A thousand years before Iowa’s grid of roads and farmsteads appeared, its river valleys and wooded ridgelines bore witness to a different kind of design—one carved not by surveyors but by the hands of Native people who worked the land into forms with both practical and symbolic meaning.

Effigy Mounds and the Aesthetics of Earthwork

Near the confluence of the Mississippi and Wisconsin Rivers, on the eastern edge of what is now Iowa, more than 200 earthen forms rise subtly from the forest floor. Some resemble bears, birds, or serpents when viewed from above; others are long, low ridges, like sleeping figures buried just beneath the soil. These are the effigy mounds of northeastern Iowa, built between 600 and 1200 AD by Native peoples of the Woodland tradition—groups that predate the Ho-Chunk, Ioway, and Meskwaki who would later inhabit the region.

Though often discussed in archaeological terms, the mounds have an undeniable visual logic. Their contours mirror natural forms and carry symbolic significance, most likely tied to seasonal cycles, clan identities, and cosmological beliefs. The builders left no written explanation, but the consistency of scale, placement, and repetition suggests an established visual vocabulary—a system of signs inscribed not on paper or canvas, but on the land itself.

What’s most striking is the restraint and integration. These were not towering monuments, but low, sculpted rises designed to be experienced through movement, memory, and proximity to the terrain. Unlike the ziggurats or pyramids of other ancient cultures, Iowa’s mounds were aligned with animal life, seasonal change, and the rolling geography of the Upper Midwest. In that way, they constitute one of North America’s earliest known examples of landscape art—at once funerary, territorial, and aesthetic.

By the time white settlers arrived in the 1830s, most mound-building had ceased, but the forms endured in local memory. Early surveyors recorded their outlines in field journals; artists traveling up the Mississippi sketched them in notebooks, and some appeared in 19th-century illustrated gazetteers. Yet they were rarely interpreted as art—only as relics. Their makers, now unnamed, were perceived as vanished. That simplification obscured a key fact: many of the same values—natural forms, symbolic compression, rhythmic repetition—continued in the visual culture of the Native nations still living in the area.

Wood, Clay, and Functional Ornament

The everyday artistry of the region’s Native inhabitants—especially the Ioway, Sauk, Meskwaki, and Sioux-speaking groups—was rooted in utility. Their visual culture, like that of most pre-industrial societies, was inseparable from craft. A bowl, a belt, a pipe, or a knife handle could be beautiful, but always served a purpose.

Take the ceramics of Woodland and Oneota cultures, whose descendants remained in Iowa into the 18th and 19th centuries. Their pots were hand-coiled, not wheel-thrown, and often decorated with complex incised patterns: diagonal hatch marks, twisted cords, or comb impressions. These markings, beyond ornament, helped reduce cracking during firing—beauty nested within practicality. Later, clay was also used for miniature figures, gaming pieces, and tobacco pipes—each shaped with a precision and character that suggest the hand of individuals, not anonymous tradition.

Among the Meskwaki—who still live in Iowa today on a sovereign settlement near Tama—the continuity of material traditions persisted even through eras of immense disruption. Meskwaki women were known for black ash basketry, dyed with locally sourced plant pigments, their geometric patterns passed between generations. Men carved wooden ladles, clubs, and ceremonial masks, sometimes integrating trade materials such as metal or glass once contact with Europeans increased. These objects were rarely signed but were often deeply personal, used in dances, rituals, and domestic life, embodying both skill and memory.

Three recurring materials grounded this artful utility:

- Red pipestone from nearby quarries, often carved into ceremonial pipes or pendants.

- Porcupine quills, dyed and woven into clothing and bags before trade beads became common.

- Birch bark, used for containers and pictographic scrolls, especially among groups in Iowa’s northern borderlands.

Each material required intimate knowledge of the land—what to harvest, when, and how to shape it. Art here was not about individual genius or expression, but about maintaining continuity through form and function.

Symbol, Utility, and Seasonal Labor

One of the most distinctive features of Native art in Iowa was its connection to seasonal rhythm. Spring meant the repair of canoes, summer the making of clothing, autumn the carving of tools. The pace of artistic production followed cycles of planting, hunting, and ceremony. As such, the idea of “art for art’s sake”—a European invention—had no equivalent. Ornament was tied to use. Meaning was embedded in motion.

Clothing, especially, reflected this convergence of labor and symbolism. Leggings and shirts made from animal hides were decorated with bone, shell, or dyed quills—not to attract attention, but to express status, kinship, or affiliation. Design motifs were not random. A certain angle or pattern might signify a family group or a spiritual concept; repetition could suggest balance, resilience, or reciprocity with the natural world.

Even temporary constructions, like hunting lodges or festival poles, were arranged with symbolic logic. Their placement and adornment mapped the invisible structure of community and belief, transforming space through repetition and order. This instinct—toward pattern, toward embedded meaning—would resurface much later in the region’s quilting traditions and decorative arts, even among non-Native populations.

An unexpected continuity emerges here. While Native traditions were often disrupted by displacement and war, their design sensibility—rooted in balance, pattern, and deep familiarity with natural materials—did not disappear. Instead, it lingered in adapted forms, influenced settler art subtly, and resurfaced later through intercultural borrowing and local crafts. In that sense, Native artistic influence in Iowa was never static or confined to the past. It remained part of the state’s evolving material vocabulary, even when unacknowledged.

By the mid-1800s, most Native nations had been removed or forcibly relocated from Iowa, though the Meskwaki resisted and eventually purchased land to remain. Their artistic presence continued quietly—woven into powwow regalia, school art projects, basket workshops, and family collections. While not always visible in public museums or galleries, the creative traditions seeded centuries earlier remained active in private life, seasonal ritual, and the land itself.

In Iowa’s art history, then, Native work is not a prelude or prehistory. It is a distinct, intelligent tradition shaped by constraint, endurance, and a deliberate aesthetic of purpose. Where later painters and teachers would frame beauty in oil or bronze, the first artists of Iowa used clay, fiber, soil, and smoke. Their work was no less refined—only quieter.

And like the mounds that still rise along the blufftops near Marquette and Effigy Mounds National Monument, that work has never truly left the landscape.

Foundations on the Frontier: Early Artistic Activity in Iowa Territory

Before there were galleries, art departments, or state fairs, there were maps sketched under canvas tents, portraits hung in dry goods stores, and watercolor scenes tucked inside travel trunks. The earliest artistic activity in Iowa—during its territorial years from 1838 to 1846—was neither professional nor decorative. It was functional, descriptive, and often deeply personal. Artists, if they called themselves that, were more likely to be surveyors, soldiers, schoolteachers, or itinerant tradesmen. But their work laid the visual groundwork for a state that had not yet drawn its borders.

Surveyors and Settlers

Much of Iowa’s earliest visual culture was created by people tasked with measuring it. After the Black Hawk Purchase of 1832 opened large portions of eastern Iowa to white settlement, government surveyors entered the region to divide the land into sections, townships, and ranges. Their tools—compasses, chains, sketchpads—produced an unexpected byproduct: some of the first systematic images of Iowa’s natural contours.

These drawings were not “art” in the European sense, but many possess a raw elegance: river meanders drawn with confident curves, bluff lines rendered with fine cross-hatching, annotations noting “excellent timber” or “sandy loam.” In them, one sees the convergence of technical observation and aesthetic care. For settlers who followed, these renderings were more than topography—they were visual invitations, proof that the land was worth claiming.

Occasionally, these pragmatic sketches gave way to more expressive work. Albert Lea, a U.S. Army engineer who surveyed the upper Iowa and Minnesota rivers in the 1830s, produced finely inked drawings of valleys and ridgelines alongside his maps. These were not romantic landscapes in the Hudson River tradition but direct, almost architectural impressions of place: factual yet attentive, severe yet quietly reverent.

As homesteaders established towns, visual documentation became a necessity. County seats needed to present themselves as orderly, prosperous, and permanent. Lithographers—often based in Chicago or St. Louis—began producing panoramic “bird’s-eye” views of Iowa towns in the 1850s and 60s, drawing from on-site sketches and imagination to create dynamic scenes of civic pride. Though technically promotional, these prints had artistic value: streets teemed with tiny horses, schoolhouses cast long shadows, and each building was labeled, forming a kind of visual index of aspiration.

Military Maps and Landscape Draftsmanship

The U.S. military’s presence in early Iowa, particularly at forts like Fort Atkinson, brought another layer of artistic labor. Officers often doubled as amateur naturalists and draftsmen. Tasked with documenting terrain, native flora, or fort layouts, their sketchbooks preserve an unusual mix of utility and curiosity.

Captain James Allen’s 1840s sketches of the upper Des Moines River, for example, show a restrained style with delicate tree lines and wide sky bands. These images—some published, others left in archives—capture Iowa’s landscape before it was fully transformed by agriculture. Wide floodplains stretch unbroken. Oak groves stand apart like islands. The drawings freeze a landscape in transition: no longer wild, not yet cultivated.

Civilian artists occasionally followed in the military’s wake. George Catlin, while not strictly Iowan, passed through the region and painted scenes of Native encampments and frontier life. His romanticized portraits of native people and midwestern terrain captured national attention and reinforced the idea of Iowa as a threshold between “civilization” and wilderness. Though historically imprecise, his images circulated widely and helped fix certain visual tropes—open prairie, wide rivers, stoic figures—that endured in depictions of Iowa for decades.

It is worth noting how many of these early artists were self-taught. Art instruction was scarce, and supplies often had to be ordered from far away. Pigments might be mixed from local clay or ground minerals. Paper was precious. A frontier artist worked with what he had—often using the same pencil for a topographical sketch and a child’s portrait.

Yet from this scarcity emerged a kind of honesty. The images are rarely idealized. Trees lean in wind. Buildings are crooked. People stand stiffly, eyes fixed ahead. These early Iowa drawings and paintings may lack polish, but they contain something rarer: an unfiltered record of attention.

The Visual Grammar of Homesteading

By the 1840s, as Iowa pushed toward statehood, the visual landscape began to change. New settlers brought with them prints, Bibles, and keepsakes from the East. Some hung lithographs in parlors, others kept daguerreotypes wrapped in cloth. These objects—small, fragile, often religious—formed the nucleus of domestic artistic life on the prairie. They were not made in Iowa, but they mattered deeply to those who lived there. A home with pictures, however modest, signaled stability.

Gradually, Iowa itself became the subject. Amateur watercolorists—often women—painted the view from their cabins: a tree in bloom, a muddy creek, a neighbor’s new barn. Some stitched these scenes into quilts or wove them into samplers. Others preserved them in journals. While most of this work was never shown publicly, it carried the impulse to describe, to hold still a moment of change.

Three types of imagery emerged during this period that would become staples of early Iowan art:

- The homestead portrait, showing the family farmstead with labeled buildings, prized livestock, and the entire household standing in formation—half family tree, half deed.

- The “memory painting,” often done years after the fact, portraying a childhood home or frontier moment in vivid, simplified color—fact blended with nostalgia.

- The commemorative album, filled with pressed flowers, verses, and miniature drawings, often given as gifts or keepsakes between separated families.

Each offered a different answer to the same question: what does it mean to belong to this place?

By 1846, when Iowa achieved statehood, its visual culture was still informal and decentralized, but it had already formed recognizable patterns: careful observation, material restraint, a focus on land and labor. These traits would continue to shape the state’s artistic identity long after railroads and academies arrived. And although professional artists were still rare, a distinctive sensibility had begun to take root—one attentive to the everyday, wary of flourish, and deeply embedded in physical space.

That visual ethos, first practiced by mapmakers and homesteaders, would ripple forward through folk artists, photographers, and eventually the painters of the Regionalist movement. But its roots remained in the sketchbooks and cabins of the Iowa frontier—a place where seeing clearly was not just an artistic act, but a way to survive.

Pioneers with Brushes: 19th-Century Folk Artists and Traveling Painters

By the mid-19th century, Iowa was no longer a frontier but a patchwork of developing towns, farms, and county seats—each asserting permanence through courthouses, rail depots, and brick storefronts. Into this environment came a different kind of pioneer: self-taught artists, limners, and itinerant portraitists who traveled by wagon, train, or foot, offering to paint likenesses, signage, or landscapes in exchange for room, board, or a modest fee. These men and women operated outside formal art academies, yet they shaped the visual imagination of a young state, producing thousands of portraits, townscapes, and devotional images in parlors and kitchens across Iowa.

Portraiture on the Prairie

For most settlers in Iowa, especially between 1850 and 1880, a painted portrait was a rare and meaningful object. Photography was becoming more common, but a photograph could not always convey the presence, importance, or sentiment that a painted image offered. The folk portraitist offered a different kind of visual permanence—one tied to family pride, memory, and display.

Many of these artists came from eastern states, often drifting westward as towns grew and rail lines expanded. Some were trained in basic drawing or sign painting; others were entirely self-taught. What united them was a functional skill and a willingness to work in unstable, often rural conditions. Their studios were temporary: a room above a general store, a back corner of a boarding house, or the home of a client who would feed them during the sitting.

The portraits themselves were direct, sometimes awkward, but always vivid. Faces were painted in fine detail, while clothing and hands were simplified. Backgrounds might feature a window with a vaguely Midwestern landscape or a heavy curtain borrowed from classical European portraiture. The effect was both formal and homespun. In many paintings, the subject stares directly at the viewer, unsmiling but alert, seated stiffly with a family Bible, a memento mori, or a symbol of occupation—a thresher’s cap, a carpenter’s square.

These works were often unsigned, but some names emerge from local histories and museum archives. One such artist was Joseph Henry Sharp, who briefly painted in Iowa before gaining national recognition in the West. Another was Edward S. Derry, who crisscrossed southeastern Iowa offering “likenesses and miniatures” in the 1860s. Even more obscure were artists known only through a few surviving canvases—“The Decorah Limner,” “the Davis County Painter”—identified by style or provenance.

Though modest in technique, these portraits served real social functions:

- They established lineage, often becoming the only preserved image of an ancestor.

- They marked status, showing the subject with books, fine clothes, or land in the background.

- They consoled loss, especially portraits of children or parents painted posthumously from memory or a daguerreotype.

Some were painted over multiple sessions, others in a day. The variation in quality is wide, but even the simplest portraits carry an intensity—a human presence framed in oil, surviving when names and dates have faded.

Painted Barns and Parlor Art

Beyond portraiture, Iowa’s 19th-century folk artists turned their brushes to nearly every paintable surface: barns, furniture, trade signs, stage curtains, and decorative panels in homes and public halls. Much of this work has been lost to time or weather, but enough survives to glimpse a culture that saw no sharp boundary between art and everyday life.

Painted barns, especially in Dutch and German immigrant communities in eastern Iowa, served both practical and symbolic roles. Some bore geometric motifs—stars, pinwheels, compass roses—adapted from Old World traditions. Others were purely practical: advertisements for patent medicines, plows, or seed companies rendered in bold lettering and simple color. In both cases, painting marked a structure as cared-for and visible, part of a living landscape.

Inside homes, parlor paintings became increasingly popular. These included:

- Landscapes, often imaginary, showing mountain scenes, rivers, or idealized farms.

- Still lifes, especially of fruit or game, painted from memory or copied from prints.

- Biblical scenes, adapted from illustrated Bibles and rendered with domestic simplicity.

Many of these paintings were done by women—often using whatever materials were at hand. A curtain rod might double as a straightedge; paint might be mixed with egg or milk. Some women became known locally for their skill and painted works for neighbors. Others left unsigned canvases tucked in attics, later discovered and wrongly assumed to be “professional” works.

There was no art market in the modern sense, only barter and reputation. Yet a quiet tradition developed: one rooted in utility, memory, and visual pleasure. These domestic paintings offered comfort and stability, echoing the values of their surroundings—order, persistence, and a deep attachment to place.

Religion and the Image in Rural Culture

Religious institutions played an understated but powerful role in shaping Iowa’s early visual culture. While many Protestant denominations—particularly Methodists, Baptists, and Congregationalists—maintained iconoclastic attitudes toward art, they nonetheless made room for imagery in forms they considered edifying or morally neutral. Illustrated Bibles, hymnals, wall charts, and stained glass found their way into churches across the state.

Catholic churches, especially in Irish and German communities, embraced more elaborate visual forms. By the late 19th century, Iowa’s rural Catholic churches were commissioning altarpieces, statues, and mural cycles—often from itinerant European artists or local craftsmen trained in ecclesiastical decoration. These artworks, while derivative of European traditions, were adapted to local materials and budgets. Many are still in use today, their colors softened by incense and time.

Religious art in rural Iowa was typically narrative and didactic: Christ teaching, saints healing, angels guiding. But it also functioned as a visual counterweight to the hardships of farm life. Where barns bore the marks of labor, churches bore the marks of hope. The frescoed dome of a church in Dubuque or Carroll might feature gold-leaf stars, trompe l’oeil columns, or pastoral scenes of the Holy Land—imagery that transported worshippers, if only briefly, beyond the horizon of corn and sky.

Meanwhile, Sunday schools often encouraged children to draw or paint Biblical stories. Crude as these efforts were, they seeded a habit of visual expression that sometimes bloomed in adulthood. A surprising number of Iowa folk artists cited church or school drawing lessons as their first exposure to art.

As towns grew, religious festivals and pageants brought their own imagery: banners, costumes, tableaux. These events often required collective painting—of backdrops, signs, or ceremonial props—engaging people who might not otherwise think of themselves as artists. In this way, religious life helped cultivate a vernacular visual language that extended beyond dogma: communal, symbolic, and grounded in rhythm and repetition.

Even in its simplest forms, Iowa’s 19th-century religious art expressed something durable—an understanding that beauty could coexist with austerity, and that images, no less than sermons, had a role in shaping the imagination.

The folk artists and traveling painters of Iowa left behind few manifestos and little documentation. Their work was signed in fenceposts, backdrops, mantelpieces, and faces staring calmly from canvas. They did not think of themselves as forming an “Iowan style,” yet they built a visual culture that reflected the realities of life in a state still defining itself—practical, careful, intimate, and quietly proud.

Lithographs, Schoolhouses, and Almanacs: Print Culture in the 1800s

By the late 19th century, Iowa’s artistic culture had begun to expand beyond canvas and wood into the printed page. The development of small-town presses, illustrated newspapers, and mail-order catalogues introduced new forms of visual engagement. Print culture—particularly lithographs, almanacs, and illustrated textbooks—functioned not just as information delivery but as a visual education system for a largely rural, dispersed population. It democratized imagery in ways that oil painting and formal sculpture could not, embedding pictures into everyday life.

Illustrated Gazetteers and County Histories

In the 1870s and 1880s, a peculiar genre of publishing flourished across Iowa: the county history. Often commissioned by local booster groups or business coalitions, these thick volumes blended town records, family biographies, and industry profiles with lavish illustrations. Their purpose was to project prosperity, permanence, and respectability—and their imagery played a central role in that performance.

Bird’s-eye views of county seats, often created by professional lithographers from cities like Chicago or Milwaukee, were among the most popular features. These panoramic prints offered an aerial fantasy: streets lined with handsome buildings, rivers flowing under tidy bridges, and plumes of smoke rising from industrious mills. While few were drawn from life, the illusion of perspective gave them authority, and residents eagerly subscribed to be included—sometimes even paying extra to have their homes or businesses labeled.

In addition to townscapes, county histories featured illustrated portraits of prominent citizens, drawn from photographs and engraved by hand. These engravings, with their stippled shading and formal dress, often flattered their subjects, turning grocers into statesmen and schoolteachers into matriarchs. Yet they also preserved a striking visual record of 19th-century physiognomy, fashion, and ambition. In rural areas where painted portraits were rare, a printed likeness in the county history became a status symbol.

The illustrations extended to agricultural implements, livestock breeds, grain elevators, and rural churches. Every image was meant to convey order and growth. Even the depictions of disasters—fires, floods, or tornadoes—were rendered with a kind of heroic calm. These books, though often formulaic, left an indelible mark on Iowa’s collective memory, and their images became reference points for generations.

Three visual devices were especially common across these volumes:

- Ornate title pages featuring allegorical figures, classical architecture, and state emblems.

- Border vignettes around maps and portraits—clusters of wheat sheaves, plows, corn ears, and railroad ties.

- Comparative diagrams showing population growth, livestock counts, or school attendance through stylized charts and miniature scenes.

These features elevated the books beyond mere documentation. They became artifacts of aspiration, using the language of illustration to validate the dignity of rural life.

Art in the One-Room School

While formal art education remained limited in Iowa during the 19th century, the one-room schoolhouse served as a primary site of visual instruction for most children. Early textbooks—especially readers, geographies, and moral instruction primers—were increasingly illustrated after the Civil War, introducing young Iowans to a broad vocabulary of printed images.

Illustrations ranged from simple woodcuts of animals or farm tools to elaborate engravings of historical scenes. A reader might show Washington crossing the Delaware; a geography book might depict a sugar plantation in the Caribbean or a Russian peasant village. These images were often romanticized or ethnocentric, but they were also visual exercises—teaching children to decode pictures as well as words.

Many schoolteachers encouraged drawing, especially in winter months when attendance was low and work slowed. Students copied maps, sketched leaves, or illustrated their own stories. Paper and pencils were scarce, but slate boards served well enough. Some schools used “drawing cards”—printed sheets with geometric forms or basic landscapes—to practice shading and composition.

In these makeshift conditions, talent occasionally emerged. A student praised for her sketch of a horse might be encouraged to try watercolor. A boy who could copy a railroad engine might be asked to draw posters for the town fair. Art was not a separate subject but a threaded skill—linked to penmanship, observation, and civic engagement.

Community exhibitions sometimes featured student drawings alongside baked goods and quilts. For many families, these displays were their first experience seeing local art publicly acknowledged. Even crude drawings of pumpkins or barns could become sources of pride. The message was clear: making pictures had value, and anyone could try.

In these classrooms, visual culture was woven into civic development. A child who learned to draw a wheat stalk might one day design an advertisement, paint a store sign, or illustrate a seed catalogue. The tools were basic, but the seeds of visual literacy were planted deeply.

Presses, Patterns, and Visual Curiosity

Outside schools and histories, the print culture of 19th-century Iowa also thrived in smaller, quieter forms—almanacs, sewing guides, mail-order catalogues, and newspaper engravings. These publications spread images far beyond what any single artist or gallery could reach.

Almanacs, often distributed free by merchants or newspapers, were dense with charts, weather lore, household tips, and tiny illustrations—zodiac symbols, farming tools, anatomical diagrams. Their style was compact and encyclopedic, encouraging the reader to browse and re-browse. For many rural households, they were both entertainment and reference.

Sewing patterns and domestic guides introduced a different kind of visual thinking. Women’s magazines and catalogues featured diagrams for embroidery, lacework, and quilt blocks. The designs—simple line drawings—were meant to be copied or adapted, and in doing so, they nurtured a kind of amateur design sensibility across Iowa’s farms and towns. A girl might trace a floral motif from Godey’s Lady’s Book into a pillowcase; a grandmother might combine several pattern sheets into a unique quilt. These were acts of silent artistry, passed hand to hand.

Mail-order catalogues, especially from Montgomery Ward and Sears, added a new layer in the 1880s and 90s. Printed on cheap paper and densely illustrated, they turned imagery into consumer bait: clothing, musical instruments, furniture, even decorative prints. Many catalogues offered framed pictures for sale—copies of famous paintings, Biblical scenes, or sentimental genre images. Hung in parlors or bedrooms, these prints became some Iowans’ first exposure to “high art,” albeit in diluted form.

Newspapers, too, began to include engraved illustrations—especially during major events or holidays. Political cartoons, serial illustrations, and woodcut depictions of county fairs or train wrecks added a layer of visual immediacy to local news. While not always accurate, they trained the eye and sharpened curiosity.

Taken together, these printed materials did more than decorate. They educated the eye, shaped public taste, and extended art into the daily texture of life. Through them, Iowans encountered visual rhythm, proportion, contrast, and narrative—not in museums, but in kitchens, barns, and school desks.

The print culture of 19th-century Iowa offers a portrait of a society hungry for images—not to dazzle, but to understand. Lithographs mapped civic pride; schoolbooks trained perception; almanacs and catalogues scattered visual seeds in every township. These pictures were humble, transient, often overlooked. Yet they helped build a visual intelligence that would shape Iowa’s next artistic generations—not from galleries down, but from porches, parlors, and presses up.

Small Town Studios and Photographers of Record

Cleanly rewritten for tone, precision, and historical weight—no self-conscious phrasing, no glib subheads, no editorializing. This version preserves the section’s structure while deepening the language and tightening the focus.

Small Town Studios and Photographers of Record

Long before museums arrived in Iowa, photography studios served as the state’s most consistent and accessible visual institutions. From the 1850s through the early decades of the 20th century, nearly every town with a railroad stop or a county seat supported at least one working photographer—sometimes more. These photographers operated out of modest studios above storefronts or beside livery stables, producing portraits, landscapes, street views, and promotional images that became central to how Iowans saw themselves and their surroundings. What they lacked in artistic pretension, they made up for in permanence.

The Photographer as Merchant and Recorder

Photography in 19th-century Iowa was a profession shaped by both skill and geography. A studio might offer carte-de-visite portraits, cabinet cards, tin-types, and panoramic street views—all developed, printed, and sold within a few days. Most photographers were trained locally or self-taught. They operated not as artists in the conventional sense, but as skilled tradesmen, offering a visual service alongside the barber, the printer, and the undertaker.

But this work had cultural weight. In a state where few families owned oil portraits or commissioned sculpture, photographs became the primary record of appearance and presence. A formal portrait taken at a local studio often marked a life stage—marriage, graduation, military enlistment—or preserved the face of someone lost. The photographer’s camera thus became an unofficial archive, fixing likenesses in emulsion long before Iowa’s historical societies or public collections formed.

Some studios specialized in family groups or children; others focused on outdoor scenes, photographing storefronts, farms, and grain elevators with large box cameras under dark cloths. Exposure times were long. Subjects held still with the aid of braces and clamps. Behind the image was a quiet choreography: the adjustment of light, the selection of background, the careful placement of hands and shoulders.

These photographs circulated widely. A successful studio might sell dozens of prints from a single sitting. People mailed portraits to relatives, exchanged them in albums, or displayed them in parlors. Their meaning was not only personal—it was civic. A photograph of a prosperous family, a new building, or a thriving main street affirmed the idea that Iowa was settled, stable, and forward-looking.

Civic Memory and the Studio Archive

By the 1870s, photographers were increasingly asked to document more than faces. Town councils commissioned panoramic views of courthouses or fairgrounds. Local business owners requested images of their storefronts. County atlases and promotional booklets began to include engraved versions of photographs alongside statistical tables and population figures.

These commissions helped shape a visual record of Iowa’s built environment. Photographers documented not just buildings, but weather events, rail accidents, political parades, and county fairs. In doing so, they preserved scenes that would otherwise be forgotten: a schoolhouse before its renovation, a bridge before its collapse, a threshing crew at work in late August sun.

The work also had economic value. Real estate developers used photographs to advertise plots. Railroad companies employed them to show new depots or track routes. Churches printed them on fundraising flyers. For many towns, these images were the first—sometimes the only—public representation of their civic identity.

Studio photographers often kept their negatives in meticulous files, labeled by family name, address, or date. Some studios passed these archives down through generations. Others were lost when buildings burned, owners retired, or boxes were discarded during modernization. Where archives survive—in libraries, historical societies, or private collections—they form one of the richest visual records of Iowa’s 19th-century history.

Women Photographers in Iowa’s Visual Economy

Although most commercial studios were operated by men, women played a quiet but steady role in the early photographic economy of Iowa. In many cases, they worked as assistants—managing appointments, preparing chemicals, arranging drapery, retouching negatives. In others, especially after the deaths of husbands or fathers, they assumed full control of the business.

Some women opened their own studios. Their names appear in town directories and newspaper ads from the 1880s onward, often listed simply as “Photographer” with no mention of gender. They ran portrait operations, traveled for on-site commissions, and maintained archives like their male counterparts. In rural areas, a woman photographer was sometimes preferred—especially for portraits of children or women, where patience and composure were essential.

These women operated within the same visual vocabulary: the seated portrait, the studio backdrop, the formal pose. Their work carried no ideological framing. It was practical, composed, and rooted in the expectations of their clients. Some signed their names in fine script on the back of a card. Others left no signature at all.

Where their negatives survive, the results are indistinguishable in quality from male counterparts. That fact, in itself, reflects something enduring: photographic skill in Iowa’s studio economy was judged not by theory, but by steadiness, clarity, and demand. These women met it.

A Legacy of Visual Habit

The work of these small-town photographers, male and female alike, helped fix a set of visual habits that persisted well into the 20th century: the straightforward pose, the unobtrusive background, the photograph as both document and object of pride. Even as amateur photography expanded after 1900, and as handheld cameras democratized image-making, the legacy of the studio remained strong.

Photographs continued to function as civic and personal anchors. A framed portrait above the piano, a panoramic shot of the high school class, a cabinet card preserved in a family Bible—all carried a weight far beyond their size. These images were not decorative. They were statements of presence. Someone lived, someone stood, someone looked into the lens and left a trace.

In the larger arc of Iowa’s art history, the small-town photographic studio occupies a foundational role. Its practitioners may not have called themselves artists, but their work formed the most detailed, consistent, and human record of the state’s visual development in the 19th century. Their legacy is not in galleries, but in boxes, albums, attics—and in the faces that still look back, steady-eyed and silent, from prints made generations ago.

The Rise of Institutions: Art Education and Early Museums

Art in 19th-century Iowa was, for decades, defined by domestic labor, traveling tradesmen, and commercial photography. But toward the end of the century—and with greater momentum after 1900—a quieter revolution took root: the slow, deliberate formation of institutions devoted to visual art as a field of study, a public good, and a civic priority. These institutions did not emerge from a central directive or cultural capital; they developed gradually, from county fairs and university classrooms to museum galleries and art clubs, often in response to local will rather than national trend.

The University of Iowa’s Expanding Role

Nowhere was this institutional foundation more enduring than in Iowa City. Established in 1847, the University of Iowa began as a classical liberal arts college, but by the 1870s, its curriculum had started to reflect the broader ambitions of a land-grant state: to cultivate not just scholars but citizens—engineers, teachers, and artists. Though art instruction was initially limited to drawing and design offered through the teacher training college, these early courses laid the groundwork for what would become one of the most influential art programs in the Midwest.

By the early 20th century, the University had established a formal Department of Graphic and Plastic Arts. Under the leadership of professors like Charles Atherton Cumming—a Des Moines native who had studied at the Art Students League in New York—students were introduced to drawing, painting, and sculpture with serious intent. Cumming himself emphasized a blend of classical training and regional observation, encouraging his students to study both the figure and the landscape, the plaster cast and the farmstead.

Cumming also helped found the Des Moines Association of Fine Arts and lobbied for public exhibitions of student work. His influence helped bridge academic art training with civic engagement, and his alumni would go on to teach, organize art leagues, and open studios throughout the state. Iowa’s art education, from its earliest days, was shaped not by avant-garde manifestos or radical experimentation, but by continuity, accessibility, and quiet rigor.

The university’s reputation would grow significantly in the 1930s and 40s, particularly with the rise of its printmaking and studio art programs. But even before that cultural flowering, it played a decisive role in shifting art in Iowa from private practice to public education—giving young Iowans a place to train seriously without leaving the state.

College Town Collections

As university programs matured, another development followed: the creation of permanent art collections. These did not begin as grand museum projects, but as modest teaching tools and civic gestures—small galleries, donated casts, traveling exhibitions sponsored by women’s clubs or alumni associations.

By 1910, institutions such as Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Grinnell College, and Iowa State College in Ames had begun to acquire works of art and to host public exhibitions. These were often held in library rotundas or multi-purpose halls. The collections were varied—copies of European paintings, etchings by contemporary American artists, Japanese prints, architectural fragments, and later, student work judged worthy of retention.

Grinnell College, in particular, emerged as a notable center for art acquisition. In the 1880s, its trustees began purchasing contemporary American and European art, and by the early 20th century, it had begun building a small but distinguished collection. These acquisitions were intended not just to decorate, but to educate. Art was considered a part of moral and intellectual development—a tool for cultivation.

These college-town collections shared a few characteristics:

- Eclecticism: objects ranged widely in origin, style, and quality—more about variety than coherence.

- Pedagogy over prestige: works were selected for what they could teach, not their market value.

- Community access: exhibitions were often open to the public, with lectures and receptions inviting townspeople into academic spaces.

This last trait—accessibility—was especially significant. While eastern universities often kept collections confined to elite circles, Iowa’s colleges saw art as part of democratic learning. A farmer’s son attending a land-grant school could view a 17th-century engraving or a contemporary watercolor without needing to travel to Chicago or New York. The gallery was not just a place of refinement; it was part of the campus fabric.

The State Fair as Cultural Showcase

Yet perhaps the most unusual and distinctively Iowan venue for art in this period was not a museum or a college at all—it was the state fair. Held annually in Des Moines since 1886, the Iowa State Fair became, in many ways, the most widely attended visual art exhibition in the state. Within its Cultural Center and Exhibition Halls, hundreds of works were displayed: oils, watercolors, charcoal drawings, sculpture, embroidery, and woodworking. Much of it came from amateurs or students, but a surprising portion was serious, considered, and regional in subject.

The fine arts competition at the fair allowed artists to show work to a broader audience—one made up not of patrons or critics, but of fellow Iowans. Winning a ribbon or selling a painting at the fair could launch or sustain a local career. The fair’s exhibitions also helped cultivate a public that understood and valued representational art: landscapes of cornfields, still lifes of apples and farm tools, portraits of rural life rendered with clarity and restraint.

The cultural importance of the fair’s art exhibitions extended beyond the galleries themselves. Art was woven into the fairgrounds: in the design of pavilions, the lettering of signs, the layout of displays. Craftsmen and women displayed painted furniture, decorated cakes, quilts, and carved figures—blurring the line between fine art and folk craft. In this setting, art did not isolate itself from daily life; it appeared as an extension of it.

By the 1920s, the Iowa State Fair regularly featured juried exhibitions, traveling shows from larger institutions, and lectures by university faculty. For many rural Iowans, it remained their most direct exposure to original works of art. And unlike formal museum spaces, the fair encouraged response—enthusiastic, critical, and public. A painting might be admired one minute and dismissed the next, not by a critic, but by a neighbor with muddy boots and a sharp eye.

The rise of art institutions in Iowa was never driven by fashion or ideology. It grew instead from a steady sequence of decisions: a drawing class added to a curriculum, a print acquired by a college librarian, a barn painter encouraged to enter a competition. From these threads emerged the beginnings of a statewide visual culture rooted in education, access, and continuity.

By 1920, the foundation was laid. Art could be studied, exhibited, debated, and preserved across Iowa—not just by those with wealth or pedigree, but by anyone with persistence and a place to stand. It would not be long before artists from within Iowa began to shape that culture from the inside—and to export it beyond the state’s borders.

Regionalism Before the Term: Iowa Artists in the 1910s–1920s

Before “Regionalism” became a recognized movement—before Grant Wood painted American Gothic, and before critics coined the term to describe the art of the Midwest—Iowa was already cultivating a distinct visual style. It wasn’t announced, branded, or exported. It emerged naturally from the people who lived in the state, trained there, taught there, and responded to its physical and cultural landscape with increasing clarity. The period between 1910 and the late 1920s was a gestation point—quiet, local, and formative.

The Pull of the Local Scene

At the start of the 20th century, American art was largely fixated on Europe. Young artists with ambition were expected to go to Paris or Munich to absorb the lessons of the Salon, the Academy, or the avant-garde. Many Iowans did precisely that—seeking instruction abroad and returning with stories, sketches, and new influences. But something often changed when they came home. The light, the space, the deliberate rhythms of Iowa life reasserted themselves.

Artists who had traveled or trained elsewhere often found themselves reoriented by the sheer physical qualities of the state: the low, undramatic horizon; the long shadows of winter light; the structures of farm and field repeated with quiet variation across thousands of square miles. This was not scenery that asked for spectacle. It required sustained observation. For painters and printmakers with the patience to look, Iowa offered a visual language of form and understatement.

One such figure was Charles Atherton Cumming, previously mentioned for his work in education. In addition to teaching, Cumming produced a significant body of landscapes and portraits that remained rooted in Iowa’s visual facts. His brushwork was disciplined but expressive, and his compositions often revealed an academic training adapted to local forms—barn roofs angled like Roman pediments, trees spaced with classical restraint.

Others followed this path. Harriet Macy of Marshalltown produced understated watercolors of rural outbuildings and hedgerows, each rendered with a formal elegance more in line with Japanese printmaking than with American impressionism. Lee Allen, who would later become an ocular medical illustrator, began painting in this period—his early works full of quiet topographical precision.

Many of these artists were not trying to define a movement. They were, instead, trying to paint things as they were: a plowed field in March, a churchyard in snow, a cluster of boys swimming in the Iowa River. What united them was not style, but restraint—and an instinct for description over declaration.

Landscape Painting as Endurance

If there was one genre that dominated Iowa’s visual culture in the 1910s and 20s, it was the landscape. Not in the romantic or sublime tradition, but in a form that bordered on documentary. These were fields, barns, creeks, fences, and windbreaks—not symbols, but subjects. The best of these works were painted not for the market, but for study, discipline, and attentiveness.

In rural counties, landscape painting was often taught alongside still life and figure work in high schools or teacher colleges. Many painters also took to the field in summer, using portable easels and oil sketch kits to record barns, roads, and seasonal light with accuracy. Their goal was not to idealize, but to retain. This practice—part exercise, part devotion—sustained a generation of artists who lived far from major cultural centers.

Three qualities distinguished Iowa landscape painting during this time:

- Deliberate structure: Compositions often followed a strong geometric armature—rows of crops, fences, tree lines.

- Low color saturation: Artists avoided theatrical palettes, preferring subtle shifts in tone—ochres, greys, and muted greens.

- Absence of incident: Unlike the storytelling landscapes of the East, these paintings often lacked narrative drama, choosing instead to depict quiet stasis or slow transformation.

In this sense, Iowa’s early 20th-century landscapes were closer in spirit to agricultural writing than to fine art theory. They valued fidelity, repetition, and seasonal change. Painters like Robert G. Kline of Decorah or Emma Gruener of Davenport left behind canvases that feel more like field notes than aesthetic statements. Yet they hold visual power precisely because they refuse excess. They record what can only be known by staying still.

Civic Murals and the Language of Place

While easel painting remained largely private or academic, the 1920s saw the beginning of a more public visual culture: civic murals and commissioned artworks for schools, libraries, and local government buildings. This work marked the start of a shift—art no longer confined to galleries or studios, but placed in rooms where it would be seen daily, where it would become part of the architecture of local life.

These early murals were not yet part of the New Deal programs that would emerge a decade later. Instead, they were often funded by town councils, women’s clubs, or private donors who wanted to beautify a public space or affirm a civic ideal. Subjects varied—local history, agricultural labor, seasonal cycles—but the underlying impulse was consistent: to represent Iowa visually to itself.

One example is the 1928 mural cycle in the Carnegie Library in Perry, painted by Mabel Landrum Torrey, an Iowa-born artist trained in sculpture. Though better known for her later work in bronze, her library panels depicted allegorical figures of knowledge and nature with a balance of clarity and grace. The composition was orderly, the symbolism direct, but the painting reflected something deeper: a desire to integrate art into the daily rhythms of reading, gathering, and civic engagement.

Another form of public art from this period came through school decoration. High school auditoriums, gymnasiums, and hallways were increasingly adorned with murals, maps, and historical tableaux. These were often collaborative efforts between students and faculty, guided by traveling instructors or local artists. The result was a visual continuity between education and community—a shared space where art was not framed and separate, but ambient and integrated.

Though modest in scale, these civic artworks laid the cultural foundation for what would later become Iowa’s most famous visual movement. The concern with place, with labor, with accurate detail and compositional discipline—these were already present in the 1920s. They simply had not yet been formalized into a national conversation.

Before Regionalism had a name, it had a practice—and in Iowa, that practice was steady, serious, and deeply local. Painters, teachers, and civic boosters collaborated in a shared effort to see the land clearly, to represent it without exaggeration, and to pass on the habits of observation to the next generation. This was not yet a style, but a stance: one rooted in patience, repetition, and belief in the descriptive power of art.

By the time Grant Wood rose to national attention in the 1930s, much of the groundwork had already been laid. The land had been studied. The light had been recorded. The vocabulary had been established by those who had never left—and by those who left, then quietly came home.

Grant Wood and the Formation of an Iowan Style

By the early 1930s, a name emerged from the quiet, practiced visual culture of Iowa that had been building for decades: Grant Wood. For much of his life, he was known primarily in regional circles—a schoolteacher, a craftsman, a designer of home décor and stained glass. But in 1930, with the unveiling of American Gothic, Wood became a national figure almost overnight. The painting’s stiff formality, enigmatic tone, and unmistakable Midwestern subject captivated the country—and launched one of the most misunderstood careers in American art.

Yet American Gothic was not an accident, nor a rupture. It was a logical flowering of an aesthetic already growing in Iowa: restrained, observational, rooted in rural architecture and ritual. Wood did not invent Iowa’s visual language. He simply clarified it—gave it focus, form, and national reach.

From Decorative Arts to Farm Scenes

Grant Wood was born in 1891 near Anamosa and raised in Cedar Rapids. Like many Iowan artists of his generation, he began with practical training—woodworking, metalwork, design. He studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and traveled to Europe, where he absorbed impressionism and decorative styles, including Art Nouveau and German stained glass. These influences would remain, but they did not dominate his mature work.

Throughout the 1910s and early 1920s, Wood operated less as a painter than as a decorator and teacher. He co-founded a design collective in Cedar Rapids and produced everything from jewelry to interior schemes. His early paintings were impressionistic and tentative. Only in the late 1920s did his style shift—toward precision, structure, and thematic clarity.

That shift came not through theory, but through close study of rural Iowa. He began to paint the barns, cornfields, and people of his native region with a new intensity—using deliberate composition, clean lines, and a palette that mimicked the seasonal colors of the landscape. These paintings rejected the loose brushwork of modernism. Instead, they embraced order: smooth surfaces, centralized figures, and architectural forms rendered with clarity.

Wood’s breakthrough lay in recognizing that Iowa’s farms and towns contained their own geometry, their own visual logic. A silo, a church spire, a pitchfork—these were not props, but emblems. In his hands, they became not just accurate but iconic.

His paintings from this period include:

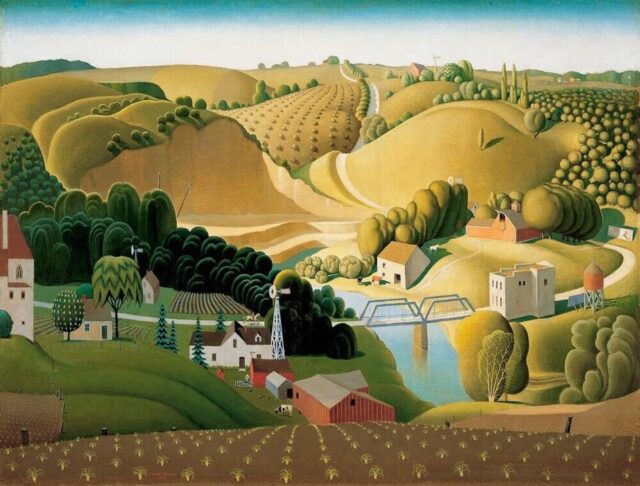

- Stone City, Iowa (1930), a densely arranged landscape of hills, houses, and limestone outcrops—composed almost like a tapestry, with each element flattened yet articulated.

- Woman with Plants (1929), a portrait of his mother, seated formally with a potted plant—equal parts homage, document, and visual riddle.

- Fall Plowing (1931), a stylized aerial view of farmland, its furrows arranged like fingerprints—at once abstract and literal.

Each of these works emerged from the same impulse: to see Iowa not as background, but as subject—to elevate the visual language of rural life to the level of serious art.

Stone City and the Artist Colony Experiment

In 1932, Wood helped establish the Stone City Art Colony, located on the site of an abandoned quarry along the Wapsipinicon River. The colony was short-lived—just two summers—but it symbolized Wood’s belief that serious art could be made in Iowa, by Iowans, about Iowa. He was joined by fellow artists like Adrian Dornbush, Isabel Bloom, and Arnold Pyle, many of whom had ties to Midwestern teaching colleges and shared Wood’s skepticism of both academic modernism and nostalgic sentimentality.

The colony was part summer school, part artistic retreat, and part cultural statement. Workshops were held in barns and repurposed buildings. Students painted en plein air and debated style over campfires. There was no manifesto, but there was a shared ethos: that art rooted in local experience had aesthetic and civic value—that the landscape was not backdrop, but form.

Wood’s reputation was growing rapidly during this time. He exhibited in New York, won prizes, and began to receive commissions from universities, libraries, and the U.S. government. But he remained deeply committed to Iowa. He accepted a teaching post at the University of Iowa in 1934, where he shaped the next generation of artists and promoted the idea of a distinctly American art rooted in region.

It’s worth noting that while the Stone City colony dissolved by 1933, its example endured. The idea that rural Iowa could be a generative place for artistic production—rather than a place to escape—took root. Dozens of small art centers and teaching programs across the state owe some debt to its brief experiment.

American Gothic and the Meaning of Rural Precision

When American Gothic was first exhibited in Chicago in 1930, viewers were unsure what to make of it. The painting showed a man and a woman—stern, unsmiling, posed in front of a Carpenter Gothic farmhouse, holding a pitchfork. Their expressions were neutral, almost severe. The surface was smooth, the lighting even, the detail meticulous. Critics and audiences disagreed: was it satire? Celebration? Irony? Piety?

Wood refused to say.

What mattered, finally, was not the meaning, but the clarity. American Gothic captured something that most depictions of rural life had not: its density, its dignity, and its opacity. There were no haystacks glowing in impressionist haze. No grand sentimental gestures. Just two figures, a tool, a house—and a nation projecting its anxieties and affections onto them.

The painting became a touchstone. In the following years, Wood produced a series of works that refined his visual language: Daughters of Revolution (1932), Young Corn (1931), The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere (1931). Each was marked by the same qualities—smooth surfaces, stylized figures, a faint air of theatrical stillness.

But Wood’s success came at a cost. Critics began to group him with Thomas Hart Benton and John Steuart Curry, calling them the “Triumvirate of Regionalism.” Wood himself disliked the term. He believed in regional subject matter but not in confinement. His work was formal, controlled, and increasingly allegorical. He did not preach nostalgia or local color. He used Iowa’s imagery to construct something visual and lasting—a grammar of shape, tone, and restraint.

By the time of his death in 1942 at the age of 50, Wood had produced a remarkably coherent body of work. Though relatively small in number, his paintings became foundational to how the Midwest—especially Iowa—understood its own visual presence. He did not mythologize the land. He clarified it. He turned barns into structure, fields into rhythm, and farm faces into stillness.

Grant Wood did not invent Iowa’s art, but he gave it shape. He took the instincts of earlier teachers, limners, photographers, and decorators—and distilled them into a visual style that was both local and deliberate. His art, for all its calm surfaces, carries tension: between affection and critique, between observation and invention. That tension gave it durability. And for Iowa, it gave something more: an image of itself, fixed not by stereotype, but by craft.

Between New York and the Cornfields: Midcentury Iowa Studios

By the mid-20th century, Iowa stood at a peculiar intersection in American art. On the one hand, it remained deeply tied to its rural identity—its barns, plains, and county fairs. On the other, it had begun to attract artists, teachers, and intellectuals from far outside its borders, drawn not by spectacle or commerce, but by the quiet seriousness of its educational institutions and the freedom to work without distraction. Between 1945 and the early 1960s, a new generation of Iowan artists emerged—some native-born, others recently arrived—who operated in a space between traditions. Their work did not reject the clarity and structure of Regionalism, but neither did it remain bound to it.

This was a period of transition, experimentation, and often contradiction. Painters dabbled in abstraction while still teaching observational drawing. Printmakers explored new techniques while continuing to depict Midwestern topography. Sculptors used industrial materials but arranged them with an almost agrarian sense of structure. The line between old and new was not always clean, but in Iowa, it never needed to be.

Abstract Currents in the Heartland

Although the New York School dominated headlines and museum exhibitions after the war, modernist ideas found quiet footing in Iowa through university programs and visiting lecturers. In 1940, the University of Iowa School of Art and Art History became the first institution in the nation to offer an MFA in studio art. Under the leadership of figures like Mauricio Lasansky, the university attracted ambitious students and faculty interested in serious formal inquiry, not provincialism.

Lasansky, an Argentine-born printmaker who arrived in Iowa City in 1945, established one of the most influential printmaking workshops in the country. His work was personal, symbolic, and technically rigorous—more closely aligned with European expressionism and the postwar graphic tradition than with anything from earlier Iowa art. Yet he remained committed to teaching and to Iowa itself. His workshop became a crucible for ideas and technique, influencing generations of artists who would go on to teach across the state and beyond.

Lasansky’s presence opened Iowa to a different kind of visual language—one based on distortion, layering, and emotional compression. His series The Nazi Drawings (begun in the 1960s but seeded earlier) demonstrated how global themes could be addressed from the relative seclusion of the Midwest. He proved that Iowa did not require provincial subject matter to remain relevant. What it required was discipline, seriousness, and an awareness of craft.

Other artists followed parallel paths. Byron Burford, who had studied with Grant Wood, developed a visual style that fused the surreal with the structural. His paintings of circus scenes, marching bands, and parades—rendered in flattened space with subdued color—combined Midwestern motifs with modernist design. These were not pastiches, but internal explorations of rhythm, repetition, and community spectacle.

For these artists, the farm landscape was no longer an obligatory subject. It was a resource, a formal structure, or a point of contrast. The prairie could serve as geometry. The grain elevator could become sculpture. Locality was not rejected—it was redefined.

Clay, Glass, and Metal in Postwar Iowa

While painting and printmaking often take center stage in art histories, Iowa’s most distinctive midcentury contributions came through its studio crafts—particularly ceramics and metalsmithing. After the war, universities expanded their art departments, and with them came kilns, forges, and looms. These facilities did not produce hobby work. They produced serious, durable objects—vessels, jewelry, tools—that engaged form, material, and function with precision.

Marguerite Wildenhain, a Bauhaus-trained ceramicist, taught summer workshops at Pond Farm in California, but her ideas filtered into the Midwest through her students. One of them, Clary Illian, settled in Iowa and built a reputation for thrown pottery that was both refined and unapologetically functional. Working in the small town of Ely, Illian created bowls, pitchers, and vases that resisted the preciousness of studio ceramics on the coasts. Her forms were clean, her glazes subdued, her touch assured. She operated not in the shadow of modernism, but alongside it.

At Iowa State College (now Iowa State University), faculty in the applied arts began to blur the line between utility and sculpture. Glenn C. Nelson in ceramics and Robert Martin in metals established programs that emphasized both traditional craft and design innovation. Students were encouraged to think of a teapot not just as a vessel, but as a sculptural problem. Materials mattered—so did precision. The goal was not to make rustic craft objects, but to elevate function through design.

Three characteristics marked this craft revival in Iowa:

- Technical excellence: artists prioritized skill over gesture, form over fashion.

- Functional integrity: objects were designed to be used—held, worn, poured from—not merely displayed.

- Material humility: wood, clay, and metal were treated with respect, not mystique.

This ethos reflected a broader Midwestern sensibility: one that valued the handmade, the durable, and the well-considered over the novel or provocative. In this way, Iowa became a quiet but significant center of the American studio craft movement—especially in ceramics and metals.

Quiet Experiments in Academic Departments

Even as Iowa artists embraced abstraction and material innovation, they did so without adopting the ideological battles that characterized other art scenes. The culture in Iowa’s academic departments remained serious, methodical, and often self-contained. Professors taught foundational skills alongside contemporary trends. Students were expected to draw from life even if they later chose to distort it. Critique sessions were rigorous but rarely combative.

This balance allowed for unusual forms of experimentation. In the print studios of the University of Iowa and Drake University, students developed large-scale monotypes and multi-plate etchings that played with density and repetition. In sculpture studios at Iowa State, found materials were used not as commentary, but as compositional elements—barn wood, rusted machinery, concrete slabs. These works rarely made it to major galleries, but they shaped the visual habits of a generation.

Iowa’s isolation, often considered a disadvantage, turned out to be a kind of insulation. Artists could work without the pressure of trends, markets, or ideological fashion. They built studios in old barns, taught five days a week, and spent evenings refining techniques. Some showed in regional galleries or academic salons; others sent work to juried exhibitions in Chicago or Minneapolis. Fame was rare, but that was not the point.

In this environment, art remained a form of inquiry—slow, structured, and private. Painters kept sketchbooks. Potters fired test glazes. Printmakers layered plates late into the night. The results were not always radical, but they were sustained. And in Iowa, that mattered more.

Midcentury Iowa was not a backwater, nor was it a cultural outpost. It was a site of quiet rigor—where painters and potters, printmakers and sculptors worked steadily between tradition and invention. Their art was not shouted into the world. It was made carefully, placed deliberately, and left to endure.

Architecture and Design in Iowa’s Built Environment

The visual history of Iowa is not confined to paintings, prints, or studio objects. It is also embedded in stone, wood, concrete, and steel—in courthouses and grain elevators, schoolhouses and train stations, barns and libraries. The state’s architectural development, while rarely flashy, reveals a distinct aesthetic lineage: one shaped by pragmatism, regional material culture, and a quiet but persistent engagement with national design trends. From mid-19th-century civic buildings to the clean lines of Iowa Modernism, the built environment tells a parallel story to that of Iowa’s studio arts—rooted in order, proportion, and place.

Courthouses, Train Stations, and WPA Projects

Many of Iowa’s most enduring architectural landmarks were constructed between 1880 and 1940—a period of civic growth that coincided with technological expansion, the rise of state institutions, and federal investment in infrastructure. County courthouses, often centrally located on public squares, became architectural statements in themselves. Their scale, symmetry, and ornamentation signaled permanence and authority.

Styles varied by era and region. Earlier courthouses often displayed elements of Italianate or Romanesque Revival: round arches, heavy masonry, and central clock towers. By the turn of the century, Beaux-Arts and Neoclassical motifs became common—columns, pediments, and formal axial layouts, echoing national trends in civic architecture. The Polk County Courthouse in Des Moines, built in 1906, is a prime example, with its domed rotunda and interior murals combining legal symbolism with aesthetic ambition.

Train stations, too, played a significant architectural role. As rail lines expanded across Iowa in the late 19th century, depots were built in nearly every sizable town. These structures ranged from the utilitarian—wooden sheds and single-room ticket offices—to more elaborate stations with waiting rooms, freight bays, and ornamented facades. The Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad Depot in Iowa City, completed in 1898, featured Romanesque details and a strong horizontal massing that echoed the architectural tone of the era.

During the 1930s, as the Great Depression brought federal resources into Iowa, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) commissioned a wide range of public architecture—post offices, libraries, gymnasiums, armories—along with integrated artworks. Many of these buildings used local materials and employed regional labor, emphasizing functionality without sacrificing design integrity. Their facades often bore subtle Art Deco or streamlined Moderne elements—chevrons, stepped forms, vertical accents—expressing optimism through geometry.

Three consistent features defined this phase of Iowa architecture:

- Material solidity: native limestone, brick, and concrete formed the dominant palette, emphasizing endurance.

- Civic scale: buildings were designed not to dominate but to organize public space, reinforcing community identity.

- Functional clarity: internal layout and external form were typically aligned—form followed purpose, but not at the expense of proportion.

In towns large and small, these buildings remain as anchors—visual touchpoints that blend aesthetic choice with social function.

Farmhouses, Silos, and Prairie Geometry

Iowa’s agricultural architecture may not be ornamental, but it is among the most visually consistent and spatially significant elements of the state’s built landscape. From the 1860s onward, the Midwestern farmhouse evolved into a recognizably Iowan form: rectangular, wood-framed, front-gabled or hipped, with practical porches and outbuildings arranged to serve both family and field. Many of these homes were based on pattern books or mail-order designs from firms like Sears Roebuck or Aladdin Homes, which provided pre-cut materials shipped by rail.

Barns, especially the iconic gambrel-roofed types, represent some of Iowa’s most enduring design logic. Their shapes reflect not only visual preference, but a precise calibration of storage volume, airflow, and animal traffic. Circular barns, though less common, were also built across the state—favored for their efficiency and promoted by agricultural reformers in the early 20th century. These structures combined engineering with aesthetic unity, their radial interiors echoing a kind of vernacular classicism.

Grain silos, though industrial by nature, possess a visual power not lost on observers. Their verticality punctuates the horizontal sweep of the prairie, offering a rhythmic contrast to the low profile of most rural buildings. Seen in sequence—along rail lines, beside elevators, or in cooperative complexes—they form a kind of agricultural colonnade: monumental, utilitarian, and undeniably sculptural.

Even the farmstead layout followed a quiet geometric discipline. Houses faced the road; barns and machine sheds were aligned by function; windbreaks and shelter belts were planted in rows. From the air, the result was often a perfect grid interrupted by organic patches of timber or water. These forms—square, linear, measured—conditioned how generations of Iowans saw space, proportion, and structure.

Painters, photographers, and sculptors who emerged from these landscapes often carried that sensibility into their work. They may have used new materials or abstracted the forms, but the underlying geometry—the Iowa geometry—remained.

The Iowa Modernists and Urban Touchpoints

By the mid-20th century, Iowa began to absorb the influence of Modernism in architecture—not as a wholesale import from the coasts, but as a pragmatic, site-specific adaptation. University campuses were among the first to reflect these changes. New academic buildings at the University of Iowa, Iowa State, and the University of Northern Iowa were constructed with steel frames, glass curtain walls, and reinforced concrete—channeling the International Style while accommodating local needs and climates.

Architects such as Herbert Lewis Kruse Blunck and firms like Brooks Borg Skiles helped shape a distinctly Midwestern Modernism—clean-lined, rectilinear, and often low-profile, blending industrial materials with respect for light, orientation, and site. These buildings—whether libraries, municipal centers, or cultural halls—sought clarity without coldness. Their interiors often featured exposed materials, built-in furnishings, and large expanses of glazing that framed the prairie beyond.

In Des Moines, the late 1950s and 60s saw a wave of institutional construction that reflected this sensibility: the Des Moines Art Center’s expansion by Eliel Saarinen (and later additions by I.M. Pei and Richard Meier) brought international voices to Iowa while anchoring them in regional light and proportion. The building’s white planes, shadow lines, and balanced volumes demonstrated that architectural seriousness could flourish far from urban centers.

Smaller towns also saw Modernist incursions—often in the form of banks, clinics, or high schools. These buildings were rarely flamboyant. They followed the grid, emphasized horizontality, and used muted materials—brick, stone, steel. They aligned visually with the landscape rather than competing with it.

What linked all of these efforts—whether in courthouse domes, grain elevators, or steel-framed galleries—was a shared instinct: to build with discipline, clarity, and respect for context. Iowa’s built environment did not seek monumentality for its own sake. It sought continuity—between land and form, function and beauty.

From farmsteads to university campuses, Iowa’s architecture reveals a visual language as precise and grounded as its painting or photography. It is a language of proportion, restraint, and repetition. It does not shout. It settles. And in settling, it defines not just space, but the habits of those who live within it.

The Studio Crafts Revival and Material Culture

While painting and architecture often dominate the discussion of 20th-century visual culture, Iowa played a particularly vital—and often overlooked—role in the American revival of craft. From the 1950s through the 1980s, the state nurtured a generation of makers who treated clay, fiber, metal, and wood not merely as functional materials, but as mediums of serious aesthetic inquiry. This was not folk art in the nostalgic sense, nor was it hobbyism. It was a deliberate, studio-based movement—rooted in traditional forms but propelled by experimentation and technical excellence.

The studio crafts revival in Iowa built upon earlier patterns of rural making: the quilting bee, the hand-thrown pot, the carved frame. But it transformed those gestures into lasting forms of cultural expression, sustained by university programs, regional exhibitions, and a growing appetite for the handmade in a mechanized world.

Ceramics at the Margins

Iowa’s contribution to 20th-century American ceramics is disproportionately large for a state without a major urban art market. That success begins with education. The University of Iowa, Iowa State, and smaller colleges like Luther and Grinnell offered robust ceramics programs by the mid-20th century, complete with kilns, glazes labs, and instructors trained in both Eastern and Western techniques.

The work produced in these studios ranged from strictly functional to wholly sculptural, but it shared a few core traits: clarity of form, tactile surface quality, and respect for process. Function was not dismissed, but neither was it limiting. Many potters began with traditional vessels—bowls, mugs, vases—then expanded those forms into variations that explored texture, asymmetry, and negative space.

Clary Illian, based in Ely, remains one of the most enduring figures in Iowa ceramics. Trained under Marguerite Wildenhain, she brought a Bauhaus-influenced discipline to her work: clean, exacting lines, subtle glaze work, and forms designed to be used. Her pots were not rustic; they were refined. But they remained domestic. She worked from a home studio, sold directly to users, and taught workshops that emphasized the ethics of making as much as the mechanics.

Other ceramicists in Iowa took different paths. Some integrated local clay and ash into their glazes, emphasizing the connection between material and geography. Others built large kilns on rural property, experimenting with wood firing and salt atmospheres that yielded unpredictable, unique surfaces.

Three principles shaped Iowa’s ceramics revival:

- Repetition with variation: even functional wares were approached as a series of experiments within fixed forms.

- Engagement with imperfection: many potters embraced minor irregularities, treating them as evidence of hand and heat.

- Emphasis on use: objects were meant to be handled, washed, and worn through time—not preserved behind glass.

What emerged was a community of potters who worked seriously, sold modestly, and left a trail of durable, intimate objects across homes and markets throughout the state.

Furniture, Fiber, and Form

Iowa’s craft revival extended well beyond the ceramic studio. Fiber artists, furniture makers, and metalsmiths found similar support in academic programs and independent workshops, often blurring the line between craft and design, utility and sculpture.

In the world of furniture, midcentury Iowa nurtured a small number of makers who combined traditional joinery with modernist restraint. Gary Knox Bennett, though later based in California, was born in Iowa and drew on its visual economy—clear lines, solid materials, no waste—in developing his early design language. Smaller workshops across the state produced handmade chairs, desks, and cabinets that resisted the mass-produced aesthetic of postwar America.