Cubism stands as one of the most innovative and influential art movements of the 20th century, fundamentally reshaping artistic expression. Pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in the early 1900s, Cubism introduced a new way of seeing, one that defied conventional perspective. By fragmenting forms and presenting multiple viewpoints within a single image, Cubism aimed to capture the complexity of reality. This movement wasn’t just about creating visually striking compositions; it reflected a shift in how artists thought about perception, time, and space.

In Cubist works, traditional subject matter—landscapes, still lifes, portraits—took on a fragmented, almost puzzle-like appearance, inviting viewers to engage actively with the piece by piecing together its components. Rather than presenting reality as a single snapshot, Cubism offered a multilayered experience, making art more interactive and engaging.

Origins of Cubism: Early 20th-Century Paris

Cubism was born in Paris, a city that, at the turn of the 20th century, was buzzing with intellectual and artistic energy. This era of rapid industrialization, technological advancements, and social change sparked a reevaluation of reality and representation. The traditional art that emphasized realism and fixed perspective seemed increasingly out of sync with a world in motion. Artists were grappling with new ways to depict this dynamic, interconnected reality.

Paul Cezanne’s posthumous works greatly influenced this new movement. Cezanne’s approach to form—simplifying natural objects into basic geometric shapes and reimagining perspective—laid the groundwork for Cubism. His insistence on viewing nature through the lens of cylinders, spheres, and cones encouraged artists to explore forms from multiple angles. Picasso and Braque, inspired by Cezanne’s theories, took this idea further by breaking subjects into fragmented forms, allowing viewers to see multiple sides of an object at once. Additionally, Picasso’s exposure to African masks and sculptures, with their stylized and abstract forms, reinforced his interest in abandoning traditional Western perspectives.

Defining Characteristics of Cubism

Cubism fundamentally shifted the principles of art, focusing on abstraction, geometry, and the deconstruction of form. Rather than creating realistic, single-viewpoint representations, Cubist artists aimed to depict subjects as if they were viewed from multiple angles simultaneously. This meant that familiar objects—musical instruments, faces, bottles—appeared as fragmented shapes, layered in ways that suggested depth and motion without actually using conventional perspective.

Color in early Cubism, especially in Analytic Cubism, was kept intentionally muted, often dominated by earthy browns, grays, and ochres. This subdued palette encouraged viewers to focus on form and composition rather than being drawn into colorful distractions. Instead of using shading to create depth, Cubist artists used contrasting planes and overlapping shapes to build a sense of volume. This approach made Cubist art less about representing an object and more about exploring the process of seeing itself.

Two Phases of Cubism: Analytic and Synthetic

Cubism evolved in two distinct phases, each reflecting a different approach to deconstructing reality.

Analytic Cubism (1908-1912) was the movement’s early phase, where artists focused on breaking down objects into geometric fragments, examining their internal structures. In works like Braque’s Violin and Palette and Picasso’s Girl with a Mandolin, objects are dissected into overlapping planes, with limited color to emphasize the structural forms. The intention was to analyze and “rebuild” the subject in a way that revealed its essence, emphasizing form and structure over realistic detail.

Synthetic Cubism (1912-1919) marked a shift towards building up images through collage, texture, and color. Here, artists began to introduce different materials into their paintings, such as newspaper clippings, fabric, and patterned paper. This collage technique expanded the vocabulary of Cubism, incorporating elements of popular culture and everyday objects. Picasso’s Guitar and Braque’s Fruit Dish and Glass exemplify Synthetic Cubism, with their dynamic combination of texture, color, and form. Unlike Analytic Cubism, which dissected objects, Synthetic Cubism pieced them together, creating more playful, vibrant compositions.

Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque: The Collaborative Genesis of Cubism

Picasso and Braque’s collaboration was central to the development of Cubism. Often working side-by-side in Parisian studios, they developed a creative dialogue that pushed each other to experiment and evolve. Their friendship was unique: they would view each other’s works almost daily, discuss techniques, and continually challenge one another. This relationship led to a remarkable period of innovation, as they created works that seemed almost interchangeable in style and approach.

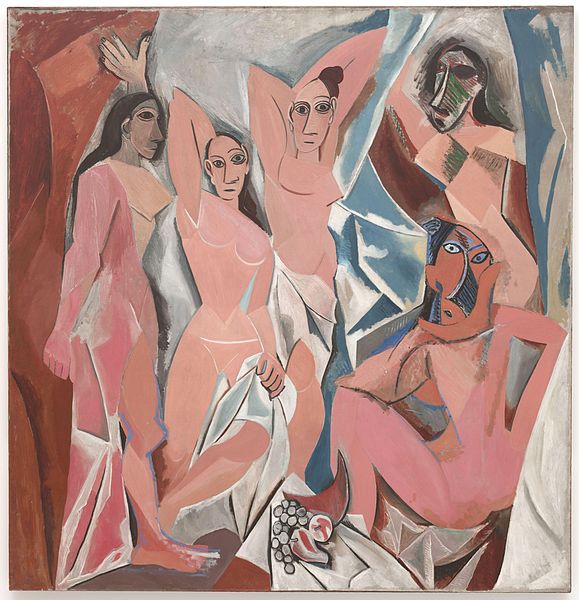

One of Cubism’s earliest landmarks was Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, a provocative painting that depicted five women with distorted, mask-like faces inspired by African art. This work shattered conventional beauty standards and marked the beginning of Cubism’s break with traditional form. Braque responded with Houses at L’Estaque, further exploring fragmented perspectives. Through this back-and-forth dialogue, Picasso and Braque established the foundational techniques of Cubism.

Cubism’s Influence on Other Art Forms

The influence of Cubism extended beyond painting, touching fields as diverse as sculpture, literature, architecture, and music. In sculpture, artists like Alexander Archipenko and Henri Laurens applied Cubist principles by creating fragmented, geometric forms that echoed the paintings of Picasso and Braque. Cubist sculpture introduced a new way of understanding volume and space, presenting figures from multiple angles.

In architecture, the geometric simplicity and abstraction of Cubism influenced movements like Art Deco and Brutalism, where the play of shapes and the use of raw materials created dynamic forms that mirrored the fragmented aesthetic of Cubism. Writers like Gertrude Stein adopted a Cubist approach in literature, employing repetitive and fragmented language to mimic the deconstruction seen in Cubist art.

Even music reflected Cubist ideas, as composers like Igor Stravinsky used fragmented, layered sounds to create compositions that defied conventional harmony and structure. Cubism’s challenge to traditional forms resonated across artistic disciplines, encouraging creators to question and reinvent established norms.

Cubism’s Legacy: Global Spread and Lasting Impact

Cubism quickly spread beyond Paris, reaching artists and galleries across Europe and North America. Its impact was particularly strong in countries like Spain, Italy, and Russia, where artists embraced the movement’s radical approach to form and space. In Italy, for example, Futurist artists like Umberto Boccioni adopted Cubist techniques to convey movement and dynamism. In Russia, Constructivists were influenced by Cubism’s geometry and abstraction, applying its principles to political art and industrial design.

The legacy of Cubism can also be seen in later art movements such as Abstract Expressionism and Surrealism. Surrealists, inspired by Cubism’s exploration of fragmented reality, incorporated its techniques into their dreamlike compositions, while Abstract Expressionists took Cubism’s bold forms and colors to new emotional extremes. Major exhibitions in the 1930s and 1940s solidified Cubism’s place in art history, showcasing its innovations and highlighting its enduring influence on modern art.

Famous Works in Cubism

Cubism produced several iconic works that continue to fascinate and challenge audiences.

- Les Demoiselles d’Avignon by Picasso: This painting is often cited as the first Cubist work, with its angular, mask-like faces and bold composition. It shocked early viewers and laid the groundwork for Cubist abstraction.

- Ma Jolie by Picasso: An example of Analytic Cubism, this painting depicts Picasso’s muse, Eva Gouel, abstracted through geometric planes, challenging viewers to identify the figure within the composition.

- The Portuguese by Braque: This piece epitomizes Analytic Cubism with its fragmented representation of a musician. Braque uses overlapping planes and stenciled letters, merging form and language.

These masterpieces exemplify Cubism’s innovative approach to deconstructing reality, pushing viewers to engage actively with each composition.

Criticism and Controversy Surrounding Cubism

Cubism faced significant backlash when it first appeared. Many critics found it incomprehensible, even ugly. Traditional art institutions rejected Cubist works, viewing them as a betrayal of aesthetic beauty and technical skill. Some critics dismissed Cubism as a fad, predicting it would fade as quickly as it had appeared. However, this controversy only fueled the movement, attracting artists who were intrigued by its bold break from tradition and its intellectual approach to form and composition.

Cubism’s influence reverberates through the art world to this day. By breaking down reality and reassembling it through fragmented forms, Cubism changed how we view art and experience visual culture. Its legacy lives on, from graphic design to digital media, proving that the questions Cubism posed about perspective and perception remain as relevant as ever. Cubism isn’t merely an art movement; it’s a way of seeing, an approach to understanding complexity, and a testament to the endless possibilities of human creativity.