On April 3, 1897, a group of artists filed quietly but defiantly out of the Künstlerhaus in Vienna, the official home of the city’s conservative art establishment. Gustav Klimt, still only in his mid-thirties but already a celebrated muralist and portraitist, led the departure. With him were painters Koloman Moser, Carl Moll, and architects Josef Hoffmann and Joseph Maria Olbrich—figures now canonical, but at that moment considered mutinous. They called themselves the Secession, and their decision to break from the Künstlerhaus was not merely about artistic style. It was an act of structural revolt against institutional control, bureaucratic censorship, and the suffocating weight of the imperial bourgeoisie’s taste.

Vienna in the 1890s was, on the surface, a place of exquisite formality. The empire still stood, and Emperor Franz Joseph reigned as both a political and cultural patriarch. The Ringstrasse—grand and rational—lined the city like a corset, containing within it an elite aesthetic order: formal portraiture, academic historicism, and the hierarchies of state-sanctioned beauty. Yet beneath this surface lay a tremor of discontent. Artists, writers, architects, and musicians were growing restless with repetition, with polish for its own sake, and with art as a servant to class privilege. The Vienna Secession gave that restlessness a name.

A building without a building

The Secessionists had no gallery, no sponsor, no fixed doctrine. But they had conviction—and a plan. From the beginning, their goal was not merely to exhibit their own work but to create a platform for what they called “freedom in art.” That phrase was radical in its ambiguity. Freedom from what? And freedom to do what, exactly? The answer came gradually: freedom from academic gatekeepers, from the thematic straitjacket of history painting, and from an ornamentalism that served only elite interiors. In its place, they sought a living synthesis—an art that could fuse painting, sculpture, architecture, and design into a holistic experience.

They declared their position in a manifesto published that spring, heavily influenced by Symbolist language and European idealist philosophy. “To every age its art. To every art its freedom,” the motto read. The words would soon be inscribed in gold on the façade of a building that didn’t yet exist: the Secession Building, still only an idea in the mind of Olbrich, the group’s youngest and most architecturally ambitious member.

As summer passed, sketches for the new building began to circulate. A white cube capped with a gilded laurel dome, the structure bore no resemblance to Vienna’s palatial exhibition halls. It looked pagan, defiant, clean, and vegetal—like a funerary temple for the old order. The city authorities, ever cautious, hesitated. Funding trickled in from private patrons and progressive industrialists, but the climate remained hostile.

Klimt’s Love and the emergence of a new eroticism

While the Secessionists organized, Gustav Klimt painted. In the same year as the group’s founding, he completed Die Liebe (Love), a striking oil canvas now held by the Belvedere. The work is transitional—not yet the gold-drenched mysticism of his later fame, but already suffused with symbolic sensuality. A central couple embraces in a shadowed alcove, the male figure protective, the female yielding. Around them, ghostly faces emerge from darkness: childhood, death, and maternal grief drift like fragments through the edges of vision.

What shocked viewers was not the eroticism—it was the introspection. Klimt’s painting lacked the idealizing clarity of Academic love scenes. Here, love was thick, private, unspeakably tender, and freighted with dread. It belonged to the inner life, not to allegory. In Love, Klimt introduced a psychic architecture that would define Viennese modernism in the years to come: figures held within invisible enclosures, framed by the invisible constraints of memory and desire.

In a sense, the painting was the first true Secessionist manifesto—not in words, but in form. The subject dissolved into sensation. Contour softened. Narrative withdrew. Klimt was stepping away from public art and into what Freud—then a few years into his early psychoanalytic writings—would soon call the unconscious.

Public condemnation and private alliances

Not everyone was ready for this turn inward. The Viennese press, particularly papers like Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, dismissed the Secessionists as immature, unpatriotic, or unserious. Die Zeit questioned whether their movement was merely decorative—pretty patterns in search of substance. The backlash was cultural, not just aesthetic. These were not harmless rebels but threats to the city’s self-image as a beacon of classical order.

Yet the Secessionists found support in unlikely corners. Wealthy Jewish patrons—among them members of the Wittgenstein and Lederer families—began to fund the movement quietly, recognizing in its anti-academic stance a parallel to their own precarious position within Austrian society. Klimt’s clientele soon included both rebellious aristocrats and freethinking industrialists, many of whom commissioned works that walked the line between portraiture and myth.

Three motifs defined these early commissions:

- The female body as site of mystery and transformation, no longer idealized but vulnerable and strange.

- Floral or geometric ornament used not as decoration but as rhythm, enclosing figures in aesthetic states.

- An emphasis on gold and material surface, pointing toward the medieval and the sacred rather than the Enlightenment and the rational.

These choices confused critics but fascinated younger artists. The idea that painting could be psychological space, that design could be metaphysical, that a building could be an argument—all this was new.

The surprise within the revolt

What few anticipated, even among the founders, was how collaborative the Secession would become. Unlike most artistic breakaways, which were often the vanity projects of charismatic individuals, the Secession evolved into a working group, with committees, publications (Ver Sacrum would follow in 1898), and public exhibitions. It functioned more like a laboratory than a salon. Hoffmann and Olbrich would go on to establish the Wiener Werkstätte; Moser would pioneer graphic design as an autonomous art; Klimt would increasingly retreat from public commissions and concentrate on complex symbolic works for private spaces.

The real rupture of 1897 was not stylistic—it was infrastructural. The Secession created new paths for exhibition, criticism, and interdisciplinary practice. It imagined art not as the product of genius, but of structure: schools, journals, guilds, and rooms in which art and life could meet on equal terms.

An empire’s façade begins to crack

The Secessionists were still young in 1897, still idealistic. Their building would not open until the following year. Their public triumphs were ahead. But in their defiance, they revealed the soft underbelly of an empire in aesthetic decline. Behind the polished white marble of Vienna’s academies lay uncertainty, censorship, and control. The Secession exposed the gap between appearances and reality, between the empire’s self-image and its cultural fragility.

In the long arc of modernism, 1897 would prove to be less a spark than a structural shift—the laying of pipes beneath the city, through which ideas would flow for the next three decades. The smoke over the Danube was not from revolution, but from something quieter, more enduring: the slow, deliberate burning of the past.

Chapter 2: A New Jerusalem in Munich — Kandinsky’s Conversion Experience

The lawyer who saw color sing

In 1897, Wassily Kandinsky stood at the edge of a quiet, irreversible decision. Only a year earlier, he had been living in Moscow, a young man with a doctorate in law and economics and a promising academic career ahead. He had been offered a professorship at the University of Dorpat, a safe path into intellectual respectability. But something had broken loose inside him. A year prior, he had seen Claude Monet’s Haystacks in a traveling exhibition of French Impressionist painting. He described the moment later as a kind of dislocation: he could no longer distinguish subject from sensation, or logic from form. That year, he abandoned the law and left Russia altogether, moving to Munich in the autumn of 1896 and throwing himself headlong into art. By 1897, he had enrolled at the private school of Anton Ažbe, a Slovenian painter known for his liberal teaching style, and was beginning to draw constantly—landscapes, figures, ornament, anatomy, all with an almost feverish drive.

Munich was not then an artistic capital in the manner of Paris or Vienna. But for a Russian with Symbolist leanings and a hunger for renewal, it offered something even more important: freedom from cultural expectation. It was a city in quiet ferment, where the Jugendstil movement was just beginning to emerge, and where Byzantine mosaics, Bavarian folk art, and Wagnerian theatricality coexisted in uneasy harmony. Kandinsky arrived without contacts, without patrons, and without significant talent—at least in the academic sense. But something was gestating.

A student of everything but style

Kandinsky’s early months at the Ažbe School in 1897 were humble, even humiliating. Ažbe taught in a famously abstract manner, starting students not with objects but with the ball principle—a volumetric exercise in shading and contour that was meant to cultivate form through internal understanding. It was the opposite of Russian academic discipline, and Kandinsky struggled. His early drawings were clumsy. He wrote letters describing his attempts to sketch figures in motion, to understand color not as an adjective but as a force. He was already in his thirties—twice the age of many of his classmates—and filled pages of his notebooks not with techniques, but with questions. What did a line want? Could color move faster than form? What made a composition alive?

This was not yet the Kandinsky who would publish Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1911) or paint the first abstract canvases of the 20th century. But 1897 marks the beginning of the internal architecture that would carry him toward that later revolution. While his peers copied still lifes and nudes, Kandinsky wandered the city sketching street signs, church interiors, and medieval illuminations. The formal curriculum interested him less than the idea of art as a vessel of inner necessity—a phrase he would later coin. His visual vocabulary was already being shaped by forces outside academic painting:

- The swirling symmetry of Slavic folk embroidery.

- The iconographic stylization of Russian Orthodox imagery.

- The flat, rhythmic repetition of decorative borders in illuminated manuscripts.

These were not considered serious references in the Munich of the 1890s. But they lodged in him with surprising force.

A strange convergence: folk ornament, German mysticism, and abstraction

By late 1897, Kandinsky had begun to exhibit his student works in local salons. Nothing in them would have startled a viewer—yet. They were small oils and drawings: Alpine villages, peasants, simplified natural scenes. But even here, something odd began to appear. The color relationships felt strangely detached from the subject. In one painting of a blue-roofed house, the sky was a molten violet, with no atmospheric logic. In a drawing of a man plowing, the furrows of earth were stylized into almost musical forms, as if inscribed rather than rendered. Critics ignored them; classmates found them confusing. But Kandinsky saw in these experiments a way of feeling the world that was not bound by description.

He wrote in a letter that year: “I feel that color has a voice, that it sings.” This was not mere poeticism. Kandinsky suffered from a mild form of synesthesia—a perceptual crossing of the senses—though he never described it diagnostically. For him, yellow could be shrill, red pulsing, blue could hum. Munich, with its Wagnerian revivals and esoteric Catholicism, gave him room to imagine this synesthesia as a spiritual calling. The line between sound, sight, and symbol began to dissolve.

Three surprising sources shaped Kandinsky’s internal evolution during this period:

- Russian folk motifs, which he began to collect and study in earnest during holidays back home.

- Schopenhauer and Theosophical writings, which reached him via German students and bookstores in Munich.

- Children’s drawings, which he sketched from memory, fascinated by their disregard for realism.

These materials would later come to dominate his mature work. But in 1897, they were merely colliding inside him, unresolved and flickering. What held them together was not style, but desire.

The turning point without a canvas

Kandinsky produced no major work in 1897. There is no signature painting from this year that scholars point to, no exhibit that cemented his presence in Munich’s scene. But it was, quietly, his year of conversion. Not to a style, but to a vocation. He had left the law, yes. But more than that, he had redefined what art could be responsible for. In the Russian academic system, art had been craft. In the legal world, art had been leisure. In Munich, it became something else: an epistemology. A way of knowing what couldn’t be said in prose. A way of ordering experience not around facts, but around necessity.

This internal pivot—between 1897 and 1899—would define the rest of his life. It made possible the later breakthroughs of his Improvisations and Compositions, and allowed him to stand at the forefront of abstraction without reducing painting to formalism. His Munich period was not a gestation in the passive sense; it was a wrestling with form, a refutation of the idea that content had to be visible to be real.

The Bavarian light, the austerity of German pedagogy, and the thick mysticism of central European spiritualism combined in his mind like currents in a tide. He was still drawing figures, still painting hillsides—but his attention was drifting. He was looking beyond the image.

The future seen in reverse

Later in life, Kandinsky would speak of 1897 only in glancing terms. He referred to Munich as his “first city of vision,” but rarely dated its events. But if one were to walk through his 1900s paintings backward—as if rewinding a film—the trail leads unmistakably to this quiet year. No manifesto was issued. No gallery rejected his work. No critic damned him in print. And yet, the transformation was absolute. A lawyer arrived in search of technique. A visionary left in search of the invisible.

What makes 1897 significant in Kandinsky’s life is not what he produced, but what he believed he could now pursue. The year didn’t end in a breakthrough canvas. It ended in a vow: that art could be a metaphysical system. That the surface of a painting was only its most modest offering. That forms, if arranged in the right rhythm, could call something sacred into the world.

Chapter 3: The Visionary and the Void — Edvard Munch in Paris

A specter walks the Seine

In the spring of 1897, Edvard Munch walked once more through the Jardin du Luxembourg, coat tight around him, sketchbook hidden beneath his arm like a secret. The city of Paris, which had overwhelmed him on first arrival in 1889, now breathed differently. It no longer dazzled; it unsettled. For Munch, 1897 was not just a year of artistic productivity—it was a year of psychic unraveling and creative defiance. He had returned to the French capital to show work at the Salon des Indépendants, but more pressingly, to press his case that art must do more than please the eye. It had to bruise. It had to haunt.

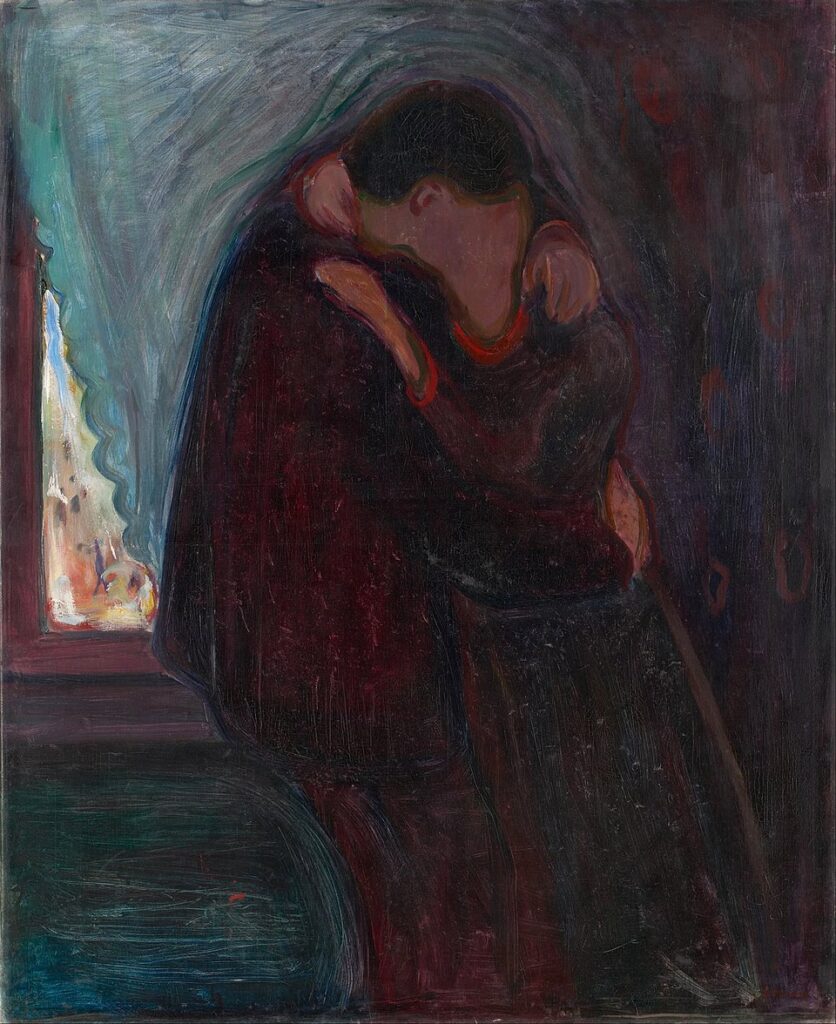

In that year, Munch completed The Kiss—a shadowy, enigmatic painting in which two lovers merge into a single, faceless mass. The image is not erotic in the French sense. It is symbolic, even terrifying, as though the act of love erases identity rather than affirms it. That theme—unity as oblivion—ran like a fever through Munch’s 1897 output. The works he exhibited and developed during this year mapped the human soul at the brink of collapse: erotic longing, death, illness, guilt, and silence.

Symbolism’s haunted guest

Paris in the 1890s was drunk on Symbolism. Poetry, painting, and music all swirled with dreams of the ineffable. But Munch’s sensibility didn’t fit the usual Symbolist mold. Where the French artists veiled their meanings in allegory or classical allusion, Munch pulled from memory, anxiety, and raw psychological impulse. His art in 1897 leaned heavily into his Frieze of Life, an evolving series of paintings that portrayed the full arc of human emotion—from desire to despair—with the somber insistence of ritual.

At the Salon des Indépendants that spring, Munch displayed a suite of these paintings. Critics were divided. Some saw in him a kind of Nordic mysticism—primitive but potent. Others recoiled. As the critic Gustave Geffroy wrote with ambivalence: “There is something of the sickroom in these paintings. One leaves them not enlightened, but affected.” The phrase was apt. Munch’s color palette—mildewed greens, rotting pinks, sallow grays—seemed to sap the light from the gallery walls.

He was not trying to depict scenes. He was trying to externalize states of mind, often dark ones. In this, Munch anticipated the later formulations of Expressionism, but without its violence. His world was quieter, more diseased. He did not explode the figure—he let it dissolve.

The Kiss and the dread of fusion

In The Kiss (1897), a man and woman embrace near a window, but their faces blur into an abstract oval. There is no eye contact, no gaze, no smile—only a mutual smothering. The bodies remain distinct, but the identity has vanished. It is not sensual. It is not romantic. It is, in a way, ritualistic, like a sacrificial rite dressed in domestic calm.

Munch did not explain the painting directly. But his writings from the period—fragments of diary entries and letters—suggest that he saw erotic love as both ecstatic and annihilating. One lover consumes the other. The self disappears in the face of another’s desire. “When I saw them together,” he wrote of an anonymous couple he had observed, “I saw a wound open between them.”

This image of love as wounding, of intimacy as danger, would recur throughout his work:

- In Vampire (1895–1902), the female figure enfolds the man not in a kiss, but in a predatory embrace.

- In Ashes (1894–95), the woman recoils while the man covers his face, suggesting a moment after, not before, passion.

- In Madonna (1894–1895, with lithographic variants in 1897), the ecstasy of the female nude is framed by a halo that is both sacred and funereal.

By 1897, Munch was reworking many of these themes not only in oil, but in print. His lithographs from this period show a growing interest in duplication, mirroring, and psychological echo. Even when the compositions were static, the emotional resonance was volatile.

A visit to Saint-Louis and the beginning of Inheritance

In the late summer of 1897, Munch visited the Hôpital Saint-Louis in Paris, a public hospital known at the time for its treatment of venereal disease and skin disorders. He did not go as a patient. He went to observe. What he saw—particularly among the women and children affected by syphilis—disturbed him deeply. He later spoke of these visits as formative to one of his most disturbing paintings: Inheritance.

Though the final version of Inheritance would not be completed until 1899, its conception began that year. The painting depicts a pale, lethargic woman cradling a child whose body is discolored and lifeless. The child’s expression is vacant, and the woman’s eyes are dark hollows. A red pattern on the wall seems to close in. The scene is not allegorical—it is clinical, unsentimental, but saturated with pain.

In 1897, no other major painter in Paris was attempting such a theme in so direct a form. Degas showed brothels; Toulouse-Lautrec depicted prostitutes with sympathy and irony. But Munch was depicting the moral and biological inheritance of illness, not as a social commentary, but as a cosmic reality.

That year, in a letter to a friend, he wrote: “I have seen the child that no one will take. I have seen what passes from one to another like an unseen chain.” It was this chain—between sin, body, and soul—that he painted again and again.

Print, repetition, and theatricality

Munch also used 1897 to deepen his experiments in printmaking, particularly lithography. His Theatre Programme: John Gabriel Borkman lithograph from that year—created for Ibsen’s late play—shows his engagement with literature, psychology, and mass reproduction. It was a stark design: black silhouettes, stark lines, melancholy faces. But beyond its surface, it reveals how Munch was learning to distill emotional states into reproducible form.

The print medium gave him something oil could not: recurrence. In an age obsessed with originality, Munch embraced repetition—not as laziness, but as strategy. To repeat a face was to reduce it to its symbolic essence. To repeat a gesture was to show that pain had no unique expression. In this, his work echoed Schopenhauer’s idea that human suffering was not episodic, but structural—repeating itself across time and type.

In Paris, surrounded by the triumphant optimism of the Belle Époque, Munch painted and printed like a prophet in reverse. He did not foresee a radiant future. He saw a cracked present. And in doing so, he forged a vocabulary that spoke not to Parisian glory but to Nordic introspection, alienation, and the erotic terror of being seen too closely.

A silence deeper than death

1897 did not make Munch famous. If anything, it deepened his outsider status. He was still regarded by many in Paris as a Symbolist curio—a provincial with talent, but lacking sophistication. Yet within his solitude, a remarkable clarity emerged. He was building a system, not a style. Every painting, every print, every emotional permutation was part of a single inquiry: what happens to the soul when it meets the body?

In that question lay his power. And in 1897, far from the fashion salons and aesthetic cafés of Montmartre, Munch was beginning to answer it in a visual language no one else could yet read.

Chapter 4: More Real Than Life — Rodin’s Balzac Scandal

A giant under a sheet

In 1897, Auguste Rodin completed the clay model of what he considered his greatest sculpture: a towering, robed figure of Honoré de Balzac, the French novelist who had died nearly half a century earlier. It had taken him six years, and the Société des Gens de Lettres, which had commissioned the piece in 1891, was growing impatient. Balzac’s admirers had envisioned something sober and commemorative: perhaps a lifelike rendering of the writer at his desk, or a heroic pose with manuscript in hand. What Rodin delivered instead was a massive, semi-abstract form—swaddled in folds of plaster, head thrown back in contemplation or agony, face looming like a grotesque mask from some primeval dream.

It was, in every way, a refusal. A refusal of realism, of flattery, of commemorative convention. Rodin had modeled the figure not from life (Balzac was long dead) nor from portrait sittings or busts, but from his reading of the man’s work, his letters, his myth. The result was more golem than gentleman. And it horrified nearly everyone who saw it.

Though the plaster model would not be publicly exhibited until 1898, it was essentially completed in 1897—and even in private viewings, it began to stir unrest. Rodin had taken a state commission and returned something private, monstrous, and utterly modern: a portrait of creative energy as mass, not likeness.

Not a likeness, but a force

The original commission had stipulated a faithful representation of Balzac, and Rodin had initially complied. He visited Balzac’s hometown in Tours, interviewed surviving relatives, and examined daguerreotypes and drawings. For two years, he produced sketches and small studies. But he could not find the man. The body was wrong. The face too ordinary. Balzac had been famously unkempt, obese, and physically unimpressive. Rodin abandoned accuracy and turned inward.

“I did not see Balzac in the flesh,” Rodin later wrote. “I saw his legend. His soul. That was what I had to make visible.”

By 1897, the sculpture had become less a statue than a symbol: a massive vertical gesture in which the figure’s form nearly dissolves into the rough drapery that enfolds it. The arms disappear entirely. The torso is a bulk of twisting cloth. Only the head—thrust upward, deeply scored with tension—emerges with clarity. It was not an image of Balzac writing or speaking. It was an image of Balzac becoming: the moment when thought becomes form.

What shocked Rodin’s contemporaries was not just the distortion—it was the daring metaphysics of the work. He was asking viewers to imagine the literary mind not as a static intellect, but as a body under pressure. A volcano of intention. In this, Rodin was decades ahead of his time. The Balzac anticipated the abstractions of Henry Moore and the expressionist deformations of German sculpture by a full generation.

The state recoils

When word of the sculpture’s shape leaked to the press in late 1897, panic spread through the Société des Gens de Lettres. Their vision of literary homage had been turned into something uncanny. Some compared it to a melting wax figure, others to a ghost in a shroud. The group delayed the official unveiling, hoping Rodin would make revisions. He refused. The plaster model was shown at the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in May 1898, but the controversy had already ignited.

Critics were merciless:

- “A disgrace to the memory of Balzac,” wrote the Journal des Débats.

- “A block of formless horror,” sneered Le Figaro.

- “Gargantuan,” “barbaric,” “blasphemous”—the adjectives came in torrents.

Some of the harshest criticism came from within literary circles. Writers who revered Balzac found Rodin’s vision perverse. It seemed to mock the clarity of Balzac’s prose, his civic commitment, his realism. But Rodin was doing something far more complex: he was sculpting not the novelist as citizen or stylist, but the condition of genius under internal pressure.

Rodin withdrew the sculpture after the Salon, refusing to compromise. He kept the plaster in his studio and never again submitted it for public commission. It was not cast in bronze until 1939—22 years after his death—by which time the art world had caught up to his intuition.

A silent, seismic shift

What makes the Balzac project of 1897 so extraordinary is not only its controversy, but its transitionary force. In a year when Paris was still preoccupied with the elegant curlicues of Art Nouveau, Rodin introduced a massive, lurching specter into the artistic imagination. It had no precedent. It resembled no ancient model. It fulfilled no civic function. It wasn’t even, strictly speaking, a statue. It was sculpture as will—a physical metaphor for internal vision. Rodin had pushed his medium past representation and into embodied symbolism.

This shift was not aesthetic alone. It struck at the nature of public art. Who was a monument for? What did it need to resemble? What if the highest respect one could offer the dead was to make them strange again, to resist domestication? Rodin’s Balzac made these questions impossible to ignore.

Rodin’s work also marked a turning point in his own practice. Up until this point, he had still played the game of commissions and recognition. After Balzac, something hardened. He no longer sought institutional approval. He deepened his private investigations into form, material, and myth, leading to later works that were rougher, more fragmented, more abstract.

Sculpting the invisible

In retrospect, the Balzac of 1897 resembles what we now call a breakthrough—but at the time, it nearly broke Rodin’s public standing. And yet, the decision to push forward, to model not what the eye saw but what the psyche endured, helped set the coordinates for 20th-century sculpture.

Rodin had intuited something deeply modern: that realism need not mean surface fidelity, and that inner life could be rendered in matter through rhythm, pressure, and density. The Balzac does not look like a man. It looks like a storm contained in human shape. Its folds are not clothing—they are seismic rings of force, the trace of something larger collapsing into form.

For this reason, it remains one of the most radical works completed in the 1890s. Not because of how it looked, but because of what it dared to do: to sculpt an idea as if it were alive.

Chapter 5: Empire and Ornament — Art Nouveau on the Rise

The building that bloomed

In 1897, visitors strolling through the 16th arrondissement of Paris began to notice something unsettling rising from the otherwise restrained, classical street façades. It was called the Castel Béranger, and it looked nothing like the apartment buildings that surrounded it. Designed by the young architect Hector Guimard, its swirling wrought-iron balconies, vegetal stone carvings, stained-glass flourishes, and asymmetrical towers exploded with a language that had no precedent in Haussmann’s grid. Here was a building that curved, that rustled, that breathed like something alive. For many Parisians, it was too much. But for others—critics, artists, and a new class of decorative collectors—it marked the birth of a new visual regime: Art Nouveau.

Although Castel Béranger would not be completed until 1898, its façade was already taking full form in 1897, and word had begun to circulate. Guimard’s design was the most architecturally ambitious realization to date of the movement named—somewhat dismissively—after Siegfried Bing’s Maison de l’Art Nouveau, the Paris gallery founded in 1895 that had started to exhibit curvilinear furniture, Japanese screens, ceramics, and symbolist paintings under one roof. By 1897, Art Nouveau was no longer merely a decorative taste; it was becoming a unified aesthetic worldview, one that challenged the hierarchical separation of fine and applied arts, and sought instead to collapse them into a single sensuous field.

Guimard’s building crystallized this ambition in stone and iron. Castel Béranger was not a house—it was an ornamental system, a theory of life in architectural form.

The politics of the curved line

At the heart of Art Nouveau’s early controversy was a question of values. What did it mean to abandon symmetry, order, and historical reference in favor of curling vines, tendrils, arabesques? What kind of society did such forms represent? To its supporters, Art Nouveau was the first truly modern style—not a revival, but an invention, adapted to the age of electricity, movement, and mechanized production. To its critics, it was decadent, unserious, even immoral.

The tension revealed something larger: Art Nouveau was not just a question of design. It was a cultural revolt against the weight of neoclassical authority, against the taste of the bourgeois patriarch, against the moral literalism of late 19th-century interiors. In that sense, Guimard’s Castel Béranger was more than an aesthetic provocation. It was a social argument, made in materials:

- Stone carved into vegetal forms, rejecting the rigid geometry of classical facades.

- Iron twisted like tendrils, implying growth, not stasis.

- Doors and staircases that seemed to melt, erasing the boundary between function and fantasy.

Guimard claimed inspiration from the Belgian architect Victor Horta, whose own Hôtel Tassel (1893–1894) in Brussels had pioneered similar organic lines. But whereas Horta’s interiors unfolded like arabesque gardens, Guimard brought the same logic to the streetscape—insisting that even public façades could express individuality, movement, desire.

In 1897, this was deeply disruptive. The Parisian street was supposed to be a space of shared codes—verticality, symmetry, legibility. Guimard replaced code with gesture. He treated architecture not as frame but as skin.

Bing’s gallery and the total work of art

While Guimard raised his iron vines into the sky, another figure was orchestrating Art Nouveau’s rise from the interior: Siegfried Bing, a German-born dealer whose Maison de l’Art Nouveau became the style’s namesake. Though opened in 1895, the gallery truly hit its stride by 1897, with influential exhibitions showcasing artists and designers from France, Britain, and Japan.

Bing’s genius lay in his understanding that objects could create atmosphere—that a lamp, a screen, a vase, a wallpaper sample, when arranged carefully, could form a mood as rich as any painting. His 1897 salon included works by:

- Émile Gallé, whose glass vases imitated forest lichens and aquatic forms.

- Henri van de Velde, who was beginning to merge Symbolist aesthetics with functional design.

- Japanese lacquerware and prints, which Bing had long collected and imported—subtly reshaping European taste in the process.

The gallery was not a museum. It was a stage for transformation—a place where bourgeois collectors could step into a total environment of undulating form, where even the ashtrays and banisters seemed to curve with organic will. In this, Bing helped articulate what would become a defining ambition of Art Nouveau: the Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art, in which the boundaries between disciplines would disappear, and every aspect of life could be enfolded in style.

By 1897, the gallery had drawn notice from across Europe. Young designers from Vienna to Glasgow visited to see the future. And what they saw was not just new furniture or ornament—it was a new relation between surface and soul.

Ornament and empire

The irony of Art Nouveau’s organic vocabulary was that it emerged at a moment of imperial consolidation. In 1897, France’s colonial empire was expanding in Indochina and Africa; Britain had just celebrated Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee; Belgium was entrenching itself in the Congo. Against this backdrop, Art Nouveau’s florid, sensuous, feminized forms might seem apolitical. But they were not.

Art Nouveau was, in part, a reaction against the aesthetics of empire—against the blocky militarism of Second Empire façades, against the triumphalist statuary that filled public squares. Its language was interior, not monumental; feminine, not martial; irregular, not imperial. And yet, it was also deeply entangled with empire, both materially and ideologically. Many of the raw materials—ivory, rare woods, pigments—came from colonial networks. And many of the motifs—lotuses, peacocks, serpents, bamboo—were drawn from exoticized visions of the East.

This tension gave Art Nouveau a peculiar double edge. It offered escape from industrial rationalism, but often did so by appropriating or aestheticizing the very world that empire had made available. The 1897 interiors of Bing’s gallery, like the organic filigree of Guimard’s balconies, relied on both a rejection of classical Europe and a fantasy of the non-European.

This is not to reduce Art Nouveau to hypocrisy. Rather, it is to understand how, in 1897, the movement’s sinuous lines carried complex currents: rebellion and nostalgia, eroticism and escapism, cosmopolitanism and control.

The revolt that wasn’t loud

What made Art Nouveau powerful in 1897 was not that it declared revolution. It slipped into the world. A curve in a staircase. A stained-glass panel. A pattern on a dress. Its subversion lay in subtlety—a quiet disobedience to geometry, hierarchy, and function.

Guimard’s Castel Béranger would go on to win the prize for the most beautiful façade in Paris the following year. But in 1897, it was still a scandal—a building that seemed to mock the rigid elegance of the Second Empire, to melt under its own aesthetic heat. Bing’s gallery, meanwhile, would help birth a generation of artists who saw no difference between a chair and a sculpture, between a jewelry box and a cathedral.

The world Art Nouveau wanted was not one of manifestos or machines. It was one where life could curve toward beauty—even if that curve had to fight every stone of the past to be drawn.

Chapter 6: An English Exit — Walter Crane’s Turn from the Royal Academy

The artist who chose the margins

By 1897, Walter Crane was no longer waiting for the Royal Academy’s approval. At age 52, he had spent three decades as one of Britain’s most influential illustrators, designers, and art theorists—yet the Academy had all but shut its doors to him. His paintings were rarely accepted, and when they were, they were hung with conspicuous indifference. Crane was not a dilettante, nor was he a failed academic. He had simply chosen another path: to put art in books, on walls, in furniture, in schools—and in service of politics. In an age when the Academy remained wedded to oil on canvas, Crane was painting with pigment and paper, with wallpaper blocks and socialist manifestos.

In 1897, Crane was between formal posts. He had just ended his role as Director of Design at the Manchester Municipal School of Art (1893–97) and had recently begun lecturing at Reading College, where he served as art director. His influence was not declining—it was expanding, but through alternative structures: schools, craft guilds, publications. He was preparing to become Principal of the Royal College of Art (a position he would assume in 1898), and yet he remained pointedly distant from the Academy’s orbit.

His career traced an arc that mirrored the ideological rift in late-Victorian art. On one side: the RA, upholding historical painting, moral allegory, and institutional prestige. On the other: Crane and his peers, advocating for a total aesthetic life, where design, illustration, ornament, and radical politics could coexist.

Art for the nursery, and for the barricades

Crane’s public reputation in 1897 still rested largely on his earlier triumphs in book illustration. His Toy Books, created for Edmund Evans in the 1870s and ’80s, had revolutionized children’s publishing with their luminous color printing, flattened decorative motifs, and lyrical figures. He made fairy tales feel both classical and strange. By the 1890s, his work adorned not only books but textiles, tapestries, wallpaper, and architectural panels.

Yet Crane was never content with commercial success. From the early 1880s, he became increasingly involved in socialist and workers’ movements, especially the newly founded Socialist League and the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society. He designed banners, pamphlets, and visual propaganda for labor demonstrations. His Cartoons for the Cause—a series of political illustrations—presented class struggle in the language of allegory and myth, with Britannia, Liberty, and chained workers occupying center stage.

This fusion of radical politics and ornamental art made Crane anathema to many in the establishment. The Royal Academy, rooted in empire and hierarchy, found his hybrid work—half design, half dream—impossible to classify. In 1897, Crane’s public exhibitions were not in Burlington House but in smaller Arts and Crafts exhibitions, civic halls, and progressive schools. His rejection of the RA was not petulant. It was philosophical.

Three of his key commitments had matured by 1897:

- Art must serve the whole of life, not only elite spaces or monumental canvases.

- Beauty was not a luxury but a necessity, especially in working-class homes.

- The artist should be an educator and citizen, not a sequestered genius.

These ideas, once marginal, were becoming visible in his educational work and publications, even as they remained invisible to the Academy.

Education as aesthetic reform

What set Crane apart from most of his contemporaries was not simply his decorative skill, but his structural ambitions. In Manchester and Reading, he worked not only to teach students how to draw but to reshape how art was taught. He believed British art education had been ruined by the dominance of mechanical copying and mindless ornament drills. Instead, he promoted:

- Nature-based design, rooted in observation and rhythm.

- Historical studies of Gothic, Byzantine, and Islamic motifs—not as mere pastiche, but as vital sources of living design.

- Integration of design disciplines, from textile to metalwork to book illustration.

In 1897, he wrote: “The only way forward is to abandon the false hierarchy of arts. There is no ‘fine’ art without useful art, and no useful art that should not be beautiful.”

This credo would guide his upcoming leadership at the Royal College of Art, where he would briefly attempt to realign its mission with the principles of the Arts and Crafts movement. Though his tenure there would be short and contentious, the seeds were being planted in 1897—in classrooms, lectures, and reformist circles far from the RA’s salons.

England’s aesthetic schism

Crane’s rejection by the Royal Academy was not an isolated incident. The 1890s saw the widening of a cultural fault line that had been simmering since the Pre-Raphaelites. On one side stood the academic painters, clinging to biblical scenes, empire mythologies, and the great genre tableaux. On the other stood designers, illustrators, and decorative artists—those like Crane, William Morris, and Charles Ricketts—who saw art as a living, daily experience.

The Academy had never known what to do with decorative artists. Illustration was viewed as secondary. Design was useful, but not elevated. Crane refused this ranking. In fact, he inverted it. To him, the domestic plate, the school wall, and the printed page had more democratic power than any gilded painting.

1897 was a year of tension but also opportunity. New publications such as The Studio had begun to treat design with the seriousness once reserved for oil painting. Schools were slowly embracing craft as a subject of study. And exhibitions like the Arts and Crafts shows brought textiles and ceramics into public view not as curiosities but as statements of social philosophy.

Crane was not alone. But he was among the clearest voices of this movement. And his marginalization by the Academy only confirmed what he already believed: that real aesthetic transformation would not come from the center. It would grow, like ornament, from the edges.

The future would be decorative

Looking back, 1897 marked the moment when Crane’s exit from the Academy was no longer provisional—it was complete. He would not try again to exhibit there. He had chosen another forum, another battlefield: education, print, and public life. His tools were color woodcuts, illustrated manifestos, and applied design. And he wielded them not as compromises, but as weapons.

His belief that the decorative arts could shape the moral character of society was not quaint idealism. It was, in a way, prophetic. The next century would be dominated not by academies but by the very forms he had championed: graphic design, typography, book arts, propaganda posters, and public murals. Crane had seen early what the Academy refused to acknowledge: that the art of the future would be reproducible, mobile, political—and ornamental.

Chapter 7: The Mirror and the Mask — Whistler’s Final London Works

The tone that outlived the man

By 1897, James Abbott McNeill Whistler occupied a paradoxical position in the British art world: as distant from the Royal Academy as ever, yet casting a longer shadow over modern aesthetic thought than most who had passed through its doors. Nearing the end of his life, his energies no longer centered on invention but on refinement—deepening a visual language he had been crafting for decades. He painted little in this period, and yet his presence in London remained unmistakable. Few artists had done more to alter the perception of what painting could be—tonal, suggestive, indifferent to narrative—and few had done so at greater personal cost.

Whistler had never been a painter of statements in the conventional sense. He preferred murmurs to proclamations, atmospheric subtlety to drama. But by the late 1890s, that subtlety had hardened into a defiant philosophy. His belief in art as autonomous, poetic, and formally complete—expressed most famously in his essays and in The Gentle Art of Making Enemies—had become doctrine among a younger generation of painters. Even as he faded from active exhibition in London, his fingerprints remained everywhere: in the quiet tonalism of English portraiture, in the rise of aesthetic interiors, and in the conceptual shift from subject to sensation.

Aesthetic philosophy at full tilt

Whistler’s core belief—that art need not justify itself with moral or narrative content—had crystallized long before 1897, but it was in these later years that its influence reached full bloom. He no longer needed to argue. His work had already made the case. From his nocturnes of the 1870s to his portraiture of the 1880s, Whistler had demonstrated that a painting’s strength lay not in what it depicted, but in how it was composed. Color, line, and balance were not tools in the service of storytelling. They were the story.

This aesthetic autonomy found its most refined expressions in his portraits of the 1890s. Mother of Pearl and Silver: The Andalusian, begun in 1888 and completed over a stretch of years into the early 20th century, shows a young woman rendered in tonal harmonies so restrained they verge on musical abstraction. Black, silver, and faint echoes of ivory glide across the canvas like motifs in a nocturne. The figure is poised, but not psychologically defined. She is a presence, not a character.

Whistler had long understood that portraiture could be as abstract as landscape. In his hands, the genre became an arena for balance, control, and atmospheric precision. By 1897, the clarity of this intention was beyond dispute. His critics no longer accused him of incompleteness—they had learned that what looked unfinished was often perfectly composed.

The painter of twilight and reflection

Whistler’s London subjects had always revolved around water, fog, and the fading light of day. The Thames was his recurring motif, less a river than a medium of dissolution. His Nocturnes, painted in earlier decades, still defined the atmosphere of his mature reputation. They were unlike anything else in English painting: shadowy, restrained, disinterested in incident. Bridges dissolved into mist; fireworks melted into sky. These works anticipated the abstraction to come not through distortion, but through evanescence.

In the 1890s, though no new masterpieces emerged from the river’s edge, the spirit of the Nocturnes lingered in his etchings and lithographs. His late prints were suffused with the same gentle vanishing act—lines softening into gesture, forms receding into space. In these images, the city itself became a kind of music: tonal, repetitive, haunting. Whistler’s London was not industrial or imperial. It was veiled. It was reflective.

He once described his work as “an arrangement in grey and gold.” That phrase, deceptively modest, contained his entire worldview. The artist was not a translator of scenes, but a composer of visual music. By 1897, this view had filtered into the fabric of the city’s artistic consciousness. The boldness of his restraint had become its own school.

The performance of refinement

Whistler’s life in the late 1890s was marked not by major exhibitions, but by a kind of cultivated presence. He was a performer of aesthetic identity: monocle, silver cane, silk cravat—his personal style was a mirror of his work. It was all surface, and all meaning. By 1897, he was no longer merely an artist. He was a symbol of a movement that refused the moral demands of Victorian taste.

He also became, in these final London years, a man of increasing solitude. His beloved wife, Beatrix, had died in 1896, and the loss cast a long shadow over his private life. His circle contracted. He remained admired, but less frequently seen. There were no public scandals, no libel trials, no courtroom theatrics. Just a slow fade into the very kind of twilight he had always painted.

Yet his influence deepened. Young artists in Britain and France had begun to absorb his lessons: the power of the cropped composition, the emotional resonance of muted tone, the dignity of suggestion over assertion. Even the avant-garde, which would soon move into the electric boldness of Fauvism and abstraction, owed something to Whistler’s quiet dismantling of narrative.

The mirror and the mask

To walk through Whistler’s final London works is to encounter a world of restraint, harmony, and near-silence. These were not paintings of statement or conviction. They were masks—crafted not to conceal, but to transfigure. And like all great masks, they offered reflection. What they reflected was not Victorian London as it appeared in daylight, but the world as it might exist in half-light: slowed, shadowed, balanced.

In 1897, that approach no longer needed to be explained. It had, by then, shaped the sensibility of an era. Whistler was not out of fashion. He had become a weather system—the soft climate of taste against which other artists worked, even when they claimed to rebel.

Chapter 8: Collecting the Exotic — The Musée Guimet and Orientalist Fantasies

A museum of silence and gold

In 1897, tucked into a quiet Parisian neighborhood just off Place d’Iéna, the Musée Guimet stood like a portal into an imagined East. Its halls glowed with gilt Buddhas, carved Bodhisattvas, tantric scrolls, Khmer bronzes, celadon ceramics, and sacred textiles whose iconography few Parisians could read. The museum, established in its current location just eight years earlier, was already becoming one of Europe’s most significant repositories of Asian religious art. For many in the capital, this was their first sustained encounter with visual cultures from India, China, Japan, Cambodia, and Tibet—not through travelers’ tales or romantic novels, but as physical presences, sculpted and glazed, lit by gaslight and arranged in vitrines like reliquaries.

Émile Guimet had built this world. The wealthy industrialist-turned-collector had traveled extensively through Asia in the 1870s and 1880s, with an appetite not merely for objects but for systems. He sought to map belief through image, to gather and display the visual expressions of Buddhism, Hinduism, Confucianism, and Shinto as if assembling a taxonomy of the sacred. His project was both spiritual and imperial—a vision of human religion rendered legible through French curation.

By 1897, the Musée Guimet was less a curiosity than a stage-set of the exotic, curated not for anthropological accuracy but for aesthetic rapture. The artworks it held were real, but the contexts in which they were placed—mute, reverent, and abstracted—turned living traditions into decorative mysteries. It was a museum of marvels, but also of misunderstandings.

The surface of reverence

Walking through the Musée Guimet in the late 1890s was a visual seduction. The architecture was neoclassical, but the interiors hummed with incense and lacquer. Glass cases held painted scrolls of wrathful deities alongside serene Amitabhas. Japanese incense burners sat beside Tibetan ritual daggers, their juxtaposition suggesting continuity where none existed. The museum collapsed centuries, geographies, and doctrinal distinctions into a single aesthetic atmosphere.

And that atmosphere was the point. Guimet did not imagine the museum as a didactic tool. He imagined it as a space of contemplation, a shrine for the French public’s awakening to “the East.” What this awakening entailed, however, was not knowledge but fantasy.

The aesthetics of the Musée Guimet in 1897 reflected three broader cultural movements in Paris:

- An intense public fascination with Japanese prints and applied design, especially among Symbolist artists and Art Nouveau decorators.

- A growing appetite for spiritual alternatives to Catholicism, often filtered through Orientalist reinterpretations of Buddhism and Hindu mysticism.

- The integration of “exotic” motifs into domestic interiors, especially among bourgeois collectors seeking to signal taste and cosmopolitanism.

In this sense, the museum’s presentation of Asian art fed directly into the European decorative imagination, offering images stripped of their cultural moorings, ready to be reinterpreted as pattern, symbol, or inspiration.

Buddhism by gaslight

The Musée Guimet was not the only institution in Europe displaying non-Western art in 1897, but it was unique in its focus on religion. Unlike the British Museum or the Louvre’s antiquities galleries, Guimet’s mission was to show the spiritual architecture of Asia. But the experience of walking through his halls was closer to a Wagnerian opera than a theological study. Light was low. Labels were sparse. The effect was not educational—it was theatrical.

This theatricality echoed broader currents in fin-de-siècle Paris, where exoticism and symbolism had become intertwined. Writers like Pierre Loti and painters like Gustave Moreau drew heavily from imagined Eastern sources. But in the Guimet, the line between symbol and object blurred. A Nepalese thangka might hang near a Japanese sutra scroll, both surrounded by Chinese ritual bronzes—severed from context, unified only by aura.

That aura, however, was not neutral. It was shaped by colonial asymmetry. Many of the objects had entered France through informal channels: purchased, traded, donated by diplomats, or acquired through missions. The museum’s tone was one of awe, not conquest. But the fact that these sacred objects now stood in vitrines on Parisian marble floors told a quieter story of possession.

Guimet himself believed he was preserving these traditions, even honoring them. But what the museum offered was not dialogue. It was curated silence—a space in which the East could be admired, but not heard.

Inspiration without understanding

Despite this flattening of culture, the Musée Guimet in 1897 became a touchstone for artists seeking to break from classical norms. The Symbolists, in particular, found in Asian religious imagery a vocabulary of the ineffable. For painters like Odilon Redon, Japanese and Indian art offered a way to depict states of mind rather than narrative. For designers aligned with Art Nouveau, the museum’s scrolls and ceramics provided a library of lines—organic, non-representational, and fluid.

The influence was not scholarly—it was formal. European artists did not study these works in depth. They absorbed them, mimetically, aesthetically, instinctively. And what they took were patterns:

- Lotus blossoms rendered as decorative borders.

- Bodhisattva poses adapted into theatrical gestures.

- Cloud motifs and flame haloes transformed into poster art or wallpaper design.

In this way, the Musée Guimet’s collection seeped into the bloodstream of Western modernism—not as source material, but as a set of optical triggers, capable of evoking something ancient, distant, and charged with symbolic power.

It is important to acknowledge that the museum’s approach, while shaped by admiration, also neutralized the cultural meanings of its holdings. A tantric diagram was displayed not as a ritual tool, but as a design. A Buddhist reliquary was admired for its symmetry. The sacred was not desecrated, but it was recast as aesthetic material, made available to European desire.

The longing behind the glass

By 1897, the Musée Guimet had become more than a museum. It was a mirror, reflecting back to Paris its own anxieties and aspirations. In an age of industrial expansion and spiritual doubt, the idea of the East—as serene, mystical, timeless—offered both escape and reassurance. The museum’s displays did not confront visitors with real cultural difference. They enfolded them in ornamented longing, giving form to a dream of otherness that confirmed Europe’s aesthetic centrality even as it claimed to celebrate foreign art.

Yet within that dream, something real did circulate. Some visitors were moved. Some artists were transformed. And some of the objects themselves—quiet, intricate, resilient—spoke in ways the vitrines could not silence.

Chapter 9: America’s Gilded Imagination — Sargent and the Society Portrait

The silk, the glare, the hush

In 1897, John Singer Sargent was not merely painting portraits—he was staging social myths. Across the drawing rooms of London and the salons of New York, his name circulated like that of a fashionable couturier, someone who could take a family’s image, cinch it in satin, light it with charm, and freeze it forever on canvas. His portraits were not likenesses alone. They were acts of cultural calibration: rich in surface, unnervingly precise in psychology, and imbued with the gloss of wealth made natural.

That year, Sargent completed a series of paintings that confirmed his role as the preeminent interpreter of the Belle Époque elite. Chief among them was Mr. and Mrs. I. N. Phelps Stokes, a double portrait of a young American couple recently married. The husband, meant to be the focus, appears casual, even ghostlike in a dark background. The wife—armed with gloves, swagger, and a loose white blouse—commands the frame. Her gaze is not demure; it’s assertive. Sargent had shifted the balance, made the woman the subject, the man an afterthought. It was not a provocation. It was instinct.

By 1897, Sargent was working at full power. He had turned society painting into a kind of theater, and his sitters trusted him not just to record their features, but to shape their legacy. The stakes were high. These were families building fortunes, reputations, dynasties. Sargent’s canvas was a mirror—but a flattering one, edged with tension.

Americans abroad, aristocrats at home

Sargent was born in Florence to American parents, trained in Paris, and lived much of his professional life in London. This geographic fluidity gave him a unique vantage point in 1897. He was American enough to charm the brash transatlantic elite; European enough to understand the codes of Old World refinement. His portraits captured this tension—the desire to be seen as noble without appearing to try.

In Mrs. George Swinton (painted in 1897), he rendered the Scottish aristocrat in a haze of luxurious fabrics: pleated tulle, lavender silk, trailing ribbons. Her expression is poised but unfixed—somewhere between thought and performance. The background is soft, abstracted, like a dream just beginning to take shape. Sargent’s brush seemed less interested in details than in temperament, in the fleeting choreography of charm.

These portraits were never moral. They were aesthetic documents of self-presentation. He painted a world where lineage was less important than style, where pose became character, and where appearance—when handled with subtlety—became a form of authorship. And yet, even amid this polish, something more complex was always at play.

Three signature devices recur in Sargent’s 1897 portraits:

- The off-center composition, subtly unbalancing the viewer and suggesting spontaneity.

- A deep engagement with fabric and texture, where clothing becomes its own expressive field.

- Eyes that refuse to resolve—never quite looking at the viewer, never quite away.

These elements created what critics later called a “painterly unease”—a refinement bordering on discomfort.

The glamour of surface, the gravity beneath

Sargent’s most famous portraits shimmer, but they rarely dazzle. Their power lies not in ornament, but in an almost forensic attentiveness to how people perform identity. The paintings from 1897 show this with special clarity. In Mr. and Mrs. I. N. Phelps Stokes, for example, the husband appears casual—jacket off, hands tucked—while his wife takes on the visual burden of representation. She wears the gaze of someone fully aware that this image will endure.

Even earlier works—such as Mrs. Carl Meyer and Her Children, exhibited to great attention at the Royal Academy in 1897—linger with double meanings. At first glance, it is a charming society portrait: the mother poised, the children relaxed. But a closer look reveals something uncanny. The daughter’s eyes drift toward the viewer, slightly askew. The mother’s hands rest with faint rigidity. The backdrop—sumptuous, theatrical—feels more like a stage set than a home. These people are posing for history, and they know it.

In painting after painting, Sargent managed to suggest the gap between how people wished to be seen and how they were. That gap is not a criticism. It is where his art lived.

Empire’s elegance, democracy’s glare

Sargent’s 1897 clientele included both the old nobility and the new plutocracy. In England, he painted titled ladies and established figures. In America, he turned his eye on industrial fortunes and social climbers. But he treated them all with equal intensity—and equal scrutiny. His portraits did not flatter indiscriminately. They often revealed the performative strain of power.

For many of his American clients, especially those recently risen into wealth, the act of commissioning a Sargent portrait was itself a social credential. He became not merely a painter but a cultural intermediary, helping them translate their economic status into visual legitimacy. Yet his portraits always retained a hint of coolness, a suggestion that beauty alone could not mask complexity.

This made Sargent a unique chronicler of his age. He did not moralize. He did not mythologize. But he painted his world with a psychological fidelity that was rare among society artists. His brush lingered on the seams, the glances, the shadows beneath the surface.

The portrait as modern theater

In retrospect, 1897 marks a moment of peak fluency in Sargent’s career. He was no longer searching for his voice. He had it. And his clients—across England, France, and the United States—were willing to pay dearly for it.

But what they bought was not flattery. It was a vision of themselves as they might wish to be remembered: poised, compelling, elevated. And what Sargent gave them was something richer: a suspended image of personality in flux, half formal, half human.

His portraits from this year hold us not because they are beautiful, but because they are performances caught mid-breath. The glamour remains, but so does the question: who is the real subject—the person, or the image they helped construct?

Chapter 10: The Printed Revolution — Pan, The Studio, and the Rise of the Art Journal

When the gallery became paper

In 1897, art began to slip out of the frame and into the printed page. Across Europe, a new generation of illustrated journals—lavishly produced, international in scope, and unapologetically aesthetic—was transforming how art was circulated, discussed, and consumed. No longer confined to galleries or salons, visual culture now arrived monthly by post, folded into embossed covers, interleaved with tissue, and soaked in ink. These journals did not merely report on art—they curated it, composed it, and reimagined it as a total experience of print.

Two magazines stood at the center of this quiet revolution. In Berlin, Pan, founded in 1895 but entering a particularly ambitious phase by 1897, set out to unite the arts under a single editorial vision: literature, painting, music, architecture, and design presented as facets of the same cultural project. In London, The Studio, established in 1893, had by 1897 become the most influential art magazine in the English-speaking world, shaping taste from Glasgow to Boston. Their shared ethos was modernity—but not in the sense of shock or rupture. Rather, they offered a new aesthetic ecology, in which artists, writers, and craftsmen were equals, and the journal itself was a kind of exhibition space.

The rise of the art journal did more than democratize access. It subtly restructured the entire system of artistic prestige.

Pan: an object of desire

By 1897, Pan had become the jewel of German avant-garde publishing. Printed on thick paper, often with original engravings tipped in, the magazine elevated graphic design to the level of fine art. Its contributors ranged from Symbolist poets and Secessionist painters to radical essayists and typographers. The pages were not busy. They were deliberate, elegant, and often cryptic—each spread arranged like a miniature exhibition.

What made Pan revolutionary was not simply its content, but its attitude toward art as experience. It treated layout, type, and illustration as co-equal parts of an aesthetic event. Reproductions of paintings appeared not as documentation, but as reinterpretations—flattened, stylized, absorbed into the design logic of the page.

The magazine’s editorial philosophy fused three core elements:

- A commitment to Gesamtkunstwerk, the total work of art that unified text and image.

- An internationalism that embraced British, Belgian, French, and Scandinavian contributors.

- A refusal of commercial populism, even at the cost of financial success.

In this, Pan differed radically from its contemporaries. It did not sell taste—it constructed it, slowly, insistently, with the quiet authority of the beautifully made.

The Studio: commerce meets craft

In contrast to Pan’s elite restraint, The Studio embraced a more populist modernism. Its pages in 1897 featured everything from Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s furniture to Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations, from stained glass to photography. Founded by Charles Holme, an industrialist with close ties to the Arts and Crafts movement, the magazine married progressive aesthetics with commercial viability.

The Studio was not afraid of clarity. Its articles were informative, its captions precise, and its photographs often documentary in nature. Yet it maintained a strong editorial line: beauty must be useful, and usefulness must be beautiful. The decorative arts were no longer to be seen as secondary. The magazine treated an artist’s bookplate with the same seriousness as a bronze sculpture or a mural.

In 1897, this philosophy was gaining traction. The magazine’s reach extended across the Atlantic, influencing the taste of American collectors and craftsmen. It helped launch movements, publicize exhibitions, and introduce obscure artists to broader audiences. Most significantly, it modeled a new kind of artistic identity—not the lonely genius, but the designer as cultural synthesizer, someone who could move between media with fluency.

The Studio helped make it respectable, even aspirational, to be a graphic artist, a textile designer, a ceramicist. It gave form to the belief that print could be a kind of architecture, shaping the visual environment of the middle class.

The quiet networks of modernism

What united Pan and The Studio, despite their differences, was a shared sense that art needed new infrastructure. The old institutions—the academies, the salons, the national museums—were too slow, too narrow, too hierarchical. The art journal, by contrast, was flexible, international, and open to experiment. It could publish a manifesto, a sketch, a full-page lithograph, and a treatise on color theory all within the same issue.

These journals created networks of influence long before the internet, linking Berlin to London, Vienna to Boston, Paris to Tokyo. Artists began to think not in terms of local schools, but of transnational conversations. A Belgian illustrator might find his work praised in an English journal. A Japanese woodblock print might appear alongside an essay on Symbolist poetry. This was not appropriation in the crude sense. It was cross-pollination, curated and edited with care.

By 1897, these networks were beginning to shape the broader direction of modern art. The dissemination of new styles, new forms, and new attitudes happened not primarily through galleries, but through print. Artists read one another. Ideas moved as images. And the magazine became a laboratory of form, where the future could be prototyped monthly.

The page as artwork

The significance of 1897 lies not in a single issue or feature, but in a larger shift. Art was no longer something only to be hung. It was something to be printed, read, touched, mailed. The magazine was not a surrogate for the gallery—it was a new kind of gallery, one that could travel across borders, fold into hands, and rest on nightstands.

Both Pan and The Studio understood this. They treated layout as composition, typography as visual rhythm, paper as surface. Their editors were curators; their printers were collaborators. Each issue was a work of orchestration, and the reader became a participant in the modern aesthetic project.

This print culture changed the way artists thought about audience. The collector was no longer just the wealthy patron. It was the reader, the amateur, the student. The future of art, it seemed, might lie not in grand commissions, but in the quiet intimacy of images shared by page and post.

Chapter 11: The Architecture of Influence — Studios, Schools, and the New Art Education

Where the brush began

In 1897, much of what we now call “modern art” was still in the hands of students. But those students were no longer learning in the shadow of a single canon. The old academies still stood—proud, marble-lined, weighted with history—but they no longer held the monopoly on what it meant to be an artist. Something had shifted. Across Europe, and to a lesser extent in America, new forms of instruction were emerging: private ateliers, design-focused institutes, cross-disciplinary studios. These institutions didn’t just teach technique. They shaped sensibility.

The change was quiet but profound. Where the École des Beaux-Arts had once offered a nearly unquestioned standard—classical drawing, history painting, anatomical precision—by 1897, alternatives had matured into rivals. Students now traveled to Munich or Paris not just to emulate the past, but to participate in a growing international network of aesthetic experimentation. Art education was no longer singular. It was plural. It was architectural not only in metaphor, but in method: a new structure for making meaning.

This chapter maps that shift—through schools, through spaces, and through a rethinking of what artistic formation could be.

The end of the academic citadel

The classical art academy had once offered artists the surest route to recognition, patronage, and state commissions. Its ideals—drawing from antique casts, narrative allegory, heroic scale—had dominated Western painting for generations. But by the 1890s, even within these bastions, cracks were beginning to show. Professors lamented students’ loss of discipline. Students bristled under inflexible hierarchies. The rise of independent salons and alternative exhibitions began to undercut the Academy’s grip on public taste.

Nowhere was this tension more visible than in Munich. The Academy of Fine Arts there had, since the mid-19th century, offered a rigorous education based on drawing, anatomy, and historical style. Yet just blocks away, Anton Ažbe’s private art school attracted a different breed of student—international, restless, and modern. Ažbe, a Slovenian painter with a taste for abstraction and a gift for pedagogy, taught not by correcting students into conformity, but by encouraging form as emotion, line as intuition. He drew pupils from the Russian Empire, Scandinavia, the Balkans—many of whom would later play pivotal roles in modernist movements.

Ažbe’s method, centered on the “sphere principle” and intense tonal modeling, seemed arcane to outsiders. But to his students, it was liberating. What they found in his studio was not a school, but a laboratory, where painting was less about rules and more about inquiry.

The atelier as incubator

In Paris, meanwhile, the Académie Julian had become the most prominent alternative to the École des Beaux-Arts. Founded in 1868 by Rodolphe Julian, the school admitted foreign students, encouraged private instruction, and maintained a competitive but less doctrinaire atmosphere than its state-run counterpart. By 1897, its hallways echoed with multiple languages, and its classrooms were filled with future luminaries—from Symbolist painters to future abstractionists.

Julian’s school was not a retreat from tradition, but a reframing of it. Students still drew from the model, still copied Old Masters. But they were not expected to conform to a single state-sanctioned style. This latitude helped loosen the grip of academic dogma and seeded the ground for later innovation.

What these ateliers offered—whether in Paris, Munich, or elsewhere—was not simply skill. They offered community, feedback, and exposure to ideas that could not be found in the official salons. More than technique, they taught navigation: how to build a career, how to interpret criticism, how to remain visible without compromising vision.

Glasgow and the blueprint for design

Far from the continent, in a misted corner of Scotland, another educational revolution was underway. The Glasgow School of Art, under the leadership of Francis Newbery, had begun a transformation in the 1890s that reached a visible milestone in 1897: the commissioning of a new school building on Renfrew Street, designed by the young and still-unproven Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

The commission itself was radical. Mackintosh’s designs departed entirely from neoclassical norms. He envisioned an architecture of clean lines, asymmetrical forms, and a synthesis of function and ornament. It would take years to complete, but even in 1897 the gesture was clear: art education needed new rooms, new walls, new geometries.

The Glasgow School of Art didn’t merely teach painting or sculpture. It fostered a philosophy of integration, where design, craft, and fine art stood on equal footing. This was not the old hierarchy of painting above applied arts. It was a revolt against verticality, a flattening of distinction that mirrored the ethos of the Arts and Crafts movement.

This flattening had global implications. Students who passed through Glasgow—or even read about it through journals like The Studio—began to think of art not just as individual expression, but as environment, context, structure. The school became a model not just for teaching design, but for living it.

From apprenticeship to atmosphere

What united the best of these institutions in 1897 was their growing sense that education was not simply about transmission—it was about immersion. The atelier became less of a classroom and more of an aesthetic atmosphere. Artists were not simply taught how to hold a brush or mix color. They were taught how to see, how to position themselves, how to interpret tradition without becoming imprisoned by it.

This was the final break with the medieval idea of apprenticeship. In the past, to become a painter was to serve under a master, to imitate, to execute. By the end of the 19th century, it had become something else: a search for voice, a journey through forms, a negotiation with history.

This pedagogical shift helped make modernism possible. It gave artists room to fail, to hybridize, to combine graphic design with oil painting, to read Nietzsche on a studio break, to take influence from Japanese prints or Gothic cathedrals without asking permission.

It also created a new kind of artist—not the artisan, not the academic, but the aesthetic thinker, capable of moving between disciplines, styles, and schools. The studio was no longer a place to copy. It was a place to build worlds.

Chapter 12: The Shape of 1900 — What 1897 Set in Motion

The whisper before the fanfare

Standing at the threshold of the 20th century, the year 1900 loomed like a triumphal arch: vast, glittering, and overdetermined. Paris prepared for the Exposition Universelle, a celebration of technology and progress that would draw millions. Art Nouveau was reaching its ornamental peak. Theatres, galleries, and pavilions were being raised with feverish speed. But to understand what made 1900 possible—not just as an event, but as an aesthetic moment—it’s necessary to return to the quieter ground of 1897. That was the year the foundations were laid. Not with declarations, but with decisions: to leave academies, to build new institutions, to print differently, to sculpt for the mind rather than the eye.

What 1897 provided was not a single aesthetic doctrine. It provided infrastructure: movements coalesced, publications matured, buildings were planned, studios reoriented. The year was a hinge—not dramatic in its rupture, but pivotal in its coordination. It gathered strands that would unfurl fully in the decade to come.

The Secession opens the door

Nowhere was this more structurally clear than in Vienna. The Vienna Secession, founded in 1897, had no exhibition hall when it launched. But by 1898, Joseph Maria Olbrich’s Secession Building had opened, capped by its unmistakable golden dome. The group’s motto—“To every age its art, to every art its freedom”—now glimmered above the entrance in gold leaf. And with it came a new kind of exhibition culture. Art was no longer simply shown—it was installed, curated, staged.

This was more than architecture. It was a redefinition of how art met its public. The building’s inaugural exhibition didn’t merely hang paintings; it created an environment, one that integrated murals, furniture, typography, and spatial design. This was the ethos seeded in 1897: art as total experience. And by 1900, it had become a principle that extended beyond Vienna into Munich, Brussels, Glasgow, and Paris.

The transition was not stylistic. It was institutional. Artists were no longer asking to be included in state exhibitions. They were creating their own.

Paris prepares its stage

As Vienna built its Secession house, Paris was preparing for its own theatrical assertion: the Exposition Universelle of 1900. The fair was to be a vast celebration of empire, science, and modern life, with pavilions dedicated to art, industry, and colonial exhibition. Yet many of the visual languages that would dominate its aesthetic had matured not in 1900, but three years prior.