an identifiable movement in American art, with Midwestern artists like Grant Wood, Thomas Hart Benton, and John Steuart Curry dominating national attention. North Dakota did not produce names of such fame, but it cultivated its own regionalist response—a quieter, more introspective version, attuned to agricultural rhythms and northern weather.

Local painters, often affiliated with colleges or women’s clubs, produced scenes of wheat fields, rivers, bluffs, and barns with a blend of realism and personal lyricism. These works, often shown at county fairs or state exhibitions, became part of a shared visual vocabulary. They adorned school walls, post offices, and bank lobbies, reinforcing a collective understanding of place rooted not in spectacle but in stability.

This visual regionalism aligned with broader cultural trends: the valorization of the farmer, the distrust of cities, and the romanticization of rural life during the interwar period. Yet in North Dakota, such themes were not just aesthetic choices—they were lived realities. The Dust Bowl, economic depression, and population shifts all contributed to a heightened sense of place as both fragile and precious.

Three motifs recur in the landscape painting of this period:

- Grain elevators, rendered with reverence, rising like monuments above the plains.

- Abandoned homesteads, often depicted as melancholic ruins overtaken by grass and time.

- Snow scenes, in which absence becomes subject—fence posts disappearing into drifts, sky and earth merging in pale grays and blues.

These paintings, while sometimes dismissed as provincial, offered a distinct alternative to the urban modernism then reshaping American art. They held fast to representation not out of conservatism, but out of fidelity to a land that demanded to be seen patiently, from the ground.

From Idyll to Icon

As the 20th century advanced, some North Dakota artists began to push beyond gentle representation toward symbolic abstraction. The prairie, once rendered in observational detail, began to function as metaphor: for endurance, for silence, for a kind of spiritual minimalism. In this evolution, one can trace the transition from impressionism to a more distilled modernism—though always shaped by regional conditions.

A painter like Bertha Ralston, for example, moved from early realist portraits to increasingly stark compositions in the 1940s and ’50s, using prairie motifs as anchoring shapes in otherwise flattened spaces. Her use of color remained atmospheric, but her forms grew bolder, more abstract. A tree became a slash of black. A field became a single plane of umber. These were not decorative gestures—they were efforts to locate meaning in austerity.

Meanwhile, certain images—especially the grain elevator—emerged as visual icons, repeated across media and decades. No longer just part of a landscape, the elevator became the landscape. It symbolized not only agricultural might but verticality itself—a rare vertical in a world of horizontals. Painters, photographers, and later printmakers returned to it obsessively, seeking new ways to render its flat planes and geometric purity.

This iconography eventually fed into North Dakota’s public art. Murals in town halls, school auditoriums, and post offices began to incorporate stylized versions of fields, sunrises, and agricultural laborers. These images, often funded by federal programs like the Works Progress Administration, aimed to uplift and unify. They also codified a certain view of the prairie: heroic, productive, eternally golden.

But the best of these works resist cliché. They capture the tension between beauty and barrenness, between myth and weather. They understand that the land is not a backdrop but an actor—mutable, demanding, indifferent.

The arrival of easel painting in North Dakota did not spark a revolution. It seeded a way of seeing: slow, steady, and committed to place. From Impressionist light studies to symbolic fields, the painters of the plains shaped a visual language still visible in the region’s art today—rooted in the tension between transience and endurance.

Art from Isolation: Early 20th-Century Prairie Modernism

Modernism came late to North Dakota. It did not arrive with manifestos or cafés or avant-garde salons. It arrived in fragments—through textbooks, exhibitions, traveling lecturers, and the occasional trip east. But when it did take root in the early 20th century, it did so under distinct conditions: geographic isolation, extreme climate, and the grit of self-sufficiency. Rather than mimicking the cosmopolitan shock of European modernism, North Dakota artists developed a quieter, more austere form of experimentation—one attuned to solitude, endurance, and the abstract beauty of emptiness. It was a modernism not of ideology but of condition.

The Dakota Schoolhouses

One of the most unexpected incubators of early modernist aesthetics in North Dakota was the rural schoolhouse. These one-room buildings, scattered across the plains, served as more than just centers of elementary education. They were often the only public space in a township: a place for voting, worship, performances—and art. Inside their walls, generations of children learned not only their letters but the basics of drawing, composition, and color. The simplicity of materials—pencil, chalk, tempera—encouraged abstraction by necessity.

Teachers, many of them young women trained in Normal Schools or teacher’s colleges in Minnesota and Wisconsin, brought with them exposure to Art Nouveau, Arts and Crafts ideals, and, later, Bauhaus design principles. These influences filtered through their lessons. Symmetry, repetition, and geometric ornament appeared in classroom projects, wall murals, and even holiday decorations. Though modest, these expressions taught a generation to see form not merely as utility, but as aesthetic opportunity.

The art produced in these contexts is rarely archived or celebrated. It exists, when it survives at all, in yellowing portfolios in county museums or tucked inside the drawers of historical societies. Yet it reveals a crucial truth: that modernist experimentation in North Dakota was not confined to galleries or universities. It was seeded in chalk lines, paper cutouts, and ink drawings made by children who had never seen a skyscraper or a Picasso but knew how to render a barn into cubes and a prairie into stripes.

Rural Women with Brushes

While art centers elsewhere lionized the male genius, North Dakota’s early 20th-century art was often sustained by women—teachers, farmers’ wives, widows, and daughters—who painted in the margins of daily labor. Their work, typically small in scale and domestic in subject, veered toward abstraction not through manifesto but through minimalism. With limited resources and no need to flatter patrons, they painted what they knew: empty rooms, lone trees, stormy skies, fields in late afternoon.

One example is Clara Mairs, originally from Minnesota but whose etchings and paintings circulated in Dakota art clubs. Her figures—elongated, stylized, and often surreal—found purchase with North Dakota women who organized exhibitions through Federated Women’s Clubs or YWCAs. These gatherings, often held in church basements or borrowed storefronts, introduced experimental ideas not as revolutions but as whispers.

In Mandan and Valley City, small networks of women painters emerged, often sharing supplies and techniques. The absence of a commercial art market meant freedom from market expectations—but also a lack of recognition. Their names do not appear in textbooks. Yet their work—still lifes edged with angular shadows, portraits drained of sentiment, prairie scenes rendered in blocks of pure color—bears the mark of a distinctly northern modernism.

A few artists managed to reach beyond the region. Hazel Thorson, trained briefly at the Art Students League in New York, returned to North Dakota to teach but continued to exhibit linocuts and woodblock prints of stark, stylized wheatfields that owed more to German Expressionism than to any American school. Her prints, passed hand-to-hand among teachers and librarians, shaped visual sensibilities more effectively than any curriculum could.

Three recurring themes marked these women’s contributions:

- Solitude, not as loneliness but as compositional clarity—a single figure or object isolated in space.

- Ritual labor, such as quilting, cooking, or harvesting, reimagined in formal terms.

- Interior light, especially as filtered through lace curtains, doorways, or attic windows—rendered with a near-sacred attention.

What might seem to outsiders like provincial quietude was, for these women, a radical assertion: that art did not require proximity to power, only attention.

Austerity and Abstraction

Modernist abstraction in North Dakota, when it finally broke from representation, was shaped less by formal theories than by landscape and climate. The prairie’s repetition, its vast skies, and its harsh winters encouraged a kind of visual reduction. Artists spoke not in the bold synthetics of Futurism or the riotous color of Fauvism, but in spare lines, muted tones, and restrained gestures.

A key figure in this development was Charles Beck, born in Fergus Falls but educated and professionally active in nearby Moorhead, whose woodcuts began to circulate in eastern North Dakota galleries in the 1940s and ’50s. Beck’s abstractions of barns, trees, and bluffs reduced the landscape to its geometric essence: rectangles, diagonals, arcs. His prints were austere, but never cold. They captured the discipline required by prairie life—where extravagance is not just unfashionable, but impractical.

Another important contributor was Orabel Thortvedt, who studied art in Chicago before returning to North Dakota and producing a body of work that merged Scandinavian folk motifs with minimalist design. Her paintings—of rosemaled dishes, stripped-down rural interiors, and simplified grain motifs—anticipated the graphic minimalism that would come to dominate later regional design in the 1960s.

This was not abstraction as detachment. It was abstraction born of scarcity. With limited materials, few mentors, and no nearby collectors, North Dakota modernists built visual languages from what was available: linoleum for printing, barn paint for canvases, flour sacks for textiles. Their restraint was not aesthetic poverty. It was an ethos.

Mid-century modernism in North Dakota never fully aligned with national movements. It remained too grounded, too resistant to grand theory. But it produced a uniquely local version of visual thought—clear-eyed, serious, and shaped by silence. These artists did not seek to dominate space; they sought to dwell in it with precision.

The result is a body of work still underappreciated by art historians, yet resonant with contemporary concerns. In an era newly obsessed with rural sustainability, minimalism, and slowness, these early 20th-century prairie modernists appear not as outliers, but as forerunners. Their art was made from distance, not in spite of it.

The WPA and a Government’s Palette

When the Great Depression swept across the United States, North Dakota was already well-acquainted with scarcity. The economic collapse of the 1930s only deepened the region’s sense of precarity. Drought, dust storms, and crop failures ravaged the land. Rural communities teetered on the edge of disappearance. But amid the collapse came an unlikely flowering: the Works Progress Administration (WPA), through its Federal Art Project (FAP) and related initiatives, helped seed an ambitious new vision of public art in North Dakota. For the first time, art was not a private pursuit or amateur diversion. It was a form of work—and, more importantly, a civic contribution. Through murals, sculpture, craft workshops, and community classes, the WPA helped give shape to a distinctly regional aesthetic that was both populist and modern, local and federally funded.

Muralism in Mandan and Minot

One of the most visible legacies of the WPA era in North Dakota remains in post offices, courthouses, and schools across the state: murals painted under the guidance of the Treasury Section of Fine Arts. Unlike the WPA’s Federal Art Project, which emphasized support for working artists in all media, the Treasury Section focused on integrating art into federal buildings, often through competitions that attracted artists from outside the state.

Several murals produced during this time reflect the tension between regional authenticity and imported idealism. In Mandan’s post office, for instance, artist Bernard J. Steffen painted Threshing Scene (1939), a muscular vision of agrarian life that idealizes the labor of wheat harvesting while flattening its human complexity. The figures are stylized, the composition rhythmic, and the message clear: dignity through labor, progress through unity.

A similar tone emerges in the mural Early Homesteading (1940) in the Minot post office, painted by Allen Saalburg. Here, settlers plow fields beneath a vast sky, framed by a clean horizon and sturdy architecture. The image suggests not only historical continuity but a kind of moral righteousness—a visual reinforcement of the frontier narrative.

But not all murals followed this formula. Some artists, influenced by Mexican muralists like Diego Rivera or by American social realists, brought sharper insight. In Devils Lake, WPA artist Charles Allyn tackled the subject of railroads and industrial development with a complex composition featuring workers, Indigenous figures, and the looming presence of steel tracks. Though softened by the constraints of the medium, the tension between expansion and displacement is visible in the structure of the painting itself.

These murals were more than decoration. They were part of a larger governmental effort to shape civic identity. The Depression had shattered trust in institutions. Public art, by celebrating shared history and local pride, was meant to repair that trust. And in many towns across North Dakota, it did—giving people a visual reminder that their struggles were seen, that their work mattered.

New Deal Aesthetics on the Frontier

Beyond murals, the WPA facilitated an ecosystem of artistic production previously unknown in the state. Through the Federal Art Project, dozens of artists were hired to produce prints, paintings, sculptures, and even stage designs. These were not commissions for elites. They were intended for libraries, schools, armories, and public spaces—art for everyone, made by people facing the same struggles as their neighbors.

One little-remembered figure from this era is Esther Prussing, who created a series of lithographs documenting rural life in central North Dakota. Her prints depict women canning vegetables, children walking to one-room schools, and elders gathered around radios. The technique is stark—high contrast, minimal lines—but emotionally resonant. Her work is neither nostalgic nor despairing. It is observational, clear-eyed, and imbued with quiet dignity.

Crafts were also supported under the WPA umbrella. North Dakota’s German-Russian and Scandinavian communities, long known for textile work and decorative wood carving, were encouraged to formalize their skills through workshops and exhibitions. In Bismarck, a federally funded weaving studio produced table linens and wall hangings that blended Bauhaus formalism with prairie patterns. The materials were often local—wool, flax, salvaged cotton—and the designs geometric, subdued, and repetitive, echoing the rhythms of agriculture.

The visual language of this New Deal-era art shared certain characteristics:

- Simplicity of form, influenced by both modernist abstraction and regional frugality.

- Clarity of narrative, with compositions that foregrounded work, family, and resilience.

- Earth-toned palettes, reflecting the colors of grain, dust, snow, and sky.

These were not radical aesthetics. They were moderate, grounded, and public-facing. Yet within those limits, artists managed to express complex ideas: about migration, injustice, community, and endurance.

Clay, Wood, and Wheat as Medium

Perhaps the most quietly transformative WPA legacy in North Dakota was its elevation of local materials. While painters and muralists worked with imported oils and pigments, many craftspeople turned to the things at hand: clay from riverbeds, wood from windbreaks, and wheat straw salvaged from harvests. This embrace of local materiality created a functional modernism that was both humble and formally ambitious.

Pottery studios flourished in places like Valley City and Grand Forks. Under the guidance of instructors trained in East Coast or Scandinavian ceramic traditions, local artists began producing wheel-thrown vessels, tiles, and sculptural objects. These works were typically small—meant for use—but their design ethos was sophisticated: minimal ornament, clean lines, subtle glazes. The emphasis was on process and touch, not display.

In Dickinson, a WPA-funded woodshop employed out-of-work carpenters to produce furniture for schools and public buildings. Though utilitarian, these pieces often featured carved motifs drawn from prairie flora—wild roses, wheat stalks, sunbursts—offering a regional twist on the Arts and Crafts tradition. A child’s school desk from this period might bear both the scars of use and the curve of a masterfully hand-planed edge.

Wheat itself even entered the realm of visual experimentation. In several counties, women experimented with wheat weaving, a folk art brought by German and Norwegian immigrants but modernized under WPA tutelage. The resulting objects—crosses, wreaths, wall plaques—blurred the boundary between ritual and design. Some were purely decorative; others retained their origins as harvest offerings or church ornaments. Their patterns, symmetrical and looped, evoked both ancient fertility symbols and the crisp repetition of modern graphic design.

Together, these material practices formed a distinct WPA aesthetic in North Dakota: tactile, local, democratic. Unlike the monumentalism of East Coast projects, the art of the plains WPA was human-scaled, meant to be lived with. It taught that beauty could come from scarcity, and that public investment in creativity was not a luxury but a necessity.

By the time the WPA wound down in the early 1940s, it had transformed the visual infrastructure of North Dakota. It left behind murals, prints, pottery, and a generation of artists who had learned that their work could serve not just as self-expression, but as civic contribution. In a region often characterized by survival, the New Deal’s artistic legacy suggested something more enduring: a culture that not only endures—but imagines.

Postwar Boom, Postwar Blur: 1945–1975

After World War II, North Dakota entered a period of quiet transformation. While the rest of the nation roared into a booming consumer economy and the art world turned its gaze to Abstract Expressionism in New York, the visual culture of North Dakota moved more cautiously. Yet these decades—marked by GI Bill expansion, suburbanization, university growth, and cultural ambivalence—saw a subtle reorganization of artistic life on the northern plains. What emerged was not a singular movement but a mosaic of impulses: traditionalism, amateur enthusiasm, modernist experimentation, and institutional ambition, all layered atop one another like wheatfields over buried towns.

The GI Bill’s Quiet Legacy

One of the most significant but underrecognized drivers of artistic development in postwar North Dakota was the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944—the GI Bill. While its more visible impact was on housing and education, it also brought thousands of returning veterans into university art departments, many of them with little prior exposure to formal aesthetics but a strong appetite for structure and purpose.

At institutions like the University of North Dakota (UND) in Grand Forks and North Dakota State University (NDSU) in Fargo, art programs expanded rapidly after the war. These were not avant-garde think tanks like Black Mountain College or the Bauhaus, but they were serious, well-funded, and often led by instructors trained in eastern schools or overseas. Veterans enrolled in studio classes not to become professional artists, but to explore, rebuild, and reflect. Their experiences of violence, dislocation, and uncertainty translated into art that was often somber, restrained, and formally rigorous.

In Grand Forks, artist and educator Paul Barr—a UND professor and former soldier—encouraged his students to work with oils, charcoal, and clay, often emphasizing simplicity of form over flashy technique. His own work, rooted in figuration but teetering toward abstraction, dealt with themes of memory, endurance, and inner structure. His influence can be seen in the dozens of veterans who, though they never pursued art full-time, developed distinctive bodies of work and contributed to local exhibitions, libraries, and civic collections.

Veteran artists in North Dakota were rarely self-promoting. Their creativity expressed itself through modest watercolors, woodcuts, and ceramics quietly hung in courthouse lobbies or bank foyers. The GI Bill did not spark a revolution in the state’s aesthetics, but it planted the seeds of seriousness. It suggested that art need not be flamboyant to matter.

Suburban Domesticities and Amateur Oil

The postwar years also brought dramatic demographic shifts. As North Dakota’s population consolidated in urban centers like Fargo, Bismarck, and Minot, a new kind of artmaking emerged: suburban, domestic, and largely amateur. Home oil painting kits, “how-to” books, and local evening classes created a generation of informal artists—mostly women—whose work filled basements, kitchens, and community art shows.

These works are often dismissed as hobbyist or kitsch, but they form a significant part of the state’s midcentury visual history. Landscapes, still lifes, and sentimental portraits dominated the genre, rendered with varying degrees of skill but with an unmistakable desire to preserve or beautify the familiar. The regional subjects were constant: wheat fields at dusk, deer in snow, barns lit by northern moonlight.

Fargo’s YWCA hosted weekly art gatherings in the 1950s that drew dozens of participants. These classes served not only as creative outlets but as social spaces where women could discuss life, politics, and literature. Though largely unarchived, the work produced there—some of which survives in church halls, family photo albums, or senior centers—offers a window into how modern life was internalized and reflected by those far from any art capital.

Interestingly, these amateur painters often engaged in quiet stylistic innovation. While their content remained conventional, their handling of color and form gradually incorporated modernist influence—filtered through magazine illustrations, commercial design, or traveling exhibitions. A farmhouse might be flattened into a two-color silhouette; a bouquet reduced to angular petals and shadows. Their experimentation was unconscious, but it left its mark.

Three qualities define this suburban art culture:

- Sentimentality, not in excess, but as a grounding force—home, memory, place.

- Modesty of ambition, reflected in scale, materials, and display.

- Steady absorption of formal trends, reshaped into regional idioms.

This was not art made for critics. It was art made to live with, to give as gifts, to honor the world immediately at hand.

University Galleries as Incubators

If the home was a site of informal artmaking, the university became the formal incubator for modern aesthetics in postwar North Dakota. Both UND and NDSU began investing in gallery spaces, traveling exhibitions, and visiting artist programs. These institutions served as bridges between rural conservatism and national experimentation—never entirely cutting edge, but never entirely parochial either.

At UND, the Burtness Theatre and the university’s newly formalized art gallery began showing regional painters alongside nationally recognized figures. While Abstract Expressionism never dominated here as it did on the coasts, the influence of Rothko, de Kooning, and later the Color Field painters was unmistakable. Faculty artists encouraged students to experiment with non-representational forms, often using the local landscape as a structural or emotional point of departure.

The Red River, with its sluggish motion and murky depths, became a recurring abstraction—its twists and seasonal shifts rendered in poured pigment or scraped acrylic. A 1967 exhibit titled Forms of the Prairie featured canvases with titles like Floodplain Memory and Yellow Sky, Soft Edge, reflecting a modernist approach grounded in geography. These were not urban paintings; they were postmodern without the posturing.

NDSU, with its emphasis on design and architecture, nurtured a parallel aesthetic: geometric, functional, and often industrial. Student work in the 1960s and ’70s included welded metal sculpture, minimalist textiles, and architectural maquettes that anticipated Brutalism. The materials—steel, raw concrete, fiberboard—echoed the agricultural infrastructure surrounding Fargo. Grain elevators became formal models. Silo interiors inspired installation pieces. Aesthetics of utility were turned into aesthetic statements.

Both campuses also played a curatorial role for the region. They hosted traveling shows from the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, lectures by printmakers from Wisconsin, and student exchanges with Canadian universities. Slowly, deliberately, they expanded the state’s visual vocabulary. In doing so, they reshaped its art infrastructure—not through radical rupture, but through quiet accumulation.

This institutional support proved especially vital for artists who might otherwise have gone unnoticed. One such figure was Lewis Kuka, a part-time art instructor and sculptor who created monumental but temporary land artworks along the Sheyenne River in the 1970s—using branches, snow, and salvaged metal to construct ephemeral geometries that existed for days or hours before dissolving. Though nearly undocumented, Kuka’s work anticipated both environmental art and installation long before those genres became fashionable.

Postwar art in North Dakota did not align neatly with the major movements of the time. It remained provincial in the best and most literal sense: of a province, of a place. It grappled with modernization, but without urban anxiety. It absorbed abstraction without surrendering representation. It cultivated institutions not as gatekeepers, but as greenhouses.

These decades—sometimes described as quiet, even stagnant—were in fact generative. They created a dispersed, deeply rooted ecosystem of art-making: modest in scale, experimental in form, and stubbornly attached to the land beneath it.

Reservation Renaissance: American Indian Art in the Late 20th Century

In the late 20th century, a distinct resurgence of American Indian artistic expression emerged across North Dakota’s reservations. It did not begin with a single manifesto or collective, but rather with a series of individual acts of reclamation—each one rooted in the past but unmistakably attuned to the present. This era, often overlooked in mainstream narratives of American art, was a time of intense creative activity in Standing Rock, Turtle Mountain, Fort Berthold, and Spirit Lake. Artists blended ancestral techniques with contemporary themes, reshaping the categories of traditional and modern. The result was a powerful recalibration: art no longer defined by anthropological display or colonial expectation, but by sovereignty of form, content, and purpose.

Tradition Reclaimed, Technique Reinvented

By the 1970s, the aesthetic of “authenticity” long imposed by outsiders—fetishizing the old, the handmade, the vanishing—was increasingly rejected by American Indian artists in North Dakota. Instead, they began to assert continuity as a form of resistance: not by abandoning traditional media, but by expanding their use and recontextualizing their meaning.

Beadwork, for example, remained central—but now appeared on denim jackets, canvases, and mixed-media installations. Quilled medallions were not limited to ceremonial use, but entered the gallery space as complex symbols of endurance. These shifts did not signify a break with tradition, but rather an assertion of agency over it. The artists were not reviving a lost art; they were working within an unbroken lineage, even when institutions failed to recognize it.

One pivotal figure was Denise Lajimodiere (Turtle Mountain Ojibwe), whose work in birchbark biting—a traditional Ojibwe art form nearly lost to history—gained national attention. Lajimodiere didn’t modernize the practice so much as insist that its very survival was radical. Her designs, often symmetrical and densely patterned, were made by folding a sheet of birchbark and biting it into shape with her teeth. The resulting images resembled snowflakes or mandalas, but with a bite literally embedded in the medium—a metaphor for the transmission of knowledge through embodied memory.

At Fort Berthold, Hidatsa artist Monte Yellow Bird Sr. (Black Pinto Horse) began to explore contemporary acrylic painting alongside traditional ledger-style drawing, creating visual hybrids that combined 19th-century Plains pictography with narrative abstraction. His work did not offer reconciliation or nostalgia. It was full of political tension, humor, and coded reference—challenging both non-Native expectations and internal cultural debates about identity, tradition, and innovation.

Such work was not created in isolation. Reservation high schools, tribal colleges, and community centers began to support art programs that encouraged both traditional practice and personal voice. These spaces fostered mentorship, continuity, and experimentation. They also became safe harbors for young artists navigating questions of history, violence, and visibility.

The Return of the Quill

While beadwork came to symbolize adaptability and modernity, quillwork—older, more technically demanding, and often considered endangered—experienced its own renaissance. In Turtle Mountain and Standing Rock, a new generation of artists took up porcupine quill embroidery not as an artifact of the past, but as a living discipline.

Quillwork requires patience and intimacy. Quills must be collected, cleaned, dyed, softened, and flattened—often by mouth—before being wrapped, stitched, or woven into leather or cloth. Each piece carries the trace of the maker’s breath and body. In the hands of artists like JoJo McLaughlin (Turtle Mountain), quillwork became a site of both meditative repetition and political intensity.

McLaughlin’s quilled vests, moccasins, and wall pieces often drew from old geometric patterns but recombined them in unexpected ways—turning medicine wheels into spirals, teepee motifs into layered polygons. Her work refused categorization: too formal for “craft,” too tactile for conceptual art. It demanded to be judged on its own terms.

Three characteristics marked the return of quillwork in this period:

- Radical patience, as a counterpoint to the rapid consumption of digital culture.

- Re-mapping of tradition, where older motifs were transformed rather than merely preserved.

- Material symbolism, with the quills themselves signifying survival, pain, and resilience.

In a time of growing disconnection from land and custom, these works reasserted presence—not in slogans, but in stitches.

This return was not limited to individual artists. Institutions began to respond. The Plains Art Museum in Fargo, long focused on settler art, began collecting and exhibiting contemporary American Indian work. Tribal colleges hosted exhibitions and artist talks, and inter-tribal arts festivals gained prominence as spaces of visibility and exchange. Still, the majority of work remained rooted in place—circulating within community, family, and ceremony, often outside the traditional market system.

Redefining “Contemporary”

Perhaps the most powerful shift in this late 20th-century period was the collapse of binary thinking: traditional vs. modern, craft vs. art, sacred vs. secular. Artists began to dismantle those distinctions, creating works that could simultaneously speak to the past and to the urgencies of the present. “Contemporary Native art” was not a category of departure from tradition—it was an extension of it, redefined on the artist’s own terms.

This redefinition often involved confronting history directly. At Standing Rock, painter and performance artist Avis Charley (Spirit Lake/Diné) produced figurative works that combined pin-up style portraiture with traditional regalia. Her portraits of Native women—strong, sensual, often defiant—subverted centuries of colonial imagery while reclaiming visual space for Indigenous femininity.

At Turtle Mountain, the artist collective Tatanka Artists Circle emerged as an informal but influential network. Their members—working in spray paint, pen and ink, digital design, and installation—reimagined star quilts as pixel art, reinterpreted creation stories as comics, and used graffiti lettering to spell out Anishinaabe words on abandoned buildings. Their work was ephemeral, collaborative, and defiantly public.

This era also saw the introduction of video, spoken word, and interdisciplinary practice. Artists like Wanda Nanibush (though based in Canada) influenced North Dakotan peers by modeling an Indigenous curatorial vision that rejected objectification in favor of narrative, context, and voice.

What defined this reservation renaissance was not a specific style, but a shared refusal: a refusal to be frozen in time. American Indian artists in late 20th-century North Dakota insisted that tradition is not static. It evolves, absorbs, challenges, and survives.

Their art was not made to decorate institutions that once tried to erase them. It was made to remember, resist, and renew.

The Art of Place: Landscape, Sky, Silence

To outsiders, North Dakota often registers visually as a void. A horizon that never breaks. A sky too vast to anchor. A silence mistaken for absence. But to the artists who have worked, lived, and walked this terrain, these elements are not voids at all—they are the essence of the place. They shape not only the content of art in North Dakota, but its structure, rhythm, and mood. Across media and generations, from painters to photographers, from sculptors to poets, the landscape has exerted a quiet but implacable gravitational pull. Not in the form of picturesque sublimity, but as a condition of existence. This is art shaped by space, by exposure, by the sublime indifference of open land.

The Aesthetic of Distance

To create art in North Dakota is, inevitably, to contend with distance. Physical, yes—between farms, towns, even neighbors. But also psychic distance: the kind that emerges from long winters, low population density, and the internal calibration required to live far from the country’s cultural nerve centers.

This distance is not an obstacle. It is material.

Photographers like Wayne Gudmundson, who began documenting the northern plains in the 1970s and ’80s, turned this very stillness into composition. His black-and-white images—weathered Lutheran churches, abandoned grain elevators, telephone poles leaning into sky—rarely feature people, but hum with presence. He once described his aesthetic as “North Dakota Gothic,” but the mood is less dramatic than devotional: a reverent record of decay, built with light and shadow.

The painter Susan Morrissey (Bismarck-based) explored similar themes in her minimalist landscapes. Working in thin oils on board, she created horizontal bands of prairie color: ochre, slate, ice blue, soft green. Her skies were not backdrops but protagonists—pressing down, stretching wide. She said little about her work, insisting that “the place explains itself if you just stop adding to it.”

This anti-baroque impulse—an aversion to overstatement, to flourish, to noise—runs deep in the state’s visual culture. It emerges not only in landscapes but in abstraction, in ceramics, in fiber art. A logic of restraint prevails: not due to poverty of means, but to fidelity of vision. The land itself enforces a kind of humility.

Three recurring elements define this landscape-bound aesthetic:

- Horizon lines, either central or low, anchoring compositions in the reality of flatness.

- Muted palettes, echoing the pale tonalities of snow, wheat, dust, and overcast sky.

- Negative space, used not as filler but as presence—what remains unsaid, or untouched.

This art does not demand your attention. It waits. If you are in a hurry, you will miss it.

Artists and the North Dakota Horizon

There is something elemental about the horizon in North Dakota. It shapes not just what one sees, but how one imagines. For artists, it becomes both a compositional device and a psychological register. It organizes vision.

Painter James Rosenquist, though born in Grand Forks and raised in nearby Mekinock, left the state early to become a central figure in New York Pop Art. Yet traces of the North Dakota horizon remained in his massive, billboard-scale canvases: layered bands of color, fragmented skies, disjunctive expanses. In interviews, Rosenquist often credited his early years painting signs on barns and silos with shaping his understanding of scale and fragmentation. Even in his most frenetic New York work, there is an underlying structure that feels born of empty land.

Other artists, like the late Rolfe Mandan, never left the state, and made the horizon their central motif. Mandan’s late-career series Lines of Departure consists of 12 nearly identical canvases, each divided horizontally into two uneven bands: one for earth, one for sky. The colors shift—snow, harvest, dusk—but the form remains. These were not paintings of specific places, but meditations on seeing itself. The horizon becomes mantra.

Even in sculpture, the horizon exerts force. Artist Sarah Beauchamp, working out of a former grain shed near Rugby, creates site-specific installations that use mirror, light, and weather to echo the boundary between ground and sky. Her 2004 piece Dissolve Line consisted of a narrow aluminum ribbon stretched along a rise in the prairie. From a distance, it looked like the horizon had cracked. Then shimmered. Then healed.

Such works resist narrative. They do not tell stories. They offer conditions. Weather, duration, stillness. They ask the viewer not to interpret, but to endure with them.

Silence as Subject

More than any one image or technique, it is silence that defines the best of North Dakota’s art. A silence not of absence, but of attention. It manifests not only in subject matter—abandoned towns, winter fields, empty churches—but in rhythm, in palette, in structure. It is a silence born of listening.

Poet and visual artist Louise Erdrich (Turtle Mountain Chippewa), though better known for her novels, has produced a body of visual work that embodies this kind of silence. Her small monotypes—intimate, moody, monochrome—often incorporate fragments of text or natural forms (leaves, bones, seeds) against blank backgrounds. The effect is meditative, like a whispered sentence left unfinished. These are works that do not explain themselves. They invite.

Similarly, the silkscreen artist Thomas Red Owl Haukaas (Lakota), who exhibited in the region in the 1990s, often used negative space to convey communal memory. In one print, a single rider moves across a blank field; in another, a line of dancers emerges from white fog. The silence here is not peaceful. It is historical. It speaks of erasure, endurance, and the cost of survival.

This aesthetic of quiet can also be found in more conceptual work. Installation artist Dale Lamphere’s Arc of Heaven (1996), though located just over the state line in South Dakota, has been exhibited and referenced widely in North Dakota. It features a polished metal arc positioned to reflect sky and land equally—a bridge of reflection. Standing beneath it, the viewer sees not the sculpture, but themselves, suspended in sky. It is not a monument. It is an interruption in silence, that still deepens silence.

North Dakota’s art, when it succeeds most deeply, does not try to overpower its place. It listens to it. And in that listening, it begins to see. The land is not empty, the sky is not blank, and silence is not void. Each is a form of presence. Each demands patience.

This is not the romanticism of untouched wilderness. It is the realism of distance: where meaning is not declared, but revealed—slowly, if you stay long enough.

Institutions and Interventions: Museums, Universities, and Collectives

If North Dakota’s artistic identity has often been shaped by solitude and individual endurance, it has also depended—quietly but critically—on institutions. Museums, universities, artist collectives, and public arts programs have played a decisive role in the development, preservation, and promotion of visual art across the state. These institutions, far from being mere repositories, have functioned as active agents: curating regional narratives, importing outside influences, and offering platforms for local expression. The result is a layered ecology of art support—one that bridges the divide between grassroots creativity and professional exhibition, between rural constraint and cosmopolitan ambition.

The Plains Art Museum and Its Predecessors

At the center of this institutional landscape stands the Plains Art Museum, located in Fargo and widely considered North Dakota’s premier art institution. Its history, however, is not one of easy prestige. The museum began modestly as the Red River Art Center in the 1960s, housed in a former post office and run largely by volunteers. Its early exhibitions were modest in scale—regional landscapes, student shows, and traveling collections—but the space quickly became a vital gathering point for the area’s artists and patrons.

In 1997, the museum relocated to a renovated warehouse in downtown Fargo and rebranded as the Plains Art Museum, reflecting a broader ambition: to serve not only Fargo but the entire Northern Plains region, including western Minnesota, South Dakota, and parts of Manitoba. This move allowed the institution to dramatically expand its programming, educational outreach, and curatorial scope. With its industrial brick walls and vaulted ceilings, the new space conveyed seriousness—but also continuity with the region’s architectural and economic history.

The Plains Art Museum’s impact has rested not just on its exhibitions, but on its collection philosophy. Unlike many regional museums that prioritize European or coastal American art, Plains has consistently collected and exhibited work by American Indian artists, rural modernists, and Midwestern experimentalists. Their “Rolling Plains Art Gallery,” a mobile truck that brought artwork to small towns across the state, was one of the most effective outreach tools of its time—transforming grain elevators and gymnasiums into pop-up galleries for those otherwise cut off from cultural infrastructure.

Notable exhibitions include Dakota Modern: The Art of Oscar Howe, which toured nationally and featured the groundbreaking Yanktonai Dakota painter who redefined what Native American painting could be; and Art on the Plains, a recurring juried exhibition showcasing contemporary artists from across the region, with no stylistic limitations. These shows have placed the museum at the nexus of tradition and experiment, place and reinvention.

UND and NDSU: Parallel Currents

While Fargo’s Plains Museum has shaped public visibility, North Dakota’s two major universities—the University of North Dakota (UND) in Grand Forks and North Dakota State University (NDSU) in Fargo—have functioned as twin engines of artistic development. Their roles have not always been synchronized, but together they’ve cultivated a generation of working artists, educators, curators, and designers.

UND has long been home to a robust studio arts program, with particular strength in ceramics, printmaking, and painting. The school’s legacy is in part due to the influence of Margaret Kelly Cable, a pioneering figure in American ceramics who led UND’s ceramic department in the early 20th century. Her emphasis on form, function, and local materials seeded a regional philosophy of making that endures in the department’s ethos. The North Dakota Museum of Art, located on UND’s campus, continues this legacy. Directed for many years by Laurel Reuter, the museum is known for its elegant and provocative exhibitions that blend regional content with international concerns.

Reuter’s curatorial vision elevated the museum beyond its expected reach. Exhibitions like Singing Our History, which paired American Indian artists with historical artifacts, or Air, Land, Seed, which focused on environmental anxiety in agricultural regions, placed North Dakota at the center of urgent global conversations. In a place often seen as peripheral, the museum insisted on relevance.

NDSU, meanwhile, has cultivated a different but complementary focus—emphasizing design, architecture, and interdisciplinary visual practice. Its programs in landscape architecture and environmental design frequently intersect with art-making, resulting in works that merge visual aesthetics with spatial planning. Installations and public art projects sponsored by NDSU faculty and alumni have reimagined Fargo’s built environment—not as a backdrop, but as a malleable canvas.

One such project, the ephemeral Red River Light Grid (2014), designed by a team of faculty and students, temporarily illuminated the riverbanks with motion-triggered lights that responded to pedestrian traffic and wind speed. Though temporary, the installation suggested what art might become when not confined to canvas or gallery—responsive, spatial, ecological.

These universities have also supported publishing, archival work, and artist residencies, often in collaboration with other institutions. Their alumni have seeded art programs in high schools and community colleges across the state, ensuring continuity and regional fluency.

Artist-Run Spaces in Fargo and Beyond

Beyond institutions of formal authority, North Dakota has long nurtured a quieter network of artist-run spaces and collectives. These spaces—often temporary, itinerant, or informally structured—serve a different function: experimentation, risk, immediacy. If museums and universities provide continuity, collectives provide rupture.

Fargo’s Rourke Art Gallery and Museum, founded by artist James O’Rourke, has been a consistent site of both tradition and transgression. Located in Moorhead, Minnesota, just across the Red River, it has shown everything from Russian icons to erotic woodcuts to minimalist sculpture. O’Rourke’s curation has often been idiosyncratic, but always passionate—and his gallery has acted as a pressure valve, allowing for dissent from institutional norms.

In Bismarck, collectives like Midwest Art Conservancy and Dakota Gallery Space have emerged periodically, often in response to local needs. These pop-up shows—sometimes hosted in empty storefronts, barns, or public parks—have allowed young artists to test new formats: video art, performance, relational aesthetics. They are less about permanence than pulse. A weekend show might draw 30 people and still reshape a young artist’s trajectory.

Even more ephemeral are the reservation-based collectives and gatherings. At Spirit Lake and Fort Berthold, family-organized shows and seasonal exhibits have formed a kind of shadow network—operating outside the non-profit model, grounded in kinship and occasion. These events often blend craft, food, music, and ceremony. They are not just about showcasing art; they are about sustaining the conditions for it.

Three characteristics define these artist-run efforts:

- Local adaptability, responding to space, community, and available materials.