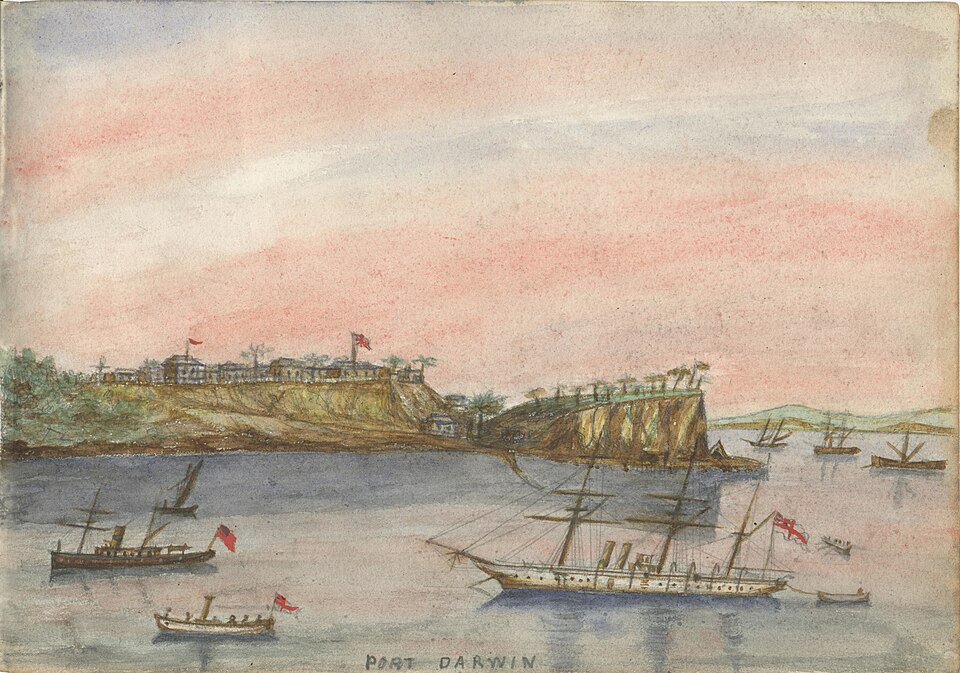

The first images of what would eventually become Darwin were not made by artists who saw themselves as artists. They came from surveyors, naval officers, and topographers tasked with transforming a remote harbor in northern Australia into something knowable on paper. Those early visual records—coastal profiles, navigational sketches, and settlement diagrams—were both practical tools and the beginning of the region’s art history. The year 1839 marks the first documented evaluation of the harbour later named Port Darwin, and the sketches that followed helped translate a vast coastline into a place that could be managed and claimed.

A Coast That Needed Illustrating

In the 19th century, charting land was a form of authorship. The only way to establish a presence in this part of the continent was to draw it into familiarity. Naval officers made the first marks—careful horizon lines that depicted the headlands and cliffs. These were visual claims, asserting that the coast had been seen, measured, and now existed as part of a wider world. They were not romantic artworks in the European tradition, but they were the primary aesthetic documents of their time.

When George Goyder arrived with a surveying team in 1869 to create a permanent European settlement—initially named Palmerston—the artistic function of record‑keeping intensified. Buildings, storage structures, and early civic features like wharves and jetties needed visual plans, and those plans became a gallery of a place in progress.

A Small Settlement Takes Shape

The early buildings of Palmerston signalled a tentative confidence—structures designed to endure in a climate not yet fully understood by the newcomers. One of the few survivors of that era is Brown’s Mart (built 1885), a masonry structure erected as a Mining Exchange and later transformed into a performance and cultural venue. Its durability makes it a rare visual artefact from the colony’s demographic and environmental struggles.

Because so many early structures were made quickly and with limited knowledge of tropical weather cycles, a large portion of Darwin’s architectural heritage did not last. Termites, humidity, cyclonic winds, and periodic wartime damage gradually erased the colonial streetscape, leaving art and architecture from this period comparatively scarce. What remains—photographs, building plans, the occasional architectural fragment—plays an outsized role in shaping our understanding of the city’s visual beginnings.

The Vast Distance to Everywhere Else

Darwin’s position at the northern rim of Australia made it closer to other continents than to the population centres of its own country. Yet in the 19th century, these potential connections were unrealized. Travel routes were few, and shipping was unpredictable. The settlement remained visually starved of outside influence.

Artists—where they existed at all—were often transient:

- Naval officers stationed briefly before moving on

- Technicians who drew to support infrastructure, not galleries

- Travellers whose sketchbooks served as private memoirs rather than public culture

As a result, much of Darwin’s early art was functional rather than expressive. But function can have beauty. The waxy, salt‑stained paper of maritime sketches; the exacting lines of cadastral maps; the humble watercolours washed with tropical glare—all contribute to a primary visual memory of the place.

Then Came the Telegraph

The most transformative development of the late 19th century was the Overland Telegraph, constructed 1870–1872, connecting Darwin with southern Australia and, through submarine cables, with international communication networks.

Suddenly, Darwin was not merely a remote anchorage but an entry point into a global exchange of information. Alongside the telegraph infrastructure came engineers, technicians, and administrators—many carrying the basic materials of recreational drawing or photography. Their creative work was not always ambitious, but it represented a cultural shift: people in Darwin were now documenting their lives not solely out of duty but out of personal interest.

A Scene Waiting for an Audience

By the late 19th century, Darwin had the beginnings of a civic identity, supported by:

- A consistent architectural presence, however fragile

- A growing archive of visual records

- A population with increased leisure and personal expression

Yet without formal institutions—no gallery, no arts school, no organized exhibitions—there was little incentive for aspiring artists to remain. Creative ambition in Darwin was frequently a stopover, not a destination.

A curious twist lies in the fact that the deepest early visual footprint endured not in museums but in government files and practical documentation. The city’s youthful art history is preserved more in the drawers of survey archives than in the halls of collectors.

The Hint of a Future Culture

The foundation for Darwin’s later artistic development can be traced back to these early documents. They show:

- The tension between impermanence and aspiration

- The fragility of cultural ambition in a harsh climate

- A place still finding justification for creative permanence

Darwin entered the 20th century not as a mature artistic centre but as a location where art awaited its moment—where infrastructure, people, and imagination had not yet converged with the force that would eventually define a northern identity.

That convergence, however, was coming—and the events that would spark it were not the peaceful kind.

Chapter 2: Remote but Not Silent—1900 to 1939

It is tempting to think of Darwin in the early 20th century as a backwater—hot, distant, and forgotten. In many respects, it was. But it was also a city in tension: small but growing, poor but strategically important, culturally underdeveloped but socially volatile. For artists and image-makers, Darwin was not a place that nurtured careers, but it was a place that needed to be documented, understood, and occasionally dignified through visual order. In this period—between Federation and the dawn of World War II—Darwin’s visual culture remained thin but charged with potential, shaped by harsh weather, slow travel, and the unending challenge of distance.

A City Renamed, a Community Reconfigured

In 1911, the name “Darwin” became official, replacing “Palmerston” as the city’s designation when the Northern Territory transferred from South Australian control to direct administration by the Commonwealth. This was not simply a bureaucratic adjustment; it signalled a cultural break. The settlement was no longer a provincial extension of Adelaide’s ambitions but a federal territory—uniquely exposed, uniquely burdened, and destined to become a military and communications hub.

That new identity found little reflection in formal art, because there were still no significant art schools, galleries, or markets. But it crept into the visual record in quieter ways: more civic portraits, better photographs of street scenes, newly confident architecture. Artists remained rare, but photographers—especially those attached to government or the press—began to shape a recognisable image of Darwin as a functioning, if fragile, town.

The Labour Struggle as Civic Theatre

In December 1918, an angry crowd of more than 1,000 residents marched on Government House in protest against the Administrator, Dr. John Gilruth, in what became known as the Darwin Rebellion.

The photographs of this event are among the most politically charged images of pre-war Darwin. They show not just protest but a form of grassroots theatre—a community enacting its frustration in the absence of other expressive outlets. Men carried placards, banners, and homemade signs. Government House became a temporary stage for a dramatic showdown between federal authority and local resistance. The crowd was mixed in dress and bearing—dockworkers, clerks, returned servicemen—and the surviving images capture a raw and unfiltered civic energy.

Though few, if any, professional artists worked in Darwin at the time, such images became part of the city’s visual culture. They were printed in newspapers, stored in government records, and occasionally kept in family albums. Darwin’s early 20th-century art history, then, was not made in studios but on the streets—in acts of protest, documentation, and informal public display.

Everyday Life, Captured in Fragments

Outside of political drama, daily life in Darwin left a scattered visual trail. Photographs of harbour activity, public events, and tropical domesticity—children in corrugated-iron houses, women under verandahs, soldiers at rest—appear in archival collections and personal albums. These images form the city’s first sustained visual record of itself as a living community rather than a frontier post.

The architecture of this era contributed quietly to the emerging aesthetic. Timber-framed houses lifted on stilts, latticework to catch breezes, tin roofs to reflect the sun—these were not just functional decisions but expressions of adaptation, and they created a visual typology that remains associated with Darwin today. Buildings like Brown’s Mart, one of the few survivors from the 19th century, served as recognisable backdrops for public life—used for events, meetings, and informal performances.

Three recurring visual motifs begin to emerge in images from this period:

- Verandahs and shadow: the constant attempt to escape the sun

- Uniforms: military, police, telegraph operators—all signifying order amid isolation

- Maritime imagery: boats, docks, sea walls, harbours—Darwin’s link to everything beyond it

Together, these fragments offer a kind of accidental portraiture—a city not painted but gradually revealed through its daily appearances.

The Role of Missionaries and Civic Institutions

Though the term “art scene” would be an overstatement, some visual culture was being consciously developed through missions, schools, and civic institutions. Church buildings were among the few structures that included decorative elements—stained glass, carved pews, or symbolic motifs. Missionaries often kept journals and watercolours. Teachers occasionally encouraged drawing as part of basic instruction. But these efforts remained minor and peripheral.

The Kahlin Compound, established in 1913, was officially a government-run institution for so-called “half-caste” children—though its actual purpose, operations, and consequences were more complex and, in many cases, coercive. While not an artistic institution in any sense, Kahlin and sites like it appear in early photographs, plans, and occasional drawings, forming part of the historical visual record of Darwin during this era.

It’s important not to mistake presence for prominence. Much of Darwin’s early 20th-century visual output was marginal: small in scale, fragile in preservation, and disconnected from any commercial or professional network. Yet precisely because of its informality, it offers unvarnished insight into a city trying to define itself without guidance from the cultural capitals to the south.

The Persistence of Distance

The great shaping force of this period remained Darwin’s remoteness. Travel to and from the city was long and uncomfortable. Mail was delayed. Art supplies, when available, were expensive. Exhibition opportunities were nonexistent. For anyone serious about a creative career, Darwin was not an option.

This meant that nearly all art was local, personal, or official. There were few art collectors. No critics. No schools of thought. But this absence created a curious kind of freedom. Without the constraints of fashion or institutional oversight, image-makers in Darwin could document what they liked, how they liked. They sketched boats and buildings. They took photos of storms and open roads. They made memory-books rather than manifestos.

That freedom would not last. In the next decade, Darwin would be pulled into the orbit of global conflict—and with it would come a new wave of artists, architects, and photographers whose job was not self-expression, but national duty.

Chapter 3: War and Ashes—Darwin and the Pacific Front

At 9:58 a.m. on 19 February 1942, the first wave of Japanese bombers descended on Darwin. What followed was not merely a military assault, but the abrupt and irreversible end of the city’s pre-war landscape—physical, social, and cultural. Until that morning, Darwin had lived in a kind of suspended identity: remote, civilian, tropical, slow to change. Within an hour, it was a war zone.

The Bombing of Darwin, Australia’s largest single attack by a foreign power, brought the Pacific War violently to its doorstep. It destroyed infrastructure, sank ships in the harbour, killed over 230 people, and shattered the illusion that Australia’s northern edge could remain marginal. More than a military episode, the bombing redefined the city as a national site of vulnerability—and in the process, reshaped the role of visual culture in documenting, interpreting, and recovering from catastrophe.

The Visual Record of Attack

Unlike previous decades, when the production of imagery was sporadic and often informal, the war years brought a flood of visual material—generated by necessity. Aerial photographs, target maps, and damage reports formed the backbone of military strategy, and with them came a new cohort of image-makers: draughtsmen, mapmakers, military illustrators, and official war photographers.

These were not artists in the traditional sense. But their work—highly detailed, often beautifully rendered—offered a stark new chapter in the art history of Darwin. Their subjects were practical but visually compelling: the outline of bomb craters on dusty runways, the silhouette of sunken ships in murky harbour water, rows of scorched corrugated iron in former housing blocks. The purpose was documentation, not interpretation, yet the result was a devastating visual archive of urban annihilation.

Among the most compelling images from this period are:

- Government aerial surveillance photographs showing bomb trajectories and their aftermath

- Technical drawings of airfields and installations drafted in haste, under pressure

- Photo albums compiled by servicemen stationed in Darwin, many of whom had artistic backgrounds but no time for self-expression

These works survive today less in galleries than in military archives, particularly the Australian War Memorial’s collections, which hold a remarkable number of maps, plans, and images from the 1942–43 bombing campaigns.

Destruction as a Visual Theme

The physical loss was extraordinary. Darwin’s port, which had been the heart of the city’s civilian economy, was heavily damaged. Eight ships were sunk. Wharves, oil tanks, and storage depots were obliterated. Public buildings—some of them dating back to the late 19th century—were cracked, burnt, or flattened.

In a city where cultural heritage was already scarce, this level of destruction was more than just structural—it was symbolic. Brown’s Mart, one of the only major civic buildings to survive multiple upheavals, narrowly escaped ruin again. Other older buildings vanished entirely, and with them, a tangible link to the city’s earliest architectural and visual history.

The war also disrupted personal creativity. Civilians who might once have kept sketchbooks or family albums now fled or focused entirely on survival. Few artworks from within Darwin itself—if any—exist from this moment in traditional media. But the wreckage became a subject in its own right. After the war, local photographers and returning residents began capturing scenes of:

- Half-submerged hulls in Darwin Harbour

- Collapsed churches and school buildings

- Military relics rusting under tropical rain

The city became a kind of open-air ruin, and that visual memory lingered for decades.

Military Artists and Accidental Aesthetics

Not all wartime imagery was purely functional. Some military draughtsmen, especially those trained in architectural or illustrative techniques, left behind sketchbooks and notebooks that show a quieter, more subjective view of wartime Darwin. These drawings are rarely dramatic. Instead, they depict barracks, mess halls, trucks under tarpaulins, and endless roads lined with supply drums. Often made with pencil, ink, or charcoal on cheap paper, these works occupy a strange space between art and utility.

One of the key developments of the era was the rise of a style best described as “field minimalism”—not by choice, but by circumstance. Artists had limited access to materials. Paint warped in heat; canvases attracted mould. Pencils, notebooks, and whatever could be scrounged from quartermaster stores became the tools of war-time visual culture.

This utilitarian aesthetic persisted even after the war. For many Darwin-based artists in later decades, especially those who grew up amid its ruins, there remained a preference for durability, economy, and rawness—an inheritance not of theory, but of necessity.

Debris as Legacy: The Wrecks of Darwin Harbour

When peace came, the wreckage stayed. The Fujita Salvage Operation (1959–61), named after the Japanese company contracted to raise sunken vessels from Darwin Harbour, became a delayed coda to the war. Rusting hulks had dominated the shoreline for nearly two decades. Their gradual removal marked a new phase in the city’s visual rehabilitation—but also signalled the end of one of its most powerful wartime symbols.

Until then, the wrecks had become almost sculptural: coral-covered skeletons, exposed at low tide, ghostly reminders of destruction. They appeared in paintings, postcards, and amateur photographs, often with an eerie stillness that contrasted sharply with the violence of their origins.

The wrecks were not treated as monuments—they were obstacles to navigation. But culturally, they were more than that. For residents who remained after the war, they were part of the visual vocabulary of post-war Darwin, as familiar and haunting as the daily tides.

A City Turned Inside Out

The war did not just demolish buildings; it inverted Darwin’s identity. The city went from being a peripheral outpost to a key defensive hub, and that strategic importance brought surveillance, fortification, and exposure. Art, such as it existed, became bureaucratised—folded into the state apparatus of planning, security, and control.

There was no gallery scene, no community of artists. But there were images—many, and potent. They emerged from observation towers, survey tents, bomb-damaged offices, and later, from the pockets of those who returned. A civilian culture of artistic expression was displaced, but a wartime visual archive exploded in its place.

For Darwin, this was the first time that art—however unintentionally—became a matter of national significance. The next chapter would reveal whether, in peace, the city could regain not only its footing, but its capacity for artistic reinvention.

Chapter 4: Aftermath and Reinvention—1945 to 1965

When the war ended, Darwin was still standing—but only just. Its buildings were damaged or gone, its port half-sunken and rusting, its population scattered. The city had played a key role in the Pacific theatre, but the cost was visibility without stability. In the decade that followed, Darwin’s recovery was not triumphant. It was piecemeal, slow, and improvised. And yet, within this long phase of civic repair, a new visual identity began to take shape—one shaped less by art in the traditional sense than by rebuilding itself as a form of aesthetic decision-making.

A New Kind of City Begins to Appear

The post-war years brought Darwin into a new phase: no longer just a frontier town, it now had strategic importance, an expanding civilian role, and a civic infrastructure to reconstruct from the ground up. The damage from the 1942 Japanese air raids had not been fully repaired during wartime. Ships remained in the harbour long after peace was declared. The city’s main public buildings had been heavily damaged. Schools, houses, offices, and roads needed not only fixing but redesigning.

Reconstruction brought with it a kind of unsung visual creativity. Architects, engineers, and planners had the rare opportunity to reimagine a city from its foundations, albeit on a limited budget and without a central aesthetic vision. What resulted was a loose, emergent style of tropical modernism, defined more by materials and necessity than theory:

- Housing was lifted on stilts for airflow and flood protection

- Verandahs and breeze blocks became ubiquitous architectural features

- Civic buildings were built in concrete, corrugated iron, and fibro sheeting—durable but stylistically stripped-down

What the city lacked in ornament, it made up for in stark visual cohesion: a Darwinian architecture that was raw, repetitive, and suited to its climate.

Visual Memory Begins to Settle in the Ground

During the 1950s, the memory of war gradually shifted from active trauma to subdued backdrop. Though official memorials remained few, a visual language of resilience began to take root in photographs, urban planning documents, and government reports. Darwin’s postwar image, both internally and externally, was no longer just of wreckage—it was of recovery.

Government photographers documented the work of departments restoring public infrastructure. Surveyors redrew maps of a city half-rebuilt. Families took black-and-white snapshots of newly finished homes, army barracks-turned-housing estates, and school parades. These images, often mundane, formed a new visual archive. They captured a Darwin that was still small, still battered, but now pointed forward.

The importance of this kind of documentary record cannot be overstated. Because formal art institutions remained absent through much of this period, and because few professional artists were based in Darwin, it fell to the lens and the blueprint to preserve what the canvas could not.

First Signs of Institutional Culture

In 1964, a legislative decision quietly marked a new stage in Darwin’s cultural development: the creation of an official structure for what would become the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT).

Although the physical museum building would not be completed for some years, the move signified a broader shift in civic priorities. For the first time, there was recognition that Darwin—despite its modest size and remote location—needed a place to collect, interpret, and protect its heritage. That heritage was understood broadly: it included natural history, maritime salvage, ethnographic material, and regional artefacts. But it also implied the beginnings of an artistic consciousness.

Initial collecting efforts focused on material survival:

- Coral samples and maritime relics from the harbour

- Taxidermied animals and regional fossils

- Salvaged tools, ship parts, and fragments from war-era infrastructure

Though these objects were not “artworks” in the strict sense, their presentation required visual care, curation, and storytelling. In this way, MAGNT’s early identity fused science and visual culture—both seeking to preserve the particularities of the north.

Artists on the Margins of Rebuilding

If there were individual artists working in Darwin during this time, they left little public trace. Most were likely amateur: schoolteachers with sketchbooks, returned servicemen who took up woodworking or carving, or local residents who photographed their surroundings out of habit rather than ambition.

But artistic expression did exist, and it often emerged through functional or decorative roles in civic life:

- Painted signage on new public buildings

- Murals in schools or community halls

- Memorial plaques and commemorative mosaics

These objects, rarely signed or preserved, contributed to the slow formation of a visual culture grounded in utility. Art was not something to be bought or exhibited; it was something made when needed, and made to last.

A City Between Eras

By the early 1960s, Darwin stood on the threshold of something new. The war had receded into the background. Reconstruction was largely complete. A younger generation was coming of age, and their expectations would differ sharply from those who had rebuilt in the shadow of disaster.

The foundation of MAGNT hinted that art might soon move from the margins of practical life into the centre of cultural identity. Yet even at this late date, Darwin had no real gallery scene, no critical press, and no local art market. What it had instead was a population beginning to care about its surroundings—not just how they functioned, but how they looked, how they felt, and what they meant.

The years after 1965 would test whether that awareness could translate into a lasting artistic movement. It would take another disaster—of an entirely different kind—to settle the question.

Chapter 5: Cyclone Tracy and the Blank Canvas of 1974

In the early hours of Christmas morning, 1974, Darwin ceased to resemble a functioning city. Cyclone Tracy, a compact but ferocious tropical storm, struck with an intensity that exceeded all expectations—and then erased most of what it touched. Wind instruments registered speeds of 217 km/h before failing. By the time daylight returned, more than 70 percent of the city’s buildings were damaged or destroyed, tens of thousands were homeless, and the city’s physical identity had been largely wiped from the map.

This was not merely a natural disaster. It was a rupture in Darwin’s architectural and cultural continuity. In one night, nearly a century’s worth of built history—already thinned by war, tropical decay, and uneven development—was shattered. The visual archive of Darwin’s civic identity was gutted. The event marked the beginning of a complete reconfiguration of the city’s structure, and, crucially, its aesthetic. Cyclone Tracy forced Darwin to start again—not as an act of will, but as an existential necessity.

A City Dismantled by Force

Tracy’s arrival was violent but deceptively quiet. The small radius of the cyclone’s wind field meant that it concentrated its fury with surgical precision. Homes crumpled as if made of paper. Steel-framed structures twisted in place. The power grid failed. Water and sewerage systems collapsed. Communications with the outside world were severed.

The visual consequences were immediate and overwhelming:

- Streets became rivers of splintered timber, mattresses, fencing, and glass

- Rooftops were sheared clean off and thrown across blocks

- Civic landmarks vanished, reduced to outlines in the mud

It was the most intense meteorological event in Darwin’s modern history, but it was also an obliteration of civic imagery. Darwin’s already fragile visual identity—its postwar tropical modernism, its colonial remnants, its street-level personality—was broken apart in a matter of hours.

A Visual Culture of Absence

In the weeks that followed, Darwin’s most powerful aesthetic was absence. The city’s appearance was defined not by what stood, but by what had vanished. The streets were quieter than they had been in decades—not because of peace, but because of evacuation.

Nearly 30,000 people, out of a population of around 45,000, were relocated in one of the largest peacetime evacuations in Australian history. The remaining population was left to clear wreckage under military supervision. There were no open galleries, no functioning schools, no civic centres. Art, in any ordinary sense, had ceased.

Yet from this destruction, a new kind of cultural awareness emerged—not from what could be created, but from what had to be remembered. Survivors began to write, sketch, and collect. Children drew what they had seen. Journalists recorded oral accounts. Architects and engineers took thousands of photographs, but the most important images were mental ones: a visual memory of loss, against which all future Darwin would be judged.

Architecture as Urgency, Not Expression

The rebuilding of Darwin began almost immediately, but its tone was one of bureaucratic speed, not artistic exploration. The Darwin Reconstruction Commission, formed in 1975, was charged with coordinating the total redesign of the city’s infrastructure and building codes. The goal was clarity, order, and survivability—not style.

This process, though driven by necessity, produced one of the most dramatic urban transformations in Australian history. The new Darwin that emerged was:

- Uniform in height: strict building codes limited structures to cyclone-resistant low-rise

- Materially homogenised: reinforced concrete, steel framing, and cyclone-grade fixings

- Stripped of ornament: designs prioritised airflow, drainage, and impact resistance over aesthetics

The effect on the city’s visual culture was profound. Post-Tracy Darwin was functional, resilient, and visually subdued. The exuberant, ad hoc character that had once defined the city was gone. In its place stood a controlled, rationalist aesthetic that communicated survival first, identity second.

The Role of Public Art in Rebuilding

Despite these constraints, some visual culture returned—slowly, cautiously, and often in service to collective healing. Memorials were built, small and discreet. Schools began commissioning murals to help children process trauma. Local councils supported minor civic artworks that emphasised resilience rather than beauty.

Much of this work was temporary or anonymous. The city’s art scene, such as it had existed before the cyclone, had been decimated. Galleries were closed. Collections were damaged. Artists were displaced or had lost their homes and studios.

But even in the bleakness of reconstruction, fragments of cultural revival began to surface. Visual gestures—commemorative, symbolic, often improvised—hinted at a population trying to restore more than shelter. Creativity had not been killed; it had simply been buried under corrugated iron and salt-stained debris.

Aesthetic Memory in a Flattened Landscape

The real artistic impact of Cyclone Tracy was not in what it inspired, but in what it erased. Before the storm, Darwin had possessed an uneven but growing visual archive: colonial buildings like Brown’s Mart, war relics on the harbour’s edge, rows of fibro houses with their improvised tropical stylings. Tracy obliterated most of these, leaving future generations without the architectural lineage that often anchors local identity.

This rupture produced a kind of amnesia in Darwin’s aesthetic memory. New residents arriving in the 1980s and ’90s had little to connect them to what came before. The city looked new, but not modern; organised, but not expressive. A clean slate, but one scoured clean by force.

In this way, Tracy’s cultural legacy is paradoxical. It enabled a total reimagining of Darwin’s built environment, but it also severed its historical continuum. What art could be made afterward would have to begin from scratch—not just in form, but in meaning.

Chapter 6: Founding Institutions and Local Scenes

Darwin’s relationship with art has never followed the southern model. There was no gold-rush wealth to underwrite galleries, no old-money collectors to build legacies, and no established schools of painting or critical theory to react against. What it had—through long intervals of interruption, disaster, and recovery—was institutional persistence. The art history of Darwin began to crystallize not through a flourishing avant-garde but through the slow establishment of physical spaces: museums, galleries, and multi-use venues that anchored creativity in a city that had, for most of its existence, been structurally unstable.

This chapter in Darwin’s visual life began quietly in the 1960s, with the recognition that the Northern Territory needed a central cultural repository. What followed over the next two decades was the incremental development of institutions that provided both a memory for the city and a platform for its visual imagination.

MAGNT: From Legislation to Loss

The pivotal move came in 1964, when the Northern Territory Administration initiated legislation to create a formal museum board. At the time, this was more symbolic than practical—there was no dedicated building, no full collection, and no consistent funding stream. But the intention was there: Darwin, despite its modest size, would have a place to collect and preserve its natural, maritime, and cultural heritage.

By 1970, a director had been appointed to lead what was to become the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT). Early activities focused on acquiring objects—everything from historical artefacts and natural specimens to maritime relics. While art, strictly speaking, was not the primary emphasis in its initial mandate, visual culture was present from the beginning: curation, exhibition design, and visual documentation were core to its developing identity.

The museum’s first physical location, an improvised site in the old Town Hall on Smith Street, opened to the public in the early 1970s. Though modest, this building represented Darwin’s first real civic attempt to provide cultural space for viewing and reflecting on its past. But its tenure was short-lived. On Christmas Day 1974, Cyclone Tracy demolished the Town Hall and destroyed much of the early collection, leaving only fragments.

The institution survived in name, but its material presence was erased—another cultural reset in a city already marked by discontinuity.

Rebuilding with Purpose: Bullocky Point

Rather than retreat from the loss, the government and local community recommitted to the idea of a central museum. A new, purpose-built facility was constructed at Bullocky Point, overlooking Fannie Bay, far from the vulnerable lowlands of the city centre. The design was functional, cyclone-resistant, and dignified without being grandiose. When it opened on 10 September 1981, it gave Darwin its first permanent cultural institution built not from adaptation or improvisation, but from deliberate design.

The new MAGNT fused multiple mandates: natural history, maritime history, social memory, and—gradually—art. It was not, at first, a gallery in the conventional sense. But as its collections grew, and as a younger generation of artists began to emerge locally, its identity expanded.

By the early 1990s, MAGNT’s scope had broadened significantly. Renovations in 1992–93 included major gallery upgrades and curatorial development. Exhibitions began to include contemporary visual art, regional craft, and experimental media. Though its institutional language remained cautious, the museum had become an art venue by practice, if not always by name.

Outside the Frame: 24HR Art and the Rise of the Contemporary

The appearance of 24HR Art—now known as the Northern Centre for Contemporary Art (NCCA)—in 1989 marked a crucial evolution. Whereas MAGNT emerged from government planning and civic heritage needs, 24HR Art was driven by artists themselves: younger, more mobile, and interested in engaging Darwin with the national and international contemporary art conversation.

Set up initially in a compact space before relocating to a warehouse-style site in Parap, the NCCA provided exhibition opportunities for experimental, time-based, installation, and politically charged work. It became a platform for emerging Northern Territory artists as well as a node in Australia’s broader contemporary art network.

The aesthetic that took root here was strikingly different from MAGNT’s institutional tone. NCCA was open to risk, engaged with conceptualism, and unafraid of confronting Darwin’s often invisible histories—conflict, neglect, and cultural tension. It supported residencies, touring shows, and workshops, creating the kind of ferment that had long been absent from the city’s visual life.

Brown’s Mart: The Civic Stage Endures

While new institutions were taking shape, one of Darwin’s oldest buildings quietly reasserted its cultural role. Brown’s Mart, originally constructed in 1885 as a commercial exchange, had already survived war and weather. By the early 1970s, it had been repurposed as a community arts and performance venue.

Though better known for theatre and music, Brown’s Mart has long played a supporting role in Darwin’s visual arts. It hosted pop-up exhibitions, artist markets, and cross-disciplinary events where painting, performance, and spoken word intertwined. Its presence in the city centre—solid, familiar, and non-institutional—offered a symbolic bridge between colonial legacy and living culture.

Its survival is more than anecdotal. In a city where much of the built environment is transient, Brown’s Mart stands as a kind of architectural memory—one that has sheltered visual culture without needing to formalise it.

The Quiet Formation of a Scene

By the end of the 1980s, Darwin had something resembling an art scene: a public museum with curatorial ambition, an independent gallery with contemporary focus, a civic venue with grassroots engagement, and an emerging cohort of artists making work in studios, backyards, and temporary spaces.

It was not a large scene. Nor was it well-funded. But it was coherent, recognisable, and anchored by place. Darwin’s institutions may have come late, but when they arrived, they grew fast—and with surprising cohesion.

As the 1990s approached, a new question emerged: could Darwin produce artists whose work was not only about the north, but shaped by it? The answer would come in the next generation.

Chapter 7: The Rise of the Darwin Art Scene—1980s and 1990s

By the early 1980s, Darwin had institutions, funding structures, and a small but growing audience. What it lacked was a self-sustaining art scene—a community of working artists, critics, curators, and venues capable of producing and circulating contemporary visual work on its own terms. That changed over the next two decades. Not rapidly, and not always visibly, but steadily. The 1980s and 1990s saw the emergence of a distinct Darwin art scene: regional in its focus, modest in scale, but capable of serious ambition.

This was not a scene born in commercial galleries or elite schools. It was shaped by collectives, converted warehouses, government support, and the practical pressures of living in one of Australia’s most climate-exposed and culturally peripheral cities. The art made in Darwin during these years reflected not just the place, but the conditions under which it was possible to make anything at all.

24HR Art and the Energy of Improvisation

In 1989, a group of artists and curators launched a contemporary art space called 24HR Art in a repurposed petrol station. It was audacious, not because of its scale, but because of what it proposed: that Darwin deserved a dedicated venue for contemporary visual art—experimental, time-based, conceptual, or otherwise unfashionable in traditional institutional settings.

Almost immediately, 24HR Art distinguished itself by its programming. It took risks. It showed work that dealt with political themes, regional identity, and media that had no commercial appeal. It invited artists from other parts of Australia to exhibit in Darwin and supported local artists in developing exhibitions that could travel. This exchange was crucial. It helped situate Darwin not as an isolated outpost, but as a node in a wider conversation—albeit one conducted from the margins.

The following year, 24HR Art relocated to a more stable location in the Parap shopping precinct, a move that allowed it to expand operations and offer more consistent programming. That site—within a former cinema space—would become the home of what is now known as the Northern Centre for Contemporary Art (NCCA).

This development marked a turning point. The Darwin art scene now had a centre—unofficial, underfunded, but real. And with it came something previously absent: continuity.

MAGNT Evolves

Meanwhile, the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT) was expanding its role. Originally focused on natural history and maritime heritage, by the late 1980s and early 1990s it had begun to incorporate contemporary and historical art into its exhibitions. Its curators took interest in regional practices—printmaking, sculpture, textile art, and hybrid forms drawing on Northern materials and visual traditions.

Though MAGNT was a state institution and operated with the expected caution of public museums, it provided critical infrastructure:

- Climate-controlled galleries in a city notorious for heat and humidity

- Long-term storage and preservation for regional collections

- Institutional recognition for artists working outside commercial networks

This was especially important for artists whose work did not travel well, physically or conceptually. MAGNT gave them a context—both professional and historical.

Place as Material, Not Metaphor

One of the defining features of Darwin art in this period was its embeddedness in place—not in a thematic or romantic sense, but materially. Artists adapted to local conditions in ways that shaped what they made. Canvas warped in the humidity. Paint cured differently. Outdoor sculpture required weather resistance. Travel was expensive, so local materials were reused.

This led to a kind of aesthetic pragmatism:

- Found-object sculpture using maritime scrap and salvaged materials

- Printmaking on paper types that could handle moisture and heat

- Collaborative works with craftspeople and technicians who understood regional logistics

Artists in Darwin had to solve problems before they could make statements. This lent their work a kind of embedded discipline. Even when addressing broad or conceptual themes, their art had the marks of the north: rougher textures, brighter pigments, hardened edges.

A Scene with No Stars

What Darwin’s art scene lacked was a hierarchy. There were few commercial galleries, fewer collectors, and almost no critical press. This meant artists did not compete for dominance; they collaborated, supported, and co-existed. Brown’s Mart Theatre continued to offer space for exhibitions, cross-disciplinary events, and cultural gatherings. Artists showed work in schools, council buildings, and shopfronts. The lack of a centre—commercial or critical—freed artists to explore without the expectation of recognition or market validation.

Some artists left for better opportunities down south. But many stayed. They taught, exhibited, and built small networks. The emphasis was on presence over prestige. Art in Darwin was not a career ladder; it was a practice of staying put and making do.

Moments of Recognition

Despite its isolation, Darwin’s art scene did not go unnoticed. Artists affiliated with 24HR Art were included in national touring shows. NT-based work began appearing in catalogues and publications about regional Australian art. Curators from larger cities began to take interest, especially in the experimental or material-based work that reflected Darwin’s climate and spatial eccentricities.

Notably, the 1990s saw the rise of printmaking as a respected regional practice—supported by both MAGNT and local workshops. This medium, adaptable and portable, lent itself to Darwin’s conditions and became a staple of exhibitions both in the city and beyond.

The Pressure of Identity

Though the Darwin art scene avoided overt identity politics, the question of regionalism hovered. Was Darwin art simply “art from Darwin,” or did it have its own logic, its own style? There was no single answer. But by the end of the 1990s, a consensus had formed: art made in Darwin mattered—not just because of where it came from, but because of what it had to do to exist at all.

The 1980s and 1990s had turned Darwin from a city with art into a city with an art scene. What came next would test that scene’s durability: new funding pressures, generational shifts, and the challenge of connecting to Asia without being culturally absorbed by it.

Chapter 8: Asian Crosscurrents

Darwin faces north—not just geographically, but conceptually. Its orientation has always been toward Asia, not as an abstract regional identity but as a physical and cultural fact. The city sits closer to Timor-Leste than to Sydney, and less than 700 kilometres from Indonesia’s southernmost islands. This proximity is not merely cartographic; it shapes trade, politics, demographics, and art.

From the 1980s onward, as Darwin’s art institutions matured and its cultural infrastructure stabilised, the potential for regional exchange began to surface in serious ways. The art scene, which had once existed in near-total isolation, now found itself at the edge of something larger—a network of cultural flows that extended through Indonesia, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Timor, and Southeast Asia at large. These currents did not arrive all at once. They built slowly, through residencies, exhibitions, migrations, and the quiet persistence of geography.

A City with an Asian Horizon

Darwin’s role as Australia’s “gateway to Southeast Asia” has often been cast in strategic or economic terms—export corridors, shipping routes, defence logistics. But it has also brought a degree of cultural porosity. Asian festivals, food markets, and religious institutions have long been part of the city’s civic rhythm. So too have artistic traces: lantern parades, fabric traditions, martial-arts performance forms, and decorative motifs with Chinese, Malay, or Timorese roots.

Historically, the most visible Asian presence in Darwin was its Chinese community, which had formed in the late 19th century and flourished until the bombing of Darwin in 1942 destroyed much of the city’s original Chinatown. That physical erasure did not entirely sever the cultural connection. Family networks, culinary traditions, and business ties continued. These early precedents set the stage for the more layered intercultural exchanges that would develop in Darwin’s art scene by the late 20th century.

Institutional Reflections of a Regional Outlook

By the 1990s, both of Darwin’s main art institutions—the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT) and the Northern Centre for Contemporary Art (NCCA)—began to look northward with greater deliberation.

At MAGNT, this took the form of collection building and exhibition programming that reflected Darwin’s regional context. The museum acquired Southeast Asian textiles, maritime artefacts, and ritual objects—partly to reflect the territory’s broader cultural matrix, but also to acknowledge the city’s specific links to the Timor and Indonesian archipelagos. Its exhibitions on boatbuilding, navigation, and coastal culture often blurred the line between ethnography and art, treating craft traditions with the same curatorial care as fine art.

At NCCA, the outlook was more explicitly contemporary. Artists from the Philippines, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea were invited to exhibit. Residency programs allowed for two-way movement—Darwin artists working in Asia, and Asian artists producing work in Darwin. These exchanges often produced hybrid works: photographic series set in the tropics, installations incorporating found objects from both locales, performances that mixed regional idioms with Australian art-world forms.

The Art of Translation and Tension

Cross-cultural work is rarely frictionless. Artists engaged in these dialogues found themselves navigating linguistic, political, and conceptual divides. In some cases, there was a risk of exoticism—Australian artists projecting their interpretations onto unfamiliar cultures. In others, there was productive tension: artists from Indonesia or Timor working in Darwin were free to interrogate Australia’s self-image, often through subtle or oblique means.

One defining feature of this exchange was material resonance. The climates of Darwin, Dili, and Denpasar are not merely similar—they demand similar strategies. Artists from across the region worked with natural fibres, tropical woods, metal salvaged from boats, or pigments derived from earth and plant sources. These choices were not symbolic; they were pragmatic. And yet they carried meaning—anchoring aesthetic practice in a shared environmental logic.

Three recurring artistic strategies emerged from this regional dialogue:

- Portable forms: works that could be packed, transported, and reassembled across borders—print portfolios, textiles, and modular sculpture

- Collaborative residencies: joint exhibitions in which artists responded to shared environments or constraints, rather than themes imposed from above

- Tropical minimalism: an aesthetic of paring back—not out of stylistic preference, but in response to climate, cost, and resourcefulness

Demographic Texture and Everyday Art

Alongside formal exchange programs and institutional shows, Darwin’s population itself contributed to the growing presence of Asian influence in the arts. The city’s residents include families with roots in Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Many are not artists, but they participate in cultural life through festivals, craft traditions, culinary events, and informal networks.

Art, in Darwin, has always had a strong community dimension. School murals, council-backed workshops, and arts festivals often include references—visual, musical, or symbolic—to Asian traditions. These are not acts of appropriation. They are expressions of a shared civic life.

In this context, the distinction between “local” and “foreign” art becomes harder to draw. A textile artist who uses Javanese batik techniques but lives in Darwin is neither an outsider nor an emissary. They are simply part of the evolving visual language of the city.

Regionalism Without the Centre

One of the unique aspects of Darwin’s engagement with Asia is its decentralised character. Unlike cultural exchange driven by embassies or university programs, this was a relationship shaped by proximity, accident, and persistence. It was more horizontal than hierarchical—based on practical collaboration rather than institutional prestige.

This has shaped the tone of the work produced. There is little grand theory, little attempt to synthesise cultures under a conceptual banner. Instead, there is adaptation, juxtaposition, and experimentation. Artists work in multiple languages—visually and verbally. They exhibit in warehouses, converted cinemas, open-air markets. The work is often ephemeral, shaped as much by environment as by intent.

In Darwin, the Asian crosscurrent is not a trend or a curatorial thesis. It is the normal condition of living and working at a cultural frontier. And in that condition, art doesn’t just cross borders. It changes shape.

Chapter 9: The Materials of the North

Artists in Darwin do not merely choose their materials—they inherit their constraints. In a city where monsoonal rains, tropical heat, salt-laden air, and cyclonic winds shape the lifespan of every surface, art cannot escape its climate. Materials that hold steady in Melbourne galleries or Sydney studios behave differently in the Northern Territory. Canvas buckles, glue delaminates, paint fades or bubbles, timber splits, and metals rust with startling speed. In this environment, every artistic decision becomes a negotiation with nature.

For generations, artists in Darwin have responded not with complaint but with adaptation. The materials of the north are not always traditional, nor are they chosen for aesthetic effect alone. They are selected for what they can withstand—and in many cases, for what the landscape itself provides.

Humidity as a Design Constraint

Darwin’s tropical savanna climate brings two dominant seasons: a long, punishing dry, and a wet season marked by humidity levels above 80%, often for months at a time. These conditions are not incidental; they define what can be made, displayed, or preserved. Paper warps. Wood swells. Acrylic paints become tacky. Archival standards are difficult to maintain without climate-controlled environments, which many smaller studios and galleries cannot afford.

Artists in the north, therefore, must think like engineers. They work with fast-drying mediums. They avoid adhesive-based constructions unless they can test their resilience. They build for exposure, not just exhibition. This practical constraint becomes, in time, a style.

Environmental Pragmatism in the Built Environment

The logic that governs Darwin’s architecture also informs its visual art. Houses are raised on stilts for airflow. Breezeways and latticework replace heavy insulation. Cyclone codes demand materials that flex or shatter safely. The city’s visual character, in both public and private spaces, is defined by its weather-responsiveness.

This ethos has seeped into artistic practices. Sculpture and installation work is frequently made from:

- Galvanised steel or aluminium (to reduce corrosion)

- Polycarbonate and plastic components (which withstand tropical rain)

- Locally harvested or reused materials that reflect the environment they emerge from

The point is not to aestheticise weather but to coexist with it. The act of creating in Darwin means accepting the ephemerality of materials. Nothing lasts. Even indoor exhibitions must account for mold, salt, and insects. Durability is not assumed—it must be earned.

Winsome Jobling and the Paper of Place

One of the most distinctive responses to Darwin’s material environment is found in the work of Winsome Jobling, a long-time Darwin-based artist known for making handmade paper from local grasses and fibres. Her process is not simply ecological; it is conceptual. She gathers pandanus, speargrass, banyan roots, and other native materials, pulps them by hand, and transforms them into sheets that carry both visual and botanical memory.

In works like Bush Vanitas (2011), Jobling layers these papers into sculptural wall pieces that evoke erosion, decay, and regrowth. The materials age naturally—some yellow, others fade, a few begin to fray—making each work a slow participant in its own decomposition.

Jobling’s art exemplifies a central aesthetic of the north: a refusal to separate material from environment. Her paper is not neutral substrate. It is habitat, narrative, and warning.

Rock, Salt, and Mangrove

Darwin’s relationship to natural materials also extends to its proximity to stone and earth art—particularly the long legacy of rock painting in the Top End, which predates European arrival by tens of thousands of years. These works, many located in sites across Kakadu and Arnhem Land, have suffered from the same environmental stresses that challenge contemporary artists: humidity, salt crystallisation, biofilm buildup, and mineral decay. Conservationists and archaeologists working in the region treat material degradation as both a technical and symbolic issue: art in this part of the world disappears unless constantly tended.

This awareness has filtered into Darwin’s urban art consciousness. In recent years, artists have explored the visual languages of mangrove ecologies, tidal erosion, and salt crystallisation. Installations incorporate shells, driftwood, sand, and resin. Materials are not chosen for purity but for their local character. Their weathering is often embraced as part of the piece’s life cycle.

A notable example is the recent Darwin mangrove art project exhibited in 2025, which invited artists to respond to the tidal wetlands that surround the city. Works included cast mangrove roots, textile prints dyed with saltwater pigment, and sound recordings embedded in resin blocks. The exhibition was not about nature—it was made from it.

Printmaking in the North

Despite the fragility of paper, printmaking has flourished in Darwin, particularly in the form of linocut, screenprint, and relief techniques. The key is not what is printed, but how it’s printed. Northern Territory artists have adapted methods to suit the climate: printing on heavier archival stock, using inks with low sensitivity to moisture, and drying works in tightly timed windows to prevent smearing or mold.

Studios have developed techniques that blend traditional forms with tropical practicality. Ink formulations are modified; presses are stored with desiccants. The result is an understated technical ingenuity—processes designed not for spectacle, but survival.

Future Heat, Future Risk

As climate change accelerates, Darwin is projected to experience even greater extremes: longer hot periods, higher humidity, more intense storms. For artists, this raises new questions. Can a painting survive in an unairconditioned studio? Will public sculpture endure another century of UV exposure and salt-air corrosion? Are traditional framing and conservation methods obsolete in this part of the world?

Some artists have begun to respond preemptively. They build collapsible works. They display using modular formats that allow for retreat and repair. Others work directly with weather, allowing their pieces to transform over time—sun-bleached, water-stained, wind-scored. These are not metaphors. They are facts.

The Aesthetic of Adaptation

The materials of Darwin’s art scene are not chosen from catalogues. They are gathered, repurposed, risked. The city’s aesthetic is one of adaptive realism—art that accounts for climate not as a backdrop, but as a co-author. This lends the visual culture of the region a groundedness that is rare elsewhere. It also makes it fragile, contingent, and hard to transport.

But perhaps that is the point. In a place where nothing stands still, permanence is not the ambition. Survival is. And in Darwin, that survival takes shape in saltproof metals, handmade fibres, experimental adhesives, and the knowledge that every work will eventually be touched—and changed—by the air.

Chapter 10: Art in Public Life

Darwin’s art is not confined to galleries, nor is it cloistered behind glass. It’s on the street walls, underfoot in parks, layered onto water tanks, tucked into breezeways, and embedded in the shoreline. Public art in Darwin is not just decorative—it’s infrastructural. It shapes how the city is used, remembered, and moved through. Unlike larger capital cities, where prestige collections dominate the art landscape, Darwin’s visual culture is outward-facing, informal, and frequently encountered by accident.

In a city often rebuilt from scratch—by war, by cyclone, by policy—the public realm has always mattered. It is where culture meets function, and where visual expression becomes part of civic identity. Over time, this has made Darwin one of the most visually distinctive public environments in Australia—not because of monumental scale, but because of how art permeates the everyday.

Walls That Speak: The Darwin Street Art Festival

The most visible expression of this permeation is the Darwin Street Art Festival, launched in 2017. In just a few years, it has transformed dozens of blank walls, laneways, and service corridors into large-scale mural surfaces. More than 120 murals now animate the CBD and fringe suburbs—most painted by local artists, some by interstate or international guests.

These are not mindless splashes of colour. They are curated, site-specific works that respond to the architectural quirks, histories, and uses of their host locations. Some address Darwin’s military past. Others reference tropical flora and fauna. A few are abstract interventions in harsh urban geometry. What unites them is accessibility. Anyone walking through the city is a viewer. No ticket required.

The effect has been cumulative. Walls once ignored now attract foot traffic. Alleyways have become detour-worthy. Local businesses report that street-art trails bring new customers. For many residents, these murals are now more familiar than traditional artworks in institutional collections. They are navigational as much as cultural.

Utility and Expression: Tanks, Ovals, and Infrastructure

Public art in Darwin extends beyond walls. In September 2025, the City of Darwin unveiled a set of commissioned artworks on irrigation tanks and public park infrastructure in suburbs like Anula and Wulagi. These cylindrical tanks—normally anonymous and purely functional—were transformed by local artists into sculptural landmarks, each painted to reflect community themes, natural cycles, or the built environment.

This kind of intervention is significant. It reflects a municipal commitment to embedding art into the utility landscape—not as an afterthought, but as a civic gesture. In a city where infrastructure is often exposed, and where climate discourages elaborate landscaping, visual interventions like these offer both colour and care. They signal that Darwin’s suburbs are part of the cultural imagination, not just the central precinct.

The Waterfront as Civic Canvas

Perhaps the most successful integration of art, design, and public space in recent years has occurred at the Darwin Waterfront Precinct. This redeveloped harbourside area—complete with walking paths, swimming lagoons, cafes, and performance areas—functions as both leisure zone and visual experience. Sculptural installations appear along the esplanade. Pavement designs incorporate motifs drawn from local history. Lighting design responds to art as much as safety.

Here, art is not added. It is built in. And the result is a rare example of city planning that treats visual culture as a structural, not supplementary, element.

Three core characteristics define this kind of public-space art in Darwin:

- Climate-conscious materials: artworks are made from steel, stone, or weather-resistant composites

- Participatory scale: pieces are large enough to see from a distance, but detailed enough to reward close inspection

- Civic humility: most are unsigned, untitled, or embedded in functional structures—inviting attention without demanding it

Memory Anchored in Parks

Darwin is a city that remembers through space. Its public parks, especially Bicentennial Park, house monuments that recall the bombing of Darwin, wartime service, and the loss of civilian life. These memorials—most relocated or built in the early 1990s—are simple, durable, and sober. Stone obelisks. Bronze plaques. Flagpoles flanked by low retaining walls.

They do not compete with contemporary public art. Instead, they form a parallel layer of visibility—formal memory embedded in civic space. Visitors may pass a mural, a playground, and a war memorial in the span of a few metres. This coexistence of past and present, play and grief, is not accidental. It reflects Darwin’s unusual civic history: a place repeatedly interrupted, and repeatedly rebuilt.

Brown’s Mart and the Continuity of Performance

One of the oldest cultural landmarks in Darwin, Brown’s Mart, continues to anchor community art and performance. Originally built in 1885, the building has housed a variety of civic functions. Since the 1970s, it has operated as a performance and exhibition venue, welcoming visual artists, musicians, and public events.

Its presence is critical. In a city where many buildings are transitory, Brown’s Mart offers both a literal and symbolic foundation. Artists know it. Audiences trust it. It hosts temporary exhibitions and collaborative projects that spill into the surrounding precinct. Its longevity is a reminder that public culture in Darwin doesn’t always need to be re-invented. Sometimes, it just needs to be housed.

MAGNT and the Public Face of the Museum

While the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT) is a formal institution, it participates fully in Darwin’s public art landscape. Its location—perched above the harbour at Bullocky Point—is visually prominent. Its exhibitions, often drawing on maritime, natural history, and regional art, are designed for broad accessibility. School groups, tourists, and residents interact with the museum not as a bastion of elite taste, but as part of civic life.

Temporary exhibitions often include outdoor components. The maritime galleries connect directly to the city’s port history. Sculptures are positioned to frame the sea. Even the museum’s café terrace offers curated views—visual experience as part of public space.

In this way, MAGNT is not separate from Darwin’s public art; it is its institutional heart. But unlike major southern museums, it does not sit above the scene. It is part of it.

Art Without Thresholds

Public art in Darwin thrives because it crosses thresholds. It does not require intention. It does not require expertise. It asks only that one be present—in a park, on a walk, by a fence, near a school, or sitting beside a painted tank. This is not to say that the work is simple or unworthy of critique. Many pieces are ambitious, politically loaded, or technically sophisticated. But their mode of presentation is democratic. Darwin’s public art is not a statement; it is a conversation held in full daylight.

In a city defined by resilience, destruction, and reinvention, public art offers something rare: a sense of the continuous. It says, without pretense, “We are still here—and here is what we’ve made.”

Chapter 11: Collectors, Markets, and the Business of Art

Darwin’s art scene was never built for the market. It evolved instead as a civic project—rooted in institutions, communities, and necessity. But as the local infrastructure matured and Darwin became more visible in national cultural networks, the question of value—economic, not just aesthetic—inevitably followed. Who buys art in Darwin? Who sells it? What determines what gets preserved, and what gets forgotten?

The answers are not simple. Darwin exists on the far edge of Australia’s commercial art network. Its collectors are few. Its commercial galleries are modest. And much of the art produced in the region—especially in remote areas—is sold far from where it’s made. Yet despite these limitations, Darwin plays a significant role in the economy of Australian art, particularly through its connection to Aboriginal art markets, its institutional infrastructure, and its festivals.

The Aboriginal Art Market: Centre Stage in August

Each year in August, Darwin becomes a temporary capital of the Aboriginal art world. The Darwin Aboriginal Art Fair (DAAF) brings together more than 70 Indigenous-owned art centres from across Australia, showcasing thousands of artworks under a single roof. In 2025, the fair recorded AU $5.1 million in sales, its highest total to date.

The event is more than a market—it is a confluence of culture, commerce, and visibility. Artists travel from Arnhem Land, the Kimberley, and the Central Desert. Collectors arrive from Sydney, Melbourne, and abroad. For a brief window, Darwin becomes the hub of a national—and increasingly global—market.

Yet the art sold at DAAF rarely originates from Darwin itself. It is produced in remote communities hundreds or thousands of kilometres away, where art centres operate as both studios and economic lifelines. The fair allows these communities direct access to buyers, bypassing exploitative dealers and ensuring artists retain control over pricing and narrative.

In this way, Darwin is a platform, not a producer. Its market function is logistical and symbolic—a meeting point rather than a manufacturing site.

Structural Inequality in the Market

Behind the success of events like DAAF lies a more complex economic landscape. Research into the remote Indigenous art economy shows a steep imbalance: a small number of well-established art centres account for the majority of sales, while many smaller or less-connected artists make little more than subsistence income.

For Darwin-based artists—whether Indigenous or not—the challenge is different. They must navigate a small, irregular local market with few private collectors and limited commercial infrastructure. Unlike in Sydney or Melbourne, there are no high-end galleries regularly selling work into corporate collections. Pricing is cautious. Sales are sporadic. Many artists support themselves through teaching, commissions, or unrelated work.

This scarcity has a shaping effect. Artists often scale their work to what they believe will sell locally—affordable prints, small paintings, works on paper rather than large canvases or ambitious installations. Some opt out of the market entirely, producing work for festivals, public commissions, or institutional exhibitions where sales are not expected.

The Role of Institutions in Market Formation

In the absence of a robust private market, institutions shape taste. The Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT) is the most influential buyer in the city. Its acquisitions determine what enters the region’s public memory. Its exhibitions provide legitimacy and exposure. Artists shown at MAGNT, even in modest roles, often find their work elevated in profile.

Yet institutional validation is not always matched by financial gain. MAGNT, like most public museums, acquires selectively and infrequently. It cannot act as a market substitute. The same is true of the Northern Centre for Contemporary Art (NCCA), which plays a vital curatorial role but operates without a commercial mission.

This leaves independent galleries and artist-run spaces to fill the gap. Darwin has a small number of these—pop-up shops, studio-showrooms, weekend markets—but none with the consistent sales traffic or collector base needed to sustain a full-time artist economy.

The Tourist Market and Its Limits

Tourism does offer some market exposure. Visitors often purchase prints, paintings, and souvenirs from city galleries or airport shops. But this sector tends to reward familiar visual tropes: sunsets, dot paintings, crocodiles, landscapes. Artists seeking deeper conceptual or experimental work find little traction here. The line between art and product is sharply drawn—and rarely crossed.

Some artists compromise by maintaining separate streams of work: one for sale, one for practice. Others find the split untenable and retreat into private production, waiting for rare opportunities to show in curated exhibitions.

Three market paths tend to exist for Darwin artists:

- Institutional recognition, leading to grants or acquisitions (but not necessarily income)

- Commercial sales, largely to tourists or local government commissions

- Festival and public-event exposure, which offers visibility without guaranteed return

None of these paths is stable. Most artists work across all three, adapting strategies as opportunities arise.

Market as Story: What Gets Bought, What Gets Remembered

Every market is also a form of storytelling. What sells is preserved, re-shown, cited, and collected. What does not often disappears. In Darwin, this process is visible in the city’s shifting visual memory. Art that aligns with narratives of place—tropical colour, regional identity, environmental themes—tends to find a home, whether in a private collection or public space. Art that resists those frames—minimalist, conceptual, confrontational—has a harder path.

Yet the market is not static. The success of the Aboriginal art economy, the emergence of new regional collectors, and the growing visibility of Darwin-based artists in national contexts have begun to shift the landscape. More buyers are appearing who understand the specificities of place. Institutions outside the Northern Territory are showing interest in artists whose work is shaped by climate, distance, and material scarcity.

This could mark the beginning of a broader reevaluation: not just of what Darwin’s artists make, but of what their work represents in the Australian art economy.

Chapter 12: Today and Beyond — Art in Darwin Now

Darwin’s art scene in the present day does not resemble that of any other Australian capital. It is smaller, yes—more remote, less profitable, and often less documented. But it is also remarkably intact. The city has sustained a continuity of artistic practice across catastrophe, climate, and cultural indifference. What now exists is a scene grounded in place, sharpened by necessity, and increasingly connected to regional and global networks.

This is not a boom-time moment. There is no art-fair glitz, no property developers funding speculative installations. Instead, Darwin’s contemporary art is marked by steady expansion, cautious experimentation, and deepened ties to the landscape—geographic, social, and cultural.

A Scene That Grew Slowly, Then Settled

Over the past two decades, Darwin has moved from the periphery of national attention to a distinct space within it. Its institutions—the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT) and the Northern Centre for Contemporary Art (NCCA)—are no longer fledgling. They are mature, stable, and active. MAGNT continues to expand its programming, hosting exhibitions that blend natural history, Indigenous practice, and contemporary visual art with equal seriousness. NCCA has grown into a platform for experimental and boundary-pushing work, while maintaining ties with local practitioners and regional themes.

Public art has flourished. From civic commissions in suburban parks to the large-scale murals of the Darwin Street Art Festival, visual culture is now part of the city’s urban skin. Community support for these efforts is strong—not just institutionally, but in the broader public sphere. Darwin has, in quiet increments, become a city where art is expected to appear in everyday life.

New Media in the North

While traditional forms—painting, printmaking, and sculpture—remain strong in Darwin, there has been an unmistakable shift toward media-based practice. Photography, video, and site-responsive installation have become common modes for artists working in the region. These media allow for flexibility, portability, and responsiveness to environment—all necessary traits in a place where materials are costly, humidity is relentless, and audiences are small but attentive.

Some artists incorporate sound and projection, using solar-powered devices to stage outdoor works that align with seasonal rhythms. Others work in video essay form, exploring climate change, local memory, and inter-regional exchange. These practices are not digital for fashion’s sake—they emerge from constraints. Media art in Darwin is a tool of engagement, not escape.

Three common traits of these practices stand out:

- Temporal sensitivity: works tied to monsoon season, tidal cycles, or light patterns

- Ecological awareness: art as a mode of witnessing environmental change

- Low-infrastructure resilience: designed to function outside formal gallery conditions

This is not art made for white walls. It is made for weather, movement, and adaptation.

The Local as a Form of Commitment

Darwin artists today are not regional by accident. Many have chosen to remain in the city—or to return after study—despite limited market rewards. Their work often reflects this decision: grounded, process-driven, resistant to trends. Some work primarily in community contexts, using workshops, schools, and festivals as both medium and audience. Others develop long-term projects that unfold slowly, shaped by the seasons and cycles of the Top End.

Examples abound:

- A printmaker collaborating with bush-food harvesters to produce scent-infused paper

- A sculptor whose works decay slowly in the mangroves, tracked via drone and exhibited only after collapse

- A video artist filming monsoonal rainfall through abandoned domestic sites, narrating seasonal loss

These artists are not pursuing novelty. They are working in and with time. Their art is a form of attention.

Darwin as a Regional Node

Darwin’s geographic position remains a strategic advantage. Its connections to Southeast Asia and the Pacific have grown stronger in recent years, thanks to artist residencies, cultural exchanges, and joint exhibitions. Artists from Timor-Leste, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea show work in Darwin and take Darwin artists back with them. These exchanges are often informal, built through individual initiative rather than institutional mandate.

Unlike the soft-power model of cultural diplomacy often practised in major cities, these exchanges are modest and peer-led. They reflect shared concerns: rising seas, disappearing languages, climate migration. Darwin artists are not looking south for validation; they are looking sideways, across waters and seasons, toward neighbours.

This shift is crucial. It places Darwin not as Australia’s far north, but as a centre in its own region—culturally, politically, and artistically.

Challenges That Persist

Despite this maturity, challenges remain. The art market is shallow. Funding is limited. Professional development opportunities are sparse. Young artists often leave to train elsewhere and do not return. Many local artists work without formal gallery representation, navigating uncertain pathways between festivals, community projects, and grants.

Climate change adds another pressure: rising temperatures, intensifying storms, and increased infrastructural fragility make long-term planning difficult. Art made outdoors is increasingly exposed to degradation. Digital archiving and hybrid formats may offer solutions, but they require resources Darwin doesn’t always have.

Institutionally, there is still no art school in Darwin comparable to those in other capital cities. Training happens piecemeal—through workshops, residencies, or informal mentorship. This makes the scene fragile. It depends on the continued presence of a small number of dedicated practitioners and administrators.

What Darwin Art Is, Now

Darwin art today is not defined by medium or market. It is defined by orientation—to weather, to place, to material, to region. It is often slow. Often quiet. Often unseen outside the Territory. But it carries a confidence that comes not from prestige, but from persistence. In a culture defined more by continuity than acclaim, that may be its strength.