Long before Indiana became a state or even a mapped territory, it was home to cultures whose artistic output was inseparable from the land itself. Chief among these were the Adena and Hopewell peoples, mound-building societies who flourished between roughly 1000 BC and 500 AD. Their artistic language, though largely anonymous and non-representational in the Western sense, was anything but primitive. It was complex, encoded, and often cosmic in orientation—woven into the very earth through vast geometric constructions.

Indiana’s most notable prehistoric artworks are not on canvas or stone, but in elevation and void. The mounds—circular, conical, or effigy-shaped—formed part of ceremonial landscapes aligned to solstices and cardinal directions. At sites like Angel Mounds near Evansville or the now-erased Yankeetown settlement along the Ohio River, earth itself became medium and message. These were artworks as much as they were spiritual instruments and cosmological diagrams. When archaeologists unearthed mica effigies, copper repoussé figures, and intricately carved pipes from burial sites, they found the buried fragments of a visual system deeply invested in transformation, death, and regeneration.

What sets the art of the Adena and Hopewell apart from later Indigenous work in Indiana is its abstraction. While later traditions leaned toward more figurative forms—especially under cultural pressures from European contact—these earlier cultures pursued a sacred geometry, a visual lexicon that mirrored the sky, the seasons, and mythic animals. These works were not merely decorative or didactic; they were technologies for navigating the invisible.

Symbols carved into the land

The symbolic power of Indiana’s prehistoric art often relied on scale and permanence. Unlike painted surfaces or textiles—nearly all of which have vanished due to the Midwestern climate—earthworks endure. Their survival is not just a matter of geology but a testament to the cultures that constructed them with long-range vision. The largest of these constructions, like those once present near New Castle or Muncie, were likely part of larger networks, tied to seasonal migration and intertribal gatherings that spanned hundreds of miles across what is now the American Midwest.

A key feature of these ceremonial landscapes was their integration with natural features. Rivers were often used as structural axes; ridgelines became processional paths. Some surviving sites reveal complex relationships between mound shape, artifact placement, and celestial movement—particularly the lunar standstill cycle, which takes 18.6 years to complete. In this sense, these were not isolated monuments but elements of a vast, living calendar.

Perhaps the most visually striking artifacts from this period are the so-called platform pipes. Carved from pipestone or catlinite, many feature stylized representations of birds, bears, or panthers—creatures associated with clan identity or cosmological realms. One such pipe, found near Vincennes, features a bird of prey with wings outstretched, the musculature rendered in confident, smooth contours. It is a small object, but one that compresses belief, status, and aesthetics into a hand-sized sculpture.

Cultural continuity and artistic rupture

While the Adena and Hopewell cultures declined by the 6th century AD, their visual traditions didn’t vanish overnight. Later Woodland and Mississippian peoples—including ancestors of the Miami, Potawatomi, and Shawnee—retained certain symbolic motifs and spatial habits. Angel Mounds, dating from around AD 1100 to 1450, shows strong Mississippian influence, with flat-topped mounds, central plazas, and fortified enclosures that point to both ceremonial and political functions.

The Mississippian aesthetic was less abstract than that of the Hopewell. It emphasized hierarchy, fertility, and warrior imagery. Pottery shards recovered from Angel Mounds depict human figures with elaborate headdresses and body paint, often engaged in ritual scenes. Shell gorgets—ornamental discs worn on the chest—show dancers, birds, and solar emblems incised with exquisite detail. These were objects of power and display, signaling social position and mythic alignment.

Then came rupture. With the arrival of Europeans in the 17th century, disease, displacement, and warfare fractured Indigenous life in the Midwest. Artistic traditions adapted, migrated, or disappeared altogether. Some art forms—like birchbark scrolls or wampum belts—survived in portable forms among refugee communities. Others vanished as mound sites were razed for farmland or urban development. In Indiana, the visual silence of these ancient cultures is not due to their absence, but to the layered erasures of settlement, agriculture, and modern industry.

Yet echoes remain. In the 20th and 21st centuries, Indigenous artists in Indiana have begun to reclaim and reinterpret ancestral forms. Artists like Katrina Mitten, a Miami beadworker, draw directly on patterns found in ancient motifs while introducing contemporary themes of survival and identity. Others, working in installation or performance, use the memory of mound sites to explore loss and renewal. The legacy of Adena and Hopewell art is thus not a relic but a resource—fragile, partial, and still unfolding.

The mounds may no longer dominate Indiana’s topography, but they remain embedded in the state’s artistic substratum—quiet foundations for the visual languages that followed.

Frontier Impressions: Early Euro-American Settlers and Folk Art

Cabin craft and communal creativity

The earliest European-American settlers who arrived in Indiana during the late 18th and early 19th centuries were not artists in any formal sense. They were laborers, farmers, soldiers, and families carving homesteads out of dense hardwood forests and swamplands. Yet from these raw beginnings emerged a distinctive vernacular aesthetic—one rooted in utility, repetition, and an acute sensitivity to material. Art, in this period, was inseparable from craft, and craft was inseparable from survival.

Life on the frontier demanded a kind of creativity that was both provisional and durable. Wooden chests, spinning wheels, and hand-hewn beams were all, in their way, aesthetic objects—shaped by necessity, but not without beauty. Settlers brought with them visual habits from Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Kentucky, where Germanic and Scots-Irish folk art traditions had long flourished. These traditions reemerged in Indiana in painted furniture, fraktur-inspired calligraphy, and stylized carvings on household tools. Every object bore the marks of both its maker and its place: axe strokes in the grain, sun-bleached wood, pigments mixed from earth and lye.

One of the most visible expressions of early settler art in Indiana was quilting. Often collaborative and deeply social, quilt-making served as a medium for storytelling, record-keeping, and the passing on of regional patterns. The star motifs, appliquéd birds, and hand-stitched initials found in Indiana quilts from the early 1800s echo both personal memory and communal design. While little of this work would have been classified as “art” at the time, it reveals a world of meaning hidden in domestic labor.

The communal nature of this early folk art was not merely a reflection of hardship; it was a declaration of interdependence. Quilting bees, barn raisings, and church frescoes weren’t just practical necessities—they were spaces of improvisational expression. In townships like Salem, Madison, and Corydon, visual culture emerged not in galleries but on walls, textiles, and headstones. Even the layout of early cemeteries—with their hand-carved gravestones and folk motifs—spoke a visual language of belief, sorrow, and hope in a hostile landscape.

Portraiture in the pioneer era

Despite the scarcity of professional artists in frontier Indiana, portraiture flourished in curious and telling ways. Often self-taught or itinerant, early painters like Jacob Cox and George Winter offered their services to wealthy settlers eager to affirm their permanence in a shifting land. These portraits are stiff by academic standards—awkward postures, simplified anatomy—but they reveal a powerful desire to be remembered.

Winter, in particular, left an archive of significant value through his visual documentation of Potawatomi life in the 1830s and 1840s. His paintings and drawings of individuals such as Chief Kee-wau-nay and Frances Slocum are among the few sympathetic depictions of Native Americans made by a Euro-American artist in Indiana prior to widespread removal. Though idealized in places, his work captures a world on the brink of disappearance with remarkable intimacy and restraint. It also introduces a tension that would persist through Indiana’s art history: the desire to record versus the impulse to idealize.

Meanwhile, less affluent settlers turned to silhouettes and daguerreotypes—technologies that democratized portraiture and brought visual self-representation to the broader public. By the 1850s, photography studios in Indianapolis and Terre Haute were offering affordable portraits to merchants, teachers, and veterans. These early images, often displayed prominently in parlors, marked a shift in how Indiana’s citizens viewed themselves: not merely as pioneers, but as individuals with lineage, pride, and visual permanence.

The frontier era also saw the emergence of political iconography, as banners, broadsides, and stump-speech stages integrated visual motifs into public life. Campaign paraphernalia for figures like William Henry Harrison and Abraham Lincoln employed folk design, bold typography, and patriotic symbolism that blurred the line between propaganda and pop art. In this way, the visual culture of the frontier was both deeply personal and brazenly public—an art of assertion in a contested landscape.

Quilts, gravestones, and vernacular beauty

The deeper one looks into the material culture of 19th-century Indiana, the more clearly its aesthetic patterns emerge—not as minor variations on East Coast forms, but as expressions of a specific, adaptive visual logic. This was an art of durable surfaces and layered meanings, embedded in the everyday. Gravestones in small cemeteries, for instance, were often carved with weeping willows, clasped hands, or flying doves—symbols that traveled across regions but gained local resonance. The softness of Indiana limestone made it an ideal material for such work, and many rural cemeteries still preserve these fragile, haunting testaments.

Similarly, barn painting became a modest but surprisingly enduring visual genre. In some counties, hex signs and patriotic murals adorned outbuildings, while mail-order stencils allowed even amateur hands to decorate rural landscapes with eagles, stars, and slogans. This intersection of commerce and folk design was one of the early signs of a shifting visual economy—an Indiana on the cusp of industrialization.

By the Civil War era, the visual imagination of the state had grown more confident, more settled. Town halls and churches now featured decorative woodwork, stained glass, and painted ceilings. Even the modest schoolhouse blackboard became a site of artistic expression, where ornate script and chalk borders revealed a teacher’s flair. Aesthetic instinct was no longer a luxury—it was integrated into the structure of daily life.

Three recurring features define this period of Indiana art:

- A commitment to utility that never excluded beauty.

- A deep interweaving of art with communal ritual and memory.

- A willingness to adapt older traditions into new environments and materials.

These were not artists by profession, but artists by necessity—and their work, humble and handmade, formed the substratum for every movement that would follow. What they lacked in academic training, they compensated for in tactile knowledge: of wood grain, dye saturation, stitch tension, stone weight. They worked with what they had and made it meaningful.

Indiana’s frontier artists left few manifestos, but their objects endure. They occupy attics and local museums, forgotten trunks and ancestral walls. Their quiet resilience speaks of a culture that understood art not as ornament, but as evidence: of survival, of memory, of place.

Drawing the State: Surveyors, Cartographers, and Visual Identity

Art as geography and claim

In the years following Indiana’s admission to the Union in 1816, the work of visualizing the land took on heightened political and cultural stakes. Before there could be paintings in parlors or sculptures in squares, there had to be lines—drawn, measured, mapped. Cartography in early Indiana was not just a bureaucratic exercise; it was an act of power, imagination, and proto-artistic vision. Surveyors, engineers, and mapmakers shaped how the territory would be understood, divided, and ultimately remembered.

The Public Land Survey System, implemented by the federal government, laid out Indiana in an orderly grid—a visual abstraction imposed on forests, swamps, rivers, and plains. Townships and ranges created rectilinear parcels that, once codified on paper, became saleable, taxable, and developable property. Yet these early maps were more than legal instruments. They were images of promise, anticipation, and assertion. To draw Indiana was to claim it, and to assign visual form to something that had previously existed only in oral traditions or as a sequence of landmarks.

The first state maps, often hand-colored and printed in limited runs, are among Indiana’s earliest examples of formal design. Figures like John Melish, whose 1818 map of the United States included newly minted Indiana, combined geographic accuracy with a flair for elegance—scrollwork titles, flourished compass roses, and stylized boundary lines. These maps were not neutral documents. They rendered rivers navigable, mountains scalable, and Indigenous presence invisible. By depicting land as legible and gridded, they created an image of order that belied the disorder of actual experience.

Some maps included vignettes or illustrations—tiny pastoral scenes, idealized settlements, or native fauna. In doing so, they acted as proto-propaganda, promoting Indiana as a place of agricultural bounty and civic possibility. These aesthetic decisions shaped not just how outsiders viewed Indiana, but how Hoosiers would come to view themselves: as inhabitants of a coherent, plottable space with visual and moral coordinates.

The Indiana map as iconography

As Indiana matured into a more structured society through the 19th century, the image of the map evolved into a form of popular iconography. County atlases, often published by firms like C.O. Titus or A.R. Rogerson, featured detailed engravings of towns, homesteads, and businesses. These atlases served dual functions—as practical tools and as civic trophies, documenting both geography and achievement.

It became fashionable for county seats to commission “bird’s-eye view” lithographs, panoramic illustrations that offered an imagined aerial perspective of towns like Lafayette, Fort Wayne, and Bloomington. These prints, often executed by artists working from elevated vantage points or sketches taken over days of walking, were marvels of invention. Buildings were rendered with architectural precision, and streets bustled with idealized activity. Like Renaissance cityscapes or Chinese scrolls, they compressed space and time into a single coherent image—part documentary, part fantasy.

These images also gave rise to a kind of Indiana-specific visual shorthand: courthouse domes, water towers, smokestacks, and rectangular town squares framed by uniform streets. From a distance, they looked almost interchangeable; up close, they revealed subtle variations of pride and identity. The repetition of certain motifs—fountains, churches, railroad depots—created a shared visual vocabulary that reinforced the state’s self-image as orderly, industrious, and forward-facing.

In schools and statehouses, maps became pedagogical tools, used to shape young minds and civic loyalty. Classroom wall maps printed by firms like Rand McNally turned Indiana’s counties into pastel shapes, each with a name, a crop, or an industry attached. These were not simply locational devices; they were visual narratives of settlement and progress. Through color, scale, and hierarchy, maps taught students what mattered—and what was best left unseen.

Even today, Indiana’s silhouette—angular, slightly hunched, with its northwest corner pulled toward Chicago—remains one of the most immediately recognizable state outlines in the country. It appears on license plates, beer labels, sports jerseys, and protest signs. The shape itself has become an emblem, its visual authority derived not just from borders but from two centuries of repetition and design.

Territorial symbols and state mythology

The urge to make the state visible extended beyond cartography. By the mid-19th century, Indiana began developing an iconographic system that fused geographic identity with myth-making. The state seal, for example—designed in 1816 and later standardized—features a woodsman felling a tree as a buffalo flees westward. This tableau, equal parts pastoral and manifest, encodes a specific vision of Indiana’s future: taming wilderness, displacing native fauna, advancing civilization.

This image became a motif throughout Indiana art and design, echoed in official documents, school insignias, and, later, WPA murals. It suggested that the state’s destiny was not merely agricultural or commercial, but moral—that progress was virtuous, and that clearing the land was an act of righteousness.

During the centennial celebrations of 1916, Indiana artists and civic boosters commissioned new visual representations of the state’s history. Posters, badges, and commemorative books blended historical imagery with art nouveau styling. Native Americans appeared as noble foils; pioneers as lantern-bearing heroes; railroads and wheat sheaves as symbols of enlightened abundance. These visual narratives often borrowed from national mythologies, but filtered them through an Indiana lens—one that emphasized moderation, industriousness, and homegrown pride.

Three visual myths emerged most strongly during this period:

- The myth of Indiana as a crossroads, where East meets West and North meets South.

- The myth of Indiana as moral heartland, sober and balanced in a turbulent nation.

- The myth of Indiana as canvas—a blank space made meaningful by order and cultivation.

Each of these myths was supported, and subtly advanced, by the visual arts of mapping, iconography, and civic design. Together, they created a framework in which art was not just decoration, but ideology.

Maps, seals, bird’s-eye lithographs, and pedagogical charts—all of these formed the state’s early visual culture. They taught Hoosiers how to see Indiana, where to place themselves within it, and why it mattered. And in doing so, they laid the groundwork for the state’s first proper art movement, which would take root not in surveyor’s offices or lithography studios, but in the dappled woods of Brown County.

The Rise of the Hoosier Group: Indiana’s First Art Movement

William Forsyth and the American Impressionists

By the late 19th century, Indiana had shifted from a frontier territory to a state defined by civic infrastructure, cultural institutions, and a burgeoning middle class. Railroads stitched the land into towns and cities. Industrial wealth flowed through places like Indianapolis and Fort Wayne. And amid this transformation, a small group of painters emerged who would claim the landscape itself as their subject—transforming Indiana from a backdrop into a primary artistic focus.

At the center of this movement stood William Forsyth, a wiry, driven man with a fiercely independent streak and a conviction that art should be both regional and refined. Trained at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich—where rigorous draftsmanship and muted palettes were standard—Forsyth returned to Indiana with technical mastery and a rebellious vision. Along with T.C. Steele, Otto Stark, Richard B. Gruelle, and J. Ottis Adams, he became one of the core members of what would later be dubbed the Hoosier Group.

These artists shared more than geography. They believed that Indiana’s natural landscape—the hazy light over cornfields, the soft edges of sycamore trees, the quiet lyricism of Midwestern dusk—deserved to be seen through a modern lens. They adopted techniques from French Impressionism but filtered them through the sensibilities of German training and Midwestern temperament. Their brushwork loosened. Their colors brightened. Their subjects, though local, gained a kind of universal resonance.

Forsyth, in particular, was less interested in placid pastoral scenes than in dynamism. His canvases often capture rivers in flood, trees in violent wind, or fields shimmering in heavy heat. There is always movement, a sense of immediacy, of brush touching canvas before the moment disappears. One of his signature works, The Canal at New Harmony, turns a rural waterway into a study in liquid geometry—brushstrokes that pulse with tension beneath apparent calm.

What set the Hoosier Group apart was their insistence that beauty did not belong exclusively to the coasts. Their vision of Indiana was neither rustic cliché nor urban idealism—it was rooted in observation, fidelity, and an affection that stopped short of sentimentality.

T.C. Steele and Brown County landscapes

The most celebrated member of the Hoosier Group was undoubtedly Theodore Clement Steele, whose trajectory from rural portrait painter to nationally recognized landscape artist paralleled Indiana’s own cultural maturation. Steele studied at the Royal Academy in Munich alongside Forsyth, but his artistic temperament leaned toward the meditative. He was not a provocateur, but a transformer—of land, of light, of paint.

In 1907, Steele moved to Brown County, a wooded, hilly region in south-central Indiana that would become synonymous with Indiana art for decades to come. There, he built a hilltop studio—now the T.C. Steele State Historic Site—and immersed himself in plein air painting. His canvases, often modest in scale, captured the shifting rhythms of seasons: sycamores in pale winter light, autumn hills burning in ochres and reds, spring wildflowers thick as mist.

Steele’s approach was quietly radical. At a time when American art was preoccupied with grand narratives, exotic travel, or symbolic abstraction, he chose instead to paint what was in front of him—and to do so with utter seriousness. His work gave Indiana a visual language of its own, one that neither borrowed from Europe nor imitated the Hudson River School.

Among Steele’s most compelling works are those in which nothing in particular happens: no dramatic foreground, no mythic figure, just a hillside, a tree, a sky. Yet within this apparent stillness, a viewer finds infinite variation—color harmonies, shifting light, the passage of weather. His October Afternoon (1903) exemplifies this subtlety, turning an ordinary slope into a symphonic meditation on amber and shadow.

Steele’s success—and his national acclaim—validated the notion that regionalism could coexist with sophistication. His presence in Brown County also attracted other artists, setting the stage for Indiana’s most enduring artistic enclave.

Breaking from the East Coast’s shadow

The Hoosier Group emerged at a time when American art was dominated by the cultural centers of Boston, Philadelphia, and New York. Museums, critics, and collectors often viewed Midwestern painters as provincial, their work as decorative at best, derivative at worst. The Hoosier Group rejected this hierarchy—not through confrontation, but through excellence.

In 1894, they staged a breakthrough exhibition at the Denison Hotel in Indianapolis. It was not a major art-world event by national standards, but it marked a seismic shift for Indiana. Crowds flocked to see canvases that depicted familiar scenes with unfamiliar brilliance. Forests they’d walked, streams they’d fished, barns they’d driven past on muddy roads—rendered suddenly in golden light, broken color, and confident abstraction.

This success allowed the artists to gain representation in major cities, and for a brief moment around 1900, Indiana painting stood at the forefront of American Impressionism. But even as their reputations grew, the Hoosier Group remained committed to their home state. They taught in local schools, painted civic murals, and mentored younger artists. Their studios became cultural hubs. Their values—of discipline, direct observation, and respect for place—shaped generations to come.

In this, their achievement was not merely artistic but institutional. They helped found the John Herron School of Art in Indianapolis. They shaped the policies of the Indiana State Fair’s art competitions. They encouraged the establishment of regional museums and supported a statewide infrastructure for art that still exists today.

Three qualities distinguish the Hoosier Group’s legacy:

- A stylistic synthesis of German realism, French light, and Midwestern humility.

- A steadfast belief in the aesthetic value of the local.

- A commitment to building institutions as well as images.

By the time the Hoosier Group began to fade in the 1920s, their influence had already transformed Indiana from a visual periphery to a self-aware cultural landscape. They did not merely paint Indiana—they made it visible, legible, and, crucially, beautiful in its own right.

Brown County as an Artist Colony

Arrival of Adolph Shulz and regional magnetism

The seeds sown by T.C. Steele’s solitary move to Brown County in 1907 soon germinated into something larger: a colony, a destination, an enduring artistic mythos. While Steele was the first prominent artist to live and work in the wooded hills around Nashville, Indiana, it was the arrival of Adolph Shulz in 1917 that crystallized Brown County as an intentional community of artists. Shulz, a German-American painter with training from both the Art Institute of Chicago and European ateliers, brought with him a missionary zeal—not for religion, but for art rooted in place.

Shulz found in Brown County a rare combination: dramatic terrain, cheap living, open air, and isolation without remoteness. Unlike other art colonies in New England or California, which often catered to social elites or tourists, Brown County offered rough cabins, dirt roads, and a lack of pretension. It attracted artists not seeking comfort, but freedom. What emerged was an artist colony less utopian than functional—more guild than commune.

The influx was gradual. Artists from Indianapolis, Cincinnati, and Chicago came for summer sketching trips and returned in autumn with canvases and stories. Some stayed. Others built studios. By the early 1920s, Brown County had its own exhibitions, critics, patrons, and even rivalries. It wasn’t just a collection of painters—it was a micro-society. The Brown County Art Gallery opened in 1926 and quickly became a cultural anchor, hosting juried shows and cataloguing the colony’s output. Visitors arrived by train or Model T to buy landscapes of hills they could see outside the window.

The artists came from varied backgrounds—classically trained, self-taught, bohemian, commercial—but were united by a shared devotion to the region’s natural beauty. And though styles varied, their subjects remained remarkably consistent: trees, hills, barns, creeks, livestock, and the changing sky. There was no manifesto, no house style, only the tacit agreement that Brown County was worth painting—and painting well.

Artistic communes and rustic modernity

The life of a Brown County artist was often austere. Many lived in converted barns or clapboard cottages without electricity or plumbing. They chopped wood, bartered produce, and hosted exhibitions in rooms warmed by potbellied stoves. Yet this simplicity was not merely economic—it was ideological. The rustic conditions fed into a broader aesthetic of authenticity. To paint the land, one had to live in it, and in some sense be shaped by it.

Among the most prominent residents besides Shulz and Steele were Carl Graf, Marie Goth, V.J. Cariani, and Will Vawter. Their approaches varied: Graf’s controlled tonalism, Goth’s soft pastels, Cariani’s vibrant brushwork, Vawter’s narrative vignettes. Yet they shared a common sensibility—a refusal to romanticize their surroundings, even as they honored them. These were not idealized Edens but working landscapes: fields overgrazed, barns sagging, skies brooding.

Brown County in this period also nurtured women artists in unusual numbers. The communal, non-hierarchical structure of the colony allowed women like Goth and Genevieve Goth Graff to work with a visibility rare elsewhere. The colony valued production and contribution over pedigree or gender. There were disagreements, certainly—over technique, over recognition, over artistic merit—but the overarching ethos remained democratic.

One of the more intriguing developments was how this rustic enclave adapted to the modern world. As cars replaced horses and tourists arrived in greater numbers, the artists of Brown County faced the risk of becoming a pastoral cliché. Some leaned into this—selling postcards, posing for magazines, cultivating a kind of folksy charm. Others resisted, retreating further into experimentation or abstraction. A few, like Carl Graf, even began incorporating modernist techniques into their landscapes, flattening perspective, emphasizing shape over realism.

This subtle tension—between tradition and innovation, between the ideal of the untouched landscape and the reality of change—defined the colony’s middle years. It made Brown County more than a scenic footnote in Indiana’s art history. It made it a crucible, where competing artistic philosophies coexisted in the same valley.

How a rural setting shaped a national style

Brown County’s significance lies not just in what it produced, but in what it prevented. At a time when American art was rapidly polarizing into New York modernism and regional kitsch, Brown County offered a third path: modern regionalism grounded in daily life, neither academic nor abstract, but disciplined and locally fluent.

The colony’s influence spread through exhibitions at the Chicago Art Institute, the Cincinnati Art Museum, and the Hoosier Salon in Indianapolis. Collectors and critics alike began to recognize Brown County not just as a charming backwater, but as a coherent and serious school of American painting. Its best artists didn’t just depict Indiana—they helped define how the Midwest could be seen: not as flyover land, but as a place of texture, color, and contemplative depth.

Three traits in particular defined the Brown County style at its height:

- A tactile sensitivity to seasonal shifts, rendered in palette and stroke.

- A focus on middle distance—neither panoramic nor intimate, but humane.

- A rhythm of light and shadow that echoed the rolling land itself.

This wasn’t landscape painting as background, but as character. The hills seemed to breathe. The skies held secrets. And even the barest tree became emblematic of endurance.

The colony’s decline in the 1940s and ’50s—brought on by war, death, and the dispersal of talent—did not erase its impact. Newer generations came to Brown County, drawn by legend and legacy. Abstract painters, photographers, sculptors—they all found traces of what the original colony had built: a belief that art could grow from the soil, if the hands and eyes were patient enough.

Today, Brown County remains a site of artistic pilgrimage. Its galleries still operate. Its woods still attract painters. And its legacy continues to inform not just Indiana’s art history, but the broader American story of what it means to make serious art outside the metropolis.

Art Education and Institutional Foundations

John Herron School of Art and its legacy

In 1902, just as the Brown County colony was beginning to coalesce, Indianapolis took a significant step toward institutionalizing the state’s artistic ambitions. That year marked the founding of the John Herron Art Institute, made possible by a bequest from local philanthropist John Herron and driven forward by civic leaders who recognized that for Indiana art to mature, it needed more than wild beauty and rugged painters—it needed a school.

From the beginning, the Herron School of Art was a hybrid institution: part academy, part museum, part cultural statement. Located in a repurposed building that once housed the city’s first high school, it was envisioned as both a training ground for serious artists and a public beacon for cultural enrichment. The school’s early curriculum emphasized classical draftsmanship, sculpture, and rigorous study from casts and live models—an approach that mirrored European academies and reflected the training of the Hoosier Group, many of whom had studied in Munich.

Yet Herron was never cloistered. From the outset, it invited interaction with the broader community. Its galleries were open to the public. Its students painted murals in local schools and churches. And its instructors, often respected artists themselves, blurred the line between professional practice and pedagogy. William Forsyth, one of its first and most influential teachers, brought with him not just technical mastery but a philosophy of artistic seriousness that shaped generations of students.

Under Forsyth and later directors, Herron cultivated a style that balanced observational realism with expressive color. It became known for producing skilled draftsmen, deft portraitists, and landscape painters who—while aware of national trends—remained rooted in Midwestern experience. But the school also nurtured more experimental voices. By the 1930s, courses in design, printmaking, and abstraction began to appear, reflecting the slow shift in American art toward modernism.

Herron’s importance lies not only in who it trained, but in how it shaped the infrastructure of Indiana’s visual culture. Graduates went on to teach in public schools, found galleries, design public buildings, and work in advertising studios. The school seeded artistic literacy across the state, ensuring that art was not just produced, but taught, critiqued, and sustained.

Civic museums and public ambition

If Herron was the state’s primary crucible for artistic training, its museums were the vessels through which art entered public life. The first major civic museum in Indiana was the Indianapolis Museum of Art, which evolved directly from the Herron Institute and opened as a standalone institution in 1970, following decades of growth and consolidation. Its collections, initially focused on European and American painting, expanded to include Asian art, design, textiles, and eventually contemporary work.

But long before its modern incarnation, the Herron Art Institute served as Indiana’s first public art museum. In the early 20th century, its exhibitions introduced Hoosiers to both Old Master reproductions and original works by regional artists. These shows were often ambitious—combining educational aims with genuine curatorial innovation. A 1913 exhibition, for example, juxtaposed recent Indiana landscapes with Japanese prints, suggesting affinities in composition and mood that went well beyond provincial taste.

Elsewhere in the state, smaller museums and galleries emerged with striking speed. The Fort Wayne Museum of Art, originally part of the public library system, began collecting and exhibiting in the 1920s. The Richmond Art Museum, founded in 1898 and housed in a public high school, became a model of civic integration, where students and townspeople alike could engage with serious visual culture. In towns like Lafayette, Evansville, and South Bend, art associations sprang up—some modest, some ambitious, but all committed to the belief that access to art was a public good.

These institutions were more than repositories. They were catalysts. They hosted lectures, competitions, children’s classes, and traveling exhibitions. They published catalogues and offered prizes. They brought in artists from Chicago, New York, and even Paris. In doing so, they made Indiana’s art world porous—open to influence, but firmly anchored in local identity.

And crucially, they created a middle-class audience for art. This was not patronage in the Gilded Age sense—though there were donors and collectors—but a more civic-minded form of support: garden clubs sponsoring exhibitions, teachers organizing field trips, industrialists endowing galleries. The art museum became part of the social contract: a place where aesthetics met aspiration.

Patronage, philanthropy, and the middle-class museum

The role of philanthropy in Indiana’s art history is impossible to overstate. From John Herron’s original gift to the later generosity of families like the Clowes, Lilly, and Ayres dynasties, private money fueled public culture. But unlike the heavily branded patronage of today’s art world, early 20th-century Indiana philanthropy often aimed at invisibility. The goal was not ego but legacy, and that legacy was civic.

The Clowes Collection, donated to the Indianapolis Museum of Art in the 1970s, is a prime example. Assembled quietly over decades, it includes significant works by Rembrandt, El Greco, and Tiepolo—an old-world trove embedded in a Midwestern setting. Such gifts elevated Indiana’s cultural standing while reinforcing a foundational idea: that serious art could belong here.

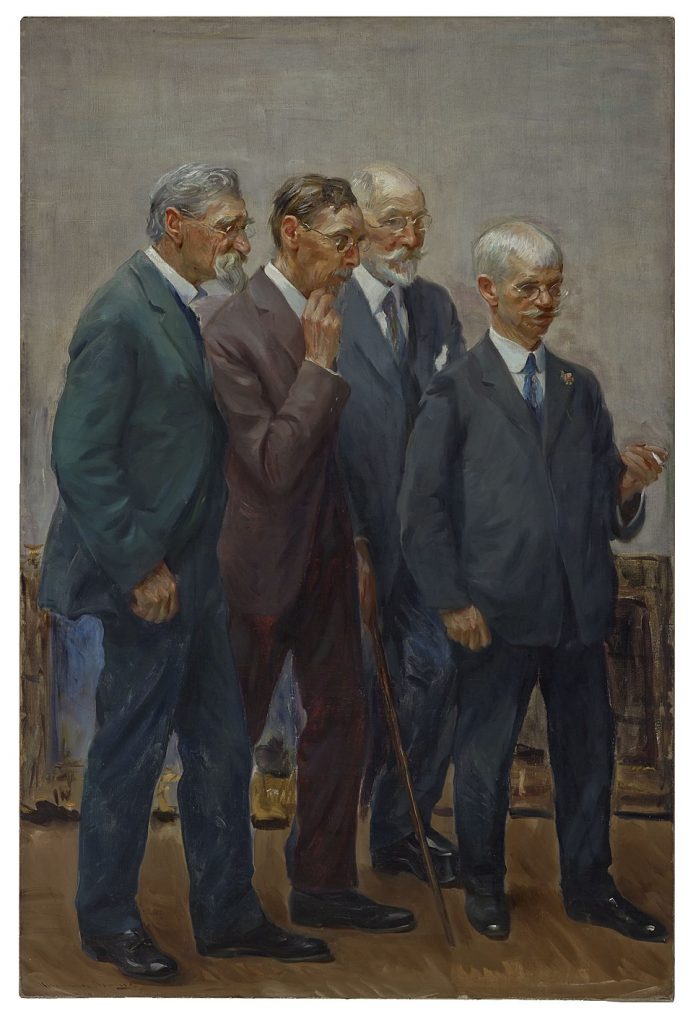

Philanthropy also extended to living artists. The Hoosier Salon, established in 1925 by a group of Chicago-based patrons with Indiana roots, offered an annual showcase for the state’s painters and sculptors. Juried and highly competitive, the Salon helped bridge the gap between local production and national recognition. For artists like Wayman Adams and Ada Walter Shulz, it provided both income and reputation.

Throughout the 20th century, Indiana also developed a robust culture of corporate patronage. Major employers—Eli Lilly, Cummins, Ball Corporation—commissioned murals, purchased paintings, and sponsored public sculpture. In towns shaped by industry, art became a means of softening modernity, of humanizing the machine age with beauty and craft.

Three principles defined this philanthropic ecosystem:

- A belief in permanence: that buildings, collections, and institutions should last.

- A bias toward accessibility: that art should be seen, not sequestered.

- A regional ethos: that national standards could be met without coastal approval.

Together, education, institutions, and patronage formed the backbone of Indiana’s artistic life. They did not merely support art—they helped define what art was, who it was for, and why it mattered. By mid-century, Indiana had produced not just individual artists, but an entire cultural architecture: schools to teach, museums to display, and communities to care.

Indiana and the American Scene

Regionalism and the Great Depression

By the 1930s, Indiana found itself squarely aligned with one of the most significant movements in American art: Regionalism. This was not mere coincidence. The values embedded in Regionalist art—fidelity to place, clarity of form, celebration of labor—had already been present in Indiana for decades through the Hoosier Group and Brown County painters. But the national crisis of the Great Depression gave these ideals new urgency. Regionalism offered a counterpoint to European modernism and New York abstraction: it was rooted in story, in soil, in the dignity of the visible world.

In this climate, Indiana artists were well-positioned to contribute meaningfully to the American Scene, a term broadly applied to representational art that depicted American life in its many forms. Their work featured rural towns, harvests, rail yards, and schoolhouses—images rendered with neither sentimentality nor satire. It was art that met its audience where they were, in terms they could understand.

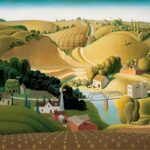

Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton are often seen as the figureheads of Regionalism, but Indiana produced its own significant voices. Among them was Francis Focer Brown, whose paintings of ordinary life in Muncie and the surrounding countryside were celebrated for their psychological depth and formal strength. Brown, like many of his contemporaries, viewed Regionalism not as a style but as a position: a refusal to detach art from everyday life.

Indiana’s educational institutions, especially the Herron School of Art and Ball State Teachers College, embraced the American Scene ethos. Students were trained not to chase innovation for its own sake but to observe, to interpret, and to find value in the overlooked. The prevailing aesthetic was clear-eyed and muscular. Paintings showed farmers stooped in fields, factory hands at shift’s end, women canning peaches or folding laundry—all of it with an awareness of both struggle and perseverance.

There was also a political undercurrent. While Regionalism is often dismissed as conservative or parochial, in Indiana it occasionally served as a vehicle for critique. Painters captured labor unrest, urban poverty, and the creeping effects of industrial sprawl. These themes were rarely foregrounded, but they lurked at the edges of canvases—an abandoned plow, a tilting smokestack, a face caught in fatigue.

Thomas Hart Benton’s circle and influence

Though Benton himself was born in Missouri and spent most of his career in New York and Kansas City, his ties to Indiana were deep and influential. His 1933 murals for the Indiana Hall at the Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago placed the state squarely in the national consciousness. These sweeping panels, later installed at Indiana University, offered a panoramic narrative of Indiana history: from Native American life to pioneer settlement, from steam power to radio towers.

The Benton murals were audacious. They did not flinch from conflict. Scenes of forced removal, slavery, and labor struggle appeared alongside wheat threshers and violin players. The style—Benton’s trademark muscular figures, sinuous lines, and rhythmic compression—gave the entire sweep of Indiana history a kinetic, mythic energy. Critics were divided. Some found the murals bold and unifying. Others accused them of distortion. But no one could ignore them. They made art central to public discourse.

Benton also left his mark through teaching. His influence extended to several Indiana artists, including future abstractionist Robert Indiana, who would take the lessons of bold form and graphic directness into a very different artistic realm. Benton’s commitment to making art that was legible to ordinary people resonated deeply in Indiana, where suspicion of elitism and abstraction had long defined local taste.

The broader impact of Benton’s work, and Regionalism in general, was to position Indiana not as a cultural periphery, but as a stage upon which national stories could be played. The state was no longer just a subject for landscape painters—it was a participant in a wider visual reckoning with American identity.

WPA murals and art for the people

Perhaps the most visible legacy of the American Scene in Indiana came through the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project, which provided employment for artists during the Great Depression while producing a vast trove of public art. Between 1935 and 1943, dozens of murals were commissioned for Indiana’s schools, post offices, and courthouses. These works, often executed in fresco or tempera, brought narrative painting into civic life with a scale and ambition previously unseen in the state.

One of the most celebrated examples is Lucerne Phelps’ mural in the Crawfordsville post office, which depicts scenes of local industry and agriculture in a style both heroic and intimate. The figures are stocky, the colors warm, the compositions balanced between realism and stylization. Elsewhere, murals in cities like Bloomington, Lafayette, and Richmond explored local history, often featuring vignettes of pioneer settlement, canal building, and the Civil War.

These murals were more than decoration. They were expressions of public memory, and sometimes, instruments of soft power. By placing art in daily spaces—where citizens mailed letters, paid taxes, or attended school—the WPA murals democratized both access and subject matter. They encouraged Hoosiers to see themselves as part of a shared story, rendered in pigment and form.

Yet these artworks also sparked occasional controversy. In a state as politically diverse as Indiana, disagreements about what stories should be told—and how—were inevitable. Some murals were criticized for including depictions of labor strikes or interracial cooperation. Others were attacked for modernist tendencies, their stylized figures deemed too abstract for public taste. But by and large, the WPA murals were embraced, and many remain in place today—a testament to the durable power of narrative imagery.

Three enduring effects of the WPA era in Indiana can be seen clearly:

- The elevation of everyday life to the level of public art.

- The integration of artists into civic infrastructure.

- The normalization of regional aesthetics as worthy of state and national platforms.

By the time the WPA folded in the early 1940s, Indiana had been transformed. Artists had been paid, trained, and celebrated. Towns and cities bore their images. And the public, long accustomed to seeing art as distant or elite, had come to expect it in their post offices, libraries, and town halls.

This was Indiana’s American Scene—not just a style, but a civic compact between artists and citizens. It gave the state’s visual culture a moment of coherence and momentum, a legacy that would echo through mid-century modernism and into the pop-inflected experiments of the decades to come.

African American Art in Indiana

The legacy of the Great Migration in visual form

By the early 20th century, Indiana’s demographic landscape was undergoing a profound transformation. The Great Migration—one of the largest internal movements of people in American history—brought thousands of African Americans from the rural South to industrial cities across the Midwest. Gary, Indianapolis, Evansville, and South Bend became destinations for families seeking economic opportunity and escape from Jim Crow oppression. Along with labor and music, these communities brought with them visual traditions that would reshape the state’s cultural fabric.

In Indiana, African American art evolved in close proximity to religious life, political activism, and education. Churches became central spaces not just for worship but for performance, poetry, and visual display. Quilts, banners, fans, and murals adorned sanctuaries, often drawing on Southern vernacular traditions. These were aesthetic objects as well as communal expressions—linked to memory, aspiration, and solidarity.

Art also became a tool for self-representation and cultural survival. As African Americans faced redlining, segregation, and racial violence—including the looming presence of the Ku Klux Klan in Indiana politics during the 1920s—painting, photography, and sculpture offered a means of documenting both joy and struggle. The domestic and the political converged in portraiture, street scenes, and allegorical work that gave shape to lives too often erased or distorted in mainstream depictions.

One of the most enduring legacies of this period is the visual vocabulary that emerged in Indianapolis, where the African American community along Indiana Avenue cultivated a vibrant and self-sustaining cultural economy. While the Avenue is most famous for its jazz heritage, its visual culture was equally rich, from barbershop murals to club signage, from church stained glass to studio portraiture.

The Great Migration made Indiana Black, not only demographically but artistically. It brought stories, colors, patterns, and faces that had never appeared in the state’s visual archive—and forced institutions to either adapt or remain provincial.

John Wesley Hardrick and overlooked innovators

Among the most important African American painters to emerge in Indiana during the early 20th century was John Wesley Hardrick, a largely self-taught artist from Indianapolis whose work reflects the power and precariousness of being Black in the Midwest. Hardrick studied at the John Herron Art Institute—one of the few African Americans admitted at the time—and exhibited in the prestigious Hoosier Salon, but his career was marked by both critical respect and systemic marginalization.

Hardrick’s work blends portraiture, landscape, and allegory. His palette is warm but disciplined, his compositions balanced, his faces luminous with internal life. One of his most striking paintings, The Family, shows three seated figures gazing directly at the viewer, their expressions calm but unresolved. There is no overt narrative, only presence—an insistence on visibility.

He was not alone. Artists such as William Edouard Scott, born in Indianapolis but trained at the Art Institute of Chicago and later in Paris, made national and international contributions. Scott painted everything from Haitian history to Harlem life, but never severed ties with his Indiana roots. His murals, like the one at Crispus Attucks High School, show African and African American figures in dignified, classical poses—an intentional rebuttal to racist caricature and historical erasure.

The story of Black artists in Indiana during the early and mid-20th century is one of both creativity and constraint. Opportunities were limited. Gallery representation was rare. Museum collections remained overwhelmingly white. Yet the work persisted: in church basements, community centers, schoolrooms, and home studios. It was sustained by networks of mutual aid, by teachers who encouraged talent, and by families who kept paintings safe even when institutions showed no interest.

Many of these artists have only recently been rediscovered by scholars and curators. Their marginalization was not due to lack of merit, but to the persistent racial hierarchies of the American art world. Their restoration to Indiana’s art history is not an act of charity—it is a return to accuracy.

Cultural memory and the politics of representation

In the latter half of the 20th century, African American artists in Indiana began to engage more explicitly with questions of history, identity, and political representation. The Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power era brought new energy—and urgency—to Black visual culture. Artists began not only to depict Black life but to intervene in the narratives surrounding it.

George M. Carter, active in Indianapolis in the 1960s and ’70s, used collage and mixed media to explore Black urban experience, often incorporating found objects, protest slogans, and archival photographs. His work was not easily classifiable—it was documentary and poetic, angry and tender. At a time when mainstream art institutions remained hesitant to engage with overtly political content, Carter’s work drew a line between personal experience and collective history.

Another major figure is LaShawnda Crowe Storm, whose 21st-century work continues this legacy of visual reckoning. Based in Indianapolis, she blends quilting, performance, and installation to address trauma, resilience, and ancestral memory. Her Madonna and Child series reimagines Black motherhood through a sacred lens, while The Lynch Quilt Project confronts America’s legacy of racial terror through the traditionally “safe” medium of textile art.

Contemporary Black art in Indiana often resists boundaries—between media, between disciplines, between private and public. It appears in murals on Indianapolis’s near Eastside, in pop-up exhibitions in Gary, in the galleries of mid-sized museums and the pages of independent zines. It draws from hip-hop, Afro-surrealism, religious iconography, and everyday aesthetics. It is not a movement, exactly, but a field: varied, fertile, and shaped by shared stakes.

Three defining traits have emerged from this evolving tradition:

- A commitment to memory as both source and subject.

- A refusal of aesthetic containment—Black art as multifaceted and mobile.

- A steady return to the body: Black presence rendered visible and undeniable.

What connects John Wesley Hardrick to LaShawnda Crowe Storm is not medium or style, but the insistence that Black life in Indiana is worth representing, in all its complexity. Their work challenges the state’s official histories and expands its artistic canon. In doing so, it makes Indiana not just more inclusive, but more honest.

The art of African Americans in Indiana is not peripheral to the state’s visual culture—it is foundational. It records what the official maps did not. It remembers what the textbooks forgot. It is, and always has been, part of the real scene.

Industrial Aesthetics: Factories, Labor, and Visual Modernism

Steel, speed, and geometry

Indiana entered the 20th century with a new kind of landscape: one shaped not by rivers or ridgelines, but by chimneys, conveyor belts, and furnaces. Cities like Gary, South Bend, and Fort Wayne evolved into industrial engines—drawing workers from across the country and the globe, transforming both the social and visual texture of the state. As labor and machinery redefined the physical environment, a new aesthetic emerged, forged in the noise and geometry of industry.

The visual language of this era was strikingly different from the pastoral serenity of Brown County or the restrained intimacy of the Hoosier Group. Industrial Indiana offered new materials, new subjects, and a new relationship between humans and their surroundings. Steel mills became cathedrals of scale. Railroad yards formed accidental grids. Assembly lines, with their synchronized movements and sharp lighting, became as formally compelling to modern artists as any traditional still life or figure study.

Artists began to treat factories not as background but as subject. Painters and printmakers—many influenced by modernist trends in Europe and American Precisionism—found abstraction in the real. A smokestack could mirror a column. An engine block became a study in texture. This was the world that Charles Sheeler and Charles Demuth explored nationally, but Indiana had its own interpreters: less famous, but no less observant.

Take, for instance, the work of industrial scene painter John Rogers Cox, born in Terre Haute. Though associated more with Regionalism than modernism, Cox’s stark, unpeopled landscapes—featuring empty highways, grain silos, and ominous skies—capture the psychological toll of mechanization with eerie clarity. His Gray and Gold (1942), with its endless fields of wheat flanked by a thunderous storm front, suggests not abundance but exposure—man dwarfed by the scale of labor and weather alike.

This period also saw a surge in photography as a means of documenting, and sometimes aestheticizing, labor. Photographers like Richard Welling and the industrial documentarians of the Farm Security Administration captured Indiana’s evolving infrastructure with precision and unease. The polished surfaces of turbines and the weary faces of steelworkers became twin emblems of a world remade by work.

Corporate art collections in the Midwest

With the rise of industry came wealth—and with wealth, the desire to commission, collect, and curate. By the mid-20th century, Indiana’s major corporations began assembling art collections that were not merely decorative, but strategic. They sought to express stability, modernity, and civic responsibility through visual culture. Office lobbies became galleries. Conference rooms featured original prints. Even factory floors, in some cases, displayed murals or photographic panels.

The pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly and Company, based in Indianapolis, was among the earliest and most ambitious in this regard. Its corporate collection included not just Indiana artists but national figures, reflecting a commitment to projecting global stature while nurturing local culture. The company also supported public art initiatives, museum exhibitions, and arts education—using art to soften its corporate image and reinforce its identity as a steward of culture.

Cummins Engine Company in Columbus, Indiana, offers an even more distinctive example. Under the leadership of CEO J. Irwin Miller, the company became an unlikely patron of both modern architecture and visual art. In the 1950s and ’60s, Miller commissioned works from artists and designers at the forefront of American modernism. Cummins buildings, designed by the likes of Eero Saarinen and Harry Weese, were furnished with original works—paintings, sculpture, even conceptual installations.

This fusion of commerce and culture did not always sit easily with the state’s more conservative artistic traditions. Critics questioned the sincerity of corporate patronage, and artists sometimes bristled at its constraints. Yet the influence of these collections was profound. They exposed employees and visitors to serious art. They created markets for regional artists. And they helped shape a visual identity for Indiana that was forward-looking, not nostalgic.

Three features defined Indiana’s mid-century corporate art ethos:

- A preference for abstraction as a signifier of progress.

- A focus on architecture and design integration.

- A belief in art’s potential to humanize the industrial experience.

In short, art became not just a response to industrialization—but a partner in it.

Architectural modernism and the urban grid

The visual transformation of Indiana in the industrial age was not limited to painting or photography—it was built into the very bones of its cities. Nowhere is this more evident than in Columbus, which by the 1970s had become an international case study in modernist urban planning. Through a partnership between the Cummins Foundation and world-renowned architects, the city created a coherent, visually adventurous environment where civic buildings—schools, fire stations, churches—were treated as design objects.

Landmarks such as the First Christian Church (1942) by Eliel Saarinen and the North Christian Church (1964) by Eero Saarinen brought Bauhaus principles to the Indiana heartland. Sleek lines, asymmetrical volumes, and minimal ornamentation stood in stark contrast to the neoclassical courthouses and Victorian storefronts found elsewhere in the state. These were not merely stylistic choices—they were declarations. Columbus insisted that Indiana could be a site of innovation, not imitation.

This ethos extended to public art. Sculptures by Henry Moore, Jean Tinguely, and Dale Chihuly appeared not in museums, but on lawns, in plazas, at intersections. The effect was not always uniformly embraced—many residents found the forms baffling or austere—but over time, a new visual literacy took root. Children grew up seeing abstract forms as part of their everyday environment. Workers passed by monumental installations on their way to lunch.

Other cities followed suit, if more cautiously. Fort Wayne commissioned modernist civic buildings in the 1960s. Indianapolis experimented with Brutalist courthouses and minimalist public sculpture. Gary’s once-thriving downtown, now largely in ruins, still holds traces of mid-century design ambition in its abandoned banks and theaters.

This architectural shift also affected how art was taught, displayed, and understood. Art departments at Purdue, Ball State, and Indiana University increasingly emphasized design, theory, and media experimentation. Students trained in the visual language of grids, angles, and industrial materials began to see their surroundings not as obstacles to creativity, but as raw material.

Indiana’s industrial aesthetics were never wholly celebratory. They reflected ambivalence as much as awe. Yet they transformed the state’s visual identity, embedding abstraction and geometry into the cultural DNA. They taught Hoosiers to see beauty in brick and chrome, rhythm in assembly, elegance in efficiency.

By mid-century, Indiana had become a site of industrial sublime—where the monumental and the mundane met in steel, glass, and shadow. It was a place where modernism took root not in salons, but in factories and foundations.

Pop, Concept, and the Experimental ‘60s and ‘70s

Robert Indiana and the rise of text-based art

When Robert Indiana’s LOVE image first appeared in 1965—its bold red letters stacked in a square, the tilted “O” creating instant tension and charm—it seemed to crystallize something the American art world had been groping toward: directness, accessibility, and the fusion of pop culture with high art. That this icon emerged from the brush of an Indiana-born artist who had changed his name to match his home state was more than irony—it was a statement of origin, geography as authorship.

Born Robert Clark in New Castle in 1928, the future Robert Indiana grew up in a series of rented homes, gas stations, and modest towns across the Midwest before finding his way to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, then to New York. But the choice to adopt “Indiana” as his professional name was not arbitrary. It was both a reclamation and a provocation—a way of asserting that even in the avant-garde capital of Manhattan, the flyover states could have a voice.

His early works, far more text-heavy than the LOVE series, included hard-edged paintings featuring highway signs, short slogans, and sharply delineated numbers. These were works that borrowed from roadside vernacular—billboards, gas pumps, diner menus—but presented them with formal rigor and cultural ambivalence. In pieces like The American Dream or Eat/Die, Indiana conjured an iconography of consumerism, patriotism, and existential malaise.

Though often grouped with Pop Art, Indiana remained slightly outside the movement’s core. He lacked Warhol’s deadpan irony or Lichtenstein’s comic flair. Instead, his work carried a Midwestern gravity—a sense that language could be both visual form and moral content. His obsession with symmetry, repetition, and signage connected him not just to Pop, but to American folk art and Shaker design.

Indiana’s greatest achievement may not be any one work, but the way he transformed his background—rural, itinerant, and often alienated—into a visual language that was unmistakably his own. He took the signs of America’s highways and turned them into symbols of its emotional infrastructure: love, fear, ambition, death.

Psychedelic posters and counterculture graphics

While Indiana was crafting polished meditations on text and meaning in New York, a very different strain of visual experimentation was erupting across Indiana’s college campuses. By the mid-1960s, fueled by the Vietnam War, civil rights protests, and an influx of federal funding for the arts, universities became laboratories for aesthetic rebellion. And nowhere was this more vividly expressed than in the explosion of graphic design tied to music, protest, and alternative media.

Bloomington, home to Indiana University, emerged as an unlikely hub of psychedelic poster art. Student-run printing presses churned out announcements for underground concerts, film screenings, and teach-ins, often using hand-lettered fonts, clashing colors, and kaleidoscopic imagery. Influenced by West Coast artists like Victor Moscoso and Wes Wilson, Indiana’s graphic artists localized the counterculture—combining Day-Glo aesthetics with Hoosier references: cornfields morphing into mandalas, Abe Lincoln in sunglasses, peace signs embedded in barns.

The line between design and activism blurred. Posters became ephemeral artworks, but also tools of agitation. Some documented draft resistance and sit-ins; others advertised free speech rallies or women’s health workshops. Their visual density, surreal humor, and DIY ethos challenged not only political authority but also aesthetic hierarchy.

At Purdue University and Ball State, similar currents emerged—though often with a more technical or conceptual edge. Engineering and design students created hybrid media works, early computer-generated graphics, and modular sculpture kits. The art department bulletin boards became accidental exhibitions: flyers, manifestos, collaged announcements layered thick with tape and texture. This was not museum art. It was fast, public, and alive.

Importantly, many of these works did not survive. Printed on cheap paper, taped to dorm doors or trees, thrown away after a weekend. But their influence persisted, subtly altering the visual codes of Indiana’s youth and linking local experimentation to a larger national ferment.

University studios as avant-garde laboratories

As the cultural upheavals of the 1960s gave way to the pluralisms of the 1970s, Indiana’s universities became more than campuses—they became crucibles of aesthetic innovation. Departments of art, design, architecture, and media studies began hiring faculty from across the country, including veterans of the New York School, the Bauhaus diaspora, and early conceptual circles. These instructors brought not only new methods, but a new sense of what art could be: ephemeral, collaborative, anti-commercial, idea-driven.

Indiana University’s Henry Radford Hope School of Fine Arts in Bloomington became a focal point. There, under the direction of forward-thinking faculty, students experimented with video, performance, and installation art long before such media were institutionally recognized. One influential figure was Barry Gealt, a painter whose abstract landscapes bridged gestural expressionism with environmental awareness. Another was Robert Laurent, a sculptor whose works combined figuration with modernist compression—introducing students to both classical form and its deliberate undoing.

At Purdue, the intersection of art and technology became a generative force. Courses in computer art and systems theory laid the groundwork for digital aesthetics. Student projects incorporated circuitry, sound feedback, and interactive sensors. Some of these early pieces feel rudimentary today—lights blinking in programmed sequences, punch cards transformed into kinetic mobiles—but they represented a break from object-based art toward process and participation.

Ball State, meanwhile, developed a reputation for architectural experimentation. Its College of Architecture and Planning, influenced by both Bauhaus pedagogy and American pragmatism, treated the built environment as both problem and possibility. Students designed geodesic domes, modular housing, and environmental interventions that blurred the line between sculpture and shelter.

Three core practices defined Indiana’s experimental art scene in these decades:

- An embrace of impermanence: art as event, gesture, or trace.

- A rejection of traditional media hierarchies: video equal to oil paint.

- A commitment to teaching as practice: studio as dialogue, critique as creation.

While New York critics still framed the avant-garde as a coastal affair, Indiana artists were pushing boundaries in print shops, cornfields, and fluorescent-lit classrooms. Their work was less visible, perhaps, but no less daring. It took risks with form, space, and expectation.

And it left traces. Many of these artists went on to influence national discourses: as educators, curators, and innovators. Their students carried these ideas into new mediums—public art, digital installation, environmental design. The state, once imagined as a cultural backwater, had become an incubator.

By the end of the 1970s, Indiana’s art world could no longer be dismissed as regional in the pejorative sense. It was regional in the richest sense: rooted, specific, experimental, and open to the world.

The Indiana Diaspora: Artists Who Left but Looked Back

Jim Davis and the graphic turn

One of the most commercially successful and globally recognized artists to emerge from Indiana did not work in oil or marble, but in pen, ink, and punchline. Jim Davis, the creator of Garfield, launched his career from Muncie in 1978, producing a daily comic strip that would go on to appear in more than 2,500 newspapers worldwide. While dismissed by some critics as trivial, Garfield represents a pivotal shift in Indiana’s visual culture: from the pastoral and painterly to the graphic and reproducible.

Davis, a graduate of Ball State University, worked in advertising before turning to comics full-time. His genius was not in draftsmanship—Garfield’s rounded forms and spare settings were intentionally simple—but in his grasp of mass media. He designed his strip for maximum syndication and scalability. The fat orange cat, with his deadpan expressions and middle-American ennui, was as much a brand as a character. Lunchboxes, plush toys, cartoons, greeting cards—the franchise grew so vast it threatened to eclipse its creator.

Yet behind the merchandising empire was a keen visual strategist. Davis built Garfield’s world with minimalist precision: three panels, a single joke, a signature color palette. His studio, Paws, Inc., operated from rural Indiana, signaling that creative capital no longer required proximity to New York or Los Angeles. In this sense, Davis embodied a new kind of Indiana artist—one who looked outward while remaining physically rooted.

What makes Davis relevant to art history, rather than just pop culture, is his role in normalizing the graphic vernacular: simple lines, flat color, and mass circulation as legitimate aesthetic tools. His work paralleled broader movements in illustration, advertising, and early digital design. And while Garfield never aspired to profundity, it proved that visual language born in Indiana could saturate the global imagination.

Abstract expressionists with Hoosier roots

While Indiana nurtured many who stayed, it also produced artists who left—seeking the critical mass, funding, or friction they couldn’t find at home. Among these were painters and sculptors who emerged from Indiana schools only to align with the dominant movements of their time, particularly Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, and Post-Minimalism. Yet even as they moved into global circuits, many retained a tonal imprint of their Midwestern origins: restraint, order, and an affinity for structure over spectacle.

One such figure is Sam Gilliam, who studied at Indiana University in the 1960s before becoming a central voice in the Washington Color School. Though born in Mississippi, Gilliam’s years in Bloomington were formative. He absorbed not only color theory and modernist composition, but also the spare, deliberative sensibility that would come to define his draped canvas works. These were paintings that left the stretcher behind, suspended from ceilings and walls like textiles—part sculpture, part gesture, all surface.

Similarly, the minimalist sculptor Ronald Bladen, who spent part of his early training in Indiana, produced monolithic works—black-painted structures with sharp edges and industrial gravitas—that reflect the industrial modernism of Indiana’s built environment. While Bladen’s career unfolded in New York and Europe, his spatial vocabulary—weight, shadow, clarity—echoed the grain silos and steel mills of his youth.

These artists rarely invoked Indiana explicitly in interviews or titles. Yet their abstraction bears traces of the state’s visual DNA: its horizontal sprawl, its architectural sobriety, its emphasis on form over flourish. Even when far from home, they carried Indiana’s visual logic with them.

This quiet influence surfaces again and again in the diaspora: in the color fields of Alma Thomas (who briefly taught in Indiana), the structured experiments of Vija Celmins (born in Latvia, raised in Indianapolis), and the photography of Garry Winogrand, whose early projects included visits to Midwestern towns. The state, even unmentioned, lingers in their lines and frames.

Nostalgia, irony, and reimagination of place

By the late 20th century, a new generation of Indiana-born artists began to revisit the state not with loyalty or dismissal, but with irony, nostalgia, or both. They saw their childhood landscapes not as sites of purity, but as ambiguous backdrops—haunted by memory, shaped by cultural tension, and ripe for reinvention.

One such artist is Tony Tasset, born in Cincinnati but raised in Indiana and educated at the Art Academy of Cincinnati and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Tasset’s work is conceptual, often playful, and deeply engaged with Americana. His Eye (2010), a three-story fiberglass eyeball installed in downtown Dallas, exemplifies his brand of surreal monumentality—simultaneously comic and unsettling. Though not explicitly about Indiana, Tasset’s sensibility—the deadpan tone, the obsession with surface, the evocation of childhood unease—feels forged in the flat expanses and psychological ambivalence of the Midwest.

Similarly, the work of contemporary artist Kay Rosen, long based in Gary and then New Orleans, plays with language as visual form. Her wall-based text pieces twist familiar phrases into puzzles, puns, and political provocations. Her aesthetic is clean and typographic—rooted in the tradition of Robert Indiana, but drier, more cerebral. In one piece, BLOWUP, the letters stretch across a white wall, both shouting and deflating. It’s conceptualism with a Hoosier accent: blunt, unpretentious, quietly subversive.

Many Indiana-born artists now engage with the state as a conceptual site rather than a literal one. They use it as a stand-in for middle America, for cultural contradiction, for the intersection of nostalgia and estrangement. Some, like photographer Ryan McGinley or filmmaker David Anspaugh (Hoosiers), frame Indiana as a space of longing and heroic myth. Others, like essayist and visual artist Joe Bonomo, depict it as a ghost town of memory—both claustrophobic and comforting.

Three thematic threads emerge in this diaspora art:

- The use of Indiana as metaphor—less geography than emotional shorthand.

- A visual grammar shaped by childhood exposure to signage, grids, and public architecture.

- An oscillation between affection and critique—never wholly rejecting, never wholly embracing.

These artists prove that departure does not sever influence. The Indiana they carry with them is portable: a palette, a rhythm, a mood. Whether through cartoon cats, monumental eyes, or drifting canvas, they reinterpret the state for audiences who may never set foot there.

And in doing so, they expand Indiana’s artistic footprint—not as a bounded place, but as a permeable idea.