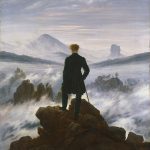

In 1505, the great German artist Albrecht Dürer created a quiet but captivating image: an oil painting of an unidentified young woman from Venice. Known today as Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman, the panel has become one of the most enigmatic and beloved works of the Renaissance. Despite its modest scale and restrained composition, it radiates a timeless elegance that continues to intrigue scholars and art lovers alike. Her expression is serene, her features delicate, and though we may never know her name, her presence endures.

What makes this portrait remarkable is not just the skill with which it was painted, but the moment it captures. It was created during Dürer’s second trip to Venice, a time of artistic transformation and cultural exchange. Venice, then one of the richest cities in Europe, was bursting with color, opulence, and innovation. For Dürer, who hailed from the more reserved environment of Nuremberg, it was an eye-opening experience—one that left a deep mark on his style.

The portrait reflects more than just a pretty face. It showcases Dürer’s growing engagement with Italian ideals of beauty, proportion, and grace. The sitter’s hairstyle, clothing, and calm expression all reflect Venetian fashion and taste around 1505. Yet, there is also a sense of personal intimacy in the work, suggesting it may not have been just a formal commission, but something more thoughtful.

This simple portrait captures an intersection of two powerful art worlds—the Northern Renaissance’s detail and discipline, and the Southern Renaissance’s warmth and sensuality. It marks a point where Dürer didn’t just absorb Italian influence; he began to harmonize it with his own artistic vision.

Who Was Albrecht Dürer? A German Master Abroad

Albrecht Dürer was born on May 21, 1471, in Nuremberg, a prosperous city in the Holy Roman Empire known for its metalworking and publishing industries. He was the third of eighteen children and the son of a goldsmith, also named Albrecht. Initially trained in his father’s craft, Dürer shifted his focus to painting and printmaking, becoming an apprentice to the Nuremberg painter Michael Wolgemut at age fifteen. This early training exposed him to the intricacies of woodcut printing and the world of illustrated books.

By the 1490s, Dürer had already traveled widely through Germany and the Low Countries, gaining exposure to different artistic styles and techniques. In 1494, he made his first trip to Italy, visiting Venice and likely Padua. There, he encountered the classical influence and naturalism of Italian art, especially the works of Andrea Mantegna and Giovanni Bellini. This journey profoundly impacted his thinking, though it wasn’t until his second trip to Venice in 1505 that Italian styles would fully bloom in his work.

Dürer’s 1505–1507 visit to Venice came at the height of his career. He was already well-known across Europe for his engravings, including the Apocalypse series (1498) and Melencolia I (1514). His fame earned him commissions and friendships among the Venetian elite. He was welcomed by the painter Giovanni Bellini, who reportedly admired Dürer’s work despite their different backgrounds. Dürer also wrote about his experiences in Venice in letters to friends back home, describing the city as a place of beauty and artistic excellence.

By the time he created Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman, Dürer had reached a point where he could seamlessly blend the German and Italian traditions. He wasn’t merely borrowing from the Italians—he was participating in their dialogue. This portrait shows just how much he had matured as an artist capable of expressing both technical brilliance and emotional subtlety.

A Glimpse of Venice: The 1505 Context

Venice in 1505 was a flourishing republic, unrivaled in maritime trade and cultural achievement. Its strategic position on the Adriatic made it a gateway between East and West, and its wealth was reflected in its grand architecture, luxurious fashions, and vibrant arts scene. The city’s government was stable, its merchant class powerful, and its devotion to beauty woven into daily life. For Dürer, this was a world far removed from the more restrained and guild-dominated environment of Nuremberg.

The Venetian art scene at the time was dominated by the Bellini family, Giorgione, and the emerging young painter Titian. These artists were known for their use of rich color, soft modeling, and atmospheric light. Venice’s painters favored oil over tempera, creating works that glowed with warmth and realism. Dürer’s exposure to this style challenged his own training in detailed linework and engravings, pushing him to experiment with new techniques, especially in painting and portraiture.

Venetian society also influenced how women were depicted in art. Unlike in Northern Europe, where portraits often emphasized piety or family status, Venetian female portraits leaned toward sensuality and elegance. Women were often shown with carefully styled hair, fashionable garments, and an air of self-possession. This approach likely shaped how Dürer saw and portrayed the young woman in his painting, capturing not just her likeness but her cultural identity.

During his 1505 stay, Dürer also completed the Feast of the Rose Garlands, a large altarpiece commissioned by the German merchants in Venice. This work helped solidify his reputation among Italians, showing that a German could master their visual language. But the more intimate works, like the Young Venetian Woman, tell us even more about what Dürer observed and valued. They reveal his private curiosity and his eye for the subtleties of everyday beauty.

The Portrait: Details That Captivate

Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman is painted in oil on a small wood panel—likely linden or poplar—measuring about 32 by 24 centimeters. The young woman is shown in three-quarter view, looking gently to the left, with her head slightly tilted. Her lips are full and closed, her eyes lowered, and her skin rendered with astonishing softness and detail. Dürer’s brushwork here is quiet, refined, and deeply expressive.

One of the most captivating elements of the portrait is the sitter’s hair. Carefully arranged in coiled braids, it reflects the high-fashion hairstyles of Venetian women at the time. The auburn tones of her hair are rendered with layered glazes and careful highlights, giving her face a warm glow. Her forehead is prominently high—considered a mark of beauty in the early 16th century—and her delicate features are composed with idealized symmetry.

Her attire is subtle yet elegant. The neckline of her dress reveals just enough to suggest grace without ostentation. The fabric appears soft and finely made, rendered with restrained yet precise strokes. There’s no ornate jewelry or elaborate background—just the neutral backdrop and her poised figure, allowing the viewer to focus entirely on her presence and demeanor.

What makes this portrait so compelling is the sense of life and stillness it simultaneously conveys. The woman appears calm, reflective, perhaps even wistful. Her gaze doesn’t meet ours, yet we feel drawn into her world. Though simple in its composition, the painting feels complete in mood and character. It’s not just a likeness—it’s an emotional encounter, frozen in time.

Notable Features in the Portrait:

- Delicately modeled facial features with soft shadowing

- Coiled Venetian hairstyle with fine brush detailing

- Subtle auburn tones achieved through glazes

- Simple dress with modest yet stylish neckline

- Neutral background to enhance focus on the sitter

The Mystery of the Model

The identity of the young woman in Dürer’s painting remains unknown. This anonymity has fueled speculation for centuries, as scholars attempt to piece together clues from the style, date, and context of the portrait. Some have suggested she may have been a courtesan, given her fashionable appearance and the informal nature of the image. Others propose she might have been a noblewoman or the daughter of a patron.

In Renaissance Venice, portraiture of women often blended idealization with reality. Rather than strict depictions of status or identity, portraits aimed to elevate the sitter’s beauty and poise. This makes it difficult to determine whether Dürer’s painting was meant as a true likeness or an artistic exercise in portraying the ideal Venetian woman. Still, the quiet naturalism suggests that she was someone real—perhaps observed from life.

There’s also the possibility that this was a personal sketch transformed into a finished oil painting. Dürer was known to make drawings and studies of people he encountered during his travels. While this painting shows more polish than a casual study, its small scale and intimate tone suggest it may have been created for his own enjoyment or as a gift, rather than a public commission.

Regardless of who she was, the sitter’s mystery only deepens the painting’s allure. She exists as both symbol and individual—an embodiment of early 16th-century Venetian femininity, and a real young woman captured in a fleeting moment. That delicate balance between the personal and the timeless is part of what keeps us looking.

Venetian Influence: Style Meets Substance

Albrecht Dürer’s artistic transformation during his time in Venice is clearly reflected in the Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman. Before 1505, much of his work followed the Northern Gothic tradition—emphasizing intricate detail, symbolic content, and religious themes. His engravings, such as The Knight, Death, and the Devil and St. Jerome in His Study, are masterpieces of intellectual complexity. But in Venice, Dürer began to incorporate the Italian focus on naturalism, idealized forms, and human emotion.

In Venetian art, beauty was seen as a reflection of inner virtue—an idea rooted in Neoplatonic philosophy. Dürer encountered this through the works of Giovanni Bellini and Giorgione, who depicted women not as allegories but as real individuals filled with grace and serenity. The Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman echoes this approach. The sitter’s expression is soft and introspective, not idealized into abstraction, but imbued with emotional depth.

Technically, Dürer adopted the Venetian emphasis on softness and color. The smooth transitions of light across her face and the warm tonal palette speak to a painter now fluent in Italian techniques. Yet he retained his Northern precision in the careful delineation of features and fine textures. This portrait is not an imitation of the Venetian style—it’s a synthesis of two artistic languages.

In this fusion lies the genius of Dürer’s mature style. He brought German discipline and Italian elegance into harmony, creating works that resonated across cultural lines. Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman is a quiet testament to that achievement.

The Portrait’s Place in Dürer’s Oeuvre

Within Dürer’s body of work, Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman occupies a unique and revealing place. While his engravings and altarpieces are more widely known, his portraits—especially those executed in oil—offer a quieter, more intimate look at his evolving artistic personality. Created during a period of intense experimentation and cross-cultural influence, this painting stands apart as a deeply personal and stylistically significant piece.

Before his Venetian journeys, Dürer’s portraiture was heavily Northern in tone: stiff poses, dark backdrops, and sometimes severe expressions. His earlier depictions, like the Portrait of Barbara Dürer (his mother), are more somber and documentary. In contrast, the Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman is full of subtle feeling and classical grace. It reflects a lightness and warmth rarely seen in his earlier works, signaling a new approach to portraiture—more concerned with presence than symbolism.

Interestingly, this portrait offers a stark contrast to Dürer’s grand religious commissions, such as the Feast of the Rose Garlands, completed during the same Venetian period. That painting is elaborate and filled with symbolism. This small panel, however, is stripped of all narrative. Its power lies in its simplicity. No saints, no scriptural references—just one quiet face rendered with breathtaking empathy.

Moreover, because so many of Dürer’s sketches and paintings were intended for clients or publication, a private portrait like this offers a rare glimpse into his more reflective side. There’s an inwardness here that suggests the painting wasn’t designed to impress a patron or boast of technique—it was meant to capture something fleeting, perhaps even tender.

Preservation and Provenance: Where Is She Now?

Today, Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman resides in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, Austria, one of Europe’s premier repositories of Renaissance and Baroque masterpieces. While many associate Dürer’s works on paper with the Albertina—also in Vienna—this particular oil painting is part of the museum’s core painting collection, reflecting its importance not just as a drawing or study, but as a fully realized artwork.

The painting’s journey from Dürer’s studio to Vienna isn’t completely clear, but it likely passed through several private collections before being acquired by the Habsburgs in the 17th or 18th century. The Habsburgs were avid collectors of masterworks, and their acquisitions eventually formed the backbone of what became the Kunsthistorisches Museum in the 19th century.

Because of its fragility and small scale, the portrait isn’t always on permanent display. The museum rotates sensitive works to prevent light and temperature damage. However, it has been featured in major exhibitions that explore Dürer’s development and his Venetian period. These opportunities allow viewers to see the portrait in conversation with other works from the same era—both his own and those of his Italian contemporaries.

High-resolution imaging and conservation efforts in recent decades have ensured the painting’s preservation. Scientific analyses have confirmed its authenticity, dating, and technique. Though more than 500 years old, the panel remains luminous, retaining the quiet warmth and psychological presence Dürer gave it. That it has survived at all—and in such remarkable condition—is a testament to both his materials and his mastery.

Symbolism or Sentiment? Interpreting the Work

The Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman raises compelling questions not only about the identity of the sitter but also about Dürer’s motives in creating it. Was she a real person with whom he felt a connection? Or was the painting an exercise in ideal beauty and stylistic experimentation? The truth likely lies somewhere in between.

Some scholars believe Dürer was working through the Italian theories of beauty that were popular at the time—particularly the idea that outer beauty reflected inner virtue. The sitter’s symmetrical features, calm demeanor, and refined dress could support the notion that she represents an ideal, rather than a specific individual. Venetian artists often painted “types” rather than portraits, especially when it came to women, and Dürer may have followed that convention.

However, the naturalism and warmth of the painting make it difficult to believe she was entirely imagined. There is too much humanity in her downcast eyes and slightly parted lips. It feels like Dürer saw her—knew her—and wanted to preserve her likeness for reasons more personal than philosophical. Whether she was a noblewoman, a model, or someone he encountered briefly, her depiction suggests something closer to affection than abstraction.

There’s also the possibility that this portrait served as a keepsake, either for Dürer or someone else. Small oil portraits like this were often given as tokens or used for private contemplation rather than public display. If it was commissioned, we’ve lost all record of who requested it or why. But even without those details, the emotional tone of the painting invites interpretation—and empathy.

Interpretive Possibilities:

- A personal study of ideal Venetian beauty

- A keepsake or memento from Dürer’s travels

- A quiet commission for a private patron

- An emotional encounter remembered in paint

- A stylistic experiment in oil portraiture

Conclusion: Why She Still Speaks to Us

More than five centuries after she was painted, Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman continues to captivate. She is elegant, mysterious, and human—an embodiment of both artistic mastery and cultural exchange. In her stillness, we find echoes of a time long past, but also something enduring: the beauty of a face observed with respect, curiosity, and care.

This portrait is more than a product of Dürer’s technical evolution—it’s a personal milestone. It marks the moment when a Northern artist opened his heart to the Italian Renaissance and brought its warmth back across the Alps. Yet in doing so, he never lost his roots. He blended the best of both worlds—German precision and Italian grace—into something new, something his own.

Art historians continue to study the portrait for what it reveals about Dürer’s technique, influences, and psychology. But even without scholarly interpretation, the painting resonates. She doesn’t need a name or backstory to move us. Her dignity and grace speak louder than any historical record ever could.

In a world often dominated by grand gestures and loud statements, this modest panel reminds us that quiet beauty can be the most powerful of all. She looks away, lost in thought—but we’re held fast. In that still, contemplative moment, Dürer captured not just a woman’s likeness, but her soul.

Key Takeaways

- Albrecht Dürer’s Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman was painted in oil on panel during his second trip to Venice around 1505.

- The sitter remains unidentified, though her presence and fashion reflect Venetian ideals of the early 16th century.

- The work blends Northern detail with Southern softness, marking a stylistic turning point in Dürer’s career.

- Housed in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the painting is rarely displayed but meticulously preserved.

- The portrait continues to inspire with its emotional subtlety, mystery, and timeless beauty.

FAQs

Where is Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman housed today?

- The painting is in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

Was this work a chalk drawing or an oil painting?

- It is an oil painting on wood panel, not a chalk drawing.

Who is the woman in the portrait?

- Her identity is unknown, though she may have been a model, noblewoman, or courtesan.

What makes this portrait unique in Dürer’s body of work?

- Its intimacy, emotional tone, and blend of Venetian and Northern elements set it apart from his more formal or symbolic works.

Why is the portrait important in art history?

- It shows Dürer’s personal and stylistic engagement with the Italian Renaissance and remains a key example of cross-cultural artistic synthesis.