Baba Yaga is one of the oldest and most enduring figures in Slavic folklore, feared and revered in equal measure. Across Poland, Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Czechia, Slovakia, and the Balkans, children have long been warned not to stray into the woods—or “Baba Jaga” or “Ježibaba” might get them. More than just a bogeyman, she is a witch-like figure who guards the wild borderlands between civilization and chaos. She tests the souls of those who seek her and punishes those who trespass unwisely.

Her image has inspired centuries of art, illustration, literature, and modern media. From embroidered icons and folk woodcuts to avant-garde painting and digital games, Baba Yaga’s visual evolution tells the story of how a myth survives by adapting. This article follows her transformation through seven key stages in visual history—from her oral roots to the fine art of today.

The Roots of Baba Yaga in Slavic Myth and Folklore

Baba Yaga is not exclusive to Russia. Her name and characteristics appear widely across the Slavic world. In Poland, she’s Baba Jaga; in Czechia and Slovakia, she’s known as Ježibaba; in Serbia and Croatia, she overlaps with Baba Roga. Though names vary, the traits remain strikingly consistent: an old crone with supernatural powers, dwelling deep in the forest in a hut that often moves or turns. She may ride in a mortar and wield a broom, and she often appears as a test of character for those who wander into her realm.

The earliest known written mention of Baba Yaga by name appeared in 1755 in a Russian grammar book by Mikhail Lomonosov, but her folklore roots stretch far deeper into the pre-Christian past. She was likely shaped by ancient forest deities, death goddesses, and wise women revered in Slavic pagan tradition. Her dual role as both a devourer and a guide mirrors archetypes found throughout Indo-European mythology. In oral tales from Polish and Slovak villages, she both curses and cures, depending on the moral of the story.

Origins and Evolution in Oral Tradition

In the 19th century, collectors like Alexander Afanasyev in Russia and Oskar Kolberg in Poland began compiling folk stories, preserving many Baba Yaga tales in print. Afanasyev’s massive anthology (1850s–1860s) introduced Russian readers to vivid images of Baba Yaga flying through the skies, chasing heroes, or guarding enchanted objects. Kolberg’s Polish folktale collections documented Baba Jaga in a similar light—sometimes helpful, often terrifying, always powerful. In both traditions, she appears as a test of moral strength.

These tales emphasized trials, transformation, and spiritual journeys. Children were told never to enter the forest alone, lest Baba Yaga catch and eat them—but the clever and humble might win her favor. The forest symbolized the unknown, and Baba Yaga was its sovereign. This blend of fear and fascination made her a potent subject for visual storytelling once print and illustration developed further in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Baba Yaga in Early Slavic Illustration (18th–19th Centuries)

As Slavic nations developed their own national art traditions in the 18th and 19th centuries, artists and illustrators turned to folklore as a source of cultural pride. Fairy tale books, woodcuts, and church manuscripts increasingly included depictions of local legends—including Baba Yaga. In both Russian and Polish art, she was rendered in ways that emphasized her otherworldliness: a skeletal face, iron teeth, clawed fingers, and a twisted spine.

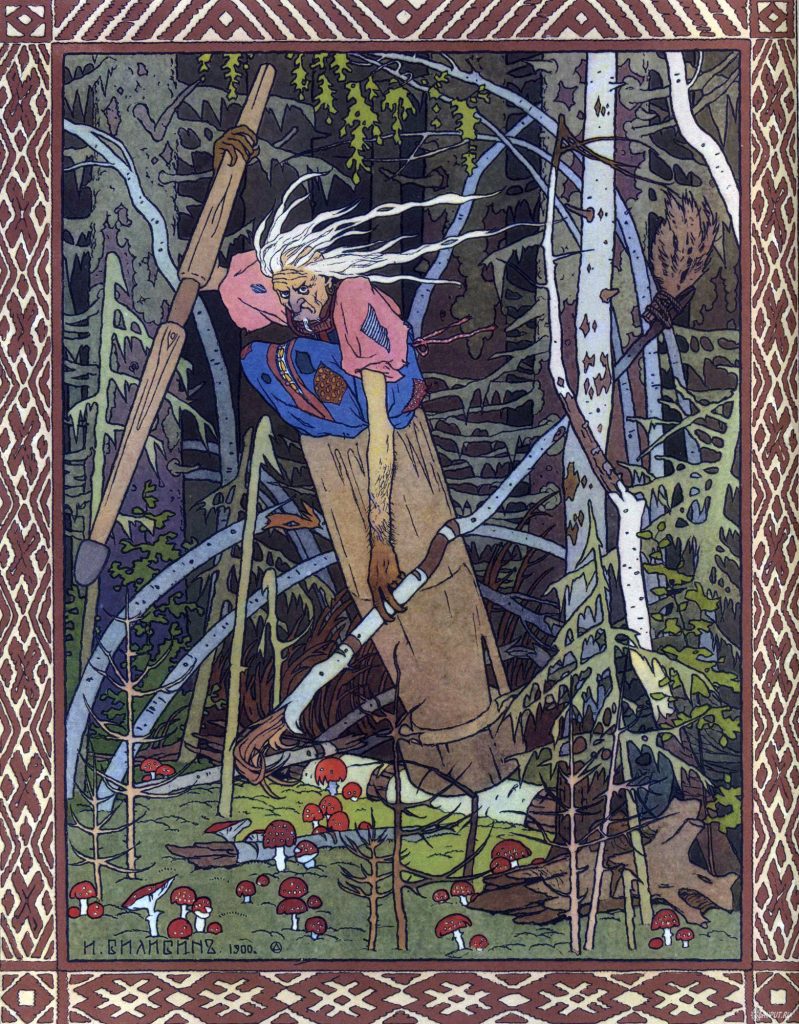

In Russia, the most famous early artist to visualize Baba Yaga was Ivan Bilibin (1876–1942), whose illustrations in folk tale books from 1899 to 1902 set the standard for her appearance. Bilibin’s work combined traditional Slavic ornamentation with Art Nouveau influences, portraying Baba Yaga with an eerie majesty. Her house stood atop chicken legs, surrounded by skulls, and her broom swept away her tracks. These images shaped generations of Russian readers.

Ivan Bilibin and the Golden Age of Illustration

Polish artists were no less engaged with the visual culture of folklore. Though Baba Jaga was not illustrated as frequently as in Russia, she appeared in 19th-century Polish chapbooks, woodcuts, and children’s stories—often depicted as a haggard, hunched woman with wild hair and a sinister stare. Illustrators like Jan Styka and others included witch figures in broader folkloric compositions, drawing on oral traditions known throughout rural Galicia and Podkarpacie.

In Belarus and Ukraine, local variations of Baba Yaga appeared in lubok prints—popular folk prints sold at markets—depicting her flying through the air or confronting travelers. Though crude in style, they carried deep symbolic meaning. These regional artworks, whether finely illustrated or roughly carved, show how deeply embedded Baba Yaga was in Slavic consciousness. Before Soviet standardization, each nation gave her its own colors, traits, and setting.

Baba Yaga and the Slavic Avant-Garde (1900–1930)

With the rise of modernism, artists in Slavic countries began using folklore not just to preserve the past, but to challenge the present. The avant-garde in Russia, Poland, Ukraine, and Czechia embraced myth as a way to confront industrialization, war, and the loss of spiritual identity. Baba Yaga was reborn as a Symbolist and Futurist muse—less literal, more psychological, and often abstract.

Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962), a central figure in the Russian avant-garde, integrated folk motifs into radical new styles. Her prints and set designs drew heavily on fairy tale themes, including Baba Yaga, forest spirits, and village legends. She believed modern art should spring from native soil, not imitate Western trends. Her works from the 1910s showed witch-like women with elongated limbs and piercing eyes, drawing clear inspiration from old tales.

Myth Meets Modernism in Symbolist and Futurist Works

In Poland, Symbolist artists like Stanisław Wyspiański (1869–1907) and Józef Mehoffer (1869–1946) tapped into Slavic myth in stained glass, theatre, and painting. While they didn’t depict Baba Yaga directly, their use of crones, witches, and forest beings helped lay the groundwork for later artists to explore her image in fine art. The atmosphere of mystery, decay, and renewal was shared across the Slavic modernist scene.

Avant-garde Czech artists such as Toyen (Marie Čermínová, 1902–1980) used folklore symbols—including the witch or Ježibaba—in surrealist compositions. These works often fused eroticism, death, and fairy tale imagery, transforming old crones into ghostly avatars of inner torment. In this era, Baba Yaga morphed from narrative character into archetype, her image molded by each artist’s vision of the unconscious.

Soviet and Socialist-Era Depictions (1930–1980)

Throughout the Soviet Union and its satellite states, folklore was embraced—but only if it could be adapted to serve the socialist cause. Baba Yaga remained popular in books, plays, and animations, especially for children. However, her darker spiritual and mystical aspects were suppressed. She became a clownish villain or a stern grandmother—something to be laughed at or outwitted.

In the USSR, Leonid Amalrik and Valentina Brumberg developed animated shorts that featured Baba Yaga as a caricature, such as The Magic Swan Geese (1949). These portrayals maintained her broomstick and hut but removed her wildness. Evgeny Rachev’s illustrations from the 1950s to 1970s followed suit: they presented her as disheveled and irritable, but not threatening. The moral lessons remained, but the supernatural was watered down.

Baba Yaga as a Children’s Character and Ideological Symbol

In Poland, Czechia, and East Germany, similar portrayals appeared in fairy tale books and state-approved stories. Baba Jaga was now a harmless forest-dweller who taught children to clean their rooms or avoid laziness. Illustrators like Jan Marcin Szancer softened the crone’s features, replacing menace with mild humor. Her house still stood on chicken legs, but now it had lace curtains and a friendly pet cat.

Despite state control, folklore endured. Teachers, grandparents, and folk artists kept older stories alive in rural areas, where Baba Yaga remained a figure of warning and wonder. Her image—however softened—still held cultural power. And in places like Slovakia and Bulgaria, puppet theaters and marionette shows kept her alive on stage, preserving her role as a challenge to virtue and vice alike.

Baba Yaga in Contemporary Fine Art (1980–2000s)

By the 1980s, the fall of communism and the rise of feminist thought allowed artists across Eastern Europe to revisit Baba Yaga in new ways. She was no longer just a character in moral tales, but a symbol of the suppressed feminine, the wild woman, and the natural world. Artists began portraying her as a source of ancient wisdom, not just fear.

In Poland, Katarzyna Górna and Monika Drożyńska created mixed-media and performance pieces referencing Baba Jaga as a feminist and ecological figure. Their work aligned with the rising interest in reclaiming old myths for women’s narratives. Clarissa Pinkola Estés’ 1992 book Women Who Run With the Wolves helped popularize this reinterpretation, framing Baba Yaga as an elder figure of truth and instinct.

Feminist, Psychological, and Esoteric Reimaginings

Art exhibitions in Warsaw, Brno, and Lviv featured Baba Yaga-inspired sculptures, installations, and textile art. These often emphasized her connection to the earth, bones, and time. Artists portrayed her as neither villain nor saint, but as a liminal force. She became a visual shorthand for knowledge outside modern norms—especially knowledge passed down from mothers and grandmothers.

Artists like Maria Kapajeva and Anna Stavychenko used Baba Yaga to explore the loss of tradition and female isolation in post-Soviet life. Their work often combined family artifacts, folklore motifs, and stark imagery of the forest or domestic space. As the Iron Curtain fell, Baba Yaga stepped back into full mythic power—older than ideology, and harder to define than ever.

Baba Yaga in Global Pop Culture and Graphic Art (2000–Today)

In recent decades, Baba Yaga has become a global figure, appearing in American films, Japanese games, French comics, and beyond. Her strange combination of horror and wisdom makes her a perfect fit for modern fantasy and horror genres. Whether she’s depicted as a monster, a mentor, or a hermit, artists keep returning to her.

In Hellboy (2004, 2019), Mike Mignola reimagined Baba Yaga as a vengeful undead witch with one eye, haunting an alternate dimension. In John Wick (2014), her name is used metaphorically for the protagonist, cementing her as a shorthand for fear and respect. Video games like Rise of the Tomb Raider (2015) and The Witcher series draw heavily on her visual traits—gnarled hands, bone fences, and deep forest homes.

From Comic Books to Video Games

Eastern European artists continue to reinterpret her for younger audiences. Books like Baba Yaga’s Assistant (2015) present her as a grumpy mentor training a new generation. Animated series and indie games include chicken-legged huts, skull lanterns, and talking animals—all rooted in Slavic myth but adapted for global screens. The figure of Baba Yaga has gone digital, but her essence remains.

Artists around the world now use her image to challenge industrialism, consumerism, and the loss of nature. She has appeared in eco-feminist posters, ceramic installations, and AI-generated artworks. Despite all changes, the witch of the woods still beckons from the edge of civilization, daring us to ask hard questions and face the unknown.

The Symbolic Power of Baba Yaga in Visual Culture

What gives Baba Yaga her staying power is her refusal to conform. She is not purely good or evil, beautiful or hideous, wise or mad—she is all these things at once. That makes her a powerful figure for artists who want to explore the gray areas of life. Across Slavic cultures, she represents the borderlands: between safety and danger, childhood and adulthood, order and chaos.

Her symbolic power lies in the forest—the place where rules don’t apply and lessons are hard-won. In Polish, Czech, and Serbian art, she is often tied to bone, fire, and transformation. She breaks down heroes and rebuilds them. Whether in crayon drawings or oil paintings, she pulls viewers into an ancient space where truth hides behind riddles.

What Artists See in the Witch of the Woods

For many, Baba Yaga stands for ancestral knowledge—the kind that lives in women’s stories, rituals, and songs. Her hut spins and moves because she is never quite where we expect her. She has become a symbol for everything that resists control: old age, femininity, nature, and spiritual depth. Artists see in her a reflection of their own search for identity.

As long as forests exist—and fears dwell in the human heart—Baba Yaga will remain. She appears in dreams, warnings, fairy tales, and gallery walls. Every generation redraws her face, but the old eyes stay the same. The witch of the woods is not going anywhere.

Key Takeaways

- Baba Yaga is a shared figure across Russia, Poland, Ukraine, Czechia, Slovakia, and the Balkans.

- Her name and image vary, but core traits remain consistent in all Slavic traditions.

- Artists like Ivan Bilibin and Natalia Goncharova visualized her in rich detail.

- Modern interpretations range from feminist symbolism to horror fantasy.

- She endures as a visual metaphor for the untamed, ancient, and ambiguous.

FAQs

- Is Baba Yaga only Russian?

No, she appears in Polish (Baba Jaga), Czech (Ježibaba), Serbian (Baba Roga), and other Slavic traditions. - When did Baba Yaga first appear in art?

In the 18th and 19th centuries, with major illustration work by Ivan Bilibin beginning in 1899. - How is she used in modern culture?

She appears in comics, films, games, feminist art, and environmental installations. - Was she always evil?

No—she could help or harm depending on the character of the person she encountered. - Why is Baba Yaga important today?

She represents wisdom, fear, nature, and tradition—powerful symbols in modern life.