The painted caves of the Basque Country do not belong to Bilbao. And yet, without them, no serious account of Bilbao’s art history can begin.Tucked into the limestone folds of the Urdaibai estuary, the cave of Santimamiñe is often described in scientific terms: Upper Paleolithic, Magdalenian, dated to roughly 14,000 BC. But this clinical framing does little justice to the strangeness, vitality, and imaginative commitment of its interior images. To enter Santimamiñe is to walk into a darkness once animated by firelight and inhabited by red-deer, bison, goats, and horses—forms not merely depicted, but conjured into being by artists with astonishing confidence in line, movement, and contour.

The paintings at Santimamiñe are among the most important examples of prehistoric art in the Iberian Peninsula, and the only major decorated cave in the modern Basque Autonomous Community. But they are not isolated. Less than 50 miles east, across the present-day border with France, lie Isturitz and Oxocelhaya, a complex of prehistoric sanctuaries where over 25,000 years of occupation left behind not just cave paintings, but flutes, pendants, sculpted bone, and engraved ivory. This entire corridor—from the eastern Basque coast through Biscay and into Cantabria—was a cradle of artistic innovation at a time when much of Europe was locked in glacial stasis.

What’s remarkable about these sites isn’t just their survival but their coherence. The animals are often drawn with a single, continuous line. Their bodies stretch across rock protrusions in ways that suggest not only anatomical understanding, but theatrical instinct—using the curves of the cave walls to suggest motion or emergence. In some cases, artists scraped or cleaned older figures to make way for new ones, while in others they layered images, creating a dense palimpsest of animal life that hints at both ritual repetition and evolving pictorial conventions.

Three especially vivid characteristics of Basque cave art distinguish it from other regional schools:

- Compressed framing: Figures are often tightly packed, with minimal narrative separation—unlike the spacious compositions of Altamira or Chauvet.

- Technical layering: Engraving, charcoal, and pigment are frequently combined within a single figure, showing experimentation with depth and texture.

- Symbolic abstraction: Geometric marks, grid-like signs, and possible clan identifiers appear alongside animal forms, suggesting a dual function—both aesthetic and communicative.

While the exact purposes of these images remain unknown, their impact on local identity has been anything but obscure. From the late 19th century onward, as archaeological teams uncovered and documented these paintings, they began to seep into public consciousness as a uniquely Basque prehistory—a source of cultural continuity independent of Roman, Christian, or Spanish frames of reference.

Material culture and symbolic forms in prehistory

Alongside the cave art, the Basque region is rich in prehistoric portable art: carved antlers, pierced stones, ivory figurines, and eventually, megalithic constructions such as dolmens and tumuli. These objects point to a sophisticated symbolic economy. Art was not confined to the secret or sacred space of caves; it accompanied daily life, death, and travel.

One of the most compelling categories of this material culture is engraved bone plaques, some bearing cross-hatched patterns or rhythmic incisions that suggest early counting systems or calendrical marks. Others, like the so-called harpoons and batons de commandement, combine utility with ornament—practical tools elevated into ritual objects.

The evolution of these items over thousands of years offers an early form of artistic transmission. They express, across generations, a clear tension between abstraction and realism, a dynamic that will resurface repeatedly in Basque visual history. The use of animal motifs—particularly stags and bovines—also established a symbolic vocabulary that outlived the Ice Age. In later Basque folklore and religious iconography, horned animals retained an almost mystical aura.

It’s worth noting that Basque prehistoric art remained relatively underexamined in the major modernist revaluations of cave painting in the 20th century. While Picasso, Matisse, and later Bataille drew on the visual language of Altamira or Lascaux, Basque sites like Santimamiñe remained provincial in the European art-historical imagination. This peripheral status, paradoxically, preserved their symbolic potency within local frameworks. They could not be appropriated into national or stylistic myths; they remained stubbornly, locally profound.

How ancient forms echo in Basque visual consciousness

The relevance of prehistoric imagery in modern Basque art is not a matter of revival or quotation. It is subtler and more atmospheric—a set of recurring motifs, spatial intuitions, and symbolic structures that quietly shape the region’s visual sensibility.

Take the 20th-century sculptor Eduardo Chillida, who often spoke of mass, void, and weight in quasi-spiritual terms. His monumental iron works—placed in fields, along cliffs, or embedded in walls—echo the megalithic sensibility of prehistoric monuments, where human gesture meets geologic time. In Chillida’s Peine del Viento (1977), for example, rusted iron claws protrude from coastal rock as if they had always been there. The work does not depict prehistoric art, but it participates in the same logic: the integration of form, material, and site into an inseparable whole.

Another example is the painter and muralist Aurelio Arteta, whose flattened human figures, angular compositions, and preference for earthy tones hint at a primordial visual language—at once stylized and symbolic. Even in politically charged or industrial settings, his work often feels rooted in something older than modernism: an ancestral rhythm of pattern and ritual.

More recently, Basque contemporary artists have turned explicitly toward prehistoric reference. In the work of Itziar Okariz, performance and repetition act as symbolic echoes of ritual action. Meanwhile, the sculptural practice of Txomin Badiola replays prehistoric spatial hierarchies—enclosures, thresholds, altars—through post-industrial media.

These continuities are not accidents. In a region where political borders, spoken language, and official history have all been contested, prehistoric art has become a source of unclaimed permanence. It predates empire, church, and state. It offers a mode of visual thinking that is at once communal, anonymous, and beyond narrative.

Perhaps most importantly, it reminds us that the story of art in Bilbao does not begin with Bilbao. It begins in the dark, with charcoal and breath and fire.

The River and the Iron: Foundations of a Visual Culture

To understand the art history of Bilbao, it is not enough to look at canvases or stonework. One must look at the Nervión River, the color of oxidized ore, and the lopsided silhouettes of cranes. Before Bilbao became a city of art, it was a city of iron—and its visual culture grew out of mud, smoke, and cargo.

How geography shaped early artistic production

Bilbao was founded in 1300 by Don Diego López V de Haro, but the landscape into which it was born had already been shaped by centuries of informal settlement, monastic construction, and resource extraction. The Nervión estuary, winding from the Bay of Biscay into the hills of Biscay province, formed a natural trade artery. Its muddy banks and tidal flats were not picturesque but functional. Ships came inland to load and unload goods: salt, wool, cod, and most importantly, iron ore—the red dust that stained ships, tools, and hands.

This geography had visual consequences. The earliest built environment of Bilbao was stark and deliberate. The Casco Viejo (Old Town) grew up along seven narrow streets—the Zazpi Kaleak—that hugged the river and funneled goods directly from the docks into the heart of the city. These streets produced no monumental piazzas or elaborate façades; they were dense, commercial, and utilitarian. But they created a kind of spatial intimacy, a visual compression that shaped the aesthetics of daily life: shop signs hanging close to faces, carved lintels above doorways, ironwork balconies blooming overhead like modest canopies of ornament.

The city’s early churches followed suit. Santiago Cathedral, completed in Gothic style in the 15th century, is neither large nor showy by European standards. Yet its ribbed vaults and pointed arches carry a sense of vertical aspiration that feels all the more acute against the low, packed scale of the surrounding neighborhood. Religious architecture in early Bilbao did not strive for grandeur; it sought to integrate itself into the fabric of the working town.

And in this integration lies an aesthetic code: form serving function, beauty emerging from constraint, and ornament subordinated to material clarity. These values would reappear in surprising places centuries later, from the rationalist architecture of the 1920s to the steel-and-glass confidence of Gehry’s Guggenheim. But they first came from mud and masonry.

Religious iconography in medieval Bilbao

Although Bilbao lacked the lavish artistic commissions seen in Castile or Catalonia, its churches did support a modest but distinctive program of religious art. Much of this work—altarpieces, retables, statuary—was executed in wood, a material more responsive to the humid Biscayan climate and the tastes of local craftsmen.

One of the most notable examples is the polychrome wooden altarpiece in the Church of San Antón, a 15th-century Gothic construction that sits directly above the river’s edge. The altarpiece combines scenes from the life of Christ with images of local saints, most notably Saint Mammes—a protector of shepherds whose obscure iconography (often depicted with a lion) suggests pre-Christian symbolic residues.

These works were not created by famous artists. Most were carved by members of guilds, local associations of artisans who trained in regional styles and often passed techniques from father to son. Their work can feel formulaic, even crude, when compared to the Flemish panels or Italian frescoes of the same period. But there is also a kind of directness in their gesture—a stripped-down symbolism that favored emotional clarity over compositional sophistication.

A handful of imported works did reach Bilbao in the 15th and 16th centuries, often through trade routes connecting it to Bruges, Bordeaux, or Seville. These were primarily small devotional images: portable altarpieces, oil-on-panel Virgin and Child scenes, or miniature manuscripts. They circulated among wealthy merchant families and were sometimes donated to churches as acts of piety. But their influence remained limited. The visual culture of the city remained, overwhelmingly, crafted in place—made by local hands, using local stone and local themes.

Three motifs dominated this early religious art:

- St. James as pilgrim, a symbol of connection to the Camino de Santiago and thus to broader Christian Europe.

- Crucifixion scenes with unusually expressive faces, perhaps reflecting the raw intensity of northern Spanish mysticism.

- Madonna-and-child statues carved in rigid vertical poses, emphasizing divine authority over maternal tenderness.

Though modest in size and fame, these works created a visual continuity between home, church, and street. Religious art was not something visited or admired; it was omnipresent, woven into the routines of life, maintenance, and prayer.

The artisan guilds and proto-industrial aesthetics

By the late 16th century, Bilbao had grown into a small but strategically important port, and its economy rested increasingly on metalwork. The surrounding hills were rich in hematite, a high-quality iron ore that required minimal refining. As mining increased, so did the trades associated with it: smelting, forging, blacksmithing, and shipping. And while these were not “artistic” trades in the conventional sense, they had an unmistakable visual impact.

The iron balconies, grilles, hinges, and locks produced in Bilbao during this period were both functional and expressive. Even a casual glance at surviving 17th-century hardware in the Casco Viejo reveals a balance between mass production and creative flair: spiral finials, floral insets, and stylized crosses that gave weighty objects a kind of visual rhythm.

One telling example is the forged iron crest above the entrance to the Consulado de Bilbao (the old Chamber of Commerce), a Baroque building completed in the 18th century. The crest is brutal and elegant at once: a muscular cartouche supported by coiling vines and topped by the castle-and-lion heraldry of Castile. It is an object of statecraft, yes—but also of artistry. The tension between authority and flourish, form and force, is unmistakably industrial in tone and visual logic.

These artisanal traditions provided Bilbao with a proto-industrial visual language long before the term existed. Unlike cities whose art history is dominated by courts or academies, Bilbao’s was shaped by tools, craftsmen, and material constraints. The city developed a vocabulary of form that was simultaneously austere and inventive—decorative without being ostentatious, and expressive without surrendering to romanticism.

It also set a precedent: that the visual language of a place need not come from aristocratic patronage or ecclesiastical edict. It could come from the people who built the city, with smoke in their eyes and iron under their fingernails.

The shadow of that idea—art as an outgrowth of work, art as inseparable from place—would linger long into the 20th century, waiting for a generation of Basque painters and sculptors to give it monumental form.

The Liberal Century: Romanticism and Industrial Patronage

In the 19th century, Bilbao became unrecognizable—geographically, politically, and culturally. What had once been a small medieval port clinging to the Nervión transformed into a roaring industrial capital. This transformation was not merely economic; it was visual. The rise of bourgeois power, the trauma of the Carlist Wars, and the clash between romantic nationalism and cosmopolitan modernity reshaped the city’s aesthetics in permanent ways.

Art in the shadow of the Carlist Wars

Between 1833 and 1876, the three Carlist Wars devastated large portions of northern Spain, and Bilbao was repeatedly drawn into the conflict. The city was besieged twice—first in 1836 and again in 1874—by forces loyal to the Carlist claimant to the Spanish throne. These sieges were brutal, but they also marked the beginning of Bilbao’s self-image as a liberal stronghold, committed to constitutional monarchy, free commerce, and civil reform.

This political identity found expression in artistic patronage and subject matter. The liberal bourgeoisie, emerging from trade and industry, began to commission works that emphasized values such as reason, progress, and civic order. One illustrative case is the 1844 portrait of Juan Egaña, a liberal reformer and Basque constitutionalist, painted by an unknown local artist. Though modest in scale, the painting reflects a new visual regime: seated posture, sober dress, books at the elbow, and a faint suggestion of introspective melancholy—a blend of neoclassical restraint and romantic interiority.

More dramatic were the images of war and martyrdom that emerged during and after the sieges. Local engravers and draftsmen, influenced by Goya and the French Romantic school, produced scenes of heroic resistance, burning rooftops, and patriotic sacrifice. These were not academic works destined for museums, but prints circulated in newspapers, pamphlets, and public offices. They were meant to inspire solidarity, not aesthetic contemplation.

One striking example, published anonymously in 1874, shows Bilbao’s defenders manning improvised barricades as artillery shells fall from the Carlist batteries in the hills. The style is crude, but the emotional force is palpable: faces contorted in effort, buildings crumbling into ash, and a ragged Basque flag held defiantly against the smoke. Here, art functioned as immediate civic myth-making—an aesthetic of survival.

This period also saw the popularization of regional costume, peasant dances, and folk rituals as visual shorthand for “authentic” Basque identity. Painters began to depict market scenes, village festivals, and rural labor in sentimental tones, part ethnography, part nostalgia. But these works often bore little resemblance to actual peasant life. They were, in effect, romantic inventions: visual ideologies dressed in linen skirts and berets, offering reassurance to an urban class anxious about the pace of change.

New bourgeois patrons and their private collections

As Bilbao industrialized—first through steel, then shipbuilding, and eventually banking—a new class of patrons emerged: the commercial bourgeoisie. These were men who had grown wealthy not from aristocratic landholding but from contracts, railroads, coal imports, and mining concessions. They had little interest in medieval lineage, but they recognized the cultural value of painting, sculpture, and architecture as instruments of legitimacy.

Many began to collect art, not in the grand salon style of Madrid or Paris, but with a regional emphasis. Private collections in Bilbao during the second half of the 19th century leaned heavily on:

- Costumbrista scenes by local or itinerant painters, emphasizing everyday life with folkloric color.

- Landscape paintings, especially views of the Basque coast, valleys, and industrial rivers, often executed in a modified romantic-naturalist style.

- Portraiture, particularly family commissions by provincial artists trained in Madrid or Bordeaux.

One of the most important early collections belonged to Martín de los Heros, a liberal politician and writer. His salon featured works by both Spanish and foreign painters, including copies of Velázquez and original works by French academic artists. Though few of these paintings survive in public collections today, their role in establishing art as a form of elite civic taste cannot be overstated.

Perhaps the most influential figure of this new collecting class was Ramón de la Sota, a shipowner and industrialist who amassed an impressive collection of late 19th-century Spanish painting, much of which eventually helped form the core of the Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao, founded in 1908.

De la Sota’s taste leaned toward figurative realism, historical themes, and noble sentiment—less daring than Madrid’s avant-garde, but rooted in a deep belief in art as a civilizing force. His patronage extended beyond collecting: he funded scholarships, supported local art schools, and underwrote architectural commissions that married function with aesthetic ambition.

Industrialization’s effect on subject matter and style

By the 1880s, Bilbao had fully entered its industrial age. Chimneys lined the river. Iron bridges spanned the Nervión. The skyline bristled with cranes, silos, and smokestacks. This new reality demanded new forms of representation—and slowly, it began to shape subject matter and style.

Some painters, particularly those influenced by realism and early impressionism, turned directly to industrial labor as a theme. Adolfo Guiard, a Bilbao-born painter trained in Paris, created works that hovered between plein-air lyricism and documentary observation. His painting El mercado del pescado (1890) depicts a riverside fish market not as a genre tableau, but as a dynamic choreography of color, gesture, and movement—marked by soot, water, and noise.

Others took a more symbolic route. Anselmo Guinea, another key figure of Bilbao’s late 19th-century art scene, fused romantic technique with social commentary. In his work La sesta del herrero (The Blacksmith’s Nap), we see not heroic labor but exhausted humanity: a worker collapsed in the shade, his tools beside him, his shirt stained with sweat and iron dust. It is both a celebration of dignity and a meditation on fatigue—an aesthetic of stoic realism far removed from the idealized peasants of earlier decades.

The city’s changing infrastructure also drew visual attention. The construction of the Arenal Bridge in 1878, the expansion of railways, and the proliferation of iron structures gave artists new formal challenges: how to render metal, fog, and motion; how to depict power without sentimentality.

By the century’s end, a new aesthetic had begun to take hold—one that rejected both rural nostalgia and academic conservatism. The groundwork had been laid for a modernist turn, and for the emergence of painters who would make Bilbao not only a center of production, but of artistic innovation.

That tension—between the brute fact of industry and the delicate gestures of art—remains one of the defining contradictions of Bilbao’s visual history. It is a city that has always asked how to make beauty from labor, and how to see in steel and soot not ruin, but form.

Bilbao’s First Museums and the Question of Basque Identity

At the turn of the 20th century, Bilbao was not just a port or an industrial city—it was becoming something more difficult to define: a cultural entity with competing narratives of heritage, modernity, and place. Art was no longer merely the domain of guilds or private collectors. It began to be institutionalized, curated, and—most crucially—claimed as part of a civic identity. The founding of the Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao in 1908 marked a critical inflection point: art was now public, and with that came the vexed question of who that public was and what it meant to be “Basque.”

The 1908 founding of the Museo de Bellas Artes

The Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao was not an act of royal fiat or state initiative. It was built through local ambition, driven by industrial wealth and municipal pride. Its earliest champions included figures like Juan de la Cruz de Achúcarro, a lawyer and cultural activist, and Laureano de Jado, a wealthy patron whose private collection seeded much of the museum’s original inventory.

The founding rationale was as much political as cultural. Bilbao’s elite recognized that a proper museum conferred legitimacy—not just on the city, but on their own role within it. A fine arts museum allowed Bilbao to assert parity with Madrid and Barcelona, to stake a claim in the visual and intellectual life of the Spanish nation. But unlike the Prado or the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Bilbao’s museum had no royal collection, no Gothic cathedrals to draw from. It had to assemble itself from scratch, piece by piece, from donations, purchases, and loans.

This gave the institution a unique character from the outset:

- It was pluralist, with works ranging from medieval devotional art to contemporary painting, often housed side by side.

- It was regionally anchored, with a deliberate focus on artists from the Basque Country and nearby provinces.

- It was educational, aimed not at elite connoisseurs but at an emerging middle class eager for cultural sophistication.

The early decades of the museum’s existence were a balancing act. On one hand, the curators sought to build a credible collection of Spanish and European art—acquiring works by El Greco, Zurbarán, and Lucas Cranach the Elder. On the other hand, they made space for a rising generation of Basque painters who were redefining what local art could be.

This tension—between universalist aspiration and regional specificity—would remain at the heart of the museum’s mission for the next hundred years.

Early regionalist painting and cultural nationalism

By the early 20th century, a distinct Basque regionalism had taken hold in the visual arts. This was not a simple folkloric revival. It was part of a broader political and cultural movement shaped by Basque nationalism, particularly the ideas of Sabino Arana, who founded the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV) in 1895. While Arana himself had little interest in painting or sculpture, his romantic vision of a pure, pre-Castilian Euskadi created fertile ground for visual reimaginings of Basque identity.

Artists like Darío de Regoyos, Ramiro Arrue, and José Arrúe began to explore themes rooted in Basque life, history, and symbolism. Their work ranged from realist to stylized, often combining decorative flatness with ethnographic precision. Ramiro Arrue’s paintings, for example, depict peasant festivals, rural labor, and religious processions with geometric clarity and subdued palette—transforming quotidian scenes into icons of identity.

This visual language served multiple functions:

- It affirmed a coherent cultural landscape—one defined by tradition, piety, and rootedness.

- It differentiated the Basque Country from the rest of Spain, not through confrontation but through aesthetic distinction.

- It claimed modernity on regional terms, insisting that one could be both forward-looking and culturally specific.

Not all of this work was politically motivated. Many artists approached Basque subjects with affection but little ideological intent. Yet the wider context made their choices inescapably symbolic. To paint a baserria (farmhouse) or a dance of aurresku was to enter into a charged discourse about who the Basques were, and who they were not.

Museums, galleries, and cultural journals became the mediators of this identity-making. Exhibitions in Bilbao and San Sebastián often framed Basque art as both ethnographic documentation and aesthetic achievement. The Museo de Bellas Artes was careful to maintain a broader curatorial lens, but it inevitably became entangled in the politics of regional pride.

At times, this led to quiet exclusions. Artists who worked outside the regionalist idiom—especially women, abstract painters, or those engaged with broader European avant-garde currents—struggled to find institutional recognition. The Basque canon, like all canons, was a product of cultural gatekeeping.

Tensions between tradition and European modernism

By the 1910s and 1920s, Bilbao’s art world faced a dilemma. On one hand, there was a strong local appetite for regionalist art—works that reflected and affirmed Basque identity. On the other hand, Europe was changing. Cubism, expressionism, futurism, and surrealism were sweeping through Paris, Berlin, and Milan, offering radical new forms of visual thought. Could Bilbao participate in this modernism without betraying its roots?

Some artists tried to reconcile the two. Joaquín Lucarini, a sculptor born in Bilbao, adopted a stylized figuration that flirted with cubist abstraction while retaining monumental clarity. His work in public memorials and civic commissions suggested that modern form could serve traditional content.

Others, like Gustavo de Maeztu, leaned into theatrical symbolism and decorative excess, drawing on both European art nouveau and Iberian baroque heritage. Maeztu’s 1929 painting La batalla de las Navas de Tolosa is a massive, almost operatic canvas that mixes historical allegory with painterly drama. It signaled a desire to compete with Madrid’s national-historical painting on its own terms, but from a Basque perspective.

Yet there was a more radical undercurrent growing. A handful of younger artists, especially those exposed to French and German art schools, began to reject both regionalism and academicism. They sought to create art that was contemporary, critical, and international. But Bilbao in the 1920s and 30s was not yet ready to embrace the avant-garde. Such work found little institutional support, and often ended up exhibited in Madrid or Paris instead.

The museum, caught between conservatism and experimentation, moved cautiously. Its acquisitions remained largely figurative and historical, reflecting the tastes of donors and directors rather than the rumblings of modernity.

But the tension was now set: between an art of belonging and an art of rupture, between the familiar dignity of Basque tradition and the unsettling freedom of modern expression. That tension would explode—with both violence and revelation—in the decades to come.

The Modernist Spark: Zuloaga, Arteta, and the New Figuration

The early 20th century brought a subtle but definitive rupture in the art of Bilbao and the wider Basque Country. It was not a sudden break with the past, but a reconfiguration of its visual priorities. Out of the embers of regionalist painting and historical realism emerged a generation of artists determined to confront modernity directly—without apology and without retreat into folklore. The key figures in this transformation were Ignacio Zuloaga and Aurelio Arteta, two painters whose work embodied different, often conflicting, paths into a new artistic vocabulary. Where Zuloaga chose theatrical myth, Arteta turned to labor and form. Together, they helped push Bilbao into its first genuine encounter with the modern.

Ignacio Zuloaga’s mythic Spain and Bilbao’s ambivalence

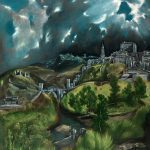

Born in Eibar in 1870, Ignacio Zuloaga was a paradox from the start. Though Basque by heritage and temperament, he found his fame in Madrid and Paris, and his style was a volatile mixture of Velázquez, Goya, El Greco, and French symbolism. His portraits of flamenco dancers, ascetic monks, and defiant bullfighters projected an image of Spain as stoic, archaic, and tragic—a place locked in timeless struggle with fate and beauty.

Zuloaga’s work was magnetic, especially for European collectors who saw in it a raw, exotic Spain untouched by modern progress. But in Bilbao, his reception was mixed. His vision of Spanish identity—Andalusian, mystical, proud—did not always sit easily with Basque sensibilities, which were increasingly industrial, rationalist, and politically separatist. And yet, Zuloaga’s technical brilliance and emotional force could not be ignored.

His paintings did occasionally touch on Basque themes. El abuelo (1904), for instance, portrays a wizened patriarch in black beret, surrounded by grandchildren, set against a stark landscape of stone and cloud. It’s both affectionate and monumental, capturing a sense of ancestral gravity without sentimentality. But Zuloaga was never truly of Bilbao. His emotional allegiance remained elsewhere—in the dust and drama of Castile, in the moral chiaroscuro of pre-modern Spain.

Nonetheless, his international success forced Basque artists to rethink their ambitions. Zuloaga had shown that a painter from northern Spain could command global attention, provided he crafted a mythology strong enough to transcend regional confines. That lesson would not be lost on Aurelio Arteta.

Aurelio Arteta and the working-class sublime

If Zuloaga painted myth, Aurelio Arteta painted the real. Born in Bilbao in 1879, Arteta studied in Paris and Milan, absorbing the lessons of post-impressionism and symbolism before returning to the Basque Country with a fierce commitment to painting the modern condition. He became, in effect, the visual conscience of Bilbao during its industrial ascent.

Arteta’s great innovation was to fuse classical compositional structure with contemporary subject matter. His workers, miners, and dockhands are rendered with the dignity and rhythm of a Renaissance frieze—but they inhabit the mud, steel, and sorrow of 20th-century industry. In works like Los obreros (1912) and El hombre del carro (1920), we see anonymous figures silhouetted against factories and loading docks, their bodies heavy with fatigue yet composed with almost sculptural grace.

This fusion of heroic form and social realism gave Arteta’s paintings a unique gravitas. He was neither a sentimentalist nor a propagandist. His workers are not victims or martyrs; they are participants in a collective, arduous drama—a drama shaped not by ideology, but by material necessity.

One of his most haunting works, Tragedia del Mar (1926), shows a line of grieving women in profile, each cloaked in black, their faces hidden. The composition recalls Giotto, but the subject is local: a fishing disaster on the Basque coast. The painting is devoid of action, yet saturated with moral weight. Grief is monumentalized, made timeless.

In 1933, Arteta was appointed director of the Museo de Arte Moderno in Madrid. Three years later, the Spanish Civil War broke out. He sided with the Republic, was imprisoned after its defeat, and eventually died in exile in Mexico in 1940. His death marked not only the loss of a major painter, but the interruption of a moral tradition in Basque art—one that sought dignity not in history or myth, but in the unadorned fact of labor.

From rural ideal to urban anxiety in early 20th-century works

The arrival of modernism in Bilbao coincided with an increasingly unstable relationship between the countryside and the city. For centuries, Basque visual identity had leaned on rural motifs—farmhouses, shepherds, religious festivals, and seasonal rituals. These images, popularized by the Arrúe brothers and reinforced through decorative arts and print culture, offered a comforting idea of permanence.

But by the 1920s and 30s, the city had overtaken the village as the dominant cultural reference. Bilbao’s population was exploding. Immigrants from other parts of Spain crowded into its industrial zones. Strikes, protests, and class conflict became regular features of the urban landscape. The old rural images began to feel inadequate, or even dishonest.

This shift can be felt in the work of Julián de Tellaeche, an often-overlooked painter who experimented with psychological interiors and urban symbolism. His 1935 canvas La ciudad dormida shows Bilbao as a surreal, disjointed geometry of shadows and arches—part De Chirico, part industrial nightmare. It’s not realism, but it reflects a new emotional reality: anxiety, dislocation, and the sense that tradition was no longer enough.

The press, too, became a visual forum. Illustrated magazines like Estampa and La Esfera began to publish photo essays and sketches of factory life, slum conditions, and civic events. These images created an alternative archive of urban modernity, one that often eluded the canvases hanging in museums.

By the time the Spanish Civil War erupted in 1936, Bilbao’s art world had fractured. The regionalist idyll was exhausted. The modernist experiment was under siege. The city itself—once a promise of economic power and cultural ambition—was being bombed by German aircraft at the request of the National Socialist-aligned Francoist forces. Art would survive, but it would never be the same.

What Zuloaga began—mythic isolation—and what Arteta affirmed—working-class formality—had opened the way for a new kind of visual seriousness in Basque art. But war, exile, and censorship would soon scatter the generation that had made Bilbao modern.

War, Exile, and Rupture: Art under Franco and Beyond

The Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) and the ensuing decades of Francoist dictatorship dealt a profound and multifaceted blow to the artistic life of Bilbao. It was not only the physical destruction—though Bilbao was bombed, its intellectual networks shattered, and its institutions hollowed—but also the severing of artistic continuity. The war uprooted a generation of artists, destroyed nascent movements, and reshaped the terms of what could be expressed, shown, or even imagined. For Basque art, the mid-20th century was an age not of silence, but of coded expression, scattered voices, and survival beneath constraint.

Repression and survival of artists in postwar Bilbao

After Franco’s victory in 1939, the Basque Country found itself in a state of political and cultural suffocation. The new regime outlawed the Basque language, shuttered local institutions, and imposed a highly centralized, Castilian-centric ideology on the country. For artists in Bilbao, the consequences were immediate and brutal. Censorship, economic hardship, and ideological surveillance made public artistic life nearly impossible for anyone who did not conform.

Aurelio Arteta, the towering figure of Basque social realism, died in Mexican exile shortly after the war. His absence left a vacuum not only of talent but of vision—there was no one of his stature left in Bilbao to carry forward the tradition of painting grounded in human dignity and civic compassion. Younger artists, trained in the 1930s, faced a grim choice: adapt to the new official aesthetic of sanitized nationalism, or risk silence and marginalization.

The Franco regime promoted a retrograde, moralizing art rooted in Catholic symbolism and historical idealism. State-sponsored exhibitions favored depictions of saints, battle scenes, or pastoral calm—works designed to pacify, not provoke. In this climate, the idea of Basque modernism—already embattled before the war—became all but unspeakable.

Yet even in repression, art persisted, often in the margins. A small number of artists in Bilbao continued to work quietly, privately, sometimes within the constraints of religious commissions or decorative arts. They experimented with abstraction under the guise of stained glass design, explored modernist composition in church murals, or smuggled critical content into landscapes and still lifes. The postwar years created a visual culture of strategic ambiguity, where metaphor and material often spoke louder than overt subject matter.

Some painters survived by internal exile, remaining in Bilbao but refusing public exposure. Others lived double lives—producing commercial illustrations by day, while painting or sculpting personal work in private studios at night. This clandestine creativity—half-visible, half-deniable—gave rise to a unique mode of visual language: oblique, compressed, layered with tension. It was art designed to outlast the regime, not to confront it directly.

Artistic exile and the Basque diaspora’s cultural role

While many artists remained in Spain under pressure, others chose or were forced into exile. Mexico, Argentina, and France became critical nodes in the Basque artistic diaspora. Among them were sculptors, illustrators, architects, and writers who carried fragments of prewar Bilbao with them—memories of industrial modernity, political hope, and cultural ambition. These fragments did not remain frozen. They evolved, cross-pollinated, and adapted to new contexts.

Perhaps the most emblematic figure of Basque exile in the arts was José María de Ucelay, a painter who left Spain for Paris and later South America. His style—marked by restrained surrealism, psychological interiors, and delicate still lifes—became increasingly introspective in exile. He returned to Bilbao in the 1950s, disillusioned, and produced a series of works that seem haunted by absence: empty chairs, closed windows, fragments of architecture rendered with forensic precision but drained of presence. These paintings do not depict exile directly; they inhabit its mood.

In Argentina, Basque cultural centers became hubs not only for political organizing, but for artistic exchange. Exhibitions of Basque painting, even if limited in scale, helped sustain a sense of identity disconnected from Francoist Spain. Artists collaborated with poets, musicians, and educators to keep alive a non-official version of Basque visual culture, one rooted in memory, resistance, and formal experimentation.

Exile also meant freedom from the limitations of Spanish censorship. Artists could engage more openly with international movements—surrealism, abstract expressionism, constructivism—without fear of reprisal. In doing so, they created a parallel genealogy of Basque art, one that would later feed back into Bilbao after the death of Franco in 1975.

Three thematic threads emerged across the diaspora’s visual output:

- Displacement: recurring motifs of journey, rootlessness, and return.

- Fragmentation: compositional breaks, surreal juxtapositions, and collage aesthetics.

- Mourning and memory: a visual ethics of recollection, often tied to war, loss, and identity.

This art did not romanticize exile; it lived within its dissonances. In some cases, the act of art-making itself became a form of psychic repair—a way to reassemble meaning in the absence of nation, language, or home.

Symbolism, abstraction, and coded resistance

While open resistance through art was impossible under Franco, Bilbao’s artists developed sophisticated methods of visual encryption. Abstraction—dismissed by the regime as incomprehensible or foreign—became a safe haven for experimentation. In the 1950s and 60s, a growing number of artists began to move away from figurative painting toward a language of line, mass, texture, and space that could evade the censors while still expressing political and emotional intensity.

Jorge Oteiza, though more closely associated with Gipuzkoa than Bilbao proper, was instrumental in this shift. His sculptural practice fused existential philosophy, spatial geometry, and Basque metaphysics into a body of work that defied easy interpretation. His “Emptying of Form” series—minimalist blocks of volcanic stone with negative voids carved into them—rejected monumentality in favor of introspective absence. For Oteiza, abstraction was not merely a stylistic choice; it was a mode of cultural survival, a way to express Basqueness without resorting to ethnographic cliché.

Though he spent much of his time outside Bilbao, his ideas resonated deeply in the city. A younger generation of artists—painters, sculptors, and designers—began to apply similar principles in their work: balancing reduction and symbolism, using texture and repetition as a form of encrypted speech.

Eduardo Chillida, another sculptor often associated with the broader Basque Country, likewise developed a formal vocabulary rooted in industrial material and existential inquiry. His use of iron, alabaster, and corten steel—materials intimately tied to Bilbao’s industrial past—transformed raw matter into profound spatial metaphors. His pieces, while ostensibly non-political, embodied a quiet defiance: they insisted on the value of thought, space, and form in a regime built on coercion and uniformity.

This era also saw the quiet emergence of women artists, though their work remained largely outside the institutional spotlight. Figures like Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, though Portuguese by nationality, exhibited in Bilbao and influenced local trends in gestural abstraction and structural ambiguity.

What connected these disparate artists was not a shared movement or manifesto, but a common condition: the need to create under surveillance, the obligation to speak without saying, and the desire to maintain a visual integrity in an age of lies.

By the 1970s, as the Franco regime entered its final years, the cracks in its cultural edifice had widened. New exhibition spaces, cooperative galleries, and underground publications began to reintroduce Bilbao’s artists to international currents. But the legacy of rupture remained. A generation had been lost to war, exile, and silence. The survivors carried its marks—not as scars, but as materials.

They were, in effect, preparing the ground for a Basque artistic renaissance, one that would explode after 1975, when art could finally re-enter the streets, the schools, and the public imagination without fear.

Rebuilding Aesthetic Futures in the 1960s and 70s

The final decade of Franco’s rule and the first years of democratic transition saw Bilbao undergo not just political upheaval, but an artistic reawakening. While repression had stifled cultural production in earlier decades, the 1960s and 70s brought a remarkable flowering of creative energy, experimentation, and intellectual risk. It was not a restoration of prewar traditions, but the emergence of new aesthetic languages—rooted in abstraction, conceptualism, and critical engagement with place and identity. Out of the ashes of exile and silence came a generation of artists who sought not merely to make art, but to remake the very conditions of visibility in a city—and a country—waking from authoritarian sleep.

Grupo Gaur and the Basque avant-garde

No discussion of Basque artistic resurgence in this period is possible without Grupo Gaur, founded in 1966 in Gipuzkoa but with deep resonance in Bilbao. Though Bilbao was not its formal birthplace, the group’s ideas and influence radiated quickly across the Basque Country, galvanizing artists from San Sebastián to Bilbao and beyond.

Gaur (“Today” in Basque) was less a stylistic school than a shared rebellion. Its members—among them Jorge Oteiza, Eduardo Chillida, Amable Arias, and Nestor Basterretxea—rejected both the folkloric regionalism of the 1940s and the conservative academicism still dominant in Spanish state institutions. What united them was a belief that modern art could—and must—engage with Basque specificity, but without surrendering to cliché or nostalgia.

They worked in a range of media—sculpture, painting, architecture, graphic design—and pursued a visual vocabulary that was abstract, structural, and symbolic, drawing on both international modernism and Basque metaphysics. Oteiza’s sculptural theories about the “emptying of form” became a kind of aesthetic cornerstone for the group: a vision of art as spatial thinking, as reduction, as material thought stripped to its essentials.

Though Gaur’s center of gravity lay slightly east of Bilbao, its impact there was profound. Bilbao artists responded by forming their own collectives, exhibitions, and critical publications. What had been a fragmented postwar field began to cohere into a networked avant-garde—connected not only by aesthetic values, but by shared political risk.

Art was no longer safe. To exhibit abstraction, to quote existentialist texts, to use Basque titles or symbols—these were acts of defiance, especially under the eyes of censors still loyal to the dying regime. But the boldness of Gaur emboldened others. It signaled a break with inherited styles and an insistence on the contemporary, rooted in place but reaching outward.

Sculpture, land art, and the industrial landscape

One of the most defining developments of Bilbao’s late 20th-century art was the shift toward sculpture and spatial intervention. In a city dominated by steel, machinery, and mineral extraction, the three-dimensional became a site of symbolic contestation. Iron, previously a material of labor and control, was reimagined as a medium of poetic form.

Eduardo Chillida, though based in San Sebastián, exhibited frequently in Bilbao and influenced its sculptural culture deeply. His massive works—like Lugar de encuentros (1971)—positioned sculpture as an encounter between mass and void, between the human body and the forces of landscape and geometry. Chillida’s use of corten steel and oxidized iron echoed the industrial tones of Bilbao’s riverbanks and factories, recontextualizing them as philosophical spaces.

Meanwhile, artists like Txomin Badiola and Ángel Bados began to explore the relationship between sculpture, installation, and site-specificity. Badiola’s early constructions, often composed of salvaged materials and industrial detritus, invoked the aesthetic of ruin: not to mourn Bilbao’s industrial decay, but to ask what new forms could be built from its remnants.

In this period, Bilbao became a kind of laboratory for land art and urban intervention. The post-industrial voids—vacant lots, disused docks, abandoned shipyards—offered new terrain for experimentation. Temporary sculptures, outdoor performances, and ephemeral installations challenged the museum as the only legitimate site of artistic display.

A landmark moment came with the 1976 Festival de Arte en la Calle (Art in the Street Festival), where artists staged actions, interventions, and exhibitions in public space—often without official permission. These acts were not simply aesthetic gestures; they were declarations that art belonged to the people, to the streets, to the city in flux.

Three themes dominated this sculptural and spatial turn:

- Material honesty: iron, concrete, wood—unvarnished, unpainted, unmasked.

- Site integration: artworks that responded to specific urban or natural conditions, not white-walled abstraction.

- Human scale: even in monumentality, the body was the measure—spaces to walk through, lean against, inhabit.

This rethinking of scale, matter, and place would later lay the groundwork for Bilbao’s most famous architectural moment: the construction of the Guggenheim. But in the 1960s and 70s, these experiments were still formally modest and conceptually radical, carried out in garages, cooperatives, and open lots.

Conceptual practices and Basque identity politics

As sculpture pushed into new terrains, painting and mixed media also underwent transformation. A wave of conceptual and semiotic practices emerged—art that was not about image-making but about ideas, processes, and symbols. Many of these artists, shaped by the legacy of exile and censorship, turned toward coded references, visual puns, and language-based work that danced around the edge of legibility.

One such artist was Joxemari Iturralde, whose conceptual installations played with linguistic ambiguity and spatial uncertainty. His works questioned not only what art could look like, but how meaning could be constructed, deconstructed, and performed. In a city where Basque identity had been repressed for decades, the act of using the Basque language, even indirectly, became a political act.

This generation was deeply influenced by structuralist and post-structuralist theory—Barthes, Foucault, Derrida—but also by Basque oral traditions, folk rituals, and ancestral symbolism. They sought to build a new semiotics of Basqueness, one that was neither folkloric nor nationalist in the traditional sense, but attuned to complexity, multiplicity, and irony.

Women artists also began to assert themselves more visibly during this period, often through photography, textile, and performance. Their work challenged not only Francoist patriarchy, but the male-dominated Basque avant-garde itself. Itziar Okariz, in particular, began to explore performance and body-based work that would become central in the post-transition era. Though her most influential pieces came later, her early experiments in language, gesture, and taboo were rooted in the ferment of the 1970s.

Importantly, these conceptual practices did not isolate themselves from politics. The last years of the Franco regime saw intensifying demands for Basque autonomy, as well as the rise of ETA as a militant force. Art was not immune to these tensions. Some artists aligned themselves with activist causes, while others sought to maintain critical distance. But the language of resistance—symbolic, visual, gestural—infused the work of the era with urgency.

By 1975, the death of Franco cracked open the cultural field. Censorship lifted. Exhibitions multiplied. The Euskadi language law of 1979 restored legal protections to the Basque tongue. The streets filled with murals, protests, celebrations—and art. After decades of fragmentation, Bilbao’s artists were once again visible, audible, and public.

But this visibility came with a question: What kind of city would Bilbao become? A cultural capital, a post-industrial ruin, a radical experiment? The artists of the 60s and 70s had laid the conceptual and material groundwork—but the shape of the future was still unwritten.

The Bilbao Effect Before the Guggenheim

The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao opened its titanium petals to the world in 1997, but the city’s transformation into a cultural capital did not begin with Frank Gehry’s architecture. Long before global headlines coined the phrase “The Bilbao Effect,” artists, institutions, policymakers, and independent curators had been laying the groundwork for the city’s cultural reinvention. This pre-Guggenheim period—roughly from the early 1980s to the mid-1990s—was a complex terrain of decline and experimentation, civic ambition and institutional improvisation. In many ways, the Guggenheim’s arrival was less a rupture than a culmination.

Cultural policy and urban decline in the 1980s

In 1983, Bilbao was devastated by one of the worst floods in its modern history. The Nervión overflowed and submerged the city center, destroying homes, businesses, and archives. In symbolic terms, the flood seemed to confirm what many already feared: that Bilbao’s industrial engine was failing, and with it, its civic identity.

The late 1970s and early 1980s had brought deindustrialization, massive layoffs, labor unrest, and rising urban poverty. Shipyards closed. Mines went quiet. The docks that once hummed with iron and coal stood idle. The physical infrastructure of the city—bridges, railways, warehouses—became markers of economic loss rather than pride.

In response, a new generation of local officials and cultural figures began to envision a different future for Bilbao. They saw in culture not just a symbolic good, but a potential engine of regeneration. Under the Basque autonomous government, created after the 1979 Statute of Autonomy, significant public funds were directed toward cultural infrastructure, heritage preservation, and the arts.

But this shift was not immediate, nor did it begin with museums. The 1980s saw a proliferation of community arts centers, artist-run spaces, and municipal festivals designed to reclaim public space and social cohesion. Initiatives like the Semana Grande (Aste Nagusia), although rooted in local tradition, began to take on broader cultural dimensions, incorporating experimental theatre, avant-garde music, and multimedia installations.

In visual art, the strategy was multi-pronged:

- Restoration: investing in historic buildings and artworks, often as part of tourism-oriented urban beautification.

- Education: funding art schools, workshops, and youth programs to expand access to creative skills.

- Incubation: supporting galleries and cooperatives that could provide alternative exhibition spaces outside the traditional museum system.

One of the pivotal actors during this period was Bilbao Bizkaia Kutxa (BBK), a savings bank that directed part of its surplus into cultural grants, sponsorships, and gallery support. BBK’s cultural arm became one of the most consistent funders of emerging artists in the region, offering not only money but venues in which to show work.

Though these developments were modest in scale, they gradually shifted the cultural narrative of Bilbao: from a city in mourning to one in search of expression.

The rise of ARTIUM and new exhibition models

While the Museo de Bellas Artes remained the city’s primary art institution throughout the 1980s, it was increasingly seen as conservative and somewhat insulated from the contemporary scene. Its collections were strong in classical and 19th-century Spanish art, but slow to embrace postwar and experimental practices.

The real dynamism came from new platforms—some public, some private—that reimagined how and where art could be seen. Chief among these was the ARTIUM initiative, centered in Vitoria-Gasteiz but with strong ties to Bilbao and the broader Basque network. Though ARTIUM did not open its permanent space until 2002, its itinerant exhibitions, archives, and partnerships were already active in the 1990s, helping to connect Basque artists with international trends.

These exhibitions introduced Bilbao’s audiences to a broader visual vocabulary:

- Conceptual installations by artists like Txomin Badiola and Cristina Iglesias, who challenged the boundary between sculpture and architecture.

- Video and media art, often politically charged, reflecting on post-Franco identity and the wounds of the Civil War.

- Post-minimalist painting, with a renewed focus on process, surface, and material instability.

What distinguished ARTIUM’s model was its refusal to centralize culture in a single monumental institution. Instead, it treated art as a distributed ecology: something that could happen in storefronts, libraries, plazas, and repurposed industrial sites.

This ethos resonated with Bilbao’s urban reality. With so many buildings vacant and infrastructure in flux, artists had room to experiment—and municipal leaders, eager for revitalization, were often willing to look the other way. Squatted warehouses became studios. Disused port facilities hosted temporary exhibitions. Art began to creep into the city like water into stone.

One of the most important spaces of the period was Galería Windsor Kulturgintza, which opened in 1984 and quickly became a hub for contemporary art in the city. It championed local and international artists, embraced politically difficult work, and resisted the commodification of art as spectacle. In a sense, it anticipated what Bilbao would later become—but without the fanfare or architectural flourishes.

Local galleries as incubators of experimentation

Beyond ARTIUM and municipal initiatives, independent galleries played a crucial role in sustaining artistic life during the 1980s and early 1990s. These were not merely commercial enterprises; they were part salons, part archives, part resistance movements.

Galería Vanguardia, founded in 1982, was instrumental in promoting a generation of artists whose work defied both market conventions and institutional orthodoxy. Its programming included performance art, experimental photography, and cross-genre collaborations. It also served as a meeting ground for artists, theorists, and curators—a space where debates about Basque identity, global aesthetics, and political responsibility could take shape.

These galleries operated under financial strain but creative abundance. They hosted exhibitions on shoestring budgets, printed zines and catalogues in-house, and often relied on the labor of artists themselves to install and publicize shows. Yet they provided essential infrastructure for artistic maturation. Many of the artists who would later achieve international recognition—Cristina Iglesias, Sergio Prego, Javier Pérez—passed through these spaces early in their careers.

Three defining characteristics of Bilbao’s gallery culture in this period:

- Collective labor: exhibitions organized not just by curators, but by artist cooperatives and informal networks.

- Multidisciplinarity: shows that included sound, text, video, and installation—long before this was mainstream.

- Critical dialogue: a refusal to treat art as commodity or decoration, and a consistent engagement with historical memory, political violence, and regional identity.

This scene was precarious. Funding was inconsistent. Venues came and went. But its resilience was remarkable. Even as the city struggled with economic despair, its artistic life continued to evolve—not because of state initiative, but through grassroots reinvention.

By the mid-1990s, Bilbao had acquired a new self-image: no longer just a post-industrial city, but a place where art could happen in the interstices—between docks and museums, between past and future, between ruin and possibility.

And then came the Guggenheim.

But to understand what that building meant—to Bilbao, to art, to the world—it is essential to remember: the spark was already there.

Guggenheim Bilbao: Shock, Spectacle, and Skepticism

When the Guggenheim Bilbao opened in October 1997, the city became an instant byword for cultural reinvention. The building itself—Frank Gehry’s flowing titanium curves, planted improbably along the gray banks of the Nervión—was hailed as a miracle, a rupture, a turning point in both architecture and urbanism. It was described as the most important structure of its kind since the Sydney Opera House. International press coined a phrase to describe the phenomenon: The Bilbao Effect. It would enter the lexicon of city planners and museum boards from Seoul to São Paulo.

But the Guggenheim was not a miracle. It was a decision—a high-stakes, ideologically loaded, financially ambitious bet made at a very specific moment in Bilbao’s history. And while its global impact is undeniable, the building also provoked intense local ambivalence, raising uncomfortable questions about authorship, authenticity, and the role of art in urban life.

Gehry’s architecture and the global gaze

Frank Gehry’s design for the Guggenheim Bilbao was unlike anything Spain—or Europe—had seen. Rather than imitate historical styles or blend discreetly into the cityscape, the museum appeared to defy gravity, context, and tradition. Its form—swooping, shimmering, asymmetrical—suggested movement more than stasis, like a ship in perpetual launch or a fish caught mid-turn. The material—over 33,000 thin titanium panels—was chosen for its mutability, its ability to shift with the light and weather, turning silver to gold, dull to radiant.

The site, too, was carefully chosen. Once part of Bilbao’s shipbuilding and port infrastructure, it had become a desolate tract of concrete and rust. Placing the museum there was not only symbolic—it was strategic urban acupuncture. The building did not replace the city’s industrial past; it embedded itself in it, transforming ruin into icon.

The Guggenheim was a collaboration between the Basque government and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation in New York, which had been seeking to expand its global footprint. Under the leadership of Thomas Krens, the Foundation envisioned a network of museums as a cultural franchise—branded experiences that could blend high art and architectural spectacle into a new form of mass attraction.

Bilbao offered something rare: a government willing to invest heavily (over $100 million in public funds), provide long-term operating subsidies, and cede curatorial authority in exchange for a place on the international cultural map. It was, in effect, a calculated risk: leverage the prestige of the Guggenheim brand to catalyze tourism, real estate investment, and urban renewal.

The gamble paid off—at least by the numbers. Within a year of opening, the Guggenheim attracted over a million visitors. It spurred the construction of new hotels, restaurants, public transit, and riverwalks. Unemployment fell. The city’s image shifted almost overnight: from post-industrial backwater to global design capital.

But the very features that drew global admiration—the building’s otherworldly form, its foreign authorship, its marketing sheen—also triggered skepticism at home.

How the Guggenheim altered artistic ecosystems

For Bilbao’s local art scene, the arrival of the Guggenheim was both boon and disruption. On one hand, it brought unprecedented attention to the city. International curators, collectors, and critics began to visit. Infrastructure improved. Funding increased. Young artists suddenly had access to residencies, studio space, and grant programs that had not existed a decade earlier.

But the museum itself was never designed to showcase Basque or Spanish artists. Its collection, drawn primarily from the holdings of the Guggenheim Foundation, emphasized canonical 20th-century figures: Kandinsky, Rothko, Warhol, Serra, Koons. Its programming focused on blockbuster exhibitions with global appeal. Local artists often found themselves as spectators rather than participants.

In the early years, some effort was made to include regional voices. A 1999 exhibition, Gure Artea (Our Art), featured a cross-section of Basque contemporary work. But such initiatives remained occasional, and rarely took center stage. The Guggenheim was not a Basque institution. It was a transnational brand planted in Basque soil.

This created a kind of cultural bifurcation. On one side, the museum and its global programming; on the other, the local art world—studios, cooperatives, small galleries—still shaped by grassroots energy and conceptual experimentation. While some artists managed to straddle the divide, many felt that the Guggenheim’s presence had flattened the city’s artistic ecology, distorting funding priorities and public attention toward spectacle rather than substance.

One of the most striking tensions lay in material. While Bilbao’s 1980s artists had worked with iron, found objects, and decaying infrastructure—an art of immediacy and site—the Guggenheim trafficked in high-polish fabrication, monumental scale, and controlled environments. The industrial rawness of Bilbao’s art history was recoded into luxury modernism.

There were exceptions. Richard Serra’s The Matter of Time (2005), permanently installed in the museum’s vast lower gallery, resonated deeply with Bilbao’s sculptural legacy. Serra’s use of torqued steel, his interest in bodily scale and spatial disorientation, echoed the concerns of Oteiza and Chillida. But Serra was a New Yorker. His work arrived already canonized.

Meanwhile, local artists struggled to find space—not just physical, but conceptual—within the new cultural order.

Critiques, contradictions, and long-term consequences

From the outset, the Guggenheim project drew fierce criticism from certain quarters. Urbanists, sociologists, and cultural critics questioned the logic of top-down cultural development. Why pour resources into a signature museum while neighborhood cultural centers languished? Why import curatorial leadership when Bilbao had its own rich artistic networks?

Some of the most trenchant critiques came from within the Basque art community itself. Artist Txomin Badiola, for example, lamented what he called the “iconification of culture”—the transformation of art into a visual economy of prestige rather than a space of thought. Others pointed out the political irony: that a city long shaped by labor struggles, artistic collectivism, and resistance to centralized authority had become a poster child for corporate culture-driven regeneration.

Yet for all its contradictions, the Guggenheim also forced a reckoning. It made visible the gaps between global cultural capital and local practice. It challenged Bilbao’s artists and institutions to think bigger, to refine their arguments, to define themselves in relation to a global audience.

Over time, Bilbao’s cultural infrastructure began to adapt. The Museo de Bellas Artes underwent a major renovation and expanded its modern and contemporary holdings. Independent galleries adjusted their programming to include more international collaborations. Artist residencies and education programs multiplied. The Basque government, recognizing the risks of monoculture, increased its support for non-Guggenheim institutions.

Three enduring impacts of the Guggenheim’s arrival:

- Civic ambition: culture became a central axis of urban policy, with long-term commitments to public art, education, and design.

- Narrative shift: Bilbao’s image changed—from gritty port to creative capital—attracting new populations and investments.

- Symbolic tension: the museum remains a site of unresolved contradiction, both admired and critiqued, embedded and aloof.

Today, it is possible to stand in the Guggenheim’s vast atrium, gaze up at Gehry’s cascading forms, and feel both awe and unease. The building is beautiful. It is also a monument to the double-edged power of culture—its ability to transform, to seduce, to displace, to inspire.

The question is not whether the Guggenheim “succeeded.” It did. The better question is: what kind of cultural success is sustainable, meaningful, and shared? That question would shape the next two decades of Bilbao’s artistic life.

A City of Sculptures: Public Art and Urban Transformation

Bilbao’s transformation into a “cultural city” did not stop at the titanium shell of the Guggenheim. In the decades surrounding its opening, the city became a sprawling open-air gallery—a place where art left the museums and entered the public domain with unprecedented scale and visibility. Parks, plazas, roundabouts, and riverwalks began to fill with sculptures and installations, many of them created by artists with deep connections to the Basque Country. Far from decoration, these interventions formed a new visual and symbolic infrastructure: art as urban grammar.

Eduardo Chillida and the monumental mode

No figure looms larger—literally and metaphorically—in Bilbao’s sculptural landscape than Eduardo Chillida. Born in San Sebastián in 1924, Chillida was already an internationally celebrated artist by the 1980s, but his work never lost its rootedness in Basque materiality and philosophy. His preferred medium was iron—oxidized, massive, textured—and his formal language drew from both modernist abstraction and prehistoric monumentality. Though Chillida’s most iconic work, Peine del Viento, sits in his hometown, his influence shaped Bilbao’s approach to public sculpture in lasting ways.

In Bilbao, Chillida’s monument to José Antonio Aguirre (1982), the first Lehendakari (president) of the Basque Autonomous Community, occupies a quiet but charged space in the city’s Parque de Doña Casilda. The sculpture is unassuming at first glance: a dense block of granite pierced by a void. But that void—what Chillida called “interior space”—functions like a spiritual corridor, inviting contemplation rather than declaration. It marks presence through absence, memory through material.

Chillida’s work offers a model for public sculpture that is non-narrative, non-heroic, and anti-decorative. He rejected figuration, avoided didacticism, and never worked from a sketch or maquette. Instead, his pieces grew from a dialogue between material resistance and spatial intuition. This ethic suited Bilbao, a city whose identity was forged not in opulence but in labor, weight, and raw form.

His legacy is visible not only in his own public works, but in the tone they set: a seriousness of form, a trust in material, and a refusal to reduce public art to ornament or propaganda.

Jorge Oteiza’s legacy and minimalist interventions

Where Chillida sculpted presence, Jorge Oteiza sculpted absence. The intellectual force behind much of the Basque avant-garde, Oteiza was a theorist as much as an artist—a man who spoke of voids, metaphysics, and spatial ethics with both passion and precision. His early experiments with hollow volumes, spatial rhythm, and chromatic limitation laid the groundwork for a minimalist tradition in Basque public art that prized silence over spectacle.

Oteiza’s influence in Bilbao is indirect but profound. Though most of his public works are located elsewhere, his ideas shaped the aesthetic of the artists and architects who populated the city’s public spaces after 1997. In contrast to the brash monumentalism of imported works—like Jeff Koons’ Puppy or Louise Bourgeois’ Maman—Oteiza’s legacy encouraged subtlety, geometry, and place-awareness.

One of the most important inheritors of his mode is Agustín Ibarrola, whose Bosque de Oma (Oma Forest), while outside Bilbao proper, exemplifies this sensibility: a fusion of land, symbol, and modest intervention. Painted trees form optical illusions only visible from certain angles. It is art as spatial riddle—intimate, site-specific, and humble in scale.

In the city itself, Oteiza’s approach can be seen in works like *Néstor Basterretxea’s Memoria de los Fueros (1980), a tall abstract sculpture of twisting iron rising near the provincial council building. It references historical Basque legal traditions (fueros) not through symbols or inscriptions, but through the tension of curved planes—law rendered as dynamic form.

Three characteristics distinguish Oteiza-influenced public art in Bilbao:

- Anti-iconic forms: shapes that resist easy interpretation or narrative identification.

- Spatial ethics: works that activate, rather than dominate, their surroundings.

- Material modesty: preference for local stone, steel, and wood over imported gloss.

This quieter current in Bilbao’s public art balances the flashier gestures of global contemporary sculpture and remains a crucial thread in the city’s visual language.

Art as civic infrastructure, from Zubizuri to Puppy

Of course, not all public art in Bilbao follows the Chillida-Oteiza lineage. Some of it is flamboyant, populist, or architectural in ambition. In the wake of the Guggenheim’s success, the city embraced a new wave of iconic structures and art-architecture hybrids, often created by internationally renowned figures.

One of the most controversial is Santiago Calatrava’s Zubizuri (Basque for “white bridge”), completed in 1997. A sleek footbridge of glass bricks and steel cables, it was intended as a symbol of modern Bilbao: light, aerodynamic, forward-looking. But locals complained about its slipperiness in the rain, the cost of maintenance, and its incompatibility with new infrastructure. The bridge became a battleground between aesthetic ambition and civic practicality.

More enduring in public affection is Jeff Koons’ Puppy, the towering West Highland terrier covered in live flowers that sits guard outside the Guggenheim. Commissioned as a temporary piece for the museum’s opening, it was so popular that it became permanent. Puppy is the antithesis of Chillida: decorative, kitsch, unashamedly sentimental. But it works. It bridges generations, draws in the skeptical, and softens the museum’s intimidating exterior with a dose of levity.

And then there is Louise Bourgeois’ Maman (2001), a 30-foot bronze spider perched near the riverfront, its spindly legs framing views of the Guggenheim. Where Puppy offers comfort, Maman offers unease: an evocation of maternal power, memory, and ambivalence. Its placement near the museum suggests a shift in Bilbao’s cultural self-image—from masculine labor and industry to something more intimate, psychological, and open to contradiction.

This fusion of infrastructure and installation is one of the defining features of 21st-century Bilbao. Public art is no longer confined to plinths or corners; it is integrated into bridges, plazas, transit hubs, and parks. In some cases, it has replaced monuments of conquest or martyrdom. In others, it coexists with them, forming a visual palimpsest of competing histories.

Critics of Bilbao’s public art strategy argue that it has become too curated, too marketable—a kind of outdoor showroom for global sculpture. There’s truth in that. But it’s also true that the city has succeeded in something rare: creating a public sphere where art is not an afterthought, but part of the civic experience.

You can walk along the river and encounter works by Serra, Koons, Chillida, Oteiza, and Basterretxea within a mile of each other. You can cross bridges that are also sculptures, sit on benches that double as installations, and attend festivals where performances spill into the street. Art is not behind glass. It’s in the way.

In this sense, Bilbao has fulfilled one of the deepest ambitions of public art: to make aesthetic experience part of everyday life, not a rarefied privilege. The question, as always, is what comes next—how to keep that experience vital, accessible, and responsive to the city’s evolving needs.

Contemporary Basque Voices and Global Currents

By the early 21st century, Bilbao’s art scene had fully emerged from the shadows of industrial collapse and cultural marginality. It now occupied a paradoxical space: globally visible, thanks to the Guggenheim; locally energized by decades of underground practice and institutional growth. Yet what distinguishes the current moment in Bilbao is not its institutions or its architectural icons, but its artists—a cohort of creators working across mediums, languages, and continents to articulate what it means to make art in and beyond the Basque Country today.

These artists are neither provincial nor rootless. They are engaged with the traditions of Chillida and Oteiza, but also with the conceptual legacies of postmodernism, the decolonial turn in global art discourse, and the urgent politics of gender, technology, and ecological precarity. Their work is not unified by style but by a common refusal to be reduced—to folklore, to market logic, to identity branding.

Women artists and shifting narratives

For much of the 20th century, the story of Basque art—like so many others—was written almost entirely by men. Even the radicalism of the 1960s and 70s avant-garde was often gender-exclusive, focused on formal innovation rather than structural equity. That began to change in the 1990s, and by the 2010s, women artists had become some of the most prominent and critically engaged voices in Basque contemporary art.

Cristina Iglesias, born in San Sebastián but exhibiting frequently in Bilbao, is among the most internationally acclaimed. Her architectural installations—fountains, corridors, cast-metal foliage—create spaces of illusion and meditation. Works like Deep Fountain (2009), installed in a plaza outside the Museo de Bellas Artes, blur the line between sculpture and environment. Water emerges and recedes from a patterned steel grate, suggesting time, memory, and erasure. Iglesias’s work is resolutely non-literal, but suffused with emotional gravity.

Another vital figure is Itziar Okariz, whose performance-based practice interrogates language, gender, and bodily protocol. In one of her early works, To Pee in Public and Private Spaces, Okariz urinated in various urban settings, exploring norms of visibility, shame, and control. These acts, documented through video and text, position the body as both agent and subject of sociopolitical forces. Her work has a stripped-down formal clarity, but its implications—on regulation, transgression, and the gendered city—are far-reaching.

Beyond these internationally known names, a new generation of artists—Ainhoa Resano, Saioa Olmo, Esther Ferrer (though born earlier, her influence grew in later decades)—has expanded the field of what Basque art can be. Working in sound, installation, participatory practice, and digital media, they interrogate the aesthetics of care, resistance, and interrelation.

This shift is not incidental. The rise of women artists has brought with it new themes, new audiences, and a more plural understanding of Basque history. It has also exposed the institutional gaps that persist—underrepresentation in museum collections, uneven funding, and gendered divisions in labor and visibility.

But these artists are not waiting for inclusion. They are reconfiguring the terms of engagement, from the ground up.

Cross-border collaboration with France and Latin America