Long before its sleek skyline emerged from the desert and the glass dome of the Louvre Abu Dhabi shimmered over Saadiyat Island, Abu Dhabi was a modest coastal settlement known for little more than pearl diving and tribal politics. In less than a century, however, it has undergone one of the most astonishing transformations in global history—economically, architecturally, and culturally. And at the heart of that metamorphosis lies a deliberate and strategic cultivation of art and culture. To understand the art history of Abu Dhabi is to trace a journey from tradition-bound tribal crafts to a multi-billion-dollar cultural vision with global reach.

This introductory chapter serves to orient us in that journey. It highlights the underlying forces that propelled Abu Dhabi from obscurity to international acclaim, particularly through the lens of cultural production. While oil wealth provided the means, it was visionary leadership and a deepening engagement with both Islamic heritage and global modernity that framed art as not only an aesthetic endeavor but a form of nation-building.

In the early 20th century, the Trucial Coast, as it was then called under British protection, was a marginal zone in global terms—its communities sustained by date farming, fishing, and pearl diving. Artistic expression existed, but it was embedded within utilitarian and spiritual contexts. Women wove intricate sadu textiles, men carved wood and metal with geometric motifs, and mosques echoed with centuries of Islamic architectural tradition. These early forms were not separate from life—they were life, expressed through ornament, ritual, and storytelling.

When oil was discovered in the 1950s and production ramped up in the following decade, the influx of wealth dramatically shifted Abu Dhabi’s trajectory. The ruling Al Nahyan family, particularly Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, recognized that a nation was not built on infrastructure alone. He championed the integration of culture and identity into the national development plan. From the 1970s onward, art became part of a broader social contract—a way to bind together the rapidly modernizing state with its cultural past.

This process intensified in the 21st century. Facing globalization and a post-oil future, Abu Dhabi began investing heavily in the arts—not just to educate its own citizens or preserve heritage, but to position itself on the world stage. The Saadiyat Cultural District became a symbol of this ambition. Designed to house institutions like the Louvre Abu Dhabi, the future Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, and a national museum dedicated to Zayed’s legacy, it was a statement: that Abu Dhabi was not only a financial capital but a cultural one.

What makes this art history unique is its blend of revivalism, futurism, and diplomacy. It doesn’t follow a linear Western model of artistic evolution but intertwines heritage, policy, and international cooperation. Abu Dhabi’s art history is not only about artists—it is also about architects, curators, rulers, laborers, and educators. It’s about how soft power operates through aesthetics, how identity is negotiated in museum galleries, and how tradition is not merely preserved but transformed through global dialogue.

As we move through the subsequent chapters, we will unpack the distinct phases of this journey: the pre-oil crafts, Islamic design influences, the pivotal role of Sheikh Zayed, the emergence of institutions like the Cultural Foundation, the ambition behind the Saadiyat Island mega-project, and the contributions of Emirati artists pushing boundaries today. Along the way, we’ll confront the tensions between spectacle and authenticity, inclusion and erasure, and tradition and innovation.

This is the story of Abu Dhabi’s art—not simply as a mirror of its society, but as an active force shaping what that society is, and what it might become.

Pre-Oil Era Aesthetics: Tribal Crafts and Bedouin Heritage

Before skyscrapers pierced the skyline and international museums dotted its coastline, Abu Dhabi’s artistic expression thrived in a vastly different context—one of nomadism, scarcity, and communal resilience. In the centuries preceding the oil era, the region that would become the United Arab Emirates was home to Bedouin tribes whose aesthetic sensibilities were intimately tied to their environment and way of life. The art they produced was not created for galleries or patrons but emerged from lived necessity, spiritual expression, and cultural continuity. To understand Abu Dhabi’s modern cultural ambitions, one must first appreciate the profound artistic language that developed in its deserts and along its coasts.

The Bedouins—nomadic Arab tribes who traversed the harsh deserts of the Arabian Peninsula—were the cultural backbone of the region for centuries. In a land where survival depended on mobility, adaptability, and communal cooperation, artistic expression was integrated into the fabric of daily life. The objects created served multiple functions: practical, decorative, spiritual, and social. In this context, art was not a luxury; it was a necessity imbued with meaning.

One of the most emblematic forms of traditional art in pre-oil Abu Dhabi was sadu weaving, a craft practiced primarily by women. Using wool from camels, goats, and sheep, women spun and wove textiles into richly patterned fabrics that adorned tents, saddles, cushions, and camel bags. These textiles were not only functional but also communicative—each tribe had distinct motifs and color palettes that signaled identity, history, and social status. The rhythmic geometry of sadu, with its diamonds, chevrons, and zigzags, reflects a visual language that echoes Islamic design principles, even as it remained rooted in oral tradition and improvisation.

Along the coast, fishing and pearling communities developed their own material culture. Boat building, or dhow craftsmanship, was not only a technical skill but an art form in its own right. The graceful curves of wooden vessels, shaped by hand and passed through generations of master builders, reflect a deep knowledge of material and sea. Decorative elements such as carved rudders or painted hulls elevated the boats beyond mere tools—they became symbols of prosperity and pride.

Another significant expression of pre-oil artistic culture lies in jewelry and adornment. Bedouin women wore elaborate silver jewelry—necklaces, bangles, earrings, and amulets—not only as ornaments but as portable wealth and protective talismans. Each piece was handcrafted, often engraved with symbols thought to guard against evil or bring fertility and good fortune. The use of silver rather than gold, which was rare, gave the jewelry a distinct aesthetic that reflected both the environment and spiritual beliefs.

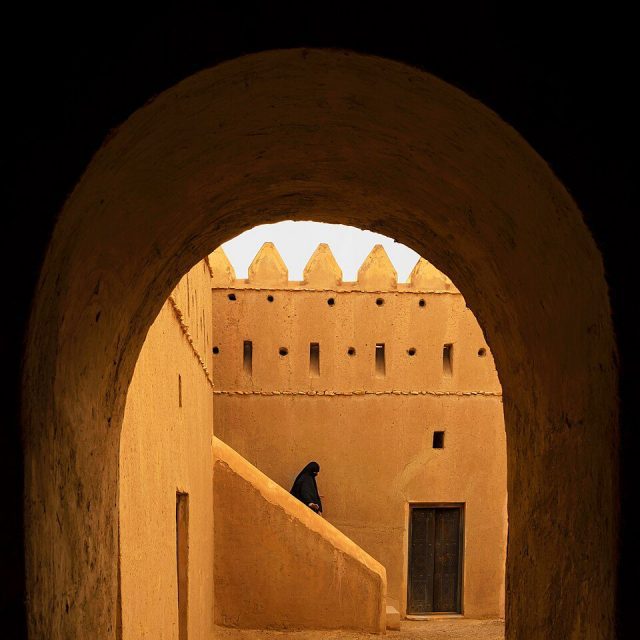

Architecture, too, bore aesthetic consideration even in its simplicity. Traditional areesh houses—built from palm fronds—offered shelter during scorching summers and reflected ingenious responses to climate and resources. The layout of desert dwellings and defensive forts, made from coral stone or mud brick, emphasized airflow, communal space, and geometric harmony. Windows were rare, but when present, they were often adorned with gypsum latticework or intricate mashrabiya screens, diffusing light while maintaining privacy.

Despite the limited availability of materials, artisans made the most of what they had. Camel bone, seashells, palm fibers, henna, and natural dyes all became media through which creativity was expressed. Henna painting, especially during weddings and festivals, transformed bodies into canvases. Meanwhile, oral poetry and storytelling added a performative dimension to the aesthetic life of the community, preserving collective memory and transmitting values across generations.

It is important to recognize that in pre-oil Abu Dhabi, there was no dichotomy between “art” and “craft.” Western categories that separate fine art from utilitarian objects do not neatly apply here. The creative output of this era was holistic—woven into the routines of domestic life, seasonal migrations, and religious rituals.

Colonial ethnographers and early visitors to the Gulf often overlooked or dismissed this cultural richness. Yet for Emiratis today, these traditions form the bedrock of national identity. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, as Abu Dhabi developed a global cultural profile, there has been a conscious revival and institutional support for this heritage. Organizations such as the Emirates Heritage Club, the Department of Culture and Tourism – Abu Dhabi, and initiatives like Al Ghadeer UAE Crafts work to preserve and promote traditional crafts not merely as nostalgic artifacts but as living practices.

This resurgence of interest has also inspired contemporary artists who draw on ancestral aesthetics to engage with modern themes. For instance, Emirati artist Fatma Lootah incorporates traditional textiles and henna motifs in abstract forms, linking past to present through visual language.

In sum, the pre-oil artistic heritage of Abu Dhabi is not a prelude to modernity—it is a vital, dynamic component of the emirate’s cultural DNA. It shaped the visual sensibility, material knowledge, and symbolic vocabulary that continues to inform artistic practice today. As we turn to the next stage—Islamic artistic influence and its interplay with these indigenous forms—we will see how spiritual and architectural traditions added new layers of complexity to Abu Dhabi’s aesthetic landscape.

Islamic Artistic Influence and Religious Aesthetics

While the tribal and Bedouin art forms of pre-oil Abu Dhabi developed from environmental necessity and oral tradition, they existed alongside—and were increasingly shaped by—the broader currents of Islamic artistic expression. From the early Islamic period onward, the Arabian Peninsula, including the coastal regions that would become the UAE, became part of a vast aesthetic and spiritual world bound together by the Arabic language, the Qur’an, and shared values around beauty, order, and meaning.

In Abu Dhabi, Islamic art was not imported wholesale from distant centers like Damascus, Cairo, or Baghdad, but absorbed gradually, filtering through religious practices, trade routes, and the architecture of mosques. Its influence was subtle yet profound, transforming everything from calligraphy to spatial design. Unlike European traditions that often exalted figurative representation, Islamic art embraced abstraction, geometry, and aniconism—a focus on non-figurative decoration in deference to spiritual concerns. This resulted in a rich visual vocabulary that prized unity, symmetry, and repetition as reflections of divine order.

Perhaps the most enduring and sacred form of Islamic art in Abu Dhabi is calligraphy—the stylized rendering of Arabic script, particularly Qur’anic verses. Calligraphy transcended mere writing; it became a spiritual act and a visual form of worship. Even in modest mosques and homes, verses from the Qur’an were rendered with reverence, using locally available materials—sometimes scratched into plaster, inscribed on wooden panels, or sewn into textiles. The act of writing was itself devotional, and the beauty of the script was meant to reflect the perfection of the words it conveyed.

This reverence for text also played a role in educational settings. Small Qur’anic schools, known as kuttab, were common in the pre-modern Gulf, where children learned to read and write Arabic using ink boards. These early lessons helped seed both literacy and aesthetic appreciation, forming a cultural baseline for the reverence of calligraphy that persists to this day. In contemporary Abu Dhabi, this legacy is celebrated in institutions such as the Qasr Al Hosn, which exhibits historical manuscripts and calligraphic traditions, and through contemporary practitioners who experiment with form while maintaining classical respect.

Architecture was another primary arena for Islamic artistic expression in Abu Dhabi. While the region did not produce monumental architecture on the scale of Andalusia or Persia, it absorbed key Islamic principles and adapted them to its climate and resources. The earliest mosques in Abu Dhabi, built from coral stone, palm trunks, and gypsum, followed simple designs but included distinct Islamic features: mihrabs (prayer niches facing Mecca), minarets (towers from which the call to prayer was issued), and domes where possible.

These mosques employed geometric and floral motifs that aligned with broader Islamic aesthetics. Walls were often left plain, yet adorned with repeated patterns symbolizing infinity and divine unity. Such designs reflected an Islamic worldview that saw beauty not as individual expression, but as a pathway to contemplating God. The logic of these patterns—the way they expand endlessly without hierarchy—mirrored theological notions of tawhid (the oneness of God). These aesthetics shaped not only places of worship but also domestic architecture and crafts.

One remarkable synthesis of Islamic and local traditions in Abu Dhabi can be seen in mashrabiya screens—latticed wooden or gypsum windows that filtered light and maintained privacy. These screens were not merely functional but imbued with symbolic meaning: they controlled what could be seen and unseen, both visually and socially, reflecting values of modesty and contemplation. Their intricate geometry became a motif repeated across architecture, textiles, and even contemporary design.

In the 21st century, the resurgence of interest in Islamic art has been both scholarly and institutional. The Louvre Abu Dhabi houses an extensive Islamic art collection, juxtaposing it with global traditions to show its universal resonance. Exhibits often include early Qur’anic manuscripts, astrolabes, carved wooden panels, and intricately glazed ceramics from across the Islamic world. This global contextualization reinforces the idea that Abu Dhabi, while a latecomer to the museum world, is asserting itself as a custodian of Islamic heritage.

Modern architects have also drawn on Islamic principles in ambitious new projects. The Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque, completed in 2007, is a towering example—combining Ottoman, Mughal, and Moorish styles into a modern structure that embodies the unity of Islamic civilization. Its massive white marble domes, floral inlays, and calligraphy-covered walls make it both a place of worship and a declaration of cultural ambition. It is the largest mosque in the UAE and a symbol of Abu Dhabi’s investment in religious and aesthetic legacy.

Contemporary artists and designers in Abu Dhabi also engage deeply with Islamic art. Ebtisam Abdulaziz, for instance, blends conceptual art with Islamic geometry and mathematical systems, using abstraction to explore identity and logic. Others use calligraphy in multimedia works, expanding the form beyond ink and paper into digital and sculptural dimensions. This continuity demonstrates how Islamic art remains a living tradition, not a static heritage.

In this way, Islamic artistic influence in Abu Dhabi is not confined to the past. It continues to inform the city’s evolving identity, linking spiritual devotion to visual sophistication. Whether through the reverent curve of a calligraphic line, the tessellation of a courtyard floor, or the serene repetition of architectural motifs, Islamic aesthetics remain deeply woven into Abu Dhabi’s cultural fabric.

As we turn next to the architectural evolution of the modern city, we will see how these Islamic foundations intersect with global modernism, creating a hybrid language that defines Abu Dhabi’s skyline and artistic aspirations.

Architecture as Art: The Urban Aesthetic of Modern Abu Dhabi

To walk through Abu Dhabi today is to move through a curated collage of ambition. Towering glass and steel structures coexist with domes and arches drawn from centuries of Islamic architecture. Coastal promenades are lined with futuristic museums while palm-lined avenues pass traditional forts and mosques. In Abu Dhabi, architecture is not merely functional—it is artistic, symbolic, and deeply political. It tells the story of a city that has used urban design as a primary medium for self-expression, blending heritage and modernity in a distinctive visual language.

Architecture in Abu Dhabi, especially since the 1970s, has served multiple roles: it is a mirror of prosperity, a vehicle of cultural diplomacy, and a tool of nation-building. More than any painting or sculpture, it is architecture that has shaped how the world sees the city—and how the city sees itself. The built environment has become a canvas on which Abu Dhabi has projected its aspirations: regional leadership, global relevance, and cultural depth.

The story begins in earnest after the unification of the United Arab Emirates in 1971. Under the leadership of Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, Abu Dhabi underwent a radical transformation. From a small desert settlement of coral stone houses and mud brick forts, it became a capital with soaring ambitions. Yet Sheikh Zayed was no mere modernizer. His vision for Abu Dhabi’s development emphasized the integration of tradition and innovation. He wanted a city that embraced the future without erasing the past.

One of the first expressions of this vision was the preservation and restoration of Qasr Al Hosn, Abu Dhabi’s oldest building. Originally constructed in the 18th century as a watchtower, and later expanded into a fort and royal residence, Qasr Al Hosn became a symbol of continuity—a physical anchor amid rapid change. Its whitewashed walls and austere geometry now contrast strikingly with the glass towers that surround it, reinforcing its role as a monument to memory.

The 1980s and 1990s saw the rise of modernist buildings that reflected global architectural trends. Office towers, government buildings, and residential complexes multiplied, often designed by foreign firms. These structures brought international expertise but often lacked local resonance. In response, there emerged a conscious effort to embed cultural identity into the skyline. Architects began incorporating Islamic motifs, mashrabiya patterns, and domed elements into high-rises and civic buildings. This hybrid style—modern materials with traditional references—has become one of Abu Dhabi’s defining architectural signatures.

A notable example is the Al Bahr Towers, completed in 2012. Designed by Aedas Architects and engineered with environmental sustainability in mind, the twin towers feature a dynamic mashrabiya-style façade that opens and closes in response to sunlight. This marriage of heritage aesthetics and cutting-edge technology is emblematic of Abu Dhabi’s approach: a reverence for the past combined with a hunger for innovation.

But the most transformative architectural project of the 21st century has been Saadiyat Island—a massive cultural district that positions architecture as art on a global scale. The centerpiece is the Louvre Abu Dhabi, designed by Jean Nouvel. With its enormous domed roof—composed of interlocking star patterns casting intricate “rain of light” shadows—the building is both a feat of engineering and a poetic homage to traditional Arab architecture. Nouvel described it as “a museum city in the sea,” and its structure deliberately recalls the medina, with a network of pavilions, plazas, and reflecting pools beneath the dome.

Adjacent to it, plans for the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, designed by Frank Gehry, promise another architectural icon, with deconstructed forms evoking both desert dunes and futuristic abstraction. Meanwhile, Zayed National Museum, designed by Norman Foster, will combine soaring steel wings with references to falconry and Islamic geometry. Each of these projects deploys architecture not just as housing for art, but as art itself—objects of international admiration and cultural signaling.

Outside of Saadiyat, architecture continues to shape civic identity. The Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque, completed in 2007, is perhaps the most iconic building in the UAE. Designed by Syrian architect Yousef Abdelky, it blends Moorish, Mamluk, and Mughal influences into a gleaming white complex of domes, minarets, and reflective pools. Housing the world’s largest hand-knotted carpet and among the largest chandeliers, it is both a place of worship and a national statement—a convergence of craftsmanship, spirituality, and monumentalism.

Public spaces in Abu Dhabi have also been curated with architectural artistry. The Corniche—a sweeping waterfront promenade—combines modern landscaping with traditional ornamentation. Government buildings often feature massive courtyards and symmetrical layouts inspired by Islamic urban planning, while residential neighborhoods incorporate Arabic arches, shaded alleys, and textured façades that create visual harmony.

Crucially, the architecture of Abu Dhabi is not only vertical. It is experiential. Planners and artists have collaborated on creating environments that foster interaction with the built environment—through shade, light, and rhythm. In recent years, sustainability has become a key factor in this dialogue. The Masdar City project, a planned eco-city on the outskirts of Abu Dhabi, experiments with vernacular architectural techniques (like narrow streets and wind towers) to reduce heat and energy consumption while maintaining a futuristic aesthetic.

Taken as a whole, Abu Dhabi’s architectural journey is not about copying Dubai’s hyper-modern skyline, nor mimicking Western capitals. It is about developing a hybrid urban aesthetic—where tradition informs design, and design becomes a language of ambition. Architecture here is not static; it is performative, narrative, and strategic. It is art scaled up to city level.

As we next explore Sheikh Zayed’s personal vision for cultural nation-building, we’ll see how his approach to architecture as an expression of identity laid the groundwork for everything that followed—especially in the arts and heritage sectors.

The Founding Vision: Sheikh Zayed and Cultural Nation-Building

In the story of Abu Dhabi’s transformation from a desert emirate to a cultural capital, few figures loom as large as Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan. Revered as the founding father of the United Arab Emirates, his leadership was pivotal not only in forging a nation but in shaping its cultural and artistic identity. While oil revenue provided the means for development, it was Zayed’s vision that gave that development a sense of purpose—anchored in heritage, guided by religion, and open to the world.

Born in 1918 in Abu Dhabi’s Qasr Al Hosn fort, Sheikh Zayed grew up in an era when the emirate was marked by scarcity and isolation. He witnessed firsthand the rhythms of Bedouin life, the humility of tribal governance, and the spiritual centrality of Islam. These early experiences deeply informed his later policies. When he became Ruler of Abu Dhabi in 1966 and then President of the UAE in 1971, he brought to his new role a belief that rapid modernization must not come at the cost of cultural memory.

Sheikh Zayed saw art and heritage not as elite pursuits, but as collective memory—a means to unify a rapidly urbanizing and diversifying society. This was no small task. In the early 1970s, Abu Dhabi was undergoing seismic changes: an influx of oil wealth brought foreign workers, international architects, and rapid urban expansion. The cultural fabric of the emirate, once shaped by oral traditions and tribal customs, risked being overshadowed by glass towers and imported lifestyles.

To counter this, Sheikh Zayed championed a policy of cultural preservation, even as he encouraged modernization. One of his earliest directives was the documentation and revival of traditional crafts, particularly those associated with Bedouin and coastal life—sadu weaving, palm frond construction, falconry, and pearl diving. These were not simply hobbies to be nostalgically remembered; they were framed as vital expressions of Emirati identity.

In 1981, Zayed established the Cultural Foundation in Abu Dhabi—one of the first major government initiatives to institutionalize the arts in the UAE. Housed near Qasr Al Hosn, the foundation was a landmark: part museum, part library, part performance space. It quickly became a hub for exhibitions, lectures, poetry readings, and traditional music performances. For many Emiratis, it was their first encounter with art presented in a curated, civic setting. The foundation played a crucial role in nurturing early local artists and instilling pride in heritage-based creativity.

But Zayed’s cultural vision extended beyond nostalgia. He understood that a strong national identity required strategic cultural diplomacy. By inviting international exhibitions, sponsoring archaeological digs, and supporting religious and historical scholarship, Abu Dhabi positioned itself as a responsible steward of Islamic and Arab civilization. Zayed believed that the UAE’s contributions to global culture could be grounded in its heritage—if only it was properly preserved and elevated.

His architectural decisions reflected this balance. While he approved ambitious modernization projects, he also insisted that mosques, public buildings, and even private homes maintain architectural features that reflected Islamic values: domes, courtyards, wind towers, and geometric ornamentation. He was particularly adamant about the inclusion of green spaces, believing that parks and gardens not only beautified the city but echoed the Qur’anic symbolism of paradise.

The ultimate expression of Zayed’s cultural vision came later in life, with the planning of the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque—a project he did not live to see completed but which remains a monument to his ideals. Designed to combine Islamic architectural traditions from across the Muslim world, the mosque was intended as a place of worship, reflection, and artistic inspiration. Its grandeur—marked by white marble domes, floral mosaics, and a breathtaking central courtyard—is matched by its accessibility. Visitors from all faiths are welcomed, echoing Zayed’s belief in hospitality and dialogue.

Zayed’s approach to cultural nation-building was not without its complexities. His policies were shaped by a patriarchal worldview, and much of the early cultural infrastructure centered traditional, often male-dominated narratives of heritage. Still, his emphasis on education, documentation, and institutional support laid the groundwork for the UAE’s future cultural ambitions. He insisted that every child in the country should know their history—and that the arts were a vital means of telling it.

Today, many Emirati artists, curators, and educators trace their opportunities back to the systems put in place during Sheikh Zayed’s rule. His legacy endures in the work of institutions like the Department of Culture and Tourism – Abu Dhabi, the National Archives, and the growing number of festivals, museums, and cultural centers throughout the city.

In a region often caricatured as a land of overnight skyscrapers and imported luxury, Sheikh Zayed’s cultural legacy offers a more nuanced narrative: one in which a Bedouin-raised ruler used oil wealth not just to build infrastructure, but to build identity. His belief that art and heritage are foundational to national strength continues to shape Abu Dhabi’s cultural policy today.

As we move next to the Abu Dhabi Cultural Foundation and the Rise of National Museums, we’ll explore how the institutional legacy of Sheikh Zayed’s vision developed into a full-fledged cultural ecosystem.

Abu Dhabi Cultural Foundation and the Rise of National Museums

If Sheikh Zayed laid the philosophical and political foundation for cultural preservation in the UAE, the Abu Dhabi Cultural Foundation, established in 1981, became the bricks and mortar of that vision. It was not just a building—it was a message. In a rapidly modernizing cityscape, the Cultural Foundation stood as an emblem of intention: that a new nation could embrace the future without discarding the past, and that art, literature, and heritage had a permanent, civic place in its development.

Located in the heart of Abu Dhabi, adjacent to the historic Qasr Al Hosn fort, the Cultural Foundation quickly became the epicenter of the capital’s burgeoning cultural scene. Architecturally, the building reflected this dual commitment. Its design, by Egyptian architect Abdelrahman Makhlouf, drew on traditional Arab-Islamic motifs—colonnades, courtyards, geometric screens—while utilizing modern construction techniques. It was a physical articulation of the UAE’s core ambition: modernization without Westernization.

The Cultural Foundation was many things at once. It housed a national library, a performing arts theater, a visual arts gallery, workshops, and exhibition halls. Unlike the private salons or palace collections of other regions, it was a public space—free and open to residents, artists, students, and visitors. It staged poetry recitals, hosted traveling exhibitions, and curated retrospectives of Emirati artists before such efforts were widely seen as essential. It also launched educational programs that encouraged schoolchildren to engage with local heritage and arts from a young age.

Perhaps most importantly, the Foundation played a formative role in supporting the first generation of contemporary Emirati artists. Figures like Hassan Sharif, Mohammed Kazem, and Abdul Qader Al Rais found in the Foundation a platform from which to exhibit and debate. Though Sharif’s conceptual and often minimalist work would later provoke international attention (and occasional domestic controversy), the Cultural Foundation was one of the few early institutions willing to nurture and showcase such experimental voices. It became a kind of laboratory for local modernism—a place where artists could grapple with identity, tradition, and the aesthetics of change.

The Foundation’s reach extended beyond the visual arts. It played host to intellectual debates, lectures, film screenings, and performances. Renowned Arab poets, musicians, and playwrights visited Abu Dhabi through its invitation. In doing so, the city began to position itself not just as a steward of local heritage, but as a participant in the broader Arab cultural sphere. This was especially important in the 1980s and 1990s, when regional conflict and economic volatility elsewhere in the Arab world created cultural vacuums that the UAE was increasingly poised to fill.

The success of the Cultural Foundation also helped set the stage for a more institutionalized museum culture in Abu Dhabi. Until the early 2000s, museums in the emirate were limited in number and largely focused on ethnographic preservation. The Heritage Village and smaller local museums, such as the Al Ain National Museum, were established to showcase traditional crafts, Bedouin life, and archaeological finds from the region. These institutions were valuable but primarily retrospective, presenting a static view of Emirati culture.

This began to change in the 2000s, when Abu Dhabi’s leadership initiated plans to expand its cultural reach in a more global, future-oriented direction. These efforts led directly to the Saadiyat Island Cultural District project, but their roots are traceable to the groundwork laid by the Cultural Foundation. The same principles—public accessibility, dialogue between past and present, and investment in arts education—would be scaled up dramatically in the coming years.

One turning point in this transition was the launch of Abu Dhabi Authority for Culture and Heritage (ADACH) in 2005, later merged into the Department of Culture and Tourism – Abu Dhabi (DCT Abu Dhabi). This institutional shift marked a more centralized, strategic approach to culture. While the Cultural Foundation had been a focal point of organic artistic activity, DCT Abu Dhabi aimed to integrate cultural development with tourism, diplomacy, and economic diversification. It expanded museum planning, supported international partnerships, and brought a long-term vision to cultural investment.

In 2018, after a long renovation and restoration process, the Cultural Foundation itself reopened to the public with a renewed purpose. While retaining its original mandate, it embraced new technology, hosted contemporary exhibitions, and incorporated global dialogues into its programming. Exhibits like “The Red Palace” by Sultan Bin Fahad and retrospectives on early modern Arab artists demonstrated its evolution into a modern arts institution without losing sight of its roots.

The revival of the Foundation also symbolizes a broader shift in how Abu Dhabi sees culture: not just as a matter of heritage or entertainment, but as infrastructure—as essential to civic life as roads, hospitals, and schools. In this view, museums and cultural centers are not luxuries, but public goods: they shape memory, nurture identity, and inspire future generations.

Today, Abu Dhabi boasts a growing constellation of national museums and cultural hubs, from the Etihad Museum and Qasr Al Watan to the soon-to-be-completed Guggenheim Abu Dhabi. Yet the Cultural Foundation remains the symbolic heart of this landscape—a quiet but powerful reminder that the UAE’s cultural ambitions began not with international franchises, but with a belief in the power of homegrown creativity.

In our next chapter—The Saadiyat Island Project: Art as Soft Power—we’ll examine how Abu Dhabi scaled its cultural ambitions to the global stage, using architecture, museum diplomacy, and curatorial strategy to reposition itself as a leading center of art in the 21st century.

The Saadiyat Island Project: Art as Soft Power

At the dawn of the 21st century, Abu Dhabi stood at a crossroads. The emirate had successfully built infrastructure, fostered national identity, and supported cultural initiatives through institutions like the Cultural Foundation. But global visibility in the arts—on par with cities like Paris, London, or New York—remained elusive. To fill that gap, Abu Dhabi turned to an audacious idea: to build, from the ground up, an entire cultural district on a single island, designed by the world’s most renowned architects, and anchored by partnerships with elite international institutions. The result was the Saadiyat Island Cultural District—a bold declaration that art would be central to Abu Dhabi’s global soft power strategy.

The name “Saadiyat” means “happiness” in Arabic, and the island, just 500 meters off the coast of Abu Dhabi, was designated to become the city’s cultural crown jewel. The master plan, unveiled in the mid-2000s, was staggering in its ambition. It included the Louvre Abu Dhabi, Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, Zayed National Museum, a Performing Arts Centre, and a maritime museum. Each would be housed in bespoke buildings designed by a “starchitect”: Jean Nouvel, Frank Gehry, Norman Foster, Zaha Hadid, and Tadao Ando, respectively. Collectively, they would form a museum district without precedent in the Arab world, rivalling global capitals in both scope and investment.

But Saadiyat was never just about buildings. It was a strategic exercise in cultural diplomacy. By collaborating with the world’s leading museums and cultural brands, Abu Dhabi sought to send a message: that the UAE was a bridge between civilizations, a hub for intercultural dialogue, and a patron of global creativity. The emirate’s leadership saw in art a powerful tool—not only to diversify the economy through tourism, but to shape narratives, build prestige, and elevate the country’s soft power on the world stage.

The most visible and successful of these partnerships was with France, culminating in the Louvre Abu Dhabi, which opened in 2017 after a decade of planning. The agreement, signed in 2007, was more than a branding exercise. It established a long-term collaboration that included loaned artworks from French national museums, joint exhibitions, staff training, and curatorial consultation. In return, Abu Dhabi paid over €1 billion—a sum that underscored both its ambition and its seriousness.

The Louvre Abu Dhabi, designed by Jean Nouvel, is a work of art in itself. Its vast dome—180 meters in diameter—is composed of nearly 8,000 stars layered to create a “rain of light,” casting intricate shadows across the whitewashed galleries below. Unlike traditional museum layouts that separate cultures by geography or chronology, the Louvre Abu Dhabi employs a “universal museum” concept. Its galleries mix Islamic manuscripts with European oil paintings, Buddhist sculptures with African masks—encouraging visitors to see the connections between civilizations.

This curatorial philosophy aligns with Abu Dhabi’s diplomatic vision: to present the emirate as a neutral ground for global narratives, a place where East meets West on equal footing. The museum has displayed works by da Vinci, Van Gogh, and Picasso alongside ancient Mesopotamian relics and contemporary Arab art. The goal is to inspire dialogue, not hierarchy—a direct counterpoint to colonial-era museum practices.

But not all aspects of the Saadiyat project have been smooth. The district has faced criticism from several directions. Human rights organizations, notably Human Rights Watch, have raised concerns about labor conditions on the island, particularly the treatment of migrant workers involved in construction. Despite Abu Dhabi’s attempts to implement labor reforms and codes of conduct, scrutiny has persisted. This has sparked broader debates about the ethics of cultural production in the Gulf and the responsibilities of partnering institutions.

Critics have also questioned the authenticity of importing foreign cultural brands, arguing that museums like the Louvre and Guggenheim may overshadow local narratives rather than amplify them. Others worry about the sustainability of such mega-projects, given the long delays in construction (as of 2025, Guggenheim Abu Dhabi is still pending completion, although the structure is well underway).

Yet despite these challenges, Saadiyat Island has already had a transformative effect. It has altered how the world perceives Abu Dhabi, recasting it not only as a center of oil wealth but as a serious player in the global cultural economy. The project has also galvanized the regional arts ecosystem, inspiring more galleries, art schools, fairs, and private collectors to engage with the UAE.

Moreover, the Louvre Abu Dhabi’s success has encouraged further investment in cultural infrastructure. The Abrahamic Family House, inaugurated in 2023 nearby, brings together a mosque, a church, and a synagogue on one site—another architectural and cultural gesture toward inclusivity and intercultural harmony. Meanwhile, new initiatives on Saadiyat, including an art research center, residency programs, and a children’s museum, are beginning to fill out the ecosystem around the flagship institutions.

The Saadiyat project reflects a key principle of Abu Dhabi’s cultural policy: that art is not only for Emiratis—it is a platform for global engagement. While rooted in Islamic aesthetics and regional identity, the island speaks to a post-national world, where cultural capital flows across borders, and where cities compete not just in GDP but in symbolic value.

In the next section, we’ll explore how the Louvre Abu Dhabi, in particular, has shaped new narratives in museum practice, challenging Western-centric histories and inviting a global rethinking of what it means to collect, display, and contextualize art.

Louvre Abu Dhabi: A New Model for Global Museum Narratives

When the Louvre Abu Dhabi opened its doors in November 2017, it wasn’t just the debut of a new museum—it was a recalibration of global cultural dynamics. Situated in the heart of the Gulf and designed by architect Jean Nouvel to shimmer beneath a massive, floating dome, the museum quickly became a symbol of ambition, diplomacy, and a reimagining of what art institutions could be in the 21st century. It also challenged long-held assumptions about where major cultural centers could exist—and who gets to tell the story of art.

At first glance, the idea of placing a Louvre-branded museum in Abu Dhabi sparked controversy. Critics in France accused the government of “selling” national treasures to an oil-rich state, while others questioned the ethics of cultural franchising. But as the museum took shape, both physically and philosophically, it became clear that Louvre Abu Dhabi was not a replica—it was a reinvention.

The museum’s architecture itself sets the tone. Jean Nouvel’s design draws inspiration from Arab medinas and traditional Islamic architecture, yet it is resolutely futuristic. The dome, spanning 180 meters, is composed of eight layers of aluminum and stainless steel, forming a complex latticework that allows sunlight to filter through in dancing specks of light—a modern reinterpretation of the palm frond roofs found in traditional Emirati villages. Beneath the dome is a city of galleries, linked by open-air pathways and reflecting pools that make the entire complex feel like a cultural oasis.

But it is the curatorial strategy of Louvre Abu Dhabi that most distinguishes it from its European namesake. Rather than organizing its collection by national schools or historical periods, the museum embraces a universalist approach. Artworks from different cultures and epochs are displayed side by side, highlighting thematic and philosophical connections rather than geographic or chronological separations. A 3,000-year-old funerary stele from Egypt might share space with a Buddhist sculpture from Gandhara and a medieval Christian altarpiece—not to flatten their differences, but to suggest shared human experiences of death, spirituality, and transcendence.

This model reflects Abu Dhabi’s geopolitical ethos: the idea of the UAE as a bridge between civilizations, a pluralistic society open to dialogue. It also marks a deliberate break from the traditional Eurocentric museum model, which historically categorized non-Western cultures as peripheral or “ethnographic.” By placing African, Arab, Asian, and Indigenous art in conversation with European masterpieces, Louvre Abu Dhabi seeks to restructure the global narrative of art history.

This recontextualization is visible in some of the museum’s signature galleries. The “Universal Religions” gallery juxtaposes religious manuscripts from Islam, Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, and Buddhism, displayed not in competition but in mutual reverence. Another gallery explores the evolution of portraiture across cultures—from Roman busts to Mughal miniatures to modern photography. The effect is both educational and philosophical: it encourages viewers to see art not as a linear progression but as a web of interconnected visions.

The collection itself is a mix of acquisitions and long-term loans, mostly from French institutions under the 2007 intergovernmental agreement. Major institutions like the Louvre, Musée d’Orsay, Centre Pompidou, and Musée du Quai Branly regularly rotate artworks to Abu Dhabi. This system allows the museum to continually refresh its displays while also building its own permanent collection, which now includes pieces ranging from prehistoric tools and ancient Chinese ceramics to modern works by Ai Weiwei, Cy Twombly, and Emirati artist Abdul Qader Al Rais.

Importantly, the museum has also served as a platform for regional artists and curators. Exhibitions such as “Abstraction and Calligraphy: Towards a Universal Language” (2021) and “Art Here” (a recurring exhibition spotlighting artists from the Gulf) signal a commitment to integrating local voices into its global framework. The museum has also hosted seminars, residencies, and educational programs aimed at developing the next generation of art historians and curators from the region.

Despite its successes, Louvre Abu Dhabi has not escaped critique. Some question the reliance on French expertise, asking when Abu Dhabi will produce entirely homegrown museums of similar stature. Others raise concerns about accessibility—whether the museum’s high-concept approach is truly inclusive of the UAE’s diverse, multilingual population. But these challenges are part of the museum’s broader experiment: to build a space that is both global and grounded, elite and open, historical and forward-looking.

Louvre Abu Dhabi has already had significant ripple effects. It has inspired increased government funding for the arts, drawn international curators and scholars to the region, and prompted the development of satellite projects and adjacent institutions. It has also forced Western museums to reconsider their roles in a multipolar world—where artistic authority and interpretation can emerge from many centers, not just Paris or New York.

Perhaps most profoundly, the museum represents a reassertion of cultural agency. In a region long seen through the lens of conflict, oil, or exoticism, Louvre Abu Dhabi offers a counter-image: of a city where art history is being actively written and re-written, not simply inherited. It’s a place where the global story of creativity includes the Arab world as narrator, not just subject.

Next, we’ll turn to Contemporary Art Movements and Emirati Artists, exploring how local creators are pushing boundaries, drawing from tradition, and contributing to this evolving artistic identity from the inside out.

Contemporary Art Movements and Emirati Artists

While towering museums like the Louvre Abu Dhabi draw international acclaim, the true pulse of a city’s art scene lies with its living artists—those who engage with tradition, question identity, and use the tools of contemporary practice to imagine new futures. In Abu Dhabi, the emergence of a distinct Emirati art movement is one of the most compelling and complex developments in the city’s cultural history. It is a story of late blooming, radical experimentation, and a growing confidence to speak in a global visual language without abandoning local roots.

The development of contemporary art in Abu Dhabi—and the UAE more broadly—was, by global standards, a relatively recent phenomenon. Until the 1970s and 1980s, art was largely confined to crafts, calligraphy, and religious or decorative expressions. But as educational opportunities expanded and the country began to invest in cultural infrastructure, a first generation of modern artists emerged, many of them self-taught or educated abroad.

Among these pioneers, Hassan Sharif stands as a foundational figure. Though more closely associated with Dubai, his impact reverberates across the entire UAE art scene, including Abu Dhabi. Trained at the Byam Shaw School of Art in London, Sharif returned in the 1980s with a conceptual and minimalist approach that broke radically from traditional aesthetics. He began producing assemblages made from cheap, mass-produced objects—ropes, wire, newspapers—challenging ideas of value, originality, and cultural identity in a rapidly consumerizing society. His studio became a crucible for younger artists, many of whom would go on to define the contemporary art scene.

In Abu Dhabi, the emergence of a homegrown art community was slower but no less significant. Supported by institutions like the Cultural Foundation, artists such as Abdul Qader Al Rais blended modernist abstraction with Arabic calligraphy and Islamic geometry, creating a uniquely Emirati visual language. Others, like Mohammed Kazem, explored sound, light, and geographic coordinates as artistic media—questioning what it means to locate oneself in a rapidly changing world.

By the 2000s, a new generation of Emirati artists had begun to emerge, educated in local and international institutions, and often fluent in both Western art history and regional traditions. These artists tackled complex issues: gender, globalization, memory, post-colonialism, environmental degradation, and the politics of heritage. Their work reflected a society negotiating the tension between modernity and tradition, between global connectivity and cultural specificity.

Take, for example, Ebtisam Abdulaziz, whose work uses mathematical codes, language, and conceptual forms to interrogate systems of identity and power. Or Farah Al Qasimi, whose vividly composed photographs capture the surreal juxtapositions of Emirati life: malls and mannequins, domestic interiors, and fragmented bodies. Al Qasimi’s images explore the aesthetics of concealment and visibility, often critiquing the glossy image of Gulf modernity.

In recent years, female Emirati artists have become particularly prominent in shaping the narrative of contemporary art in Abu Dhabi. Artists like Manal AlDowayan, known for participatory installations and performance work, use art to explore themes of gender, mobility, and collective memory. Her projects—such as collecting stories from Saudi and Emirati women, or producing large-scale installations of prayer beads and driving licenses—underscore how contemporary art in Abu Dhabi is often deeply political, even when understated.

The infrastructure to support this burgeoning talent has grown in tandem. Institutions like Warehouse421, located in the Mina Zayed port area, offer residencies, exhibitions, and educational programs tailored to emerging artists. Backed by the Salama bint Hamdan Al Nahyan Foundation, it represents a more experimental, grassroots alternative to the monumental scale of Saadiyat’s museums. It has hosted exhibitions like “Bayn: The In-Between”, focusing on hybridity and post-migration identities, as well as shows highlighting GCC-wide artistic collaboration.

Meanwhile, art fairs and biennials have become key platforms for exposure. Abu Dhabi Art, launched in 2009, blends commercial and non-commercial presentations, and has steadily become a regional anchor, attracting galleries from across Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. The fair’s Beyond: Emerging Artists program offers commissioned projects for young local talents, placing their work in public spaces across the city and even into the desert.

Education, too, plays a central role. NYU Abu Dhabi’s Arts Center and Art Gallery have become hubs for academic and creative exchange, with exhibitions, artist talks, and performances that engage students and the public alike. Its programming often bridges regional and international perspectives, challenging the idea that Emirati art must exist in isolation from broader artistic dialogues.

Importantly, contemporary art in Abu Dhabi is not confined to the studio or gallery. Artists increasingly engage with the city itself as canvas, context, and material. Public art commissions, urban interventions, and socially engaged projects reflect a desire to move beyond institutional walls and speak directly to communities. Whether through sculpture in the park or digital installations in the desert, contemporary Emirati artists are claiming space—literally and metaphorically—in the national imagination.

This growing movement is still evolving. It faces challenges: censorship boundaries, limited critical discourse, and the need for more rigorous art education and critique. But it also enjoys unprecedented support, with increased patronage, regional visibility, and international recognition.

In the next section—Art Education and Creative Economies—we will look at how Abu Dhabi is investing in the next generation of artists, curators, and cultural workers, and how creative industries are becoming central to the emirate’s long-term development strategy.

Art Education and Creative Economies

The story of Abu Dhabi’s cultural ascent is not just about building museums or hosting international exhibitions—it’s about investing in people. While the city has attracted global attention through its architectural marvels and institutional partnerships, a quieter, but equally transformative effort has been taking place in classrooms, workshops, and studios across the emirate: the cultivation of a robust, self-sustaining creative economy anchored in education.

For a city that only decades ago had few formal educational institutions, Abu Dhabi has made remarkable strides in turning art education into a central pillar of its national development strategy. This is part of a broader vision—embodied in plans like UAE Vision 2030—to diversify the economy beyond oil and create new sectors driven by knowledge, innovation, and culture. In this future, artists, designers, curators, educators, and creative entrepreneurs are not peripheral—they are foundational.

One of the most influential players in this transformation is NYU Abu Dhabi. Since its opening in 2010 on Saadiyat Island, NYUAD has become a critical node in the city’s art ecosystem. The university’s Art Gallery serves as a research-based exhibition space that brings international artists to Abu Dhabi while highlighting regional voices. Its programming is deliberately rigorous, engaging with global issues—climate change, postcolonial identity, technological change—while fostering deep academic inquiry.

NYUAD’s interdisciplinary model has allowed students from across the world to explore studio art, art history, and curatorial practice in tandem with fields like political science or philosophy. Visiting artists, exhibitions, and public programs have turned the campus into a cultural microcosm—one where emerging Emirati artists rub shoulders with international peers, critics, and mentors.

But the educational infrastructure in Abu Dhabi extends beyond the ivory tower. Local initiatives such as the Art Center at NYUAD, Warehouse421, and programs under the Department of Culture and Tourism – Abu Dhabi have created a network of opportunities for training and mentorship. Warehouse421, in particular, has emerged as a vital hub for young creatives. Its offerings include artist residencies, professional development programs, and collaborative workshops that focus on everything from exhibition design to grant writing. These are not just about making art—they’re about making careers.

The Salama bint Hamdan Al Nahyan Foundation has also been instrumental in nurturing creative talent. Its SEED (Supporting Emirati Emerging Designers) and Art Grants programs provide financial and institutional support for early-career artists and designers. The foundation’s approach is long-term: it supports talent from incubation through public exhibition, helping them navigate the professional demands of the cultural sector.

On a broader level, Abu Dhabi’s cultural policy increasingly positions the arts as an economic engine. The government has launched initiatives like the Creative Media Authority and twofour54, a media and content creation zone offering training, workspace, and funding for entrepreneurs in film, animation, gaming, and design. These zones are meant to incubate startups and attract global players, but they also create downstream opportunities for local artists, scriptwriters, and multimedia designers.

Educational efforts have also expanded into K–12 curricula, with art and heritage studies now integrated more comprehensively into Emirati schools. Projects like the Lest We Forget initiative, launched by Salama bint Hamdan Al Nahyan Foundation, encourage students and families to document personal histories through photographs, interviews, and creative responses—blurring the line between archive and art.

Public-private partnerships are another key mechanism. Collaborations between educational institutions and museums—such as training curators at Louvre Abu Dhabi or conservationists at Zayed National Museum—create clear career pathways. These efforts ensure that cultural institutions are not merely staffed by imported talent, but increasingly run by local professionals, trained in global best practices but rooted in regional context.

However, challenges remain. The UAE’s education system still contends with the residual effects of colonial curricula and a historical underinvestment in the humanities. Critical thinking, often essential to contemporary art, is not uniformly emphasized across all schools. Moreover, for many families, careers in the arts are still seen as financially precarious compared to medicine, law, or engineering. As such, part of the educational mission must also be cultural: reshaping societal perceptions of what it means to be an artist or a curator in today’s UAE.

That change is beginning to happen. Young Emiratis are increasingly enrolling in art schools, studying abroad in places like London, Paris, and New York, and returning to Abu Dhabi to launch studios, galleries, and creative agencies. The emergence of a supportive legal and economic framework, including copyright laws, freelance visas, and funding bodies, is slowly making the dream of a sustainable creative life more realistic.

Moreover, the creative economy is now measurable. According to DCT Abu Dhabi, creative industries account for a growing share of non-oil GDP and employment. As digital technologies open new frontiers—virtual reality, NFTs, AI-generated art—the city is positioning itself as a forward-looking platform where tradition meets innovation.

Abu Dhabi’s art education and creative economy are thus deeply intertwined. They represent not only a pipeline of talent but a redefinition of civic identity. By investing in artists as workers, learners, and storytellers, the emirate is building not just institutions, but futures.

Next, we’ll explore how this momentum plays out in the realm of Art Fairs, Biennials, and the Role of Commercial Galleries, where market dynamics, cultural policy, and artistic practice intersect in dynamic, sometimes contentious ways.

Art Fairs, Biennials, and the Role of Commercial Galleries

While museums and foundations often carry the cultural prestige of a city, it is the marketplaces and temporary exhibitions—art fairs, biennials, and galleries—that energize the daily pulse of an art scene. In Abu Dhabi, these platforms are not only vital engines of economic activity but also serve as cultural touchpoints: where collectors meet creators, where emerging voices gain exposure, and where the public engages with both the avant-garde and the accessible. Together, they form a dynamic ecosystem that links the emirate to regional and global art markets.

At the heart of this ecosystem is the Abu Dhabi Art Fair, launched in 2009 and held annually under the patronage of the Department of Culture and Tourism – Abu Dhabi. More than a commercial fair, Abu Dhabi Art functions as a hybrid space—equal parts marketplace, public exhibition, educational forum, and commissioning platform. It reflects the city’s broader ambition to make art not just a commodity, but a civic experience.

The fair typically brings together top-tier international galleries—such as Galleria Continua, Pace Gallery, and White Cube—with leading regional players from the UAE, Lebanon, Iran, and North Africa. But what makes Abu Dhabi Art distinctive is its structure. Unlike other fairs, it includes curated sections and artist commissions that exist beyond the white cube. Initiatives like “Beyond: Emerging Artists”, “Gateway”, and “Beyond: Artist Commissions” have become signature programs, placing contemporary works in public spaces, heritage sites, and even the desert dunes of Al Ain and Al Dhafra.

This spatial expansion is both aesthetic and political. By moving art beyond the confines of galleries, the fair aligns itself with Abu Dhabi’s ethos of accessibility and integration. It invites audiences who might never visit a museum to encounter large-scale installations, performances, and sculptures in open-air settings or cultural landmarks like Qasr Al Hosn. This approach reflects a broader regional trend toward public art as a form of soft diplomacy and nation-branding, but in Abu Dhabi, it often also serves pedagogical and community-building purposes.

At the commercial level, the fair is increasingly seen as a serious market platform, especially for Middle Eastern and South Asian collectors. Prices range from a few thousand dollars for early-career artists to multimillion-dollar blue-chip works, but there is also a strong emphasis on regional contemporary art. Galleries report solid institutional acquisitions from UAE-based museums, and private collectors—many of whom are new entrants to the art world—are growing more adventurous in their tastes.

Crucially, Abu Dhabi Art is not alone. It exists in dialogue with neighboring events like Art Dubai, Sharjah Biennial, and regional fairs in Jeddah, Doha, and Beirut. Together, these events create a circuit that both sustains and challenges artists. For many, Abu Dhabi Art offers the more scholarly and structured platform within this network—a place where curation is as important as commerce, and where the state’s involvement creates a measure of institutional security.

Commercial galleries in Abu Dhabi itself have historically been limited in number, especially compared to Dubai, but this is slowly changing. Spaces like Salwa Zeidan Gallery, Etihad Modern Art Gallery, and Aisha Alabbar Gallery (originally based in Dubai but participating in Abu Dhabi programs) provide crucial platforms for Emirati and regional artists. These galleries often act as talent incubators, helping artists navigate the complex terrain of pricing, production, and international exposure.

Many of these commercial galleries also work in tandem with state and quasi-state entities, a structure that is both unique and reflective of the UAE’s broader governance model. For example, artists who begin with a gallery often find opportunities for residencies or commissions through initiatives like Warehouse421, Manarat Al Saadiyat, or the Salama bint Hamdan Foundation. This semi-centralized ecosystem allows for continuity in career development, but also raises questions about independence, criticality, and the limits of state patronage.

The biennial model, though more associated with Sharjah, has begun to influence Abu Dhabi’s own cultural programming. Temporary exhibitions and festivals often take the form of mini-biennials, curated by international figures and emphasizing transnational themes. These events experiment with formats: from performance-based happenings to sound installations, from decolonial retrospectives to climate-themed group shows.

That said, the art market in Abu Dhabi still faces hurdles. There is limited infrastructure for secondary market sales, conservation services, and art law expertise. While acquisition budgets are healthy at major institutions, mid-tier collectors often lack the support systems found in more mature markets. Additionally, while there is growing openness to experimental art, censorship and self-censorship remain considerations, particularly around themes of politics, gender, and religion.

Nevertheless, the trajectory is promising. The state’s continued investment, paired with growing interest from private collectors and regional curators, has created a robust foundation. Artists can now envision career paths that involve gallery representation, public commissions, academic affiliations, and international residencies—all within a supportive but competitive environment.

The role of art fairs and commercial galleries in Abu Dhabi is thus twofold: they stimulate economic activity, but also shape cultural discourse. They are spaces where art is negotiated—between state and market, tradition and innovation, local and global.

In the next section—Public Art, Monuments, and Visual Identity—we will step outside the institutional and commercial spaces to explore how art exists in the everyday fabric of the city, and how public artworks contribute to shaping Abu Dhabi’s civic self-image.

Public Art, Monuments, and Visual Identity

In many global cities, public art is the most visible and accessible form of cultural expression. It doesn’t require a ticket or an invitation. It’s there for residents and tourists alike—part of the urban fabric, quietly shaping how people interact with their surroundings. In Abu Dhabi, public art plays a unique role. It is not only a tool of aesthetic enhancement but also one of statecraft, identity formation, and cultural storytelling.

The city’s evolution has been marked by an increasingly deliberate effort to infuse public space with artistic meaning. From large-scale sculptures along the Corniche to historical monuments embedded in urban parks, Abu Dhabi uses public art to fuse tradition with modernity, memory with innovation.

One of the earliest forms of public art in Abu Dhabi was, unsurprisingly, monumental architecture. The Qasr Al Hosn, once a defensive watchtower and royal palace, has been restored and reimagined as both a cultural site and a symbol of continuity. Nearby, the Founder’s Memorial—a monumental tribute to Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan—blends technology, landscape architecture, and sculpture in a particularly striking way. The memorial’s centerpiece, The Constellation, features a suspended three-dimensional portrait of Sheikh Zayed formed from hundreds of geometric shapes. Visible only from certain angles, it suggests the interplay of perception and legacy, public memory and personal mythology.

Unlike traditional statues or plaques, The Constellation reflects a modern approach to commemoration—interactive, abstract, and reflective. Visitors walk through gardens designed to echo the landscapes of the Emirates, while curated soundscapes and inscriptions narrate the founding values of the nation. This synthesis of art, architecture, and landscape represents a broader trend in Abu Dhabi’s public art: one that values symbolism, serenity, and the blending of natural and built environments.

Public sculpture is also becoming a more prominent feature in urban planning. Along the Corniche, in parks, roundabouts, and promenades, works by local and international artists are installed to interact with daily life. These range from minimalist geometric forms inspired by Islamic patterning to more literal representations of cultural heritage—such as falcons, dhow boats, or palm fronds rendered in bronze or stone.

In recent years, the government and cultural institutions have invested more directly in public art commissioning. The “Public Art Abu Dhabi” initiative, launched by the Department of Culture and Tourism – Abu Dhabi, aims to create an expansive, long-term framework for integrating public art into urban development. The program includes open calls to artists, residency-based commissions, and permanent installations across key neighborhoods, especially emerging districts like Al Reem Island and the new Cultural Quarter on Saadiyat.

One of the initiative’s most ambitious features is a plan for an urban sculpture trail, linking major cultural landmarks across the city through a curated sequence of public works. The idea is to create not just isolated installations, but an art walkable city—where each piece forms part of a larger narrative about heritage, innovation, and shared space.

These efforts are complemented by temporary public art events. For example, Abu Dhabi Art’s “Beyond” program annually places commissioned works in public spaces, sometimes far outside the city—in the Liwa Desert, in Al Ain Oasis, or among archaeological ruins in Al Dhafra. This approach not only decentralizes cultural access, but also invites viewers to reconsider the relationship between artwork and landscape, time and place.

Street art and murals, while less prevalent than in cities like Beirut or Cairo, have begun to emerge, especially in areas undergoing regeneration. Projects tied to community engagement, including youth-led murals and collaborations with international street artists, have appeared in schools, public libraries, and heritage districts. These efforts are cautiously expanding the vocabulary of public art in Abu Dhabi to include more informal, grassroots contributions.

Importantly, Abu Dhabi’s public art is rarely confrontational or overtly political. Instead, it tends to emphasize harmony, tradition, and collective values—consistent with the UAE’s broader narrative of unity and national pride. But within these boundaries, artists have found subtle ways to embed complexity. Works that explore the tension between past and future, the presence of the environment, or the abstraction of national symbols allow for layered interpretations.

Visual identity in Abu Dhabi also extends beyond sculpture. Urban design, signage, lighting, and landscape architecture are all approached with a keen aesthetic sense. Public buildings often incorporate mashrabiya screens, calligraphic motifs, and abstract geometric designs that echo Islamic principles of beauty and order. Even the city’s skyline, seen from across the water, is curated with architectural intent—a composition of domes, towers, and reflective surfaces.

And then there is the role of light. Abu Dhabi’s climate and geography have encouraged the use of light as an artistic material—both in natural and technological forms. Installations that use projection mapping, interactive LEDs, or solar-powered lighting have featured prominently in festivals like Mother of the Nation Festival and Abu Dhabi Festival, transforming public spaces into ephemeral galleries.

Ultimately, public art in Abu Dhabi is not just decoration. It is a strategy of civic engagement, soft diplomacy, and identity articulation. It helps residents feel rooted in place, invites visitors to contemplate the city’s values, and frames the skyline as more than real estate—it becomes a shared cultural statement.

In our next section—Regional Dialogues: Abu Dhabi and the Gulf Art Scene—we’ll widen the lens to examine how Abu Dhabi fits within the broader constellation of Gulf cities, and how cross-border collaborations, rivalries, and influences shape the cultural ecosystem of the region.

Regional Dialogues: Abu Dhabi and the Gulf Art Scene

Abu Dhabi does not exist in a cultural vacuum. Its artistic evolution, while distinct, is deeply embedded in the broader dynamics of the Gulf region, where cities like Sharjah, Dubai, Doha, Kuwait City, and Riyadh are all vying to shape the identity of contemporary Arab art. What emerges from this landscape is not only a sense of competition, but a rich web of dialogue, influence, and collaboration that has helped elevate the Gulf as one of the most dynamic cultural zones in the 21st century.

In this context, Abu Dhabi plays a specific role: the capital of a federation with vast financial resources and a more measured, long-term approach to cultural development. Where Dubai may emphasize spectacle and market connectivity, and Sharjah leans toward scholarship and curatorial experimentation, Abu Dhabi’s cultural profile is built on state-led institution building, global partnerships, and symbolic diplomacy. This positioning informs its regional relationships—sometimes as collaborator, sometimes as counterpoint.

The most important internal dialogue within the UAE has been with Sharjah. For decades, Sharjah has championed critical contemporary art through the Sharjah Biennial, founded in 1993, and the Sharjah Art Foundation, which supports residencies, exhibitions, and research. Its biennial is considered among the most thoughtful and politically engaged in the Middle East, often addressing themes like decolonization, displacement, and futurism. While Abu Dhabi’s cultural strategy leans toward universalism and nation-branding, Sharjah presents a more provocative, experimental ethos.

That difference has led to a kind of productive tension. Many Emirati artists participate in both cities’ ecosystems, benefiting from Abu Dhabi’s resources and Sharjah’s critical frameworks. Exhibitions in Abu Dhabi often follow showings in Sharjah, and vice versa. There is also increasing institutional overlap, as curators, educators, and cultural workers move between the two, creating bridges that are often informal but impactful.

The relationship with Dubai is more commercially inflected. Dubai’s galleries, art fairs (especially Art Dubai), and auction houses have created a regional market hub, drawing collectors, dealers, and institutions from around the world. Many of the galleries that participate in Abu Dhabi Art are based in Dubai, and artists often exhibit in both cities. Yet Abu Dhabi’s approach is more government-driven and museum-oriented, whereas Dubai thrives on the entrepreneurial energy of the private sector. Together, they form a complementary duo: Abu Dhabi as the seat of high culture and institutional prestige, Dubai as the marketplace of innovation and exposure.

Beyond the UAE, Qatar is perhaps Abu Dhabi’s closest peer in terms of cultural ambition. Doha’s Museum of Islamic Art, Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, and National Museum of Qatar represent an equally assertive effort to position itself as a global cultural hub. Like Abu Dhabi, Qatar has invested in international partnerships, architectural icons, and curatorial depth. The two emirates often engage in quiet rivalry, bidding for the same exhibitions or courting the same artists, but they also reflect a shared belief in culture as diplomacy.

In recent years, Saudi Arabia’s rapid cultural opening has introduced a new dynamic. With initiatives like the Diriyah Biennale, Desert X AlUla, and the Misk Art Institute, Riyadh and Jeddah are developing their own arts ecosystems at remarkable speed. Saudi’s scale, population, and new-found liberalization offer both opportunities and challenges for Abu Dhabi. On one hand, Emirati artists are increasingly invited to exhibit in Saudi Arabia, and curators from both countries are collaborating. On the other hand, Saudi’s sheer momentum may draw attention and talent away from the UAE, especially among Arab artists seeking new markets.

Yet Abu Dhabi retains several advantages. Its political stability, diplomatic neutrality, and institutional maturity make it an attractive hub for long-term cultural engagement. The Louvre Abu Dhabi, in particular, gives the emirate an edge in terms of global recognition. Its ongoing collaborations with European museums, international universities, and cross-border festivals position it as a cultural mediator in a fragmented region.

There is also a growing emphasis on pan-Gulf exhibitions and residencies. Initiatives such as the GCC Art Collective, Khaleeji Art Museum, and cultural diplomacy exchanges have begun to create a shared visual language rooted in Gulf experiences—urban transformation, desert ecology, labor migration, and the balancing act between tradition and modernity. These collective projects underscore the regional dimensions of identity that transcend national borders.

Of course, regional collaboration is not without friction. Differences in censorship laws, gender norms, political affiliations, and institutional freedom continue to shape what is possible in each location. But there is a palpable shift toward cross-border dialogue, especially among younger artists, curators, and scholars who see themselves as part of a Gulf generation rather than citizens of isolated city-states.

Abu Dhabi’s regional role, then, is both anchor and connector. It provides infrastructure, funding, and institutional legitimacy while increasingly opening itself to regional exchange. The future of its art scene may depend not only on global partnerships but on how well it listens, learns, and leads within its own neighborhood.

Next, we’ll turn to some of the more contested aspects of this cultural rise in the section “Challenges and Critiques: Labor, Authenticity, and Cultural Politics”, examining the tensions that underlie the city’s artistic ambitions.

Challenges and Critiques: Labor, Authenticity, and Cultural Politics

For all its architectural marvels, cultural investments, and curatorial innovation, Abu Dhabi’s art scene is not immune to criticism. In fact, the very scale and ambition of its cultural development have made it a lightning rod for debates around labor ethics, cultural authenticity, institutional independence, and representation. These critiques are not peripheral—they are central to understanding how art functions within the social and political fabric of the emirate.

The most persistent and high-profile concern has been labor rights, particularly in relation to the construction of Saadiyat Island’s flagship institutions. From as early as 2009, human rights organizations—including Human Rights Watch, Gulf Labor Coalition, and Amnesty International—began documenting exploitative labor conditions among migrant workers building sites such as the Louvre Abu Dhabi, Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, and Zayed National Museum.

The critiques focused on multiple issues: recruitment fees that left workers in debt, confiscation of passports, low wages, inadequate housing, and restrictions on freedom of movement and association. The fact that these abuses were occurring in the shadow of elite cultural institutions—whose stated missions included inclusivity, education, and human dignity—was seen as particularly galling. The contradiction gave rise to the term “museum-washing”: the use of art and culture to obscure or soften structural injustices.

These concerns were not ignored. International institutions such as the Louvre and Guggenheim were forced to reckon with the reputational risks. In response, TDIC (Tourism Development and Investment Company) and later the Department of Culture and Tourism – Abu Dhabi developed labor codes of conduct, implemented auditing systems, and worked with NGOs to improve conditions. In 2015, NYU Abu Dhabi, which had faced similar critiques, commissioned an independent report and promised reform.

While some improvements were made—particularly around housing and salary transparency—activists argue that accountability has been inconsistent. Many of the most outspoken voices within the Gulf Labor Coalition, including artists and academics, continue to boycott the Guggenheim project, citing delays in transparency and lingering exploitation. These tensions have sparked broader conversations about the ethics of cultural partnerships, especially between wealthy patrons and Western institutions.

The issue of authenticity also looms large. Critics often question whether Abu Dhabi’s cultural landscape is too top-down, overly reliant on imported expertise and global franchises, and not sufficiently grounded in local artistic ecosystems. Projects like the Louvre Abu Dhabi or the proposed Guggenheim are sometimes viewed as luxury branding exercises rather than genuine efforts at community engagement or artistic pluralism.