The artistic identity of Christchurch began not with a canvas but with a cathedral plan. Before brush met board, stone met chisel. In the 1850s, the settlers of the Canterbury Association arrived with not only religious conviction but architectural blueprints—and those blueprints shaped the earliest visual culture of the city in profound and enduring ways.

Imported identities: English ecclesiastical styles in a new land

Christchurch was conceived as an Anglican utopia. This wasn’t merely a question of religion; it was a visual and social project that entwined the English Gothic Revival with colonial ambition. The Canterbury Association, led by Edward Gibbon Wakefield and backed by figures such as the Archbishop of Canterbury and John Robert Godley, sought to recreate the orderly ecclesiastical structure of England in the farthest corner of the empire. Art, in this context, was not separate from theology—it was an extension of it.

This vision gave rise to Christchurch’s most iconic early buildings: the Church of St Michael and All Angels (1851), and later the more ambitious ChristChurch Cathedral, begun in 1864. Their pointed arches, lancet windows, buttresses, and spires were deliberate assertions of continuity—expressions of Anglican piety rooted in medieval aesthetics but transposed onto a radically different geography. The art was not only in the architecture’s form but in its ideological function. Gothic Revival here signaled not nostalgia, but a declaration of civilizational permanence.

Imported craftsmen and itinerant builders shaped this vision using native materials: basalt, timber, and limestone from Oamaru. Yet even in these local substitutions, a kind of fusion began to emerge. The early artistic expressions of Christchurch were inherently hybrid—not by design but by necessity. Building churches in a seismic land required reinterpretation. The style may have been English, but the execution was increasingly Southern.

Bishop Selwyn and the sacred geometry of Gothic Revival

One cannot separate the early art and architecture of Christchurch from the formidable influence of Bishop George Augustus Selwyn, New Zealand’s first Anglican bishop. A tireless traveler and master strategist, Selwyn was deeply committed to the idea that religious architecture should educate and uplift. He wasn’t an artist in the traditional sense, but he was a visual thinker, a man who believed in the moral power of structure, proportion, and design.

Selwyn imported not just church models but a theory of space. His preference for Gothic architecture was deeply theological: he believed its upward lines and illuminated interiors reflected divine order. Working closely with architects like Benjamin Mountfort and Frederick Thatcher, Selwyn helped spread the Gothic template throughout Canterbury. Mountfort, in particular, would become a defining artistic force in Christchurch’s early decades, translating Selwyn’s ideals into stone.

Mountfort’s first major ecclesiastical commission, the Canterbury Provincial Council Chambers (1858), fused Gothic detail with political ambition. Though technically a government building, its tracery windows and vaulted timber ceilings echoed ecclesiastical space. This blurring of civic and sacred style was not incidental. In Christchurch’s early years, artistic identity was inseparable from Anglican design and symbolism. Even administrative buildings bore the moral weight of church aesthetics.

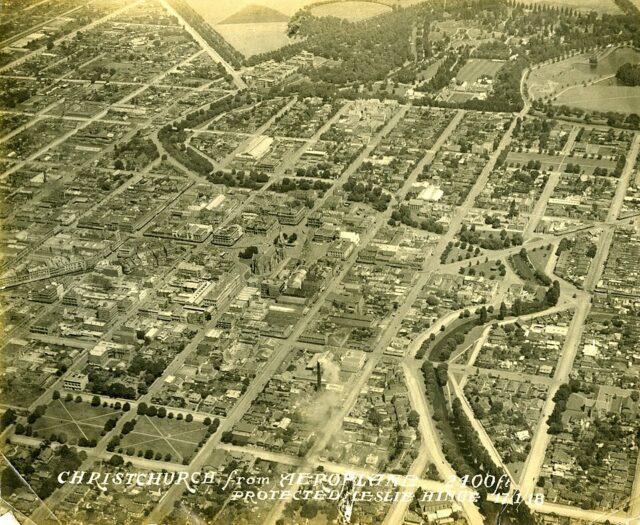

What emerged in these years was a city consciously styled as a “New Jerusalem,” complete with axial street plans, village greens, and a cathedral at its heart. Unlike in other colonial cities where art was largely decorative or entrepreneurial, in Christchurch it was embedded from the beginning in a vision of religious idealism. The city itself was a designed object—a work of ecclesiastical art.

Early stone masons, stained glass, and symbolism in the pioneer years

Though few early artists in Christchurch were professionals in the European sense, the role of artisans—particularly stonemasons and stained-glass makers—was vital. These craftsmen brought with them techniques honed in Yorkshire, Kent, and Devon, adapting their skills to local materials and seismic conditions.

One of the most remarkable early contributions was the stained glass in ChristChurch Cathedral. Installed over several decades, much of it was designed in England but some was produced locally by workshops that formed in response to the demand for ecclesiastical decoration. These windows often depicted the life of Christ, the apostles, and New Testament parables—but with subtle references to the New Zealand context: native flora at the margins, colonial-era attire in depictions of saints, and even southern stars in night-sky backgrounds. This was sacred art slowly absorbing the landscape it occupied.

Equally vital were the stone carvers who gave the cathedral and churches their expressive details—gargoyles, foliated capitals, and traceried stonework. Their work was rarely signed or documented, but it framed the spiritual and aesthetic language of early Christchurch. The masons’ labor wasn’t just structural—it was iconographic. In a city without a native visual tradition of its own, these artisans gave form to the sacred stories that defined the moral compass of the settlement.

Even secular buildings, such as early banks and law courts, adopted similar detailing, blending civic authority with religious symbolism. It was a time when architecture, ornament, and ideology walked hand in hand. The very stones of Christchurch preached a visual gospel.

Christchurch’s founding generation saw art not as decoration, but as destiny—etched in stained glass, carved in limestone, and rising in spires toward a foreign heaven. Their ecclesiastical vision would later face challenges from modernism, disaster, and doubt, but in these first decades, the city stood as a total work of Anglican art.

The Rise of a Cultural Capital

A city is not born a cultural capital—it earns that identity through repetition, ritual, and ambition. In the case of Christchurch, the ambition was present from the outset. Though its founding purpose was religious, its trajectory was always civic. By the late 19th century, Christchurch was no longer just a cathedral town or colonial outpost—it had become the South Island’s visual and intellectual hub, where institutions, exhibitions, and education began to shape a distinct artistic culture.

Christchurch as “The Canterbury Settlement” and its artistic ambitions

When the first four ships carrying Canterbury settlers arrived in Lyttelton Harbour in 1850, they carried more than supplies and furniture. They brought framed engravings, sketchbooks, musical instruments, and even the occasional oil painting. These were not just personal luxuries; they were statements of intention. The Canterbury Settlement was designed to be a society of refinement—a transplanted slice of English middle-class life—and art was part of that civilizing project.

Christchurch was deliberately set apart from rougher, gold-driven towns like Dunedin or Greymouth. Its emphasis was not on mining wealth but on moral and cultural elevation. Early settlers founded libraries, music societies, amateur theater troupes, and drawing clubs within a decade of arrival. Even before there was a formal art gallery, there were lectures on aesthetics and philosophy, held in churches and public halls.

The tone was set by figures like John Robert Godley, often regarded as the “Founder of Canterbury,” who emphasized that the arts were integral to building a mature, virtuous society. His influence lingered, even after his departure, in the cultural institutions that developed: schools that emphasized drawing and classical education, newspapers that reviewed art exhibitions, and a city plan that reserved space for public buildings, gardens, and cultural gatherings.

The Christchurch Botanic Gardens, begun in 1863, were one of the first public spaces where art and horticulture were allowed to meet. Over time, sculpture was introduced into the gardens, creating a blend of cultivated nature and visual ornamentation that reinforced the city’s refined image. The very idea of a “garden city,” long before the term became fashionable in urban planning, was already embedded in Christchurch’s cultural psyche.

The influence of the Canterbury Association on civic design

The Canterbury Association’s power faded relatively quickly after the 1850s, but its design legacy persisted. By shaping the city’s early structures, street grid, and educational institutions, the Association had laid down an aesthetic and organizational DNA that continued to express itself in visual culture.

Among the most important architectural legacies were the civic buildings that emerged in the following decades: the Canterbury Museum (founded in 1867), the Provincial Council Buildings (1858–65), and the early university buildings around the central city. These were constructed in styles that mirrored and extended the ecclesiastical Gothic of the cathedral—ribbed vaults, pointed arches, corbelled stone. But they also signaled a shift: the church had seeded the culture, but the city was now taking ownership of it.

Benjamin Mountfort remained central during this phase. As Provincial Architect, he helped design not only churches but also libraries, schools, and government buildings. His use of Gothic was not static—he adapted it for civic space, creating structures that were ornate but functional, moral but modern. His buildings elevated Christchurch’s visual profile while reinforcing the idea that culture was inseparable from public life.

This melding of civic and artistic ambition culminated in the 1870s and 1880s, when the city saw an expansion of arts societies, music halls, and literary salons. Crucially, these developments were not merely elite pursuits. Evening art classes, public lectures, and open exhibitions drew in the broader public, encouraging a kind of middle-class cultural fluency that would define Christchurch’s identity well into the 20th century.

Establishing cultural hierarchy: art, architecture, and British values

As the city matured, a hierarchy of culture began to take shape. British standards remained the benchmark. Paintings that followed the conventions of the Royal Academy were favored in exhibitions; buildings that adhered to English norms were awarded commissions; and criticism in newspapers often judged works not by their originality but by how closely they matched British ideals of taste, proportion, and discipline.

This hierarchy was both a limitation and a structure. On one hand, it delayed the emergence of a distinctly local visual idiom. Artists were encouraged to paint the Southern Alps as though they were the Lake District, to see the Waimakariri plains through a Turner-esque haze. On the other hand, it gave young artists a rigorous technical foundation. Training in perspective, anatomy, and composition remained strong well into the early 20th century, thanks in part to imported textbooks and traveling instructors.

Yet there were signs of friction. The more observant painters, particularly those who engaged with botanical subjects or studied the particular qualities of New Zealand light, began to diverge from their British models. The landscape refused to conform. Its harsh contrasts, oversized skies, and un-English vegetation demanded new approaches to scale, line, and color. This quiet resistance—visual rather than verbal—would slowly lead to a regional style.

A vivid example came in the form of Margaret Stoddart, whose floral watercolors and plein-air studies began to show a different sensibility: still technically refined but freer, more attuned to light and sensation than to English precedent. She was trained within the very system that prized Englishness, yet her work, and that of others like Alfred Walsh and John Gibb, marked the beginning of a visual dialect distinct from its colonial roots.

By the end of the 19th century, Christchurch had moved from sacred blueprint to civic culture. It had theatres, museums, gardens, a university, and an expanding class of educated citizens who not only consumed art but began to produce it with authority. The city’s cultural capital was no longer aspirational—it had become real, if still tempered by the accents of its imported origins.

The Canterbury Society of Arts and Early Exhibition Culture

For Christchurch, the late 19th century was a period of mounting confidence—and mounting expectations. The city had the institutions, the architecture, and the educated public. What it still lacked was an enduring platform for the visual arts: a place where paintings, prints, and sculpture could be displayed, discussed, and judged. The founding of the Canterbury Society of Arts in 1880 filled that void, establishing not just an exhibition space, but a cultural engine that would drive the city’s artistic development well into the next century.

Founding ideals and the struggle for a public art life

The Canterbury Society of Arts (CSA) was born of aspiration and anxiety in equal measure. A group of artists, patrons, and civic leaders—many of them tied to the Anglican establishment or the city’s academic institutions—gathered to form an organization that would elevate the status of art in Christchurch. They sought to regularize exhibitions, create a forum for discussion, and provide both support and discipline to local artists.

The CSA’s founding coincided with the construction of a dedicated gallery space on Durham Street, completed in 1890. Designed by Benjamin Mountfort and Richard Harman in a restrained Gothic Revival style, the building itself embodied the Society’s values: seriousness, permanence, and a kind of measured aesthetic orthodoxy. It was not a bohemian experiment. The Society sought to raise standards, not challenge them.

This orientation presented immediate tensions. While the CSA was essential for giving local artists a venue in which to show their work, it also enforced a clear hierarchy of taste. Exhibitions were juried, and preference was often given to technically proficient landscapes, portraits, and moral genre scenes—typically in oil or watercolor, and almost always executed in a style palatable to Victorian sensibilities. Decorative or abstract work was discouraged. Sculpture was underrepresented. Photography was barely acknowledged.

The Society’s exhibitions, held annually, quickly became social events. They were reviewed in the newspapers, attended by city officials, and closely scrutinized by the public. Success at a CSA show could secure commissions or teaching positions; failure could end a local career. The stakes were real, and the standard was unapologetically conservative.

Yet despite—or perhaps because of—its conservatism, the CSA provided Christchurch with its first sustained public art life. It created continuity, visibility, and a shared critical vocabulary. And it gradually widened its scope, allowing newer forms and bolder approaches to filter in as the century turned.

What was shown, what was censored: aesthetic battles in the colonial salons

The CSA’s exhibitions served as a mirror, not just of the city’s taste, but of its anxieties. Art in Christchurch during the late 19th and early 20th centuries was often trapped between the desire to innovate and the need to conform. The results were sometimes bland, sometimes brilliant, and occasionally controversial.

Among the recurring flashpoints was the tension between landscape and narrative painting. Landscapes were safe: they could be admired for technique, praised for patriotism, and purchased for parlors. But narrative paintings—especially those with allegorical or emotional content—risked moral scrutiny. Religious themes were accepted, even encouraged, provided they were handled reverently. But sensuality, social critique, or psychological intensity could provoke backlash.

One example came with the early exhibitions of Petrus Van der Velden, a Dutch-born painter whose moody, almost spiritual renderings of the Otira Gorge were seen by some as too dark, too foreign, too unorthodox. His brushwork was loose, his tonal palette severe, and his emotional register too raw for many of the CSA’s jurors. Though he would later be recognized as one of the South Island’s great painters, Van der Velden struggled at first to gain traction in Christchurch’s formal art circles.

Women artists also faced subtle forms of censorship—not overt exclusion, but narrowed expectations. Floral still lifes, portraits, and domestic interiors were encouraged; large-scale compositions or ambitious allegories were not. Margaret Stoddart, for example, achieved considerable success with her watercolor botanicals and Impressionist landscapes, but she worked within a tightly bounded space of thematic acceptability. The CSA embraced her, but on terms that matched its cultural prescriptions.

At the margins, however, something more adventurous was forming. A few artists began to experiment with looser brushwork, flattened perspective, and more overtly emotional subjects. These hints of modernism—still embryonic—did not yet constitute a movement, but they signaled a shift. The colonial salon was no longer immune to the world beyond England.

From parlor to gallery: how early exhibitions shaped artistic reputations

In the domestic world of Christchurch art, the CSA exhibition was the crucible. Before the rise of commercial galleries, public institutions, or national touring shows, there was the annual Society show—and its walls determined who would be remembered and who would vanish.

The exhibition halls on Durham Street were laid out with deliberate formality. Works were hung salon-style: frame to frame, floor to ceiling, arranged by genre, size, or perceived quality. The experience could be overwhelming—a cacophony of style and subject—but it also created a visual drama that lent weight to even modest works. A good placement could launch a career.

The selection committee, made up of artists and patrons, operated with both aesthetic judgment and social instinct. They knew which artists could draw crowds, which donors needed placation, which styles might cause scandal. It was an ecosystem of soft power and quiet competition.

For artists like Alfred Walsh, known for his studies of Canterbury’s rolling hills and cloud-wrapped peaks, the CSA offered a kind of public validation. His inclusion in multiple exhibitions helped cement his reputation as a regional master of landscape, even though his work rarely departed from established conventions.

Other artists used the CSA as a stepping stone to wider recognition. Some would go on to exhibit in Wellington, Dunedin, or even London. Others would become teachers or mentors, shaping the next generation of painters at the Ilam School of Fine Arts or in local secondary schools.

By the early 20th century, the CSA had become more than an art society—it was a gatekeeper, a training ground, and a social network. It gave Christchurch artists a stage, an audience, and a set of stakes. And in doing so, it turned a provincial scene into a living, breathing art world.

The Canterbury Society of Arts laid the groundwork for Christchurch’s visual culture: not merely by showing art, but by shaping how it was seen, judged, and remembered. Its influence would endure long after its peak, echoing through institutions, reputations, and expectations—some liberating, some limiting—but always formative.

The Gothic and the Garden City: Architecture as Art

Christchurch’s claim to artistic distinctiveness has always been inseparable from its architecture. Long before the city had internationally recognized painters or a robust gallery scene, it had something more public and immediate: a built environment steeped in aesthetic intention. The visual culture of Christchurch was first and most enduringly expressed not on canvas but in stone, wood, and stained glass. And the style that dominated its skyline and streetscape for generations was Gothic—not the brooding Gothic of European cathedrals, but an adapted, optimistic, colonial Gothic that shaped the identity of a so-called “Garden City.”

Benjamin Mountfort and the shaping of a visual identity

To understand Christchurch as an artistic project, one must begin with Benjamin Woolfield Mountfort. Arriving in Canterbury in 1850 with architectural training and a passion for the Gothic Revival, Mountfort would go on to become the province’s most influential designer. His contribution wasn’t limited to individual buildings—it was visual philosophy in stone.

Unlike the classicism favored in many colonial capitals, Mountfort’s Gothic was theological and local. He believed, like his ecclesiastical patrons, that Gothic forms were spiritually superior: vertical lines that lifted the soul, pointed arches that framed divine mystery, rib vaults that evoked sacred geometry. But Mountfort also understood pragmatism. His buildings were designed for local conditions—frequent earthquakes, harsh light, changing weather—and they often used timber rather than stone, particularly in his early career.

Among his major works were:

- The Canterbury Provincial Council Buildings (1858–65): a political complex rendered in ecclesiastical language, complete with carved wood ceilings, traceried windows, and cloister-like passages.

- St Mary’s Church, Addington (1867): a modest wooden chapel demonstrating Mountfort’s early facility with Gothic design on a small scale.

- ChristChurch Cathedral (from 1864 onward): his most iconic project, completed with assistance from other architects, and a symbol of Anglican permanence in the city’s center.

Mountfort’s buildings created more than functional space—they created atmosphere. The interiors were often dim, vaulted, and intricately detailed, turning civic engagement or religious ritual into aesthetic experience. Visitors to the Provincial Council Chamber didn’t just enter a meeting room; they entered a space where power was draped in beauty, and law was cloaked in medieval symbolism.

Christchurch’s skyline—punctuated by spires, gables, and pointed arches—became a kind of Gothic manifesto. The city’s visual identity was rooted not in abstraction or naturalism, but in built symbolism: a physical theology that shaped the way residents saw their own institutions.

The Arts and Crafts influence in ecclesiastical and civic buildings

By the late 19th century, Mountfort’s pure Gothic was evolving. The influence of the Arts and Crafts movement—originating in England with William Morris and his circle—began to seep into Christchurch’s architectural vocabulary. This wasn’t a rejection of Gothic but a softening of it: a move toward local materials, hand craftsmanship, and vernacular forms.

Christchurch was unusually receptive to these ideas. Its size allowed for experimentation, its population prized aesthetic dignity, and its Anglican base valued moral symbolism in design. Architects such as Samuel Hurst Seager and Cecil Wood began to blend Gothic verticality with Arts and Crafts intimacy: low eaves, exposed beams, half-timbering, patterned brickwork, and a renewed emphasis on the building as a “total work of art.”

This period produced churches, schools, and civic structures that combined the solemnity of Gothic with the warmth of the vernacular. Seager’s Simpkin House (1906) and Wood’s later work on Christ’s College buildings offered domestic calm wrapped in medieval motifs. Interior spaces featured carved wood, leaded windows, and carefully crafted furniture—often bespoke for the building.

This movement also saw a rise in collaboration between architects and artisans. Stained-glass makers, stone carvers, furniture designers, and metalworkers contributed to unified interiors. A church was no longer just a place of worship—it was a curated aesthetic environment. Even domestic homes in wealthy suburbs like Fendalton began to show the influence: fireplaces with tiles painted by local artists, built-in cabinetry with inlaid motifs, and windows etched with botanical designs.

Arts and Crafts didn’t replace Gothic in Christchurch—it modified and deepened it. The garden city now had houses that echoed the ecclesiastical grandeur of its center, scaled down to the intimacy of private life. Aesthetic coherence spread from cathedral to cottage.

How stone, wood, and glass created a visual theology

The artistry of Christchurch’s built environment extended far beyond the architects. It lived in the hands of stonemasons, glaziers, and carpenters—many of them trained in England but adapting their techniques to a new land. Their contribution was neither decorative nor ancillary; it was foundational.

The city’s churches, in particular, became showcases for these crafts. At St Michael and All Angels, delicate timber trusses soared above pews, supported by hand-carved bosses and corbels. At St Luke’s in the City, the stonework blended local basalt with creamy Oamaru limestone, creating soft contrasts of texture and tone. These choices were not just structural—they were aesthetic decisions that shaped the spiritual character of the buildings.

Stained glass also played a major role. Imported panels from English studios like Clayton and Bell were gradually supplemented by local work, as New Zealand-based artisans took on commissions. These windows—rich in biblical narrative, Victorian moralism, and botanical detail—acted as both storytelling devices and light filters, casting interior spaces in colored glow. A late afternoon service in a Christchurch church was, quite literally, bathed in visual art.

Even secular buildings followed suit. Banks and libraries featured carved lintels, vaulted ceilings, and symbolic motifs. The old Chief Post Office on Cathedral Square (completed 1879) used polychromatic brickwork and sculptural detailing to suggest solidity, authority, and civic pride.

The result was a city where art was not confined to galleries. It was embedded in daily experience:

- The way sunlight refracted through a nave window during evensong.

- The tactile pleasure of carved wood beneath a handrail.

- The quiet grandeur of a council chamber that felt like a chapel.

This was visual theology: a belief that beauty could dignify public life, that craftsmanship could uplift civic discourse, and that architecture could articulate a worldview without needing to explain itself in words.

Christchurch’s early architectural vision was more than aesthetic preference—it was a cultural proposition. The city’s Gothic and Arts and Crafts buildings did not merely house its institutions; they shaped its sense of meaning, value, and self-respect. Even as earthquakes would later bring much of this fabric down, the memory of these forms—elevated, hand-wrought, moral—would linger in the city’s bones.

The Natural Sublime: Landscape Painting in the South Island

The South Island is a land of extremes: alpine ridgelines cutting into violent skies, braided rivers sweeping across gravel plains, and a light that shifts with unnerving rapidity. For Christchurch painters in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, this landscape was not merely background—it was a subject, a challenge, and a calling. If the city’s architectural Gothic expressed its spiritual inheritance, landscape painting became the visual language through which artists wrestled with place, belonging, and the sheer physicality of New Zealand’s South.

John Gibb, Petrus Van der Velden, and the alpine imagination

John Gibb is often cited as the South Island’s first major landscape painter, and for good reason. Trained in Scotland and arriving in Christchurch in the 1870s, Gibb brought with him a set of formal skills and tonal sensibilities shaped by European Romanticism. But what he encountered in New Zealand was both more violent and more vast than anything his training had prepared him for. His early works show the tension: careful compositions, precise brushwork, and a muted palette struggling to contain the raw scale of the Southern Alps.

Gibb’s breakthrough came not in mastering the land, but in letting it dominate the canvas. Works like The Mouth of the Waiau River and Shag Rock, Sumner depict humans and buildings as minor details—almost apologies—within sweeping geological drama. He was not yet radical in style, but he was beginning to bend the genre toward a distinct regional sensibility: a landscape not tamed, but barely visited.

Petrus Van der Velden arrived a few decades later and brought something else entirely. Born in Rotterdam and trained in the traditions of Dutch Romanticism, Van der Velden settled in Christchurch in the 1890s and quickly found in the Otira Gorge a subject worthy of spiritual obsession. His Otira Series—dark, brooding oil paintings of storm clouds, gnarled rocks, and water surging through narrow gorges—remain among the most emotionally charged landscapes produced in New Zealand art.

Van der Velden painted not to describe but to endure. His brushwork was aggressive, his palette brutal: greys, blacks, and umber dominating the canvas in dense, almost sculptural strokes. Where Gibb offered perspective, Van der Velden offered confrontation. These were not picturesque views—they were visual theologies of isolation, sublime terror, and human insignificance.

Christchurch audiences were initially ambivalent. His work was frequently criticized in the local press as too gloomy, too European, too unsettling. But over time, Van der Velden came to influence a younger generation of painters who saw in his approach a model for how the New Zealand landscape might be painted on its own terms—not as a variation on Europe, but as something fundamentally more elemental.

The moral landscape: nationalism through scenery

The emergence of landscape painting in Christchurch was not simply an aesthetic event—it was also a cultural and, at times, political one. In the absence of ancient buildings or heroic national myths, landscape became the primary canvas upon which ideas of New Zealand identity were projected.

The Southern Alps, in particular, became more than mountains—they were symbolic frontiers. They embodied endurance, purity, isolation, and promise. Painting them was an act of possession, but also of reverence. This was not the wildness of romantic fantasy, but a terrain that demanded moral resilience. The very difficulty of accessing these places—sometimes reached only by foot or horseback—gave weight to their depiction.

Three recurring tropes defined this moral landscape:

- Scale and solitude: Humans were depicted as tiny or absent altogether, emphasizing the sublime rather than the pastoral.

- Climatic drama: Weather was central—rolling clouds, snowstorms, and floods were treated as moral actors in their own right.

- Verticality and geology: Mountains were not background but the subject, rendered in obsessive detail, suggesting not grandeur but gravitas.

This moral seriousness was reinforced by how and where these works were shown. At the Canterbury Society of Arts, alpine scenes were often the centerpiece of exhibitions. Reviews in the Lyttelton Times or The Press judged them not only by artistic merit but by how faithfully they rendered the “spirit” of the South Island. A good landscape wasn’t just beautiful—it was a form of patriotic labor.

Yet beneath this patriotic impulse ran a current of unease. The very sublimity of the landscape—its refusal to be picturesque, its resistance to sentimentalization—posed a challenge to colonial confidence. Painters who looked too closely, too honestly, sometimes produced images that bordered on despair. The land, it turned out, did not always love its settlers back.

Watercolour and the language of place

While Gibb and Van der Velden worked mostly in oil, another tradition was flourishing in parallel: the use of watercolour to capture the shifting character of New Zealand’s skies, rivers, and flora. This medium—portable, quick-drying, and delicate—proved especially well-suited to Christchurch’s changing light and open vistas.

Artists such as Margaret Stoddart made decisive contributions here, developing a plein-air approach that favored immediacy over monumentality. Her watercolours of the Heathcote Valley, Lyttelton Harbour, and native gardens are not grand in scale but are rich in atmosphere and chromatic sensitivity. Trained at the Canterbury College School of Art and later in Europe, Stoddart returned with Impressionist techniques but applied them to a local palette: flax, raupō, kowhai, mist.

Watercolour encouraged a different way of seeing. Instead of framing the landscape as sublime and overpowering, it allowed for a gentler intimacy—a sense of fleeting moment rather than eternal force. This shift was especially visible in botanical studies, which became an important genre in Christchurch art, blurring the line between scientific observation and aesthetic pleasure.

In this space between science and art, Christchurch painters found a language for place. The very act of identifying, recording, and rendering native flora became a form of cultural rootedness. These works circulated not just in galleries but in books, scientific journals, and school classrooms, further embedding a regional visual sensibility into public life.

By the early 20th century, Christchurch artists had forged a landscape tradition that was neither a copy of Europe nor a rejection of it. It was something slower and harder won: a local grammar of light, weather, scale, and solitude. Whether painted with the fury of Van der Velden, the care of Gibb, or the delicacy of Stoddart, the land had become a subject that refused to be simplified—and in that refusal, it became art.

Botany, Light, and Localism: Christchurch’s Early Painters

The first painters to emerge from Christchurch’s own soil—trained locally, working within its rhythms, and painting its specific features—were not defined by grand theory or manifestos. Instead, they were marked by precision, restraint, and intimacy. Where European-trained artists brought heroic or romanticized views of New Zealand’s landscape, Christchurch’s early painters turned their gaze downward and closer: to gardens, plains, shorelines, and interiors suffused with the city’s pale, bracing light. Their work revealed a different kind of ambition—less theatrical, but no less serious—anchored in observation, patience, and local truth.

Margaret Stoddart and the scientific eye

Margaret Stoddart remains the most accomplished of Christchurch’s early native painters. Born in Diamond Harbour in 1865, trained at the Canterbury College School of Art, and later influenced by time in England and Europe, she returned to Christchurch with a sensibility sharpened by Impressionism but firmly grounded in botanical realism.

Her early works—floral studies and coastal scenes rendered in watercolor—reflected not only artistic skill but scientific clarity. In the 19th century, botany and painting were deeply entwined, especially for women artists who often studied plants in both aesthetic and empirical terms. Stoddart’s watercolours of New Zealand native species are not merely pretty—they are accurate, studied, and quietly expressive.

In works such as Roses in a Blue Vase or A Garden in Godley House, she used translucent washes and light-filled compositions to dissolve the border between interior and exterior space. The gardens of Christchurch—shaped by European ideals, but filled with local light and flora—became her laboratory. Every flower she painted held both botanical specificity and tonal complexity. Her palette was pale but never weak, and her brushwork grew looser as her career progressed, revealing her sensitivity to changing light and air.

Stoddart’s influence stretched beyond her canvases. She taught at the Canterbury College School of Art and exhibited regularly with the Canterbury Society of Arts. Her work was included in national and international exhibitions, and she helped to define a visual language that emphasized immediacy, fidelity to nature, and emotional restraint. She demonstrated that regionalism could be exacting rather than parochial—that one could paint the same garden path a hundred times and still say something new.

Alfred Walsh and the chromatic study of light

Another painter who quietly shaped Christchurch’s early artistic personality was Alfred Walsh. Though less widely known today, Walsh’s landscapes were among the most frequently exhibited and commercially successful works in Christchurch from the 1890s through the early 20th century. Trained initially as a draughtsman, he brought a rigorous clarity to his treatment of sky, water, and terrain.

Where Stoddart often looked inward to cultivated spaces, Walsh looked outward—especially toward the hill country, estuaries, and river flats surrounding Christchurch. His work was not dramatic in the mode of Van der Velden, nor was it formally experimental. But what Walsh brought to the South Island landscape was a remarkable tonal sensitivity: he was a student of light.

Paintings such as Evening on the Avon and Sunset, Lyttelton Harbour reveal a careful modulation of color temperature, from warm ochres to glacial blues. He rarely included figures; instead, his compositions emphasize atmosphere, distance, and serenity. These were not paintings of conquest or wildness but of inhabited stillness—the landscape not as frontier, but as environment.

Walsh was also a skilled watercolorist and printmaker, contributing illustrations to books and journals. His style helped solidify what would become an enduring South Island palette: cool, spare, high-key, and sensitive to transitional times of day. The quality of light in Christchurch—thin, bright, often low-angled—found in Walsh one of its most faithful interpreters.

In this quiet fidelity to place, he foreshadowed a later generation of artists who would likewise reject both heroic grandeur and sentimentalism in favor of clarity, subtlety, and formal control.

Botanical realism as a regional aesthetic

The emphasis on botanical detail and luminous naturalism in early Christchurch painting was not accidental. It reflected both the city’s physical environment and its intellectual climate. Unlike cities where industrial imagery or human drama dominated the visual field, Christchurch was a place of gardens, wetlands, and cultivated stillness. Artists responded accordingly.

Three distinctive features defined this regional aesthetic:

- An eye for species and specificity: Rather than treating “nature” as a generalized motif, painters depicted particular plants—kowhai, harakeke, lilies, delphiniums—with studied accuracy.

- A preference for watercolor and pastel: These media allowed for fine detail, tonal control, and a softness well-suited to Christchurch’s climate and light.

- An interior-exterior continuum: Many paintings blurred the line between domestic interiors and cultivated exteriors—views through windows, sunlit verandas, garden borders seen from kitchen steps.

The result was a quiet but cumulative cultural statement. While modernists in Europe were breaking form and rejecting realism, Christchurch painters were investing in slow looking. They made the familiar visible again. They painted the Avon River not as a symbol, but as a literal curve of light and water through a flat plain. They rendered a stalk of flax not as ornament, but as a fact.

Even their restraint became a kind of signature. Christchurch’s early painters didn’t push for revolution. Instead, they insisted that fidelity, patience, and attentiveness were artistic values in their own right. They helped cultivate not only a style, but a sensibility—one grounded in seasonal change, close observation, and the unassuming beauty of the ordinary.

This early phase of Christchurch painting, rooted in botany, light, and localism, formed the bedrock upon which later movements would build. Even as modernism, abstraction, and conceptualism arrived, the values of clarity, precision, and grounded observation would echo through generations of South Island artists. The seeds planted in garden paths and river reflections proved surprisingly durable.

Modernism Reaches the South

The arrival of modernism in Christchurch was less a violent rupture than a slow, uneven awakening. For decades, the city’s visual culture had been shaped by a steady discipline: careful observation, regional fidelity, and an implicit belief in representation. But by the 1930s and 1940s, cracks had begun to form in that consensus. New styles, imported through books, exhibitions, and émigré teachers, began to stir discontent with the old modes. And from that discontent, a new generation of artists emerged—ambitious, experimental, and determined to remake the visual language of the South.

The arrival of abstraction and the post-war turn

New Zealand’s isolation had long shielded it from the more radical developments of the early 20th-century art world. While Cubism, Expressionism, and Surrealism were reshaping Europe’s artistic map, Christchurch remained largely untouched, clinging to Edwardian and late Impressionist models well into the 1930s. But change was coming, and it arrived through several converging channels.

First came books and reproductions. Publications on Cézanne, Matisse, and Picasso began to circulate in university libraries and artist studios. Magazines like Art in New Zealand introduced readers to international trends, albeit filtered through cautious editorial framing. These secondhand transmissions planted the seed of possibility—especially for younger artists who found the quiet naturalism of their elders insufficient.

Then came the influence of teachers. Perhaps the most catalytic figure was Rudi Gopas, a Lithuanian émigré who arrived in Christchurch in the 1950s and taught at the Ilam School of Fine Arts. Gopas brought with him not only personal experience of European modernism, but a confrontational teaching style that challenged his students to reject the provincial and embrace the psychological. Under his guidance, abstraction and expressionism were not curiosities—they were imperatives.

The shift was slow, but it gathered force. In painting, artists began to move away from clear depiction and toward gestural form. Landscape remained a touchstone, but it was increasingly fragmented, internalized, even symbolic. Color fields replaced perspective. Lines grew angular, distressed. Texture became as important as subject.

For Christchurch, with its traditions of technical rigor and observational detail, this was a major recalibration. Modernism was not simply a matter of adopting new styles—it required a dismantling of inherited hierarchies of taste, training, and subject matter. In some quarters, the resistance was fierce. Conservative reviewers lamented the “deterioration of standards.” Art societies hesitated to exhibit work that was too bold or obscure. But the change was irreversible. The city’s visual culture had begun to turn.

Colin McCahon’s early years in Christchurch

No figure more clearly embodies this transition than Colin McCahon. Although most closely associated with Auckland, McCahon’s formative years were spent in the South Island, and his early career unfolded in the very institutions shaped by the old guard. He studied briefly at Dunedin’s art school, but it was his exhibitions in Christchurch—especially those at the Canterbury Society of Arts—that first brought him public recognition and criticism.

In the 1940s and early 1950s, McCahon’s work startled Christchurch viewers. His paintings were deeply religious, but rendered in a stark, modernist idiom: blocky forms, minimal color, and large areas of bare canvas. Works like The Angel of the Annunciation (1947) and Takaka: Night and Day (1948) bore little resemblance to the polite landscapes or botanical studies that had defined local taste.

McCahon’s engagement with landscape was particularly radical. He didn’t paint places; he painted meanings. The hills of North Otago and Nelson became formal scaffolds for theological inquiry, existential dread, and moral search. In doing so, he extended the Van der Velden tradition—but where Van der Velden had painted sublime nature, McCahon painted moral terrain.

His exhibitions in Christchurch were often polarizing. Some saw genius; others saw fraud. Letters to editors denounced the “ugliness” of his style. Yet McCahon persisted, and in doing so, he redefined what painting in New Zealand could be. His early confrontations in Christchurch were part of the city’s larger reckoning with modernism—a moment when taste, identity, and meaning were all up for negotiation.

What made McCahon especially influential was not just his work, but the conversations it provoked. His presence forced Christchurch to articulate what it valued in art—and, more crucially, why.

Rejection and recognition: local responses to international trends

Not all Christchurch artists embraced modernism, and many who did found themselves caught between ambition and provincial skepticism. The city, after all, had spent decades cultivating a culture of decorum and refinement. Bold experiments were not always welcome. For every Gopas or McCahon, there were others who found themselves sidelined or misunderstood.

One artist who experienced this tension was Doris Lusk. Though trained in the same circles as McCahon and part of the so-called “Group” (an informal collective of modern-minded artists who exhibited independently from the CSA), Lusk’s work remained grounded in structure and order. Her paintings of dams, quarries, and industrial landscapes were modern in tone but cautious in form—quietly analytical rather than expressionist. In Christchurch, where Lusk also taught at Ilam, her careful modernism provided a kind of bridge between the old and the new.

The Group itself, founded in 1927 and active through the mid-20th century, became an important counter-institution. Refusing the constraints of the CSA, it offered a more flexible, self-organized platform for artists working in modern idioms. Members included Toss Woollaston, Olivia Spencer Bower, Evelyn Page, and later, Philip Trusttum—each contributing to a slow but steady erosion of Victorian visual norms.

Still, the push for modernism was rarely easy. Public funding remained conservative. Commercial galleries were few and risk-averse. The Christchurch Art Gallery, still decades away from its modern incarnation, operated under the weight of donor expectations and civic modesty. Breakthroughs came gradually, and recognition often lagged behind innovation.

Yet these tensions also forged resilience. Artists who stayed in Christchurch—who chose to work outside of the Auckland-Wellington axis—did so with clarity of purpose. They weren’t outsiders so much as regionalists in the best sense: aware of international movements but rooted in the distinct light, scale, and cultural quietude of the South.

Modernism came to Christchurch not as a wave but as a tide: slow, insistent, and reshaping everything in its path. It brought with it confrontation, disorientation, and renewal. And while the city never fully embraced the avant-garde, it produced artists who wrestled seriously with the demands of their time—testing the boundaries of what could be painted, and what painting could mean.

Public Art and the Post-War Civic Boom

After the Second World War, Christchurch entered a period of architectural expansion and civic self-confidence. The city grew rapidly—physically, economically, and bureaucratically. New schools, churches, libraries, and office buildings emerged across its increasingly suburban footprint. And with them came opportunities for art to leave the gallery and enter public life. Wall reliefs, stained glass, murals, and sculptures began appearing in spaces of daily use, often commissioned as part of building projects. For Christchurch, a city historically steeped in Gothic and naturalist aesthetics, this post-war public art boom signaled a shift toward modern civic expression—assertive, accessible, and increasingly abstract.

Sculpture in the square: debates over modern public works

Perhaps the most visible battleground for public art in Christchurch during the post-war decades was Cathedral Square—the symbolic and literal heart of the city. For much of the 20th century, the square had remained visually defined by the spire of ChristChurch Cathedral, the symmetry of the Chief Post Office, and the surrounding commercial buildings. But as modernism gained ground in architecture and design, sculptors and city planners began to imagine the square differently—not as a Victorian relic, but as a living, evolving space for contemporary expression.

One of the first serious debates emerged around proposals to introduce modern sculpture into this traditional civic space. Works by artists such as Ria Bancroft, whose abstracted religious forms carried both spiritual and architectural resonance, challenged the prevailing notion that public art should be figurative, commemorative, or classical. When Bancroft’s Harp of Erin was proposed for a central location, controversy followed. Was it too modern? Too abstract? Too foreign in aesthetic?

In the end, many of these early proposals were softened or sidelined, but they left a mark. Public conversation around sculpture—what it should represent, how it should relate to space, and who it was for—became more vigorous. The Christchurch City Council, along with groups like the Christchurch Civic Trust, began to take a more proactive role in commissioning and curating public works.

Eventually, permanent installations such as Neil Dawson’s Chalice (though a much later example, unveiled in 2001) would transform the square. But its artistic roots lay in these earlier decades of negotiation, when artists and officials began testing how modern form could inhabit historic space. Even when works were rejected, the city’s expectations were being reshaped—public art was no longer simply about commemoration; it was about civic identity.

Churches, schools, and mural commissions

While central city spaces remained contested, other parts of Christchurch became fertile ground for public art experimentation—especially newly built churches, schools, and suburban community centers.

The post-war building boom created an unusual situation: hundreds of new structures, often designed in modernist or post-and-beam architectural styles, were commissioned across the region. Many of these projects included integrated art elements—especially murals, relief panels, stained glass, and mosaics—designed in collaboration with architects.

Churches were especially important in this regard. No longer bound by the Gothic mandates of Mountfort’s era, architects and clergy alike began to experiment with simpler, more abstract designs, and turned to contemporary artists to enrich these spaces. The Catholic Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament, for instance, included interior works that subtly merged devotional iconography with modernist restraint. Ria Bancroft’s ecclesiastical commissions—often semi-abstract, textured, and spatially integrated—typified this new fusion of faith and form.

Schools also became canvases. Murals celebrating local history, industry, or flora appeared in assembly halls and libraries, often painted by teachers or former students trained at Ilam. These were not avant-garde statements, but they reflected a belief that art could participate in civic education. Art was no longer confined to museum walls—it was embedded in the daily visual experience of childhood, teaching students to associate creativity with public life.

Even council housing developments and suburban community centers incorporated ceramic murals or low-relief panels, often designed in stylized forms that married local narrative with modern visual vocabulary. The ethos was clear: art should be present where life happened, not merely in places of prestige.

This period also produced a number of government-funded initiatives—through the Ministry of Works or the Department of Education—that mandated art in public projects. Though modest in scope compared to European models, these policies quietly transformed the urban landscape of Christchurch, allowing art to grow alongside the city’s infrastructure.

How government patronage changed the visual texture of the city

What distinguished the post-war period from earlier eras was the scale and regularity of art’s integration into public architecture. Thanks to increased state involvement in civic planning, as well as growing public tolerance for modern aesthetics, artists found steady work not only as gallery exhibitors but as collaborators in the shaping of built space.

Three effects of this patronage model were especially significant:

- Expanded artistic roles: Artists were no longer isolated creators but participants in design teams, contributing to everything from wall finishes to lighting plans.

- Shifted materials and methods: Art had to be durable, weather-resistant, and contextually harmonious, leading to increased use of metal, concrete, ceramic, and glass.

- Broadened audience engagement: Public art became part of the ordinary visual field—encountered on the way to school, embedded in a church wall, or decorating a city park.

The Christchurch Arts Centre—a repurposing of the old University of Canterbury buildings—embodied this shift. As the university moved to Ilam in the 1970s, the Gothic Revival buildings in the city center were gradually converted into a cultural precinct, hosting studios, theaters, galleries, and artisan workshops. Public art flourished here in small but steady forms: carvings, plaques, tiled entryways, sculptural signage.

This integration of art into civic life created a new visual texture for Christchurch. The city was no longer defined only by its 19th-century spires or its picturesque gardens. Now, it included bas-reliefs in concrete, abstract murals in school corridors, and sculptural forms embedded in suburban architecture. Public art became a shared visual memory, woven into the experience of everyday life.

The post-war civic boom did not make Christchurch an artistic capital in the traditional sense. But it did something equally meaningful: it embedded art into the ordinary structure of the city. From mural-covered classrooms to quietly subversive sculptures in civic squares, Christchurch in the mid-20th century became a place where art could be lived with, not just looked at.

The University as Incubator: Ilam School of Fine Arts

In every city that sustains a serious visual culture, there is usually a single institution that serves as its wellspring—a place where talent gathers, ideas collide, and artistic norms are both taught and defied. In Christchurch, that role has long been played by the Ilam School of Fine Arts. Affiliated with the University of Canterbury since the 1950s but with origins stretching back to the late 19th century, Ilam was not merely a school. It was a crucible for ambition, a battleground for styles, and the silent architect of the city’s modern visual identity.

Russell Clark and the tradition of figurative instruction

Before the rise of radical modernism at Ilam, the school was known for its quiet discipline. Its early years emphasized technical training: drawing from life, anatomical study, principles of perspective and composition. This reflected the continued influence of British art education, but also the needs of a city where commercial art, teaching, and illustration remained viable career paths.

One of the key figures of this era was Russell Clark. A painter, sculptor, and illustrator, Clark trained at the Canterbury College School of Art (as it was then known) and later returned to teach. He brought with him not only a strong foundation in classical technique but a commitment to narrative art—a belief that visual work should communicate clearly, often through the human figure.

Clark’s illustrations, especially during and after World War II, appeared widely in books and government publications. His paintings, while less publicly prominent, showed careful draftsmanship and a restrained expressiveness. As a teacher, he was firm but generous, encouraging students to master form before venturing into abstraction or stylistic deviation.

Through his tenure in the 1940s and early ’50s, Clark helped maintain a culture of precision and accountability at Ilam. His influence was particularly evident in sculpture and figure drawing—disciplines that demanded patience and anatomical rigor. In many ways, Clark represented the last flourishing of a pedagogical model that saw the artist as a skilled craftsman in service to public communication.

His students left with solid foundations, whether they became teachers, illustrators, or, in a few cases, fine artists. But Ilam was about to change. The tension between mastery and innovation—long held in balance—was tipping toward something less certain, and more volatile.

Rudi Gopas and the modernist shift in pedagogy

The arrival of Rudi Gopas at Ilam in 1959 marked a decisive turning point in both the school’s philosophy and Christchurch’s wider art scene. Gopas, a refugee from war-torn Europe, brought with him not only personal trauma but the intellectual urgency of postwar modernism. Trained in Vilnius and influenced by German Expressionism, he was a painter of brooding intensity and psychological depth—and he expected the same of his students.

His presence on the faculty was polarizing. Where Clark had emphasized clarity and control, Gopas demanded inner vision, emotional honesty, and stylistic boldness. He challenged students to think beyond the local, beyond the decorative, beyond the merely skilled. Under his mentorship, abstraction and personal symbolism came to the fore. Gesture and texture began to rival line and proportion. The canvas became a site of existential inquiry.

Some students flourished under this provocation. Don Peebles, Philip Trusttum, and others emerged from Ilam in the 1960s with work that reflected both technical confidence and conceptual daring. Gopas pushed them to develop a distinctive voice, even if it meant alienating older institutions or public taste.

Others found his methods abrasive. He could be dismissive, even caustic, toward students who resisted his approach. Yet his effect on the school was undeniable: Ilam began to attract attention as a serious art academy—not just a regional training ground, but a place where new ideas were forged.

This shift coincided with broader changes at the University of Canterbury, which was relocating from its historic city center buildings (later repurposed as the Arts Centre) to the new Ilam campus. The move gave the art school more space, more autonomy, and a campus environment less tethered to Christchurch’s conservative civic institutions. It also placed visual art alongside academic departments, encouraging cross-pollination with philosophy, literature, and architecture.

By the late 1960s, Ilam had become the intellectual and creative heartbeat of the South Island’s visual culture. Its graduates were beginning to appear in national exhibitions, its staff were publishing in art journals, and its internal debates—over abstraction, figuration, identity, and politics—mirrored those happening in New York, London, and Sydney, albeit on a smaller, more local scale.

Ilam’s role in forming the “Christchurch School” of painters

While the term “Christchurch School” has never been formally defined, it’s often used to describe a generation of artists who emerged from Ilam in the 1960s and ’70s with a shared visual language: clean lines, cool light, structural clarity, and an often understated emotional tone. It wasn’t a manifesto-driven movement, but a convergence—a sensibility rooted in place, pedagogy, and atmosphere.

Painters like Philip Trusttum, Julia Morison, and John Drawbridge shared a commitment to formal coherence even as their styles diverged. Whether working in geometric abstraction, symbolic figuration, or textured surface play, these artists displayed a compositional discipline that reflected their Ilam training.

Several common traits defined this loose collective:

- Spatial restraint: Even in large-scale works, space was measured and deliberate, avoiding visual chaos.

- Palette control: Many Christchurch-trained artists favored cool or neutral color schemes, often reflecting the South Island’s light and mood.

- Material awareness: Texture, surface quality, and process were foregrounded, sometimes even more than subject.

Crucially, these artists were not trying to replicate international trends. They were aware of them—keenly so—but they filtered those influences through a regional lens. Their work did not scream; it resonated. It reflected Christchurch’s geography, temperament, and intellectual modesty.

By the 1980s, Ilam had become not just a training ground but a legacy-builder. Many of its alumni returned to teach, creating a self-sustaining loop of influence. The school’s archives, critique sessions, and graduate shows became part of the city’s cultural calendar, drawing curators, collectors, and critics from across the country.

The Ilam School of Fine Arts shaped Christchurch’s visual culture more deeply than any single artist or exhibition could have. It created a lineage of painters, sculptors, and designers who understood both the rigor of tradition and the necessity of challenge. In its studios, the South Island’s visual imagination was trained, tested, and transformed.

Earthquake and Aftermath: Ruin, Recovery, and Reshaping

In Christchurch, the relationship between art and architecture has always been close. But in the early 2010s, that relationship was tested—and transformed—by catastrophe. The earthquakes of 2010 and 2011, particularly the February 2011 quake that killed 185 people and leveled much of the central city, did more than shatter stone and steel. They collapsed the aesthetic fabric of Christchurch. Spires crumbled. Galleries closed. Studios flooded or vanished. For a time, it seemed the city’s visual culture might not recover. And yet, from that wreckage emerged a new kind of artistic energy: provisional, experimental, and often deeply moving. In the ruins, Christchurch began to reimagine itself—visually, structurally, and symbolically.

The 2010–2011 quakes and the destruction of heritage

The numbers are staggering: more than 1,000 buildings in the central city were demolished. Among them were irreplaceable structures—Victorian facades, heritage-listed churches, civic icons—that had defined Christchurch’s urban image for over a century. The loss of ChristChurch Cathedral’s spire was the most symbolic of these destructions: the architectural heart of the city lay in ruins, its Gothic Revival tower broken, its nave exposed to the sky.

Art galleries were not spared. The Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, a cornerstone of the city’s cultural life, was closed for years due to structural damage. Studios, workshop spaces, and framing shops across the city were destroyed or rendered inaccessible. The Arts Centre—home to numerous cultural institutions housed in historic neo-Gothic buildings—was severely damaged, undergoing a reconstruction project that would stretch across the next decade.

The scale of the loss was not just material but psychological. For a city whose identity had been so closely tied to its historic architecture and aesthetic order, the devastation was existential. Familiar skylines vanished. Landmarks that once oriented the body and the memory were gone. Artists were displaced, audiences fragmented, and institutions scattered. The visual language of Christchurch—once formal, gardened, and coherent—had been violently disrupted.

Yet amid the trauma, a question began to emerge: if the physical heritage was gone, what would take its place?

Transitional Cathedral and cardboard as symbol

Perhaps the most widely discussed answer to that question came from an unexpected source: Japanese architect Shigeru Ban. In the aftermath of the February 2011 quake, Christchurch’s Anglican leadership commissioned Ban to design a temporary replacement for the ruined cathedral. The result—commonly known as the “Cardboard Cathedral”—was completed in 2013 and quickly became an international symbol of resilience and innovation.

Constructed using cardboard tubes, polycarbonate roofing, and shipping containers, the Transitional Cathedral was a radical departure from the Gothic aesthetic it nominally replaced. It embraced impermanence. Its materials were humble. Its geometry was simple—triangular and open, more tent than temple. And yet, in its spatial serenity and ingenious structure, it possessed a quiet beauty.

Critics were divided. Some saw it as a brilliant act of adaptive design, a hopeful gesture amid despair. Others found it architecturally underwhelming or symbolically insufficient. But as an artistic statement, it was unequivocal: Christchurch would not wait for restoration to express itself. It would build with what it had, where it could, and as soon as possible.

Ban’s cathedral was not alone. Across the city, similar improvisations took hold. Artists and architects created “gap fillers”—temporary installations, murals, and performances in vacant lots where buildings had once stood. Shipping containers became cafes, shops, and exhibition spaces. Brightly painted pianos appeared on street corners. Empty facades were turned into projection screens.

One of the most memorable of these was the 185 Empty Chairs installation by artist Peter Majendie. On a vacant lot where a church had stood, Majendie placed 185 white chairs—each different, each representing a life lost in the quake. The work was both stark and tender, and it resonated deeply with residents and visitors alike. Public art had rarely felt so personal.

These gestures—transitional, improvised, emotionally charged—marked a departure from Christchurch’s prior aesthetic culture. Where once the city had prized permanence, now it embraced temporality. Where once it had sought order, it now allowed for improvisation. Art was no longer contained in buildings; it was the city itself.

How trauma created a new visual vocabulary

Out of necessity, Christchurch developed a new visual vocabulary—one born of trauma but not defined by it. Artists responded to the earthquake not with a single style or theme, but with a shared urgency. The work that emerged in the 2010s was diverse, experimental, and often intensely site-specific.

Three currents came to the fore:

- Ephemeral materiality: Many works used salvaged, fragile, or transient materials—concrete rubble, timber, textile, light. These choices weren’t just symbolic; they echoed the city’s physical state.

- Spatial experimentation: With traditional galleries closed or damaged, artists explored unconventional venues: parking lots, alleyways, roadside fences, ruined buildings.

- Participatory form: Much of the new work invited public interaction, from communal murals to performances in empty lots. The audience became a co-creator.

The organization Gap Filler, founded in 2011, became a leader in this movement. Initially conceived as a response to the destruction of cultural space, it coordinated hundreds of pop-up projects across the city—live music, interactive sculpture, community painting days, mobile dance floors. Its ethos was anti-monumental: responsive, localized, and community-driven. Though some projects were fleeting, they left behind a profound shift in how art could be made and where it could belong.

Equally important was the psychological register of this work. Post-quake art in Christchurch rarely offered answers. It recorded grief, invited remembrance, made space for unease. There were few heroic narratives. Instead, artists captured absence, uncertainty, and tentative hope. This emotional honesty gave the city’s cultural recovery a depth and credibility that more polished efforts might have lacked.

Gradually, institutions returned. The Christchurch Art Gallery reopened in 2015 with the exhibition Unseen: the changing city, a powerful meditation on loss and transformation. The Arts Centre began a slow but meticulous restoration, blending 19th-century stonework with contemporary seismic reinforcement. And new buildings—including the Te Pae convention center and the Turanga central library—incorporated public art commissions as part of their design.

Yet even as the city rebuilt, the ethos of the transitional years persisted. Art in Christchurch no longer assumed permanence. It responded, it adapted, it moved. The earthquakes had destroyed more than architecture—they had unsettled assumptions. And in that uncertainty, something new took root.

The earthquakes did not simply wreck Christchurch’s art world; they redefined it. In the aftermath, artists filled the void not with sentimentality, but with invention. The visual identity of the city was no longer tied to heritage buildings or oil paintings on walls. It was something more fluid, more collective, and, paradoxically, more alive.

Contemporary Currents: Galleries, Artists, and Institutions

The Christchurch art world today stands at a curious intersection: shaped by trauma, forged in improvisation, and now edging back toward permanence. The decade following the earthquakes saw not only physical reconstruction but a recalibration of aesthetic priorities. New institutions opened; old ones reinvented themselves. Artists who had once worked in ruins or pop-ups began exhibiting again in formal spaces—but with a sharper sense of purpose and a deeper understanding of their environment. The art of contemporary Christchurch no longer presents a single style or school. Instead, it offers a polyphony of voices: formalist and conceptual, local and global, personal and civic.

Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū and its evolving mission

The reopening of the Christchurch Art Gallery in 2015 marked more than the return of a physical space. It was a restoration of confidence—and a redefinition of public art’s role in the life of the city. During its closure, the gallery had not been silent. It mounted guerrilla exhibitions in shipping containers, suburban houses, and digital platforms. Its staff commissioned billboards and projections across the city, keeping art visible when walls had crumbled. That spirit—nimble, outward-facing, experimental—was carried into the gallery’s new chapter.

The reopening exhibition, Unseen, curated from the gallery’s own collection, was a meditation on transformation, vulnerability, and presence. It avoided triumphalism. Instead, it asked viewers to reconsider the familiar. That tone has since remained a hallmark of the institution’s programming. Major shows have blended international prestige with regional responsiveness, placing global artists alongside South Island voices without condescension or tokenism.

The gallery’s architecture itself, with its glass façade and internal openness, reflects this mission. It invites transparency. Public programming includes artist talks, community workshops, late-night events, and digital experiments. The permanent collection—once anchored by canonical landscape painting—has expanded to embrace installation, digital media, sculpture, and conceptual practice.

Perhaps most significantly, the gallery has played an active role in commissioning new works for public space. This reflects a broader shift: the institution is no longer a container, but a collaborator. Whether in the form of Neil Dawson’s hovering Fanfare sculpture or temporary projections on city buildings, the gallery operates as a producer as much as a presenter.

Its continued challenge, however, remains structural. Funding, audience engagement, and the role of civic art in a still-recovering city are ongoing negotiations. But its presence—stable, ambitious, and flexible—has helped anchor Christchurch’s cultural resurgence.

Gap Filler, Scape, and the aesthetics of impermanence

While the formal institutions have regained their footing, the spirit of experimentation seeded during the earthquake years has not vanished. It survives in organizations like Gap Filler, Life in Vacant Spaces, and the Scape Public Art biennial—all of which have helped to redefine how, where, and for whom art is made.

Gap Filler, in particular, continues to mount projects that challenge the boundary between art and urban design. Whether through bike-powered cinemas, mobile dance floors, or interactive urban games, their projects resist monumentality. The aesthetic is playful, provisional, and often co-created with the public. Even as the city stabilizes, this ethos remains valuable: it offers an antidote to over-planned redevelopment and speaks to the improvisational character of Christchurch’s new urban life.

Scape Public Art, by contrast, brings more established artists into public dialogue. Its large-scale commissions—by local, national, and international figures—punctuate the city with sculptural installations that range from monumental to ephemeral. While early iterations of Scape focused on temporary work, more recent cycles have included permanent pieces, reflecting the city’s transition from transience to anchoring.

What unites these efforts is their embrace of site. Public art in Christchurch rarely feels dislocated. It often responds to specific histories, voids, or communities. Artists walk the sites, research the blocks, talk to residents. The results are not always flashy, but they are often thoughtful, layered, and quietly resonant.

This participatory, embedded approach has become a signature of the city’s contemporary art scene. Even artists working in traditional media—painting, print, video—often incorporate research, oral history, or location-based methods. The line between visual art and social practice has blurred.

Current directions in painting, sculpture, and installation

Contemporary art in Christchurch today is defined less by any one aesthetic movement than by a shared willingness to respond—whether to environment, history, or form. A number of painters, sculptors, and interdisciplinary artists now work across media and institutions, shaping a scene that is small but deeply engaged.

Notable themes include:

- Material intelligence: Artists such as Julia Morison continue to explore the formal and sensual properties of materials—resin, pigment, fabric, metal—often in large-scale, installation-based formats.

- Conceptual cartography: Others, like Pauline Rhodes, use walking, mapping, and subtle environmental interventions as their artistic method—blending sculpture, ecology, and spatial theory.

- Abstract figuration and text: Artists like Philip Trusttum and emerging voices such as Ella Sutherland have engaged language, gesture, and structure in hybrid works that combine text, design, and visual rhythm.

There is also a healthy interplay between individual practice and institutional support. CoCA (Centre of Contemporary Art Toi Moroki), though historically volatile in terms of funding and direction, has remained a critical site for experimental work. Smaller galleries, pop-ups, and university-affiliated spaces continue to offer platforms for new voices, especially recent Ilam graduates.

One of the more exciting developments has been the emergence of interdisciplinary and collaborative projects: performances that bleed into sculpture, publications that function as exhibitions, sound works installed in public parks. Christchurch, for all its size, punches above its weight in this area—perhaps because its artists have long been required to adapt, to improvise, and to self-organize.

The city’s newer architecture, while still controversial in places, also offers new canvases. Buildings like Tūranga, the central library, incorporate light installations, integrated design commissions, and digital art walls. These projects reflect a deeper institutional recognition that art is not a luxury—it’s part of civic life.

Contemporary Christchurch art is not defined by stylistic unity. It is defined by resilience, responsiveness, and a kind of aesthetic humility. Its institutions have survived catastrophe. Its artists have learned to work with rubble, with gaps, with impermanence. And now, as permanence begins to return, they carry forward not nostalgia, but a new visual intelligence—rooted in site, shaped by community, and attuned to a landscape that is always shifting.

Tensions and Continuities in the South Island Eye

Christchurch has always seen differently. Whether shaped by Anglican idealism, scientific observation, postwar civic pride, or earthquake-induced improvisation, the city’s visual culture has been defined by a distinctive eye—sober, deliberate, and tuned to place. And yet, beneath the surface, it is also a site of tension: between regional identity and international influence, between continuity and rupture, between the weight of tradition and the demands of reinvention. In this final reckoning, the art history of Christchurch is not a closed narrative, but a landscape still being surveyed, redrawn, and made visible.

The push-pull of regionalism and globalism in art

For more than a century, Christchurch artists have looked outward—to London, to Sydney, to New York—and then turned home again. This rhythm, of absorbing external influence and translating it into a local idiom, has been one of the city’s defining strengths. But it has also generated a persistent anxiety: how to remain artistically relevant without abandoning specificity.

The city’s artistic institutions have long navigated this friction. The Canterbury Society of Arts, in its time, sought to emulate the Royal Academy while showcasing regional landscapes. The Ilam School of Fine Arts cultivated European-trained instructors who encouraged South Island painters to see Otira or Banks Peninsula as worthy of abstraction. Contemporary curators commission international artists to work in Christchurch, even as they showcase Ilam graduates or artists whose practices remain tied to local sites and histories.