The year 1901 did not just mark the start of a new century—it brought with it a new idea of what an art gallery could be. In March of that year, amid the industrial sprawl and working-class neighborhoods of East London, the Whitechapel Art Gallery opened its doors. Unlike the palatial museums of the West End or the academic salons of the continent, Whitechapel Gallery was designed not to impress elites, but to serve them—at least in theory. It was the first publicly funded gallery in London dedicated exclusively to temporary exhibitions and, more importantly, to bringing fine art to audiences who had rarely seen it up close.

A Radical Architectural Gesture

The man responsible for the building’s unusual appearance was Charles Harrison Townsend, an architect whose work sat uneasily between Art Nouveau whimsy and medieval robustness. The façade he designed for Whitechapel Gallery remains one of the strangest and most beautiful on a London street: rounded archways, vegetal ornament carved into Portland stone, and a stylized tree of life above the entrance. There is no mistaking it for a classical building. Townsend’s style was idiosyncratic and unplaceable, and so was his vision of architecture: civic, symbolic, and modestly utopian.

Townsend had made a name for himself in the 1890s designing public libraries and museum buildings. His 1893 Bishopsgate Institute and 1897 Horniman Museum both emphasized educational accessibility and design fluency rather than grandeur. The Whitechapel commission, initiated in the late 1890s by social reformers and Quakers, shared that spirit. Rather than a temple to art, it was to be a kind of neighborhood university—a space where those shut out from Britain’s cultural elite could stand in front of a painting by Turner or Rossetti and feel, at least for a few hours, part of a larger world.

The First Exhibition: Modern Pictures for East End Eyes

When the gallery opened on 12 March 1901, it did so with a show titled Modern Pictures by Living Artists, Pre-Raphaelites and Older English Masters. It was an ambitious blend of the contemporary and the canonical, mixing works by established names such as Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and G. F. Watts with more current painters and illustrators. The goal was not just aesthetic exposure, but moral and intellectual elevation—a Victorian idea still strong even as the century turned.

The Whitechapel’s inaugural show was drawn largely from private collections and loans. There were no acquisitions, no house style. Instead, the gallery relied on temporary exhibitions and voluntary contributions. That first exhibition attracted thousands, many of whom had never set foot in an art gallery. Its organizers offered lectures, discussions, and printed programs to guide the uninitiated. Art was not simply something to be looked at, but to be talked about—and perhaps, in the reformers’ dreams, to be lived by.

Three features of that first show deserve notice:

- Its blend of periods: The Pre-Raphaelites, long dismissed by academic critics, were given pride of place alongside living artists. This implicitly positioned them as a living tradition, not a dead school.

- Its community role: Admission was free, lighting was electric (still rare), and the gallery remained open late to accommodate working-class visitors.

- Its didactic ambition: Art was displayed with explanatory material, a then-novel practice that helped bridge the gap between viewer and object.

A Gallery Without a Collection

Unlike the British Museum or the National Gallery, Whitechapel Gallery did not amass a permanent collection. Its purpose was not to enshrine cultural heritage but to circulate ideas, challenge tastes, and bring new currents to a wide public. It borrowed artworks from across the country, assembled thematic exhibitions, and often foregrounded what would now be called “curatorial perspective.”

This difference mattered. In an era when most art institutions were either elite collections or national museums rooted in empire, Whitechapel Gallery stood for something else: the provisional, the pedagogical, the plural. It was less a vault than a mirror—showing a different reflection with each season.

Art for the Masses or Moralizing for the Poor?

There is a temptation to romanticize the gallery’s founding mission as purely altruistic, a beacon of democratic enlightenment in the smog of Edwardian London. But this would miss the complexities of its social role. Many of those behind the gallery—Quaker philanthropists, municipal reformers, idealistic architects—saw art as a tool for social improvement, even discipline. A painting might uplift, but also instruct. Beauty was to make better citizens, not just delighted ones.

Still, whatever its intentions, the gallery’s effect was to expand the social terrain of British art. It drew in not only new audiences, but new kinds of artists and critics. Its later exhibitions—of Jewish art in the East End, of Indian painting, of avant-garde abstraction—would trace the growing fissures and pluralisms of 20th-century art. But in 1901, all of that was still to come.

A Precedent for the Future

The Whitechapel Gallery opened at a time when the map of the art world was shifting. The Salon system in Paris was losing ground to independent dealers and galleries. Artists were beginning to organize their own shows. Photography, printmaking, and design were challenging the supremacy of oil painting. And institutions—be they museums, academies, or galleries—were learning to navigate a new public that was broader, more mobile, and more skeptical than before.

In this context, Whitechapel was more than a provincial gesture. It was a prototype. Its influence would be felt in later civic galleries, community art centers, and eventually even in the ethos of major museums attempting to modernize their image.

A Tree of Life in Brick and Stone

Today, the gallery’s tree of life still crowns its façade—a symbol that Townsend never explained, but which seems fitting. Trees are slow to grow, quick to shelter. In 1901, the Whitechapel Gallery stood at the edge of both empire and modernity, offering something quietly radical: a belief that art should not only reflect the world but be available to it. The century it helped inaugurate would take that idea and twist it in every direction.

Its doors opened not with a revolution, but with a quiet invitation.

Chapter 2: Posthumous Recognition — Vincent van Gogh’s First Major Retrospective in Paris

In the spring of 1901, a strange, belated storm of color erupted in the heart of Paris. Inside the walls of Galerie Bernheim-Jeune—then a modest but growing dealer of modern art—hung 71 paintings by a man who had died eleven years earlier, largely unrecognized, in a rural asylum. It was the first major retrospective of Vincent van Gogh’s work in the French capital, and it would alter the trajectory of modern art.

The exhibition opened on 15 March 1901, though some sources place the first day slightly later. What’s clear is that for two intense weeks, the Parisian art public encountered something they had not quite seen before: paintings that pulsed with personal urgency, emotional immediacy, and a palette that seemed to break with nature itself. Van Gogh had been gone since 1890. But in March 1901, his work arrived fully alive.

The Dealers, the Widow, and the Vision

The show was organized by the Bernheim-Jeune brothers—Gaston and Josse—two rising figures in the Parisian dealer world, known for promoting living artists and taking commercial risks. They did not act alone. Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, Vincent’s sister-in-law and the widow of his brother Theo, had spent the previous decade carefully preserving, cataloguing, and promoting van Gogh’s legacy. Without her unshakable belief in the value of his work, the retrospective might never have happened. Julien Leclercq, a critic and early champion of van Gogh, was also instrumental in shaping the exhibition’s reception.

This was not a state-sponsored homage. It was a commercial gamble—a bet that the public was finally ready. In this sense, it marked a shift not only in van Gogh’s legacy, but in how modern artists could be rehabilitated. A dead man, previously derided or ignored, could be reborn through the agency of private networks, critical advocacy, and well-timed exhibition.

A Room Like No Other

Visitors who entered the gallery that March encountered a barrage of intensity. The 71 paintings selected for the exhibition did not flinch from the artist’s darker moments. There were fields in the grip of wind, sunflowers that seemed to burn from within, a bedroom of alarming simplicity, and portraits whose eyes refused to rest. The cumulative effect was disorienting.

To the Parisian public, the most startling aspect was not simply the subject matter, but the formal language. Van Gogh’s brushwork often seemed uncontrolled, his colors implausible. In Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear (not definitively listed in the show but known to have circulated during the period), the green of the wall clashes against the red of a Japanese print. In The Night Café, the air itself seems sick. He painted feelings, not surfaces. In a city that had only recently absorbed Impressionism, van Gogh felt like a rupture.

Yet not all reactions were skeptical. Several younger painters—Henri Matisse among them—left the exhibition shaken. For those still experimenting with new ways to depict the world, van Gogh’s disregard for decorum was liberating. He had not painted to please, and this made him dangerous in the most useful way.

The Seeds of Modernism

If the 1901 retrospective did not instantly canonize van Gogh, it sowed the seeds for what came next. Within a few years, his influence would register in the bold color of the Fauves, the introspection of early Expressionism, and the spiritual aspirations of artists like Kandinsky. Van Gogh’s example helped detach painting from mere representation and reattach it to personal necessity.

Three outcomes from the 1901 show are especially telling:

- Commercial legitimacy: Works that had struggled to find buyers in the 1880s now entered collections, some purchased directly from the gallery.

- Critical engagement: Writers began to link van Gogh with the tragic genius archetype—misunderstood, tormented, but ultimately visionary.

- Stylistic reverberation: Artists across Europe took note of van Gogh’s palette, emotional weight, and liberation from conventional harmony.

In short, van Gogh was no longer a curiosity or a cautionary tale. He had become a precedent.

Memory and Myth

The exhibition also solidified a mythology that had already begun to form around van Gogh: the isolated genius, the mad Dutchman with a severed ear, the saint of suffering. This narrative, which would only grow in the decades to follow, began to crystallize in 1901. It was shaped not just by his art, but by letters, anecdotes, and the sheer emotional intensity that surrounded his reputation. In death, van Gogh became the patron saint of artistic sincerity.

But there was something more quietly revolutionary at work. The 1901 retrospective offered proof that the artistic present no longer monopolized artistic meaning. A body of work could emerge belatedly and still shape the future. In this sense, van Gogh’s posthumous debut was not just a recovery; it was a signal that art history had changed course. Linear progress gave way to rediscovery, to the retroactive valorization of genius, to the idea that the avant-garde could arrive too soon and still matter later.

A Late Arrival, A Timely Impact

The irony, of course, is that van Gogh had lived in Paris, had worked feverishly there in the mid-1880s, and had died largely unheralded. His colors were too wild, his technique too raw, his temperament too unstable. By the time Paris finally embraced him, he was long gone. But perhaps that distance made it easier. Van Gogh no longer had to be tolerated—only interpreted, admired, and mourned.

The 1901 retrospective was not the end of that story. It was the beginning of van Gogh’s second life—one in which his paintings would travel farther than he ever had, hang in places he never entered, and speak to generations that had not been born when he died in Auvers-sur-Oise.

It is rare for a single exhibition to change the tone of an entire century. But this one did. Quietly, irrevocably, it rewrote the terms by which modern art would be judged: not by polish or pedigree, but by urgency, truth, and the refusal to retreat from pain.

Chapter 3: A Debut That Changed Everything — Pablo Picasso Moves to Paris and His First Exhibition

In June 1901, a young Spaniard barely out of adolescence mounted his first solo exhibition in Paris. The gallery was modest, the paintings urgent, and the name on the wall — Pablo Picasso — still unknown to most. Yet something shifted that summer on the Rue Laffitte. What began as a promising debut became the ignition point for one of the most influential careers in modern art.

A Nineteen-Year-Old in a City of Giants

Picasso had already visited Paris in 1900, drifting between ateliers, cabarets, and studio flats, absorbing the pulse of a city still basking in the afterglow of the 1889 Exposition and adjusting to the new realities of the fin de siècle. But his true arrival came in 1901, when he returned to the French capital with intention — and with backing.

The opportunity came through his Spanish circle. His friend and fellow artist Francisco Iturrino, already known to the Parisian avant-garde, helped broker Picasso’s exhibition at Galerie Ambroise Vollard, one of the few dealers in the city willing to take a chance on young and unknown talent. Vollard, who had previously shown Cézanne, Gauguin, and Van Gogh, was no stranger to the risk of radical work. He offered Picasso and Iturrino a joint exhibition in June, placing them before a sophisticated but skeptical audience.

Picasso was just nineteen years old. But he moved quickly. Faced with the task of filling a room with dozens of works, he painted with relentless speed and improvisation, often on cardboard when canvas was out of reach. In a matter of weeks, he produced a torrent of portraits, café scenes, dancers, absinthe drinkers, and allegories. His palette was bright, his lines confident, his influences evident — Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec, Van Gogh. Nothing about the work was cautious.

Inside the Galerie Vollard

The exhibition opened on June 24. Reviews were mixed but watchful. Some critics praised the young Spaniard’s energy, comparing him to Goya; others noted the weight of his influences and cautioned that such precocity might burn out. But the response was not cold. Works sold. Collectors took note. And more importantly, the experience seemed to jolt something inside the artist himself.

The show marked a threshold. For the first time, Picasso stood not as a student of art but as a competitor within it. He was no longer just imitating the masters — he was challenging their territory. In the months that followed, his work darkened. The colors cooled. Figures grew more isolated. A new gravity emerged.

This transition is now known as the beginning of his Blue Period — a stretch of years defined by melancholic hues and introspective themes. Its seeds were already visible in the summer of 1901. In paintings like Seated Harlequin and Woman in Blue, there is a tonal shift: stillness, detachment, the suggestion of inner sorrow. It was as if the commercial success of the show freed him to move inward.

The Crisis of Imitation and the Question of Style

For all its acclaim, the Vollard exhibition confronted Picasso with a problem that haunts many prodigies: the crisis of influence. He had mastered the vocabulary of others — the lines of Lautrec, the palette of Van Gogh, the staging of Degas — but had not yet forged his own idiom. The critics noticed. And Picasso, acutely self-aware, did too.

Rather than retreat, he veered into severity. His later works that year began to reject the carnival of Montmartre in favor of solitude. Gone were the dancers and the decorative decadence. In their place came solitary figures — blind beggars, sad clowns, desolate mothers — rendered in heavy blues and greens, with brushwork that slowed and thickened. This was not stylistic refinement. It was existential recalibration.

Yet even in this transition, traces of the exhibition remained. Picasso’s early portraits retained their spontaneity. His urban scenes, though less frenetic, still bore the imprint of those first feverish weeks in Paris. The Vollard show may have launched his name, but it also marked a farewell to pastiche.

A New Kind of Debut

What made the 1901 exhibition significant was not just that it introduced Picasso to the Paris art world. It also showed a new path for modern artists more broadly. In an era still dominated by academic salons and institutional hierarchies, Picasso’s debut happened through a private dealer, on commercial terms, in a gallery that valued novelty over pedigree. This foreshadowed the structure that would define the 20th-century art world: artists discovered by dealers, not academies; fame built through small shows, not state recognition.

The show also hinted at a cultural shift. Here was a young artist not simply trained in tradition, but exploding out of it — absorbing, discarding, transforming. The very speed with which he moved through styles in 1901 made clear that modernism would not be a single aesthetic but a velocity, a restlessness, a refusal to settle.

From Promising to Singular

By the end of that year, Picasso had already left behind much of what filled the walls of Galerie Vollard. What had begun as a dazzling, derivative display of talent had become something deeper: a reckoning with grief, loss, and identity. The death of his friend Carlos Casagemas, who had shot himself in Paris in February, haunted him. It may well have driven the introspection that followed. The Blue Period, in many ways, began not just with a change in palette, but with a suicide and a debut.

Yet Picasso never returned to the sentimentalism that often plagued artists working in similar emotional registers. Even at his most melancholic, he remained composed. The 1901 show, with its energetic display of influences, gave way to something leaner and more deliberate. What emerged by year’s end was not the promise of greatness — it was the beginning of it.

The artist who had arrived in Paris as a teenager was now something else: a name, a presence, a force. And Paris, which had seen many young painters come and go, had recognized one it would not forget.

Chapter 4: Painting, Movement, and Labels — Early Use of “Expressionisme” and Beyond

In the long history of art, labels often come late. Movements are rarely named at their birth, and artists seldom agree on what their work should be called. But in 1901, something unusual happened: a word appeared in the title of a Paris exhibition that hinted at a new aesthetic force. The word was “Expressionismes.” The artist was Julien-Auguste Hervé. And while few noticed it at the time, the term would soon ignite a continental debate about the future of painting.

The Unnoticed Spark

Hervé’s exhibition in 1901, held in Paris under the banner Expressionismes, did not make headlines. Hervé himself was not a major figure in the avant-garde — more an experimenter than a leader — and his works leaned toward dreamlike landscapes and moody allegories, steeped in a personal vision of symbolic interiority. Yet the title of the show stood out. In an era when most painters were still labeled by schools — Impressionist, Symbolist, Post-Impressionist — “Expressionism” suggested a new priority: the intensification of inner experience.

The idea was in the air. Around the same time in Germany and Austria, artists were beginning to move away from naturalistic description toward distortion, exaggeration, and emotional confrontation. The word “Expressionism” would not take firm root until a few years later — particularly with the rise of Die Brücke in Dresden (founded 1905) and Der Blaue Reiter in Munich (1911). But Hervé’s 1901 gesture was prophetic. It placed the emphasis not on what the eye sees, but on what the soul insists upon.

The Rebellion Against Surface

By 1901, the art world was already fatigued by the perfection of appearances. Impressionism, for all its brilliance, had codified a way of seeing: dappled light, fleeting moments, luminous surfaces. Symbolism had offered an escape route — into dreams, myths, and metaphysical suggestion — but even that was beginning to harden into mannerism.

What artists like Hervé — and later, more forcefully, the German Expressionists — proposed was a different commitment altogether: to render not the visible world, but the felt one. Color became a weapon, line a scream, form a site of struggle. The self was no longer just behind the brush; it was in the paint itself.

Three currents helped fuel this new impulse:

- The psychological revolution: With Freud’s early writings circulating in Vienna and beyond, the notion of a divided, haunted self was gaining cultural traction.

- The disillusionment with progress: The new century arrived not just with optimism, but with unease. Industrialization, urban crowding, and political tensions created a growing sense of alienation.

- The example of van Gogh and Munch: Though not yet institutionalized as Expressionists, these painters had shown that the depiction of inner turmoil could be more powerful than fidelity to the world.

In this context, the term “Expressionismes” did not signal a school — it signaled a crisis.

A Name for Restlessness

Hervé’s use of the word was not ideological. There was no manifesto, no group identity, no clear program. But the title opened a linguistic door. Within a decade, “Expressionism” would become a term of contention, adopted by some, rejected by others, but always charged with intensity.

It became associated with artists who sought not to depict life but to confront it. Max Beckmann, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Egon Schiele, Käthe Kollwitz — each would channel personal and collective trauma through distortion, confrontation, and urgency. Expressionism became synonymous with moral seriousness and formal audacity. And it owed some of its earliest formulation to the quiet shock of Hervé’s 1901 exhibition.

What’s remarkable is that Hervé himself was not particularly radical in technique. His works drew on Symbolist motifs — mists, horizons, blurred light — and bore more resemblance to Puvis de Chavannes than to the later ferocity of German painting. But that discrepancy itself is telling. “Expressionism” in 1901 was still an undefined space — a field of possibility rather than a style.

The Anxiety of Naming

The early 20th century was awash in new names. Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism — each sought to carve out its distinction, often in opposition to something else. But “Expressionism” was different. It was less a technique than a stance. It implied that art should not reflect the world but reshape it according to inner necessity.

This made it slippery, and sometimes contentious. Critics complained that it invited formlessness, subjectivity without discipline. Some artists embraced it with caution, wary of being grouped into a school they did not recognize. But the term stuck. And it grew, absorbing not only painting but literature, theatre, and film.

In retrospect, Hervé’s modest show in 1901 did not launch Expressionism. But it gave the movement one of its earliest public names. And in naming, it foreshadowed the direction in which much of modern art would travel — away from mimesis, toward vision; away from surface, toward substance.

A Language Still in Formation

Looking back, it is tempting to see the year 1901 as a calm before the storm — a moment when the old forms still held, but the new energies were gathering. The fact that the word “Expressionismes” appeared in a Paris exhibition that year is more than a curiosity. It is an index of instability, a symptom of change.

Labels in art often follow the work. But sometimes, as in this case, a label arrives early — misunderstood, misapplied, but accurate in its intuition. Hervé’s exhibition marked no rupture, but it traced the fault line.

In a century soon to be defined by dislocation, conflict, and reinvention, “Expressionism” would become not just a style, but a necessity.

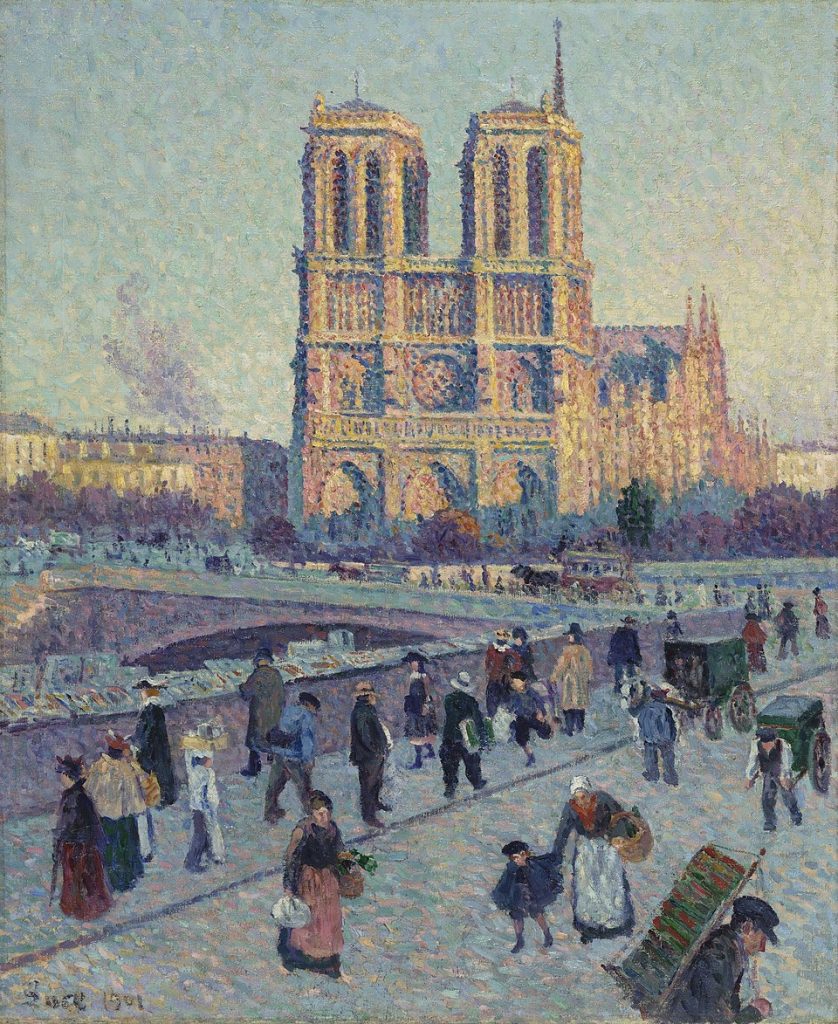

Chapter 5: Global Ripples — 1901 Beyond Paris and London

In the most canonical tellings of art history, 1901 is a year dominated by Parisian retrospectives and the emergence of Picasso. Yet far beyond the Seine and the London salons, the world of art was shifting in quieter but equally consequential ways. New buildings, new institutions, and new forms of mobility were altering how art was shown, who could make it, and where it might travel. This chapter turns to those less-remarked scenes—to Kraków, to transatlantic crossings, to the peripheries of the so-called art capitals—where 1901 marked beginnings of its own.

The Palace of Art in Kraków: A Portal into Young Poland

On 11 May 1901, the Kraków Society of Friends of Fine Arts (Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Sztuk Pięknych, or TPSP) opened the doors of its new headquarters: the Palace of Art. This was not just a new gallery building. It was a physical statement of Kraków’s modern cultural ambitions. Designed in the Art Nouveau style and modeled partly on the Vienna Secession, the building stood as a symbol of independence—both aesthetic and political.

Kraków, then under Austro-Hungarian rule, had long harbored artistic aspirations that lay outside the influence of Western Europe’s established academies. The Palace of Art represented a pivot from borrowed authority to regional identity. It provided a home for the “Sztuka” group—an association of Polish artists founded in 1897—and gave shape to the broader “Young Poland” movement, a flowering of modernist literature, music, and visual art that combined national revivalism with European experimentation.

The exhibitions held at the Palace soon included works by leading Polish painters such as Jacek Malczewski, Stanisław Wyspiański, and Józef Mehoffer—artists whose approach to symbolism, myth, and design positioned Polish modernism as an independent force. Their work fused decorative stylization with psychological depth, asserting that art from “the margins” could articulate its own metaphysical concerns, no less potent than those of Paris or Munich.

But the Palace also had a broader implication. Its very construction signaled that serious art institutions no longer needed to emerge from imperial centers. A city like Kraków, steeped in local history but distant from the power networks of Paris or Berlin, could become a crucible of innovation. The geography of cultural prestige was beginning to shift.

Across Oceans, In Search of Place: Carl Oscar Borg and the Migrant Artist

That same year, a very different journey took place. Carl Oscar Borg, a young Swedish artist just twenty-two years old, arrived in the United States. He came not with invitations or capital, but as a stowaway. His passage, like that of so many European migrants at the turn of the century, was clandestine, improvised, and fueled by a belief that a different kind of life—and perhaps a different kind of art—awaited in America.

Borg eventually settled in California, where he became known for his panoramic depictions of the American West. But in 1901, he was simply another migrant in a new land, a painter with training but no name. His path would soon intersect with U.S. patrons, notably Phoebe Hearst, and by the 1920s he would be part of the emerging aesthetic vocabulary of the Southwest—painting landscapes, Native American subjects, and desert iconography with a fusion of European technique and American subject matter.

Borg’s 1901 arrival is not a singular event, but an emblem. The beginning of the 20th century saw artists moving across borders not just to study or exhibit, but to start over. Migration—voluntary or forced—became a condition of modern artistic life. Whether fleeing war, poverty, or artistic stagnation, painters, sculptors, and designers began to work in increasingly transnational modes. New York, San Francisco, São Paulo, and Buenos Aires were no longer peripheral. They were becoming laboratories of aesthetic possibility.

Three consequences of this global movement began to emerge:

- Hybrid styles: Artists absorbed multiple traditions, combining academic technique with vernacular or indigenous subjects.

- New patrons and markets: Wealthy collectors in America and elsewhere offered financial support that European salons no longer guaranteed.

- Dispersed modernities: The idea that innovation only occurred in Europe began to erode. Artistic centers multiplied.

In this sense, 1901 anticipates the shape of the century to come: not a single axis of influence, but a network of intersecting trajectories.

The Unseen Groundwork of Global Modernism

While Kraków opened its Art Nouveau palace and Borg stepped ashore in a new country, other shifts—less documented but equally consequential—were also underway. In cities across Asia, Africa, and Latin America, artists were beginning to grapple with modernity on their own terms. In Japan, the yōga style—Western-style oil painting—was entering a new phase, fusing academic realism with Japanese subject matter. In Argentina, young painters were traveling to Europe and returning with experimental techniques, contributing to the formation of new artistic societies.

Though these developments would not coalesce until later, 1901 marked a year in which their conditions began to mature. Telegraph cables and shipping routes, the rise of print media and illustrated journals, and the increasing circulation of exhibitions and reproductions all contributed to a quiet broadening of the art world’s horizon. Artists no longer painted solely for a local audience. They painted into a global silence—hoping, sometimes, to be heard elsewhere.

The systems that would later define international modernism—biennials, dealer networks, foundation support—were not yet in place. But their outlines could be glimpsed in these early acts of movement, construction, and ambition. A gallery in Kraków. A Swedish stowaway in San Francisco. Paintings crossing oceans in crates or printed in lithographic magazines. The modern art world was starting to drift free of its anchor points.

Beyond the Capitals

In 1901, the gravity of Paris remained strong. But it was no longer absolute. Other cities, other paths, and other stories were beginning to assert themselves. The belief that artistic excellence could only emerge in a handful of cultural metropoles was quietly eroding.

And yet these shifts did not take the form of rupture. They emerged through institutions built with care, through journeys taken without fanfare, through exhibitions held in quiet halls far from the Parisian press. The ripple effect of modernism did not begin with manifestos. It began with buildings, migrations, and a restless hunger for new ways of seeing.

Chapter 6: Key Works Dated to 1901 — Early Modernist Signals on Canvas

The year 1901 did not yet have a style to call its own. It hovered between epochs: the final breath of Symbolism, the early murmurs of Expressionism, the shadow of Impressionism still visible across much of Europe. And yet, scattered across the studios of young painters and the salons of persistent radicals, several paintings from that year now appear in retrospect as signs of what was coming. They carried no manifesto. But they altered the texture of painting — in color, in mood, in subject — and introduced a new vocabulary of solitude, theatricality, eroticism, and sorrow.

Picasso’s 1901: The First Personal Mythology

Of all the painters working in 1901, none left behind as many date-marked statements of intention as Pablo Picasso. In the wake of his first Paris exhibition at Galerie Vollard, his productivity became feverish. Several major works from that year not only mark the launch of his Blue Period, but also reveal how quickly his artistic instincts eclipsed mere mimicry.

Seated Harlequin, painted in 1901, is often read as a self-portrait in disguise. The figure, dressed in the diamond-patterned costume of a commedia dell’arte clown, sits not in performance but in stillness. His gaze does not meet the viewer’s. His arms fold inward, not outward. In place of spectacle, we see containment. This reversal of the theatrical — from the outwardly comic to the inwardly mournful — would become central to Picasso’s work in the following years.

Another painting, Child with a Dove, presents a softened melancholy. The child stands in profile, cradling a white dove, the background washed in flat, pale blues and greens. There is no symbolic scaffolding, no narrative explanation. Just a mood — protective, precarious, almost religious. It is a portrait of emotional ambiguity that anticipates the inward turn of early 20th-century painting.

One of Picasso’s more enigmatic works from this year, La Gommeuse, straddles the line between social commentary and decadent satire. The sitter, a cabaret performer, appears both languid and confrontational. The garish backdrop and hollow eyes suggest neither judgment nor empathy, only estrangement. And beneath the surface — literally — another painting was later discovered, hidden on the reverse of the canvas: a mocking portrait of Picasso’s friend Pere Mañach, in drag. The picture within the picture signals not only the artist’s humor, but his skepticism about identity, performance, and respectability.

Then there is The Blue Room. A woman bathes in a cramped interior, her body bent and nearly consumed by the space around her. The colors are uniformly cool. This is not a nude of celebration or seduction, but of enclosure. Painted in the latter half of 1901, The Blue Room marks the threshold of Picasso’s Blue Period — a moment when his canvases became vessels for grief, loneliness, and the fragility of the human form.

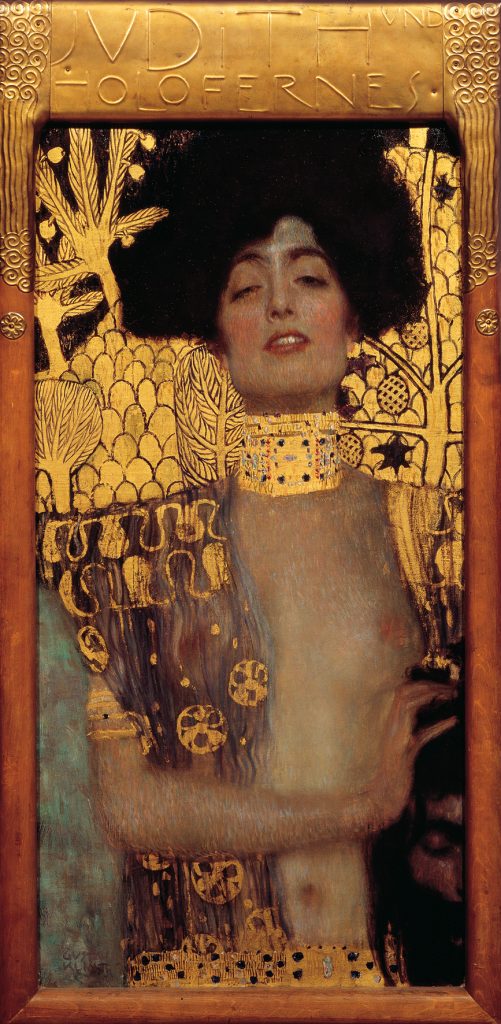

Klimt’s Judith: Decadence Meets Violence

Far from Montmartre, in the cultural ferment of Vienna, Gustav Klimt completed one of his most iconic and unsettling paintings in 1901: Judith and the Head of Holofernes. The work stunned viewers with its erotic charge and compositional daring. Judith does not look away in horror from her violent act, as in countless earlier versions of the subject. Instead, she looks directly outward, half-lidded and almost defiant, the severed head of Holofernes barely visible at the canvas’s edge.

The painting refuses moral clarity. Judith’s body is sensuous and adorned, but her expression remains unreadable. She is neither sinner nor saint, neither seductress nor victim. Klimt’s gold filigree and ornamental patterns draw from Byzantine mosaics, but the psychological charge is unmistakably modern. This is not narrative painting. It is psychological drama disguised as biblical allegory.

In the context of Vienna’s bourgeois culture, Judith was scandalous. But it also captured the paradox at the heart of modernist eroticism: beauty that repels, violence that seduces, form that overwhelms meaning.

Signals Without a Style

What connects these works is not a unified aesthetic, but a shift in artistic function. Painting in 1901 began to release itself from the obligation to depict or even to interpret. It began, instead, to suggest. The viewer was no longer offered a clear story, but a tone, an atmosphere, a residue of emotion.

Three shared qualities mark many of the year’s key paintings:

- Compressed space: Figures are often trapped in rooms, framed tightly, denying the viewer spatial escape.

- Subdued or unnatural color: Whether Klimt’s gilded eroticism or Picasso’s early blues, these works abandon naturalism for emotional impact.

- Ambiguous gaze: Subjects often confront the viewer obliquely — not to reveal themselves, but to resist interpretation.

In each case, the modern subject becomes a problem rather than a presence. There is no clear morality, no confident narrative. What remains is affect: silent, potent, unresolved.

Painting as a Site of Psychic Instability

By the end of the 19th century, the authority of the visible world had collapsed in painting. Artists no longer trusted appearance as a source of meaning. What emerged in 1901 was not yet abstraction, but a kind of visual doubt — a tremor beneath the surface. Faces turned inward, bodies slouched or blurred, and the old symbols refused to stabilize.

Picasso’s Blue Period would deepen this current, drawing from personal grief but channeling it through a visual language that resonated far beyond biography. Klimt, in turn, transformed the decorative into the psychological. Together, their works in 1901 signaled that painting was no longer merely a reflection of the world, but a mirror of the artist’s inner turbulence.

These were not finished statements. They were tests, flashes, half-formed arguments. But they mattered. They proved that modernism would not be announced with a single movement or style, but would instead leak into the edges of the canvas — not with triumph, but with disquiet.

Chapter 7: Births and Deaths — Generational Turnover in the Art World

The year 1901 was not merely a hinge between centuries. It marked a moment of generational handoff — a shift from the artists who had defined the late 19th century to those who would, often unknowingly, shape the 20th. Some of the most luminous figures of the preceding decades died that year, their reputations sealed or in decline. At the same time, a new cohort of artists was born, many of whom would reach maturity in the years between two world wars and create the formal revolutions that would define modernism. The year was not symbolic. It was literal. The human infrastructure of art was changing.

The Death of Lautrec — and the Disappearance of the Belle Époque’s Chronicler

On 9 September 1901, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec died in relative obscurity at the age of thirty-six. His death, at a family estate in Malromé, was the result of a long decline accelerated by alcohol, illness, and isolation. Yet even in his final years, he had continued to draw, to paint, to observe — as if desperate to salvage the world of Montmartre before it vanished under electric light and bourgeois respectability.

Toulouse-Lautrec had been the visual chronicler of fin-de-siècle Paris: its dancers, prostitutes, drinkers, performers, and misfits. His posters redefined graphic design. His lithographs captured movement and desire with unsparing line. But by 1901, the world he depicted was already receding. Montmartre’s anarchic energy was being tamed. The Moulin Rouge, once a site of debauchery, had become a tourist attraction. The ragged bohemia of the 1890s was turning into a marketable past.

Lautrec’s death symbolized more than personal tragedy. It marked the end of a certain sensibility — one in which decadence was both a pose and a protest. No one else could render a café-concert singer or a syphilitic brothel client with the same blend of empathy and detachment. He painted ugliness without pity, pleasure without romance. And when he died, that gaze was gone.

Final Acts and Quiet Departures

Toulouse-Lautrec was not alone. In early January 1901, August Friedrich Schenck — known for sentimental animal paintings in the Romantic tradition — also passed. His works, once cherished for their technical polish and anthropomorphic charm, had fallen out of critical favor. The moralism of his allegorical sheep and ravens now seemed naïve beside the psychological storms brewing in modernist painting.

On 4 January, Nikolaos Gyzis died in Munich. A key figure of the Munich School and one of Greece’s foremost 19th-century painters, Gyzis had balanced academic discipline with nationalistic allegory. His style was elevated, composed, heroic. But it was increasingly out of step with the fragmentation and introspection taking hold in Europe’s studios.

In March, the Polish painter Aleksander Gierymski died after years of declining health. A pioneer of realist painting in Poland, he had depicted the poor with solemnity and care, drawing comparisons to Courbet and early French naturalism. His passing was noted, but it was a different Poland emerging in 1901 — one defined by modernist symbolism, decorative stylization, and the quiet politics of aesthetic autonomy.

What united these deaths was not simply age or illness, but the waning of a world. The institutions, audiences, and aesthetic codes these artists worked within were crumbling or transforming. They had been raised in a world of salons, academies, and nationalist canvases. By the time they died, those very structures were beginning to erode.

The Births of 1901: Unknowing Inheritors

While these artists left the stage, others were just arriving — though no one could yet have known the roles they would play.

On 10 October 1901, in Borgonovo, Switzerland, Alberto Giacometti was born. He would become one of the defining sculptors of the postwar era, best known for his gaunt, elongated figures that seemed to dissolve into air. But in 1901, he was simply the son of a local painter, born into a mountainous village far from the art capitals of Europe.

That same summer, on 31 July, Jean Dubuffet was born in Le Havre, France. He would go on to reject the conventional art world altogether, coining the term Art Brut for the raw, outsider creativity he admired in psychiatric patients and street artists. His own paintings would challenge refinement, embrace chaos, and insist that high culture had grown stale.

On 13 January, Jaime Colson was born in the Dominican Republic. He would later become a key figure in Latin American modernism, bringing Cubist and Surrealist techniques into dialogue with Caribbean identity, myth, and colonial critique. For now, he was just another colonial child in a Spanish-speaking island, unaware of the roles he would play in reshaping visual language.

These three were not alone. 1901 also saw the births of:

- Alice Prin, better known as Kiki de Montparnasse, who would become a muse, model, and painter within the Parisian avant-garde.

- Beauford Delaney, an African-American modernist whose work, often marginalized during his lifetime, would later be recognized for its emotional depth and painterly invention.

- Norah McGuinness, an Irish modernist whose clean lines and color harmonies helped define mid-century design and book illustration.

- Richard Lindner, a German-born artist whose vivid, cartoonish figures would anticipate Pop Art decades later.

These artists shared little in geography, medium, or technique. But they had one thing in common: they were born into a world their predecessors had just departed, and they would not accept its terms.

Between Epochs, Between Selves

The contrast between the generation that died in 1901 and the one that was born is stark — but not entirely oppositional. Many of the young artists born that year would inherit not only the freedoms but also the traumas of those who came before. Giacometti’s existential figures echo Lautrec’s fatigue. Dubuffet’s iconoclasm builds on the rejection of academic sentiment. Delaney’s isolation mirrors the obscurity faced by painters like Gierymski, who never fully belonged.

What the year 1901 offers, then, is not a neat binary but a visible passage: from allegory to introspection, from nation to individual, from surface to fracture. The artistic world was shedding old skins — and not all at once. Deaths closed one era. Births began another. The hinge creaked open.

And standing at that hinge, unnoticed by most, were dozens of infants and dozens of corpses — futures unguessed, pasts just concluded.

Chapter 8: Institutions, Public Spaces, and the Changing Audience for Art

By 1901, the walls that separated art from the general public were beginning to erode—not symbolically, but physically, architecturally, and ideologically. New galleries opened their doors not just to showcase beauty or cultural pride, but to signal a changing relationship between artist, institution, and viewer. The modern art world was no longer confined to private salons or aristocratic collections. It was beginning to make its home in buildings meant for crowds, for students, for workers, for strangers.

This shift did not happen all at once, nor did it announce itself with any single manifesto. It unfolded quietly, in the construction of new gallery spaces, in the schedules of traveling exhibitions, and in the language of educational outreach. Art’s audience was changing. And in response, the institutions of art began to reinvent themselves.

The Gallery as Civic Architecture

The buildings themselves told part of the story. In cities like London, Kraków, and Vienna, galleries constructed around the turn of the century were shaped not only by stylistic ambitions—such as Art Nouveau or Neoclassicism—but by civic intent. These were not private halls walled off from urban life. They were designed to welcome the public, often with grand staircases, wide doors, and open hours designed to accommodate workers and families. Art was not just placed on display; it was staged as a common good.

The architecture of these institutions often echoed the twin ideals of progress and access. Ornamentation suggested refinement; spacious interiors invited contemplation. But behind the visual language was a deeper social project: the belief that art should elevate, inform, and perhaps even reform. Galleries became instruments of moral and aesthetic education, especially in industrial cities where leisure was newly available to some, and where the chaos of urban life required new forms of social coherence.

The idea was not simply to show paintings. It was to shape taste, to teach seeing, to provide contact with forms of culture that might otherwise remain inaccessible. And in that effort, galleries aligned themselves with schools, libraries, and museums as institutions of public enlightenment.

Temporary Exhibitions and the Culture of Circulation

A major innovation in this period was the rise of the temporary exhibition. Unlike permanent museum collections, which tended to ossify over time, temporary shows allowed for a more dynamic and responsive form of display. Artworks could travel. Themes could change. New artists could be introduced without requiring acquisition. The result was a livelier cultural calendar—and a more elastic sense of artistic relevance.

For audiences, this meant variety. A single gallery might offer an academic retrospective one month and a display of contemporary illustrators the next. The temporary exhibition also created a sense of occasion, encouraging repeat visits and cultivating a public that saw art not as a static inheritance but as an ongoing conversation. It was not enough to revere the past; one had to be alert to the present.

For artists, the implications were even more profound. Temporary exhibitions offered visibility outside of national academies or juried salons. They created the possibility of discovery. A young painter could, through the right curator or the right invitation, find their work on the walls of a public institution, within reach of critics and collectors. This mobility helped fuel the careers of emerging talents—and helped to decentralize artistic authority.

The Changing Audience: Class, Gender, and the Question of Inclusion

The transformation of galleries into public spaces also required a rethinking of who the public was. No longer composed solely of elite patrons or amateur connoisseurs, the new audience included workers, clerks, women, students, and foreign visitors. This demographic shift posed challenges, but also possibilities.

Some institutions responded with caution. They maintained decorum, restricted access, or attempted to educate the viewer into civility. Others embraced the change, offering evening hours, free admission, and printed guides designed for the uninitiated. Lectures, music performances, and community events often accompanied exhibitions, making the gallery not just a visual space but a cultural meeting ground.

But this inclusivity was uneven. The rhetoric of accessibility often masked continued exclusions—of working-class voices, of non-Western traditions, of women artists, of the avant-garde. Galleries might admit new audiences, but they did not always show new kinds of art. Still, the shift in audience composition planted the seed for future challenges to institutional norms. As more people encountered art, more began to question its boundaries, its hierarchies, and its silences.

Beyond Preservation: The Gallery as an Engine of Change

Perhaps the most important evolution of 1901’s institutions was their changing sense of mission. The gallery was no longer just a place to preserve or display. It became a space of interpretation, mediation, and influence. It shaped not only what people saw, but how they saw it.

This shift laid the groundwork for modern museology. The idea that exhibitions could tell stories, that curators had a voice, and that viewers brought their own perspectives—all of this would become central to the 20th-century gallery. In 1901, those ideas were embryonic, but present. Exhibitions began to explore thematic groupings, historical juxtapositions, and even ideological arguments. The gallery was learning how to speak—and how to listen.

The New Institutions and the Modern Eye

In the long arc of art history, 1901 was not the moment when the public gallery was invented. But it was a moment when the idea of the gallery shifted from stability to dynamism, from elite ritual to shared space. The institutions of that year—and the exhibitions they hosted—helped inaugurate a new kind of seeing: one shaped by social inclusion, by movement and change, and by the belief that art should be part of the life of the city, not apart from it.

It was an imperfect transformation, marked by contradictions. But it changed the terms of engagement between artist and audience. In doing so, it helped to shape the kind of world where modernism could take hold—not only on the canvas, but in the room.

Chapter 9: From Pain and Loss — Psychological Undercurrents in 1901 Art

Modern art did not begin with a bang, but with a shudder. Beneath the surface of many key works from 1901 lies a shared preoccupation: the solitary figure, the faded interior, the melancholic gaze. The paintings of this year may have varied in technique and locale, but many of them shared a tonal undercurrent — grief, introspection, psychological fragility. In this moment just past the turn of the century, artists were turning inward. Not for decoration. Not for ideology. But for something closer to a reckoning.

The idea that art should reflect emotional truth — not just social realism or academic beauty — had been developing for decades. But by 1901, this sensibility was no longer just thematic. It had become structural. It shaped color, composition, brushwork, and even the pace of execution. The great rupture of modernism would come later, but its pressure could already be felt: a slowing down of narrative, a thickening of silence, a growing sense that the human subject was no longer whole or at ease.

Grief as Style: The Death of Casagemas and the Blue Turn

Perhaps the most iconic example of art shaped by psychological disturbance in 1901 is the turn in Pablo Picasso’s work following the suicide of his friend Carlos Casagemas. Casagemas, a fellow Spaniard and poet, shot himself in a Paris café in February of that year — reportedly over an unrequited love, complicated by depression and declining health. Picasso, who was close to him, was deeply affected. In the months following the death, his painting changed in tone and intent.

The first results were public. La mort de Casagemas, completed mid-1901, is a rare visual elegy: the dead friend depicted with an almost religious stillness, candlelit and gently stylized. But more importantly, Casagemas became the trigger for what would soon be known as the Blue Period. The color palette shifted to muted, mournful hues. Subjects — often outsiders, beggars, the blind — became more isolated. Human figures lost weight, volume, clarity. Grief, in Picasso’s hands, did not simply become a theme. It became a form.

This was not, however, biographical indulgence. The personal loss catalyzed something broader: a recognition that modern painting could speak through mood rather than message, and that sorrow might be as visually powerful as spectacle.

Klimt’s Judith and the Psychosexual Divide

In Vienna, a very different kind of psychological tension emerged. Gustav Klimt’s Judith and the Head of Holofernes, completed in 1901, reads at first like a continuation of Symbolist painting — gold leaf, ornamental design, mythic subject. But beneath the surface, the painting is electrically unstable.

Judith’s eyes do not avert from the viewer. Her lips part not in shock or sanctity, but in a knowing, ambiguous expression. The head of Holofernes — decapitated, dimmed, cropped at the painting’s edge — is barely emphasized. What dominates is Judith herself, her pleasure, her refusal to behave according to moral scripts. The painting has been read alternately as a statement of female power, sexual cruelty, narcissism, or revenge. But what matters most is its refusal to resolve. The psychological weight is not in what Judith did. It is in how little we understand her.

Klimt’s work in 1901 signals a growing unease with narrative resolution. His women do not illustrate myths. They challenge them. And in doing so, they push the viewer into a new kind of psychological engagement — not with the story, but with its dissonance.

Internal Worlds and Silent Subjects

Other artists, though less documented in the canon, also worked through psychological themes in 1901. In the works of Edvard Munch, who was active but not exhibiting widely that year, the inner life continued to dominate the canvas. His earlier paintings such as The Voice and Melancholy were already establishing a visual vocabulary of emotional states — waves, curtains, spirals, bent bodies — that recurred throughout Symbolist and proto-Expressionist art around 1901.

What joins artists like Picasso, Klimt, and Munch — despite their differences in technique — is an orientation away from the exterior world and toward the fragile interior. Pain, loss, and sexual ambiguity became not subjects to be resolved, but zones to be entered.

Three tendencies characterize this shift:

- Abandonment of narrative climax: Many works depict not action but aftermath — not tragedy as event, but as residue.

- Compression of setting: Subjects are often painted indoors, alone, cut off from space, sometimes even from light.

- Emotion as distortion: In brushwork, color, and pose, emotional intensity begins to override realism or proportion.

This movement toward psychological complexity was not unique to 1901, but it became more explicit in that year. Artists no longer veiled emotion under allegory. They painted it directly — raw, unresolved, and in many cases, uncomfortably intimate.

The World Outside — and the Crisis Within

There is a temptation to link this psychological turn to the broader societal changes at the dawn of the 20th century: the rise of psychoanalysis, the breakdown of social hierarchies, the nervous anticipation of technological acceleration. And those links are real. Freud’s early work was gaining traction. Urbanization had transformed the pace of life. The spiritual certainties of the previous century were eroding. But what matters in the art of 1901 is not that it reflected these shifts, but that it registered them in form and feeling.

The modern self, as seen in these paintings, is no longer stable. It is fractured, burdened, spectral. The figure is there, but adrift. The brushstroke becomes a pulse. The color becomes a temperature. The face becomes a question.

In this way, the psychological undercurrent of 1901’s art anticipates the major artistic ruptures of the century to come. Before Cubism disassembled space, before Expressionism screamed in color, artists in 1901 were already suggesting that something had broken — not in society, but in the soul.

They did not yet have the language to name it. But they painted as if they felt it.

Chapter 10: Early Modernism and the Pre-Cubist Foreshadowing

In 1901, modernism had not yet declared itself. There were no manifestos, no radical ruptures in the public eye, no aesthetic shockwaves that could be pinned to a singular date. Yet the language of modern art was beginning to form in the mouths and hands of young artists—hesitantly, intuitively, almost unconsciously. The year offered little in the way of formal revolution, but much in the way of drift: a movement away from the illusionistic ideals of the past and toward something flatter, quieter, more abstract, and more inward.

When we look closely at 1901, we find a year crowded with early signals: a soft rejection of fixed perspective, a new interest in geometric compression, a loosening of form from function. Artists had not yet exploded the picture plane—but they had begun to tilt it. And in that tilt lies the beginning of modernism’s long and often conflicted vocabulary.

The Hidden Geometry of Cézanne

Paul Cézanne was still alive in 1901, working in the south of France, largely removed from Parisian currents but increasingly influential among the next generation. His brush was slow, methodical, and uninterested in the bravura gestures of the Romantics or the dreamworld of the Symbolists. Instead, Cézanne painted with a different kind of precision: not mimicking reality, but reconstructing it from first principles—planes, shapes, volumes.

The quiet revolution of Cézanne’s work lay in his refusal to treat the canvas as a transparent window. A table tilts toward the viewer. A skull sits not quite right. Brushstrokes are laid side by side like tesserae, building mass through accumulation rather than illusion. By 1901, younger artists had begun to absorb these lessons, even if the master himself remained a remote and somewhat marginal figure.

Picasso, only twenty and newly arrived in Paris, was one of those attentive apprentices. Though his 1901 works were steeped in expressive color and sentimental subject matter—many painted in response to the suicide of his friend Carlos Casagemas—he was already studying Cézanne. Not imitating, not yet transforming, but noticing: the structuring of space, the use of color as construction, the flattening of depth into something more formal.

The Paris Studio as Laboratory

The Paris art world of 1901 was a hybrid environment: part marketplace, part stage, part school. In the cramped studios of Montmartre and the emerging salons of Montparnasse, artists shared space, models, debts, meals, and ideas. These were not yet the years of avant-garde self-certainty. Instead, they were filled with tentative experiments, unfinished arguments, and the first outlines of future heresies.

In this context, the young painters who would become modernists—Picasso, Braque, Derain, Vlaminck—were still absorbing, still copying, still questioning. But their questions were becoming more pointed. What if volume was no longer the goal? What if color carried weight beyond representation? What if perspective was a convention, not a necessity? These were not yet public provocations. They were internal murmurs, exchanged between canvases and friends.

Even in works that appear conventional by later standards, these questions are detectable. In the early Blue Period paintings of Picasso, figures are elongated, isolated, abstracted by sorrow. In the landscapes of Derain, outlines begin to push against form. In Matisse’s early decorative experiments, pattern threatens to overwhelm space. The rules still hold—but they are strained.

Before the Break: Pre-Cubist Compression

Cubism, as it would later be defined, had not yet begun in 1901. There were no fractured still lifes, no simultaneous perspectives, no radical denial of Renaissance depth. But the ground was shifting. The compression of space, the emphasis on formal construction, the analytic eye—these were already in the air.

What would later become Cubism was not born in protest, but in an accumulation of visual logic. It was Cézanne’s apples sitting too close to the picture plane. It was the architectural solidity of African sculpture, which some artists were beginning to see in ethnographic museums. It was the simplification of line in Japanese prints. It was the realization, felt more than argued, that realism could no longer tell the whole truth.

By 1901, none of this had coalesced. But the inquiries had begun. Artists were asking not only how to depict the world—but whether depiction itself was sufficient. The painting was no longer a mirror. It was becoming a mind.

What the Critics Missed

What is striking about 1901, viewed from the future, is how little the art press noticed. Critics still debated academic technique, moral content, and painterly finish. The slow drift toward abstraction was mostly ignored or misunderstood. Cézanne was still treated with suspicion by the academy. Gauguin, who had died in 1903, was seen as a curious exoticist. Matisse had not yet shocked with color. Picasso was just another foreign talent.

This silence matters. It reminds us that the formation of a new artistic language is often invisible at first—dispersed, quiet, distributed across small decisions. In 1901, the art world still largely imagined itself through the frames of the 19th century. The century ahead was waiting in studio corners, on unsold canvases, in the hands of twenty-year-olds no one had yet learned to fear.

The Tilt Before the Break

The significance of 1901 lies not in what was finished, but in what was forming. Artists were not yet dismantling the picture, but they were testing its edges. They were asking what painting could do without narrative, without fidelity, without depth. In doing so, they began to think not of style as inheritance, but as experiment.

Modernism would not burst into the world fully formed. It would emerge through doubt, through hesitation, through the slow erosion of old certainties. In that sense, 1901 was a year of half-formed questions—many of which would shape the answers given by modernism in the years to come.

The revolution had not yet begun. But the ground was already unsteady.

Chapter 11: 1901 in Broader Cultural Context — Society, Technology, and Art’s Changing Place

Art does not unfold in isolation. It breathes the same air as politics, technology, religion, migration, and material life. In 1901, the painters and sculptors whose work hinted at new forms were not only reacting to their predecessors; they were living through a world in motion. Cities were expanding. Empires were tightening and fraying. Machines were accelerating. Belief was splintering. The arts, whether they acknowledged it or not, were being reshaped by the forces that governed ordinary life.

To understand 1901 in art, it is not enough to trace the brushstrokes or catalog the exhibitions. One must also stand in the crowd: in the café thick with cigarette smoke, in the public gallery at twilight, in the clattering street of an industrial city. This chapter steps into that world — the broader cultural and societal atmosphere — to consider how the very fabric of modern life was beginning to alter how artists saw, felt, and worked.

The New Urban Eye

By the first year of the new century, cities had become the dominant habitat of European and American life. Paris, London, Vienna, Berlin, and New York had all surpassed a million inhabitants. These were no longer simply capitals — they were engines of speed, alienation, energy, and modernity. To live in a city in 1901 was to be exposed to simultaneity: poverty and wealth, decay and construction, tradition and innovation in jarring proximity.

Artists responded in different ways. Some, like Toulouse-Lautrec in his final years, remained rooted in the nocturnal world of bars and cabarets, drawing out the pathos beneath the glamour. Others, like Picasso in his early Parisian period, turned toward the city’s unseen: the marginal, the sick, the invisible. The new city was not only a source of visual material. It was a psychological landscape — chaotic, intoxicating, overwhelming.

This shift in setting carried formal implications. The composition of paintings grew tighter, more compressed. Space flattened. Figures seemed dwarfed by architecture or by each other. Even landscapes, when they appeared, were no longer pastoral. They were broken by industry, cluttered by signs of human intrusion. The city remade not just content, but vision itself.

The Machine and the Mechanized Mind

1901 was also a year marked by technological confidence. Electricity was spreading through major cities. The internal combustion engine was reshaping transportation. The telephone, phonograph, and telegraph were all in use, shrinking distance and altering temporality. News traveled faster. Images circulated widely. A painting made in Munich could be reproduced in a Paris journal within days. An idea floated in Vienna could land in New York before the week’s end.

This acceleration changed artistic production in subtle ways. Artists became increasingly aware that they worked within a networked, image-saturated world. Photography, already decades old, had begun to influence not just portraiture but perception itself. Print culture demanded visual clarity, reproducibility, immediacy.

And yet there was also anxiety. Many artists, especially those associated with Symbolism or early Expressionism, recoiled from this mechanized world. Their work returned to myth, dream, or inner life — not as escapism, but as resistance. In Klimt’s Vienna or Redon’s France, the ornate and the mystical stood as aesthetic counterweights to the hard, metallic logic of modern progress.

Shifting Beliefs, Splintering Certainties

The end of the 19th century had not only shaken political structures; it had undermined religious and philosophical ones as well. Faith, once the primary interpreter of the world, was being eclipsed by science, psychology, and relativism. Nietzsche had pronounced God’s death a decade earlier. Freud’s theories were beginning to circulate. Anthropology, archaeology, and comparative religion introduced profound challenges to Christian universalism.

Artists in 1901 navigated this uncertainty in varied ways. Some sought new spiritual symbols, reworking classical or biblical imagery in modern idioms. Others abandoned transcendence altogether, embracing the human as frail, contingent, and alone. The decline of shared belief left a vacuum — one that would soon be filled by political ideologies, psychoanalytic theories, and radical aesthetics.

But in 1901, that vacuum was still open. The result was often art of ambiguity. Figures looked upward without clear object. Allegories floated unmoored from doctrine. The sacred and the profane blended in unsettling combinations. Klimt’s Judith, for instance, wields both religious narrative and erotic provocation, offering no resolution. It was not rebellion. It was a recognition that certainty was no longer possible.

The Expanding Public: Who Sees, Who Counts

Perhaps the most significant cultural shift in 1901 was not technological or aesthetic, but social: the expansion of the audience for art. Literacy had increased. Public education systems had matured. Women and working-class individuals were beginning to enter cultural life with new visibility and voice.

This change placed new demands on artists and institutions. What kind of art was suitable for a public gallery? Could abstraction communicate across class lines? Was beauty still a legitimate goal, or had it become suspect? The proliferation of public exhibitions — from Whitechapel to Kraków — reflected not just institutional ambition, but a social question: who gets to see?

Many artists were ambivalent. Some welcomed the democratization of taste. Others feared dilution, misreading, vulgarity. The tension between elitism and populism, between radical experimentation and public legibility, began to define the century’s artistic conflicts. In 1901, those battles were only beginning, but the ground was already shifting.

The Cultural Atmosphere Before the Storm

In retrospect, 1901 appears eerily poised. The decade to come would bring revolutions — in painting, politics, literature, and philosophy. Cubism, Expressionism, Futurism, and abstraction all lay ahead. So too did war, collapse, and cultural fragmentation. But in 1901, the surface still held. The machines ran. The galleries opened. The painters worked.

And yet the air was charged. Beneath the gold leaf and muted blues, beneath the stillness of portraits and the severity of café scenes, something else was forming — a sense that the old systems no longer explained the world, and that the new ones had yet to be born.

Artists in 1901 may not have known what was coming. But their work absorbed the tension. They painted it — not with slogans or manifestos, but with glances, shadows, spatial dislocations. They made images of the world not as it appeared, but as it was beginning to feel: unstable, accelerated, and uncertain.

Chapter 12: Why 1901 Matters — Looking Back from Today

At first glance, the year 1901 may seem unassuming — neither the birth of a self‑conscious movement nor the sudden arrival of an aesthetic earthquake. But when we step back and look decades later, it becomes clear that 1901 is not a footnote. It is a hinge. The year gathered together threads of what had been — academic realism, Symbolist mystery, decorative elegance — and let slip the first tremors of what would become modern art’s vast, multifaceted terrain. What we call modernism, with its dislocations, experiments, and ruptures, needed time to unfold; 1901 laid the ground.

A Threshold Rather Than a Revolution

The art of 1901 lacks the dramatic breakpoints of later years. There is no manifesto inscribed onto gallery walls, no founding “–ism” that declares itself the future. Instead, 1901 offers us something subtler: a layering of transformations. The infrastructures of art — galleries, dealers, public exhibitions — began to shift. The psychology of painting — inwardness, melancholy, estrangement — deepened. The identities of audience and artist started to blur. And even those who would become central to modernism were still young, unformed, testing their vision.

Art historians often treat movements as neatly defined periods: Realism, Impressionism, Symbolism, then Modernism. Yet any attempt to draw rigid boundaries misreads the reality of artistic change. Movements do not always begin with formal declarations; many gestate silently in habit, in marginal works, in minor exhibitions. In 1901, much was still gestural, tentative. But it was the shape of a world inventing itself.

The Beginnings of a New Art Ecology

One of the most decisive long‑term changes rooted in 1901 was institutional: the idea of art not as a preserve of aristocracy or academic elite, but as civic resource — something public, shared, mutable. Galleries like those newly founded or re‑imagined in 1901 began to treat exhibitions as events, not holdings; as encounters, not collections. The public was broadening. The idea that art could be for workers, immigrants, women, the curious — not just patrons — was gaining ground.

This shift in art’s social architecture would prove essential for modernism. The avant‑gardes, the radicals, the outsiders — they needed space not just to create, but to be seen. They needed exhibition networks, dealers willing to risk rather than canonise, audiences open rather than prescriptive. By loosening the gates just a little, 1901 helped build the ecosystem in which experimentation could flourish — even if that ecosystem would only fully bloom years later.

Emotional Depth and the Culture of Introspection

1901’s art also begins to show a sustained turn inward. Not all works of the year are suffused with melancholy or spiritual yearning, but enough suggest a shift: from depicting external narratives to evoking internal states. The shadows deepen. Figures stand alone. Spaces feel compressed. Colors cool, or swirl. The art becomes less about allegory or moralising, more about mood, absence, emotional weight.

That turn would take many shapes in decades to come — Expressionism, existential art, social realism, abstraction. But 1901 is one of the earliest moments when artists begin to ask not “what does the world look like?” but “what does the world feel like?” — a question that would reverberate through much of 20th‑century painting.

The Quiet Origins of Diversity and Plurality

If modernism is often defined by fragmentation — stylistic, geographic, cultural — then 1901 belongs to its early scattering. The seeds of plurality were planted in that year. Artists across Europe (and beyond) experimented — not with the same aims, but with shared disquiet. Institutions opened in unexpected places. Galleries began to offer space to the new and the unproven. The world of art widened.

In the years and decades to follow, that widening would only accelerate. Movements would collide. Styles would cross‑pollinate. Global cataclysms, migrations, and technological revolutions would rewire visual languages. But the first steps — humble, tentative — began in 1901. For that reason, when we look back from today, 1901 feels less like a year among many, and more like an under‑remarked threshold.

1901 as an Invitation — Not to Nostalgia, But to Continuity

Studying 1901 does not mean longing for a lost “authentic” moment. It does not mean searching for origins in order to canonize a purity. Rather, it means acknowledging that the familiar story of modern art — its ruptures, transformations, and revolutions — rests on less visible, softer shifts: psychological, institutional, social. Recognizing those shifts helps us preserve the complexity of art history, resist reductive narratives, and appreciate the many forces — subtle and structural — that shape what we call “modern.”

When we think of modernism today — its anxieties, its reinventions, its experiments — we trace its roots not only to its loudest outbursts but to quieter turns: a gallery opening in East London, a show of paintings by a dead Dutchman, a young Spaniard’s first exhibition in Paris, a shift in what it means to see. In those modest acts, 1901 reminds us that revolution often begins not with a roar, but with a quiet widening of possibility.

And that is why 1901 matters.