The story of Osaka’s art begins long before the city bore that name, in a landscape of tidal flats, river mouths, and wooded hills where early communities left traces of their daily lives and spiritual imaginations. Long before the theaters of Dōtonbori or the merchant townhouses of the Edo period, Osaka’s terrain fostered a sequence of artistic expressions—from clay vessels to monumental burial mounds—that reveal how deeply the area’s people sought to give form to memory, ritual, and social order.

Jōmon traces along rivers and bays

Archaeological finds in the Osaka basin suggest settlement during the Jōmon period, when hunter-fisher-gatherer communities thrived by exploiting the bounty of the Inland Sea. The clay figurines and cord-patterned pots they fashioned were more than tools; they carried ritual significance, embodying fertility and continuity. Fragments unearthed near riverbanks such as the Yodo hint at gatherings where pottery was fired, food was stored, and ceremonies marked the rhythms of life.

Unlike the robust sculptural forms found in the Tōhoku region, Osaka’s Jōmon remains are modest in number and scale. This difference itself is telling. The art of the region grew not in splendid isolation but at the crossroads of exchange, where movement and trade may have encouraged more portable, functional expressions. Even so, the cord-marked jars, with their rhythmic impressions pressed into wet clay, hold a beauty that bridges necessity and imagination. Each fragment speaks of hands shaping earth into something both durable and symbolic.

Yayoi rice cultivation and ritual vessels

By the Yayoi period, the Osaka plain had become a fertile cradle for wet-rice agriculture. This transformation altered not only diets and settlements but also artistic forms. Sleek, wheel-made pottery replaced the thick-walled Jōmon vessels. The glossy reddish-brown jars and finely balanced stemmed dishes of Yayoi potters suggest an aesthetic of order and restraint. Where the Jōmon favored surface decoration, the Yayoi emphasized proportion and clarity.

Perhaps the most striking artifacts are the bronze dōtaku bells, some discovered in the Osaka region. These tall, elegantly cast objects—embellished with geometric patterns and occasional figurative scenes—were never rung in practical use. Instead, they seem to have served as ceremonial markers, buried together in groups, their presence reinforcing agricultural ritual and communal identity. The sophistication of their casting shows Osaka’s early integration into continental technologies, as metallurgy likely entered Japan through coastal exchanges that passed through this region.

There is an unexpected intimacy in these bronzes. Though monumental in form, their patterns often depict scenes of hunting, rice planting, or daily labor, suggesting that the most ordinary acts could be transfigured into sacred images. In this balance between the communal and the transcendent, one can glimpse the beginnings of Osaka’s later art traditions, where performance and daily commerce would become stages for imagination.

Kofun burial mounds as monumental art

If Jōmon ceramics and Yayoi bells represented small-scale ritual, the Kofun period gave Osaka one of the largest forms of art in all of Japan: the keyhole-shaped burial mounds that still dominate the landscape of Sakai. The colossal Daisen Kofun, attributed to Emperor Nintoku, stretches nearly 500 meters in length—so vast that it can only be truly perceived from the air. It is a work of landscape architecture, earth-sculpture, and ritual space combined, making the Osaka plain itself into an artwork of political and spiritual assertion.

Around these mounds stood haniwa—terracotta figures of warriors, animals, houses, and dancers. Their stark cylindrical bases topped with stylized forms created a ring of silent guardians, part sculpture, part offering. Though their features are abstract, the gestures of these clay figures—hands raised, armor detailed, horses bridled—convey both liveliness and solemnity. They functioned not only as ritual markers but also as early narrative art, giving material shape to the society’s self-image.

Three details stand out in this monumental tradition:

- The scale of the kofun required coordination on a level that made the burial mound itself a statement of power.

- The variety of haniwa forms reflected a society attentive to both martial and domestic life.

- The placement of these figures created an immersive environment, an early example of art designed to be experienced in space rather than as a single object.

To walk near these mounds today is to feel both the grandeur and strangeness of an art form that dwarfs the viewer. Unlike a painting or vessel, the kofun cannot be taken in at once; they assert themselves as geography, reminding us that the earliest Osaka art was inseparable from land, ritual, and authority.

reflection

In the prehistoric and protohistoric arts of Osaka—from cord-marked pottery to bronze bells to vast earthen tombs—there emerges a pattern of art tied to community, ritual, and the assertion of identity. This is not art for individual pleasure or private display but for collective memory, binding the living and the dead, the earthly and the divine. The Osaka plain became a stage for human creativity long before it became a city. These first expressions set the rhythm for what followed: art in Osaka would always carry a public, performative quality, bound up with exchange, ritual, and the shaping of shared space.

Buddhism Arrives: Shitennō-ji and Early Temples

When Buddhism reached Japan in the 6th century, Osaka was one of the first landscapes to absorb its imagery, architecture, and rituals. The port city of Naniwa—future Osaka—stood at the maritime crossroads where continental culture arrived by ship. Stone Buddhas, bronze reliquaries, silk banners, and monks themselves disembarked here before making their way inland. This made Osaka a spiritual gateway as well as a commercial one, and its early temples remain some of the most significant markers of Japan’s transition from prehistoric ritual to organized, monumental religion.

Prince Shōtoku’s vision and architecture

The founding of Shitennō-ji in AD 593, attributed to Prince Shōtoku, marked a decisive moment. Not only was it one of the earliest Buddhist temples in Japan, it also introduced a new language of architecture: the pagoda, the golden hall, the lecture hall, and the gates all laid out in a rectilinear pattern. For a society still echoing with the memory of kofun tombs, this symmetry was striking. It imposed order upon the sacred, transforming ritual space into a geometry of devotion.

Unlike the burial mounds that rose out of the earth like mountains, Shitennō-ji announced a vertical aspiration: its pagoda reaching upward, its hallways enclosing space in deliberate balance. Here, religion became something to be entered and inhabited rather than skirted and revered from a distance. That shift itself was a kind of artistic revolution.

The temple also embodied Shōtoku’s vision of Buddhism as a political and cultural stabilizer. Its name—dedicated to the “Four Heavenly Kings”—signaled guardianship over the state. The art housed within it, from statues of bodhisattvas to paintings of celestial figures, presented a fusion of spiritual imagery and state authority, giving Osaka its first monumental artworks on par with those of the capital.

Imported techniques from the continent

Much of Shitennō-ji’s early splendor, and that of other temples in the Osaka area, was indebted to continental models. Craftsmen from the Korean peninsula brought with them methods of wood joinery, bronze casting, and mural painting. The roof tiles found in early Osaka temples bear motifs of lotus blossoms and cloud-scrolls that echo Chinese Han and Six Dynasties precedents. These decorative details were not merely ornamental—they signaled Osaka’s participation in an international Buddhist world.

It is revealing to compare the austere lines of early Osaka temple halls with the more ornate styles that later developed in Nara and Kyoto. The Osaka versions are restrained, their surfaces plain, their proportions modest. Yet this simplicity gave them gravity. They were more than religious buildings; they were experiments in adapting foreign forms to Japanese timber and landscape. Every beam and bracket became part of a cultural negotiation.

One small but telling detail is the use of gilt bronze for Buddha statues, often cast using techniques that demanded high precision. The survival of such works, fragmentary yet luminous, shows how Osaka’s artisans were quickly mastering a repertoire of sacred forms. In their faces—oval, serene, with faint smiles—one can still glimpse the continental models, but also the beginnings of a Japanese sensibility: softer features, less severity, a more approachable divinity.

Temple sculpture and reliquary design

Perhaps the most intimate art to arrive with Buddhism was not architectural but portable: reliquaries, sutra containers, and small statues designed for devotion. Osaka, with its access to trade, became a center for the circulation of such objects. Gilded bronze caskets decorated with lotus petals, tiny wooden Buddhas painted with natural pigments, and ritual implements of bronze and iron found their way into temple treasuries.

Sculptural art, too, took root. The Asuka-period statues that once stood in Osaka’s early temples bore hallmarks of Korean artistry: elongated proportions, almond-shaped eyes, and flowing drapery that seemed to ripple in metal. These figures were more than representations—they were embodiments of presence. In ceremonies, incense smoke would rise around them, flickering lamplight catching the gilt surfaces, creating an experience that was as theatrical as it was spiritual.

In this sense, Osaka’s earliest Buddhist art already contained the seed of what would become a defining feature of the city’s culture: the interplay of performance, devotion, and public gathering. Temples were not only religious centers but stages where the community experienced awe, shared ritual, and collective imagination.

Naniwa as Imperial Capital

For a brief but consequential span of years, Osaka—then known as Naniwa—rose to the rank of imperial capital. Though overshadowed in memory by Nara and Kyoto, Naniwa’s moment as a political and cultural center left subtle but lasting traces on its artistic history. The decision to situate a capital here was no accident: the city’s harbor, open to continental trade, made it a logical gateway for diplomacy, religion, and goods. In that fleeting age, art became a tool of statecraft as much as devotion.

The palace of emperors and their successors

The Naniwa Palace, built in the 7th century, was conceived as both administrative hub and ceremonial theater. Its wooden halls, tiled roofs, and elevated platforms were modeled on Chinese courtly architecture, signaling Japan’s ambitions to present itself as an equal in the East Asian world order. Excavations in Osaka have revealed foundation stones, roof tiles, and fragments of painted plaster that hint at its scale and refinement.

Although little survives above ground, contemporary chronicles describe audiences, rituals, and the reception of envoys within these halls. The palace thus functioned as an artistic space in itself, where architecture, costume, and ceremonial performance combined to project imperial dignity. Even the arrangement of courtyards and gates carried symbolic weight, orchestrating movement and hierarchy in a way that was both political and aesthetic.

Osaka’s short-lived political centrality

Yet Naniwa’s role as capital proved fragile. Repeated fires, shifts in imperial strategy, and the eventual preference for Nara’s inland stability led to its decline as a political center. By the late 8th century, the seat of government had moved, and Naniwa faded back into the role of a port town.

The brevity of this capital status makes its artistic imprint all the more poignant. Unlike Kyoto, which accumulated centuries of courtly art, Naniwa’s imperial culture was ephemeral. Its art was less about accumulation than about performance—moments of splendor staged in wood and tile, then lost to fire or decay. But in those moments, Osaka’s landscape was charged with symbolic presence, a place where continental styles mingled with Japanese ritual in the service of power.

Artistic echoes of imperial presence

Even after the capital moved, the memory of Naniwa as an imperial site persisted in art and ritual. Poems composed at the time evoke its harbors and palaces, linking the city’s natural setting to its political stature. Religious institutions founded under imperial patronage remained, carrying forward styles and treasures that had first arrived in the capital era.

Most significantly, the experience of being a courtly center planted in Osaka a sensibility for spectacle and exchange. The city had learned to play host: to welcome emissaries, to stage ceremonies, to use art as a medium of diplomacy. That role as a stage would resurface centuries later when Osaka reinvented itself as the merchant capital of Japan, alive with theaters, prints, and festivals.

Naniwa’s time as capital was fleeting, but the cultural echoes were lasting. They gave Osaka a memory of grandeur, a precedent for public display, and a continuing association with the arts of performance and ritual.

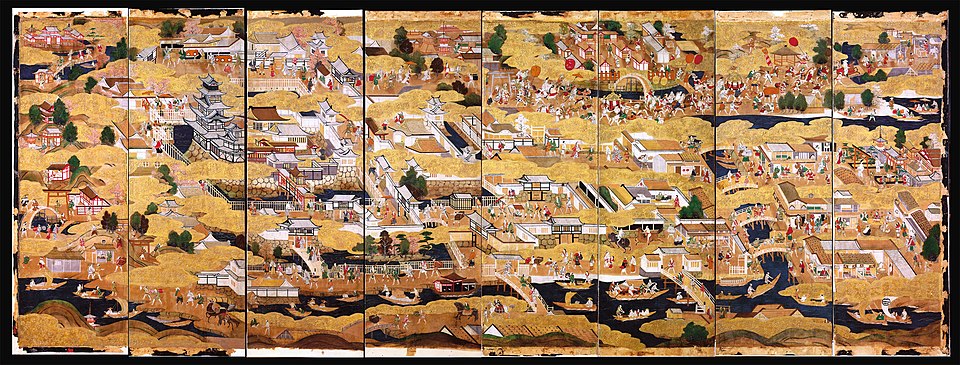

Merchant Energy and Chōnin Culture

If Naniwa’s palace halls represented fleeting imperial splendor, the Osaka that re-emerged in the early modern era belonged to a very different class: merchants, artisans, and townspeople—the chōnin. By the 17th century, Osaka had earned the title of tenka no daidokoro, the “kitchen of the realm,” as rice and goods from across Japan were funneled through its warehouses and markets. Wealth flowed not through aristocratic lineage but through trade and clever enterprise. From that wealth came a new kind of art: witty, practical, urbane, and often tinged with humor. Unlike Kyoto’s courtly refinement or Edo’s samurai spectacle, Osaka’s artistic culture bore the stamp of mercantile pragmatism and urban inventiveness.

Osaka’s rise as “the kitchen of Japan”

Rice was currency as well as food, and Osaka’s rice brokers were among the wealthiest figures in the country. Their storehouses, lined along canals and rivers, gave the city a distinctive architectural profile, but they also supported a culture of refined sociability. These brokers and merchants became patrons of the arts—not in the grand commissions of temples or palaces, but in the support of poetry circles, theater troupes, painters, and artisans who produced works for an urban audience.

Objects of daily life reflected this mercantile aesthetic. Folding screens depicting bustling markets, ceramics designed for convivial sake-drinking, and textiles with bold but tasteful patterns all found ready patrons in Osaka. The goal was rarely ostentatious display; rather, it was to cultivate iki—a sense of stylish understatement. In this, Osaka’s art mirrored its marketplace: competitive, varied, yet grounded in function.

Three details capture the flavor of this chōnin culture:

- Shop signs carved with humorous images that doubled as advertisements.

- Playful netsuke toggles, carved in ivory or wood, that added wit to functional accessories.

- Illustrated guides to the city’s restaurants and entertainments, blurring art with practical information.

In all these forms, the line between necessity and aesthetic pleasure blurred, making art inseparable from everyday life.

Practical aesthetics in daily life objects

One striking aspect of Osaka’s merchant-driven art is its practicality. The same mindset that made a broker track the flow of rice markets also led to an art of balance, efficiency, and precision. Calligraphy competitions became a popular pastime, with elegant handwriting valued as both an accomplishment and a form of entertainment. Tea gatherings in Osaka often lacked the rustic austerity favored in Kyoto, instead emphasizing polished wares and convivial atmosphere.

The merchant patrons of Osaka also favored illustrated books, many of them filled with humorous stories or guides to the pleasures of the city. These volumes, printed on inexpensive paper, were not only accessible but delightfully illustrated, marrying commerce, leisure, and artistry. A woodblock-printed book might include recipes, jokes, and caricatures of well-known figures—a reminder that in Osaka, art could be both beautiful and useful.

This spirit extended to the city’s architecture. Townhouses (machiya) combined shop fronts with living quarters, their design emphasizing functionality but often adorned with latticework that introduced rhythm and visual delight. The facades along Osaka’s merchant districts created a continuous urban artwork: modest but carefully arranged, like a stage set for daily commerce.

The wit and humor of urban design

Perhaps the most distinctive trait of Osaka’s chōnin culture was its humor. While Edo’s samurai society tended toward formality, Osaka’s merchants cultivated an art of playfulness and satire. Comic verse known as senryū flourished, poking fun at human foibles with a sharp, urban wit. Caricature prints of actors, merchants, or even deities circulated in the city, making light of serious subjects in a way that reflected the merchants’ confidence and irreverence.

Festivals offered another outlet. Osaka’s summer celebrations, with their lanterns, portable shrines, and floats, turned streets into stages of exuberant creativity. Decorations were often temporary, but their design demanded artistry: lanterns painted with bold calligraphy, banners embroidered with witty slogans, floats festooned with figures that combined craftsmanship with comic exaggeration.

The city’s merchants also patronized puppet theater and kabuki, arts that thrived on humor, parody, and spectacle. In this setting, art was not aloof but participatory. It was designed to amuse, to impress, and to draw people together—just as a thriving market did.

In all these forms, Osaka’s chōnin culture created an urban aesthetic distinct from that of Kyoto and Edo. It was grounded in commerce, enriched by wit, and dedicated to making art part of the rhythms of daily life. That balance of practicality and play would become one of Osaka’s defining artistic legacies.

Kabuki and Bunraku Flourish

If Osaka’s merchants gave the city its economic muscle, the performing arts gave it a cultural soul. By the 17th century, the bustling port was not only a center of trade but also one of the liveliest stages in Japan. Kabuki and bunraku—two theatrical traditions that thrived in Osaka—transformed the city into a laboratory of performance, where drama, music, costume, and stagecraft combined into a rich artistic ecosystem. These theaters were not peripheral amusements; they were central to how Osaka defined itself, fusing commerce, entertainment, and artistry in ways no other Japanese city quite matched.

Osaka as a performing-arts hub

Theaters flourished along the Dōtonbori canal, where rows of playhouses lit by lanterns beckoned audiences from all walks of life. Unlike the cloistered rituals of temples or the rarefied circles of court poetry, kabuki and bunraku were unabashedly public. Merchants, artisans, women, and even travelers from other provinces crowded into the playhouses. For the cost of a ticket, the city itself became a stage, its urban energy condensed into music, dance, and spectacle.

Kabuki, with its flamboyant actors, exaggerated gestures, and elaborate costumes, provided a visual feast. Bunraku, Osaka’s specialty, offered a subtler experience: life-size puppets manipulated by teams of skilled puppeteers, accompanied by chanting narrators (tayū) and shamisen players. The pairing of these two forms in one city created a dynamic theatrical culture unmatched elsewhere.

A vivid anecdote survives from the early 18th century, when the famed playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon debuted one of his domestic tragedies in an Osaka bunraku theater. The story of a love suicide between merchant and courtesan struck so deeply that audiences reportedly imitated it in real life, leading to temporary bans on the theme. Such intensity shows the power these performances held—art not as escapism but as a mirror of urban existence.

Puppet theater’s refinement of gesture and costume

Bunraku reached extraordinary heights of refinement in Osaka. Each puppet required three operators: one for the head and right arm, one for the left arm, and one for the legs. Their movements, though exposed to the audience, blended seamlessly, giving the figures uncanny lifelikeness. The expressiveness of a tilt of the head or a slow raising of the hand rivaled the skills of live actors.

Costume design was equally elaborate. Silk robes, embroidered with dazzling patterns, brought visual richness to the stage. The puppets’ garments often echoed contemporary fashions, creating a dialogue between stage and street. Merchants could see their own world mirrored in puppet form, stylized yet familiar.

What makes bunraku especially fascinating as art is its integration of multiple crafts: puppet carving, costume sewing, shamisen music, narrative chanting, and stage engineering. Each was a discipline in its own right, but together they formed a synthesis greater than the sum of parts. In a sense, bunraku was Osaka’s version of the Gesamtkunstwerk—a total artwork binding multiple traditions into one.

Actor-centered celebrity culture

Kabuki, too, developed its own artistic ecosystem, particularly through the cult of actors. Unlike Edo, where political censorship was stricter, Osaka’s kabuki could cultivate a more intimate relationship between actors and fans. Playbills, illustrated books, and painted signboards turned actors into celebrities. Their stage poses (mie), captured in woodblock prints, circulated as coveted keepsakes.

This celebrity culture was both commercial and artistic. Merchants patronized actors much as they might sponsor poets or painters, and in return they gained cultural prestige. Audiences shouted the names of favored actors during performances, blurring the line between spectator and participant. The theater became a communal artwork, fed by energy flowing both from stage to seats and back again.

Kabuki costumes, with their bold patterns and dazzling colors, influenced fashion far beyond the stage. Osaka’s textile merchants studied them closely, producing fabrics that allowed townspeople to echo the styles of their favorite performers. Once again, art and commerce proved inseparable.

The Printmakers of Osaka

From the glow of lantern-lit theaters, Osaka’s artistic energy spilled onto paper. Woodblock prints, or ukiyo-e, became the city’s distinctive way of capturing and circulating its culture. Yet unlike Edo, whose prints often depicted courtesans, landscapes, and seasonal pleasures, Osaka’s printmakers focused on the actors who lit up the local kabuki stages. The result was a body of work intimate in scale but powerful in presence: portraits of performers so vivid that audiences could carry the memory of a performance home with them.

Actor portraiture vs. Edo’s floating world prints

The ukiyo-e of Edo reveled in the breadth of the “floating world”—pleasure quarters, famous vistas, scenes of travel. Osaka’s printmakers chose depth over breadth. Their specialty was yakusha-e: actor portraits, often half-length, that captured a single moment of heightened performance. The faces, rendered with sharp lines and saturated colors, convey expressions of anguish, resolve, or ecstasy, freezing in woodblock the very poses (mie) that thrilled theater audiences.

One reason for this focus was practical. Osaka’s theater culture was so central that actors became the city’s most recognizable celebrities. Fans wanted keepsakes, and publishers obliged. But there was also an aesthetic reason: by limiting subject matter, Osaka artists refined the form, producing portraits of startling psychological intensity. Compared to Edo prints, often produced in large editions for a mass market, Osaka prints were made in smaller numbers, sometimes with deluxe techniques like mica backgrounds or embossing. This gave them a jewel-like quality, more collectible than disposable.

The difference could be summed up this way: Edo prints celebrated a world of many pleasures; Osaka prints zeroed in on the magnetic force of a single performance, a single face.

The networks of publishers, carvers, and fans

Behind each print was a network of artisans and patrons. Publishers in Osaka often worked closely with theater managers, ensuring that new plays were accompanied by new portraits. Woodblock carvers and printers collaborated to achieve fine lines and delicate shading, particularly in facial features and kimono patterns. Because editions were small, quality often trumped quantity, resulting in prints that feel more personal than mass-produced.

Audiences played a role as well. Fans might pool resources to commission special editions commemorating favorite actors. Some prints were even distributed as gifts within fan clubs, not sold widely. This intimacy of circulation made the prints function almost like souvenirs of a shared experience rather than generic commodities.

A fascinating detail is that many Osaka prints were inscribed with the names of actors, roles, and theaters—information that made them both artworks and historical records. Today they provide not only aesthetic delight but also a vivid map of Osaka’s performing arts scene in its golden age.

Osaka’s distinct graphic style

Stylistically, Osaka prints are instantly recognizable. The figures often dominate the frame, their torsos cropped close, faces turned dramatically, expressions heightened to theatrical extremes. Colors are bold and saturated, with heavy use of reds, oranges, and deep blacks. The backgrounds, by contrast, are sparse, sometimes filled with flat color or sprinkled with mica to make the actor stand out like a star under stage lights.

The emphasis on immediacy gives these prints a striking modernity. They feel less like distant depictions and more like encounters—face-to-face, eye-to-eye. Where Edo’s ukiyo-e sometimes invite leisurely wandering across landscape or narrative detail, Osaka’s confront you with presence.

The best-known masters of this tradition—artists such as Natori Shunsen, Ryūkōsai Jokei, and Sadamasu (Konishi Hirosada)—developed a graphic language that fused portraiture with performance. In their prints, Osaka’s theaters lived on beyond the ephemerality of a single night’s show. The actor’s pose, once fleeting, became eternal.

In this way, the printmakers of Osaka extended the city’s chōnin culture: practical yet stylish, intimate yet public, rooted in commerce yet elevated to art.

Painting in Osaka

While prints carried the pulse of the theater and streets, painting in Osaka cultivated a quieter but no less distinctive voice. The city’s painters worked in conversation with Kyoto and Edo, yet their sensibilities reflected the mercantile and literati environment of a port town. Their canvases—whether sliding doors, folding screens, or hanging scrolls—show a blend of inherited traditions and inventive departures, shaped by Osaka’s role as a hub of trade and intellectual exchange.

The Kano school’s presence

The Kano school, dominant across Japan from the 15th through the 19th centuries, maintained branches in Osaka that produced works for temples, castles, and wealthy patrons. Their style—ink landscapes, bold brushwork, and gold-leaf screens—was the official language of power. In Osaka, however, this language softened. Commissions from merchants often called for imagery less martial and more domestic: birds and flowers, scenes of seasonal change, or landscapes that paired grandeur with intimacy.

An example can be found in sliding door paintings commissioned for merchant villas, where cranes and pines offered auspicious symbolism but were executed with a gentler hand than in Edo’s warrior households. The Kano painters of Osaka adjusted their palette and subject matter to suit the tastes of a clientele that prized prosperity and stability over military bravado. Their paintings became symbols of cultivated success in the world of commerce.

Literati painting circles

Alongside the formal Kano lineage, Osaka became a center for literati painting, inspired by Chinese scholar-artists. These bunjin gathered in salons, composing poetry, painting landscapes, and sharing tea in a spirit of refined sociability. Unlike courtly traditions, literati painting carried an aura of amateurism—art created not for the market but as an extension of personal cultivation.

Osaka’s literati embraced this ethos while giving it a local flavor. Their landscapes often depicted the city’s rivers, bridges, and surrounding mountains, fusing Chinese motifs with familiar scenery. Ink washes evoked mist over the Yodo River; delicate strokes rendered plum blossoms in suburban gardens. Many of these artists were themselves merchants or doctors, their dual identities lending their art a sense of intimacy.

What makes Osaka’s literati circles remarkable is their inclusivity. Unlike in Kyoto, where aristocratic lineage often defined membership, Osaka’s gatherings welcomed those with curiosity and talent, regardless of background. Poetry, calligraphy, and painting were cultivated side by side, producing hybrid works that resist neat categorization.

Cross-pollination with poetry and theater

Painting in Osaka did not exist in isolation. It absorbed the rhythms of the city’s poetry and theater. Some screens feature scenes of kabuki performance; others pair images with witty verses in the style of haikai or senryū. Painters collaborated with poets to create shikishi (decorated poem cards), where brushwork and verse shared equal weight.

One fascinating example is the practice of haiga, or “haiku painting,” where quick, almost playful brushstrokes illustrated a poem’s imagery. These works often carried humor and lightness, echoing the city’s theatrical wit. A simple ink sketch of a fish, paired with a witty verse about a market stall, could be both art and social commentary.

This cross-pollination gave Osaka’s painting a distinctive liveliness. It lacked the aloofness of some Kyoto works or the formality of Edo commissions. Instead, it reflected the city’s broader character: sociable, witty, and open to experiment.

In sum, painting in Osaka reveals a balance between tradition and innovation, seriousness and play. Whether in the disciplined brushwork of Kano artists or the fluid spontaneity of literati circles, Osaka’s painters captured the city’s spirit in ways that paralleled, yet never merely imitated, the centers around them.

Ceramics, Lacquer, and Applied Arts

If Osaka’s theaters and paintings captured the city’s wit and imagination, its applied arts revealed another side of its culture: refinement embedded in the objects of daily life. In ceramics, lacquerware, and other crafts, Osaka artisans produced works that mirrored the rhythms of dining, drinking, and sociability. Unlike Kyoto’s imperial commissions or Edo’s samurai accoutrements, Osaka’s applied arts often arose from the demands of a mercantile society—beautiful yet practical, stylish yet tied to convivial use.

Sake cups, merchant wares, and subtle luxury

Ceramics in Osaka were closely linked to the city’s role as a distributor. While Kyoto and Seto might have been the production centers, Osaka’s kilns and merchant networks ensured that distinctive wares flowed through its markets. Tea bowls, sake cups, and serving dishes were staples, designed not for aristocratic tea ceremony alone but for the wider culture of feasting that animated the merchant class.

One recurring theme was subtle luxury. Glazes were chosen not for flamboyance but for restrained depth: pale celadons, warm iron browns, or soft ash effects. Merchants prized these pieces for their balance of elegance and durability. A sake cup might be humble in scale but reveal extraordinary attention to form, its rim thinned to perfection, its glaze pooling in a way that caught lamplight during a gathering.

Ceramics also entered theatrical spaces. Playhouses served sake in specially decorated cups, sometimes commemorating performances. Patrons might carry these home, turning a functional vessel into a souvenir of shared experience.

Osaka’s trade role in decorative objects

Beyond ceramics, Osaka was a vital conduit for lacquerware and metalwork. Artisans in the city specialized in inlay and maki-e (gold and silver sprinkled designs on lacquer), creating boxes, trays, and writing implements that circulated widely. These objects often bore motifs of seasonal flowers, waves, or auspicious symbols, resonating with the merchant taste for items that combined utility with cultural reference.

Trade ensured that Osaka artisans could access diverse materials—shell for inlay, pigments, metals—while also serving as middlemen for crafts from other provinces. A writing box from Wajima or a sword fitting from Satsuma might pass through Osaka’s markets, acquiring new decoration or reinterpretation before reaching its final owner. In this way, Osaka was not just a site of production but of transformation, where the applied arts were continually re-contextualized.

One delightful detail is that shop signs themselves sometimes became works of art. Lacquered plaques with gilded characters hung outside merchant houses, their visual polish signaling the prosperity within. Even the thresholds of Osaka’s businesses carried artistic weight.

Artisanship linked to conviviality

What sets Osaka’s applied arts apart is their connection to convivial culture. Lacquer trays bore designs that would be revealed gradually as food was consumed; ceramic bowls were chosen to enhance the shared enjoyment of sake; writing boxes facilitated the exchange of witty poems at gatherings. These objects were not meant to sit untouched in display alcoves but to be handled, passed around, and enjoyed in company.

In this sense, the applied arts of Osaka echoed the performative nature of its theater. Both transformed ordinary gatherings into occasions of artistry. Just as a kabuki actor’s costume elevated a story, a lacquered tray elevated a meal. Both were fleeting, tied to time and place, but both demanded artistry to heighten the moment.

Three emblematic objects illustrate this ethos:

- A lacquered tobacco box, decorated with gold waves, designed for the sociable ritual of pipe-sharing.

- A ceramic sake flask with humorous inscriptions, blending function with wit.

- A writing case adorned with theater motifs, bridging practical tool and artistic statement.

Through such objects, Osaka’s applied arts reveal a culture in which beauty was inseparable from use, and artistry from daily life.

Meiji Modernity and Industrial Osaka

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 shattered Japan’s old social order and launched a wave of modernization that transformed Osaka as dramatically as it transformed Tokyo. For the city known as tenka no daidokoro—the kitchen of the realm—this was both an opportunity and a challenge. Its identity as a mercantile hub fitted neatly into the new emphasis on industry, but its older artistic traditions, rooted in chōnin culture and theater, suddenly had to contend with Western academic art, international exhibitions, and the demands of mass production. The art of Osaka in the Meiji era became a record of negotiation: between the handmade and the industrial, the local and the global, the traditional and the modern.

The challenge of Western realism

Western-style painting (yōga) arrived in Osaka in the late 19th century through exhibitions, imported books, and the establishment of art schools. Local artists grappled with oil paints, perspective, and anatomical realism—tools foreign to the brush-and-ink traditions they had inherited. For many, this was a dizzying shift. Osaka had long excelled in ukiyo-e and decorative arts, where stylization and flatness carried symbolic weight. To suddenly render shadows and vanishing points required rethinking what painting was meant to achieve.

Some artists embraced the challenge, studying abroad or training under teachers who had themselves absorbed European methods. Portraits in oil, landscapes rendered with atmospheric perspective, and still lifes of fruit and flowers appeared in Osaka salons. Others resisted, maintaining allegiance to traditional brushwork but experimenting with hybrid forms—combining Western realism with Japanese motifs. This tension, though at times awkward, produced a fertile space of innovation.

Theatrical culture also adapted. Stage sets for kabuki incorporated new techniques of illusionistic painting, while posters for performances began to echo Western lithography, introducing bold typography alongside images of actors. Even resistance became a form of adaptation: when Osaka audiences preferred the heightened gestures of kabuki to naturalistic acting styles, they were, in effect, choosing their own cultural modernity.

World’s fairs and the city’s new image

Osaka’s merchants and industrialists recognized that art was a means of international prestige. The city participated eagerly in world’s fairs, sending lacquerware, ceramics, and textiles abroad as emblems of Japanese craftsmanship. These objects were often redesigned to suit Western tastes—fans with exotic motifs, cloisonné enamelware with dazzling colors, folding screens depicting Mt. Fuji or cherry blossoms.

For Osaka artisans, this was both lucrative and disorienting. A lacquer tray once designed for a tea gathering might now be destined for a Paris salon. Patterns were altered, materials adjusted, and marketing strategies developed. Art became export commodity, tailored for audiences who valued it as exotic luxury rather than part of a lived cultural practice.

Domestically, exhibitions in Osaka showcased both industrial machinery and decorative arts, presenting the city as a place where tradition and technology coexisted. Visitors might see a steam engine displayed beside a case of lacquered boxes, or a loom alongside embroidered silk. Such juxtapositions made visible the dual identity Osaka was forging: workshop of industry and center of artistry.

Osaka as workshop of industrial design

Industrialization also changed the scale and purpose of artistry itself. Textile production in particular became one of Osaka’s hallmarks. Factories churned out cotton and silk, yet design remained crucial. Patterns for kimono fabrics, once painted by hand, were now adapted for mechanical printing. Designers had to learn how to create motifs that could withstand repetition on an industrial scale while retaining elegance.

Other applied arts followed similar paths. Metal workshops shifted from making sword fittings to producing decorative hardware for export; ceramic kilns experimented with glazes that appealed to Western buyers. Even the city’s graphic arts evolved: posters, packaging, and advertisements required a new kind of artistry that blended visual appeal with marketing savvy.

This new industrial aesthetic reflected Osaka’s pragmatic spirit. While Kyoto emphasized heritage and Tokyo pursued political centrality, Osaka embraced its identity as a producer. Art was not diminished by this; rather, it was redefined. A well-designed textile, an eye-catching label, or a precisely manufactured ornament became embodiments of artistry suited to a modern age.

In the Meiji years, Osaka’s art found itself stretched between opposites: between oil and ink, tradition and machine, domestic rituals and global markets. Yet the city’s resilience lay in its ability to embrace both sides. Just as merchants once balanced profit and refinement, Meiji Osaka balanced commerce and creativity, crafting a modern identity that would carry it into the 20th century.

Taishō and Shōwa Avant-Gardes

By the early 20th century, Osaka had fully embraced its role as Japan’s industrial workshop, but within that machinery of commerce, a restless artistic energy stirred. The Taishō (1912–1926) and early Shōwa (1926–1945) periods saw a flowering of avant-garde movements in the city. Radical painters, writers, and photographers tested the limits of what art could be, drawing inspiration from European modernism while channeling Osaka’s own urban intensity. Factories, neon lights, and the dense energy of the streets provided both subject matter and backdrop. This was not the refined literati world of Kyoto or the political modernism of Tokyo, but something more visceral: avant-garde art forged in the noise of industry and the pulse of commerce.

The Mavo movement and radical experiments

Osaka became a stage for experimental art groups such as Mavo, whose members sought to dismantle the boundary between art and life. Their works embraced collage, performance, and provocation. Posters were torn, reassembled, and painted over; stage events combined dance, visual art, and noise. These radical gestures resonated in Osaka, where the city’s very fabric seemed to embody hybridity and collision.

Artists in Osaka adapted Mavo’s spirit to their own environment. Some staged exhibitions in department stores, placing avant-garde canvases alongside consumer goods. Others produced lithographs and posters that blurred the line between advertisement and artwork. A striking anecdote tells of a Mavo-inspired exhibition where paintings were deliberately slashed or burned, echoing the city’s fascination with impermanence and transformation.

For a merchant-driven city, this avant-garde was more than provocation—it was recognition that the spectacle of art could match the spectacle of commerce. The display window, the billboard, and the gallery all became competing theaters of vision.

Photography and proletarian art circles

Osaka was also a center for early photography movements, particularly in the 1920s and 1930s. Amateur photography clubs flourished, often supported by camera companies based in the Kansai region. Members experimented with abstraction, montage, and documentary styles, producing images that captured both the dynamism and hardship of urban life. Factories, smokestacks, and crowded alleys appeared in stark black-and-white, transforming industrial scenery into artistic subject.

At the same time, Osaka nurtured circles of proletarian artists committed to socially engaged work. Painters and printmakers depicted the struggles of workers, the poverty of tenement districts, and the inequalities of rapid industrialization. Their art was not only aesthetic but political, intended to mobilize sympathy and awareness. Meetings, journals, and exhibitions in Osaka gave these movements a strong foothold, even as authorities monitored them closely.

The coexistence of experimental abstraction and socially conscious realism reveals Osaka’s pluralism. In a single neighborhood, one might find a photography club dissecting light and shadow while a workers’ collective sketched the lives of dock laborers. Both belonged to the same restless search for new visual languages in a modernizing city.

Osaka’s artists in wartime and reconstruction

The outbreak of war in the late 1930s brought severe constraints. Avant-garde groups were dissolved, and artists faced pressure to produce propaganda or withdraw from public life. Some Osaka painters turned to patriotic themes, while others retreated into private landscapes and still lifes, seeking refuge from political demands. The city’s industrial capacity made it a target for heavy bombing in 1945, and many works, studios, and collections were destroyed.

Yet even amid devastation, seeds of renewal survived. In the rubble of postwar Osaka, artists gathered once again, often informally, to sketch, paint, or stage impromptu performances. The experience of loss gave their work urgency. Photography captured ruins and reconstruction with raw honesty; abstract painters experimented with jagged forms and explosive color, reflecting the fractured world around them.

What emerged from this crucible was not a return to tradition but a readiness for radical new beginnings. Osaka’s artists had endured both the exhilaration of avant-garde experimentation and the repression of wartime discipline. That tension prepared the ground for what would follow: the Gutai group, one of the most influential movements in postwar Japanese art.

Contemporary Osaka

Postwar Osaka became the birthplace of some of the most daring artistic innovations in Japan. Emerging from ruins and rapid reconstruction, artists here sought not merely to revive older traditions but to invent new ones that could speak to an era of uncertainty, freedom, and technological change. From the explosive experiments of Gutai to the rise of manga and design culture, Osaka reasserted itself as a city where art thrived in the interplay of performance, commerce, and urban vitality.

The Gutai group and its legacies

Founded in 1954 by Jirō Yoshihara and a circle of young artists, Gutai (Gutai Bijutsu Kyōkai) announced itself with a radical manifesto: art should break free from imitation and convention, embracing direct engagement with materials and action. The group’s name, meaning “concreteness,” captured their desire to let materials speak in their own voices—whether through torn paper, splashed paint, or bodies colliding with canvas.

Osaka proved fertile ground for this revolution. The city’s industrial landscape, full of concrete, steel, and neon, gave Gutai artists raw matter to manipulate. Their performances—such as children running through sheets of paper or paintings created by hurling paint-filled bottles—transformed art into spectacle, echoing Osaka’s theatrical traditions in entirely new forms. International critics recognized Gutai as one of the first Asian avant-garde movements to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with Western contemporaries like Abstract Expressionism and Fluxus.

Gutai’s legacy remains visible in Osaka’s institutions. The group staged outdoor exhibitions in local parks, turning public space into a gallery, and collaborated with schools, democratizing art in a city that had always valued popular participation. Their spirit of experimentation still shapes Osaka’s reputation as a cultural innovator.

Postwar manga, design, and pop influence

Parallel to avant-garde movements, Osaka also became a crucible for popular culture. Manga artists found in the city’s bustling streets and comic sensibility fertile ground for stories that blended humor, satire, and adventure. Publishers in Osaka nurtured early talents who would go on to influence the national scene. The city’s wit, already evident in senryū and puppet plays centuries earlier, now found expression in inked panels and serialized magazines.

Design culture flourished as well. With Osaka’s central role in manufacturing, product design became a natural extension of artistry. Packaging, logos, and posters reflected both Western modernist trends and distinctly Japanese aesthetics. Companies headquartered in Osaka invested in visual identity, hiring artists to craft imagery that could compete in domestic and international markets. The city’s neon signage, especially in entertainment districts like Dōtonbori, became an art form in itself—commercial yet iconic, merging advertising with urban spectacle.

Perhaps most striking is the way Osaka’s popular and avant-garde cultures overlapped. Manga artists drew inspiration from Gutai’s radical gestures; designers borrowed theatrical flair from kabuki and bunraku traditions. The city’s cultural ecology blurred the supposed line between “high” and “low” art.

Current museum and gallery culture

Today, Osaka sustains a vibrant institutional and grassroots art scene. The National Museum of Art, Osaka, housed in a striking subterranean building, curates international modern and contemporary exhibitions. The Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts preserves traditional works, from calligraphy to ceramics, bridging past and present. Smaller galleries and artist-run spaces dot neighborhoods like Kitahama and Nakazakichō, often staging experimental shows that continue Gutai’s legacy of risk and play.

Public art projects, festivals, and design fairs keep art woven into the fabric of everyday life. Murals brighten concrete walls, pop-up exhibitions appear in department stores, and contemporary performers adapt bunraku puppetry to new contexts. Even Osaka’s food culture inspires design—menus, packaging, and restaurant interiors reflect the city’s ongoing fusion of utility and artistry.

In contemporary Osaka, art is not confined to white-walled galleries. It thrives in neon lights, manga panels, fashion boutiques, and street performances. This continuity with the city’s history is striking: from Jōmon pottery to Gutai explosions, Osaka has always treated art as something lived, shared, and performed. Its contemporary culture keeps that tradition alive, reminding us that in Osaka, art remains inseparable from the energy of daily life.

Osaka’s Place in Japanese and Global Art History

To understand Osaka’s role in art history is to recognize how consistently it has occupied a space distinct from both Kyoto and Tokyo. Kyoto, with its imperial lineage, cultivated refinement and continuity; Tokyo, with its political might, projected national ambition. Osaka, by contrast, was never primarily about court or state. Its artistic character grew instead from merchants, performers, artisans, and innovators—from those who made and traded, entertained and experimented. This difference gave Osaka’s art a personality of its own: pragmatic yet daring, rooted in daily life yet capable of bold leaps into the avant-garde.

Contrast with Kyoto and Tokyo

Kyoto’s art has long been associated with aristocratic taste, whether in the golden pavilions of temples or the elegance of courtly poetry and painting. Tokyo, especially after the Edo period, became synonymous with scale: sprawling ukiyo-e markets, monumental architecture, and eventually national museums and academies.

Osaka stood apart. Its ukiyo-e prints were smaller in circulation but sharper in psychological focus. Its puppet theater reached heights of artistry unknown in the capital. Its merchants commissioned screens and lacquerware less for dynastic display than for convivial gatherings. Even in modern times, while Tokyo often sought to align with international trends in fine art, Osaka maintained a streak of independence, producing Gutai’s radical experiments and sustaining one of Japan’s most irreverent popular cultures.

This contrast suggests that Osaka’s art history is less about inheritance or authority and more about reinvention. Whenever structures of power shifted away—whether when the capital moved to Nara or when Tokyo rose in political dominance—Osaka responded not by retreating but by cultivating its own forms of expression.

The enduring imprint of commerce and theater

From rice brokers’ townhouses to neon-lit entertainment districts, commerce and theater have been Osaka’s enduring engines of artistry. Few cities have fused economic life and cultural spectacle so completely. Bunraku and kabuki thrived because merchants had the means and appetite to sustain them. Actor prints flourished because audiences demanded keepsakes. Lacquer trays, sake cups, and textiles were refined because conviviality demanded beauty in the tools of gathering.

Even Gutai, radical as it was, reflected this performative and commercial inheritance. Its happenings and outdoor exhibitions echoed the festive atmosphere of earlier Osaka street culture. Its embrace of industrial materials mirrored the factories that defined the city. In this sense, Gutai did not break from Osaka’s past so much as carry its logic into a new medium.

Theatricality, sociability, and wit: these have been Osaka’s artistic constants, whether in a Jōmon pot, a kabuki pose, or a manga panel.

What Osaka contributes to Japan’s cultural balance

Seen within Japan as a whole, Osaka provides a crucial counterweight. Without Osaka, Japanese art history might tilt too heavily toward the aristocratic refinement of Kyoto or the centralized spectacle of Tokyo. Osaka introduced a third force: the culture of the townspeople, the energy of the market, the artistry of performance and pragmatism.

Globally, too, Osaka complicates the picture. It reminds us that Japanese art is not monolithic, nor solely the product of imperial capitals. The city’s contributions—from bunraku to Gutai—have entered the world stage as distinctly Osaka innovations, not simply “Japanese” in the abstract. When Gutai’s canvases exploded with action in Paris or New York, they carried the DNA of Osaka’s history: its humor, its daring, its embrace of the spectacular.

In the end, Osaka’s art history is a story of resilience and reinvention. Each era—prehistoric ritual, Buddhist temple, merchant theater, industrial workshop, avant-garde laboratory—left layers that continue to shape the city’s cultural identity. What unites them is a conviction that art is not remote or ornamental but part of life itself. In Osaka, art has always been lived: on stage, in markets, in factories, in the very gestures of everyday exchange. That, more than any single monument or masterpiece, is the city’s lasting contribution to Japan and to the wider history of art.