In 1876, the sleepy hills of the Peloponnesian peninsula were shaken by one of archaeology’s greatest revelations. Heinrich Schliemann, a determined amateur archaeologist with a deep love for Homer, unearthed a glinting object buried beneath centuries of dust and stone at the ancient citadel of Mycenae. The artifact—crafted from thin hammered gold—was a funerary mask placed over the face of a long-dead man. Believing he had found the tomb of the legendary king of the Greeks, Schliemann triumphantly declared that he had “gazed upon the face of Agamemnon.”

The find was made in what is now known as Grave Circle A, a royal Mycenaean burial site dating to the 16th century BC. The mask was one of several uncovered in a cluster of shaft graves, each filled with weapons, gold jewelry, and other signs of immense wealth and status. The mask that captivated the world featured a detailed face with an arched mustache, finely modeled ears, and an almost serene expression—unique among the others in the circle. Its discovery helped solidify the growing view that a powerful civilization had thrived in Greece well before the classical age.

Before Schliemann’s excavations, many Western scholars considered Homeric epics little more than poetic fiction. The discovery of Troy in the 1870s, followed by the burial masks at Mycenae, prompted a dramatic shift. Here was material proof that kings, warriors, and elaborate palaces did exist in the Bronze Age Greek world. These finds did not confirm the Iliad line by line, but they provided tangible support for the cultural memory preserved in the poems. The civilization known as the Mycenaeans had left behind stone walls, palatial complexes, and treasures that pointed to a highly organized and warlike society.

Grave Circle A, located just inside the Lion Gate at Mycenae, revealed six shaft graves containing a total of nineteen bodies. The graves dated from roughly 1600 to 1500 BC, placing them several centuries before the supposed date of the Trojan War. In one of these shafts, Schliemann found five gold masks, each covering the face of a deceased male. Yet one stood out for its detail and craftsmanship: a mask that looked too stylized, too personal, almost too modern. This was the one Schliemann identified as belonging to Agamemnon—an interpretation that continues to spark debate today.

Schliemann’s Mission and Methods

Heinrich Schliemann was not a trained archaeologist, but he possessed the two things essential to any major dig: a burning passion and a large fortune. Born in 1822 in the German town of Neubukow, he worked his way up through mercantile and banking ventures before turning his attention to archaeology in midlife. Schliemann was obsessed with the belief that the Trojan War had a historical basis. He taught himself Greek and studied Homer, treating the Iliad and Odyssey not as myth but as roadmaps to buried civilizations.

His excavation strategy was both bold and controversial. He ignored much of the cautious methodology later standard in archaeology and preferred to dig quickly and decisively. At Troy, this led to the destruction of upper layers that may have contained vital information. At Mycenae, however, Schliemann exercised slightly more care, due in part to oversight by the Greek Archaeological Society. His aim was not simply to uncover ancient cities but to prove that Homer was recounting real history, not mere legend.

Schliemann’s Mycenaean dig was granted by the Greek government in 1876. The area had long been recognized as a place of ancient ruins, but its full importance was not yet understood. Once work began in earnest, the graves of Grave Circle A revealed a wealth of material that exceeded all expectations. As the artifacts emerged—golden daggers, drinking cups, and masks—it became clear that this was the burial site of a powerful elite. Schliemann’s claim that one of the masks belonged to Agamemnon added to the drama, even if it lacked concrete proof.

Despite his flaws, Schliemann’s contributions to archaeology are undeniable. He opened the door to systematic investigation of pre-classical Greece and forced a rethinking of early European history. His blending of literature and excavation, while unconventional, sparked a wave of interest that brought legitimacy to Mycenaean studies. Though later scholars have corrected many of his errors, his name remains forever linked with the golden mask that bears the name of a king.

Grave Circle A and the Gold Mask’s Unearthing

Grave Circle A lies just inside the imposing Lion Gate, the entrance to the ancient citadel of Mycenae. Measuring about 90 feet in diameter, the circle was once marked by a double ring of stones and included six shaft graves dug deep into bedrock. These graves contained nineteen bodies—sixteen adults and three children—buried with an astonishing array of precious objects. Among the most remarkable finds were five gold death masks, each placed over the face of a deceased male. One, however, stood out.

The so-called Mask of Agamemnon was found in Grave V, resting on the skull of an adult male. The mask measures about 12 inches across and was crafted from a single sheet of gold, hammered into shape using a repoussé technique. It features finely detailed facial features, including a full mustache, carefully arched eyebrows, and open eyelids—distinctive traits not shared by the other, more stylized masks. This level of individuality led Schliemann to believe it marked someone of extraordinary status.

The richness of the grave goods in Circle A reveals much about Mycenaean elite culture. These were warrior-kings buried with their weapons, gold cups, ornamental breastplates, and finely crafted jewelry. Their graves suggest a strong belief in an afterlife where wealth and symbols of power were still meaningful. The artistic sophistication on display predates the rise of classical Greece by centuries, showing that Mycenae was already a hub of political and cultural development during the mid-second millennium BC.

Among the treasures found were:

- Six gold funeral masks, including the detailed one attributed to Agamemnon

- Bronze swords inlaid with gold and niello

- Gold diadems, bead necklaces, and seal stones

- Carved amethyst and agate ornaments

- Silver drinking cups and ceremonial vessels

These finds, now housed in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, represent the first real window into the lives of Greece’s Bronze Age aristocracy.

Who Was Agamemnon? Myth, Legend, or Reality?

Agamemnon stands as one of the central figures in Greek mythology, portrayed in Homer’s Iliad as the high king of the Greeks during the Trojan War. The son of Atreus and brother of Menelaus, Agamemnon ruled from the citadel of Mycenae and led a coalition of Achaean forces across the Aegean to besiege Troy. His leadership was marked by both authority and arrogance, and his quarrel with Achilles nearly fractured the entire campaign.

While the Iliad provides a vivid literary portrait, its events are set during a shadowy period of Greek history—possibly around 1200 BC. Scholars refer to this as the Late Bronze Age collapse, a time when Mycenaean palaces were falling and written records were scarce. Agamemnon himself is not mentioned in any surviving Mycenaean texts, such as the Linear B tablets, which makes his historical status uncertain. Nevertheless, the archaeological wealth of Mycenae lends some weight to the idea that he may have been inspired by real rulers.

The Mycenaean civilization flourished from about 1600 to 1100 BC. During this period, powerful kings ruled from fortified palace complexes and maintained trade networks reaching as far as Egypt and Mesopotamia. The grand architecture, rich grave goods, and artistic sophistication of Mycenae suggest that it was a center of power in its time. Whether or not a single individual named Agamemnon ruled there, it is clear that someone of considerable influence did.

Agamemnon in Homer and Greek Epic Tradition

In the Iliad, Agamemnon is a proud and commanding figure who often clashes with his fellow Greeks. His decision to take Briseis from Achilles triggers a chain of events that nearly costs the Greeks their victory. Beyond Homer, Agamemnon’s story continues in later tragedies, including Aeschylus’ Oresteia, where he returns from Troy only to be murdered by his wife Clytemnestra. These tales reflect the complexity of Greek moral thought, where heroes are often flawed and divine justice is unpredictable.

Agamemnon became a symbol of kingly authority and tragic fate in the Greek cultural imagination. While no direct evidence confirms his existence, the enduring power of his name suggests that he may represent a composite memory of real Mycenaean leaders. The funerary practices uncovered at Mycenae—especially the burial of elites with gold masks—mirror the honor and reverence described in Homeric funeral scenes.

Possible Historical Equivalents

Some scholars propose that the figure of Agamemnon may be based on a remembered line of powerful Mycenaean kings. The Linear B tablets recovered from other palace sites list names of officials and rulers, though none clearly match “Agamemnon.” Still, the administrative complexity of Mycenaean society and the grandeur of its palaces point to centralized authority. It’s likely that a series of warrior-chieftains ruled at Mycenae, and one or more could have inspired the legend.

Other researchers suggest that the Agamemnon story may reflect a broader Indo-European tradition of epic war leaders. The tale of a king who wages a long war abroad and returns home to betrayal appears in multiple ancient cultures. Whether Agamemnon was a historical king, a literary symbol, or both, the mask bearing his name remains one of archaeology’s most enduring puzzles.

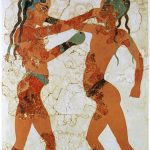

Gold of the Dead: The Mask’s Physical Description

The so-called Mask of Agamemnon stands out not only for its supposed identity but also for its exceptional craftsmanship. Measuring approximately 12 inches (30 cm) across and weighing around 317 grams, the mask is made of thin gold hammered into shape using the repoussé technique—an ancient method involving shaping metal from the reverse side to create a design in relief. It was designed to cover the face of the deceased and is believed to have been placed directly on the corpse as part of an elite funerary rite.

Unlike the other gold masks found in Grave Circle A, the Mask of Agamemnon has a strikingly individualized appearance. The mask features arched eyebrows, cut-out eyes, a thin nose, and a mustache that is uniquely styled and separated from the beard—details that do not appear in any of the other masks found in the same context. Its expression is calm, almost regal, and far more personalized than the typical stylized features of Mycenaean funerary art. This individuality has fueled both admiration and suspicion.

The craftsmanship suggests the hand of a skilled artisan familiar with fine metalwork. The beard and mustache were carefully incised, and the lines of the face were subtly contoured to create depth and character. Unlike the flat, mask-like visages of the other gold death masks from Mycenae, this one possesses a three-dimensionality that suggests an intentional effort to represent the unique features of the deceased. Whether this was a form of portraiture or symbolic exaggeration remains unclear, but it certainly made an impression on Schliemann and later scholars.

Artistic Features and Construction

The technique used in creating the mask was sophisticated for its time. Repoussé, involving tools and soft backing materials, required precision and confidence. The gold sheet used is remarkably thin, indicating the artisan’s control in achieving high relief without tearing the metal. Holes near the ears suggest that the mask was fastened with string or wire, ensuring it stayed in place over the corpse’s face. The absence of inscriptions, however, leaves us with no names or direct identifiers.

The mask’s most debated features are its mustache and open eyes. Some scholars argue that the open eyes were an artistic flourish, while others see them as symbolic—perhaps suggesting a kind of eternal vigilance or a passage into the afterlife. The mustache is also unusual. Facial hair is rarely depicted so prominently in Mycenaean funerary art, and its precise, stylized form differs markedly from other masks in the same site. These deviations have led some to suggest that the mask was not created during the same period as the others.

Comparisons with Other Mycenaean Masks

When compared side by side, the Mask of Agamemnon appears unique among the five other gold death masks found in Grave Circle A. The others are more schematic, with less detail in the facial features and a more uniform, almost generic appearance. Their eyes are closed, their mouths plain, and their expressions featureless. This contrast has raised questions: Why is one mask so distinct? Was it made later, or by a different artisan? Or perhaps intended for a particularly important figure?

While individuality in ancient funerary art is not unheard of, the degree of detail here is unusual for the Mycenaean period. The differences could point to a number of possibilities: it may have belonged to a different generation, been commissioned under special circumstances, or even restored or modified in more recent centuries. This has become a central issue in the authenticity debate surrounding the mask—one that continues to divide scholars to this day.

Authentic or Forgery? The Ongoing Debate

From the moment of its unveiling, the Mask of Agamemnon captivated the world—but it also raised eyebrows. Critics noted its odd stylistic features and questioned whether Schliemann, who had a reputation for dramatic claims and romanticized interpretations, might have tampered with or even commissioned the mask himself. While no direct proof of forgery exists, the debate has persisted for over a century, with scholars split between those who affirm its authenticity and those who doubt its origin.

The key issue in the debate is the stylistic dissonance between this mask and the others found in the same grave circle. The level of facial detail, the realistic features, and the open eyes are all uncharacteristic of 16th-century BC Mycenaean funerary art. These elements suggest that either the mask was a one-of-a-kind creation or that it was not from the same period as the other masks. Some have gone further, alleging that the mask may have been altered—or even fabricated—by Schliemann to match his Homeric expectations.

Arguments for Authenticity

Supporters of the mask’s authenticity point to several facts. First, it was discovered in a sealed shaft grave, beneath undisturbed layers of earth and with other clearly Bronze Age artifacts. Soil analysis and artifact context suggest that the grave was not tampered with in modern times. Additionally, the gold used is consistent with other objects from the same grave circle, and the construction technique is compatible with ancient repoussé work found elsewhere in the region.

Scientific studies conducted in the 20th and 21st centuries have attempted to clarify the mask’s age, though with limited success. No radiocarbon dating can be done directly on the gold, and stylistic comparisons are ultimately subjective. Still, the mask’s burial context remains a strong point in favor of its authenticity. Schliemann was under constant supervision from Greek officials during much of the excavation, making a large-scale hoax less likely.

Arguments for Forgery

On the other hand, skeptics have noted that Schliemann had both the motive and opportunity to embellish his findings. Known for his showmanship, Schliemann had previously been accused of manipulating excavation sites at Troy to create a more dramatic narrative. The unusually modern appearance of the mask—particularly its lifelike expression and mustache—has led some to believe it may have been created in the 19th century to satisfy Schliemann’s dream of proving Homer’s kings were real.

One theory suggests that the mask could have been subtly modified after its discovery. A skilled goldsmith, perhaps working with or without Schliemann’s direction, might have altered the eyes or mustache to enhance its realism. Another possibility is that a more recent artifact was planted in the grave during the excavation. However, such a theory would require a degree of collusion and deception difficult to sustain under the public and official scrutiny Schliemann faced.

Heinrich Schliemann: Hero or Charlatan?

Few figures in archaeology are as polarizing as Heinrich Schliemann. To his admirers, he was a visionary who opened the ancient world to modern inquiry. To his critics, he was a romantic treasure-hunter who bent facts to suit his narrative. The truth lies somewhere between these extremes. Schliemann’s passion for Homer led him to uncover two of the most significant sites in Greek prehistory: Troy and Mycenae. Yet his methods, claims, and motives remain under scrutiny.

Born in 1822 in northern Germany, Schliemann was largely self-educated. After building a fortune in international trade, he retired young and devoted himself to uncovering the historical roots of Homer’s epics. He married a Greek woman, Sophia Engastromenos, in 1869 and often portrayed her as a symbolic link between modern Greece and its ancient past—famously posing her with jewelry he claimed belonged to Helen of Troy. His romanticism was part of his brand, but it often blurred the lines between fact and fiction.

Life Before Mycenae

Schliemann’s early life was marked by poverty and hardship. His fascination with Homer began in childhood, and he reportedly memorized large sections of the Iliad and Odyssey by heart. His business career took him around the world, from Russia to the United States, and made him a wealthy man by the age of 40. With money in hand and Homer in mind, he began his quest to find the real Troy, eventually digging at Hisarlik in northwestern Anatolia in the 1870s.

There, he uncovered what he called “Priam’s Treasure,” a cache of gold and artifacts he believed to belong to the king of Troy. However, later archaeological work showed that he had dug through the layers that actually matched the Iliad’s time period. Despite this, his efforts brought new attention to Bronze Age archaeology and paved the way for more rigorous exploration in the years to come.

Reputation Among Peers

Among his contemporaries, Schliemann was both respected and criticized. Scholars admired his dedication and his ability to fund large-scale excavations, but many took issue with his tendency to make bold, unsubstantiated claims. His naming of the Mask of Agamemnon was typical of this pattern: dramatic, media-friendly, and not backed by solid evidence. Nevertheless, the finds at Mycenae were genuine, and their importance undeniable.

Modern archaeologists tend to view Schliemann as a flawed pioneer. He lacked formal training and often failed to record precise stratigraphy, but he made discoveries that shifted the understanding of Greek prehistory forever. His desire to find Homer’s world sometimes led him to stretch interpretations, but he also helped establish Bronze Age Greece as a field worth serious study. Whether hero or charlatan, Schliemann’s legacy is one of ambition, achievement, and controversy.

The Mask’s Cultural and Religious Context

The Mask of Agamemnon was not merely a piece of funerary art—it was a window into the beliefs, rituals, and social structures of the Mycenaean elite. In Mycenaean Greece, death was not an end but a transition. The way a person was buried, especially a ruler or warrior, reflected his societal rank and perhaps his intended station in the afterlife. The use of gold masks as part of burial customs in Grave Circle A suggests that the Mycenaeans believed strongly in honoring the dead with symbols of status and permanence.

Gold held special significance in Mycenaean culture, far beyond its monetary value. As a material that does not tarnish or corrode, gold symbolized eternity and divine favor. Its inclusion in the tombs of the Mycenaean elite was not accidental. These objects—masks, cups, jewelry—served both as markers of wealth and as offerings for the deceased’s journey into the next world. The level of craftsmanship and the resources invested in these burials speak to a culture deeply preoccupied with legacy and spiritual continuance.

Burial practices during this time were elaborate, especially for members of the ruling class. Shaft graves were deep vertical pits lined with stone, where bodies were placed along with numerous grave goods. These included weapons, armor, ornaments, and ceremonial items. Women and children, when buried in such graves, were also adorned with finery, though masks appear to have been reserved for high-status adult males. The overall emphasis was on projecting power, not just in life, but in death as well.

Mycenaean Burial Traditions

The Mycenaeans practiced elite shaft burial from roughly 1600 to 1500 BC, before transitioning to tholos or “beehive” tombs in the later part of the Bronze Age. Shaft graves, such as those in Grave Circle A, were typically used for multiple individuals and often reopened to accommodate subsequent burials. The graves were carefully arranged, sometimes with built-in altars or platforms, and were accompanied by carved stele to mark their importance. Offerings of food and drink, likely for the use of the departed in the afterlife, were also common.

These practices suggest a strong continuity of belief between generations. The preservation of identity through elaborate funerary masks was part of this tradition. While the use of gold was likely restricted to the wealthiest, even less extravagant burials often included personal items, such as tools, weapons, or charms. This spiritual and material investment in the dead reflects a culture in which the past was intimately connected to the present and future.

Symbolism of Gold in Ancient Greece

To the Mycenaeans, gold was not only a symbol of wealth but also of divine sanction and permanence. In a world where political legitimacy often stemmed from lineage and ancestral deeds, displaying gold in tombs served as a posthumous declaration of authority. The glint of gold could bind the living to the dead, establishing an unbroken chain of kingship and power.

Later Greek culture inherited and expanded on this symbolism. Gold was associated with the gods and used in the statues of Athena and Zeus. The funerary use of gold, especially in masks, faded after the Mycenaean collapse, but the concept of hero-cult worship—where individuals revered long-dead warriors—may have roots in these earlier customs. The Mask of Agamemnon, whether real or symbolic, thus sits at the intersection of spiritual tradition and political identity.

The Legacy of the Mask in Modern Greece

Since its discovery, the Mask of Agamemnon has become one of Greece’s most iconic archaeological artifacts. It serves not only as a testament to the Mycenaean civilization but also as a symbol of Greek national pride and cultural heritage. Displayed prominently in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, the mask draws visitors from around the world who come to glimpse what many still believe is the face of a Homeric king. Whether that belief holds water or not, the mask has taken on a life of its own in the modern era.

In post-independence Greece, artifacts like the mask played an important role in reinforcing a narrative of cultural continuity. The Greek state, eager to connect the present with its glorious past, embraced the mask as a symbol of Hellenic identity stretching back to the Bronze Age. It appeared on postage stamps, in textbooks, and even in national promotional materials. The ancient past, once viewed as fragmented and mysterious, now had a golden face—literally.

The mask’s fame has also helped shape global perceptions of ancient Greece. While many foreign visitors are familiar with the Parthenon and classical Athens, the mask introduces them to a deeper layer of Greek history—one rooted in warrior-kings, monumental tombs, and epic struggles that predate the democracy of Pericles by a thousand years. Its discovery has broadened the scope of what it means to be “Greek,” both in academic and popular understanding.

The Mask as a National Symbol

Since the late 19th century, the Mask of Agamemnon has held a place of honor in Greek cultural and historical narratives. It has been used in national celebrations, museum branding, and educational campaigns. The Greek government has even featured it in diplomatic exhibitions abroad to highlight the country’s ancient legacy. Though the original context of the mask remains a subject of debate, its role in modern Greece is undisputed: it represents both the mystery and majesty of the country’s earliest civilization.

Public school curricula in Greece frequently feature the mask in discussions of national origins and early European history. It serves as a tangible link between myth and material culture. While scholars may debate its exact origins, the general public sees it as part of a continuum that connects the age of Homer to the rise of modern Hellenism. The mask is not just a historical object—it is a cultural touchstone.

Public Reception and International Fame

From the moment it was unearthed, the mask captured the imagination of the world. Newspapers across Europe printed illustrations and dramatic headlines proclaiming the rediscovery of Homer’s world. In the 20th and 21st centuries, it has been featured in museum exhibitions in Paris, London, Berlin, and New York. Its image graces countless books, posters, and websites devoted to ancient history and archaeology.

International scholars and tourists alike flock to the National Archaeological Museum to see the mask in person. Its display case is rarely without a crowd, and its impact on popular culture has only grown with time. Though the debate over its authenticity remains unresolved, the mask has achieved a level of fame that transcends academic arguments. It has become a universal emblem of early European civilization and the enduring allure of the ancient world.

Art and Imitation: The Mask’s Influence on Western Art

The visual power of the Mask of Agamemnon has made it a source of inspiration for generations of artists, sculptors, designers, and filmmakers. Its blend of realism and symbolism, its gold medium, and its legendary associations make it ripe for reinterpretation. The mask’s serene expression and elaborate mustache have appeared in everything from jewelry designs to film props, embedding it deep within the Western cultural imagination.

Sculptors have recreated the mask in various materials, from bronze to stone, often displaying these works in public spaces or educational institutions. Jewelry makers have taken inspiration from its design elements, crafting gold pieces that echo the mask’s curves and contours. Museums around the world produce replicas for educational use, allowing students and visitors to handle and study its features up close.

Modern Artistic Tributes

Contemporary artists have paid homage to the mask through sculpture, painting, and multimedia installations. It has appeared in modern art exhibits as a symbol of lost identity, ancestral memory, or imperial legacy. The Greek-American sculptor Chryssa used mask motifs in her work, reflecting on heritage and displacement. In literature and visual storytelling, the mask is often a stand-in for buried truths and ancient legacies awaiting rediscovery.

Even architecture has borrowed from Mycenaean themes, using motifs inspired by Grave Circle A and its contents. In cultural centers, educational museums, and even corporate logos, the silhouette of the mask serves as a shorthand for ancient wisdom and regal authority. Its design has endured not just as archaeology, but as a work of art in its own right.

Educational and Museum Replicas

Museums across the globe—such as the British Museum, the Louvre, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art—house replicas of the Mask of Agamemnon. These are used in classroom programs, traveling exhibitions, and interactive learning centers to give broader audiences access to one of history’s most iconic images. The replicas, often accompanied by videos or guided tours, help contextualize the Mycenaean world and make Bronze Age history tangible.

Some of these replicas are created using 3D scanning and gold-leaf reproduction techniques, making them remarkably close in appearance to the original. They allow institutions without direct access to the original to share its educational value and mystique. In this way, the mask continues to teach, inspire, and provoke curiosity in students and scholars alike.

The Mask Today: A Testament or a Cautionary Tale?

Today, the Mask of Agamemnon sits at a crossroads—both a prized artifact of ancient craftsmanship and a flashpoint for scholarly debate. It reminds us of the dangers of romanticizing the past while also highlighting the importance of believing in historical continuity. Whether it is the actual face of a Homeric king or an anonymous noble, it still tells a powerful story about Mycenaean civilization, early archaeology, and the enduring impact of myth.

The mask teaches us that history is often reconstructed through fragments—some clear, others opaque. Its gold surface reflects not only the face it once covered but the assumptions and ambitions of those who found it. For all the doubts that have emerged over time, the mask has continued to anchor discussions of Bronze Age identity, cultural memory, and archaeological ethics.

What the Mask Teaches Us About Ancient Greece

The Mycenaean world, as seen through artifacts like this mask, was one of ceremony, hierarchy, and technical skill. The presence of gold in funerary contexts reveals how rulers wanted to be remembered—with splendor and honor. Even in death, they asserted dominance, legacy, and divine favor. These practices laid the foundations for Greek concepts of heroism and remembrance that would endure into the classical period.

From burial masks to epic poetry, the ancient Greeks developed a system of values where honor in life and dignity in death were inseparable. The mask is one piece in that larger mosaic. Whether the face beneath it was that of Agamemnon or another powerful warrior, the principle remains: greatness was remembered in gold.

Lessons for Archaeology and Historical Integrity

The debate over the mask’s authenticity highlights the importance of methodological discipline in archaeology. Schliemann’s boldness brought great discoveries, but his interpretive leaps also created confusion. Modern archaeologists strive to avoid such mistakes, emphasizing careful recording, stratigraphic analysis, and conservative claims. The mask, in this sense, is both a reward and a warning.

It also reminds us that cultural heritage must be handled with care and respect. Artifacts are not merely trophies—they are pieces of a human puzzle, meant to be studied, preserved, and shared. The Mask of Agamemnon may or may not depict a king, but it undeniably represents the rich, complicated legacy of Bronze Age Greece and the challenges of uncovering its story.

Key Takeaways

- The Mask of Agamemnon was discovered by Heinrich Schliemann in Grave Circle A at Mycenae in 1876.

- The mask stands out for its detailed craftsmanship, especially compared to other Mycenaean funerary masks.

- Debate continues over whether the mask is authentic or was altered or fabricated during excavation.

- The mask has become a cultural and national symbol in modern Greece, appearing in museums and public art.

- Whether myth or reality, the mask embodies the grandeur and mystery of Mycenaean civilization.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Was the Mask of Agamemnon really made for King Agamemnon?

No definitive evidence proves the mask belonged to Agamemnon. The name was assigned by Schliemann based on speculation. - Is the mask authentic or a 19th-century forgery?

Most archaeologists accept its authenticity, but doubts persist due to its unique style and Schliemann’s reputation. - Where is the Mask of Agamemnon displayed today?

The original mask is housed in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, Greece. - What is the significance of the mask in Greek culture?

It serves as a symbol of Mycenaean power, Greek national heritage, and the romantic connection between myth and history. - How old is the mask?

It dates to approximately 1550–1500 BC, making it over 3,500 years old.