Frances Macdonald, a name that resonates through the corridors of Art Nouveau, is often overshadowed by more famous figures. Yet, her artistic brilliance remains a vital part of the early 20th-century art scene. Born in 1873 in England, Frances was part of a small group that helped shape modern design. Along with her sister Margaret Macdonald, Frances formed a core part of the Glasgow School, a movement that embraced symbolism, abstraction, and the flourishing Art Nouveau style. Her life, though marked by personal struggle and societal barriers, gave rise to artworks that continue to inspire and influence artists today.

Frances Macdonald’s work is a reflection of her innovative mind. Yet, like many women artists of her time, she did not receive the recognition she deserved during her lifetime. However, history has been kinder to her, slowly acknowledging her important contributions to both design and fine arts. Let’s take a journey through Frances Macdonald’s life, exploring the highs, the challenges, and the legacy she left behind. Through her work, we can see how she became one of the most significant yet often overlooked figures in art history.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Frances Macdonald was born into a world where women’s artistic abilities were often underappreciated. Born in Wolverhampton, England, on August 24, 1873, Frances grew up in a household that valued creativity. Her father was a successful engineer and inventor, and this intellectual environment likely influenced her artistic pursuits. Frances, along with her older sister Margaret, developed a passion for the arts at a young age. The sisters were known for their close bond, a connection that would carry them through their artistic careers.

When the Macdonald family moved to Glasgow in 1890, Frances and Margaret enrolled in the Glasgow School of Art. At this time, Glasgow was a burgeoning center for creativity and design, attracting young artists from all over the country. The two sisters quickly made their mark at the school, not just for their talent but also for their distinctive style. Frances and Margaret, along with fellow students like Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Herbert MacNair, would later form the group known as “The Glasgow Four.” This group became the face of the Glasgow Style, a unique blend of Art Nouveau, symbolism, and Celtic imagery.

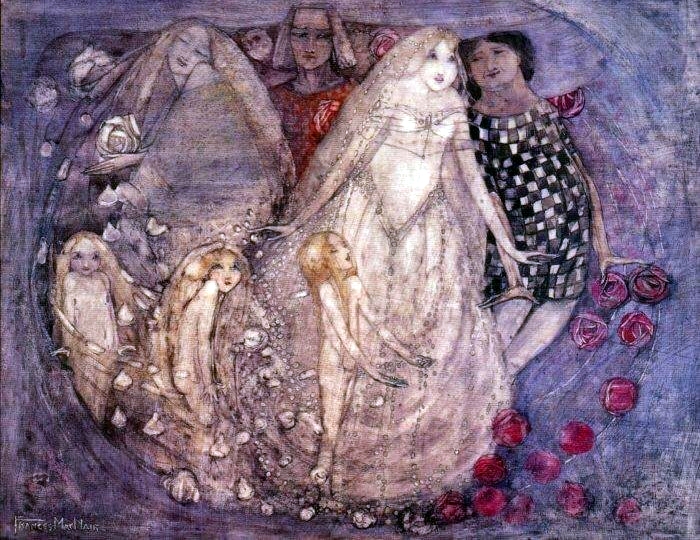

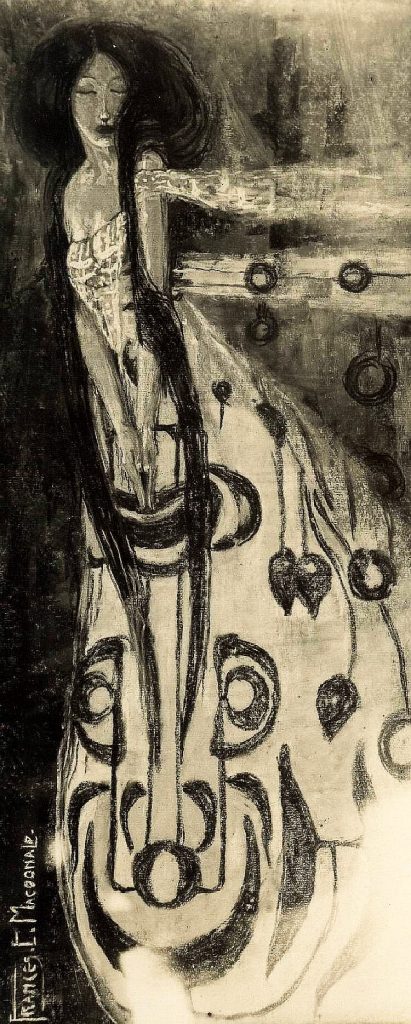

It was during these early years that Frances began to develop her artistic voice. Her work was often characterized by flowing lines, stylized figures, and an almost mystical quality. The influence of Celtic mythology and nature was clear in much of her early work. She also experimented with various media, from painting to embroidery and metalwork. Frances and Margaret were not just painters; they were designers in the truest sense of the word, contributing to everything from interior design to furniture.

The Glasgow Style and the Formation of “The Four”

The Glasgow School of Art was a hotbed for new ideas, and Frances was at the heart of it. It was here that she met Herbert MacNair, whom she would later marry, and Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Margaret’s future husband. Together, the four of them became known as “The Four,” a group whose collaboration would define an era of design. They were all deeply interested in symbolism and mysticism, which can be seen throughout their work. Their designs often featured elongated human forms, organic shapes, and intricate details that seemed to flow naturally from one element to another.

The group’s work was distinctive, blending Art Nouveau’s flowing lines with a Celtic aesthetic that was deeply rooted in their Scottish heritage. They were also highly influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement, which emphasized craftsmanship and the beauty of hand-made objects. Frances’ work from this period is notable for its ethereal quality, often featuring delicate figures surrounded by intricate patterns and organic shapes. Her pieces were dreamlike, often drawing from folklore and mythology to create a sense of mystery and otherworldliness.

Frances and her sister Margaret shared a particularly close bond, often working side by side on projects. Together, they created stunning collaborative works, including paintings, textiles, and interior designs. One of their most famous collaborations was the decoration of Miss Cranston’s Tea Rooms in Glasgow, a project that epitomized the Glasgow Style. These tea rooms became cultural landmarks, showcasing the distinctive style that “The Four” had developed together.

However, despite their success, Frances and Margaret faced significant challenges as women artists. Their work was often dismissed as “feminine” or “decorative,” labels that were used to belittle their contributions. While their male counterparts, particularly Charles Rennie Mackintosh, gained recognition and acclaim, Frances and Margaret struggled to receive the same level of attention. This lack of recognition was a constant struggle throughout Frances’ life, and it’s one of the reasons her work is less well-known today.

Marriage to Herbert MacNair and Artistic Evolution

In 1899, Frances married fellow artist Herbert MacNair. The two had been close collaborators for years, and their marriage marked a new chapter in Frances’ life. MacNair, like Frances, was deeply involved in the Glasgow School and shared her passion for symbolism and Art Nouveau. Together, they moved to Liverpool, where MacNair had taken up a teaching position at the School of Architecture and Applied Art. This move was both a blessing and a challenge for Frances. On one hand, it provided her with new opportunities and a new environment to inspire her work. On the other hand, it also meant leaving behind the tight-knit artistic community she had built in Glasgow.

In Liverpool, Frances continued to develop her unique artistic voice. Her work became more experimental, incorporating abstract shapes and dreamlike figures. She also began to explore more personal themes, drawing on her experiences as a woman and an artist. However, the move to Liverpool also marked the beginning of a difficult period in Frances’ life. While her husband’s career thrived, Frances struggled to find the same level of success. The art world, still dominated by men, was not kind to women artists, and Frances’ work was often overlooked in favor of her husband’s.

Despite these challenges, Frances continued to produce stunning works of art. Her pieces from this period are deeply introspective, often featuring solitary figures in dreamlike landscapes. These works reflect Frances’ own feelings of isolation and frustration, as she grappled with the limitations placed on her by society. In many ways, her art became an outlet for her emotions, a way to express the feelings she couldn’t put into words.

Tragically, Frances’ personal life also began to unravel during this period. Her marriage to MacNair was strained, and the couple faced financial difficulties. Frances, who had always struggled with depression, found it increasingly difficult to cope. Despite her struggles, she continued to work, producing some of her most powerful and haunting pieces during this time.

Decline and Rediscovery

As the 20th century progressed, Frances Macdonald’s career began to decline. The Art Nouveau style that had defined her early work fell out of fashion, and the world of art moved on to new movements like Modernism. Frances, who had always been deeply connected to the decorative and symbolic elements of Art Nouveau, found herself increasingly out of step with the art world. Her work, once celebrated for its innovation, was now seen as outdated and irrelevant.

The strain of these changes, combined with her personal struggles, took a toll on Frances’ mental health. She became increasingly reclusive, withdrawing from the art world and focusing on her family. Sadly, her depression worsened, and in 1921, Frances took her own life. She was just 48 years old.

For many years after her death, Frances Macdonald’s work was largely forgotten. While her male contemporaries, like Charles Rennie Mackintosh, were celebrated as pioneers of modern design, Frances’ contributions were overlooked. Her work was dismissed as “decorative,” a label that minimized the importance of her artistic vision.

However, in recent decades, there has been a renewed interest in Frances Macdonald’s work. Scholars and art historians have begun to recognize the importance of her contributions to the Glasgow Style and to the broader Art Nouveau movement. Exhibitions of her work have been held, and her pieces are now part of major collections in museums around the world. This rediscovery of Frances Macdonald’s work has allowed her to finally receive the recognition she deserved during her lifetime.

Legacy of Frances Macdonald

Today, Frances Macdonald is remembered as one of the most important figures of the Glasgow Style. Her work, with its ethereal beauty and symbolic depth, continues to inspire artists and designers. While she may not have received the same level of fame as some of her contemporaries, her contributions to the world of art are undeniable.

Frances Macdonald’s legacy lies in her ability to blend the decorative and the symbolic, creating works that are both visually stunning and deeply meaningful. Her use of organic forms, flowing lines, and mystical imagery set her apart from other artists of her time. She was not afraid to experiment, to push the boundaries of what art could be, and in doing so, she helped pave the way for future generations of artists.

In recent years, Frances Macdonald’s work has been the subject of renewed interest, with exhibitions and retrospectives dedicated to her life and career. This recognition is long overdue, but it serves as a reminder of the lasting impact that Frances Macdonald has had on the world of art. Her work continues to be studied, admired, and celebrated, ensuring that her legacy will live on for generations to come.

In reflecting on Frances Macdonald’s life and work, one quote from her sister Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh seems especially fitting: “Art is the flower. Life is the green leaf. Let every artist strive to make the leaf.” For Frances, art was not just an expression of beauty, but a reflection of life itself—an idea that remains as powerful today as it was in her time.

Through her groundbreaking work, Frances Macdonald made her own leaf in the garden of art history, one that will continue to bloom for years to come.