The first artists of Mississippi worked in earth, clay, shell, and stone long before a brush ever met pigment. Across the river plains and wooded ridges, their art was not decoration but cosmology made visible: a shaping of the physical world to mirror an unseen order. Mounds rose like measured hills, vessels gleamed with the sheen of burnished clay, and carved figures merged animal and human traits in gestures of reverence and transformation.

Earth as Canvas

The Mississippian mound builders, active from roughly 800 AD until the early contact era, treated landscape itself as sculpture. Their great earthen platforms at Winterville, Emerald, and other sites within present-day Mississippi were not isolated works but coordinated designs—earth, geometry, and ritual fused. Each mound’s orientation corresponded to the sun’s movement or the river’s flow, binding human ceremony to seasonal rhythm. In this geometry lay the earliest Mississippi aesthetic: form disciplined by belief.

Archaeologists studying Winterville’s stratified layers have found subtle color gradations in the clay fill—bands of red, gray, and buff—suggesting that builders sought visual harmony as well as stability. Fragments of pottery unearthed nearby bear repeating triangular and spiral motifs, traces of a shared visual vocabulary extending far beyond the delta. What began as utilitarian architecture became, in effect, Mississippi’s first monumental art tradition.

Clay, Fire, and Pattern

Pottery was the portable counterpart to those monumental earthworks. In the central and southern regions, Coles Creek and Plaquemine artisans developed fine coil-building methods that produced remarkably thin, even walls. Surfaces were smoothed to a soft gleam, catching the oblique light of evening fires. Many pieces show deliberate asymmetry—a slight tilt of the rim, a swelling in the body—that gives them a sense of motion absent from purely functional ware.

Each pot was also a test of judgment. Clay from the riverbank was mixed with ground shell to temper it against cracking; firing demanded a precise balance of oxygen and smoke. Potters read the flame’s color as carefully as later painters would study tone and hue. Successful vessels embodied a sequence of invisible decisions: selection, shaping, drying, firing. They were the first Mississippi artworks to record the artist’s hand in every step of their making.

The Choctaw and Continuity of Craft

By the seventeenth century, the Choctaw dominated much of what is now Mississippi, carrying forward many Mississippian traditions while adapting them to new rhythms of life. Their pottery often displayed incised crosshatching and punctated rims—echoes of ancient symbols reduced to spare, balanced marks. Clay was gathered only from designated sites, and potters customarily offered words of thanks before removing it, acknowledging the material’s living quality.

Choctaw craft extended far beyond ceramics. Carved spoons, woven sashes, and painted drums all reveal an instinct for pattern within utility. Color held moral and spiritual significance—red for life, black for the unknown, yellow for balance. Such codes gave ordinary objects a ceremonial presence. The notion that art could dwell in use, that beauty and function were never separate, remained central to Mississippi’s later folk traditions.

Stone Effigies and the Human Image

The Mississippian and early Choctaw sculptors occasionally turned to stone, creating effigies that compress physical form into dense, meditative masses. One small kneeling figure, now held by the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, shows a man clasping his knees, eyes narrowed in contemplation. The sculptor balanced realism with abstraction: limbs simplified to planes, the face stylized yet introspective. It is less a portrait than a study in spiritual concentration.

Other effigies merge human and animal aspects—a bird-headed dancer, a serpent-bodied man—expressing belief in transformation rather than division between species. These images imply a world without fixed boundaries, where identity could shift between forms. Later generations of artists, from coastal potters to twentieth-century painters, would return unconsciously to that same idea: the mutable self shaped by environment and ritual.

Symbols in Motion

Decorative patterns from early Mississippi art show remarkable dynamism. Spiral motifs evoke water currents; zigzags trace lightning; nested triangles echo the movement of flight. When arranged in bands around a vessel or shell gorget, they create optical rhythms not unlike those of modern design. The same pattern might appear carved in wood, incised in clay, and painted on skin, revealing an aesthetic system that transcended medium.

Some scholars see in these motifs a form of proto-writing, a way to record narratives or genealogies through recurring signs. Whether or not that is true, the visual logic remains compelling: repetition as remembrance, pattern as history. Mississippi’s first artists taught later ones that rhythm itself can carry meaning.

Trade, Exchange, and Influence

Mississippi’s rivers carried more than silt; they moved ideas. Shell from the Gulf coast reached inland villages, copper from the Great Lakes arrived through networks of barter, and certain design motifs appear simultaneously in distant regions. The state’s earliest art history is therefore also a history of communication. Every pot, pendant, and effigy bore traces of a wider world.

Archaeological evidence shows that artisans along the Natchez Bluffs incorporated foreign materials into local styles, transforming them in the process. A fragment of copper embossed with avian shapes found near Port Gibson, for example, adapts northern imagery to southern curvature and proportion. Even in precontact centuries, Mississippi artists were not provincial but dialogic, shaping a regional identity from borrowed forms.

Rediscovery and Silence

By the time European settlers arrived in the eighteenth century, much of this art had already weathered into anonymity. Fields plowed over mounds; rivers shifted and swallowed villages. Antiquarians of the nineteenth century collected artifacts without context, stripping them of meaning while preserving their surfaces. Yet the objects themselves persisted—mute teachers, waiting for rediscovery.

Modern scholarship, particularly from the mid-twentieth century onward, began to reassemble this fractured picture. Excavations at Winterville, Holly Bluff, and other sites have confirmed the sophistication of Mississippi’s early aesthetic systems. Museums now treat these works not as curiosities but as the foundation of a continuous visual lineage. The state’s art history does not begin with European oil painting; it begins with earth, pattern, and fire.

Enduring Foundations

The influence of these ancient makers extends quietly through Mississippi’s later art. Folk potters of the hill country, the visionary builders of yard shrines, and even modern painters of the Delta inherit an instinct for material truth and rhythmic order that originated in those first ceremonial mounds. Each new generation, knowingly or not, repeats a gesture first made with river clay a thousand years ago.

To walk among the remaining mounds today is to feel the persistence of that gesture—the sense that art, in Mississippi, has always been a way of shaping the land to mirror the spirit. The hum of insects, the curve of the riverbank, the burnished surface of a pot: all bear witness to a lineage of making that endures beyond memory.

Colonial Encounters and Early European Influence

When European ships reached the lower Mississippi Valley, they brought not only weapons and trade goods but new visual languages. What met them was a land already marked by centuries of art—mounds and pottery that spoke in geometry rather than alphabet. The meeting of these worlds produced a hybrid aesthetic in which European technique collided with Native pattern, and the landscape itself became a stage for competing visions of order and devotion.

Maps, Missions, and Early Impressions

The first European images of Mississippi were not paintings but maps. French cartographers such as Guillaume de L’Isle and later the Jesuit chroniclers drew the river as a sinuous ribbon, its tributaries flowering like branches of a sacred tree. These maps, while scientific in intent, also served as imaginative portraits of possession: the curve of a bayou rendered in ink signified control as surely as a fort.

Missionaries followed cartographers, bringing with them portable icons, small carved crucifixes, and illustrated catechisms. These objects, carried upriver to settlements and trading posts, introduced new materials—pigments, gilding, and paper—and the notion that images could teach doctrine. Yet even these imported artworks began to absorb local color. Tempera paints mixed with river clay, and crosses were carved from cypress rather than oak, giving them the texture and tone of the Mississippi landscape.

The French Period and Visual Order

French colonial art in the region favored practical beauty. Decorative ironwork, embroidery, and architectural ornament reflected the tastes of settlers from New Orleans who extended their influence northward along the river. Early houses in Natchez and Biloxi displayed painted panels with floral borders and religious motifs, modest echoes of Rococo ornament filtered through frontier necessity.

In ecclesiastical settings, however, ambition grew bolder. The Jesuit missions built modest chapels adorned with painted altarpieces on wooden boards. One surviving example, a fragmentary depiction of the Virgin once housed near Pascagoula, reveals a confident hand translating European composition into provincial idiom. The brushwork is coarse, the pigments limited, yet the arrangement—figures framed by curling vines and radiant clouds—shows how quickly European models took root in local soil.

Spanish and British Overlays

When France lost control of the territory in the eighteenth century, Spanish administrators arrived with their own aesthetic preferences. Spanish baroque sensibilities introduced deeper color and sculptural texture, seen in small devotional statues and silverwork imported through Havana. Natchez, under Spanish rule, saw the brief flowering of religious processions and public altars that added theatricality to frontier piety.

The later British interlude brought a cooler visual tone. Portraiture and scientific illustration replaced iconography. British surveyors sketched river bluffs and botanical specimens with the disciplined line of Enlightenment empiricism. These drawings, often made by military engineers, capture Mississippi as specimen rather than shrine: a landscape to be measured, cataloged, and, ultimately, governed.

Domestic Craft and Adaptation

Away from the colonial centers, settlers and enslaved craftspeople shaped their own decorative vocabularies. Furniture built in the Natchez district combined English joinery with French curvature; painted chests bore tulip and vine motifs reminiscent of both European folk art and local Choctaw patterns. Women embroidered linens with simplified heraldic emblems, while enslaved artisans adapted European carpentry to native woods like magnolia and oak.

Three forms became especially emblematic of frontier artistry:

- Painted furniture panels, where bright pigments stood in for costly veneers.

- Ceramic tableware fired in crude kilns, imitating European shapes but retaining hand-built irregularity.

- Metalwork and silver repairs, often executed by enslaved blacksmiths who merged African tool sensibility with European formality.

These objects rarely survive intact, yet documentary inventories and scattered examples confirm a culture of improvisation—beauty coaxed from scarcity.

Portraiture in a Frontier World

As settlements matured, portraiture emerged as the first major fine-art genre in Mississippi. Traveling artists offered likenesses to wealthy planters and military officers, charging by size and background complexity. Works by itinerant painters such as José Narciso Barberan in the late eighteenth century record faces stiffly posed against imagined drapery and column. Technique lagged behind ambition, but even the clumsy execution signals the colonists’ hunger for visual permanence.

What distinguishes these portraits is their negotiation between identity and place. Sitters are arrayed in European costume, yet behind them stretch hazy river bluffs and forests—signs of a landscape not yet tamed. The tension between refinement and wilderness would persist throughout Mississippi’s artistic evolution, resurfacing centuries later in both painting and photography.

Religious Art and the Language of Faith

Church art in colonial Mississippi was modest but conceptually rich. Crucifixes, rosaries, and painted banners accompanied processions marking feast days along the Gulf Coast. Priests often commissioned local craftsmen to produce devotional figures using available materials—pine, clay, even plaster mixed with crushed oyster shell.

These early religious artworks fused cultures in subtle ways. The drapery folds on a wooden saint might follow a Spanish model, but the saint’s face bore the rounded features familiar in Native carving. Candlesticks forged by black artisans blended European scrolls with rhythmic hammer marks recalling African design. Thus, the sacred imagery of Catholic Europe gradually absorbed the tactile, local language of Mississippi’s mixed population.

The Landscape as Image

By the late eighteenth century, maps and portraits gave way to a new fascination: the landscape itself as subject. British naturalists such as Philip Pitman and later early American surveyors began sketching vistas of the Mississippi River for scientific and patriotic purposes. Their works—pencil outlines, ink washes—are the first visual documents to treat the river not merely as boundary but as aesthetic spectacle.

These early landscapes introduced motifs that would dominate Mississippi art for centuries: the contrast between turbulent water and placid shore, the horizontal pull of the river against the vertical thrust of cypress trunks, the drama of light in humid air. Even in their scientific restraint, these drawings hint at reverence—the sense that the land itself was performing before the eye.

Cross-Cultural Ornament

Trade among Native peoples, Africans, and Europeans produced hybrid ornamentation visible in textiles and beadwork. Choctaw women incorporated imported glass beads into traditional sashes, creating color patterns that mirrored European embroidery while retaining indigenous rhythm. Enslaved artisans in coastal settlements fashioned jewelry from shells and copper scraps, combining African talismanic logic with colonial forms.

Such artifacts rarely appear in museum galleries, yet they hold the key to Mississippi’s visual synthesis. Each one, however humble, represents a negotiation of style and meaning: a new aesthetic grammar formed in contact and constraint. Through them, the colonial period emerges not as a rupture from earlier art but as a transformation of it—pattern turned into ornament, ritual into craft.

Echoes and Legacies

By the dawn of the nineteenth century, Mississippi’s visual landscape bore the marks of every hand that had touched it: Native, French, Spanish, British, and African. Architecture carried European geometry softened by local materials; household crafts fused utility with memory. The colony had become an unwitting workshop of adaptation, setting the stage for the complex art to follow.

To look back on these centuries is to see more than conquest or survival. It is to witness the slow formation of a regional eye—one that learned to translate foreign styles into the texture of river mud, pine resin, and humid light. From the first maps to the earliest portraits, Mississippi’s colonial art defined a truth that endures: in this place, art was never imported whole; it was absorbed, altered, and made to breathe the air of the delta.

The Antebellum Era and the Art of a Divided Land

Before the Civil War, Mississippi’s artistic life grew out of wealth, isolation, and unease. Portrait painters traveled muddy roads from plantation to plantation, recording faces that would soon vanish into myth. Landscapes idealized a countryside that was already fracturing beneath its own prosperity. The arts flourished under a veneer of gentility, yet the moral and material tensions of slavery haunted every canvas, carving, and architectural flourish.

Portraiture and the Performance of Refinement

In the early nineteenth century, portraiture became the primary expression of status among Mississippi’s planter elite. Wealth derived from cotton and enslaved labor found its visual mirror in oil paintings that sought to emulate European grace. Artists such as John Antrobus and Robert Walter Weir visited the region, while itinerant local painters filled the demand for likenesses in Natchez and Vicksburg.

The portraits share a peculiar mix of grandeur and unease. Men pose with books or pistols, women cradle children amid draped curtains, yet backgrounds often dissolve into mist—symbols of both ownership and impermanence. The brushwork, though often provincial, captures a world trying to convince itself of permanence in a volatile land.

Architecture as Social Image

Architecture served the same impulse. Greek Revival mansions rose along the river bluffs, their columns echoing temples of democracy while sheltering an economy of bondage. Builders adapted classical ideals to local materials—cypress, heart pine, and brick fired from river clay. The resulting structures, such as Stanton Hall and Monmouth in Natchez, were visual arguments for order amid a chaotic frontier.

Interior decoration followed European pattern books. Frescoed ceilings, imported wallpaper, and painted trompe-l’œil panels turned drawing rooms into theatrical spaces of self-presentation. Every cornice and frieze projected cultivation, yet beneath the ornament lay the brutal arithmetic of the cotton ledger.

The Landscape Ideal

Landscape painting during this period reflected both pride and distance. Artists rendered the Delta’s broad horizons and oak-lined roads as pastoral scenes of abundance. Yet few of these images depict labor; the land appears miraculously self-tending, as if prosperity required no human cost.

Traveling painters such as William Dunlap—born in Mississippi in 1796 but trained in the Northeast—returned occasionally to paint river scenes that joined local topography to national romanticism. His Mississippi landscapes, though limited in number, helped shape how the region imagined itself: fertile, mysterious, and apart.

Craft and the Hidden Hands

While plantation art celebrated ownership, another artistic life thrived in quarters, kitchens, and small workshops. Enslaved artisans built furniture, carved mantels, and forged decorative ironwork that adorned the very houses where they could not claim freedom. Their skill shaped the state’s material beauty while their names went unrecorded.

Three crafts in particular bore their imprint:

- Woodcarving, from architectural ornament to handmade musical instruments.

- Quilting and textile design, where geometric patterns carried both aesthetic and symbolic resonance.

- Metalwork, from wrought-iron gates to functional tools refined into art through precision and rhythm.

These works formed a shadow archive of Mississippi’s antebellum artistry—anonymous, functional, yet aesthetically decisive.

Photography and the Emerging Modern Eye

By the 1840s, photography reached Mississippi through traveling daguerreotypists. Small studios opened in towns like Natchez and Jackson, offering portraits for a fraction of a painted commission. The daguerreotype’s silvered surface captured faces with unsettling honesty, stripping away the flattery of oil paint.

For the first time, enslaved individuals also appeared in recorded images—sometimes as subjects in family portraits of their owners, sometimes independently through the rare sympathy of photographers. These early photographs, fragile and haunting, constitute Mississippi’s first documentary art form: reality catching up with artifice.

Still Life and Domestic Painting

Beyond portraiture, a quieter current of still life and decorative painting emerged in domestic spaces. Women, often educated at finishing schools or convent academies, produced floral compositions and fruit studies in watercolor or pastel. These works rarely entered public view but reveal an intimate counterpart to the grand public image of plantation life.

The emphasis on transience—wilting flowers, ripening fruit—suggests an unspoken awareness of fragility. In contrast to the monumental portraits of men and mansions, these small paintings offer introspection: a recognition that beauty, like the society producing it, could not last.

Public Monuments and Memory in Formation

By the 1850s, Mississippi communities began erecting public monuments to political figures and war heroes of earlier conflicts. These works—often marble busts or obelisks imported from northern workshops—introduced the idea of collective visual memory.

Such monuments, modest compared to later Confederate memorials, reveal the early stirrings of a civic art consciousness. They signaled the desire to mark public space with meaning, to fix identity in stone. Yet the figures commemorated—governors, soldiers, explorers—belonged to a narrative already narrowing around race and hierarchy.

The Arts of Resistance and Reticence

Alongside the visible arts of privilege ran quieter traditions of endurance. Enslaved musicians adapted African rhythms to the banjo and fiddle, giving rise to melodies that would echo in later blues and gospel. Pottery made by enslaved craftsmen in the state’s hill country, though often unsigned, carried distinct styles—slightly flared rims, incised markings—that scholars now trace as early regional schools.

These expressions rarely claimed the name “art” at the time, yet they carried forward Mississippi’s most persistent artistic virtues: improvisation, rhythm, and the transformation of constraint into form. They represent not reaction but creation under pressure.

Tension and Transition

On the eve of the Civil War, Mississippi’s visual world stood at a strange equilibrium. Wealth fueled refinement, but unease shadowed it. The same artists who painted portraits of prosperity would soon document ruin. The state’s art institutions—still informal, reliant on private patronage—hung in suspension between provincial imitation and genuine regional voice.

That tension proved defining. Mississippi’s antebellum art was not merely decorative; it was prophetic. Beneath the polished surfaces of portraits and columns lay the anxiety that all could vanish overnight. The war would make that prophecy literal, scattering artists, destroying collections, and turning the landscape itself into subject and witness.

Echoes Across Time

To study these works now is to glimpse both arrogance and vulnerability. The planters’ portraits, the iron gates they commissioned, and the uncredited crafts of enslaved hands form a single tableau of contradiction. Beauty served power, yet beauty also recorded its limits.

When the cannons fell silent, Mississippi’s artistic inheritance would not be its mansions or imported oils, but the craft traditions and material intelligence that had always run beneath them. Out of division and decay, a new art would emerge—humble, local, and enduring—just as clay endures when fire passes through it.

Reconstruction and Regional Expression

After the Civil War, Mississippi lay in physical and psychological ruin. The plantations that had once displayed portraits and sculpture were burned or abandoned; the artists who had served the planter class fled, adapted, or vanished. Yet from the wreckage arose new forms of expression that sought to make sense of loss, memory, and survival. The state’s visual culture during Reconstruction was not merely about rebuilding—it was about redefining what counted as art in a world stripped of grandeur.

Art in the Aftermath

The first years following surrender saw little organized artistic activity. Painters turned to portrait restoration, repairing damaged canvases salvaged from ruined homes. Some itinerant artists offered to repaint faces lost to fire or mildew, piecing together memory with brush and guesswork. These small acts of repair became metaphors for a society attempting to reconstruct itself through fragments.

At the same time, photography assumed new importance. Carte-de-visite portraits and mourning images proliferated as families sought to document absence. The sharp clarity of the photographic plate suited an age preoccupied with proof—proof of survival, proof of lineage, proof that anything enduring remained at all.

Architecture and the Grammar of Recovery

In towns such as Vicksburg and Natchez, architecture became the most visible sign of recovery. Builders reused bricks from ruined houses and timber from dismantled barns. The Greek Revival mansions of the antebellum era gave way to simpler Italianate and Gothic Revival forms, less boastful and more vertical, suggesting aspiration rather than possession.

Public buildings mirrored this modesty. Courthouses and churches constructed in the 1870s favored restraint over opulence. Windows grew taller, ornament lighter. These changes marked a quiet aesthetic shift: Mississippi’s art was learning humility without losing dignity.

Craft Traditions Reclaimed

While formal art struggled, craft traditions quietly flourished. Freedmen and women carried forward skills learned under bondage—carpentry, quilting, pottery, metalwork—transforming them into independent livelihoods. The quilts of rural households, assembled from scraps of worn clothing, became repositories of color and pattern rivaling any painted canvas.

Pottery centers in north Mississippi revived, producing utilitarian wares that occasionally achieved sculptural grace. Makers such as the McCarty family, later renowned in the twentieth century, traced their lineage to these humble beginnings. Clay once shaped in bondage now formed vessels for free households, a subtle yet profound redefinition of authorship.

Public Monuments and the Politics of Memory

The 1870s introduced a new art form to Mississippi: the public monument. Communities erected statues and obelisks commemorating both Confederate and Union dead, though the former would come to dominate. The earliest examples were locally carved from limestone or marble, their roughness belying the complexity of their purpose.

These monuments were less about artistry than about public identity. They transformed town squares into stages for collective remembrance. Yet their imagery—soldiers at rest, angels of victory—revealed the persistence of a romantic language even in defeat. Through sculpture, Mississippi began to rewrite its past in stone.

Photography as Witness

The camera became Reconstruction’s most articulate observer. Photographers such as J. L. Clements in Jackson documented not only portraits but the ruined streets and rebuilding efforts of towns. Albumen prints of collapsed bridges and shattered courthouses circulated through local newspapers, establishing a visual record of devastation and renewal.

Among freed communities, photography assumed a different meaning. Studio portraits of African American families in newly purchased suits and dresses stood as declarations of self-possession. Against the background of social chaos, these images formed a quiet assertion of dignity—the art of being seen as free.

Education and the Return of Training

Reconstruction also brought new opportunities for artistic education. Mission schools and normal colleges established art departments emphasizing drawing, perspective, and design. Though limited in resources, these programs introduced hundreds of students—white and black—to the fundamentals of visual expression.

At Tougaloo College, founded in 1869, drawing was taught as both skill and discipline, a language of order in a society emerging from disorder. Sketches from these classrooms survive in archives: pencil renderings of plaster busts and geometric forms, exercises that mark the beginning of a professional art culture in Mississippi.

The Rural Imagination

Outside towns, artists of modest means began recording the daily life of recovery. Folk painters depicted riverboats, cabins, and cornfields with a naive precision that turned observation into storytelling. These works, often unsigned, occupy the gray space between art and document.

In quilting circles and small churches, decoration took on communal energy. Painted banners for revivals and fairs introduced color back into public life. Even hand-painted signs for stores and steamboats carried a sense of local pride, proof that creativity persisted wherever survival did.

The Persistence of Silence

Yet much of Mississippi’s Reconstruction art speaks through absence. Few major paintings or sculptures survive from the 1860s and 1870s; many artists lacked both patronage and materials. What endures is a sense of restraint—the stripped interiors, the plain facades, the careful handwriting in sketchbooks. The state’s aesthetic became one of economy and endurance rather than display.

That silence would prove formative. It forced later generations to build not on inherited opulence but on the virtues of clarity and honesty. Out of poverty came precision; out of loss, a new sense of measure.

Toward a Regional Voice

By the end of the century, Mississippi’s artists were developing a style distinct from both Northern academies and European precedent. Their work emphasized direct observation and the textures of local life. Instead of mythic landscapes, they painted fields and towns as they were—muddy, luminous, flawed.

This was the foundation of regionalism long before the term existed: art grounded in place rather than ideology. It emerged from Reconstruction’s discipline, from the need to make beauty with limited means. The war had destroyed grandeur but left behind truth, and in that truth Mississippi began to find its voice.

Enduring Lessons

Reconstruction art in Mississippi is less visible than that of any other period, yet it established the moral terms of the state’s creativity. It taught that art could arise from scarcity, that craft could bear as much meaning as high culture, and that memory itself is an artistic act.

In the mended portraits, the rebuilt churches, and the quiet dignity of photographic poses, Mississippi learned to see itself anew. The lesson would echo into the next century: art is not a luxury of peace but a method of survival.

The Early 20th Century — From Regionalism to Modernism

When the twentieth century dawned, Mississippi stood between isolation and discovery. Railroads connected its towns to the wider nation, bringing art supplies, traveling exhibitions, and ideas that had once seemed remote. Yet the state’s own landscape—its light, its poverty, its endurance—remained the central subject. Mississippi artists began to translate familiar sights into new languages, from painterly realism to the crisp geometry of abstraction.

New Deal Beginnings

The 1930s, though economically brutal, proved unexpectedly fertile for Mississippi’s arts. Federal programs such as the Works Progress Administration and the Section of Fine Arts commissioned murals, sculptures, and public buildings that gave artists employment and audiences alike.

Murals appeared in post offices and courthouses from Meridian to Greenwood. Painted in tempera or oil on plaster, they depicted agriculture, industry, and regional history in a simplified, heroic style. The WPA’s insistence on local subjects aligned perfectly with Mississippi’s visual instincts: art rooted in soil and story.

Murals and Messages

Artists like Karl Wolfe and Richard Kelso found in these projects both patronage and purpose. Wolfe’s early designs, influenced by Mexican muralism, balanced classical composition with Southern narrative. Farmers harvest cotton under a blazing sun; riverboats glide through ochre haze. The themes were pragmatic yet poetic, expressing dignity through labor rather than myth.

Audiences, often unaccustomed to public art, learned to read walls as civic texts. Townspeople debated the proper shade of the Delta sky or whether a figure’s posture seemed authentic. Through such debates, art reentered public conversation—not as luxury, but as shared heritage.

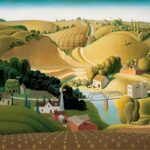

Regionalism and the Southern Image

The national Regionalist movement, led by painters like Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood, resonated strongly in Mississippi. Local artists embraced the movement’s call to portray ordinary life with clarity and pride. Painters turned their attention to cotton pickers, fishermen, and town squares, seeking beauty in the familiar.

Yet Mississippi’s Regionalism carried a different weight. Its artists painted not merely nostalgia but endurance. The humid atmosphere softened outlines; the light blurred sentiment into melancholy. Where Northern Regionalism often celebrated triumph, Mississippi’s version spoke of survival.

Women in the Studio

Art education expanded through women’s colleges such as Belhaven and Mississippi State College for Women (now Mississippi University for Women). Female artists, once confined to watercolor and embroidery, began exhibiting oils and prints at regional fairs.

Figures like Marie Hull of Jackson emerged as pivotal. Her landscapes and bird studies, bold in color and structure, bridged realism and abstraction. Hull’s career demonstrated that modernity could grow from local observation. She taught others to see Mississippi not as subject alone but as source of form—a principle that guided the state’s art for decades.

Photography and the Documentary Eye

The Depression years also witnessed the rise of photography as art and evidence. Federal photographers such as Walker Evans and Eudora Welty (then working for the WPA) documented rural life with precision and empathy. Their images—farmhouses leaning under humidity, faces lit by kerosene—captured the lyricism of endurance without sentimentality.

Welty’s photographs in particular shaped Mississippi’s modern visual identity. Though she would later gain fame as a writer, her lens taught a generation of artists to balance realism with mystery. The photograph became both document and poem, setting the tone for the state’s later engagement with narrative imagery.

Craft and Continuity

Parallel to painting and photography, Mississippi’s crafts entered a golden phase. Pottery studios flourished in small towns, blending vernacular tradition with modern design. Folk artisans reinterpreted utility as art, their glazes experimental yet earthy.

Three recurring directions marked this renewal:

- Functional modernism, where form followed everyday use yet revealed sculptural grace.

- Decorative revival, emphasizing pattern and texture rooted in Native and African influences.

- Experimental glazing, combining local clays with new chemical pigments to achieve metallic or iridescent surfaces.

These craft movements anticipated later mid-century design philosophies, proving that innovation could emerge far from metropolitan centers.

Abstraction and the Gulf Light

By mid-century, the Gulf Coast’s clarity of light began attracting painters exploring abstraction. The luminous air of Biloxi and Ocean Springs seemed to dissolve edges, encouraging artists to emphasize color and rhythm over representation.

Walter Inglis Anderson, though often categorized separately, exemplified this turn. His murals and block prints transformed natural observation into near-mythic pattern. The repetition of birds, shells, and waves across his work echoed the ancient Mississippian sense of rhythm—a continuum between early mound art and modern design.

Art Colony and Community

In 1938, artists established the Mississippi Art Colony near Utica, creating a haven for exchange and mentorship. Painters and sculptors gathered each summer to study, exhibit, and debate, often under open skies. The colony fostered dialogue between traditionalists and experimenters, ensuring that Mississippi’s art remained both grounded and progressive.

Workshops introduced printmaking and modern compositional theory to students from across the state. Out of these sessions grew an informal network that sustained Mississippi’s art infrastructure for decades, bridging the Depression into the postwar era.

The Postwar Shift

After World War II, returning veterans and G.I. Bill students swelled art departments at state colleges. Exposure to European modernism through military service broadened horizons. Abstract Expressionism and Surrealism arrived slowly but decisively, challenging the narrative realism that had dominated local art.

Younger painters experimented with gesture and scale while retaining Mississippi’s tactile intimacy. Even when brushwork turned spontaneous, the imagery of river, field, and storm remained implicit. Modernism did not erase regional identity—it amplified it.

Continuities and Contradictions

By the 1950s, Mississippi’s art world stood at a crossroads of style and conscience. The same decade that produced lyrical abstractions also witnessed the stirrings of the Civil Rights era, which would redefine artistic purpose. Yet the groundwork laid by early-century artists ensured that Mississippi possessed institutions, teachers, and audiences ready to engage.

Looking back, the journey from Regionalism to Modernism in Mississippi reads not as rupture but as maturation. The hand that once painted cotton fields now explored color fields; the potter who once shaped jugs now created sculpture. Through decades of change, one principle endured: art here begins with place, and even in abstraction, the Delta’s horizon remains visible beneath the paint.

The Mississippi Art Colony and the Culture of Gathering

Every region has its informal capitals of creativity—places where artists converge not for commerce or fashion but for exchange. In Mississippi, that center took root not in a city but in a patch of countryside outside Utica. The Mississippi Art Colony, founded in 1938, became both sanctuary and schoolhouse, its cabins and open studios echoing each autumn with the scrape of palette knives and the murmur of critique. More than any museum or university, it forged a living lineage, linking generations of painters and sculptors through conversation and shared weather.

Beginnings in a Barn

The colony began almost accidentally. In the late 1930s, a small group of Jackson and Gulf Coast artists—among them Marie Hull, Karl Wolfe, and painter Bess Dawson—gathered at Allison’s Wells, a rural resort known for its mineral springs. They rented a barn as makeshift studio space, improvising easels from doors and sawhorses. What started as a weekend retreat became a pattern: art made communally, criticism offered with equal parts rigor and affection.

The setting mattered. Surrounded by pine woods and rolling farmland, participants worked without the distractions of urban expectation. Meals were communal, critiques public, and the hierarchy of reputation dissolved in the heat of shared labor. Out of those early sessions grew the formal Mississippi Art Colony, an institution sustained less by funding than by faith in practice itself.

The Character of the Colony

Unlike academic workshops or art leagues, the colony favored dialogue over doctrine. Visiting instructors from across the South and Midwest introduced new techniques—printmaking, watercolor, abstraction—while the Mississippi regulars translated these ideas into their own vocabulary of color and landscape.

Life at the colony followed a rhythm both disciplined and free. Mornings began with lectures or demonstrations; afternoons were devoted to painting in the open air. Evenings brought critique sessions that could stretch past midnight, fueled by coffee, debate, and the chorus of insects outside. The aim was not consensus but clarity—a sharpening of vision through friction.

Women at the Core

From its inception, the colony offered women artists rare professional autonomy. Figures like Bess Dawson, Mildred Wolfe, and Dusti Bongé found there an environment that judged on merit rather than gender. Their works—ranging from luminous still lifes to surrealist abstractions—expanded Mississippi’s artistic vocabulary beyond the expected themes of landscape and labor.

This female leadership shaped the colony’s ethos: seriousness without solemnity, experimentation grounded in craft. While the broader art world of mid-century America remained heavily male, the colony quietly practiced equity by example. Its alumni list reads as a record of women who refused provincial limitations, proving that professional ambition and regional loyalty could coexist.

Technique and Translation

Workshops at the colony mirrored broader national trends while adapting them to local sensibility. In the 1940s and 1950s, when Abstract Expressionism swept New York, Mississippi painters experimented with gesture but retained figurative anchors—a barn roof, a stand of trees, the sweep of river light. Visiting instructors introduced theories of color harmony and design rooted in Bauhaus principles, which participants absorbed without sacrificing warmth or narrative.

Three technical hallmarks distinguished the colony’s output:

- Controlled improvisation, where brushwork remained loose but composition stayed balanced.

- Natural palette, favoring the ochres, greens, and silvers of southern light over high modernist primaries.

- Material curiosity, as artists tested homemade gesso, local clays, and even pine resin as mediums.

The colony thus became both conservatory and laboratory, a place where tradition met experiment without anxiety.

The Social Fabric of Art

Just as crucial as technique was community. The colony’s gatherings offered companionship in a profession often marked by solitude. Painters from rural towns found peers who understood their obsession with light and surface. Teachers returned to their classrooms reenergized, carrying new methods and anecdotes.

Evenings often culminated in informal exhibitions, canvases propped against tree trunks under lantern light. Discussion ranged from pigment to politics, from art history to the price of eggs. Out of such ordinary fellowship arose an enduring network that connected isolated artists across the state.

Challenges and Continuity

The colony endured floods, fires, and fluctuating finances. When the Allison’s Wells resort burned in 1963, members relocated temporarily to Camp Yocona, then later to a permanent home at the Henry S. Jacobs Camp near Utica. Each move tested loyalty yet also reinforced purpose. The artists understood that place mattered less than presence—the act of gathering itself was the artwork’s frame.

Despite decades of social change, the colony maintained its intergenerational spirit. Students returned as teachers; mentors watched protégés mature into colleagues. Annual sessions became rituals of renewal, each year adding another layer to Mississippi’s ongoing conversation about art and identity.

Influence Beyond the Pines

The colony’s impact extended far beyond its seasonal sessions. Alumni went on to found galleries, teach in universities, and shape public collections. Karl and Mildred Wolfe established the Wolfe Studio in Jackson, mentoring artists who would define mid-century Mississippi painting. Bess Dawson co-founded the Gulf Coast Art Association, spreading the colony’s ethos to coastal communities.

Exhibitions of colony work toured regional museums, introducing broader audiences to Mississippi modernism—a style both restrained and radiant. Through these networks, the colony became Mississippi’s unofficial academy, producing continuity in a state otherwise lacking formal institutions of art education.

A Rhythm of Renewal

By the late twentieth century, when art colonies elsewhere waned, Mississippi’s persisted. Participants described it less as an organization than as a season—a time when isolation gave way to shared purpose. Even as digital technology and global art markets transformed creative life, the colony remained devoted to direct encounter: eye to eye, hand to brush, canvas to light.

Younger artists, raised amid speed and distraction, found in its slow pace a kind of revelation. The colony’s enduring rhythm—work, critique, conversation, silence—offered what contemporary culture rarely does: time. In that deliberate tempo lay the secret of its longevity.

Legacy and Living Memory

Today, archives of sketches, photographs, and letters trace the colony’s evolution across nearly a century. Yet its true legacy lives in the habits it instilled: generosity in critique, courage in experiment, loyalty to place. Many of Mississippi’s most respected artists still describe their first session there as a moment of awakening—the instant when art ceased to be solitary and became communal.

The Mississippi Art Colony proved that a small state could sustain a big conversation, that artistic modernity need not mean exile from home. Beneath the pines, painters and sculptors forged not a style but a way of working—rooted, disciplined, and open to surprise. In that sense, every Mississippi artist who gathers brush or clay continues the colony’s work: to make art not just in community, but as community itself.

Vernacular Visionaries and Self-Taught Artists

If the Mississippi Art Colony represented discipline and dialogue, another current of creativity flowed outside its frame—personal, untutored, and defiantly local. Across the state’s small towns and backroads, individuals with no formal training transformed yards, houses, and found materials into radiant testaments of imagination. Their art, often dismissed as eccentric or “outsider,” revealed a Mississippi genius for invention without permission.

Origins in Everyday Making

Self-taught art in Mississippi grew from the same soil that nourished its crafts. The line between usefulness and beauty had always been thin: a quilt might warm a bed yet dazzle the eye, a hand-painted sign might preach as well as advertise. When isolation and poverty limited access to galleries, imagination turned inward and outward at once—toward memory, religion, and the materials at hand.

By the mid-twentieth century, as modernization eroded rural life, such personal worlds multiplied. The decline of small farms left time and space for transformation. Old lumber became sculpture, discarded glass became ornament. The impulse was less rebellion than necessity—making meaning from what remained.

Mary T. Smith and the Painted Fence

In Hazelhurst, Mary T. Smith turned her yard into both gallery and autobiography. On fences, doors, and scrap tin she painted bold figures outlined in black, faces split between smile and astonishment. Her text—phrases of faith, fragments of speech—became part of the composition, a rhythm of letters as visual as sound.

Two paragraphs suffice to grasp her power: the brush as handwriting, the fence as manuscript. Neighbors saw eccentricity; collectors later recognized vision. Smith’s art reduced form to urgency—no shading, no illusion, only statement. Every board declared her existence, unmediated by approval.

L. V. Hull and the Gospel of Decoration

In Kosciusko, L. V. Hull covered her house, car, and yard with jewelry, mirrors, plastic flowers, and beads. Her aesthetic was accumulation—glitter as blessing. To walk through Hull’s yard was to enter a sermon on joy: color upon color, surface upon surface, ordinary objects reborn as testimony.

Hull’s art operated by instinct rather than plan. She called her home “Heavenly Joy,” explaining that every shiny thing deserved another chance to shine. Visitors left with the sense that abundance itself could be a moral stance. In a state long defined by restraint, Hull’s exuberance became revelation.

Loy Bowlin, the Original Rhinestone Cowboy

From McComb came Loy Bowlin, who transformed his house into the “Beautiful Holy Jewel Home” and himself into artwork. Wearing rhinestone suits and mirrored sunglasses, he adorned walls, ceilings, and furniture with glitter and paper collage. The result was part shrine, part theater, entirely sincere.

Bowlin’s transformation blurred line between artist and artwork. His persona—a Southern cowboy saint—embodied the performance of self as creation. Critics later linked his work to Pop art, yet Bowlin never sought irony. His sparkle masked solitude; his joy was armor against invisibility.

Reverend H. D. Dennis and Margaret’s Grocery

Near Vicksburg, Reverend Dennis and his wife Margaret turned their small store into a fortress of faith. Brightly painted scripture covered every surface; towers of cinderblock rose like modern mounds. Dennis proclaimed it “The House of the Lord,” but its mosaics of sign paint, bottle caps, and lettering also formed a monumental folk collage.

The couple’s collaboration exemplified Mississippi’s vernacular architecture of devotion—structures built not for permanence but for praise. Tourists came seeking spectacle; locals came for groceries. Both left confronted by art that made no distinction between the sacred and the daily.

Earl Wayne Simmons and the Order of Chaos

In north Mississippi, Earl Wayne Simmons assembled sprawling metal sculptures from machinery and farm tools. His yard, filled with welded angels and beasts, hummed like an industrial garden. Where Hull sought glitter, Simmons sought gravity—rust and torque as poetry.

His creations, massive yet delicate, fused mechanical logic with visionary impulse. Each figure seemed caught mid-gesture, an emblem of struggle between human and material. In a state where labor shaped identity, Simmons gave that labor form.

Techniques of the Untrained

Despite their variety, Mississippi’s self-taught artists shared methods born of resourcefulness. Paint came from hardware stores, supports from scrap wood or sheet metal. Precision mattered less than conviction. Surfaces cracked, colors bled, but meaning held.

Three techniques recur throughout this art:

- Improvisation of material, turning detritus into medium.

- Repetition as ritual, echoing religious chant or pattern.

- Integration of text and image, merging word, faith, and form.

These strategies, intuitive yet rigorous, parallel avant-garde experiment though developed in isolation. They demonstrate that necessity can produce its own aesthetics of truth.

From Yard to Museum

During the 1970s and 1980s, curators and collectors began to recognize these environments as vital expressions of American art. Museums such as the Mississippi Museum of Art and the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum later included works by Smith, Hull, and Bowlin in exhibitions exploring Southern creativity. Recognition brought preservation but also tension: what happens when private devotion becomes public property?

Efforts to document these sites often coincided with their decay. Weather, neglect, and development erased many environments even as scholars catalogued them. Preservationists faced paradox—the act of saving often required dismantling.

Faith, Vision, and Identity

Most of Mississippi’s vernacular artists framed their work through religion rather than art theory. Biblical quotation, crosses, and prophetic slogans appear throughout, yet the tone is intimate rather than institutional. These makers saw creation as conversation with the divine, not commentary on culture.

Their faith gave coherence to experimentation. In Hull’s mirrored house or Dennis’s painted fortress, theology becomes texture. Belief itself provides structure, making art both confession and celebration.

Dialogue with Modernism

Ironically, the very qualities that once marked these artists as “outsiders”—directness, materiality, repetition—align them with twentieth-century modernism. The flat planes of Mary T. Smith echo Abstract Expressionism; Bowlin’s glittering surfaces parallel assemblage art; Simmons’s welded forms anticipate minimalist sculpture.

Mississippi thus produced modernism without manifesto. Its self-taught creators distilled international ideas into local necessity. Their works remind viewers that innovation often begins far from theory, where imagination meets survival.

Enduring Influence

Today, the legacy of Mississippi’s vernacular visionaries endures in galleries, archives, and memory. Contemporary artists cite them as ancestors of authenticity—a proof that art need not seek permission. Community organizations in places like Hazlehurst and McComb maintain festivals and exhibitions honoring their spirits, keeping creativity entwined with daily life.

To stand before Mary T. Smith’s fence or the remnants of Reverend Dennis’s towers is to feel Mississippi’s defining truth: art here grows from conviction, not curriculum. The self-taught transformed solitude into spectacle and scarcity into splendor. Their yards, once dismissed as clutter, have become Mississippi’s open-air museums of belief.

The Andersons, the Ohr, and the Gulf Coast Imagination

Mississippi’s Gulf Coast has always felt slightly apart from the rest of the state—saltier in air, lighter in color, closer in temperament to the Caribbean than to the cotton fields. Its artists absorbed the shimmer of water and sky as both subject and medium, creating works that seemed to breathe the coast’s shifting atmosphere. Out of this luminous margin emerged two of Mississippi’s most original figures: George Ohr, the self-proclaimed “Mad Potter of Biloxi,” and Walter Inglis Anderson of Ocean Springs. Around them grew a vision of art that was experimental, solitary, and elemental, as changeable as the tide.

George Ohr and the Revolution of Clay

George Ohr was born in Biloxi in 1857 to a German immigrant family of craftsmen. Restless and theatrical, he apprenticed as a potter and soon began twisting clay into shapes no one had seen before—vessels that leaned, buckled, or spiraled, their surfaces rippling like windblown water.

Ohr called himself “the greatest art potter on earth,” a claim both humorous and sincere. His pots defied the utilitarian expectations of his trade. Handles became gestures, lips folded inward or flared outward, and glazes shimmered with metallic unpredictability. He threw thousands of forms between the 1880s and early 1900s, each one a small improvisation, all insisting that clay could speak emotion as vividly as paint.

Technique as Personality

Ohr’s methods were as idiosyncratic as his results. He threw paper-thin walls on the wheel, sometimes collapsing them deliberately, embracing accident as design. His glazes—reds, greens, gunmetal grays—came from obsessive experiment with minerals and firing temperatures.

He also crafted his own mythology. With wild hair and curling mustache, Ohr posed for photographs cradling his pots like infants, eyes gleaming with mischief. He was both artisan and performance artist, decades before the term existed. The act of making became theater, each pot a relic of his choreography with the wheel.

Misunderstood Modernist

During his lifetime, Ohr sold little and was dismissed as eccentric. Yet his work anticipated twentieth-century abstraction in both form and philosophy. The distortions that scandalized his contemporaries would later echo in the ceramics of Peter Voulkos and the sculptures of Henry Moore. Ohr’s insistence that “no two pots are alike” declared individuality as aesthetic law.

When his studio burned in 1905, he salvaged the surviving pieces and stored them until his death in 1918. Decades later, rediscovered by collector James Carpenter and architect Frank Gehry, Ohr’s legacy emerged as prophetic: the modernist’s faith in imperfection, born on a Mississippi wheel.

The Anderson Family of Ocean Springs

A generation later, another coastal visionary extended Ohr’s spirit in new directions. Walter Inglis Anderson (1903–1965) belonged to a family of artists whose reach shaped southern modernism. His brothers Peter and Mac Anderson founded Shearwater Pottery in 1928, producing elegant wares that blended Art Deco refinement with local color. Walter, trained at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, returned to Ocean Springs to decorate pottery, carve linoleum blocks, and paint the natural world that surrounded him.

The Shearwater compound became both workshop and philosophy. Its open studios, kiln houses, and family dwellings formed a small kingdom of creativity where art served daily life. Dishes, tiles, and murals carried motifs of birds, fish, and flowers drawn from the Gulf’s ecosystem. For the Andersons, craft and nature were inseparable languages.

Walter Anderson’s Private Cosmos

Walter Anderson’s personal work, however, reached far beyond pottery. He filled notebooks and murals with kaleidoscopic visions of the Mississippi coast—herons, storms, dunes, and trees rendered in rhythmic, almost musical line. His method combined scientific observation with mystical absorption.

Twice he rowed a small boat to Horn Island, living alone for weeks among pelicans and storms. There he painted on walls, driftwood, and paper, recording a dialogue between human perception and natural energy. His journals describe not escape but union: “I paint to find out what makes the world go round.”

Line, Pattern, and Revelation

Anderson’s block prints exemplify his synthesis of discipline and spontaneity. Carved in linoleum and printed on tissue-thin paper, they combine the precision of Japanese woodcut with the fluidity of coastal light. Birds repeat in looping rhythm; waves fracture into abstract pattern. Each print reads as both documentation and dream.

The murals he painted on the walls of the Ocean Springs Community Center in 1951 are his crowning public achievement. Unveiled after his death, they wrap the viewer in an encyclopedic celebration of coastal flora and fauna—color, motion, and myth intertwined.

The Coast as Creative Ecology

Both Ohr and Anderson treated the Gulf Coast not merely as subject but as collaborator. Its humidity affected clay drying time; its light defined palette; its storms dictated rhythm. To create there was to negotiate with weather. The region’s instability—hurricanes, salt air, corrosion—became metaphor for artistic risk.

Their works translate the coast’s physical properties into aesthetic principle. Ohr’s twisted pots echo the curl of waves; Anderson’s swirling compositions mimic wind and tide. The coast’s unpredictability taught them that control is illusion, and beauty often lies in surrender.

Community and Legacy

The artistic communities surrounding these figures—Shearwater Pottery, the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum in Biloxi—preserve their experiments as both craft and revelation. Shearwater continues to produce pottery under Anderson family guidance, maintaining the lineage of design and glaze innovation. The Ohr-O’Keefe Museum, housed in Gehry’s sculptural buildings, mirrors Ohr’s restless spirit in architecture that curves and gleams like his pots.

Visitors to these sites encounter continuity: from Ohr’s clay to Anderson’s paper, from kiln to sketchbook, from solitude to shared inheritance. The Gulf Coast remains Mississippi’s laboratory of form, where boundary between art and life dissolves like mist over water.

Dialogues Across Time

Though separated by decades, Ohr and Anderson speak a common language of transformation. Both rejected convention, embraced imperfection, and sought revelation in process. Their art insists that making is a form of seeing, that experiment is devotion.

In their hands, Mississippi modernism found its purest form: humble materials charged with transcendence. Their legacy continues in contemporary coastal artists who mix sculpture, printmaking, and environmental art, carrying forward the conviction that the coast itself is a studio.

Enduring Radiance

Standing before Ohr’s iridescent pots or Anderson’s flooded colors, one senses the same pulse—the Gulf translated into matter. Clay, pigment, and line become extensions of wind and tide. Mississippi’s coast, long seen as periphery, proves to be the crucible of its modern art.

In the shimmer of glaze and the sweep of brushstroke lives a faith older than modernism: that creation mirrors creation, and that to make art in Mississippi is to join the rhythm of its light.

Museums, Collecting, and Institutional Growth

For much of Mississippi’s history, art lived in private homes, schools, and churches rather than in museums. The state’s first collectors were not patrons in the European sense but civic organizers, teachers, and librarians who believed beauty should be shared. Out of their persistence emerged institutions that now define Mississippi’s cultural landscape. Each began modestly—with borrowed paintings, donated shelves, and improvised lighting—and grew into centers where the state could see itself reflected.

Lauren Rogers and the First Museum

The story begins in Laurel in 1923 with the founding of the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art. Established as a memorial by the Rogers family, whose timber fortune had built the town, it became Mississippi’s first art museum and set a precedent for local stewardship. Its initial collection included European paintings, Native American baskets, and Japanese prints—eclectic yet disciplined, embodying curiosity rather than vanity.

The museum’s architecture, a blend of Georgian and Mediterranean styles, symbolized aspiration without ostentation. Its galleries, cooled by ceiling fans and filled with natural light, invited both farmers and industrialists. For many visitors, this was their first encounter with original art; for Mississippi, it marked the birth of a public visual conscience.

The Mississippi Museum of Art: From Loan Gallery to Landmark

Jackson’s Mississippi Museum of Art began humbly in the 1920s as an art association staging exhibitions in borrowed rooms. Over decades it evolved through relocations, floods, and economic shifts until, in 1978, it became a permanent institution. Its current downtown building, completed in 2007, represents both culmination and renewal—a modern structure of glass and concrete that opens the city to its own creative history.

The museum’s collection now spans regional and national works, from early Southern portraiture to contemporary installations. Yet its defining feature remains its sense of belonging. Community exhibitions, children’s workshops, and outdoor sculpture gardens blur the line between institution and neighborhood. In a state often skeptical of elitism, the museum succeeds by being porous—its walls metaphorical as much as physical.

Coastal Guardians: The Ohr–O’Keefe Museum

On the Gulf Coast, the Ohr–O’Keefe Museum of Art in Biloxi carries forward the eccentric genius of George Ohr. Designed by architect Frank Gehry, its cluster of metallic pods and curving forms rises like sculpture from the hurricane-scarred landscape. Opened in stages beginning in 1998, the museum functions as both tribute and experiment, combining exhibition space with studios and community classrooms.

Its existence signals a shift in Mississippi’s cultural geography: art no longer confined to the capital or upland towns but thriving where water meets sky. The museum’s architecture, reflective and fragmentary, mirrors Ohr’s philosophy that beauty grows from imperfection. Visitors encounter not static display but dialogue—between artist and architect, past and present, resilience and risk.

University Collections and Educational Vision

Beyond public museums, Mississippi’s universities built vital art centers that nourished generations of artists. The University of Mississippi Museum in Oxford houses classical antiquities alongside modern regional works, creating conversations across centuries. Mississippi State University and the University of Southern Mississippi maintain galleries that double as classrooms, proving that curation can be pedagogy.

Tougaloo College stands out for its remarkable modern art collection assembled during the Civil Rights era, including works by Picasso, Romare Bearden, and Elizabeth Catlett. Acquired through partnerships with New York supporters, the collection gave Black students direct access to global modernism, turning a small liberal-arts college into an unlikely cultural capital. Each campus museum extends the idea that art in Mississippi is not luxury but curriculum—part of how citizens learn to see.

Private Collectors and Regional Patrons

Much of Mississippi’s artistic preservation owes itself to individuals rather than institutions. Lawyers, teachers, and small-town physicians quietly amassed paintings and crafts, often storing them in attics until local museums could acquire them. Their motivations mixed pride and curiosity rather than investment.

Three patterns recur among these private patrons:

- Genealogical collecting, preserving portraits and heirlooms as family history.

- Regional loyalty, favoring artists born or working within the state.

- Educational generosity, donating works to schools and libraries to ensure visibility.

Such private initiative filled gaps left by limited public funding. The state’s art map, scattered but resilient, remains held together by private conviction as much as by tax support.

Challenges of Preservation

Mississippi’s climate is both muse and menace. Humidity warps canvas; hurricanes threaten entire collections. The 1969 devastation of Hurricane Camille and the later blow of Katrina in 2005 destroyed thousands of artworks and archives. In response, museums developed rigorous conservation programs, partnering with national institutions for restoration and training.

These crises fostered solidarity among curators and volunteers. When Biloxi’s collections faced ruin after Katrina, staff from Jackson and Laurel traveled south with generators and packing materials. The act of rescue itself became part of the state’s cultural narrative—art defending art against erasure.

Funding and the Question of Access

Sustaining museums in a small, economically diverse state remains a delicate equation. Endowments are modest; public grants fluctuate with politics. Institutions rely on community fundraisers—galas, auctions, membership drives—that double as social rituals.

To counter economic barriers, museums have emphasized accessibility: free admission days, bilingual materials, partnerships with public schools. The goal is simple but radical—to make art as ordinary as libraries. The effort mirrors Mississippi’s broader history of self-help and communal resilience, transforming scarcity into participation.

Curatorial Shifts and Inclusion of Local Voices

Recent decades have witnessed a curatorial turn toward local narratives once overlooked. Exhibitions now highlight folk and self-taught artists, photographers documenting rural life, and crafts once considered minor. The Mississippi Museum of Art’s “Picturing Mississippi” project in 2017 exemplified this reorientation, weaving fine art and vernacular image into a single story of place.

This inclusiveness has less to do with ideology than with accuracy. A full account of Mississippi’s art must encompass both marble bust and painted fence. Museums, long perceived as arbiters of taste, have become historians of diversity in method rather than politics—charting how many languages beauty can speak within one landscape.

Architecture and the Aesthetics of Space

The buildings themselves form part of the narrative. From the neoclassical calm of Laurel’s galleries to Gehry’s fragmented metal pods in Biloxi, Mississippi’s museums reflect evolving ideas of what a museum should be: temple, classroom, or conversation.

Architectural variety mirrors artistic diversity. Each structure negotiates light—the cool diffusion of northern skylights, the sharp glitter of Gulf sun—so that environment becomes exhibit. In Mississippi, even concrete and glass participate in the dialogue between art and climate.

Continuity and Future Stewardship

As new generations take leadership, Mississippi’s museums face both promise and challenge: digital archives expand reach, yet maintenance costs climb. Virtual exhibitions broaden audience, but the tactile immediacy of seeing a canvas in humid air remains irreplaceable.

What unites these institutions is endurance. From Laurel’s 1920s optimism to Biloxi’s post-Katrina resilience, they share a conviction that art is part of civic life, not ornament to it. In a state often defined by its struggles, museums stand as acts of faith—faith that preservation can be progress, and that beauty, once made visible, belongs to everyone.

Contemporary Mississippi Art — Place, Memory, and Renewal

To speak of contemporary Mississippi art is to speak of persistence. The state’s artists have never enjoyed the luxury of detachment; their work remains bound to place, haunted by memory, and sustained by renewal. Over the last half century, painters, sculptors, photographers, and multimedia artists have balanced regional loyalty with global awareness. The result is an art scene that feels at once introspective and outward-looking, steeped in landscape yet attuned to modernity’s dissonant rhythms.

From Regionalism to Resonance

The late twentieth century marked a gradual departure from narrative realism toward broader formal and conceptual experiments. Artists trained in Mississippi’s colleges began engaging with minimalism, conceptualism, and installation art, filtering those styles through the textures of their own environment.

The land remained central even as representation fractured. In abstract canvases, fields of color echo Delta horizons; in sculptural installations, clay and reclaimed wood evoke the continuity of labor. Rather than rejecting heritage, these artists reframed it—transforming Mississippi’s regional identity into a medium of resonance rather than restraint.

Painters of Reflection and Refusal

Among the state’s leading contemporary painters, variety defines unity. Some pursue luminous realism, others conceptual austerity, yet all treat surface as site of memory.

William Dunlap, born in Webster County, merges history and allegory in layered landscapes where text and image converse. His canvases hold both reverence and irony—painted swamps crossed by ghostly figures, rivers accompanied by handwritten fragments. Dunlap’s work exemplifies Mississippi’s dialogue with itself: self-critical yet affectionate.

Women Reclaiming Vision

Female artists have expanded Mississippi’s modern vocabulary, continuing the legacy of Marie Hull and Bess Dawson while pursuing new themes of domestic space, spirituality, and body. Sculptor Anne Siems, painter Ke Francis, and multimedia artist Eudora Welty (in her visual legacy as photographer) each illustrate distinct approaches to translating interior life into public form.

Younger voices such as Carlyle Wolfe Lee and Randy Hayes integrate botanical study and digital layering, creating images that balance order and wildness. Their art suggests that observation—patient, precise, local—remains Mississippi’s most radical gesture.

Photography and the Persistence of the Real

Photography has always been Mississippi’s most democratic art form. In recent decades, photographers such as Maude Schuyler Clay, Susan Worsham, and Brandon Thibodeaux have refined the tradition of Southern portraiture into essays on endurance and grace.

Clay’s color portraits, taken mostly in the Delta, dissolve nostalgia through intimacy. Her subjects—neighbors, relatives, musicians—stand neither romanticized nor pitied. The photographs’ quiet surfaces hold emotional depth: the stillness before words. Through such images, Mississippi’s everyday life achieves the gravity of myth.

Installation and the Expanded Field

Contemporary Mississippi art extends beyond canvas and lens into installation and mixed media. Artists assemble environments using found materials, sound, and projection, creating immersive experiences rooted in place yet open to abstraction.

Jason Bouldin’s large-scale murals reinterpret sacred themes through contemporary scale and composition, while sculptor Randy Regan constructs environmental pieces from industrial remnants. These works transform ordinary materials—metal siding, driftwood, neon—into metaphors for resilience. The lineage from George Ohr’s twisted clay to such installations is unmistakable: imperfection elevated to form.

Memory as Medium

Memory functions not only as theme but as material. Artists incorporate family photographs, archival documents, and oral histories into their works, turning private recollection into collective artifact. The result blurs boundary between art and testimony.

In mixed-media projects, fragments of handwriting or weathered fabric become carriers of time. The layering of text and image mirrors Mississippi’s own sedimented history—a landscape where stories overlap like strata of silt. The aesthetic of accumulation, once a byproduct of poverty, becomes deliberate composition.

The Landscape Reimagined

Mississippi’s terrain continues to shape vision even when not depicted directly. Painters extract its chromatic logic: the gray-green of cypress shade, the ochre of sunbaked clay, the silver of river haze. In abstraction, these tones persist as emotional codes.

Environmental artists working along the Gulf Coast explore ecological fragility through sculpture and site-specific work. Installations made from reclaimed oyster shells or driftwood meditate on restoration after hurricanes, linking beauty with stewardship. The land that once dictated survival now inspires responsibility—a transformation of gaze into care.

Communities of Creation

Artistic life in Mississippi remains decentralized yet interwoven. Cooperative galleries in Oxford, Jackson, and Ocean Springs host exhibitions that pair established artists with students. Festivals and open-studio events transform small towns into temporary art capitals.

These gatherings echo the old Mississippi Art Colony ethos: critique as fellowship, making as conversation. The state’s modest scale fosters intimacy rather than isolation. Artists see one another’s work not on screens but in person, over coffee or under live oaks—a rare privilege in a dispersed digital age.

Education and Mentorship

Universities play a crucial role in sustaining this network. The University of Mississippi, Mississippi State, and the University of Southern Mississippi maintain active MFA programs that attract national talent while nurturing local identity. Professors double as practicing artists, modeling careers grounded in both teaching and production.

Workshops, residencies, and public-art grants encourage experimentation without forcing conformity to national trends. Through these programs, young artists learn that to be from Mississippi is not to be provincial but to inherit a laboratory of light, form, and endurance.

Technology and the New Audience

Digital media have expanded visibility for Mississippi artists beyond geographic limits. Online exhibitions, streaming performances, and virtual galleries reach audiences far from Jackson or the Gulf. Yet the tactile quality of Mississippi’s art—its emphasis on material, weather, and texture—often resists full translation to screen.

This tension between digital reach and physical presence defines the current era. Artists exploit technology not as replacement but as extension, using video and projection to amplify intimacy rather than erase it. The digital becomes another layer of Mississippi’s long conversation with modernity.

Continuity Through Change

Contemporary Mississippi art resists closure. It is less a movement than a temperament—patient, local, experimental. Its artists, whether working in clay, pixels, or pigment, share an awareness that every creation stands in dialogue with the state’s layered past.

In their persistence, one recognizes Mississippi’s oldest aesthetic principle: transformation through endurance. Each brushstroke, photograph, or installation carries within it the memory of those who made art from scarcity and turned isolation into vision. The state’s present creativity, far from nostalgic, renews that inheritance with every act of making.

Public Art and Civic Engagement

In Mississippi, where civic life often unfolds outdoors—on porches, in parks, beneath courthouse oaks—public art has found its natural stage. Murals, sculptures, and community projects have turned familiar streets into living galleries. These works rarely aim at grandeur; their power lies in intimacy, in the sense that art belongs not to institutions but to neighborhoods.

Murals as Civic Memory

The mural has become Mississippi’s most visible form of public art. In towns like Clarksdale, Tupelo, and Gulfport, blank walls have transformed into chronicles of local history. Artists mix realism with symbolism, portraying blues musicians, civil leaders, and anonymous citizens in a palette drawn from the land itself—brick reds, river greens, and faded gold.

One striking example stands in Indianola, where a long brick façade celebrates B. B. King’s life. Painted instruments stretch across the surface like a visual melody. Visitors photograph themselves against the mural, adding their shadows to its rhythm. Through such acts, art ceases to be backdrop and becomes shared performance.

Community Collaboration

Unlike the solitary studio, public art depends on collective effort. Town councils, schools, and volunteers provide walls and funding; artists supply vision. The process itself becomes educational. Residents see sketches evolve into scale drawings, watch painters on scaffolds, and recognize their own streets taking on new meaning.