Edma Morisot may not be a household name in the history of French painting, but her influence is woven deeply into the fabric of one of the greatest art movements of the 19th century. As the older sister of the renowned Impressionist painter Berthe Morisot, Edma was not merely a family member; she was an early collaborator, confidante, and above all, a profound muse. Her presence appears again and again in the early works of Berthe, not just in form but in spirit.

Unlike many muses of art history who were romanticized or idealized, Edma was a woman of grace and modesty who represented the quieter virtues of womanhood—devotion to family, duty, and inner strength. Her image, captured in a handful of thoughtful and elegant portraits, helped Berthe develop her unique focus on female interiority and the sanctity of domestic life. Though Edma left the art world when she married, the emotional and artistic impact she had on her sister never faded.

In the context of a society that valued modesty, fidelity, and feminine virtue, Edma’s role exemplifies how influence does not always stem from prominence or fame. Sometimes, it’s the steady presence and unwavering character of a loved one that shapes greatness. Edma was that silent force behind the curtain—a muse of conviction, not ambition.

Her story provides a valuable lens through which to appreciate not only the development of one of France’s greatest female painters, but also the powerful and often unsung role traditional women played in shaping the culture and spirit of their time.

Why Edma Morisot Still Matters

Even in the contemporary rediscovery of women artists and figures in history, Edma Morisot remains underappreciated. Her significance lies not in artistic output or public acclaim, but in her profound contribution to the private, emotional, and visual development of one of the foremost female painters of the 1800s. She served as a spiritual and artistic anchor for her sister, offering more than just a face for a canvas.

As muse, Edma inspired themes of tranquility, femininity, and reflection—foundational elements in Berthe Morisot’s early compositions. These themes, refined over time, would come to define much of the Impressionist style Berthe helped establish. Without Edma, these beginnings may have looked very different.

Redefining the Role of the Muse

Traditionally, muses are seen as romantic partners, mythic ideals, or figures of dramatic intrigue. Edma redefines the role—bringing it closer to home and rooting it in familial loyalty. She didn’t seek the limelight or demand attention, yet she deeply influenced one of the movement’s finest talents.

This redefinition is essential to understanding the moral and cultural texture of the 19th century. It shows that greatness is often nurtured in the quiet corners of family life—not the noisy salons of Paris.

The Morisot Sisters: A Creative Bond Forged in Family

Edma Morisot was born on December 17, 1839, in Bourges, France, into a well-off and respectable family with strong values rooted in propriety, culture, and discipline. Her sister Berthe followed two years later, born on January 14, 1841. Their father, Edmé Tiburce Morisot, was a high-ranking government official who ensured his daughters received a quality education—a rarity at the time for women, especially in the arts. Their mother, Marie-Joséphine, encouraged refinement and moral sensibility, setting the foundation for a home centered on decorum, family loyalty, and Christian virtue.

Unlike the public academies that restricted female participation, the Morisot girls were privately tutored at home. They received artistic instruction from Joseph-Benoît Guichard, a former student of Ingres, who instilled in them the fundamentals of form and classicism. Later, under the mentorship of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, one of the great landscape painters of the time, they learned plein air painting and gained exposure to the naturalistic traditions that would influence the Impressionists. The sisters painted together constantly, forming not just a personal but also a professional bond.

From the very start, Edma and Berthe were artistic equals. Both exhibited great promise, and their works were shown in the Salon de Paris, the prestigious official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Their works were accepted into the Salon as early as 1864, and they received favorable mentions—especially impressive for female painters at that time. There was no rivalry between the two; rather, they encouraged one another, working side by side, painting the same scenes, and engaging in constructive critique.

This sisterhood was more than familial—it was spiritual and intellectual. While Berthe eventually became a public figure in the art world, Edma was content with a quieter life. Yet during those formative years, her partnership with Berthe forged a level of trust and familiarity that allowed for deep artistic exploration. Their bond was the backbone of their early careers.

Artistic Upbringing in a Conservative Household

The Morisots’ household was steeped in the ideals of honor, duty, and intellectual refinement. Rather than being swept into the radical social changes of the era, the family maintained a commitment to traditional values. Their art training was not viewed as rebellion, but as an extension of their cultured upbringing.

The girls’ education emphasized responsibility and discipline. There was a sense of mission behind their artistic efforts, not the pursuit of fame. These values enabled both sisters to develop serious technical skills and to focus on substance rather than show.

A Sisterhood Rooted in Discipline and Devotion

The Morisot sisters didn’t just paint together—they lived in constant conversation about art, literature, and the world around them. This closeness helped shape their perspectives and priorities, setting them apart from their contemporaries. Edma’s steady temperament and moral clarity often grounded Berthe, who was more adventurous artistically.

The two supported one another through critiques, experiments, and even professional submissions to the Salon. This dynamic was not one of competition, but of mutual fortification—two women striving for excellence in harmony.

Edma as Model: Stillness and Serenity in Berthe’s Early Works

Throughout the 1860s, Edma served as Berthe’s most trusted and frequent model. This was more than convenience—it was a matter of trust. In a world where female models were often associated with scandal or impropriety, especially for women artists, Edma’s presence offered a safe and dignified alternative. Her willingness to sit, often for hours, allowed Berthe to refine her sense of composition, emotion, and gesture.

One of the most notable works in which Edma appears is The Artist’s Sister Edma (c. 1869), currently held at the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris. In this portrait, Edma sits calmly near a window, clothed modestly in black. Her hands are folded in her lap, and her gaze is turned away from the viewer. The entire scene is one of interior peace and dignity. This is not a theatrical composition; it’s a quiet moment of real life captured with reverence.

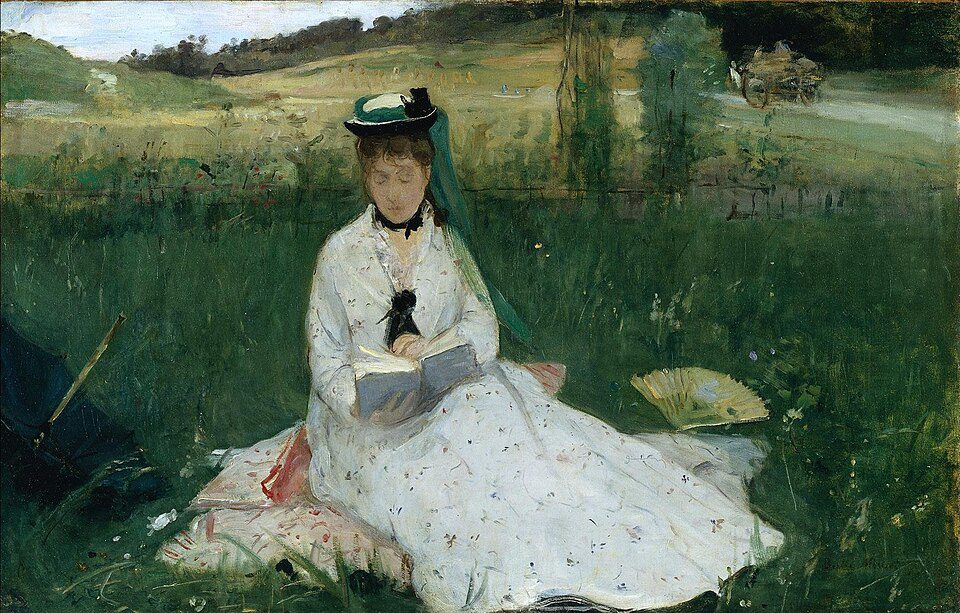

Berthe painted several other portraits and sketches of Edma, some of which are now in private collections or lost. These include Edma Reading, a delicate portrayal of concentration and grace, and various studies from their time under Corot. In all of them, Edma is portrayed not as an object of desire, but as a figure of contemplation and moral clarity.

This consistent depiction reflects a deeper message. Edma’s presence in these works signified the value of domestic life, stillness, and restraint—virtues largely cast aside in later, more radical artistic movements. But in the Morisot household, they were central.

Capturing the Essence of Femininity

Berthe’s portraits of Edma were never flashy. They didn’t seek to shock or provoke. Instead, they captured the essence of real womanhood—serene, composed, intelligent. In doing so, Berthe was challenging the dominant norms of how women were typically portrayed in art.

Through Edma, Berthe learned how to paint emotion without excess. The quiet power in her early portraits owes much to Edma’s composure and reliability as a model.

Realism and Restraint in Edma’s Depiction

The restraint shown in Edma’s portrayals is not a lack of emotion but a mark of strength. Her calmness, her modesty, and her poise were virtues in themselves. In an era that increasingly celebrated rebellion and self-indulgence, the Morisot sisters offered a counterpoint—elevating quiet dignity above theatrical display.

These artistic choices helped Berthe define her voice, and Edma’s role as a model was instrumental in that evolution.

Notable Works Featuring Edma Morisot

- The Artist’s Sister Edma (c. 1869) — Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

- Edma Reading (date and location uncertain)

- Portrait of Edma Morisot in Profile (1865) — Private Collection

- Sketches from the Corot Period (early 1860s)

- Various figure studies now in archives or catalogues raisonnés

A Turning Point: Edma’s Marriage and Departure from Art

In 1869, a profound change occurred in Edma Morisot’s life—one that would also reshape Berthe’s world. That year, Edma married Adolphe Pontillon, a French naval officer. With this decision, Edma stepped away from the Parisian art scene and the shared studio she had occupied with her sister. The marriage marked a traditional turning point: Edma embraced the role of wife and future mother, choosing family and domestic life over a continued artistic career.

This decision aligned with the values she was raised with—those of duty, order, and feminine modesty. In choosing marriage, Edma conformed to the expectations of her class and time, not out of submission, but from a personal sense of fulfillment and purpose. While Berthe went on to become one of the most celebrated Impressionist painters, Edma took a quieter path that was no less honorable. Her decision reflected the common reality for many talented women of the 19th century who had to choose between professional ambition and familial duty.

For Berthe, the change was heartbreaking. The sisters had been constant companions for more than a decade—painting, studying, and discussing life. Edma’s departure left a void, both emotionally and artistically. Berthe wrote to her sister often, expressing how much she missed her presence in the studio. In one letter, Berthe confessed that she no longer felt the same confidence in her work without Edma’s gaze and encouragement.

Though Edma continued to correspond and offer moral support, her withdrawal from artistic life was permanent. She moved to Lorient, Brittany, with her husband and would have a daughter in the early 1870s. Her painting days were over, but her influence lived on—especially in the tone and themes of Berthe’s later work.

Duty Over Ambition—Choosing a Traditional Life

Edma’s decision to prioritize marriage over her art was not a failure, but a commitment to the natural order she believed in. She followed her conscience and social duties, embracing a life grounded in stability and service to others. In a modern context, this choice may seem limiting, but in her time, it was deeply respected.

This wasn’t resignation—it was conviction. Edma didn’t fade from painting out of lack of talent or interest; she simply placed greater value on the sacred vocation of family life. Her sacrifice was not one of oppression, but of intentional dedication.

The Emotional Rift Felt in Berthe’s Letters

After Edma’s marriage, Berthe’s letters became noticeably more introspective. She often spoke of feeling alone, uncertain, and even directionless without Edma’s companionship. These letters offer invaluable insight into the emotional support system Edma had provided.

Berthe’s artistic confidence had long been tethered to their shared endeavors. With Edma gone, she had to find a new source of inner strength—one that would eventually push her into the heart of the Impressionist movement. But the pain of separation is evident in every carefully penned letter.

The Invisible Influence: Edma’s Absence in Berthe’s Later Work

Following Edma’s departure, Berthe Morisot’s paintings began to shift. While she remained committed to the Impressionist style she helped pioneer, there was a subtle transformation in her choice of subjects and emotional tone. Her later portraits of women—often mothers, daughters, and solitary female figures—carry an unmistakable sense of quiet longing and introspection.

Art historians have noted that the emotional depth found in these works may be traced back to Edma’s absence. No longer surrounded by the collaborative energy of her sister, Berthe began to explore the internal world of her subjects with greater intensity. Where her earlier works celebrated sisterhood and shared joy, her later pieces often examined solitude, memory, and reflective stillness.

This influence, though intangible, was profound. Edma’s physical absence became a kind of ghostly presence in Berthe’s art—her memory saturating each brushstroke with unspoken feeling. Paintings like The Mother and Sister of the Artist (1870) show Berthe’s mother and Edma seated together in a domestic setting, their expressions gentle but withdrawn. It’s a farewell captured in oil—still, somber, and deeply moving.

In many ways, Edma became a muse in absentia. Her legacy shaped not only what Berthe painted, but how she saw the world.

The Muse Who Wasn’t There

Few muses have had as much influence by their absence as Edma Morisot. The silence she left behind became a new kind of voice in Berthe’s paintings. Her departure forced Berthe to mine new emotional depths and develop a more nuanced understanding of womanhood, motherhood, and solitude.

This transition added greater maturity and psychological complexity to Berthe’s work, suggesting that Edma’s role as muse didn’t end—it simply evolved.

Loss, Loneliness, and Artistic Depth

Art born from loss often carries a unique resonance. In Berthe’s case, the departure of her closest companion brought forth a tenderness and depth that remain unmatched in her oeuvre. Her brush seemed to slow, to listen more, to feel more deeply.

This wasn’t mere melancholy; it was refined sensitivity, a way of capturing the emotional texture of everyday life. And that depth, in large part, came from the absence of the sister who had once been by her side.

Contrasts Between Sisters: Talent vs. Vocation

As the years passed, the contrast between Edma and Berthe Morisot’s lives became more pronounced. Edma, after marrying Adolphe Pontillon in 1869, fully embraced her role as wife and mother, living primarily in the naval port town of Lorient. Her sister Berthe, meanwhile, remained in Paris, dedicating herself to painting and eventually marrying Eugène Manet, the brother of Édouard Manet, in 1874. The choices each sister made reflected not a division of character, but a divergence of vocation.

Edma’s life path was rooted in tradition—upholding the values of family, faith, and domestic duty. She relinquished her public ambitions to support her husband’s naval career and raise their daughter, Jeanne Pontillon. There are no records of Edma ever returning to professional painting, suggesting that she found full contentment in her domestic life. This was not unusual for women of her time, and it should be seen not as surrender but as a reflection of personal virtue and clarity of purpose.

Berthe, by contrast, entered the public eye, exhibited with the Impressionists, and faced the trials of being a female artist in a largely male-dominated field. While she achieved success, it came at the cost of solitude and societal scrutiny. Her marriage to Eugène Manet was supportive, yet she continued to carry the burdens of her career and artistic ambitions alone. Her daughter, Julie Manet, would later become a central figure in preserving the legacy of both her mother and her aunt.

Though their lives diverged, neither sister outshone the other in terms of character. Edma chose stability; Berthe chose the uncertain path of the artist. Both women demonstrated strength, each in her own way. These contrasting lives speak to the limited, yet meaningful, options available to women in 19th-century France.

Edma’s Quiet Life and the Virtue of Duty

Edma’s decision to walk away from painting was not an abandonment of talent, but a conscious embrace of vocation. In a culture that prized duty, self-sacrifice, and domestic stability, her role as a devoted wife and mother reflected societal ideals of feminine virtue. She understood that influence did not require public acclaim.

Her legacy is a reminder that quiet lives can leave lasting impacts, especially when lived with honor and conviction. Edma supported not only her husband and daughter but continued to be a moral pillar for her sister through correspondence and emotional support.

Berthe’s Public Success and Private Struggle

Berthe’s professional success often came with personal cost. While she received acclaim for her unique style and dedication to modern life, she frequently expressed a sense of isolation. After Edma’s marriage, she no longer had the artistic companionship that had once sustained her. Even after her own marriage to Eugène Manet, she remained emotionally tethered to her earlier bond with Edma.

It is telling that Berthe continued to return to subjects of sisterhood, motherhood, and quiet reflection in her later works. These were not merely artistic choices—they were emotional echoes of the bond she had once shared with Edma.

Edma in Letters and Memory: A Life Remembered

While Edma Morisot may have faded from the art world after 1869, she remained very much present in Berthe’s thoughts, writings, and memory. The correspondence between the sisters is a rich archive of emotional honesty, artistic introspection, and sisterly love. These letters show that while Edma left the studio, she never stopped influencing her sister’s creative world.

In these letters, Berthe often lamented the distance between them and expressed how much she missed Edma’s companionship. The emotional tone in their exchanges remained deep and affectionate throughout their lives. Even after marrying and becoming a mother, Edma continued to offer thoughtful feedback on Berthe’s paintings, encouraging her sister with sincerity and pride.

Berthe’s paintings also bear witness to Edma’s enduring presence. Even when Edma was no longer a model, her likeness and the essence of her composure can be seen in other female subjects. It’s as though Berthe carried Edma’s image in her mind, painting variations of her sister’s quiet strength into her works.

When Berthe died in 1895, Edma outlived her by 26 years. She passed away on May 2, 1921, at the age of 81. Though she did not enjoy public recognition, her role as muse, sister, and moral guide was remembered by those closest to her—especially her niece, Julie Manet, who cherished both her mother and her aunt as guiding figures in her own upbringing.

Tracing Edma’s Voice in the Correspondence

The surviving letters between Edma and Berthe reveal a sisterhood grounded in mutual respect and admiration. Edma frequently asked about Berthe’s progress, offered encouragement, and shared her thoughts on art and family. Their correspondence offers rare insight into the emotional framework behind some of Berthe’s most beloved works.

These letters also show how Edma continued to influence Berthe’s mindset, even from afar. Her moral clarity and balanced perspective acted as a stabilizing force in Berthe’s life, long after their physical separation.

A Sister’s Influence That Endured Decades

Edma’s impact lasted far beyond the period when she sat as a model. Her legacy continued through the values she instilled, the letters she wrote, and the example she set. For Berthe, Edma remained a symbol of goodness, calm, and faithfulness—qualities that endured in her art even after her death.

Though art history often overlooks figures like Edma, her contributions are preserved in the visual language and emotional tones of her sister’s paintings. She may not have painted beyond her youth, but she left her mark all the same.

The Moral of Edma’s Story: A Muse Rooted in Family

Edma Morisot’s life offers a compelling alternative to the sensationalized narratives so often found in art history. She did not defy her era’s values—she upheld them with grace. She was not loud, rebellious, or confrontational, yet her influence helped shape one of the most important female painters of the 19th century. Her story is proof that the muse need not be a seductress, a scandal, or an icon. Sometimes, the muse is a sister who listens, a woman who sits patiently, and a heart that leads quietly.

Her choices illustrate the richness and dignity of traditional roles. As wife and mother, she supported her family with dedication. As sister and model, she inspired greatness not through self-promotion but through steadfast presence. She never demanded the spotlight, yet her example continues to shine in the works her sister left behind.

This is not a tale of a woman overshadowed or silenced. It is the story of a woman who understood her role in the greater good of her family and accepted it with serenity. Edma’s contributions—though largely invisible to the public eye—are written in every brushstroke Berthe ever painted with love, memory, and respect.

Modesty as a Lasting Legacy

Edma’s strength was in her stillness, her consistency, and her deep sense of purpose. She never needed to redefine herself because she understood who she was: a devoted sister, a loyal wife, and a graceful woman of conviction.

Her modesty was not weakness—it was the silent armor of dignity. Her presence in Berthe’s early works continues to remind viewers of the power found in poise and inner beauty.

Lessons in Grace and Commitment

There is much to be learned from Edma’s life. In a world increasingly drawn to spectacle, she is a timeless reminder that restraint and devotion have their own kind of brilliance. She was a muse without a crown, a foundation without fanfare.

Timeless Lessons from Edma’s Life

- Quiet duty can leave lasting impact

- Family is a foundational influence

- Artistic inspiration is not always public

- Modesty enhances beauty

- A muse need not seek the spotlight

Conclusion — Edma Morisot: The Silent Architect of Genius

Though she never sought the acclaim of the art world, Edma Morisot helped shape one of its most enduring voices. Her role as Berthe Morisot’s sister, model, and moral compass left an indelible mark on the Impressionist movement, even if her name rarely appears in textbooks. She was the silent architect behind some of Berthe’s most thoughtful and emotional works.

Edma reminds us that true influence doesn’t always require fame. Her life, grounded in faith, family, and quiet constancy, is a testament to the lasting power of tradition. She represents a kind of muse often forgotten—one rooted in love, not vanity.

In honoring Edma Morisot, we recognize the unseen contributions that uphold greatness. She is not a forgotten footnote but a central figure in the story of 19th-century art—a woman whose example continues to inspire, not through rebellion, but through resolve.

Honoring the Hidden Pillars of Art

Every masterpiece rests on a foundation, and in the case of Berthe Morisot, that foundation was Edma. Her example teaches us that supporting roles are no less critical than starring ones.

In celebrating her life, we restore balance to a story too often told only from the spotlight.

An Enduring Symbol of Feminine Virtue

Edma’s life represents the ideal of a woman devoted to something greater than herself. She walked a path of humility and left a legacy of strength. In a time when character is often overlooked, hers is a story worth remembering.